Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Current Research Status

2. Theoretical Basis and Coupling Mechanism

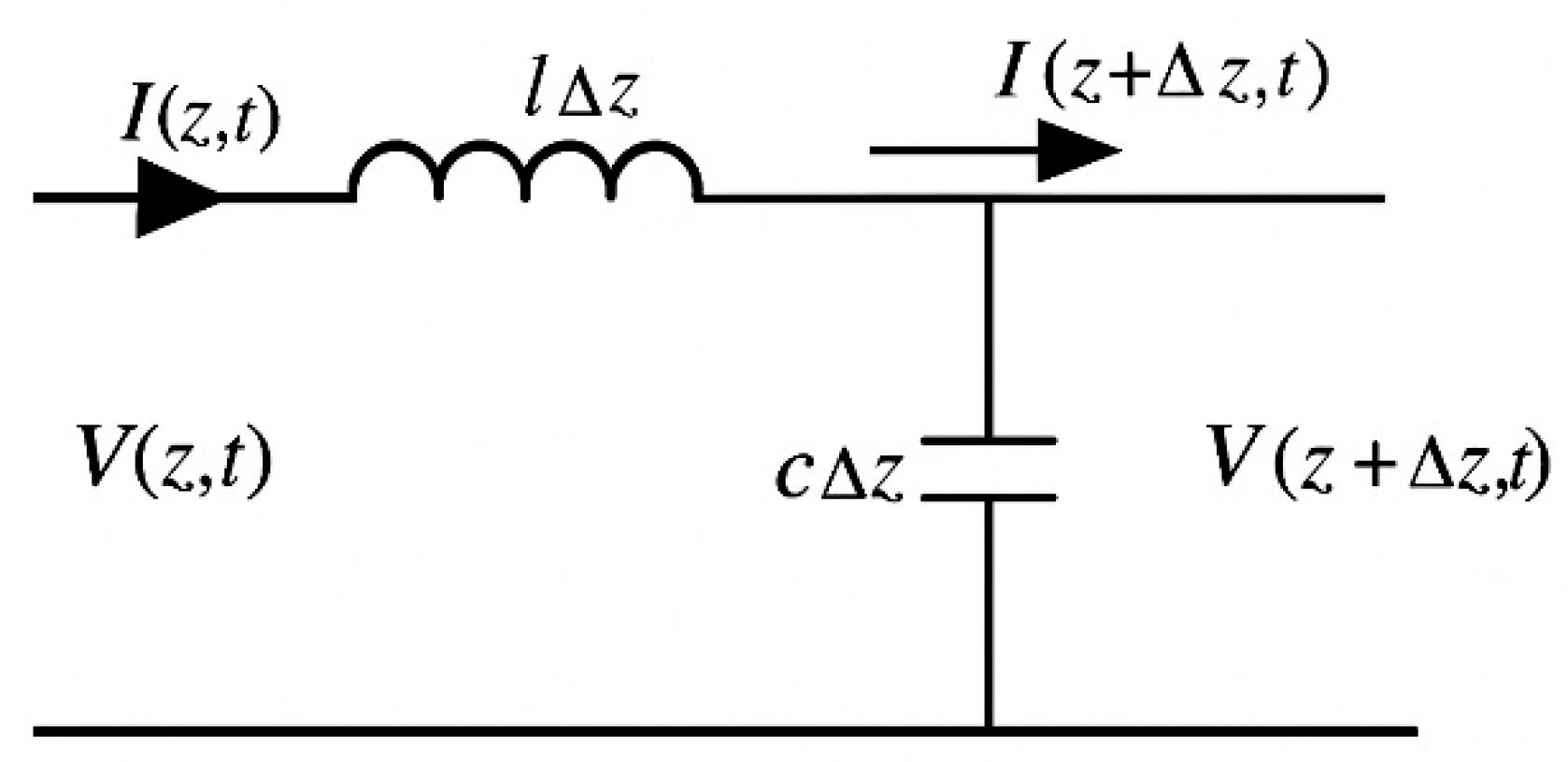

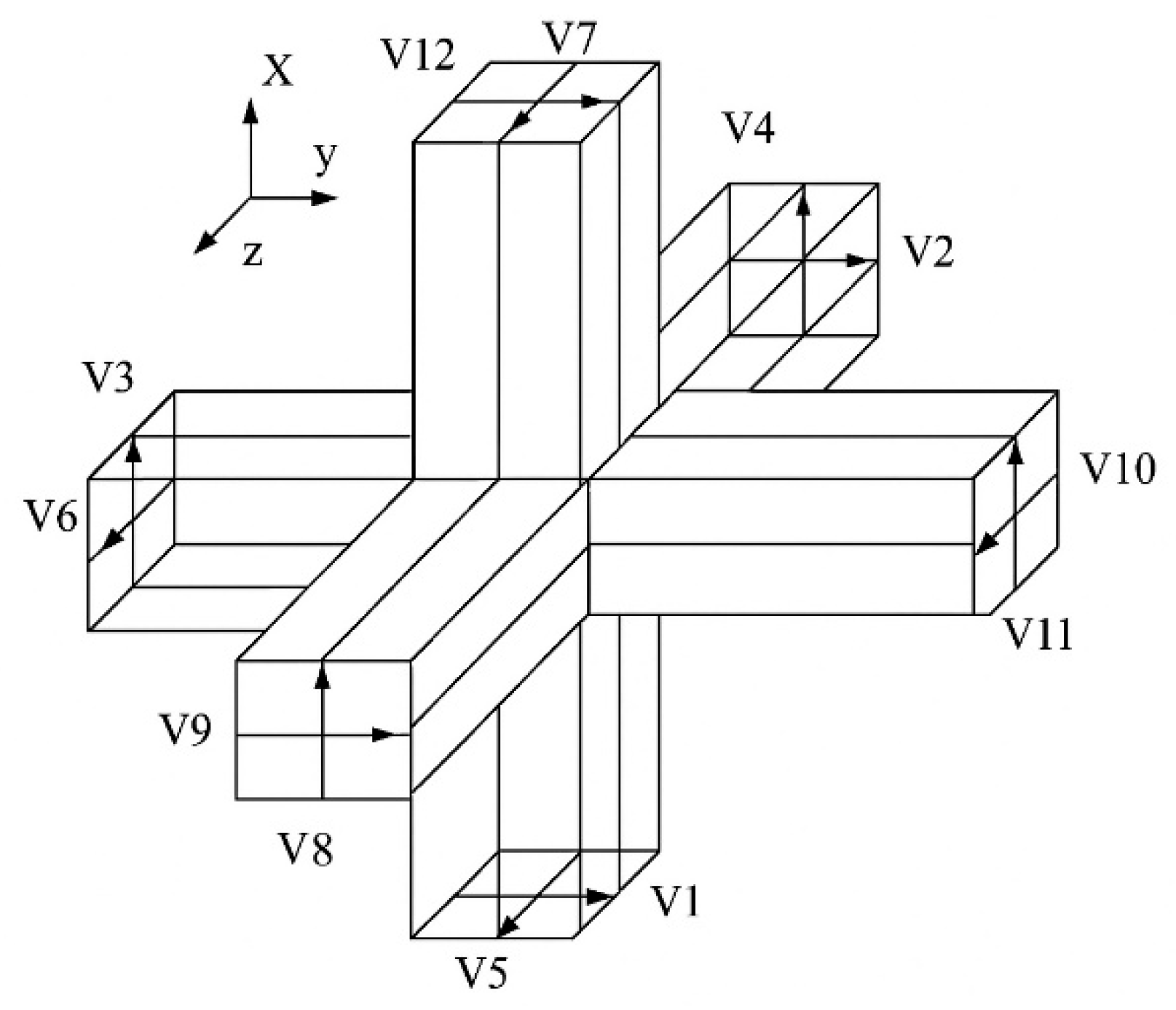

2.1. Transmission Line Matrix (TLM) Theory

2.2. Basic Characteristics of Lightning Electromagnetic Fields

- Origin and Components of Lightning Electromagnetic Fields

- 2

- Frequency Spectrum Characteristics of Lightning

- 3

- Time Characteristics and Waveform Features

- 4

- Spatial Distribution Characteristics

- 5

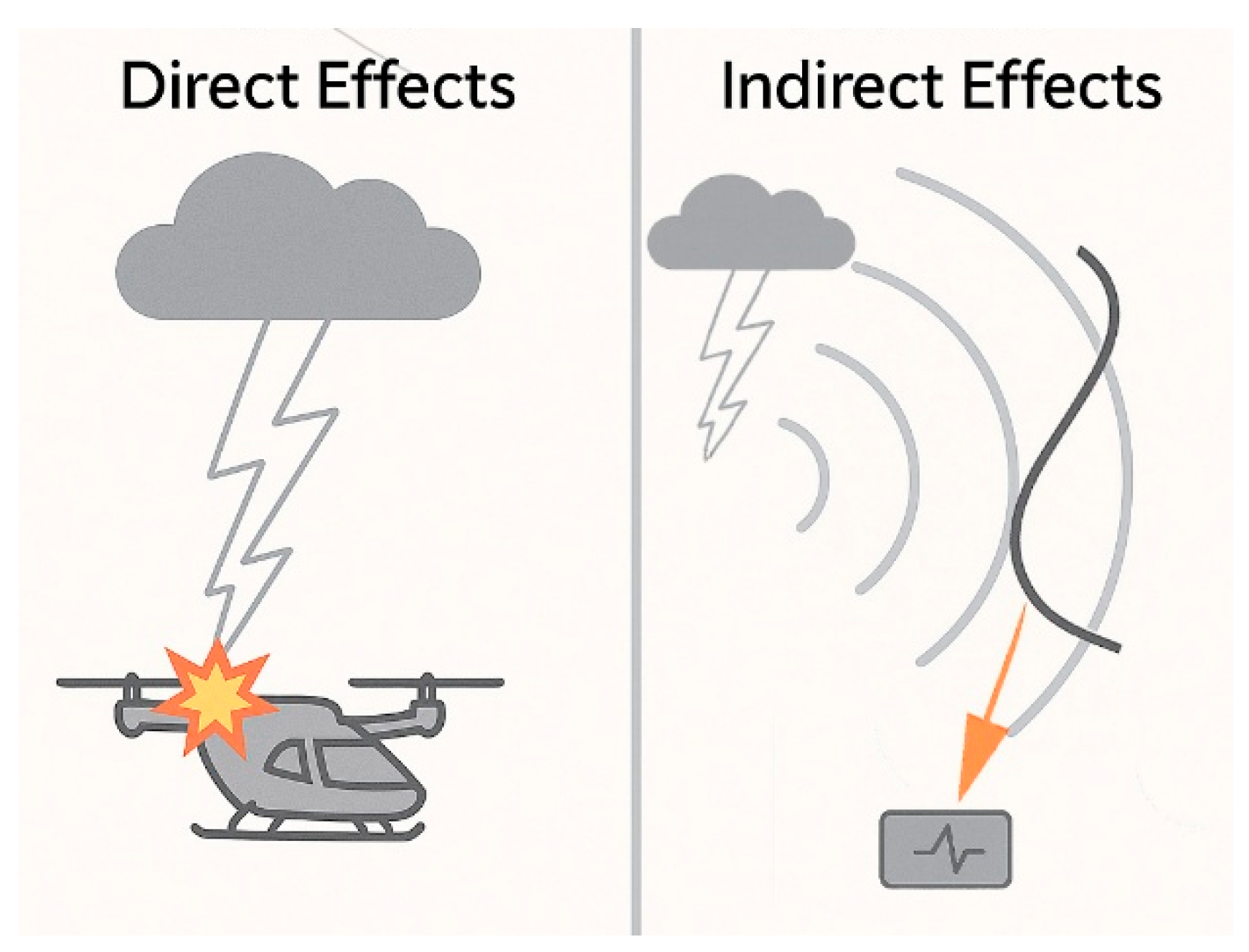

- Direct and Indirect Effects of Lightning

2.3. Lightning Coupling Methods

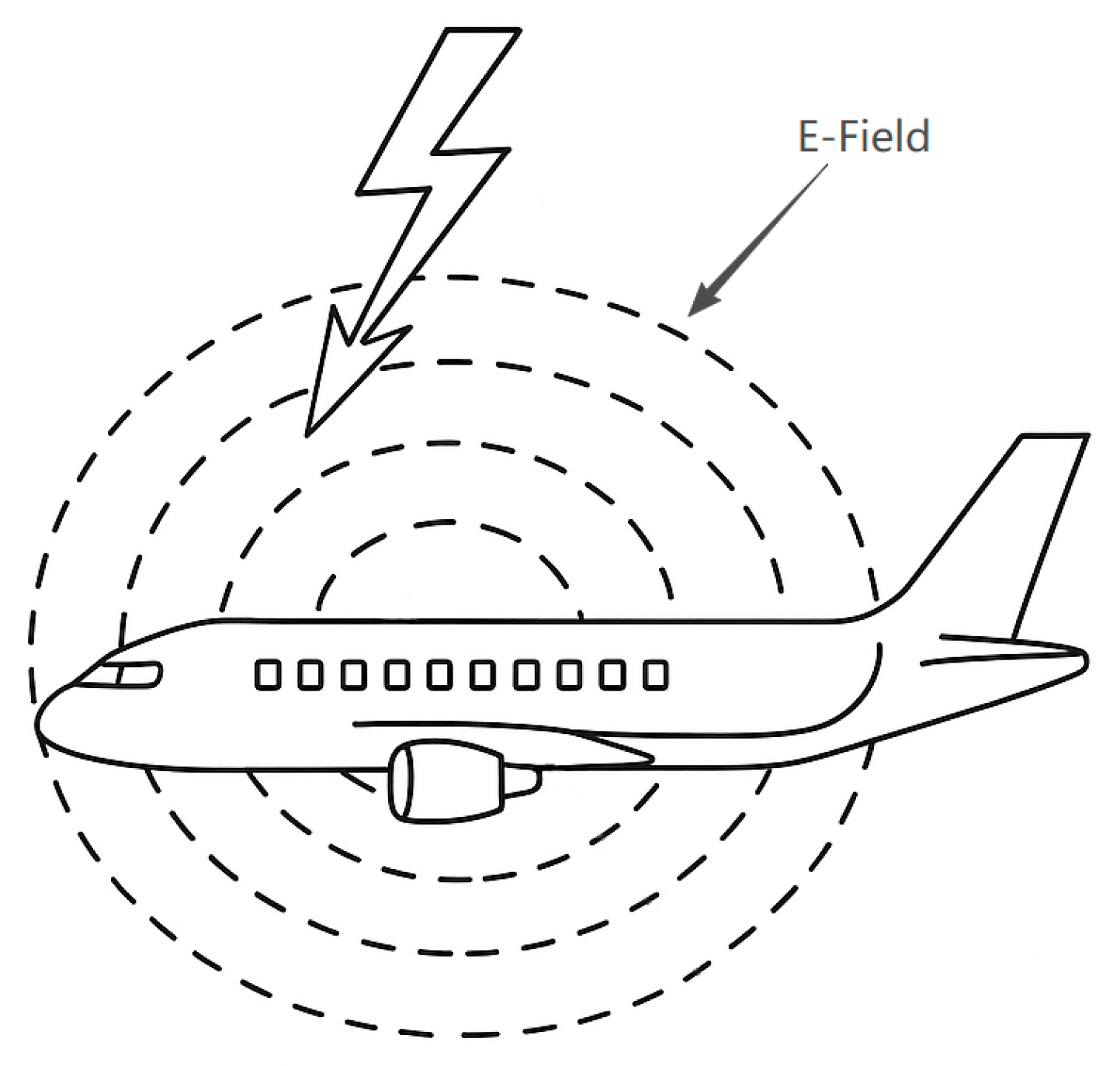

- Electrostatic Coupling

- 2

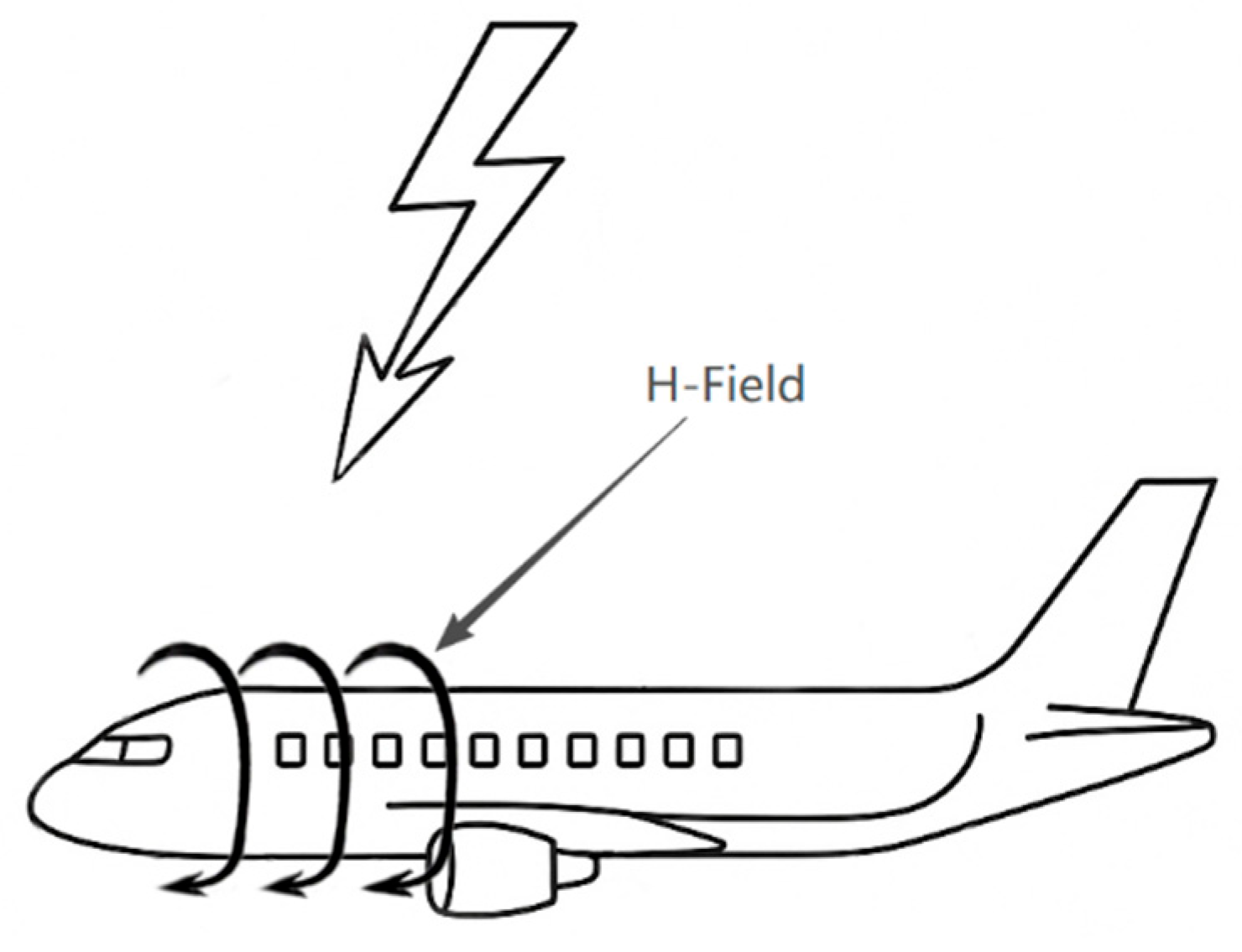

- Magnetic Coupling

- 3

- Resistive Coupling

2.4. Lightning Protection Standards for eVTOL

- Aircraft Level Requirements

- 2

- Equipment Level Requirements

3. Simulation Model and Excitation Setup

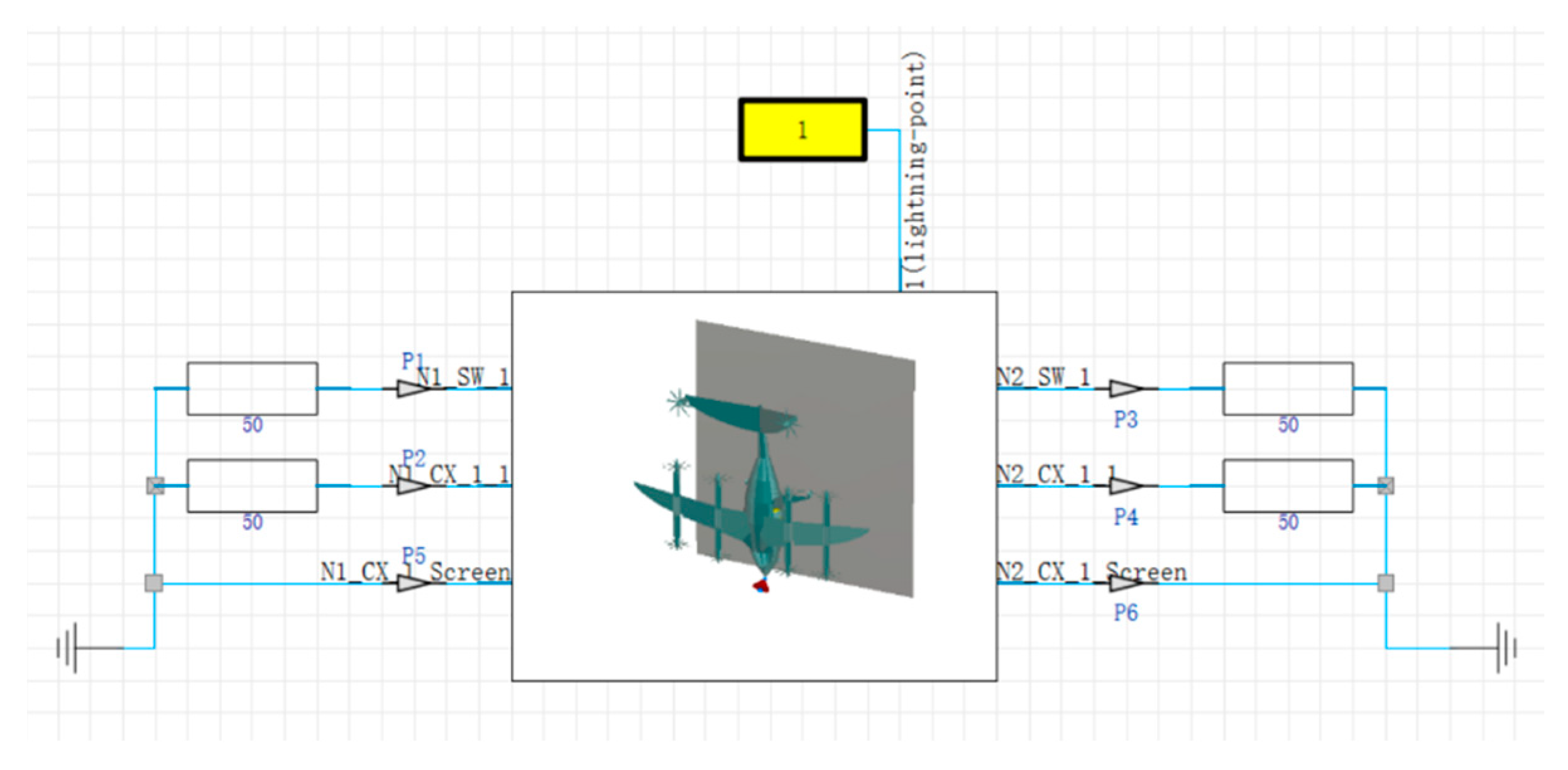

3.1. Introduction to CST and Cable Studio

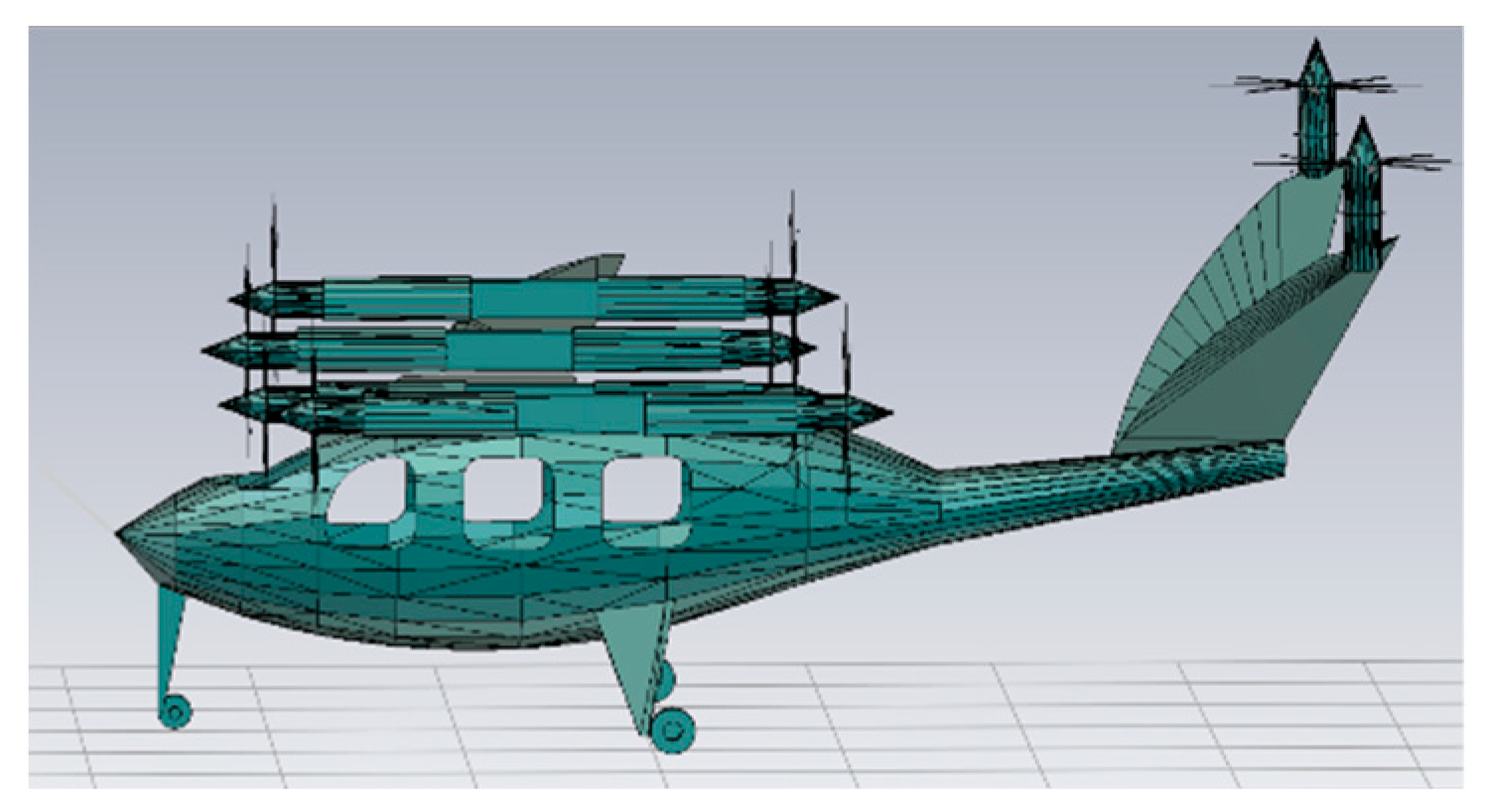

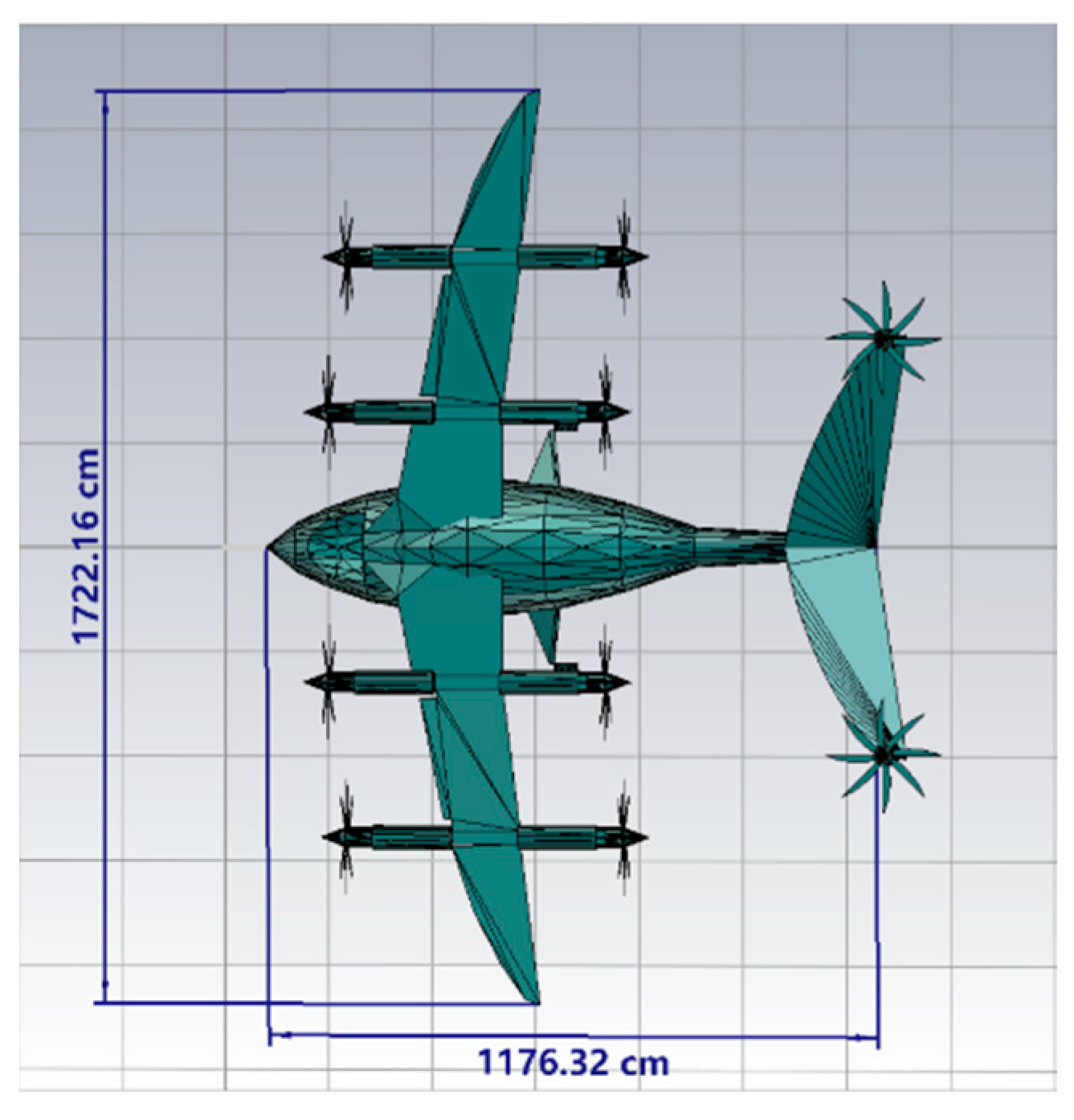

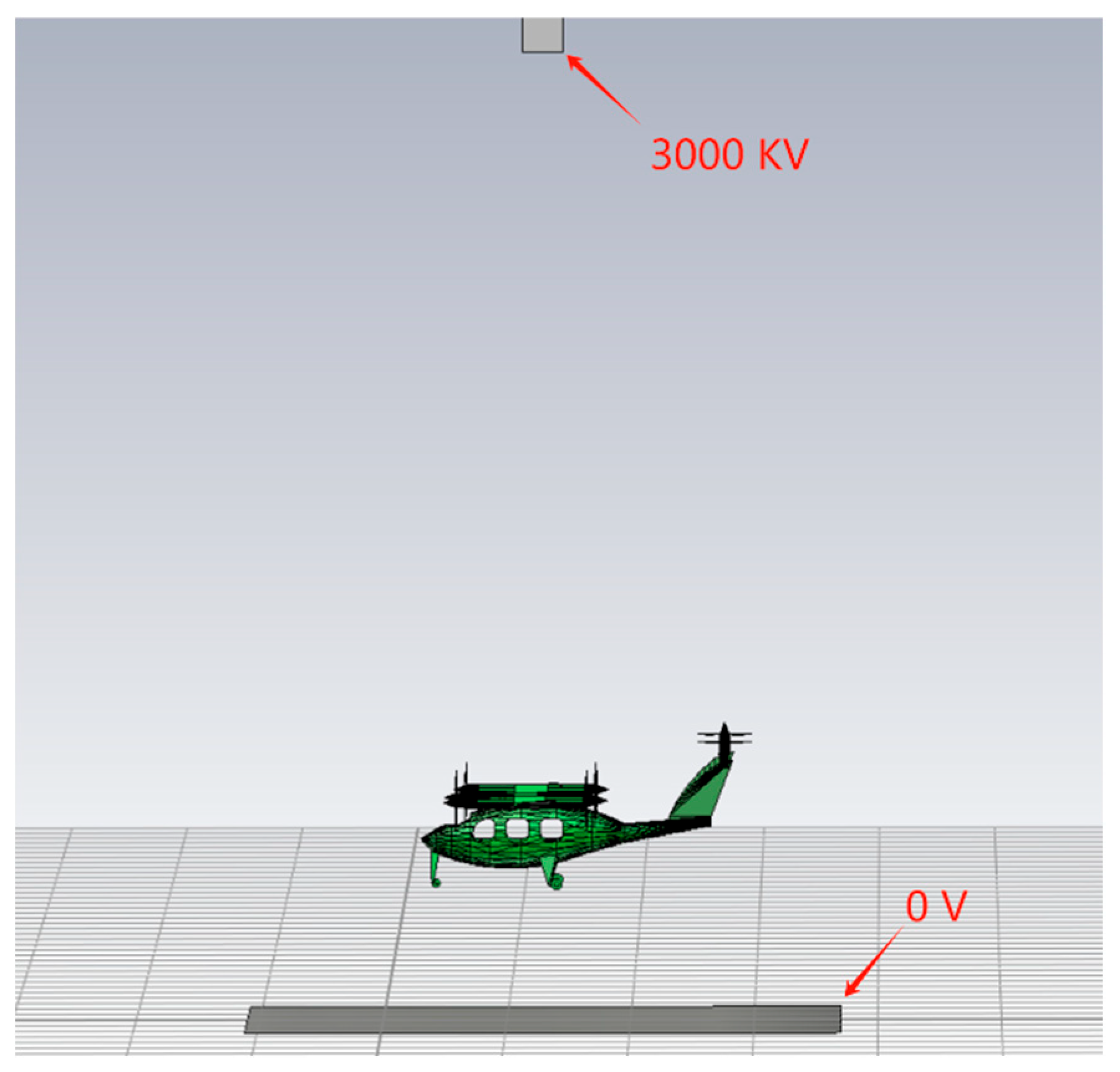

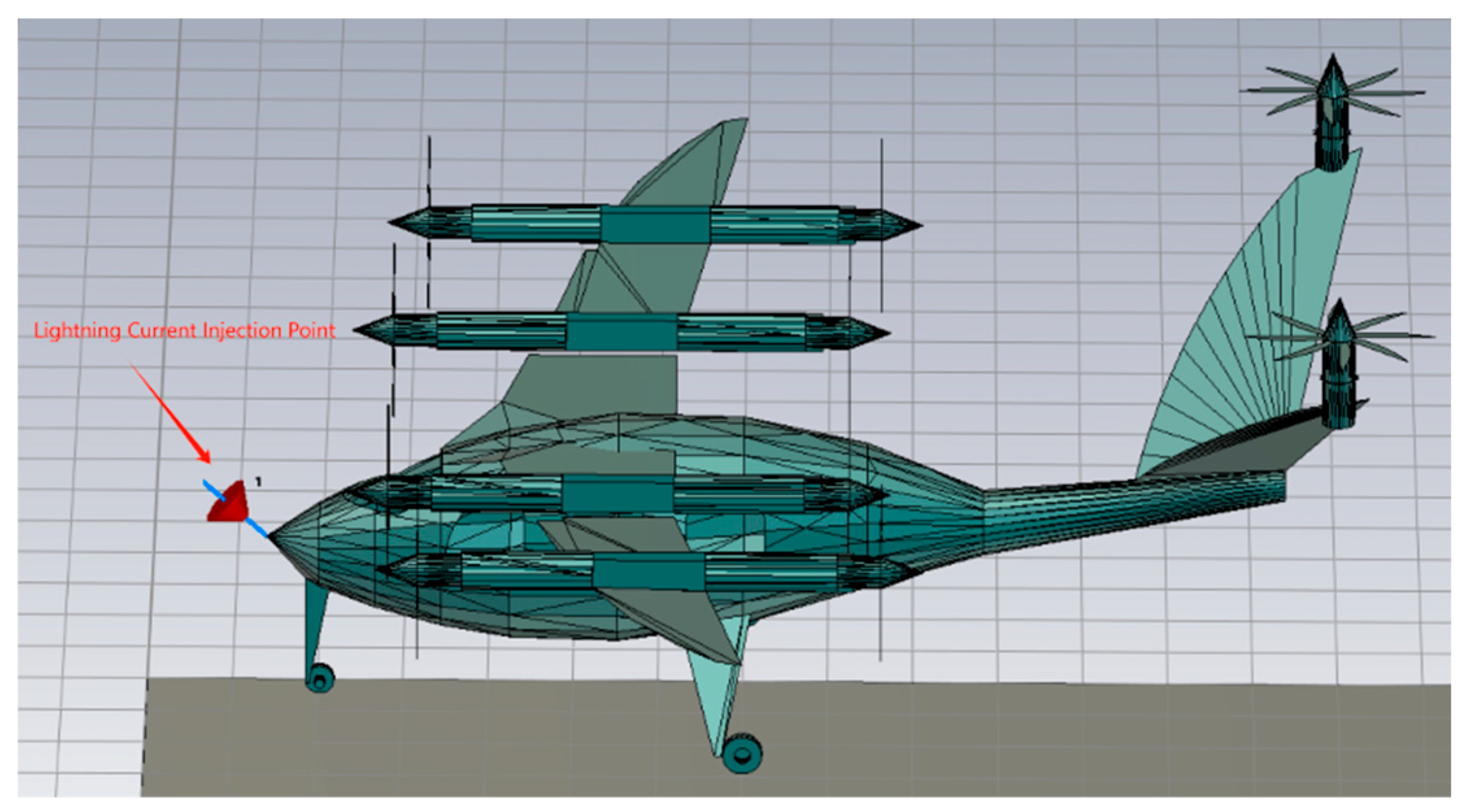

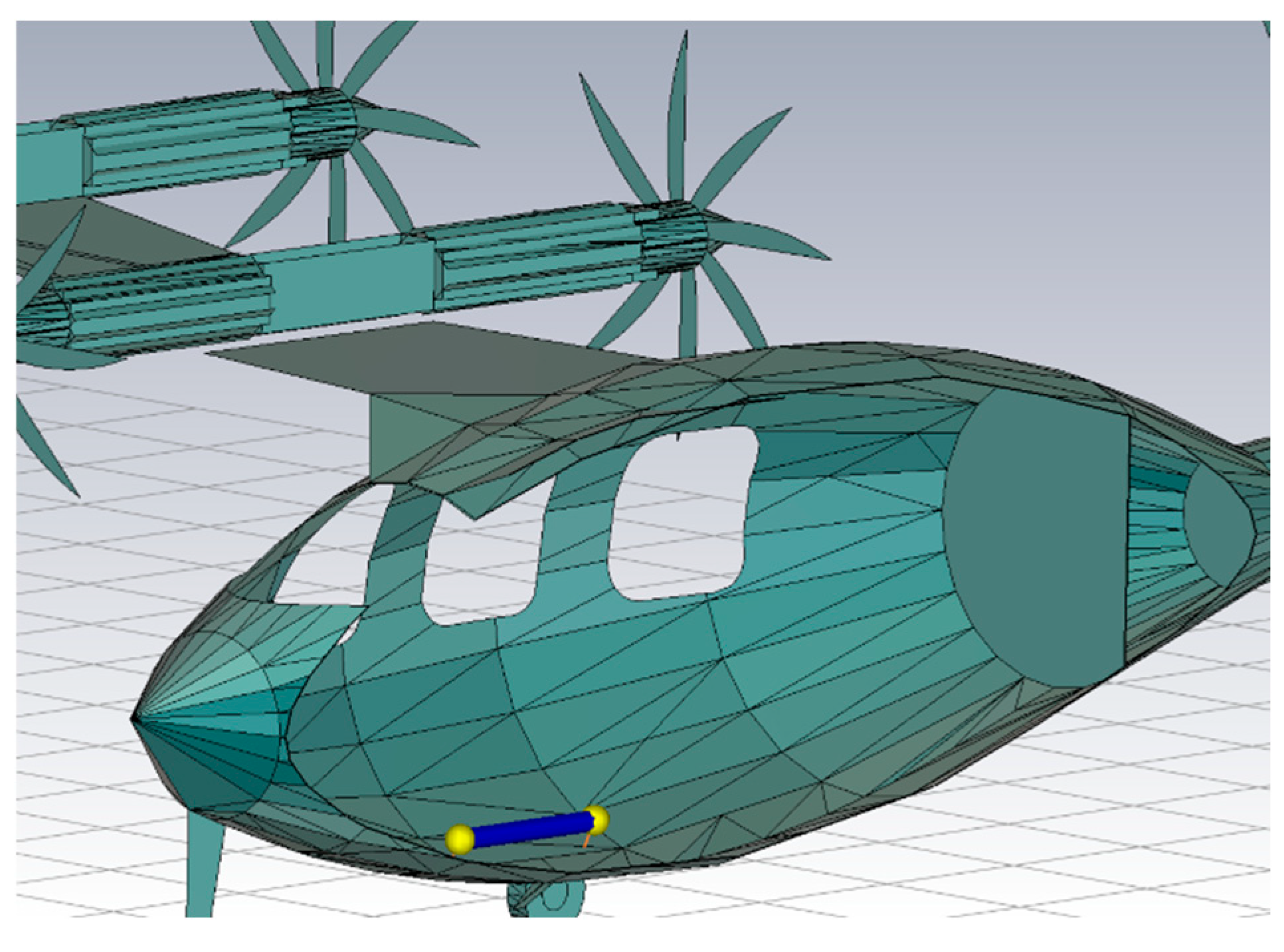

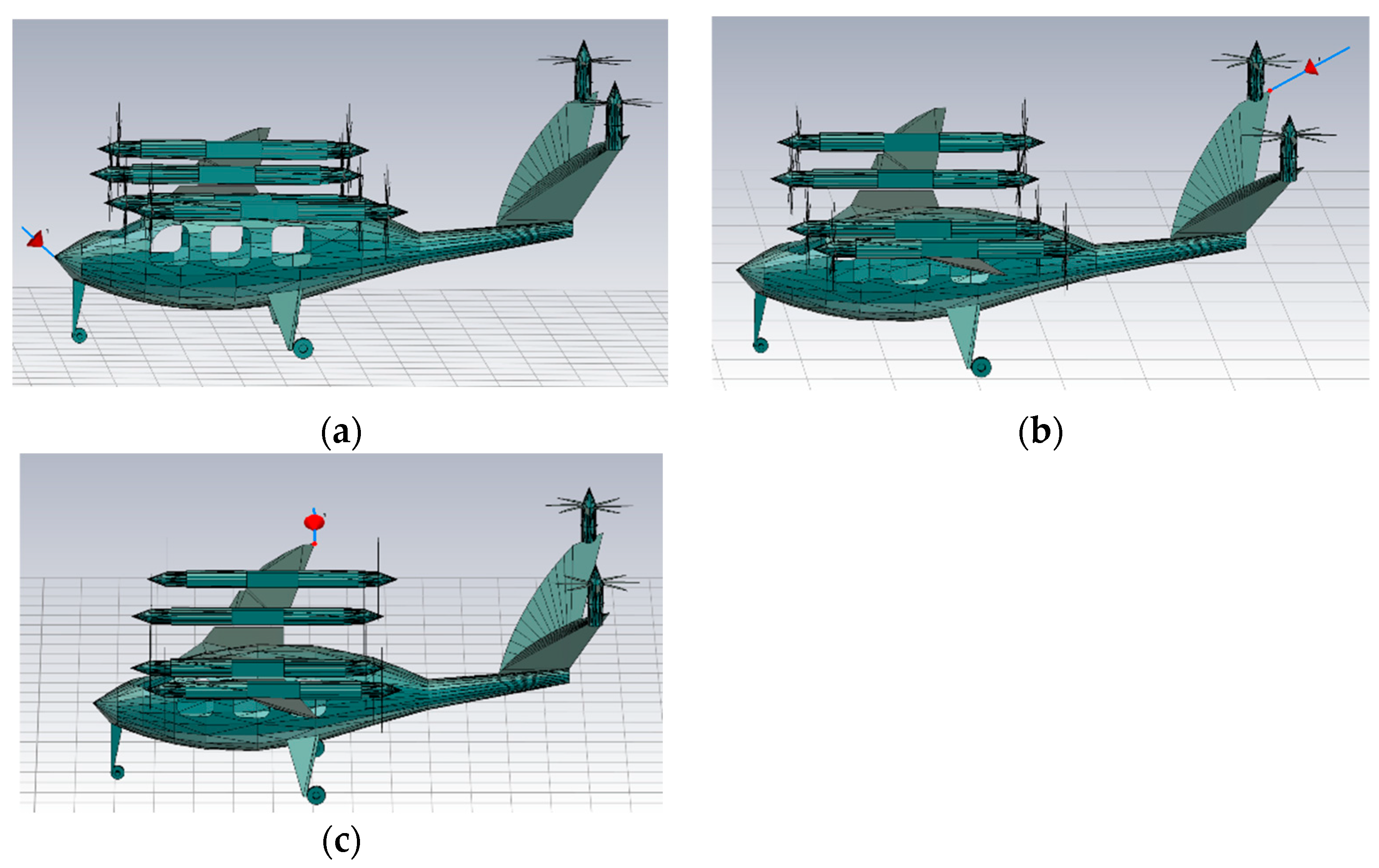

3.2. eVTOL Model Setup

3.3. Lightning Zoning

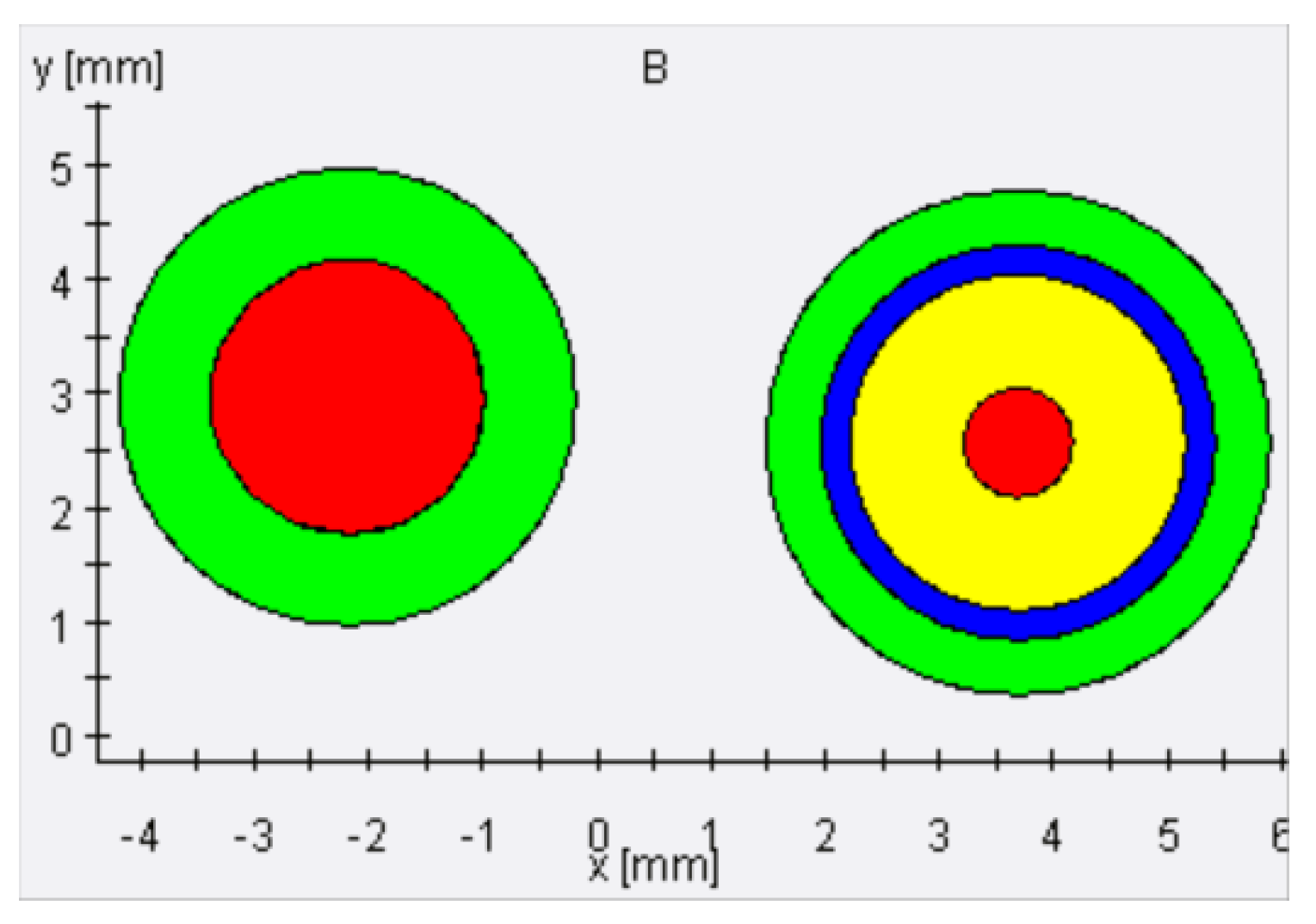

3.3.1. Introduction to Lightning Zoning

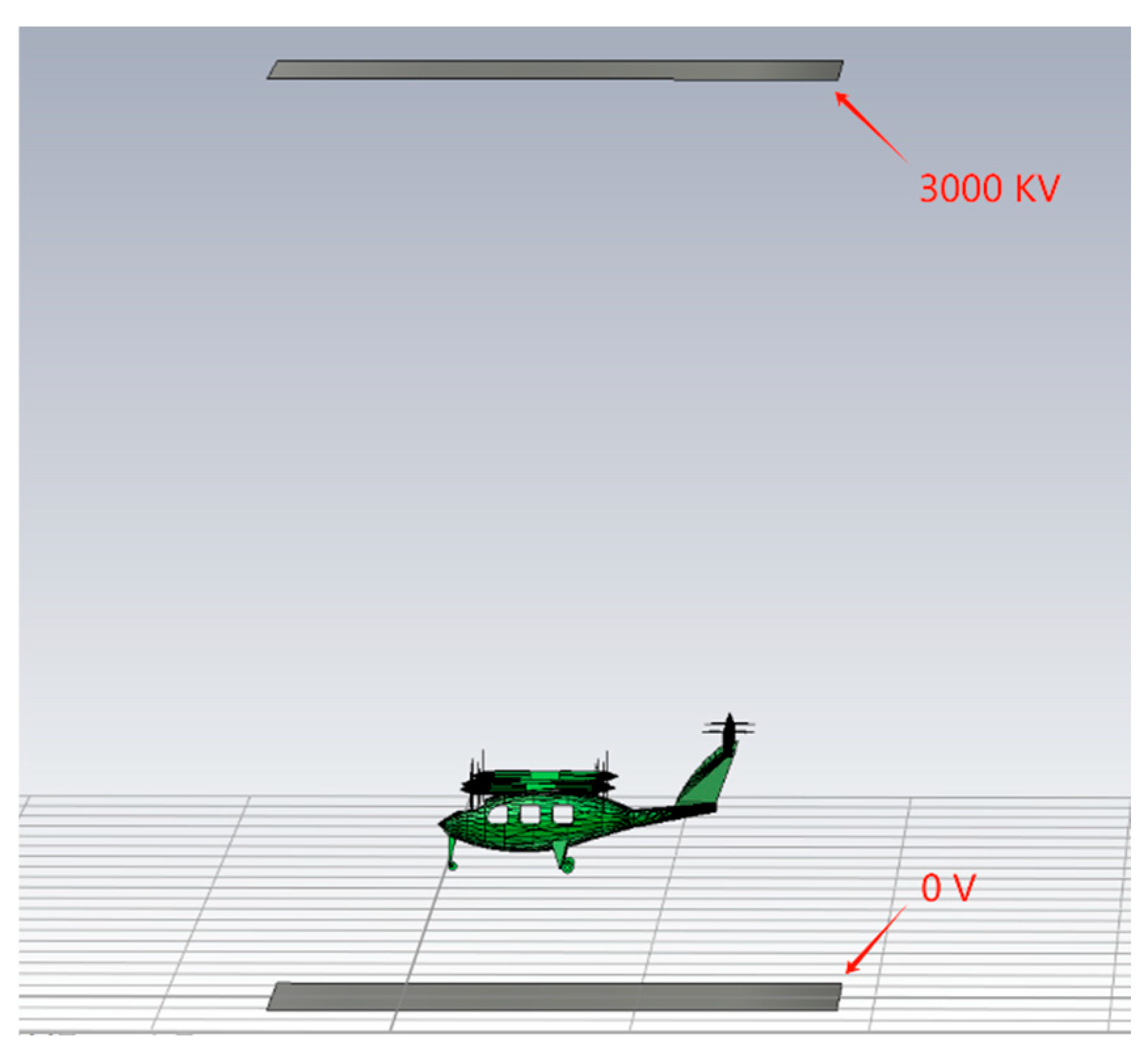

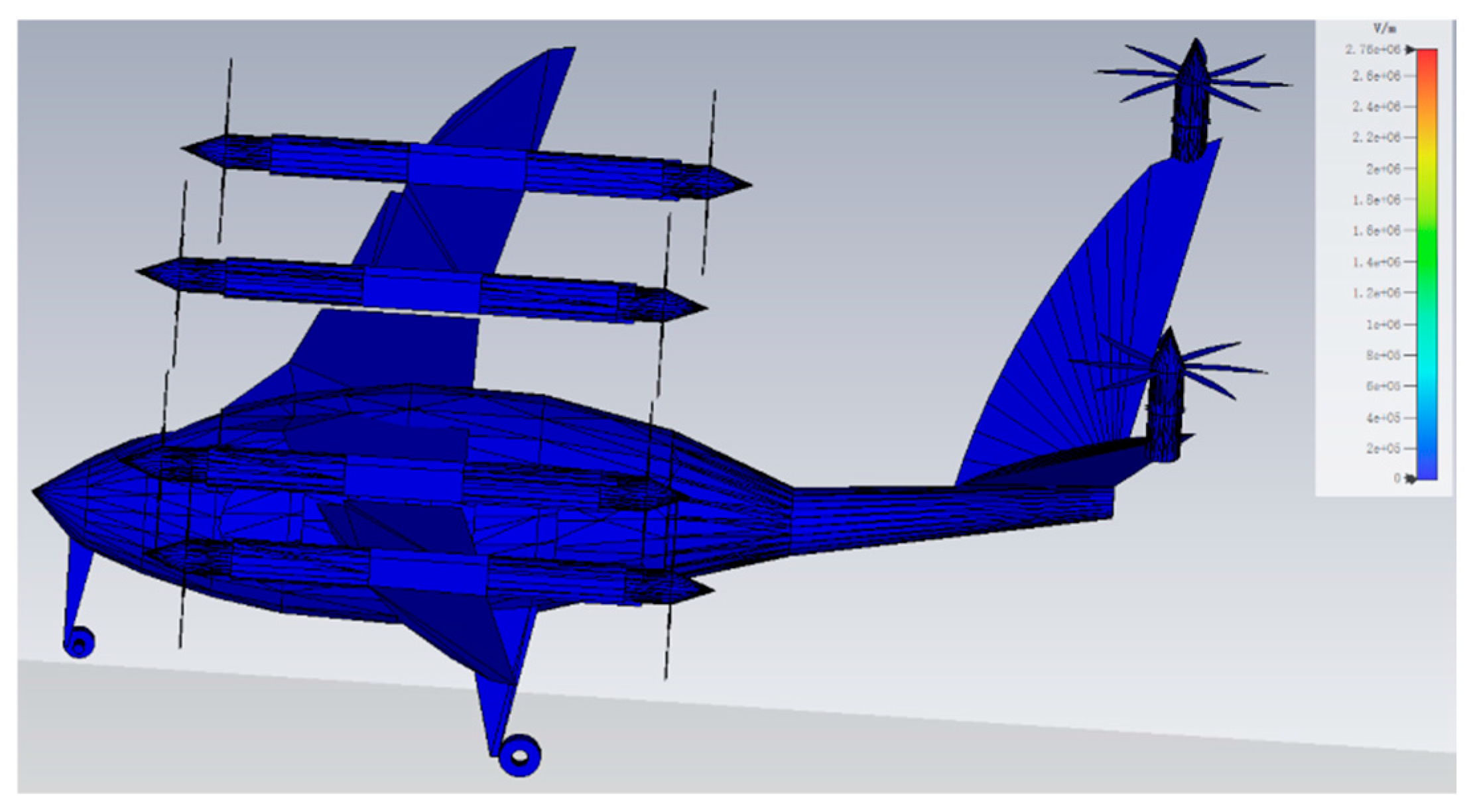

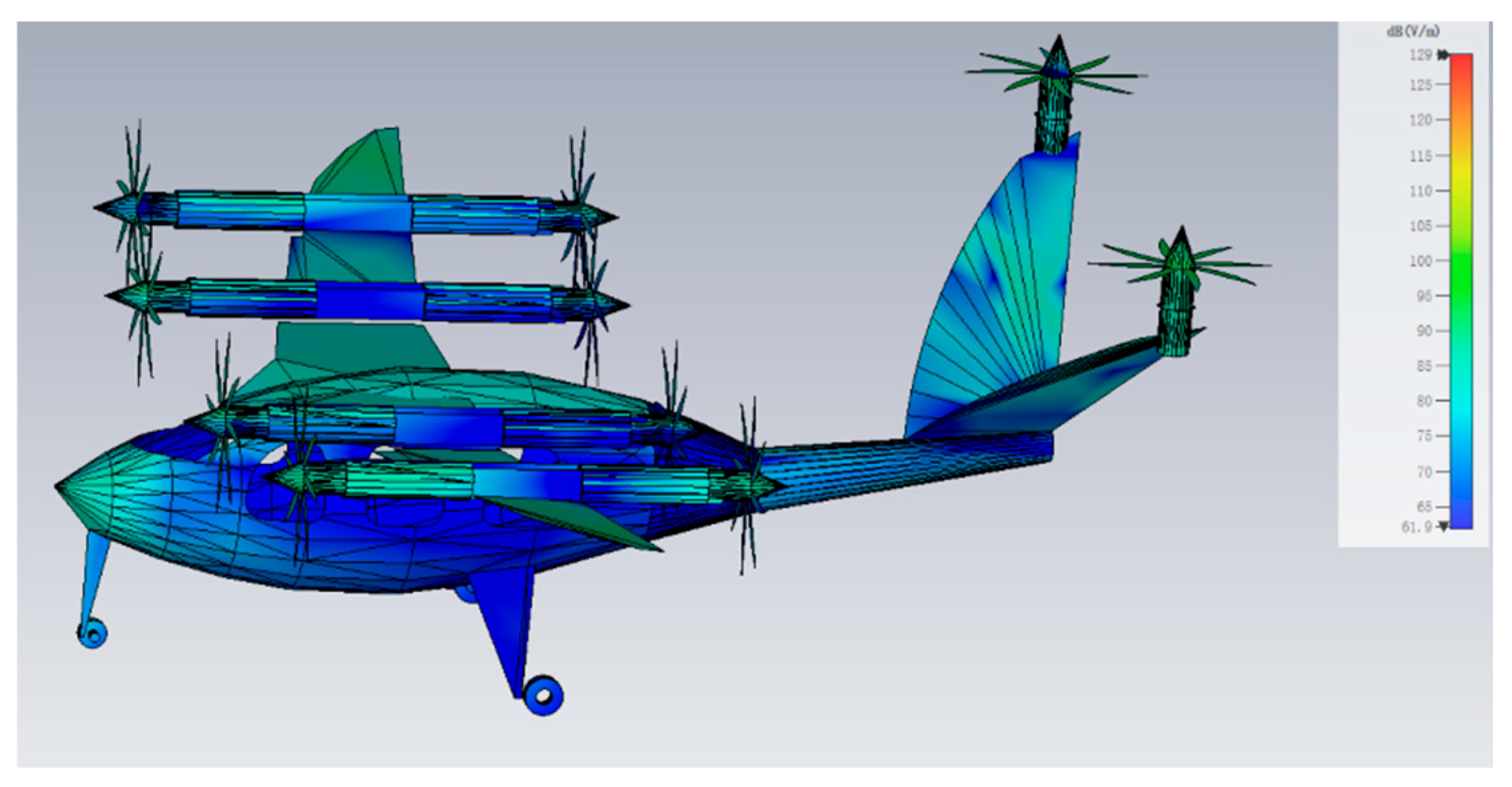

3.3.2. Lightning Zoning Simulation

- Flat Plate Electrode Model

- 2

- Rod-shaped Electrode Model

- 3

- Conclusion and Analysis

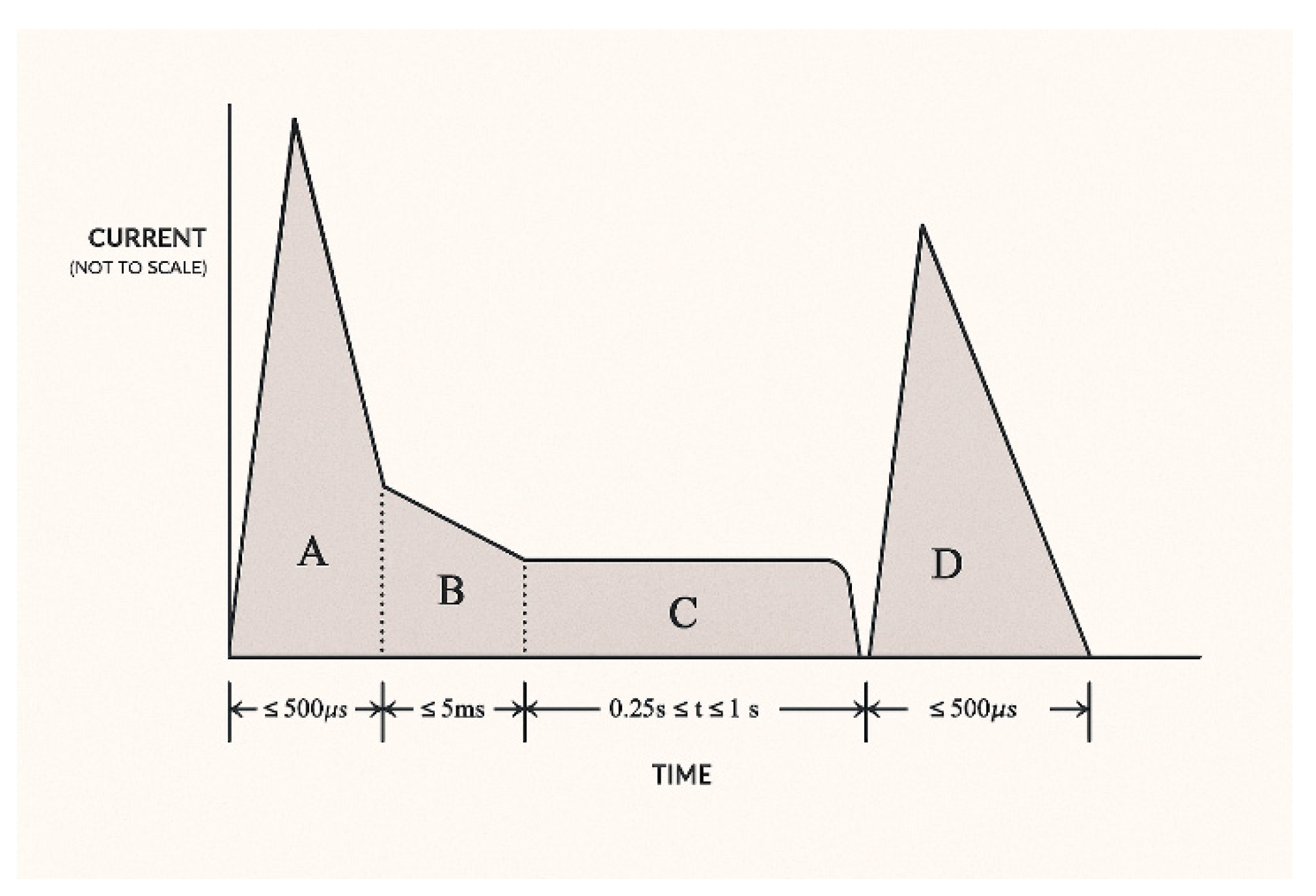

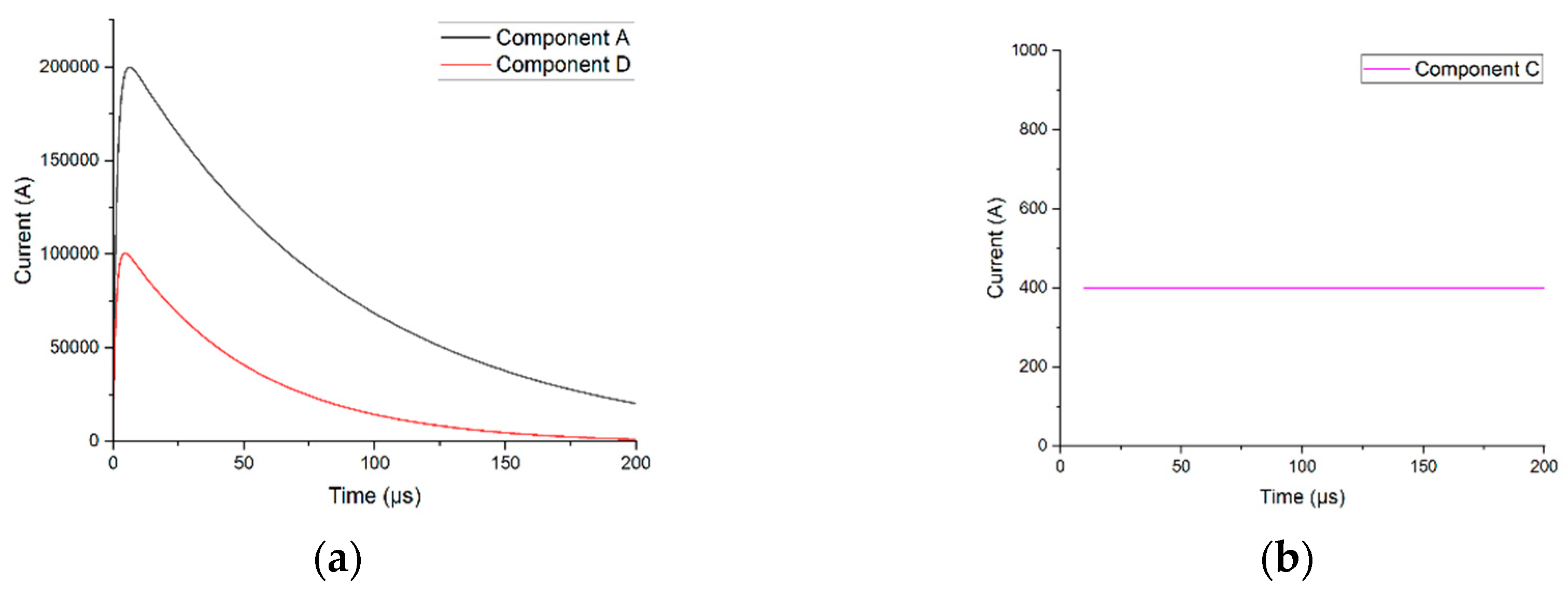

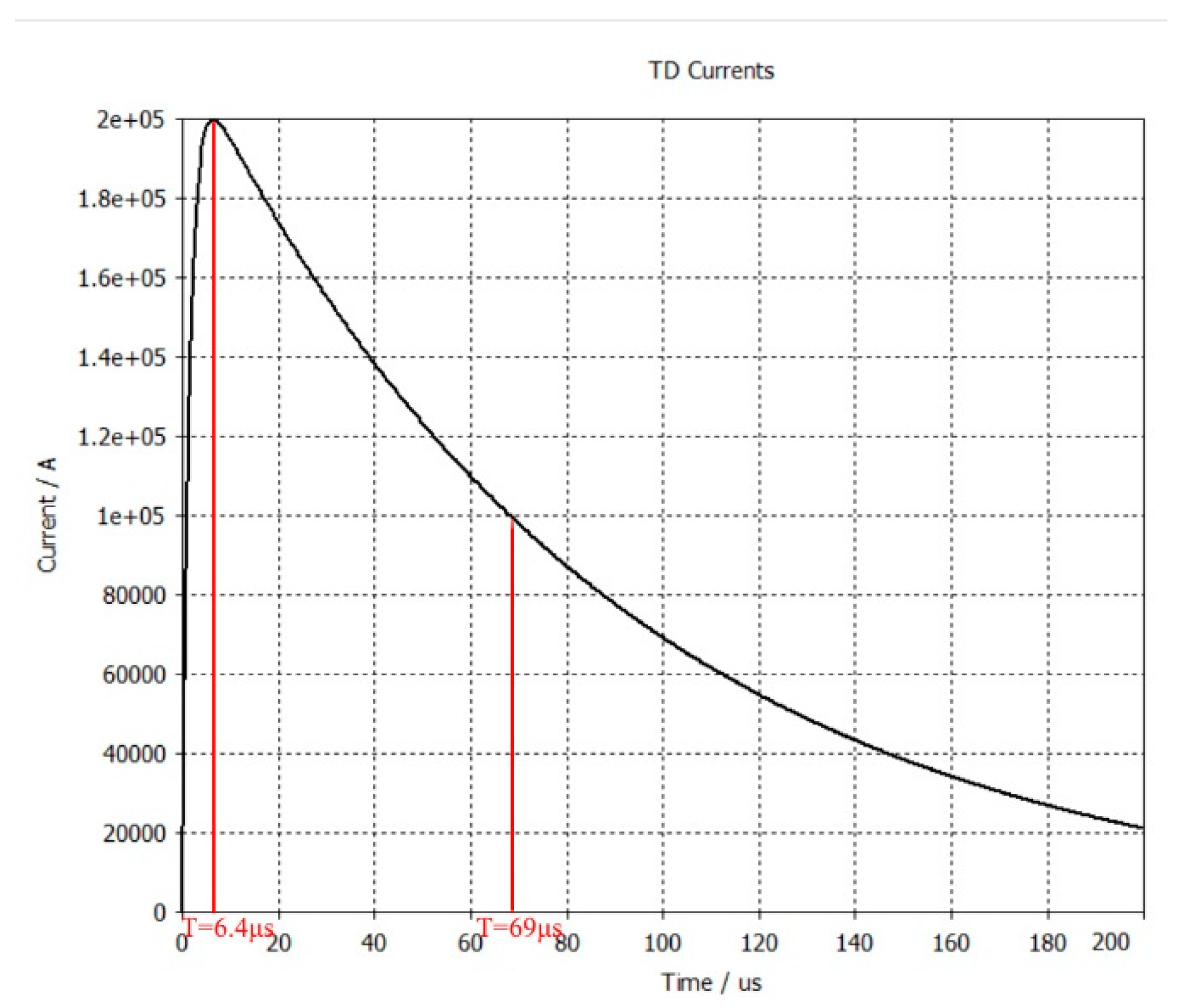

3.4. Lightning Excitation Study

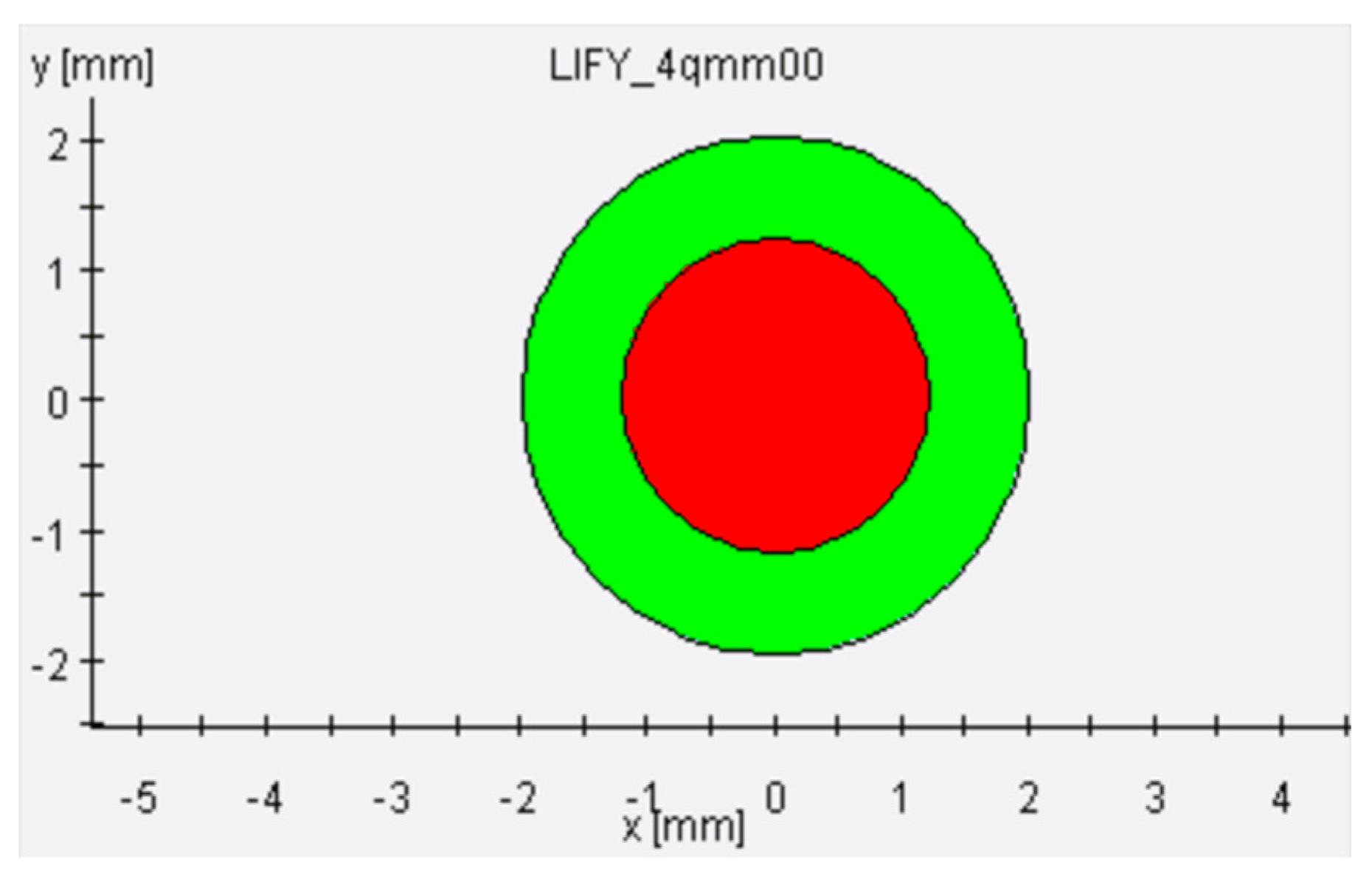

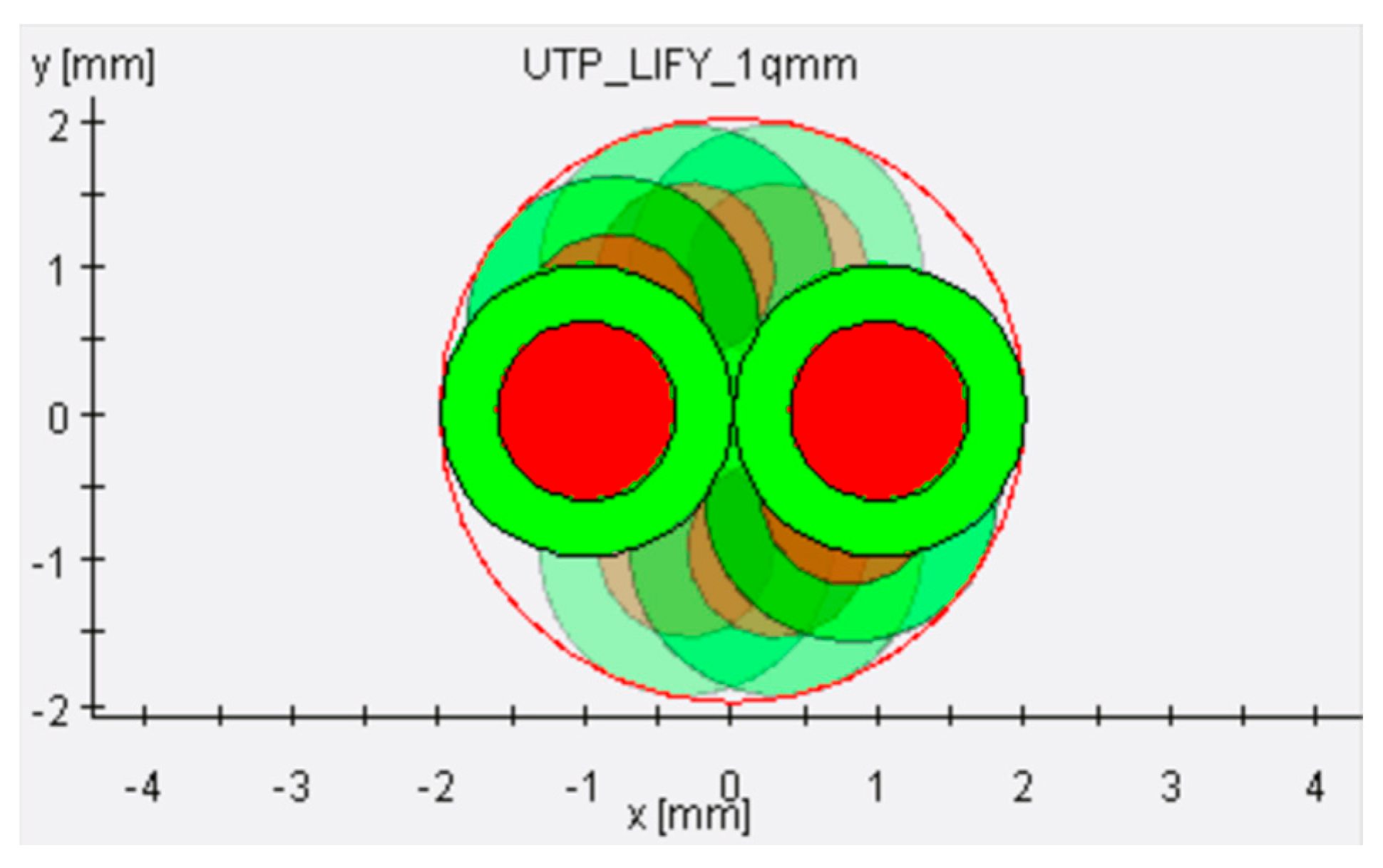

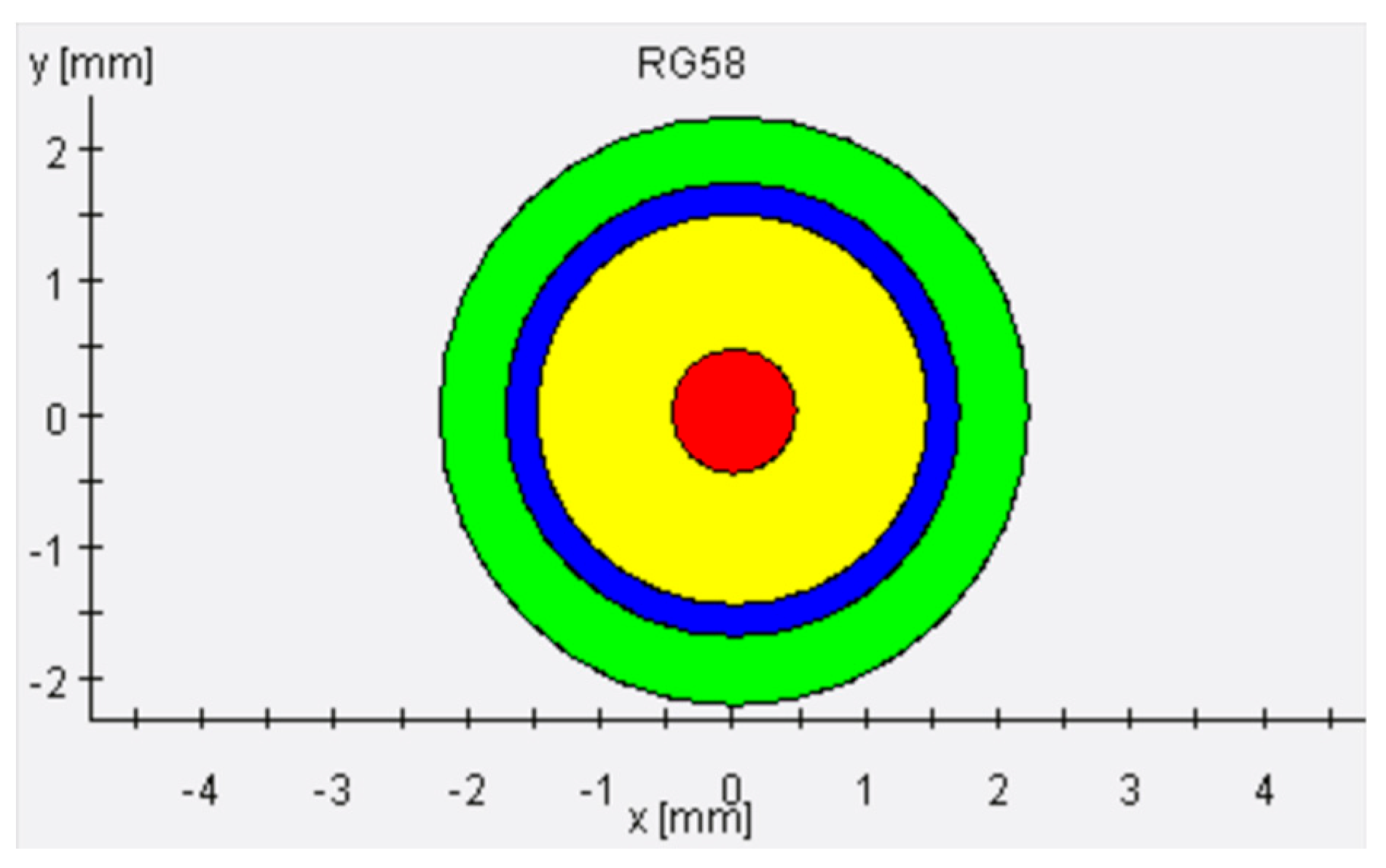

3.5. Cable Setup

4. Electromagnetic Response Analysis of the Aircraft Under Lightning

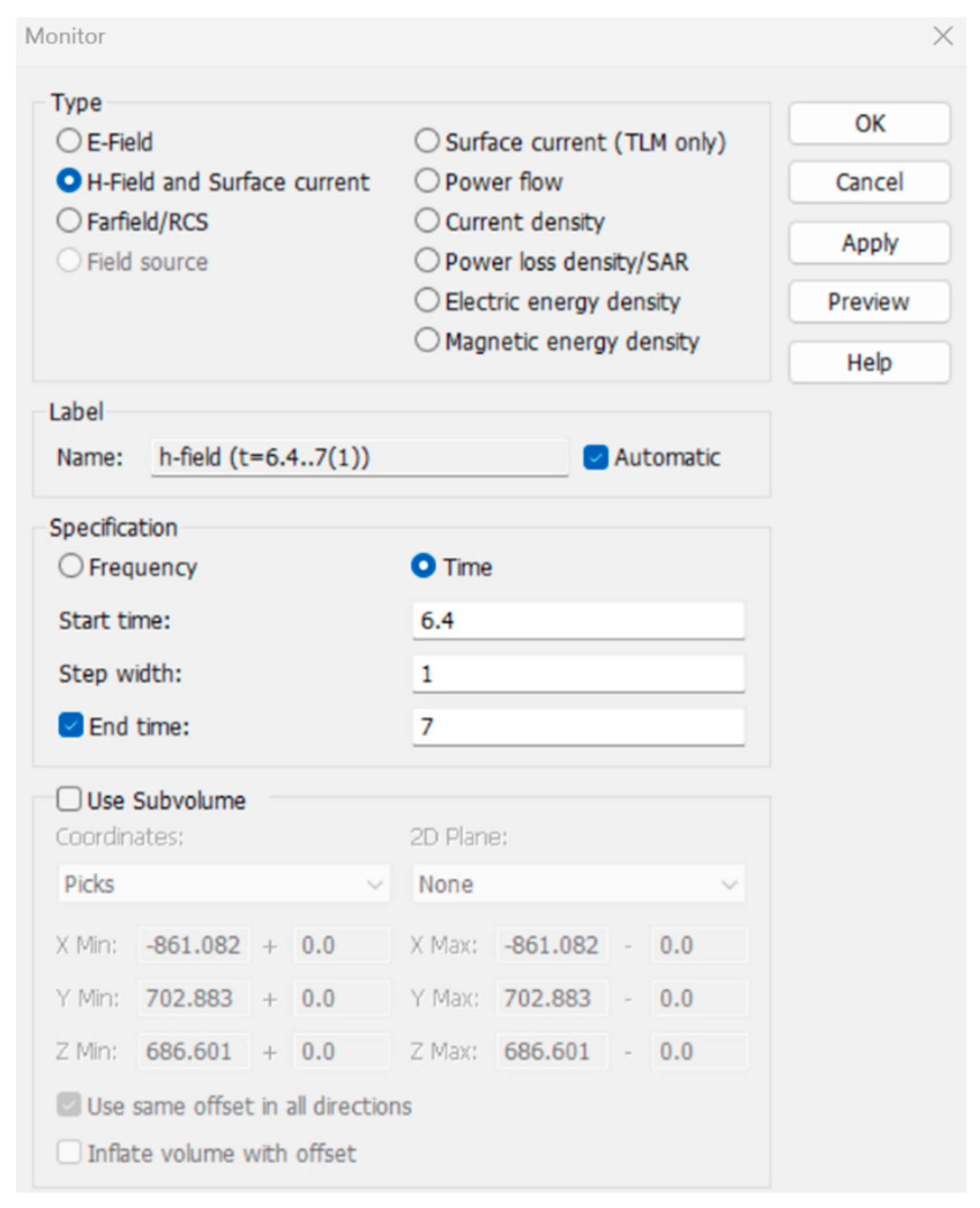

4.1. Modeling and Simulation of Different Lightning Strike Locations

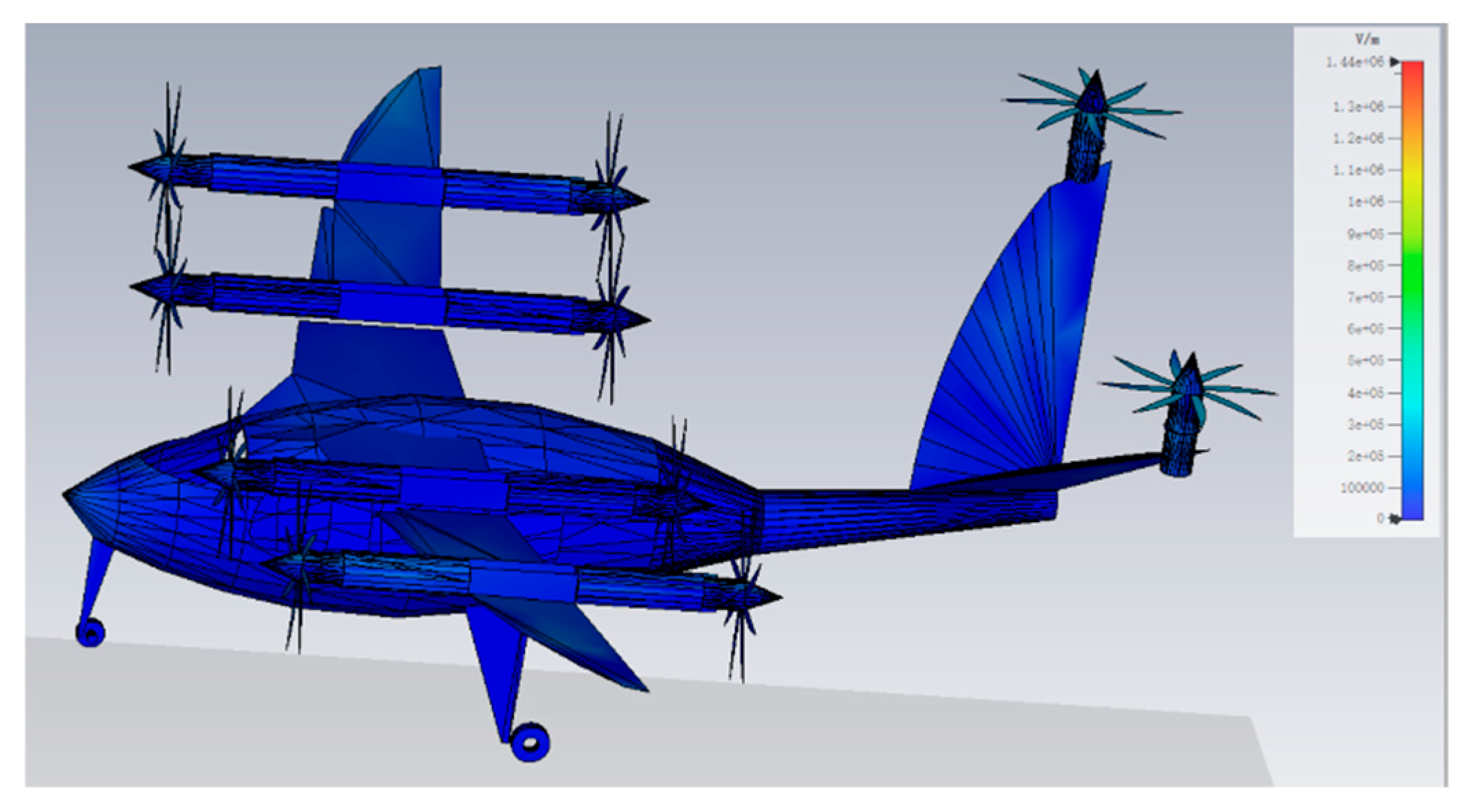

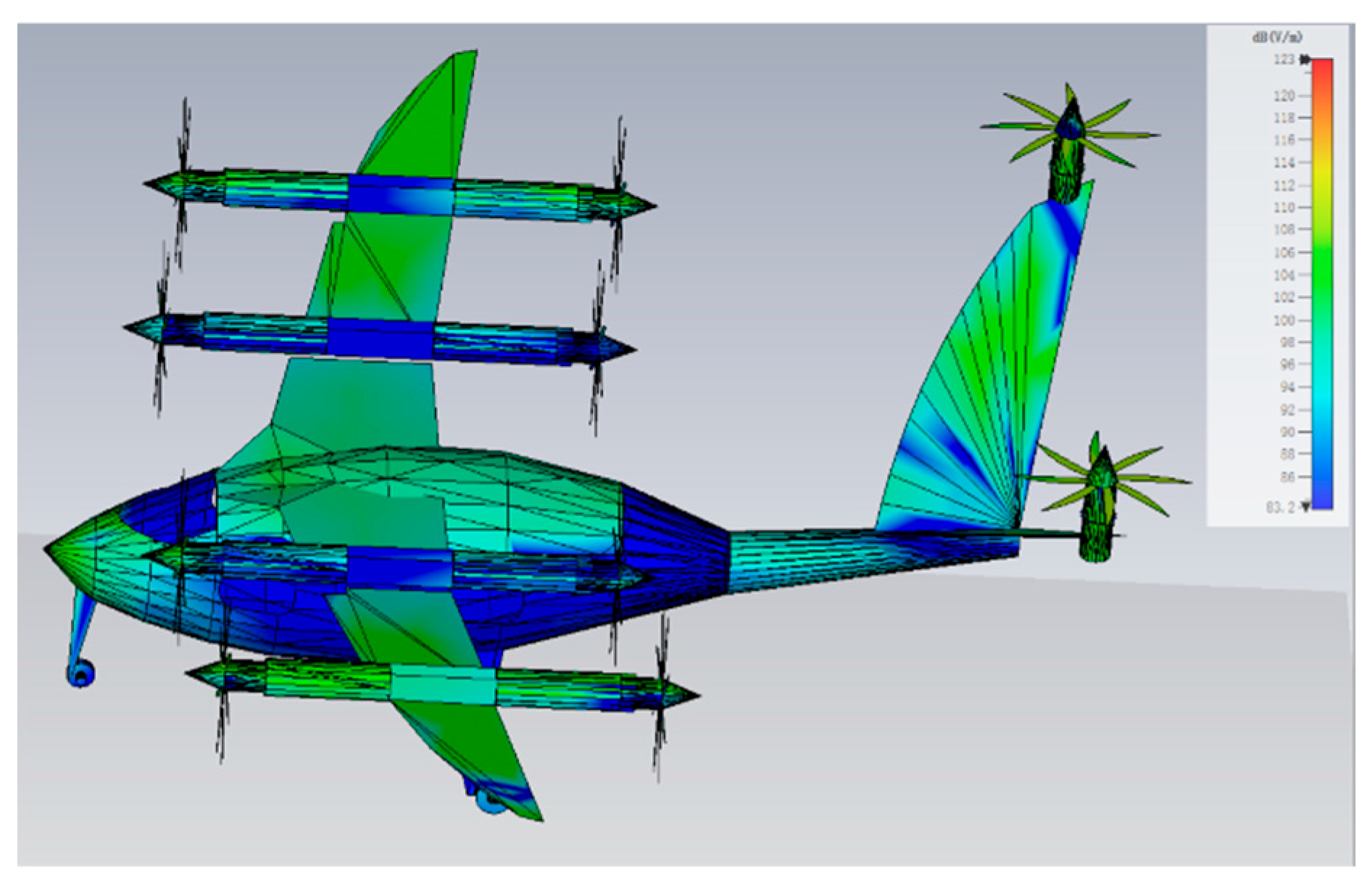

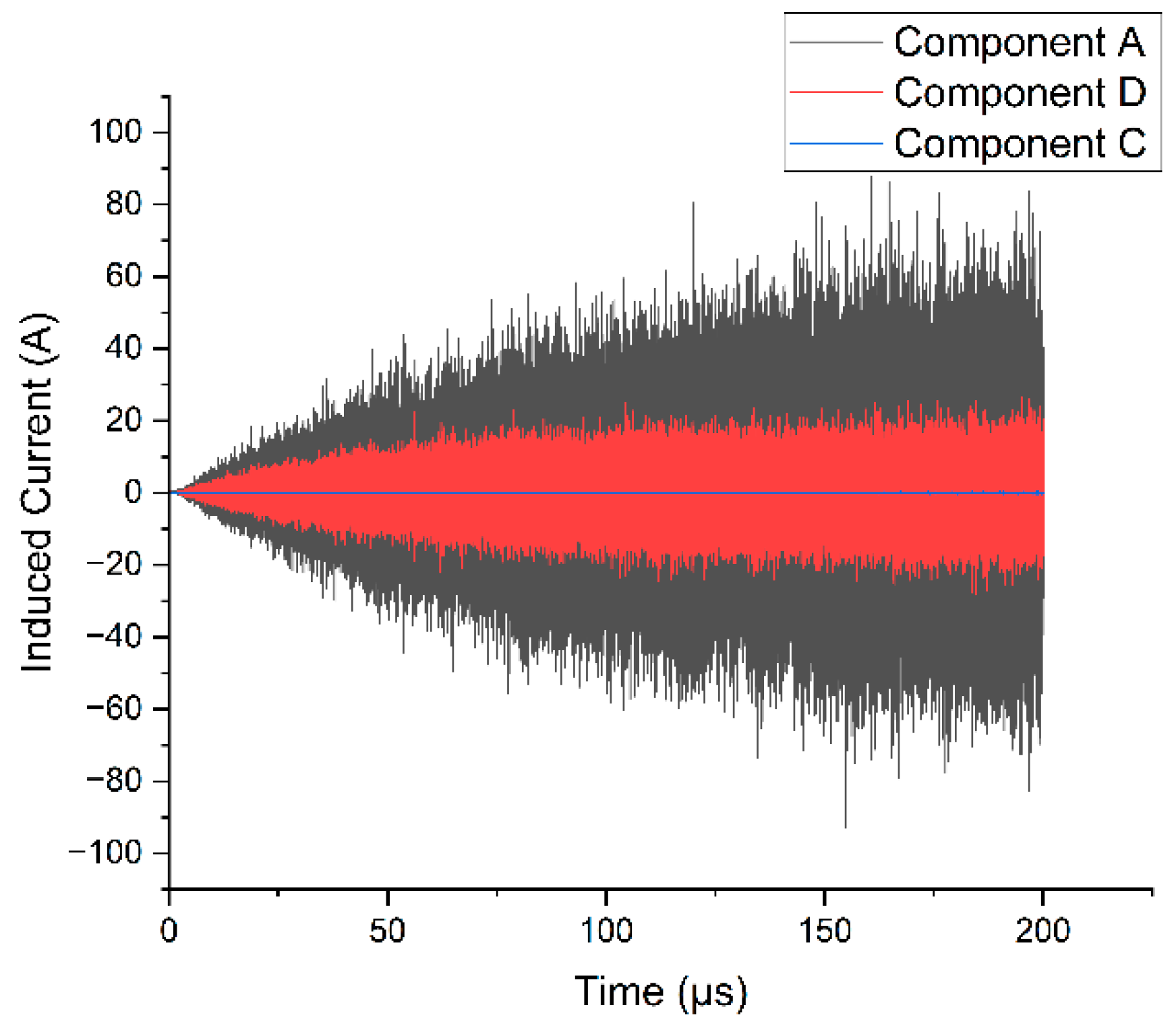

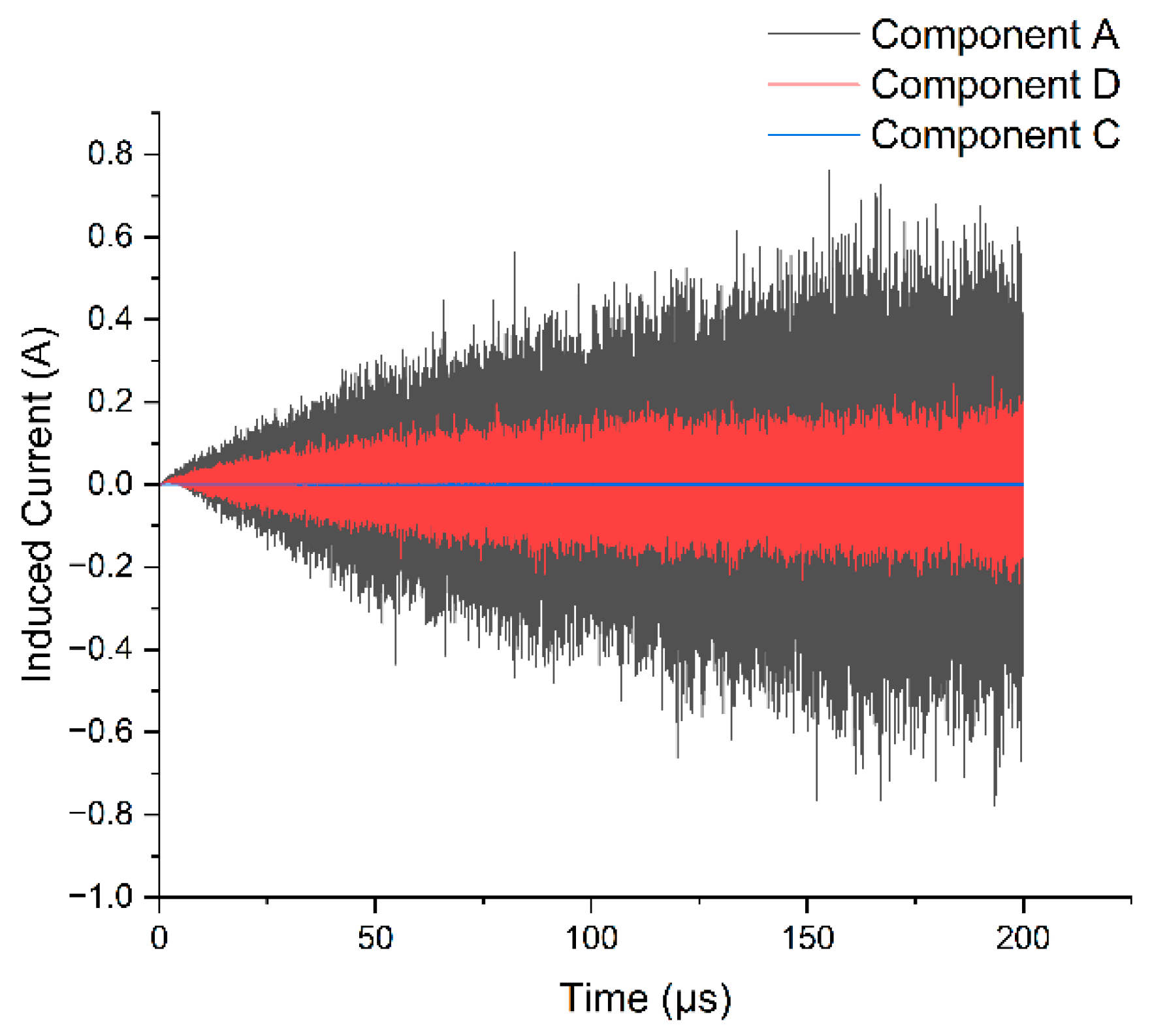

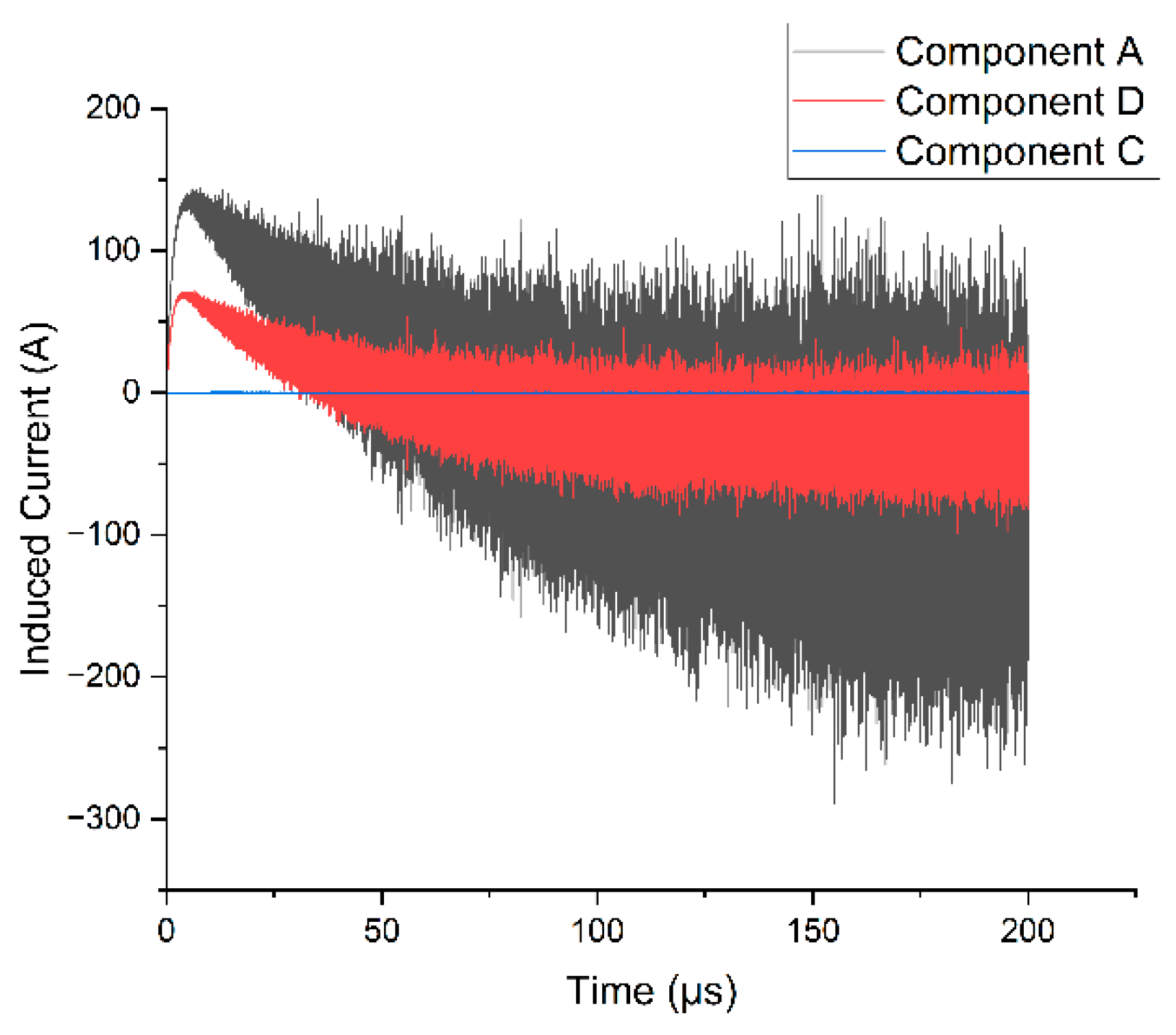

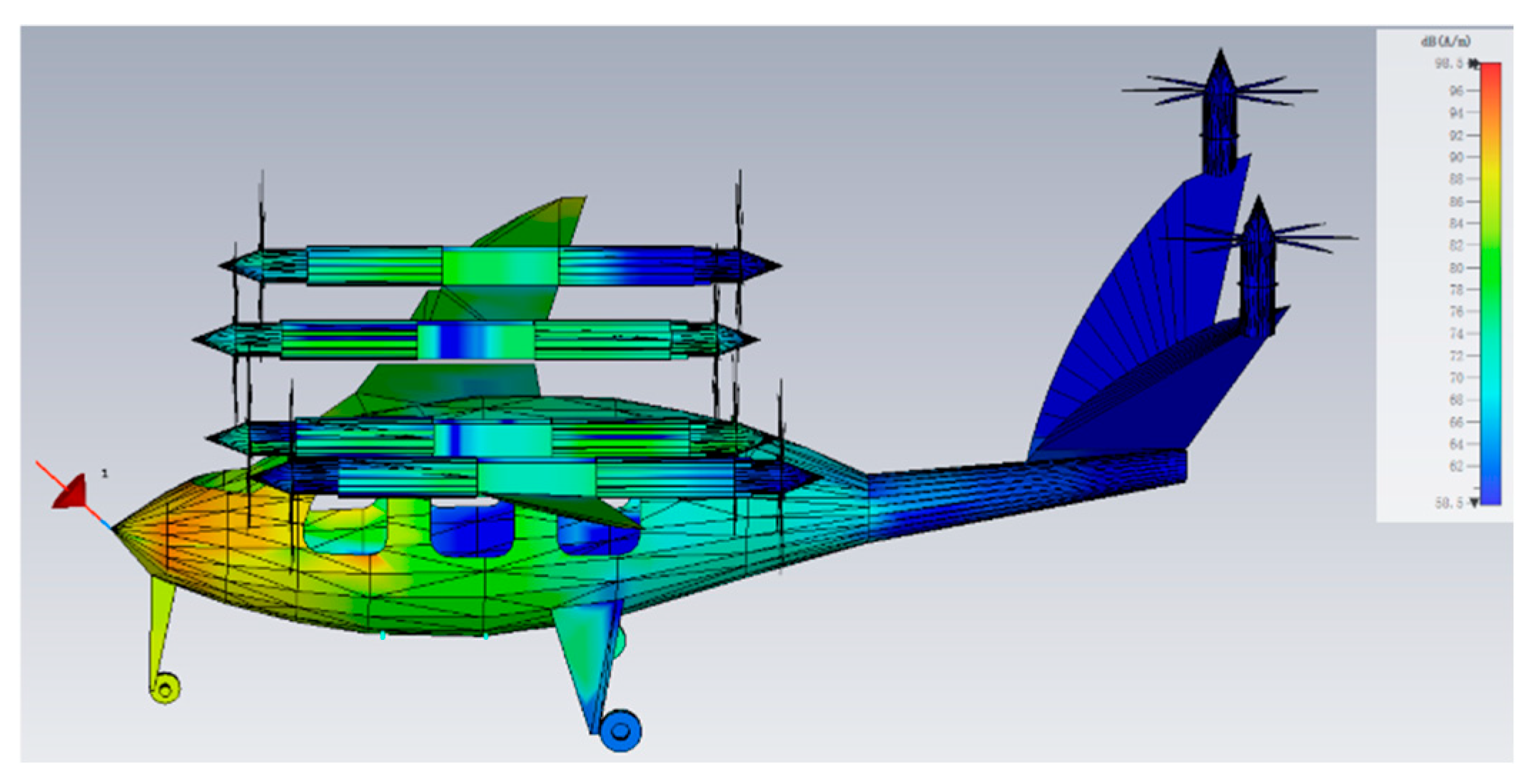

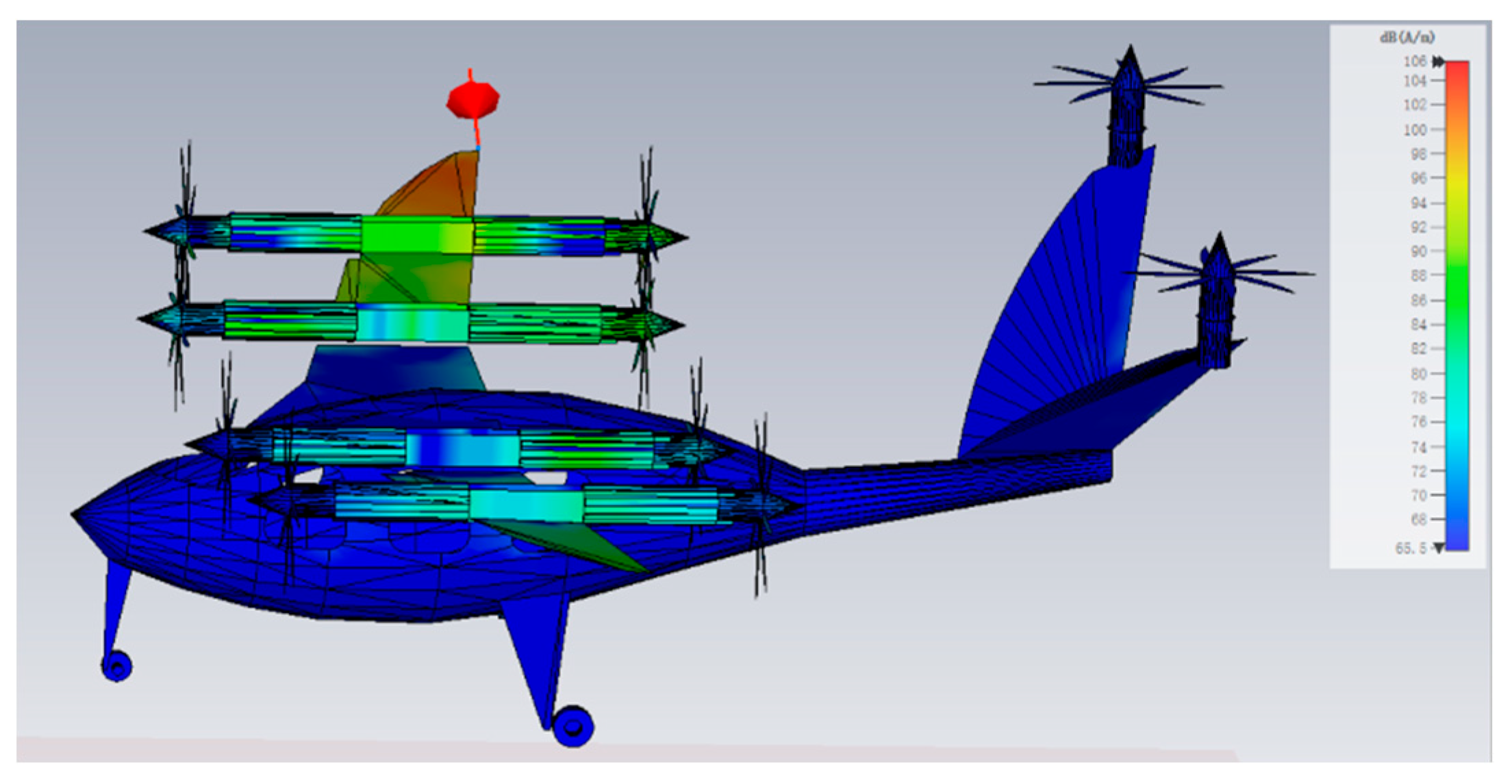

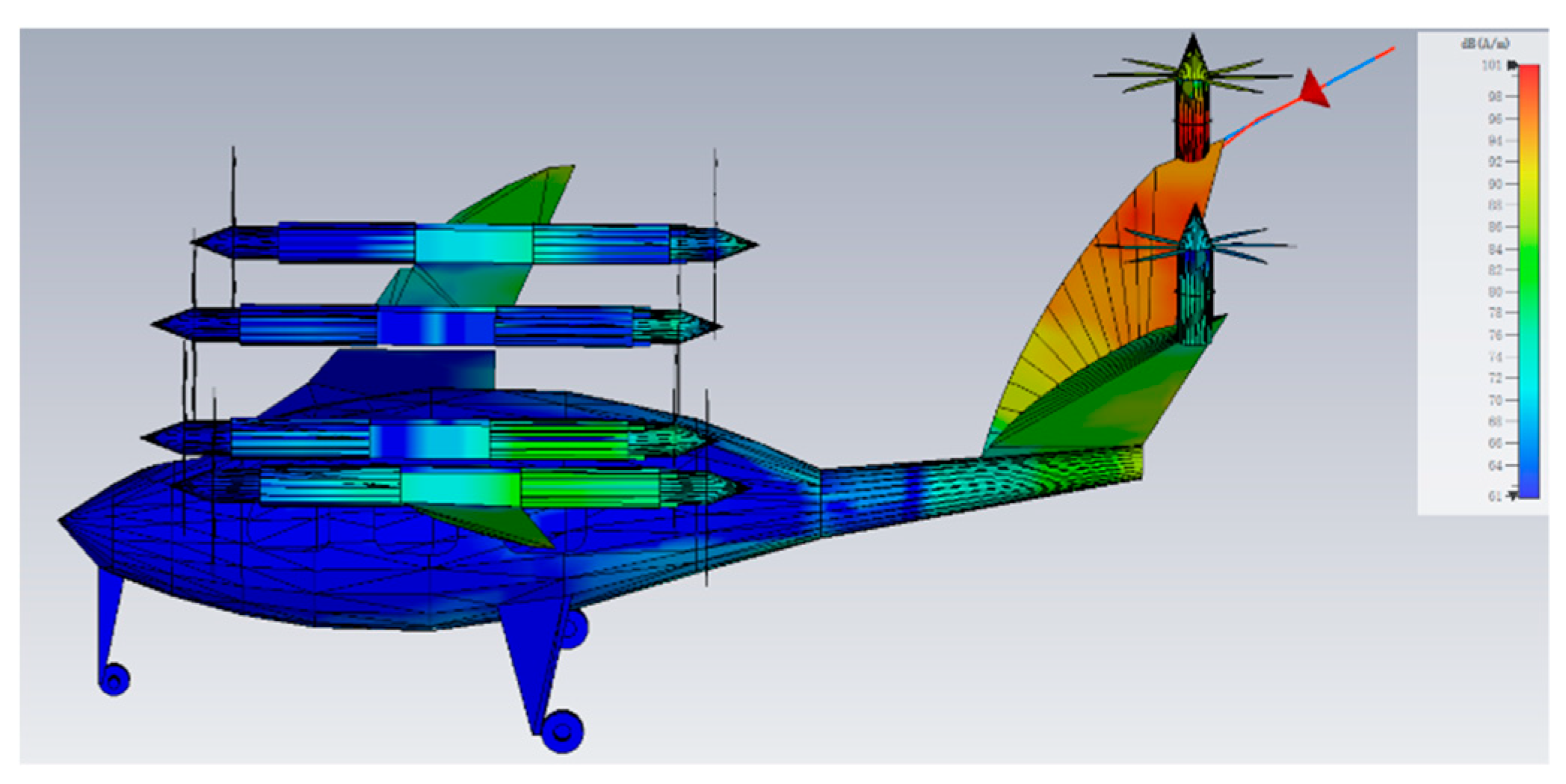

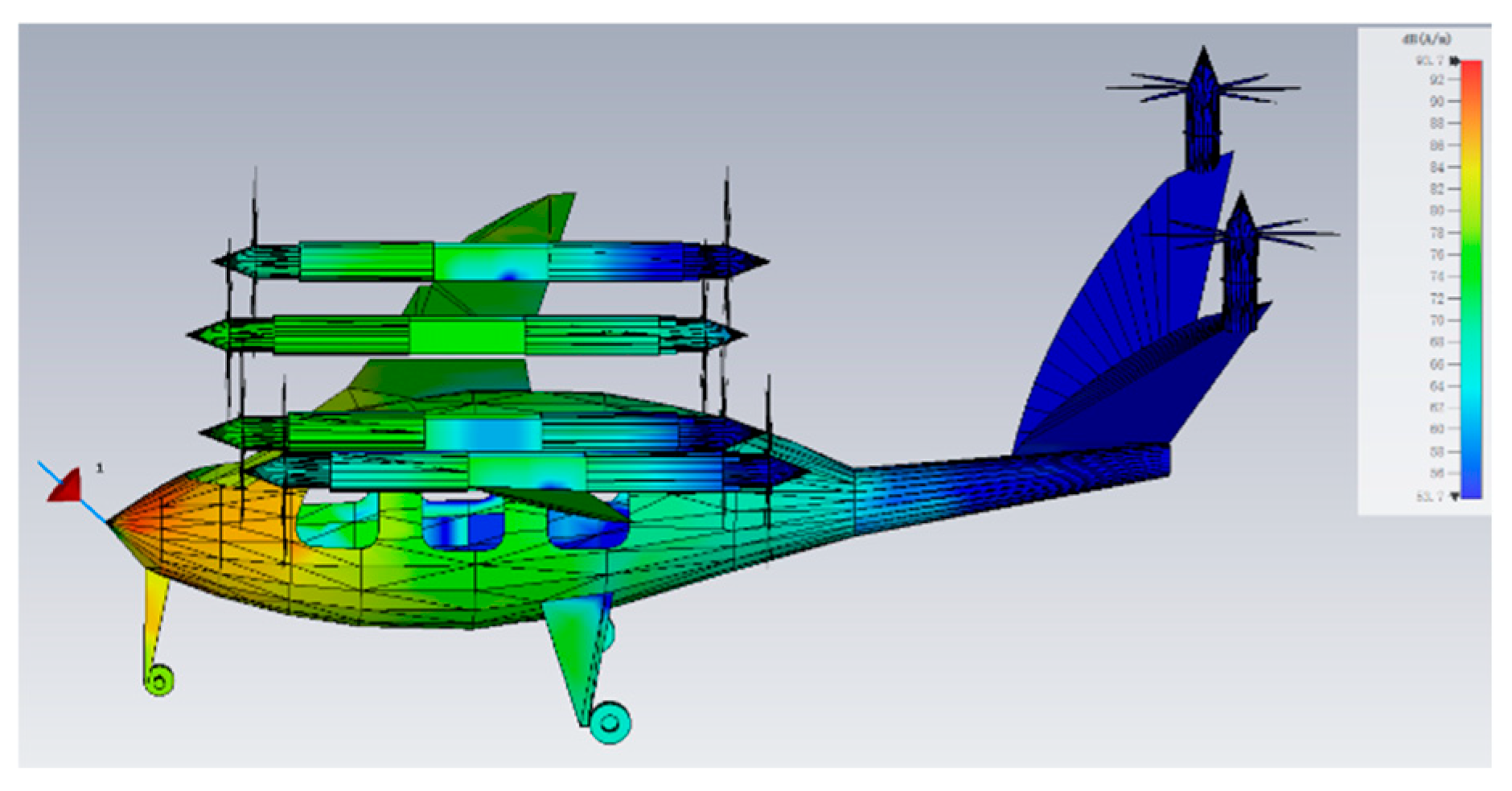

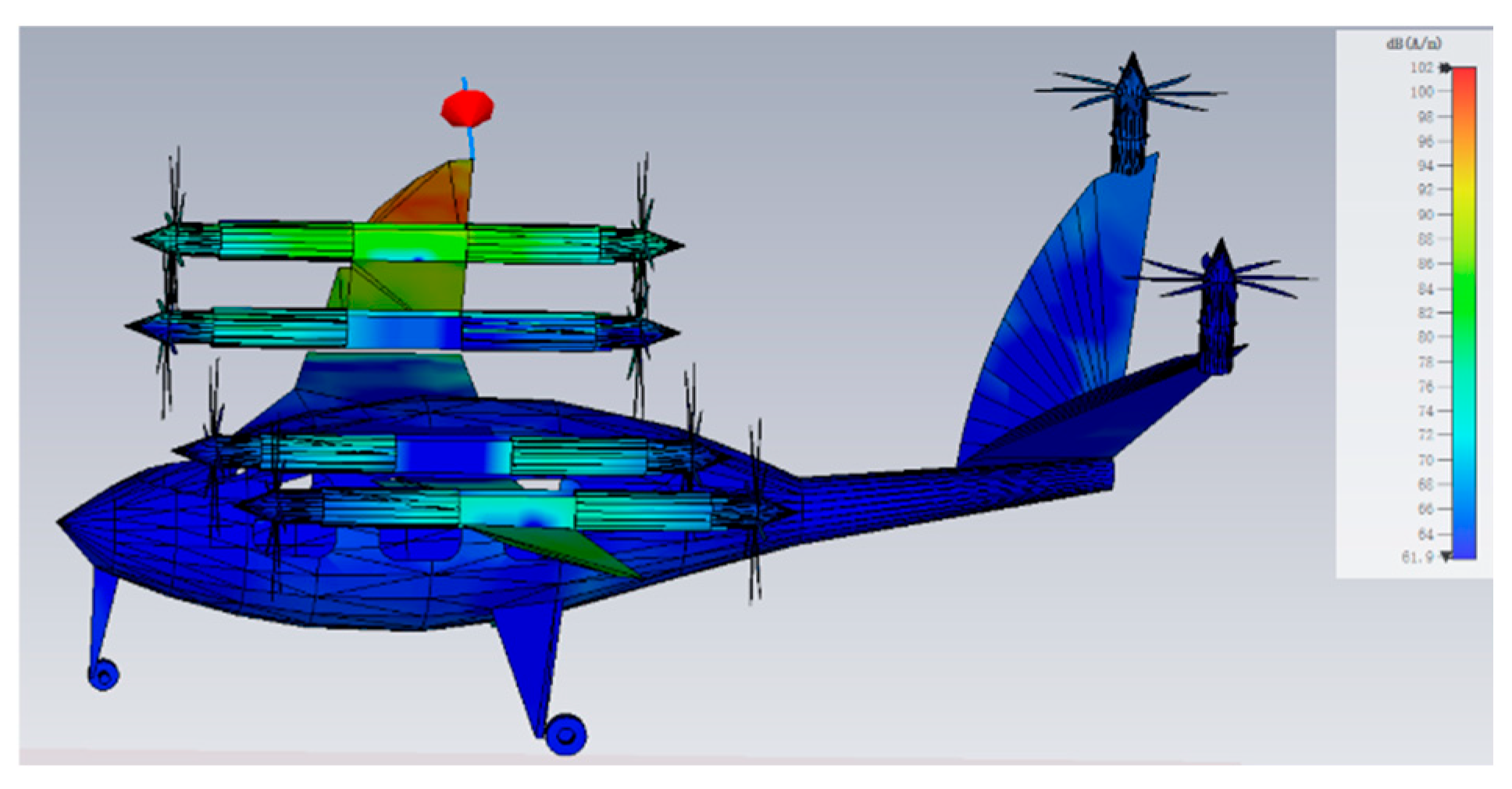

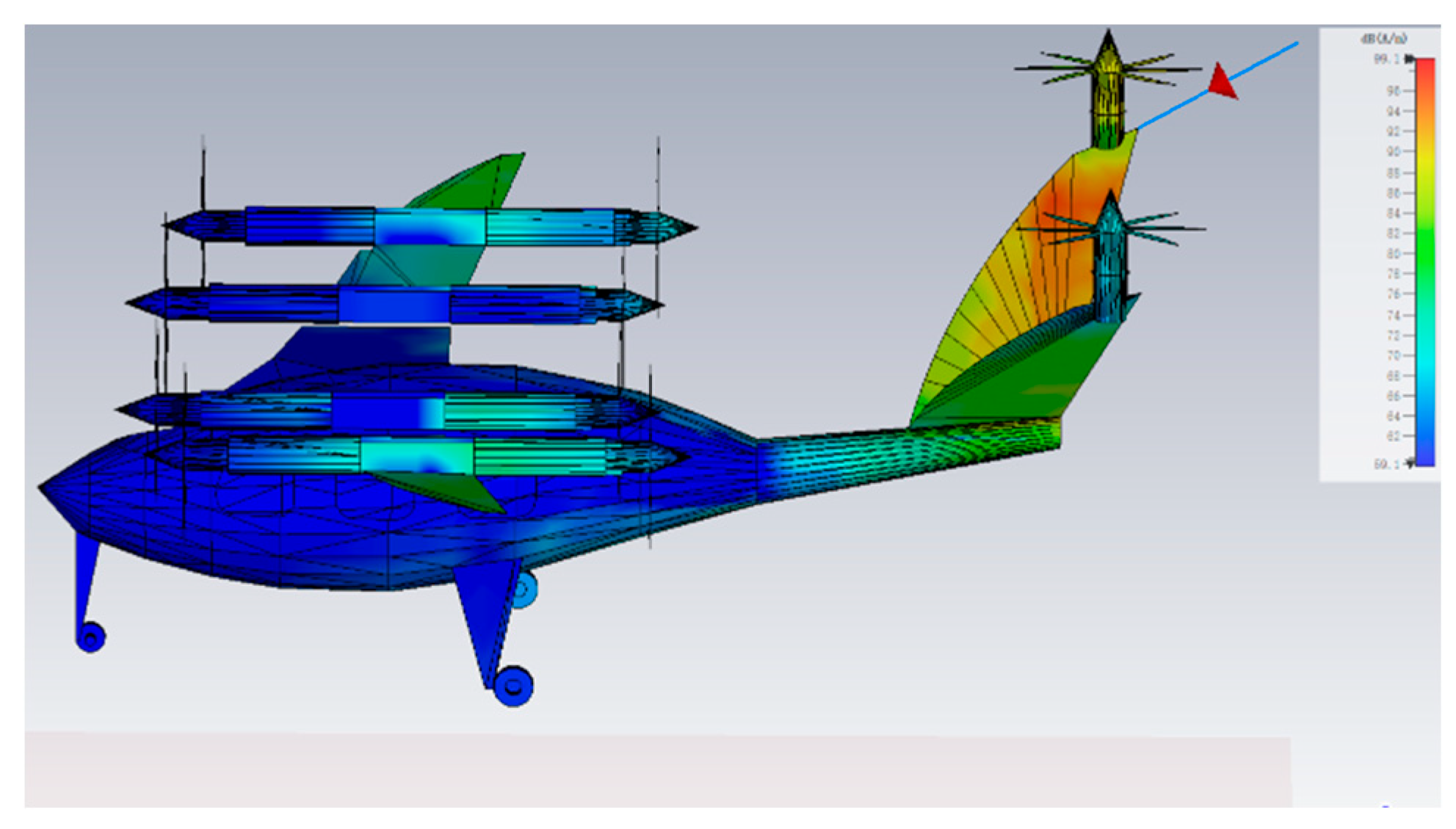

4.2. Aircraft Electromagnetic Response Analysis

5. Cable Coupling Effect Analysis Based on Orthogonal Experiment

5.1. Introduction to the DOE Method

5.2. L9(33) Orthogonal Experiment Design

| Experiment Number | Cable Length | Wiring Method | Cable Structure |

| 1 | 1 m | Wall wiring | Unshielded Single Wire |

| 2 | 1 m | Free-hanging wiring | Unshielded Twisted Pair |

| 3 | 1 m | Zigzag wall wiring | Shielded Cable |

| 4 | 2.m | Wall wiring | Unshielded Twisted Pair |

| 5 | 2.m | Free-hanging wiring | Shielded Cable |

| 6 | 2.m | Zigzag wall wiring | Unshielded Single Wire |

| 7 | 3.m | Wall wiring | Shielded Cable |

| 8 | 3.m | Free-hanging wiring | Unshielded Single Wire |

| 9 | 3.m | Zigzag wall wiring | Unshielded Twisted Pair |

| 10 | 1 m | Free-hanging wiring | Unshielded Single Wire |

| 11 | 1 m | Zigzag wall wiring | Unshielded Single Wire |

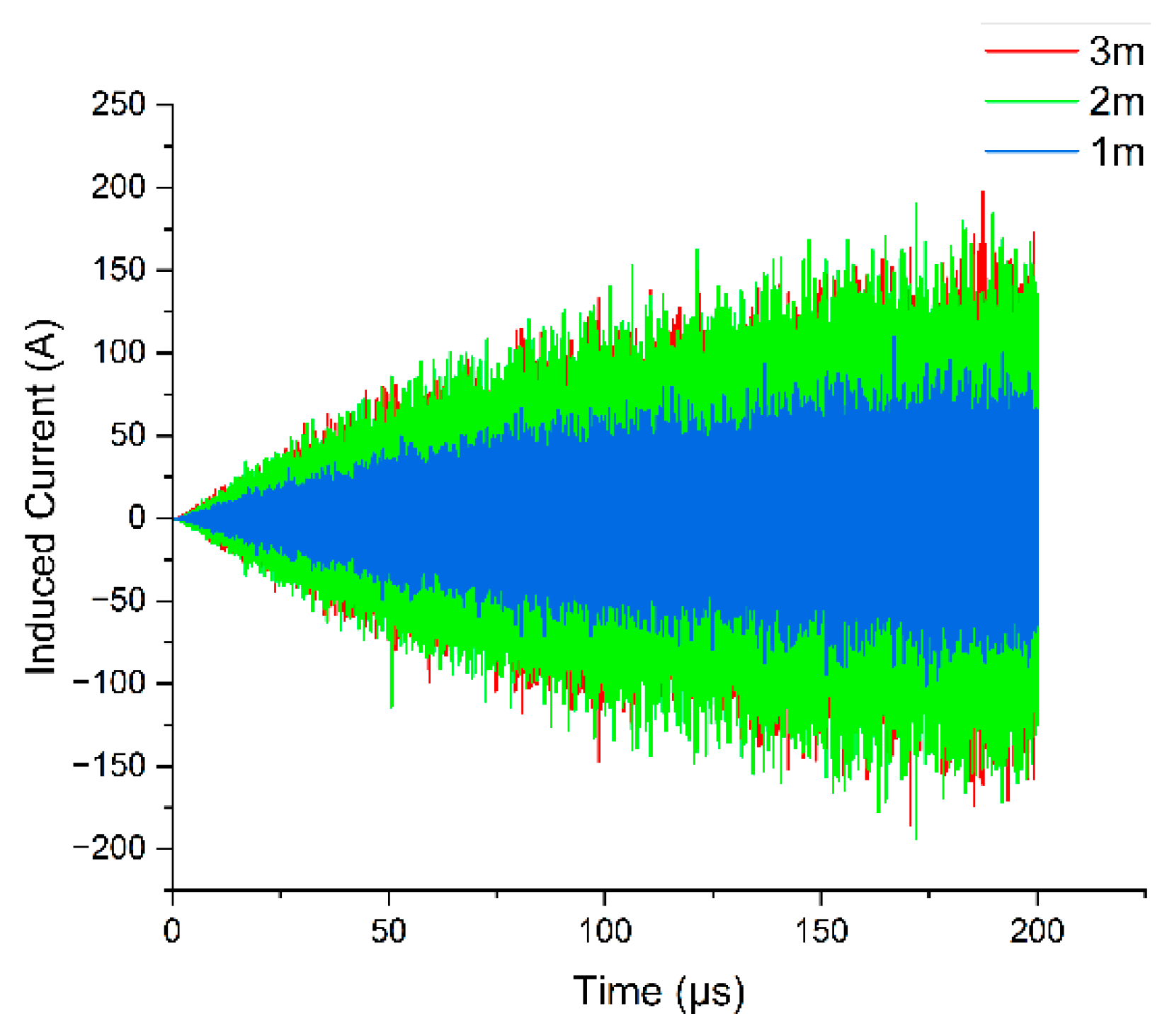

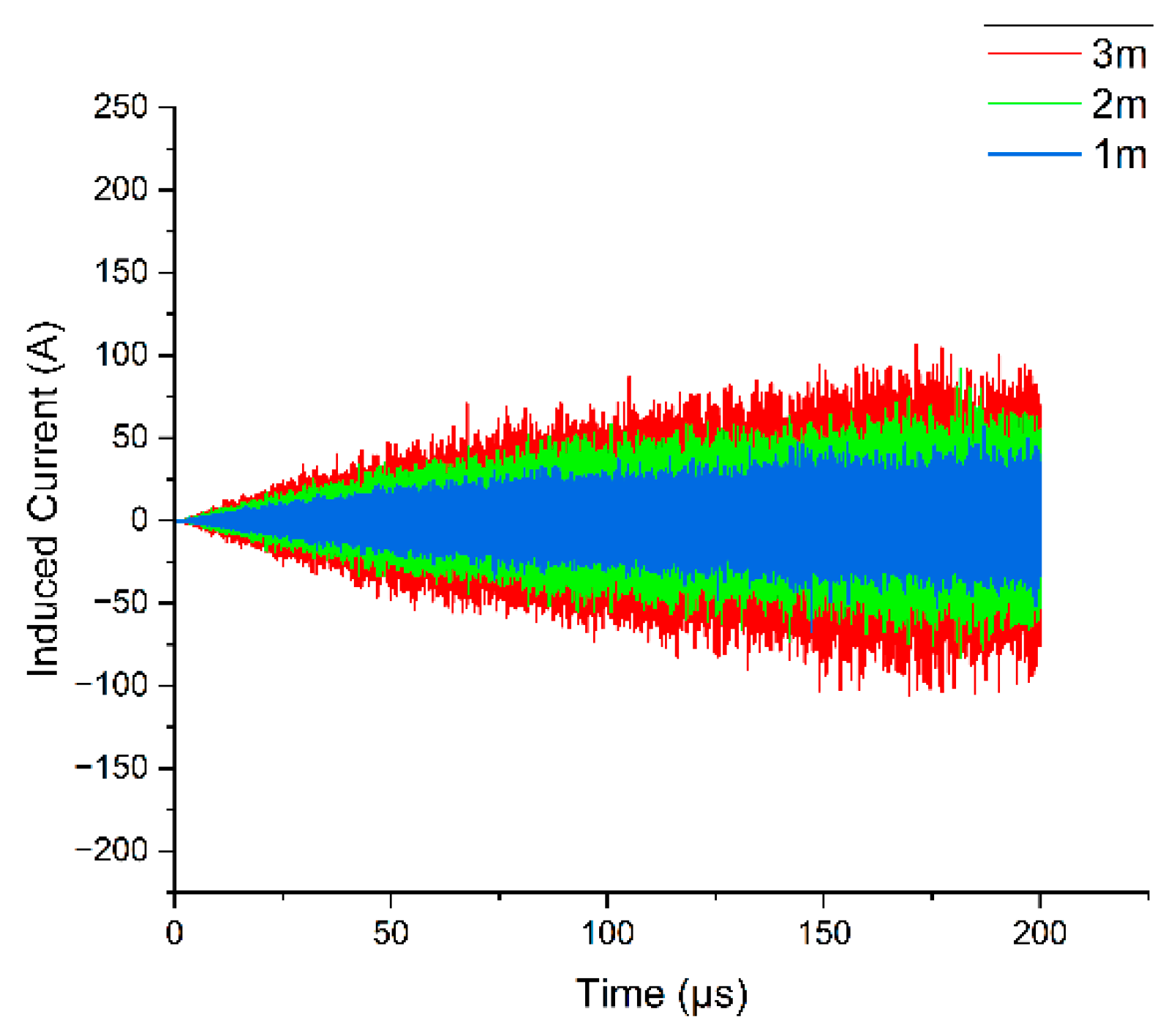

5.3. Analysis of Experimental Results

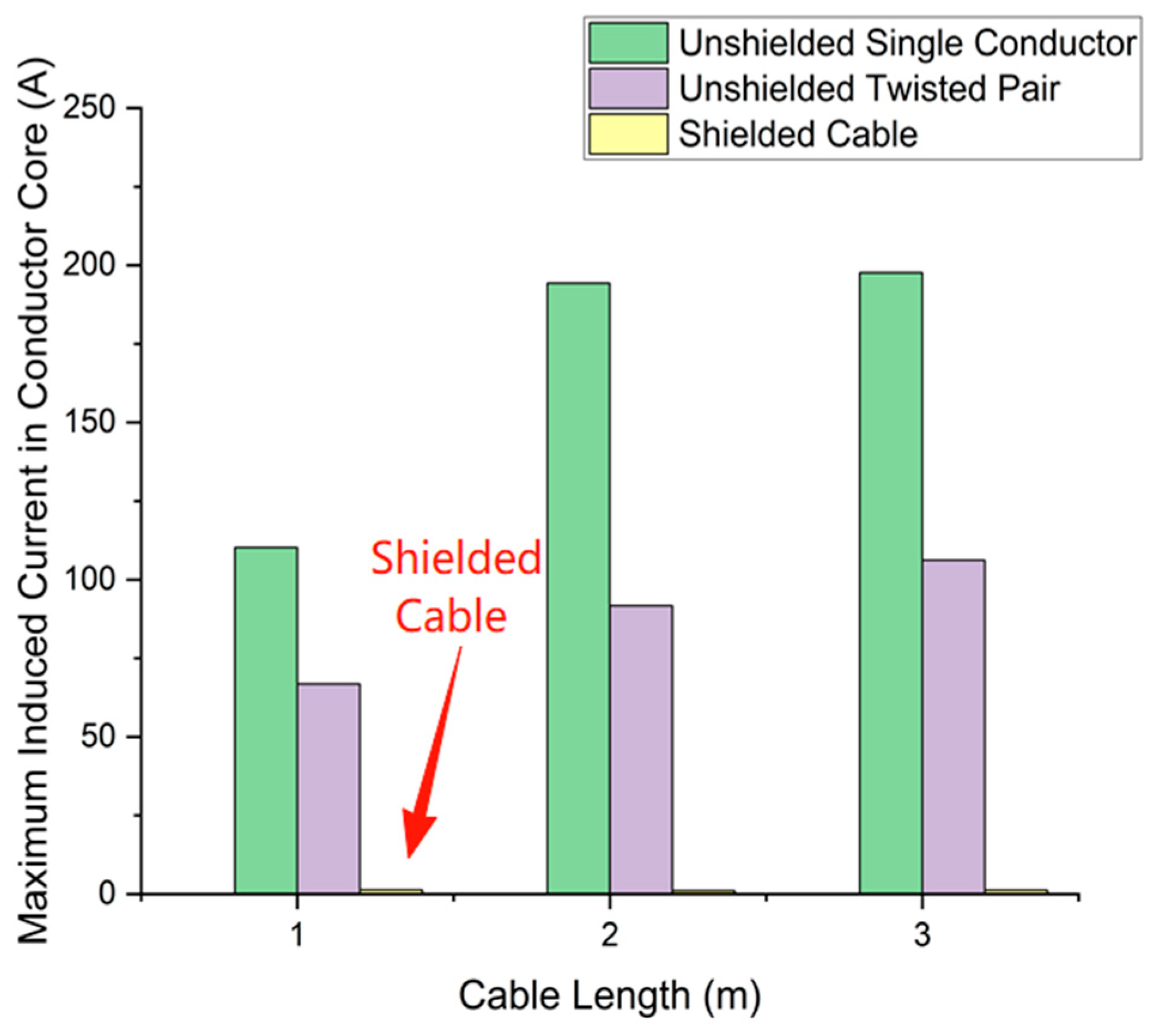

- Cable Structure

- 2

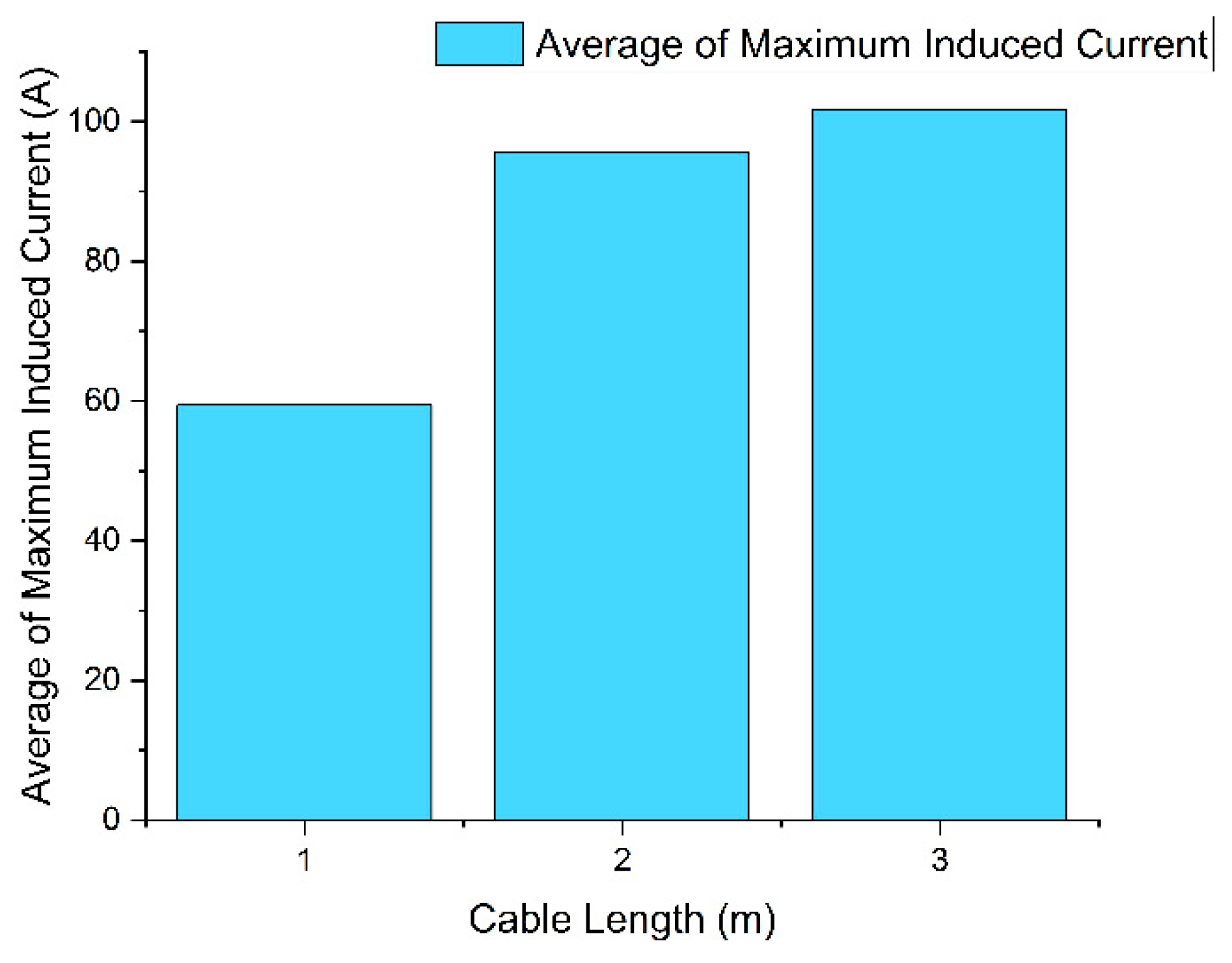

- Cable Length

- 3

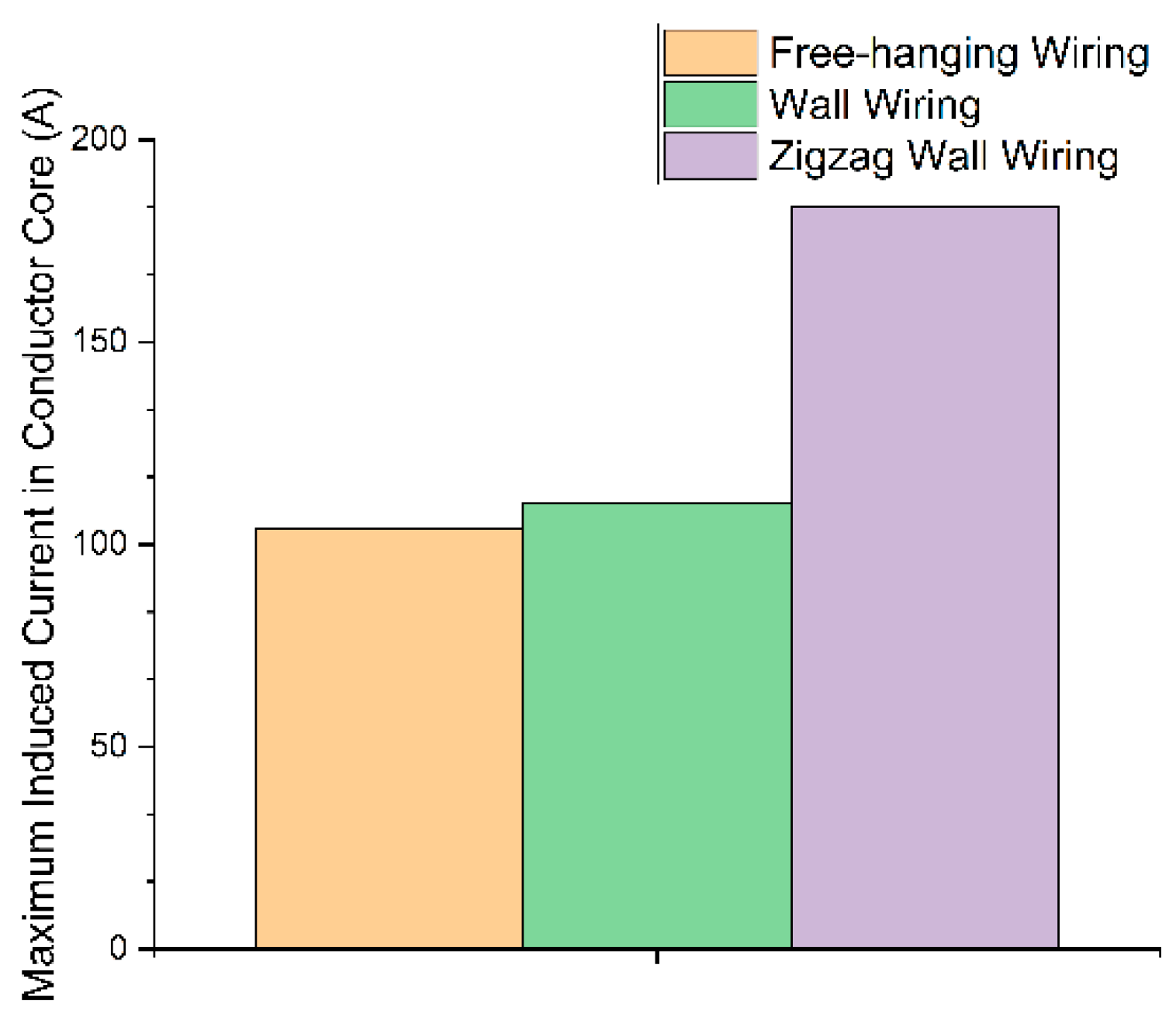

- Wiring Method

6. Conclusion

- Cable Structure: Shielded cables provide the best protection, followed by unshielded twisted pair cables, and lastly unshielded single-core cables. Shielded cables significantly reduce induced current in the conductor core, offering a clear protective effect. They are the preferred structure for improving lightning resistance.

- Cable Length: Induced current is positively correlated with cable length, meaning longer cables generate higher induced current in lightning environments. It is recommended to minimize the length of critical cables.

- Wiring Method: The wiring method also affects induced current, with free-hanging wiring being superior to both Zigzag wall wiring and wall wiring. It is recommended to prioritize free-hanging wiring in the design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, J. (2022). Simulation and Experimental Research on Aircraft Lightning Effects (Master’s thesis, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics). Master’s. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27239/d.cnki.gnhhu.2022.001327. [CrossRef]

- Ding, D. (2022). Research on Lightning Indirect Effects of Aircraft Cables Based on Multivariable Coupling (Master’s thesis, Civil Aviation University of China). Master’s. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27627/d.cnki.gzmhy.2022.000714. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. (2017). Study on Lightning Damage Characteristics of Aircraft Carbon Fiber Composite Laminates (Master’s thesis, Hefei University of Technology). Master’s. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=9IId9Ku_yBYkkC5LghhectgUNAMnHQb5MAfQVub8c6yfyUtBCrOmjdZng5NbQXEgIs7Z7XLhllQsmRT8JPukduHAw_8CKb3eA4UGHDqCPkstsuojmkrhWUI6KrgI5zStUfWrRfnmFqOeIu8bSiFUpK-9p6lum0djMZT3Ka8GaDmtL2P577HnVg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Alkasi, U. (2023). Analysis and Comparison of Lightning Indirect Effects in Aluminum, Composite Fiber Reinforced Plastic and Expanded Copper Foil embedded CFRP Aircraft with EMA3D. 2023 7th International Electromagnetic Compatibility Conference (EMC Turkiye), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Zou, D., Qiang, H., Xi, C., & Sun, H. (2024). Indirect Effects Simulation of Lightning on Military Aircraft Based on EMA3D. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Computational Electromagnetics (ICCEM), 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Wei Y, Shi X. Analysis of Cable Shielding and Influencing Factors for Indirect Effects of Lightning on Aircraft. Aerospace. 2024; 11(8):674. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, P., Lair, C., Issac, F., Michielsen, B., Hélier, M., & Darces, M. (2016). Simulation of indirect effects of lightning on an aircraft engine. 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC), 293-297. [CrossRef]

- Yi-Cheng Qiu. Numerical Simulation Methods for Aircraft Exposed to Lightning Strikes[J]. Acta Aeronautica et Astronautica Sinica. [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y. (2023). Simulation Study on Aircraft Lightning Zoning and the Influence of Lightning Diverter Strips (Master’s thesis, Nanjing University of Science and Technology). Master’s. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27241/d.cnki.gnjgu.2023.002038. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (2023). Research on the Coupling of High-Power Electromagnetic Pulses to Multi-Conductor Transmission Lines (Master’s thesis, Yan’an University). Master’s. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27438/d.cnki.gyadu.2023.000658. [CrossRef]

- Bu, H. (2022). Research on Aircraft Electromagnetic Effects under Lightning Environment (Master’s thesis, Xidian University). Master’s. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27389/d.cnki.gxadu.2022.003683. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Johns, “Development of the TLM method for EMC/EMI analysis,” 2010 URSI International Symposium on Electromagnetic Theory, Berlin, Germany, 2010, pp. 279-282. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. (2016). Simulation and Research on Lightning Indirect Effects on Aircraft (Master’s thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University). Master’s. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=9IId9Ku_yBalkJc4qeihi68__thDp0J8BWiV8107YxedS_QAJ5RAS4z1UFWMpe5urXxnmrTpoKz0QaWWo3o6nHgszuPZX8eyqqRN3ittOOpj13ly2UNpC2zpjm9NU8e4uR75EOhF3mMrxNrUWKeQLQKLZYZtUq2lcWGuE8J2wNLsZNH2tdsiSw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Gen, Y. (2010). Expression of Lightning Electromagnetic Field. Journal of Yunnan Normal University.

- Zhang, P., He, W., Wang, L., & L. (2013). Analysis on Lightning Electromagnetic Fields. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 401-403, 350 - 353. [CrossRef]

- Rakov, V. (2016). Electromagnetic methods of lightning location. 161-177. [CrossRef]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency SPECIAL CONDITION Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) No: SC-VTOL-01, 2 July 2019.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency Fourth Publication of Proposed Means of Compliance with the Special Condition VTOL,No: MOC-4 SC-VTOL, 18 December 2023.

- Federal Aviation Administration Advisory Circular AC No: 21.17-4, June 13, 2024.

- Federal Aviation Administration Statement on eVTOL Aircraft Certification Monday, June 10, 2024.

- Interim Regulations on the Flight Management of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Gazette of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2023, (20):6-16.

- Rules for the Operational Safety Management of Civil Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Gazette of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2024, (09):35-84.

- Special Conditions for EHang EH216-S Unmanned Aerial Vehicle System SC-21-002, 2022-02-09.

- Special Conditions for Autoflight V2000CG Unmanned Aerial Vehicle System SC-21-004, 2023-11-12.

- Draft Special Conditions for Aerofugia AE200-100 Electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing Aircraft for Consultation, 2023-12-01.

- RTCA DO-160G Environment condition and test procedures for airborne equipment[S]. Special. 135(SC-135) and approved by the RTCA Program management committee (PMC), 12-2010.

- SAE Aerospace. SAE ARP5412B. Aircraft Lightning Environment and Related Test Waveforms [S]. USA: Society of Automotive Engineers, 2013.

- SAE Aerospace. SAE ARP5416A. Aircraft Lightning Zone [S]. USA: Society of Automotive Engineers, 2018.

- SAE Aerospace. SAE ARP5416A. Aircraft Lightning Test Methods [S]. USA: Society of Automotive Engineers, 2013.

- Aerofugia. (2023). AE200Y airworthiness configuration prototype [Image]. Source: China Civil Aviation New China Civil Aviation Network.

| Zone | Sub-zone | Description | Lightning Attachment Characteristics |

| Zone 1 | 1A | Initial attachment, short dwell time | High attachment probability, short duration |

| 1B | Initial attachment, long dwell time | High attachment probability, long duration | |

| 1C | Smaller first return stroke, short dwell time | Medium attachment probability, smaller current | |

| Zone 2 | 2A | Sweeping attachment, short dwell time | Subsequent lightning, short sweep duration |

| 2B | Sweeping attachment, long dwell time | Subsequent lightning, long sweep duration | |

| Zone 3 | Low probability of direct attachment, only conducts lightning current | Current path, no direct strike | |

| Component | Name | Key Parameters |

| A | First Return Stroke | Peak current: 200 kA ± 10% Action Integral: 2×106 A2·s ± 20% Duration: ≤ 500 μs |

| B | Intermediate Current | Maximum charge transfer: 10 C ± 10% Average current amplitude: 2 kA ± 20% Duration: ≤ 5 ms |

| C | Continuing Current | Current amplitude range: 200 ~ 800 A Charge transfer: 200 C ± 20% Duration: 0.25 s ≤ t ≤ 1 s |

| D | Subsequent Return Stroke | Peak current: 100 kA ± 10% Action Integral: 0.25×106 A2·s ± 20% Duration: ≤ 500 μs |

| Strike Location | Maximum Surface Electric Field Strength (V/m) | Maximum Surface Magnetic Field Strength (A/m) |

| Nose | 84,426 | 48,364 |

| Wing | 189,000 | 125,000 |

| Vertical Tail | 112,000 | 90,513 |

| Experiment Number | Maximum Induced Current in Conductor Core (A) | Maximum Induced Current in Shielding Layer (A) |

| 1 | 110.19 | None |

| 2 | 66.75 | None |

| 3 | 1.35 | 374.58 |

| 4 | 91.67 | None |

| 5 | 1.05 | 257.81 |

| 6 | 194.27 | None |

| 7 | 1.29 | 318.32 |

| 8 | 197.61 | None |

| 9 | 106.22 | None |

| 10 | 93.86 | None |

| 11 | 183.46 | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).