Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

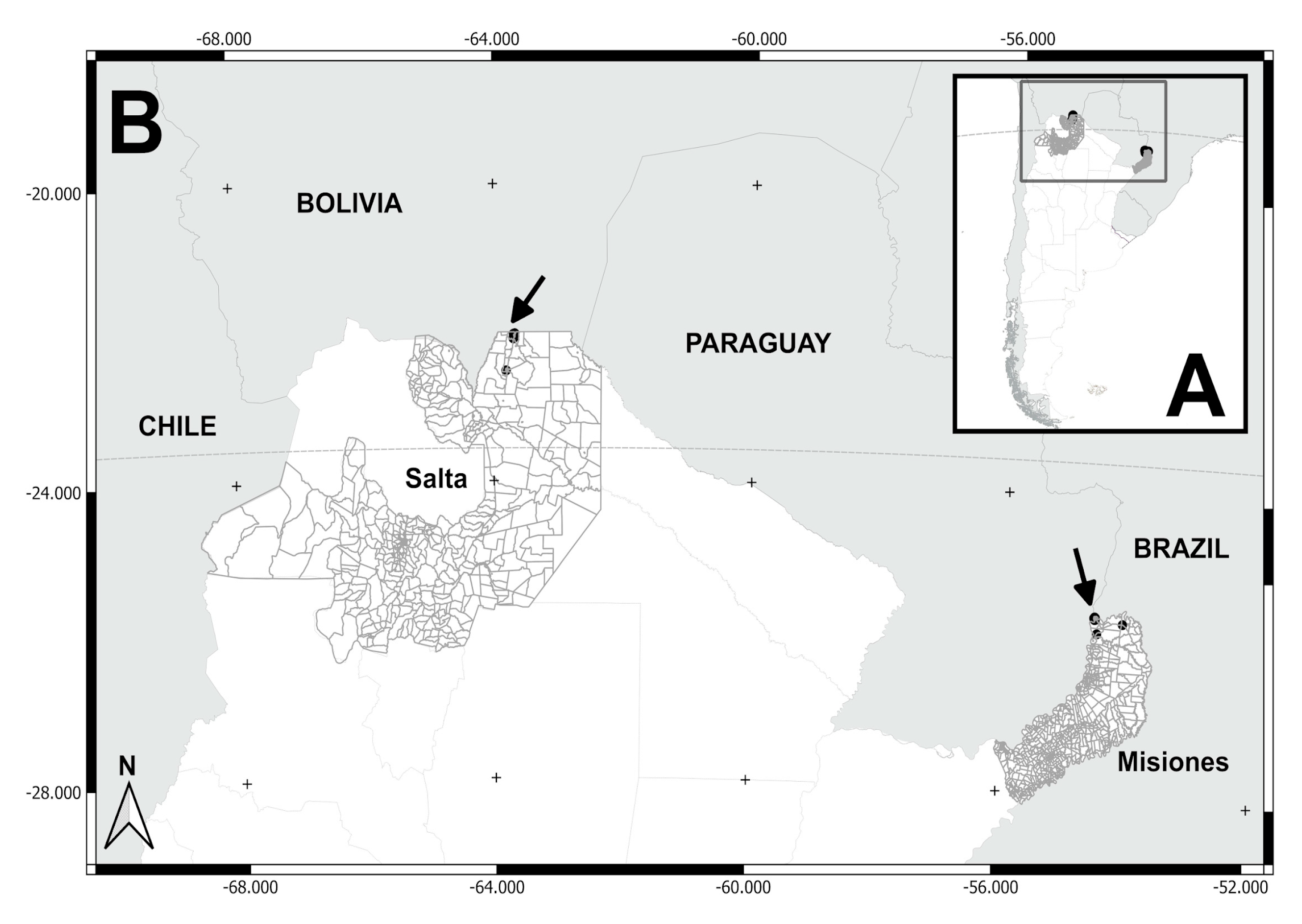

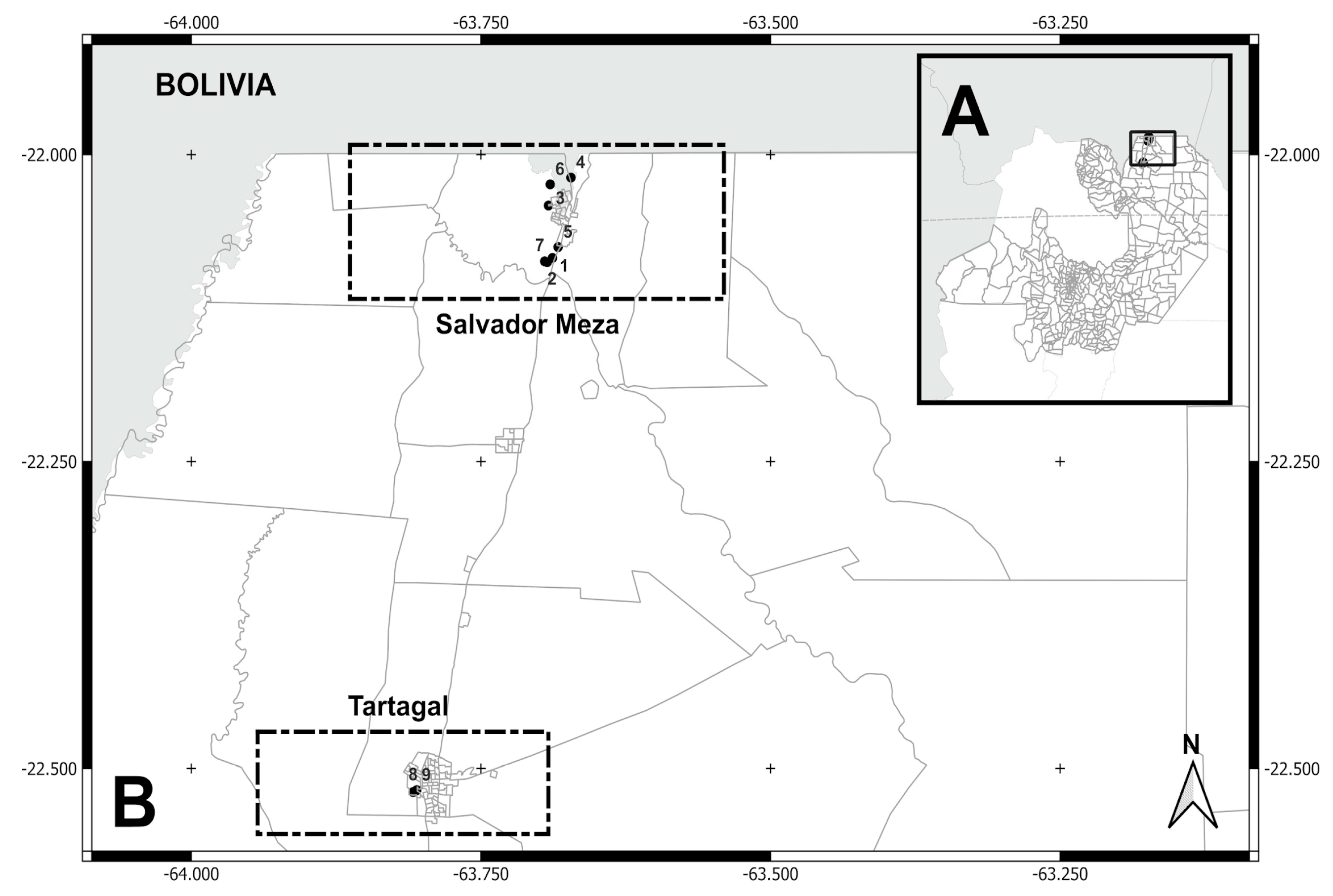

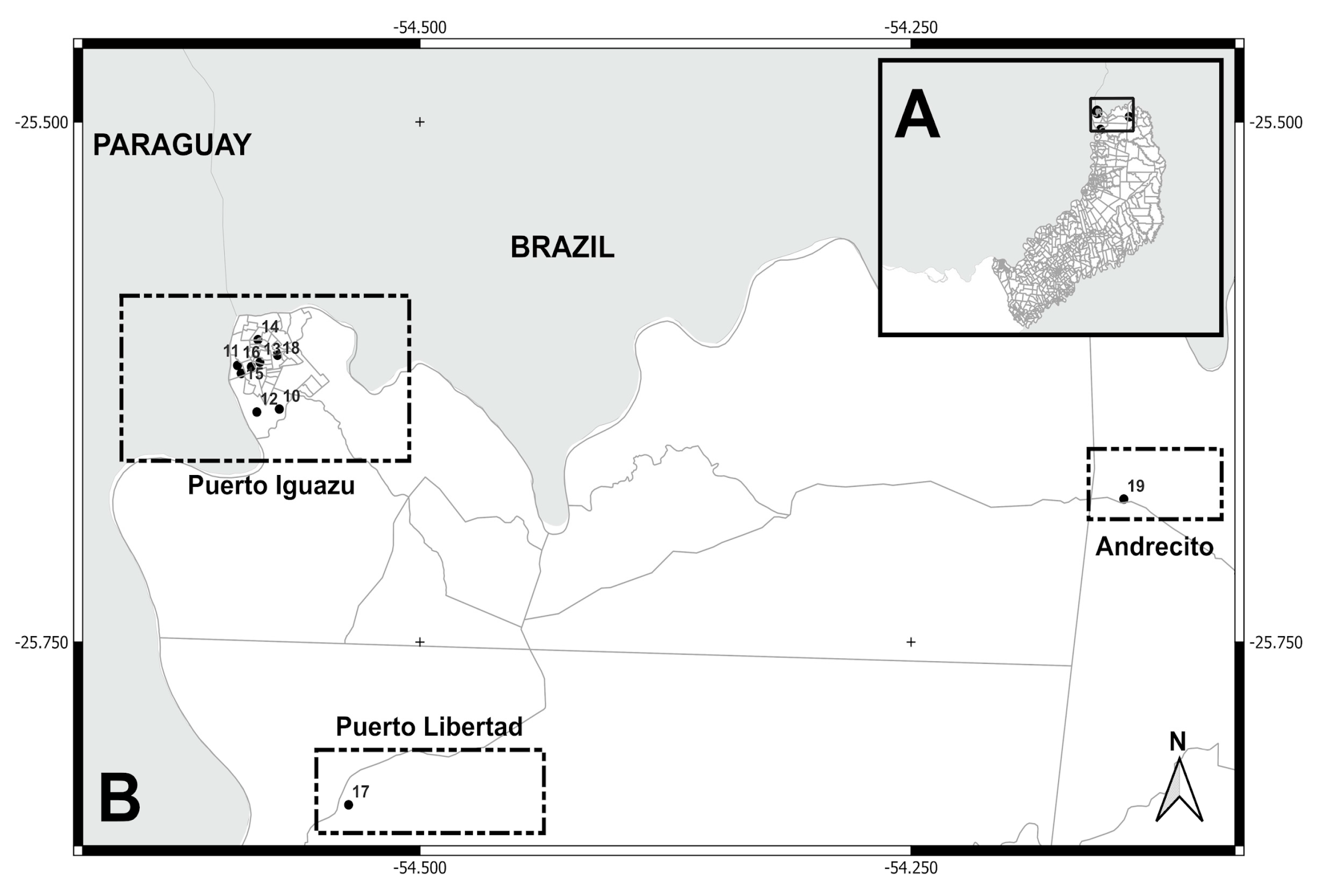

2.1. Study area

2.2. Epidemiological Surveillance

2.3. Entomological Surveillance

2.4. Ethics Statement

2.5. Malaria Diagnosis

2.5.1. Routine Microscopy

2.5.2. DNA Extraction and Cyt b Gene PCR Amplification

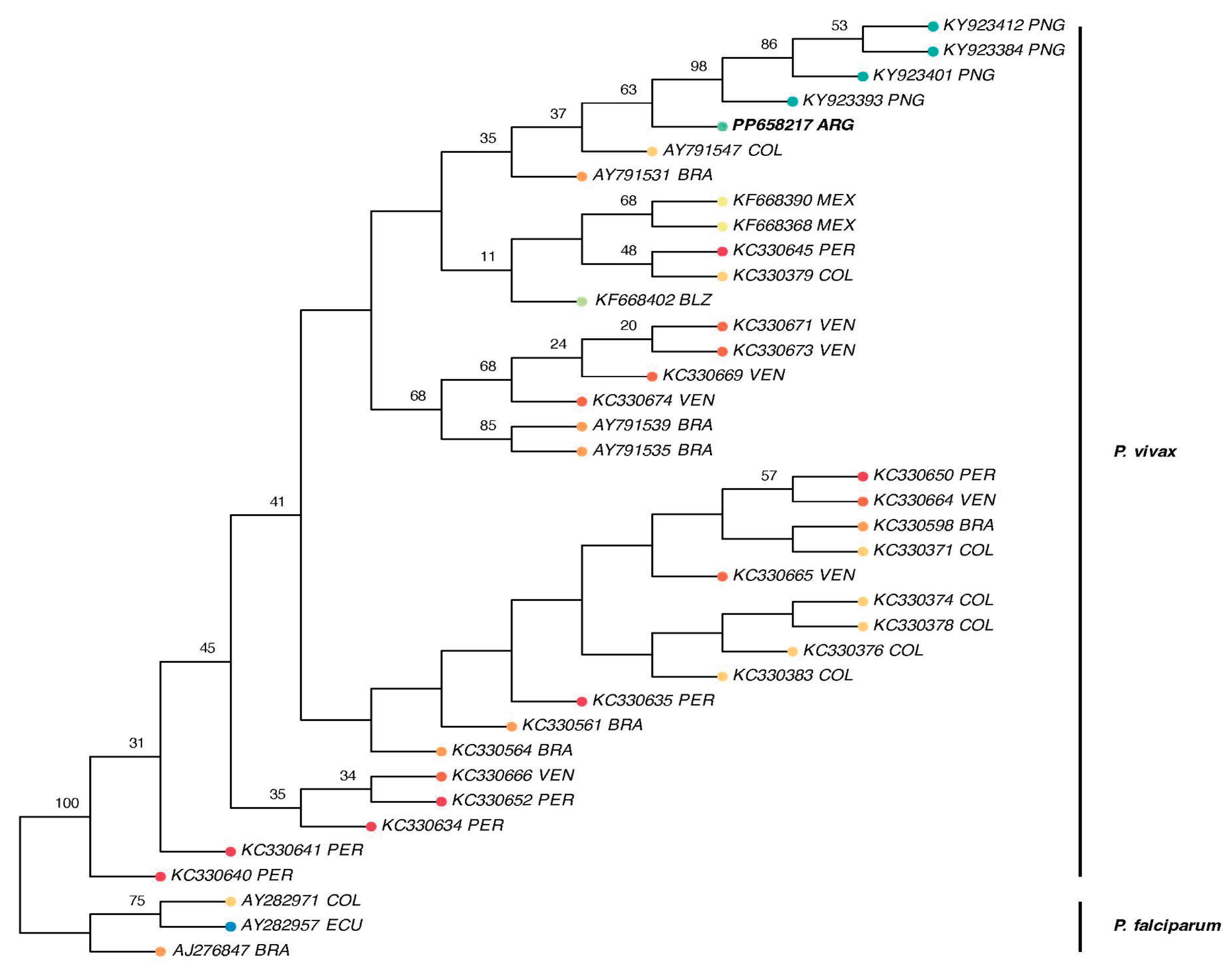

2.5.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Circulation of Asymptomatic Plasmodium Vivax

3.2. Phylogenetic Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Battle, K.E.; Lucas, T.C.D.; Nguyen, M.; Howes, R.E.; Nandi, A.K.; Twohig, K.A.; et al. Mapping the global endemicity and clinical burden of Plasmodium vivax, 2000–17: A spatial and temporal modeling study. Lancet 2019, 394, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Malaria Report 2022; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–372. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Countries and territories certified malaria-free by WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/elimination/countries-and-territories-certified-malaria-free-by-who (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Rougeron, V.; Daron, J.; Fontaine, M.C.; Prugnolle, F. Evolutionary history of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium simium in the Americas. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.T.; Valdivia, H.O.; de Oliveira, T.C.; Alves, J.M.P.; Duarte, A.M.R.C.; Cerutti-Junior, C.; et al. Human migration and the spread of malaria parasites to the New World. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousema, T.; Drakeley, C. Epidemiology and infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax gametocytes in relation to malaria control and elimination. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 377–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.C.S.; Vinetz, J.M. Asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax parasitaemia in the low-transmission setting: The role for a population-based transmission-blocking vaccine for malaria elimination. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, G.G.; Costa, P.A.C.; Araujo, M.d.S.; Gomes, G.R.; Carvalho, A.F.; Figueiredo, M.M.; Pereira, D.B.; Tada, M.S.; Medeiros, J.F.; Soares, I.D.S.; Carvalho, L.H.; Kano, F.S.; Castro, M.D.C.; Vinetz, J.M.; Golenbock, T.; Antonelli, L.R.D.V.; Gazzinelli, R.T. Asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax malaria in the Brazilian Amazon: Submicroscopic parasitemic blood infects Nyssorhynchus darlingi. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, C.; Sturrock, H.J.W.; Hsiang, M.S.; Liu, J.; Phillips, A.A.; Hwang, J.; et al. The changing epidemiology of malaria elimination: New strategies for new challenges. Lancet 2013, 382, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousema, T.; Okell, L.; Felger, I.; Drakeley, C. Asymptomatic malaria infections: Detectability, transmissibility and public health relevance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recht, J.; Siqueira, A.M.; Monteiro, W.M.; Herrera, S.M.; Herrera, S.; Lacerda, M.V.G. Malaria in Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Venezuela: Current challenges in malaria control and elimination. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.P.; Gil, L.H.S.; Marrelli, M.T.; Ribolla, P.E.M.; Camargo, E.P.; Pereira DaSilva, L.H. Asymptomatic carriers of Plasmodium spp. as infection source for malaria vector mosquitoes in the Brazilian Amazon. J. Med. Entomol. 2005, 42, 777–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okell, L.C.; Bousema, T.; Griffin, J.T.; Ouedraogo, A.L.; Ghani, A.C.; Drakeley, C.J. Factors determining the occurrence of submicroscopic malaria infections and their relevance for control. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; von Seidlein, L.; Nguyen, T.V.; Truong, P.N.; Hung, S.D.; Pham, H.T.; et al. The persistence and oscillations of submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infections over time in Vietnam: An open cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidenberg, M. The Path to Malaria Elimination in Argentina; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrucken, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, E.; Coello-Peralta, R.D.; Cedeño-Reyes, P.; Valle-Mieles, E.M.; Duque, P.L.; Zaidenberg, M.O.; Madariaga, H.; Navarro, J.C.; Dantur-Juri, M.J.; Castro, M.C. Patterns and Determinants of Imported Malaria near the Argentina–Bolivia Border, 1977–2009. Pathogens 2025, 14, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud de la Nación. Eliminación del Paludismo en Argentina 2018; Ministerio de Salud de la Nación: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018; pp. 1–148. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics and Censuses Argentina. Population and Housing Census 2010. Available online: https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Institucional-Indec-QuienesSomosEng (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Prugnolle, F.; Ollomo, B.; Durand, P.; Yalcindag, E.; Arnathau, C.; Elguero, E.; et al. African monkeys are infected by Plasmodium falciparum nonhuman primate-specific strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11948–11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, T.L.; Busby, B.; Ye, J. Reply to the paper: Misunderstood parameters of NCBI BLAST impacts the correctness of bioinformatics workflows. Bioinformatics 2018, 35, 2699–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 2004, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.K.; Ly-Trong, N.; Ren, H.; Baños, H.; Roger, A.J.; Susko, E.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE 3: Phylogenomic inference software using complex evolutionary models. Available online: https://doi.org/10.32942/X2P62N (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 july 2025).

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouri, T.; Izquierdo-Carrasco, F.; Darriba, D.; Aberer, A.J.; Nguyen, L.T.; Minh, B.Q.; Stamatakis, A. The phylogenetic likelihood library. Syst. Biol. 2015, 64, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemoine, F.; Domelevo Entfellner, J.B.; Wilkinson, E.; Correia, D.; Dávila Felipe, M.; De Oliveira, T.; Gascuel, O. Renewing Felsenstein’s phylogenetic bootstrap in the era of big data. Nature 2018, 556, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; et al. Predicting the risk of malaria re-introduction in countries certified malaria-free: A systematic review. Malar. J. 2023, 22, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunasena, V.M.; Marasinghe, M.; Koo, C.; Amarasinghe, S.; Senaratne, A.S.; Hasantha, R.; et al. The first introduced malaria case reported from Sri Lanka after elimination: Implications for preventing the re-introduction of malaria in recently eliminated countries. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines on Prevention of the Reintroduction of Malaria; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, W.; Schmidt, G. Mapping the potential temperature dependent tertian malaria transmission within the ecoregions of Lower Saxony (Germany). Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 298, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.W.; Wang, L.P.; Liang, S.; Liu, Y.X.; Tong, S.L.; Wang, J.J.; et al. Change in rainfall drives malaria re-emergence in Anhui Province, China. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar, A.C.; Manguin, S.; Santana, M.S.; Zaidenberg, M.; Lanfri, M.; Dantur Juri, M.J. The effect of land use change in the abundance of malaria cases in Northern Argentina. 67th Annual Meeting American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, New Orleans, USA, 28 October 2018.

- Delon, F.; Mayet, A.; Thellier, M.; Kendjo, E.; Michel, R.; Ollivier, L.; et al. Assessment of the French national health insurance information system as a tool for epidemiological surveillance of malaria. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, S.M.I.; Amarasekara, S.; Wickremasinghe, R.; Fernando, D.; Udagama, P. Prevention of re-establishment of malaria: Historical perspective and future prospects. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejarano, J.F.R. Distribución en altura del género Anopheles y del paludismo en la República Argentina. Rev. Sanit. Milit. Argent. 1956, 55, 4–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dantur Juri, M.J.; Moreno, M.; Prado Izaguirre, M.J.; Navarro, J.C.; Zaidenberg, M.O.; Almirón, W.R.; Claps, G.L.; Conn, J.E. Demographic history and population structure of Anopheles pseudopunctipennis in Argentina based on the mitochondrial COI gene. Parasit. Vectors 2014, 7, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmawardena, P.; Premaratne, R.; Wickremasinghe, R.; Mendis, K.; Fernando, D. Epidemiological profile of imported malaria cases in the prevention of reestablishment phase in Sri Lanka. Pathog. Glob. Health 2022, 116, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coura, J.R.; Suárez-Mutis, M.; Ladeia-Andrade, S. A new challenge for malaria control in Brazil: Asymptomatic Plasmodium infection—A Review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2006, 101, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.B.; Calil, P.R.; Rodrigues, P.T.; Tonini, J.; Fontoura, P.S.; Sato, P.M.; Ferreira, M.U. Clinically silent Plasmodium vivax infections in native Amazonians of northwestern Brazil: Acquired immunity or low parasite virulence? Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2022, 117, e220175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shretta, R.; Avancena, A.L.; Hatefi, A. The economics of malaria control and elimination: A systematic review. Malar. J. 2016, 15, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Prevention of Re-establishment of Malaria Transmission: Global Guidance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–81. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Neighborhoods, settlements / Localities | Biogeographical provinces | Latitude/longitude coordinates | Dates of collections | N samples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salta province | ||||||

| 1 | La Bendición / Salvador Mazza | Yungas ж | -22.08412, -63.68822 | November 2016 | 11 | |

| 2 | El Arenal / Salvador Mazza | -22.08693, -63.69492 | December 2013 | 3 | ||

| 3 | Nueva Esperanza/ Salvador Mazza | -22.04147, -63.69166 | December 2013 / ж 2015 | 9 | ||

| 4 | La Playa / Salvador Mazza | -22.01872, -63.67224 | December 2015 | 3 | ||

| 5 | El Obraje / Salvador Mazza | -22.07531, -63.68332 | December 2015 | 1 | ||

| 6 | El Chorro / Salvador Mazza | -22.02420, -63.69015 | December 2015 | 3 | ||

| 7 | Barrio Arenales / Salvador Mazza | -22.08756, -63.69273 | December 2015 | 11 | ||

| 8 | Barrio Ferroviario / Tartagal | -22.51909, -63.80849 | November 2016 | 1 | ||

| 9 | Barrio Centro / Tartagal | -22.51753, -63.80538 | November 2016 | 1 | ||

| ж Misiones province | ||||||

| 10 | 2000 Hectáreas / Puerto Iguazú | Paranaense ж | -25.63801, -54.57160 | August 2017 | 16 | |

| 11 | Ribera del Paraná / P. Iguazú | -25.61703, -54.59288 | October 2017 | 5 | ||

| 12 | Barrio Alto Paraná / P. Iguazú | -25.63943, -54.58304 | October 2017 | 2 | ||

| 13 | Barrio Belén / P. Iguazú | -25.61548, -54.58147 | October 2017 | 3 | ||

| 14 | Barrio Obrero / P. Iguazú | -25.60469, -54.58248 | October 2017 | 1 | ||

| 15 | Barrio Santa Rosa / P. Iguazú | -25.62087, -54.59100 | October 2017 | 6 | ||

| 16 | Barrio San Lucas / P. Iguazú | -25.61771, -54.58587 | October 2017 | 3 | ||

| 17 | Barrio San Cayetano / P. Libertad | -25.82811, -54.53633 | August 2017 | 4 | ||

| 18 | Barrio Selva 2 / Andrecito | -25.61210, -54.57252 | August 2017 | 3 | ||

| 19 | Caburé-i | -25.68127, -54.14172 | November 2017 | 6 | ||

| Country | Accession Numbers |

|---|---|

| Argentina | PP658217 |

| Belize | KF668402 |

| Brazil | AJ276847, AY791531, AY791535, AY791539, KC330561, KC330564, KC330598 |

| Colombia | AY282971, AY791547, KC330371, KC330378, KC330383, KC330374, KC330376, KC330379 |

| Ecuador | AY282957 |

| Mexico | KF668390, KF668368 |

| Papua New Guinea | KY923393, KY923401, KY923412, KY923384 |

| Peru | KC330635, KC330650, KC330652, KC330641, KC330640, KC330634, KC330645 |

| Venezuela | KC330665, KC330664, KC330666, KC330669, KC330671, KC330674, KC330673 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).