Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

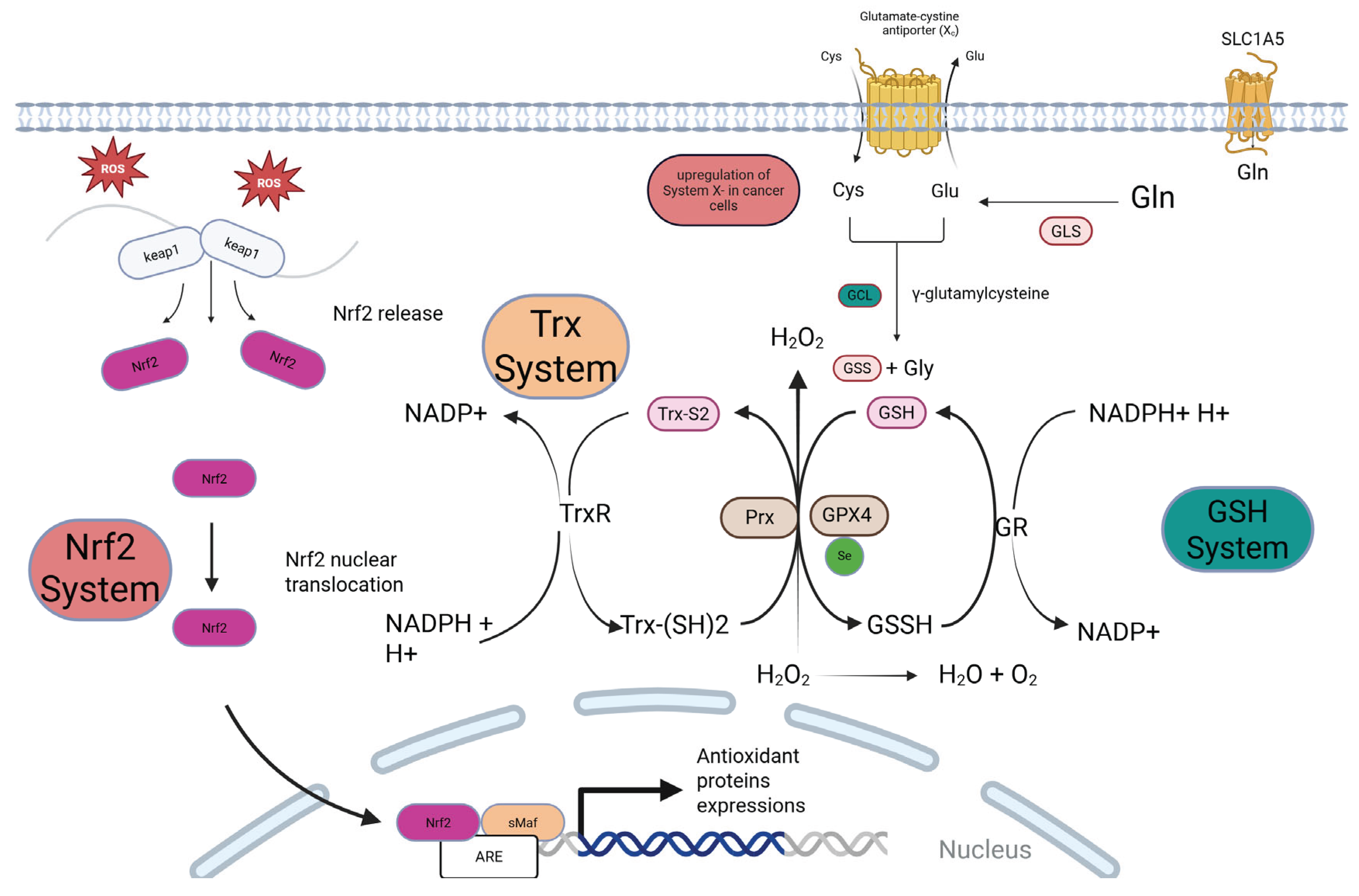

2. Architects of the Malignant Redox State

2.1. ROS Sources

2.2. Antioxidant Defense of Cancer Cells

2.2.1. The Nrf2-Keap1 Axis

2.2.2. The Glutathione (GSH) System

2.2.3. The Thioredoxin (Trx) System

3. Redox Regulation of Cancer Hallmarks

3.1. Sustaining Proliferation and Evading Growth Suppressors via PTP Inactivation

3.2. Evading Growth Suppressors via Oxidation and Inactivation of Tumor Suppressors Like PTEN and p53.

4. The Tumor Microenvironment (TME):

4.1. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs)

4.2. Immune Cells: The Redox-Mediated Suppression of Anti-Tumor Immunity

5. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Redox Vulnerabilities in Cancer

5.1. Therapeutic ROS Induction

5.1.1. Conventional Therapies

5.1.2. Targeted Pro-Oxidant Drugs

5.2. Targeting Antioxidant Capacity

5.2.1. Nrf2 Inhibitors

5.2.2. GSH & System Xc- Inhibitor

5.2.3. Trx System Inhibitor

6. Emerging Frontiers and Grand Challenges

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lennicke, C. and H.M. Cochemé, Redox metabolism: ROS as specific molecular regulators of cell signaling and function. Molecular Cell, 2021. 81(18): p. 3691-3707. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. and G.E. Mann, Discussion on current topics in redox biology and future directions/ year in review. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2025. 233: p. S18. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H., R.J. Mailloux, and U. Jakob, Fundamentals of redox regulation in biology. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2024. 25(9): p. 701-719. [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, S., et al., Role of ROS and RNS Sources in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2016. 2016(1): p. 1245049.

- Pizzino, G., et al., Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2017. 2017: p. 8416763. [CrossRef]

- Kong, H. and N.S. Chandel, Regulation of redox balance in cancer and T cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2018. 293(20): p. 7499-7507. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.C. and K.H. Vousden, The role of ROS in tumour development and progression. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2022. 22(5): p. 280-297. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R., et al., Dual role of reactive oxygen species and their application in cancer therapy. Journal of Cancer, 2021. 12(18): p. 5543. [CrossRef]

- Kennel, K.B. and F.R. Greten, Immune cell-produced ROS and their impact on tumor growth and metastasis. Redox Biology, 2021. 42: p. 101891. [CrossRef]

- Moloney, J.N. and T.G. Cotter, ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 2018. 80: p. 50-64. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., et al., Cancer metabolism: the role of ROS in DNA damage and induction of apoptosis in cancer cells. Metabolites, 2023. 13(7): p. 796. [CrossRef]

- de Sá Junior, P.L., et al., The Roles of ROS in Cancer Heterogeneity and Therapy. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2017. 2017(1): p. 2467940. [CrossRef]

- Kirtonia, A., G. Sethi, and M. Garg, The multifaceted role of reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2020. 77(22): p. 4459-4483. [CrossRef]

- Marengo, B., et al., Redox homeostasis and cellular antioxidant systems: crucial players in cancer growth and therapy. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2016. 2016(1): p. 6235641. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, G., et al., Overview and Sources of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the Reproductive System, in Oxidative Stress in Human Reproduction: Shedding Light on a Complicated Phenomenon, A. Agarwal, et al., Editors. 2017, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 1-16.

- Madkour, L.H., Function of reactive oxygen species (ROS) inside the living organisms and sources of oxidants. Pharm. Sci. Anal. Res. J, 2019. 2: p. 180023.

- Bardaweel, S.K., et al., Reactive Oxygen Species: the Dual Role in Physiological and Pathological Conditions of the Human Body. Eurasian J Med, 2018. 50(3): p. 193-201. [CrossRef]

- Reczek, C.R. and N.S. Chandel, The Two Faces of Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer. Annual Review of Cancer Biology, 2017. 1(Volume 1, 2017): p. 79-98. [CrossRef]

- Reczek, C.R. and N.S. Chandel, ROS-dependent signal transduction. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2015. 33: p. 8-13. [CrossRef]

- Averill-Bates, D., Reactive oxygen species and cell signaling. Review. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research, 2024. 1871(2): p. 119573.

- Sarniak, A., et al., Endogenous mechanisms of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. Postepy higieny i medycyny doswiadczalnej (Online), 2016. 70: p. 1150-1165. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., et al., Mitochondria and Mitochondrial ROS in Cancer: Novel Targets for Anticancer Therapy. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2016. 231(12): p. 2570-2581. [CrossRef]

- Okon, I.S. and M.-H. Zou, Mitochondrial ROS and cancer drug resistance: Implications for therapy. Pharmacological Research, 2015. 100: p. 170-174. [CrossRef]

- Xing, F., et al., The relationship of redox with hallmarks of cancer: the importance of homeostasis and context. Frontiers in oncology, 2022. 12: p. 862743. [CrossRef]

- Galaris, D., V. Skiada, and A. Barbouti, Redox signaling and cancer: The role of “labile” iron. Cancer Letters, 2008. 266(1): p. 21-29.

- Grasso, D., et al., Mitochondria in cancer. Cell Stress, 2020. 4(6): p. 114-146.

- Zhao, Y., et al., Cancer Metabolism: The Role of ROS in DNA Damage and Induction of Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. Metabolites, 2023. 13(7): p. 796. [CrossRef]

- Magnani, F. and A. Mattevi, Structure and mechanisms of ROS generation by NADPH oxidases. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 2019. 59: p. 91-97. [CrossRef]

- Pecchillo Cimmino, T., et al., NOX Dependent ROS Generation and Cell Metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023. 24(3): p. 2086. [CrossRef]

- Ogboo, B.C., et al., Architecture of the NADPH oxidase family of enzymes. Redox Biology, 2022. 52: p. 102298. [CrossRef]

- Quilaqueo-Millaqueo, N., et al., NOX proteins and ROS generation: role in invadopodia formation and cancer cell invasion. Biological Research, 2024. 57(1): p. 98. [CrossRef]

- Fukai, T. and M. Ushio-Fukai, Cross-Talk between NADPH Oxidase and Mitochondria: Role in ROS Signaling and Angiogenesis. Cells, 2020. 9(8): p. 1849. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, C.L. and L.K. Madan, Chapter Two - Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase regulation by Reactive Oxygen Species, in Advances in Cancer Research, D. Townsend and E. Schmidt, Editors. 2024, Academic Press. p. 45-74.

- Zeeshan, H.M., et al., Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Associated ROS. Int J Mol Sci, 2016. 17(3): p. 327. [CrossRef]

- Kritsiligkou, P., et al., Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress–induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) are detrimental for the fitness of a thioredoxin reductase mutant. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2018. 293(31): p. 11984-11995. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., et al., Endoplasmic reticulum stress: molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2023. 8(1): p. 352. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., et al., Stress Management: How the Endoplasmic Reticulum Mitigates Protein Misfolding and Oxidative Stress by the Dual Role of Glutathione Peroxidase 8. Biomolecules, 2025. 15(6): p. 847. [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, K.R., et al., The aftermath of the interplay between the endoplasmic reticulum stress response and redox signaling. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 2021. 53(2): p. 151-167. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S., W.-J. Chng, and J. Zhou, Crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress: a dynamic duo in multiple myeloma. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2021. 78(8): p. 3883-3906. [CrossRef]

- Ellgaard, L., et al., Co-and post-translational protein folding in the ER. Traffic, 2016. 17(6): p. 615-638.

- Gao, L., et al., A possible connection between reactive oxygen species and the unfolded protein response in lens development: From insight to foresight. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2022. Volume 10 - 2022. [CrossRef]

- Snezhkina, A.V., et al., ROS generation and antioxidant defense systems in normal and malignant cells. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2019. 2019(1): p. 6175804. [CrossRef]

- Poillet-Perez, L., et al., Interplay between ROS and autophagy in cancer cells, from tumor initiation to cancer therapy. Redox biology, 2015. 4: p. 184-192. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S., et al., Reactive oxygen species: a key constituent in cancer survival. Biomarker insights, 2018. 13: p. 1177271918755391. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D., Thirty years of NRF2: advances and therapeutic challenges. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2025: p. 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Islas, C.A. and P.D. Maldonado, Canonical and non-canonical mechanisms of Nrf2 activation. Pharmacological Research, 2018. 134: p. 92-99. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.J., et al., Brusatol, an NRF2 inhibitor for future cancer therapeutic. Cell & Bioscience, 2019. 9(1): p. 45. [CrossRef]

- Lau, A., et al., Arsenic-Mediated Activation of the Nrf2-Keap1 Antioxidant Pathway. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology, 2013. 27(2): p. 99-105.

- Suzuki, T. and M. Yamamoto, Molecular basis of the Keap1–Nrf2 system. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2015. 88: p. 93-100.

- Richardson, B.G., et al., Non-electrophilic modulators of the canonical Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2015. 25(11): p. 2261-2268. [CrossRef]

- Katsuragi, Y., Y. Ichimura, and M. Komatsu, Regulation of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway by p62/SQSTM1. Current Opinion in Toxicology, 2016. 1: p. 54-61. [CrossRef]

- He, F., X. Ru, and T. Wen, NRF2, a transcription factor for stress response and beyond. International journal of molecular sciences, 2020. 21(13): p. 4777. [CrossRef]

- Menegon, S., A. Columbano, and S. Giordano, The Dual Roles of NRF2 in Cancer. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 2016. 22(7): p. 578-593. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P., et al., The Nrf2 inhibitor brusatol is a potent antitumour agent in an orthotopic mouse model of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget, 2018. 9(43): p. 27104-27116. [CrossRef]

- Stępkowski, T.M. and M.K. Kruszewski, Molecular cross-talk between the NRF2/KEAP1 signaling pathway, autophagy, and apoptosis. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2011. 50(9): p. 1186-1195. [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, S., et al., The KEAP1-NRF2 pathway: Targets for therapy and role in cancer. Redox Biology, 2023. 63: p. 102726. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K. and M. Yamamoto, The KEAP1-NRF2 System in Cancer. Front Oncol, 2017. 7: p. 85.

- Evans, J.P., et al., The Nrf2 inhibitor brusatol is a potent antitumour agent in an orthotopic mouse model of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget, 2018. 9(43): p. 27104. [CrossRef]

- Sporn, M.B. and K.T. Liby, NRF2 and cancer: the good, the bad and the importance of context. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2012. 12(8): p. 564-571. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., et al., Reactive oxygen species and NRF2 signaling, friends or foes in cancer? Biomolecules, 2023. 13(2): p. 353. [CrossRef]

- Balendiran, G.K., R. Dabur, and D. Fraser, The role of glutathione in cancer. Cell Biochemistry and Function, 2004. 22(6): p. 343-352.

- Balendiran, G.K., R. Dabur, and D. Fraser, The role of glutathione in cancer. Cell Biochemistry and Function: Cellular biochemistry and its modulation by active agents or disease, 2004. 22(6): p. 343-352.

- Kennedy, L., et al., Role of Glutathione in Cancer: From Mechanisms to Therapies. Biomolecules, 2020. 10(10): p. 1429. [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, E.V. and L.A. Gavriliuk, Glutathione Synthesis in Cancer Cells. Biochemistry (Moscow), 2020. 85(8): p. 895-907.

- Lv, H., et al., Unraveling the Potential Role of Glutathione in Multiple Forms of Cell Death in Cancer Therapy. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2019. 2019(1): p. 3150145. [CrossRef]

- Asantewaa, G. and I.S. Harris, Glutathione and its precursors in cancer. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2021. 68: p. 292-299.

- Bansal, A. and M.C. Simon, Glutathione metabolism in cancer progression and treatment resistance. Journal of Cell Biology, 2018. 217(7): p. 2291-2298. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-r., W.-t. Zhu, and D.-s. Pei, System Xc−: A key regulatory target of ferroptosis in cancer. Investigational New Drugs, 2021. 39(4): p. 1123-1131. [CrossRef]

- Bonifácio, V.D., et al., Cysteine metabolic circuitries: druggable targets in cancer. British journal of cancer, 2021. 124(5): p. 862-879. [CrossRef]

- Sarıkaya, E. and S. Doğan, Glutathione Peroxidase in Health. Glutathione system and oxidative stress in health and disease, 2020. 49.

- Seibt, T.M., B. Proneth, and M. Conrad, Role of GPX4 in ferroptosis and its pharmacological implication. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2019. 133: p. 144-152. [CrossRef]

- Maiorino, M., M. Conrad, and F. Ursini, GPx4, Lipid Peroxidation, and Cell Death: Discoveries, Rediscoveries, and Open Issues. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 2017. 29(1): p. 61-74. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A. and S. Gupta, The multifaceted role of glutathione S-transferases in cancer. Cancer Letters, 2018. 433: p. 33-42. [CrossRef]

- Averill-Bates, D.A., Chapter Five - The antioxidant glutathione, in Vitamins and Hormones, G. Litwack, Editor. 2023, Academic Press. p. 109-141.

- Fletcher, M.E., et al., Influence of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) inhibition on lung epithelial cell injury: role of oxidative stress and metabolism. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 2015. 308(12): p. L1274-L1285. [CrossRef]

- Averill-Bates, D.A., The antioxidant glutathione, in Vitamins and hormones. 2023, Elsevier. p. 109-141.

- Wu, C., et al., Blocking glutathione regeneration: Inorganic NADPH oxidase nanozyme catalyst potentiates tumoral ferroptosis. Nano Today, 2022. 46: p. 101574. [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.-Q., et al., NADPH homeostasis in cancer: functions, mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2020. 5(1): p. 231. [CrossRef]

- Ghareeb, H. and N. Metanis, The Thioredoxin System: A Promising Target for Cancer Drug Development. Chemistry – A European Journal, 2020. 26(45): p. 10175-10184. [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa, A., Thioredoxin and redox signaling: Roles of the thioredoxin system in control of cell fate. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics, 2017. 617: p. 101-105. [CrossRef]

- Ghareeb, H. and N. Metanis, The thioredoxin system: a promising target for cancer drug development. Chemistry–A European Journal, 2020. 26(45): p. 10175-10184. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.A., et al., The thioredoxin system of mammalian cells and its modulators. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(7): p. 1757. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., et al., Thioredoxin signaling pathways in cancer. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 2023. 38(4): p. 403-424.

- Mohammadi, F., et al., The thioredoxin system and cancer therapy: a review. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology, 2019. 84(5): p. 925-935. [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, M., et al., The role of the thioredoxin detoxification system in cancer progression and resistance. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 2022. 9: p. 883297. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. and Robert A. Weinberg, Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell, 2011. 144(5): p. 646-674.

- Zhang, J., et al., Targeting the thioredoxin system for cancer therapy. Trends in pharmacological sciences, 2017. 38(9): p. 794-808. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., et al., ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2016. 2016(1): p. 4350965.

- Mittler, R., ROS Are Good. Trends in Plant Science, 2017. 22(1): p. 11-19. [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.G., H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science, 2006. 312(5782): p. 1882-1883. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., et al., Human protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B): from structure to clinical inhibitor perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022. 23(13): p. 7027. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.P., R.J. Arai, and L.R. Travassos, Protein tyrosine phosphorylation and protein tyrosine nitration in redox signaling. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 2008. 10(5): p. 843-890. [CrossRef]

- Östman, A., C. Hellberg, and F.D. Böhmer, Protein-tyrosine phosphatases and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2006. 6(4): p. 307-320.

- Spangle, J.M. and T.M. Roberts, Epigenetic regulation of RTK signaling. Journal of Molecular Medicine, 2017. 95(8): p. 791-798. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. and I. Rhee, Important roles of protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN12 in tumor progression. Pharmacological Research, 2019. 144: p. 73-78. [CrossRef]

- Dustin, C.M., et al., Redox regulation of tyrosine kinase signalling: more than meets the eye. The Journal of Biochemistry, 2019. 167(2): p. 151-163. [CrossRef]

- van der Vliet, A., C.M. Dustin, and D.E. Heppner, Chapter 16 - Redox regulation of protein kinase signaling, in Oxidative Stress, H. Sies, Editor. 2020, Academic Press. p. 287-313.

- Ray, P.D., B.-W. Huang, and Y. Tsuji, Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cellular Signalling, 2012. 24(5): p. 981-990. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., et al., Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance in malignant tumors: molecular mechanisms and future perspective. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2022. 7(1): p. 329. [CrossRef]

- Trinh, V.H., et al., Redox Regulation of PTEN by Reactive Oxygen Species: Its Role in Physiological Processes. Antioxidants, 2024. 13(2): p. 199. [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, A., et al., PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Molecular Cancer, 2023. 22(1): p. 138. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L., J. Wei, and P. Liu, Attacking the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway for targeted therapeutic treatment in human cancer. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 2022. 85: p. 69-94. [CrossRef]

- Noorolyai, S., et al., The relation between PI3K/AKT signalling pathway and cancer. Gene, 2019. 698: p. 120-128. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., et al., PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and its role in cancer therapeutics: are we making headway? Frontiers in oncology, 2022. 12: p. 819128. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., et al., Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2021. 6(1): p. 425. [CrossRef]

- Vurusaner, B., G. Poli, and H. Basaga, Tumor suppressor genes and ROS: complex networks of interactions. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2012. 52(1): p. 7-18. [CrossRef]

- Son, Y., et al., Mitogen-activated protein kinases and reactive oxygen species: how can ROS activate MAPK pathways? Journal of signal transduction, 2011. 2011(1): p. 792639. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, R., R. Satoh, and T. Takasaki, ERK: A Double-Edged Sword in Cancer. ERK-Dependent Apoptosis as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer. Cells, 2021. 10(10): p. 2509. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.K., et al., Dual-specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6): a review of its molecular characteristics and clinical relevance in cancer. Cancer biology & medicine, 2018. 15(1): p. 14-28.

- Bellezza, I., et al., ROS-independent Nrf2 activation in prostate cancer. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(40): p. 67506. [CrossRef]

- Lingappan, K., NF-κB in oxidative stress. Current Opinion in Toxicology, 2018. 7: p. 81-86.

- Morgan, M.J. and Z.-g. Liu, Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell research, 2011. 21(1): p. 103-115. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., et al., HIFs, angiogenesis, and cancer. Journal of cellular biochemistry, 2013. 114(5): p. 967-974. [CrossRef]

- Chio, I.I.C. and D.A. Tuveson, ROS in cancer: the burning question. Trends in molecular medicine, 2017. 23(5): p. 411-429. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G., et al., Redox signaling-mediated tumor extracellular matrix remodeling: pleiotropic regulatory mechanisms. Cellular Oncology, 2024. 47(2): p. 429-445. [CrossRef]

- Giannoni, E., M. Parri, and P. Chiarugi, EMT and oxidative stress: a bidirectional interplay affecting tumor malignancy. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 2012. 16(11): p. 1248-1263. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U., K. Fatima, and F. Malik, Understanding the cell survival mechanism of anoikis-resistant cancer cells during different steps of metastasis. Clinical & experimental metastasis, 2022. 39(5): p. 715-726. [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, D., et al., Inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 by reactive oxygen species contributes to cellular antioxidant responses. Science, 2011. 334(6060): p. 1278-1283. [CrossRef]

- David, S.S., V.L. O'Shea, and S. Kundu, Base-excision repair of oxidative DNA damage. Nature, 2007. 447(7147): p. 941-950. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.M. and M.C. Simon, The tumor microenvironment. Current Biology, 2020. 30(16): p. R921-R925.

- Arneth, B., Tumor microenvironment. Medicina, 2019. 56(1): p. 15.

- Wang, M., et al., Role of tumor microenvironment in tumorigenesis. J Cancer, 2017. 8(5): p. 761-773. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M., et al., Effect of tumor cells and tumor microenvironment on NK-cell function. European journal of immunology, 2014. 44(6): p. 1582-1592. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.S., et al., The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor progression. Cancers, 2021. 13(6): p. 1399. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. and M. Zeisberg, Fibroblasts in cancer. Nature reviews cancer, 2006. 6(5): p. 392-401.

- Li, Z., C. Sun, and Z. Qin, Metabolic reprogramming of cancer-associated fibroblasts and its effect on cancer cell reprogramming. Theranostics, 2021. 11(17): p. 8322-8336. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., et al., Role of the tumor microenvironment in tumor progression and the clinical applications (Review). Oncol Rep, 2016. 35(5): p. 2499-2515. [CrossRef]

- Nurmik, M., et al., In search of definitions: Cancer-associated fibroblasts and their markers. International Journal of Cancer, 2020. 146(4): p. 895-905. [CrossRef]

- Liberti, M.V. and J.W. Locasale, The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 2016. 41(3): p. 211-218. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. and S. Bera, CAF cellular glycolysis: linking cancer cells with the microenvironment. Tumor Biology, 2016. 37(7): p. 8503-8514. [CrossRef]

- Wilde, L., et al., Metabolic coupling and the Reverse Warburg Effect in cancer: Implications for novel biomarker and anticancer agent development. Seminars in Oncology, 2017. 44(3): p. 198-203. [CrossRef]

- Liang, L., et al., ‘Reverse Warburg effect’ of cancer-associated fibroblasts (Review). Int J Oncol, 2022. 60(6): p. 67.

- Sica, A. and M. Massarotti, Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer and autoimmunity. Journal of Autoimmunity, 2017. 85: p. 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., M. Li, and Q. Jia, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Key immunosuppressive regulators and therapeutic targets in cancer. Pathology - Research and Practice, 2023. 248: p. 154711. [CrossRef]

- Law, A.M., F. Valdes-Mora, and D. Gallego-Ortega, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as a therapeutic target for cancer. Cells, 2020. 9(3): p. 561. [CrossRef]

- Ohl, K. and K. Tenbrock, Reactive Oxygen Species as Regulators of MDSC-Mediated Immune Suppression. Frontiers in Immunology, 2018. Volume 9 - 2018. [CrossRef]

- Parri, M. and P. Chiarugi, Redox molecular machines involved in tumor progression. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 2013. 19(15): p. 1828-1845. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.W.L., P. Ghode, and D.S.T. Ong, Redox regulation of cell state and fate. Redox biology, 2019. 25: p. 101056. [CrossRef]

- Panieri, E. and M.M. Santoro, ROS homeostasis and metabolism: a dangerous liason in cancer cells. Cell Death & Disease, 2016. 7(6): p. e2253-e2253. [CrossRef]

- Sia, J., et al., Molecular Mechanisms of Radiation-Induced Cancer Cell Death: A Primer. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2020. Volume 8 - 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jaffray, D.A. and M.K. Gospodarowicz, Radiation Therapy for Cancer. 2015, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, Washington (DC).

- Rahman, W.N., et al., Enhancement of radiation effects by gold nanoparticles for superficial radiation therapy, in Nanomedicine in Cancer. 2017, Jenny Stanford Publishing. p. 737-752.

- Kim, W., et al., Cellular stress responses in radiotherapy. Cells, 2019. 8(9): p. 1105. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-s., H.-j. Wang, and H.-l. Qian, Biological effects of radiation on cancer cells. Military Medical Research, 2018. 5(1): p. 20. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.H.W. and M.T. Kuo, Improving radiotherapy in cancer treatment: Promises and challenges. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(37): p. 62742-62758. [CrossRef]

- Baskar, R., et al., Biological response of cancer cells to radiation treatment. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 2014. Volume 1 - 2014. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. and Z. Guo, Targeting and delivery of platinum-based anticancer drugs. Chemical Society Reviews, 2013. 42(1): p. 202-224. [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C. and S. Maggini, Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients, 2017. 9(11): p. 1211. [CrossRef]

- Böttger, F., et al., High-dose intravenous vitamin C, a promising multi-targeting agent in the treatment of cancer. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 2021. 40(1): p. 343. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., The Effects of High Concentrations of Vitamin C on Cancer Cells. Nutrients, 2013. 5(9): p. 3496-3505. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, B., et al., Targeting cancer vulnerabilities with high-dose vitamin C. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2019. 19(5): p. 271-282. [CrossRef]

- LEE, S.J., et al., Effect of High-dose Vitamin C Combined With Anti-cancer Treatment on Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer Research, 2019. 39(2): p. 751-758. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S., et al., Exploring Therapeutic Potential of Catalase: Strategies in Disease Prevention and Management. Biomolecules, 2024. 14(6): p. 697. [CrossRef]

- Suhail, N., et al., Effect of vitamins C and E on antioxidant status of breast-cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics, 2012. 37(1): p. 22-26. [CrossRef]

- Giansanti, M., et al., High-Dose Vitamin C: Preclinical Evidence for Tailoring Treatment in Cancer Patients. Cancers, 2021. 13(6): p. 1428. [CrossRef]

- VOLLBRACHT, C., et al., Intravenous Vitamin C Administration Improves Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients during Chemo-/Radiotherapy and Aftercare: Results of a Retrospective, Multicentre, Epidemiological Cohort Study in Germany. In Vivo, 2011. 25(6): p. 983-990.

- Hoonjan, M., V. Jadhav, and P. Bhatt, Arsenic trioxide: insights into its evolution to an anticancer agent. JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry, 2018. 23(3): p. 313-329. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., et al., An overview of arsenic trioxide-involved combined treatment algorithms for leukemia: basic concepts and clinical implications. Cell Death Discovery, 2023. 9(1): p. 266. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Q., Y. Jiang, and H. Naranmandura, Therapeutic strategy of arsenic trioxide in the fight against cancers and other diseases. Metallomics, 2020. 12(3): p. 326-336. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y., et al., Arsenic trioxide-induced apoptosis through oxidative stress in cells of colon cancer cell lines. Life Sciences, 2002. 70(19): p. 2253-2269. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. and Y. Zeng, A candidate for lung cancer treatment: arsenic trioxide. Clinical and Translational Oncology, 2019. 21(9): p. 1115-1126. [CrossRef]

- Parama, D., et al., The promising potential of piperlongumine as an emerging therapeutics for cancer. Exploration of Targeted Anti-Tumor Therapy, 2021. 2(4): p. 323. [CrossRef]

- Song, X., et al., Piperlongumine induces apoptosis in human melanoma cells via reactive oxygen species mediated mitochondria disruption. Nutrition and cancer, 2018. 70(3): p. 502-511. [CrossRef]

- Karki, K., et al., Piperlongumine induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent downregulation of specificity protein transcription factors. Cancer prevention research, 2017. 10(8): p. 467-477. [CrossRef]

- Ju, S., et al., Oxidative Stress and Cancer Therapy: Controlling Cancer Cells Using Reactive Oxygen Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024. 25(22): p. 12387. [CrossRef]

- Pouremamali, F., et al., An update of Nrf2 activators and inhibitors in cancer prevention/promotion. Cell Communication and Signaling, 2022. 20(1): p. 100. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, H. and H. Motohashi, NRF2 addiction in cancer cells. Cancer Science, 2018. 109(4): p. 900-911. [CrossRef]

- Xi, W., et al., Brusatol’s anticancer activity and its molecular mechanism: a research update. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 2024. 76(7): p. 753-762. [CrossRef]

- He, T., et al., Brusatol: A potential sensitizing agent for cancer therapy from Brucea javanica. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2023. 158: p. 114134. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., et al., Natural Nrf2 inhibitors: a review of their potential for cancer treatment. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 2023. 19(10): p. 3029. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.J., et al., Brusatol, an NRF2 inhibitor for future cancer therapeutic. Cell Biosci, 2019. 9: p. 45. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., et al., Small Molecule Inhibitor of NRF2 Selectively Intervenes Therapeutic Resistance in KEAP1-Deficient NSCLC Tumors. ACS Chemical Biology, 2016. 11(11): p. 3214-3225. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., et al., ML385, an Nrf2 inhibitor, synergically enhanced celastrol triggered endoplasmic reticulum stress in lung cancer cells. ACS omega, 2024. 9(43): p. 43697-43705. [CrossRef]

- Kachadourian, R. and B.J. Day, Flavonoid-induced glutathione depletion: potential implications for cancer treatment. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2006. 41(1): p. 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, E. and L. Gavriliuk, Glutathione synthesis in cancer cells. Biochemistry (Moscow), 2020. 85(8): p. 895-907.

- Liu, M., et al., Hollow Gold Nanoparticles Loaded with L-Buthionine-Sulfoximine as a Novel Nanomedicine for In Vitro Cancer Cell Therapy. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2021. 2021(1): p. 3595470. [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, S., et al., Low tumor glutathione level as a sensitivity marker for glutamate-cysteine ligase inhibitors. Oncology Letters, 2018. 15(6): p. 8735-8743. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., et al., Oxygen-deficient BiOCl combined with L-buthionine-sulfoximine synergistically suppresses tumor growth through enhanced singlet oxygen generation under ultrasound irradiation. Small, 2022. 18(9): p. 2104550. [CrossRef]

- Jyotsana, N., K.T. Ta, and K.E. DelGiorno, The role of cystine/glutamate antiporter SLC7A11/xCT in the pathophysiology of cancer. Frontiers in oncology, 2022. 12: p. 858462. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D., et al., Novel analogs of sulfasalazine as system xc− antiporter inhibitors: Insights from the molecular modeling studies. Drug development research, 2019. 80(6): p. 758-777. [CrossRef]

- Sato, M., et al., The ferroptosis inducer erastin irreversibly inhibits system xc− and synergizes with cisplatin to increase cisplatin’s cytotoxicity in cancer cells. Scientific reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 968. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-T., et al., Insights into ferroptosis, a novel target for the therapy of cancer. Frontiers in oncology, 2022. 12: p. 812534. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q., Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 2013. 53(1): p. 401-426. [CrossRef]

- Stafford, W.C., Elucidation of thioredoxin reductase 1 as an anticancer drug target. 2015: Karolinska Institutet (Sweden).

- Chmelyuk, N., et al., Inhibition of Thioredoxin-Reductase by Auranofin as a Pro-Oxidant Anticancer Strategy for Glioblastoma: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2025. 26(5): p. 2084. [CrossRef]

- Gamberi, T., et al., Upgrade of an old drug: Auranofin in innovative cancer therapies to overcome drug resistance and to increase drug effectiveness. Medicinal Research Reviews, 2022. 42(3): p. 1111-1146. [CrossRef]

- Onodera, T., I. Momose, and M. Kawada, Potential anticancer activity of auranofin. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 2019. 67(3): p. 186-191. [CrossRef]

- Massai, L., et al., Auranofin and its analogs as prospective agents for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Cancer Drug Resistance, 2022. 5(1): p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.Y. and S.J. Dixon, Mechanisms of ferroptosis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2016. 73(11): p. 2195-2209.

- Xu, T., et al., Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis and its role in cancer therapy. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 2019. 23(8): p. 4900-4912. [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q., et al., Induction and application of ferroptosis in cancer therapy. Cancer Cell International, 2022. 22(1): p. 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., et al., Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: a novel approach to reversing drug resistance. Molecular cancer, 2022. 21(1): p. 47. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J., Ferroptosis: bug or feature? Immunological reviews, 2017. 277(1): p. 150-157. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., et al., Emerging mechanisms and targeted therapy of ferroptosis in cancer. Molecular Therapy, 2021. 29(7): p. 2185-2208. [CrossRef]

- Hassannia, B., P. Vandenabeele, and T. Vanden Berghe, Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer cell, 2019. 35(6): p. 830-849. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y., et al., Ferroptosis, a novel pharmacological mechanism of anti-cancer drugs. Cancer letters, 2020. 483: p. 127-136. [CrossRef]

- Gout, P., et al., Sulfasalazine, a potent suppressor of lymphoma growth by inhibition of the xc− cystine transporter: a new action for an old drug. Leukemia, 2001. 15(10): p. 1633-1640. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.-J., et al., System Xc−/GSH/GPX4 axis: An important antioxidant system for the ferroptosis in drug-resistant solid tumor therapy. Frontiers in pharmacology, 2022. 13: p. 910292. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S., et al., Targeting ferroptosis opens new avenues for the development of novel therapeutics. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 2023. 8(1): p. 372. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., H. Lu, and Y. Bai, Nrf2 in cancers: A double-edged sword. Cancer medicine, 2019. 8(5): p. 2252-2267.

- Collins, D.C., et al., Towards precision medicine in the clinic: from biomarker discovery to novel therapeutics. Trends in pharmacological sciences, 2017. 38(1): p. 25-40. [CrossRef]

- Malone, E.R., et al., Molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies. Genome medicine, 2020. 12(1): p. 8. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M., et al., Fluorescent chemical probes for accurate tumor diagnosis and targeting therapy. Chemical Society Reviews, 2017. 46(8): p. 2237-2271. [CrossRef]

- Gagan, J. and E.M. Van Allen, Next-generation sequencing to guide cancer therapy. Genome medicine, 2015. 7(1): p. 80.

- Chari, R.V., Targeted cancer therapy: conferring specificity to cytotoxic drugs. Accounts of chemical research, 2008. 41(1): p. 98-107. [CrossRef]

- Fan, D., et al., Nanomedicine in cancer therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2023. 8(1): p. 293.

- Gill, G.S., et al., Immune checkpoint inhibitors and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment: current challenges and strategies to overcome resistance. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology, 2025: p. 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y., L. Liu, and B. Shan, Future of immune checkpoint inhibitors: focus on tumor immune microenvironment. Annals of Translational Medicine, 2020. 8(17): p. 1095. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., et al., Reactive oxygen species regulate T cell immune response in the tumor microenvironment. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2016. 2016(1): p. 1580967. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., et al., Function of reactive oxygen species in myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Frontiers in immunology, 2023. 14: p. 1226443. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., et al., CD8+ T cell exhaustion and its regulatory mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment: Key to the success of immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology, 2024. 15: p. 1476904. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., et al., Oxidative stress in cancer immunotherapy: molecular mechanisms and potential applications. Antioxidants, 2022. 11(5): p. 853. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., et al., Nanomedicine embraces cancer radio-immunotherapy: mechanism, design, recent advances, and clinical translation. Chemical Society Reviews, 2023. 52(1): p. 47-96. [CrossRef]

| Hallmark of Cancer | Key redox-dependent mechanism(s) | Key molecular players | Downstream consequences | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.3 Resisting Cell Death | 1. Nrf2-driven transcription: Constitutive activation of Nrf2 drives the direct transcriptional upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes. 2. NF-κB activation: ROS activates the IKK complex, leading to IκBα degradation and the release of the NF-κB transcription factor. |

1. Nrf2, BCL-2, BCL-xL 2. ROS, IKKβ, IκBα, NF-κB (p65/p50), cIAP, XIAP |

Increased threshold for apoptosis and expression of pro-survival factors, leading to resistance to both endogenous death signals and cancer therapies. | [110,111,112] |

| 3.4 Inducing Angiogenesis | HIF-1α stabilization (Pseudohypoxia): ROS oxidizes the Fe(II) cofactor in prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) enzymes, inactivating them. Blocking the VHL-mediated degradation of HIF-1α, leading to its stabilization even under normoxic conditions. | ROS (H₂O₂), PHDs, VHL, HIF-1α, ARNT, VEGF | Constitutive transcription and secretion of pro-angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF), stimulating neovascularization to supply the growing tumor with oxygen and nutrients. | [113,114] |

| 3.5 Activating Invasion & Metastasis | 1. Matrix Remodeling: ROS-mediated activation of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) via the 'cysteine switch' mechanism. 2. EMT Induction: ROS acts as a second messenger for pro-metastatic pathways like TGF-β, driving the expression of EMT transcription factors. 3. Anoikis Resistance: The Nrf2-driven antioxidant shield protects detached cells from ROS-induced death, enabling survival during circulation. |

1. ROS, MMP-2, MMP-9 2. TGF-β, 3. Nrf2 |

Degradation of the basement membrane, acquisition of a migratory phenotype, and survival of circulating tumor cells, collectively promoting metastatic spread. | [115,116,117] |

| 3.6 Deregulating Cellular Metabolism | Enzymatic & transcriptional control: ROS directly oxidizes and modulates key metabolic enzymes (e.g., inhibiting PKM2 to divert flux to the PPP). Concurrently, ROS-stabilized HIF-1α transcriptionally upregulates glycolytic enzymes. | ROS, PKM2, HIF-1α, Glycolytic enzymes | Promotion of the Warburg Effect. This metabolic shift favors the production of biosynthetic precursors (for new cells) and NADPH (for antioxidant defense) over efficient ATP generation. |

[118] |

| 3.7 Genome Instability & Mutation | Direct DNA damage & repair inhibition: The hydroxyl radical (•OH) directly oxidizes DNA bases, creating mutagenic lesions like 8-oxoG. Concurrently, ROS can impair the function of DNA repair enzymes, preventing the correction of these lesions. | ROS (•OH), 8-oxoG, DNA bases, DNA repair enzymes | Increased somatic mutation rate and chromosomal instability, which fuels tumor evolution, intra-tumoral heterogeneity, and the development of drug resistance. | [119] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).