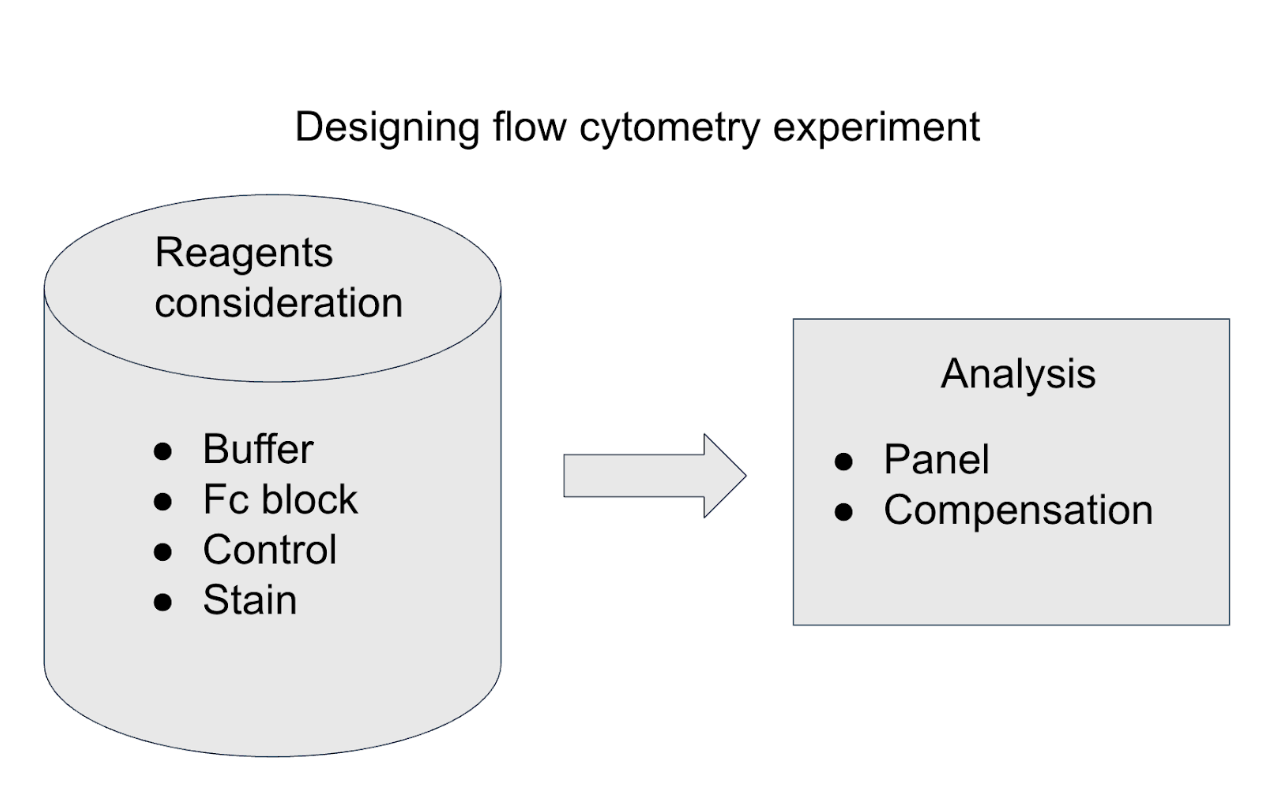

This review delineates the various reagents essential for the successful execution of flow cytometry experiments, including staining buffers, fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, viability dyes, and fixation/permeabilization solutions.

The review also discusses the computational aspects of flow cytometry, with particular emphasis on fluorescence compensation and the correction of spectral overlap between fluorochromes.

Lastly, the review discusses the implementation of appropriate controls—such as fluorescence minus one (FMO), isotype, unstained, and biological controls—to ensure data accuracy, validate staining specificity, and identify potential artifacts.

Specification Table:

| Subject area |

Immunology |

| More specific subject area |

Immuno techniques |

| Name of the reviewed methodology |

Flow Cytometry |

| Keywords |

Flow cytometry; buffer; stain; compensation; panel; controls |

| Resource availability |

|

| Review question |

What are the basic principles underlying flow cytometry, including forward and side scatter?

What are the critical components of a flow cytometry staining buffer and their respective functions?

Why is Fc receptor blocking important, and which cell types require it?

What types of controls are necessary in a flow cytometry experiment, and what are their specific roles?

What is fluorescence compensation, and why is it necessary in multicolor experiments?

How should fluorochromes be selected for panel design, and what instrument-related factors must be considered?

What are best practices for performing staining, including incubation conditions and dye titration? |

Background

Flow cytometry is a highly versatile and widely utilized technique in immunology, cell biology, and clinical diagnostics. It enables the rapid, quantitative, and multiparametric analysis of thousands of individual cells or particles in suspension. The technique is based on the use of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies that specifically bind to cellular proteins, allowing for the identification and characterization of distinct cell populations based on surface or intracellular markers. Beyond immunophenotyping, flow cytometry is widely applied to assess cellular functions such as proliferation, apoptosis, cytokine production, DNA content, cell cycle progression, and intracellular signaling events. DNA-binding dyes like propidium iodide, DAPI, and Hoechst 33342 are commonly used to evaluate nuclear content and chromatin status in these contexts.

Despite its powerful capabilities, flow cytometry requires meticulous planning and execution to ensure data accuracy and reproducibility. Critical experimental variables include the careful selection of fluorochromes, antibody clones, and appropriate buffers to minimize non-specific binding, signal loss, and interference. A major technical challenge in multicolor experiments is spectral overlap—the emission of multiple fluorochromes in overlapping detection channels. To address this, compensation is applied during data acquisition or analysis. Compensation is a correction technique used to subtract the overlapping fluorescence signals, ensuring that each fluorochrome is measured independently. Proper compensation is essential for reliable gating and accurate discrimination between cell populations.

The computational component of flow cytometry is also integral to experimental success. Data analysis typically involves compensation adjustment, gating strategies to define populations of interest, and basic quantitative assessments such as frequency, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), and histogram overlays. Software tools like FlowJo, FCS Express, and similar platforms are widely used for data visualization and interpretation. This review highlights the importance of understanding core computational steps—particularly compensation and gating—for meaningful analysis.

With the expansion of available fluorochromes, antibodies, and staining protocols, researchers—especially those new to the field—may find the design of effective flow cytometry experiments challenging. This review was written as a practical guide to assist such researchers in navigating the critical steps involved in setting up and analyzing a flow cytometry experiment. It discusses key reagents such as staining buffers, fluorophore-conjugated antibodies, viability dyes, and fixation/permeabilization solutions. In addition, the review outlines the essential use of controls, including unstained samples, isotype controls, and fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls, which help validate staining specificity and support accurate gating.

By integrating both experimental design and foundational analytical concepts, this guide aims to provide researchers with the tools and understanding necessary to perform robust and reproducible flow cytometry studies with greater confidence.

Method Details

Buffer:

The primary purpose of the staining buffer in flow cytometry is to optimize antibody binding while preserving cell viability and minimizing nonspecific interactions. A minimum volume of 100 µL of buffer per 1 × 10⁶ cells is recommended to reduce steric hindrance and facilitate efficient antibody access to cellular epitopes.

A typical staining buffer consists of several components, each serving a specific function:

Calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2–7.4) serves as the base medium, providing an isotonic and physiological environment that maintains cellular integrity. The absence of divalent cations (Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺) prevents cation-dependent cell aggregation and reduces cell-to-cell adhesion.

5–10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) or 0.5–1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) is added as a protein source to minimize nonspecific binding of antibodies to Fc receptors and to protect cells from stress-induced apoptosis during staining.

0.5–5 mM EDTA functions as a chelating agent that sequesters residual divalent cations, further reducing cell clumping by disrupting calcium-mediated adhesion.

DNase I is often included to degrade extracellular DNA released by dead or lysed cells, which can otherwise lead to cell aggregation and interfere with accurate flow analysis.

0.1–1% sodium azide (NaN₃) acts as a preservative to inhibit microbial growth during sample handling. Additionally, sodium azide prevents receptor internalization following antibody binding and may reduce photobleaching of fluorochromes during staining and acquisition.

Together, these buffer components contribute to optimal staining conditions by preserving cell morphology, ensuring uniform antibody binding, and reducing artifacts caused by clumping or nonspecific interactions.

Fc Block:

Many of the fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies used in flow cytometry are immunoglobulin-based and contain an Fc (fragment crystallizable) region. This Fc segment can non-specifically bind to Fc receptors (FcRs) expressed on various immune cells, leading to false-positive signals and misinterpretation of data. Fc receptor-mediated binding is particularly prevalent in cell types such as B lymphocytes, dendritic cells, monocytes, macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, human platelets, mast cells, and basophils, all of which express one or more classes of Fc receptors.

To mitigate this source of background staining, it is critical to incorporate an Fc receptor blocking step prior to antibody staining. Fc block reagents work by saturating Fc receptors, thereby preventing nonspecific antibody binding. The most common Fc blocking reagents are CD16 (FcγRIII) and CD32 (FcRγII). Human Fc blocking reagents also include CD64 (FcRγI).

Commercially available Fc blocking reagents typically contain monoclonal antibodies or recombinant proteins directed against these receptors. Their inclusion in the staining protocol significantly enhances the specificity of antibody binding and improves the accuracy of flow cytometric data, especially when analyzing FcR-expressing populations. [

1]

Controls:

In addition to biological controls such as positive, negative, and untreated samples, the inclusion of methodological controls is essential in flow cytometry to ensure the reliability, accuracy, and interpretability of the data. These controls help distinguish true signal from background, assess non-specific binding, and validate gating strategies.

A positive control typically involves single-stained samples, where different aliquots of the same cell population are each stained with one individual fluorochrome-conjugated antibody. These samples are used to verify proper fluorescence detection and accurate gating for each specific marker. Additionally, each single-stained aliquot functions as a negative control for all other markers in the multicolor panel, aiding in compensation and spillover assessment.

A common negative control in multicolor flow cytometry is the fluorescence minus one (FMO) control. In this control, all antibodies used in the panel are included except one, allowing for accurate identification of gating boundaries by revealing the contribution of background and spectral spillover from the other fluorophores. FMO controls are particularly valuable in complex panels where marker expression levels are dim or variable.

Another essential negative control is the unstained control, in which cells are processed without any fluorescent antibodies. This control is used to assess the level of autofluorescence and to establish baseline fluorescence for each detector channel, which is critical for proper gate setting.

An additional control is the isotype control, in which cells are stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies of the same isotype and species as the test antibodies, but lacking specificity for any cellular antigen. Isotype controls are used to evaluate non-specific binding of antibodies to Fc receptors or through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, helping to distinguish true antigen-specific staining from background signal.

Together, these method controls play a crucial role in validating the specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy of flow cytometric assays and should be integrated into experimental design, especially in studies involving novel markers, low-abundance targets, or unfamiliar cell populations [

2].

Stains:

The selection of staining reagents in flow cytometry is application-dependent and critical for accurately identifying the population of interest. Common staining agents include fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, DNA-binding dyes, viability dyes, ion-sensitive indicator dyes, and fluorescent reporter proteins [

3]. The choice of stains is influenced not only by their biological target but also by their spectral properties, particularly the spectral shift between stained and unstained (negative) populations. A greater spectral shift enhances signal resolution, facilitating clearer discrimination and more reliable identification of the target population.

To preserve fluorochrome integrity and minimize photobleaching, staining is typically performed in the dark and at low temperatures (commonly on ice or at 4°C). Incubation times generally range from 15 to 30 minutes, although this may vary depending on the dye and experimental requirements. Staining concentrations are often provided by the manufacturer but may also be empirically titrated, often using a 10-fold serial dilution. This is important because even small quantities of fluorochrome can effectively stain large numbers of cells, and excessive concentrations can lead to non-specific binding and elevated background signal.

Staining protocols may vary slightly depending on the type of dye, target molecule (e.g., surface vs. intracellular), and specific vendor recommendations. Therefore, adherence to the manufacturer’s specifications is essential for optimal staining performance and reproducibility across experiments.

Panel Design:

The initial discrimination of cell populations in flow cytometry is based on intrinsic physical characteristics, primarily evaluated through forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) parameters. FSC correlates with cell size, as it measures the light diffracted in the forward direction when a laser beam hits the cell. SSC, on the other hand, reflects internal granularity or complexity, capturing light scattered at a 90-degree angle due to intracellular structures such as granules or organelles. These scatter parameters are detected by photodetectors and translated into electronic signals, which are then analyzed using dedicated flow cytometry software for data interpretation.

In designing a multicolor panel, careful selection of fluorophores is essential. Each fluorochrome must be compatible with the excitation lasers and detector configuration of the flow cytometer. Most instruments employ a co-linear or parallel laser and detector arrangement, where lasers of specific wavelengths excite fluorochromes, and emitted light is captured by a set of optical filters and photodetectors. The choice of fluorophores must consider the emission spectra of each dye to minimize spectral overlap, which occurs when two fluorochromes emit light at similar wavelengths, leading to signal spillover.

To assess potential spectral overlap, the emission spectra of candidate fluorophores are compared to determine the extent of shared wavelengths between them. Selecting fluorophores with minimal spectral overlap for co-expression markers, and assigning brighter fluorophores to low-abundance targets, enhances resolution and ensures more accurate population discrimination. Additionally, the use of compensation and appropriate controls is necessary to correct for any unavoidable spectral spillover during analysis.

Effective panel design balances fluorophore brightness, spectral compatibility, marker expression levels, and instrument configuration to maximize sensitivity and minimize artifacts in multicolor flow cytometry experiments.

Compensation:

An essential consideration in multicolor flow cytometry is fluorescence compensation, a process used to correct for spectral overlap between fluorophores. Many fluorochromes have emission spectra that partially overlap, and without proper compensation, this overlap can result in signal spillover into adjacent detection channels, leading to inaccurate population identification. Compensation mathematically subtracts the overlapping signal from each detector to isolate the true fluorescence contribution of each individual marker, thereby allowing accurate delineation of distinct cell populations.

Modern flow cytometers are often equipped with automated compensation algorithms, but understanding the underlying principles remains important. Conceptually, compensation involves adjusting detector sensitivity, primarily through the photomultiplier tube (PMT) voltage, to fine-tune signal detection. Increasing the PMT voltage amplifies the fluorescence signal, which can enhance the resolution between populations, especially for dim markers. However, voltage adjustment itself does not reduce spectral overlap—instead, it improves signal-to-noise ratio and helps in optimal gating after compensation has been applied.

Proper compensation requires the use of single-stained controls for each fluorophore, enabling the system to calculate spillover coefficients accurately. Together with carefully chosen fluorochrome combinations and appropriate panel design, compensation ensures accurate and reproducible multicolor analysis.

Conclusions

Flow cytometry is an essential and powerful tool in immunology and cell biology for high-throughput, multiparametric analysis of heterogeneous cell populations. Its ability to detect and quantify a wide array of cellular markers, both surface and intracellular, relies on careful experimental design and rigorous methodological control. Key aspects such as buffer composition, appropriate staining conditions, and the use of viability and DNA-binding dyes play a critical role in maintaining cell integrity and ensuring specificity of signal. The incorporation of Fc receptor blocking steps is vital to prevent non-specific antibody binding, especially when analyzing immune cells with high Fc receptor expression.

Equally important is the inclusion of proper controls—such as single-stain, fluorescence minus one (FMO), unstained, and isotype controls—which are fundamental for setting accurate gates, evaluating background signal, and validating staining specificity. Fluorescence compensation is a critical step in multicolor experiments, allowing for correction of spectral overlap and ensuring accurate resolution of cell populations. Understanding the principles of laser excitation, detector arrangement, and spectral properties of fluorophores is essential during panel design to prevent signal spillover and optimize detection.

The complexity of flow cytometry demands a balance of technical knowledge and practical considerations. This review has outlined a step-by-step guide to help researchers design, optimize, and analyze flow cytometry experiments with precision. By integrating both experimental and analytical best practices, researchers can improve data quality, reproducibility, and ultimately the reliability of their scientific findings using this versatile technology.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Daëron, M. Fc receptor biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997, 15, 203–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maecker, H.T.; Trotter, J. Flow cytometry controls, instrument setup, and the determination of positivity. Cytometry A. 2006, 69, 1037–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnon, K.M. Flow Cytometry: An Overview. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2018, 120, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).