Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Methods

Study Design

Sampling Technique

Data Collection

Community/Neighbourhood Definitions

Outcome Variable

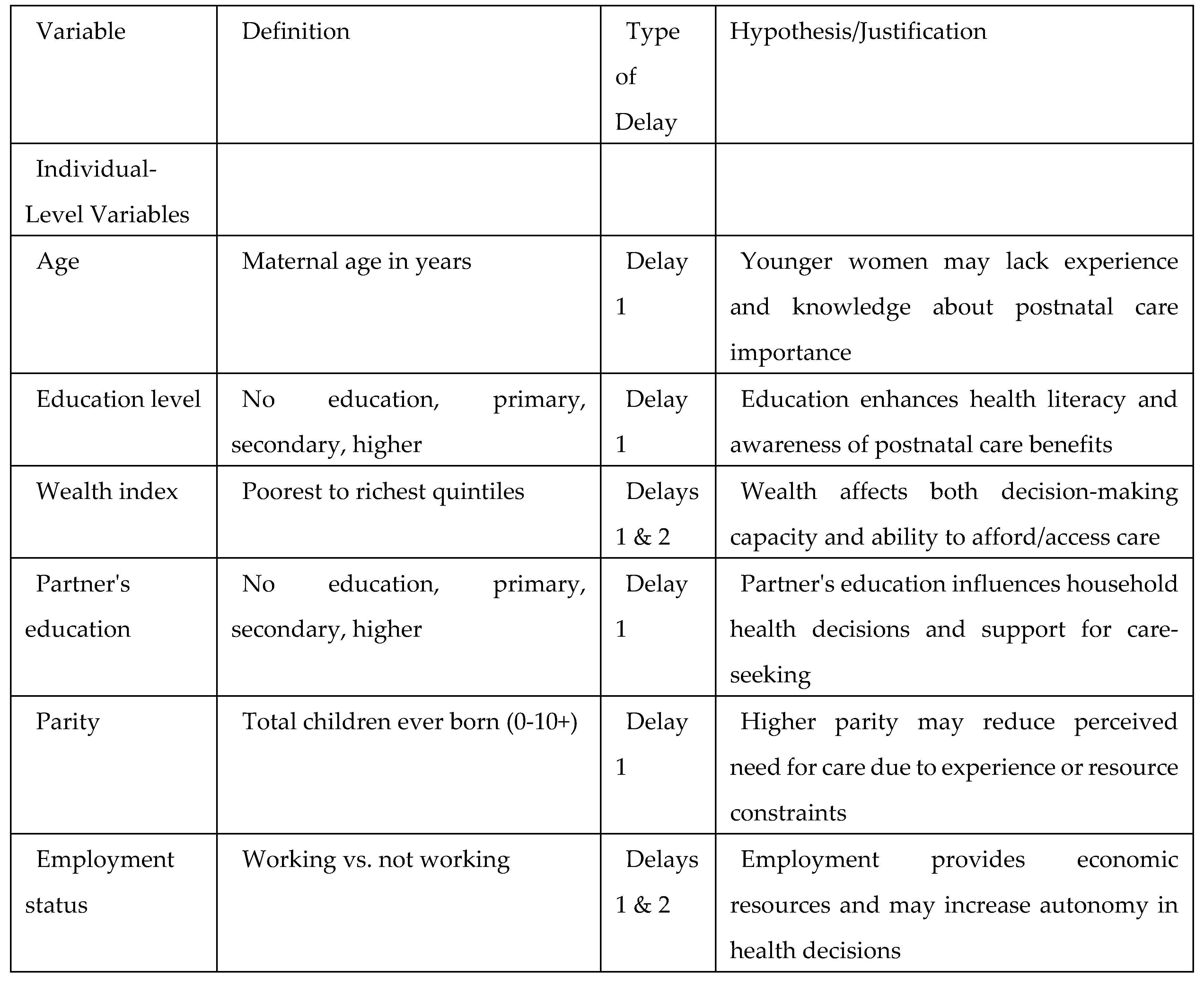

Explanatory Variables

Individual-Level Variables

Community-Level Variables

Country-Level Variables

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive Statistics

Modelling Approaches

Fixed Effects (Measures of Association)

Random Effects (Measures of Variation)

Model Fit and Specifications

Results

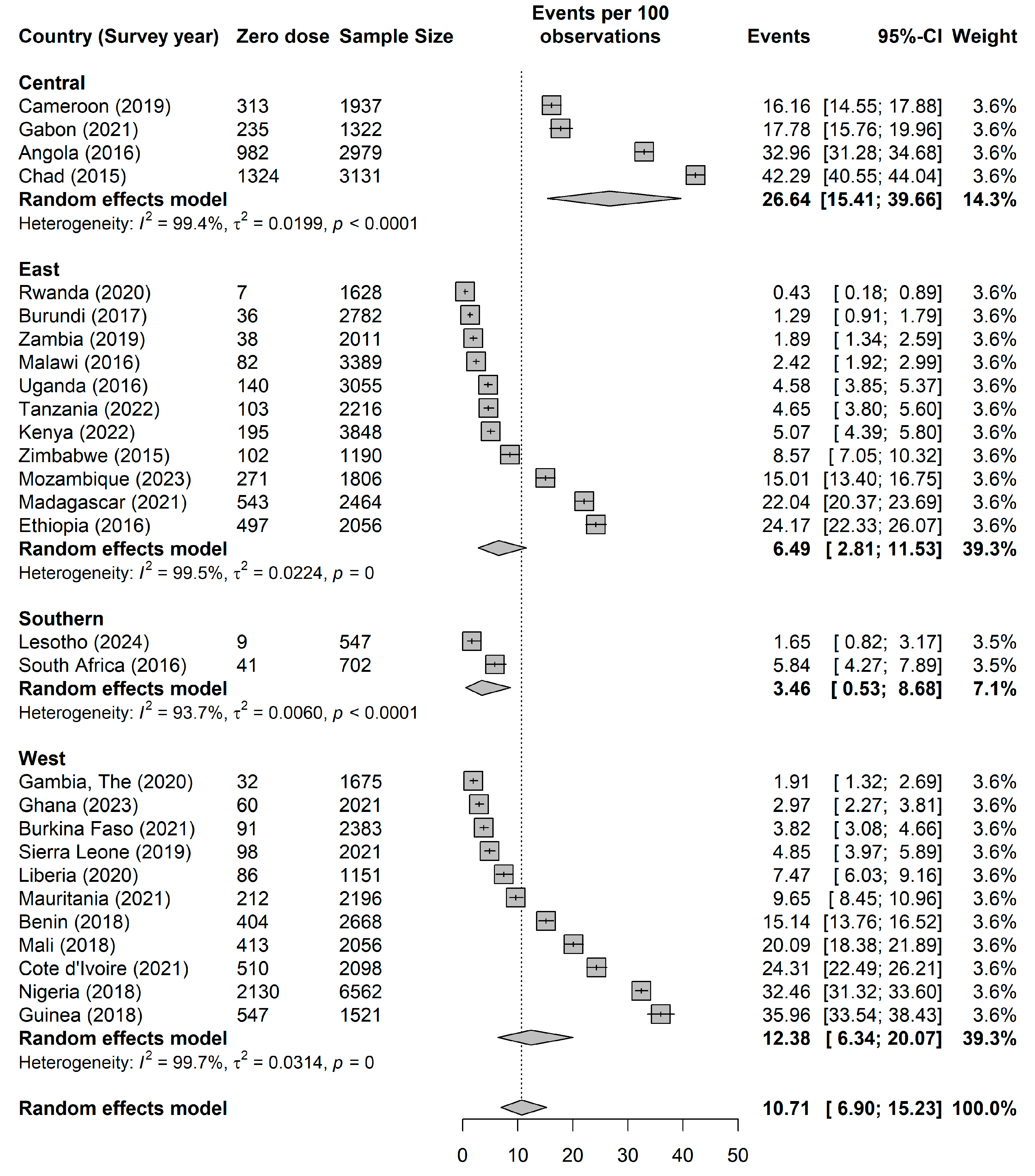

Sample Characteristics

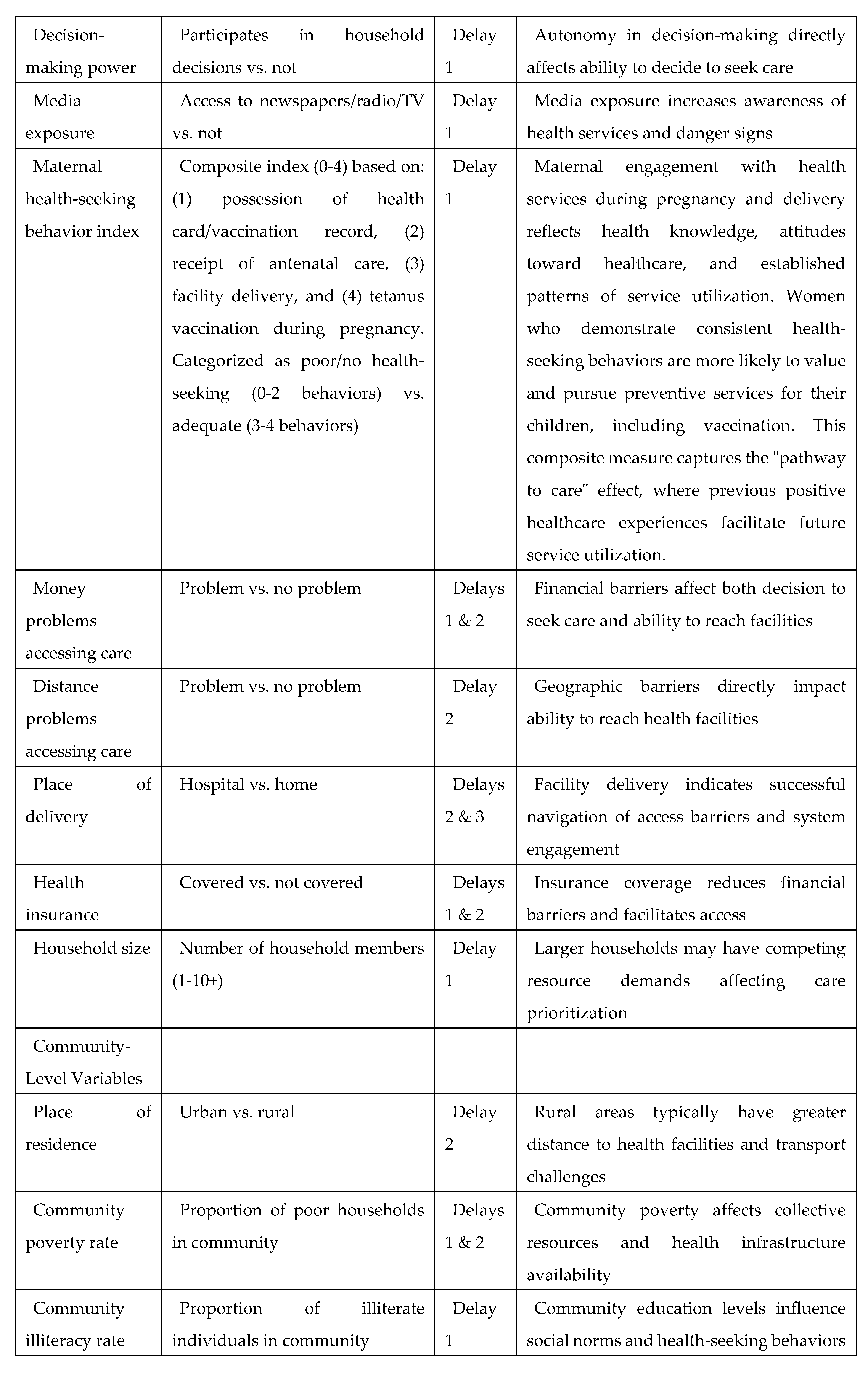

Variation in Zero-Dose Prevalence Across Sub-Saharan African Countries

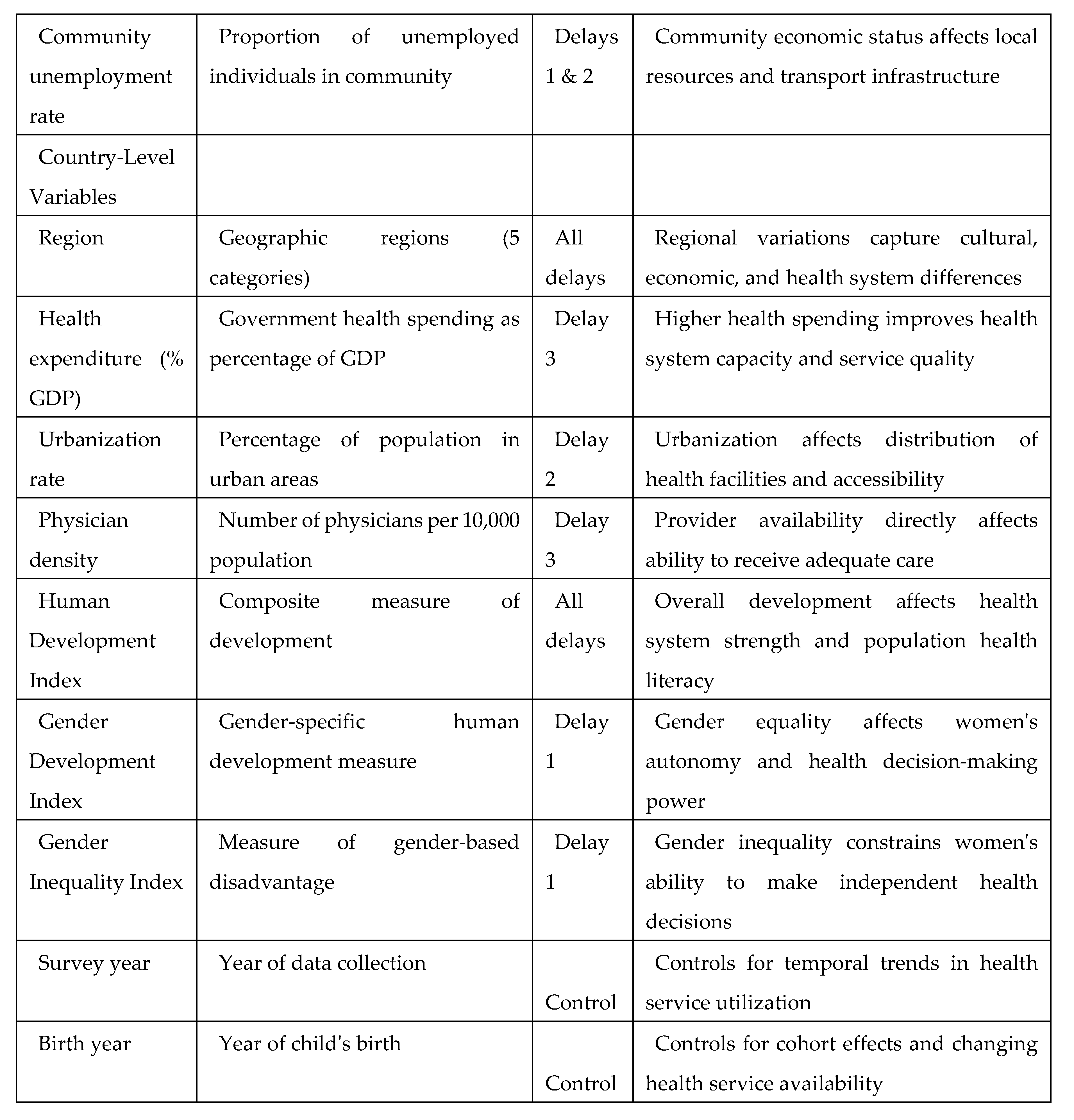

Measures of Association (Fixed Effects Model)

Measures of Variations (Random Effects)

Discussion

Main Findings

Comparison with Previous Studies

Implications for Policy and Future Research

Study Strengths and Limitations

Conclusions

Conflict of interests

Author Contributions

Funding

Appendix

References

- Andre FE, Booy R, Bock HL, Clemens J, Datta SK, John TJ, Lee BW, Lolekha S, Peltola H, Ruff TA et al: Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull World Health Organ 2008, 86(2):140-146.

- Gavi Alliance: Progress and challenges with achieving universal immunization coverage: 2019 estimates of immunization coverage. Geneva: Gavi; 2020.

- World Health Organization: Immunization Agenda 2030: a global strategy to leave no one behind. Geneva: WHO Press; 2020.

- UNICEF: The state of the world's children 2023: for every child, vaccination. New York: UNICEF; 2023.

- Causey K, Fullman N, Sorensen RJD, Galles NC, Zheng P, Aravkin A, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Martinez-Piedra R, Sodha SV, Velandia-Gonzalez MP et al: Estimating global and regional disruptions to routine childhood vaccine coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet 2021, 398(10299):522-534.

- Antai D: Faith and child survival: the role of religion in childhood immunization in Nigeria. J Biosoc Sci 2009, 41(1):57-76.

- Wiysonge CS, Uthman OA, Ndumbe PM, Hussey GD: Individual and contextual factors associated with low childhood immunisation coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One 2012, 7(5):e37905.

- Ntenda PAM, Chuang KY, Tiruneh FN, Chuang YC: Analysis of the effects of individual and community level factors on childhood immunization in Malawi. Vaccine 2017, 35(15):1907-1917.

- Thaddeus S, Maine D: Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 1994, 38(8):1091-1110.

- Masters SH, Burstein R, Amofah G, Abaogye P, Kumar S, Hanlon M: Travel time to maternity care and its effect on utilization in rural Ghana: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med 2013, 93:147-154.

- Gabrysch S, Campbell OM: Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009, 9:34.

- Diez-Roux AV: Multilevel analysis in public health research. Annu Rev Public Health 2000, 21(1):171-192.

- Subramanian SV, Jones K, Kaddour A, Krieger N: Revisiting Robinson: the perils of individualistic and ecologic fallacy. Int J Epidemiol 2009, 38(2):342-360; author reply 370-343.

- Restrepo-Mendez MC, Barros AJ, Wong KL, Johnson HL, Pariyo G, Franca GV, Wehrmeister FC, Victora CG: Inequalities in full immunization coverage: trends in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ 2016, 94(11):794-805B.

- Phillips DE, Dieleman JL, Lim SS, Shearer J: Determinants of effective vaccine coverage in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and interpretive synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res 2017, 17(1):681.

- Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, Subramanian SV: Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol 2012, 41(6):1602-1613.

- Aliaga A, Ren R: Optimal sample sizes for two-stage cluster sampling in demographic and health surveys. DHS Working Papers No. 30. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro; 2006.

- Kravdal Ø: A simulation-based assessment of the bias produced when using averages from small DHS clusters as contextual variables in multilevel models. Demographic Research 2006, 15(1):1-20.

- Bangura JB, Xiao S, Qiu D, Ouyang F, Chen L: Barriers to childhood immunization in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20(1):1108.

- Gram L, Soremekun S, ten Asbroek A, Manu A, O'Leary M, Hill Z, Danso S, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei S, Kirkwood BR: Socio-economic determinants and inequities in coverage and timeliness of early childhood immunisation in rural Ghana. Trop Med Int Health 2014, 19(7):802-811.

- Antai D: Gender inequities, relationship power, and childhood immunization uptake in Nigeria: a population-based cross-sectional study. Int J Infect Dis 2012, 16(2):e136-145.

- Adedokun ST, Uthman OA, Adekanmbi VT, Wiysonge CS: Incomplete childhood immunization in Nigeria: a multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors. BMC Public Health 2017, 17(1):236.

- Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A, Houweling TA, Fottrell E, Kuddus A, Lewycka S et al: Women's groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2013, 381(9879):1736-1746.

- Tokhi M, Comrie-Thomson L, Davis J, Portela A, Chersich M, Luchters S: Involving men to improve maternal and newborn health: A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. PLoS One 2018, 13(1):e0191620.

- Hanson K, Ranson MK, Oliveira-Cruz V, Mills A: Expanding access to priority health interventions: a framework for understanding the constraints to scaling-up. Journal of International Development 2003, 15(1):1-14.

- Heise L, Greene ME, Opper N, Stavropoulou M, Harper C, Nascimento M, Zewdie D, Gender Equality N, Health Steering C: Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet 2019, 393(10189):2440-2454.

- Goldstein H: Multilevel Statistical Models: Wiley; 2010.

- Miles M, Ryman TK, Dietz V, Zell E, Luman ET: Validity of vaccination cards and parental recall to estimate vaccination coverage: a systematic review of the literature. Vaccine 2013, 31(12):1560-1568.

- Cutts FT, Izurieta HS, Rhoda DA: Measuring coverage in MNCH: design, implementation, and interpretation challenges associated with tracking vaccination coverage using household surveys. PLoS Med 2013, 10(5):e1001404.

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD: On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol Methods 2002, 7(1):19-40.

| Zero dose | |||

| No | Yes | Total | |

| N | 49,991 (84.4%) | 9,220 (15.6%) | 59,211 (100.0%) |

| Survey year | 2019 [2017 2021] | 2018 [2016 2020] | 2018 [2016 2021] |

| Birth year | 2017 [2,015 2,020] | 2,017 [2,014 2,018] | 2,017 [2,015 2,019] |

| Maternal age | |||

| Young Adult | 16,578 (33.2%) | 3,220 (34.9%) | 19,797 (33.4%) |

| Adult | 30,177 (60.4%) | 5,324 (57.7%) | 35,501 (60.0%) |

| Middle-Aged /Older Adult | 3,236 (6.5%) | 676 (7.3%) | 3,912 (6.6%) |

| Maternal age | |||

| no education | 15,041 (30.1%) | 5,791 (62.8%) | 20,832 (35.2%) |

| primary | 17,442 (34.9%) | 2,079 (22.5%) | 19,520 (33.0%) |

| secondary | 14,708 (29.4%) | 1,197 (13.0%) | 15,905 (26.9%) |

| higher | 2,800 (5.6%) | 153 (1.7%) | 2,954 (5.0%) |

| Wealth index | |||

| poorest | 10,227 (20.5%) | 3,185 (34.5%) | 13,412 (22.7%) |

| poorer | 10,324 (20.7%) | 2,400 (26.0%) | 12,724 (21.5%) |

| middle | 10,215 (20.4%) | 1,705 (18.5%) | 11,920 (20.1%) |

| richer | 9,919 (19.8%) | 1,189 (12.9%) | 11,108 (18.8%) |

| richest | 9,305 (18.6%) | 741 (8.0%) | 10,046 (17.0%) |

| husband/partner's education level | |||

| no education | 12,094 (29.5%) | 4,627 (58.3%) | 16,721 (34.1%) |

| primary | 12,673 (30.9%) | 1,712 (21.6%) | 14,385 (29.4%) |

| secondary | 12,381 (30.1%) | 1,303 (16.4%) | 13,684 (27.9%) |

| higher | 3,917 (9.5%) | 288 (3.6%) | 4,205 (8.6%) |

| Antenatal visits | |||

| no visit | 3,233 (6.7%) | 3,638 (41.3%) | 6,871 (12.1%) |

| lessthan4 | 14,075 (29.3%) | 2,350 (26.7%) | 16,425 (28.9%) |

| 4 or more | 30,695 (63.9%) | 2,820 (32.0%) | 33,515 (59.0%) |

| Parity | |||

| 1 | 11,426 (22.9%) | 1,502 (16.3%) | 12,928 (21.8%) |

| 2 | 10,328 (20.7%) | 1,639 (17.8%) | 11,967 (20.2%) |

| 3 | 8,412 (16.8%) | 1,462 (15.9%) | 9,874 (16.7%) |

| 4 | 6,422 (12.8%) | 1,135 (12.3%) | 7,558 (12.8%) |

| 5 | 4,616 (9.2%) | 1,030 (11.2%) | 5,646 (9.5%) |

| 6 | 3,390 (6.8%) | 792 (8.6%) | 4,182 (7.1%) |

| 7 | 2,360 (4.7%) | 593 (6.4%) | 2,954 (5.0%) |

| 8 | 1,459 (2.9%) | 438 (4.8%) | 1,897 (3.2%) |

| 9 | 790 (1.6%) | 269 (2.9%) | 1,059 (1.8%) |

| 10 | 786 (1.6%) | 360 (3.9%) | 1,146 (1.9%) |

| Not working | |||

| 0 | 31,171 (62.4%) | 4,967 (53.9%) | 36,139 (61.0%) |

| 1 | 18,819 (37.6%) | 4,252 (46.1%) | 23,072 (39.0%) |

| No decision-making power | |||

| 0 | 32,902 (65.8%) | 5,022 (54.5%) | 37,924 (64.0%) |

| 1 | 17,089 (34.2%) | 4,197 (45.5%) | 21,286 (36.0%) |

| nomedia | |||

| 0 | 33,253 (66.5%) | 3,890 (42.2%) | 37,143 (62.7%) |

| 1 | 16,738 (33.5%) | 5,330 (57.8%) | 22,068 (37.3%) |

| No media access | |||

| 0 | 623 (1.2%) | 2,961 (32.1%) | 3,585 (6.1%) |

| 1 | 1,453 (2.9%) | 933 (10.1%) | 2,386 (4.0%) |

| 2 | 4,712 (9.4%) | 2,152 (23.3%) | 6,864 (11.6%) |

| 3 | 15,902 (31.8%) | 2,008 (21.8%) | 17,911 (30.2%) |

| 4 | 27,300 (54.6%) | 1,165 (12.6%) | 28,465 (48.1%) |

| Household size | |||

| 1 | 89 (0.2%) | 14 (0.2%) | 104 (0.2%) |

| 2 | 856 (1.7%) | 144 (1.6%) | 1,000 (1.7%) |

| 3 | 6,312 (12.6%) | 903 (9.8%) | 7,215 (12.2%) |

| 4 | 7,987 (16.0%) | 1,288 (14.0%) | 9,275 (15.7%) |

| 5 | 7,859 (15.7%) | 1,440 (15.6%) | 9,298 (15.7%) |

| 6 | 7,163 (14.3%) | 1,186 (12.9%) | 8,349 (14.1%) |

| 7 | 5,434 (10.9%) | 1,022 (11.1%) | 6,456 (10.9%) |

| 8 | 3,990 (8.0%) | 852 (9.2%) | 4,842 (8.2%) |

| 9 | 2,718 (5.4%) | 615 (6.7%) | 3,333 (5.6%) |

| 10 | 7,583 (15.2%) | 1,756 (19.0%) | 9,339 (15.8%) |

| Money problem accessing care | |||

| No | 26,005 (52.0%) | 3,927 (42.6%) | 29,932 (50.6%) |

| Yes | 23,986 (48.0%) | 5,293 (57.4%) | 29,278 (49.4%) |

| Distance problem accessing care | |||

| No | 32,843 (65.7%) | 5,024 (54.5%) | 37,867 (64.0%) |

| Yes | 17,148 (34.3%) | 4,195 (45.5%) | 21,344 (36.0%) |

| Health insurance | |||

| No | 10,294 (20.6%) | 1,258 (13.6%) | 11,552 (19.5%) |

| Yes | 39,697 (79.4%) | 7,962 (86.4%) | 47,658 (80.5%) |

| Place of resident | |||

| Urban | 17,628 (35.3%) | 2,154 (23.4%) | 19,782 (33.4%) |

| Rural | 32,362 (64.7%) | 7,066 (76.6%) | 39,429 (66.6%) |

| Community poverty rate | 20.9 (26.6) | 32.6 (32.2) | 22.7 (27.8) |

| Community illiteracy rate | 32.2 (31.4) | 59.6 (33.7) | 36.5 (33.2) |

| Community unemployment rate | 30.2 (27.0) | 30.8 (31.3) | 30.3 (27.8) |

| Gross domestic product | 3967.3 (3199.2) | 4360.7 (3275.6) | 4028.6 (3214.4) |

| Percentage health expenditure | 5.0 (1.9) | 4.3 (1.3) | 4.9 (1.8) |

| Human development index | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) |

| Gender Development Index | 0.9 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.0) |

| Gender Inequality Index | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

| OR (95% CrI) | OR (95% CrI) | OR (95% CrI) | OR (95% CrI) | OR (95% CrI) | |

| Measures of associations (Fixed Effects Model) | |||||

| Individual -level factors | |||||

| Survey year | 0.95 (0.95-0.95) | 0.95 (0.95-0.95) | |||

| Birth year | 0.97 (0.97-0.97) | 0.97 (0.97-0.97) | |||

| Maternal age | |||||

| Young adult | 1.73 (1.42-2.04) | 1.59 (1.34-1.89) | |||

| Adult | 1.25 (1.07-1.44) | 1.20 (1.05-1.37) | |||

| Middle-Age/Older Adult | |||||

| Education | |||||

| No education | 2.39 (1.94-2.87) | 1.84 (1.36-2.81) | |||

| Primary | 1.53 (1.24-1.84) | 1.40 (1.05-2.06) | |||

| Secondary | 1.24 (0.99-1.50) | 1.17 (0.89-1.67) | |||

| Tertiary | |||||

| Wealth | |||||

| Poorest | 1.33 (1.13-1.57) | 1.14 (0.95-1.34) | |||

| Poorer | 1.19 (1.01-1.41) | 1.11 (0.92-1.30) | |||

| Middle | 1.18 (1.01-1.38) | 1.11 (0.94-1.28) | |||

| Richer | 0.96 (0.82-1.12) | 0.93 (0.79-1.07) | |||

| Richest | |||||

| Partner Education | |||||

| No education | 1.56 (1.28-1.94) | 1.44 (1.17-1.72) | |||

| Primary | 1.21 (1.00-1.47) | 1.27 (1.02-1.54) | |||

| Secondary | 1.04 (0.87-1.27) | 1.09 (0.90-1.29) | |||

| Tertiary | |||||

| Parity | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | |||

| Not working | 1.26 (1.16-1.37) | 1.13 (1.04-1.23) | |||

| No decision-making power | 1.33 (1.22-1.45) | 1.31 (1.21-1.43) | |||

| No media access | 1.32 (1.21-1.44) | 1.28 (1.18-1.39) | |||

| Household size | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | |||

| Money problem accessing care | 1.03 (0.94-1.13) | 1.05 (0.96-1.15) | |||

| Distance problem accessing care | 1.10 (1.01-1.20) | 1.07 (0.98-1.17) | |||

| Money problem accessing care | 2.09 (1.91-2.28) | 1.98 (1.81-2.17) | |||

| No health insurance | 1.09 (0.86-1.30) | 1.11 (0.94-1.27) | |||

| Poor / No maternal health seeking | 15.90 (13.93-18.09) | 15.21 (13.28-17.35) | |||

| Community -level factors | |||||

| Rural resident | 1.22 (1.11-1.35) | 0.91 (0.80-1.01) | |||

| Community poverty rate | 1.07 (1.06-1.09) | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | |||

| Community illiteracy rate | 1.31 (1.28-1.33) | 1.11 (1.08-1.14) | |||

| Community unemployment rate | 1.09 (1.07-1.12) | 1.06 (1.04-1.09) | |||

| Societal -level factors | |||||

| Gross domestic product | 0.26 (0.17-0.36) | 1.26 (0.53-2.21) | |||

| Percentage health expenditure | 1.68 (1.16-2.84) | 3.45 (1.85-5.72) | |||

| Human development index | 1.81 (0.97-3.17) | 0.82 (0.42-1.82) | |||

| Gender Development Index | 7.26 (3.91-13.57) | 1.91 (1.11-3.17) | |||

| Gender Inequality Index | 1.67 (1.02-2.88) | 0.87 (0.39-1.50) | |||

| Measures of variations (random effects) | |||||

| Country-level | |||||

| Variance (95% CrI) | 2.81 (1.63-4.72) | 1.52 (0.87-2.64) | 2.04 (1.18-3.56) | 1.90 (1.05-3.30) | 1.08 (0.59-1.91) |

| VPC (%) | 32.4 (22.3-43.7) | 25.1 (16.5-36.1) | 29.5 (19.8-41.5) | 24.5 (16.5-35.2) | 19.1 (11.6-28.8) |

| MOR (95% CrI) | 4.95 (3.38-7.94) | 3.24 (2.43-4.71) | 3.91 (2.82-6.05) | 3.72 (2.66-5.65) | 2.70 (2.08-3.74) |

| Explained variance (%) | reference | 46.0 (44.1-46.8) | 27.4 (24.6-27.8) | 32.5 (30.1-35.7) | 61.6 (59.5-64.0) |

| Community-level | |||||

| Variance (95% CrI) | 2.59 (2.40-2.79) | 1.25 (1.10-1.39) | 1.59 (1.46-1.73) | 2.57 (2.38-2.78) | 1.30 (1.17-1.42) |

| VPC (%) | 62.1 (55.0-69.5) | 45.7 (37.4-55.0) | 52.5 (44.5-61.6) | 57.6 (51.0-64.9) | 42.0 (34.7-50.3) |

| MOR (95% CrI) | 4.64 (4.38-4.92) | 2.91 (2.72-3.08) | 3.33 (3.17-3.51) | 4.62 (4.36-4.91) | 2.97 (2.80-3.12) |

| Explained variance (%) | reference | 51.7 (50.2-54.2) | 38.5 (38.0-39.1) | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 49.7 (49.1-51.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).