Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Carbon Materials and TiO2-GO Composites

2.2. Characterization Techniques

2.3. Nitrate Removal

2.3.1. Biological Treatment

2.3.2. Photocatalytic Reduction of Nitrate

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biological Treatment

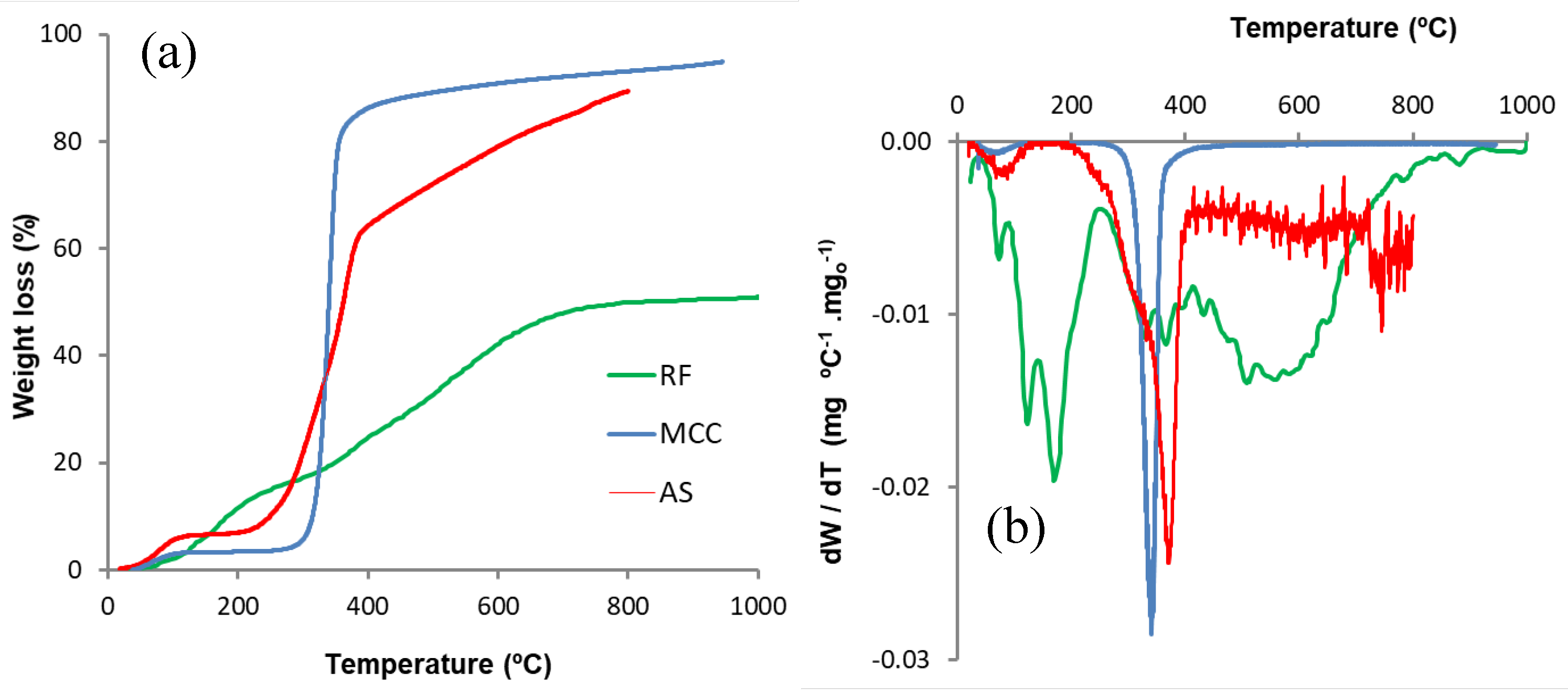

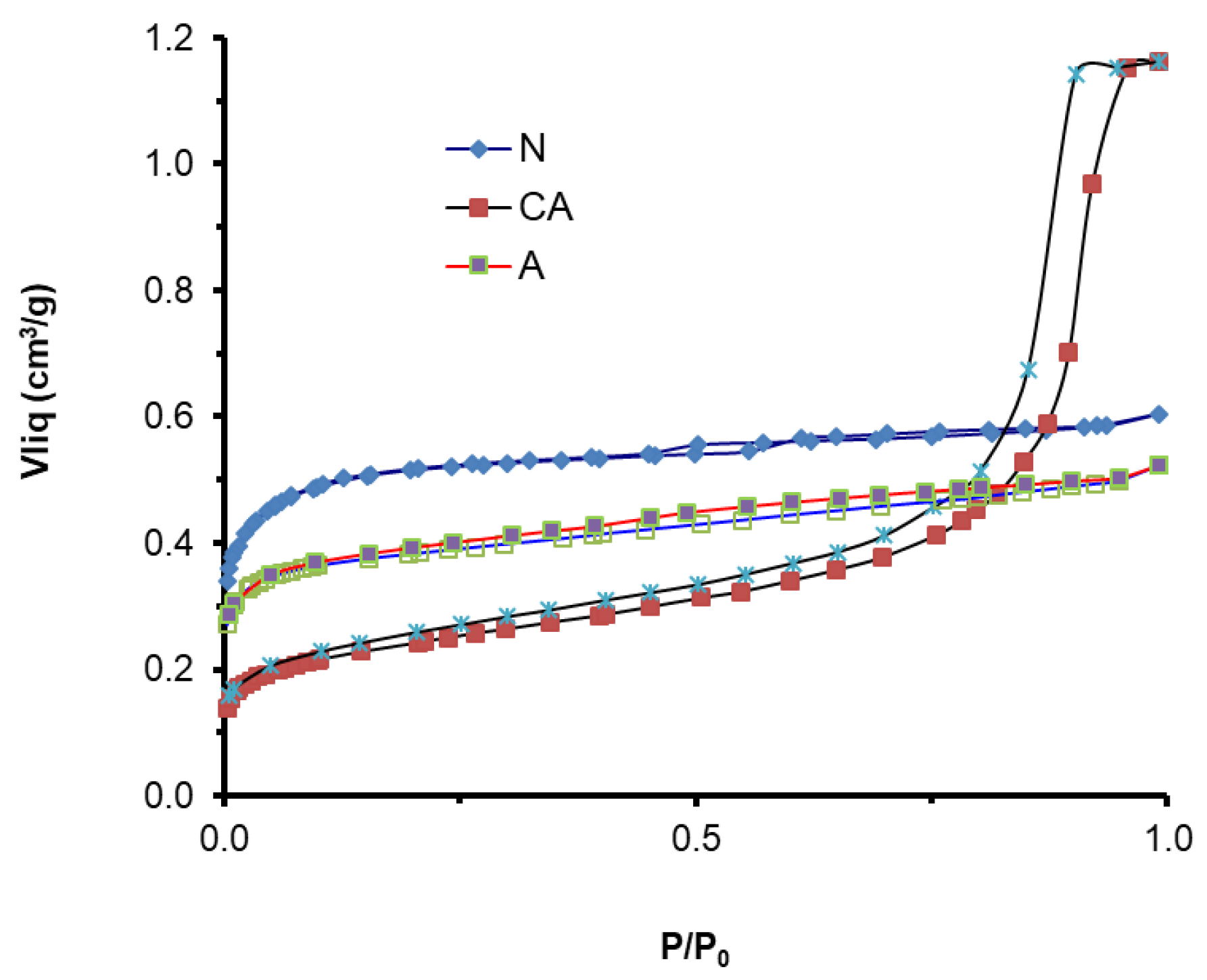

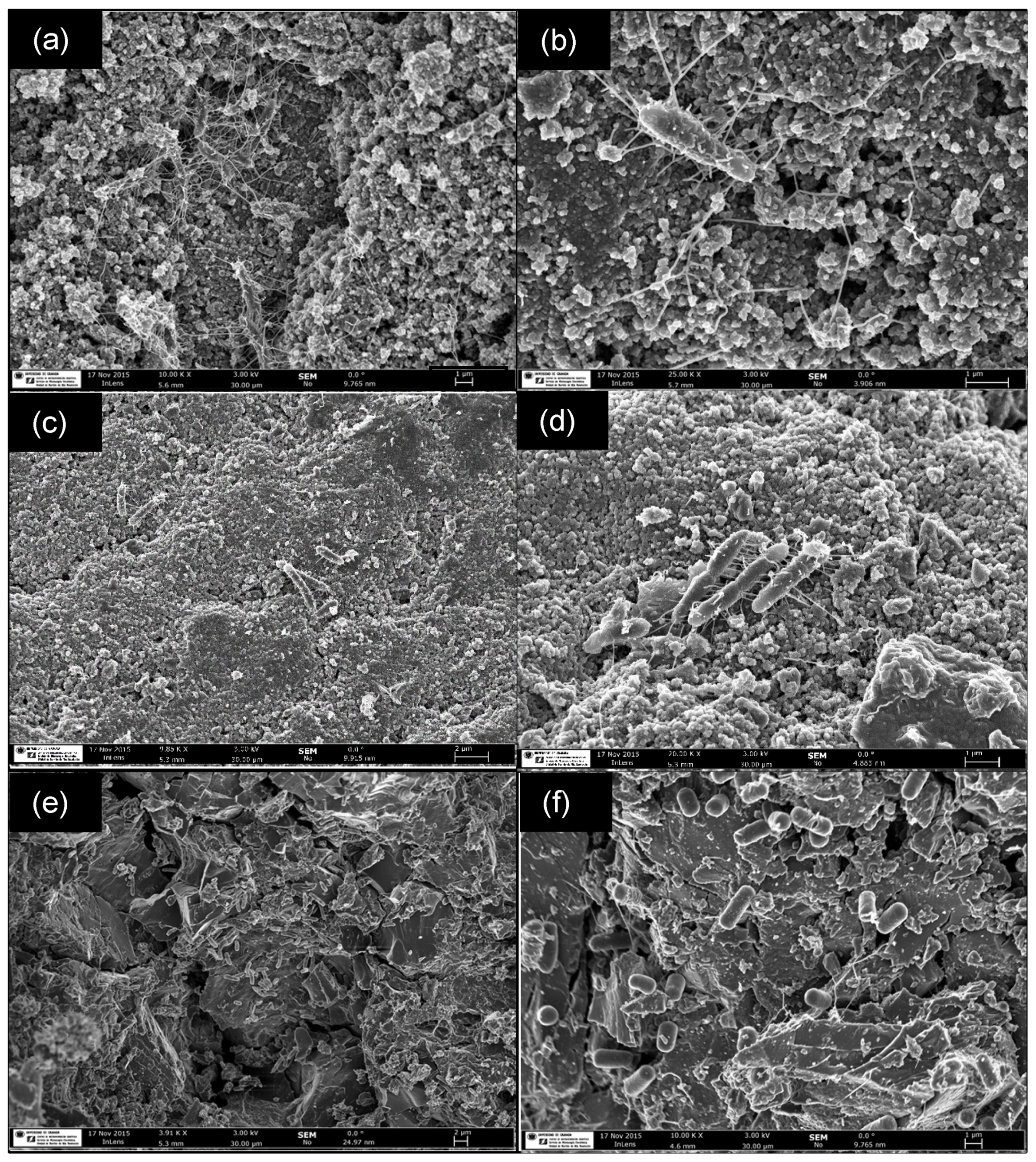

3.1.1. Materials Characterization

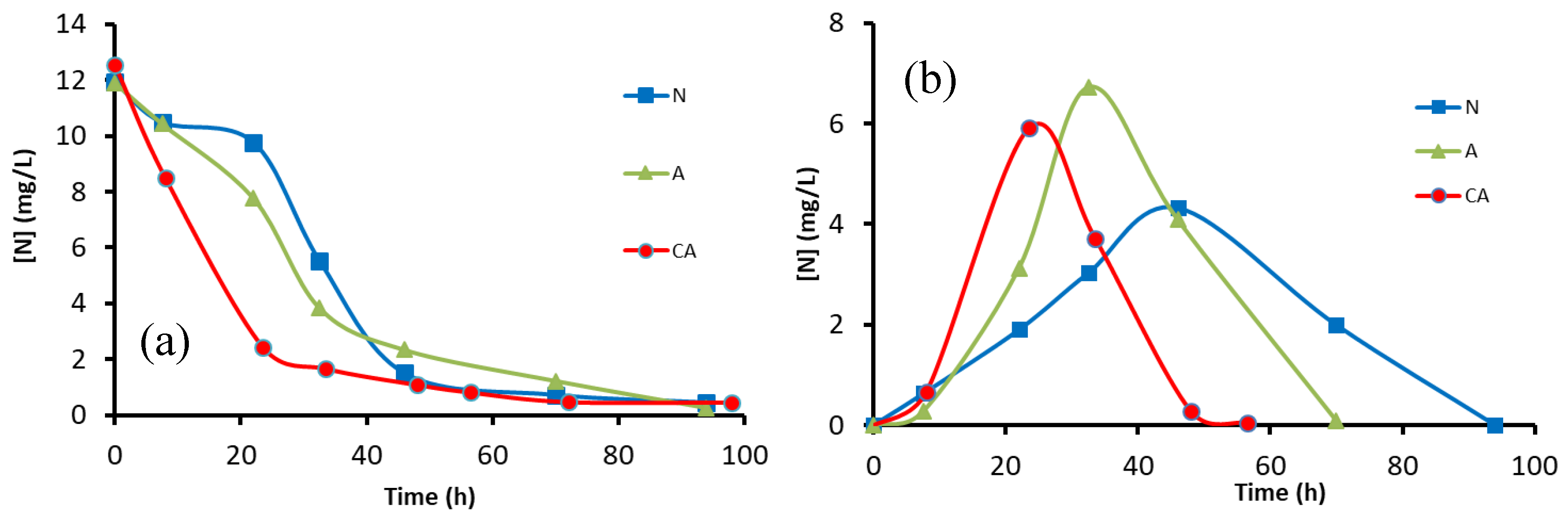

3.1.2. Performance of Adhered Biofilms

3.2. Photocatalytic Reduction of Nitrates

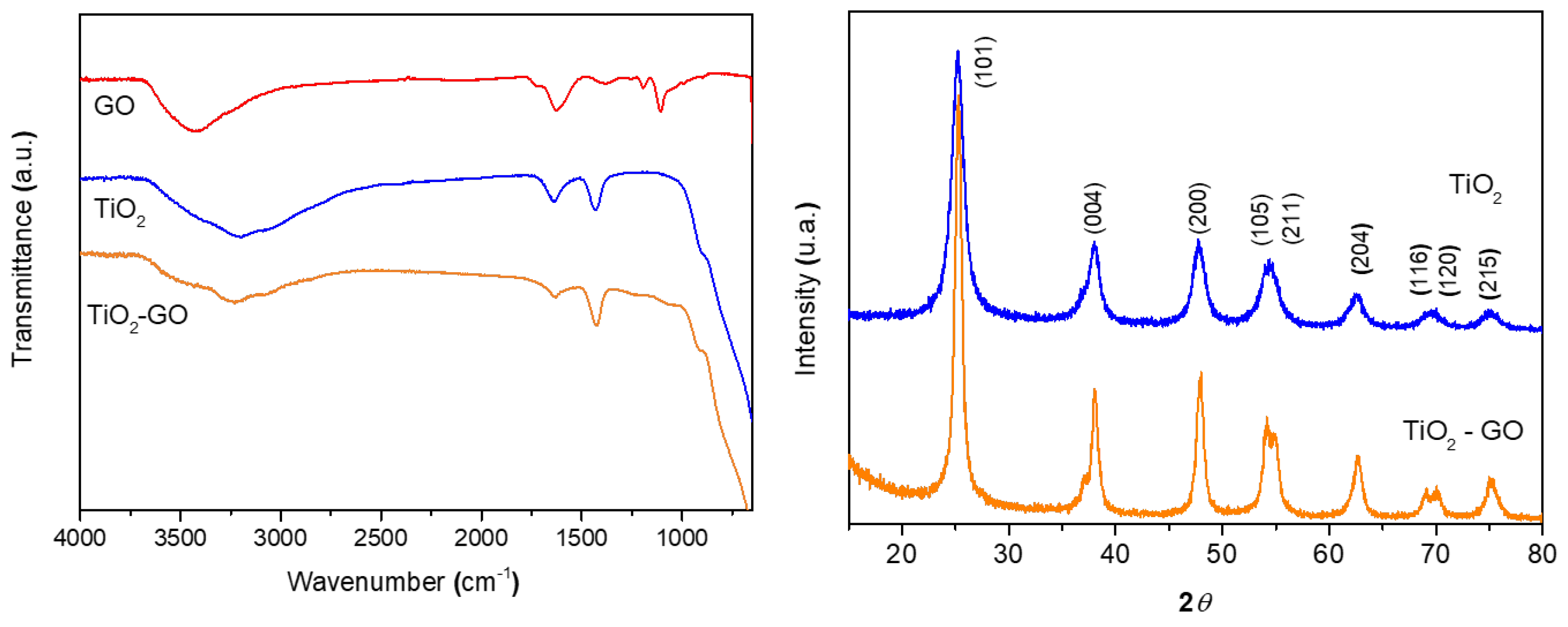

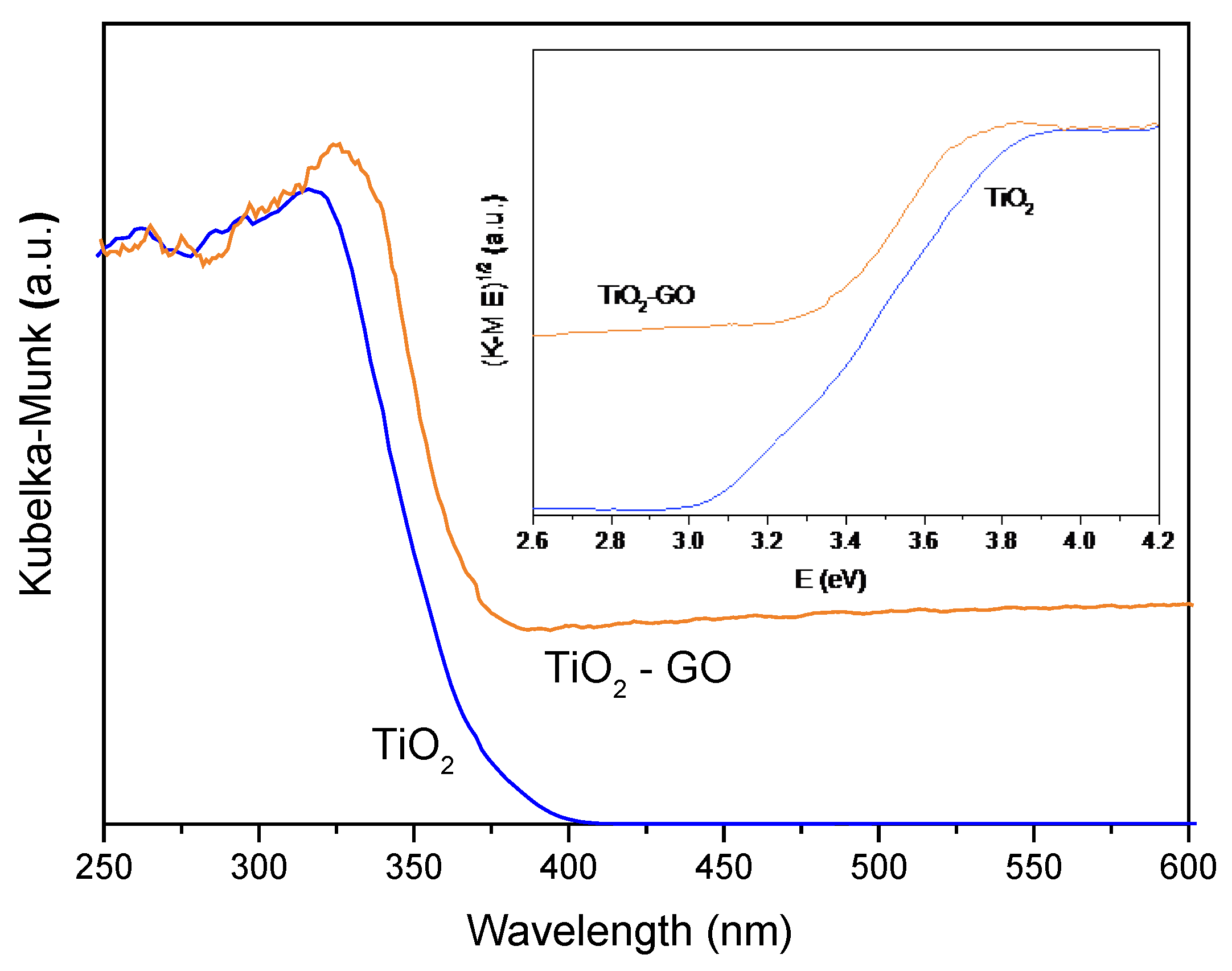

3.2.1. Catalyst Characterization

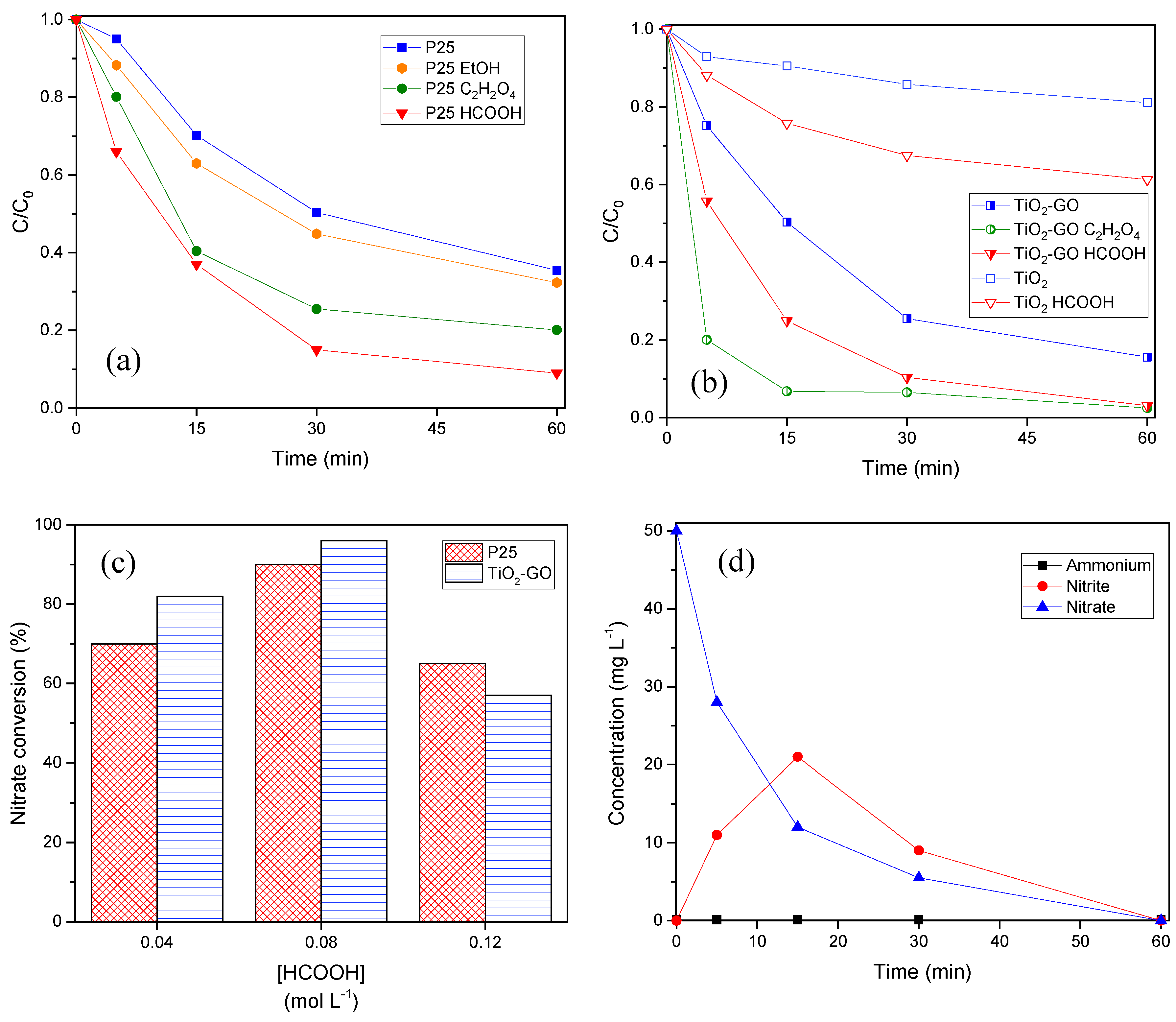

3.2.2. Photocatalytic Performance of the Samples

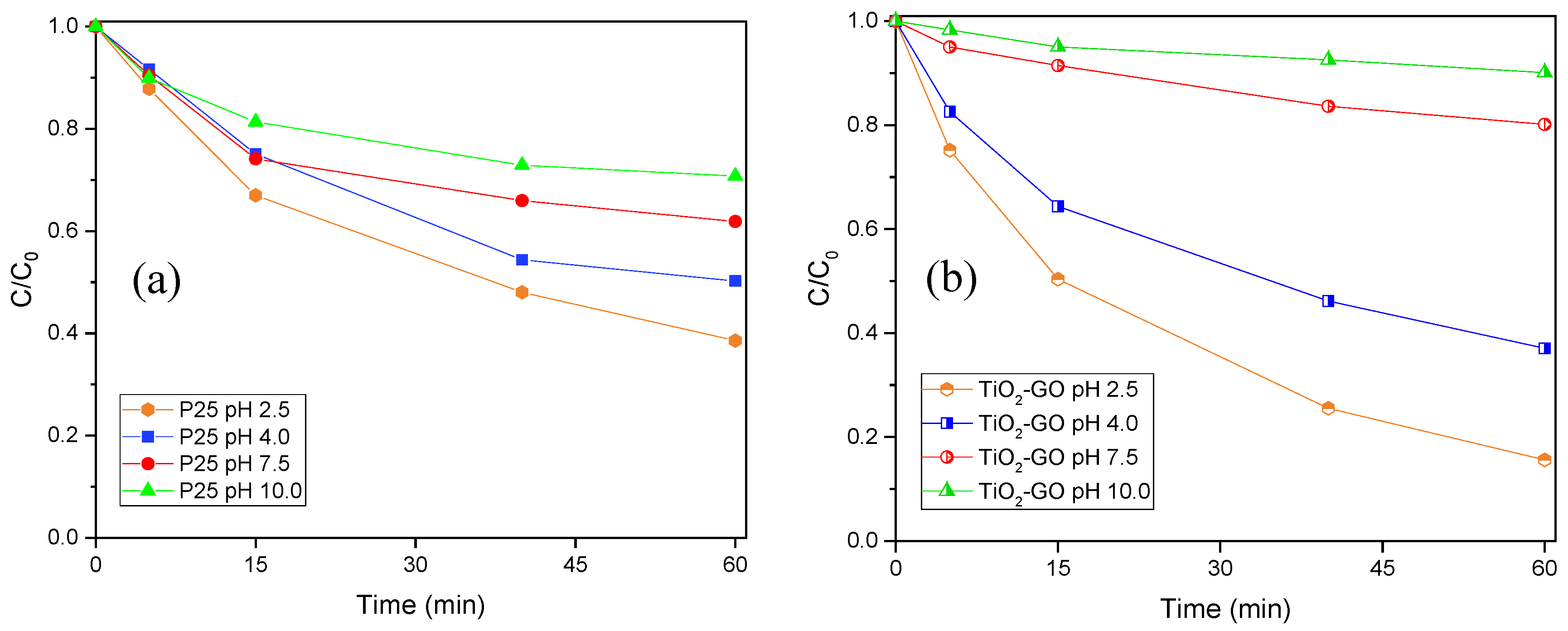

3.2.3. Influence of pH

3.2.4. Effect of hole Scavengers

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez-Jakobsen, F.; Ferrera, I.; Yebra, L.; Mercado, J.M. Two decades of satellite surface chlorophyll a concentration (1998–2019) in the Spanish Mediterranean marine waters (Western Mediterranean Sea): Trends, phenology and eutrophication assessment. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2022, 28, 100855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of on the quality of water intended for human consumption (recast) (Text with EEA relevance). Availabe online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2020/2184/oj. 16 December 2020.

- Zhang, T.; Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Lei, Q.; Luo, J.; An, M.; Du, X.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F. , et al. Sources, fate and influencing factors of nitrate in farmland drainage ditches of the irrigation area. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 367, 122113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateunkeng, J.G.; Boum, A.T.; Bitjoka, L. A binary-level hybrid intelligent control configuration for sustainable energy consumption in an activated sludge biological wastewater treatment plant. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 65, 105902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.-C.; Lu, Y.-Z.; Xu, L.-R. Effects of the carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio on a system coupling simultaneous nitrification and denitrification (SND) and denitrifying phosphorus removal (DPR). Environmental Technology 2021, 42, 3048–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lago, A.; Rocha, V.; Barros, O.; Silva, B.; Tavares, T. Bacterial biofilm attachment to sustainable carriers as a clean-up strategy for wastewater treatment: A review. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 63, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiati, F.C.; Anita, S.H.; Nurhayat, O.D.; Chempaka, R.M.; Yanto, D.H.Y.; Watanabe, T.; Wilén, B.-M. Evaluation of batch and fed-batch rotating drum biological contactor using immobilized Trametes hirsuta EDN082 for non-sterile real textile wastewater treatment. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2024, 12, 113241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrabés, N.; Sá, J. Catalytic nitrate removal from water, past, present and future perspectives. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2011, 104, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Chen, C.; Bao, C.; Gu, J.-n.; Li, K.; Jia, J. Nitrate reduction to nitrogen in wastewater using mesoporous carbon encapsulated Pd–Cu nanoparticles combined with in-situ electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 362, 121346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, A.; Domen, K.; Maruya, K.-i.; Onishi, T. Photocatalytic Reduction of NO3− to Form NH3 over Pt–TiO2. Chemistry Letters 1987, 16, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintar, A.; vetinc, M.; Levec, J. Hardness and Salt Effects on Catalytic Hydrogenation of Aqueous Nitrate Solutions. Journal of Catalysis 1998, 174, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, O.S.G.P.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Órfão, J.J.M.; Faria, J.L.; Silva, C.G. Photocatalytic nitrate reduction over Pd–Cu/TiO2. Chemical Engineering Journal 2014, 251, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadori, E.; Compagnoni, M.; Tripodi, A.; Freyria, F.; Armandi, M.; Bonelli, B.; Ramis, G.; Rossetti, I. Photoreduction of nitrates from waste and drinking water. Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 17404–17413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Z. TiO2-based catalysts for photocatalytic reduction of aqueous oxyanions: State-of-the-art and future prospects. Environment International 2020, 136, 105453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Liu, N.; Wei, Y.; Lu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Ye, Z. The mechanism of efficient photoreduction nitrate over anatase TiO2 in simulated sunlight. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, Y.A.; El Maradny, A.A.; Al Farawati, R.K. Photocatalytic reduction of nitrate in seawater using C/TiO2 nanoparticles. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2016, 328, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Torres, S.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Pérez-Cadenas, A.F.; Carrasco-Marín, F. Textural and mechanical characteristics of carbon aerogels synthesized by polymerization of resorcinol and formaldehyde using alkali carbonates as basification agents. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2010, 12, 10365–10372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummers Jr, W.S.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. Journal of the american chemical society 1958, 80, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Morales-Torres, S.; Likodimos, V.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Faria, J.L.; Falaras, P.; Silva, A.M.T. Advanced nanostructured photocatalysts based on reduced graphene oxide-TiO2 composites for degradation of diphenhydramine pharmaceutical and methyl orange dye. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2012, 123-124, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.C.; Donnet, J.B.; Stoeckli, F. Active Carbon; Bansal, R.C. , Donnet, J.B., Stoeckli, F., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon y Leon, C.A.; Solar, J.M.; Calemma, V.; Radovic, L.R. Evidence for the protonation of basal plane sites on carbon. Carbon 1992, 30, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesserű, P.; Kiss, I.; Bihari, Z.; Polyák, B. Investigation of the denitrification activity of immobilized Pseudomonas butanovora cells in the presence of different organic substrates. Water Research 2002, 36, 1565–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Ritter, J.A. Effect of synthesis pH on the structure of carbon xerogels. Carbon 1997, 35, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanasios, K.A.; Vasiliadou, I.A.; Pavlou, S.; Vayenas, D.V. Hydrogenotrophic denitrification of potable water: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010, 180, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, G.; McCarthy, K.D.; Mehta, T.; Nicoll, J.S.; Tuominen, M.T.; Lovley, D.R. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 2005, 435, 1098–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosdrecht, M.C.v.; Lyklema, J.; Norde, W.; Schraa, G.; Zehnder, A.J. Electrophoretic mobility and hydrophobicity as a measured to predict the initial steps of bacterial adhesion. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1987, 53, 1898–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, L.D.; Weibel, D.B. Physicochemical regulation of biofilm formation. MRS Bulletin 2011, 36, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Toledo, M.I.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Morales-Torres, S.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M. Supported Biofilms on Carbon–Oxide Composites for Nitrate Reduction in Agricultural Waste Water. Molecules 2021, 26, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Hódar, F.J. Advances in the development of nanostructured catalysts based on carbon gels. Catalysis Today 2013, 218-219, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Morales-Torres, S.; Ribeiro, F.; Silva, E.R.; Pérez-Cadenas, A.F.; Carrasco-Marín, F.; Oliveira, F.A.C. Development of Carbon Coatings for Cordierite Foams: An Alternative to Cordierite Honeycombs. Langmuir 2008, 24, 3267–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paritosh, K.; Kesharwani, N. Biochar mediated high-rate anaerobic bioreactors: A critical review on high-strength wastewater treatment and management. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 355, 120348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Su, J.; Wang, J.; Ali, A.; Qian, K.; Wu, X. Modified biochar improved simultaneous nitrate removal and soluble microbial products regulation in low carbon wastewater: Insights from the biocarrier and community function. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 65, 105762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.G.; Faria, J.L. Photocatalytic oxidation of benzene derivatives in aqueous suspensions: Synergic effect induced by the introduction of carbon nanotubes in a TiO2 matrix. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2010, 101, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, D.T.; Baeza, J.A.; Alemany-Molina, G.; Calvo, L.; Gilarranz, M.A.; Morallón, E.; Cazorla-Amorós, D. Catalytic nitrate reduction using a Pd-Cu catalysts supported on carbon materials with different porous structure. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2025, 13, 115979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, I.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Mohedano, A.F.; Diaz, E. N-doped activated carbon as support of Pd-Sn bimetallic catalysts for nitrate catalytic reduction. Catalysis Today 2023, 423, 114011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Chen, R.; Xu, S.; Xia, X.; Zhao, F.; Ren, X.; Lu, Y.; Gao, L.; Bao, J.; Liu, A. Efficient Co and GO co-doped TiO2 catalysts for the electrochemical reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Catalysis Science & Technology 2025, 15, 1445–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xia, H.; Jiang, K.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Yin, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, H.; Yang, W. High-efficiency nitrate reduction to nitrogen using PdCu dual-atom electrocatalysts anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 519, 165362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Richard, C.; Ferronato, C.; Chovelon, J.-M.; Sleiman, M. Investigating the performance of biomass-derived biochars for the removal of gaseous ozone, adsorbed nitrate and aqueous bisphenol A. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 334, 2098–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.M.; Asghar, B.H.M.; Muathen, H.A. Facile synthesis of mesoporous bicrystallized TiO2(B)/anatase (rutile) phases as active photocatalysts for nitrate reduction. Catalysis Communications 2012, 28, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, J.; Agüera, C.A.; Gross, S.; Anderson, J.A. Photocatalytic nitrate reduction over metal modified TiO2. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2009, 85, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Molina, Á.; Morales-Torres, S.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M. Functionalized Graphene Derivatives and TiO2 for High Visible Light Photodegradation of Azo Dyes. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Poyatos, L.T.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Morales-Torres, S.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J. Novel strategies to develop efficient carbon/TiO2 photocatalysts for the total mineralization of VOCs in air flows: Improved synergism between phases by mobile N-, O- and S-functional groups. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 508, 160986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Molina, Á.; Morales-Torres, S.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M. Functionalization of graphitic carbon nitride/ZnO heterojunctions with zinc cyanamide groups: A powerful approach for photocatalytic degradation of anticancer drugs. Separation and Purification Technology 2025, 364, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regadera-Macías, A.M.; Morales-Torres, S.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J. Ethylene removal by adsorption and photocatalytic oxidation using biocarbon –TiO2 nanocomposites. Catalysis Today 2023, 413-415, 113932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirikaram, N.; Pérez-Molina, Á.; Morales-Torres, S.; Salemi, A.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M. Photocatalytic Perfomance of ZnO-Graphene Oxide Composites towards the Degradation of Vanillic Acid under Solar Radiation and Visible-LED. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Morales-Torres, S.; Likodimos, V.; Falaras, P.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Faria, J.L.; Silva, A.M.T. Role of oxygen functionalities on the synthesis of photocatalytically active graphene–TiO2 composites. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2014, 158-159, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Torres, S.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Faria, J.L.; Silva, A.M.T. Design of graphene-based TiO2 photocatalysts-a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2012, 19, 3676–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Lai, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Nanocomposites of TiO2 and Reduced Graphene Oxide as Efficient Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2011, 115, 10694–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, M.J.; Silva, C.G.; Silva, A.M.T.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Han, C.; Morales-Torres, S.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Faria, J.L. Carbon-based TiO2 materials for the degradation of Microcystin-LA. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2015, 170-171, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, Z.; Liu, F.; Shao, Y.; Wang, J.; Wan, H.; Zheng, S. Photocatalytic nitrate reduction over Pt–Cu/TiO2 catalysts with benzene as hole scavenger. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2010, 212, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanbury, D.M. Reduction Potentials Involving Inorganic Free Radicals in Aqueous Solution. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry, Sykes, A.G., Ed. Academic Press: 1989; Vol. 33, pp. 69-138.

- Shi, H.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Bian, J.; Meng, X. Photocatalytic reduction of nitrate pollutants by novel Z-scheme ZnSe/BiVO4 heterostructures with high N2 selectivity. Separation and Purification Technology 2022, 300, 121854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wasgestian, F. Photocatalytic reduction of nitrate ions on TiO2 by oxalic acid. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 1998, 112, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, A.; Meenakshi, S. Photocatalytic reduction of nitrate over Ag–TiO2 in the presence of oxalic acid. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2015, 8, e23–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Support |

Ash (% wt.) |

pHPZC |

SBET (m2 g–1) |

Vtotal (cm3 g–1) |

W0 (cm3 g–1) |

L0 (nm) |

Vmeso (cm3 g–1) |

| CA | null | 6.3 | 594 | 0.69 | 0.21 | 2.5 | 0.48 |

| A | 0.3 | 10.6 | 913 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 1.4 | 0.15 |

| N | 4.8 | 11.0 | 1233 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 1.5 | 0.04 |

| Catalyst |

SBET (m2 g–1) |

Vp (cm3 g−1) |

pHPZC |

Crystalline phase (%) |

Crystallite size (nm) |

Eg(eV) |

| P25 | 52 | 6.5 | 85 (A)* | 22 | 3.20 | |

| TiO2 | 118 | 0.11 | 3.5 | 100 (A)* | 8 | 3.12 |

| TiO2–GO | 120 | 0.17 | 3.0 | 100 (A)* | 4 | 2.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).