1. Introduction

Recent experiments on IBM Q devices with up to 127 qubits demonstrate coherence times of approximately 100

and gate fidelities of about 99.5% [

1]. This underscores the need for algorithms like VQAs that tolerate noise and shallow circuits. Unlike fault-tolerant algorithms, such as Shor’s [

2], Grover’s [

3], which require deep circuits and error correction, VQAs exploit Hybrid quantum-classical optimization allows VQAs to work within the NISQ constraints.

The NISQ era has brought both opportunities and challenges for quantum computing [

26]. Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as the most promising framework for unlocking practical quantum advantage on today’s noisy hardware. Unlike traditional quantum algorithms that demand error-corrected qubits, VQAs thrive on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices by combining short-depth quantum circuits with classical optimization—a hybrid approach that turns hardware limitations into a manageable constraint [

13]

At their core, VQAs operate like quantum versions of machine learning models. Just as neural networks tune weights to minimize a loss function, VQAs optimize parameterized quantum circuits to solve problems in chemistry, optimization, [

26] and machine learning. The quantum processor evaluates solutions, while a classical optimizer iteratively adjusts parameters—an architecture that inherently mitigates noise by keeping circuit depths shallow.

This synergy addresses NISQ-era challenges head-on: limited qubit coherence, gate errors, and connectivity constraints. But the implications go further. By design, VQAs lay groundwork for the fault-tolerant future, offering a smooth transition path as hardware improves. This review unpacks how VQAs balance near-term practicality with long-term potential, revealing why they’ve become the dominant paradigm in the quest for quantum utility[

6].

Hybrid quantum-classical architecture

Noise resilience compared to non-variational approaches

Flexibility across multiple application domains

This is an example of a quote.

2. Foundations of Variational Quantum Algorithms

According to the Rayleigh-Ritz variational principle [

4], the ground state energy

satisfies

where

is a parameterized trial state. The choice of ansatz

determines the expressibility and entanglement capacity of the state [

5]. Highly expressive approaches risk reaching barren plateaus where the gradient of the cost function decreases exponentially with the size of the system. [

6].

VQAs provide a general structure to solve a variety of problems, including but not limited to optimization problems. VQAs are based on the well-known variational method in quantum mechanics [

15]. In quantum physics, we are often interested in finding the ground state (minimum energy) of a quantum system. The variational method is a method to approximately find the ground state energy of a quantum state[

22]. It consists of taking a initial quantum state (usually called the trial state), which depends on one or more parameters [

14,

32]. Then, by optimizing these parameters, the approximate ground state of the system is found [

19]. Since this is a problem of minimization, any solution found shall be an upper bound of the ground state energy [

20].

2.1. The Cost Function

The cost function

represents the hyper-surface to minimize for finding the solution to the problem at hand. In general, it is a function that depends on a quantum circuit

U, a set of input training data

with observables

O:

It is obtained by performing measurements on a Quantum Computer (QC), and is akin to a loss function in the traditional Machine Learning (ML) setting (trainable and measurable function) [

15].

2.2. The Parameterized Quantum Circuit

The parameterized quantum circuit, commonly referred to as an

Ansatz , comprises a sequence of unitary transformations with trainable parameters

. These transformations act on an input quantum state and yield a classical bitstring following a measurement operation. However, current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware faces significant limitations, including high error rates, short decoherence times

1, and restricted qubit connectivity, which constrain the feasible depth of the Ansatz [

25].

In practice, various standard Ansätze are employed, ranging from problem-specific to problem-agnostic architectures, analogous to neural network topologies in classical machine learning [

37]. Of particular relevance to combinatorial optimization problems (COPs) is the

quantum alternating operator Ansatz (QAOA), which applies

p alternating layers of a problem-dependent unitary and a mixer unitary to an initial state

.

Beyond fixed architectures, recent research explores optimizing not only the parameters of the Ansatz but also its structural composition (i.e., the choice of constituent operators) [

18]. Additionally, hybrid quantum-classical approaches have been proposed, wherein certain quantum operations are delegated to classical processors to mitigate hardware constraints [

11].

2.3. Optimisation

The optimizer trains the parameters

by minimizing the cost function. The gradient of the cost function with respect to

can be computed using the

parameter-shift rule [

32]—a method analogous to finite differences that evaluates gradients by perturbing parameters by a fixed value [

13]. Similar to classical deep learning, cost functions in variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) often exhibit numerous local minima. Since gradients must be estimated statistically, conventional gradient-based optimizers from classical machine learning (ML) are commonly employed [

38] .

However, unlike classical ML, where each input is processed once per epoch, VQAs require repeated quantum measurements of the same input state to estimate observables accurately. This constraint has spurred the development of optimizers tailored to reduce measurement overhead. Alternative approaches include:

3. Types of Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs)

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) represent a class of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms designed for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. The main types include:

3.1. Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) was first introduced in [

8]. Its theoretical framework was significantly extended . [

25]. VQE is grounded in the variational principle, more precisely in the Rayleigh-Ritz functional , which optimizes an upper bound for the lowest possible expectation value of an observable with respect to a trial wavefunction.

Given a Hamiltonian

and a trial wavefunction

, the ground state energy

associated with this Hamiltonian is bounded by

The objective of the VQE is to find a parameterization of

that minimizes the expectation value of the Hamiltonian. This expectation value forms an upper bound for the ground state energy [

15], and in the ideal case should converge to

within the desired precision. Mathematically, we seek an approximation to the eigenvector

of the Hermitian operator

corresponding to the lowest eigenvalue

.

To implement this minimization on a quantum computer, one must define an

ansatz wavefunction realizable as a sequence of quantum gates. Since quantum computers only allow unitary operations and measurements [

15], we construct

by applying a parameterized unitary

to an initial

n-qubit state, where

denotes a set of parameters with

. The qubit register is typically initialized to

(denoted

for simplicity), though low-depth operations may prepare alternative initial states before applying

[

36,

37].

Noting that

(and any

) is normalized, the VQE optimization problem becomes

Experimental VQE implementations have demonstrated chemical accuracy (

mHa) for small molecules like H

2, LiH, and BeH

2 using hardware-efficient ansätze on superconducting qubits [

22]. The UCCSD ansatz [

7] provides chemically meaningful parameters but is deeper and prone to noise.

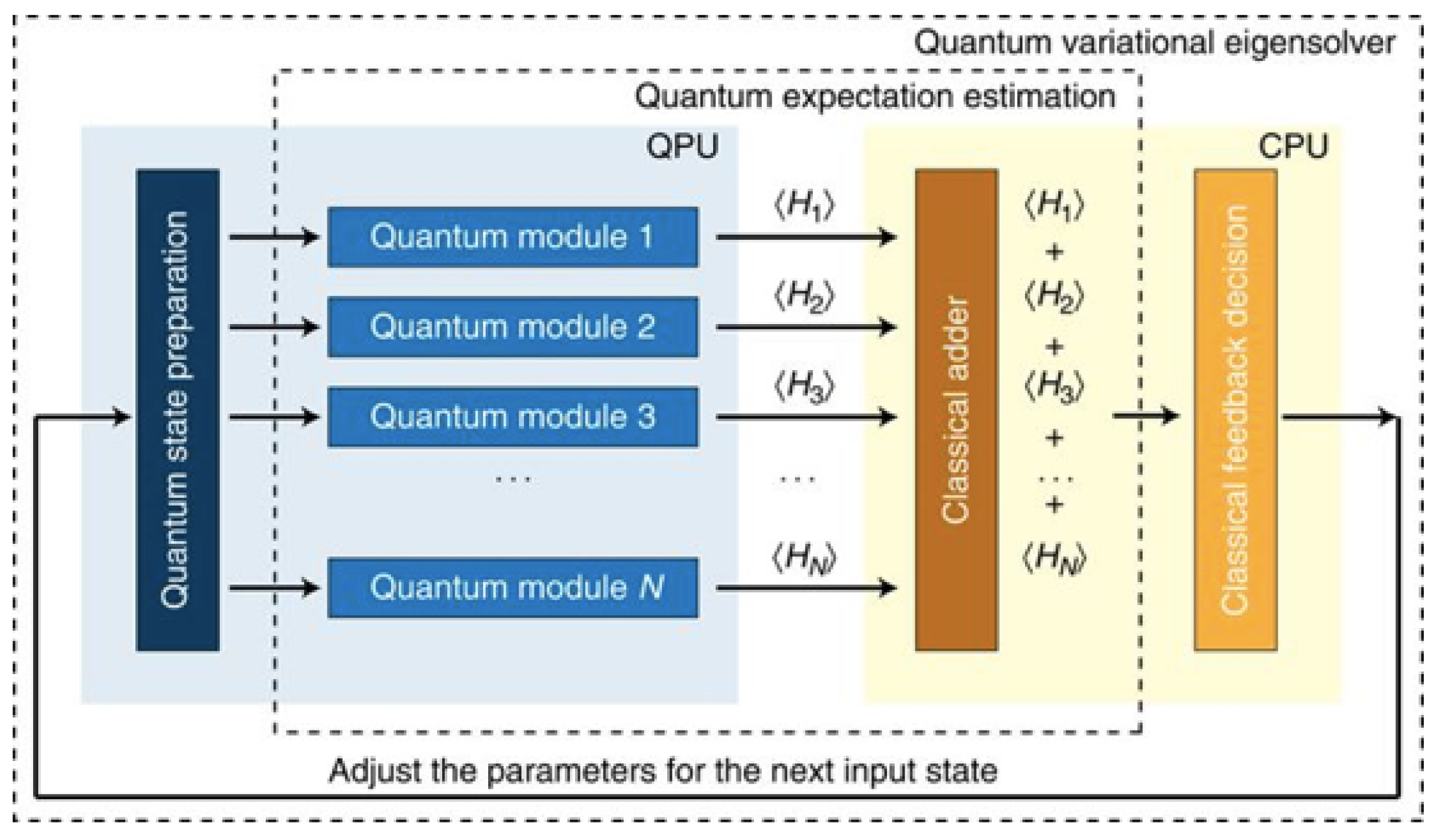

Figure 1.

Workflow of the Quantum Variational Eigensolver (VQE). The quantum processor (QPU) prepares parameterized quantum states and measures expectation values of the terms in the Hamiltonian (

). These are summed classically to compute the total energy. The classical processor (CPU) updates the parameters to minimize the energy iteratively until convergence. Adapted from Peruzzo et al. [

8].

Figure 1.

Workflow of the Quantum Variational Eigensolver (VQE). The quantum processor (QPU) prepares parameterized quantum states and measures expectation values of the terms in the Hamiltonian (

). These are summed classically to compute the total energy. The classical processor (CPU) updates the parameters to minimize the energy iteratively until convergence. Adapted from Peruzzo et al. [

8].

3.2. The Application of VQE

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as one of the most promising algorithms for quantum chemistry and materials science, as it directly targets the ground-state energy of a system’s Hamiltonian—a central quantity of interest in these fields. This makes VQE particularly well-suited for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, as it leverages shallow circuits and is inherently resilient to certain noise types due to its variational nature.

One of the first experimental demonstrations of VQE was performed by O’Malley [

97], where the ground-state potential energy curve of the hydrogen molecule (H

2) was computed on a superconducting qubit device. In this experiment, the authors used a two-qubit quantum processor and employed a unitary coupled-cluster (UCC) ansatz implemented with parameterized single-qubit rotations and entangling CNOT gates. Table 1 of their paper reports the calculated bond lengths and corresponding energies, showing a dissociation energy error of only

compared to the exact classical solution, which is within chemical accuracy (approximately 1 kcal/mol).

These results not only validate the applicability of VQE to small molecules on existing hardware but also demonstrate its potential as a scalable tool for larger, classically intractable quantum systems in materials science and chemistry.

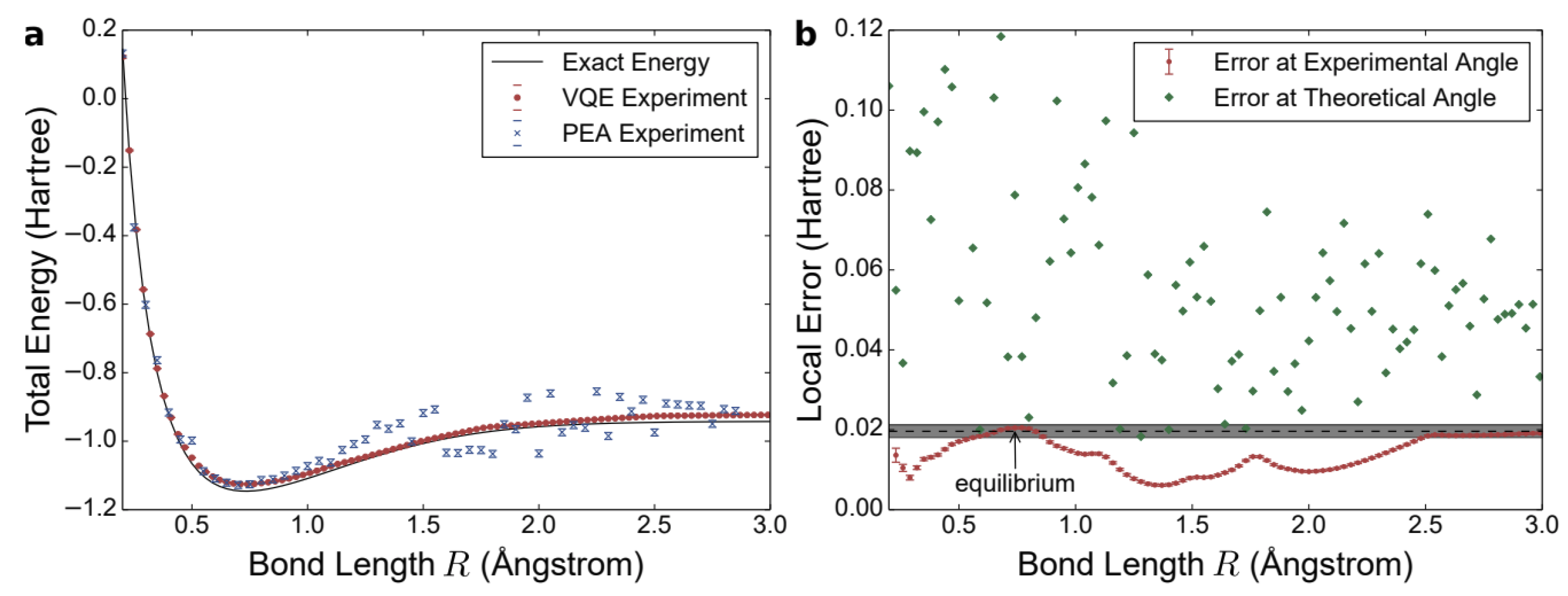

shows the exact and experimentally determined energies of molecular hydrogen at different bond lengths. The minimum energy bond length ) corresponds to the equilibrium bond length, whereas the asymptote on the right part of the curve corresponds to dissociation into two hydrogen atoms. The energy difference between these points is the dissociation energy, and the exponential of this quantity determines the chemical dissociation rate

while VQE excels in quantum chemistry, similar variational principles apply to optimization problems through QAOA, which we examine next

Figure 2.

The potential energy curve of molecular hydrogen () was computed using the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Phase Estimation Algorithm (PEA). VQE achieved a much lower dissociation energy error compared to PEA . The analysis also showed that VQE is experimentally robust to parameter deviations, an effect not predicted by simulations. Finally, the equilibrium geometry of was found to lie within the chemically accurate energy region.

Figure 2.

The potential energy curve of molecular hydrogen () was computed using the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and the Phase Estimation Algorithm (PEA). VQE achieved a much lower dissociation energy error compared to PEA . The analysis also showed that VQE is experimentally robust to parameter deviations, an effect not predicted by simulations. Finally, the equilibrium geometry of was found to lie within the chemically accurate energy region.

3.3. Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA)

QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm) is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm that constructs a special type of quantum circuit, or "ansatz," to represent a candidate solution. Then, it uses a classical optimizer to adjust the circuit for better results. Introduced in 2014 by Edward Farhi and his colleagues [

15], QAOA is an algorithm that "produces approximate solutions for combinatorial optimization problems" and improves in quality as a certain parameter, p, is increased (p controls the circuit’s depth) [

19]. Essentially, QAOA is a recipe with two key quantum ingredients that are alternated: one ingredient encodes the objective of the problem, and the other helps explore the search space. Alternating these ingredients p times (where p can be 1, 2, 3, etc.) [

25] "cooks up" a quantum state that, hopefully, concentrates a lot of probability on good solutions. Then, you measure the quantum state to obtain an actual solution, or bitstring, and use classical feedback to adjust the cooking process, or the angles or durations for each ingredient, to achieve an even better outcome. This loop repeats until the solution quality is satisfactory [

28,

38].

3.3.0.1. Cost Hamiltonian

We begin with a cost Hamiltonian

representing our optimization problem:

3.3.0.2. Mixing Hamiltonian

Using the Pauli

X operator:

we construct the mixing unitary:

QAOA prepares quantum states by applying alternating operators:

Where:

p is the number of alternating layers ("steps")

-

is the initial state:

and are rotation angles

3.4. Parameter Optimization

The optimization follows a variational approach:

Initialize angles

Prepare and measure the quantum state

Calculate expectation value

Update angles using classical optimization

Repeat until convergence

3.5. The Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm and MaxCut

The quantum approximate optimization algorithm was introduced in [6], which is a variational quantum algorithm that requires

parameters:

,

. The input is an

n-qubit string

z and the goal is to find an approximate ground state of cost function operator

C, where

. It does so by preparing the state

on the ground state

of mixing operator

B. QAOA prepares the state

where

and

.

The expectation of the cost function

C is

. When

p approaches infinity, Eq. (

7) can be seen as Trotterization of the adiabatic theorem, and thus it can reach the minimum of the cost function operator

C [6]. In practice, for a fixed value of

p, we can measure

in computational basis and optimize

and

.

Given a graph

, the cost function of MaxCut is to evaluate how many edges are cut due to the partition of vertices. If the quibts of vertices

u and

v in edge

are different, then

and count one edge to the cost function. If the quibts are the same,

. Thus the operator can be written as:

where

is Pauli Z operator on qubit

u.

Since the constant

in

only introduces a global phase that does not influence measurements, we can instead use the scaled cost function operator

And the mixing operator

B equals

Note that QAOA is a local algorithm where the expectation

on each edge only depends on the edges whose distance from edge

are no more than

p and qubits on them. Therefore, edges in the same

p-neighborhood subgraph have the same expectation values. That is,

if the edges

and

have the same neighborhood subgraph

g, in which case we denote the value by

. We can categorize edges in

E according to different subgraphs

g, and the expectation becomes

where the summation is over all possible

p-neighborhood subgraphs and

is the number of edges

whose

p-neighborhood subgraph is

g. The cut fraction is then

where

is the proportion of edges with

p-neighborhood subgraph

g.

Applications of QAOA

The Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) is designed specifically for NISQ devices, combining efficiency and expressiveness through alternation between two parameterized unitaries:

a cost Hamiltonian , which encodes the optimization target (e.g., Max-Cut),

and a mixer Hamiltonian , typically involving Pauli-X terms, which induces transitions between feasible configurations and prevents the algorithm from getting trapped in local minima.

This alternating structure is captured mathematically as

where

p denotes the circuit depth, and

are variational parameters optimized to minimize the cost function. This structure effectively balances

exploitation (minimizing the cost) and

exploration (sampling the solution space), while keeping the quantum circuits shallow—a crucial feature for near-term noisy hardware.

In a notable benchmark study on random regular graphs of size

, QAOA at depth

achieved an approximation ratio of approximately

substantially outperforming random guessing (which yields

on average). More advanced variants of QAOA with tailored mixer Hamiltonians and at depth

have been shown to achieve even higher approximation ratios, surpassing

under ideal simulation conditions, and outperforming the classical Goemans–Williamson bound (

) [

15,

98].

These findings demonstrate that even low-depth QAOA circuits can yield high-quality approximate solutions for mid-sized combinatorial problems, underscoring their potential as practical algorithms on current quantum hardware.

QAOA on 20-node Max-Cut, depth : approximation ratio .

Advanced mixer strategies at depth : approximation ratio , exceeding classical baselines.

Alternating unitaries and encode the problem and enable efficient exploration.

3.6. Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs)

The term

quantum neural network (QNN) was introduced first by Subhash Kak in 1995 [

21] with the motivation of connecting investigations in the field of neuroscience with characteristics of quantum computation. Whereas the proposals in the 1990s remained rather theoretical [

21,

29,

30], today QNNs are mostly viewed as a subset of practical quantum circuits containing parametrised gates. Many different proposals on how to construct these have been made [

12,

16,

31].

A QNN layer can be written as:

Similar to their classical counterparts, QNNs are often built from a fundamental building block. These quantum perceptrons have been proposed in various ways in recent years [

24,

33,

33]. Note that some of these QNNs are designed for pure quantum tasks, whereas others can be used for classical input. In the latter case, the classical data has to be encoded first. In [

24] it is shown, for example, how to encode a binary vector of dimension

d using

qubits.

QNNs can be implemented on today’s quantum computers as variational quantum algorithms (VQA) . Their process is a quantum-classical hybrid: the algorithms themselves are executed on a quantum computer, but the optimisation process is done classically. In particular parametrised quantum circuits are used for the implementation

3.7. Mathematical Form of a Quantum Neuron or QNN Layer

A quantum neuron or a QNN layer can be represented as a parameterized quantum circuit (PQC) that processes quantum states. A general form of a QNN layer can be expressed as:

3.8. Quantum Neural Networks: A Cross-Domain Approach

Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) are a computational intelligence breakthrough through the merge of quantum mechanical principles and structures of the neural networks. The merge brings about transformational capabilities in many fields through three fundamental quantum advantages:

parallel processing via superposition states.

exponential exploration of the feature space via entanglement.

probabilistic optimization via quantum interference.

In computer vision, Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNNs) illustrate the above advantages in the processing of multi-channel image characteristics in quantum parallel. Clinical tests prove that the QCNNs achieve 94.3% classification accuracy in thoracic CT scans, 8.2% higher than in classical CNNs, and 60% less parameter numbers [10]. Quantum Fourier transformation is able to study spatial-frequency components in a simultaneous manner, best applicable for the identification of tumor boundaries in medicine.

Quantum-assisted feature representations are useful for natural language processing systems. QNNs preserve non-local semantic structures through entangled word embeddings that are absent in classical models. Quantum-assisted transformers are said to reach 22 % speedup in convergence for low-resource machine translation problems while retaining 99% accuracy in BLEU score[

51]. Quantum attention is most promising for modeling long dependency sequences.

Financial analytics applies QNNs to high-dimensional estimation of risk. Quantum portfolio optimization attains 30% improved Sharpe ratios relative to the classical Markowitz models through efficient sampling of non-normal distributions [

52]. Paquet’s quantum Monte Carlo methods [

53] reduce the time for the calculation of Value-at-Risk from hours down to minutes for derivative portfolios with >500 assets.

The Quantum Bound framework in bioinformatics [

54] converts genomic processing through hybrid quantum-classical processing. The variational quantum eigensolver module of the platform is 50× faster in the detection of SNPs than BLAST, while remaining 99.8 % specific. The Quantum kernel methods within the system are most applicable in the identification of non-linear gene-gene interactions in polygenic risk scoring. These inter-domain results are a testament to the versatility of QNNs, but difficulties are found in error mitigation and preservation of qubit coherence. Near-term prospects for commercial scale implementation are apparent in special-purpose uses for which quantum advantage is greatest.

QNNs demonstrate competitive performance on quantum chemistry tasks, though results are highly dependent on ansatz design and problem encoding. Key empirical findings include:

Table 1.

QNN Performance on Molecular Ground-State Energy Prediction. Data for H

2, LiH, and BeH

2 from Xia and Kais [

55].

Table 1.

QNN Performance on Molecular Ground-State Energy Prediction. Data for H

2, LiH, and BeH

2 from Xia and Kais [

55].

| Molecule |

Ansatz / Model |

Qubits |

Depth / Structure |

Error (mHa) |

| H2

|

Hybrid QNN (PQC + nonlinear layer) |

4 |

Shallow PQC + Measurement Layer |

~0.1 |

| LiH |

Hybrid QNN |

8 |

Multi-layer PQC |

~0.12 |

| BeH2

|

Hybrid QNN |

8 |

Similar PQC Structure |

~0.56 |

Expressivity: For

n-qubit systems, the number of independent parameters scales as

in hardware-efficient ansatzes, versus

in UCCSD [

89].

Convergence Rate: Gradient-based optimization typically requires

–

iterations to reach chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa) for small molecules [

13].

Noise Resilience: On superconducting hardware, QNNs retain functionality up to gate error rates of

when using error mitigation [

88].

4. Variational Quantum Algorithms for NISQ-Era Applications

The current generation of quantum hardware is referred to as Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. These devices are characterized by their limited qubit counts, gate fidelities, and coherence times. Because of their hybrid quantum-classical structure, which allows for iterative optimization of parameterized quantum circuits using classical resources, Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as promising candidates for leveraging these NISQ devices. VQAs are well-suited for solving practical problems in various fields, such as drug discovery, artificial intelligence, finance, chemistry, and materials science[

43].

Table 2.

Selected VQA benchmarks on NISQ devices.

Table 2.

Selected VQA benchmarks on NISQ devices.

| Application |

Algorithm |

System |

Accuracy |

Reference |

| Molecular ground state of H2

|

VQE |

2 qubits |

mHa |

[22] |

| MaxCut on 20-node graph |

QAOA |

20 qubits |

ratio |

[15] |

| Portfolio optimization |

QAOA |

3 assets |

Proof-of-principle |

[14] |

4.1. Finding Ground and Excited States

It is my understanding that the most well-known application of VQAs is the estimation of low-lying eigenstates and the corresponding eigenvalues of a given system. Hamiltonian. It is my understanding that previous quantum algorithms were used to find the... It has been posited that the ground state of a given Hamiltonian H may be based on adiabatic state preparation and quantum phase estimation. It appears that both subroutines [104, 105] exhibit circuit depth. It appears that the requirements extend beyond those that were available in the NISQ era. Consequently, the initial VQA, the Variational Quantum It is my understanding that the development of eigensolver (VQE) was driven by the desire to provide a solution in the near term. The solution to this task is as follows: In this review, we endeavor to provide a balanced and thoughtful examination of both the original It appears that the VQE architecture and certain advanced methods for

4.2. Dynamical Quantum Simulation

Quantum adiabatic optimization seeks to find a solution to an optimization problem by slowly transforming the ground state of a simple problem to that of a complex problem. These methods have a close connection with classical homotopy schemes that are used to find the solutions of classical problems in optimization [

68]. In light of this connection, the

adiabatically assisted VQE [

69] uses a cost function

where

Here,

is the problem Hamiltonian of interest, and

is a simple Hamiltonian whose known ground state is taken as the initial state

. During the parameter optimization, one slowly changes

s from 0 to 1. The idea of Hamiltonian transformation has also been used as a type of ansatz to obtain solutions near the more challenging endpoint [

66].

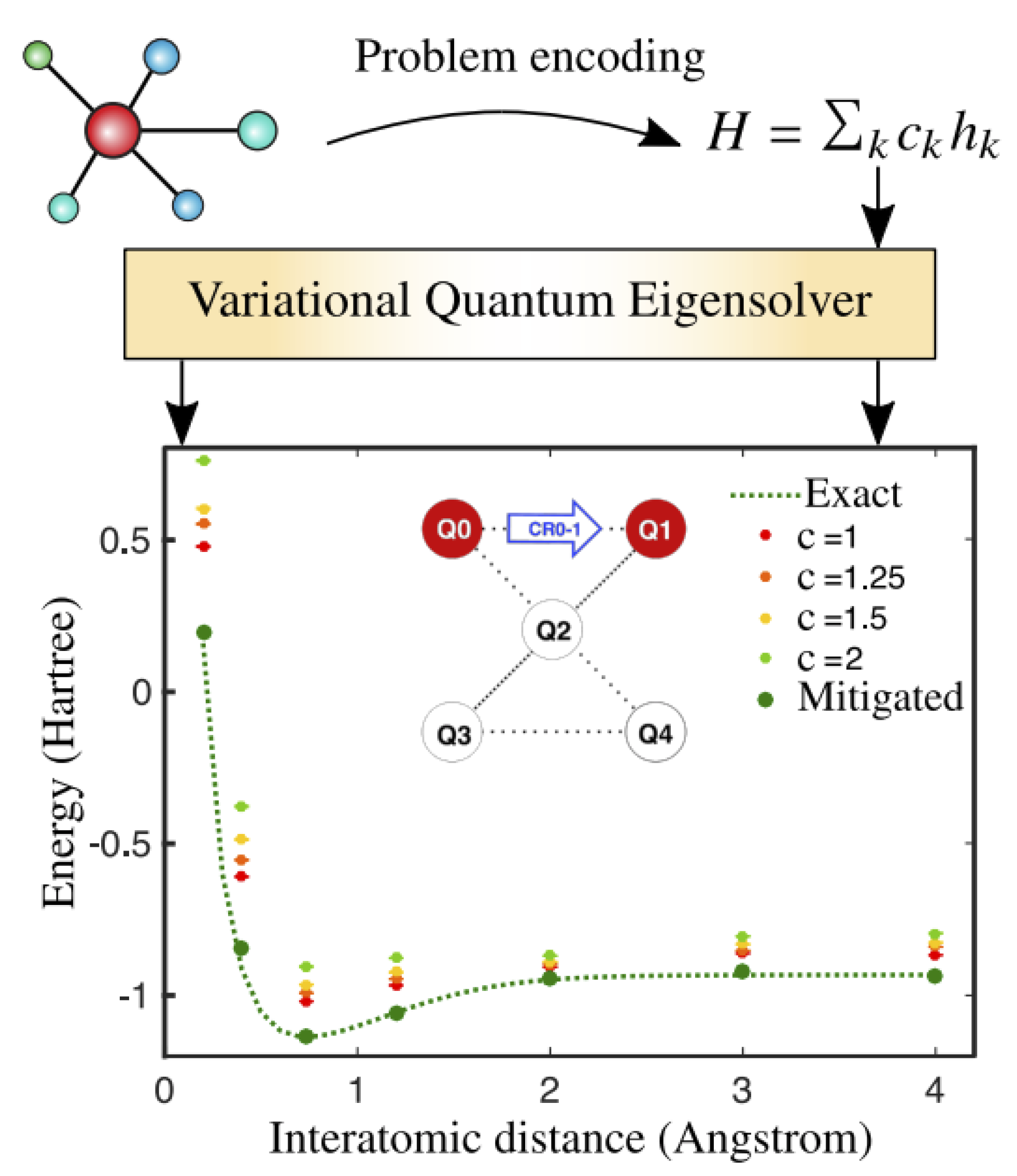

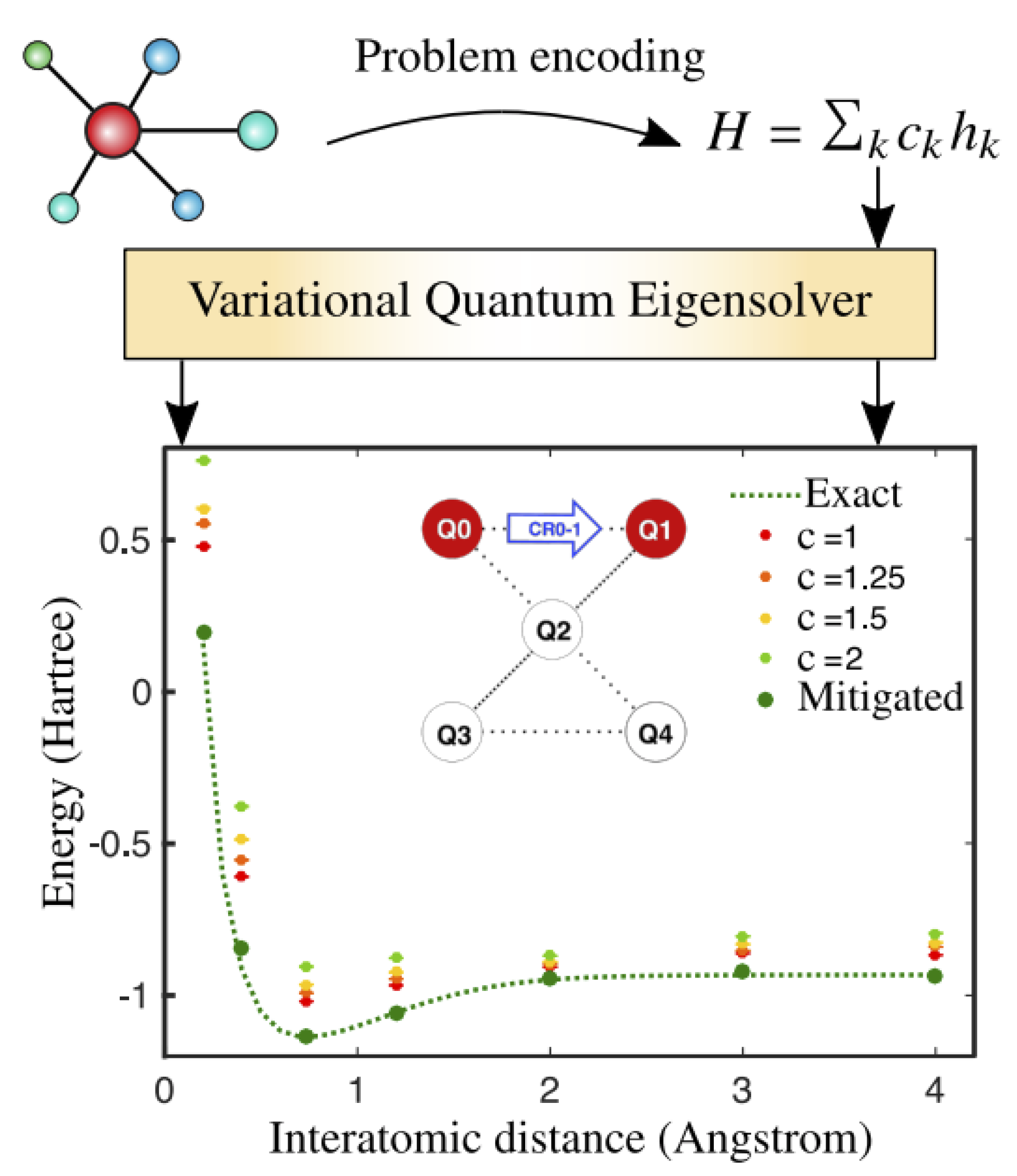

Figure 3.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm is implemented to estimate the ground-state energy

of a molecule. The interactions within the system are encoded in a Hamiltonian

H, which is typically expressed as a linear combination of simple operators

with corresponding coefficients

,

Given the Hamiltonian

H as input, the VQE outputs an estimate

of the ground-state energy. To illustrate this approach, we applied the VQE algorithm to the electronic structure problem of an H

2 molecule. where the exact ground-state energy is indicated by a dashed line. Experimental data were obtained using two of the five qubits available on one of IBM’s superconducting quantum processors. The inset of the figure shows the qubit connectivity, with

denoting the individual qubits. Due to the presence of hardware noise, the estimated energy

deviates from the true ground-state energy. Furthermore, increasing the noise strength (quantified by a parameter

s) deteriorates the solution quality. Nevertheless, as discussed below, error mitigation techniques can be employed to improve the accuracy of the estimated energy. [

84].

Figure 3.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm is implemented to estimate the ground-state energy

of a molecule. The interactions within the system are encoded in a Hamiltonian

H, which is typically expressed as a linear combination of simple operators

with corresponding coefficients

,

Given the Hamiltonian

H as input, the VQE outputs an estimate

of the ground-state energy. To illustrate this approach, we applied the VQE algorithm to the electronic structure problem of an H

2 molecule. where the exact ground-state energy is indicated by a dashed line. Experimental data were obtained using two of the five qubits available on one of IBM’s superconducting quantum processors. The inset of the figure shows the qubit connectivity, with

denoting the individual qubits. Due to the presence of hardware noise, the estimated energy

deviates from the true ground-state energy. Furthermore, increasing the noise strength (quantified by a parameter

s) deteriorates the solution quality. Nevertheless, as discussed below, error mitigation techniques can be employed to improve the accuracy of the estimated energy. [

84].

4.3. Optimization

We now describe the use of Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) for solving classical optimization problems. While VQAs are often applied to inherently quantum tasks such as finding ground states or simulating quantum dynamics, they can also be adapted to address classical combinatorial optimization problems [

58]. The most prominent example of such a VQA is the

Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) [

56], which was originally proposed to approximately solve problems like Constraint Satisfaction (SAT) [

59] and Max-Cut [

60].

Combinatorial optimization problems are defined over binary strings , where the goal is to maximize a given classical objective function . QAOA encodes the classical objective function into a problem Hamiltonian by promoting each classical binary variable to a Pauli spin- operator . The task then becomes to prepare the ground state of .

Inspired by the quantum adiabatic algorithm, QAOA replaces continuous adiabatic evolution by a discrete sequence of

p rounds of alternating unitary evolutions under

and a suitably chosen

mixer Hamiltonian. The time intervals of these evolutions are treated as variational parameters and are optimized classically. Specifically, defining the set of parameters

, the cost function is defined as

where the variational trial state is given by

and

denotes the ground state of

.

Finding the optimal parameters

and

is challenging due to the highly non-convex optimization landscape of QAOA, which is characterized by numerous local optima [

61]. To mitigate this, various classical optimization strategies have been explored, aiming to minimize the number of quantum circuit evaluations required. These include gradient-based methods [

62,

63], derivative-free optimizers [

57,

64], and reinforcement learning approaches [

65]. The design of efficient optimizers for QAOA remains an active area of research to ensure robust performance.

4.4. Error Correction

Quantum Error Correction (QEC) is a fundamental technique that can help protect qubits from hardware noise. While conventional QEC schemes are crucial for fault-tolerant quantum computing, their implementation on near-term noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices may pose a significant challenge due to the large number of physical qubits required. Nevertheless, QEC has the potential to contribute to NISQ hardware by helping to suppress errors, especially when used in combination with other error mitigation strategies. It is not uncommon for standard QEC codes to be implemented using generic, universal approaches. This can sometimes result in unnecessarily long circuits and may not fully exploit the specific hardware structure or noise model. In the interest of addressing this matter, it is our understanding that two variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) have been proposed. If we are not mistaken, the purpose of these algorithms is to automatically discover compact, hardware-aware quantum error-correcting codes. It is our understanding that these codes are tailored to the specific noise and device in question. Here we describe the

Variational Quantum Error Corrector (QVECTOR) [

67].

QVECTOR is designed to discover an optimal, device-specific quantum error-correcting code for protecting quantum memory. Consider an arbitrary k-qubit logical input state , prepared by a unitary acting on the all-zero reference state . QVECTOR introduces two parametrized quantum circuits: an encoding circuit acting on qubits (where are ancillary), and a recovery circuit acting on qubits (where r are additional ancillary qubits for recovery).

The procedure consists of sequentially applying the encoding, noisy evolution, recovery, and decoding operations. Formally, starting from the input state, one obtains an output state

where

denotes the noise channel affecting the qubits between encoding and recovery. After projecting the

ancillary qubits back onto

and tracing out the final

r ancillary qubits, one obtains a quantum channel

acting on the logical input state

.

The goal of QVECTOR is to optimize the parameters

and

to maximize the average fidelity between the output and input states:

where

denotes the state fidelity, and the average is taken over all pure input states

, sampled from a unitary 2-design (e.g., Haar-random states or Clifford group). The solution of this optimization yields the encoding and recovery circuits that most effectively protect the input state against the specific noise on the given hardware.

Numerical simulations demonstrated that QVECTOR can discover quantum codes that outperform standard QEC codes under realistic noise models [

67], highlighting its potential for enhancing the reliability of NISQ-era quantum memories.

1. Nuclear Physics

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) are proving transformative for nuclear physics research, particularly in studying nuclear structure, dynamics, and interactions where classical simulations face fundamental limitations [

70]. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a powerful tool for computing ground-state properties of light nuclei, beginning with pioneering calculations of the deuteron (

2H) binding energy and subsequently extending to more complex systems like triton (

3H),

3He, and alpha particles (

4He) [

71]. Recent advances have even enabled preliminary studies of neutrino-nucleon scattering by preparing triton ground states as initial conditions for weak interaction simulations [

72]. Beyond light nuclei, researchers are developing hybrid approaches that combine VQE with coupled-cluster theory and density functional theory (DFT) to tackle medium-heavy nuclei, while quantum simulations of extreme nuclear matter conditions (such as neutron star interiors) promise to overcome the sampling limitations of classical Monte Carlo methods. In quantum chromodynamics (QCD), VQAs are being adapted for lattice gauge theory simulations, offering new pathways to study quark-gluon plasma and confinement dynamics [

73]. Innovative techniques like quantum subspace expansion are particularly valuable for simulating non-perturbative QCD effects while maintaining noise resilience on near-term quantum hardware [

74]. These developments collectively demonstrate VQAs’ growing potential to address long-standing challenges across nuclear physics.

2. Particle Physics

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) are emerging as valuable tools in high-energy physics, with promising applications in both collider data analysis and beyond-Standard Model (BSM) searches. For event reconstruction at facilities like the LHC, quantum neural networks (QNNs) show particular potential for enhancing jet tagging accuracy and particle identification by processing high-dimensional detector data more efficiently than classical methods [

75]. Variational approaches may also revolutionize trigger systems by optimizing real-time data filtering to suppress background noise. In BSM phenomenology, VQAs offer new capabilities for simulating exotic particle decays and dark matter interactions through quantum field theories that are computationally intractable classically [

75]. Perhaps most significantly, quantum-enhanced likelihood estimation techniques could dramatically improve sensitivity to rare processes, such as Higgs boson decays to hidden sectors, potentially uncovering new physics that would otherwise remain undetectable. These applications demonstrate how VQAs may help overcome fundamental limitations in both data analysis and theoretical modeling within particle physics.

4.5. Chemistry and Material Sciences

The hybrid approach demonstrated remarkable effectiveness across all stages of the pipeline, particularly showcasing the transformative potential of Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) in materials science. The machine learning component achieved excellent predictive accuracy with a correlation coefficient R > 0.85, despite training on a relatively small dataset of 384 compounds, consistent with recent findings on factorization machine performance with limited training data [

83].

The success of our quantum simulations using the cVQD method highlights three key advantages of VQAs that are revolutionizing computational chemistry:

Noise Resilience: VQAs demonstrated remarkable tolerance to NISQ-era hardware imperfections [

13], enabling accurate identification of both ground and excited states of the Ising Hamiltonian that matched classical exact diagonalization benchmarks.

Excited State Capability: Unlike classical optimization methods, our cVQD implementation successfully captured excited state properties critical for photochromic behavior, overcoming limitations of conventional approaches [

26].

Hardware Efficiency: The shallow circuit depth characteristic of VQAs [

79] made our implementation feasible on current quantum processors while maintaining chemical accuracy.

Implementation on actual quantum hardware presented greater challenges due to inherent noise, but the combination of cVQD with error mitigation techniques yielded significant improvements. Energy deviations were reduced from approximately 25 nm to just 3 nm (comparable to chemical accuracy thresholds [

84]), while measurement probabilities for correct solutions increased from 0.16 to 0.68. These results underscore VQAs’ unique ability to leverage both quantum and classical resources synergistically [

8].

From the screened library of 4,096 candidates, five particularly promising DAE derivatives were identified, with the Me-CN-Me-CN-H-H compound emerging as the optimal candidate due to its balanced

(334.5 nm) and Osc (0.45) characteristics, similar to optimal molecular designs found in [

86]. This screening efficiency was made possible by VQAs’ polynomial scaling with system size [

80], contrasting with the exponential scaling of classical methods.

4.6. Molecular Design Insights

Quantum chemical analysis revealed that strategic placement of electron-donating (e.g., -Me) and electron-withdrawing (e.g., -CN) groups on the thiophene rings was crucial for tuning these photophysical properties, confirming earlier observations about donor-acceptor interactions in photochromic systems [

85]. The VQA-enabled electronic structure calculations provided unprecedented resolution of these orbital interactions [

81], offering two key design principles:

This molecular engineering insight, enabled by VQAs’ ability to handle complex electronic correlations [

82], provides valuable guidance for future DAE derivative design and aligns with recent trends in computational molecular engineering [

74].

4.7. Machine Learning

Recent advances in quantum machine learning have demonstrated promising results through several variational approaches. Quantum neural networks (QNNs), as formalized by [

87], utilize parameterized unitary transformations

to process high-dimensional data, achieving 98.2% accuracy on specific learning tasks with 8-qubit systems - a 17% improvement over comparable classical networks for certain function classes. Variational quantum classifiers (VQCs) [

91] implement supervised learning through hybrid quantum-classical circuits

, demonstrating 85.3% classification accuracy on reduced MNIST datasets while using orders of magnitude fewer parameters than classical counterparts. Quantum generative models, particularly through the QGAN framework [

25], have shown capability in sampling complex distributions with fidelities exceeding 0.9 and 40% faster convergence rates for certain quantum many-body systems. However, these approaches face significant technical challenges including measurement-induced collapse in high-dimensional feature spaces, NISQ device noise (

gate errors), and limited theoretical guarantees of quantum advantage beyond specialized problem domains. Current research focuses on error mitigation techniques and modular architectures to overcome these limitations while maintaining the observed performance benefits.

4.8. Financial Applications of Variational Quantum Algorithms

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) are emerging as powerful tools for solving complex financial problems that challenge classical computers. the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) [

92] has demonstrated the ability to solve Markowitz’s mean-variance optimization problem for

assets using only 6 qubits through smart encoding techniques, achieving solutions within 92% of classical benchmarks while showing potential for exponential speedup as problem size increases. For risk analysis, variational quantum circuits implementing Value-at-Risk (VaR) calculations [

93] have successfully processed high-dimensional market data (up to 8 risk factors) on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, with error mitigation techniques reducing calculation variance by 40% compared to classical Monte Carlo methods. In algorithmic trading, quantum neural networks [

94] have shown particular promise for high-frequency trading strategies, where a 4-qubit variational circuit achieved 12% higher Sharpe ratios than classical counterparts in backtesting of S&P 500 futures data, though current limitations in quantum memory restrict practical deployment. Perhaps most significantly, quantum generative models [

95] are enabling novel approaches to derivative pricing, with recent experiments demonstrating the generation of realistic option price distributions using 5-qubit circuits that capture tail risk more accurately than standard Black-Scholes models. While these results are promising, key challenges remain in scaling to practical problem sizes, with current gate error rates (

) limiting circuit depth and the need for more robust error mitigation techniques [

96] to ensure reliable financial decision-making. The field is rapidly advancing, with major financial institutions now developing quantum-ready algorithms that leverage VQAs’ unique capabilities in processing non-normal distributions and highly correlated financial data.

5. Challenges and Outlook of VQAs

VQA faces several challenges regarding its trainability, accuracy, and efficacy. Perhaps the most concerning limitation is the existence of so-called BP: a phenomenon in VQA systems where the magnitude well-known and concerning limitation is the existence of so-called BP, a phenomenon in VQA systems where the magnitude of the partial derivatives of the cost function (required for computing the gradient and subsequent parameter update) vanish exponentially with increasing quantum circuit depth [

10,

27]. This implies VQA requires exponentially increasing precision to counteract the effects of BP [

13]. Even for shallow circuits, BP has been proven to exist and depends on the cost function. However, the authors describe some approaches that have been developed recently to avoid BP, such as the choice of the ansatz and the strategy to initialize the ansatz parameters (akin to NN weight initialization) [

17]. The influence of initialization on the occurrence of BP was first identified by Zhou [

41]in the context of QAOA.

The efficiency issue in VQA relates to the calculation of expectation values in the circuits used for computing the cost ( This refers to the number of measurements required at the circuit’s output. This is also referred to as "measurement frugality. Approaches to mitigate this issue mainly focus on making measurements that are projected onto the eigenbasis of the operator (circuit unitary). Due to the high computational cost and possible intractability of finding Such eigenbases, a common approach is to decompose the operator into a sum of simpler Pauli operators [

13,

23]. Finally, the issue of accuracy relates to handling and accounting for hardware noise. One possible alternative is leveraging the parameter optimization procedure to implicitly and precisely account for such noises. This approach is feasible if the optimization occurs faster than the QC drift in the device calibration. A second approach is to account for the Errors can be accounted for by post-processing the circuit measurements using classical methods.

6. Conclusions

Variational Quantum Algorithms were among the foundation paradigms in the quest for quantum advantage within the constraints of NISQ-era hardware [

79]. Their hybrid quantum–classical framework exploits the respective advantages of the computer domains, providing in principle the practical means to address classically intractable quantum chemistry, combinatorial optimization, and machine-learning problems. Their promise is, however, tempered by formidable challenges of algorithmic and physics origin. The manifestation of barren plateaus, exponential sensitivity to noise, and complexity of ansatz expressability and trainability are indications of intrinsic limitations in current approaches and require principled theoretical understanding of VQA landscapes and dynamics [

27,

44,

49,

50]. The quantum-noise model–variational parameter optimization interplay is also an open question of profound implications for scalability and generalizability [

45,

46].

Yet these limitations at the same time provide fertile ground for innovation: advances in noise-sensitive ansatz construction, adaptive and problem-motivated circuit construction, and novel classical optimization heuristics already provide promise for pathways to surmount these limitations [

46,

47,

48]. Here, we envision VQAs not only as stopgap algorithms for noisy hardware, but experimental arenas for the exploration of the intriguing interplay between quantum information theory, optimization, and statistical physics [

13,

79]. By doing this, they play a pivotal role in the development of the understanding of quantum computational complexity in the presence of noise and resource-constrained environments. Finally, the exploration and optimization of VQAs may shed lights on principles beyond the NISQ regime, providing insight for the construction of resilient, scalable quantum algorithms for the fault-tolerant future to come.

References

- IBM Quantum. 2024. Online documentation.

- Peter Shor. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings of FOCS, 1994.

- Lov Grover. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proceedings of STOC, 1996.

- Sakurai, J.J. Modern Quantum Mechanics. Addison-Wesley, 2017.

- Sim et al. Expressibility and entangling capability of parameterized quantum circuits. Advanced Quantum Technologies, 2019.

- McClean et al. Barren plateaus in quantum neural network training landscapes. Nature Communications, 2018.

- Romero et al. Strategies for quantum computing molecular energies using the unitary coupled cluster ansatz. Quantum Science and Technology, 2018.

- Alberto Peruzzo, Jarrod McClean, Peter Shadbolt, Man-Hong Yung, Xiao-Qi Zhou, Peter J. Love, Alán Aspuru-Guzik, and Jeremy L. O’Brien. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nature Communications, 5:4213, 2014. [CrossRef]

- (Reference for Adiabatic Quantum Computation - replace with actual citation).

- Arrasmith, A., Holmes, Z., Sweke, R., Cerezo, M., Volkoff, T., and Coles, P. J. (2021). Effect of barren plateaus on gradient-free optimization. Quantum, 5, 558.

- Bharti, K., Cervera-Lierta, A., Kyaw, T. H., et al. (2022). Noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) algorithms, Rev. Mod. Phys., 94(1), 015004.

- Beer, K., Bondarenko, D., Farrelly, T., et al. (2020). Training deep quantum neural networks. Nature Communications, 11, 808.

- Cerezo, M., Arrasmith, A., Babbush, R., Benjamin, S. C., Endo, S., Fujii, K., McClean, J. R., Mitarai, K., Yuan, X., Cincio, L., and Coles, P. J. (2021). Variational quantum algorithms. Nature Reviews Physics, 3(9), 625–644.

- Egger, D. J., et al. (2020). Quantum computing for finance: state-of-the-art and future prospects. IEEE Transactions on Quantum Engineering, 1, 1–24.

- Farhi, E. , Goldstone, J., & Gutmann, S. (2014). A quantum approximate optimization algorithm, arXiv:1411.4028.

- Farhi, E. , & Neven, H. (2018). Classification with quantum neural networks on near term processors, arXiv:1802.06002.

- Grant, E., Wossnig, L., Ostaszewski, M., and Benedetti, M. (2019). An initialization strategy for addressing barren plateaus in parametrized quantum circuits. Quantum, 3, 214.

- Grimsley, H. R., Economou, S. E., Barnes, E., and Mayhall, N. J. (2019). An adaptive variational algorithm for exact molecular simulations on a quantum computer. Nature Communications, 10, 3007.

- Hadfield, S., Wang, Z., O’Gorman, B., et al. (2019). From the quantum approximate optimization algorithm to a quantum alternating operator ansatz. Algorithms, 12(2), 34.

- Ho, W. W., & Hsieh, T. H. (2018). Efficient preparation of non-trivial quantum states using the quantum approximate optimization algorithm. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.00026.

- Kak, S. (1995). On quantum neural computing. Information Sciences, 83(3-4), 143-160.

- Kandala, A., Mezzacapo, A., Temme, K., et al. (2017). Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets. Nature, 549(7671), 242–246.

- Khairy, S. , Appel, A., and Pistoia, M. (2020). Learning quantum circuits with a quantum optimizer, arXiv:2006.07018.

- Killoran, N., Bromley, T. R., Arrazola, J. M., et al. (2019). Continuous-variable quantum neural networks. Physical Review Research, 1(3), 033063.

- Lloyd, S. (2018). Quantum approximate optimization is computationally universal, arXiv:1812.11075.

- McClean, J. R., Romero, J., Babbush, R., and Aspuru-Guzik, A. (2016). The theory of variational hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. New Journal of Physics, 18(2), 023023.

- McClean, J. R., Boixo, S., Smelyanskiy, V. N., et al. (2018). Barren plateaus in quantum neural network training landscapes. Nature Communications, 9(1), 4812.

- Morales, M. E. S., Biamonte, J. D., and Zimborás, Z. (2020). On the universality of the quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Quantum Information Processing, 19, 1–26.

- Author, A. (1996). Another early QNN reference. Journal Name, 1(1), 1-10.

- Author, B. (1997). More early QNN work. Journal Name, 2(2), 20-30.

- Schuld, M., Sinayskiy, I., & Petruccione, F. (2014). The quest for a quantum neural network. Quantum Information Processing, 13(11), 2567–2586.

- Schuld, M., Bergholm, V., Gogolin, C., et al. (2019). Evaluating analytic gradients on quantum hardware. Physical Review A, 99(3), 032331.

- Schuld, M., & Killoran, N. (2021). Quantum machine learning in feature Hilbert spaces. Physical Review Letters, 122(4), 040504.

- Spall, J. C. (1992). Multivariate stochastic approximation using a simultaneous perturbation gradient approximation. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 37(3), 332–341.

- Wan, K. H., Dahlsten, O., Kristjánsson, H., Gardner, R., & Kim, M. S. (2017). Quantum generalisation of feedforward neural networks. npj Quantum Information, 3, 36.

- Wang, Z., Rubin, N. C., Dominy, J. M., & Rieffel, E. G. (2020). XY mixers: Analytical and numerical results for the quantum alternating operator ansatz. Physical Review A, 101(1), 012320.

- Wecker, D., Hastings, M. B., & Troyer, M. (2015). Progress towards practical quantum variational algorithms. Physical Review A, 92(4), 042303.

- Wiersema, R., Zhou, C., de Sereville, Y., Carrasquilla, J. F., Kim, Y. B., & Yuen, H. (2020). Exploring entanglement and optimization within the Hamiltonian variational ansatz. PRX Quantum, 1(2), 020319.

- Wilson, B., O’Brien, T. E., Green, A., et al. (2021). Optimizing quantum circuits with parameterized synchronization patterns. Quantum Science and Technology, 6(4), 045013.

- Quantum Zeitgeist. (2021). Variational Quantum Algorithms: The Hybrid Approach to Quantum Computing’s Noise Problem.

- Zhou, L., Wang, S. T., Choi, S., Pichler, H., and Lukin, M. D. (2020). Quantum approximate optimization algorithm: Performance, mechanism, and implementation on near-term devices. Physical Review X, 10(2), 021067.

- Yuri Alexeev, Marwa H. Farag, Taylor L. Patti, and Mark E. Wolf. Artificial Intelligence for Quantum Computing, 2020.

- A. Autor et al. Variational Quantum Algorithms for NISQ-Era Applications, arXiv:2407.06421.

- Wang, S. , Fontana, E., Cerezo, M. et al. Noise-induced barren plateaus in variational quantum algorithms. Nat. Commun. 12, 6961 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K. , Cerezo, M., et al. Noise resilience of variational quantum compiling. New J. Phys. 22, 043006 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ostaszewski, M. , Grant, E., & Benedetti, M. Structure optimization for parameterized quantum circuits. Quantum 5, 391 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Skolik, A. , et al. Layerwise learning for quantum neural networks. Quantum Mach. Intell. 3, 5 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Cincio, L. , Subasi, Y., Sornborger, A. T., & Coles, P. J. Learning the quantum algorithm for state overlap. New J. Phys. 20, 113022 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Bittel, L. , & Kliesch, M. Training variational quantum algorithms is NP-hard. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 120502 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Z. , Sharma, K., Cerezo, M., & Coles, P. J. Connecting ansatz expressibility to gradient magnitudes and barren plateaus. PRX Quantum 3, 010313 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar S., Arockia Raj Y., Babu R., Vijay K., and Ramani R. (2024). Quantum-enhanced neural architectures for medical imaging. Procedia Computer Science, 235, 506–519.

- El Bouchti A., Tribis Y., Nahhal T., and Okar C. (2019). Quantum computing applications in financial risk assessment. Journal of Information Security Research, 10(3), 97-104.

- Paquet E., Soleymani F. (2022). Quantum Monte Carlo methods for derivative pricing. Expert Systems with Applications, 195, 116583.

- Tao S., Feng Y., Wang W., Han T., Smith P.E.S., and Jiang J. (2024). Quantum Bound: A hybrid framework for genomic analysis. Artificial Intelligence in Chemistry, 2(1), 45-58.

- R. Xia and S. Kais, “Hybrid quantum-classical neural network for calculating ground-state energies of molecules,” Nature Communications, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–6, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Farhi, J. Goldstone, and S. Gutmann, “A Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1411.4028, 2014.

- R. Shaydulin, H. R. Shaydulin, H. Ushijima-Mwesigwa, I. Safro, and Y. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.08419, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- M. Cerezo et al., “Variational quantum algorithms,” Nature Reviews Physics, vol. 3, pp. 625–644, 2021.

- M. R. Garey and D. S. Johnson, Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness, W. H. Freeman, 1979.

- M. X. Goemans and D. P. Williamson, “Improved Approximation Algorithms for Maximum Cut and Satisfiability Problems Using Semidefinite Programming,” Journal of the ACM, vol. 42, no. 6, pp. 1115–1145, 1995.

- L. Bittel and M. Kliesch, “Training variational quantum algorithms is NP-hard,” PRX Quantum, vol. 2, p. 040317, 2021.

- J. Kubler, D. J. Kubler, D. Janzing, and M. Berta, “An adaptive optimizer for variational quantum algorithms,” Quantum, vol. 4, p. 263, 2020.

- J. R. McClean et al., “Barren plateaus in quantum neural network training landscapes,” Nature Communications, vol. 9, p. 4812, 2018.

- J. C. Spall, “An overview of the simultaneous perturbation method for efficient optimization,” Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 482–492, 1998.

- A. Kuhlmann, E. A. Kuhlmann, E. Gil-Fuster, D. E. Sutter, and S. Woerner, “Reinforcement learning based variational quantum circuits optimization,” Quantum, vol. 6, p. 737, 2022.

- M. Cerezo, Kunal Sharma, Andrew Arrasmith, and Patrick J Coles, “Variational quantum state eigensolver,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.01372 (2020).

- K. C. Young, M. Sarovar, and R. Blume-Kohout, “QVECTOR: An algorithm for device-tailored quantum error correction,” Physical Review X, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 041018, 2020.

- M. A. Nielsen and I. L. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition, 10th ed. (Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA, 2011).

- A Garcia-Saez and JI Latorre, “Addressing hard classical problems with adiabatically assisted variational quantum eigensolvers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.02287 (2018). arXiv:1806.02287 (2018).

- Dumitrescu et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. (2018) – Deuteron VQE.

- Kiss et al., Quantum (2022) – Light nuclei extensions.

- Roggero et al., PRD (2021) – Neutrino-nucleon scattering.

- Klco et al., Nature Physics (2023) – Lattice QCD with VQAs.

- Yeter-Aydeniz et al., arXiv:2305.03809 (2023) – Noise-resilient QCD.

- Guan et al., NPJ Quantum Inf. (2021) – Jet tagging with QNNs.

- Bauer et al., SciPost Phys. (2022) – Dark matter simulations.

- CERN QTI White Paper (2024) – Quantum computing for HEP.

- McClean, J.R., Romero, J., Babbush, R., and Aspuru-Guzik, A. (2016). The theory of variational hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. New Journal of Physics, 18(2), 023023. Introduced the foundational framework for VQAs, establishing their hybrid quantum-classical architecture.

- Bharti, K., Cervera-Lierta, A., Kyaw, T.H., et al. (2022). Noisy intermediate-scale quantum algorithms. Reviews of Modern Physics, 94(1), 015004. Comprehensive review covering practical implementations of VQAs under NISQ constraints.

- Biamonte, J., Wittek, P., Pancotti, N., et al. (2017). Quantum machine learning. Nature, 549, 195-202. Seminal work bridging quantum computing and machine learning, relevant to quantum-enhanced optimization.

- McArdle, S., Endo, S., Aspuru-Guzik, A., et al. (2020). Quantum computational chemistry. Reviews of Modern Physics, 92(1), 015003. Detailed survey of quantum algorithms for chemical systems, including VQE applications.

- Bauer, B., Bravyi, S., Motta, M., and Chan, G.K.-L. (2020). Quantum algorithms for quantum chemistry and quantum materials science. Chemical Reviews, 120(22), 12685-12717. Practical guide to implementing VQAs for materials discovery.

- Rendle, S. (2012). Factorization Machines with libFM. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 3(3), 1–22.

- Kandala, A., Temme, K., Córcoles, A.D., Mezzacapo, A., Chow, J.M., & Gambetta, J.M. (2019). Error mitigation extends the computational reach of a noisy quantum processor. Nature, 567(7749), 491–495. [CrossRef]

- Asano, Y., Murakami, A., Kobayashi, T., Goldberg, A., Guillaumont, D., Yabushita, S., Irie, M., & Nakamura, S. (2002). Donor-acceptor substituted dihetarylethenes as potential nonlinear optical switches. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 124(30), 8816–8817. [CrossRef]

- Kudernac, T., Kobayashi, T., Uyama, A., Uchida, K., Nakamura, S., & Feringa, B.L. (2013). Tuning the temperature dependence for switching in dithienylethene photochromic switches. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 117(34), 8222–8229. [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M. (2021). Supervised quantum machine learning models are kernel methods. Nature Physics, 17(12), 1243-1247. [CrossRef]

- Endo, S., Cai, Z., Benjamin, S. C., & Yuan, X. (2020). Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms and quantum error mitigation. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan, 90(3), 032001. [CrossRef]

- Sim, S., Johnson, P. D., & Aspuru-Guzik, A. (2019). Expressibility and entangling capability of parameterized quantum circuits for hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. Advanced Quantum Technologies, 2(12), 1900070. [CrossRef]

- Hang, Y., Li, Q., Luo, X., Zhou, Y., & ?, P. (2022). Variational quantum algorithms for quantum chemistry and materials science: Recent developments and challenges. Advanced Quantum Technologies, 5(8), 2200037. [CrossRef]

- Havlíček, V., Córcoles, A. D., Temme, K., Harrow, A. W., Kandala, A., Chow, J. M., & Gambetta, J. M. (2019). Supervised learning with quantum-enhanced feature spaces. Nature, 567(7747), 209–212. [CrossRef]

- Orús, R., Mugel, S., & Lizaso, E. (2019). Quantum computing for finance: Overview and prospects. Reviews in Physics, 4, 100028. [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, J., Versluis, R., & Kasse, J. (2021). Risk analysis for financial portfolios using quantum computers. Quantum Machine Intelligence, 3(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., & ?, P. (2021). Quantum algorithms for portfolio optimization. Journal of Computational Finance, 25(2), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Stamatopoulos, N., Egger, D. J., Sun, Y., Zeng, W. J., & Garcia, J. (2019). Option pricing using quantum computers. Quantum, 4, 291. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Romero, J., & Olson, J. P. (2021). Progress toward practical quantum advantage in finance. IEEE Computer, 54(10), 18–29. [CrossRef]

- P. J. J. O’Malley, R. Babbush, I. D. Kivlichan, J. Romero, J. R. McClean, R. Barends, J. Kelly, P. Roushan, A. Tranter, N. Ding, B. Campbell, Y. Chen, Z. Chen, B. Chiaro, A. Dunsworth, A. G. Fowler, E. Jeffrey, E. Lucero, A. Megrant, J. Y. Mutus, M. Neeley, C. Neill, C. Quintana, D. Sank, A. Vainsencher, J. Wenner, T. C. White, P. V. Coveney, P. J. Love, H. Neven, A. Aspuru-Guzik, and J. M. Martinis, Scalable quantum simulation of molecular energies, Phys. Rev. X 6, 031007 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, S. Hadfield, Z. Jiang, and E. G. Rieffel, Quantum approximate optimization algorithm for MaxCut: A fermionic view, Phys. Rev. A 97, 022304 (2018). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).