1. Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most common malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide. In 2020 alone, more than 2.3 million women were diagnosed with breast cancer, and approximately 685,000 women died from the disease globally. While advances in early detection and targeted therapy have significantly improved outcomes for many breast cancer subtypes, prognosis and recurrence risk vary markedly according to molecular subtype. This classification is based on the presence or absence of hormone receptors—estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PgR)—and the amplification or overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is defined by the absence of ER and PgR expression and the lack of HER2 overexpression or amplification. TNBC accounts for approximately 15–20 % of all breast cancers, both globally and in Japan, and is disproportionately associated with younger age at diagnosis, higher histologic grade, and more aggressive clinical behavior. TNBC is characterized by early recurrence, frequent visceral and central nervous system metastases, and overall poorer survival compared with other subtypes [

1,

2,

3].

A systematic review by Morgan et al., involving over 280,000 breast cancer patients, demonstrated that hormone receptor–negative disease—including TNBC—carries a significantly higher risk of recurrence than hormone receptor–positive subtypes, regardless of follow-up duration [

1]. The biological aggressiveness of TNBC is reflected in its higher proliferative index, frequent TP53 mutations, and enrichment for basal-like gene expression profiles. Unlike hormone receptor-positive breast cancers, TNBC lacks well-established targeted therapies, leaving chemotherapy as the mainstay of treatment for many years.

Recent advances in cancer immunology have introduced immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) as a promising therapeutic option in TNBC. These agents target inhibitory pathways, such as the programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) axis, and restore anti-tumor immunity. PD-L1 is expressed on tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating immune cells, serving as a critical immune checkpoint molecule. Its binding to PD-1 receptors on T cells suppresses cytokine release and proliferation, enabling tumor immune escape. In TNBC, PD-L1 expression assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a predictive biomarker for ICI efficacy. The phase III KEYNOTE-355 trial found pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) in PD-L1 positive metastatic TNBC, defined by a Combined Positive Score (CPS) ≥ 10 using the 22C3 pharmDx assay [

4]. Similarly, the IMpassion130 trial found enhanced PFS with atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel in PD-L1 positive TNBC, determined by the SP142 assay [

5]. These data have made PD-L1 testing a routine requirement for metastatic TNBC, directly influencing ICI eligibility.

However, PD-L1 testing accuracy is vulnerable to variability across pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical stages. Pre-analytical factors—such as cold ischemia time, fixation method/duration, fixative type, and processing protocols—significantly influence antigen preservation [

6]. Among these, storage conditions of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks remain underappreciated but critically important for assay fidelity. FFPE blocks are commonly archived and used for retrospective studies, often stored for years. Yet, evidence suggests prolonged storage may lead to antigen degradation, resulting in reduced immunoreactivity and potential false-negative IHC results [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Grillo et al. documented significant declines in immunoreactivity for multiple markers after >5 years storage [

7], while Engel and Moore underscored the sensitivity of antigenic epitopes to pre-analytical variables such as fixation and storage [

6]. A false-negative PD-L1 result due to storage degradation is particularly concerning in the context of ICI eligibility (e.g., CPS ≥10 in KEYNOTE-355) [

4]. The causes of false negatives are likely due to protein oxidation, hydrolysis, cross-linking, paraffin embedding effects, and environmental factors like humidity and temperature [

11,

12,

13]. Controlled low-temperature, low-humidity storage of slides has been suggested to mitigate such loss [

14].

This issue is especially relevant for PD-L1 as a predictive marker; false-negatives may inappropriately exclude patients from ICI treatment. Though previous studies reported storage-related degradation of markers like ER, PgR, Ki67, and HER2 [

7,

8,

9,

10], data specific to PD-L1 stability in archived FFPE, especially in TNBC, remain sparse and inconsistent.

Furthermore, PD-L1 positivity is associated with infiltrating lymphocytes and heightened proliferation [

15,

16,

17]. Schalper et al. associated PD-L1 mRNA with inflamed microenvironments and better outcomes [

18]. PD-L1 thus acts as both a prognostic and predictive marker [

4,

19,

20].

Most pathology labs store FFPE blocks long-term. Current ASCO/CAP guidelines do not specify storage limits [

10,

21]

We hypothesized that prolonged storage of FFPE TNBC samples reduces PD-L1 immunoreactivity (22C3 pharmDx assay). To test this, we retrospectively analyzed TNBC cases with PD-L1 testing at diagnosis and repeated testing of the same blocks after storage intervals (<1 year, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, ≥3 years). We examined associations with clinicopathologic features, pathologic complete response (pCR) post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), and survival outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Population

We retrospectively reviewed cases diagnosed as TNBC at our institution between April 1st, 2020, and March 31, 2024, in which PD-L1 expression was evaluated using the 22C3 antibody clone at the time of diagnosis. Only patients with available FFPE tissue blocks stored at room temperature were included.

Pathological Assessment at Diagnosis

At the time of diagnosis, pathological parameters including PD-L1 (22C3) status, nuclear grade (NG), ER, PgR, HER2, Ki67 proliferation index, and p53 mutation status were assessed based on routine pathology reports. Re-examination of original slides was not performed for this study, as prolonged storage of unstained slides can also result in decreased immunoreactivity [

7,

8].

FFPE Storage and Restaining

For evaluation of post-storage PD-L1 status, the original FFPE blocks stored at room temperature were sectioned, and new slides were prepared for PD-L1 IHC using the same 22C3 clone.

Tissue Fixation and Processing

Specimens from core needle biopsies or surgical resections were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 10–72 hours prior to paraffin embedding.

PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry (22C3 pharmDx)

PD-L1 staining was performed using the PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Four-micrometer-thick FFPE tissue sections were deparaffinized and processed on the Dako Autostainer Link 48 platform. Antigen retrieval was performed using EnVision FLEX Target Retrieval Solution (Low pH). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched, and sections were incubated with the mouse monoclonal anti–PD-L1 antibody (clone 22C3). Visualization was achieved using the EnVision FLEX visualization system, followed by hematoxylin counterstaining.

PD-L1 expression was quantified using the Combined Positive Score (CPS). The CPS is calculated as the number of PD-L1–positive cells, including tumor cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages, divided by the total number of viable tumor cells, multiplied by 100.

CPS ≥ 10 was considered positive, according to current guidelines [

6].

Classification of Storage Duration

FFPE storage duration was categorized as:

<1 year

1-2Years

2-3years

≥3 years

PD-L1 status changes were classified as:

Increased staining

No change

Decreased staining

Association with Clinicopathologic Factors

We examined correlations between PD-L1 changes and Ki67, NG, p53 mutation status, and pCR rate among NAC recipients. pCR was defined as the complete disappearance of invasive carcinoma in the breast, irrespective of residual ductal carcinoma in situ.

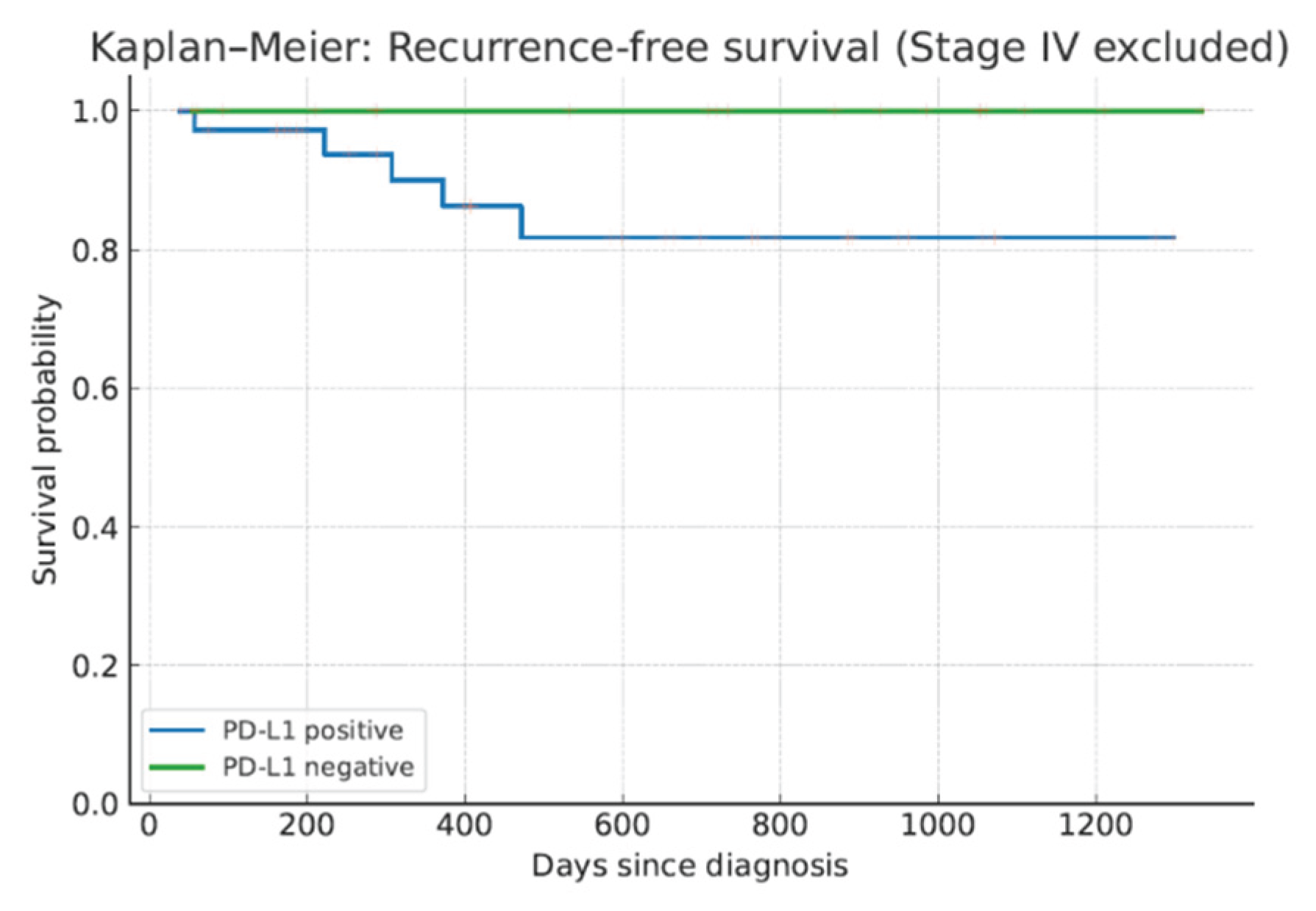

Survival Analysis

For patients with stage I–III disease, recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of recurrence, death, or last follow-up. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Logistic regression was used to explore associations between PD-L1 decline and clinicopathologic factors. Kaplan–Meier curves were compared using the log-rank test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 63 TNBC patients met the inclusion criteria. At diagnosis, 22 patients (34.9%) were PD-L1–negative (CPS < 10) and 41 patients (65.1%) were PD-L1–positive (CPS ≥ 10).

Table 1 summarizes the clinicopathologic characteristics.

Among PD-L1–negative cases, storage duration was ≥3 years in 9 patients (41%), 2–3 years in 9 (41%), 1–2 years in 2 (9%), and <1 year in 2 (9%). In PD-L1–positive cases, the respective distribution was 8 (20%), 16 (39%), 9 (22%), and 8 (20%).

Median Ki67 was significantly higher in PD-L1–positive cases than in PD-L1–negative cases (48.2% [20–99%] vs. 25.2% [7–90%], p = 0.00054). Nuclear grade was also significantly higher in PD-L1–positive cases, with grade 3 in 26 patients (63%) vs. grade 1 in 9 patients (41%) among PD-L1–negative cases (p = 0.0381). No significant association was observed between PD-L1 status and p53 mutation type (p = 0.075).

At diagnosis, distant metastases were present in 3 PD-L1–negative patients (14%) and 4 PD-L1–positive patients (10%). During follow-up, distant recurrence occurred in 5 PD-L1–positive patients (14%), of whom 3 (8%) died. No recurrences or deaths occurred in the PD-L1–negative group.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and pCR

NAC was administered to 11 PD-L1–negative patients (50%) and 15 PD-L1–positive patients (37%). Among PD-L1–positive patients, pCR was achieved in 5 of 15 (33%), compared to none in the PD-L1–negative group. The difference approached but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0527) (

Table 2). The results of chemotherapy regimens and treatment effects according to PD-L1 expression are shown in

Table 3. There were few ICI regimens and many dose-dense regimens.

No cases showed increased PD-L1 staining after storage. In PD-L1–positive patients, decreased staining occurred in 0% of cases stored <1 year, 11% (1/9) stored 1–2 years, 13% (2/16) stored 2–3 years, and 50% (4/8) stored ≥3 years. The association between longer storage duration and PD-L1 decline was statistically significant (p = 0.015). In PD-L1–negative patients, no change in staining was observed regardless of storage duration.

Survival Outcomes

Due to the limited number of events, survival analysis did not reach statistical significance; however, a trend toward shorter RFS (

p=0.096, log-rank test) and OS (

p=0.183, log-rank test) was observed in PD-L1–positive patients. (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

In this comprehensive retrospective analysis, we demonstrated that prolonged storage of FFPE TNBC specimens—particularly beyond three years—is significantly associated with reduced PD-L1 immunoreactivity using the 22C3 pharmDx assay. Approximately 50 % of long-stored samples exhibited decreased staining compared to no decline in samples stored for less than one year, and no cases showed increased positivity post-storage. Importantly, PD-L1 positivity at diagnosis correlated with higher Ki-67 proliferation indices and nuclear grade but not with p53 status. While PD-L1 positivity appeared to be associated with higher pathologic complete response rates after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the difference did not reach statistical significance, likely due to limited sample size. Survival outcomes trended worse in PD-L1–positive patients, although statistical significance was not achieved, again due to the small number of events.

These findings corroborate previous reports indicating antigen degradation in long-stored FFPE tissue blocks. Grillo et al. showed substantial loss of immunoreactivity for markers including hormone receptors and Ki-67 in blocks stored for more than five years [

7,

8]. Engel and Moore highlighted how pre-analytical variables—such as fixation duration and storage conditions—critically influence protein epitope preservation [

6]. Our results extend these observations specifically to PD-L1, a marker of escalating therapeutic importance.

Mechanistically, antigen degradation in FFPE specimens is thought to result from oxidative and hydrolytic modifications, cross-linking of amino acid residues, and conformational changes that mask epitopes, all exacerbated by environmental factors like humidity and temperature fluctuation [

11,

12,

13]. Notably, FFPE tissue sections appear more vulnerable to such degradation than intact blocks [

1], underscoring the risks inherent in delayed IHC analysis of older specimens.

From a clinical standpoint, false-negative PD-L1 results due to storage-related degradation could misclassify eligible patients as ineligible for immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab in metastatic TNBC (KEYNOTE-355 criteria: CPS ≥ 10) [

4]. This underscores the urgency to prioritize testing on recent tissue whenever possible.

Beyond tissue blocks, emerging data also document antigen decay in mounted unstained sections. He et al. (2023) studied the effect of storage time and temperature on PD-L1 (SP142) in invasive breast cancer sections and found that positivity dropped from 97.2% at 1 week to ~33% at 24 weeks at room temperature; refrigerated storage (4 °C or –20 °C) delayed but did not prevent this decline [

23]. Additionally, Fernández et al. (2023) compared 22C3 (ECD-binding) versus E1L3N (ICD-binding) antibodies and found archival samples lost signal significantly in 22C3 but less so in E1L3N, implying epitope specificity affects degradation [

24]. These reinforce the perils of delaying both staining and slide processing post-sectioning.

Accelerated instability testing by Haragan et al. (2020) revealed that PD-L1 IHC signal diminishes markedly over time for 22C3, 28-8, and SP142, whereas mass spectrometry detected PD-L1 protein intact, suggesting structural epitope distortion—not protein degradation—is the driver—and that desiccant storage may mitigate loss [

25].

The clinical relevance of PD-L1 extends beyond TNBC. PD-L1 expression correlates with aggressive tumor biology, including higher Ki-67 rates and basal-like features, as we observed [

15,

16,

17]. PD-L1 expression is also associated with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and an inflamed microenvironment—features linked to better prognosis in certain contexts [

18], highlighting the dual prognostic and predictive roles of PD-L1.

Current ASCO/CAP guidelines do not specify an upper storage limit for FFPE blocks in PD-L1 testing [

20,

21], but our data and supporting studies suggest practical recommendations:

Use recent tissue blocks whenever possible for PD-L1 testing.

Document storage time in pathology reports when using archival tissue.

Consider repeat biopsy when only aged tissue is available.

Optimize storage conditions—minimize humidity and temperature variations, expedite staining, and process slides promptly to reduce antigen loss.

Limitations include the single-institution design, small size of long-storage cohorts, absence of precise storage condition data, and exclusive use of 22C3 assay—different PD-L1 clones may behave differently.

Future multicenter studies should validate PD-L1 stability across various assays and storage protocols, and explore advanced antigen retrieval, mass spectrometry, or desalting techniques to rescue signals from degraded specimens. Quality assurance should incorporate storage duration as a pivotal pre-analytical variable in predictive biomarker evaluation.

5. Conclusions

PD-L1 immunoreactivity in TNBC declines significantly after ≥3 years of FFPE storage, risking false-negative results and missed immunotherapy opportunities. Prioritizing recent specimens and stricter pre-analytical protocols will help maintain biomarker integrity in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.Y.; methodology: M.Y.; validation: K.Y., T.Y., S.K., K.N., and M.T.; formal analysis: K.Y.; investigation: K.Y., T.Y., S.K. K.N., and M.T.; resources: K.Y., T.Y., S.K., M.T., M.Y., and K.N.; writing—original draft preparation: K.Y.; writing—review and ed-iting: K.Y.; visualization: K.Y.; project administration: K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declara-tion of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nippon Medical School Tama Nagayama Hospital (F-2024-145, 8 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FFPE |

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded |

| PD-L1 |

Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| ICI |

Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| TNBC |

Triple-negative breast cancer |

| CPS |

Combined Positive Score |

| pCR |

Pathologic complete response |

| NAC |

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| ER |

Estrogen receptor |

| PgR |

Progesterone receptor |

| HER2 |

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| NG |

Nuclear grade |

| RFS |

Recurrence-free survival |

| OS |

Overall survival |

References

- Morgan, E.; O’Neill, C.; Shah, R.R.; Langselius, O.; Su, Y.; Frick, C.; Fink, H.; Bardot, A.; Walsh, P.A.; Woods, R.R.; Gonsalves, L.; Nygård, J.F.; Negoita, S.; Ramirez-Pena, E.; Gelmon, K.; Antone, N.; Mutebi, M.; Siesling, S.; Cardoso, F.; Gralow, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Arnold, N. Metastatic recurrence in women diagnosed with non-metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Research. 2024, 26, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, T.; Efird, J.T.; Prasad, S.; Jindal, C.; Walker, P.R. The survival benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and pCR among patients with advanced stage triple-negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 112712–112719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, R.; Trudeau, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Hanna, W.M.; Kahn, H.K.; Sawka, C.A.; Lickley, L.A.; Rawlinson, E.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 4429–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Nowecki, Z.; Im, S.A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Holgado, E.; Iwata, H.; Masuda, N.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Perez-Garcia, J.M.; André, F.; Cameron, D.; Jakubowski, T.; Wilks, S.; Wongchenko, M.J.; Fountzilas, C.; Lin, W.; Chui, S.Y.; Ku, N.C.; Ibrahim, Y.H.; Schmid, P. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet. 2020, 396, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emens, L.A.; Adams, S.; Barrios, C.H.; Diéras, V.; Iwata, H.; Loi, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Winer, E.P.; Patel, S.; Collyar, D.; Korde, L.A.; Cortes, J. IMpassion130: Atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. NEJM. 2018, 379, 2108–2121. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, K.B.; Moore, H.M. Effects of preanalytical variables on the detection of proteins by immunohistochemistry in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011, 135, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, F.; Bruzzone, M.; Pigozzi, S.; Pastorino, A.; Melotti, R.; Fiocca, R.; Mastracci, L. Immunohistochemistry on old archival paraffin blocks: is there an expiry date? J. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 70, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, F.; Valle, L.; Brisigotti, M.P.; Ferretti, V.; Canepa, P.; Ferro, J.; Mastracci, L.; Fiocca, R. Factors affecting immunoreactivity in long-term storage of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Diagnostic Pathology. 2017, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, R.; Tunnicliff, J.; Mackay, B.; Steele, C. The effects of prolonged formalin fixation on the immunohistochemical demonstration of antigens. Journal of Histotechnology. 1986, 9, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agilent Technologies. PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx TNBC Interpretation Manual. [Online].

- Werner, M.; Chott, A.; Fabiano, A.; Battifora, H. Effect of formalin fixation and processing on immunohistochemistry. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2000, 24, 1016–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Vara, J.A. Technical aspects of immunohistochemistry. Vet. Pathol. 2005, 42, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, J.; Longatto-Filho, A.; Baltazar, F.; Schmitt, F.; Pinheiro, C. Paraffin-embedded tissue preservation: Is it possible to reverse the damage caused by long-term storage? Histopathology. 2014, 64, 467–478. [Google Scholar]

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Philips, A.V.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Qiao, N.; Wu, Y.; Harrington, S.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Akcakanat, A.; Chawla, A.; Curran, M.; Hwu, P.; Albarracin, C.T.; Molldrem, J.J.; Sharma, P.; Litton, J.K.; Sahin, A.A. PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, D.G.; Boyce, B.F. The challenge of breast cancer biomarker testing: ensuring accuracy, precision, and reproducibility in an era of precision medicine. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012, 136, 543–556. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm, D.L.; Han, G.; Taube, J.M.; Yi, E.S.; Bridge, J.A.; Flieder, D.B.; Homer, R.; West, W.W.; Wu, H.; Roden, A.C.; Fujimoto, J.; Rivard, C.J.; Rehman, J.; Madan, A.; Gagneja, H.; Emancipator, K.; Burns, V.; Harigopal, M. A prospective; multi-institutional, pathologist-based assessment of PD-L1 assay reproducibility in non–small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncology. 2017, 3, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalper, K.A.; Velcheti, V.; Carvajal, D.; Wimberly, H.; Brown, J.; Pusztai, L.; Rimm, D.L. In situ tumor PD-L1 mRNA expression is associated with increased TILs and better outcome in breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 2773–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S.; Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Winer, E.P.; Toppmeyer, D.; Rugo, H.S.; DeLaurentiis, M.; Aksoy, S.; Salgado, R.; Eng-Wong, J.; Saintigny, P.; Emens, L.A. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in early triple-negative breast cancer. NEJM. 2020, 382, 810–821. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, S.; Gatti-Mays, M.E.; Kalinsky, K.; Korde, L.A.; Sharon, E.; Amiri-Kordestani, L.; Bear, H.; McArthur, H.L.; Frank, E.; Perlmutter, J.; Prowell, T.M.; Fuldner, R.A.; Singh, H.; Pazdur, R.; Cortes, J.; Schmid, P. Current landscape of immunotherapy in breast cancer: A review. JAMA Oncology. 2019, 5, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbons, P.L.; Bradley, L.A.; Fatheree, L.A.; Alsabeh, R.; Fulton, R.S.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Haas, T.S.; Karabakhtsian, R.G.; Loy, T.S.; O’Malley, M.; Pambuccian, S.E.; Renshaw, A.A.; Saldivar, J.S.; Swanson, P.E.; Weaver, D.L.; Goldblum, J.R.; Hicks, D.G. Principles of analytic validation of immunohistochemical assays: Guideline from the College of American Pathologists Pathology and Laboratory Quality Center. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014, 138, 1432–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torlakovic, E.E.; Riddell, R.; Banerjee, D.; El-Zimaity, H.; Pilavdzic, D.; Dawe, P.; Barnes, P.; Snover, D.; Bhargava, R.; Cherwitz, D.; Hyjek, E.; Kahn, H.J.; Kalloger, S.; Kenney, J.K.; Magliocco, A.M.; Michel, R.P.; Miller, K.; Ofner, P.; Prioleau, P.G.; Swanson, P.E.; Watson, P.H.; Youngson, B.J.; Zhao, H.; Brandwein-Gensler, M. Canadian Association of Pathologists—Association Canadienne des Pathologistes National Standards Committee/Immunohistochemistry: Best practice recommendations for standardization of immunohistochemistry tests. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2010, 18, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiman, T.; Wells, G.A.; Goodwin, P.J.; Verma, S.; Pritchard, K.I.; Trudeau, M.E.; Gelmon, K.A.; Eisenhauer, E.A. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Program: Pre-analytical variables in molecular pathology: The need for new standards. Histopathology. 2009, 54, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Wang, X.; Cai, L.; Jia, Z.; Liu, C.; Sun, X.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Effect of storage time of paraffin sections on the expression of PD-L1 (SP142) in invasive breast cancer. Diagnostic Pathology. 2023, 18, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, A.I.; Gaule, P.; Rimm, D. Tissue Age Affects Antigenicity and Scoring for the 22C3 Immunohistochemistry Companion Diagnostic Test. Modern Pathology. 2023, 36, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haragan, A.; Lieble, D.; Das, D.M.; Soper, M.D.; Morrison, R.D.; Slebos, R.J.C.; Ackermann, B.L.; Fill, J.A.; Schade, A.E.; Gosney, J.R. Accelerated instability testing reveals quantitative mass spectrometry overcomes specimen storage limitations associated with PD-L1 immunohistochemistry. Lab Invest 2020, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).