Submitted:

23 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Effectiveness of CRT

3. CRT Indications

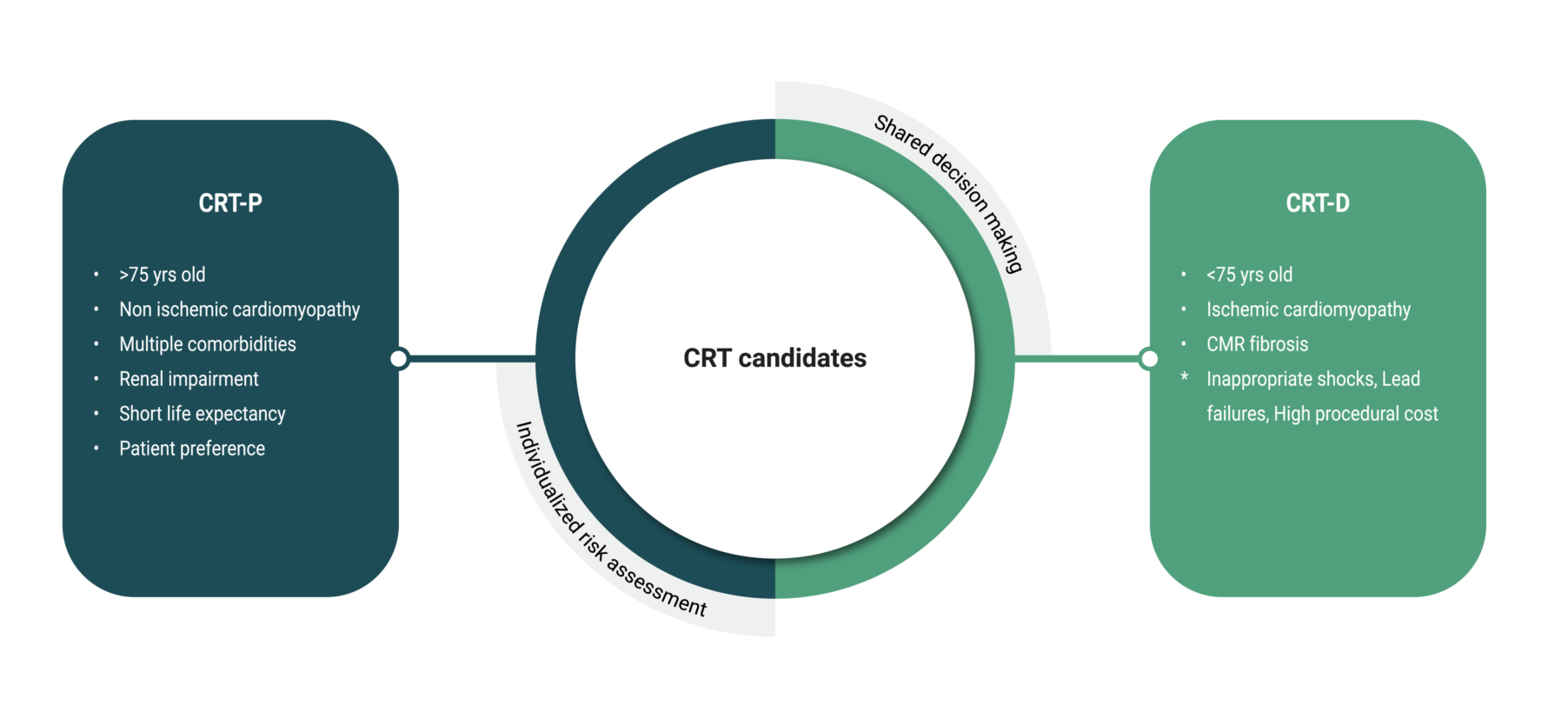

4. CRT-D or CRT-P

5. Our 2-Step Approach

6. CRT Non-Responders

7. Role of Conduction System Pacing

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRT | Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy |

| RCTs | Randomized clinical trials |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LBBB | Left bundle branch block |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| RV | Right ventricular |

| OGMT | Optimal guideline-directed medical therapy |

| PVS | Programmed ventricular stimulation |

| NIRFs | Non-invasive risk factors |

| NIPS | Non-invasive programmed stimulation |

| EP | Electrophysiology |

| SCD | Sudden cardiac death |

| SMVT | Sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia |

| CSP | Conduction system pacing |

| HBP | His bundle pacing |

| LBBAP | Left bundle branch area pacing |

| CMR | Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| NICM | Non ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| ICM | Ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| LGE | Late gadolinium enhancement |

| DCM | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

References

- Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J, Mohseni H, Hedgecott D, Crespillo AP, et al. Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population-based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet. 2018 Feb 10;391(10120):572–80.

- Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL. Risk factors for heart failure: a population-based case-control study. Am J Med. 2009 Nov;122(11):1023–8.

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Mar 3;141(9):e139–596.

- Leclercq C, Hare JM. Ventricular resynchronization: current state of the art. Circulation. 2004 Jan 27;109(3):296–9.

- Leclercq C, Kass DA. Retiming the failing heart: principles and current clinical status of cardiac resynchronization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 Jan 16;39(2):194–201.

- Cleland JGF, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, et al. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005 Apr 14;352(15):1539–49.

- Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004 May 20;350(21):2140–50.

- Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Klein H, Brown MW, Daubert JP, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 1;361(14):1329–38.

- Tang ASL, Wells GA, Talajic M, Arnold MO, Sheldon R, Connolly S, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 16;363(25):2385–95.

- Leyva F, Zegard A, Patel P, Stegemann B, Marshall H, Ludman P, et al. Improved prognosis after cardiac resynchronization therapy over a decade. Europace. 2023 Jun 2;25(6):euad141.

- Abraham WT, Fisher WG, Smith AL, Delurgio DB, Leon AR, Loh E, et al. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jun 13;346(24):1845–53.

- Linde C, Abraham WT, Gold MR, St John Sutton M, Ghio S, Daubert C, et al. Randomized trial of cardiac resynchronization in mildly symptomatic heart failure patients and in asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction and previous heart failure symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Dec 2;52(23):1834–43.

- Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, et al. The CARE-HF study (CArdiac REsynchronisation in Heart Failure study): rationale, design and end-points. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001 Aug;3(4):481–9.

- Cleland JGF, Freemantle N, Erdmann E, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L, et al. Long-term mortality with cardiac resynchronization therapy in the Cardiac Resynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012 Jun;14(6):628–34.

- Auricchio A, Stellbrink C, Sack S, Block M, Vogt J, Bakker P, et al. The Pacing Therapies for Congestive Heart Failure (PATH-CHF) study: rationale, design, and endpoints of a prospective randomized multicenter study. Am J Cardiol. 1999 Mar 11;83(5B):130D-135D.

- Cazeau S, Leclercq C, Lavergne T, Walker S, Varma C, Linde C, et al. Effects of multisite biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure and intraventricular conduction delay. N Engl J Med. 2001 Mar 22;344(12):873–80.

- Young JB, Abraham WT, Smith AL, Leon AR, Lieberman R, Wilkoff B, et al. Combined cardiac resynchronization and implantable cardioversion defibrillation in advanced chronic heart failure: the MIRACLE ICD Trial. JAMA. 2003 May 28;289(20):2685–94.

- Higgins SL, Hummel JD, Niazi IK, Giudici MC, Worley SJ, Saxon LA, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy for the treatment of heart failure in patients with intraventricular conduction delay and malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003 Oct 15;42(8):1454–9.

- Kindermann M, Hennen B, Jung J, Geisel J, Böhm M, Fröhlig G. Biventricular versus conventional right ventricular stimulation for patients with standard pacing indication and left ventricular dysfunction: the Homburg Biventricular Pacing Evaluation (HOBIPACE). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 May 16;47(10):1927–37.

- Hadwiger M, Dagres N, Haug J, Wolf M, Marschall U, Tijssen J, et al. Survival of patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without defibrillator: the RESET-CRT project. European Heart Journal. 2022 Jul 14;43(27):2591–9.

- Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, Michowitz Y, Auricchio A, Barbash IM, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 14;42(35):3427–520.

- Merkely B, Hatala R, Wranicz JK, Duray G, Földesi C, Som Z, et al. Upgrade of right ventricular pacing to cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure: a randomized trial. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 21;44(40):4259–69.

- Sideris S, Poulidakis E, Aggeli C, Gatzoulis K, Vlaseros I, Dilaveris P, et al. Upgrading pacemaker to cardiac resynchronization therapy: an option for patients with chronic right ventricular pacing and heart failure. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2014;55(1):17–23.

- Sridhar ARM, Yarlagadda V, Parasa S, Reddy YM, Patel D, Lakkireddy D, et al. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: US Trends and Disparities in Utilization and Outcomes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016 Mar;9(3):e003108.

- Yokoshiki H, Shimizu A, Mitsuhashi T, Furushima H, Sekiguchi Y, Manaka T, et al. Trends and determinant factors in the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy devices in Japan: Analysis of the Japan cardiac device treatment registry database. J Arrhythm. 2016 Dec;32(6):486–90.

- Banks H, Torbica A, Valzania C, Varabyova Y, Prevolnik Rupel V, Taylor RS, et al. Five year trends (2008-2012) in cardiac implantable electrical device utilization in five European nations: a case study in cross-country comparisons using administrative databases. Europace. 2018 Apr 1;20(4):643–53.

- Woods B, Hawkins N, Mealing S, Sutton A, Abraham WT, Beshai JF, et al. Individual patient data network meta-analysis of mortality effects of implantable cardiac devices. Heart. 2015 Nov 15;101(22):1800–6.

- Liang Y, Wang J, Yu Z, Zhang M, Pan L, Nie Y, et al. Comparison between cardiac resynchronization therapy with and without defibrillator on long-term mortality: A propensity score matched analysis. J Cardiol. 2020 Apr;75(4):432–8.

- Veres B, Fehérvári P, Engh MA, Hegyi P, Gharehdaghi S, Zima E, et al. Time-trend treatment effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without defibrillator on mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2023 Oct 5;25(10):euad289.

- Patel D, Kumar A, Black-Maier E, Morgan RL, Trulock K, Wilner B, et al. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy With or Without Defibrillation in Patients With Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2021 Jun;14(6):e008991.

- Køber L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, Haarbo J, Videbæk L, Korup E, et al. Defibrillator Implantation in Patients with Nonischemic Systolic Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 29;375(13):1221–30.

- Kutyifa V, Geller L, Bogyi P, Zima E, Aktas MK, Ozcan EE, et al. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy with implantable cardioverter defibrillator versus cardiac resynchronization therapy with pacemaker on mortality in heart failure patients: results of a high-volume, single-centre experience. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014 Dec;16(12):1323–30.

- Barra S, Boveda S, Providência R, Sadoul N, Duehmke R, Reitan C, et al. Adding Defibrillation Therapy to Cardiac Resynchronization on the Basis of the Myocardial Substrate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Apr 4;69(13):1669–78.

- Al-Sadawi M, Aslam F, Tao M, Salam S, Alsaiqali M, Singh A, et al. Is CRT-D superior to CRT-P in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy? International Journal of Arrhythmia. 2023 Feb 1;24(1):3.

- Cleland JGF, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, et al. Longer-term effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on mortality in heart failure [the CArdiac REsynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) trial extension phase]. Eur Heart J. 2006 Aug;27(16):1928–32.

- Gold MR, Daubert JC, Abraham WT, Hassager C, Dinerman JL, Hudnall JH, et al. Implantable defibrillators improve survival in patients with mildly symptomatic heart failure receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy: analysis of the long-term follow-up of remodeling in systolic left ventricular dysfunction (REVERSE). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013 Dec;6(6):1163–8.

- Gold MR, Linde C, Abraham WT, Gardiwal A, Daubert JC. The impact of cardiac resynchronization therapy on the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in mild heart failure. Heart Rhythm. 2011 May;8(5):679–84.

- de Waard D, Manlucu J, Gillis AM, Sapp J, Bernick J, Doucette S, et al. Cardiac Resynchronization in Women: A Substudy of the Resynchronization-Defibrillation for Ambulatory Heart Failure Trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019 Sep;5(9):1036–44.

- Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet. 2020 Sep 19;396(10254):819–29.

- McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11;371(11):993–1004.

- Pun PH, Al-Khatib SM, Han JY, Edwards R, Bardy GH, Bigger JT, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in CKD: a meta-analysis of patient-level data from 3 randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014 Jul;64(1):32–9.

- Theuns DAMJ, Schaer BA, Soliman OII, Altmann D, Sticherling C, Geleijnse ML, et al. The prognosis of implantable defibrillator patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy: comorbidity burden as predictor of mortality. Europace. 2011 Jan;13(1):62–9.

- Goldenberg I, Vyas AK, Hall WJ, Moss AJ, Wang H, He H, et al. Risk stratification for primary implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Jan 22;51(3):288–96.

- Leyva F, Zegard A, Okafor O, de Bono J, McNulty D, Ahmed A, et al. Survival after cardiac resynchronization therapy: results from 50 084 implantations. Europace. 2019 May 1;21(5):754–62.

- Wang Y, Sharbaugh MS, Althouse AD, Mulukutla S, Saba S. Cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemakers versus defibrillators in older non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2019;19(1):4–6.

- Döring M, Ebert M, Dagres N, Müssigbrodt A, Bode K, Knopp H, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in the ageing population - With or without an implantable defibrillator? Int J Cardiol. 2018 Jul 15;263:48–53.

- Acosta J, Fernández-Armenta J, Borràs R, Anguera I, Bisbal F, Martí-Almor J, et al. Scar Characterization to Predict Life-Threatening Arrhythmic Events and Sudden Cardiac Death in Patients With Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: The GAUDI-CRT Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Apr;11(4):561–72.

- Leyva F, Zegard A, Acquaye E, Gubran C, Taylor R, Foley PWX, et al. Outcomes of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy With or Without Defibrillation in Patients With Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Sep 5;70(10):1216–27.

- Gatzoulis KA, Tsiachris D, Arsenos P, Antoniou CK, Dilaveris P, Sideris S, et al. Arrhythmic risk stratification in post-myocardial infarction patients with preserved ejection fraction: the PRESERVE EF study. Eur Heart J. 2019 Sep 14;40(35):2940–9.

- Gatzoulis KA, Arsenos P, Trachanas K, Dilaveris P, Antoniou C, Tsiachris D, et al. Signal-averaged electrocardiography: Past, present, and future. J Arrhythm. 2018 Jun;34(3):222–9.

- Milaras N, Dourvas P, Doundoulakis I, Sotiriou Z, Nevras V, Xintarakou A, et al. Noninvasive electrocardiographic risk factors for sudden cardiac death in dilated ca rdiomyopathy: is ambulatory electrocardiography still relevant? Heart Failure Reviews. 2023;28(4):865–78.

- Stecker EC, Vickers C, Waltz J, Socoteanu C, John BT, Mariani R, et al. Population-based analysis of sudden cardiac death with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: two-year findings from the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Mar 21;47(6):1161–6.

- Gorgels APM, Gijsbers C, de Vreede-Swagemakers J, Lousberg A, Wellens HJJ. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest--the relevance of heart failure. The Maastricht Circulatory Arrest Registry. Eur Heart J. 2003 Jul;24(13):1204–9.

- Gatzoulis KA, Dilaveris P, Arsenos P, Tsiachris D, Antoniou CK, Sideris S, et al. Arrhythmic risk stratification in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: The ReCONSIDER study design - A two-step, multifactorial, electrophysiology-inclusive approach. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2021;62(2):169–72.

- Laina A, Gatzoulis KA, Soulaidopoulos S, Arsenos P, Doundoulakis I, Tsiachris D, et al. Time to reconsider risk stratification in dilated cardiomyopathy. Hellenic Journal of Cardiology. 2021;62(5):392–3.

- Doundoulakis I, Tsiachris D, Kordalis A, Soulaidopoulos S, Arsenos P, Xintarakou A, et al. Management of Patients With Unexplained Syncope and Bundle Branch Block: Predictive Factors of Recurrent Syncope. Cureus. 2023 Mar;15(3):e35827.

- Demir E, Köse MR, Şimşek E, Orman MN, Zoghi M, Gürgün C, et al. Comparative analysis of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator efficacy in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy in patients with heart failure. Sci Rep. 2025 Jul 9;15(1):24631.

- Frontera A, Prolic Kalinsek T, Hadjis A, Della Bella P. Noninvasive programmed stimulation in the setting of ventricular tachycardia catheter ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020 Jul;31(7):1828–35.

- Kariki O, Antoniou CK, Mavrogeni S, Gatzoulis KA. Updating the Risk Stratification for Sudden Cardiac Death in Cardiomyopathies: The Evolving Role of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. An Approach for the Electrophysiologist. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 Jul 31;10(8):541.

- Xintarakou A, Kariki O, Doundoulakis I, Arsenos P, Soulaidopoulos S, Laina A, et al. The Role of Genetics in Risk Stratification Strategy of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2022;23(9).

- Halliday BP, Gulati A, Ali A, Guha K, Newsome S, Arzanauskaite M, et al. Association Between Midwall Late Gadolinium Enhancement and Sudden Cardiac Death in Patients With Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Mild and Moderate Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction. Circulation. 2017 May 30;135(22):2106–15.

- Keil L, Chevalier C, Kirchhof P, Blankenberg S, Lund G, Müllerleile K, et al. CMR-Based Risk Stratification of Sudden Cardiac Death and Use of Implantable Cardioverter–Defibrillator in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jul 1;22(13):7115.

- Antonopoulos AS, Xintarakou A, Protonotarios A, Lazaros G, Miliou A, Tsioufis K, et al. Imagenetics for Precision Medicine in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2024 Apr;17(2):e004301.

- Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, Arbustini E, Barriales-Villa R, Basso C, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 1;44(37):3503–626.

- Gigli M, Merlo M, Graw SL, Barbati G, Rowland TJ, Slavov DB, et al. Genetic Risk of Arrhythmic Phenotypes in Patients With Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Sep 17;74(11):1480–90.

- Gasperetti A, Carrick RT, Costa S, Compagnucci P, Bosman LP, Chivulescu M, et al. Programmed Ventricular Stimulation as an Additional Primary Prevention Risk Stratification Tool in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy: A Multinational Study. Circulation. 2022 Nov 8;146(19):1434–43.

- Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M, Winkel BG, Behr ER, Blom NA, et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 2022 Oct 21;43(40):3997–4126.

- Trayanova NA, Popescu DM, Shade JK. Machine Learning in Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. Circ Res. 2021 Feb 19;128(4):544–66.

- Ellenbogen KA, Huizar JF. Foreseeing super-response to cardiac resynchronization therapy: a perspective for clinicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Jun 19;59(25):2374–7.

- Daubert C, Behar N, Martins RP, Mabo P, Leclercq C. Avoiding non-responders to cardiac resynchronization therapy: a practical guide. Eur Heart J. 2017 May 14;38(19):1463–72.

- Hummel JD, Coppess MA, Osborn JS, Yee R, Fung JWH, Augostini R, et al. Real-World Assessment of Acute Left Ventricular Lead Implant Success and Complication Rates: Results from the Attain Success Clinical Trial. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2016 Nov;39(11):1246–53.

- Pujol-Lopez M, Jiménez-Arjona R, Garre P, Guasch E, Borràs R, Doltra A, et al. Conduction System Pacing vs Biventricular Pacing in Heart Failure and Wide QRS Patients: LEVEL-AT Trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2022 Nov;8(11):1431–45.

- Antoniou CK, Chrysohoou C, Manolakou P, Tsiachris D, Kordalis A, Tsioufis K, et al. Multipoint Left Ventricular Pacing as Alternative Approach in Cases of Biventricular Pacing Failure. J Clin Med. 2025 Feb 7;14(4):1065.

- Dilaveris P, Antoniou CK, Chrysohoou C, Xydis P, Konstantinou K, Manolakou P, et al. Comparative Trial of the Effects of Left Ventricular and Biventricular Pacing on Indices of Cardiac Function and Clinical Course of Patients With Heart Failure: Rationale and Design of the READAPT Randomized Trial. Angiology. 2021 Nov;72(10):961–70.

- Herweg B, Sharma PS, Cano Ó, Ponnusamy SS, Zanon F, Jastrzebski M, et al. Arrhythmic Risk in Biventricular Pacing Compared With Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing: Results From the I-CLAS Study. Circulation. 2024 Jan 30;149(5):379–90.

- Fish JM, Brugada J, Antzelevitch C. Potential Proarrhythmic Effects of Biventricular Pacing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 Dec 20;46(12):2340–7.

- Nayak HM, Verdino RJ, Russo AM, Gerstenfeld EP, Hsia HH, Lin D, et al. Ventricular tachycardia storm after initiation of biventricular pacing: incidence, clinical characteristics, management, and outcome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008 Jul;19(7):708–15.

- Bradfield JS, Shivkumar K. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy–Induced Proarrhythmia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014 Dec;7(6):1000–2.

- Vouliotis AI, Tsiachris D, Dilaveris P, Sideris S, Gatzoulis KA. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy and Proarrhythmia: Weathering the Storm. Hospital Chronicles. 2012 Aug 24;7(4):234–40.

- Shukla G, Chaudhry GM, Orlov M, Hoffmeister P, Haffajee C. Potential proarrhythmic effect of biventricular pacing: fact or myth? Heart Rhythm. 2005 Sep;2(9):951–6.

- Deif B, Ballantyne B, Almehmadi F, Mikhail M, McIntyre WF, Manlucu J, et al. Cardiac resynchronization is pro-arrhythmic in the absence of reverse ventricular remodelling: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Res. 2018 Sep 1;114(11):1435–44.

- Wang Y, Zhu H, Hou X, Wang Z, Zou F, Qian Z, et al. Randomized Trial of Left Bundle Branch vs Biventricular Pacing for Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Sep 27;80(13):1205–16.

- Upadhyay GA, Vijayaraman P, Nayak HM, Verma N, Dandamudi G, Sharma PS, et al. His Corrective Pacing or Biventricular Pacing for Cardiac Resynchronization in Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jul 9;74(1):157–9.

- Vinther M, Risum N, Svendsen JH, Møgelvang R, Philbert BT. A Randomized Trial of His Pacing Versus Biventricular Pacing in Symptomatic HF Patients With Left Bundle Branch Block (His-Alternative). JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021 Nov;7(11):1422–32.

- Archontakis S, Sideris K, Laina A, Arsenos P, Paraskevopoulou D, Tyrovola D, et al. His bundle pacing: A promising alternative strategy for anti-bradycardic pacing - report of a single-center experience. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2022;64:77–86.

- Lustgarten DL, Crespo EM, Arkhipova-Jenkins I, Lobel R, Winget J, Koehler J, et al. His-bundle pacing versus biventricular pacing in cardiac resynchronization therapy patients: A crossover design comparison. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jul;12(7):1548–57.

- Vijayaraman P, Herweg B, Verma A, Sharma PS, Batul SA, Ponnusamy SS, et al. Rescue left bundle branch area pacing in coronary venous lead failure or nonresponse to biventricular pacing: Results from International LBBAP Collaborative Study Group. Heart Rhythm. 2022 Aug;19(8):1272–80.

- Vijayaraman P, Ponnusamy S, Cano Ó, Sharma PS, Naperkowski A, Subsposh FA, et al. Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing for Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: Results From the International LBBAP Collaborative Study Group. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021 Feb;7(2):135–47.

- Vijayaraman P, Sharma PS, Cano Ó, Ponnusamy SS, Herweg B, Zanon F, et al. Comparison of Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing and Biventricular Pacing in Candidates for Resynchronization Therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023 Jul 18;82(3):228–41.

- Leventopoulos G, Travlos CK, Anagnostopoulou V, Patrinos P, Papageorgiou A, Perperis A, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing Compared with Biventricular Pacing in Patients with Heart Failure Requiring Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2023 Nov 9;24(11):312.

- Vijayaraman P, Pokharel P, Subzposh FA, Oren JW, Storm RH, Batul SA, et al. His-Purkinje Conduction System Pacing Optimized Trial of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy vs Biventricular Pacing: HOT-CRT Clinical Trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2023 Dec;9(12):2628–38.

- Pujol-López M, Graterol FR, Borràs R, Garcia-Ribas C, Guichard JB, Regany-Closa M, et al. Clinical Response to Resynchronization Therapy: Conduction System Pacing vs Biventricular Pacing. CONSYST-CRT trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2025 May 1;S2405-500X(25)00187-2.

| Trial Name | Year | Population | Sample size | Comparison | Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PATH-CHF[15] | 1999 | NYHA III-IV | 42 | Univentricular pacing vs. BiVP | Trends for improvement regarding ˙VO2max and 6MWT |

| MUSTIC[16] | 2002 | NYHA III LVEF <35% QRS>150ms |

67 | BiVP vs. no pacing (sinus) BiVP vs. Univentricular (patients with Af) |

6MWT +20% VO2 max +10% LVEF +5% Mitral regurgitation improved by 45–50% |

| MIRACLE[11] | 2002 | NYHA III-IV LVEF ≤35% QRS >130 ms, |

453 | OMT vs CRT | Improved quality of life, 6MWT, NYHA class, LVEF |

| MIRACLE-ICD[17] | 2003 | NYHA III-IV LVEF ≤35% QRS >130 ms |

369 | BiVP+ICD vs. ICD | BiVP favorably affected quality of life, functional status, and exercise capacity No significant difference in LV function or survival |

| CONTAK-CD[18] | 2003 | NYHA) II -IV LVEF ≤35% QRS ≥120 ms |

490 | BiVP+ICD vs. ICD | 6MWT +20 m VO2max +0.8 mL/kg/min LVEF +2.3% |

| COMPANION[7] | 2004 | NYHA III-IV LVEF ≤35% QRS ≥120 ms |

1520 | OMT vs CRT/CRT-D | CRT-D reduced all-cause mortality by 36% CRT-P by 24% |

| CARE-HF[13] | 2005 | NYHA III-IV LVEF≤35% QRS ≥120 ms |

813 | OMT vs CRT | CRT-P reduced mortality and HF hospitalization |

| HOBIPACE[19] | 2006 | LVEF ≤40% Symptomatic bradycardia and impaired AV conduction |

33 | BiVP vs. Univentricular pacing | Favorable effects of BiVP on LV dimensions, LVEF, NT-proBNP levels, and functional status |

| MADIT-CRT[8] | 2009 | NYHA I-II LVEF ≤30% QRS ≥130 ms, |

1820 | CRT-D vs ICD | Reduced HF events and improved LV function, especially in LBBB |

| REVERSE[12] | 2008 | NYHA I-II LVEF ≤40% QRS ≥120 ms |

610 | OMT vs CRT | CRT-P improved LV function and reduced HF progression |

| RAFT[9] | 2010 | NYHA II-III LVEF ≤30% QRS ≥120 ms |

1798 | CRT-D vs ICD | CRT-D reduced mortality and HF hospitalizations |

| RESET-CRT[20] | 2023 | NYHA II-IV LVEF ≤35% QRS ≥120 ms |

3569 | CRT-P vs CRT-D | Non-inferior mortality with CRT-P vs CRT-D |

| Abbreviations: NYHA, New York Heart Association; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; HF, heart failure; MWT, minute walking distance; OMT, optimal medical treatment; CRT, cardiac resynchronization | |||||

| Study (Year) | Population | Study Period | Follow-up | CRT-P (n) | CRT-D (n) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | ||||||

| Køber (2016) | NICM | 2008-2014 | 67months (median) |

323 | 322 | No difference in all-cause mortality between patients who received CRT and patients who did not. |

| Doran (2021) | ICM and NICM | 2000–2002 | 16.5months (median) | 617 | 595 | The unadjusted and adjusted HRs for CRT-D versus CRT-P were both 0.84 (95% CI: 0.65-1.09) for all-cause mortality. NICM (n = 555): CRT-D reduced all-cause mortality compared to CRT-P (aHR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.34-0.86) ICM (n = 657): CRT-D did not reduce all-cause mortality (aHR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.77-1.44). |

| Observational studies | ||||||

|

Auricchio (2007) |

ICM and NICM | 1994–2004 | 34months (median) | 572 | 726 | CRT-D Non-significant decrease in mortality by 20% (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.58-1.17, p = 0.284) Significant decrease of sudden cardiac death (HR 0.04, 95% CI 0.04-0.28, p <0.002). |

|

Morani (2013) |

ICM and NICM | 2004–2007 | 55months (median) | 108 | 266 | CRT-D significantly reduced all-cause mortality compared to CRT-P (73 CRT-D and 44 CRT-P patients died, rate 6.6 vs. 10.4%/year; log-rank test, P = 0.020). |

|

Kutyifa (2014) |

ICM and NICM | 2000–2011 | 28months (median) | 693 | 429 | No mortality benefit in patients with CRT-D compared with CRT-P in the total cohort (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.73-1.32, P = 0.884). ICM: CRT-D was associated with 30% risk reduction in all-cause mortality compared with CRT-P (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.51-0.97, P = 0.03). NICM: No mortality benefit of CRT-D over CRT-P (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.73-1.32, P = 0.894). |

|

Looi (2014) |

ICM and NICM | 2006–10 | 29months (mean) | 354 | 146 | CRT-D did not offer additional survival advantage over CRT-P |

| Gold (2015) | ICM and NICM | 2004–06 | 60months (median) | 74 | 345 | 10% mortality among CRT-D patients and 11.8% among CRT-P patients. CRT-ON was predicted to increase survival 22.8% (CRT-ON 52.5% vs. CRT-OFF 29.7%; HR 0.45; p = 0.21), leading to expected survival of 9.76 years (CRT-ON) versus 7.5 years (CRT-OFF). |

| Marijon (2015) | ICM and NICM | 2008–10 | 222months (mean) | 535 | 1,170 | Increased mortality rate among CRT-P patients compared with CRT-D (relative risk 2.01, 95% CI 1.56–2.58). 95% of the excess mortality among CRT-P subjects was related to an increase in non-sudden death. |

|

Reitan (2015) |

ICM and NICM | 1999–12 | 59months (median) | 448 | 257 | Annual mortality differed between CRT-D and CRT-P (5.3% and 11.8%, respectively) After adjustment for covariates, CRT-D treatment (vs CRT-P) was not associated with better long-term survival. |

| Munir (2016) | ICM and NICM | 2002–13 | 40.8months (median) | 107 | 405 | CRT-P patients had higher unadjusted mortality compared to CRT-D (HR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.15–2.08, P = 0.004). After adjustment (age at implant, sex, prior myocardial infarction, Charlson index, pre-implant LVEF, QRS morphology, drugs) this effect lost statistical significance (HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.78–1.77, P = 0.435) |

|

Witt (2016) |

ICM and NICM | 2000–10 | 48months (median) |

489 | 428 | CRT-D reduced all-cause mortality in ICM (aHR 0.74, 95% CI, 0.56–0.97; P = 0.03) but not in NICM (aHR 0.96, 95% CI, 0.60–1.51; P = 0.85) |

|

Drozd (2016) |

ICM and NICM | 2008–12 | 36months (mean) | 544 | 251 | No survival benefit in CRT-D patients compared with CRT-P (HR 1.09, 95% CI 0.84-1.41, P = 0.51). |

| Laish-Farkas (2017) | Elderly with ICM and NICM | 2006–15 | 60months (median) |

142 | 104 | In octogenarians CRT-P is associated with similar morbidity and mortality outcomes as CRT-D. |

| Barra (2017) | ICM and NICM | 2002–12 | 41.4months (mean) | 1,270 | 4,037 | ICM: better survival with CRT-D vs CRT-P (HR 0.76; 95% CI: 0.62-0.92, P = 0.005) NICM: no such difference was observed (HR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.73-1.16, P = 0.49). |

| Martens (2017) | ICM and NICM | 2008–15 | 38months (mean) | 361 | 326 | All-cause mortality was higher in patients with CRT-P versus CRT-D (21% vs 12%, p=0.003), even after adjusting for baseline characteristics (HR 2.5; 95% CI 1.36-4.60, P=0.003). Predominant non-cardiac mode of death in CRT-P recipients (n=47 (71%) vs n=13 (38%) in CRT-D, P=0.002). |

| Yokoshiki (2017) | ICM and NICM | 2011–15 | 21months (mean) | 97 | 620 | All-cause death or heart failure hospitalization diverged between the CRT-D and CRT-P groups with a rate of 22% vs. 42%, respectively, at 24 months (P=0.0011). However, this apparent benefit of CRT-D over CRT-P was no longer significant after adjustment for covariates. |

|

Leyva (2018) |

ICM and NICM | 2000–17 | 56.4months (median) | 999 | 551 | CRT-D was associated with a lower total mortality (HR 0.72) ICM: CRT-D was associated with a lower total mortality (HR 0.62), total mortality or HF hospitalization (HR 0.63), and total mortality or hospitalization for MACE (HR 0.59) (all P < 0.001) NICM: No differences in outcomes between CRT-D and CRT-P |

|

Döring (2018) |

Elderly with ICM and NICM | 2008–14 | 26months (mean) | 80 | 97 | No significant difference in mortality between the two groups (P= 0.562) |

|

Wang (2019) |

NICM | 2002–13 | 46months (median) | 42 | 93 | CRT-P recipients had similar unadjusted mortality compared to CRT-D recipients (HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.56-1.93) Unchanged after adjusting for unbalanced covariates (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.47-1.89) (LVEF, drugs, comorbidities) |

|

Saba (2019) |

NICM | 2007–14 | 60months | 1,236 | 4,359 | No difference between matched CRT-P and CRT-D recipients regarding the time to all-cause mortality (HR 0.90; 95% CI 0.74-1.09), any hospitalization (HR 1.13; 95% CI 0.98-1.30), and cardiac hospitalization (HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.83-1.17). CRT-P recipients had significantly lower medical costs at 12 and 24 months. |

|

Barra (2019) |

ICM and NICM | 2002–13 | 30months (mean) | 534 | 1,241 | ICM: better survival with CRT-D vs CRT-P (HR for mortality adjusted on propensity score and all mortality predictors: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.62 to 0.92; p = 0.005) NICM: no such difference was observed (HR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.73 to 1.16; p = 0.49). |

| Leyva (2019) | 2009–17 | 32.4months (median) | 24,811 | 25,273 | Excess mortality was lower after CRT-D than after CRT-P in all patients (aHR 0.80, 95% CI 0.76-0.84] in subgroups with (aHR 0.79, 95% CI 0.74-0.84) or without (aHR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74-0.91) ICM |

|

| Liang (2020) | ICM and NICM | 2005–16 | 36 months (median) | 126 | 219 | No significant difference in the risk of mortality between CRT-D and CRT-P groups (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.70-1.40, P= 0.95]. No significant difference between CRT-D and CRT-P in reducing mortality was observed in any pre-specified subgroups. |

|

Gras (2020) |

ICM and NICM | 2010–17 | 913 ± 841 days | 19,266 | 26,431 | Higher all-cause mortality in CRT-P (11.6%) than CRT-D patients (6.8%) (HR 1.70, 95% CI 1.63-1.76, P < 0.001). No difference in mortality in NICM patients >75 years old with CRT-P and CRT-D (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.80-1.09, P = 0.39). Higher mortality in NICM CRT-P patients <75 years old (HR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03-1.45, P = 0.02). Higher mortality with CRT-P than with CRT-D irrespectively of age in patients with ICM (<75 years old: HR 1.22, 95% CI 1.08-1.37, P = 0.01; ≥75 years old: HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.04-1.22, P = 0.003). |

| Huang (2021) | ICM and NICM | 2012–13 | 27.7months (mean) | 237 | 362 | SCD rate was 8.0% in CRT-P group and 3.3% in CRT-D group No significant differences in all-cause death rate between the CRT-D and CRT-P groups (CRT-D vs. CRT-P, 20.4% vs. 19.4%, P = 0.840). |

| Schrage (2022) | ICM and NICM | 2000–16 | 28.2months (median) | 880 | 1,108 | CRT-D was associated with lower 1- and 3-year all-cause mortality (HR:0.76, 95% CI:0.58-0.98; HR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.68-0.99, respectively). |

|

Hadwiger (2022) |

ICM and NICM | 2014–19 | 28.2months (median) |

847 | 2,722 | CRT-P treatment was not associated with inferior survival compared with CRT-D. |

| Farouq (2023) | NICM | 2005-2020 | 51.6months (median) | 2334 | 1693 | CRT-D was associated with higher 5-year survival (HR 0.72 95% CI 0.61–0.85, P < 0.001). CRT-P was associated with higher mortality in age groups <60 years and 70–79 years. |

| Abbreviations: ICM, ischemic cardiomyopathy; NICM, non-ischemic cardiomyopathy; SCD, sudden cardiac death; HF, heart failure; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval | ||||||

| Meta-analysis (year) | No of studies included | Population (n) | CRT-P (n) | CRT-D (n) |

Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy | |||||

| Veres (2023) |

26 observational studies | 128.030 | 55.469 | 72.561 | CRT-D reduced all-cause mortality by 20% over CRT-P (aHR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.76–0.94; P < 0.01] Not in NICM (HR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.79–1.15; P = 0.19) Not in patients >75 years (HR: 1.08; 95% CI 0.96–1.21; P = 0.17). |

| Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy | |||||

|

Patel (2021) |

7 observational studies | 9.944 | 3.079 | 6.865 | CRT-D was not significantly associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality in CRT-eligible patients with NICM (aHR 0.92, 95% CI, 0.83–1.03) |

| Al Sadawi (2023) | 13 observational and 2 RCTs | 22.763 | 9.596 | 13.167 | CRT-D was associated with lower all-cause mortality (log HR − 0.169, SE 0.055; P = 0.002) as compared to CRT-P. |

|

Liu (2023) |

9 observational and 2 RCTs | 28.768 | 11.980 | 16.788 | CRT-D was associated with a modest but statistically significant survival benefit compared to CRT-P (aHR 0.90 95% CI, 0.81–0.99) |

|

Neto (2024) |

11 observational and 2 RCTs | 61.326 | 7.338 | 9.108 | CRT-D was associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality compared to CRT-P (pooled HR 0.74; 95% CI: 0.62-0.88; I2=84%). No statistically significant difference in mortality risk for patients > 75 years old (pooled HR 0.96; 95% CI: 0.811-1.15; I² = 39%, P<0.001). |

| Abbreviations: RCTs, randomized clinical trials; ICM, ischemic cardiomyopathy; NICM, non-ischemic cardiomyopathy; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval | |||||

| Trial Name | Year | Study Type | Population | Intervention | Comparator | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| His-SYNC[83] | 2017 | RCT | 41 | HBP | BiV CRT | Similar improvements in LV function; HBP had higher crossover (48%) due to technical limitations. |

| His-Alternative[84] | 2021 | RCT | 50 | HBP or LBBAP | BiV CRT | CSP showed non-inferior clinical response and better electrical resynchronization. |

| LBBP-RESYNC[82] | 2022 | RCT | 40 | LBBAP | BiV CRT | LBBAP showed greater LVEF improvement and QRS narrowing than BiV CRT. |

| HOT CRT[91] | 2023 | RCT | 160 | HBP | BiV CRT | HBP superior to BiVP in LVEF; similar QRS narrowing and symptoms |

| LEVEL-AT[72] | 2023 | Prospective, non-randomized | 70 | LBBAP | CRT cohort | LBBAP showed better LVEF recovery and symptom improvement compared to historical BiV CRT. |

| CONSYST CRT[92] | 2025 | RCT | 134 | CSP | BiV CRT | Non inferiority in clinical and echocardiographic response |

| Abbreviations: RCT, randomized clinical trial; HBP, his bundle pacing; LBBAP, left bundle brunch area pacing; BiV, biventricular; CSP, conduction system pacing; CRT, cardiac resynchronization, LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LV, left ventricular | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).