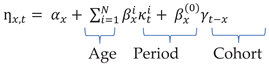

1. Introduction

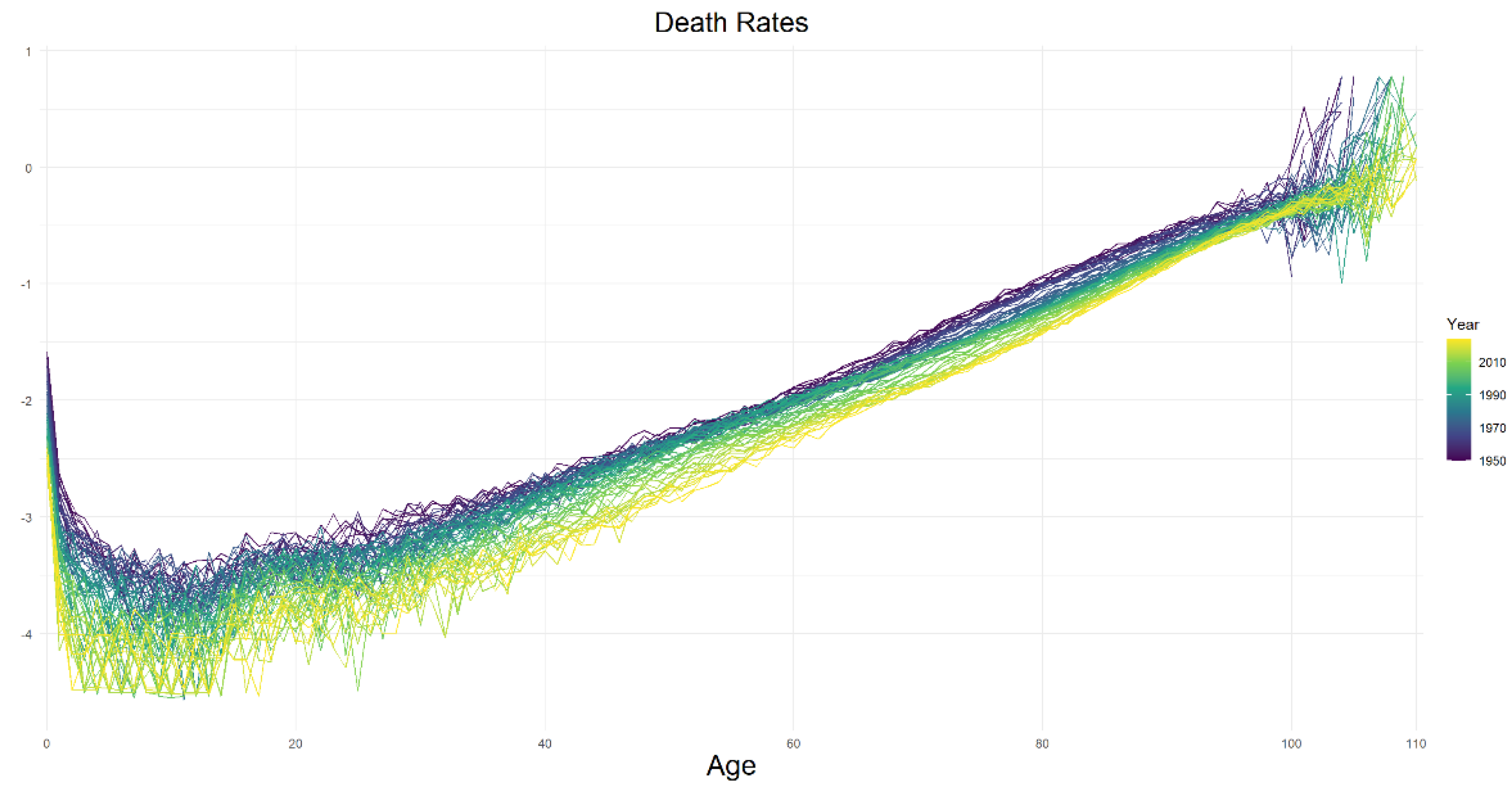

Mortality rates form an important variable of actuarial calculations surrounding the valuation and pricing in life insurance. An actuary uses this parameter in modelling for annuity products where the resulting output is extremely delicate to this particular input. When building the models, stochastic processes are overlaid around the deterministic output to capture the range of expected lifetime uncertainty, and this hybrid output subsequently feeds into both internal economic-capital calculations and the capital frameworks prescribed by regulators [

1]. It is crucial that under/over-estimated premiums may cause companies even bankrupt.

Forecasting mortality rates using mortality laws does not provide uncertainty regarding to the advances in mortality, since these models do not include any time component. Ultimately, the lack of an information on future mortality improvement may result in a faulty valuation of life insurance products. In addition, according to the Solvency II Framework Directive, a minimum amount of solvency capital should be maintained to prevent ruin [

2]. The capital is associated with the risk of future mortality being significantly different to that implied by life expectancy and thus should be projected stochastically. Therefore, the necessity of stochastic mortality models to quantify the mechanism of mortality progress over the upcoming years and the uncertainty in the forecasts is crucial [

3].

Making accurate forecasts of mortality pattern can inform not only demographers, but also researchers, governments and insurance companies about the future population size and longevity. Stochastic mortality modeling has become a pivotal area in current actuarial science and demography, offering valuable tools to predict mortality rates and to understand the complex trends and features behind human longevity. The ultimate goal of such models is to provide a more precise forecast of future mortality rates, for the purpose of allowing a better management of living more than expected of an individual. This exercise is crucial in the context of a number of applications, including the accurate pricing of insurance policies, construction plans of pension schemes, decision making of social security policies, and risk management in financial firms.

The Lee-Carter (LC) [

4] model, presented by Ronald Lee and Lawrence Carter in 1992, can be considered as leading among them which has become a benchmark model in mortality forecasting. Together with the original model it’s extensions also have been used by academics, private sector practitioners and several statistics institutes for nearly three decades [

5]. The LC model was earliest model taking the increased life expectancy trends into account which is related to the mortality improvement through time and has been used for forecasts of the United States social security system and federal budget [

6,

7]. In their paper [

4], Lee and Carter introduced a stochastic method established on age-specific and time-varying components to capture and forecast the age specific death rates of the US population. Despite its simplicity, the LC model has demonstrated excellent results for fitting mortality for several countries.

Building on this work, several important extensions have been implemented to address Lee-Carter model’s limitations and enhance the predictive power. To handle the fundamental assumption of homoscedasticity of errors, Brouhns et al. [

8] used LC model in an embedded Poisson regression framework. The Renshaw-Haberman (RH) [

9] improved the LC model accuracy by capturing unique mortality experience influenced by the birth year (cohort) of individuals. Another model is the generalized form of the RH model that is so called age-period-cohort (APC) model, first introduced by Hobcraft et al. [

10] and Osmond [

11] which became visible in the demographic and actuarial literature by Currie [

12]. A popular competitor of LC, a stochastic model to appear was the Cairns-Blake-Dowd (CBD) model [

13]. Unlike the logarithmic transformation in the LC model, the CBD model applies a logit transformation to the probability of death, which is captured as linear or quadratic function of age which is also called M7 with an additional cohort effect [

14]. Plat [

15] combines LC and CBD models to explain the entire age range. The models mentioned above can be classified as Generalized-Age-Period-Cohort (GAPC) models that can be written in generalized linear/non-linear model (glm/gnm) setting [

16]. In mortality modeling, glms/gnms are particularly useful for modeling mortality rates as a function of diverse explanatory variables such as age, sex, and cohort. Popular choices for the distribution of the outcome variable within glms include the binomial distribution for binary outcomes (e.g., survival vs. death) and the Poisson distribution for count data (e.g., number of deaths). The reason of choosing these mortality models is these models represent the vast majority of the stochastic mortality models together being a member of GAPC family [

17,

18]. For an extended overview, we refer Hunt and Blake [

19], Haberman and Renshaw [

20], Booth and Tickle [

21], Pitacco et al. [

22], Dowd et al. [

23], Zamzuri and Hui [

24] and Redzwan and Ramli [

25]. The framework of GAPC model is detailly explained in the next section.

Recently, actuarial and demographic research have begun benefit from artificial intelligence, specifically machine learning. Humans and animals, learn from experience, that’s precisely what machine learning methods do, they copy that concept while teaching computers how to use historical data.

These teaching methods are the algorithms those provide to learn the information from data which do not need any predetermined equations as a model [

26]

. Machine learning methods can be advantageous and learn from computations to make reliable and repeatable decisions and outcomes. It is a science not new, but newly invigorated. Stochastic mortality models, provide a parsimonious mechanism to capture systematic patterns in mortality through the scope of the features they contain. A prominent feature of age-period-cohort mortality models is the enforced smoothness and, as an extension, symmetry across age and over time to achieve model interpretability and tractability. However, mortuary dynamics in the real world are often asymmetrical in nature, based on heterogeneous shocks (i.e. pandemics, medical innovation, or region-specific health care reforms) and the nonlinear kinds of interactions that these models may not encapsulate [

21]. Tree based machine learning techniques, represent an alternative approach since they are able to flexibly detect local deviations, non-monocities, and symmetry-breaking effects in mortality data [

27].

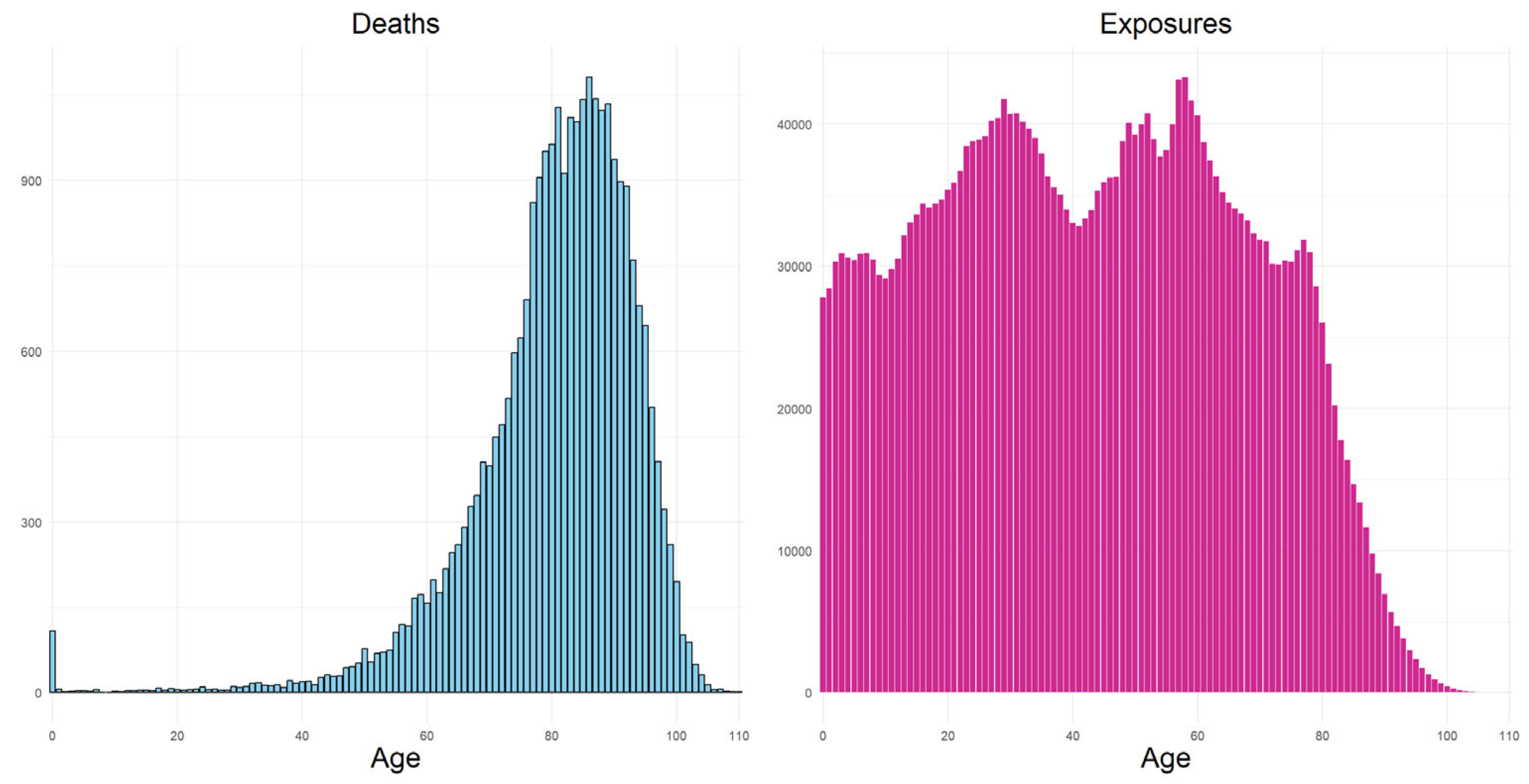

To be able to model the mortality rates (i.e. age specific death rates) at population level which is a numeric outcome, age, period, cohort and gender can be used as features. When there is a response variable (mortality rate) and features as mentioned, the problem can be addressed as a regression which can be used to uncover the underlying pattern of mortality. When it comes to forecasting, mortality models can still produce poor forecasts of mortality rates while fitting almost perfect on training data. Previous research focused on improving mortality rates under this framework and obtained promising results. In addition to the traditional perspective, tree-based algorithms also can be used for regression. When the data has several attributes and the target value is numerical, then using tree-based algorithms for regression is suitable. From this point of view, in this study, supervised learning methods: decision trees (DC), random forest (RF), gradient boosting (GB) and extreme gradient boosting (XGB) which are all tree-based algorithms are used, to re-estimate the age-specific death rates obtained from the generalized age-period-cohort mortality models.

Machine learning has been increasingly used in major fields in science but the demography does not come first. Probably the main reason is researchers find it difficult to interpret the results since machine learning had been still believed as a “black box” [

28]. This belief has come to end when Deprez et al. [

29] showed that using mortality models can produce improved results together with the machine learning techniques. Deprez et. al. [

29] used tree-based machine learning methods in a novel approach and encouraged researchers pondering more about machine learning along with demography. The work was based on improving the stochastic mortality model’s both fitting and forecasting ability by re-estimating the mortality rates using the features age, calendar year, gender and cohort with the help of machine learning techniques. Soon after, Levantesi and Pizzorusso [

28] presented a new approach based on the same idea in Deprez et. al. [

29] and used three mortality models to re-estimate the mortality rates obtained from the models. For forecasting the mortality rates, they treated the ratio of the observed and modeled number of deaths as mortality rates and used the same procedure of a mortality model. Staying within the context of improving mortality models’ accuracy using tree-based model, the research has gained momentum. Levantesi and Nigri [

30] improved the Lee-Carter predictive accuracy by using random forest and p-splines methods. Bjerre [

31] used tree-based methods to improve mortality rates using multi population data. Gyamerah et al. [

32] developed a hybrid LC+ML (machine learning) model where the Lee–Carter time index is forecast using a stack of learners. Qiao et al. [

33] applied a complex boosting/ensemble framework to long-term mortality. Across many countries, their method roughly halved the 20-year-forecast mean absolute percentage error compared to classic models. Finally, Levantesi et al. [

34], used contrast trees as a diagnostic tool to identify the regions where the model gives higher error and used Friedman’s [

35] boosting technique to improve the mortality model accuracy.

However, the research based on the idea of improving fitting and/or forecasting ability of a mortality model using machine learning techniques heavily depend on the pre-determined fitting and testing periods. Changing these periods mostly results in producing more errors than the original mortality model does. But then, focusing on the improving of fitting ability to rely on making better forecasts of mortality rates may not always a good idea especially when the historical mortality pattern that fitted to the model is not fully representative of the mortality pattern. The idea behind the out-of-sample tests helps solving this problem by determining model performance on unseen data with providing unbiased evaluation of how well the model can predict the future. From this point of view, in this study, we aimed to improve the forecasting ability of any mortality model using tree-based machine learning models by focusing on the out-of-sample testing. To be able to do it, we create a trade-off interval which allow the machine learning integrated model to give better forecasted mortality rates as an output without compromising the fitting quality of the re-estimated mortality rates over the fitting period at the same time. By doing so, using the procedure proposed in this study will enable to improve the mortality rates obtained from any mortality model. With this study, one can see the improved rates on the out-of-sample data without abandoning fitting period of the related mortality model.

The paper is organized as follows: in section 2, we briefly explain the GAPC models and the details of how to improve the forecasting ability of these mortality models. In the next section, we outline the four tree-based machine learning models in a regression setting. In section 4, we propose the procedure step by step and an application is illustrated. Finally, the discussion part is given.

3. Tree-Based Machine Learning Models

Tree-based models have long been known as fundamental and successful class of machine learning algorithms. These models make predictions by applying a hierarchical, tree structure to the observations that is a unique take on solving problems whether they are classification (predicting categorical values) or regression (predicting numerical values). When it comes to prediction using tree-based methodologies, one basically generates a sequence of if-then rules from an initial root node (at the top) through a sequence of internal decision nodes and finalize in a terminal leaf node. To build this tree-like structure, a set of splitting rules are applied to divide the feature space into smaller groups until the stopping criteria is met. Stopping criteria is based on adjusting the hyperparameters which are non-learnable parameters (i.e. maximum depth of a tree, minimum samples in a node, etc.) that are defined prior to the commencement of the learning process. They serve to control various aspects of the learning algorithm and can significantly influence the model's performance and behavior. The careful tuning of these hyperparameters is paramount for achieving improved model performance and, critically, for mitigating the risk of overfitting.

Tree-based models are non-parametric supervised learning algorithms, known as being incredibly flexible for a variety of predictive tasks. These models' innate ability to capture complex patterns and non-linear interactions in complex datasets is a major advantage over conventional linear models. They are especially effective in real-world applications where relationships between variables are rarely purely linear, in contrast to linear models, which presume a direct, linear relationship between features and outcomes. This ability is useful to use when the mortality itself is considered a non-linear process.

In this study we used four popular types of tree-based algorithms which is believed to reflect the majority of the methods shows a tree structure and we can briefly classify them as [

39]:

Decision tree model, the substructure of tree-based models,

Random forest model, “ensemble” method constructs more than one decision tree,

Gradient boosting model, “ensemble” method constructs decision trees sequentially,

Extreme gradient boosting model, “ensemble” method constructs decision trees in parallel.

In this study, since the response variable is continuous, the tree-based methods are studied in a regression framework.

3.1. Decision Trees

Decision Trees (DT), first introduced by Brieman et al. [

40], serve as the foundational element for all tree-based models. Understanding their specific application in regression provides crucial context for the more complex ensemble methods.

To build a decision tree, an information must be defined for splitting the data. For discrete variables, popular choices would be the Gini information or entropy, however when the response variable is continuous, an error-based information is needed. Let S represents total squared errors of the tree T, [

41] showed that;

The splitting process is stopped by minimizing S with predefined hyperparameters, and the final predictions in each leaf are obtained.

3.2. Random Forest

In 2001, Breiman [

42] introduced a powerful tree-based algorithm called Random Forest (RF). In random forest, a bootstrap sample of the data, or n observations chosen with replacement from the initial n rows, is used to calculate each tree. This method is known as "bagging" which is derived from "bootstrap aggregating" [

43]. Predictions are found by pooling the predictions of all trees, means majority voting for classification problems and averaging of the predictions from all trees for regression problems.

The progression from single decision trees to ensemble methods like random forests is more than an incremental improvement in accuracy; it represents a fundamental shift in how the bias-variance trade-off is addressed. Single decision trees, by their nature, tend to be high-variance, low-bias models, meaning they can fit the training data very closely but are sensitive to small variations in that data, leading to poor generalization. Bagging, as implemented in random forests, primarily reduces variance by averaging the predictions of multiple independently trained trees, thereby mitigating the overfitting tendency of individual trees.

Final predictions are simply the averages of each prediction of the individual trees.

3.3. Gradient Boosting

Gradient Boosting (GB) algorithm makes accurate predictions with the combination of many decision trees in a single model. It is an algorithmic predictive modeling invented by Friedman [

44], that learns from errors to build up predictive strength. Unlike random forest, gradient boosting combines several weak models of prediction into a single ensemble to improve accuracy. Typically, gradient boosting uses decision trees, in an ensemble and are trained sequentially with the idea of minimizing errors [

45].

The algorithm fits a decision tree to the residuals of initial model. In this instance “fitting a tree based on the current residuals” means that we are fitting a tree, with the residuals as response values rather than the original outcome. This fitted tree now becomes a part of the fitted function and the residuals are updated. By doing so, f is being improved bit by bit in the regions in which is not performing good. The shrinkage parameter λ also slows down the process, leading to more and differently shaped trees applied to the residuals. In general, slow learners lead to a better overall performance [

46,

47].

Final predictions are shown as;

where

is learning rate, M represents total number of trees,

stands for m. regression tree output. Each

is trained on the residuals

that is shown as;

where L is the loss function aimed to minimize.

3.4. Extreme Gradient Boosting

Extreme gradient boosting (XGB) method developed by Chen and Guestrin [

48], is an improved implementation of GB basically with the same framework that combines weak learner trees into strong learning by adjusting the residuals. Unlike gradient boosting method, the trees grown in parallel, not sequentially. Also, extreme gradient boosting method has built-in regularization to prevent overfitting by penalizing model complexity.

Final predictions are estimated similarly but with a more regularized objective function [

49];

with trying to the minimize the function:

Here

is a differentiable loss function quantifies gap between estimated and response values where

[

49,

50]. In this formula w shows the score on the leaves, T; the number of leaves in a tree,

cost of adding a leaf and

; the regularization term on leaf weights.

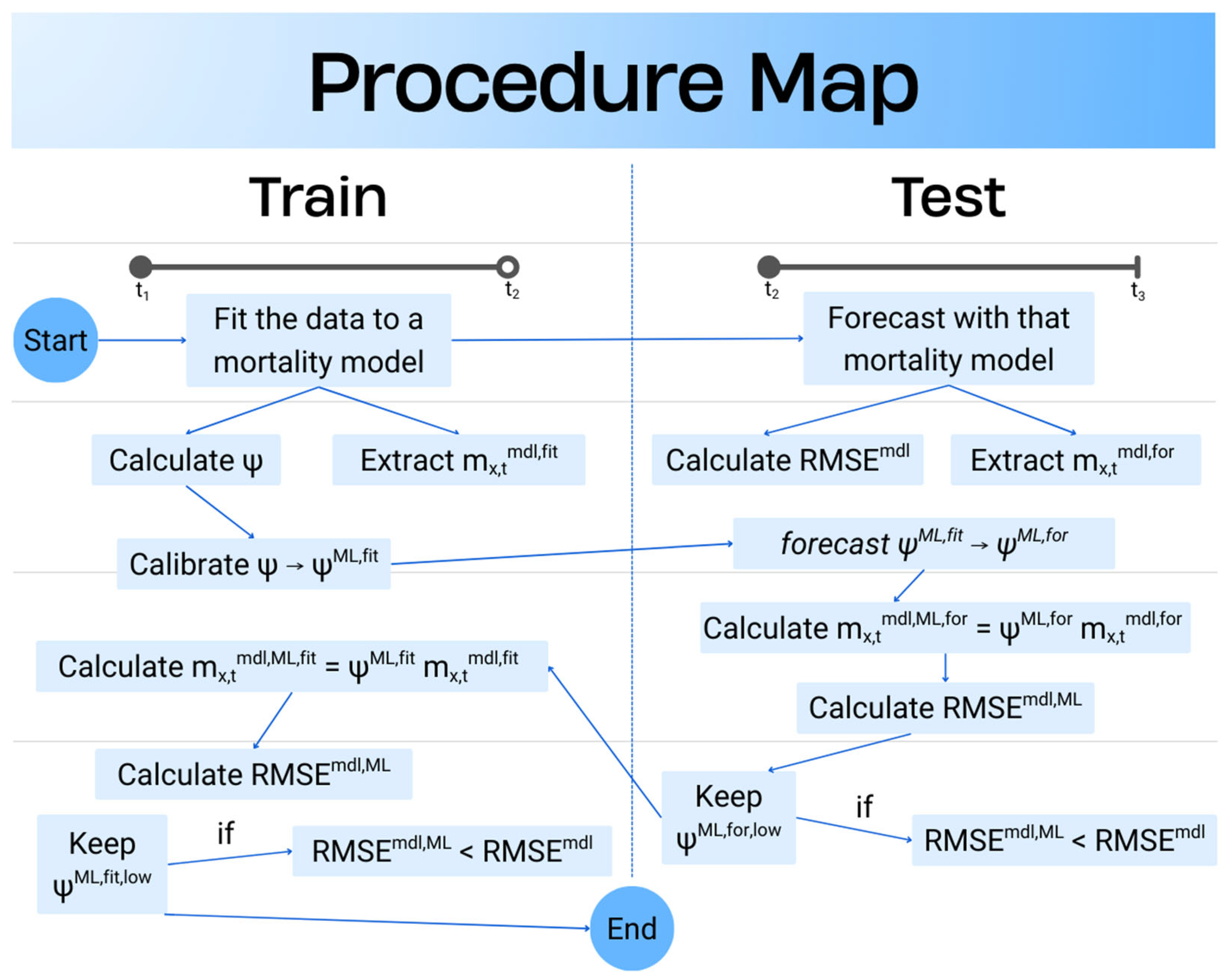

5. A Procedure for Improving the Forecasting Ability

The procedure means applying all methods sequentially to get the results without the need of human interaction. Briefly; after fitting a GAPC model to the data and obtain the mortality rates, is calculated. Then mortality model specific is estimated using tree-based model for both training and hold-out testing period with all possible set of hyperparameters. By multiplying the forecasted (estimated over the hold-out testing period) with which is the mortality rates forecasted using mortality model, machine learning integrated mortality rates () can easily be estimated. After that, for each hyperparameter set, the RMSE of ML integrated mortality rates against observed ones are calculated and lower than the RMSE of mortality models are chosen. For eliminating the randomness of the success of this process, the set of hyperparameters use to calibrate the and give the lower RMSE on the testing period, are checked if they give lower RMSE on the training period as well. Thus, a trade-off interval is created for lowering the error of original mortality model on both periods. The step-by-step explanation and the graphical representation are given below.

The Procedure

- 1.

Reserve a hold-out testing period,

- 2.

Fit a mortality model to the training data,

- 3.

Extract fitted mortality rates,

- 4.

Calculate for each age and year,

- 5.

Forecast with same mortality model over the testing period,

- 6.

Extract forecasted mortality rates and calculate model RMSE,

- 7.

Calibrate with tree-based methods;

- a.

Determine lower & upper limits of hyperparameters,

- b.

Extract re-estimated series calculated with different set of hyperparameters,

- 8.

Obtain each series using tree-based methods,

- 9.

Calculate each series of over the testing period,

- 10.

Identify the series that give less RMSE for testing period,

- 11.

Find series used to forecast and calculate over training period,

- 12.

Search for series that also give less RMSE for training period,

- 13.

Repeat the steps for each mortality model.

By following through the steps, series of improved mortality rates for both training and testing periods will be estimated. Under these circumstances, machine learning techniques can improve the mortality models’ forecasting accuracy without relying on the fixed fitting or testing period. At the end, researcher can make robust and reliable forecasts about future mortality.

The

Figure 3, represents the steps in a clear way, make the whole procedure more visible. Additionally, it is important to remember that these values are based on mortality rates either calculated by mortality models or those multiplied with the psi which is calibrated with tree-based models. Mortality rates themselves are not subject to any machine learning process. With the help of this flexible approach, researcher can adjust training and testing period of the preferred mortality model and make improved forecast of future mortality.

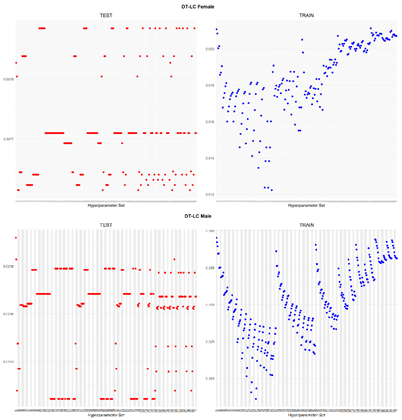

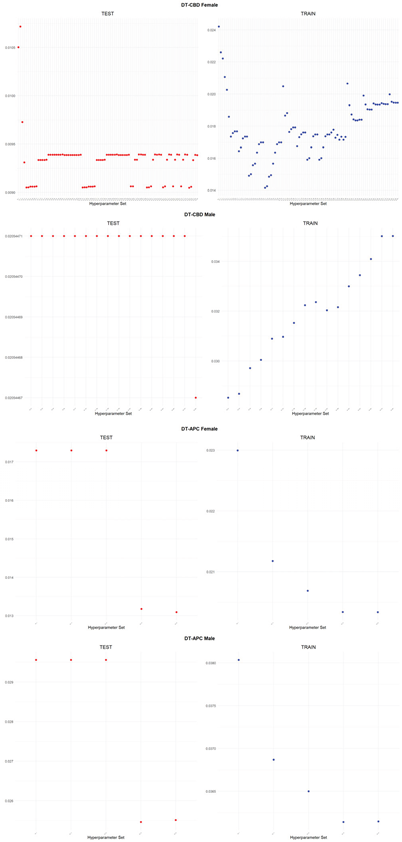

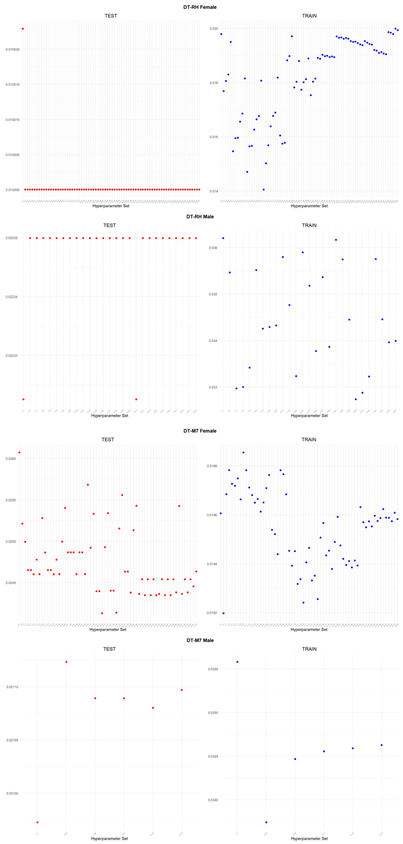

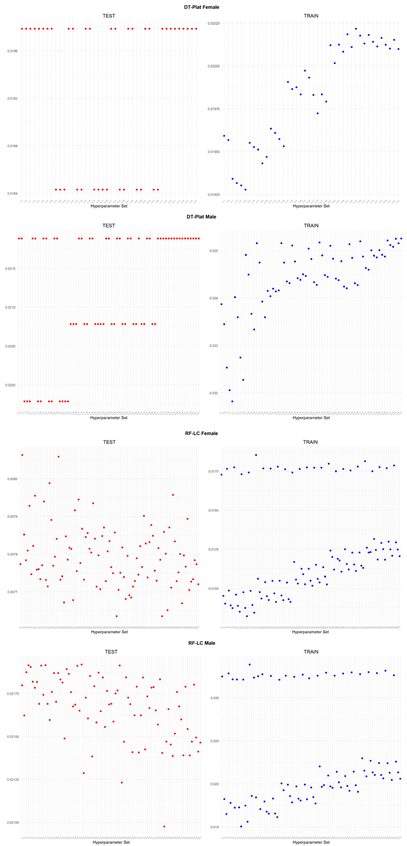

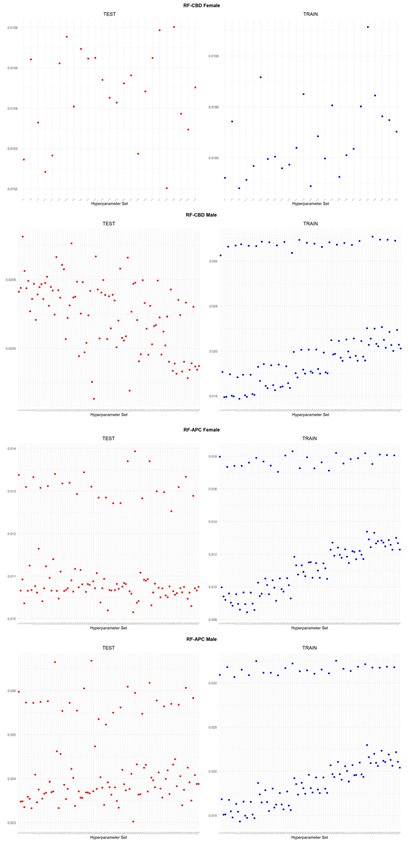

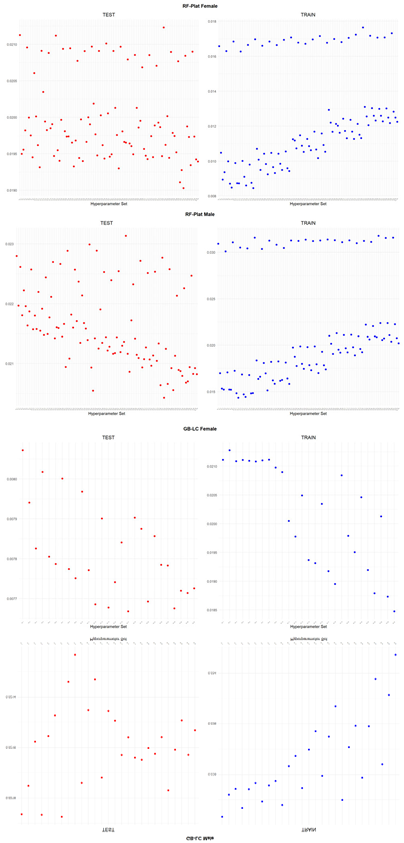

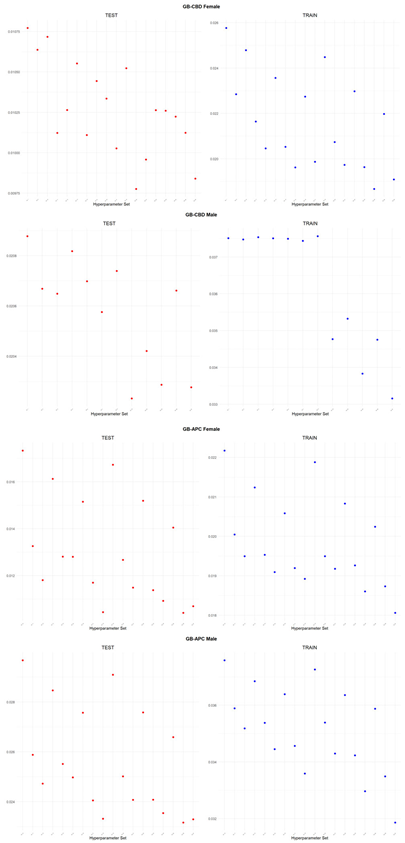

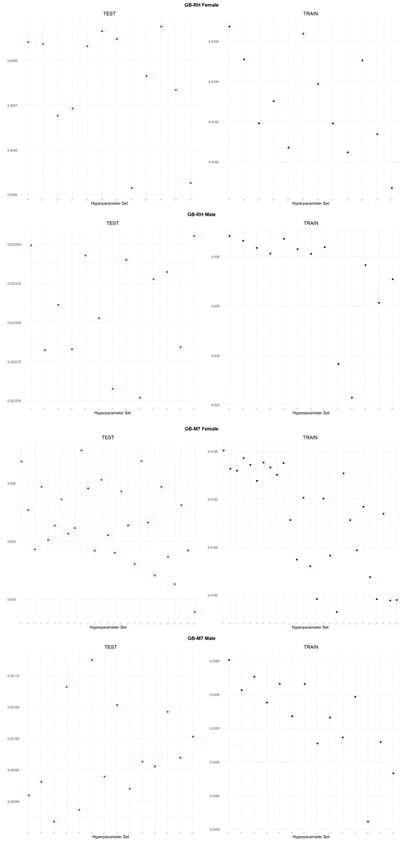

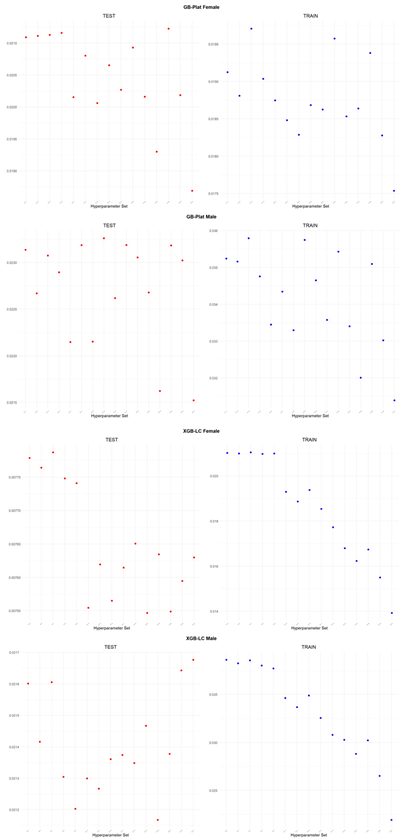

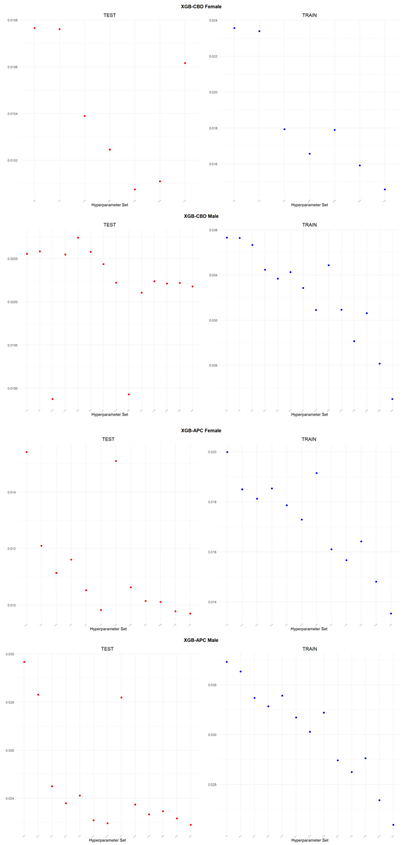

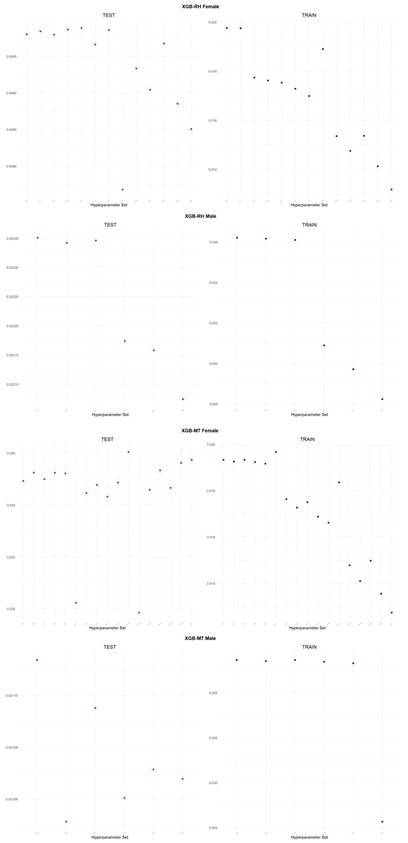

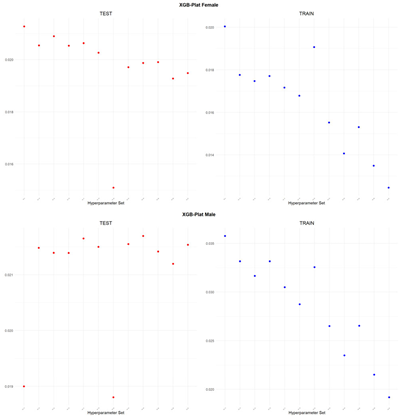

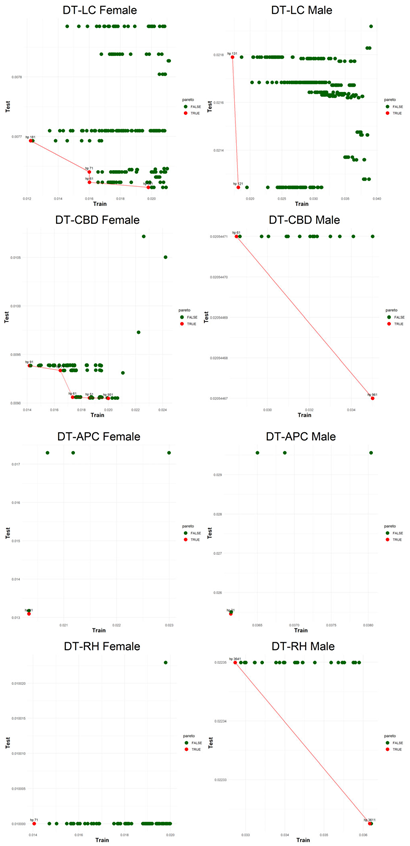

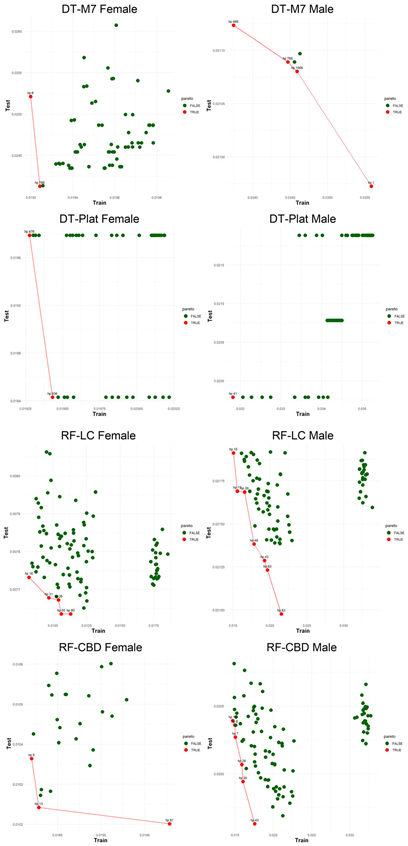

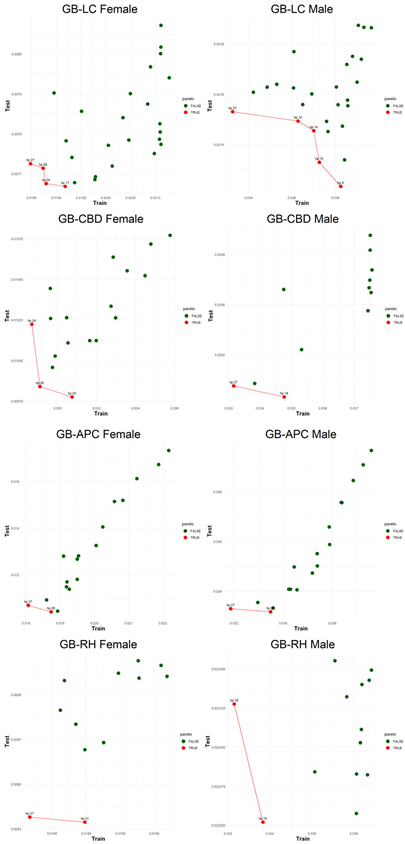

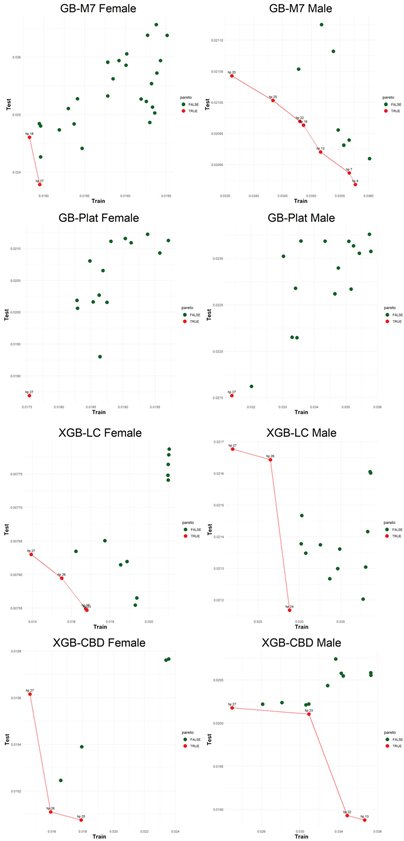

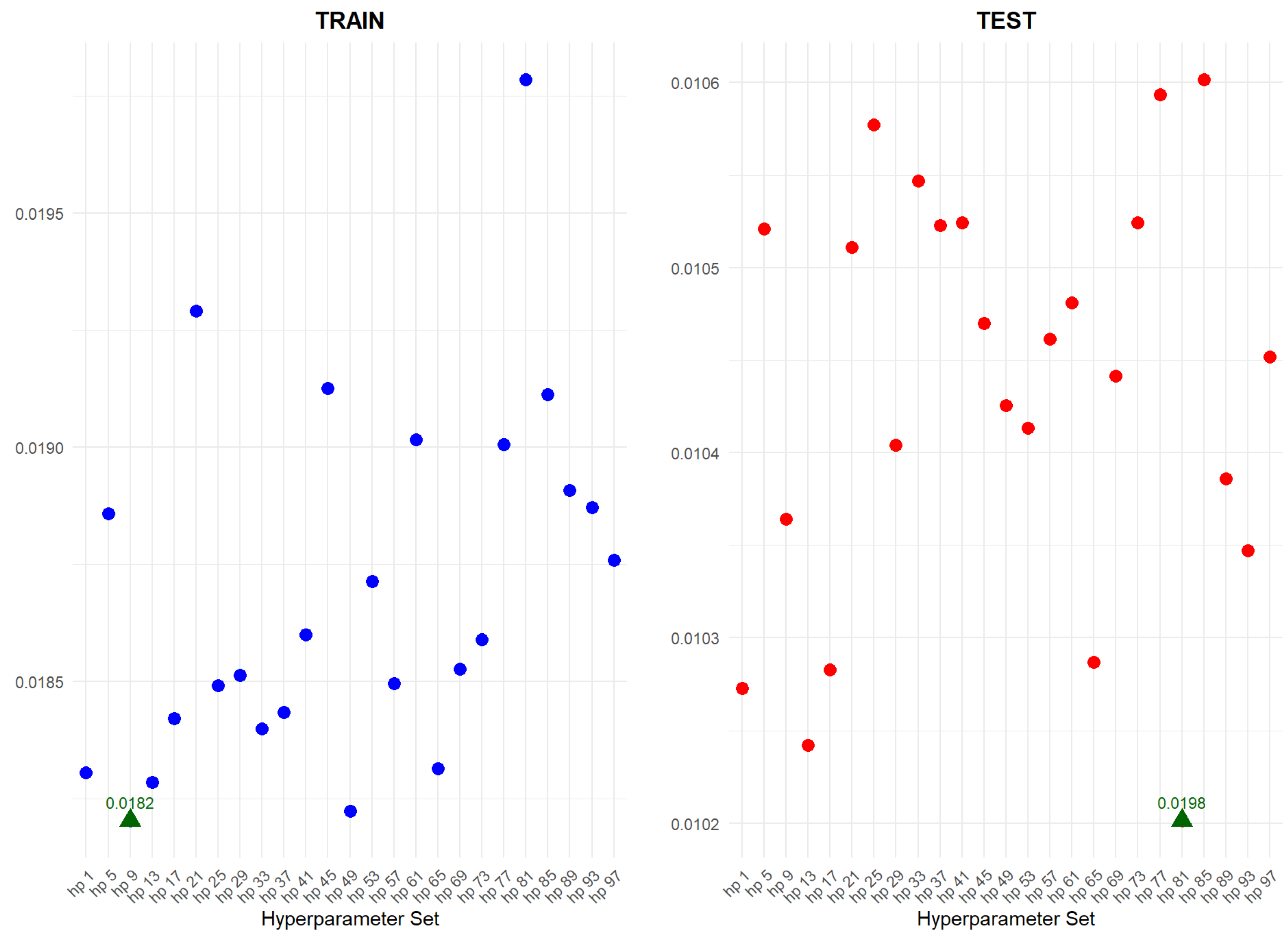

An application is performed for practical representation; the

Figure 4, shows only ML integrated model RMSEs by hyperparameter set that is less than pure mortality model’s RMSEs for both periods (figures of the other models are presented in the

Appendix A.1.). The procedure finds lower error for testing period first, then obtains the lower errors for training period using same hyperparameter sets against the pure mortality model. As can be seen from the

Figure 4, the hyperparameter set that gives the lowest error during the test period may not always be the hyperparameter set that gives the lowest error during the training period. In fact, it may even produce higher errors than the pure mortality model. Therefore, while focusing on achieving lowest error during the testing period, it is also necessary to find the set of hyperparameters that gives lower error than the pure mortality model over the training period.

Table 2, shows minimum values of RMSE over the testing and training period for pure mortality models and ML integrated models (male version of the table 2 is given in the

Appendix B.1.). The same data set used as for creating the

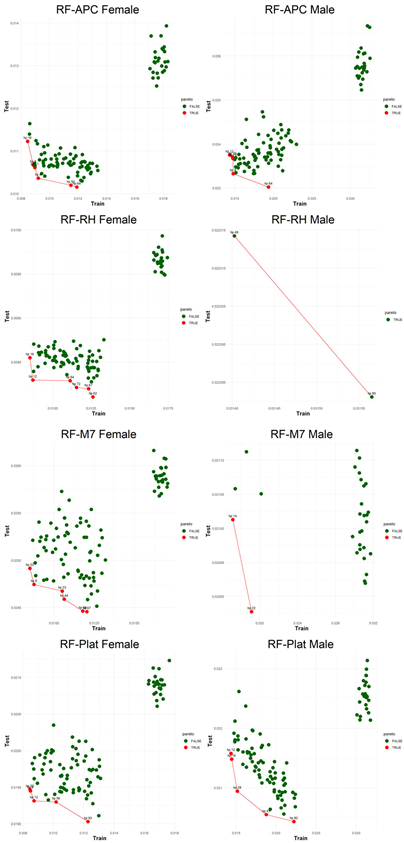

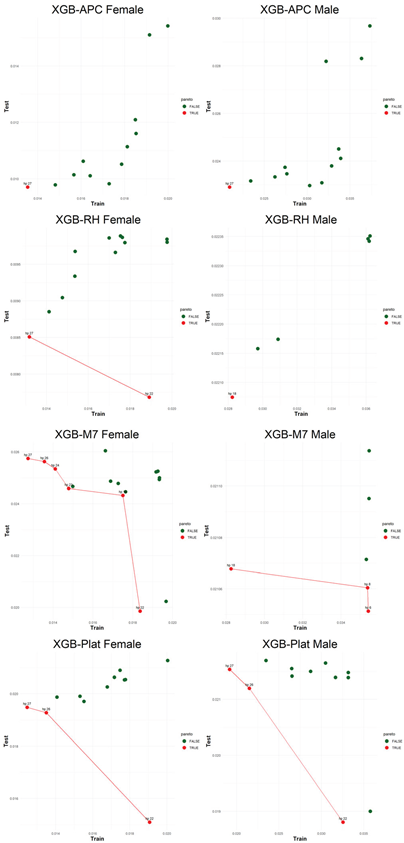

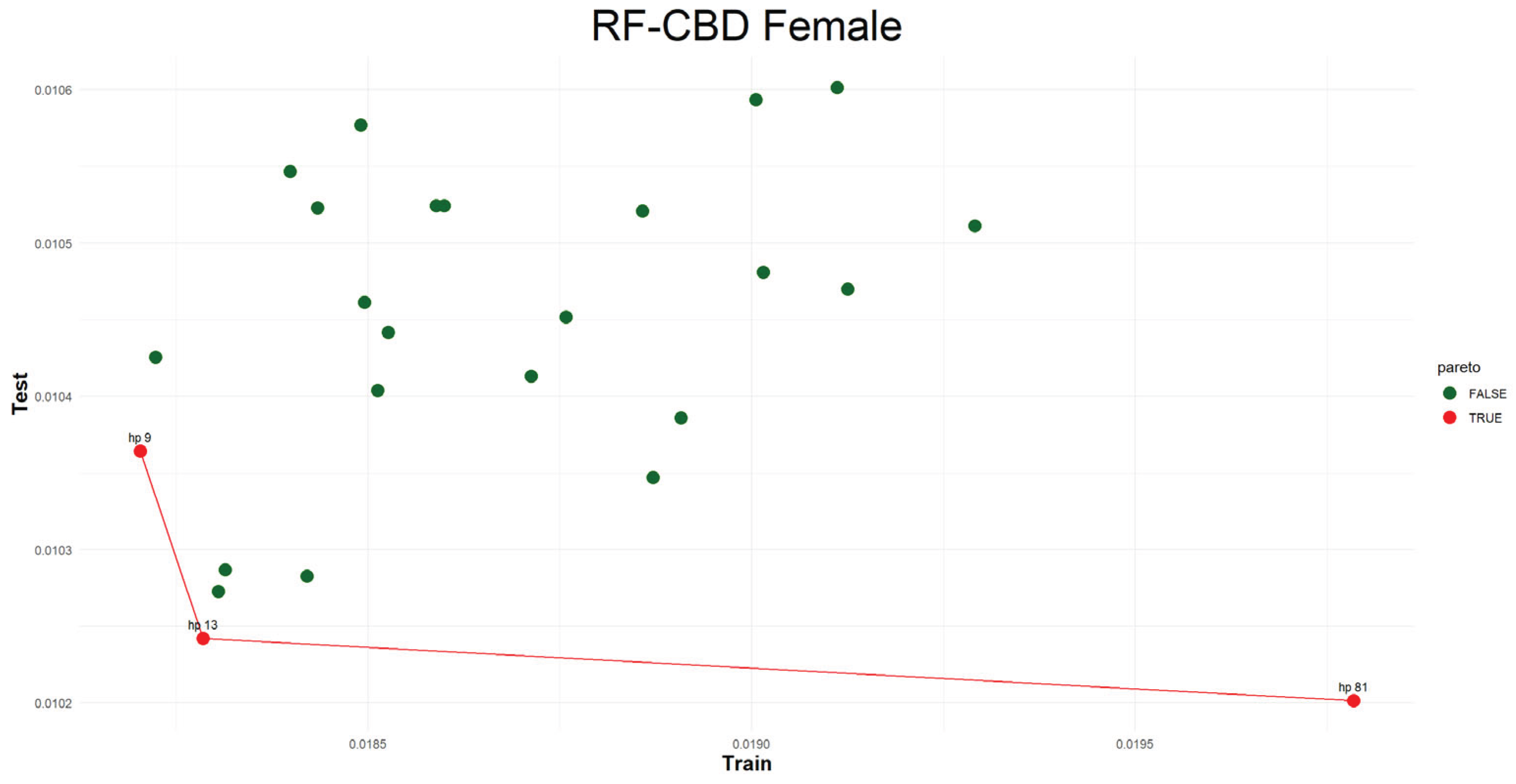

Figure 4. As it can seen from the table, including all ML integrated methods, using the same hyperparameter set that works best for testing period may produce higher error for the training period while different hyperparameter set give less error over the training period. At the same time, the error should not be higher than the pure mortality model’s error. Although, the users notice this trade-off mechanism, choosing the best combination still be confusing. Hence, we use Pareto [

51] optimal method to find the dominant combination of hyperparameter set.

In many instances it is said there are conflicting objective functions and that there exist Pareto optimal solutions. A susceptible solution is said to be nondominated if none of the objective functions can take on a new value to improve its value without deteriorating some of the other objective functions. These solutions are referred to as Pareto optimal. When no other preference information is supplied, all Pareto optimal solutions are said to be equally good [

52]

. In this regard, efficient frontier is constructed which shows the Pareto optimal values and connect them together.

Figure 5, visualizes the Pareto optimal values of the hyperparameter set that gives lower error over both training and testing periods (figures of the other models are presented in the

Appendix B.2.). The efficient frontier concept guides users in choosing the best balance of test and train errors.

6. Discussion

Mortality forecasting does not have a long history in the demographic or actuarial literature. Starting with Lee and Carter [

4], mortality forecasting has been gaining momentum, with comprehensive studies being conducted frequently. In recent years, researchers have focused their attention on integrating advanced statistical methods into their studies related to the length of human life. These studies show that when this growing interest is combined with demographic models, more robust and consistent results emerge.

Data for each population has its own unique characteristics. Mortality models aim to explain the mortality pattern and make accurate forecasts based on the historical data. In this context, machine learning can help understand the non-linear nature of the mortality rates, which generally tend to decline at almost every age each year. Declining pattern of mortality rates that results in increasing life expectancy pose a significant risk to the sustainability of social security, elderly care and pension systems which implies that we need more precise and robust forecasts of mortality.

This study presents a general procedure for improving the forecasting accuracy of mortality models using most common tree-based machine learning methods, by creating a flexible environment on the train/test data which is critical for measuring the goodness of fit/forecasting. This will enable researchers to choose the most suitable mortality model for population-specific mortality data and perform best practices of forecasts for the future mortality.

This study focuses on facilitating the integration of mortality models into machine learning methods within a general framework and to demonstrate that forecasting accuracy can be improved under specified conditions, rather than taking advantage of analyzing specific periods that increase forecasting accuracy. This study guides researchers in the right direction by offering a flexible structure while choosing the test data, which is one of the most important factors in measuring the quality of the model when using mortality models. We believe, researchers will enable to make more accurate forecasts for the future.