Introduction

Dental resin composites have become the cornerstone of modern restorative dentistry due to their excellent esthetic qualities, favorable mechanical performance, and the ability to preserve tooth structure through minimally invasive preparations [

1]. Central to the success of composite restorations is the effectiveness of the adhesive systems that bond them to dentin. Dentin, however, presents unique challenges compared to enamel owing to its higher organic content, tubular structure, and intrinsic moisture [

2,

3]. The adhesion process primarily depends on the ability of resin monomers to infiltrate demineralized dentin and form a stable hybrid layer through micromechanical interlocking via resin tags within exposed collagen fibrils [

4]. Nonetheless, this hybrid layer remains the most vulnerable link in the adhesion chain, particularly over time, as hydrolytic degradation and enzymatic breakdown by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) compromise its integrity [

5,

6].

The progressive degradation of this hybrid layer has been directly associated with loss of bond strength, marginal leakage, postoperative sensitivity, and ultimately, restoration failure and secondary caries [

7,

8]. To mitigate these effects, extensive research has explored the incorporation of inorganic nanofillers into dental adhesives. These fillers are capable of enhancing the mechanical strength, reducing solubility and water sorption, and improving the interaction between adhesive resins and dentin [

9,

10]. Such additives contribute not only to reinforcing the adhesive matrix but also to stabilizing the collagen network within demineralized dentin, thereby limiting enzymatic degradation and preserving the hybrid layer [

11].

Among the most promising nanofillers studied in this regard is Graphene Oxide (GO). GO is a two-dimensional carbon-based nanomaterial derived from graphite via oxidative processes. Unlike pristine graphene, GO is rich in oxygen-containing functional groups—hydroxyl, epoxy, carboxyl, and carbonyl—that render it highly reactive and hydrophilic [

12,

13]. This property significantly enhances its dispersion within adhesive systems and improves its chemical interaction with both organic polymers and biological tissues such as dentin [

14]. The high surface area and mechanical strength of GO also make it a suitable reinforcement agent in composite materials. Prior research by Bin-Shuwaish et al. and Mei et al. demonstrated that the inclusion of GO nanoparticles significantly improved the compressive strength, hardness, and antibacterial activity of experimental adhesive formulations [

15,

16]. Moreover, the presence of GO at the dentin-adhesive interface has been shown to decrease microleakage and improve marginal adaptation by minimizing polymerization shrinkage and increasing the degree of conversion [

17,

18].

In addition to mechanical reinforcement, improving the bioactivity of adhesives is another essential goal. Hydroxyapatite (HA), the primary inorganic component of natural tooth structure, is a non-toxic, bioactive material with high biocompatibility and remineralizing potential [

19]. In nanoparticle form, HA exhibits enhanced surface area and reactivity, facilitating its integration into adhesive systems. Studies suggest that HA nanoparticles can penetrate dentinal tubules and intertubular regions, promoting remineralization and improving bond strength by forming stable chemical and mechanical interactions at the resin-dentin interface [

20]. According to Leutine et al. and others, the incorporation of nano-HA enhances the bonding capability of adhesives while simultaneously aiding in the preservation of collagen fibrils by promoting mineral deposition around them [

21,

22]. Furthermore, HA is known to reduce nanoleakage and strengthen the hybrid layer by replacing water in the collagen matrix with apatite crystals, potentially increasing the longevity of resin-dentin bonds to over a decade [

23].

Despite the individually promising attributes of GO and HA, few studies have evaluated their combined effect within a single adhesive formulation. The rationale behind such a combination lies in the potential synergistic interaction between the reinforcing ability of GO and the remineralizing, collagen-stabilizing properties of HA. GO’s functional groups can serve as nucleation sites for HA deposition, thereby promoting organized mineral growth and hybrid layer stability. Moreover, the presence of GO may improve the dispersion and homogeneity of HA particles within the adhesive matrix, preventing agglomeration and optimizing filler performance. Collectively, these interactions may enhance the micromechanical retention, chemical stability, and sealing ability of the adhesive system [

24,

25].

From a clinical standpoint, the incorporation of both GO and HA could offer substantial improvements in long-term restoration success by reducing microleakage, improving the degree of conversion, increasing bond strength, and preventing collagen degradation. This is particularly relevant in deep dentin areas where adhesive performance is typically compromised due to excessive moisture, lower mineral content, and higher tubular density [

26]. It is also crucial to note that standard adhesive protocols—whether based on etch-and-rinse or self-etch strategies—are often unable to completely infiltrate interfibrillar collagen spaces or displace all water content, contributing to the formation of nanoleakage channels [

27]. These limitations further underscore the need for advanced adhesive formulations that can physically reinforce the resin matrix and chemically stabilize the dentin interface.

Recent developments in adhesive nanotechnology and biomimetic materials suggest that dual-modification of adhesives using both 2% GO and 5% HA may provide an optimal balance between mechanical durability and biological compatibility. However, to validate this hypothesis, empirical evaluation through standardized testing protocols is required.

Thus, the current study aims to evaluate and compare the effect of 2% graphene oxide (GO) and 5% hydroxyapatite (HA) nanoparticles, both individually and in combination, on the micro-tensile bond strength (µTBS) and microleakage behavior of a fifth-generation dental adhesive system. This dual-objective study utilizes µTBS testing to quantify bonding performance and confocal laser scanning microscopy to assess dye penetration and leakage at the adhesive-dentin interface. By integrating mechanical and biological nanofillers, this research seeks to determine whether the synergistic modification of adhesive systems can significantly enhance bond durability and sealing efficiency, potentially setting the stage for more predictable and long-lasting restorative outcomes.

Materials and Methodology

Type of Study

This study was an in vitro experimental study conducted over two years (2022–2024) and adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Ethical Committee (Approval No. DMIMS(DU)/IEC/2023/584).

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was calculated using SPSS 21.0 and ClinCalc software, with reference to the study by Yasser et al.[

17], considering the mean microleakage of fifth-generation adhesives. A power of 80% and a 95% confidence interval determined that the minimum sample size per group was 18, resulting in a total of 84 extracted human premolars used in the study for microtensile bond strength evaluation and 36 premolars for interface study evaluation.

Sample Source and Selection Criteria

Eighty-four extracted single-rooted maxillary premolars were obtained from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, SPDC, DMIHER, Wardha, following informed consent from patients and/or their legal guardians.

Exclusion Criteria:

Teeth with extensive caries, restorations, root canal treatments, fluorosis, attrition, abrasion, enamel defects, internal/external resorption, or developmental anomalies.

Sample Preparation

1. Addition of Graphene oxide and Hydroxyapatite to the dentin Adhesive

For ten minutes at room temperature, a microvial filled with two millilitres of ethanol and graphene oxide powder (Nano Research Lab, Jamshedpur, India) will be sonicated in an ultrasonicator. This combination is going to be combined with the dentin adhesive. Prior to being sonicated for ten minutes in an ultrasonic bath, Resin will be combined with the nano-graphene oxide particles to form a homogenous mixture. An ultrasonic homogenizer that pulses on and off will be utilized at room temperature to homogenize the mixture for 60 seconds after sonication. After each use, using an ultrasonic homogenizer, the mixture will be re-homogenized to ensure that the graphene oxide scatters uniformly during storage. The resin's milliliter volume and the nanoparticles' milligram weight will be computed. The following formula will be used to determine 2.0 w/v % adhesive.

Weight/volume % = weight of solute/volume of solution *100

Yasser A. et al. used this methodology [

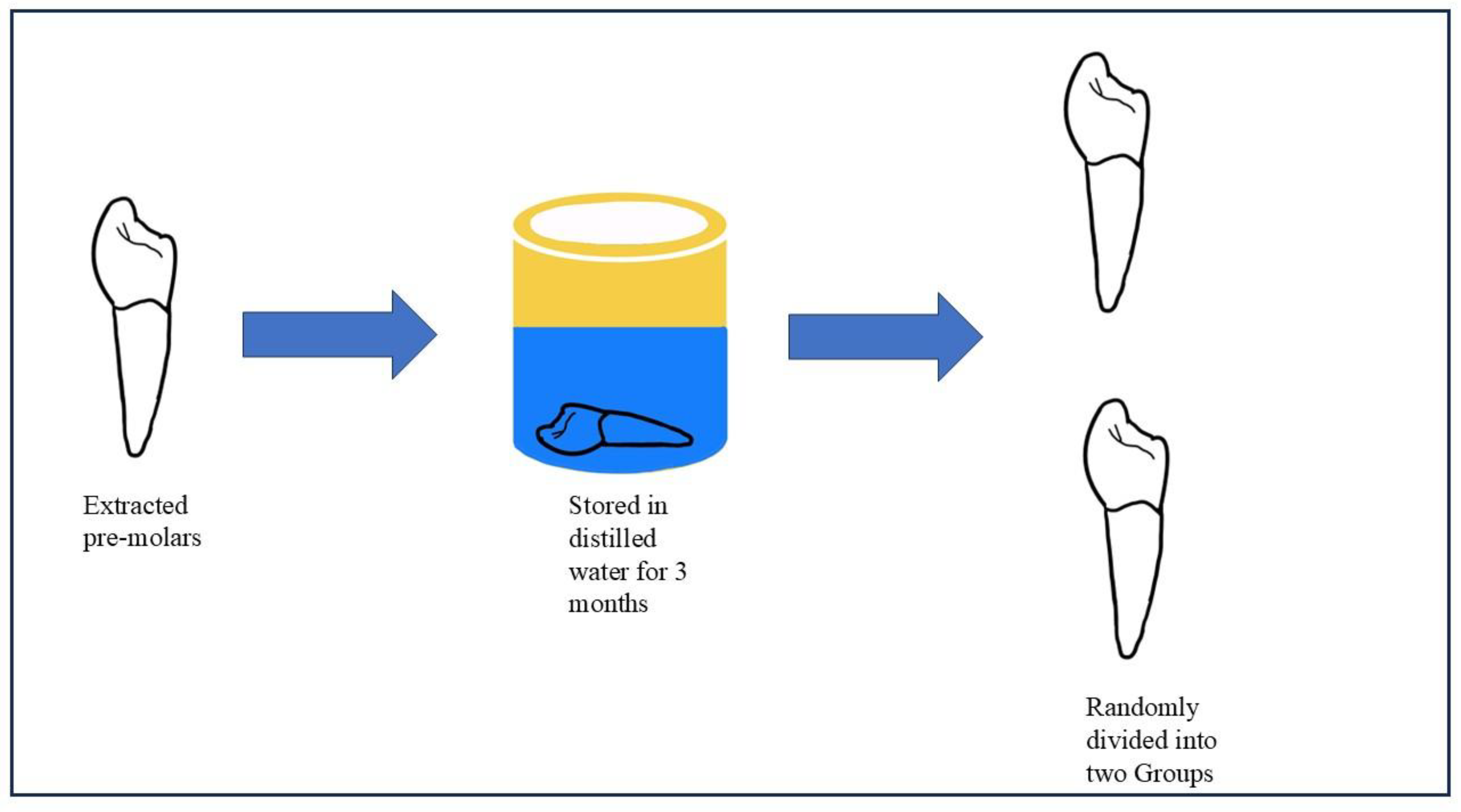

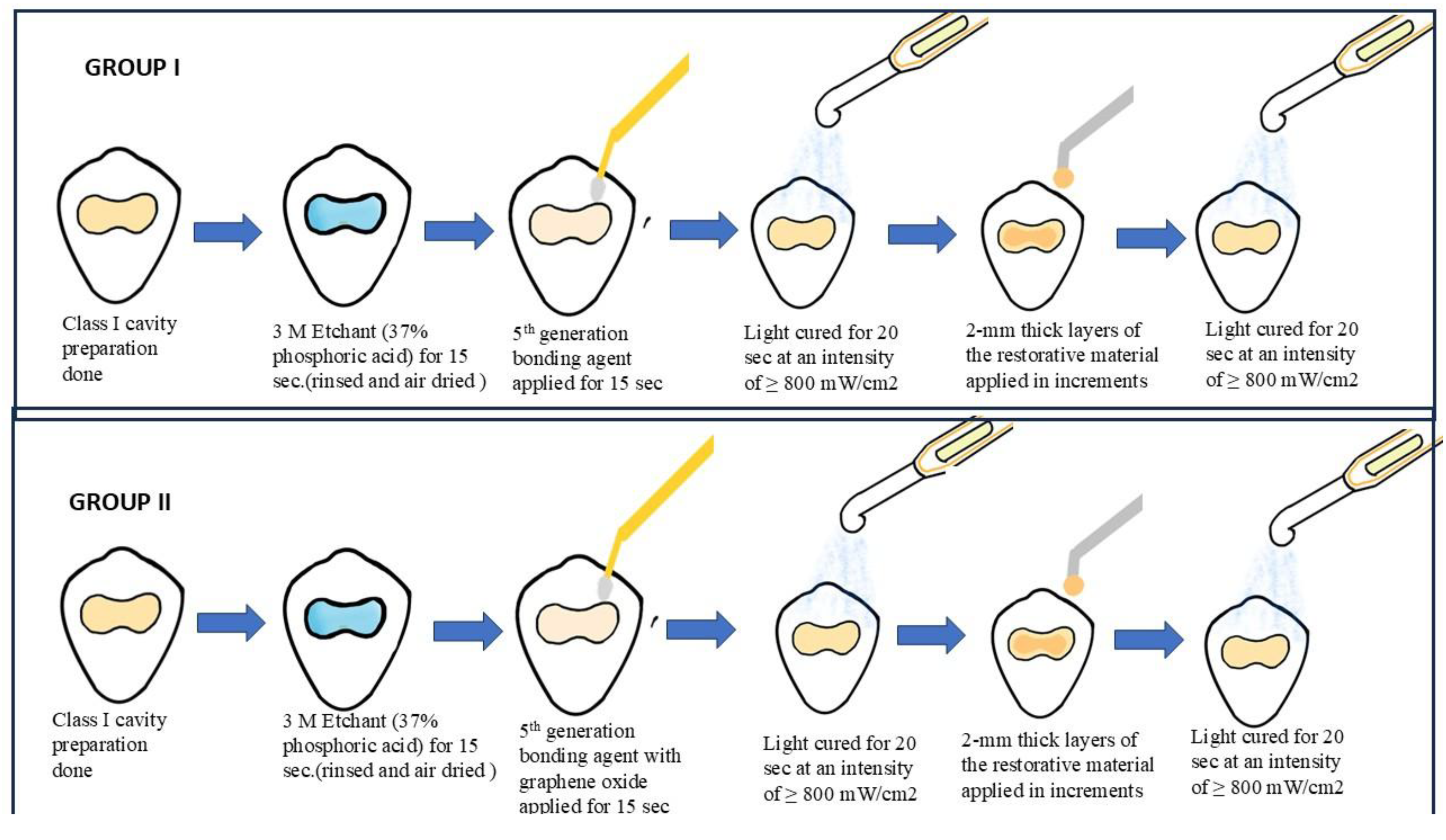

17]. Permanent maxillary premolars that have been extracted will be used in the study. For no more than three months, all teeth will be kept in distilled water. 36 premolars will be divided into two groups at random to represent the first and second sample sets. We will prepare the class 1 cavity. For 15 seconds, each group will be treated with 3 M Scotchbond Universal Etchant (30–40% phosphoric acid). After that, the surfaces will be cleaned and allowed to air dry. The excess glue will be scraped off using dental cotton rolls after the adhesive systems have been in place for 15 seconds. The surfaces will then be light-cured for 20 seconds at an intensity using a light-curing machine of at least 800 mW/cm2. Subsequent layers of the Dentsply Spectrum restorative material, each 2 mm thick, will be applied over the Previously, the adhesive layer was polymerized and light-cured for 20 seconds (

Figure 1 and

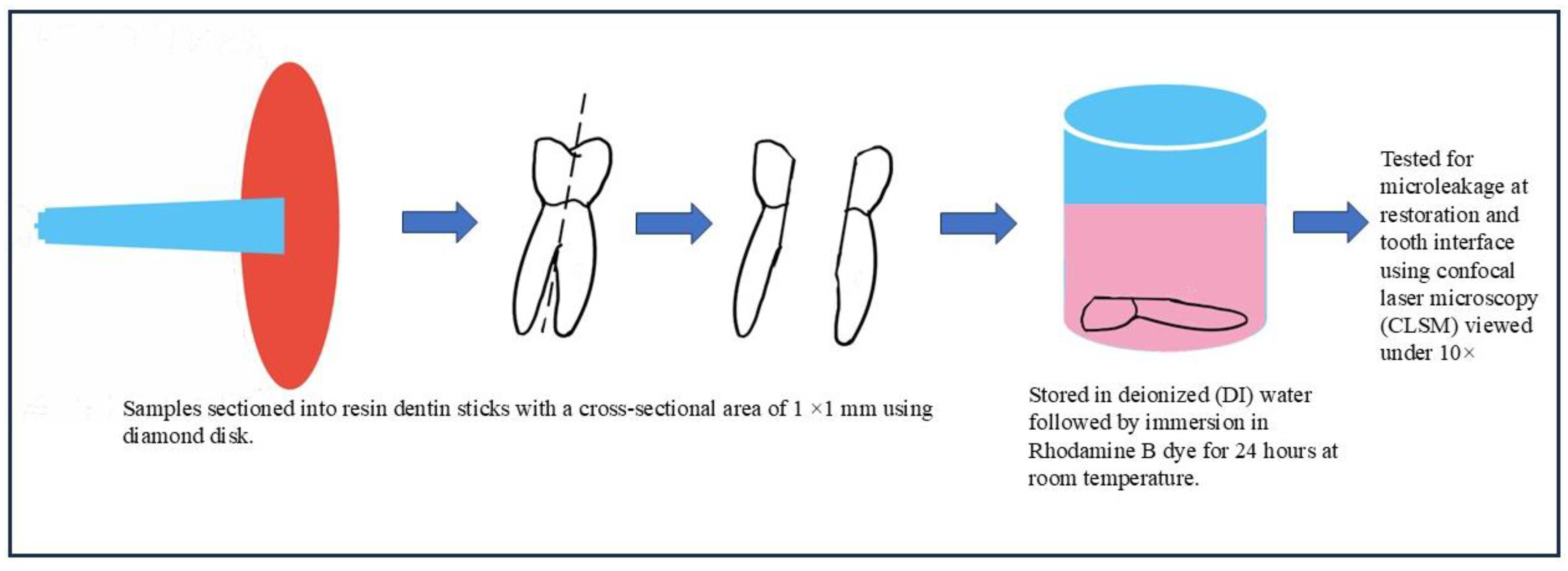

Figure 2). Every tooth will spend 48 hours submerged in 0.6% aqueous rhodamine B dye following a 24-hour immersion in 100% humidity at 37°C (

Figure 3). The subsequent steps of the method are well illustrated in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Sample Grouping

The specimens were randomly divided into four groups (n = 21 per group), for microtensile bond strength evaluation

Table 1.

Details of Groups and preparation procedure for confocal laser microscopy, interface evaluation.

Table 1.

Details of Groups and preparation procedure for confocal laser microscopy, interface evaluation.

| Group |

Composition |

| I |

5th Generation Bonding Agent (3M™ Single Bond Universal) |

| II |

5th Generation Bonding Agent + 2% Graphene Oxide (GO) |

| III |

5th Generation Bonding Agent + 5% Nano-Hydroxyapatite (HA) |

| IV |

5th Generation Bonding Agent + Combined GO and HA Nanoparticles |

Table 2.

Details of Groups and preparation procedure for confocal laser microscopy, interface evaluation.

Table 2.

Details of Groups and preparation procedure for confocal laser microscopy, interface evaluation.

| Group |

Manufacturer Details |

Preparation procedure/ Composition |

| Group I- 5th Generation Bonding agent |

- 3M™ Single Bond Universal Adhesive

- The Adper Single Bond 2 is a single-component adhesive agent, with stable nano filler that remains homogeneously distributed during dispersion. |

-Hydrophobic di methacrylates like bis-GMA, TEGDMA, and urethane methacrylates (UDMA)

- photoinitiator system

- Fillers: Silica particles

|

| Group II- 5th Generation Bonding agent with Graphene oxide nano-particles |

- Nano Research Lab, Jamshedpur India

Purity 98-99%

- Average number of Layer: 2-6

- Diameter: <100nm

- Thickness: 0.5-2 nm

- Color: Amber

- Bulk Density: 0.241g/cc |

- a micro vial filled with two milliliters of ethanol and graphene oxide powder was sonicated in an ultrasonicator.

- ultrasonic homogenizer was used after sonication for even consistency. |

Modification of Adhesives

1. Addition of Graphene Oxide to Dentin Adhesive (Groups II & IV)GO powder was dispersed in 2 mL ethanol and sonicated for 10 minutes at room temperature. This dispersion was added to the bonding agent and homogenized using an ultrasonic homogenizer (pulse on/off, 60 seconds). Re-homogenization was performed before each use. GO concentration was standardized at 2.0% w/v using:

2. Addition of Silanized Nano-Hydroxyapatite to Adhesive HA particles were silanized and incorporated at 5% m/m into the bonding agent. Homogeneous dispersion was ensured through sonication using a centrifuge, followed by 24-hour storage at 37°C and refrigeration at 4°C.

3. Combined GO + HA Adhesive The prepared GO solution was mixed with silanized HA, added to the adhesive, and sonicated for 10 minutes. Ultrasonic homogenization was applied for 60 seconds and re-homogenized before each use.

All adhesives were stored at 4°C and used within 20 days.

Cavity Preparation and Restoration

All 84 premolars were stored in distilled water for a maximum of three months before use. Standardized Class I cavities were prepared using a high-speed handpiece with water coolant. Etching was performed with 3M Scotchbond Universal Etchant (30–40% phosphoric acid) for 15 seconds, rinsed thoroughly, and gently air-dried. Adhesives were applied for 15 seconds, and excess removed using a dental cotton roll. Light curing was carried out for 20 seconds at ≥800 mW/cm².

Restoration was completed using Dentsply Spectrum composite in 2 mm increments, each light-cured for 20 seconds.

Testing Procedures

1. Microtensile Bond Strength (μ-TBS) TestingSpecimens were longitudinally sectioned into resin-dentin sticks (1 mm × 1 mm) using a diamond disk with water cooling, in accordance with ISO/TS 11405 guidelines. Samples were stored in deionized water at 37°C for 24 hours. Sticks were mounted to a jig with cyanoacrylate adhesive and subjected to tensile forces using a universal testing machine at 1 mm/min crosshead speed.

2. Restoration and tooth iterface TestingAfter restoration, samples were stored in 100% humidity at 37°C for 24 hours, then immersed in 0.6% rhodamine B dye for 48 hours. Teeth were sectioned buccolingually using a low-speed diamond disc under water cooling.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (10× magnification) was used to evaluate dye penetration at the dentinal interface. The microleakage scoring criteria by Mahajan et al.[

18] were employed:

Score 0: No dye penetration

Score 1: Dye penetrates up to half of the cervical wall

Score 2: Dye penetrates more than half or fully across cervical wall

Score 3: Dye reaches cervical and axial walls toward pulp

Figure 1.

Sample selection and storage.

Figure 1.

Sample selection and storage.

Figure 2.

Sample preparation and procedure performed.

Figure 2.

Sample preparation and procedure performed.

Figure 3.

Sample disking and immersion in dye.

Figure 3.

Sample disking and immersion in dye.

Figure 4.

Microtensile bond strength evaluation using Universal Testing Machine.

Figure 4.

Microtensile bond strength evaluation using Universal Testing Machine.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was determined using the Claincalc statistical software based on data from Yasser et al. [56], considering a significant effect size of 0.8 (large effect), a power of 80%, and a 95% confidence interval. The sample size calculation was derived using the formula:

Where:

Δ = absolute difference between two means

σ₁, σ₂ = standard deviations of groups

z₁₋ₐ/₂ = 1.96 (for α = 0.05)

z₁₋ᵦ = 0.84 (for 80% power)

k = ratio of sample sizes = 1

Substituting values:

n₁ = 21; n₂ = 21

Thus, the total sample size was calculated as 84, with 21 samples per group for microtensile bond strength evaluation and 36 total with 18 in each group for confocal laser microscopy evaluation.

After data collection, statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software, Version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage, were calculated for each group. The Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene’s test confirmed that the data followed a normal distribution. Accordingly, parametric tests were employed.

To assess differences among the groups, One-way ANOVA was applied. Post hoc analysis using Tukey’s HSD was carried out to determine pairwise group differences. A paired t-test was used where applicable for intra-group comparisons. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

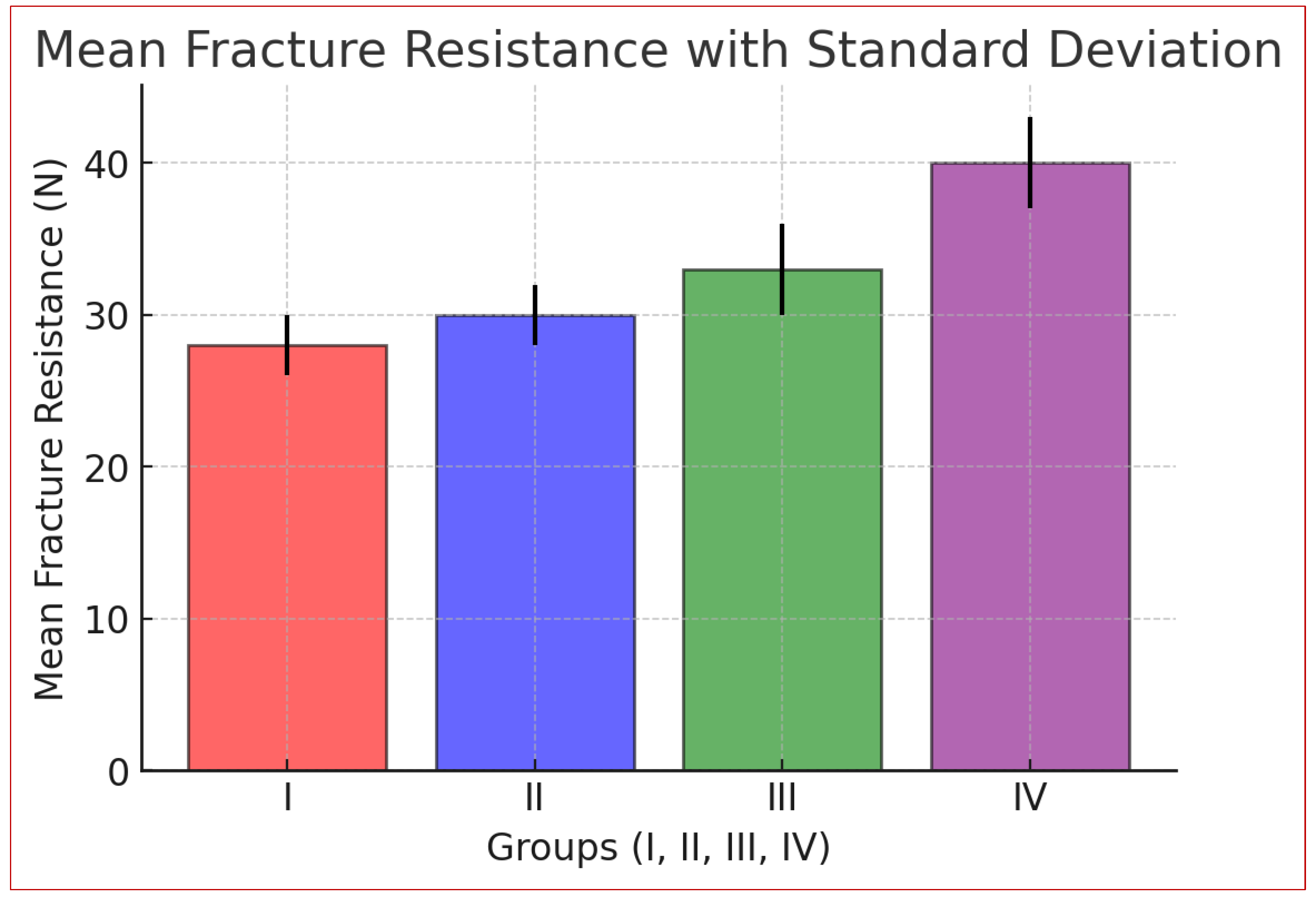

The statistical analysis (

Table 3) highlights significant differences in fracture resistance among the four groups. Group I (control) had the lowest mean (28.00 N), while Group IV (Graphene Oxide + Hydroxyapatite) had the highest (39.86 N). Variability was lower in Groups I and II (SD: 2.37, 2.07) and higher in Groups III and IV (SD: 4.38, 4.13), indicating more significant variation. ANOVA results confirmed statistical significance (F = 49.28, p = 3.85 × 10⁻¹⁸), rejecting the null hypothesis. Non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals further support these differences.

Fracture resistance followed the trend: Group IV > Group III > Group II > Group I.

Graph 1.

Mean distribution of micro tensile bond strength between Group I, Group II, Group III and Group IV.

Graph 1.

Mean distribution of micro tensile bond strength between Group I, Group II, Group III and Group IV.

The Mean Difference is Significant at the p <0.05 Level

The bar graph (Graph 1) illustrates the average microtensile strength among the four groups. Group IV exhibits the highest mean tensile strength (9.46 MPa), followed by Group III (8.42 MPa), Group II (7.74 MPa), and Group I (7.11 MPa). The results indicate a progressive increase in tensile strength from Group I to Group IV.

The Mean Difference is Significant at the p <0.05 Level

Table 4 shows no significant difference in fracture resistance between Group I and Group II (p = 0.2723) or between Group II and Group III (p = 0.0605), suggesting similar effects of Graphene Oxide and Hydroxyapatite when used separately. However, Group I and Group III differ significantly (p = 0.0002), indicating Hydroxyapatite enhances fracture resistance. A significant difference between Group III and Group IV (p < 0.0001) confirms the combined nanoparticles yield superior results. Group IV had the highest fracture resistance (p < 0.0001).

Findings of interface study using Confocal Laser Microscopy-

Pattern of Dye Penetration Microscopic analysis revealed a continuous route along the adhesive contact, indicating more dye penetration in the control collective. However, the graphene oxide experimental group showed very minor localized leakage around the adhesive-dentin contact, indicating minimal dye penetration. This implies that graphene oxide strengthened the bond, improving its capacity to seal and lowering the possibility of micro and nano leakage. The handling characteristics, viscosity, and curing time of the adhesive were all unaffected by the 2% graphene oxide addition. The handling characteristics of the control and graphene oxide-modified adhesives were comparable during application and cure. The experimental group showed no signs of adhesive deterioration or discoloration.

Assessment of Microleakage

The extent to which dye penetrates at the adhesive-dentin interface following treatment was measured to assess microleakage. To detect and quantify the degree of microleakage, the samples were first put through a normal dye penetration test before being seen under a confocal laser microscope.

1. Control Group (only using Fifth Generation Adhesive): There was a discernible level of microleakage in the control group, which included samples bonded using the fifth-generation glue without graphene oxide added. Significant adhesive failure and dye penetration at the dentin-adhesive interface were indicated by the control group's mean microleakage score of 27 ±2 um (mean ± standard deviation).

2. Adhesive Modified by Graphene Oxide (2% GO): The experimental group that had 2% graphene oxide added to the adhesive showed a notable decline in microleakage. If we compare the control group, the graphene oxide group's average microleakage score was substantially lower (p-value < 0.05), at Y mm (10 ± 2) in it. This implies that the fifth-generation adhesive's resistance to microleakage was greatly increased by adding 2% graphene oxide.

Discussion

Dental adhesives are essential in restorative dentistry to ensure the longevity and retention of restorations. Enhancing the bond between restorative materials and tooth substrates is crucial for durability and preventing issues like debonding, secondary caries, and microleakage [

35]. Stronger and more resilient adhesives are still needed to withstand the oral environment, particularly in complex cavity geometries where adhesive-dentin interaction is challenging. Conventional adhesives deteriorate over time due to mechanical stress and moisture exposure, necessitating innovations in adhesive formulations [

36].

Nanoparticles have been explored to improve adhesive properties. Graphene oxide (GO) has exceptional mechanical strength, a large surface area, and stable nanocomposite formation, making it valuable in dentistry. GO’s hydrophilicity, due to its oxygen-containing functional groups, enhances water resistance and micro-tensile bond strength (μTBS). Hydroxyapatite (HA), resembling the mineral composition of dentin and enamel, improves bonding and promotes remineralization, playing a crucial role in dental adhesion enhancement.

Studies on the individual effects of GO and HA in adhesives exist, but their combined influence is less explored. Particle size and filler quantity impact adhesive performance, with excessive filler (above 10%) reducing bond strength due to increased viscosity. The study incorporated 2% GO and 5% HA to balance reinforcement without compromising adhesion. The selection of these concentrations aimed to maintain adhesive fluidity while maximizing mechanical reinforcement and chemical interaction with dentin.

Micro-TBS testing provided accurate bond strength assessment, revealing significant differences among groups. ANOVA variance analysis confirmed statistical significance, with Group IV (GO + HA) outperforming all groups (p < 0.001). The post hoc Tukey test showed Group IV had the highest bond strength, while the control (Group I) had the lowest due to the absence of nanoparticles. This suggests that traditional adhesives lack the reinforcement properties that nanoparticles provide, making them more prone to degradation over time.

Group II (GO 2%) improved bond strength but not significantly compared to the control. However, GO’s ability to enhance mechanical properties and resist water absorption suggests it contributes to a more durable adhesive interface. Group III (HA 5%) showed significant improvement, likely due to HA’s bioactivity enhancing chemical bonding. HA’s similarity to tooth mineral composition allows for better integration with dentin, promoting remineralization and strengthening the adhesive interface. However, neither GO nor HA alone matched the effectiveness of their combination.

Group IV exhibited the highest bond strength due to GO’s stress distribution properties and HA’s mineral interaction, confirming a synergistic effect. The combination of nanoparticles likely improved both mechanical interlocking and chemical bonding, leading to superior adhesive performance. These findings align with previous studies indicating that the incorporation of nanofillers into dental adhesives enhances bond strength, durability, and overall performance.

Previous studies support these results, showing GO enhances primer bonding and HA improves remineralization. However, excessive HA can lead to aggregation, weakening mechanical properties by creating stress points within the adhesive matrix. GO’s ability to reinforce epoxy matrices and prevent crack propagation further supports its role in adhesive performance. Graphene’s unique structural characteristics, including its high aspect ratio and mechanical resilience, contribute to improved stress distribution, minimizing microcracks and enhancing adhesive longevity [

38].

Graphene-based adhesives face challenges, such as reduced curing depth due to light absorption and aggregation hindering polymerization. The dispersion of graphene nanoparticles within the adhesive matrix is crucial to ensure uniform distribution and prevent agglomeration, which can negatively impact adhesive strength. However, optimizing GO-HA ratios can enhance properties while maintaining bioactivity. This study indicates that careful formulation adjustments can mitigate these challenges, allowing for improved adhesive performance without compromising polymerization [

39,

40]..

GO’s structural reinforcement and HA’s biocompatibility create a stronger dentin bond, improving long-term restoration stability. GO’s ability to interact with polymer chains and enhance cross-linking contributes to increased adhesive integrity [

41]. Meanwhile, HA facilitates remineralization at the dentin interface, reinforcing the bond over time and preventing degradation. The dual benefits of mechanical reinforcement and bioactivity highlight the potential of GO-HA formulations in next-generation dental adhesives [

42].

Clinically, stronger adhesive bonds improve restoration durability, particularly in high-stress areas such as occlusal surfaces subjected to significant masticatory forces. HA nanoparticles enhance stress absorption and ion release, strengthening dentin-resin connections [

43,

44]. The controlled release of calcium and phosphate ions promotes remineralization, reducing the likelihood of secondary caries and improving long-term adhesive performance. Additionally, GO exhibits antibacterial properties, effectively inhibiting Streptococcus mutans at low concentrations, further supporting its use in adhesives. The antimicrobial nature of GO reduces bacterial adhesion, potentially decreasing the risk of biofilm formation and recurrent decay [

45].

While some studies report inconsistent results regarding GO’s impact on bond strength, differences in filler particle treatment and interactions with adhesive matrices may explain variations. The surface modification of nanoparticles, such as silanization, can significantly influence their compatibility with adhesive resins and ultimately affect performance. Further studies are needed to establish optimal processing techniques that ensure consistent adhesive enhancement across different formulations [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

This study suggests that integrating GO and HA into dental adhesives significantly improves mechanical properties and clinical efficacy. By leveraging the reinforcing capabilities of GO and the bioactive properties of HA, these nanoparticles offer a promising strategy for enhancing dental adhesives. These findings contribute to the ongoing development of nanoparticle-infused adhesives, supporting further research for optimal formulations and long-term clinical success. Future investigations should focus on refining nanoparticle dispersion techniques, evaluating long-term stability under intraoral conditions, and exploring additional functional properties that may further enhance adhesive performance.

Conclusion

The addition of 2 wt% graphene oxide (GO) and 5 wt% hydroxyapatite (HA) nanoparticles to 5th-generation adhesives significantly enhances microtensile bond strength (µTBS), achieving the highest values (39.81 ± 2.81 MPa) due to their synergistic effects. HA promotes remineralization and biocompatibility, while GO enhances structural reinforcement, durability, and water resistance. This combination outperforms GO (34.78 ± 2.61 MPa) or HA (32.12 ± 2.52 MPa) alone. However, excessive nanoparticle loading (>10 wt%) may increase viscosity, reducing dentin penetration. The optimized 2 wt% GO–5 wt% HA formulation offers a promising approach for durable, high-performance dental restorations with superior mechanical and adhesive properties. When 2% graphene oxide was added to the fifth-generation adhesive, microleakage was notably lower than in the control group. This implies that graphene oxide might be a useful ingredient to improve dental adhesives' sealing qualities and lower the chance of secondary caries and bacterial penetration.

Author Contributions

Simran Kriplani (SK), Aditi Jain (AJ), and Shweta Sedani (SS) performed the methodology and wrote the manuscript. Mohammed Mustafa (MM), Abdullah Mohammed Alshehri (AMA), Nasser Raqe Alqhtani (NRA), and Ali Robaian Alqahtani (ARA) revised it, and Khalid K. Alanazi (KKA), Mohammed Almuhaiza (MA), and Saleh Alhindi (SA) supervised it. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no funding was received to conduct this study.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines, and approval was obtained from the appropriate institutional ethics committee.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained on 06/02/2023 by the Institutional Ethical Committee of Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, with ethical approval number DMIMS(DU)/IEC/2023/ 584.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants / relevant authorities for using extracted human teeth in this research.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The author(s) have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Clinical significance and Future perspective

Information from the study can be used to determine which material will work best for dentin adhesives by reducing bacterial leakage. Future research on graphene oxide nanoparticles' beneficial mechanical, biological, and physical characteristics in the dental sector can be conducted.

Abbreviations

GO- Graphene oxide

MMPs- Matrix Metalloproteinase

Bis-GMA- Bis phenol A glycidyl methacrylate

TEG-DMA- Tri ethylene glycol dimethacrylate

References

- Aguiar TR, Francescantonio MD, Arrais CA, Ambrosano GM, Davanzo C, Giannini M. Influence of curing mode and time on degree of conversion of one conventional and two self-adhesive resin cements. Oper Dent. 2010, 35, 295–9.

- Al-Hamdan RS, Almutairi B, Kattan HF, Alresayes S, Abduljabbar T, Vohra F. Assessment of hydroxyapatite nanospheres incorporated dentin adhesive: a SEM/EDX, micro-Raman, microtensile, and micro-indentation study. Coatings. 2020, 10, 1181.

- Alshahrani A, Bin-Shuwaish MS, Al-Hamdan RS, Almohareb T, Maawadh AM, Al Deeb M, et al. Graphene oxide nano-filler based experimental dentine adhesive. A SEM / EDX, Micro-Raman and microtensile bond strength analysis. J Appl Biomater Funct Mater. 2020, 18, 2280800020966936.

- Aradhana R, Mohanty S, Nayak SK. Comparison of mechanical, electrical and thermal properties in graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide filled epoxy nanocomposite adhesives. Polymer. 2018, 141, 109–23.

- Baig MS, Fleming GJ. Conventional glass-ionomer materials: A review of the developments in glass powder, polyacid liquid and the strategies of reinforcement. J Dent. 2015, 43, 897–912.

- Bin-Shuwaish MS, Maawadh AM, Al-Hamdan RS, Alresayes S, Ali T, Almutairi B, et al. Influence of graphene oxide filler content on the dentin bond integrity, degree of conversion and bond strength of experimental adhesive. A SEM, micro-Raman, FTIR and microtensile study. Mater Res Express. 2020, 7, 115403.

- Bregnocchi A, Zanni E, Uccelletti D, Marra F, Cavallini D, De Angelis F, et al. Graphene-based dental adhesive with anti-biofilm activity. J Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 15, 89.

- Breschi L, Maravic T, Cunha SR, Comba A, Cadenaro M, Tjäderhane L, et al. Dentin bonding systems: from dentin collagen structure to bond preservation and clinical applications. Dent Mater. 2018, 34, 78–96.

- Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Ruggeri A, Cadenaro M, Di Lenarda R, De Stefano Dorigo E. Dental adhesion review: aging and stability of the bonded interface. Dent Mater. 2008, 24, 90–101.

- Cho BH, Dickens SH. Effects of the acetone content of single solution dentin bonding agents on the adhesive layer thickness and the microtensile bond strength. Dent Mater. 2004, 20, 107–15.

- Conde MC, Zanchi CH, Rodrigues-Junior SA, Carreno NL, Ogliari FA, Piva E. Nanofiller loading level: influence on selected properties of an adhesive resin. J Dent. 2009, 37, 331–5.

- Czasch P, Ilie N. In vitro comparison of mechanical properties and degree of cure of bulk fill composites. Clin Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 227–35.

- Daood U, Heng CS, Lian JN, Fawzy AS. In vitro analysis of riboflavin-modified, experimental, two-step etch-and-rinse dentin adhesive: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and micro-Raman studies. Int J Oral Sci. 2015, 7, 110–24.

- de Almeida Neves A, Coutinho E, Cardoso MV, Lambrechts P, Van Meerbeek B. Current concepts and techniques for caries excavation and adhesion to residual dentin. J Adhes Dent. 2011, 13, 7–22.

- Deshmukh K, Ahamed MB, Deshmukh RR, Pasha SK, Chidambaram K, Sadasivuni KK, et al. Eco-friendly synthesis of graphene oxide reinforced hydroxypropyl methylcellulose/polyvinyl alcohol blend nanocomposites filled with zinc oxide nanoparticles for high-k capacitor applications. Polym Plast Technol Eng. 2016, 55, 1240–53.

- Emami N, Sjödahl M, Söderholm KJ. How filler properties, filler fraction, sample thickness and light source affect light attenuation in particulate filled resin composites. Dent Mater. 2005, 21, 721–30.

- Farooq I, Moheet IA, AlShwaimi E. In vitro dentin tubule occlusion and remineralization competence of various toothpastes. Arch Oral Biol. 2015, 60, 1246–53.

- Ferracane, JL. Models of caries formation around dental composite restorations. J Dent Res. 2017, 96, 364–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagno L, Sarno M, Vietri U, Raimondo M, Cirillo C, Ciambelli P. Graphene-based structural adhesive to enhance adhesion performance. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27874–86.

- Huang B, Siqueira WL, Cvitkovitch DG, Finer Y. Esterase from a cariogenic bacterium hydrolyzes dental resins. Acta Biomater. 2018, 71, 330–8.

- Kalachandra, S. Influence of fillers on the water sorption of composites. Dent Mater. 1989, 5, 283–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavrik F, Kucukyilmaz E. The effect of different ratios of nano-sized hydroxyapatite fillers on the micro-tensile bond strength of an adhesive resin. Microsc Res Tech. 2019, 82, 538–43.

- Kim YK, Gu L, Bryan TE, Kim JR, Chen L, Liu Y, et al. Mineralisation of reconstituted collagen using polyvinylphosphonic acid/polyacrylic acid templating matrix protein analogues. Biomaterials. 2010, 31, 6618–27.

- Lee JH, Jo JK, Kim DA, Patel KD, Kim HW, Lee HH. Nano-graphene oxide incorporated into PMMA resin to prevent microbial adhesion. Dent Mater. 2018, 34, e63–72.

- Lee SM, Yoo KH, Yoon SY, Kim IR, Park BS, Son WS, et al. Enamel anti-demineralization effect of orthodontic adhesive containing bioactive glass and graphene oxide: an in-vitro study. Materials. 2018, 11, 1728.

- Leitune VCB, Collares FM, Trommer RM, Andrioli DG, Bergmann CP, Samuel SMW. The addition of nanostructured hydroxyapatite to an experimental adhesive resin. J Dent. 2013, 41, 321–7.

- Liu Y, Tjäderhane L, Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Li N, Mao J, et al. Limitations in bonding to dentin and experimental strategies to prevent bond degradation. J Dent Res. 2011, 90, 953–68.

- Matinlinna JP, Lassila LV, Ozcan M, Yli-Urpo A, Vallittu PK. An introduction to silanes and their clinical applications in dentistry. Int J Prosthodont. 2004, 17, 155–64.

- Mei L, Wei H, Wenjing C, Xiaokun H. Graphene oxide-silica composite fillers into the experimental dental adhesives for potential therapy. Med Res J. 2017, 1, 42.

- Mjör IA, Shen C, Eliasson ST, Richter S. Placement and replacement of restorations in general dental practice in Iceland. Oper Dent. 2002, 27, 117–23.

- Nakabayashi, N. The hybrid layer: a resin-dentin composite. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1992;88 Suppl 1:321–9.

- Nakabayashi N, Nakamura M, Yasuda N. Hybrid layer as a dentin-bonding mechanism. J Esthet Dent. 1991, 3, 133–8.

- Nuvoli D, Alzari V, Sanna R, Scognamillo S, Alongi J, Malucelli G, et al. Synthesis and characterization of graphene-based nanocomposites with potential use for biomedical applications. J Nanopart Res. 2013, 15, 1512.

- Van Landuyt KL, De Munck J, Mine A, Cardoso MV, Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B. Fifty-five years of dentin adhesion (1956–2011): Review of literature and bibliography of dental adhesives. Dent Mater. 2012, 28, e1–e16.

- Pashley DH, Tay FR, Yiu C, Hashimoto M, Breschi L, Carvalho RM, et al. Collagen degradation by host-derived enzymes during aging. J Dent Res. 2004, 83, 216–21.

- Poggio C, Beltrami R, Colombo M, Ceci M, Chiesa M. Nanotechnology in restorative dentistry: a review of the literature. Minerva Stomatol. 2015, 64, 97–109.

- Prasansuttiporn T, Nakashima S, Nikaido T, Foxton RM, Tagami J. Bonding durability of all-in-one adhesives on dentin using different bonding and aging techniques. Dent Mater J. 2011, 30, 695–702.

- Reis A, Loguercio AD, Azevedo CL, de Carvalho RM. Microtensile bond strength of resin cement to primary and permanent dentin. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004, 71, 315–20.

- Sano H, Yoshiyama M, Ebisu S, Burrow MF, Takatsu T, Ciucchi B, et al. Comparative SEM and TEM observations of nanoleakage within the hybrid layer. Oper Dent. 1995, 20, 160–7.

- Sauro S, Osorio R, Watson TF, Toledano M. Influence of a collagen cross-linking agent on dentin bonding. J Dent Res. 2010, 89, 553–8.

- Sideridou ID, Karabela MM. Effect of the amount of 1,6-hexanediol dimethacrylate monomer on some properties of dental light-cured resin composites. Dent Mater. 2009, 25, 1315–24.

- Soares CJ, Silva NR, Fonseca RB. Influence of polymerization shrinkage on stress development and gap formation in resin-composite restorations. Braz Dent J. 2007, 18, 303–10.

- Spencer P, Ye Q, Park J, Topp EM, Misra A, Marangos O, et al. Adhesive/dentin interface: the weak link in the composite restoration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010, 38, 1989–2003.

- Tay FR, Pashley DH. Water treeing—a potential mechanism for degradation of dentin adhesives. Am J Dent. 2003, 16, 6–12.

- Tay FR, Pashley DH. Have dentin adhesives become too hydrophilic? J Can Dent Assoc. 2003, 69, 726–31.

- Tay FR, Pashley DH. Aggressiveness of contemporary self-etching systems. I: Depth of penetration beyond dentin smear layers. Dent Mater. 2001, 17, 296–308.

- Tay FR, Pashley DH, Loushine RJ, Weller RN, Monticelli F, Osorio R, et al. Self-etching adhesives increase collagenolytic activity in radicular dentin. J Endod. 2006, 32, 862–8.

- Tay FR, Pashley DH, Yiu C, Sanares AME, Wei SHY. Factors contributing to the incompatibility between simplified-step adhesives and chemically-cured or dual-cured composites. Part I. Single-step self-etching adhesive. J Adhes Dent. 2003, 5, 27–40.

- Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Agee KA, Hoshika T, Carrilho M, Breschi L, Tjäderhane L, et al. The requirement of zinc and calcium ions for functional MMP activity in demineralized dentin matrices. Dent Mater. 2010, 26, 1059–67.

- Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Agee KA, Hoshika T, Tay FR, Breschi L, Tjäderhane L, et al. Carbodiimide cross-linking inactivates soluble and matrix-bound MMPs, in vitro. J Dent Res. 2010, 89, 604–9.

- Tjäderhane L, Nascimento FD, Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Tersariol IL, Geraldeli S, et al. Optimizing dentin bond durability: control of collagen degradation by matrix metalloproteinases and cysteine cathepsins. Dent Mater. 2013, 29, 116–35.

- Van Landuyt KL, Snauwaert J, Peumans M, De Munck J, Lambrechts P, Van Meerbeek B. The role of HEMA in one-step self-etch adhesives. Dent Mater. 2008, 24, 1412–9.

- Wang Y, Spencer P. Physicochemical interactions at the interfaces between self-etch adhesive systems and dentin. J Dent. 2004, 32, 567–79.

- Yiu CK, King NM, Carrilho MR, Sauro S, Rueggeberg FA, Prati C, et al. Effect of resin hydrophilicity and ethanol wet bonding on adhesion to dentin. J Adhes Dent. 2006, 8, 293–300.

- Yasser, F. AlFawaz Dentin Bond Integrity of Hydroxyapatite Containing Resin Adhesive Enhanced with Graphene Oxide Nano-Particles—An SEM, EDX, Micro-Raman, and Microtensile Bond Strength Study, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).