Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

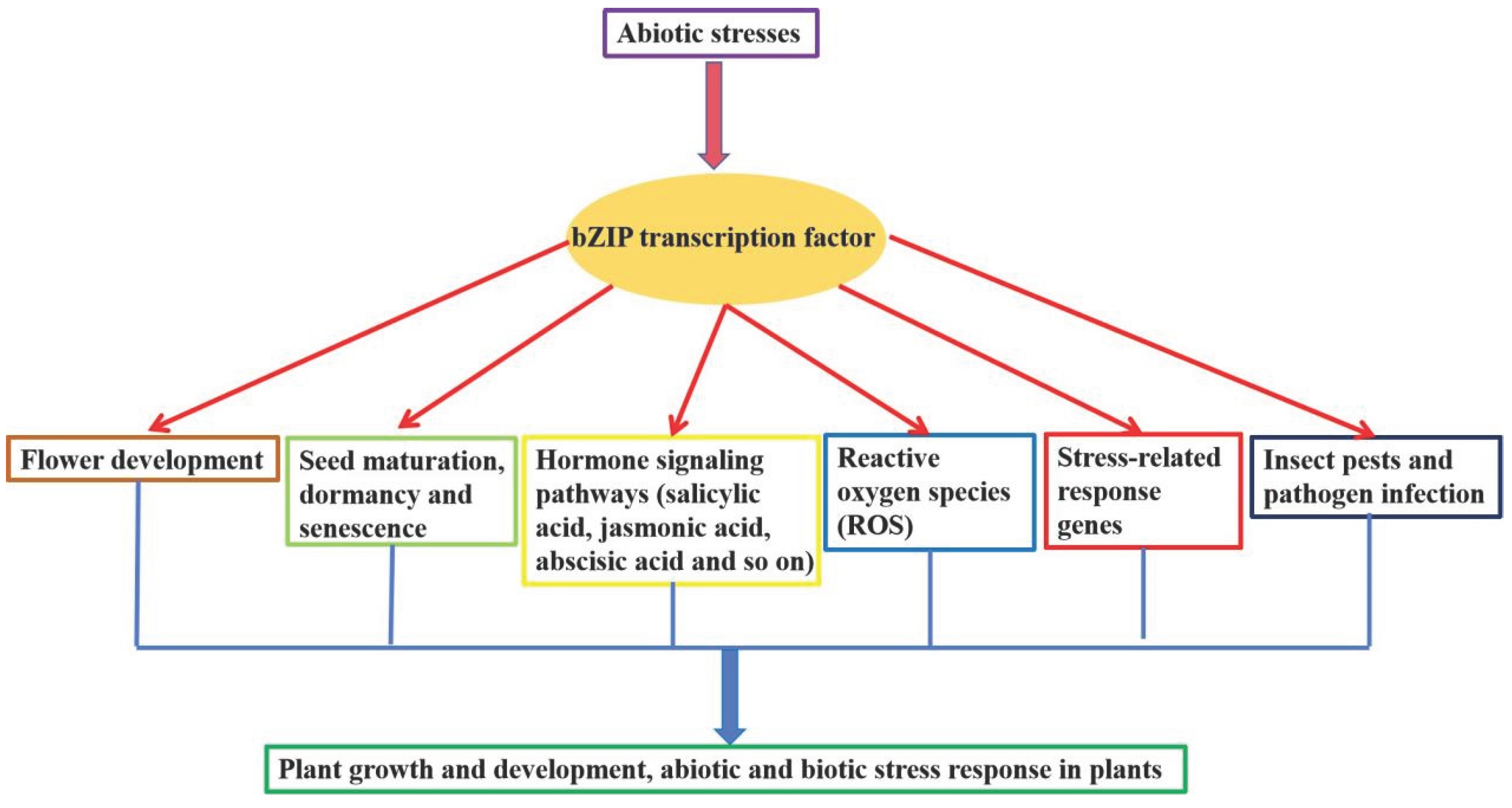

1. Introduction

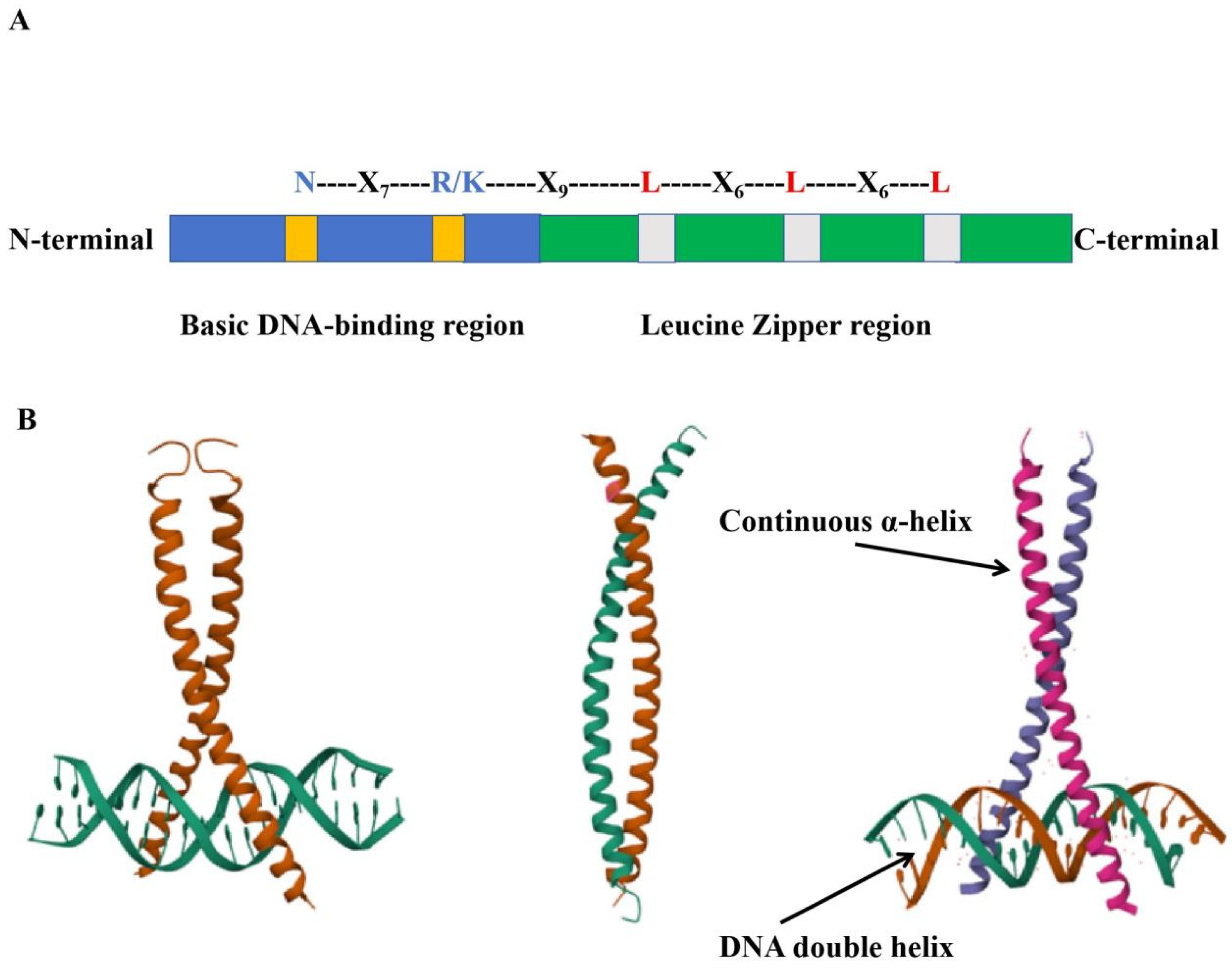

1.1. The Structure of the Plant bZIP Transcription Factors

1.2. The Classification of the Plant bZIP Transcription Factors

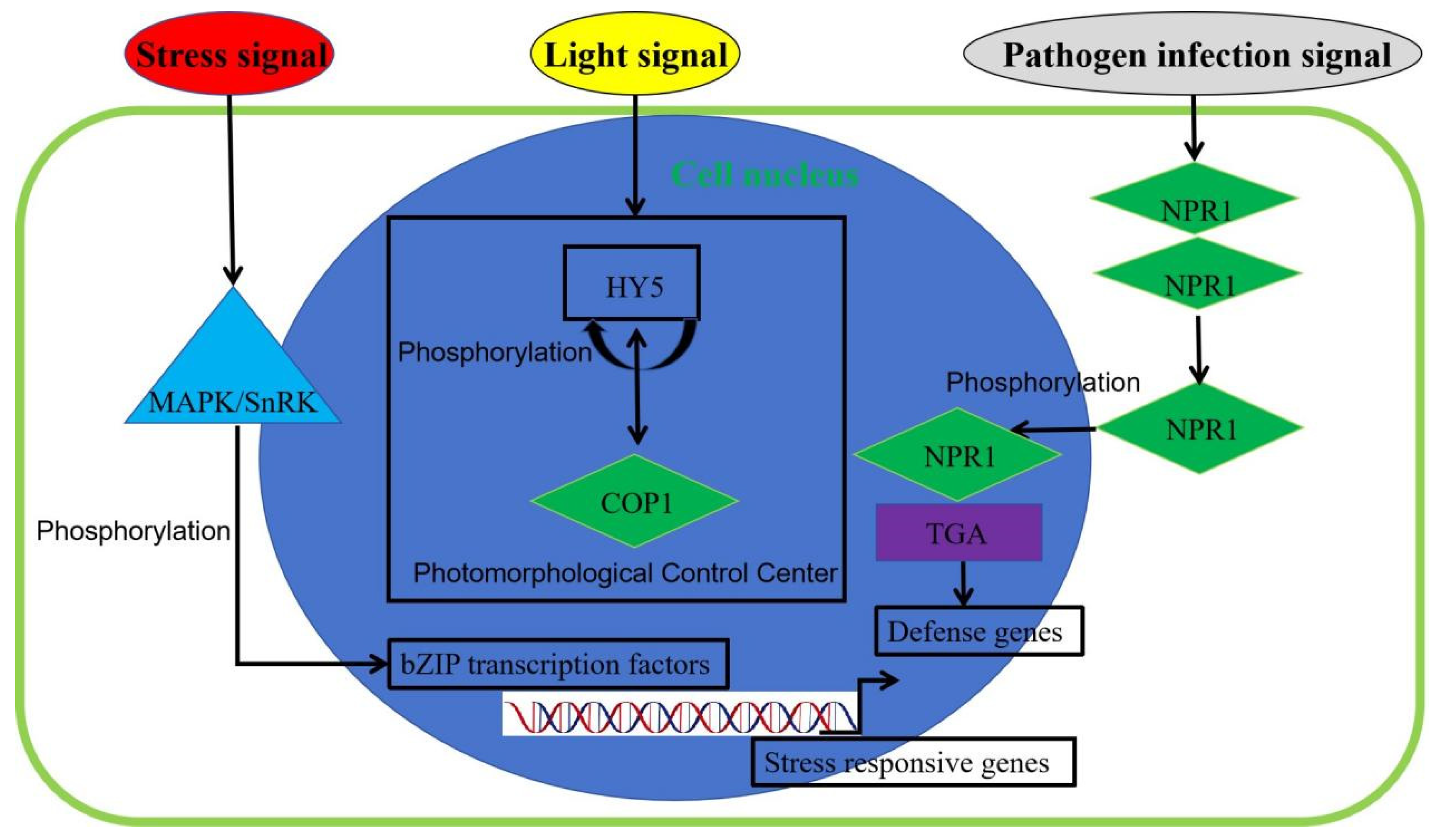

1.3. The Mechanism of Action of bZIP Transcription Factors

2. Role of bZIP Transcription Factors Involved Phytohormone in Plant Response to Abiotic Stresses

3. Role of bZIP Transcription Factors in Response to Abiotic Stresses

3.1. bZIP Transcription Factors in Response to Drought Stress

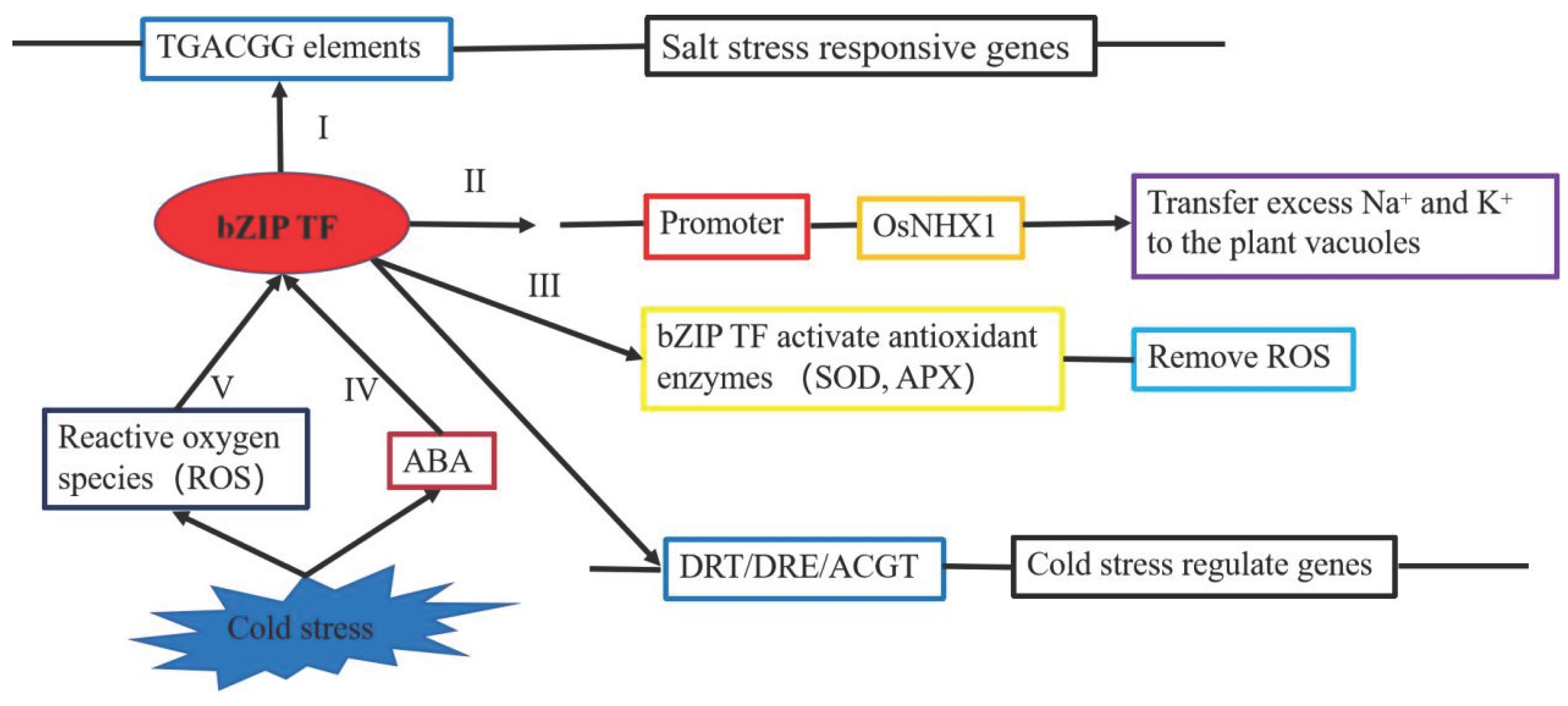

3.2. Molecular Mechanisms of bZIP Transcription Factors Associated with Salt Stress

3.3. bZIP Transcription Factors Involved in Plant Response to Temperature Stress

3.3.1. bZIP Transcription Factors and High-Temperature Stress

3.3.2. bZIP Transcription Factors and Low-Temperature Stress

3.4. Role of bZIP Transcription Factors in Response to Nutritional Element Stress

3.5. bZIP Transcription Factors Involved in Plant Response to Heavy Metals Stress

3.6. bZIP Transcription Factors Involved in Plant Response to High Light Stress

4. bZIP Transcription Factors Mediated Control of the Plant Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Pathways

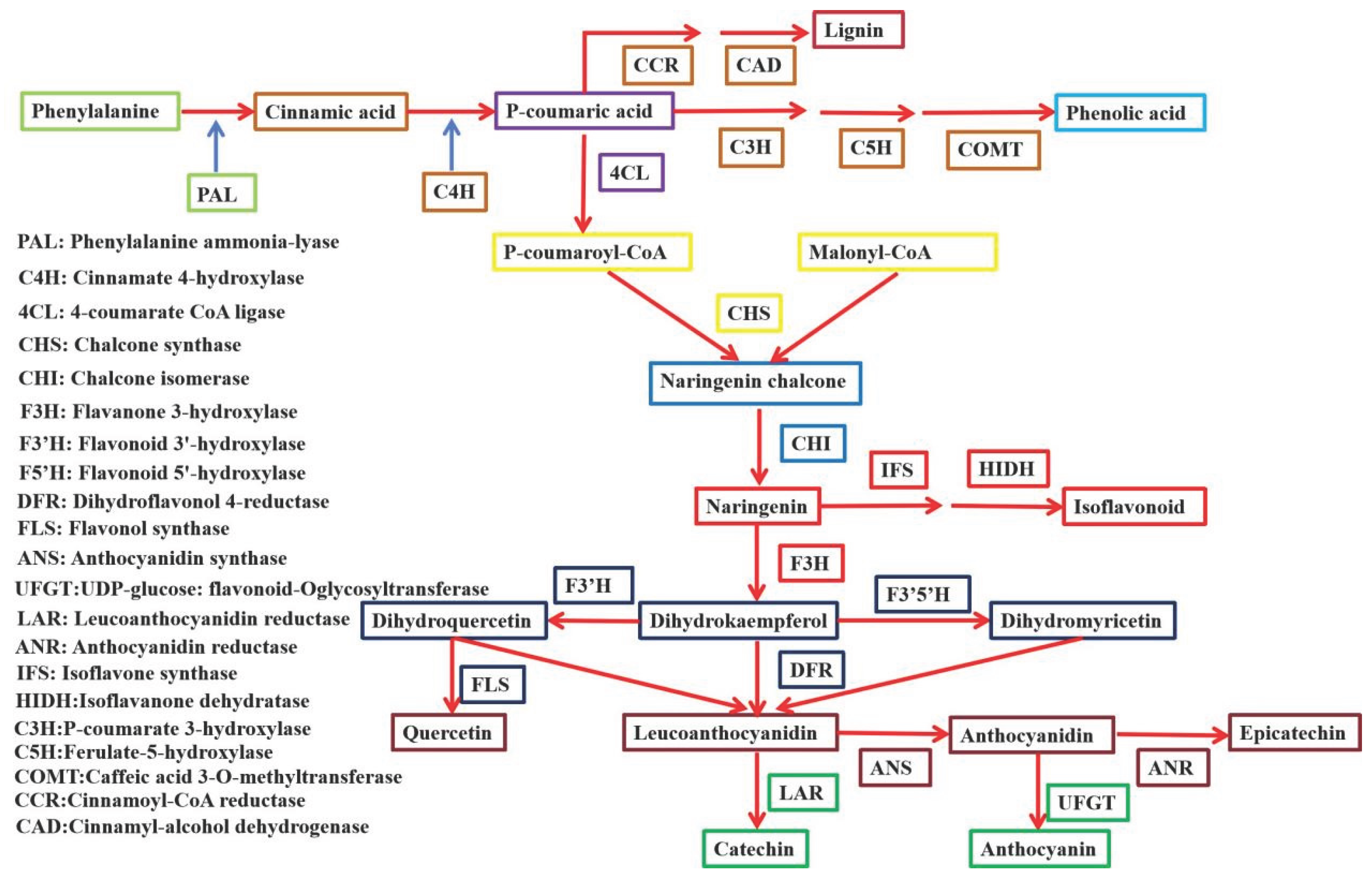

4.1. bZIP Transcription Factors Are Involved in Flavonoids Biosynthesis in Plants

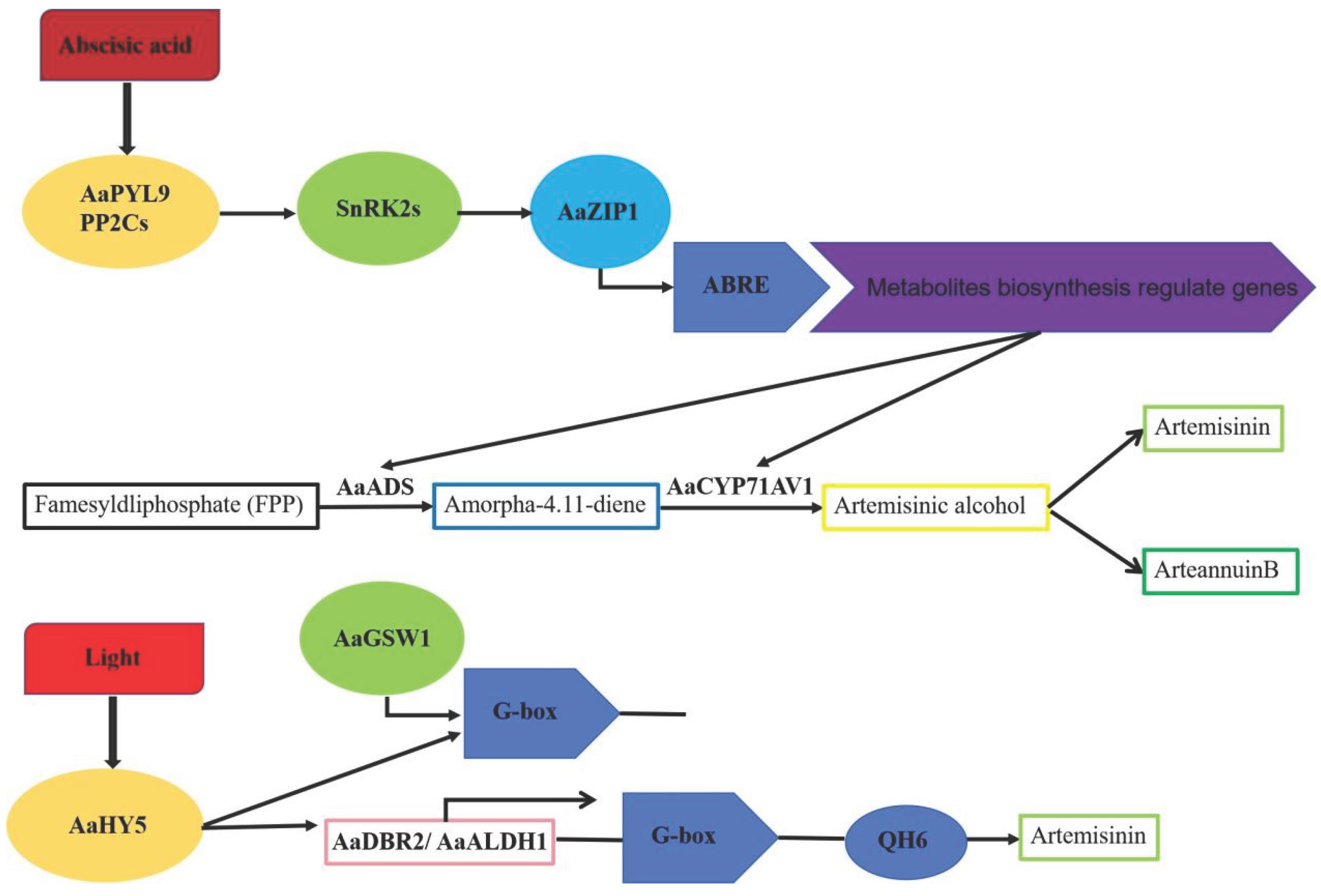

4.2. bZIP Transcription Factors Are Involved in Terpenoids Biosynthesis in Plants

4.3. bZIP Transcription Factors Are Involved in Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Plants

4.4. bZIP Transcription Factors Are Involved in Phenolic Acids in Plants

4.5. bZIP Transcription Factors Are Involved in Lignin in Plants

5. bZIP Transcription Factors Interact with ncRNAs to Regulate of Abiotic Stress in Plants

6. Conclusion and Prospects

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding Information

Data Availability

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, J.K. Abiotic stress responses in plants. Nat Rev Genet. 2022, 23, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L.; Jiang, W. Understanding AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Responses and Tolerance to Various Abiotic Stresses in Plants: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L. WRKY Transcription Factor Responses and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, T.; Gao, S.J. WRKY transcription factors in plant defense. Trends Genet. 2023, 39, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L. MicroRNA: A Dynamic Player from Signalling to Abiotic Tolerance in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 11364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wu, T.; Huang, K.; Jin, Y.M.; Li, Z.; Chen, M.; Yun, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Bai, H.; Du, L.; Ju, S.; Guo, L.; Bian, M.; Hu, L.; Du, X.; Jiang, W. A Novel AP2/ERF Transcription Factor, OsRPH1, Negatively Regulates Plant Height in Rice. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L.; Zhong, Y. Structure, evolution, and roles of MYB transcription factors proteins in secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways and abiotic stresses responses in plants: a comprehensive review. Front. Plant Sci 2025, 16, 1626844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubos, C.; Stracke, R.; Grotewold, E.; Weisshaar, B.; Martin, C.; Lepiniec, L. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Jin, Y.M.; Wu, T.; Hu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Du, X. OsDREB2B, an AP2/ERF transcription factor, negatively regulates plant height by conferring GA metabolism in rice. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1007811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ma, Z.; Hu, L.; Huang, K.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, W.; Wu, T.; Du, X. Involvement of rice transcription factor OsERF19 in response to ABA and salt stress responses. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021, 167, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Chi, H.; Wu, T.; Fan, W.; Su, H.; Li, R.; Jiang, W.; Du, X.; Ma, Z. Diversity of rhizosphere microbial communities in different rice varieties and their diverse adaptive responses to saline and alkaline stress. Front Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1537846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Ye, J.; Xu, F.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, W. Role of bZIP transcription factors in the regulation of plant secondary metabolism. Planta. 2023, 258, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Tang, X.; Zhang, N.; Li, S.; Si, H. Role of bZIP Transcription Factors in Plant Salt Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Dzinyela, R.; Yang, L.; Hwarari, D. bZIP Transcription Factors: Structure, Modification, Abiotic Stress Responses and Application in Plant Improvement. Plants (Basel). 2024, 13, 2058. [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, T.; Huda, M.N.; Zhang, K.; He, Y.; Lai, D.; Dhami, N.; Quinet, M.; Ali, M.A.; Kreft, I.; Woo, S.H.; Georgiev, M.I.; Fernie, A.R.; Zhou, M. Plant secondary metabolites against biotic stresses for sustainable crop protection. Biotechnol Adv. 2025, 79, 108520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizaz, M.; Lubna; Jan, R.; Asaf, S.; Bilal, S.; Kim, K.M.; Al-Harrasi, A. Regulatory Dynamics of Plant Hormones and Transcription Factors under Salt Stress. Biology (Basel). 2024, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Feng, B.; Li, P.; Li, C.; Zhu, C.Y.; Ren, S.N.; Wang, H.L. Regulatory networks of bZIPs in drought, salt and cold stress response and signaling. Plant Sci. 2025, 352, 112399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, C.R.B.; Serrão, C.P.; Barros, N.L.F.; Dos Reis, S.P.; Marques, D.N. Plant bZIP Proteins: Potential use in Agriculture - A Review. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2024, 25, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoel, S.H.; Dong, X. Salicylic acid in plant immunity and beyond. Plant Cell. 2024, 36, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yang, S. Regulatory Networks Underlying Plant Responses and Adaptation to Cold Stress. Annu Rev Genet. 2024, 58, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supriya, L.; Dake, D.; Woch, N.; Gupta, P.; Gopinath, K.; Padmaja, G.; Muthamilarasan, M. Sugar sensors in plants: Orchestrators of growth, stress tolerance, and hormonal crosstalk. J Plant Physiol. 2025, 307, 154471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Mao, Y.; Cui, J.; Lu, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, H.; Yu, W.; Li, C. The role of strigolactones in resistance to environmental stress in plants. Physiol Plant. 2024, 176, e14419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Looi, L.J.; Zhang, Z. The potential of melatonin and its crosstalk with other hormones in the fight against stress. Front Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1492036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wen, H.; Suprun, A.; Zhu, H. Ethylene Signaling in Regulating Plant Growth, Development, and Stress Responses. Plants (Basel). 2025, 14, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge-Laser, W.; Snoek, B.L.; Snel, B.; Weiste, C. The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor family-an update. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifici, E.; Polverari, L.; Sabatini, S. Plant hormone cross-talk: the pivot of root growth. J Exp Bot. 2015, 66, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutova, L.A.; Dodueva, I.E.; Lebedeva, M.A.; Tvorogova, V.E. Transcription Factors in Developmental Genetics and the Evolution of Higher Plants. Genetika. 2015, 51, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jin, L.; Peng, R. Crosstalk between Ca2+ and Other Regulators Assists Plants in Responding to Abiotic Stress. Plants (Basel). 2022, 11, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiak, A.; Kwaśniewski, M.; Szarejko, I. Gene expression regulation in roots under drought. J Exp Bot. 2016, 67, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, F.; Wu, M.; Hu, W.; Liu, R.; Yan, H.; Xiang, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analyses of the bZIP Transcription Factor Genes in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, L.J.; Zhu, Y.X. Transcription factor families in Arabidopsis: major progress and outstanding issues for future research. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006, 9, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangappa, S.N.; Botto, J.F. The Multifaceted Roles of HY5 in Plant Growth and Development. Mol Plant. 2016, 9, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golldack, D.; Li, C.; Mohan, H.; Probst, N. Tolerance to drought and salt stress in plants: Unraveling the signaling networks. Front Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, R.; Guo, C.; Hou, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, H. Evolutionary and Expression Analyses of the Apple Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factor Family. Front Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, N.; Hickman, R.; Van Dijken, A.J.H.; Kaufmann, M.; Snoek, B.L.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Van Wees, S.C.M. Architecture and dynamics of the abscisic acid gene regulatory network. Plant J. 2024, 119, 2538–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martignago, D.; Da, S.F.V.; Lombardi, A.; Gao, H.; Korwin, K.P.; Galbiati, M.; Tonelli, C.; Coupland, G.; Conti, L. The bZIP transcription factor AREB3 mediates FT signalling and floral transition at the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1010766. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.B.; Zhao, W.S.; Lin, R.M.; Wang, M.; Peng, Y.L. Identification of a novel rice bZIP-type transcription factor gene, OsbZIP1, involved in response to infection of Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 2005, 23, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, P.W.; Staber, P.B.; Hoefler, G.; Kenner, L. Translational regulation mechanisms of AP-1 proteins. Mutat Res. 2009, 682, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golldack, D.; Lüking, I.; Yang, O. Plant tolerance to drought and salinity: stress regulating transcription factors and their functional significance in the cellular transcriptional network. Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 30, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, B.; Ma, H.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, F.; Sun, X.; Wang, M.; Jiao, C.; Li, H. Distinct and essential roles of bZIP transcription factors in the stress response and pathogenesis in Alternaria alternata. Microbiol Res. 2022, 256, 126915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weltmeier, F.; Rahmani, F.; Ehlert, A.; Dietrich, K.; Schütze, K.; Wang, X.; Chaban, C.; Hanson, J.; Teige, M.; Harter, K.; Vicente-Carbajosa, J.; Smeekens, S.; Dröge-Laser, W. Expression patterns within the Arabidopsis C/S1 bZIP transcription factor network: availability of heterodimerization partners controls gene expression during stress response and development. Plant Mol Biol. 2009, 69, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakoby, M.; Weisshaar, B.; Dröge-Laser, W.; Vicente-Carbajosa, J.; Tiedemann, J.; Kroj, T.; Parcy, F. bZIP Research Group. bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.S.; Dadalto, S.P.; Gonçalves, A.B.; De Souza, G.B.; Barros, V.A.; Fietto, L.G. Plant bZIP transcription factors responsive to pathogens: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2013, 14, 7815–7828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.G.; Price, J.; Lin, P.C.; Hong, J.C.; Jang, J.C. The arabidopsis bZIP1 transcription factor is involved in sugar signaling, protein networking, and DNA binding. Mol Plant. 2010, 3, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, L.; Shang, G.G.; Jia, C.; Deng, S.; Noman, M.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Han, L.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Du, L.; Li, H.; Yang, J. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of bZIP gene family in Carthamus tinctorius L. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 15521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Foley, R.C.; Oñate-Sánchez, L. Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Yang, H.; Yan, Y.; Wei, Y.; Tie, W.; Ding, Z.; Zuo, J.; Peng, M.; Li, K. Genome-wide characterization and analysis of bZIP transcription factor gene family related to abiotic stress in cassava. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 22783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, W.; König, P.; Richmond, T.J. Crystal structure of a bZIP/DNA complex at 2.2 A: determinants of DNA specific recognition. J Mol Biol. 1995, 254, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, I.; Jung, H.J.; Park, J.I.; Yang, T.J.; Nou, I.S. Transcriptome analysis of newly classified bZIP transcription factors of Brassica rapa in cold stress response. Genomics. 2014, 104, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhawan, A.; Jain, M.; Tyagi, A.K.; Khurana, J.P. Genomic survey and gene expression analysis of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family in rice. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, S.; Tang, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, F.; Feng, B.; Fang, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhao, C. Genome-wide identification and evolutionary analyses of bZIP transcription factors in wheat and its relatives and expression profiles of anther development related TabZIP genes. BMC Genomics. 2015, 16, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Chen, X.; Yang, T.B.; Cheng, Q.; Cheng, Z.M. Genome-Wide Identification of bZIP Family Genes Involved in Drought and Heat Stresses in Strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Int J Genomics. 2017, 2017, 3981031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Fu, F.; Zhang, H.; Song, F. Genome-wide systematic characterization of the bZIP transcriptional factor family in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). BMC Genomics. 2015, 16, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, N.; Chen, F.; Cai, B.; Dal, S.S.; Tornielli, G.B.; Pezzotti, M.; Cheng, Z.M. Genome-wide analysis and expression profile of the bZIP transcription factor gene family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera). BMC Genomics. 2014, 15, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izawa, T.; Foster, R.; Chua, N.H. Plant bZIP protein DNA binding specificity. J Mol Biol. 1993, 230, 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narusaka, Y.; Nakashima, K.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Sakuma, Y.; Furihata, T.; Abe, H.; Narusaka, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Interaction between two cis-acting elements, ABRE and DRE, in ABA-dependent expression of Arabidopsis rd29A gene in response to dehydration and high-salinity stresses. Plant J. 2003, 34, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, F.; Zhou, H.; Xu, Y.; Huang, D.; Wu, B.; Xing, W.; Chen, D.; Xuv, B.; Song, S. Comprehensive analysis of bZIP transcription factors in passion fruit. iScience. 2023, 26, 106556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kang, J.Y.; Cho, D.I.; Park, J.H.; Kim, S.Y. ABF2, an ABRE-binding bZIP factor, is an essential component of glucose signaling and its overexpression affects multiple stress tolerance. Plant J. 2004, 40, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zou, H.F.; Wei, W.; Hao, Y.J.; Tian, A.G.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhang, J.S.; Chen, S.Y. Soybean GmbZIP44, GmbZIP62 and GmbZIP78 genes function as negative regulator of ABA signaling and confer salt and freezing tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Planta. 2008, 228, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, K.; Harter, K.; Chaban, C. Post-translational regulation of plant bZIP factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñiz, G.M.N.; Giammaria, V.; Grandellis, C.; Téllez, I.M.T.; Ulloa, R.M.; Capiati, D.A. Characterization of StABF1, a stress-responsive bZIP transcription factor from Solanum tuberosum L. that is phosphorylated by StCDPK2 in vitro. Planta. 2012, 235, 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Cao, H.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Borejsza, W.E.; Wang, H.; Dandekar, A.M.; Fei, Z.; Cheng, L. SnRK1 kinase-mediated phosphorylation of transcription factor bZIP39 regulates sorbitol metabolism in apple. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 2123–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.P.; Yao, J.F.; Xu, R.R.; You, C.X.; Wang, X.F.; Hao, Y.J. Apple bZIP transcription factor MdbZIP44 regulates abscisic acid-promoted anthocyanin accumulation. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 2678–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, W.; Tang, N.; Yang, J.; Peng, L.; Ma, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Xiong, L. Feedback Regulation of ABA Signaling and Biosynthesis by a bZIP Transcription Factor Targets Drought-Resistance-Related Genes. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2810–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, J.; Wang, L.; Si, L.; Zheng, S.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Tian, S. Wheat TabZIP8, 9, 13 participate in ABA biosynthesis in NaCl-stressed roots regulated by TaCDPK9-1. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020, 151, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.B.; Zhao, W.S.; Lin, R.M.; Wang, M.; Peng, Y.L. Identification of a novel rice bZIP-type transcription factor gene, OsbZIP1, involved in response to infection of Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 2025, 23, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendzen, K.W.; Weiste, C.; Wanke, D.; Kilian, J.; Harter, K.; Dröge-Laser, W. Bioinformatic cis-element analyses performed in Arabidopsis and rice disclose bZIP- and MYB-related binding sites as potential AuxRE-coupling elements in auxin-mediated transcription. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qian, J.Y.; Bian, Y.H.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.L. Transcriptome and Metabolite Conjoint Analysis Reveals the Seed Dormancy Release Process in Callery Pear. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Xia, N.; Wang, X.J.; Huang, L.L.; Kang, Z.S. Cloning and characterization of a bZIP transcription factor gene in wheat and its expression in response to stripe rust pathogen infection and abiotic stresses. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 2008, 73, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Hou, Z.; He, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yan, K.; Han, R.; Liang, Z. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of bZIP Gene Family Under Abiotic Stress in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Front Genet. 2021, 12, 754237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xie, K.; Zhang, C.; Xi, Y.; Sun, F. Genome-wide analysis of the abiotic stress-related bZIP family in switchgrass. Mol Biol Rep. 2020, 47, 4439–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Qiu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Tang, L.; Tong, X.; Zhang, J. Abscisic acid promotes jasmonic acid biosynthesis via a 'SAPK10-bZIP72-AOC' pathway to synergistically inhibit seed germination in rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1336–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, J. Salt and drought stress and ABA responses related to bZIP genes from V. radiata and V. angularis. Gene. 2018, 651, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Xia, C.; Gao, L.; Hao, C.; Zhao, G.; Jia, J.; Kong, X. A Novel Wheat C-bZIP Gene, TabZIP14-B, Participates in Salt and Freezing Tolerance in Transgenic Plants. Front Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Zhao, G.; Zheng, S.; Xie, S.; Lu, C.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Niu, J. Comprehensive Functional Analysis of the bZIP Family in Bletilla striata Reveals That BsbZIP13 Could Respond to Multiple Abiotic Stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 15202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Qiao, Y.; Pan, X.; Chen, X.; Su, W.; Li, A.; Li, X.; Liao, W. Genome-Wide identification and expression analysis of CsABF/AREB gene family in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) and in response to phytohormonal and abiotic stresses. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 15757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Yang, F.; Cai, S.; Liu, T.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Xi, X.; Yang, J.; Cao, Z.; Sun, L.; Dou, D.; Fang, X.; Yan, M.; Cai, H. Overexpression of the Transcription Factor GmbZIP60 Increases Salt and Drought Tolerance in Soybean (Glycine max). Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Cai, H.; Bai, M.; Zhang, M.; Chen, F.; Huang, Y.; Priyadarshani, S.V.G.N.; Chai, M.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Qin, Y. A Soybean bZIP Transcription Factor GmbZIP19 Confers Multiple Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses in Plant. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waadt, R.; Seller, C.A.; Hsu, P.K.; Takahashi, Y.; Munemasa, S.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Xiong, L.; Shi, H.; Yang, S.; Herrera-Estrella, L.R.; Xu, G.; Chao, D.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P.Y.; Qin, F.; Li, J.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J.K. Plant abiotic stress response and nutrient use efficiency. Sci China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah, K.K. ROS Homeostasis in Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Huang, K.; Chen, M.; Chen, C.; Yang, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Du, X. Identification and characterization of EDT1 conferring drought tolerance in rice. Journal of plant biology. 2019, 62, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Turkyilmaz, U.B.; García, C.P.; Khursheed, A.; Gul, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Osmoregulation and its actions during the drought stress in plants. Physiol Plant. 2021, 172, 1321–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, C.; Xu, X.; Su, C.; Li, J.; Song, H.; Zhang, X.; Pan, Y. SlbZIP38, a Tomato bZIP Family Gene Downregulated by Abscisic Acid, Is a Negative Regulator of Drought and Salt Stress Tolerance. Genes (Basel). 2017, 8, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Xu, P.; Wang, X.H.; Dai, S.J.; Liu, Z.N.; Xu, M.; Cao, X.; Cui, X.Y. GmTRAB1, a Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factor, Positively Regulates Drought Tolerance in Soybean (Glycine max. L). Plants (Basel). 2024, 13, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Gao, T.; Ma, Y. Characterization of bZIP Transcription Factors in Transcriptome of Chrysanthemum mongolicum and Roles of CmbZIP9 in Drought Stress Resistance. Plants (Basel). 2024, 13, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.; Guo, Y. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J Genet Genomics. 2024, 51, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, C.; Cheng, D.; Du, C.; Wang, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Han, J.; Xu, J. A novel maize F-bZIP member, ZmbZIP76, functions as a positive regulator in ABA-mediated abiotic stress tolerance by binding to ACGT-containing elements. Plant Sci. 2024, 341, 111952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Jiao, C.; Li, X.Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Yang, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Liang, Y.L.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Jia, P.; Zhang, X.; Qi, G.; Dong, Q. Identification and functional characterization of JrbZIP40 in walnut reveals its role in salt and drought stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, C.; Li, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, D.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Guo, Y. Identification and Analysis of bZIP Family Genes in Potato and Their Potential Roles in Stress Responses. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 637343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Mao, B.; Ou, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Chu, C.; Wang, X. OsbZIP71, a bZIP transcription factor, confers salinity and drought tolerance in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2014, 84, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, S. Surviving and thriving: How plants perceive and respond to temperature stress. Dev Cell. 2022, 57, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N. Temperature Stress and Responses in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Y.; Mu, X.R.; Gao, J.; Lin, H.X.; Lin, Y. The molecular basis of heat stress responses in plants. Mol Plant. 2023, 16, 1612–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrella, G.; Bäurle, I.; van, Z.M. Epigenetic regulation of thermomorphogenesis and heat stress tolerance. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1144–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Liu, Z.; Yang, S.; Yang, T.; Liang, J.; Wen, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, L.; Tang, Q.; Shi, W.; Hu, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, W.; Wang, R.; Yu, H.; Mou, S.; Hussain, A.; Cheng, W.; Cai, H.; He, L.; Guan, D.; Wu, Y.; He, S. Pepper CabZIP63 acts as a positive regulator during Ralstonia solanacearum or high temperature-high humidity challenge in a positive feedback loop with CaWRKY40. J Exp Bot. 2016, 67, 2439–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Dai, X.J.; Gu, Z.Y. OsbZIP33 is an ABA-dependent enhancer of drought tolerance in rice. Crop Science. 2015, 55, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Woldegiorgis, S.T.; Xu, S.; Feng, C.; Huang, G.; Shen, H.; Xu, Y.; Kabore, M.A.F.; Ai, Y.; Liu, W.; He, H. Integrated ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq Data Analysis to Reveal OsbZIP14 Function in Rice in Response to Heat Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, P. Unraveling the evolution of the ATB2 subgroup basic leucine zipper transcription factors in plants and decoding the positive effects of BdibZIP44 and BdibZIP53 on heat stress in Brachypodium distachyon. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2025, 222, 109708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadura, I.; Janeczko, A. Brassinosteroids and the Tolerance of Cereals to Low and High Temperature Stress: Photosynthesis and the Physicochemical Properties of Cell Membranes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 23, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Wu, A.; He, Y.; Li, F.; Wei, C. Genome-wide characterization of the basic leucine zipper transcription factors in Camellia sinensis. Tree Genetics & Genomes. 2018, 14, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Hao, X.; Cao, H.; Ding, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. ABA-dependent bZIP transcription factor, CsbZIP18, from Camellia sinensis negatively regulates freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xia, J.; Jiang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Zhang, D.; Yu, J.; Cang, J. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of bZIP Gene Family and Resistance of TaABI5 (TabZIP96) under Freezing Stress in Wheat (Triticum aestivum). Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X. bZIP transcription factor OsbZIP52/RISBZ5: a potential negative regulator of cold and drought stress response in rice. Planta. 2012, 235, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tang, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Li, G.; Ying, J.; Huang, J.; Tong, X.; Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. ABF1 Positively Regulates Rice Chilling Tolerance via Inducing Trehalose Biosynthesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, L.; Shakil, A.; Khan, I.; Alvi, T.; Singh, S.; Das, D. Brassinosteroids in Micronutrient Homeostasis: Mechanisms and Implications for Plant Nutrition and Stress Resilience. Plants (Basel). 2025, 14, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Garcia, C.P.; Mühling, K.H. Editorial: Mineral nutrition and plant stress tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1461651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, A.G.L. The F-bZIP-regulated Zn deficiency response in land plants. Planta. 2022, 256, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiébaut, N.; Hanikenne, M. Zinc deficiency responses: bridging the gap between Arabidopsis and dicotyledonous crops. J Exp Bot. 2022, 73, 1699–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assunção, A.G.; Herrero, E.; Lin, Y.F.; Huettel, B.; Talukdar, S.; Smaczniak, C.; Immink, R.G.; van, E.M.; Fiers, M.; Schat, H.; Aarts, M.G. Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factors bZIP19 and bZIP23 regulate the adaptation to zinc deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107, 10296–10301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilay, G.H.; Castro, P.H.; Campilho, A.; Assunção, A.G.L. The Arabidopsis bZIP19 and bZIP23 Activity Requires Zinc Deficiency - Insight on Regulation From Complementation Lines. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G. Iron uptake, signaling, and sensing in plants. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankotia, S.; Singh, D.; Monika, K.; Kalra, M.; Meena, H.; Meena, V.; Yadav, R.K.; Pandey, A.K.; Satbhai, S.B. ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 regulates BRUTUS and affects iron acquisition and homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2023, 114, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morkunas, I.; Woźniak, A.; Mai, V.C.; Rucińska, S.R.; Jeandet, P. The Role of Heavy Metals in Plant Response to Biotic Stress. Molecules. 2018, 23, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncharuk, E.A.; Zagoskina, N.V. Heavy Metals, Their Phytotoxicity, and the Role of Phenolic Antioxidants in Plant Stress Responses with Focus on Cadmium: Review. Molecules. 2023, 28, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Zhou, J.; Jie, Y.; Xing, H.; Zhong, Y.; Yu, W.; She, W.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y. A Ramie bZIP Transcription Factor BnbZIP2 Is Involved in Drought, Salt, and Heavy Metal Stress Response. DNA Cell Biol. 2016, 35, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Qiu, W.; Jin, K.; Yu, M.; Han, X.; He, X.; Wu, L.; Wu, C.; Zhuo, R. Identification and Analysis of bZIP Family Genes in Sedum plumbizincicola and Their Potential Roles in Response to Cadmium Stress. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 859386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Fan, R.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wai, M.H.; Yang, Q.; Su, H.; Liu, K.; Ma, S.; Chen, Z.; Wang, F.; Qin, Y.; Cai, H. GmbZIP152, a Soybean bZIP Transcription Factor, Confers Multiple Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses in Plant. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 10935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Liu, K.; Zhang, N.; Zou, C.; Yuan, G.; Gao, S.; Zhang, M.; Pan, G.; Ma, L.; Shen, Y. Association mapping uncovers maize ZmbZIP107 regulating root system architecture and lead absorption under lead stress. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1015151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Fang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yang, S.; Su, J.; Ni, J.; Teng, Y.; Bai, S. Phosphorylated transcription factor PuHB40 mediates ROS-dependent anthocyanin biosynthesis in pear exposed to high light. Plant Cell. 2024, 36, 3562–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Ke, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Hou, X. Plants response to light stress. J Genet Genomics. 2022, 49, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Fang, H.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Hou, Z. Identification and Characterization of bZIP Gene Family Combined Transcriptome Analysis Revealed Their Functional Roles on Abiotic Stress and Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Mulberry (Morus alba). Horticulturae. 2025, 11, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, R.; Favory, J.J.; Gruber, H.; Bartelniewoehner, L.; Bartels, S.; Binkert, M.; Funk, M.; Weisshaar, B.; Ulm, R. The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor HY5 regulates expression of the PFG1/MYB12 gene in response to light and ultraviolet-B radiation. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Cao, K.; Wang, X. AtbZIP16 and AtbZIP68, two new members of GBFs, can interact with other G group bZIPs in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMB Rep. 2008, 41, 132–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wen, K.S.; Ruan, X.; Zhao, Y.X.; Wei, F.; Wang, Q. Response of Plant Secondary Metabolites to Environmental Factors. Molecules. 2018, 23, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonta, R.K. Dietary Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids as Potential Anti-Cancer Agents: Current State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2020, 20, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Cai, W.; Zhang, H.H.; Zhong, Y.S.; Fang, J.; Zhang, W.Y.; Mo, L.; Wang, L.C.; Yu, C.H. Selaginella uncinata flavonoids ameliorated ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation in a rat model of asthma. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 195, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.H.; Cheng, B.H.; Shi, G.H.; Chen, G.D.; Gu, B.B.; Zhou, Y.J.; Hong, L.L.; Yang, F.; Liu, Z.Q.; Qiu, S.Q.; Liu, Z.G.; Yang, P.C.; Lin, H.W. Dysivillosins A-D, Unusual Anti-allergic Meroterpenoids from the Marine Sponge Dysidea villosa. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, P.; Sastraruji, T.; Taweechotipatr, M.; Keller, P.A.; Pyne, S.G. Anti-inflammatory, Anti-bacterial and Anti-acetylcholinesterase Activities of two Isoquinoline Alkaloids-Scoulerine and Cheilanthifoline. Nat Prod Commun. 2016, 11, 1801–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, S.; Jadaun, J.; Chandra, M.; Sangwan, N. Medicinal plant transcriptomes: The new gateways for accelerated understanding of plant secondary metabolism. Plant Genet Resour. 2016, 14, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Zhao, Q. Unraveling the specialized metabolic pathways in medicinal plant genomes: a review. Front Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1459533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Rashmi, R.; Toppo, V.; Chole, P.B.; Banadka, A.; Sudheer, W.N.; Nagella, P.; Shehata, W.F.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q.; Alessa, F.M.; Almaghasla, M.I.; Rezk, A.A. Plant Secondary Metabolites: The Weapons for Biotic Stress Management. Metabolites. 2023, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erb, M.; Kliebenstein, D.J. Plant Secondary Metabolites as Defenses, Regulators, and Primary Metabolites: The Blurred Functional Trichotomy. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borek, C. Antioxidant health effects of aged garlic extract. J Nutr. 2001, 131, 1010S–5S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Dong, L.; Zhang, W.; Liao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Ye, J.; Xu, F. Ginkgo biloba GbbZIP08 transcription factor is involved in the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis. J Plant Physiol. 2023, 287, 154054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Lu, C.; Zhou, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, A.; Shen, Y.; Pan, L.; Lv, A.; Shao, Q. Transcription factor DcbZIPs regulate secondary metabolism in Dendrobium catenatum during cold stress. Physiol Plant. 2024, 176, e14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Yu, L.; Fu, M.; Liao, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Ye, J. Genome-wide characterization of bZIP gene family identifies potential members involved in flavonoids biosynthesis in Ginkgo biloba L. Sci Rep. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 23420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Huang, J.; Guo, H.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Shen, S.; Zhan, C.; Qu, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Luo, J. OsRLCK160 contributes to flavonoid accumulation and UV-B tolerance by regulating OsbZIP48 in rice. Sci China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 1380–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholl, D. Biosynthesis and biological functions of terpenoids in plants. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2015, 148, 63–106. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Li, P.; Lu, X. Research advances in cytochrome P450-catalysed pharmaceutical terpenoid biosynthesis in plants. J Exp Bot. 2019, 70, 4619–4630. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, R.; Ranjan, A.; Kumar, R.S.; Pathak, P.K.; Trivedi, P.K. Light-regulated expression of terpene synthase gene, AtTPS03, is controlled by the bZIP transcription factor, HY5, in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020, 529, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zeng, T.; Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Luo, J.; Zheng, R.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, C. TcbZIP60 positively regulates pyrethrins biosynthesis in Tanacetum cinerariifolium. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1133912. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Chen, J.; Tang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Xu, D.; Hou, K.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of bZIP Family Genes in Stevia rebaudiana. Genes (Basel). 2023, 14, 1918. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Fu, X.; Lv, Z.; Lu, X.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, M.; Wang, G.; Sun, X.; Liao, Z.; Tang, K. A basic leucine zipper transcription factor, AabZIP1, connects abscisic acid signaling with artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Mol Plant. 2015, 8, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Roychoudhury, A. Abscisic-acid-dependent basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors in plant abiotic stress. Protoplasma. 2017, 254, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Facchini, P.J. Regulation of alkaloid biosynthesis in plants. Alkaloids Chem Biol. 2006, 63, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bhambhani, S.; Kondhare, K.R.; Giri, A.P. Diversity in Chemical Structures and Biological Properties of Plant Alkaloids. Molecules. 2021, 26, 3374. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, Z.; Ren, W.; Yan, S.; Xing, N.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Ma, W. Identification of the bZIP gene family and regulation of metabolites under salt stress in isatis indigotica. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1011616. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, X.; Singh, S.K.; Patra, B.; Schluttenhofer, C.; Guo, W.; Pattanaik, S.; Yuan, L. Cross-family transcription factor interaction between MYC2 and GBFs modulates terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis. J Exp Bot. 2018, 69, 4267–4281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stuper-Szablewska, K.; Perkowski, J. Phenolic acids in cereal grain: Occurrence, biosynthesis, metabolism and role in living organisms. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019, 59, 664–675. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova, N.; Vinogradova, E.; Chaplygin, V.; Mandzhieva, S.; Kumar, P.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Seth, C.S.; Burachevskaya, M.; Lysenko, D.; Singh, R.K. Phenolic Compounds of the Medicinal Plants in an Anthropogenically Transformed Environment. Molecules. 2023, 28, 6322. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Phenolic composition, antioxidant potential and health benefits of citrus peel. Food Res Int. 2020, 132, 109114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Hua, Q.; Kai, G.Y. Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis in response to abscisic acid in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2021, 147, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, J.; Battistoni, B.; Fiol, A.; Dare, A.P.; Ballesta, P.; Ahumada, S.; Meisel, L.A.; Allan, A.; Espley, R.; Pacheco, I. Systematic characterization of the bZIP transcription factor family of Japanese plum (Prunus salicina Lindl.) and their potential role in phenolic compound biosynthesis. Scientia Horticulturae. 2025, 341, 113962. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, J.C.; Bonine, C.A.; de Oliveira, F.V.J.; Dornelas, M.C.; Mazzafera, P. Abiotic and biotic stresses and changes in the lignin content and composition in plants. J Integr Plant Biol. 2010, 52, 360–376. [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan, W.; Ralph, J.; Baucher, M. Lignin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003, 54, 519–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, L.; Zheng, L. Lignins: Biosynthesis and Biological Functions in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, M.; Wang, X.; Yin, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Song, J.; Wang, X. Grapevine VlbZIP30 improves drought resistance by directly activating VvNAC17 and promoting lignin biosynthesis through the regulation of three peroxidase genes. Hortic Res. 2020, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, H.; Rizwan, H.M.; Wang, N.; Jiang, J.; She, W.; Zheng, G.; Pan, H.; Guo, Z.; Pan, D.; Pan, T. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Candidate Lignin-Related Genes and Transcription Factors during Fruit Development in Pomelo (Citrus maxima). Genes (Basel). 2022, 13, 845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, K.; Bayraktar, R.; Ferracin, M.; Calin, G.A. Non-coding RNAs in disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Nat Rev Genet. 2024, 25, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattick, J.S.; Amaral, P.P.; Carninci, P.; Carpenter, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Chen, L.L.; Chen, R.; Dean, C.; Dinger, M.E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Gingeras, T.R.; Guttman, M.; Hirose, T.; Huarte, M.; Johnson, R.; Kanduri, C.; Kapranov, P.; Lawrence, J.B.; Lee, J.T.; Mendell, J.T.; Mercer, T.R.; Moore, K.J.; Nakagawa, S.; Rinn, J.L.; Spector, D.L.; Ulitsky, I.; Wan, Y.; Wilusz, J.E.; Wu, M. Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzbicki, A.T.; Blevins, T.; Swiezewski, S. Long Noncoding RNAs in Plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilusz, J.E.; Sunwoo, H.; Spector, D.L. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, P.M.; Krishnatreya, D.B.; Bordoloi, K.S.; Gill, S.S.; Agarwala, N. Genome wide identification and characterization of abiotic stress responsive lncRNAs in Capsicum annuum. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021, 162, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, M.C.; Eldem, V.; Hajyzadeh, M.; Unver, T. Genome-wide analysis of the bZIP transcription factors in cucumber. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e96014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neysanian, M.; Iranbakhsh, A.; Ahmadvand, R.; Ardebili, Z.O.; Ebadi, M. Selenium nanoparticles conferred drought tolerance in tomato plants by altering the transcription pattern of microRNA-172 (miR-172), bZIP, and CRTISO genes, upregulating the antioxidant system, and stimulating secondary metabolism. Protoplasma. 2024, 261, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Fan, G.; Su, L.; Wang, W.; Liang, Z.; Li, S.; Xin, H. Identification of cold-inducible microRNAs in grapevine. Front Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, L.G.; Riaño-Pachón, D.M.; Schrago, C.G.; dos Santos, R.V.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Vincentz, M. The role of bZIP transcription factors in green plant evolution: adaptive features emerging from four founder genes. PLoS One. 2008, 3, e2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Lin, Y.; Pan, S.; Zhong, X.; Xie, D. Genome-wide analysis of bZIP-encoding genes in maize. DNA Res. 2012, 19, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Shi, H.; Guo, M.; Chai, M.; He, Q.; Yan, M.; Cao, D.; Zhao, L.; Cai, H.; Qin, Y. Evolutionary and expression analyses of soybean basic Leucine zipper transcription factor family. BMC Genomics. 2018, 19, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Xu, W.; Liu, A. Genomic surveys and expression analysis of bZIP gene family in castor bean (Ricinus communis L.). Planta. 2014, 239, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, G.; Tang, Y.; Lu, X.; Qiao, X.; Wang, C. Genome-Wide Survey and Expression Analysis of the Basic Leucine Zipper (bZIP) Gene Family in Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Horticulturae. 2022, 8, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, D.; Verma, S.K.; Halterman, D.; Kumar, A. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of basic leucine zipper transcription factors following abiotic stresses in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0247864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, W.; Qi, X.; Liu, Z.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y. Genome-wide identification, expression profiling, and SSR marker development of the bZIP transcription factor family in Medicago truncatula. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 2015, 61, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xie, K.; Zhang, C.; Xi, Y.; Sun, F. Genome-wide analysis of the abiotic stress-related bZIP family in switchgrass. Mol Biol Rep. 2020, 47, 4439–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Zhong, Y.; Cheng, Z.M.; Xiong, J.S. Divergence of the bZIP Gene Family in Strawberry, Peach, and Apple Suggests Multiple Modes of Gene Evolution after Duplication. Int J Genomics. 2015, 2015, 536943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chai, M.; Zhang, M.; He, Q.; Su, Z.; Priyadarshani, S.V.G.N.; Liu, L.; Dong, G.; Qin, Y. Genome-Wide Analysis, Characterization, and Expression Profile of the Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factor Family in Pineapple. Int J Genomics. 2020, 2020, 3165958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Chen, S.; Yao, W.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, T. Genome-wide analysis and expression profile of the bZIP gene family in poplar. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.H. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the bZIP gene family in silver birch (Betula pendula Roth.). J. For. Res. 2022, 33, 1615–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, Q.; Guo, F.; Chai, R.; Wang, M.; Deng, X.; Dong, T.; Meng, X.; Zhu, M. Genome- and transcriptome-widesystematic characterization of bZIP transcription factor family identifies promising members involved in abiotic stress responsein sweetpotato. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 303, 111185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B.; Vanitha, J.; Ramachandran, S.; Jiang, S.Y. Genome-wide expansion and expression divergence of the basic leucine zipper transcription factors in higher plants with an emphasis on sorghum. J Integr Plant Biol. 2011, 53, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Quan, S.; Niu, J.; Guo, C.; Kang, C.; Liu, J.; Yuan, X. Genome-Wide Identification, Classification, Expression and Duplication Analysis of bZIP Family Genes in Juglans regia L. Int J Mol Sci. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, D.; Jia, L.; Huang, X.; Ma, G.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, A.; Guan, M.; Lu, K.; Xu, X.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Qu, C. Genome-Wide Identification and Structural Analysis of bZIP Transcription Factor Genes in Brassica napus. Genes (Basel). 2017, 8, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Meng, X.; Fan, X.; Chen, S.; Sang, K.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, X. Regulation of PILS genes by bZIP transcription factor TGA7 in tomato plant growth. Plant Sci. 2025, 352, 112359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardeli, S.M.; Arge, L.W.P.; Artico, S.; de Moura, S.M.; Tschoeke, D.A.; de Freitas, Guedes, F.A.; Grossi-de-Sa, M.F.; Martinelli, A.P.; Alves-Ferreira, M. Global gene expression profile and functional analysis reveal the conservation of reproduction-associated gene networks in Gossypium hirsutum. Plant Reprod. 2024, 37, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chu, Z. Genome-wide evolutionary characterization and analysis of bZIP transcription factors and their expression profiles in response to multiple abiotic stresses in Brachypodium distachyon. BMC Genomics. 2015, 16, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourabed, E.; Ghane, G.F.; Soleymani, M.P.; Razavi, S.M.; Shobbar, Z.S. Basic leucine zipper family in barley: genome-wide characterization of members and expression analysis. Mol Biotechnol. 2015, 57, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, K.; Bahramnejad, B.; Fatemi, S. Genome⁃wide identification and characterization of the bZIP gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum). Plant Gene. 2020, 24, 100257–100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Srivastava, R.; Che, P.; Howell, S.H. Salt stress responses in Arabidopsis utilize a signal transduction pathway related to endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling. Plant J. 2007, 51, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veerabagu, M.; Kirchler, T.; Elgass, K.; Stadelhofer, B.; Stahl, M.; Harter, K.; Mira-Rodado, V.; Chaban, C. The interaction of the Arabidopsis response regulator ARR18 with bZIP63 mediates the regulation of PROLINE DEHYDROGENASE expression. Mol Plant. 2014, 7, 1560–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van, L.J.; Blomme, J.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Cannoot, B.; De, W.N.; Eeckhout, D.; Persiau, G.; Van, D.S.E.; Vercruysse, L.; Vanden Bossche, R.; Heyndrickx, K.S.; Vanneste, S.; Goossens, A.; Gevaert, K.; Vandepoele, K.; Gonzalez, N.; Inzé, D.; De, J.G. Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis transcription factor bZIP29 reveals its role in leaf and root development. J Exp Bot. 2016, 67, 5825–5840. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Page, M. Transcription factor AtbZIP60 regulates expression of Ca2+ -dependent protein kinase genes in transgenic cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2013, 40, 2723–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakra, N.; Nutan, K.K.; Das, P.; Anwar, K.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A. A nuclear-localized histone-gene binding protein from rice (OsHBP1b) functions in salinity and drought stress tolerance by maintaining chlorophyll content and improving the antioxidant machinery. J Plant Physiol. 2015, 176, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Lakra, N.; Nutan, K.K.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A. A unique bZIP transcription factor imparting multiple stress tolerance in Rice. Rice (N Y). 2019, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K.; Choudhury, A.R.; Gupta, B.; Gupta, S.; Sengupta, D.N. An ABRE-binding factor, OSBZ8, is highly expressed in salt tolerant cultivars than in salt sensitive cultivars of indica rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2006, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Qiao, J.; Quan, R.; Wang, J.; Huang, R.; Qin, H. SALT AND ABA RESPONSE ERF1 improves seed germination and salt tolerance by repressing ABA signaling in rice. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 1110–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, H.M.; Lee, Y.; Cho, J.I.; Ahn, C.H.; Lee, S.K.; Jeon, J.S.; Kang, H.; Lee, C.H.; An, G.; Park, P.B. The bZIP transcription factor OsABF1 is an ABA responsive element binding factor that enhances abiotic stress signaling in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2010, 72, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.; Lee, Y.H.; Song, S.I. Overexpression of the rice basic leucine zipper transcription factor OsbZIP12 confers drought tolerance to rice and makes seedlings hypersensitive to ABA. Plant Biotechnology Reports. 2014, 8, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, W.; Zhou, J.; He, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Deng, X.W. Basic leucine zipper transcription factor OsbZIP16 positively regulates drought resistance in rice. Plant Sci 2012, 193-194, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, B.; Ren, J.; Zhou, Y.; Han, Y.; Niu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yang, C.; Ma, X.; Liu, X.; LuoV, Y.; Jin, C.; Luo, J. OsbZIP18, a Positive Regulator of Serotonin Biosynthesis, Negatively Controls the UV-B Tolerance in Rice. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; Xu, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.F.; Sun, Z.G.; Chi, M.; Xing, Y.G.; Yang, B.; Li, J.; Liu, J.B.; Chen, T.M.; Fang, Z.W.; Lu, B.G.; Xu, D.Y.; Babatunde, K.B. A novel mechanisms of the signaling cascade associated with the SAPK10-bZIP20 NHX1 synergistic interaction to enhance tolerance of plant to abiotic stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Science. 2022, 323, 111393. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, W.; Yang, J.; Fu, J.; Xiong, L. Synergistic regulation of drought-responsive genes by transcription factor OsbZIP23 and histone modification in rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Sato, K.; Berberich, T.; Miyazaki, A.; Ozaki, R.; Imai, R.; Kusano, T. LIP19, a basic region leucine zipper protein, is a Fos-like molecular switch in the cold signaling of rice plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005, 46, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilay, G.H.; Castro, P.H.; Guedes, J.G.; Almeida, D.M.; Campilho, A.; Azevedo, H.; Aarts, M.G.M.; Saibo, N.J.M.; Assunção, A.G.L. Rice F-bZIP transcription factors regulate the zinc deficiency response. J Exp Bot. 2020, 71, 3664–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Jeong, J.S.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Choi, Y.D.; Kim, J.K. OsbZIP23 and OsbZIP45, members of the rice basic leucine zipper transcription factor family, are involved in drought tolerance. Plant Biotechnology Reports. 2015, 9, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Ma, S.; Zong, W.; Yang, N.; Lv, Y.; Yan, C.; Guo, Z.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Xiang, Y.; Song, H.; Xiao, J.; Li, X.; Xiong, L. MODD Mediates Deactivation and Degradation of OsbZIP46 to Negatively Regulate ABA Signaling and Drought Resistance in Rice. Plant Cell. 2016, 28, 2161–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Niu, X.L.; Yang, S.H.; Li, Y.X.; Liu, L.L.; Tang, W.; Liu, Y.S. Research on heat and drought tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) by overexpressing transcription factor OsbZIP60. Scientia Agricultura Sinica. 2011, 44, 4142–4149. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Xu, K.; Chen, S.; Li, T.; Xia, H.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Luo, L. A stress-responsive bZIP transcription factor OsbZIP62 improves drought and oxidative tolerance in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, D.K.; Yu, I.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Choi, Y.D.; Kim, J.K. Overexpression of the OsbZIP66 transcription factor enhances drought tolerance of rice plants. Plant Biotechnology Reports, 2017, 11, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Chi, M.; Xing, Y.; Xu, B.; Yang, B.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, T.; Fang, Z.; Lu, B.; Xu, D.; Babatunde, K.B. OsbZIP72 is involved in transcriptional gene-regulation pathway of abscisic acid signal transduction by activating rice high-affinity potassium transporter OsHKT1;1. Rice Science, 2021, 28, 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Schläppi, M.R.; Mao, B.; Wang, W.; Wang, A.; Chu, C. The bZIP73 transcription factor controls rice cold tolerance at the reproductive stage. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019, 17, 1834–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Li, M.; Yang, S.; Gao, C.; Su, Y.; Zeng, X.; Jiao, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhang, M.; Xia, K. miR2105 and the kinase OsSAPK10 co-regulate OsbZIP86 to mediate drought-induced ABA biosynthesis in rice. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 889–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lu, G.; Hao, Y.; Guo, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, H. ABP9, a maize bZIP transcription factor, enhances tolerance to salt and drought in transgenic cotton. Planta. 2017, 246, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, Q.; Jin, X.; Peng, X.; Liu, J.; Deng, L.; YanV, H.; Sheng, L.; JiangV, H.; Cheng, B. A novel maize homeodomain-leucine zipper (HD-Zip) I gene, Zmhdz10, positively regulates drought and salt tolerance in both rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 1142–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, K.; Wan, L.; Yan, L.; Jiang, H.; Liu, S.; Lei, Y.; Liao, B. Genome-wide analysis of the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor gene family in six legume genomes. BMC Genomics. 2015, 16, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Yu, Y.; Dong, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Du, F.; Xia, C.; Ni, Z.; Kong, X.; Zhang, L. The bZIP transcription factor TabZIP15 improves salt stress tolerance in wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021, 19, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.N.; Fan, S.Y.; Zhang, T.T.; et al. SlHY5 is a necessary regulator of the cold acclimation response in tomato. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 91, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.H.; Li, C.W.; Su, R.C.; Cheng, C.P.; Sanjaya; Tsai, Y.C.; Chan, M.T. A tomato bZIP transcription factor, SlAREB, is involved in water deficit and salt stress response. Planta. 2010, 231, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminaka, H.; Näke, C.; Epple, P.; Dittgen, J.; Schütze, K.; Chaban, C.; Holt, B.F.; Merkle, T.; Schäfer, E.; Harter, K.; Dangl, J.L. bZIP10-LSD1 antagonism modulates basal defense and cell death in Arabidopsis following infection. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 4400–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, A.; Okada, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Koga, J.; Shibuya, N.; Nojiri, H.; Yamane, H. OsTGAP1, a bZIP transcription factor, coordinately regulates the inductive production of diterpenoid phytoalexins in rice. J Biol Chem. 2009, 284, 26510–26518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, K.; Nishizawa, Y.; Minami, E.; Nojiri, H.; Yamane, H.V.; Okada, K. Overexpression of the bZIP transcription factor OsbZIP79 suppresses the production of diterpenoid phytoalexin in rice cells. J Plant Physiol. 2015, 173, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Bi, Y. Both HY5 and HYH are necessary regulators for low temperature-induced anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis seedlings. J Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Xiang, L.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, J.; Geng, C.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Shen, Q.; Yang, C.; Lan, X.; Chen, M.; Tang, K.; Liao, Z. ARTEMISININ BIOSYNTHESIS PROMOTING KINASE 1 positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis through phosphorylating AabZIP1. J Exp Bot. 2018, 69, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Zhong, Y.; Nï, T.H.W.; Fu, X.; Yan, T.; Shen, Q.; Chen, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, J.; Osbourn, A.; Li, L.; Tang, K. Light-Induced Artemisinin Biosynthesis Is Regulated by the bZIP Transcription Factor AaHY5 in Artemisia annua. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1747–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, W.; Shen, Q.; Fu, X.; Yan, T.; Shi, P.; Hao, X.; Ma, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W.; Tang, K. Interaction of bZIP transcription factor TGA6 with salicylic acid signaling modulates artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. J Exp Bot. 2019, 70, 3969–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Shi, M.; Fu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Kai, G. ABA-responsive transcription factor bZIP1 is involved in modulating biosynthesis of phenolic acids and tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza. J Exp Bot. 2020, 71, 5948–5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ji, A.; Luo, H.; Song, J. Genomic survey of bZIP transcription factor genes related to tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018, 8, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Wakamatsu, S.; Sakuta, M. Characterization of SBZ1, a soybean bZIP protein that binds to the chalcone synthase gene promoter. Plant Biotechnol. 2008, 25, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge, L.W.; Kaiser, A.; Lindsay, W.P.; Halkier, B.A.; Loake, G.J.; Doerner, P.; Dixon, R.A.; Lamb, C. Rapid stimulation of a soybean protein-serine kinase that phosphorylates a novel bZIP DNA-binding protein, G/HBF-1, during the induction of early transcription-dependent defenses. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anguraj, V.A.K.; Renaud, J.; Kagale, S.; Dhaubhadel, S. GmMYB176 Regulates Multiple Steps in Isoflavonoid Biosynthesis in Soybean. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, T.; Katayama-Ikegami, A.; Kobayashi, S.; Sato, A.; Kono, A.; Yonemori, K. Seasonal abscisic acid signal and a basic leucine zipper transcription factor, DkbZIP5, regulate proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in persimmon fruit. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibéril, Y.; Benhamron, S.; Memelink, J.; Giglioli-Guivarc'h, N.; Thiersault, M.; Boisson, B.; Doireau, P.; Gantet, P. Catharanthus roseus G-box binding factors 1 and 2 act as repressors of strictosidine synthase gene expression in cell cultures. Plant Mol Biol. 2001, 45, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, J.; Hillebrand, A.; Twyman, R.M.; Prüfer, D.; Schulze, G.C. Abscisic acid-dependent regulation of small rubber particle protein gene expression in Taraxacum brevicorniculatum is mediated by TbbZIP1. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, E.S.; Lee, JG.; Chung, I.M.; Yu, CY. Changes of phenolic compounds in LebZIP2-overexpressing transgenic plants. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2019, 56, 484–491. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M.; Du, Z.; Hua, Q.; Kai, G. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis of bZIP2 in Salvia miltiorrhiza leads to promoted phenolic acid biosynthesis. Ind Crops Prod. 2021, 167, 113560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matousek, J.; Kocábek, T.; Patzak, J.; Stehlík, J.; Füssy, Z.; Krofta, K.; Heyerick, A.; Roldán-Ruiz, I.; Maloukh, L.; De Keukeleire, D. Cloning and molecular analysis of HlbZip1 and HlbZip2 transcription factors putatively involved in the regulation of the lupulin metabolome in hop (Humulus lupulus L.). J Agric Food Chem. 2010, 58, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malacarne, G.; Coller, E.; Czemmel, S.; Vrhovsek, U.; Engelen, K.; Goremykin, V.; Bogs, J.; Moser, C. The grapevine VvibZIPC22 transcription factor is involved in the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis. J Exp Bot. 2016, 67, 3509–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, A.; Daszkowska-Golec, A.; Kurowska, M.; Szarejko, I. Barley ABI5 (Abscisic Acid INSENSITIVE 5) Is Involved in Abscisic Acid-Dependent Drought Response. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, P.; Chen, G.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Lian, H. FvbHLH9 Functions as a Positive Regulator of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis by Forming a HY5-bHLH9 Transcription Complex in Strawberry Fruits. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, T.; Ikegami, A.; Tsujimoto, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Sato, A.; Kono, A.; Yonemori, K. DkMyb4 is a Myb transcription factor involved in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in persimmon fruit. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 2028–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, T.; Katayama, I.A.; Kobayashi, S.; Sato, A.; Kono, A.; Yonemori, K. Seasonal abscisic acid signal and a basic leucine zipper transcription factor, DkbZIP5, regulate proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in persimmon fruit. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.P.; Yao, J.F.; Xu, R.R.; You, C.X.; Wang, X.F.; Hao, Y.J. Apple bZIP transcription factor MdbZIP44 regulates abscisic acid-promoted anthocyanin accumulation. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 2678–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.P.; Zhang, X.W.; Liu, Y.J.; Wang, X.F.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. ABI5 regulates ABA-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis by modulating the MYB1-bHLH3 complex in apple. J Exp Bot. 2021, 72, 1460–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Su, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, G.; Allan, A.C.; Ampomah, D.C.; Shu, Q.; Lin, W.K.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J. The involvement of PybZIPa in light-induced anthocyanin accumulation via the activation of PyUFGT through binding to tandem G-boxes in its promoter. Hortic Res. 2019, 6, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; He, Y.; Li, G.; Ma, W.; Huang, X.; Su, J. Transcription factor PyHY5 binds to the promoters of PyWD40 and PyMYB10 and regulates its expression in red pear 'Yunhongli No. 1'. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020, 154, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, S.; Xu, Y.H.; Ge, Z.; Sui, C.; Wei, J. Overexpression of BcbZIP134 negatively regulates the biosynthesis of saikosaponins. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2019, 137, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Meng, L.H.; Gao, Y.; Grierson, D.; Fu, D.Q. Manipulation of Light Signal Transduction Factors as a Means of Modifying Steroidal Glycoalkaloids Accumulation in Tomato Leaves. Front Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Yu, F. A bZIP transcription factor, CaLMF, mediated light-regulated camptothecin biosynthesis in Camptotheca acuminata. Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).