1. Introduction

With the rapid evolution of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, its significance has been steadily rising across military, civilian, and commercial domains. In modern warfare especially, UAVs have transitioned from auxiliary roles to primary combat platforms, profoundly reshaping combat models and battlefield dynamics [

1,

2,

3]. Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI), low-cost manufacturing, and stealth flight technology have endowed various unmanned systems with enhanced perception, autonomous decision-making, and strike capabilities. A representative case is the "Operation Spider's Web" launched by Ukraine in June 2025: Ukrainian forces covertly deployed 117 FPV kamikaze drones deep within Russian strategic zones, coordinating the destruction of multiple high-value targets. This operation inflicted severe damage on Russia's airborne nuclear deterrent system — at a cost of merely a few thousand dollars per drone — and exposed the critical failure of existing defense systems against attacks employing "low-slow-small UAVs + AI swarms + covert delivery" tactics. This incident highlighted both the increasingly complex combat capabilities of unmanned systems and the urgent demand for advancements in target detection, path planning, and low-latency response mechanisms.

Currently, the development of unmanned systems technology exhibits two prominent trends. On one hand, AI-empowered intelligent systems are breaching the traditional OODA (Observe–Orient–Decide–Act) response loop, demonstrating AI swarm-driven closed-loop operational capabilities in real combat scenarios. On the other hand, adversaries are developing more sophisticated counter-UAV strategies, including communication jamming, deception interference, and terrain-based evasion tactics [

4,

5]. Within this technological contest, enhancing the perception capability of unmanned systems—ensuring high efficiency, stability, and low power consumption—has become a pivotal tactical breakthrough point.

Compared to conventional ground-based fixed observation platforms, airborne perception systems integrate visual ranging functions directly onto UAV platforms, achieving mobile and real-time sensing. Airborne platforms allow closer proximity to targets, enable dynamic close-range tracking, and support complex tasks such as autonomous obstacle avoidance, formation coordination, and precision strikes—significantly enhancing autonomous operational capabilities [

2]. However, airborne deployment also imposes stringent demands on system lightweight design, low power consumption, and real-time responsiveness, driving researchers to develop visual ranging and target detection algorithms optimized for embedded edge computing platforms. Advancing efficient and reliable airborne visual ranging systems is not only a key technology for UAV intelligence upgrades but also a core enabler for enhancing future unmanned combat effectiveness and survivability.

At present, mainstream ranging methods include radar [

6], laser [

7], ultrasonic [

8], and visual ranging [

9]. While radar and laser offer high precision and long detection ranges, their bulky size, high power consumption, and cost render them unsuitable for small UAV applications. Visual ranging, with its non-contact nature, low cost, and ease of integration, has become a research focus for lightweight perception systems. Based on camera configurations, visual ranging can be categorized into binocular and monocular systems. Binocular vision offers higher accuracy but requires extensive calibration and disparity computation resources [

10,

11]. In contrast, monocular vision—with its simple hardware structure and algorithmic flexibility—has emerged as the preferred solution for edge and embedded platforms [

12,

13].

Monocular visual ranging methods fall into two categories: depth map estimation and physical distance regression. The former relies on convolutional neural networks to generate relative depth maps, which are suitable for scene modeling but lack direct physical distance outputs [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The latter directly outputs target distances based on geometric modeling or end-to-end regression, offering faster and more practical responses. Geometric modeling approaches, such as perspective transformation, inverse perspective mapping (IPM), and similar triangle modeling, estimate depth by mapping pixel data to physical parameters [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. In recent years, deep learning techniques have been introduced to monocular ranging models to enhance adaptability in unstructured environments [

26]. Traditional two-stage detection algorithms such as RCNN [

27], Fast R-CNN [

28], and Faster R-CNN [

29] excel in detection accuracy but are limited by their complex architectures and high computational demands—making them less suitable for edge platforms that require low power and real-time performance, thus restricting their practical applications in UAV scenarios.

In the field of target detection, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) family of algorithms has gained widespread use in unmanned systems due to its fast detection speed and compact architecture, ideal for edge deployment [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. To enhance small-object detection and long-range recognition on embedded platforms, researchers have proposed various improvements based on YOLOv5, YOLOv8, and YOLOv11, incorporating lightweight convolutions, attention mechanisms, and feature fusion modules [

42,

43,

44,

45]. However, most existing studies focus on ground-based or general-purpose deployments and lack systematic research on lightweight airborne deployment and integrated perception-ranging systems. Particularly on ultra-low-power, computation-constrained mobile platforms, balancing detection accuracy, ranging stability, and frame rate remains a critical unresolved challenge. Reference [

46] explored a low-power platform based on Raspberry Pi combined with YOLOv5 for real-time UAV target detection. Although it did not deeply address deployment efficiency and response latency, it provided a valuable reference for lightweight applications.

To this end, this study expands the research perspective and application scope of UAV visual perception. Transitioning from traditional ground-based observation models to onboard autonomous sensing, we propose a lightweight airborne perception system mounted directly on UAV platforms. This system is designed to meet the integrated requirements of target detection and distance measurement, achieving real-time, in-flight optimization of both functionalities. The main innovations and contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

1. Lightweight Detection Architecture Design: Based on the YOLOv11n model, this study introduces the C3GHOST and ADown modules to construct an efficient detection architecture tailored for edge computing platforms. The C3GHOST module reduces computational overhead through lightweight feature fusion while enhancing feature representation capability. The ADown module employs an efficient down-sampling strategy that lowers computational cost without compromising detection accuracy. Systematic evaluation on a custom-built dataset demonstrates the model’s capability for joint optimization in terms of frame rate and ranging precision.

2. Target Tracking Optimization: To further improve the stability of UAV target tracking, this study incorporates the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) approach. EKF performs target position estimation and trajectory prediction in dynamic environments, significantly reducing position jitter and sporadic false detections during the tracking process, thereby enhancing robustness and consistency.

3. Dataset Expansion: Based on a publicly available dataset from CSDN, this study conducts further expansion by constructing a comprehensive dataset that covers a wide range of UAV models and complex environments. The dataset includes image samples captured under varying flight altitudes, viewing angles, and lighting conditions. This expansion enables the proposed model to adapt not only to different types of UAV targets, but also to maintain high detection accuracy and stability in complex flight environments.

4. Model Conversion and Deployment on Edge Devices: To facilitate practical deployment, the trained model was converted from its standard format to a format compatible with edge computing devices based on the RK3588S chipset. The converted model was successfully deployed onto the edge platform, ensuring efficient operation on resource-constrained hardware.

2. Methodology

2.1. ADG-YOLO

2.1.1. Basic YOLOv11 Algorithm

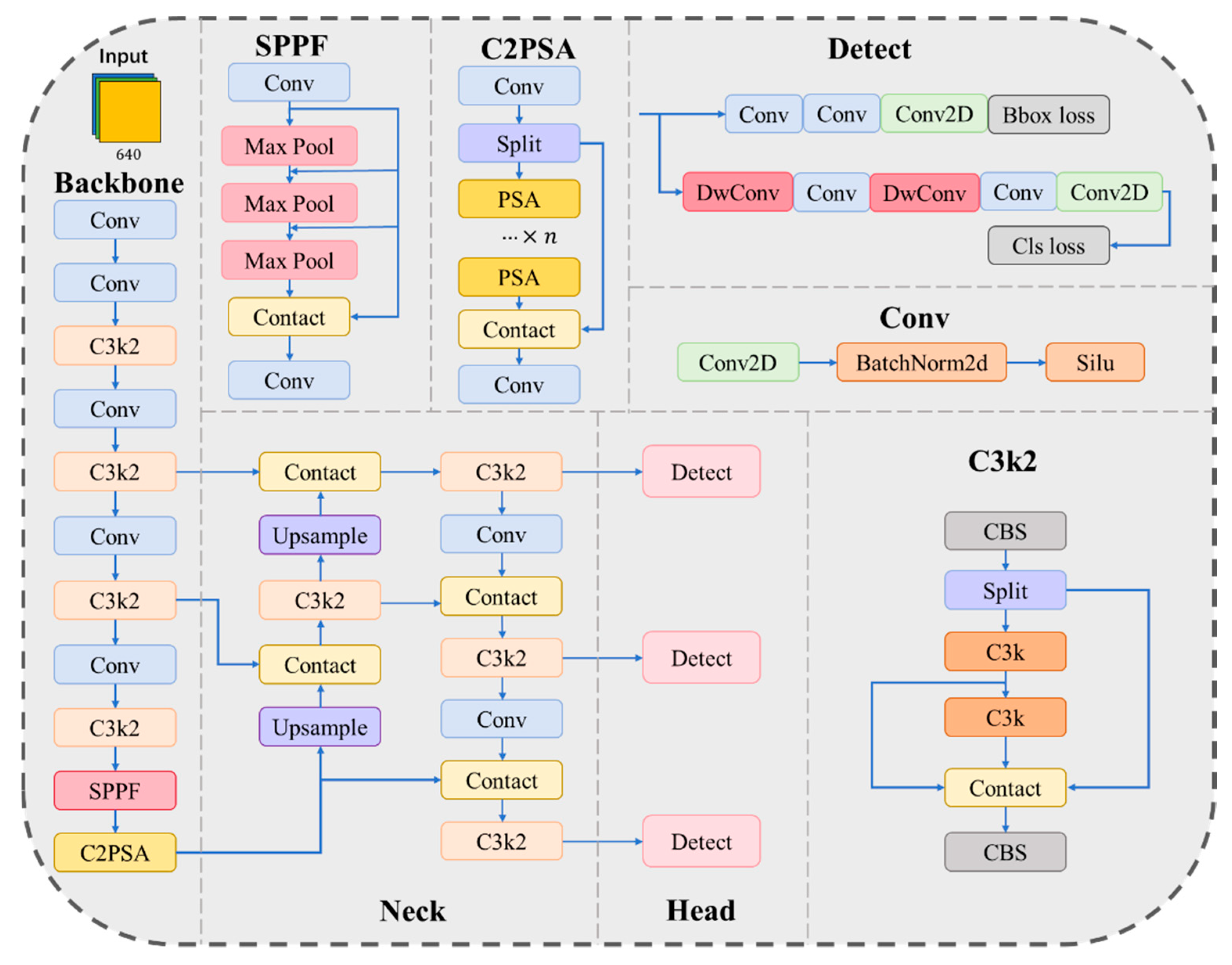

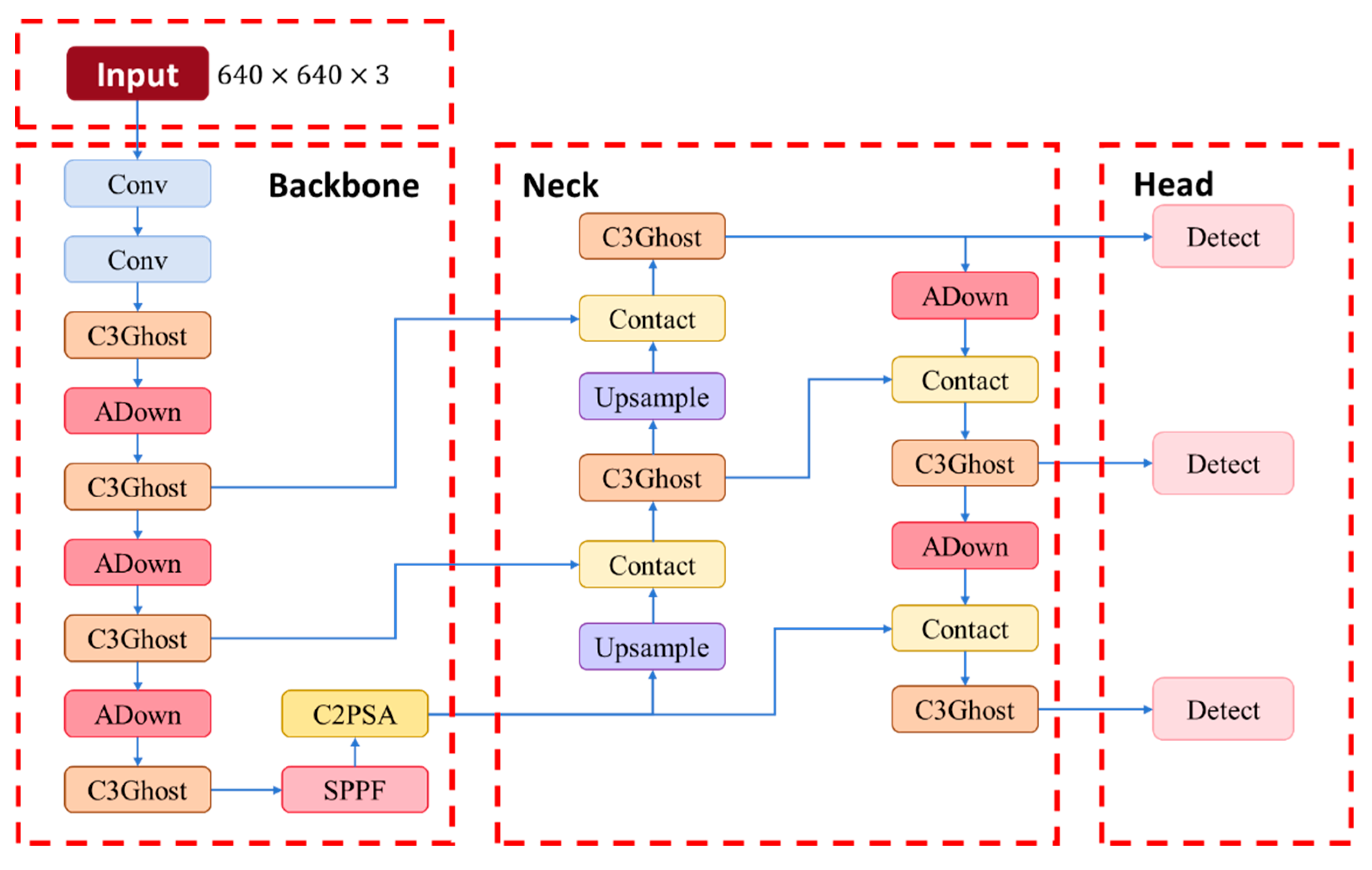

YOLOv11n is the most lightweight nano version within the Ultralytics YOLOv11 series, implemented using the Ultralytics Python package (e.g., v11.0). In this study, we adopt the official release version 8.3.31. The network architecture is illustrated in

Figure 1. To enhance detection performance in lightweight configurations, YOLOv11n comprehensively replaces the C2f modules used in YOLOv8n with unified C3k2 modules (Cross-Stage Partial with kernel size 2) across the entire architecture. This modification enables efficient feature extraction via a series of small-kernel convolutions while maintaining parameter efficiency, thereby significantly improving feature representation and receptive field capacity.

In the backbone, after extracting high-level semantic features, an SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling–Fast) module is introduced to integrate multi-scale contextual information. Subsequently, a C2PSA (Cross-Stage Partial with Spatial Attention) module is appended to enhance feature responses in critical spatial regions via a spatial attention mechanism, thereby improving recognition of small and partially occluded targets. The neck adopts a standard upsampling and feature concatenation strategy, with additional C3k2 modules embedded to reinforce cross-scale feature fusion. Finally, in the detection head, the architecture combines C3k2 and conventional layers to generate bounding box and class predictions. The overall model maintains a compact size of approximately 6.5M parameters, achieving both efficient inference and high detection accuracy.This architectural design endows YOLOv11n with enhanced multi-scale and spatial awareness capabilities while preserving its lightweight nature. Notably, it delivers significant improvements in small object detection accuracy compared to YOLOv8n.

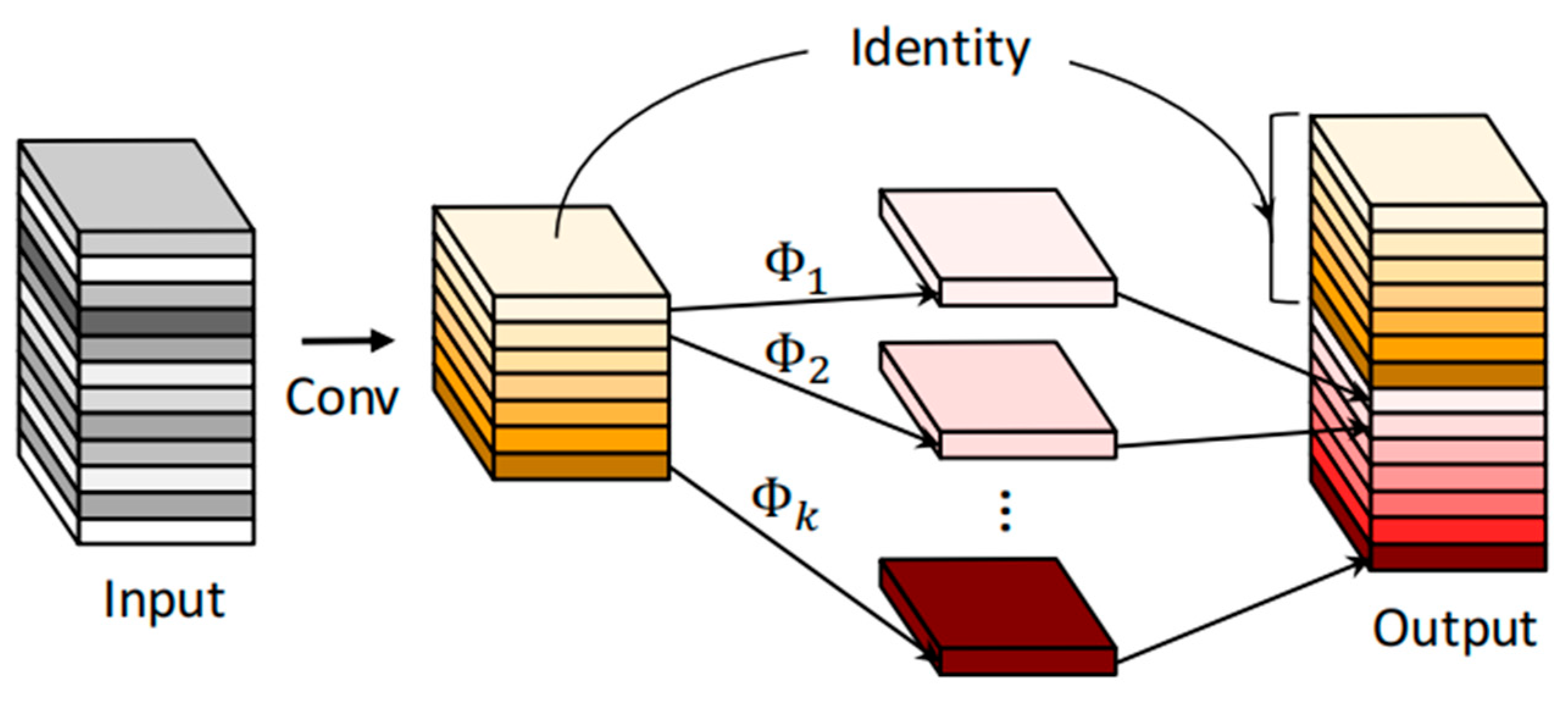

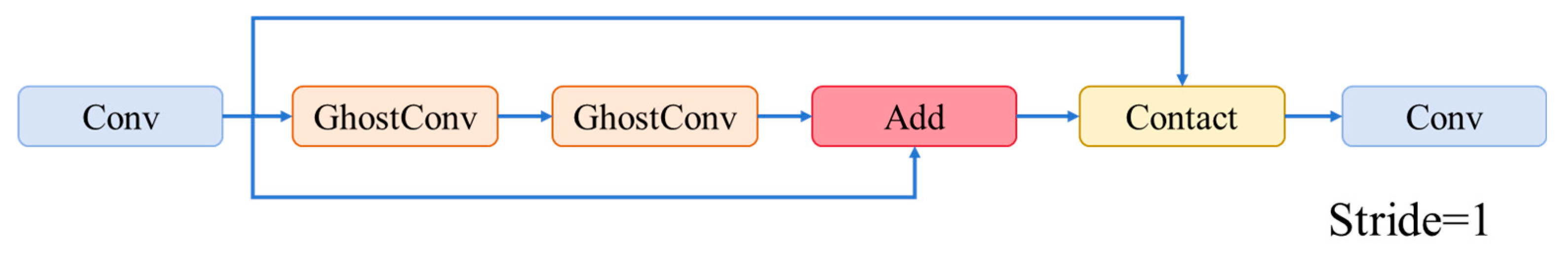

2.1.2. C3Ghost

In this study, the standard C3k2 modules are replaced with C3Ghost modules to achieve a more lightweight design and improved computational efficiency in feature fusion. The C3Ghost module consists of a series of GhostConv layers integrated within a Cross-Stage Partial (CSP) architecture, combining efficient information flow with compact network structure [

47]. As shown in

Figure 2, GhostConv divides the input feature map into two parts: the first part generates primary features using standard convolution, while the second part produces complementary “ghost” features through low-cost linear transformations such as depthwise separable convolutions. These two parts are then concatenated to form the final output. By exploiting the inherent redundancy in feature representations, this design significantly reduces the number of parameters and floating-point operations, while retaining a representational capacity comparable to conventional convolutions.

On this basis, C3Ghost integrates multiple GhostConv layers into the CSP structure to form a lightweight feature fusion unit. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the input is split into two parallel branches. One branch extracts higher-level features through a series of stacked GhostBottleneck layers, and the other directly passes the input via a shortcut connection to preserve original information. The outputs from both branches are then concatenated and fused using a 1×1 convolution. This design enhances feature representation while keeping computational cost and model complexity to a minimum [

48].

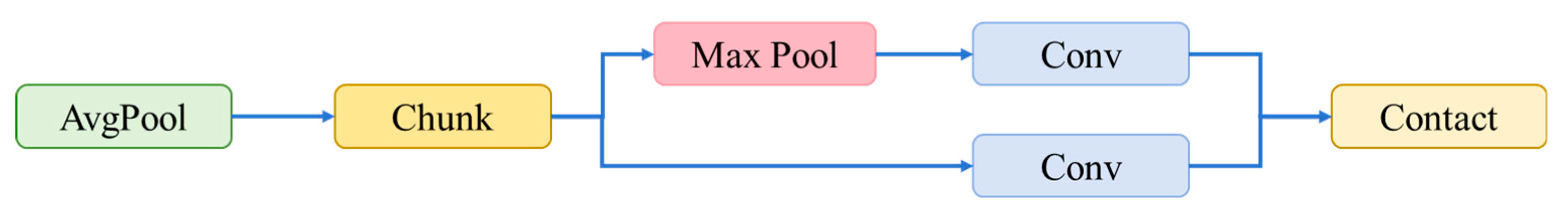

2.1.3. ADown

In this study, an ADown module is introduced to replace conventional convolution-based downsampling operations, aiming to improve efficiency while preserving fine-grained feature information. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the core design of ADown consists of the following stages: the input feature map is first processed through average pooling and downsampled to half the spatial resolution. It is then split into two branches along the channel dimension. The first branch applies a 3×3 convolution to extract local detail features, while the second branch undergoes max pooling for downsampling, followed by a 1×1 convolution for channel compression and nonlinear transformation. Finally, the outputs from both branches are concatenated along the channel axis to form the downsampled output [

49].

Compared to standard convolution or conventional pooling-based downsampling, ADown offers several distinct advantages. Its multi-path structure allows for the integration of both global and local information, mitigating the severe loss of detail often caused by traditional downsampling methods. Additionally, by reducing spatial resolution through pooling before applying lightweight convolutions, ADown achieves efficient feature extraction with significantly fewer parameters and lower FLOPs, without sacrificing representational power.

Moreover, ADown can be seamlessly integrated with existing multi-scale feature fusion modules, such as SPPF or FPN, enhancing the capacity of both the backbone and neck components to retain fine-grained features. This is particularly beneficial for small object detection tasks. In UAV imagery, where targets tend to be small and highly resolution-sensitive, the hierarchical detail preserved by ADown proves critical for accurately detecting small-scale objects. Its design not only improves fine-feature retention but also enhances the overall robustness of the model in multi-scale environments.

2.1.4. Proposed ADG-YOLO

To enhance the detection capability of lightweight networks for low-altitude, low-speed, and small-sized UAVs—commonly referred to as “low-slow-small” targets—under resource-constrained environments, this study proposes a novel architecture named ADG-YOLO, based on the original YOLOv11n framework. While maintaining detection accuracy, ADG-YOLO significantly reduces model parameter size and computational complexity. The architecture incorporates systematic structural optimizations in three key areas: feature extraction, downsampling strategy, and multi-scale feature fusion. These improvements collectively strengthen the model’s perception capability for low-altitude UAV targets in ground-based scenarios, thereby better meeting the practical demands of UAV detection from aerial perspectives. The overall network architecture of ADG-YOLO is illustrated in

Figure 5.

Firstly, in both the backbone and neck of the network, the original C3k2 modules are systematically replaced with C3Ghost modules. C3Ghost is a lightweight residual module constructed using GhostConv, initially introduced in GhostNet, and incorporates a Cross Stage Partial (CSP) structure to enable cross-stage feature fusion. Its core design concept lies in generating primary features through standard convolution, while reusing redundant information by producing additional “ghost” features through low-cost linear operations such as depthwise separable convolutions. This approach significantly reduces the number of parameters and the overall computational cost (FLOPs), making it especially suitable for deployment on edge devices with limited computing resources. Additionally, the stacked structure of GhostBottleneck layers further enhances the network’s ability to represent features across multiple semantic levels.

Secondly, all stride=2 downsampling operations in the network are replaced with the ADown module. Instead of conventional 3×3 strided convolutions, ADown adopts a dual-path structure composed of average pooling and max pooling for spatial compression. Each path extracts features at different scales through lightweight 3×3 and 1×1 convolutions, and the outputs are concatenated along the channel dimension. This asymmetric parallel design allows ADown to preserve more rich texture and edge information while reducing feature map resolution. Such a design is particularly beneficial in UAV-based detection scenarios where objects are small and captured from high-altitude viewpoints against complex backgrounds. Compared to standard convolutions, ADown effectively reduces computational burden without compromising detection accuracy, while improving the flexibility and robustness of the downsampling process.

Thirdly, the Spatial Pyramid Pooling - Fast (SPPF) module is retained at the end of the backbone to enhance the modeling of long-range contextual information. Meanwhile, in the neck, a series of alternating operations—upsampling, feature concatenation, and downsampling via ADown—are introduced for feature fusion. This design facilitates the precise supplementation of low-level detail with high-level semantic information and improves alignment and interaction across multi-scale feature maps. As a result, the model’s ability to detect small objects and capture boundary-level details is significantly enhanced. Combined with the lightweight feature extraction capability of the C3Ghost modules at various stages, the entire network achieves high detection accuracy while substantially reducing deployment cost and system latency.

In summary, the improvements of ADG-YOLO presented in this study are threefold: the C3Ghost modules enable efficient lightweight feature representation; the ADown module reconstructs a more effective downsampling pathway; and the SPPF module, together with multi-scale path interactions, strengthens fine-grained feature aggregation, particularly for small object detection. The complete network architecture of ADG-YOLO is shown in

Figure 5, where the overall design seamlessly integrates lightweight structure with multi-scale feature enhancement. This model achieves a well-balanced trade-off among accuracy, inference speed, and computational resource consumption, offering high adaptability and practical value for real-world deployment.

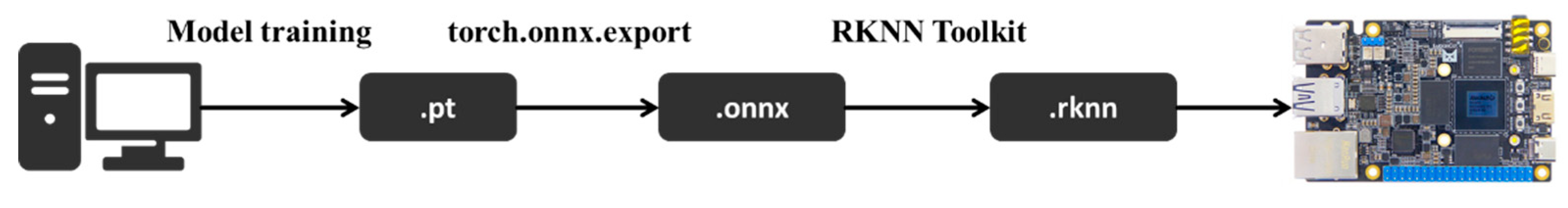

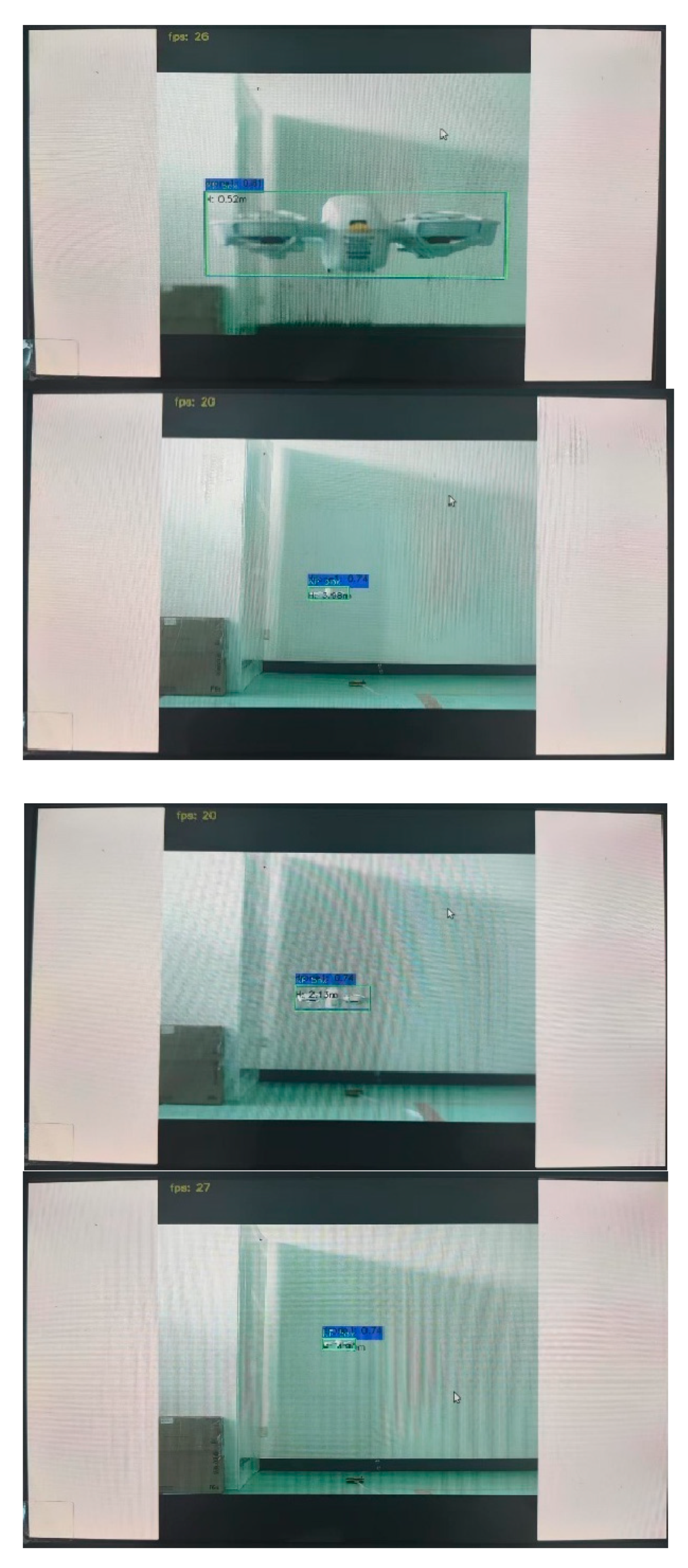

2.2. Model Conversion and Edge Deployment

Considering factors such as device size, weight, scalability, and cost, this study selects the LubanCat 4 development board as the deployment platform for the ADG-YOLO model. The board is equipped with the Rockchip RK3588S processor and integrates an AI acceleration NPU capable of INT4, INT8, and INT16 mixed-precision computing, with a peak performance of up to 6 TOPS. It includes 4 GB of onboard memory and supports peripheral interfaces such as mini HDMI output and USB camera input, with an overall weight of approximately 62 grams.

Given the limited computing capacity of the CPU, it is necessary to maximize inference efficiency by converting the model from its original .pt format (trained with PyTorch) to the .rknn format compatible with the NPU. The conversion pipeline proceeds as follows: first, the trained model is exported to the ONNX format using the torch.onnx.export interface in PyTorch; then, the RKNN Toolkit is used to convert the ONNX model into RKNN format. The overall conversion process is illustrated in

Figure 6.

After conversion, the model is deployed onto the development board to enable real-time detection of UAV targets from live video input via the connected USB camera. With the aid of hardware acceleration provided by the NPU, the system is capable of maintaining a high frame rate and fast response speed while ensuring detection accuracy, thereby fulfilling the dual demands of real-time performance and lightweight deployment in practical application scenarios.

2.3. Target Monitoring Based on YOLOv11 Detection and EKF Tracking

In this study, we propose a method that integrates the YOLO object detection algorithm with the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) for target monitoring in dynamic scenarios. The YOLO model is employed to extract bounding box information from consecutive image frames in real time, including the center position and size parameters of the detected targets. To enable temporal filtering and motion trajectory prediction of the detected objects, the target state is modeled as a six-dimensional vector

,consisting of the center coordinates (

cx,cy),the horizontal and vertical velocity components (

vx,vy),and the width

w and height

h of the bounding box. Considering that targets typically follow a constant velocity linear motion within short time intervals and that their size changes are relatively stable, a state transition model is formulated under this assumption. The corresponding state transition matrix is defined as follows:

The observations provided by YOLO are the bounding box parameters of the detected target in

the image, represented as

. The correspondence between these observations and the system

state vector is modeled through an observation matrix, which is expressed as follows:

The execution process of the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) consists of two stages: prediction and update. In the prediction stage, the target state and its covariance are estimated based on the current state and the state transition model, as expressed by:

Here, Q denotes the process noise covariance matrix, and P represents the observation noise covariance matrix.Upon receiving a new observation zzz from the YOLO algorithm, the update stage is performed as follows:

Here, I denotes the identity matrix.

The integration of the EKF module helps to mitigate the potential localization fluctuations and occasional false detections that may occur in YOLO's single-frame inference. This facilitates smoother target position estimation and further enhances the tracking consistency and robustness of the system in multi-frame processing scenarios.

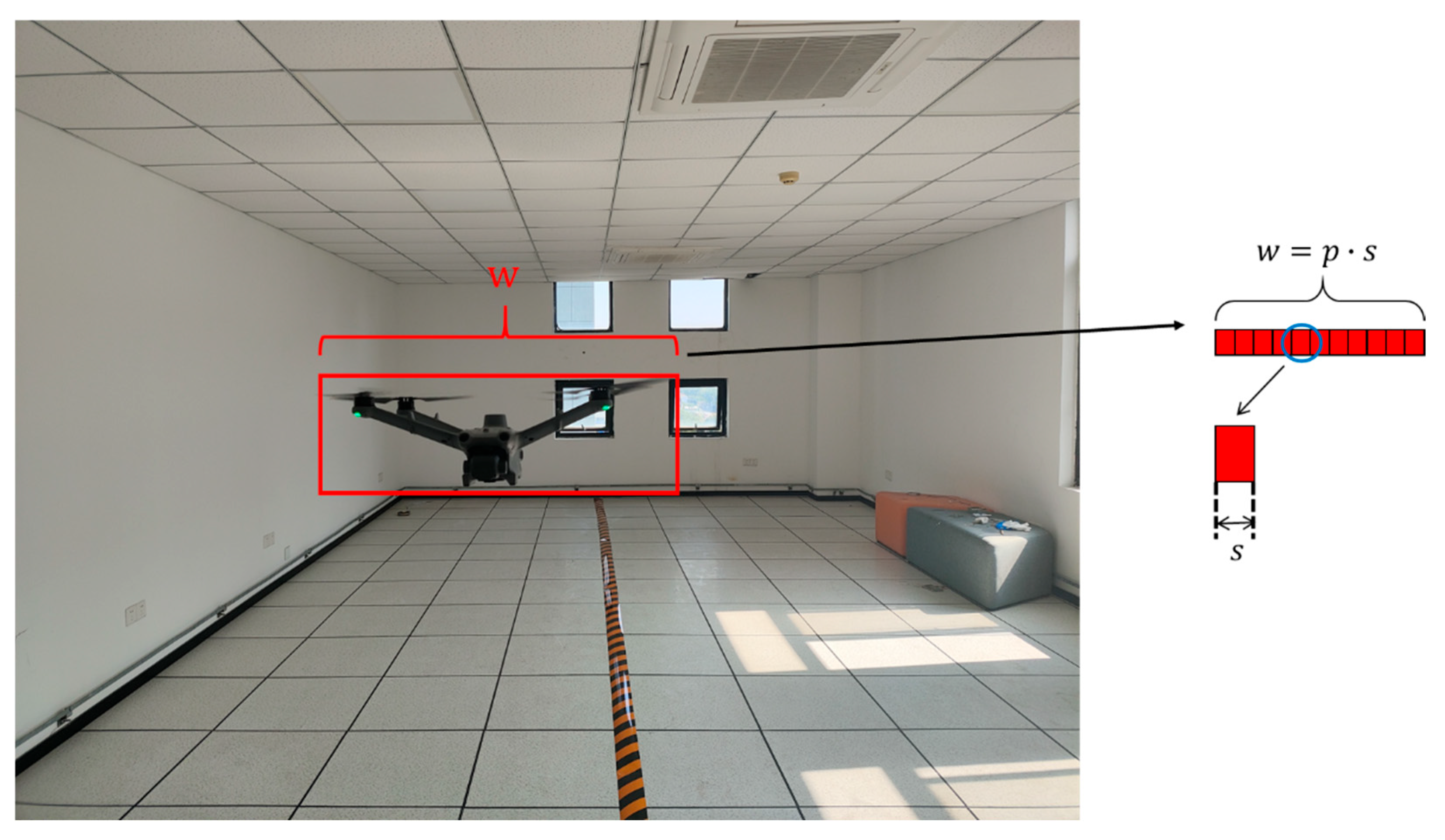

2.4. Monocular Ranging for UAVs Using Similar Triangles

Figure 7 illustrates the UAV target detection results based on the YOLO model, where the red bounding boxes accurately locate and outline the position and size of the targets in the monocular images. The pixel width of the bounding box is denoted as

p, representing the projected size of the target in the image, which serves as a key parameter for subsequent distance estimation. Neglecting lens distortion, and based on the principle of similar triangles, when the actual width of the target is

W, the camera focal length is

f, and the physical size of a single pixel on the image sensor is

s, the actual projected width

w of the target on the imaging plane can be expressed as:

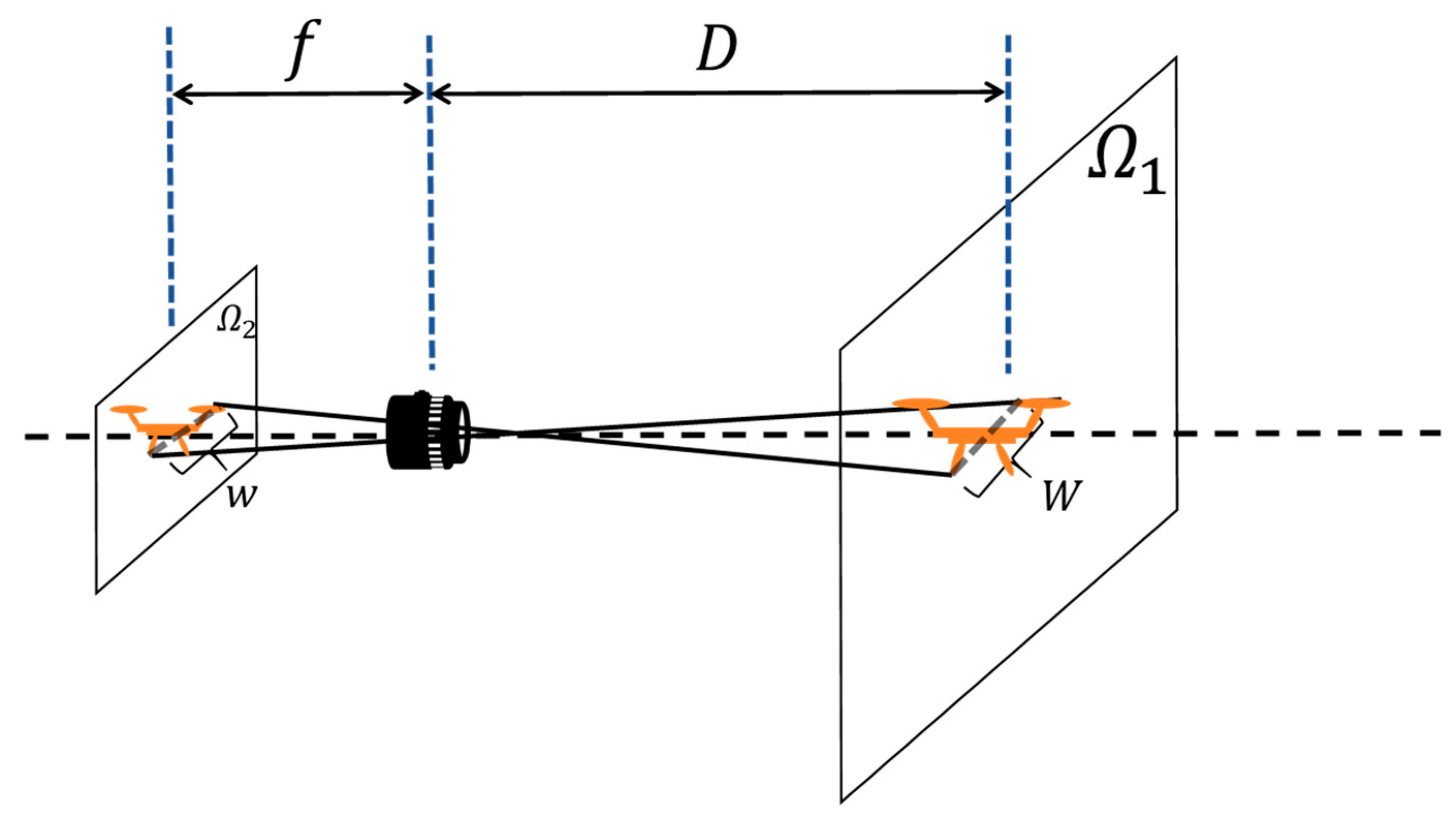

As shown in

Figure 8, when the target plane

is perpendicular to the optical axis of the camera, the imaging process can be abstracted as two similar triangles, which satisfy the following proportional relationship:

Here,

D denotes the distance from the target to the camera along the optical axis. Based on this relationship, the formula for computing the target distance is derived as follows:

In this study, the training dataset comprises three different types of UAVs, each associated with a known physical width Wn. The YOLO model not only outputs the bounding box coordinates but also possesses target classification capability, enabling precise identification of the specific UAV type. Once the target type is detected, the corresponding Wn is automatically selected and substituted into the distance estimation formula (10), thereby enhancing the accuracy and generalizability of the distance measurement.

3. Experiment

3.1. Dataset

A comprehensive UAV detection dataset was constructed for this study, comprising a total of 5,343 high-resolution images. This dataset integrates two subsets: a custom-target subset with 2,670 images and a generalization subset with 2,664 images. The custom subset focuses on three specific UAV models: DJI 3TD, with 943 training and 254 testing images (labeled as drone1); DJI NEO, with 739 training and 170 testing images (drone2); and DWI-S811, with 454 training and 110 testing images (drone3). All images in this subset were captured under strictly controlled conditions, with target distances ranging from 5 to 30 meters and 360-degree coverage, to reflect variations in object appearance under different perspectives and distances.

The generalization subset was collected from publicly available multirotor UAV image resources published on the CSDN object detection platform. It contains quadrotor and hexarotor UAVs from popular brands such as DJI and Autel, appearing in diverse environments including urban buildings, rural landscapes, highways, and industrial areas. Additionally, the images cover challenging weather conditions such as bright sunlight, fog, and rainfall. All images were annotated using professional tools in compliance with the YOLOv11 format, including normalized center coordinates (x,y) and relative width w and height h of each bounding box.

Figure 9 shows representative images of the three specific UAV models from the custom subset, highlighting multi-angle and multi-distance variations.

Figure 10 presents sample images from the generalization subset, illustrating environmental and visual diversity.

Table 1 provides an overview of the dataset composition, including the number of training and testing images for each subset and the corresponding label formats.

A differentiated sampling strategy was used to partition the dataset. The custom subset contains 2,136 training images and 534 testing images, while the generalization subset includes 2,363 training and 301 testing images. To enhance detection performance on specific UAV types, the test set was intentionally supplemented with additional samples of DJI 3TD, DJI NEO, and DWI-S811. This allows the model to better learn and evaluate fine-grained appearance features of these UAVs, contributing to improved detection accuracy and robustness.

3.2. Experimental Environment and Experimental Parametes

To evaluate the performance of the proposed ADG-YOLO model in UAV object detection tasks, the model was trained on the custom dataset described in

Section 3.1. Comparative experiments were conducted against several representative algorithms under identical training configurations. To ensure the reproducibility and fairness of the results, the experimental environment settings and training parameters are summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

In target detection tasks, the Mean Average Precision (

mAP) is widely employed to evaluate the detection performance of a model. Based on the model’s prediction results, two key metrics can be further computed: Precision (

P) and Recall (

R). Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted targets among all samples identified as targets by the model, whereas Recall reflects the model’s ability to detect actual targets, defined as the ratio of correctly detected targets to all true targets. Typically, there exists a trade-off between Precision and Recall, where improving one may lead to the reduction of the other. Therefore, a Precision–Recall (

PR) curve is plotted to comprehensively analyze the detection performance of the model. For a single category, the Average Precision (

AP) is defined as the area under the

PR curve, which is calculated as follows:

In practical computations, a discrete approximation method is typically employed:

Here,

Ri represents the sampled recall values, and

P(

Ri) denotes the corresponding precision at each recall point. The calculation of

AP varies slightly across different datasets. For instance, the PASCAL VOC dataset adopts an interpolation method based on 11 fixed recall points, whereas the COCO evaluation protocol computes the mean over all recall points. For multi-class object detection, the Mean Average Precision (

mAP) is defined as the mean

AP across all categories:

Here, N denotes the total number of categories, and APi represents the Average Precision of the i-th target category.

In practical object detection scenarios, in addition to model accuracy, the actual runtime speed of the model is also of significant concern. Frames Per Second (

FPS) is a key metric for evaluating the runtime efficiency of a model, representing the number of image frames the model can process per second. The

FPS can be calculated as follows:

Here, Ns denotes the total number of processed frames, and T represents the total processing time in seconds. A higher FPS indicates that the model can process input images more rapidly, thereby enhancing its capability for real-time detection.

3.4. Model Performance Analysis

To evaluate the overall performance of the ADG-YOLO model in UAV target detection, three mainstream lightweight models—YOLOv5s, YOLOv8n, and YOLOv11n—are selected as baseline comparisons. The comparison dimensions include model parameters, computational complexity (GFLOPs), precision, recall, and FPS. All FPS values are obtained through real-world measurements on the Lubancat4 edge computing development board. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 4.

ADG-YOLO contains only 1.77M parameters and requires 5.7 GFLOPs, representing a substantial simplification compared to YOLOv5s, which has 7.02M parameters and 15.8 GFLOPs. It is also more lightweight than YOLOv8n (3.00M parameters, 8.1 GFLOPs) and YOLOv11n (2.58M parameters, 6.3 GFLOPs), making it well-suited for deployment on resource-constrained edge platforms. In terms of detection accuracy, ADG-YOLO achieves 98.4% mAP0.5 and 85.2% mAP0.5:0.95, slightly outperforming the other models. Notably, its mAP0.5:0.95 is significantly higher than that of YOLOv5s and YOLOv8n (both 84.2%), and comparable to YOLOv11n (85.3%), demonstrating strong robustness. For inference speed, ADG-YOLO reaches 27 FPS, which significantly exceeds YOLOv5s (15 FPS), YOLOv8n (12 FPS), and YOLOv11n (10 FPS), thereby achieving an effective balance between model compactness and real-time performance.

As illustrated in

Figure 11, the proposed ADG-YOLO model demonstrates robust detection capability for UAV targets under complex backgrounds, various viewing angles, and different lighting conditions.

In summary, ADG-YOLO achieves an optimal trade-off among accuracy, inference speed, and resource consumption, making it particularly suitable for real-time UAV detection tasks in computationally constrained environments. The model also exhibits strong engineering adaptability for practical deployment.

5. Discussion

The proposed ADG-YOLO framework demonstrates significant advancements in real-time UAV detection and distance estimation on edge devices. Nonetheless, several challenges remain that warrant further investigation to enhance its scalability and real-world applicability. First, although the current custom dataset (5,343 images) includes three UAV models across diverse backgrounds, its limited scope hinders generalization. Future work should focus on building a large-scale, open-source UAV dataset covering various drone types (e.g., quadrotors, hexarotors, fixed-wing), sizes (micro to commercial), and environmental conditions (e.g., night, adverse weather, swarm operations), particularly under low-SNR settings prone to false positives. Collaborative data collection across platforms may expedite this process.

Second, current distance estimation depends on known UAV dimensions (e.g., DJI 3TD: 62 cm, DJI NEO: 15 cm), which limits its flexibility in handling unknown models. Future research should explore multi-model support through an onboard UAV identification module containing pre-calibrated physical parameters. Additionally, geometry-independent approaches, such as monocular depth estimation fused with detection outputs, offer promising alternatives that remove dependency on prior shape knowledge. Adaptive focal length calibration should also be considered to reduce measurement errors in long-range scenarios, particularly beyond 50 meters.

Third, while ADG-YOLO achieves 27 FPS on the Lubancat4 edge device, its practical deployment on UAVs introduces additional challenges. These include optimizing the model for ultra-low-power processors, ensuring efficient thermal dissipation during extended operation, and compensating for dynamic motion via IMU and EKF integration to stabilize detection during rapid pitch or yaw movements. Moreover, expanding the system to air-to-air detection, such as in drone swarm environments, requires altitude-invariant ranging models and training strategies that are robust to occlusion. Finally, achieving sub-20 ms end-to-end latency is essential for enabling closed-loop tasks such as autonomous interception and cooperative formation flight.