Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. What Is Life? Is It Expected?

3. Universal Constraints

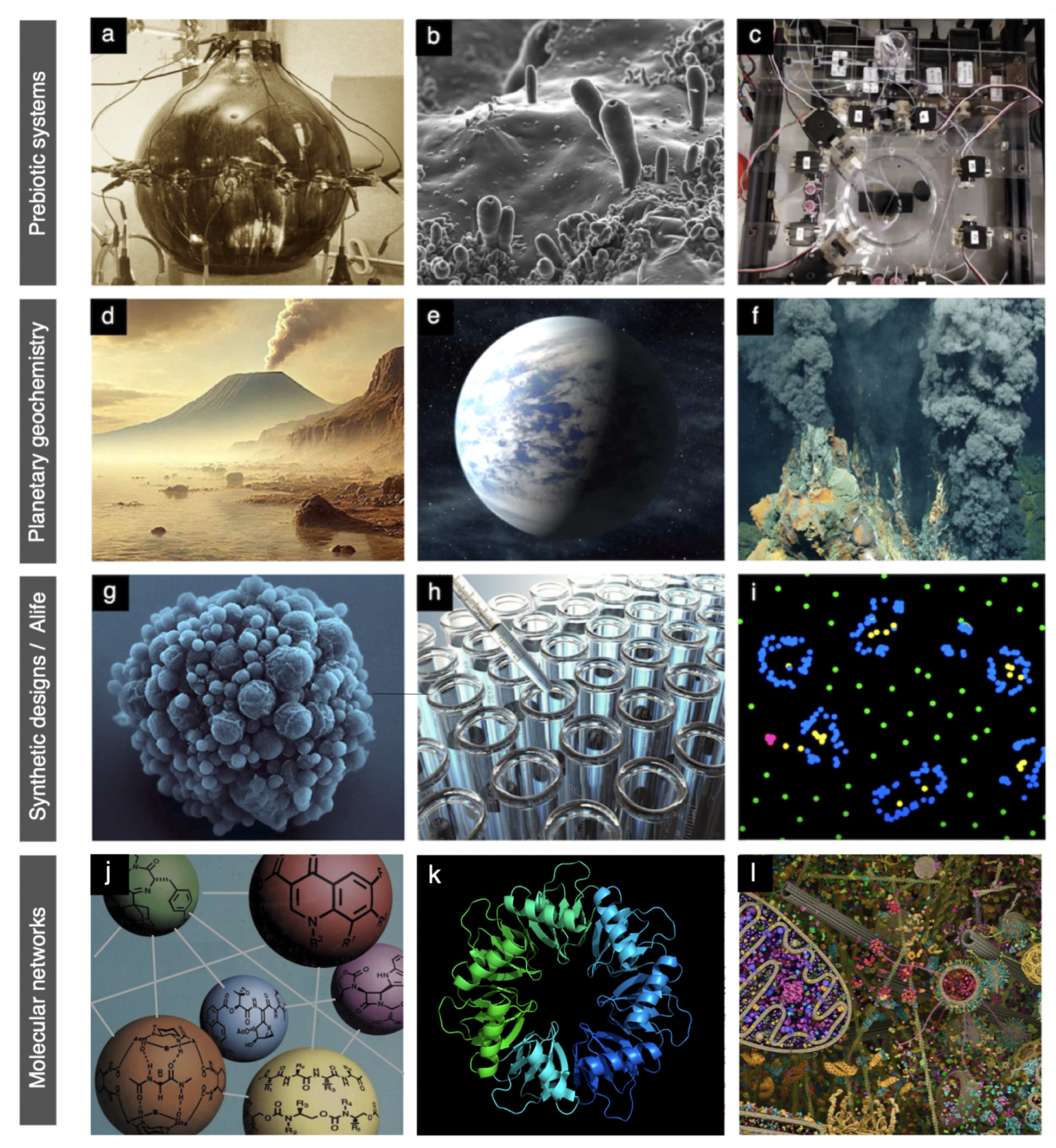

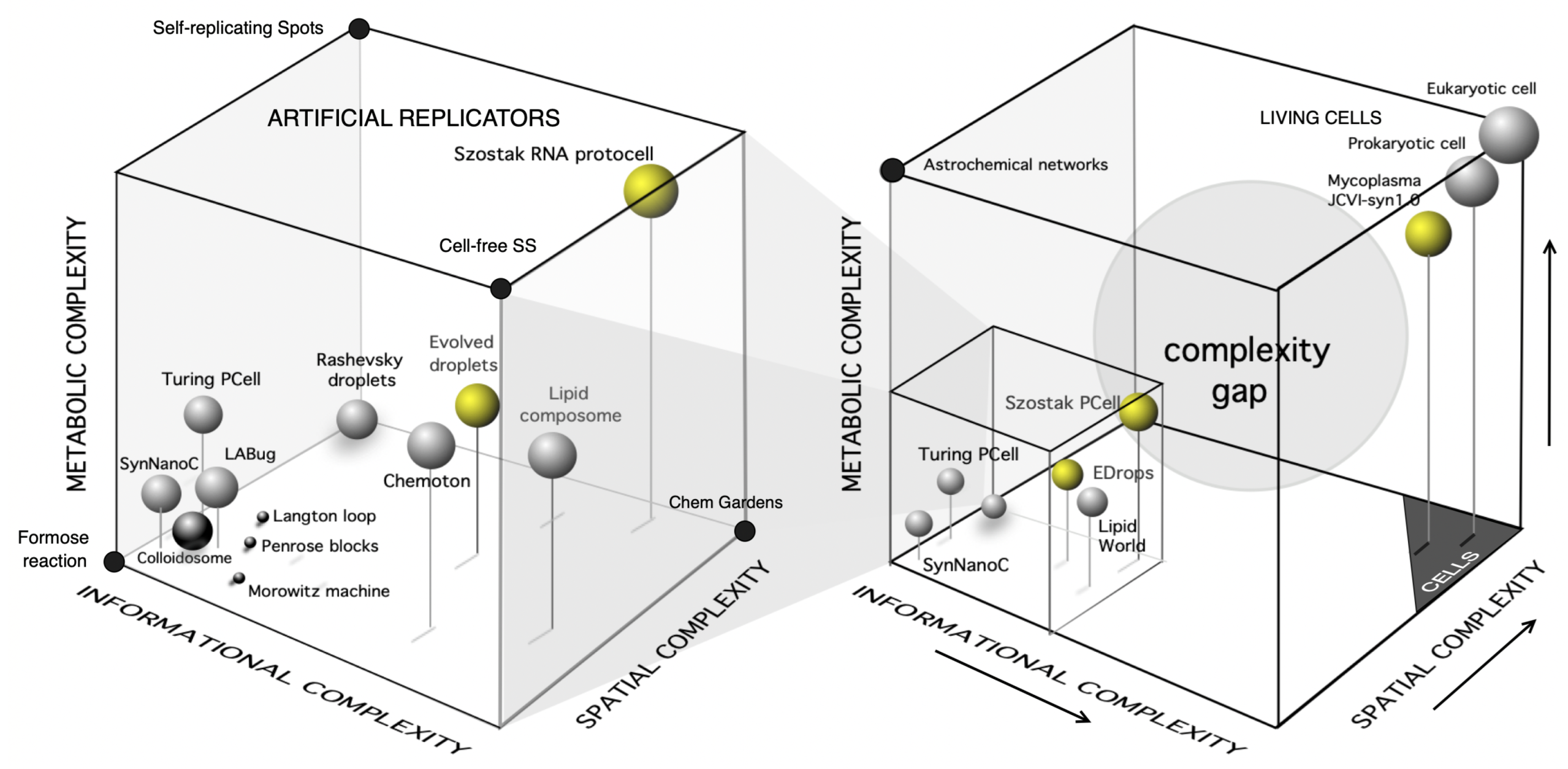

4. Pathways Towards Life

5. Beyond Terrestrial Life: Exobiology, Xenobiology, and Virtual Life

6. Discussion

Acknowledgments

References

- Benner, S.A. Defining life. Astrobiology 2010, 10, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woese, C.R. A new biology for a new century. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews 2004, 68, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempes, C.P.; Krakauer, D.C. The multiple paths to multiple life. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2021, 89, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grefenstette, N.; Chou, L.; Colón-Santos, S.; Fisher, T.M.; Mierzejewski, V.; Nural, C.; Sinhadc, P.; Vidaurri, M.; Vincent, L.; Weng, M.M. Life as We Don’t Know It. Astrobiology 2024, 24, S–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.I.; Davies, P.C. The algorithmic origins of life. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2013, 10, 20120869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, R.; Kempes, C.P.; Corominas-Murtra, B.; De Domenico, M.; Kolchinsky, A.; Lachmann, M.; Libby, E.; Saavedra, S.; Smith, E.; Wolpert, D. Fundamental constraints to the logic of living systems. Interface Focus 2024, 14, 20240010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, C.G. Artificial life: An overview; MIT press, 1997.

- Szostak, J.W. Attempts to define life do not help to understand the origin of life. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2012, 29, 599–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oparin, A. Proiskhozhdenie zhizni; Moskovskii Rabochii, 1924. (First presentation of Oparin’s heterotrophic origin-of-life hypothesis).

- Oparin, A. The Origin of Life; Macmillan, 1938. (English edition of Vozniknovenie zhizni na zemle, first Russian ed. 1936).

- Miller, S.L. A production of amino acids under possible primitive earth conditions. Science 1953, 117, 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bada, J.L.; Lazcano, A. Prebiotic soup–revisiting the miller experiment. Science 2003, 300, 745–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oró, J. Synthesis of adenine from ammonium cyanide. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 1960, 2, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oró, J. Mechanism of synthesis of adenine from hydrogen cyanide under possible primitive Earth conditions. Nature 1961, 191, 1193–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopf, J.W. Pioneers of Origin of Life Studies—Darwin, Oparin, Haldane, Miller, Oró—And the Oldest Known Records of Life. Life 2024, 14, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oró, J. Comets and the formation of biochemical compounds on the primitive Earth. Nature 1961, 190, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro, J.; Mills, T.; Lazcano, A. Comets and the formation of biochemical compounds on the primitive Earth–A review. Origins of Life and Evolution of the Biosphere 1991, 21, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagan, C. The search for extraterrestrial life. Scientific American 1994, 271, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyba, C.F.; Thomas, P.J.; Brookshaw, L.; Sagan, C. Cometary delivery of organic molecules to the early Earth. Science 1990, 249, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.I. Origins of life: a problem for physics, a key issues review. Reports on Progress in Physics 2017, 80, 092601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenfeld, N.; Woese, C. Life is physics: evolution as a collective phenomenon far from equilibrium. Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics 2011, 2, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seager, S. Exoplanet habitability. Science 2013, 340, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N.; Hogeweg, P.; Kaneko, K. Conceptualizing the origin of life in terms of evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2017, 375, 20160346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingam, M.; Loeb, A. Physical constraints on the likelihood of life on exoplanets. International Journal of Astrobiology 2018, 17, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwieterman, E.W.; Kiang, N.Y.; Parenteau, M.N.; Harman, C.E.; DasSarma, S.; Fisher, T.M.; Arney, G.N.; Hartnett, H.E.; Reinhard, C.T.; Olson, S.L.; et al. Exoplanet biosignatures: a review of remotely detectable signs of life. Astrobiology 2018, 18, 663–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.I.; Bains, W.; Cronin, L.; DasSarma, S.; Danielache, S.; Domagal-Goldman, S.; Kacar, B.; Kiang, N.Y.; Lenardic, A.; Reinhard, C.T.; et al. Exoplanet biosignatures: future directions. Astrobiology 2018, 18, 779–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, R.V.; Munteanu, A. The large-scale organization of chemical reaction networks in astrophysics. Europhysics Letters 2004, 68, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sanchez, M.; Jimenez-Serra, I.; Puente-Sanchez, F.; Aguirre, J. The emergence of interstellar molecular complexity explained by interacting networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2119734119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Ruz, M.; Jiménez-Serra, I.; Aguirre, J. A theoretical approach to the complex chemical evolution of phosphorus in the interstellar medium. The Astrophysical Journal 2023, 956, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, T.; Janin, E.; Walker, S. A Complex Systems Approach to Exoplanet Atmospheric Chemistry: New Prospects for Ruling Out the Possibility of Alien Life-As-We-Know-It. arXiv 2023. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2310.05359[astro-ph.EP], 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.F.; Morowitz, H.J. Between history and physics. Journal of Molecular Evolution 1982, 18, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyba, C.F.; Hand, K.P. Astrobiology: the study of the living universe. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2005, 43, 31–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.M.P.; Hinkley, T.; Taylor, J.W.; Yanev, K.; Cronin, L. Evolution of oil droplets in a chemorobotic platform. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Points, L.J.; Taylor, J.W.; Grizou, J.; Donkers, K.; Cronin, L. Artificial intelligence exploration of unstable protocells leads to predictable properties and discovery of collective behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzhaf, W.; Yamamoto, L. Artificial chemistries; MIT Press, 2015.

- Jaeger, J. Assembly theory: What it does and what it does not do. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2024, 92, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahão, F.S.; Hernández-Orozco, S.; Kiani, N.A.; Tegnér, J.; Zenil, H. Assembly theory is an approximation to algorithmic complexity based on LZ compression that does not explain selection or evolution. PLOS Complex Systems 2024, 1, e0000014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempes, C.P.; Lachmann, M.; Iannaccone, A.; Fricke, G.M.; Chowdhury, M.R.; Walker, S.I.; Cronin, L. Assembly theory and its relationship with computational complexity. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2406.12176. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, M. Complexity myths and the misappropriation of evolutionary theory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2025, 122, e2425772122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.M.; Mathis, C.; Carrick, E.; Keenan, G.; Cooper, G.J.; Graham, H.; Craven, M.; Gromski, P.S.; Moore, D.G.; Walker, S.I.; et al. Identifying molecules as biosignatures with assembly theory and mass spectrometry. Nature communications 2021, 12, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Czégel, D.; Lachmann, M.; Kempes, C.P.; Walker, S.I.; Cronin, L. Assembly theory explains and quantifies selection and evolution. Nature 2023, 622, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazen, R.M.; Burns, P.C.; Cleaves, H.J.; Downs, R.T.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Wong, M.L. Molecular assembly indices of mineral heteropolyanions: some abiotic molecules are as complex as large biomolecules. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2024, 21, 20230632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.I.; Mathis, C.; Marshall, S.; Cronin, L. Experimentally measured assembly indices are required to determine the threshold for life. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2024, 21, 20240367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns-Smith, A.G. Genetic Takeover and the Mineral Origins of Life; Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Cleland, C.E. Epistemological issues in the study of microbial life: alternative terran biospheres? Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 2007, 38, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, P. The mathematics of Darwin’s theory of evolution: 1859 and 150 years later. In The Mathematics of Darwin’s Legacy; Springer, 2011; pp. 27–66.

- Cairns-Smith, A.G. The origin of life and the nature of the primitive gene. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1966, 10, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pross, A. Toward a general theory of evolution: Extending Darwinian theory to inanimate matter. Journal of Systems Chemistry 2011, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, S. Life as “self-motion”: Descartes and “the Aristotelians” on the soul as the life of the body. Review of Metaphysics 2006, 59, 723–755. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, W.B. Organization for physiological homeostasis. Physiological Reviews 1929, 9, 399–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoeisis and Cognition: the realization of the living; D. Reidel, 1980.

- Lachmann, M.; Walker, S. Life!=alive. Aeon 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, R.; Kofman, K.; y Arcas, B.A.; Levin, M. What Lives? A meta-analysis of diverse opinions on the definition of life. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.15849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Kubica, A. Science of the Gaps. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- de Duve, C. Life as a cosmic imperative? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2011, 369, 620–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, J. Chance and Necessity; Collins, 1971.

- Hazen, R.M. Chance, necessity and the origins of life: a physical sciences perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2017, 375, 20160353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deamer, D. First life: Discovering the connections between stars, cells, and how life began; Univ of California Press, 2011.

- Johansen, A.; Sornette, D. Finite-time singularity in the dynamics of the world population and economic indices. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2001, 294, 465–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanel, R.; Kauffman, S.A.; Thurner, S. Phase transitions in random catalytic networks. Physical Review E 2005, 72, 036117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Bettencourt, L.M.A.; Strumsky, D.; Lobo, J. Invention as a combinatorial process: evidence from U.S. patents. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2015, 12, 20150272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sole, R.; Amor, D.R.; Valverde, S. On singularities and black holes in combination-driven models of technological innovation networks. Plos one 2016, 11, e0146180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.A. Investigations; Oxford University Press: New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram, S. Nature 1984, 311, 419–424. [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, S. Physical Review Letters 1985, 54, 735–738. [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, S. A New Kind of Science; Wolfram Media: Champaign, IL, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ilachinski, A. Cellular Automata: A Discrete Universe; World Scientific: Singapore, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Israeli, N.; Goldenfeld, N. Computational irreducibility and the predictability of complex physical systems. Physical review letters 2004, 92, 074105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauffman, S.A.; Roli, A. Is the emergence of life and of agency expected? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2025; This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, R.; de Domenico’, M. Phase transitions in the origins of life. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue, 20160353. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, N.R. The universal nature of biochemistry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2001, 98, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bains, W. Many chemistries could be used to build living systems. Astrobiology 2004, 4, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susskind, L. The cosmic landscape: String theory and the illusion of intelligent design; Back Bay Books, 2008.

- Koonin, E.V. The Biological Big Bang model for the major transitions in evolution. Biology Direct 2007, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, H.E. Introduction to Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena; Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Goldenfeld, N. Lectures on Phase Transitions and the Renormalization Group; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, R. Phase transitions; Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Jeancolas, C.; Malaterre, C.; Nghe, P. Thresholds in origin of life scenarios. Iscience 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempes, C.P.; Koehl, M.; West, G.B. The scales that limit: the physical boundaries of evolution. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2019, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. What is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Morowitz, H.J. Energy Flow in Biology: Biological Organization as a Problem in Thermal Physics; Academic Press: New York, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Morowitz, H.; Smith, E. Energy flow and the organization of life. Complexity 2007, 13, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. Thermodynamics of natural selection I: Energy flow and the limits on organization. Journal of theoretical biology 2008, 252, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. Thermodynamics of natural selection II: Chemical Carnot cycles. Journal of theoretical biology 2008, 252, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolchinsky, A. Thermodynamics of Darwinian selection in molecular replicators. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Eigen, M.; Gardiner, W.; Schuster, P.; Winkler-Oswatitsch, R. The origin of genetic information. Scientific American 1981, 244, 88–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ash, R.B. Information theory; Courier Corporation, 2012.

- Küppers, B.O. Information and the Origin of Life; Mit Press, 1990.

- Adami, C. Information theory in molecular biology. Physics of Life Reviews 2004, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.I.; Davies, P.C.; Ellis, G.F. The informational architecture of the cell: a systems view. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2017, 375, 20160392. [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth, K.D.; Ellis, G.F.; Jaeger, J. Living through downward causation: from molecules to ecosystems. Interface Focus 2013, 3, 20130062. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, F.H. On protein synthesis. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology 1958, 12, 138–163. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, F. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature 1970, 227, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieffry, D.; Sarkar, S. Forty years under the central dogma. Trends in biochemical sciences 1998, 23, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ille, A.M.; Lamont, H.; Mathews, M.B. The Central Dogma revisited: Insights from protein synthesis, CRISPR, and beyond. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA 2022, 13, e1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N.; Kaneko, K. The origin of the central dogma through conflicting multilevel selection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2019, 286, 20191359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N.; Hogeweg, P.; Kaneko, K. The origin of a primordial genome through spontaneous symmetry breaking. Nature communications 2017, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N.; Kunihiko, K. Generalising the Central Dogma as a cross-hierarchical principle of biology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Plum, A.M.; Kempes, C.P.; Peng, Z.; Baum, D.A. Spatial structure supports diversity in prebiotic autocatalytic chemical ecosystems. npj Complexity 2025, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.; Morowitz, H.J. The Origin and Nature of Life on Earth: The Emergence of the Fourth Geosphere; Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Lane, N.; Martin, W.F. The origin of membrane bioenergetics. Cell 2012, 151, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, N.; Hogeweg, P. Multilevel selection in models of prebiotic evolution II: a direct comparison of compartmentalization and spatial self-organization. PLoS computational biology 2009, 5, e1000542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.; Pohorille, A.; Chen, I.A. Molecular crowding and early evolution. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres 2014, 44, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wächtershäuser, G. Before enzymes and templates: theory of surface metabolism. Microbiological reviews 1988, 52, 452–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, P. Kempes, D.A.; Mathis, C. How hard is it to encapsulate life? The general constraints on encapsulation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

- Rivas, G.; Ferrone, F.; Herzfeld, J. Life in a crowded world: Workshop on the biological implications of macromolecular crowding. EMBO reports 2004, 5, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.X.; Rivas, G.; Minton, A.P. Macromolecular crowding and confinement: biochemical, biophysical, and potential physiological consequences. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 37, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempes, C.P.; Wang, L.; Amend, J.P.; Doyle, J.; Hoehler, T. Evolutionary tradeoffs in cellular composition across diverse bacteria. The ISME journal 2016, 10, 2145–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Kempes, C.P. Metabolic scaling in small life forms. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2403.00001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempes, C.P.; Dutkiewicz, S.; Follows, M.J. Growth, metabolic partitioning, and the size of microorganisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempes, C.P.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Wolpert, D.; Libby, E.; Amend, J.; Hoehler, T. Drivers of bacterial maintenance and minimal energy requirements. Frontiers in microbiology 2017, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglada-Escudé, G.; Amado, P.J.; Barnes, J.; Berdiñas, Z.M.; Butler, R.P.; Coleman, G.A.; de La Cueva, I.; Dreizler, S.; Endl, M.; Giesers, B.; et al. A terrestrial planet candidate in a temperate orbit around Proxima Centauri. nature 2016, 536, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Jin, M.; Lingam, M.; Airapetian, V.S.; Ma, Y.; van der Holst, B. Atmospheric escape from the TRAPPIST-1 planets and implications for habitability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusudhan, N. Exoplanetary atmospheres: key insights, challenges, and prospects. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2019, 57, 617–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.L.; Bott, K.; Dalba, P.A.; Fetherolf, T.; Kane, S.R.; Kopparapu, R.; Li, Z.; Ostberg, C. A catalog of habitable zone exoplanets. The Astronomical Journal 2023, 165, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, P. Life’s matrix: a biography of water; Univ of California Press, 2001.

- Westall, F.; Brack, A. The importance of water for life. Space Science Reviews 2018, 214, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento Vieira, A.; Kleinermanns, K.; Martin, W.F.; Preiner, M. The ambivalent role of water at the origins of life. FEBS letters 2020, 594, 2717–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J. The chemical elements of life. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans 1991, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.F.; Williams, R.J.P. The biological chemistry of the elements: the inorganic chemistry of life; Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Damer, B.; Deamer, D. The hot spring hypothesis for an origin of life. Astrobiology 2020, 20, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, C.M.; Ellison, G.B.; Tuck, A.F.; Vaida, V. Atmospheric aerosols as prebiotic chemical reactors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97, 11864–11868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldford, J.E.; Hartman, H.; Smith, T.F.; Segrè, D. Remnants of an ancient metabolism without phosphate. Cell 2017, 168, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.B.; Drew, A.; Malloy, J.F.; Walker, S.I. Seeding biochemistry on other worlds: Enceladus as a case study. Astrobiology 2021, 21, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.S.; Bernier, C.R.; Hsiao, C.; Norris, A.M.; Kovacs, N.A.; Waterbury, C.C.; Stepanov, V.G.; Harvey, S.C.; Fox, G.E.; Wartell, R.M.; et al. Evolution of the ribosome at atomic resolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 10251–10256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, A.S.; Gulen, B.; Norris, A.M.; Kovacs, N.A.; Bernier, C.R.; Lanier, K.A.; Fox, G.E.; Harvey, S.C.; Wartell, R.M.; Hud, N.V.; et al. History of the ribosome and the origin of translation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 15396–15401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.D.; Kacar, B. Cofactors are remnants of life’s origin and early evolution. Journal of molecular evolution 2021, 89, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.K.; Kaçar, B. How to resurrect ancestral proteins as proxies for ancient biogeochemistry. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2019, 140, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçar, B. Reconstructing early microbial life. Annual Review of Microbiology 2024, 78, 463–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stüeken, E.E.; Anderson, R.; Bowman, J.; Brazelton, W.; Colangelo-Lillis, J.; Goldman, A.; Som, S.; Baross, J. Did life originate from a global chemical reactor? Geobiology 2013, 11, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitadai, N.; Maruyama, S. Origins of building blocks of life: A review. Geoscience Frontiers 2018, 9, 1117–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, T.; Baidya, A.S.; Cousins, C.R.; Stüeken, E.E. Planetary sources of bio-essential nutrients on a prebiotic world. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Mulkidjanian, A.Y.; Bychkov, A.Y.; Dibrova, D.V.; Galperin, M.Y.; Koonin, E.V. Origin of first cells at terrestrial, anoxic geothermal fields. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, E821–E830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiner, M.; Xavier, J.C.; Sousa, F.L.; Zimorski, V.; Neubeck, A.; Lang, S.Q.; Greenwell, H.C.; Kleinermanns, K.; Tüysüz, H.; McCollom, T.M.; et al. Serpentinization: connecting geochemistry, ancient metabolism and industrial hydrogenation. Life 2018, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, J.C.; Kauffman, S. Small-molecule autocatalytic networks are universal metabolic fossils. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2022, 380, 20210244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.A.; Rammu, H.; Liu, F.; Halpern, A.; Nunes Palmeira, R.; Lane, N. Life as a guide to its own origins. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2023, 54, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrnjavac, N.; Schwander, L.; Brabender, M.; Martin, W.F. Chemical antiquity in metabolism. Accounts of Chemical Research 2024, 57, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.C.; Preiner, M.; Xavier, J.C.; Zimorski, V.; Martin, W.F. The last universal common ancestor between ancient Earth chemistry and the onset of genetics. PLoS genetics 2018, 14, e1007518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrón-Mendoza, A.; Hernández-Morales, R.; Lazcano, A. Can the origin of biosynthetic routes be explained by a Frankenstein’s monster-like spontaneous assembly of prebiotic reactants? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, P.; Peretó, J. Before LUCA: Unearthing the chemical roots of metabolism. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Wächtershäuser, G. Life as we don’t know it. Science 2000, 289, 1307–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, C.E. The Quest for a Universal Theory of Life: Searching for Life as We Don’t Know It; Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Walker, S.I. Life as No One Knows it: The Physics of Life’s Emergence; Penguin, 2024.

- Schopf, J.W. Cradle of Life: The Discovery of Earth’s Earliest Fossils; Princeton University Press, 1999.

- Marais, D.D.; Walter, M. Astrobiology: exploring the origins, evolution, and distribution of life in the universe. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1999, 30, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.H.; Hyde, A.S.; Simkus, D.N.; Libby, E.; Maurer, S.E.; Graham, H.V.; Kempes, C.P.; Sherwood Lollar, B.; Chou, L.; Ellington, A.D.; et al. The grayness of the origin of life. Life 2021, 11, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asche, S.; Bautista, C.; Boulesteix, D.; Champagne-Ruel, A.; Mathis, C.; Markovitch, O.; Peng, Z.; Adams, A.; Dass, A.V.; Buch, A.; et al. What it takes to solve the Origin (s) of Life: An integrated review of techniques. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, R.V.; Macia, J. Expanding the landscape of biological computation with synthetic multicellular consortia. Natural Computing 2013, 12, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.; Abdo1, F.; Borkowski, O.; Kushwaha, M. Reconstituting alternative life using the test-bed of cell-free systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

- Noireaux, V.; Liu, A.P. The new age of cell-free biology. Annual review of biomedical engineering 2020, 22, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gánti, T. Chemoton Theory vol 2: theory of living systems; Kluwer, 2003.

- Solé, R.V.; Munteanu, A.; Rodriguez-Caso, C.; Macía, J. Synthetic protocell biology: from reproduction to computation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2007, 362, 1727–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, R.; Maull, V.; Amor, D.R.; Mauri, J.P.; Núria, C.P. Synthetic ecosystems: From the test tube to the biosphere. ACS Synthetic Biology 2024, 13, 3812–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maull, V.; Pla Mauri, J.; Conde Pueyo, N.; Solé, R. A synthetic microbial Daisyworld: planetary regulation in the test tube. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2024, 21, 20230585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Pal, R.; Rajamani, S. Dynamical interactions among protocell populations: Implications for membrane-mediated chemical evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Shirt-Ediss, B.; Ferrero-Fernández, A.; Martino, D.D.; Bich, L.; Moreno, A.; Ruiz-Mirazo, K. Modelling the prebiotic origins of regulation and agency in evolving protocell ecologies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, K.R.; Kolchinsky, A.; Rasmussen, S. Protocellular energy transduction, information, and fitness. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Stepney, S. Towards Origins of Virtual Artificial Life: an overview. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2025, This issue. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, S.; Wong, M.L. Defining Lyfe in the Universe: From Three Privileged Functions to Four Pillars. Life 2020, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, S.R.; Hill, M.L.; Kasting, J.F.; Kopparapu, R.K.; Quintana, E.V.; Barclay, T.; Batalha, N.M.; Borucki, W.J.; Ciardi, D.R.; Haghighipour, N.; et al. A catalog of Kepler habitable zone exoplanet candidates. The Astrophysical Journal 2016, 830, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, A.; Lawrence, L.; Lowry, G.; Kaltenegger, L. Probing the Limits of Habitability: A Catalog of Rocky Exoplanets in the Habitable Zone. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.14054. [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudhan, N.; Constantinou, S.; Holmberg, M.; Sarkar, S.; Piette, A.A.; Moses, J.I. New Constraints on DMS and DMDS in the Atmosphere of K2-18 b from JWST MIRI. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2025, 983, L40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedau, M.A.; Cleland, C.E. The nature of life; Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Henson, A.; Gutierrez, J.M.P.; Hinkley, T.; Tsuda, S.; Cronin, L. Towards heterotic computing with droplets in a fully automated droplet-maker platform. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2015, 373, 20140221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L.; Berg, M.; Krismer, M.; Saghafi, S.T.; Cosby, J.; Sankari, T.; Vetsigian, K.; Cleaves, H.J.; Baum, D.A. Chemical ecosystem selection on mineral surfaces reveals long-term dynamics consistent with the spontaneous emergence of mutual catalysis. Life 2019, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, D.A.; Vetsigian, K. An experimental framework for generating evolvable chemical systems in the laboratory. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres 2017, 47, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagan, C. Definitions of life. In The Nature of Life: Classical and Contemporary Perspectives from Philosophy and Science; 2010; pp. 303–306. [Google Scholar]

- Knuuttila, T.; Loettgers, A. What are definitions of life good for? Transdisciplinary and other definitions in astrobiology. Biology & Philosophy 2017, 32, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szathmáry, E. The evolution of replicators. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2000, 355, 1669–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; McCormick, W.D.; Pearson, J.E.; Swinney, H.L. Experimental observation of self-replicating spots in a reaction–diffusion system. Nature 1994, 369, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgman, C.E.; Jewett, M.C. Cell-free synthetic biology: thinking outside the cell. Metabolic engineering 2012, 14, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, D.; Zidovetzki, R.; Markovitch, O. Systems protobiology: origin of life in lipid catalytic networks. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2018, 15, 20180159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gánti, T. Chemoton theory: theory of living systems; Springer, 2003.

- Macía, J.; Solé, R.V. Protocell self-reproduction in a spatially extended metabolism–vesicle system. Journal of theoretical biology 2007, 245, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macia, J.; Solé, R.V. Synthetic Turing protocells: vesicle self-reproduction through symmetry-breaking instabilities. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2007, 362, 1821–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellermann, H.; Solé, R.V. Minimal model of self-replicating nanocells: a physically embodied information-free scenario. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2007, 362, 1803–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Huang, X.; Mann, S. Spontaneous Growth and Division in Self-Reproducing Inorganic Colloidosomes. Small 2014, 10, 3291–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellermann, H.; Rasmussen, S.; Ziock, H.J.; Solé, R.V. Life cycle of a minimal protocell—a dissipative particle dynamics study. Artificial Life 2007, 13, 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barge, L.M.; Cardoso, S.S.; Cartwright, J.H.; Cooper, G.J.; Cronin, L.; De Wit, A.; Doloboff, I.J.; Escribano, B.; Goldstein, R.E.; Haudin, F.; et al. From chemical gardens to chemobrionics. Chemical Reviews 2015, 115, 8652–8703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, S.S.; Cartwright, J.H.; Čejková, J.; Cronin, L.; De Wit, A.; Giannerini, S.; Horváth, D.; Rodrigues, A.; Russell, M.J.; Sainz-Díaz, C.I.; et al. Chemobrionics: From self-assembled material architectures to the origin of life. Artificial Life 2020, 26, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langton, C.G. Studying artificial life with cellular automata. Physica D: nonlinear phenomena 1986, 22, 120–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, L.S. Self-reproducing machines. Scientific American 1959, 200, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morowitz, H.J. A model of reproduction. American Scientist 1959, 47, 261–263. [Google Scholar]

- Sole, R.V. Evolution and self-assembly of protocells. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2009, 41, 274–284. [Google Scholar]

- Stano, P.; Luisi, P.L. Achievements and open questions in the self-reproduction of vesicles and synthetic minimal cells. Chemical Communications 2010, 46, 3639–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noireaux, V.; Maeda, Y.T.; Libchaber, A. Development of an artificial cell, from self-organization to computation and self-reproduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 3473–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Hu, S.; Chen, X. Artificial cells: from basic science to applications. Materials today 2016, 19, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschi, S.; Ward, T.R.; Meier, W.P.; Müller, D.J.; Fotiadis, D. Synthetic biology: bottom-up assembly of molecular systems. Chemical Reviews 2022, 122, 16294–16328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).