1. Introduction

Cattle are often supplemented with dietary protein because pasture or pasture-based roughages alone might not meet their dietary requirements. Protein is needed for the maintenance of body condition and production, but high levels of dietary protein lead to elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentrations, which have been associated with reduced reproductive performance in beef and dairy cattle [

1,

2,

3]. Low BUN concentrations are also detrimental to reproductive performance as they indicate protein deficiency [

4].

Although the mechanism by which elevated BUN concentration negatively affects reproductive performance is not fully understood, elevated BUN concentration is associated with an altered composition of uterine fluids [

5] and has detrimental effects on the oocyte or embryo before it reaches the uterus [

2].

In-vitro studies have demonstrated that high urea nitrogen concentration in the maturation medium disrupts oocyte maturation and fertilisation [

6,

7]. High levels of ammonia (associated with high BUN concentrations) can be toxic to oocytes, spermatocytes, and early embryos [

8,

9]. Elevated blood or milk urea nitrogen concentration before breeding has been associated with longer days to pregnancy in beef [

3] and dairy cattle [

1].

Although these studies attempted to establish the developmental stage at which the oocytes and zygotes are vulnerable to the negative effects of extreme BUN concentrations, the specific period of vulnerability remains unknown. It can be anything from the initial stages of oocyte development to the early stages of embryonal development. The present study investigated whether in vivo exposure of oocytes (before ovulation) to extreme BUN concentrations influences their progression to the blastocyst stage in vitro.

The cattle used in this study were the same as the ones from our previous reports [

10,

11].

Non-pregnant, non-lactating Nguni (n = 12) and Hereford (n = 10) cows from private cow-calf enterprises were obtained for this study. All cows were housed at the Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, for the duration of the study. Cows were between 2 and 16 years of age and were housed in four pens according to breed and dietary treatment. At arrival, the reproductive tracts of all cows were examined ultrasonographically (Mindray, micro convex 5MHz transducer, Taiwan) to determine pregnancy status, ovarian function and antral follicle count (AFC) [

12]. Ovaries with corpora lutea or a follicle with a diameter of at least 13mm were defined as being active [

13]. Cows with inactive ovaries were excluded from the study.

Cows were assigned to two isocaloric dietary treatment groups (

Table 1) using stratified randomization by breed and AFC. All diets were formulated using the same feed ingredients at different inclusion levels. A high (14%) protein diet (HCP) was produced by adding 20kg of feed-grade urea (KK Animal Nutrition, South Africa) to a ton of the normal (7.9%) crude protein (NCP) diet, while the low (4.4%) crude protein (LCP) diet was produced by reducing the inclusion rates of urea and other protein sources in the diet. During the first phase of the experiment, the first group of cows was fed the NCP diet while the other group was fed the HCP diet. A cross-over design was utilized during the first phase, where diets were switched after six weeks, and the cows remained on the new diets for another six weeks. At the end of this phase, cows had a one-week washout period wherein they were fed the NCP diet. After the washout period, cows were randomized again into two new groups for the second phase of the experiment, using a similar randomization process. The new groups were fed either the NCP or LCP diet for four weeks, after which the cows were put on natural pasture for an additional three weeks. After three weeks, diets were switched again like the first phase, and the groups remained on the new diets for another four weeks.

Feed-grade urea content was increased over four weeks (weekly increments of 5kg of feed-grade urea per ton of feed) to adapt cows to the HCP diet. Cows were allowed to acclimatize to each new diet for at least two weeks before sampling was performed. All groups were fed twice daily, at 07h00 and 16h00, throughout the study. Feed delivery was kept constant at 2.5% dry matter per kg body weight daily with minor adjustments based on the amount of left-over feed. Cows of the same breed were housed together, but separate pens were used for each diet treatment group (four independent pens).

Blood sampling and analysis

Once acclimatization to new diets was completed, blood sampling was performed twice weekly, on Mondays and Wednesdays, for 22 total collections. Animals were restrained in a chute for all sampling procedures on each sampling day. Sampling started two hours after the delivery of the morning feed. Blood was drawn from the coccygeal vein into evacuated 4-ml serum tubes (Becton Dickinson; BD vacutainer CAT, silicone clot activator). Tubes were centrifuged at 3000 x g for 10 minutes to obtain serum, which was frozen at -80 °C within 2 hours of collection. Serum samples were analysed for BUN concentration using an auto-analyser machine (Cobas Integra 400 plus; Roche, Switzerland) within 30 days of sampling.

Follicular aspiration and processing

Oocyte and follicular fluid collection were performed via ultrasound-guided aspiration immediately after blood sampling. Epidural anaesthesia was performed by administering 5 ml of 2% lignocaine hydrochloride according to a standardized protocol [

14] before aspiration. An aspiration probe (Watanabe Technologia Applicada, Brazil) with a 7.5 MHz transducer and needle guidance system, a 19-gauge 38.1mm long hypodermic needle and a vacuum pressure of 80mmHg was used for aspiration. Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (Onderstepoort Biological Products, South Africa), supplemented with 5% foetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, South Africa) and maintained at 38 °C, was used as the flushing medium.

The probe was introduced deep into the vagina while the ovary was immobilized per rectum. The ultrasound image aided in guiding the needle towards the follicles. All follicles with a diameter of 3mm or greater were aspirated. Searching for cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) was completed within 30 minutes of aspiration.

Recovered oocytes were graded into usable and non-usable (degenerate) oocytes [

15]. In both phases of the study, oocytes from each sampling day were pooled into 4 groups based on breed and diet. All degenerate oocytes were discarded. The weighted mean BUN concentration for each pool was determined based on the proportion of oocytes in the pool contributed by each cow. The COCs were washed twice in Hepes-buffered solution (Sigma-Aldrich, South Africa) before being transferred into maturation media, prepared according to the Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria

in vitro fertilization (IVF) protocol [

16]. The COCs were matured for 24 hours in a 5% CO

2 incubator at 38.5 °C. Mechanical denudation of oocytes was performed by gentle pipetting before fertilization.

Frozen semen straws derived from a single proven

in-vitro fertilization bull were thawed by immersion in 37 °C water for one minute. Semen was purified by transferring straw contents onto a BoviPure® gradient (Nidacon Laboratories AB, Göthenburg, Sweden) and centrifuging at 300 x g for 20 minutes. The subsequent pellet was suspended in the purification medium and centrifuged again at 300 x g for an additional 10 minutes. The resultant pellet was then resuspended, and 10μl of the suspension (concentration = 1 x 10

6 spermatozoa/ml) was transferred to 40μl droplets of mineral oil containing pooled matured oocytes and incubated in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere for 18-20 hours at 38.5 °C. After insemination, zygotes were denuded of sperm droplets and the remaining cumulus by vortexing. This was followed by washing with early synthetic oviduct fluid (ESOF) and culturing for 4 days, after which the ESOF was replaced with late synthetic oviduct fluid (LSOF). Embryos were graded on days 2, 4, 7 and 8 according to the International Embryo Transfer Society [

17], and developmental stages were recorded.

Statistical analyses

BUN concentration data were categorised as normal or extreme concentrations. The normal category was defined as BUN concentration data between 7mg/dL and 20mg/dL [

4,

18], while the extreme category consisted of BUN concentrations outside this range.

The chi-squared test was used to compare the proportion of oocytes recovered per each follicle aspirated, and to compare proportions of various grades of oocytes recovered, per category (normal vs. extreme BUN). A Mann-Whitney U test was performed to investigate whether the distribution of oocyte grades was similar between oocytes obtained from cows with normal and extreme BUN concentrations. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to assess the effects of in vivo exposure to extreme BUN concentrations on oocyte development in vitro. The outcome variable was whether oocyte development became arrested. The time variable for the analysis was the stage of development (i.e., maturation, IVF, cleavage, morula stage, early blastocyst stage and the blastocyst stage). Dietary treatment was included as a stratifying factor to adjust for the pooling of oocytes and subsequent statistical dependence. A second model (Model 2), which incorporated an interaction term between Breed and BUN concentration, was created to assess if Breed and BUN concentration acted independently. Breed was forced into all models because it was an exposure variable of interest.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24 (International Business Machines Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MINITAB Statistical Software, Release 13.32 (Minitab Inc., State College, Pennsylvania, USA). Statistical significance was established as P < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 1601 oocytes were recovered, of which 76% (1209/1601) were usable (grade 1 to 4) and transferred to the maturation media (

Table 2).

There was no difference in the proportion of oocytes recovered per each follicle aspirated (number of oocytes recovered ÷ number of follicles aspirated), between cows with normal and those with extreme BUN concentrations (0.37 and 0.36, respectively, P = 0.196). Distributions of oocytes per each oocyte grade category (Grade 1 – 4 and degenerate) were not different between oocytes obtained from cows with normal and those with extreme BUN concentrations (P = 0.237).

The rate of failure to develop to the blastocyst stage was 1.18 times higher (

P = 0.020) in oocytes from cows with (weighted average) extreme BUN concentrations compared with those from cows with (weighted average) normal BUN concentrations (Model 1;

Table 3). Oocytes from Hereford cows with extreme BUN concentration had a 1.32 times higher (

P = 0.006) rate of failure (Model 2;

Table 3) whilst those from Nguni cows with extreme BUN concentration only had a 1.05 times higher rate of failure (obtained by adding the

values for BUN concentration and the interaction term from Model 2) but this breed effect was not statistically significant (

P = 0.125).

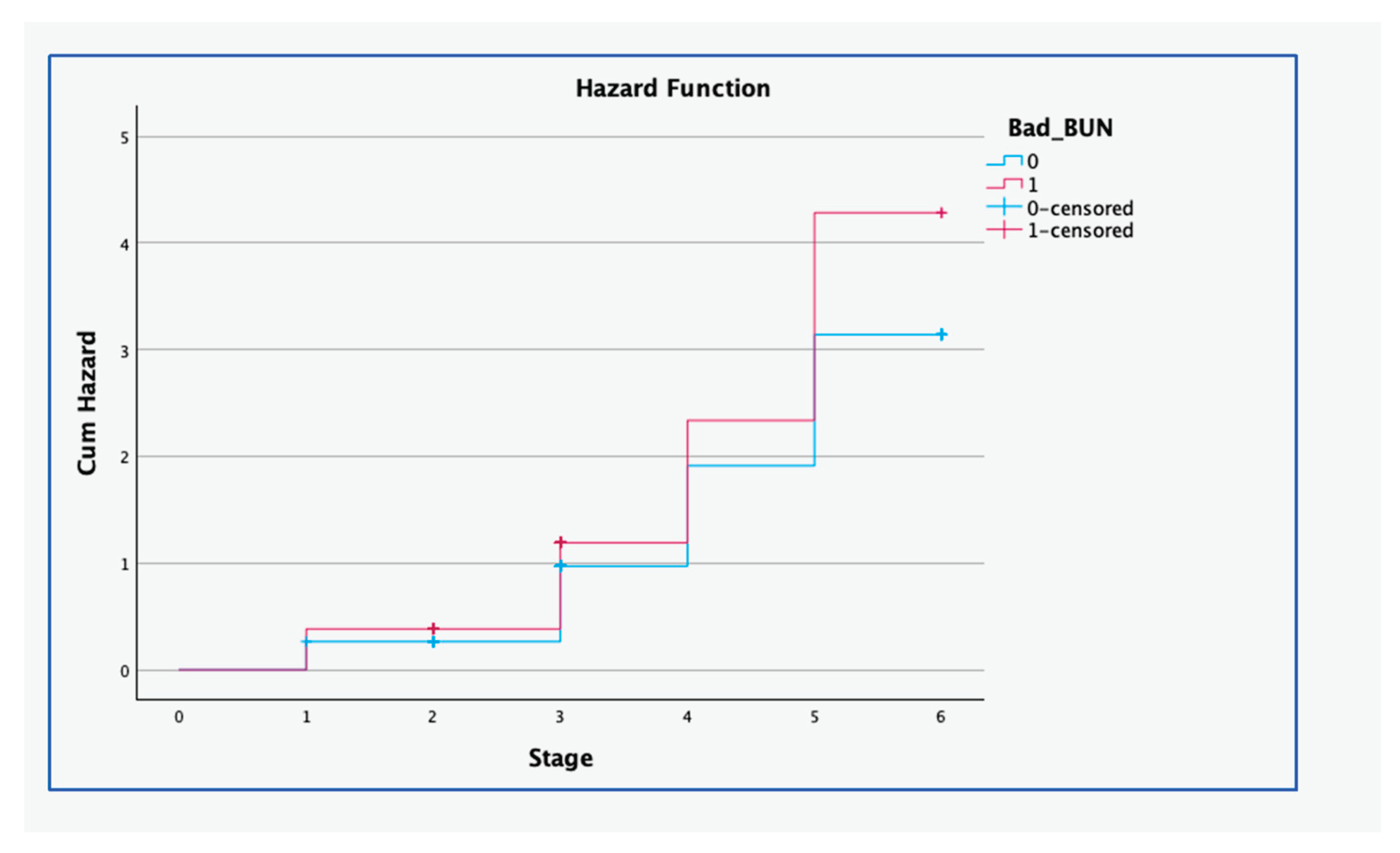

The hazard for arrested development remained low for both cohorts until the cleavage stage (

Figure 1), whereafter it increased more for oocytes harvested from cows with extreme BUN when compared to those harvested from cows with normal BUN concentration (

P < 0.001).

Extreme BUN – Blood urea nitrogen concentration in this range (7mg/dL > BUN > 20mg/dL); Normal BUN - Blood urea nitrogen concentration in this range (7mg/dL < BUN < 20mg/dL [

4,

18]); Embryonal development stages 1 = maturation; 2 =

in vitro fertilisation; 3 = cleavage; 4 = morula stage; 5 = early blastocyst stage

4. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of in vivo exposure of oocytes to extreme (high or low) BUN concentrations on the subsequent survival of IVF-derived embryos, noting that antral follicle count in cattle is a repeatable measure strongly correlated with the number of healthy ovarian follicles [

19,

20]. BUN concentration also did not affect the grade of oocyte harvested, seeing that the proportions of oocytes recovered in each grade were not different between the two groups, which is consistent with previous studies [

9,

19,

20]. Previous exposure to extreme BUN concentrations in this study did not affect oocyte recovery from follicles during OPU.Oocytes recovered from cows with extreme BUN concentrations were more likely to fail to progress to the blastocyst stage by Day 8, despite being morphologically similar to those recovered from cows with normal BUN concentrations. To the knowledge of the authors, the effect of prior exposure of COCs to extreme BUN concentrations has not been previously quantified.

Previous studies estimated the negative effect of high concentrations of urea or ammonia on reproductive performance [

5,

21,

22]. This suggests that the developmental environment of the oocyte/embryo is important in determining its competence. More recent studies [

23,

24,

25], including the current one, suggest that it is not only the developmental environment that determines oocyte survival but also previous exposure to extreme BUN concentrations. Our experimental design enabled us to provide the same conditions for all the oocytes

in vitro, which was important for ensuring that the observed effects were purely due to previous exposure to extreme BUN concentration and not the current environment of the oocyte and embryo during development. This agrees with our previous study [

3], which found that BUN concentration measured one week before the onset of the breeding season was associated with the number of days to pregnancy but not the pregnancy status of beef heifers. This finding suggested that previous exposure of developing oocytes to high BUN concentrations continued to influence oocytes after fertilisation. It has been shown

in vitro that urea reduces oocyte competence by changing gene expression in resultant embryos, which is associated with an upregulation of the turnover of certain amino acids, resulting in amino acid imbalances [

23,

25].

Negative effects of previous exposure to extreme BUN concentrations were observed mainly at the cleavage, morula and early blastocyst stages, which is consistent with previous studies [

24].

Bovine antral follicles require approximately 40 days to become mature Graafian follicles [

26,

27]. Therefore, oocytes that were aspirated in this study were somewhere in their final 40 days of maturation. Although the exact age of the follicles was not known, it is possible that exposure to extreme BUN concentration

in vivo, up to 40 days before the onset of breeding, could still have detrimental effects on the competence of oocytes. This is an important finding to consider in the nutritional management of cattle production systems. The reason is that an isolated period of extreme BUN concentration as a result of a ration mixing error could affect oocyte viability far beyond the time that such an effect is measurable in the animals. This might explain observations reported previously where heifers with relatively high BUN concentration within a herd exposed to a high crude protein diet, were at risk of reproductive failure for up to 3 months after the event (Tshuma et al., 2014). This has even further implications when we consider other factors (other than diet composition) that have been demonstrated to affect BUN concentration in cows. Some of these factors are not easy to control through improved management. Heat stress for example, has been shown to independently result in a significant increase in MUN concentration [

28], which now means that a period of heat stress as a result of extreme temperature or humidity over a short period could in fact affect the fertility of cows for several weeks thereafter, due to the lingering negative effect of BUN on oocyte competence. It could be hypothesised that this effect might at least be partially responsible for seasonal differences in the reproductive performance of dairy cows [

29].

The effects of donor cow age on the survival of embryos could not be accounted for in this model. However, the authors believe that breed might incorporate the effect of age because very old cows belonged to one breed (Nguni) in this study.

Although not statistically significant, adding the interaction term between breed and BUN concentration category seems to suggest that BUN concentration did not influence the survival of oocytes from Nguni cows. This might explain, in part, the previous observation that Nguni cows maintained good fertility during periods of restricted protein availability [

28,

29]. In our previous study, we concluded that Nguni cows receiving high-protein diets managed to prevent their BUN concentration from reaching threshold levels that impact oocyte quality [

10], but the current study demonstrates that the oocytes themselves might also have some inherent resilience to the effects of extreme BUN concentration. However, we suggest that this hypothesis should receive more research attention.

Results obtained in vitro have their limitations when predicting what would happen in vivo. Oocytes in this study were selected based on their morphological appearance, which is not the case in vivo. This selection might have introduced some bias, and hence, the study might only partially explain the effects of previous exposure to extreme BUN concentrations. Other possible limitations of this study include the limited sample size and limited breed distribution (especially considering that breed effects might exist), the lack of individual data at the oocyte level due to pooling during the IVF procedures, and the extreme diets that cows in this experiment consumed, that might not represent reality in a commercial farming system.

Despite having localized the period during which the negative effects of urea are exerted to the period before ovulation, it is possible that urea can also affect the fertility of cattle at other periods, as suggested by other studies [

30,

31].

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, D.H. and T.T.; methodology, D.H., M.S., G.F. and T.T.; validation, D.H., G.F. and M.S.; formal analysis, G.F., D.H., M.S. and T.T.; investigation, T.T.; data collection, T.T., D.H, and R.H.; data curation, G.F. and T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, T.T., D.H., G.F., R.H. and M.S.; visualization, T.T.; supervision, D.H. and G.F.; project administration, D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”