Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Context

1.2. Significance of Dataset Bias in Biometrics

1.3. Objectives and Scope of the Study

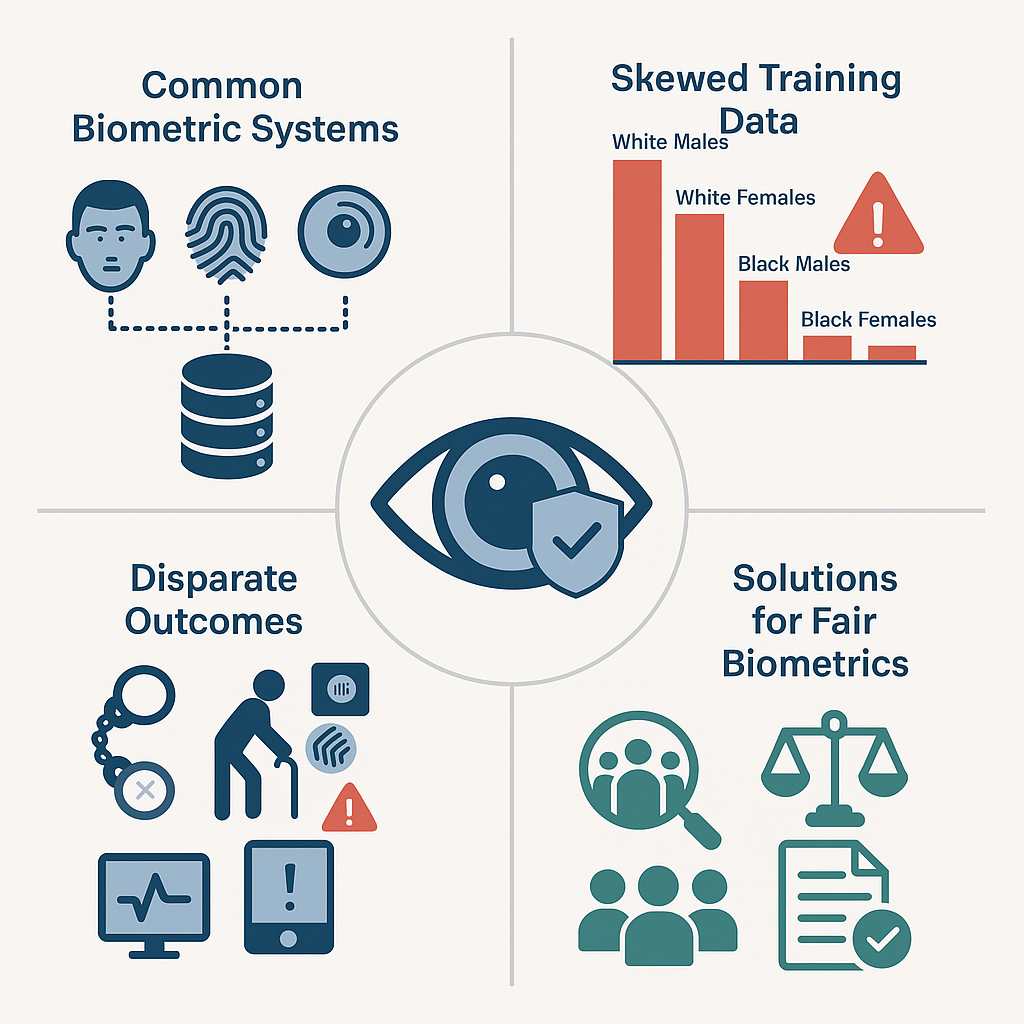

2. Understanding Dataset Bias

2.1. Definition and Types of Bias

2.2. Sources of Bias in Biometric Data Collection

2.3. Demographic Disparities and Underrepresentation

3. Impacts of Dataset Bias on Biometric Systems

3.1. Accuracy and Performance Discrepancies

3.2. Real-World Consequences for Marginalized Groups

3.3. Ethical and Legal Implications

4. Case Studies and Examples

4.1. Facial Recognition Failures

4.2. Fingerprint and Iris Recognition Bias

4.3. Regional and Cultural Representation Issues

5. Bias Detection and Measurement Techniques

5.1. Metrics and Evaluation Tools

5.2. Benchmark Datasets and Limitations

5.3. Transparency and Auditing Practices

6. Strategies for Mitigating Dataset Bias

6.1. Inclusive Data Collection and Curation

6.2. Algorithmic Fairness Techniques

6.3. Policy and Governance Recommendations

7. Research Gaps and Future Directions

7.1. Need for Global Collaboration

7.2. Calls for Standardized Ethical Guidelines

7.3. Opportunities for Interdisciplinary Research

8. Conclusions

8.1. Summary of Findings

8.2. The Road Ahead for Ethical Biometrics

References

- Davitaia, A. (2025). Machine Learning in Voice Recognition: Enhancing Human-Computer Interaction. Available at SSRN 5329570.

- Davitaia, A. (2025). Advancements in Fingerprint Recognition: Applications and the Role of Machine Learning. Available at SSRN 5268481.

- Davitaia, A. (2025). Optimizing Real-Time Traffic Management Using Java-Based Computational Strategies and Evaluation Models. Available at SSRN 5228096.

- Davitaia, A. (2025). Intelligent Finance: The Evolution and Impact of AI-Driven Advisory Services in FinTech. Available at SSRN 5285808.

- Davitaia, A. (2025). Recursive Techniques for Hierarchical Management in Digital Library Systems. Available at SSRN 5228100.

- Davitaia, A. (2025). Enhancing Library Management with Functional Programming: Dynamic Overdue Fee Calculation Using Lambda Functions. Available at SSRN 5228094.

- Davitaia, A. (2025). Choosing Agile SDLC for a Software Development Project Using React,. NET, and MySQL. Available at SSRN 5215308.

- Davitaia, A. (2025). Fingerprint-Based ATM Access Using Software Delivery Life Cycle. Available at SSRN 5215323.

- Davitaia, A. (2022). The Future of Translation: How AI is Changing the Game. Available at SSRN 5278221.

- Davitaia, A. (2024). From Risk Management to Robo-Advisors: The Impact of AI on the Future of FinTech. Available at SSRN 5281119.

- Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, 81, 77–91.

- Grother, P., Ngan, M., & Hanaoka, K. (2019). Face recognition vendor test (FRVT) Part 3: Demographic effects (NISTIR 8280). National Institute of Standards and Technology. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8280.

- Raji, I. D., & Buolamwini, J. (2019). Actionable auditing: Investigating the impact of publicly naming biased performance results of commercial AI products. Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 429–435. https://doi.org/10.1145/3306618.3314244.

- Jain, A. K., Ross, A., & Nandakumar, K. (2011). Introduction to biometrics. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77326-1.

- Klare, B. F., Burge, M. J., Klontz, J. C., Vorder Bruegge, R. W., & Jain, A. K. (2012). Face recognition performance: Role of demographic information. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 7(6), 1789–1801. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIFS.2012.2214212.

- Whittaker, M., Crawford, K., Dobbe, R., Fried, G., Kaziunas, E., Mathur, V., ... & West, S. M. (2018). AI Now Report 2018. AI Now Institute. https://ainowinstitute.org/AI_Now_2018_Report.pdf.

- Garvie, C., Bedoya, A. M., & Frankle, J. (2016). The perpetual line-up: Unregulated police face recognition in America. Georgetown Law, Center on Privacy & Technology. https://www.perpetuallineup.org/.

- Simonite, T. (2019, January 25). When it comes to gorillas, Google Photos remains blind. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/story/when-it-comes-to-gorillas-google-photos-remains-blind/.

- Dastin, J. (2018, October 10). Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight-idUSKCN1MK08G.

- Wilson, D., & Whittaker, M. (2021). Disability, bias, and AI. AI Now Institute. https://ainowinstitute.org/disabilitybiasai-2021.pdf.

- Osoba, O. A., & Welser, W. (2017). An intelligence in our image: The risks of bias and errors in artificial intelligence. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1744.html.

- NIST. (2021). Face recognition vendor test (FRVT) ongoing: Part 6A - Performance of automated face recognition algorithms. https://pages.nist.gov/frvt/.

- Howard, A., & Borenstein, J. (2018). The ugly truth about ourselves and our robot creations: The problem of bias and social inequity. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(5), 1521–1536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9975-2.

- Veale, M., & Binns, R. (2017). Fairer machine learning in the real world: Mitigating discrimination without collecting sensitive data. Big Data & Society, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717743530.

- Barocas, S., Hardt, M., & Narayanan, A. (2019). Fairness and machine learning: Limitations and opportunities. fairmlbook.org. https://fairmlbook.org/.

- Zhao, J., Wang, T., Yatskar, M., Ordonez, V., & Chang, K. (2017). Men also like shopping: Reducing gender bias amplification using corpus-level constraints. Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2979–2989.

- Jain, A. K., & Maltoni, D. (2021). Handbook of biometric anti-spoofing: Presentation attack detection. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87809-3.

- Keyes, O. (2019). The misgendering machines: Trans/HCI implications of automatic gender recognition. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359246.

- Koenecke, A., Nam, A., Lake, E., Nudell, J., Quartey, M., Mengesha, Z., ... & Goel, S. (2020). Racial disparities in automated speech recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(14), 7684–7689. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1915768117.

- Gebru, T., Morgenstern, J., Vecchione, B., Vaughan, J. W., Wallach, H., Daumé III, H., & Crawford, K. (2021). Datasheets for datasets. Communications of the ACM, 64(12), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1145/3458723.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).