1. Introduction

The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSA) is increasing by the year [

1]

. In some cases, a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device is

useful for keeping the airways open and preventing breathing interruptions during sleep [

2]

. However, alternative treatment options are sometimes required for patients who refuse, cannot tolerate, or have contraindications to CPAP.

Oral appliance (OA) use is a treatment method that is well-tolerated by most patients [

2]. CPAP has a stronger effect than OA in ameliorating sleep-disordered breathing [

3], and OA use alone may not completely alleviate severe OSA symptoms. According to previous reports, 75% of patients in the moderate OSA group and 50% of those in the severe OSA group achieved a good response to treatment with OA [

4]. However, most patients generally prefer OA treatment over surgery or CPAP because of its simplicity and convenience of use.

The two most common designs of OA are tongue-retaining devices and mandibular advancing (MA); however, the preferred OA is a customized and tooth-borne appliance developed to make advancing movements of a mandible [

5]. The MAOA can alleviate the condition of the upper airways by changing the positions of the tongue and the connected upper airway structure.

MAOA can be prefabricated or customized; however, the latter is recommended in clinical practice because it is comfortable to wear. Generally, both appliances for the maxilla and mandible are tailored to a specific patient’s dentition in a dental laboratory. There are two techniques for connecting appliances to maintain a MA position: fixed (where the maxilla and mandible are integrated) and semi-fixed (movable, where a connector allows a certain range of motion). In general, semi-fixed MAOAs pose fewer risks of temporomandibular joint symptoms and discomfort compared to fixed ones [

6]. However, semi-fixed movable devices are subject to greater loads during mandibular movement, which predisposes them to breakage. To overcome this drawback, several connection methods have been elaborated [

7,

8].

The Silencor design [

9]

is a well-known connection system for movable MAOAs. Ihara et al. [

10] reported the effectiveness of the Co-Cr wire used as an MAOA connector. However, with long-term connection design advancements and adhesive treatment of MAOA, we have developed a simple connector (NK connector; Morita Corp., Suita, Japan) using high-density polyethylene (HDPE) material [

11]. The development and commercialization of this connector has been shown to have significant clinical benefits for many patients [

6].

Evaluating the clinical outcomes of MAOA treatment and identifying the determinants of success can provide meaningful information for OSA treatment strategies with MAOA. This study aimed to explore the factors associated with OA longevity by performing a survival analysis of MAOAs used for treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This hospital-based retrospective cohort study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Nagasaki University Hospital (approval no. 19111813) and was carried out according to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration II.

In this study, we used the electronic patient medical records of patients who had been diagnosed with OSA and treated with MAOAs at Nagasaki University Hospital over a ten-year period from June 1, 2008, to May 31, 2018. All patients were diagnosed with OSA at the Respiratory Medicine Department and were found to be appropriate for treatment using MAOA after being referred to the Oral Surgery department for oral examination. An oral surgeon examined the oral condition (the presence of caries, periodontal disease, occlusion, temporomandibular joint movement, etc.) and checked a given patient’s suitability for MAOA treatment. Patients with severe periodontal disease or temporomandibular joint disorder and those with few (<12) remaining teeth were referred back to the Respiratory Medicine Department.

Patients considered suitable for MAOA treatment underwent maxillary and mandibular impressions and maxillomandibular registrations. The former were obtained using an alginate impression material. During the maxillomandibular registration, a patient’s mandible was guided so that the amount of forward movement of the mandible composed approximately 60–80% of maximum protrusion, and that of vertical opening was approximately 2–5 mm wider than a normal occlusion position. The patient was asked to maintain this position, and maxillomandibular registration was performed using a silicone registration material. For special occlusal conditions, such as open bite, mandibular retrusion (retrognathia), and deep overbite, the optimal position had been explored separately for each case.

Based on the information obtained from the Oral Surgery department, the OA was fabricated in a dental laboratory (Nagasaki University Hospital Dental Laboratory). The MAOA was basically constructed as a mobile device. The upper and lower appliance components were fabricated separately using the clear transparent polyethylenterephthalat-glycol (PETG) thermoplastic material (DURAN, Scheu Dental GmbH, Iserlohn, Germany) and attached using HDPE connectors (NK connector II, Morita Corp.), one on each side. The surface of the connection part was roughened and treated with dichloromethane, and the connector was attached with the self-curing resin (Unifast III Clear; Morita Corp). Its end was covered with a self-curing resin to ensure sufficient strength. A connector was positioned between a maxillary canine and a mandibular first molar. A single connector was used on each side; however, when instructed by an oral surgeon or after damage, reinforcement by fixing the prosthesis was sometimes performed using two connectors on each side.

The MAOA was fitted in the mouth by an oral surgeon and adjusted as necessary. Then, the patient was instructed on its proper use. After several weeks of use, symptom alleviation was checked, and if any problems arose, the relevant adjustments or repairs were made accordingly. Subsequently, patients were recommended to undergo regular check-ups (at least once every six months).

2.2. Variables

Information on variables presumed to be associated with MAOA survival was gathered from medical records.

The collected participant information covered sex, age at the time of placement, preoperative apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), and oxygen saturation (Sp02). As the information related to MAOA, the data reflected the initial situation, whether the device was repaired or newly produced, and the type of connection (single connector, two connectors, and fixed). Ultimately, relevant data on six variables were obtained.

2.3. Data Source

Data on the patients treated with MAOA were retrieved, and their medical records were followed up until December 11, 2019. Patients who visited only on the day of placement were excluded. Data were managed using Microsoft®️Excel for Mac version 16.78.3 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and checked multiple times to avoid duplication and other errors.

The failures were classified into three patterns: A) destruction anywhere in MAOA, B) connector failure, and C) thermoplastic component breakage. All three of the above patterns were defined as three types of events, and the time until the occurrence of each event was considered the survival time. In the absence of any event, the survival time was censored at the date of the last observation. Survival time was determined using the date of the set as the baseline. Both repaired and remanufactured MAOAs were considered as devices distinct from the original one.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Missing data were adjusted using multiple imputations. The survival time and rate were determined using the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, and survival curves were constructed. Many participants were treated with multiple MAOAs, and it was speculated that personal factors such as the occlusal force might have affected the outcomes. Therefore, the shared frailty analysis involving a mixed-effects model that suggested the same frailty in participants was performed for each of the three failure types. Hazard ratios (HRs) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the variables presumably affecting each failure type. After evaluating the chosen variables with the stepwise method, HRs and CIs were re-estimated. The significance level was set at 5%.

R Studio version 2023.06.2 + 561 (Posit Software, PBC) was employed for the Kaplan–Meier survival and shared frailty analyses.

3. Results

A total of 230 patients with 466 MAOAs were enrolled. The MAOA distribution is shown in

Table 1 (categorical variables) and

Table 2 (continuous variables).

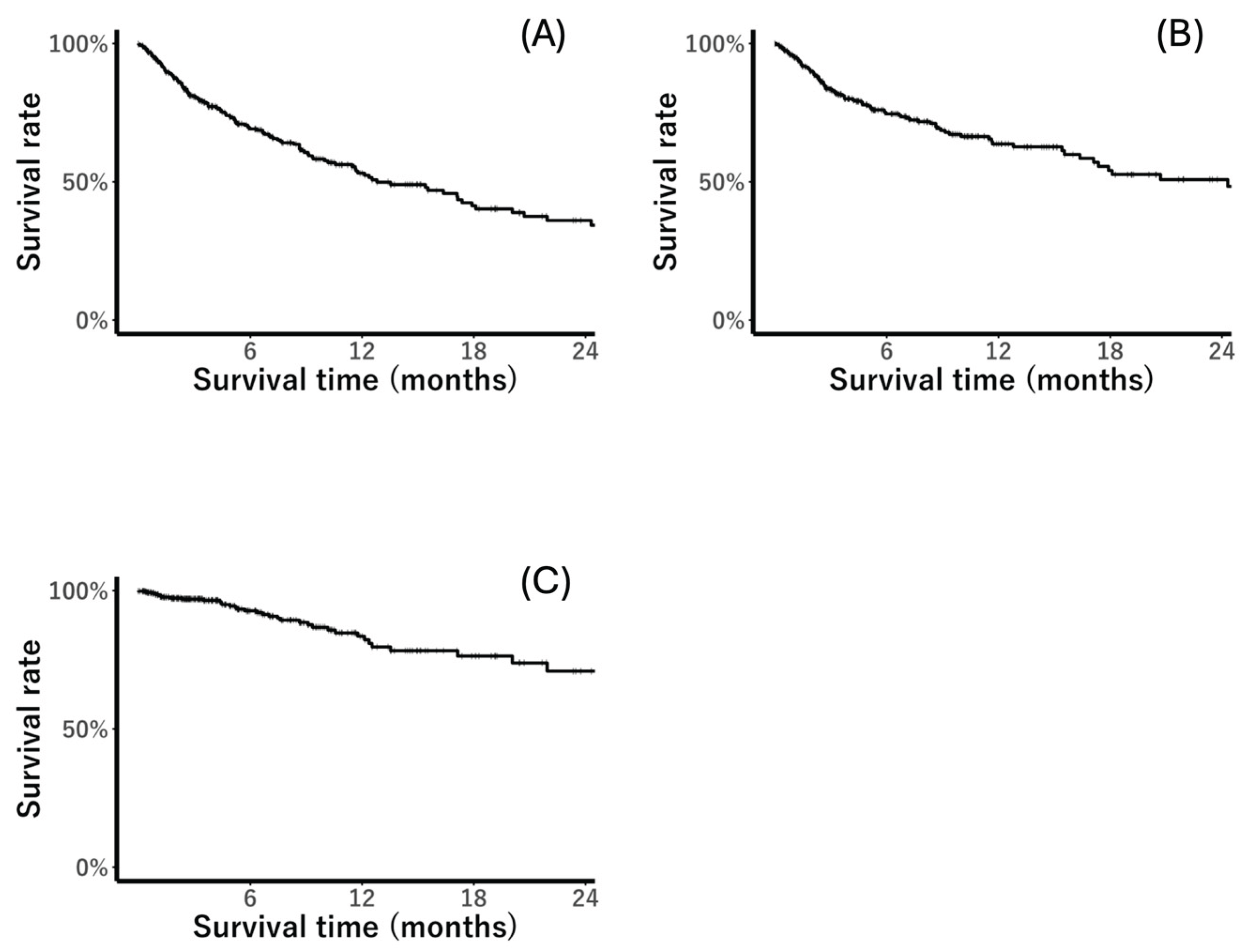

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve for all types of failure is shown in

Figure 1. The survival rate at one year (12 months) was 52.4% for Type A failure, 63.7% for Type B, and 82.2% for Type C. The survival curve for the latter had a smoother shape; that is, the survival rate was always higher than that for Type B. There were 103 Type B failure events (connector failure); however, only three of them involved adhesive failure between a connector and the thermoplastic component, and the remaining 100 cases involved the breakage of the connector itself.

Table 3 reflects the results of the shared frailty analysis for Type A failure. Sex, age, and connection method were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with the outcome.

Table 4 demonstrates the outcomes of the shared frailty analysis for Type A failure after meticulous selection. The HR value of male patients was more than twice as high as that of female patients. In terms of connection method, the HR for a single connector connection was approximately four times higher than that for a fixed connection.

Table 5 displays the outcomes of the shared frailty analysis for Type B failures. The analysis did not converge for the fixation method variables, presumably because the intra-cluster correlations were excessively strong. Therefore, only sex and age were selected as variables for the frailty analysis for Type B failure, and both showed strong correlations (

Table 6). The HRs showed trends similar to those of Type A failures.

Table 7 shows the results of the shared frailty analysis for Type C failures. Although only AHI values were selected after valuable selection, potential confounding factors such as sex and age were included in the final model. Three variables were analyzed (

Table 8); however, none were found to be significantly associated with Type C failure.

4. Discussion

In this study, approximately half of the MAOAs broke within one year. The results of this study demonstrate that the HR for a mobile MAOA was higher than that for a fixed one, suggesting that the mechanical strength of mobile devices is lower than that of fixed ones. However, mobile structures have the advantage of being comfortable to wear. In accordance with a pilot study comparing fixed and semi-fixed OAs [

6], the latter type was found to be superior in terms of the lower incidence of temporomandibular joint pain and higher patient comfort. Overall, this type also showed more promising results in terms of more comfort and a lower incidence of side effects, while the improvements in AHI were similar for both. Therefore, dentists should strive to preserve movable structures while prolonging their survival, and it is essential to identify the associated factors for this purpose.

As shown in

Figure 1, the survival curve for thermoplastic component failure (Type C failure) had a more gentle slope than that for connector failure (Type B failure), indicating that connector failure is the most likely cause of OA failure. This may be explained by the fact that the PETG material had a higher mechanical strength than the connector material, HDPE. PETG is a resin material obtained by adding glycol to PET to render it amorphous and improve its impact resistance. It has the characteristics of being slightly soft, tough, and resistant to impact (Young’s modulus of approximately 5.9 GPa, a tensile strength of 55–75 MPa, an impact strength of 5–20 kJ/m², and a flexural strength of 70–90 MPa) [

12].

Most Type B failures were due to damage to the connector itself and not poor adhesive treatment. To elevate the survival rates of OA, it is desirable to enhance connector strength. In this study, the difference in survival status between the one-connector and fixed types was significant; however, none was detected between the two-connector and fixed types. However, owing to the material properties of HDPE, the range of motion should be smaller in the case of two connectors, which reduces the mobile structure’s significance. Even considering that new and repaired appliances did not differ significantly from each other, there was an issue with connector strength. Therefore, the material and shape of the connector should be examined further.

Sex and age were found to be associated with the OA survival rate. It is well-known that there is a difference in bite force between male and female patients. Through bite force measurements,

sex was found to be a factor significantly associated with maximal bite force, and the mean of male patients was approximately 30% greater than that of female patients [

13]

. In addition, sex-related bite force differences most probably develop post-puberty concomitantly with more pronounced muscle mass growth in males [

14]

. Most of the participants of this study were postpubertal (their mean age was 59 years), and the effect of sex was observed. The low prevalence of OSA before puberty [

15]

might explain these results.

Apnea severity was not found to correlate with the survival rates. In general, the effectiveness of MAOA is not affected by OSA severity [

16]. The force attempting mandibular retraction might be related to oral muscle strength, but not apnea severity.

The main limitation of this study is that the only data collected were those retrieved from medical records. No factors associated with thermoplastic component breakage were found among the study variables. Type C failures might have been associated with factors such as the number, shape, and condition of the remaining teeth and the occlusion pattern, which could not be determined from the medical records. However, connector breakage occurred more frequently than that of the components. Identifying variables associated with connector damage (age and sex) is considered useful for future OSA treatment.

5. Conclusions

MAOA connector strength was significantly associated with the MAOA survival rate. Connectors were more likely to break in younger patients, and this tendency was particularly pronounced in males. When selecting the connection method for MAOA fabrication, sex and age should be taken into account.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.T. and Y.M.; Data curation: Y.M. and N.M.; Investigation: Y.M., N.M., and N.T. Methodology: N.M. and N.T.; Statistical Analysis, N.M. and N.T. Project administration: N.T.; Supervision, N.T.; Roles/Writing—original draft, Y.M., N.M., N.T.; and Writing—review & editing, N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this clinical study was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Nagasaki University Hospital (approval no.: 19111813), approval date: November 19, 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

The need for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective study design, and information about the study was made publicly available to allow patients to opt out.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the staff and patients participating in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHI |

Apnea-hypopnea index |

| CI |

Confidence intervals |

| CPAP |

Continuous positive airway pressure |

| HR |

Hazard ratios |

| MA |

Mandibular advancing |

| MAOA |

Mandibular advancement oral appliances |

| OA |

Oral appliance |

| OSA |

Obstructive sleep apnea |

References

- Iannella, G.; Pace, A.; Bellizzi, M.G.; Magliulo, G.; Greco, A.; De Virgilio, A.; Croce, E.; Gioacchini, F.M.; Re M.; Costantino A.; Casale, M; Moffa, A.; Lechien, J. R.; Cocuzza, S.; Vicini, C.; Caranti, A.; Marchese Aragona, R.; Lentini, M.; Maniaci, A. The global burden of obstructive sleep apnea. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1088. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.P.; Chen, Y.F.; Du, J.K. Obstructive sleep apnea treatment in adults. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, F.; Yan, S.; Chen, L.; Lv, C.; Lu, H. Effectiveness of oral appliances versus continuous positive airway pressure in treatment of OSA patients: An updated meta-analysis. Cranio 2019, 37, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Julián, E.; Pérez-Carbonell, T.; Marco, R.; Pellicer, V.; Rodriguez-Borja, E.; Marco, J. Impact of an oral appliance on obstructive sleep apnea severity, quality of life, and biomarkers. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 1720–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramar K, Dort LC, Katz SG, Lettieri CJ, Harrod CG, Thomas SM, Chervin, R.D. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and snoring with oral appliance therapy: An update for 2015. J. Dent. Sleep. Med. 2015, 2, 71–125. [CrossRef]

- Yanamoto, S.; Harata, S.; Miyoshi, T.; Nakamura, N.; Sakamoto, Y.; Murata, M.; Soutome, S.; Umeda, M. Semi-fixed versus fixed oral appliance therapy for obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized crossover pilot study. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindar, P.; Balaji, K.; Saikiran, K.V.; Srilekha, A.; Alekhya, K. Oral appliances in the management of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Airway 2019, 2, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.D. Oral appliances in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Atlas Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. North. Am. 2007, 15, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, E.; Staats, R.; Virchow, C.; Jonas, I.E. A comparative study of two mandibular advancement appliances for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur. J. Orthod. 2002, 24, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihara, K.; Ogawa, T.; Shigeta, Y.; Kawamura, N.; Mizuno, Y.; Ando, E.; Ikawa, T.; Ishikawa, C.; Nejima, J. The development and clinical application of novel connectors for oral appliance. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2011, 55, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanoue, N.; Nagano, K.; Yanamoto, S.; Mizuno, A. Comparative evaluation of the breaking strength of a simple mobile mandibular advancement splint. Eur. J. Orthod. 2009, 31, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szykiedans, K.; Credo, W.; Osiński, D. Selected mechanical properties of PETG 3-D prints. Procedia Eng. 2017, 177, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, M.; Nassar, M.S.; Cecílio, F.A.; Siéssere, S.; Semprini, M.; Machado-de-Sousa, J.P.; Hallak, J.E.; Regalo, S.C. Age and gender influence on maximal bite force and masticatory muscles thickness. Arch. Oral Biol. 2010, 55, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, S.; Hnat, W.P.; Freudenthaler, J.W.; Marcotte, M.R.; Hönigle, K.; Johnson, B.E. A study of maximum bite force during growth and development. Angle Orthod. 1996, 66, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bixler, E.O.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Ten Have, T.; Tyson, K.; Kales, A. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 1998, 157, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, J.I.; Kim, D.; Ahn, S.J.; Yang, K.I.; Cho, Y.W.; Cistulli, P.A.; Shin, W.C. Efficacy of oral appliance therapy as a first-line treatment for moderate or severe obstructive sleep apnea: A Korean prospective multicenter observational study. J. Clin. Neurol. 2020, 16, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).