Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Sustainable Supplier Segmentation

2.2. Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems

- a)

- Layer 1: In this layer the input values (x and y) in crisp format are converted into fuzzy sets equivalents. Their function can be given as:

- b)

- Layer 2: This layer combines all of the nodes of the previous layer with the objective of establishing the logical relationships among the activated membership functions. This layer represents the antecedent part of the decision-making rules, which realizes operations of the type “AND” or “OR”. The equation that represents the realized operation for this combination layer is given by:

- c)

- Layer 3: This layer normalizes the weights of the activated rules. Equation 3 describes the procedure.

- d)

- Layer 4: This is the layer of the adaptive nodes which represents the rule consequents. These consequents generate outputs for each activated rule according to Equation 4. The consequent value can be produced by a linear function or a constant function. The output value of this layer is calculated by the simple product of the consequent of each rule () and the weight of the rule activated in the third layer;

- e)

- Layer 5: This layer is composed of a fixed node which calculates a weighted sum of the outputs of the previous layer, as represented by Equation 5.

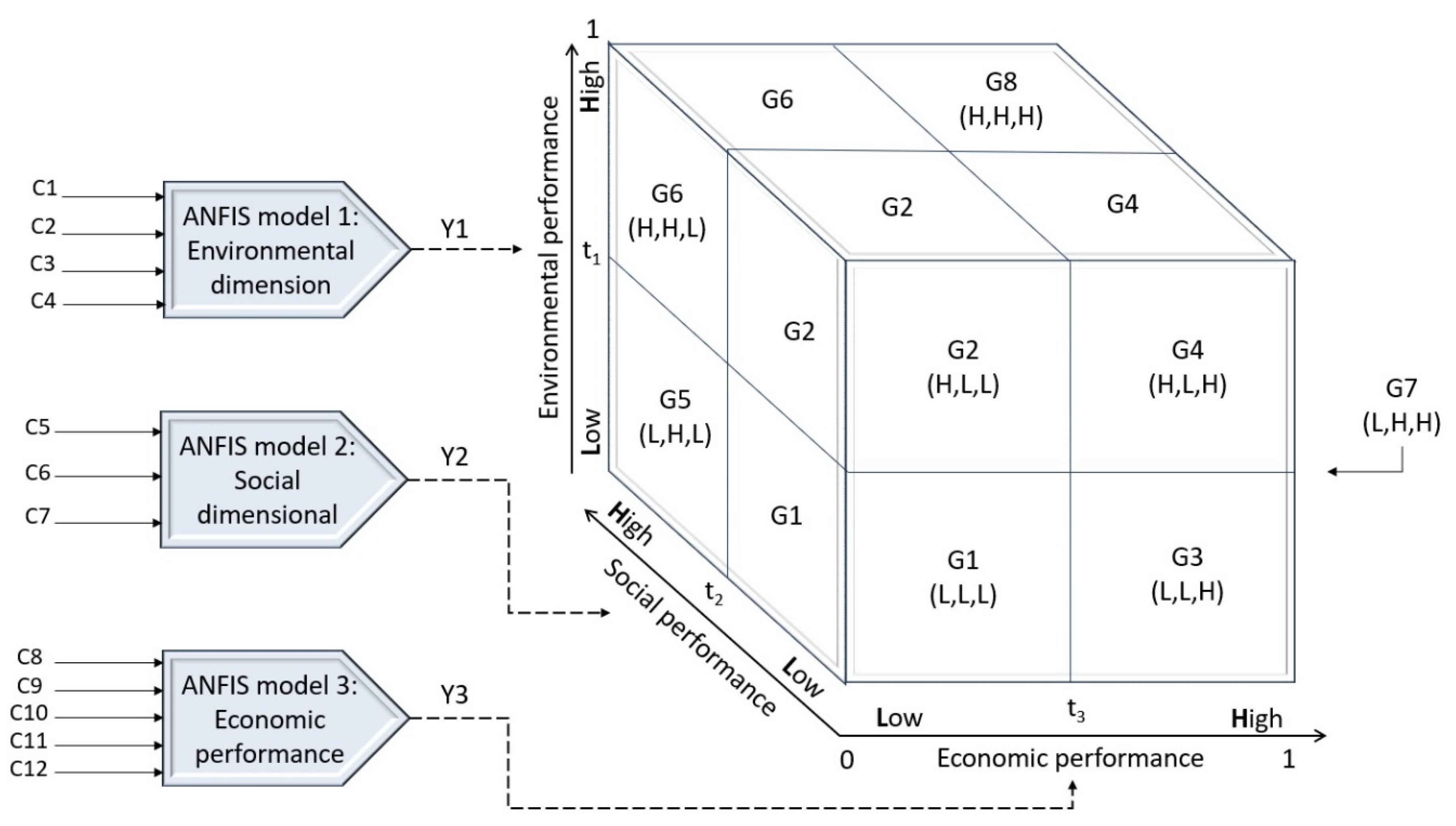

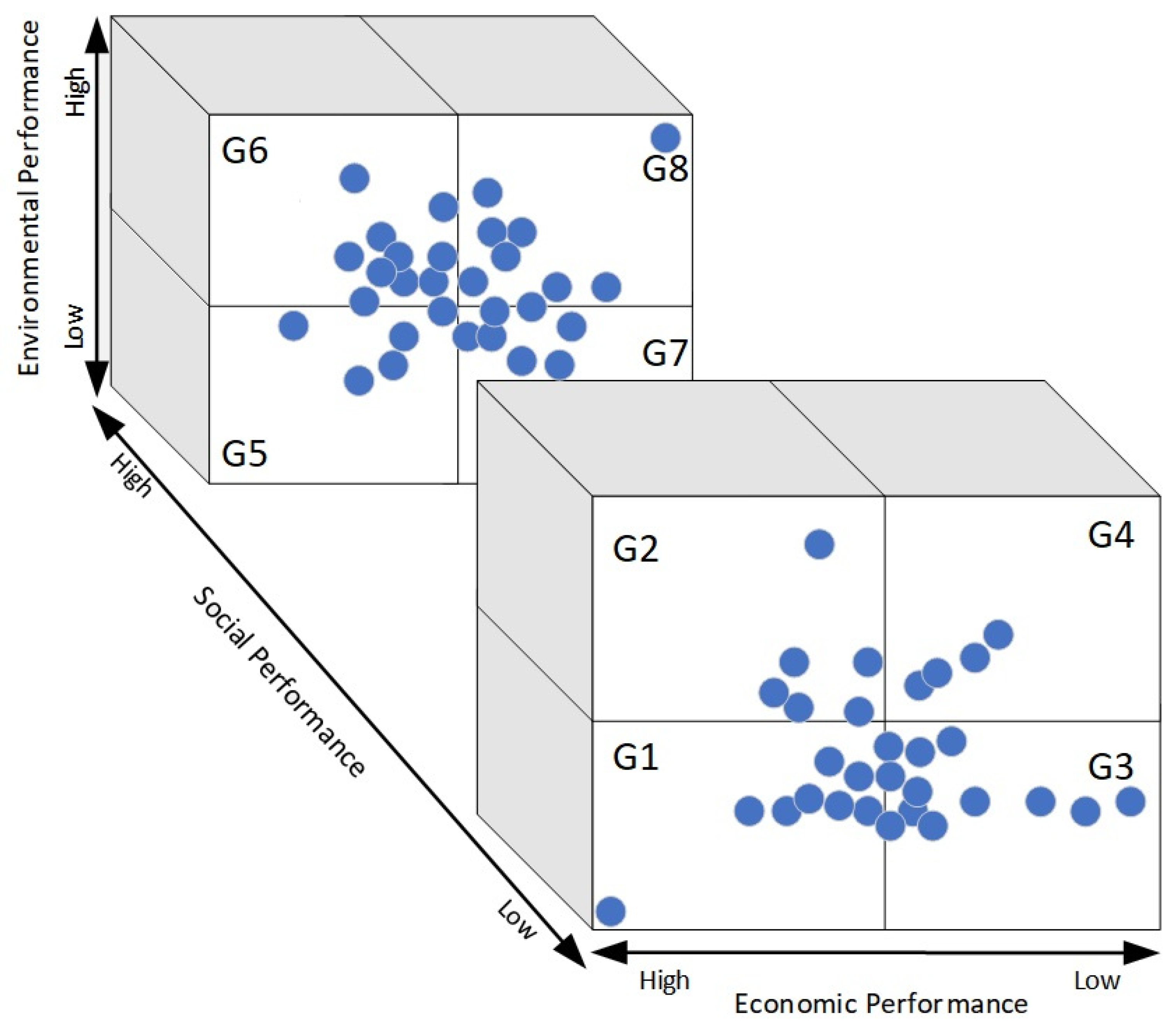

3. The Proposed Model for Sustainable Supplier Segmentation

- a)

- G1 (L, L, L) – This group consists of the suppliers which have presented the worst performance evaluations, or those which presented poor economic, environmental, and social performance. The suppliers in this group should be substituted if possible according to Lajimi et al. (2021). Otherwise, supplier development programs should be implemented to achieve improved supplier performance in the three dimensions of the TBL;

- b)

- G2 (H, L, L) – This group consists of suppliers which have achieved good environmental performance and poor economic and social performance. The suppliers in this segment generally focus on the efficient use of natural resources and the control and prevention of pollution;

- c)

- G3 (L, L, H) – This group consists of suppliers with good economic performance and poor social and environmental performance. They operate their supply chains with a focus on profits and are not concerned with environmental and social issues;

- d)

- G4 (H, L, H) – This group consists of suppliers with satisfactory economic and environmental performance, but poor social performance. They generally reduce costs through their efficient use of energy and natural resources;

- e)

- G5 (L, H, L) – This group consists of suppliers with good social performance and poor economic and environmental performance. They are focused on social justice. They emphasize diversity in their labor, human rights, a reduction in inequality, and the quality of life of their employees;

- f)

- G6 (H, H, L) – This groups consists of suppliers with poor economic performance and good social and environmental performance. They emphasize using a just portion of natural resources in both the domestic and international spheres;

- g)

- G7 (L, H, H) – This group consists of suppliers with good social and economic performance and poor environmental performance. These suppliers seek to reduce costs considering the social needs of society. They have ethical standards and ensure just business practices that protect the human rights of their employees;

- h)

- G8 (H, G, G) – This group consists of sustainable suppliers which have good social, economic, and environmental performance. They focus on improving their products and the quality of life of people, prioritizing environmental activities, and maximizing renewable natural resources at the least possible cost.

4. Application Case Study

4.1. Presentation of the Company

4.2. Application of the Proposed Model

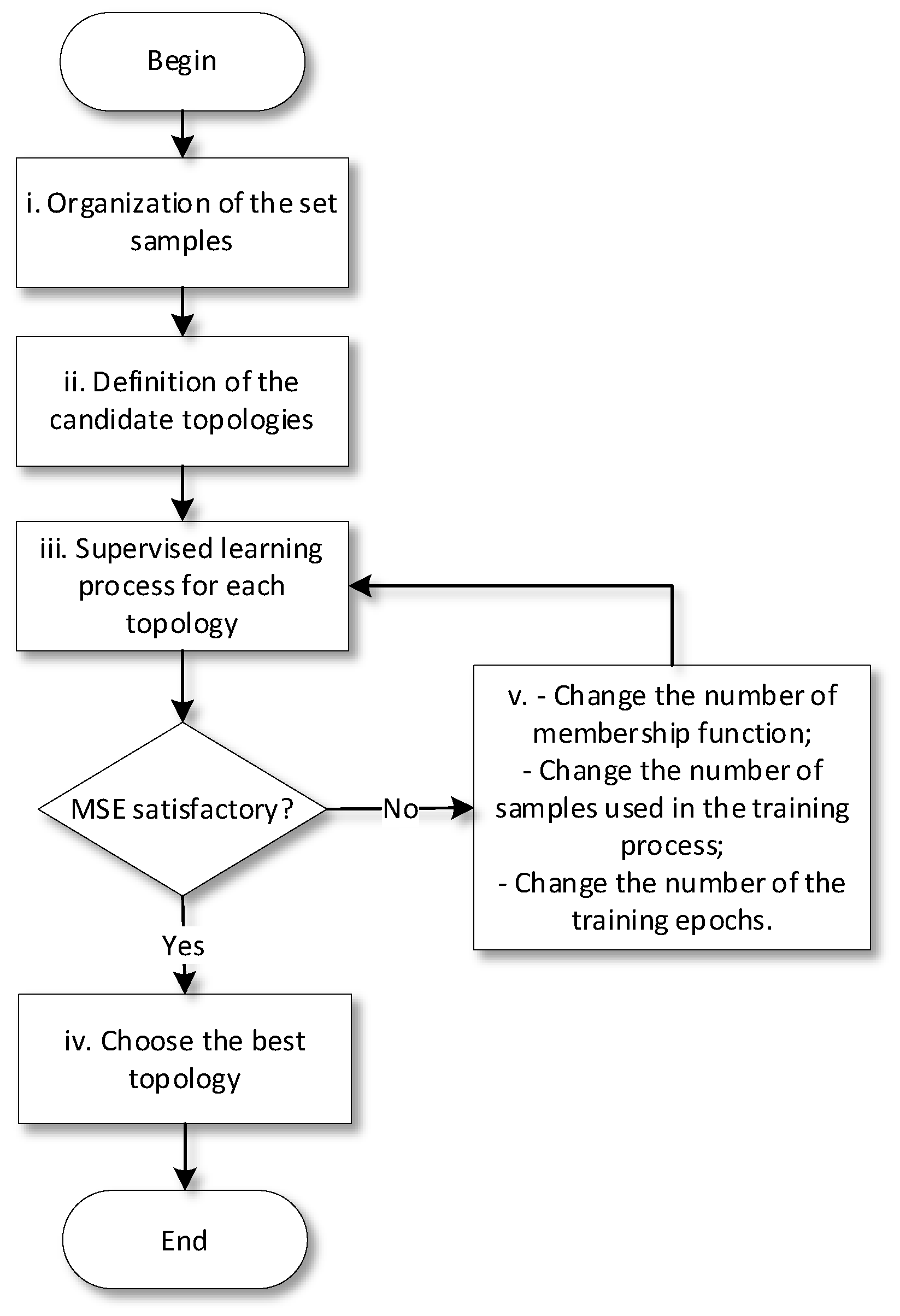

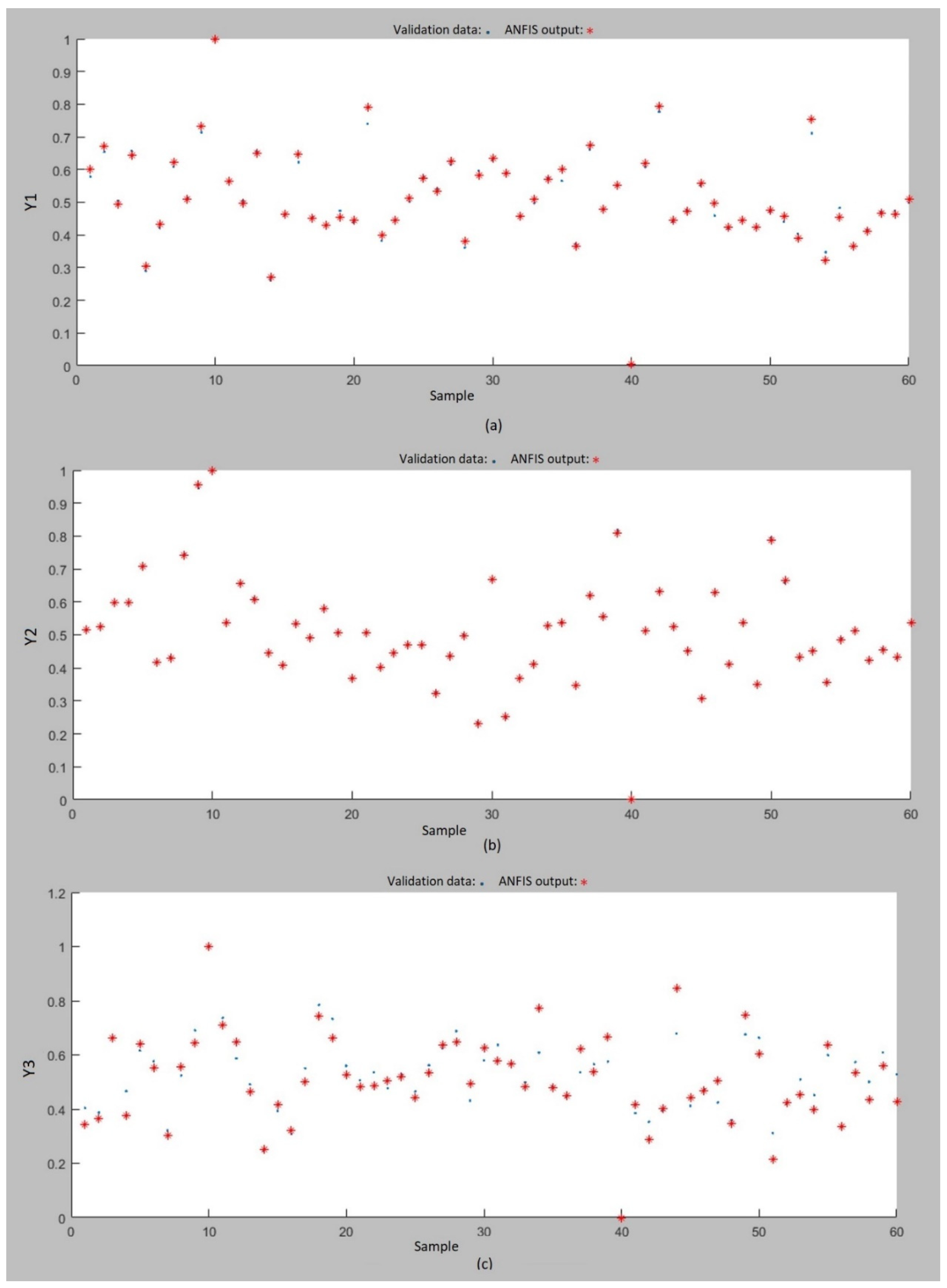

4.2.1. Stage 1: Definition, Training, and Validation of the ANFIS Models

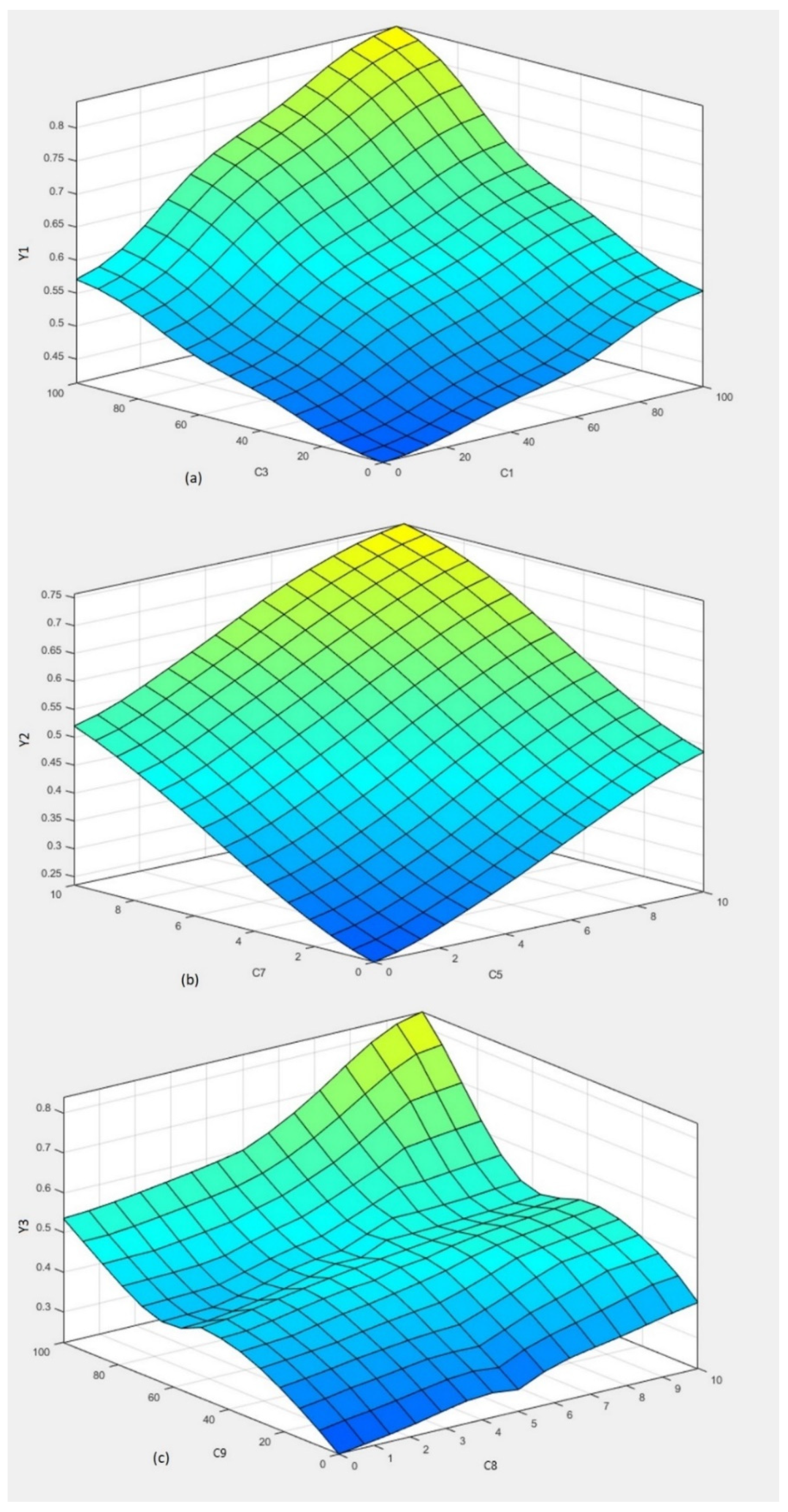

4.2.2. Stage 2: Application of the ANFIS Models

4.2.3. Stage 3: Supplier Categorization

4.3. Comparison of the Results with Previous Studies

5. Statistical Test Results

6. Conclusion

- By using a supervised learning method, this is the first supplier segmentation model that enables the use of historical performance data to automatically adjust the relationships between the variables. The use of ANFIS requires less training time to adjust its internal parameters than models based on neural networks or fuzzy inference;

- Due to its use of fuzzy input variables and fuzzy inference rules, this model is appropriate for supporting decision making based on DM judgments or imprecise numerical values. Another advantage is that it enables the use of both quantitative and qualitative criteria, which is essential in assessing social performance;

- The supervised learning process makes it possible to incorporate the available knowledge about supplier performance into the inference rules. This makes the results produced by the ANFIS models easily interpretable and makes it possible to identify which decision rules produced the results. The response surface graphs also contribute to a better understanding of the cause-and-effect relationships between the input variables and the output variable. Thus, transparency in the processing of information helps decision makers feel more secure in justifying their decisions.

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. An analysis of metrics used to measure performance in green and sustainable supply chains; Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015; Vol. 86, pp. 360–377. [Google Scholar]

- Akkoç, S. An empirical comparison of conventional techniques, neural networks and the three stages hybrid Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) model for credit scoring analysis: The case of Turkish credit card data; European Journal of Operational Research, 2012; Vol. 222, No 1, pp. 168–178. [Google Scholar]

- Akman, G. Evaluating suppliers to include green supplier development programs via fuzzy c-means and VIKOR methods; Computers & Industrial Engineering, 2015; Vol. 86, pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Aloini, D.; Dulmin, R.; Mininno, V.; Zerbino, P. Leveraging procurement related knowledge through a fuzzy-based DSS: a refinement of purchasing portfolio models; Journal of Knowledge Management, 2019; Vol. 23, No 6, pp. 1077–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Khan, S.A.; Vazquez-Brust, D. Sustainable buyer–supplier relationship capability development: a relational framework and visualization methodology; Annals of Operations Research, 2021; Vol. 304, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.; Rezaei, J.; Sarkis, J. Multicriteria green supplier segmentation; IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, 2017; Vol. 64, No 4, pp. 515–528. [Google Scholar]

- Bamakan, S.M.H.; Faregh, N.; ZareRavasan, A. Di-ANFIS: an integrated blockchain–IoT–big data-enabled framework for evaluating service supply chain performance; Journal of Computational Design and Engineering, 2021; Vol. 8, No 2, pp. 676–690. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini, A.; Benci, A.; Pellegrini, M.; Rossi, J. Supply chain redesign for lead-time reduction through Kraljic purchasing portfolio and AHP integration; Benchmarking: An International Journal, 2019; Vol. 26, No 4, pp. 1194–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, W.V.; Lima, F.R.; Junior. Decision Support Models for Supplier Segmentation: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the Brazilian Congress of Production Engineering (CONBREPRO), Brazil; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, W.V.; Lima, F.R.; Junior; Peinado, J.; Carpinetti, L.C.R. A Hesitant Fuzzy Linguistic TOPSIS model to support Supplier Segmentation; Journal of Contemporary Administration, 2022; Vol. 26, p. e210133. [Google Scholar]

- Boujelben, M.A. A unicriterion analysis based on the PROMETHEE principles for multicriteria ordered clustering; Omega, 2017; Vol. 69, pp. 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun, S.S; Kumru, M.; Kan, N.M. An integrated framework for sustainable supplier development through supplier evaluation based on sustainability indicators; Journal of Cleaner Production, 2022; Vol. 335, p. 130287. [Google Scholar]

- Day, M.; Magnan, G.M.; Moeller, M.M. Evaluating the bases of supplier segmentation: a review and taxonomy; Industrial Marketing Management, 2010; Vol. 39, No 4, pp. 625–639. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, L.; Akpinar, M.E.; Araz, C.; Ilgin, M.A. A green supplier evaluation system based on a new multi-criteria sorting method: VIKORSORT; Expert Systems with Applications, 2018; Vol. 114, pp. 479–487. [Google Scholar]

- Duc, D.A.; Van, L.H.; Yu, V.F.; Chou, S.Y.; Hien, N.V.; Chi, N.T.; Toan, D.V.; Dat, L.Q. A dynamic generalized fuzzy multi-criteria group decision making approach for green supplier segmentation; Plos One, 2021; Vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Fávero, L.P.; Belfiore, P. Manual de análise de dados: estatística e modelagem multivariada com Excel, SPSS e Stata; Rio de Janeiro; Elsevier, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Finger, G.W.S.; Lima, F.R.; Junior. A hesitant fuzzy linguistic QFD approach for formulating sustainable supplier development programs; International Journal of Production Economics, 2022; Vol. 247, p. 108428. [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi, P.S.; Moradi, M.; Salahi, M. Supplier Segmentation using fuzzy linguistic preference relations and fuzzy clustering; International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications, 2014; Vol. 6, pp. 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J-S.R. ANFIS: adaptive-network-based fuzzy inference system; IEEE Transactions on Systems, 1993; Vol. 23, No 3, pp. 665–685. [Google Scholar]

- Jharkharia, S.; Das, C. Low carbon supplier development: a fuzzy c-means and fuzzy formal concept analysis based analytical model; Benchmarking: An International Journal, 2019; Vol. 26, No 1, pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.; Singh, S.P. Multi-stage hybrid model for supplier selection and order allocation considering disruption risks and disruptive technologies; International Journal of Production Economics, 2021; Vol. 231, p. 107830. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, F.D.; Kaymaz, Y.; Unvan, Y.A. "Machine learning in supply chain management: a risk-based supplier segmentation application". In Business studies and new approaches; Lyon; Livre de Lyon, 2021; pp. 139–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lajimi, H.F.; "Sustainable supplier segmentation: a practical procedure"; Rezaei, J. Strategic Decision Making for Sustainable Management of Industrial Networks; Cham; Springer, 2021; pp. 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; et al. Multi-criteria group decision analytics for sustainable supplier relationship management in a focal manufacturing company; Journal of Cleaner Production, 2024; Vol. 476, p. 143690. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, F.R.; Junior; Oliveira, M.E.B.; Resende, C.H.L. An Overview of Applications of Hesitant Fuzzy Linguistic Term Sets in Supply Chain Management: The State of the Art and Future Directions; Mathematics, 2023; Vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, F.R.; Junior; Carpinetti, L.C.R. Combining SCOR® model and fuzzy TOPSIS for supplier evaluation and management; International Journal of Production Economics, 2016; Vol. 174, pp. 128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, F.R.; Junior; Carpinetti, L.C.R. An adaptive network-based fuzzy inference system to supply chain performance evaluation based on SCOR® metrics; Computers & Industrial Engineering, 2020; Vol. 139, p. 106191. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, S.C.; Sudjatmika, F.V. Solving multi-criteria supplier segmentation based on the modified FAHP for supply chain management: a case study; Soft Computing, 2016; Vol. 20, pp. 4981–4990. [Google Scholar]

- Matshabaphala, N.M.; Grobler, J. Supplier segmentation: a case study of Mozambican cassava farmers; The South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 2021; Vol. 32, No 1, pp. 196–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mavi, R.K.; Zarbakhshnia, N.; Mavi, N.K.; Kazemi, S. Clustering sustainable suppliers in the plastics industry: A fuzzy equivalence relation approach; Journal of Environmental Management, 2023; Vol. 345, p. 118811. [Google Scholar]

- Mavi, R.K.; Mavi, N.K.; Goh, M. Modeling corporate entrepreneurship success with ANFIS; Operational Research, 2017; Vol. 17, pp. 213–238. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, M.; Ferreira, L. Development of a purchasing portfolio model: an empirical study in a Brazilian hospital; Journal Production Planning & Control, 2018; Vol. 29, No 7, pp. 571–585. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.; Runger, G. Applied statistics and probability for engineers; Hoboken: Wiley, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Osiro, L.; Lima, F.R.; Junior; Carpinetti, L.C.R. A fuzzy logic approach to supplier evaluation for development; International Journal of Production Economics, 2014; Vol. 153, pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Özkana, G.; Inal, M. Comparison of neural network application for fuzzy and ANFIS approaches for multi-criteria decision-making problems; Applied Soft Computing, 2014; Vol. 24, pp. 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Parkouhi, S.V.; Ghadikolaei, A.S.; Lajimi, H.F. Resilient supplier selection and segmentation in grey environment; Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019; Vol. 207, pp. 1123–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Paybarjay, H.; Lajimi, H.F.; Zolfani, S.H. An investigation of supplier development through segmentation in sustainability dimensions; Environment, Development and Sustainability, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pedroso, C.B.; Tate, W.L.; Silva, A.L.; Carpinetti, L.C.R. Supplier development adoption: A conceptual model for triple bottom line (TBL) outcomes; Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021; Vol. 314, p. 127886. [Google Scholar]

- Rahiminia, M.; Razmi, J.; Shahrabi Farahani, S.; Sabbaghnia, A. Cluster-based supplier segmentation: a sustainable data-driven approach; Modern Supply Chain Research and Applications, 2023; Vol. 5, No 3, pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh, G.; Raju, R. A fuzzy inference approach to supplier segmentation for strategic development; The South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 2021; Vol. 32, No 1, pp. 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rashidi, K.; Noorizadeh, A.; Kannan, D.; Cullinane, K. Applying the triple bottom line in sustainable supplier selection: a meta-review of the state-of-the-art; Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020; Vol. 269, p. 122001. [Google Scholar]

- Resende, C.H.L.; Lima, F.R.; Junior; Carpinetti, L.C.R. Decision-making models for formulating and evaluating supplier development programs: a state-of-the-art review and research paths; Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review, 2023; Vol. 180, p. 103340. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, R.; Villegas, J.G. Supplier evaluation and classification in a Colombian motorcycle assembly company using data envelopment analysis; Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 2019; Vol. 32, No 2, pp. 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, J.; Kadzinski, M.; Vana, C.; Tavasszy, L. Embedding carbon impact assessment in multi-criteria supplier segmentation using ELECTRE TRI-rC", Annals of Operations Research, 2017.

- Rezaei, J.; Lajimi, H.F. Segmenting supplies and suppliers: bringing together the purchasing portfolio matrix and the supplier potential matrix; International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 2019; Vol. 22, No 4, pp. 419–436. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, J.; Ortt, R. Multi-criteria supplier segmentation using a fuzzy preference relation based AHP; European Journal of Operational Research, 2013a; Vol. 225, No 1, pp. 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, J.; Ortt, R. Supplier segmentation using fuzzy logic; Industrial Marketing Management, 2013b; Vol. 42, No 4, pp. 507–517. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, J.; Wang, J.; Tavasszy, L. Linking supplier development to supplier segmentation using Best Worst Method; Expert Systems with Applications, 2015; Vol. 42, No 23, pp. 9152–9164. [Google Scholar]

- Rius-Sorolla, G.; Estelles-Miguel, S.; Rueda-Armengot, C. Multivariable supplier segmentation in sustainable supply chain management; Sustainability, 2020; Vol. 12, No 11. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, L.F.O.M; Osiro, L.; Lima, R.H.P. A model based on 2-tuple fuzzy linguistic representation and Analytic Hierarchy Process for supplier segmentation using qualitative and quantitative criteria; Expert Systems with Applications, 2017; Vol. 79, pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, V.B.; Cabral, L.P.B.; Schramm, F. Approaches for supporting sustainable supplier selection-A literature review; Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020; Vol. 273, p. 123089. [Google Scholar]

- Segura, M.; Maroto, C. A multiple criteria supplier segmentation using outranking and value function methods; Expert Systems with Applications, 2017; Vol. 69, pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shiralkar, K.; Bongale, A.; Kumar, S. Nos with decision making methods for supplier segmentation in supplier relationship management: a literature review; Materials Today: Proceedings, 2022; Vol. 50, No 5, pp. 1786–1792. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, I.N.; Spati, D.H.; Flauzino, R.A. Redes neurais artificiais: para engenharia e ciências aplicadas; São Paulo; Artliber, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, N.; Gunasekaran, A. Cleaner supply-chain management practices for twenty-first-century organizational competitiveness: Practice-performance framework and research propositions; International Journal of Production Economics, 2015; Vol. 164, pp. 216–233. [Google Scholar]

- Taghipour, A.; Fooladvand, A.; Khazaei, M.; Ramezani, M. Criteria Clustering and Supplier Segmentation Based on Sustainable Shared Value Using BWM and PROMETHEE; Sustainability, 2023; Vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Ruiz, A.; Ravindran, R. Multiple Criteria Framework for the Sustainability Risk Assessment of a Supplier Portfolio; Journal of Cleaner Production, 2018; Vol. 172, pp. 4478–4493. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, K.; Fröhling, M.; Schultmann, F. Sustainable supplier management a review of models supporting sustainable supplier selection, monitoring and development; International Journal of Production Research, 2016; Vol. 54, No 5, pp. 1412–144. [Google Scholar]

| Torres-Ruiz and Ravindran (2018) | Rius-Sorolla et al. (2020) | Borges et al. (2022) | Coşkun et al. (2022) | Mavi et al. (2023) | Paybarjay et al. (2023) | Rahiminia et al. (2023) | Taghipour et al. (2023) | Li et al. (2024) | Other studies found in the literature (Table 2) | Our Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Does it offer support for sustainable supplier segmentation? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Does it have a supervised learning process? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Is segmentation based on economic, environmental and social dimensions? | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Is there compensation among the TBL criteria? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | N/A | No |

| Does it have the capacity to model non-linear relationships between input and output variables? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Most do not, with the exception of the models based on fuzzy inference | Yes |

| Does it deal with uncertainty in the decision-making process? | Yes | No | Yes | Partially | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Some of the studies deal with it. | Yes |

| Economic criteria | Environmental criteria | Social criteria |

|---|---|---|

| After-sales support (Rezaei and Lajimi, 2019) Communication (Zimmer et al., 2016) Cost (Resende et al., 2023) Delivery time (Rius-Sorolla et al., 2020) Financial capabilities (Borges et al., 2022) Flexibility (Resende et al., 2023) Geographic location (proximity) (Rezaei and Lajimi, 2019) Innovation (Finger and Lima, 2022) Long-term relationship (Rezaei and Lajimi, 2019) Quality (Lajimi, 2021) Research and development (Kar, 2015) Supply chain resilience (Büyükozkan et al., 2017) Service capabilities (Lajimi, 2021) Technological Capability (Rius-Sorolla et al., 2020) |

Biodiversity and ecological impacts (Büyükozkan and Karabulut, 2017) Emissions control (Resende et al., 2023) Energy efficiency (Bai et al., 2017) Environmental certifications (Borges et al. 2022) Environmental management system (Lajimi, 2021) Environmental policies and audits (Ahi and Searcy, 2015) Green packaging (Bai et al., 2017) Green product design (Resende et al., 2023) Recycling programs (Demir et al., 2018) Resource consumption (Resende et al., 2023) Water consumption (Finger and Lima, 2022) Waste management (Resende et al., 2023) |

Child labor (Zimmer et al., 2016) Egalitarian labor sources (Lajimi, 2021) Discrimination (Zimmer et al., 2016) Diversity (Zimmer et al., 2016) Employee satisfaction (Ahi and Searcy, 2015) Employment practices (Lajimi, 2021) Ethical standards (Rezaei and Lajimi, 2019) Health and safety (Finger and Lima, 2022) Human capital investment (Subramanian and Gunasekaran, 2015) Influence of the local community (Resende et al., 2023) Job opportunities (Lajimi, 2021) Supporting educational institutions (Ahi and Searcy, 2015) Supporting community projects (Ahi and Searcy, 2015) |

| Author(s) | Decision-making techniques | Segmentation dimensions | Supply Chain Management Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Green | Agile | Resilient | Sustainable | |||

| Akman (2015) | Fuzzy c-means and VIKOR (Vlsekriterijumska Optimizacija I KOmpromisno Resenje in Serbian) | Does not adopt segmentation dimensions | X | ||||

| Aloini et al. (2019) | Fuzzy inference | Supplier attractiveness and strength of the relationship | X | ||||

| Bai et al. (2017) | Rough Sets, VIKOR and fuzzy c-means | Supplier capabilities and willingness | X | ||||

| Bianchini et al. (2019) | AHP | Profit impact and supply risk | X | ||||

| Borges et al. (2022) | Hesitant Fuzzy-TOPSIS (Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to the Ideal Solution) | Supplier capabilities and willingness | X | ||||

| Boujelben (2017) | PROMETHEE (Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluation) | Supplier capabilities and willingness | X | ||||

| Coşkun et al. (2022) | ANP (Analytic Network Process), PROMETHEE, and cluster analysis | Economic, environmental, and social | |||||

| Demir et al. (2018) | VIKORSORT | Does not adopt segmentation dimensions | X | ||||

| Duc et al. (2021) | Fuzzy logic | Supplier capabilities and willingness | X | ||||

| Haghighi et al. (2014) | Fuzzy-AHP and Fuzzy c-means | Supplier capabilities and willingness | X | ||||

| Jharkharia and Das (2019) | Fuzzy c-means and Fuzzy formal concept analysis | Supplier investment decisions and supplier collaboration decisions | X | ||||

| Kaur and Singh (2020) | DEA (Data Envelopment Analysis) | Does not adopt segmentation dimensions | X | ||||

| Keskin and Kaymanz (2021) | K-means | Does not adopt segmentation dimensions | X | ||||

| Li et al. (2024) | Bayesian best-worst method and Canopy-K-Means clustering algorithm | Economic, environmental, and social | X | ||||

| Lima and Carpinetti (2016) | Fuzzy-TOPSIS | Cost and delivery performance | X | ||||

| Lo and Sudjatmika (2016) | Fuzzy-AHP | Supplier capabilities and willingness | X | ||||

| Matshabaphala and Grobler (2021) | K-means | Does not adopt segmentation dimensions | X | ||||

| Mavi et al. (2023) | Fuzzy-AHP and Fuzzy equivalence relation | Economic, environmental, social, and risk | X | ||||

| Medeiros and Ferreira (2018) | Fuzzy-TOPSIS | Profit impact and supply risk | X | ||||

| Osiro et al. (2014) | Fuzzy inference | Potential for partnership and delivery performance | X | ||||

| Parkouhi et al. (2019) | Grey DEMATEL (Decision Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory) and grey simple additive weighting technique | Resiliency enhancer and resiliency reducer | X | ||||

| Paybarjay et al. (2023) | BWM (Best–Worst Method) and Grey SAW (Grey Simple Additive Weighting) | Economic, environmental and social | X | ||||

| Rahiminia et al. (2023) | BWM and K-means | Profit impact and supply risk | X | ||||

| Rajesh and Raju (2021) | Fuzzy inference | Agility capability and business excellence | X | ||||

| Restrepo and Villegas (2019) | DEA | Diversity efficiency and cross efficiency | X | ||||

| Rezaei and Lajimi (2019) | BWM (Best Worst Method) | Supplier capabilities and supplier willingness | X | ||||

| Rezaei and Ortt (2013a) | Fuzzy preference relation based AHP | Supplier capabilities and supplier willingness | X | ||||

| Rezaei and Ortt (2013b) | AHP | Supplier capabilities and supplier willingness | X | ||||

| Rezaei et al. (2017) | ELECTRE (ÉLimination Et Choix Traduisant la REalité, in French) TRI-rC | Supplier capabilities and supplier willingness | X | ||||

| Rezaei et al. (2015) | BWM | Supplier capabilities and supplier willingness | X | ||||

| Rius-Sorolla et al. (2020) | Procedure based on arithmetic mean | Profit impact and supply risk | X | ||||

| Santos et al. (2017) | AHP and Fuzzy 2-tuple | Supplier capabilities and supplier willingness | X | ||||

| Segura and Maroto (2017) | AHP, PROMETHEE, and MAUT (Multi-Attribute Utility Theory) | Critical performance and strategic performance | X | ||||

| Taghipour et al. (2023) | BWM and PROMETHEE | Critical performance and strategic performance of suppliers | X | ||||

| Torres-Ruiz and Ravindran (2018) | AHP | Supplier risks, country risks, and risk management practice | X | ||||

| Performance dimension | Supplier development strategies | Supplier groups |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental |

|

G1 G3 G5 G7 |

| Social |

|

G1 G2 G3 G4 |

| Economic |

|

G1 G2 G5 G6 |

| Suppliers | Supplier scores (inputs) | Y1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | ||

| F1 | 100 | 6 | 48 | 62 | 0.5845 |

| F2 | 93 | 9 | 8 | 51 | 0.5453 |

| F3 | 69 | 2 | 69 | 62 | 0.5024 |

| F4 | 90 | 9 | 59 | 70 | 0.6215 |

| F5 | 76 | 5 | 11 | 94 | 0.3797 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| F200 | 68 | 6 | 35 | 59 | 0.4987 |

| Description of the parameters | Tested values |

|---|---|

| Membership function type: determines the quantitative representation and behavior of input variables. | Triangular, trapezoidal, and Gaussian functions (Mavi et al., 2017; Bamakan et al., 2021). |

| Consequent type: determines the type of the output for each activated rule. | Linear functions and constant values (Jang 1993; Lima and Carpinetti, 2020). |

| Number of fuzzy membership functions: determines the partition granularity of the fuzzy input variables. | 3, 4 and 5 functions (Akkoç, 2012; Mavi et al., 2017). |

| Fuzzy operator: responsible for the type of aggregation operations among the degrees of activated membership functions. | Minimum and algebraic product operators (Jang, 1993; Lima and Carpinetti, 2020). |

| Candidate topology | Number of inference rules | Membership function type | Consequent type | Number of fuzzy membership functions | Fuzzy operator | Training MSE | Validation MSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 81 | Triangular | Crisp | 3 | Minimum | 2.738 x 10-04 | 3.518 x 10-03 |

| 2 | 81 | Triangular | Crisp | 3 | Product | 4.277 x 10-06 | 3.820 x 10-04 |

| 3 | 256 | Triangular | Crisp | 4 | Minimum | 2.719 x 10-11 | 2.885 x 10-03 |

| 4 | 256 | Triangular | Crisp | 4 | Product | 5.659 x 10-12 | 1.056 x 10-02 |

| 5 | 625 | Triangular | Crisp | 5 | Minimum | 8.425 x 10-12 | 2.641 x 10-02 |

| 6 | 625 | Triangular | Crisp | 5 | Product | 3.557 x 10-12 | 6.540 x 10-02 |

| 7 | 81 | Triangular | Linear | 3 | Minimum | 2.597 x 10-15 | 1.073 x 10-02 |

| 8 | 81 | Triangular | Linear | 3 | Product | 5.239 x 10-15 | 2.269 x 10-03 |

| 9 | 256 | Triangular | Linear | 4 | Minimum | 2.606 x 10-15 | 4.776 x 10-03 |

| 10 | 256 | Triangular | Linear | 4 | Product | 6.729 x 10-15 | 1.058 x 10-02 |

| 11 | 625 | Triangular | Linear | 5 | Minimum | 5.544 x 10-15 | 2.667 x 10-02 |

| 12 | 625 | Triangular | Linear | 5 | Product | 8.285 x 10-15 | 4.669 x 10-02 |

| 13 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 3 | Minimum | 6.117 x 10-04 | 4.336 x 10-02 |

| 14 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 3 | Product | 5.414 x 10-04 | 1.340 x 10-01 |

| 15 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 4 | Minimum | 8.607 x 10-06 | 8.072 x 10-02 |

| 16 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 4 | Product | 1.028 x 10-09 | 1.270 x 10-01 |

| 17 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 5 | Minimum | 1.285 x 10-11 | 9.416 x 10-02 |

| 18 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 5 | Product | 6.073 x 10-12 | 1.321 x 10-01 |

| 19 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 3 | Minimum | 9.499 x 10-15 | 2.353 x 10-02 |

| 20 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 3 | Product | 1.224 x 10-14 | 2.769 x 10-02 |

| 21 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 4 | Minimum | 7.910 x 10-14 | 4.623 x 10-02 |

| 22 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 4 | Product | 6.299 x 10-14 | 5.915 x 10-02 |

| 23 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 5 | Minimum | 4.237 x 10-14 | 9.806 x 10-02 |

| 24 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 5 | Product | 4.415 x 10-14 | 1.183 x 10-01 |

| 25 | 81 | Gaussian | Crisp | 3 | Minimum | 8.543 x 10-05 | 1.428 x 10-03 |

| 26 | 81 | Gaussian | Crisp | 3 | Product | 2.381 x 10-05 | 2.380 x 10-04 |

| 27 | 256 | Gaussian | Crisp | 4 | Minimum | 1.626 x 10-11 | 1.565 x 10-03 |

| 28 | 256 | Gaussian | Crisp | 4 | Product | 1.594 x 10-11 | 1.032 x 10-02 |

| 29 | 625 | Gaussian | Crisp | 5 | Minimum | 8.993 x 10-12 | 1.198 x 10-02 |

| 30 | 625 | Gaussian | Crisp | 5 | Product | 2.690 x 10-12 | 7.195 x 10-02 |

| 31 | 81 | Gaussian | Linear | 3 | Minimum | 1.535 x 10-15 | 4.037 x 10-03 |

| 32 | 81 | Gaussian | Linear | 3 | Product | 1.376 x 10-14 | 7.782 x 10-03 |

| 33 | 256 | Gaussian | Linear | 4 | Minimum | 1.833 x 10-15 | 3.658 x 10-03 |

| 34 | 256 | Gaussian | Linear | 4 | Product | 1.235 x 10-14 | 1.351 x 10-02 |

| 35 | 625 | Gaussian | Linear | 5 | Minimum | 3.656 x 10-15 | 1.296 x 10-02 |

| 36 | 625 | Gaussian | Linear | 5 | Product | 2.567 x 10-14 | 4.822 x 10-02 |

| Candidate topology | Number of inference rules | Membership function type | Consequent type | Number of fuzzy membership functions | Fuzzy operator | Training MSE | Validation MSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 | 81 | Triangular | Crisp | 3 | Minimum | 3.075 x 10-04 | 5.539 x 10-04 |

| 38 | 81 | Triangular | Crisp | 3 | Product | 7.921 x 10-06 | 1.349 x 10-05 |

| 39 | 256 | Triangular | Crisp | 4 | Minimum | 1.063 x 10-04 | 3.618 x 10-04 |

| 40 | 256 | Triangular | Crisp | 4 | Product | 1.697 x 10-06 | 2.178 x 10-05 |

| 41 | 625 | Triangular | Crisp | 5 | Minimum | 8.705 x 10-06 | 2.077 x 10-02 |

| 42 | 625 | Triangular | Crisp | 5 | Product | 2.850 x 10-10 | 8.717 x 10-03 |

| 43 | 81 | Triangular | Linear | 3 | Minimum | 8.052 x 10-07 | 1.389 x 10-04 |

| 44 | 81 | Triangular | Linear | 3 | Product | 9.466 x 10-08 | 5.206 x 10-05 |

| 45 | 256 | Triangular | Linear | 4 | Minimum | 3.210 x 10-14 | 1.606 x 10-04 |

| 46 | 256 | Triangular | Linear | 4 | Product | 4.448 x 10-15 | 9.201 x 10-05 |

| 47 | 625 | Triangular | Linear | 5 | Minimum | 6.219 x 10-16 | 7.544 x 10-03 |

| 48 | 625 | Triangular | Linear | 5 | Product | 1.308 x 10-15 | 1.153 x 10-02 |

| 49 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 3 | Minimum | 7.520 x 10-05 | 1.167 x 10-04 |

| 50 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 3 | Product | 7.542 x 10-05 | 1.171 x 10-04 |

| 51 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 4 | Minimum | 2.845 x 10-04 | 5.836 x 10-02 |

| 52 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 4 | Product | 1.105 x 10-04 | 4.418 x 10-04 |

| 53 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 5 | Minimum | 1.218 x 10-04 | 2.826 x 10-01 |

| 54 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 5 | Product | 1.076 x 10-04 | 6.911 x 10-02 |

| 55 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 3 | Minimum | 9.025 x 10-07 | 1.946 x 10-03 |

| 56 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 3 | Product | 1.542 x 10-07 | 5.054 x 10-04 |

| 57 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 4 | Minimum | 1.836 x 10-13 | 1.012 x 10-03 |

| 58 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 4 | Product | 7.792 x 10-14 | 1.052 x 10-03 |

| 59 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 5 | Minimum | 8.016 x 10-08 | 4.529 x 10-02 |

| 60 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 5 | Product | 8.016 x 10-08 | 4.978 x 10-02 |

| 61 | 81 | Gaussian | Crisp | 3 | Minimum | 7.841 x 10-05 | 1.242 x 10-04 |

| 62 | 81 | Gaussian | Crisp | 3 | Product | 6.943 x 10-06 | 1.125 x 10-05 |

| 63 | 256 | Gaussian | Crisp | 4 | Minimum | 2.093 x 10-05 | 5.461 x 10-05 |

| 64 | 256 | Gaussian | Crisp | 4 | Product | 7.844 x 10-07 | 9.769 x 10-06 |

| 65 | 625 | Gaussian | Crisp | 5 | Minimum | 5.196 x 10-07 | 1.142 x 10-01 |

| 66 | 625 | Gaussian | Crisp | 5 | Product | 1.194 x 10-09 | 3.517 x 10-03 |

| 67 | 81 | Gaussian | Linear | 3 | Minimum | 7.606 x 10-07 | 2.097 x 10-04 |

| 68 | 81 | Gaussian | Linear | 3 | Product | 1.781 x 10-08 | 1.088 x 10-04 |

| 69 | 256 | Gaussian | Linear | 4 | Minimum | 3.571 x 10-14 | 5.159 x 10-05 |

| 70 | 256 | Gaussian | Linear | 4 | Product | 2.344 x 10-14 | 8.415 x 10-05 |

| 71 | 625 | Gaussian | Linear | 5 | Minimum | 1.448 x 10-15 | 1.921 x 10-03 |

| 72 | 625 | Gaussian | Linear | 5 | Product | 4.698 x 10-15 | 1.287 x 10-02 |

| Candidate topology | Number of inference rules | Membership function type | Consequent type | Number of fuzzy membership functions | Fuzzy operator | Training MSE | Validation MSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 73 | 81 | Triangular | Crisp | 3 | Minimum | 1.385 x 10-09 | 9.198 x 10-03 |

| 74 | 81 | Triangular | Crisp | 3 | Product | 1.065 x 10-11 | 8.355 x 10-03 |

| 75 | 256 | Triangular | Crisp | 4 | Minimum | 1.542 x 10-11 | 3.852 x 10-02 |

| 76 | 256 | Triangular | Crisp | 4 | Product | 2.761 x 10-12 | 1.358 x 10-01 |

| 77 | 625 | Triangular | Crisp | 5 | Minimum | 3.018 x 10-11 | 1.183 x 10-01 |

| 78 | 625 | Triangular | Crisp | 5 | Product | 3.212 x 10-12 | 2.199 x 10-01 |

| 79 | 81 | Triangular | Linear | 3 | Minimum | 6.159 x 10-16 | 1.215 x 10-02 |

| 80 | 81 | Triangular | Linear | 3 | Product | 5.302 x 10-16 | 1.175 x 10-02 |

| 81 | 256 | Triangular | Linear | 4 | Minimum | 9.885 x 10-16 | 4.131 x 10-02 |

| 82 | 256 | Triangular | Linear | 4 | Product | 6.336 x 10-15 | 6.981 x 10-02 |

| 83 | 625 | Triangular | Linear | 5 | Minimum | 2.984 x 10-15 | 1.165 x 10-01 |

| 84 | 625 | Triangular | Linear | 5 | Product | 2.704 x 10-15 | 1.551 x 10-01 |

| 85 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 3 | Minimum | 2.777 x 10-05 | 8.711 x 10-02 |

| 86 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 3 | Product | 1.101 x 10-05 | 6.174 x 10-02 |

| 87 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 4 | Minimum | 4.329 x 10-12 | 1.829 x 10-01 |

| 88 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 4 | Product | 1.545 x 10-12 | 2.093 x 10-01 |

| 89 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 5 | Minimum | 2.511 x 10-07 | 2.033 x 10-01 |

| 90 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Crisp | 5 | Product | 2.510 x 10-07 | 2.398 x 10-01 |

| 91 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 3 | Minimum | 9.025 x 10-15 | 5.713 x 10-02 |

| 92 | 81 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 3 | Product | 8.604 x 10-15 | 6.371 x 10-02 |

| 93 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 4 | Minimum | 1.327 x 10-14 | 1.783 x 10-01 |

| 94 | 256 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 4 | Product | 2.253 x 10-14 | 1.936 x 10-01 |

| 95 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 5 | Minimum | 1.427 x 10-14 | 2.023 x 10-01 |

| 96 | 625 | Trapezoidal | Linear | 5 | Product | 8.294 x 10-15 | 2.257 x 10-01 |

| 97 | 81 | Gaussian | Crisp | 3 | Minimum | 5.132 x 10-10 | 4.202 x 10-03 |

| 98 | 81 | Gaussian | Crisp | 3 | Product | 1.453 x 10-11 | 1.680 x 10-02 |

| 99 | 256 | Gaussian | Crisp | 4 | Minimum | 2.169 x 10-11 | 1.340 x 10-02 |

| 100 | 256 | Gaussian | Crisp | 4 | Product | 1.657 x 10-12 | 1.482 x 10-01 |

| 101 | 625 | Gaussian | Crisp | 5 | Minimum | 3.195 x 10-11 | 6.921 x 10-02 |

| 102 | 625 | Gaussian | Crisp | 5 | Product | 1.295 x 10-12 | 2.443 x 10-01 |

| 103 | 81 | Gaussian | Linear | 3 | Minimum | 2.978 x 10-16 | 2.958 x 10-03 |

| 104 | 81 | Gaussian | Linear | 3 | Product | 1.556 x 10-14 | 1.383 x 10-02 |

| 105 | 256 | Gaussian | Linear | 4 | Minimum | 9.274 x 10-16 | 1.391 x 10-02 |

| 106 | 256 | Gaussian | Linear | 4 | Product | 1.584 x 10-14 | 6.808 x 10-02 |

| 107 | 625 | Gaussian | Linear | 5 | Minimum | 2.448 x 10-15 | 4.646 x 10-02 |

| 108 | 625 | Gaussian | Linear | 5 | Product | 1.723 x 10-14 | 1.536 x 10-01 |

|

Alternative hypothesis: H1: µD ≠ Test statistic: T0 = Rejection region (for two-tailed test): t0 < - or t0 > Reject H0 if the p-value is <α |

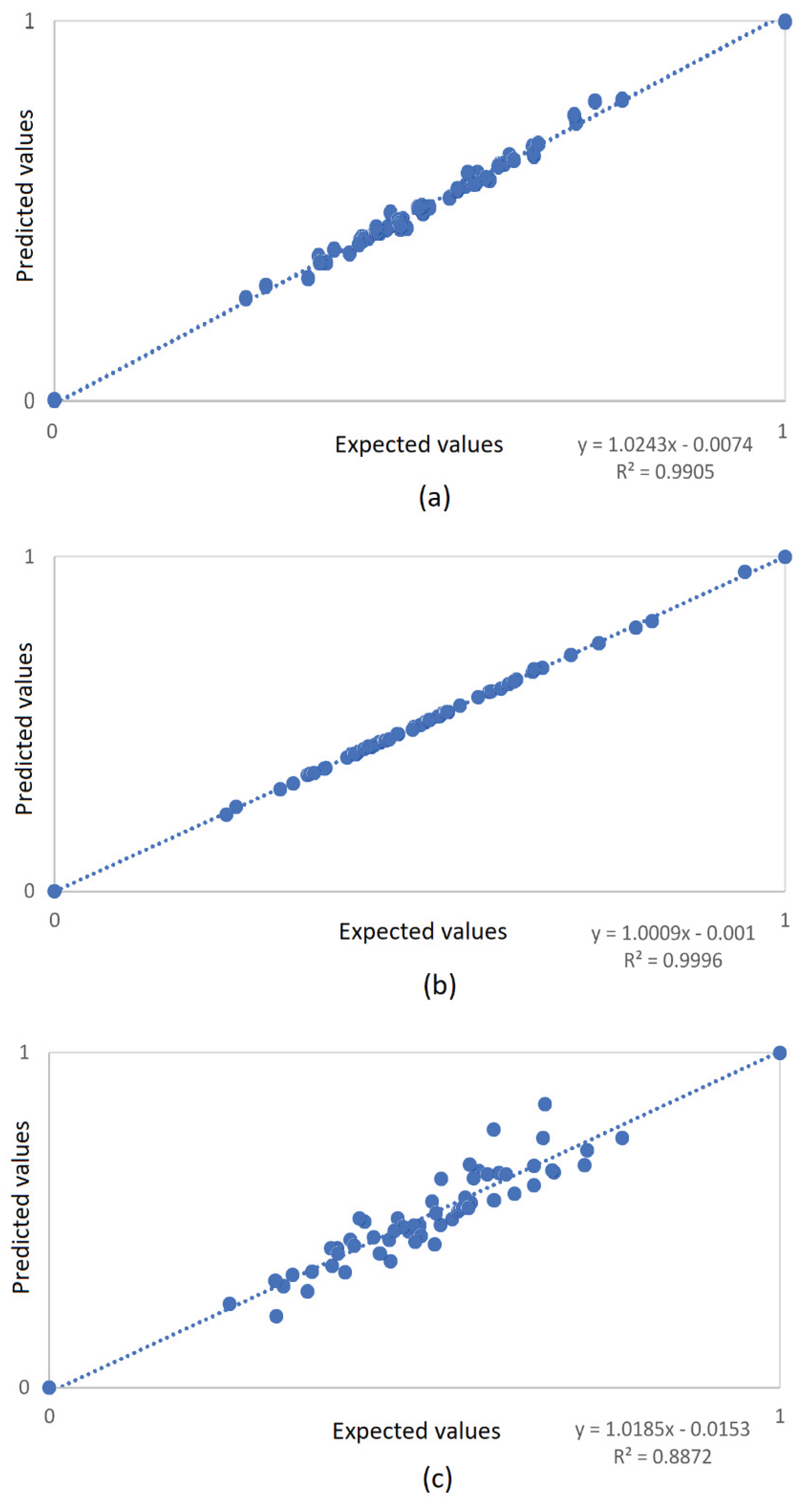

| Model | Sample set | Shapiro-Wilk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | p-value | |||

| ANFIS 1 | Expected values | 0.984 | 0.629 | |

| Predicted values | 0.975 | 0.252 | ||

| ANFIS 2 | Expected values | 0.965 | 0.087 | |

| Predicted values | 0.965 | 0.087 | ||

| ANFIS 3 | Expected values | 0.993 | 0.982 | |

| Predicted values | 0.993 | 0.976 | ||

| Model | Levene statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| ANFIS 1 | 0.122 | 0.728 |

| ANFIS 2 | 0.000 | 0.990 |

| ANFIS 3 | 0.568 | 0.453 |

| Model | Mean | Standard deviation | Mean standard error | T | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANFIS 1 | -0.00493 | 0.01473 | 0.0019 | -2.593 | 0.012 |

| ANFIS 2 | 0.00051 | 0.00313 | 0.0004 | 1.251 | 0.216 |

| ANFIS 3 | 0.00592 | 0.05455 | 0.00704 | 0.841 | 0.404 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).