Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

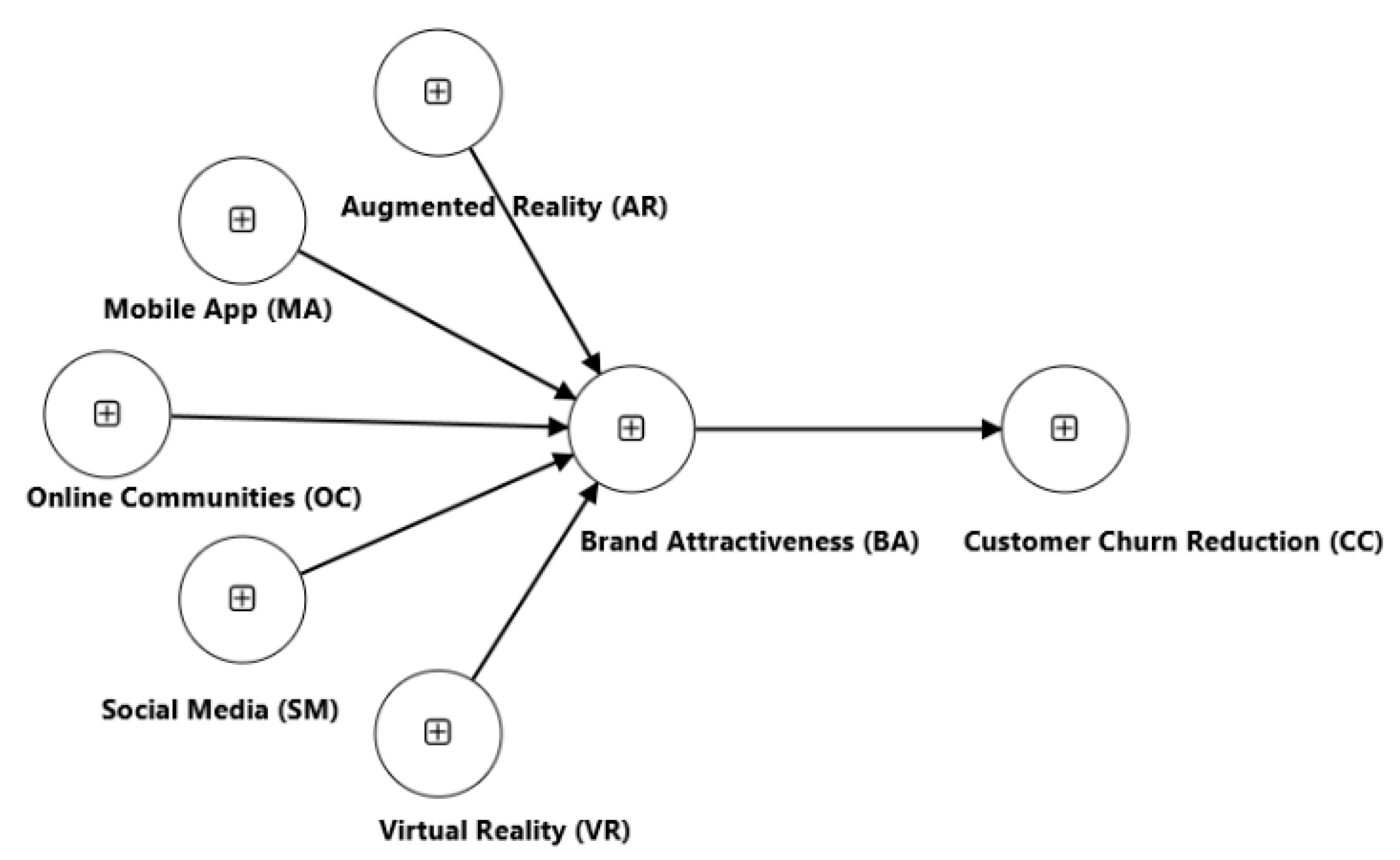

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Augmented Reality (AR) and Brand Attractiveness

2.2. Mobile Applications (MA) and Brand Attractiveness

2.3. Online Communities (OC) and Brand Attractiveness

2.4. Social Media (SM) and Brand Attractiveness

2.5. Virtual Reality (VR) and Brand Attractiveness

2.6. Brand Attractiveness and Customer Churn Reduction

2.7. Mediating Role of Brand Attractiveness

2.8. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Analysis

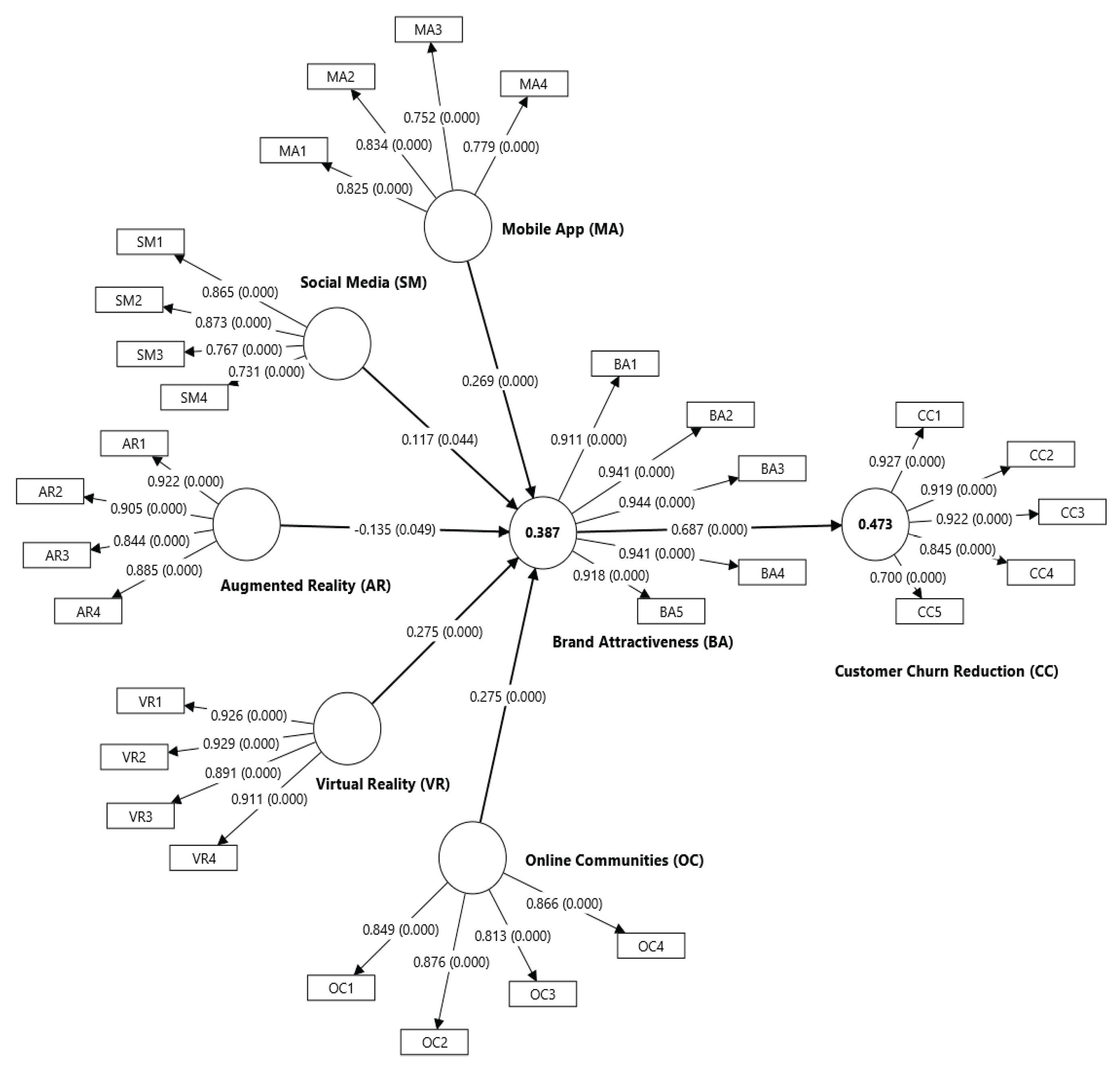

3.2. Measurement Model Assessment

3.3. Structural Model Assessment

3.4. PLS Predictive Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Patents:

Transparency

References

- K. H. Idris Sazali, N. Z. Abu, A. Harith, A. Z. Azmi, M. H. Ishak, F. Anuar, and N. N. S. Nik Azuar, “The influence of green marketing on consumer purchasing behaviour among Millennials group in Klang Valley, Malaysia,” Int. J. Acad. Res. Econ. Manag. Sci., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 120–132, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Abdul, M. A. Ibrahim, and H. A. Manan, “Effects of Digital Customer Experience on Malaysian Millennials E-Loyalty: Examining the Premium Fashion Brands Online Stores,” Sustain. Bus. Soc. Emerg. Econ., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 693–706, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Sarkis, N. Jabbour Al Maalouf, E. Saliba, and J. Azizi, “The impact of augmented reality within the fashion industry on purchase decisions, customer engagement, and brand loyalty,” Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ., pp. 1–10, 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Y. M. Siu, T. J. Zhang, and R. S.-P. Yeung, “The bright and dark sides of online customer engagement on brand love,” J. Consum. Mark., vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 957–970, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. P. Tran, J. E. Zemanek, and M. N. Sakib, “Improving brand love through branded apps: is that possible?,” J. Mark. Anal., pp. 1–21, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Koivisto and J. Hamari, “The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research,” Int. J. Inf. Manage., vol. 45, pp. 191–210, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Xi and J. Hamari, “Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction,” Int. J. Inf. Manage., vol. 46, pp. 210–221, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A.D. Rachmadanty, A. A. Muhtar, and A. Agustina, “Examining the Impact of Gamification and Customer Experience on Customer Loyalty in E-commerce: Mediating Role of Customer Satisfaction,” J. Enterp. Dev., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 180–191, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Punwatkar and M. Verghese, “Investigating the impact of gamification on customer engagement, brand loyalty and purchase intent in marketing,” J. Appl. Res. Technol., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 94–102, 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Desveaud, T. Mandler, and M. Eisend, “A meta-model of customer brand loyalty and its antecedents,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 176, 114589, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Karami, “Brand equity, brand loyalty and the mediating role of customer satisfaction: Evidence from medical cosmetics brands,” Res. J. Bus. Manage., vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 156–171, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Department of Statistics Malaysia, Current Population Estimates, Malaysia, 2021, Putrajaya, Malaysia: DOSM, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.dosm.gov.my/.

- S. Seyfi, T. Vo-Thanh, and M. Zaman, “Hospitality in the age of Gen Z: A critical reflection on evolving customer and workforce expectations,” Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage., vol. 36, no. 13, pp. 118–134, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. R. M. Johan, M. A. M. Syed, and H. M. Adnan, “Digital media and online buying considerations among Generation Z in Malaysia,” J. Intelek, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 164–180, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Memon, J. H. Cheah, T. Ramayah, H. Ting, and F. Chuah, “Mediation analysis: Issues and recommendations,” J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. i–ix, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Memon, R. Salleh, M. Z. Mirza, J. H. Cheah, H. Ting, M. S. Ahmad, and A. Tariq, “Satisfaction matters: The relationships between HRM practices, work engagement and turnover intention,” Int. J. Manpow., vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 21–50, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. U. Jung and V. Shegai, “The impact of digital marketing innovation on firm performance: Mediation by marketing capability and moderation by firm size,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 7, 5711, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A.Mehrabian and J. A. Russell, An Approach to Environmental Psychology. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 1974.

- F. Caboni, V. Basile, H. Kumar, and D. Agarwal, “A holistic framework for consumer usage modes of augmented reality marketing in retailing,” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 80, Art. no. 103924, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Yuan, S. Wang, X. Yu, K. H. Kim, and H. Moon, “The influence of flow experience in the augmented reality context on psychological ownership,” International Journal of Advertising, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 922–944, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. L. Rhee and K. H. Lee, “Enhancing the sneakers shopping experience through virtual fitting using augmented reality,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 11, Art. no. 6336, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Prasad, A. S. Tomar, T. De, and H. Soni, “A conceptual model for building the relationship between augmented reality, experiential marketing and brand equity,” International Journal of Professional Business Review, vol. 7, no. 6, e01030, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Zeng, Y. Xing, and C. H. Jin, “The impact of VR/AR-based consumers’ brand experience on consumer–brand relationships,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 9, Art. no. 7278, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Kim and H. Im, “Can augmented reality impact your self-perceptions? The malleability of the self and brand relationships in augmented reality try-on services,” Journal of Consumer Behaviour, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 1623–1637, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Rauschnabel, V. Hüttl-Maack, A. C. Ahuvia, and K. E. Schein, “Augmented reality marketing and consumer–brand relationships: How closeness drives brand love,” Psychology & Marketing, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 819–837, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Jiang and J. Lyu, “The role of augmented reality app attributes and customer-based brand equity on consumer behavioural responses: An S-O-R framework perspective,” Journal of Product & Brand Management, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 702–716, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. H. W. Ho and H. F. L. Chung, “Customer engagement, customer equity and repurchase intention in mobile apps,” Journal of Business Research, vol. 121, pp. 13–21, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Boateng, J. P. Kosiba, D. R. Adam, K. S. Ofori, and A. F. Okoe, “Examining brand loyalty from an attachment theory perspective,” Marketing Intelligence & Planning, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 479–494, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Boonsiritomachai and P. Sud-On, “Increasing purchase intention and word-of-mouth through hotel brand awareness,” Tourism and Hospitality Management, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 265–289, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Tiwari, A. Chakraborty, and M. Maity, “Technology product coolness and its implication for brand love,” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 58, 102258, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Ahn and J. Kwon, “Examining the relative influence of multidimensional customer service relationships in the food delivery application context,” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 912–928, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Ahn, “Impact of cognitive aspects of food mobile application on customers’ behaviour,” Current Issues in Tourism, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 516–523, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Bowden and A. Mirzaei, “Consumer engagement within retail communication channels: an examination of online brand communities and digital content marketing initiatives,” European Journal of Marketing, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 1411–1439, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Chavadi, M. Sirothiya, S. R. Menon, and V. M. R., “Modelling the Effects of Social Media–based Brand Communities on Brand Trust, Brand Equity and Consumer Response,” Vikalpa, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 114–141, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. D. T. M. Kamalasena and A. B. Sirisena, “The impact of online communities and e word of mouth on purchase intention of Generation Y: The mediating role of brand trust,” Sri Lanka Journal of Marketing, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 92–116, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Bao and D. Wang, “Examining consumer participation on brand microblogs in China: perspectives from elaboration likelihood model, commitment–trust theory and social presence,” Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 10–29, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. H. W. Chuah, E. C. X. Aw, and M. L. Tseng, “The missing link in the promotion of customer engagement: the roles of brand fan page attractiveness and agility,” Internet Research, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 587–612, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Bonus, J. Raghani, J. K. Visitacion, and M. C. Castaño, “Influencer marketing factors affecting brand awareness and brand image of start-up businesses,” Journal of Business and Management Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 189–202, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Huaman-Ramirez and D. Merunka, “Celebrity CEOs’ credibility, image of their brands and consumer materialism,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 638–651, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Grădinaru, D. R. Obadă, I. A. Grădinaru, and D. C. Dabija, “Enhancing sustainable cosmetics brand purchase: a comprehensive approach based on the SOR model and the triple bottom line,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 21, p. 14118, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Khan, F. Alhathal, S. Alam, and S. M. Minhaj, “Importance of social networking sites and determining its impact on brand image and online shopping: an empirical study,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 5129, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Kapuściński, N. Zhang, L. Zeng, and A. Cao, “Effects of crisis response tone and spokesperson's gender on employer attractiveness,” International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 94, p. 102884, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Santiago and T. Serralha, “What more influences the followers? The effect of digital influencer attractiveness, homophily and credibility on followers’ purchase intention,” Issues in Information Systems, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 86–101, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. D. P. Nugroho, M. Rahayu, and R. D. V. Hapsari, “The impacts of social media influencer’s credibility attributes on Gen Z purchase intention with brand image as mediation: Study on consumers of Korea cosmetic product,” International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147-4478), vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 18–32, 2022. [CrossRef]

- É. Robinot, H. Boeck, and L. Trespeuch, “Consumer generated ads versus celebrity generated ads: Which is the best method to promote a brand on social media?” Journal of Promotion Management, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 157–181, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Rizma and E. G. Marsasi, “The effect of trustworthiness to increase brand trust and purchase intention on social media promotion based on theory of persuasion in Generation Z,” Jurnal Manajemen (Edisi Elektronik), vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 61–81, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Ahmed, T. Islam, and A. Ghaffar, “Shaping brand loyalty through social media influencers: The mediating role of follower engagement and social attractiveness,” SAGE Open, vol. 14, no. 2, 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Jin, G. Kim, M. Moore, and others, “Consumer store experience through virtual reality: its effect on emotional states and perceived store attractiveness,” Fashion and Textiles, vol. 8, no. 19, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A.S. Pahlevi, J. Sayono, and Y. A. L. Hermanto, “Design of a virtual tour as a solution for promoting the tourism sector in the pandemic period,” KnE Social Sciences, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 368–374, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. B. Escobar, O. Petit, and C. Velasco, “Virtual terroir and the premium coffee experience,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 12, 586983, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. F. Lin, “Influence of virtual experience immersion, product control, and stimulation on advertising effects,” Journal of Global Information Management (JGIM), vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 1–19, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Yuan, S. Wang, Y. Liu, and J. W. Ma, “Factors influencing parasocial relationship in the virtual reality shopping environment: the moderating role of celebrity endorser dynamism,” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 398–413, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A.Uysal and A. Okumuş, “The effect of consumer-based brand authenticity on customer satisfaction and brand loyalty,” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 1740–1760, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Ke, H. Zhang, N. Yu, and others, “Who will stay with the brand after posting non-5/5 rating of purchase? An empirical study of online consumer repurchase behavior,” Information Systems and e-Business Management, vol. 19, pp. 405–437, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Shahid, Z. Nauman, and I. Ayyaz, “The impact of parasocial interaction on brand relationship quality: The mediating effect of brand loyalty and willingness to share personal information,” International Journal of Management Research and Emerging Sciences, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 51–82, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Pardede and A. Aprianingsih, “The influence of K-pop artist as brand ambassador on affecting purchasing decision and brand loyalty (A study of Scarlett Whitening’s consumers in Indonesia),” International Journal of Management Research and Economics, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 1–15, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Hair, G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, and N. P. Danks, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook, 1st ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2022.

- J. W. Creswell and J. D. Creswell, Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage, 2022.

- M. Saunders, P. Lewis, and A. Thornhill, Research Methods for Business Students, 9th ed. Harlow, England: Pearson Education, 2023.

- M. Bruhn, V. Schoenmueller, and D. B. Schäfer, “Are social media replacing traditional media in terms of brand equity creation?,” Management Research Review, vol. 35, no. 9, pp. 770–790, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Hamari and J. Koivisto, “Why do people use gamification services?,” International Journal of Information Management, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 419–431, 2015. [CrossRef]

- V. M. Sang and M. C. Cuong, “The influence of brand experience on brand loyalty in the electronic commerce sector: the mediating effect of brand association and brand trust,” Cogent Business & Management, vol. 12, no. 1, 2440629, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Dunn, T. Baguley, and V. Brunsden, “From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation,” British Journal of Psychology, vol. 105, no. 3, pp. 399–412, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A.F. Hayes and J. J. Coutts, “Use Omega Rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for Estimating Reliability. But …,” Communication Methods and Measures, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–24, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Nunnally, Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill, 1978.

- M. A. Memon, H. Ting, J. H. Cheah, R. Thurasamy, F. Chuah, and T. H. Cham, "Sample size for survey research: Review and recommendations," Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. i–xx, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Calder, L. W. Phillips, and A. M. Tybout, “Designing research for application,” Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 197–207, 1981. [CrossRef]

- J. Hulland, H. Baumgartner, and K. M. Smith, “Marketing survey research best practices: Evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 92–108, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Ringle, S. Wende, and J.-M. Becker, SmartPLS 4 [Computer software]. Boenningstedt, Germany: SmartPLS GmbH, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.smartpls.com/.

- J. F. Hair, G. T. M. J. F. Hair, G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, and N. P. Danks, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook, 1st ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2022.

- S. Cain, Z. Zhang, and K. Yuan, “Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis for measuring nonnormality: Prevalence, influence and estimation,” Behavior Research Methods, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 1716–1735, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Becker, J. H. Cheah, R. Gholamzade, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt, “PLS-SEM’s most wanted guidance,” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 321–346, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Ramayah, J. Cheah, H. Ting, M. A. Memon, and M. Chuah, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using SmartPLS 3.0: An Updated Guide and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis, 2nd ed. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Pearson, 2018.

- G. Shmueli, M. Sarstedt, J. F. Hair, J. H. Cheah, H. Ting, S. Vaithilingam, and C. M. Ringle, “Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict,” European Journal of Marketing, vol. 53, no. 11, pp. 2322–2347, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Kock and G. S. Lynn, “Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations,” Journal of the Association for Information Systems, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 546–580, 2012. [CrossRef]

- N. Kock, “Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach,” International Journal of e-Collaboration, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1–10, 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. Fornell and D. F. Larcker, “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error,” Journal of Marketing Research, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 39–50, 1981. [CrossRef]

- W. W. Chin, “How to write up and report PLS analyses,” in Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications in Marketing and Related Fields, V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, and H. Wang, Eds. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2010, pp. 655–690. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Preacher and K. Kelley, “Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects,” Psychological Methods, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 93–115, 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Kenny, Mediation [Online]. Available: https://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm, 2025.

| AR | VR | MA | OC | SM | BA | CC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.994 | 3.763 | 1.615 | 1.836 | 1.673 | 2.409 | 2.029 |

| Demographic | Frequencies | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 162 | 52.9 |

| Female | 144 | 47.1 |

| Race | ||

| Malay | 167 | 54.6 |

| Chinese | 115 | 37.6 |

| Indian | 17 | 5.6 |

| Others | 7 | 2.3 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 146 | 47.7 |

| Married | 156 | 51.0 |

| Divorces | 4 | 1.3 |

| Education Level | ||

| Secondary | 7 | 2.3 |

| Diploma | 25 | 8.2 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 157 | 51.3 |

| Master’s degree | 95 | 31.0 |

| Doctoral Degree | 22 | 7.2 |

| Monthly Personal Income | ||

| RM 2,000 or less | 15 | 4.9 |

| RM 2,001 to RM 4,000 | 57 | 18.6 |

| RM 4,001 to RM 6,000 | 89 | 29.1 |

| RM 6,001 to RM 8,000 | 53 | 17.3 |

| RM 8,001 to RM 10,000 | 39 | 12.7 |

| RM 10,001and above | 38 | 12.4 |

| No Income | 15 | 4.9 |

| Items | Outer Loadings | AVE | Composite Reliability |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR1 | 0.922 | 0.791 | 0.938 | |

| AR2 | 0.905 | |||

| AR3 | 0.844 | |||

| AR4 | 0.885 | |||

| MA1 | 0.825 | 0.637 | 0.875 | |

| MA2 | 0.834 | |||

| MA3 | 0.752 | |||

| MA4 | 0.779 | |||

| OC1 | 0.849 | 0.725 | 0.913 | |

| OC2 | 0.876 | |||

| OC3 | 0.813 | |||

| OC4 | 0.866 | |||

| SM1 | 0.865 | 0.659 | 0.885 | |

| SM2 | 0.873 | |||

| SM3 | 0.767 | |||

| SM4 | 0.731 | |||

| VR1 | 0.926 | 0.836 | 0.953 | |

| VR2 | 0.929 | |||

| VR3 | 0.891 | |||

| VR4 | 0.911 | |||

| BA1 | 0.911 | 0.867 | 0.970 | |

| BA2 | 0.941 | |||

| BA3 | 0.944 | |||

| BA4 | 0.941 | |||

| BA5 | 0.918 | |||

| CC1 | 0.927 | 0.751 | 0.937 | |

| CC2 | 0.919 | |||

| CC3 | 0.922 | |||

| CC4 | 0.845 | |||

| CC5 | 0.700 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AR | |||||||

| 2. BA | 0.433 | ||||||

| 3. CC | 0.386 | 0.729 | |||||

| 4. MA | 0.533 | 0.543 | 0.534 | ||||

| 5. OC | 0.595 | 0.553 | 0.415 | 0.466 | |||

| 6. SM | 0.496 | 0.480 | 0.436 | 0.592 | 0.647 | ||

| 7. VR | 0.918 | 0.463 | 0.334 | 0.471 | 0.552 | 0.409 |

| HYPOTHESIS TESTINGHypothesis | Relationship | Std Beta | t-values | p-values | BCI LL | BCI UL | f2 | VIF | Effect Size | Results |

| H1 | AR → BA | -0.135 | 1.659 | 0.049 | -0.267 | -0.000 | 0.008 | 3.893 | No effect | Unsupport |

| H2 | MA → BA | 0.269 | 4.336 | 0.000 | 0.165 | 0.368 | 0.081 | 1.457 | Small | Support |

| H3 | OC → BA | 0.275 | 3.600 | 0.000 | 0.151 | 0.400 | 0.072 | 1.709 | Small | Support |

| H4 | SM → BA | 0.117 | 1.701 | 0.044 | 0.004 | 0.228 | 0.013 | 1.646 | No effect | Support |

| H5 | VR → BA | 0.275 | 3.438 | 0.000 | 0.140 | 0.400 | 0.034 | 3.578 | Small | Support |

| H6 | BA → CC | 0.687 | 17.690 | 0.000 | 0.611 | 0.743 | 0.896 | 1.000 | Strong | Support |

| HYPOTHESIS TESTING MEDIATING EFFECTHypothesis | Relationship | Std Beta | t-values | p-values | BCI LL | BCI UL | v² | Effect Size | Results |

| H7a | AR → BA → CC | -0.093 | 1.654 | 0.049 | -0.183 | -0.000 | 0.010 | Small | Unsupport |

| H7b | MA → BA → CC | 0.185 | 3.976 | 0.000 | 0.109 | 0.261 | 0.034 | Small | Support |

| H7c | OC → BA → CC | 0.189 | 3.668 | 0.000 | 0.104 | 0.272 | 0.036 | Small | Support |

| H7d | SM → BA → CC | 0.080 | 1.654 | 0.049 | 0.003 | 0.161 | 0.006 | No effect | Support |

| H7e | VR → BA → CC | 0.189 | 3.409 | 0.000 | 0.097 | 0.278 | 0.036 | Small | Support |

| PLS PREDICTIVE ASSESSMENT | Q²predict | PLS-SEM_MAE | LM_MAE | PLS-LM_MAE |

| BA1 | 0.287 | 0.768 | 0.750 | 0.018 |

| BA2 | 0.368 | 0.759 | 0.777 | -0.018 |

| BA3 | 0.340 | 0.798 | 0.799 | -0.001 |

| BA4 | 0.287 | 0.793 | 0.803 | -0.010 |

| BA5 | 0.254 | 0.850 | 0.854 | -0.004 |

| CC1 | 0.171 | 0.964 | 0.957 | 0.007 |

| CC2 | 0.208 | 0.968 | 0.990 | -0.022 |

| CC3 | 0.174 | 0.971 | 0.951 | 0.020 |

| CC4 | 0.159 | 0.974 | 0.963 | 0.011 |

| CC5 | 0.124 | 1.032 | 1.035 | -0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).