1. Introduction

Nanotechnology is the area of concern that was established in 1900 and it resulted in there being a whole array of nano-scale materials, which include nanoparticles. These are particles that contain powder materials that are less than 100 nm in size and dimension and may be 0D, 1D, 2D or 3D [

1,

2,

3]. The significance of nanoparticles came to light when some researchers found out that their size can affect the physiochemical nature of an object like optical capabilities. [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The nanoparticles can be categorized into several groups based on size, shape, and chemical characteristics. The more common forms are carbon-based nanoparticles, such as fullerenes and carbon nanotubes as well as metallic nanoparticles wherein the metallic precursors are all that is used, ceramic nanoparticles, semiconductor nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles and nanoparticles made of lipids. Lipid nanotechnology aims at producing and using lipid nanoparticles as the carrier molecules, therapeutic delivery, and even RNA release in the case of cancer treatment. [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

26,

27]. There exist two ways of synthesizing nanoparticle: bottom-up and top-down. The top-down synthesis entails reduction of the larger molecules into smaller ones, including grinding/milling or physical deposition of vapors (PVD). Production of nanoparticles using simple chemicals or compound involves the use of both bottom-up and top-down synthesis methods. [

27,

28,

29,

31,

32]. Due to the characteristic enormous surface area, mechanical, optical, and chemical reactivity of nanoparticles, these particles are suitable candidates to be used in a variety of applications. The electrical and optical properties they possess are getting intertwined, and the nanoparticles consisting of noble metal groups have a specific UV-visible spectrum and optical behavior with the size. [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

39,

40]. Magnetic nanoparticles have been of interest in different areas such as catalysis, biological medicine, magnetic fluids and environmental remediation. Irregular electrical scattering and artificial procedures have an impact on their magnetism behavior. Mechanical properties have variant and stress, abrasion, durability, and elastic modulus and adherence which are also affected by lubrication, coagulation, surface coatings and many more. [41.42,43,44,45,46]. Nanoparticle thermal properties have greater heat conductivity as compared to liquids that take the form of solid components in the form of copper, alumina, and oxides like alumina.[

47]. Nanoparticles are encompassing materials that are used in many ways such as drugs and medicine. They may provide medication in the optimal concentration range, so the treatment process would be advanced, the side effects would be reduced, and the patient compliance would be improved. Magnetite and maghemite represent the iron oxide particles routinely applied in biological applications. Potent approaches to drug delivery in IV are polyethylene oxide (PEO) and poly lactic acid (PLA) nanoparticle. The use of super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles is possible in vivo, through MRI contrast enhancement, tissue repairing and diagnostics, purification of biological fluids, hyperthermia, drug delivery and cell separation. [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Nanoparticles are developed to be biodegradable and thus enhance drug ratability and give controlled drug dissolution abilities. They can also be applied against cancer since more light is absorbed and scattered through the surface Plasmon resonance (SPR). Consumable items using nanotechnology are fitness and health products, electronics, household, and gardening products. 56,57, 58,59,60] Nanotechnology is being propagated as the new industrial revolution in production and packaging of food. It has been greatly found in the commercial products and the metallic nanoparticles such as rare metals like Gold and silver being of great variety of colors owing to Plasmon resonances. Due to increased use of nanoparticles in commerce and household applications, they find their way into the environment and hence the need to understand how they can be ported, react, their ecological toxicity, and stability [

61,

62]. Ecological applications of nanotechnology are long-term environmentally friendly products, restoration of components that can be quite dangerous and that are contaminated with substances, and ecological phase sensors. In the eradication of F in the form of lead, mercury, thallium, cadmium and arsenic, superparamagnetic ferrous oxide nanoparticles act as a promising absorbent in such pure water. [

63]. Nano-sized particles in electronics ought to become widely spread because a mass-production process of new forms of electronics. One of their characteristics is that they are easy to control and build in reverse fashion to allow the inclusion in an electric, wiring, or optical component via the use of a “bottom up” or “self-assembly” manufacturing process. Special capabilities/applications Nanocalcite or nanolime-CaO nanoparticles have special applications including as catalysts, in medical science, atmospheric scrubbing, power storage and in building materials. Environmental conditions and media contents have a considerable impact on their dimension, structure, equality, and property. This study is targeted to identify optimal methods of controlled size synthesis of CaO nano- particles and its successful biological use which will give an idea of size-specific use of this nanoparticle in the case of pathogenic species.

2. Literature Review

Nanotechnology has proved to be a groundbreaking field that has wide application in medicine, agriculture, environmental treatment, and energy (Kumari et al., 2023). Calcium oxide (CaO) nanoparticles are just one among a bulk of other nanomaterials that have been chosen in accordance with some of the elements of electrical, optical and chemical properties which simply appear to be typical. , CaO is used in catalysis, paint production, refractories, toxic wastes, as well as others (Bankovic-Lilic et al., 2017). The chemical and physical properties of naturally occurring nanoparticles (such as the wildfire ash or mountain ash) are also in the line of properties of engineered nanoparticle, commonly known as small particles to date (Yadav et al., 2021). The shapes, sizes, uniformity, and efficacy of nanoparticles are significantly influenced by the synthesis processes, and to a distinct degree, by the parameters behind the synthesis processes that are the temperatures such as heating and cooling parameters, along with the type of a solvent and environmental conditions (Kumari et al., 2023). Techniques that are demonstrated with solution stage characterization have demonstrated potentiality to produce large scale of precisely characterized agglomerates. These mechanisms are significant towards the desired manipulation of properties to certain applicable tasks such as drugs loads and gene therapy alongside packaging technologies (Yadav et al., 2021). The only drawback is that CaO loses the carbonation capacity after several carbonations and decarbonation processes have been done. The reusability of it has been tried by doping, chemical pre-treatment, and hydration of it to raise the stability of CaO against CO 2 (Bankovic-Lilic et al., 2017). Research interests in biomedical research that concern CaO nanoparticles in antimicrobial activity are growing. The nanoparticles of metal are quite effective against multi-drug resistance (MDR) bacteria because reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced, which cause the death of cells (Kumari et al., 2023). By using E. coli Fe-Mn superoxide dismutase as a target the in-silico analysis demonstrated antimicrobial and anti-biofilm effects of CaO nanoparticle by offering a molecular basis on their mode of action (Kumari et al., 2023). The CaO nanoparticle is also good in making organic synthesis. The proof about the efficiency of the CaO NPs as a green catalyst is that, e.g., these particles can be a good heterogeneous catalyst to catalyze three-component reactions of thiols, aldehydes, and malononitrile in order to form highly substituted pyridines (Yadav et al., 2021). Similarly, the CaO nano catalysts are also integrated in the production of biofuels where they have been utilized in the transesterification of the triglycerides where biodiesel production was done using the catalysts, which are used to produce environmental-sustainable substitute to the conventional fuels (Bankovic-Lilic et al., 2017). The use of waste-derived materials has gained popularity as the source of the sustainable CaO. Yadav et al. (2021) found out that an estimated 1 billion tons of wastes comprising calcium are generated on annual basis and will offer a distinctive feedstock in relation to chemical and mechanical deliquescence processes so that it can be utilized in the creation of nanoparticles. These CaO NPs developed through waste products have the benefits of relying not only in the environmental remedy (i.e., the absorption of heavy metals) but also lowering the expense and toxicity as compared to the conventional methods of manufacturing. Problem free method, the eco-friendly method is the green synthesis of nanoparticle of CaO eg. with the help of extract of Ocimum tenuiflorum leaf which is biocompatible. The green synthesis of CaO NPs is high in antibacterial properties against Gram-positive bacteria, and Gram-negative (Kumari et al., 2023). Moreover, CaO NPs are also tried when a subject of Agric stake utilized as nano-macronutrients resulting into sustainable agriculture. The second other main research that were done were the reproduction of CaO NPs that were filtered with the help of hen eggshells to treat the Pb 2+ ions contaminated water. Initial concentration, pH 6.94, 0.838 g of adsorbent and 101.97 minutes contact time to give the best result was at the initial concentration of 75.46 ppm. They found that the process of adsorption conformed to the Langmuir isotherm model (R 2 = 0.9963) and the pseudo-second-order kinetics, which is an indication of the role of CaO NPs in the process of water purification (Yadav et al., 2021). It is the frustrating evolution of MDR pathogens that has escalated the aspect of new antimicrobial agents on a worldwide basis. The characteristics of the mechanisms that trigger the production of ROS mean that the CaO NPs can replace traditional antibiotics. As the world shows an increasing concern with the use of nanoparticle-based treatment, CaO NPs could be regarded as a great choice of treatment in the case of resistant microorganisms and in dissolving biofilms (Kumari et al., 2023).

3. Methodology

Calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaO-NPs) have been prepared through direct precitation route by the combination of calcium chloride and sodium hydroxide. The solution A which was 1.10981098 g CaCl 2 in 50mL of deionized water was stirred at 40 00 C and Solution B 0.2g NaOH and 50mL of deionized water stirred such that each finished in an hour. The solution B was added slowly to Solution A to bring about a pH of 10.5 after which consistent stirring was maintained over a period of 24 hours. This mixture was oven dried at 70 o C in 6 hours. The intermediate that has been collected was ultrasonicated and washed six times and separated using a magnet and then completely dried in a microwave over a 24-hour period. The centrifugation was done at 7000 rpm at 8 minutes and the CaO-NPs were dried again before the characterization. CaCl 2, NaOH, ethanol and distilled, deionized water, beakers, magnetic stirrers, autoclaves, ovens, spatulas, sonicators, and Eppendorf tubes were the chemicals and instruments used respectively. Biological potential of CaO-NPs was measured through antibacterial tests, hemolysis, and tests on cytotoxicity. Testing on the antibacterial activity was performed on six MDR bacteria (E. coli, Shigella, Citrobacter, Serratia odorifera, Enterobacter cloacae and Enterobacter amnigenus) with an encouraging result. Hemolysis changes were determined as blood with CaO-NPs (250750ug/mL) were abided at intervals before centrifugation and examination using a spectrophotometer at 540nm. Cytotoxicity by brine shrimp was performed by placing Artemia salina nauplii into CaO-NPs (250 and 300 ug), and the rate of mortality after 24 hours was counted which was a moderate level of toxicity and biomedical applications.

4. Characterization

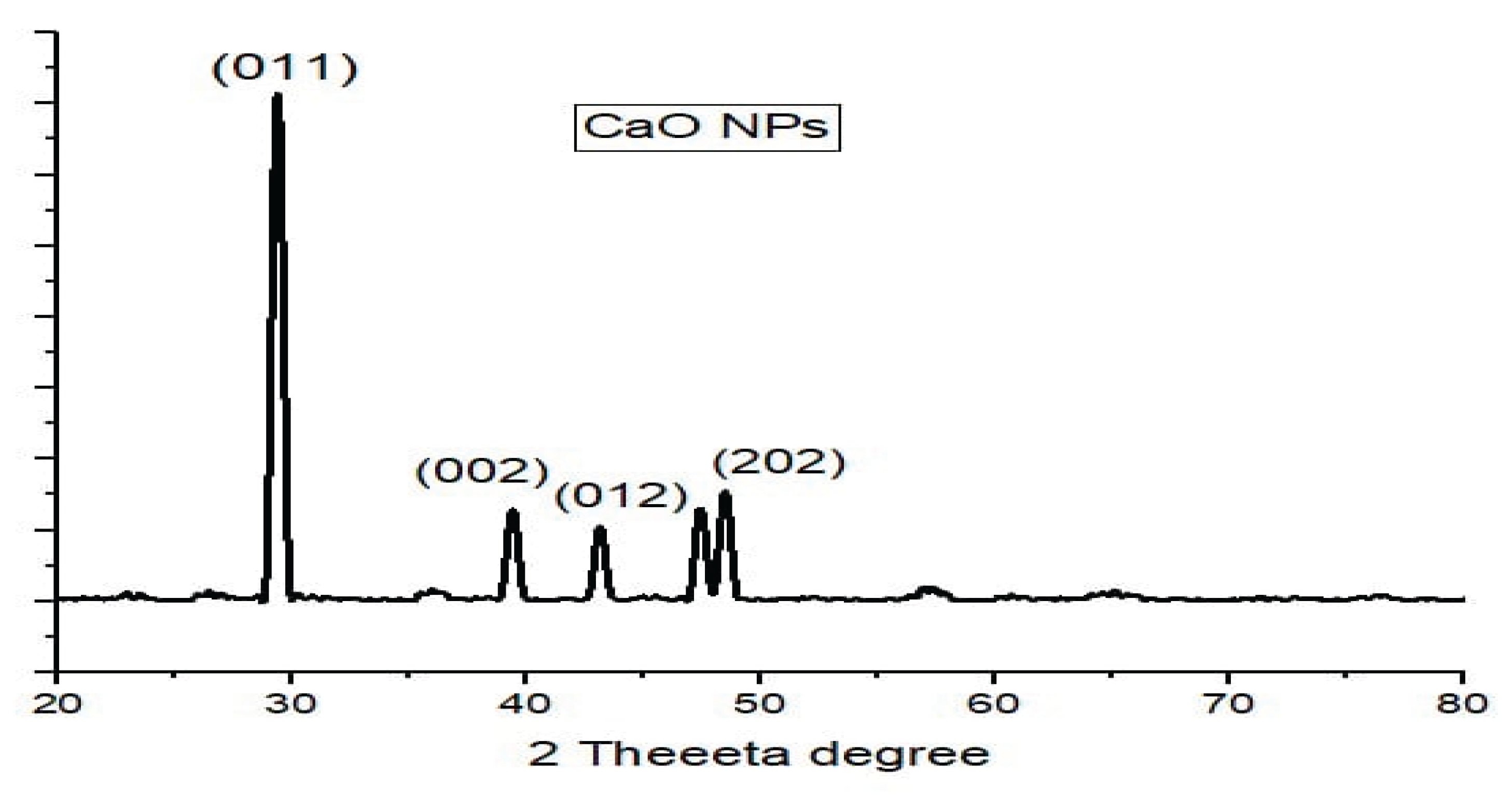

One of the methods of studying the structure is x-ray diffraction (XRD) that allows receiving data on the size, the texture, and the weight of the specimen’s structure. The X-rays made by cathode ray tubes are homogeneous and are projected on the material where they are reflected, and the level of dispersion is determined to determine the crystallographic form. The positioner of the crystalline lattice scatters the light. The established nanoparticles (NPs) were analyzed through XRD which gave information on the CaO nanoparticles and establishing them into a graph using origin software. The strength of the produced CaO nanoparticles was quantified based on their strong peaks in the approach provided by Scherer.

The XRD spectrum of synthesized calcium oxide nanoparticles proved accurate structure in crystalline state, as well as doing away with contaminants in CaO XRD spectrum. This serves as an indication that the produced CaO nanoparticles are pure and with the high degree of crystalline structure that serves as concurrent evidence to the CaO nanoparticles. The median particle dimension can be determined through Debye-Scherer technique.

The XRD graph demonstrates the pattern that only has three intensity peaks during the treatment with two additional spikes at the point of 800 and 1050 intensities. These sharp peakes were used to make use of the Sherrors strategy to determine the magnitude of the nanoparticles produced.

Table 1.

Determination of Crystalline size of CaO Nano-particles, using Debye scherrer equation}.

Table 1.

Determination of Crystalline size of CaO Nano-particles, using Debye scherrer equation}.

| Quantity of peaks achieved |

2 ( θ)

|

FWHM (β) represents full width at 1⁄2 maximum |

Peak length determined by Debye-Scherrer formula

D=k λ/β cos θ |

| Peak 1 |

29.36625 |

0.20798 |

36.9493743 nm |

| Peak 2 |

35.94776 |

0.16793 |

44.99844183 nm |

| Peak 3 |

39.38408 |

0.17237 |

43.39320114 nm |

| Peak 4 |

43.13949 |

0.1964 |

37.61688966 nm |

As a result, we can determine the dimension of CaO nanoparticles using the pattern of XRD. Each peak size is displayed above. So the standard size of a CaO nanoparticle is 38.64749 nm.

Figure 1.

XRD Spectrum of CaO Nano-particles.

Figure 1.

XRD Spectrum of CaO Nano-particles.

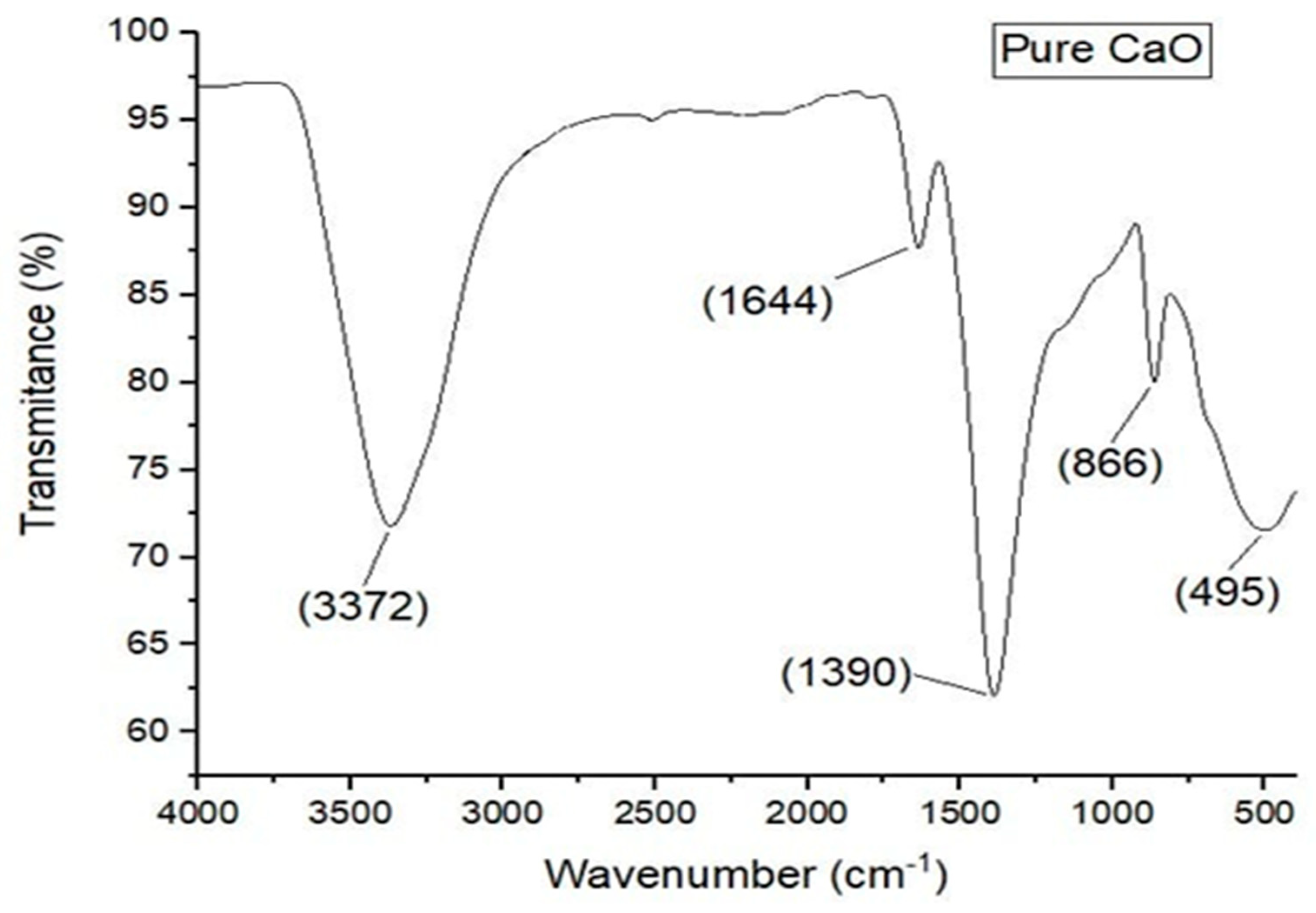

In this technique, detection and classification of the particles is carried out. One may find structural groupings through FTIR spectra. In Calcium oxide testing, a dehydrated fluid on the crushed material is mixed and analysed under FTIR on 4000-500 centimeters per spectrum. The band has certain characteristics: peaks in 495, 822, and 1390 cm-1 are indicative of a metal-oxide complex in the samples in the form of Ca-0 symmetric extending, Ca-0 asymmetric extending, and Ca-0 wagging respectively. A high vibration intensity at 3372 cm-1 identifies an existence of hydroxide group in the sample. It can be done because the Calcium oxide nanoparticles have the moisture on their external covering which is the byproduct of the process and this moisture can be eliminated by further heating. The bonding of the metal oxygen at 1644 cm -1 (M-O rocking in the plane) ratio means that calcium sulphate forms the CaO. FTIR was used to characterize Calcium oxide Nanoparticles, and it obtained results. The information is then shown in the original programmed that will give a graph with details of created Calcium oxide Nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

FTIR Spectrum of CaO Nano-particles.

Figure 2.

FTIR Spectrum of CaO Nano-particles.

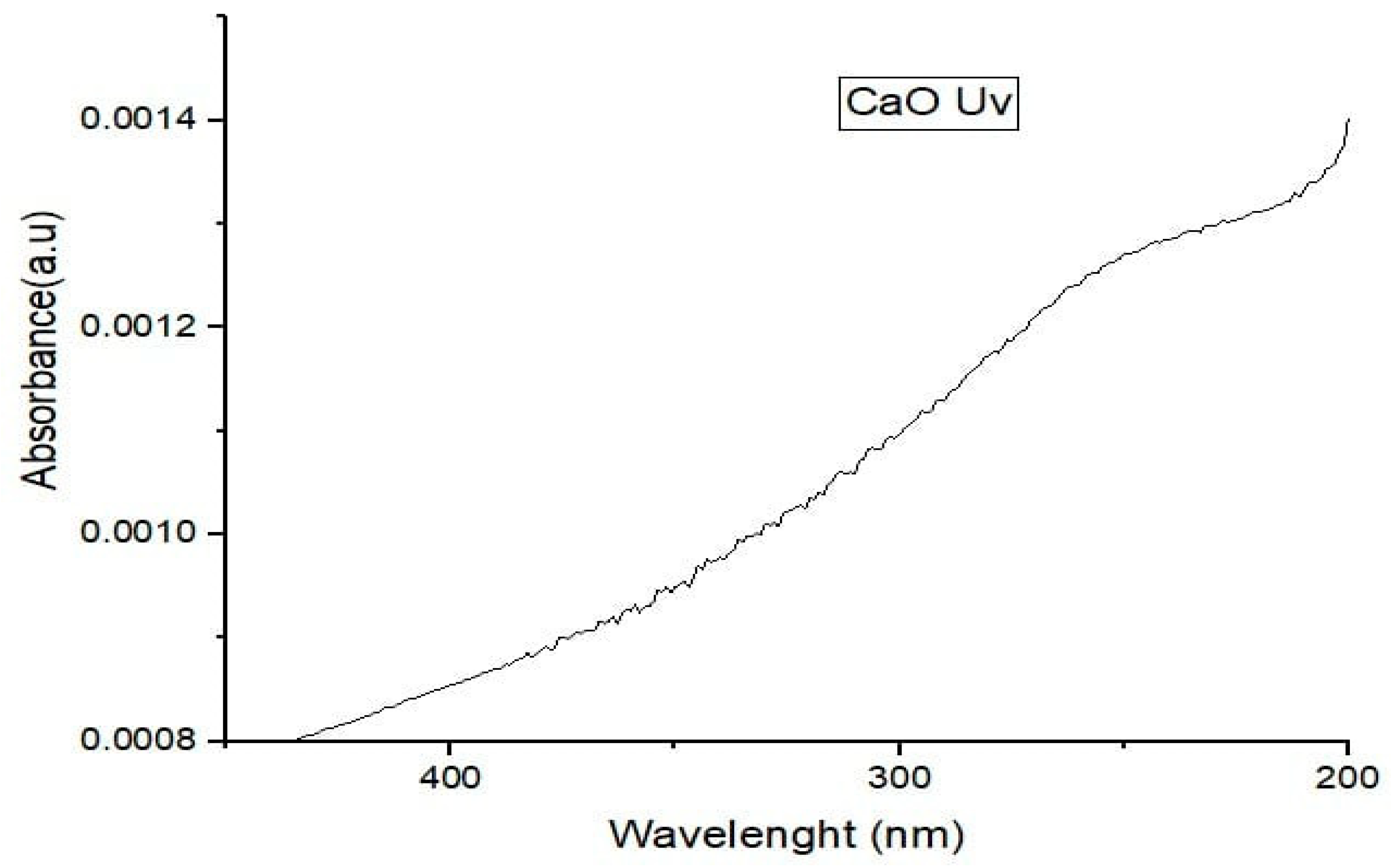

CaONano-particles were analyzed using ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy. Figure 4 shows the UV-vis spectroscopy of CaO Nano-particles. The figure clearly shows that. CaO Nano-particles have extensive absorption at wavelengths below 400 nm. While doing UV is spectroscopy on CaO.

Figure 3.

UV Spectra of CaO Nano-particles.

Figure 3.

UV Spectra of CaO Nano-particles.

5. Biological Applications

The study aimed to evaluate the antimicrobial properties of calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaO Nps) on six microbial variants. The results showed that CaO NPs exhibited outstanding antimicrobial properties for all six microbial variants, with zones of resistance for the Shigella variant, Enterobacter cloacae, and Enterobacter amnigenus variants. The zone of inhibition for Seretia odoriface, Citrobacter, and E. coli variants was also significant. The research also showed that increasing the quantity of Calcium oxide precursors in calcium oxide nanorattles boosted their inhibition action. This research demonstrated that Calcium oxide had high antimicrobial properties. Klapiszewski and colleagues found that CaONP had a better antimicrobial impact towards gram-negative microbes than gram-positive microbes. Das et al. and Parandhaman et al. investigated the antimicrobial effects of CaO nanorattles having varied CaO amounts, and their findings demonstrated that the greater the quantity of CaO, the stronger the inhibiting impact of nanorattles on bacterium. However, when the quantity of CaO NPs was raised to 2mg/mL, bacterial development was prevented. Nano CaO nanoparticles showed strong antimicrobial properties, killing microbes as high as 99.9%. Microbes may continually absorb CaO ions released by these substances, causing them to go into the death stage. The antimicrobial capacity of CaO nanoparticles was investigated towards both gram-positive (Staphylococcus epidermises) and gram-negative (E.coli). The outcomes revealed that E.coli was extremely susceptible to CaO nanoparticles. The antimicrobial capacity of CaO nanoparticles carrying 0.5 milliliter of TEOS was assessed towards Staphylococcus aureus bacterium. The zone of inhibition measured 17 millimeters at two hundred and fifty microgram per milliliter, eighteen millimeters at five hundred microgram per milliliter, twenty-two mm at seven hundred and fifty microgram per milliliter, and twenty-four millimeters at one thousand microgram per milliliter. The TEOS covering on CaO nanoparticles was exclusively efficient for Staphylococcus aureus bacterium when compared to E.coli. CaO nanoparticles were covered with the polymer chitosan, and their antimicrobial efficacy was evaluated against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (E.coli and Vibrio cholera). The results revealed that such encapsulated Nanoparticles were highly efficient over gram-negative bacteria than gram-positive bacteria. Further investigation found that CaO NPs had antimicrobial properties with Bacillus subtilis and E.coli. At a dosage of 63.3 mg/mL, CaO NPs completely inhibited Bacillus subtilis growth with a zone of inhibition of 15.5 mm, and at an amount of 42.2 microgram per milliliter, E.coli development was entirely inhibited with a zone of inhibition of 16.1 millimeter. It was also shown that CaO NPs were more efficient towards E.coli.

Table 1.

Results of Antibacterial Assay for CaO Nps.

Table 1.

Results of Antibacterial Assay for CaO Nps.

Serial No. |

Name of Bacterial Variant. |

Identification No. |

Concentration of CaO Nps (microgram per milliliter) |

Zone of Inhibition (mm) |

| 1. |

Shigella |

12 |

500,1000,1500 |

7,11,18 |

| 2. |

Enterobacter cloacae |

13 |

500,1000,1500 |

13,15,18 |

| 3. |

Enterobacter amnigenus |

15 |

500,1000,1500 |

11,14,16 |

| 4. |

Seretia odoriface |

24 |

500,1000,1500 |

13,16,20 |

| 5. |

Citrobacter |

25 |

500,1000,1500 |

7,12,17 |

| 6. |

E.coli |

57 |

500,1000,1500 |

18,21,24 |

The findings of the directly grown CaO nanoparticles (CaO Nps) was that they were of the hemolytic nature where the blood vessels ruptured and therefore they were toxic. Higher hemolysis was obtained as amounts of CaO Nps were increased. Hemolysis at 250 microgram per milliliter of CaO Nps was 12.4 percent whereas the hemolysis at 500 microgram per milliliter of CaO Nps was 17.5 percent. 725 microgram per milliliter of CaO Nps caused 21.01 hemolysis activity. The highest activity of hemolysis was observed at 725 microgram per milliliter. Hemolysis could be created by gold nanoparticles of size between 5 nm and 20 manometer. Twenty microgram per milliliter of Au nanoparticles had a greatest increase to induce hemolysis. One hour of incubation of Au nanoparticle and blood serum triggered hemolysis. The increment in CaO Nps led to increase in hemolysis percentage. The particles that were nanometers in size were found to be more hemolytic as compared to those that were reduced to micrometers. Nano particles at a level of 700 microgram per milliliter produced 50 percent hemolysis as compared to 12 percent hemolysis by the micro-sized particles. Greater amounts of CaO Nps ( >70 micro gram per milliliter) led to hemolysis of more than 5 per cent. Zook et al. (2010) reported big size CaO (1100 nm and 1400 nm ranges) generated significantly lesser hemolysis as compared to small size CaO particles (43 nm, 190 nm and 490 nm). It has never been found how the CaO particles induce the hemolysis. A lower concentration of the CaO ions can be observed where in vitro hemolysis occurs. The study by Garner et al. (1994) exemplified that the number of red blood cells was decreased to dramatic levels with 30 nm CaO Nps. The mechanism of the hemolytic action by nano sized CaO particles is elusive. Numerous articles reported numerous explanations of the hemolytic effects of nano-sized CaO particles including emission of CaO ions, high level of Ag particulates, direct contact of CaO nanoparticles with the red blood cells, or a combination of the methods. In a different study, mesoporous silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) and amorphous silica Nanoparticles (ASNs) hemolytic behavior was studied. ASNs produced 44 percent hemolysis, but a big amount of MSNs produced very less hemolysis under the same condition. Upon this discovery, it was concluded that MSNs were essentially safe, biodegradable, and may have diverse applications in bio technological and pharmaceutical applications.

Table 2.

Results of Hemolysis Activity for CaO NPs.

Table 2.

Results of Hemolysis Activity for CaO NPs.

| S. No |

Concentration of Plain CaONP (microgram per milliliter) |

Absorbance (%) |

Transmittance (%) |

Hemolysis (%) |

| 1. |

250 |

0.349 |

44.8 |

12.4 |

| 2. |

500 |

0.493 |

32.1 |

17.5 |

| 3. |

750 |

0.590 |

25.7 |

21.01 |

CaO nanoparticles (CaO Nps) cytotoxicity bioassay revealed that percentages of deaths were dependent on the concentration of CaO Nps. At various concentrations, the mortality was aggravated by the levels of CaO Nps. Our death rate also relied on the level of CaO Nps which indicated how many of them were present and on the duration it took during exposure. The death level increased considerably at varied levels after 24 hours of exposure. At various nanometers the death rate was 16 percent, 36.6 percent, 44.3 percent, 44.3 percent, 84.3 percent, 53.3 percent and 66.6 percent. The two days of treatment showed that the rate of death was 60 percent with a dose two nanometers, 83.3 percent with four nanometers dose, 86.6 with six nanometers dose, 91 with eight nanometers dose, 10 with nano meter quantity and 93 percent with 12 nanometers dose. The information is an indicator that 48 hours of contact death rate was two folds compared to the single day treatment. The brine shrimp cytotoxicity test devised by Michael et al. in 1956 and the study of the herbal isolates and fungus toxic compounds by Ghosh et al. and the study on the large metal toxicity by Saliba and Krzyz and the study of possible nanoscale cell toxicity in 2012 by Maurer-Jones et al., proved that cytotoxicity effect of CaO Nps is dependent on its concentration levels.

Table 3.

Results of Cytotoxicity Bioassay for CaO NPs.

Table 3.

Results of Cytotoxicity Bioassay for CaO NPs.

| S. No |

Concentration of Plain CaO NPs (microgram per milliliter) |

Total number of Nauplii |

Number of Living Nauplii |

Number of Dead Nauplii |

Death % |

| 1. |

1000 |

30 |

20 |

10 |

33.3 |

| 2. |

100 |

30 |

25 |

5 |

16.6 |

| 3. |

10 |

30 |

28 |

2 |

6.6 |

6. Conclusions

This paper shows that calcium oxide nanoparticle can be prepared by direct precipitation, which is a simple but efficient procedure of making nanoparticle of desired size. The production of these nanoparticles was confirmed by the XRD analysis, UV-Vis absorption and FTIR analysis. As the Calcium oxide nanoparticles have been identified, they possess numerous ecological activities such as antimicrobial activity against gram-negative bacteria. They could assist in coming up with new medicines to cure different disease-causing infections. Nevertheless, they are dangerous to ecology because of their hemolytic activity. But the silica coating has rendered them to be more biocompatible and fewer in hemolytic effects. Brine prawns were also proved to be biocompatible by a cytotoxicity test. The purpose of this study is to enhance other health systems and come up with new pharmaceuticals that can be used to heal, limited side effects and overall effectiveness.

References

- Feynman, R. , There’s plenty of room at the bottom, in Feynman and computation. 2018, CRC Press. p. 63-76.

- Laurent, S. , et al., Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2064–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, J.N., R. N. Tiwari, and K.S. Kim, Zero-dimensional, one-dimensional, two-dimensional and three-dimensional nanostructured materials for advanced electrochemical energy devices. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2012, 57, 724–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.-K. , et al., Cross-linked composite gel polymer electrolyte using mesoporous methacrylate-functionalized SiO2 nanoparticles for lithium-ion polymer batteries. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E. , et al., Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanocomposite nanoparticles for theranostic applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrak, H. , et al., Synthesis, characterization, and functionalization of ZnO nanoparticles by N-(trimethoxysilylpropyl) ethylenediamine triacetic acid (TMSEDTA): Investigation of the interactions between Phloroglucinol and ZnO@ TMSEDTA. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 4340–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansha, M. , et al., Synthesis of In2O3/graphene heterostructure and their hydrogen gas sensing properties. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 11490–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramacharyulu, P. , et al., Iron phthalocyanine modified mesoporous titania nanoparticles for photocatalytic activity and CO 2 capture applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 26456–26462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astefanei, A., O. Núñez, and M.T. Galceran, Characterisation and determination of fullerenes: a critical review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 882, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.S. , Carbon nanotubes? properties and applications: A review. Carbon Lett. 2013, 14, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqel, A. , et al., Carbon nanotubes, science and technology part (I) structure, synthesis and characterisation. Arab. J. Chem. 2012, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.A. , et al., Atomistic modelling of CVD synthesis of carbon nanotubes and graphene. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 6662–6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, K. and I. Khan, Preparation and characterization of single-walled carbon nanotube/nylon 6, 6 nanocomposites. Instrum. Sci. Technol. 2016, 44, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoy, J.M. , et al., A CO2 capture technology using multi-walled carbon nanotubes with polyaspartamide surfactant. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 2230–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabena, L.F. , et al., Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes as a metal catalyst support. Appl. Nanosci. 2011, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreaden, E.C. , et al., The golden age: gold nanoparticles for biomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2740–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmund, W. , et al., Processing and structure relationships in electrospinning of ceramic fiber systems. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C Thomas, S., P. Kumar Mishra, and S. Talegaonkar, Ceramic nanoparticles: fabrication methods and applications in drug delivery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 6165–6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. , et al., Synthesis, characterization, applications, and challenges of iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanotechnology, science and applications, 2016, 49-67.

- Hisatomi, T., J. Kubota, and K. Domen, Recent advances in semiconductors for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 7520–7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansha, M. , et al., Synthesis, characterization and visible-light-driven photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction of carbazole-containing conjugated polymers. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 10952–10961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.P. and K.E. Geckeler, Polymer nanoparticles: Preparation techniques and size-control parameters. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 887–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Ellah, N.H. and S.A. Abouelmagd, Surface functionalization of polymeric nanoparticles for tumor drug delivery: approaches and challenges. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2017, 14, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, M.K., A. Jain, and S. Singh, Studies on binary lipid matrix based solid lipid nanoparticles of repaglinide: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 2366–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaghi, S. , et al., Lipid nanotechnology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 4242–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujrati, M. , et al., Multifunctional cationic lipid-based nanoparticles facilitate endosomal escape and reduction-triggered cytosolic siRNA release. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 2734–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S. , Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2638–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshana, G. , et al., Synthesis of magnetite nanoparticles by top-down approach from a high purity ore. J. Nanomater. 2016, 16, 317–317. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigue, P. , et al., Top− down approach for the preparation of colloidal carbon nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 2984–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. , et al., A facile and universal top-down method for preparation of monodisperse transition-metal dichalcogenide nanodots. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5425–5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. , et al., Top-down preparation of active cobalt oxide catalyst. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6699–6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilevsky, G. , et al., Bottom-up synthesis of anatase nanoparticles with graphene domains. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 10638–10648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, D. , et al., Bottom up design of nanoparticles for anti-cancer diapeutics:“put the drug in the cancer’s food”. J. Drug Target. 2016, 24, 836–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. and Y. Xia, Bottom-up and top-down approaches to the synthesis of monodispersed spherical colloids of low melting-point metals. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 2047–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. and S. Ikram, Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles: a green approach. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2016, 161, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A. , et al., Advances in top–down and bottom–up surface nanofabrication: Techniques, applications & future prospects. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 170, 2–27. [Google Scholar]

- Eustis, S. and M.A. El-Sayed, Why gold nanoparticles are more precious than pretty gold: noble metal surface plasmon resonance and its enhancement of the radiative and nonradiative properties of nanocrystals of different shapes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M. , et al., Superparamagnetic Fe 3 O 4 nanoparticles: Synthesis by a solvothermal process and functionalization for a magnetic targeted curcumin delivery system. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 4480–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D., G. Xie, and J. Luo, Mechanical properties of nanoparticles: basics and applications. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2013, 47, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. , et al., Measuring thermal conductivity of fluids containing oxide nanoparticles. 1999.

- Loureiro, A. , et al., Albumin-based nanodevices as drug carriers. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 1371–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, P. , et al., Novel hydrophilic chitosan-polyethylene oxide nanoparticles as protein carriers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 63, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. and M. Saltzman, Engineering biodegradable nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery. Chem. Eng. Prog. 2013, 109, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Prashant, K., H. E. Ivan, and M. El-Sayed, Au nanoparticles target cancer. Nano Today 2007, 2, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- AshaRani, P. , et al., Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human cells. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, M.J. , et al., Antibacterial properties of nanoparticles. Trends Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q. , et al., Glucose-assisted transformation of Ni-doped-ZnO@ carbon to a Ni-doped-ZnO@ void@ SiO 2 core–shell nanocomposite photocatalyst. Rsc Adv. 2016, 6, 38653–38661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H., B. Wen, and R. Melnik, Relative importance of grain boundaries and size effects in thermal conductivity of nanocrystalline materials. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J., P. Takhistov, and D.J. McClements, Functional materials in food nanotechnology. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, R107–R116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.-M. , et al., Electrochemiluminescence resonance energy transfer system: mechanism and application in ratiometric aptasensor for lead ion. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 7787–7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unser, S. , et al., Localized surface plasmon resonance biosensing: current challenges and approaches. Sensors 2015, 15, 15684–15716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J. and R.W. Gentry, Environmental application and risks of nanotechnology: a balanced view, in Biotechnology and nanotechnology risk assessment: minding and managing the potential threats around us. 2011, ACS Publications. p. 41-67.

- Golobič, M. , et al., Upon exposure to Cu nanoparticles, accumulation of copper in the isopod Porcellio scaber is due to the dissolved Cu ions inside the digestive tract. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 12112–12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, S. , et al., Conjugation of biomolecules with luminophore-doped silica nanoparticles for photostable biomarkers. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 4988–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tratnyek, P.G. and R.L. Johnson, Nanotechnologies for environmental cleanup. Nano Today 2006, 1, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.C. and B. Nowack, Exposure modeling of engineered nanoparticles in the environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 4447–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozea, E.A. , et al., Tandem adsorption-photodegradation activity induced by light on NiO-ZnO p–n couple modified silica nanomaterials. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2017, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmala, A. , et al., Synthesis of silver nano particles and fabrication of aqueous Ag inks for inkjet printing. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 129, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaalan, M. , et al., Recent progress in applications of nanoparticles in fish medicine: a review. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, S., L. Brus, and C.B. Murray, Synthesis of monodisperse nanoparticles of barium titanate: toward a generalized strategy of oxide nanoparticle synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 12085–12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , et al., Metal-free efficient photocatalyst for stable visible water splitting via a two-electron pathway. Science 2015, 347, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. , et al., Piezoelectric nanowires in energy harvesting applications. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kot, M. , et al., Mechanical and tribological properties of carbon-based graded coatings. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 51–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Guangquan, et al. Fungus-mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Aspergillus terreus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 13, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, Mohamed, et al. Chemical composition, iron bioavailability, and antioxidant activity of Kappaphycus alvarezzi (Doty). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, J. Saraniya, and B. Valentin Bhimba. Silver nanoparticles: Antibacterial activity against wound isolates & invitro cytotoxic activity on Human Caucasian colon adenocarcinoma. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2012, 2, S87–S93. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, John H. , and Raoul J. Burchette. Prospective comparison of downward and lateral peritoneal dialysis catheter tunnel-tract and exit-site directions. Perit. Dial. Int. 2006, 26, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhumathi, K. , et al. Development of novel chitin/nanosilver composite scaffolds for wound dressing applications. J. Mater. Sci. : Mater. Med. 2010, 21, 807–813. [Google Scholar]

- Laloy, Julie, et al. Impact of silver nanoparticles on haemolysis, platelet function and coagulation. Nanobiomedicine 2014, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseichev, A. V. , et al. Effects of gold nanoparticles on erythrocyte hemolysis. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2014, 156, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Jonghoon, et al. Physicochemical characterization and in V itro hemolysis evaluation of silver nanoparticles. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 123, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, TaeWoo, et al. Optimizing hemocompatibility of surfactant-coated silver nanoparticles in human erythrocytes. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012, 12, 6168–6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopjani, Mentor, et al. Silver ion-induced suicidal erythrocyte death. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2009, 29, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asharani, P. V. , et al. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles in zebrafish models. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 255102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulvasu, Chinnasamy, et al. Toxicity effect of silver nanoparticles in brine shrimp Artemia. Toxicity effect of silver nanoparticles in brine shrimp Artemia. The Scientific World Journal 2014 ( 2014.

- Sarah, Quazi Sahely, Fatema Chowdhury Anny, and Mir Misbahuddin. Brine shrimp lethality assay. ||| Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. ||| 2017, 12, 186–189. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).