1. Introduction

The United States sheep industry spans a broad geographical range with vast production systems from coast to coast. The industry has an estimated 1.4 billion dollars in total economic output [

1]. Despite the variation across the country, most death losses in the industry occur within the first week of life. Furthermore, seventy-nine percent of those losses occur within the first four days following birth, with starvation and respiratory disease being the leading contributors [

2]. Both can be reduced if lambs receive adequate amounts of colostrum [

3]. Colostrum is the first milk produced by the dam following parturition. In sheep, colostrum provides lambs with essential nutritional components, including fats and proteins, as well as immunological components of immunoglobulins, cytokines, hormones, and maternal leukocytes [

4,

5,

6]. The transfer of maternal immune components is known as passive transfer. Passive transfer of immunoglobulins, particularly immunoglobulin G (IgG), provides the lamb with immune protection during the early stages of life. In calves, passive transfer of cytokines and maternal leukocytes also promotes the development of the neonate’s immune system [

7,

8]. Given the importance of colostrum, when a ewe gives birth and does not produce enough colostrum, producers often substitute with one of four sources: fresh colostrum from another ewe, frozen ewe colostrum, cattle colostrum, or an artificial colostrum source [

9]. Despite the use of these colostrum substitutes within the industry, little scientific data is published on how they affect passive immune protection or their ability to promote the development of the lamb’s immune system. This study was conducted to assess each of these sources’ effects on passive immune protection and the development of the immune system of the lamb. We hypothesized that lambs receiving fresh colostrum would have greater total and relative IgG concentrations, as well as show slower IgG decay than other colostrum sources. Furthermore, we hypothesized that fresh ewe colostrum would promote a faster development of the neonatal adaptive immune response, resulting in a faster and greater antibody response to ovalbumin.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Handling and Sample Collection

Forty-three Polypay lambs born as twins or triplets were used for this study. Immediately after birth, lambs were dried with towels and umbilical cords were trimmed and dipped with a 7% iodine solution. Lambs were weighed; blood was collected via jugular venipuncture and fecal samples were collected. Lambs were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups: Fresh ewe colostrum (FrC), Frozen ewe colostrum (FZ), Frozen bovine colostrum (CC), and Artificial bovine colostrum (AC). Fresh colostrum was sourced from the dam immediately before feeding the lamb. Frozen ewe colostrum sourced from the South Dakota State University (SDSU) sheep unit and other flocks within the Midwest was collected for 1-3 months before the start of the experiment, then pooled and stored at -20 °C (150mL aliquots). Frozen bovine colostrum was sourced from a dairy farm (Mills Dairy Farm LLC, Hayesville, OH) and stored at -20°C (150 ml aliquots). Powdered artificial colostrum containing freeze-dried bovine IgG (Shepherd’s Choice Premium Colostrum Replacer, Washington, IA) was used for the AC group. Once assigned to a treatment group, lambs were fed 65mL of colostrum per kilogram of birth weight via an esophageal tube within the first 4 hours of life; the maximum amount of colostrum given in one feeding did not exceed 177mL. Lambs were then given a second feeding 90-120 minutes following the first feeding. Thereafter, lambs were housed in a group pen where they had access to ad libitum warm milk replacer (The Shepherd’s Choice Lamb and Kid Instant Milk Replacer, Washington, IA). Lamb weight, blood and fecal samples were collected 24 h post colostral ingestion and then at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days of age (D). Blood samples were allowed to rest for one hour, then were centrifuged (3010×g for 20 min), serum was collected and stored at −20 °C until further analyses. Fecal samples were frozen (−20 °C) and stored until further analyses. At 7 D, lambs were docked and male lambs castrated using an elastrator and a band. Additionally, starting at 7 D, lambs were offered access to ad libitum creep feed (18% Crude Protein) and warm milk replacer. At 14 D, lambs were transitioned to ad libitum cold milk (1-4°C), creep feed, and alfalfa hay. These same conditions were kept until 28 D. At 28 D, lambs were weaned from milk replacer and offered ad libitum creep feed, and alfalfa hay. Ad libitum sodium bicarbonate was also offered at this time to reduce the risk of ruminal acidosis. At five weeks of age, lambs (35 D) received bilateral subcutaneous cervical injections of 1mL ovalbumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; 2mg/mL in PBS) homogenized with 1mL of Freund’s Incomplete Adjuvant (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Blood samples were collected pre-immunization and weekly for 4 weeks post-immunization. Four weeks after the first immunization (63 D), lambs received a booster injection of 1mL ovalbumin (2mg/mL in PBS) homogenized with 1mL of Freund’s Incomplete Adjuvant. Blood samples were collected weekly for 4 weeks following the second immunization. Weights were measured at weaning and 90 D.

2.2. IgG Detection

Serum and colostrum IgG concentrations were measured using Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Radial Immunodiffusion (RID). Serum and colostrum samples from all treatment groups were analyzed following the protocol described by the Ovine IgG ELISA kit (ALPCO, Salem, NH). Ovine IgG concentrations of each sample were determined from optical densities using a set of known standards and a 5-parameter logistic curve. A cross-reactivity check was performed with the Ovine IgG ELISA to assess for cross-detection of bovine IgG. Samples from the treatment groups receiving cattle colostrum and artificial colostrum were also analyzed following the protocol described by the Bovine IgG ELISA kit (ZeptoMetrix, Buffalo, NY). Bovine IgG concentrations of each sample were determined using a set of known standards and a 5-parameter logistic curve. A cross-reactivity check was performed on the Bovine IgG ELISA to assess for the detection of Ovine IgG. Radial immunodiffusion plates (JJJ Diagnostics, Bellingham, WA) were used to quantify both ovine and bovine IgG levels. Colostrum and serum samples from all treatment groups were analyzed using the protocol described by the Ovine IgG RID plates kit (JJJ Diagnostics, Bellingham, WA). Ovine IgG concentration of the unknown samples was determined using the diffusion radius of three known concentrations to create a linear regression equation. Colostrum and serum samples from the treatment groups receiving cattle and artificial colostrum were analyzed using the protocol described in the Bovine IgG RID plates kit (JJJ Diagnostics, Bellingham, WA). Bovine IgG concentration of the unknown samples was determined using the diffusion radius of three known standard concentrations to create a linear regression equation.

2.3. Anti-Ovalbumin Antibody Detection

Anti-ovalbumin antibody level detection was performed using an indirect ELISA developed in the Veterinary and Biomedical Science department of SDSU. The ELISA was performed using an Immulon 1B 96-well plate (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Antigen coating was performed by adding 100 uL of ovalbumin (OVA; 1mg: 400 mL Antigen Coating Buffer [pH 9.6]), into the wells of odd-numbered columns. Even-numbered columns had 100 uL of Antigen Coating Buffer (pH 9.6) added, to serve as the negative control. Plates were then incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. Plates were then washed four times with 1X phosphate-buffered saline + 0.01% Tween 20 (PBST; Avantor, Radnor, PA). After washing, 200 uL of 5% non-fat dry milk (Shurfine Nonfat Dry Milk, Shurfine Food, Burwell, NE) was diluted in PBST, also referred to as blocking antibody diluent (BAD), and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Plates were then rewashed with PBST four times. Serum samples were diluted 1:100 in BAD, and 100 μL of each diluted sample was loaded in duplicate (1 and 1) into the odd-numbered column and the even-numbered control column. A known positive serum reference sample was created by pooling known positive serum samples. The known positive reference sample was diluted 1:100 in BAD and added to columns 1 and 2 of each plate. Plates were incubated for 1 hour at 20°C, then washed four times with PBST. Donkey anti-sheep horseradish peroxidase conjugated antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) was diluted 1:20,000 in 1X PBS, then 100 uL was added to each well. Plates were incubated for 1 hour at 20°C, then washed four times with PBST. Next, 100 uL of 3,3’,5,5’-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB; Avantor, Radnor, PA) was added as the working substrate to each well. The reaction continued until one of the wells reached an optical density of approximately 2.0. The reaction was then stopped by adding 100 uL of 2N H2SO4 to each of the wells. Optical densities (OD) were then measured using a plate reader set at 450nm. Optical density values of the control cells were subtracted from the ODs of the coated cell (OD odd cell – OD of even cell) to normalize the data and control for background noise. Sample to Positive ratios (S/P) were calculated by dividing the OD of the sample by the OD of the known positive and multiplying by an arbitrary value of 3 ([OD of Sample / OD of Known Positive] × 3).

2.4. Microbial DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification of the 16S rRNA Gene

A bead beating plus column method, which included the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), was used to extract microbial genomic DNA from individual fecal samples (n=18) as previously described [

10]. The universal forward 27F-5'AGAGTTTGATCMTGCTCAG [

11] and reverse 519R-5'GWATTACCGCGCGCGCTG [

12] primers were used to target the V1-V3 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene by PCR to generate amplicons for DNA sequencing. PCR and Next Generation Sequencing (Illumina MiSeq 2X300 platform) services were performed by Molecular Research Laboratory (‘MRDNA’, Shallowater, TX, USA).

2.5. Bacterial Composition Analyses

Sequence data were analyzed using a combination of custom-written Perl scripts and publicly available software as previously described [

13]. Sequences were merged from overlapping paired end reads using the ‘make.contigs’ command from the MOTHUR (v.1.44.1) open-source software package [

14]; these contigs corresponded to V1-V3 amplicons generated from the 16S rRNA bacterial gene. Contig sequences for the V1-V3 region were first screened to meet the following criteria: presence of both intact 27F and 519R primer sequences, a minimal average Phred quality score of Q33, and length between 400 and 580 nt. After quality screening, V1-V3 sequences were aligned, then clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) using a sequence dissimilarity cutoff of 4%. This threshold is more suitable for the V1-V3 region than the 3% cutoff that is typically used indiscriminately for clustering of 16S rRNA sequence data, regardless of the variable regions targeted for analysis; for further details, please refer to Kim et al. [

15] and Johnson et al. [

16]. Three different approaches were then used to screen for sequence artifacts. OTUs were screened for chimeric sequences using the ‘chimera.slayer’ [

17] and ‘chimera.uchime’ [

18] commands in MOTHUR (v.1.44.1) [

14]. The 5’ and 3’ ends of OTUs were also evaluated using a database alignment search-based approach; when compared to their closest match of equal or longer sequence length from the NCBI ‘nt’ database, as determined by blastn [

19], OTUs with more than five nucleotides missing from the 5′ or 3′ end of their respective alignments were designated as artifacts. Finally, OTUs with only one or two assigned reads were subjected to an additional screen, where only sequences with a perfect or near-perfect match (maximum 1% of dissimilar nucleotides) to a sequence in the NCBI ‘nt’ database were kept for analysis. All OTUs and their assigned reads that were flagged as artifacts during these screens were subsequently removed from further analyses. The closest valid relatives for the most abundant OTUs were identified by searches with blastn against the ‘refseq_rna’ database [

19].

Curated datasets were rarefied to 15,000 sequences using custom Perl scripts to generate alpha diversity indices. Using the MOTHUR (v.1.44.1) open-source software package [

14], the alpha diversity indices ‘Observed OTUs’, ‘Chao’, ‘Ace’, ‘Shannon’ and ‘Simpson’ were determined using the ‘summary.single’ command.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

The research was conducted as a completely randomized design. Repeated data were analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS (SAS software version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Lambs were treated as a random independent variable; treatment day and their interaction were treated as fixed effects. Weights, IgG concentrations (total and relative), percentage IgG remaining, and ovalbumin antibody S:P ratio were the dependent variables. Lamb, treatment, and time were included in the class statement; time was included in the repeated statement; and dependent variables were included in the model statement. Least Square Means were separated using the PDIFF option of the LSMEANS statement when interactions P values were > 0.05 but ≤ 0.10.

Statistical testing of bacterial composition data was performed in ‘R’ (Version 3.6.0). A t-test was used to compare alpha diversity indices (parametric), while a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare OTU abundance data (non-parametric).

For all data collected, P values ≤ 0.05 are considered significant. Tendencies are described when P values are > 0.05 but ≤ 0.10.

4. Discussion

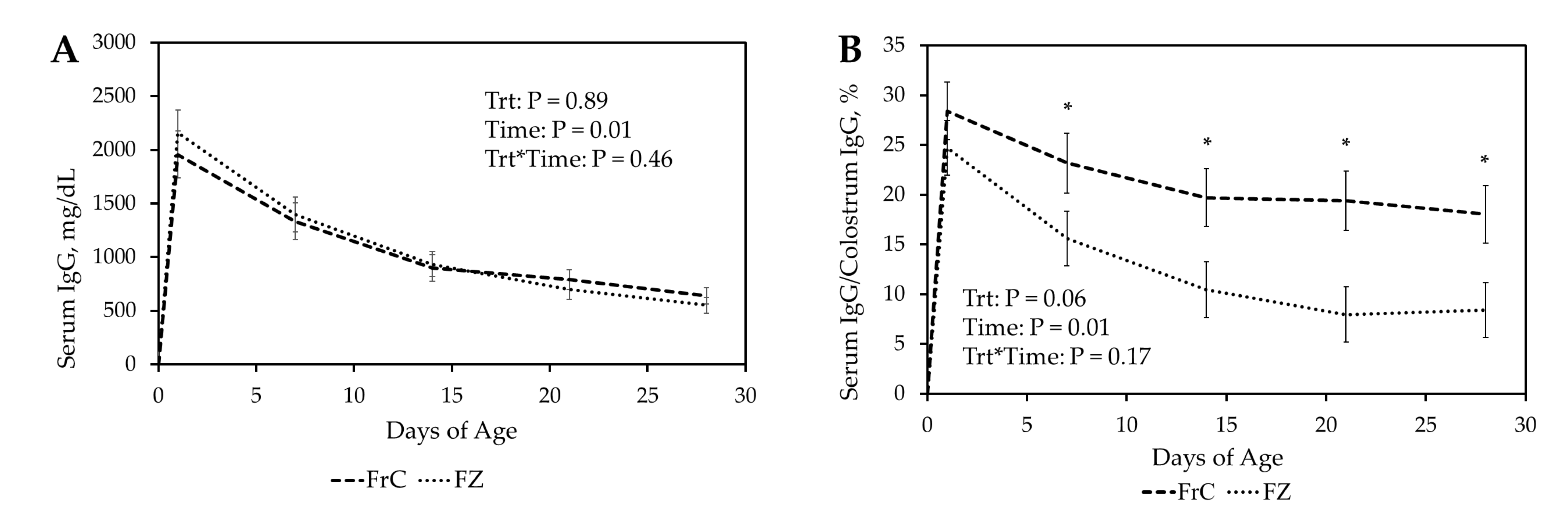

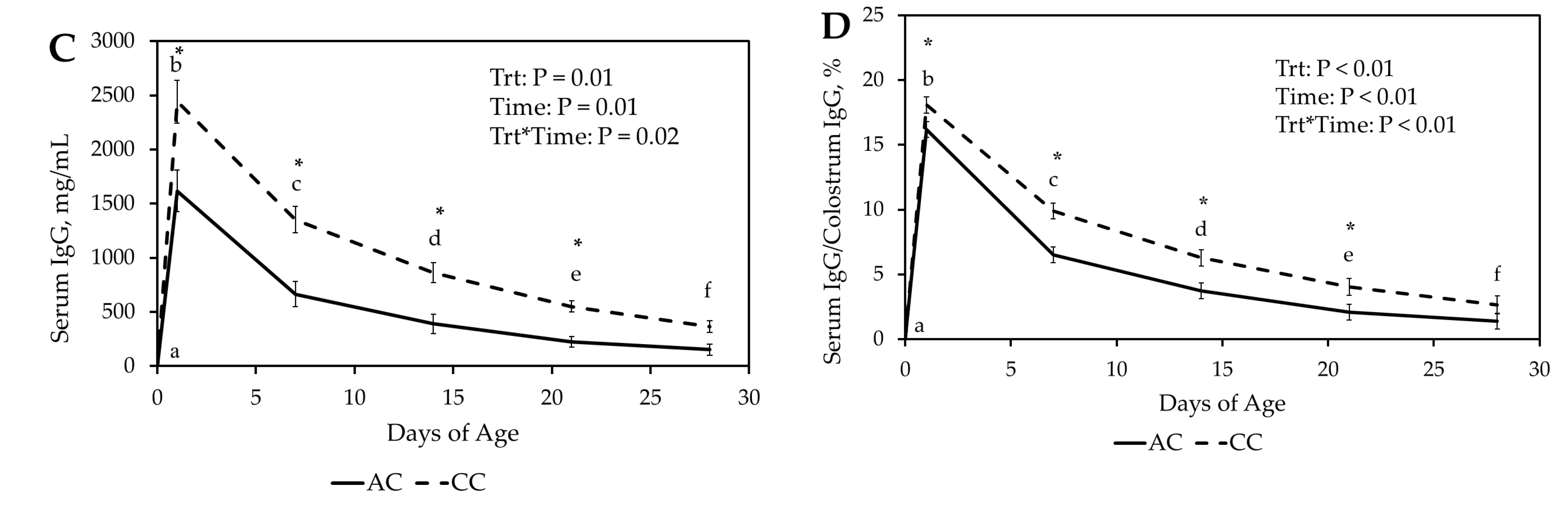

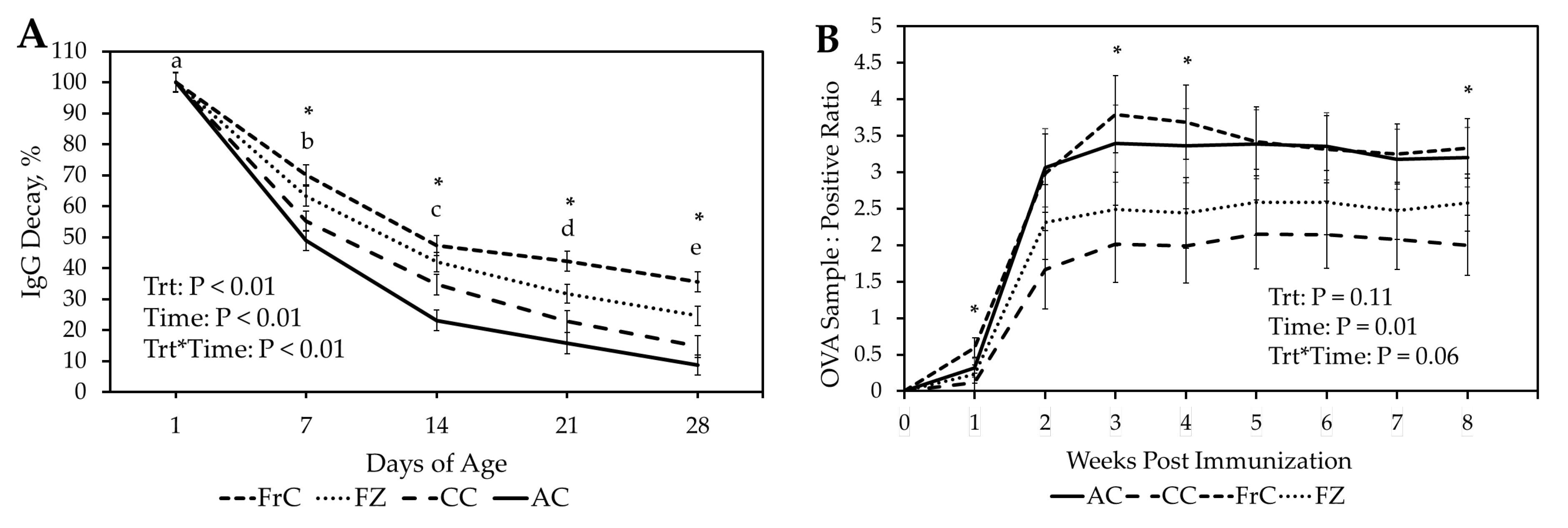

Our results demonstrated that fresh ewe colostrum provided the greatest relative IgG concentration and the slowest IgG decay. Lambs receiving fresh colostrum had a faster and higher antibody response to ovalbumin than lambs receiving cattle colostrum. The ovalbumin antibody response to artificial colostrum was similar to fresh colostrum, while lambs receiving frozen ewe colostrum had an intermediate ovalbumin antibody response.

Colostral IgG concentrations varied across colostral sources. To account for these differences, we calculated relative serum IgG by dividing the serum IgG concentration by the corresponding colostrum IgG concentration. To standardize colostrum dose across all lambs, we dosed each lamb with 65mL/kg, an amount similar to the approximate blood volume per unit of body weight in neonatal lambs [

20]. This approach ensured consistency of the colostrum-to-blood volume ratio, regardless of birthweight. Additionally, we analyzed serum IgG percent decay of each colostrum source to quantify IgG remaining in the lamb relative to what they received.

Lamb relative serum IgG concentrations were greatest at 24 h in FrC and FZ, followed by CC and finally AC treatment groups. This suggests that passive absorption occurs more efficiently with ovine IgG compared to bovine IgG. The increase in efficiency of passive transfer may be due to ovine IgG-specific uptake pathways in the enterocytes of newborn lambs [

21]. One known mechanism involves the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), which specifically binds the Fc region of maternal IgG in the intestinal lumen and facilitates transcytosis across the enterocyte [

21]. It is unclear whether bovine IgG molecules can bind and be transported by the ovine FcRn, or if they are transported mainly by nonspecific pathways like paracellular permeability or micropinocytosis [

22,

23]. The greater percentage of IgG absorbed in the CC group over the AC group could be a result of the greater concentration of IgG mg/dL in CC compared to AC, creating a stronger concentration gradient that could have increased passive transfer.

At 24 h, relative serum IgG concentrations remained greatest in the FrC group, followed by FZ, CC, and AC, respectively. Despite IgG in FZ being absorbed at the same rate as FrC, relative FZ IgG levels decreased at a faster rate than FrC. One possible explanation is that freezing colostrum may induce structural or functional damage that results in a reduced half-life of IgG in lambs. While the effects of freezing ewe colostrum on IgG concentration have not been evaluated, studies in sows and humans suggest that colostrum can be frozen for up to three months without significantly impacting IgG concentrations [

24,

25]. However, there is little information on how freezing affects the half-life of IgG once passively absorbed by the neonate. The half-life of IgG in lambs is expected to be around seven days [

26]. Bovine IgG appears to have a similar half-life in lambs, as the AC and CC treatment groups both experienced a reduction of approximately half each week. The FrC and FZ treatment groups showed more sustained concentrations of IgG, potentially because ovine IgG had a longer half-life than bovine IgG in the neonates. Host production of IgG is another potential contributor to why the FrC group had more sustained relative IgG concentrations.

Colostrum contains multiple bioactive components including maternal leukocytes, cytokines, and hormones, all of which may impact immune development [

7,

8,

27]. Studies in human colostrum indicate that cytokines are present after a freeze-thaw cycle [

27]. However, cytokines usually have short half-lives [

28], which suggests that a freeze-thaw process could significantly decrease their concentration in the colostrum. In calves, colostrum-derived pro-inflammatory cytokines promote neonate immune development by recruiting lymphocytes to the mucosal barrier [

8]. Without the presence of these cytokines, FZ, CC, and AC groups could have experienced delayed immune development in our study. Furthermore, maternal leukocytes in the colostrum increase antigen-presenting cells, which promote the development of the adaptive immune response [

7]. While maternal leukocytes can survive the freezing process with just a 10% death loss, their ability to perform the same cellular function post-thaw is unclear [

25]. A reduction in maternal leukocyte function could decrease the efficiency of antigen-presenting cells and result in delayed immune development. Unfortunately, the ovine IgG RID plates cross-reacting with bovine IgG prevented us from measuring host production of IgG in the AC and CC groups. More precise IgG detection techniques that allow for separate detection of bovine IgG and ovine IgG would enable us to have a more complete understanding of how bovine colostrum sources impact host production of IgG early in neonatal life.

The FrC group showed a more rapid and robust antibody response to the ovalbumin challenge compared to those receiving CC. As we observed with the relative IgG data, it appears that the lambs receiving FrC were capable of synthesizing IgG molecules earlier, which coincides with the increased ovalbumin-specific antibodies seen in our study. This is likely due to the factors outlined previously, i.e., cytokines, hormones, and maternal leukocytes present in the fresh ewe colostrum. These immune system stimulatory factors could have fostered earlier immune development, which would result in the more rapid and robust response we observed. Another possibility is that the bovine IgG received by the CC and AC groups bound to pathogens, and the fragment crystallizable region of the bovine IgG molecule was unable to interact with host immune cells. This would result in suppressed development because host immune cells would have delayed exposure to pathogens, and consequently, the antibody-activated presentation pathways would not be stimulated. Some ability for cross-species interaction between the Fc region of IgG and the host Fc receptor has been demonstrated in human and mouse models [

29]. More research is needed to understand the interaction between the Fc regions of bovine IgG and the ovine Fc IgG receptor. Interestingly, the AC treatment group showed a similar response to the ovalbumin compared to the FrC group, even in the absence of the bioactive factors outlined above. This indicates that there are likely colostrum-independent pathways for adaptive immune development. One potential explanation is the decreased inhibition of maternal antibodies that may limit the neonate’s immune system from being exposed to pathogens. The AC colostrum group had the lowest concentration of antibodies present for the first 28 days of life. This low concentration of “maternal” antibodies would have coated fewer pathogens, which would have increased the lamb’s exposure to uncoated pathogens earlier in life, resulting in earlier development of the adaptive immune system. Studies in calves reported no differences in response to ovalbumin between colostrum-fed and colostrum-deprived calves [

30]. These findings, alongside the response from the AC treatment group, support the hypothesis that when lower levels of maternal immunoglobulins are present, neonatal ruminants can develop their adaptive immune system via colostrum-independent pathways.

We did not see any impact of colostrum on lamb weights at weaning or 90 days of age. Previous studies have reported that serum IgG concentration is positively correlated with pre-weaning average daily gain [

31]. Our data did not support this hypothesis; however, it is worth considering that most of the lambs in our trial remained healthy and were housed in clean, dry pens, with feeders cleaned regularly. Different lamb production systems have different housing and feeders cleansing and disinfecting routines; thus, these differences may affect the control of environmental pathogens that can cause subclinical diseases that can affect lamb performance [

32].

Author Contributions

C. S.: Methodology, data analysis, writing - original draft preparation. B.J.: Methodology, editing. S.L. and C.C.: Methodology, validation, editing. R.N. and B.SP.: Funding acquisition, conceptualization, editing. M.A.V.H.: Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing review and editing.