3.1. Load Redistribution Depending on Load Combination

A common and recommended approach for considering the influence of settlements on the structural behavior is to first determine the settlement distribution using an appropriate geotechnical program that accounts for the complex, nonlinear behavior of soil. The resulting settlements are then imposed on the structural foundation elements. This prescribed deformation leads to a redistribution of internal forces within the structure—typically from the areas with larger settlements (often the center) toward the less affected zones (usually the edges).

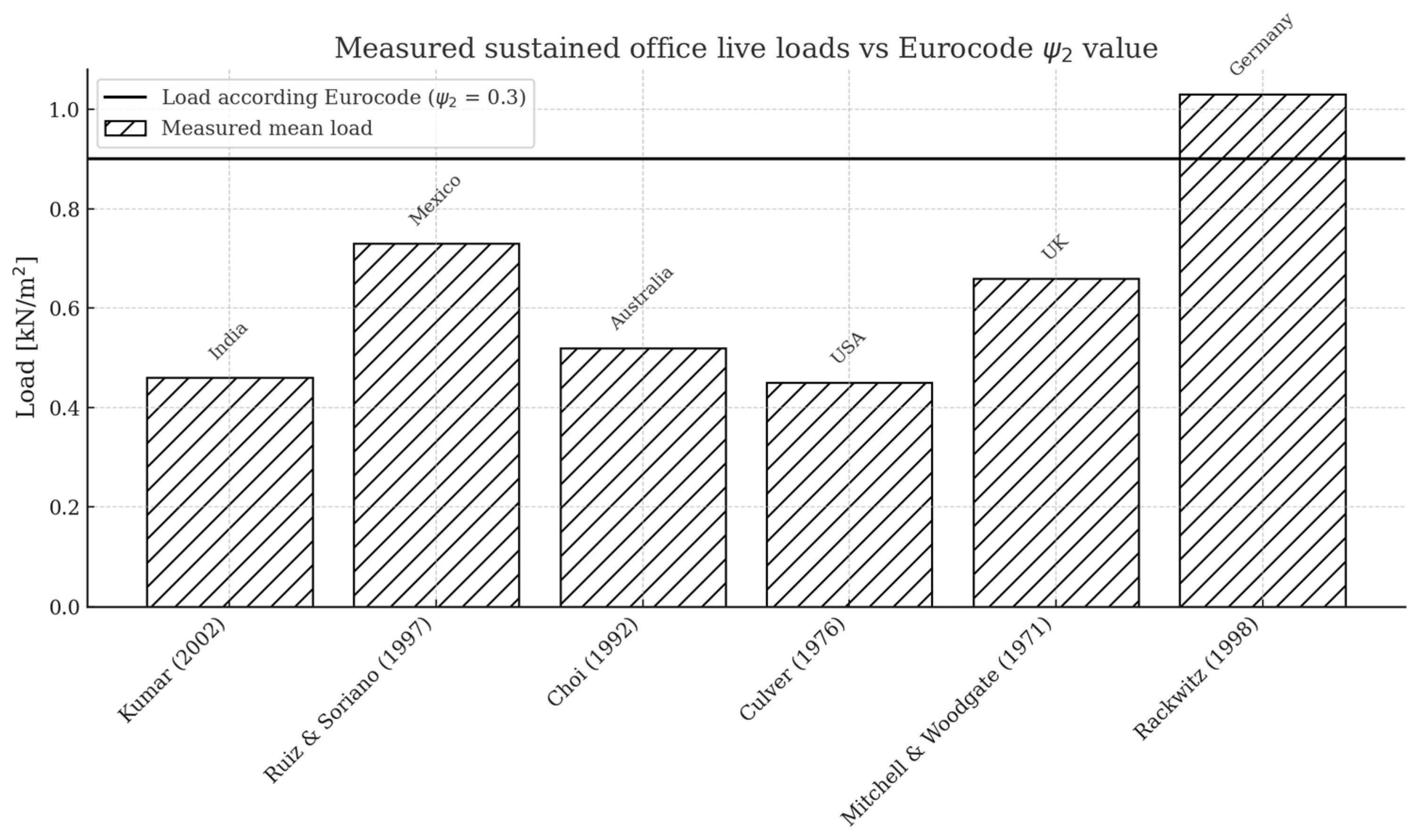

In addition to other important factors of soil-structure interaction—such as the structural stiffness modeling or the construction sequence—the magnitude and type of the applied loading has a significant influence on the overall settlement behavior. This study aims to identify which load combination should be considered as settlement-relevant for structural design purposes.

To this end, four different load combinations are applied, each representing a plausible range of loading as defined in Eurocode:

the quasi-permanent combination,

the frequent combination,

the characteristic combination with partial reduction factor αa

the characteristic combination

The settlement distributions resulting from these combinations are evaluated in terms of their impact on internal force redistribution, focusing on selected structural elements. The analysis examines how different load levels influence the restraining effect and the resulting settlement behavior.

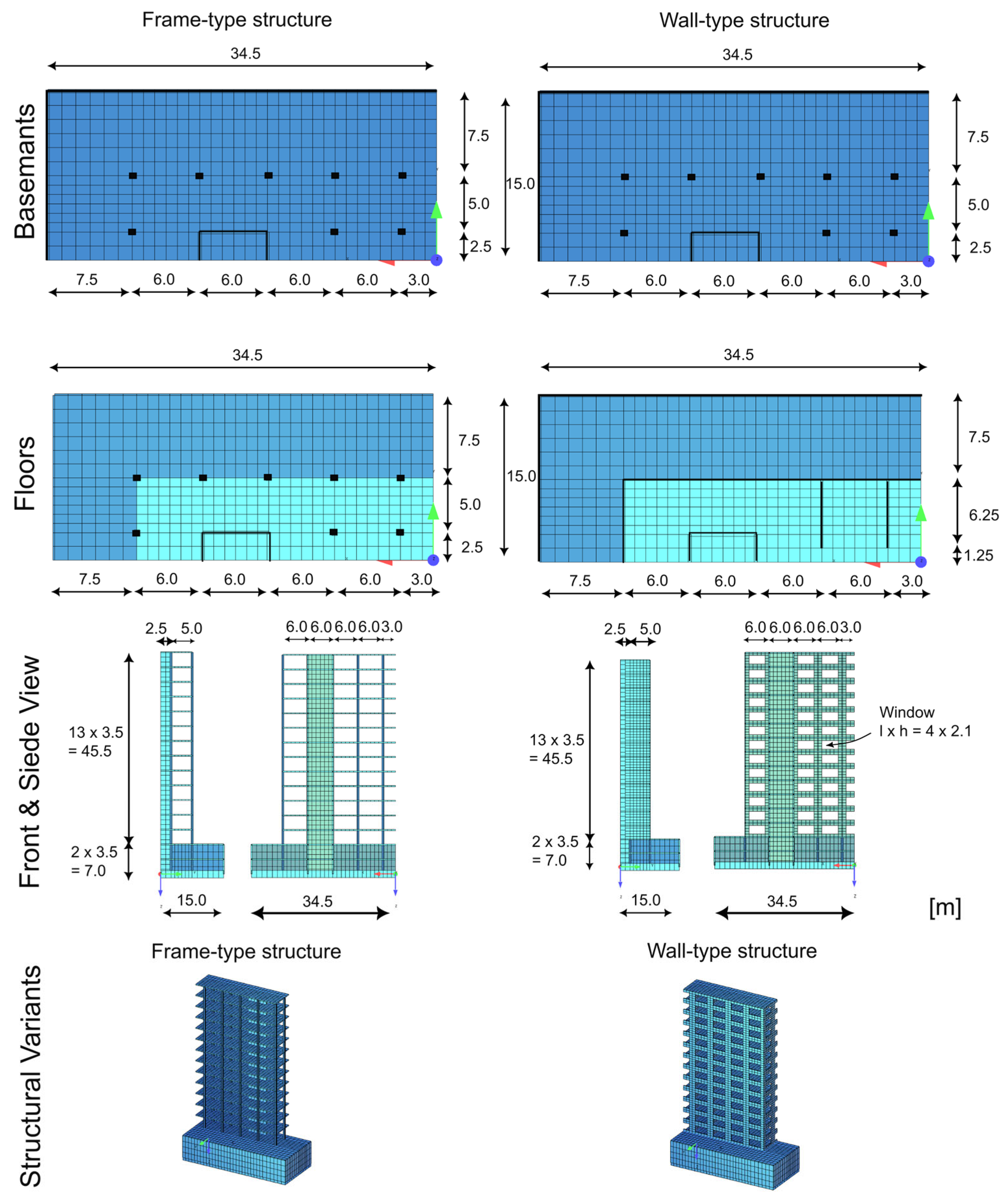

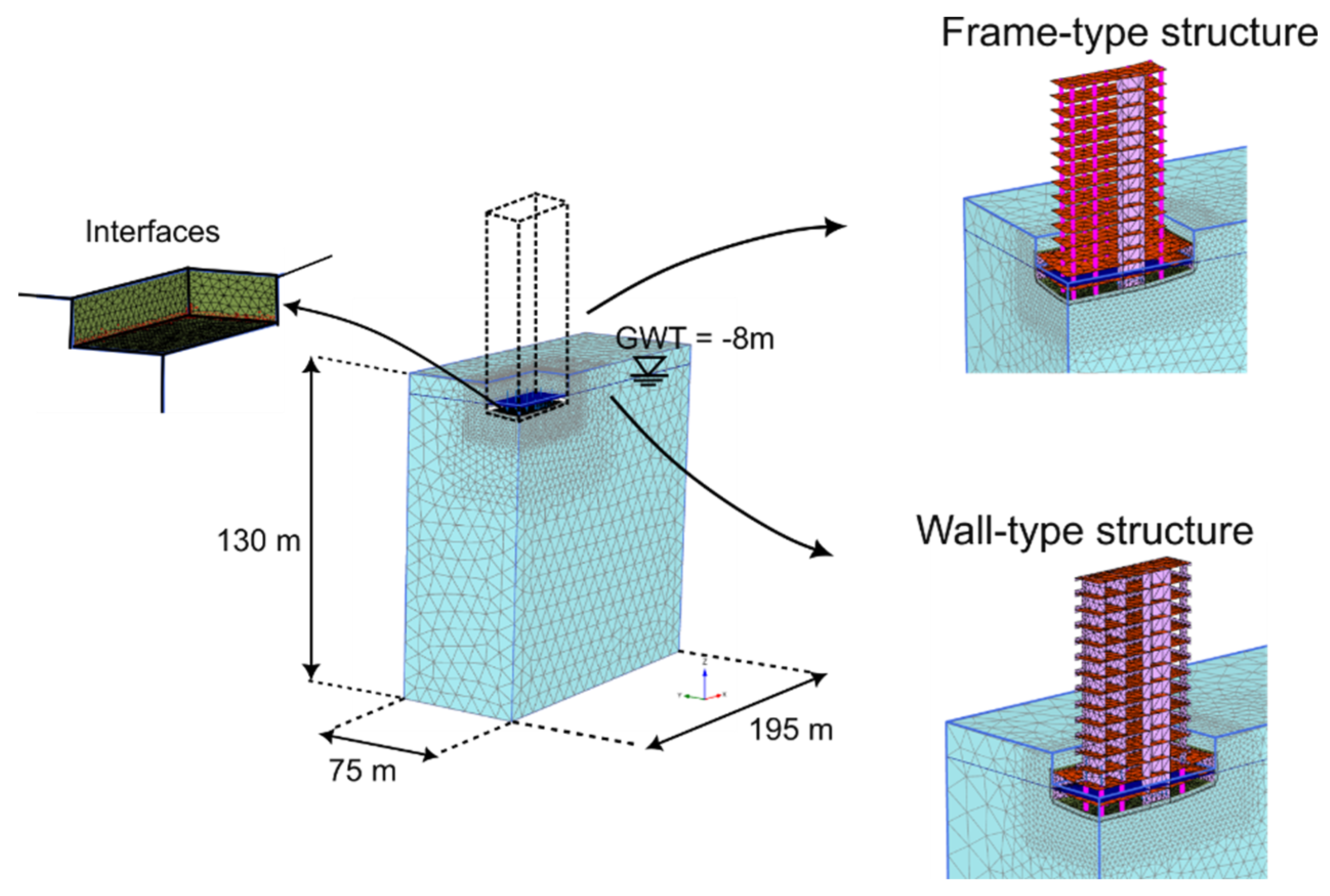

To explore the influence of structural stiffness on load redistribution, two representative building types are analyzed: a comparatively stiff wall-type structure and a more flexible frame-type structure. Each building is placed on three different soil types—sand, silt, and clay—under drained conditions. This allows for a comparison of how soil type and stiffness influence the load redistribution triggered by settlements.

For each case, the selected load combination is first applied to a model with fully fixed supports to establish a reference load distribution. Subsequently, the same combination is used in the geotechnical model to simulate the resulting settlements and analyze their impact on structural behavior.

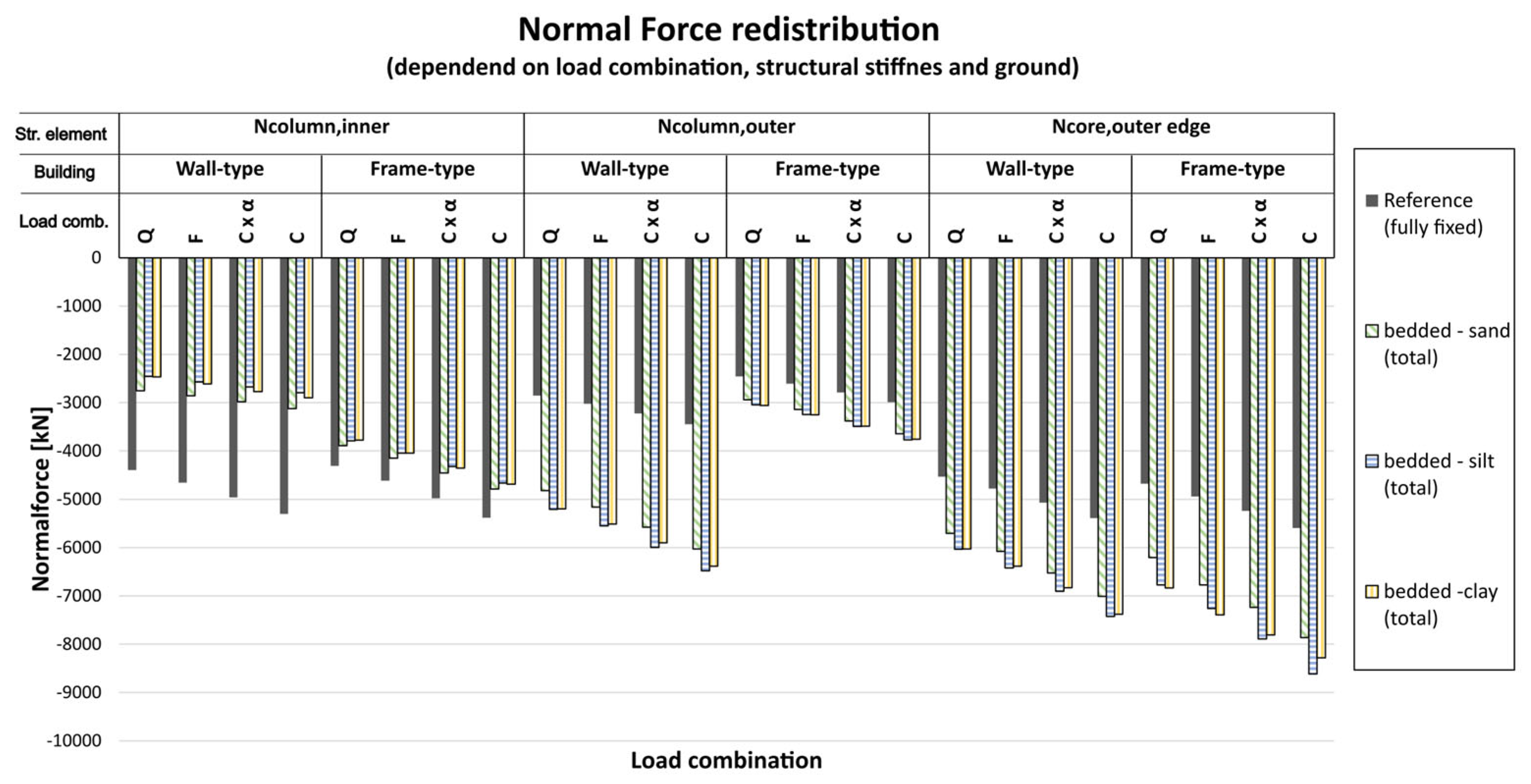

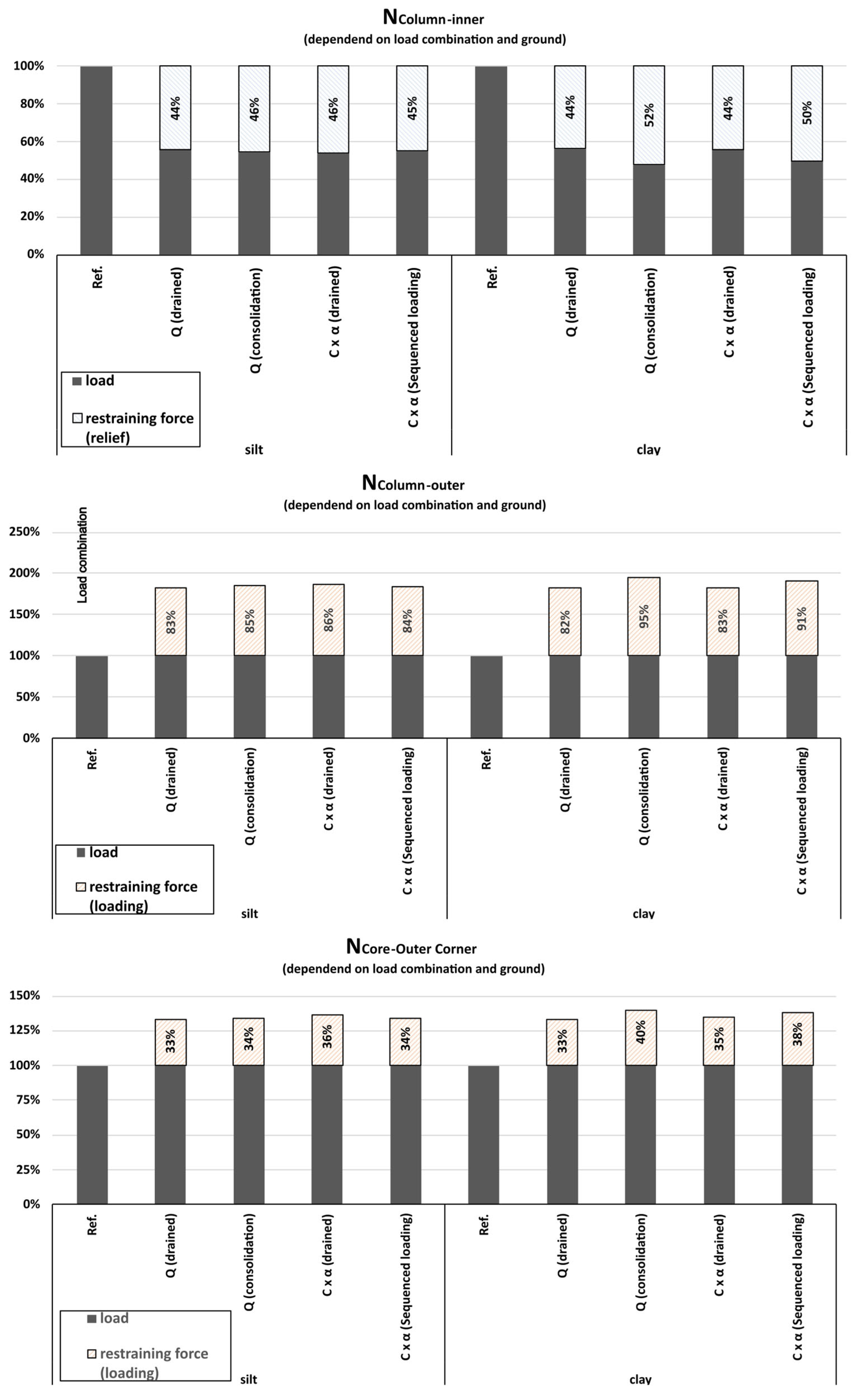

Figure 8 presents the total normal force acting on three representative structural members—the inner column, outer column, and the outer core edge—under various load combinations and soil conditions.

The grey bars represent the reference case, calculated using a fully fixed model without soil-structure interaction. As expected, the normal force in these members increases with the load level, reflecting the unaltered internal force distribution.

When bedding is considered, however, the results show a clear redistribution of internal forces caused by differential settlements. In general, loads are redistributed from the inner column, located in the more heavily settled central area, toward the outer column and the core edge, which are less affected by settlement and typically stiffer. This redistribution pattern is especially pronounced in the stiffer wall-type structure, where differential settlements induce stronger internal force shifts.

Regarding soil type, the redistribution becomes more significant in softer soils, particularly in silt and clay. The greater deformability of these soils leads to increased differential settlements, thereby amplifying the structural response.

An additional observation from the figure is that stiff elements, such as the core edge in the frame-type structure, attract a disproportionately high share of restraining forces. This indicates that in flexible structures, local stiffness variations (e.g., stiff core vs. flexible frame) enhance the settlement-induced redistribution more strongly than in generally stiff systems.

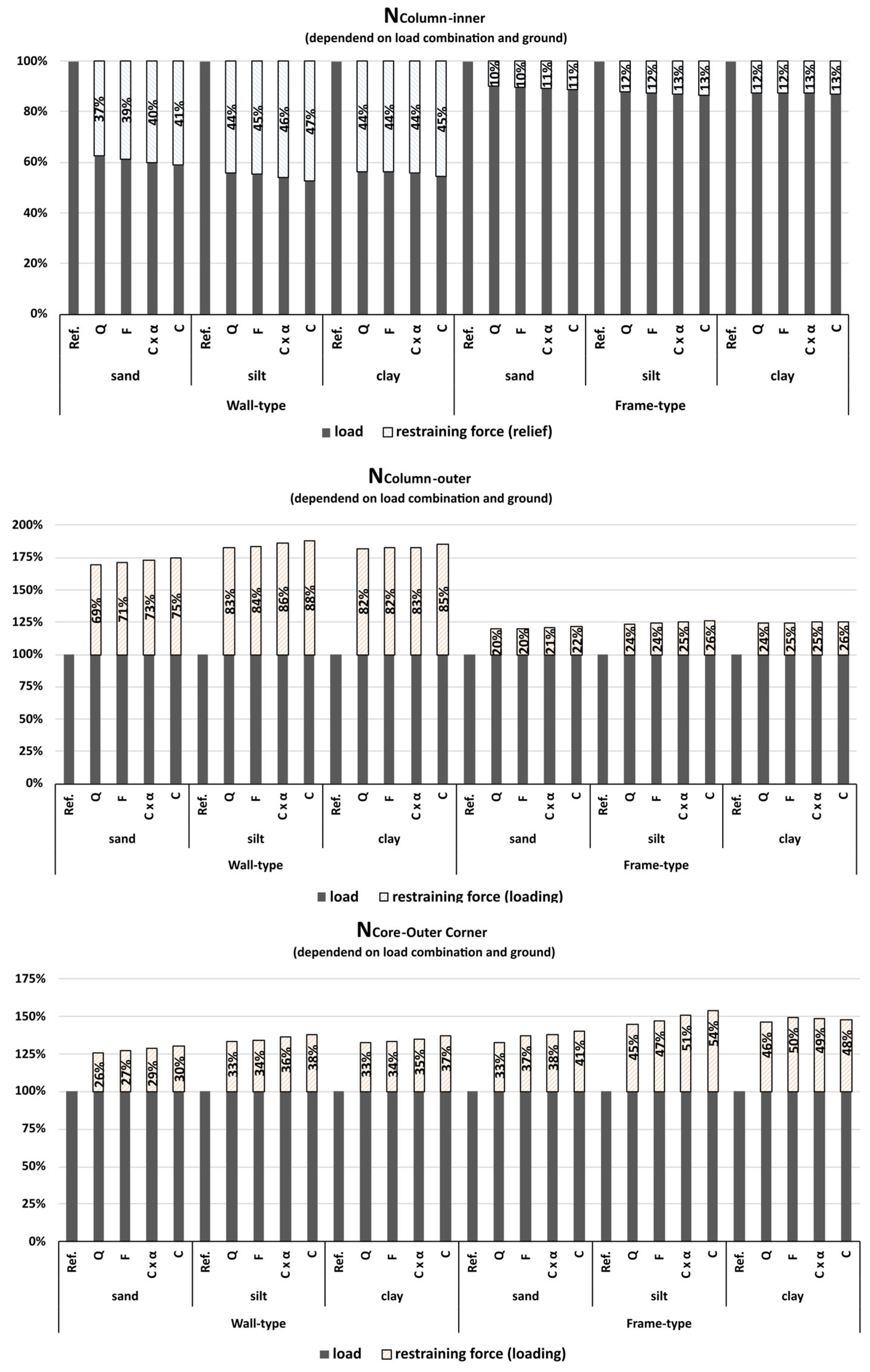

In all members, the

total normal force increases with higher load combinations. However, the

relative contribution of restraining forces behaves differently depending on structural stiffness, soil type, and member location as shown in

Figure 9.

For the inner column, a significant share of the total force is relieved due to settlement-induced redistribution in the wall-type structure, ranging between 37% and 45%, depending on the load combination and subsoil. In contrast, the frame-type structure, being more flexible, shows a much lower restraining effect—only 10% to 13% of the total force is relieved due to settlement-induced restraint.

Across all soil types, the variation of restraining ratio due to load combination is relatively small. For the wall-type on sand, the restraining share increases from 37% (quasi-permanent) to 41% (characteristic), a difference of 4%. In silt, this range narrows to 3%, and in clay, to just 1%, indicating that with softer soils, the relative effect of load level on restraint becomes less pronounced.

In the outer column, the restraining component is positive, reflecting additional loading due to the outward redistribution of forces. The wall-type structure again exhibits stronger restraint, with restraining shares from 69% to 88%, whereas the frame-type structure shows a much smaller increase of only 20% to 26%. Also here, the influence of load combination decreases with softer soils: for the wall-type on sand, the restraining force increases by 6% across load combinations, while in clay, the difference drops to 3%. For the frame-type, the total variation remains around 2%, confirming the lower sensitivity of flexible systems.

The core’s outer edge shows high restraining effects in both structural types. Interestingly, the restraining share is even higher in the flexible frame-type structure, with values ranging from 33% to 54%, compared to 26% to 38% in the stiffer wall-type structure. This suggests that local stiffness—even within a globally flexible system—can attract significant restraining forces when differential settlements occur.

Moreover, the range of restraining variation across load combinations is largest in the core region. While the wall-type shows a moderate variation of about 4%, the frame-type exhibits higher sensitivity (8%), especially on clay, where the restraining share increases from 46% (quasi-permanent) to 50% (frequent) and slightly decreases to 48% (characteristic). This could potentially be explained by plastic deformation effects in the outer clay regions, which may reduce differential settlements locally and balance loads at higher load levels.

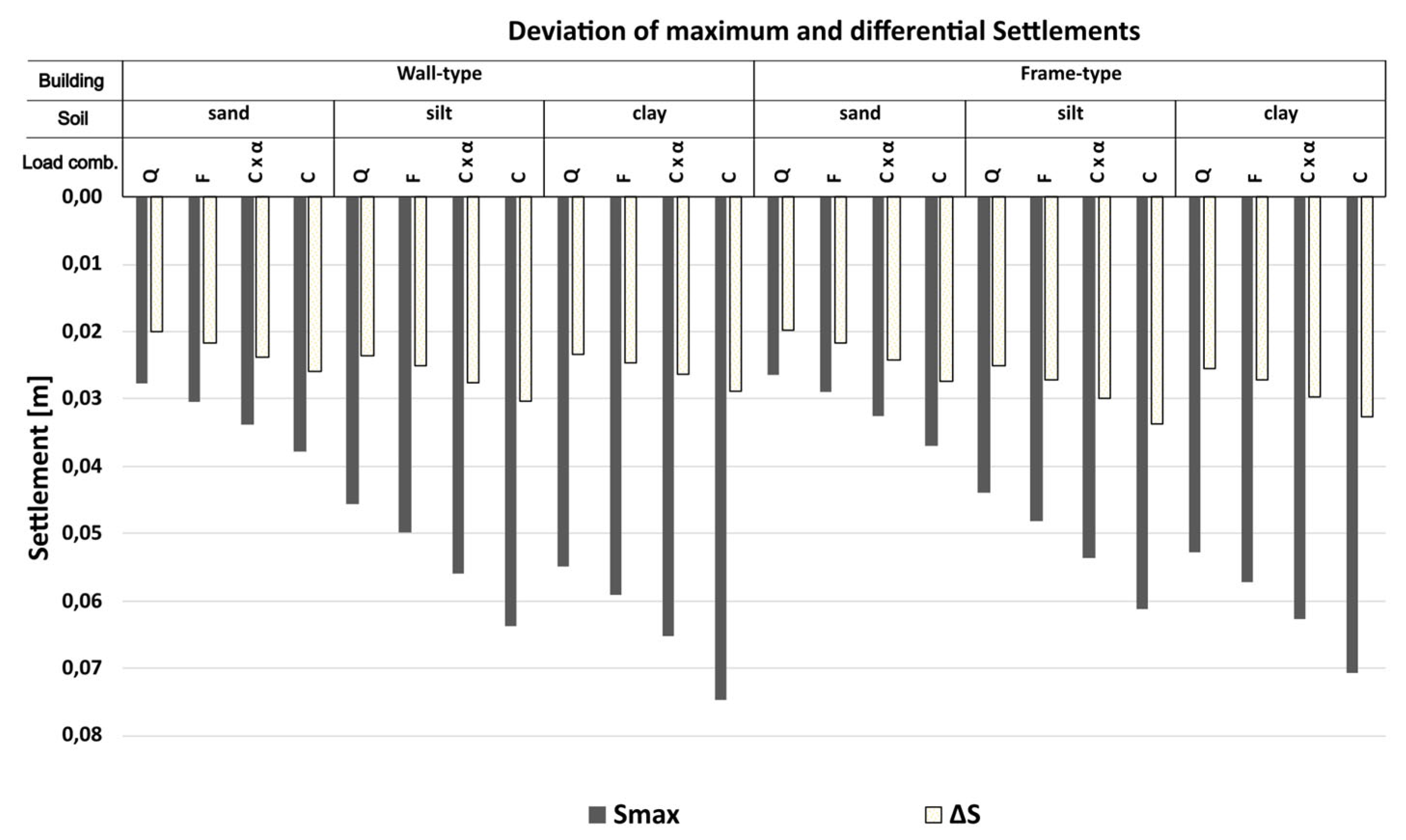

Figure 10 illustrates the comparison of maximum and differential settlements under various load combinations, normalized with respect to the characteristic load combination. The grey bars represent the maximum settlement S

max, while the yellow bars show the maximum differential settlement (ΔS). Both are expressed as a percentage of the values resulting from the characteristic load combination (defined as 100%).

The results indicate a substantial reduction in settlement when the quasi-permanent load combination is applied. For maximum settlements, the quasi-permanent load case on sand leads to values of approximately 73% in the wall-type structure and 71% in the frame-type structure, compared to the characteristic case. This behavior is consistent across all soil types.

A similar trend is observed for differential settlements. The quasi-permanent combination results in about 77% of the characteristic ΔS in the wall-type structure and 73% in the frame-type structure. These findings emphasize that load level has a major impact not only on absolute but also on relative (differential) settlements. Notably, this effect appears largely independent of structural stiffness and soil type, suggesting that the choice of load combination has a dominant influence on settlement magnitudes in general.

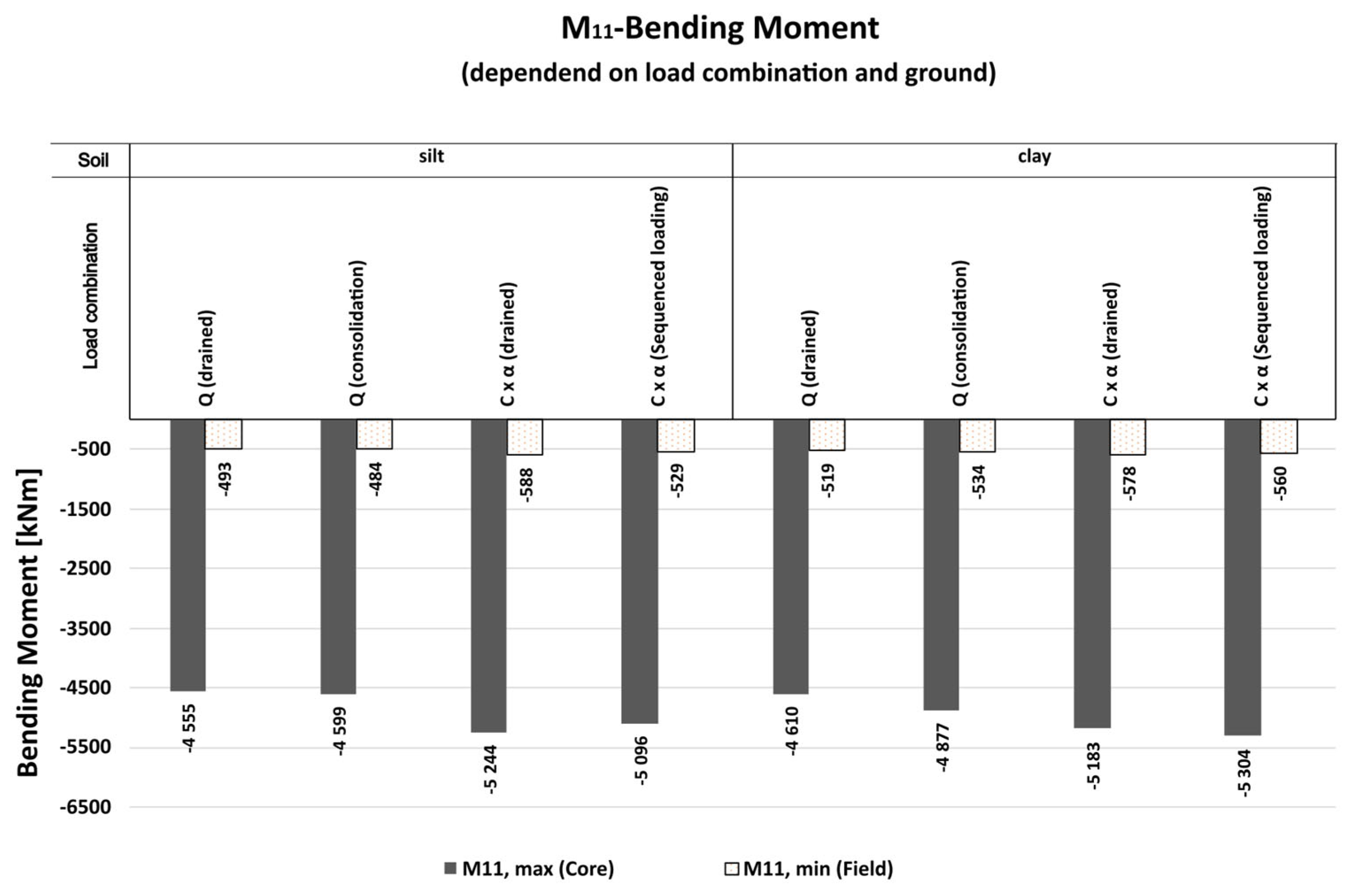

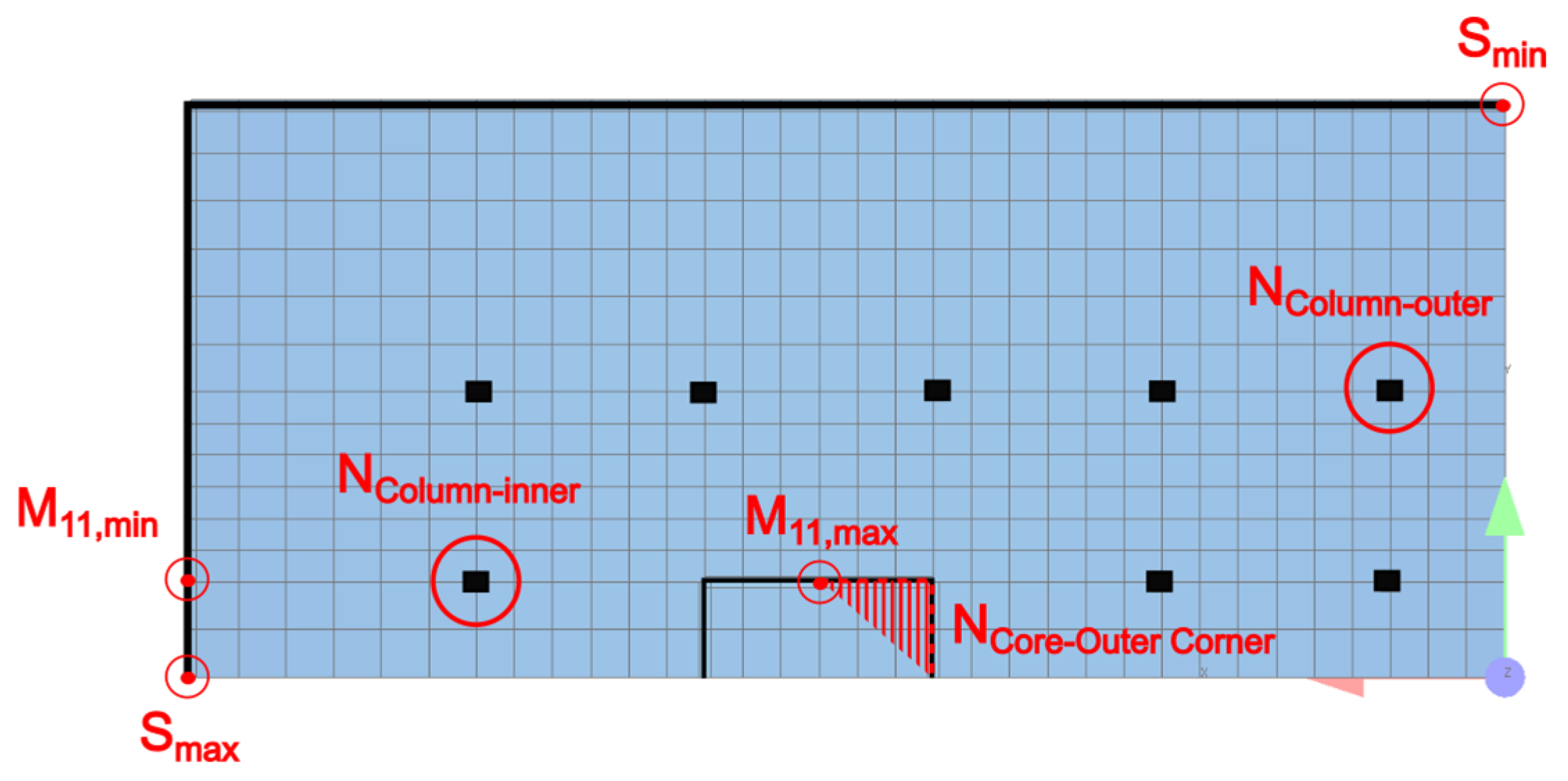

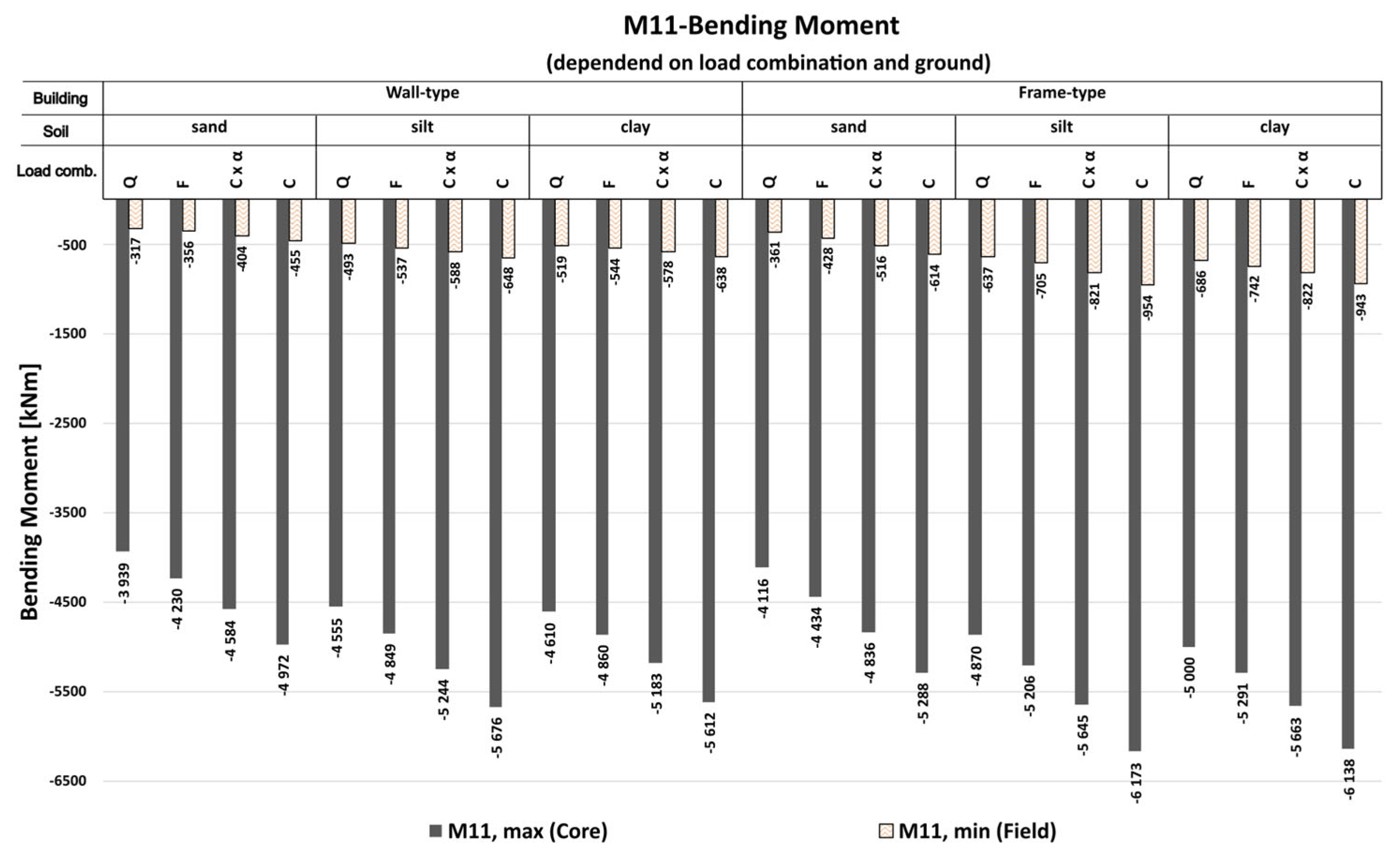

Figure 11 shows the influence of settlements—particularly differential settlements—on the distribution of bending moments within the foundation slab. As expected, the variation in maximum and minimum bending moments correlates with the behavior observed in the previous figure on settlements, indicating a direct link between soil-induced deformations and internal structural forces.

The maximum bending moments (M11,max) in the core region consistently follow the increasing load level. For both structural types, values start at around 80% (relative to the characteristic load combination) under quasi-permanent loading and increase proportionally with the applied load combination, independent of soil type. This confirms that bending moment magnitudes are primarily governed by the load level and are less sensitive to soil stiffness in this context.

The minimum bending moments (M11,min) observed in the slab field, however, show more variation—both between structural types and across soil conditions. For example, in sand, the wall-type structure reaches 70% of the characteristic moment under quasi-permanent loading, whereas the more flexible frame-type structure shows only 59%. For the frame-type structure, a clear trend with soil stiffness is visible: 59% in sand, 67% in silt, and 73% in clay.

This indicates that foundation elements of flexible structures react more sensitively to differential settlements, especially in stiffer soils, where the moment distribution shows larger relative deviations from the characteristic loading case.

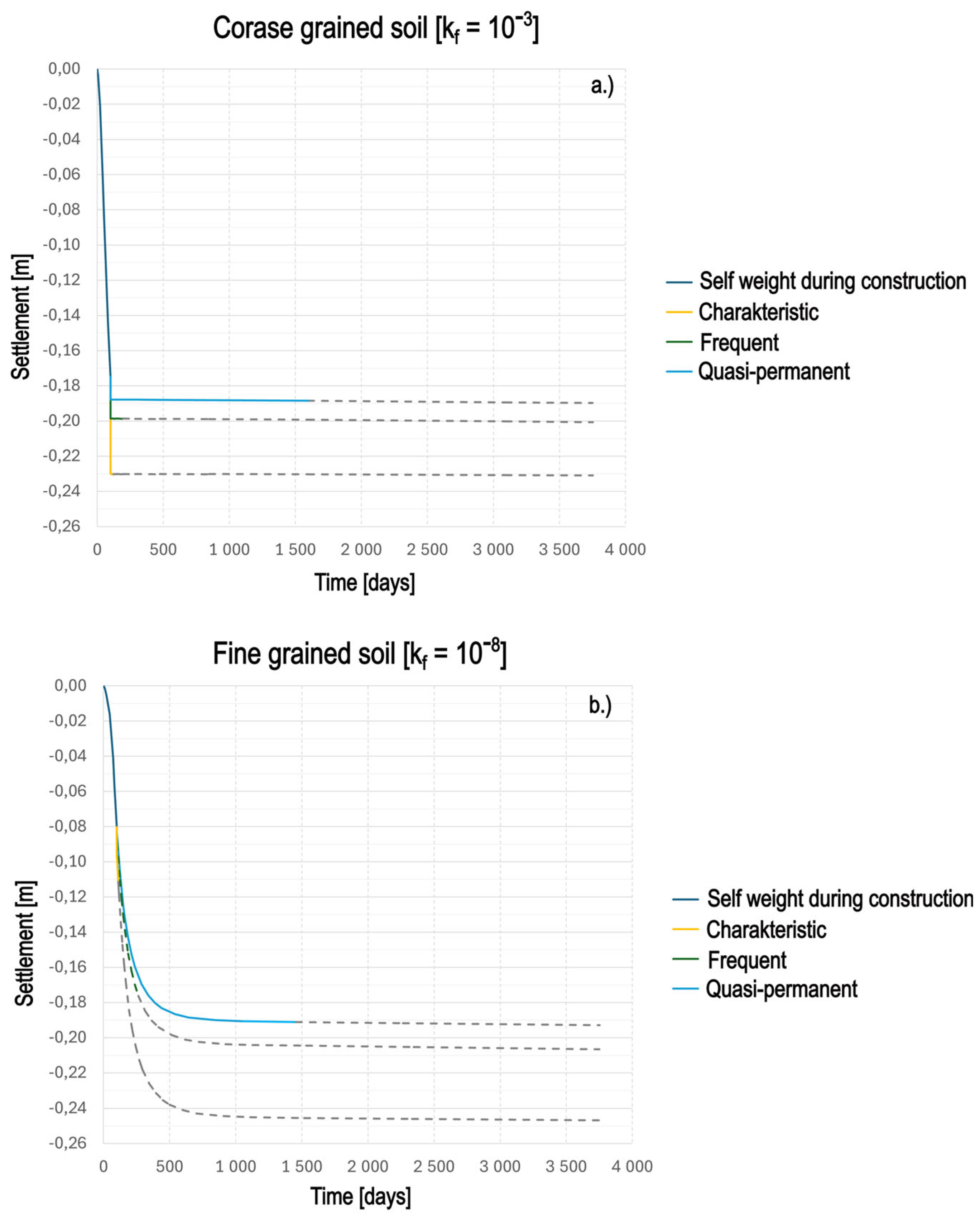

3.2. Influence of Permiabilety on Settlement Relevant Load Combinaiton

As outlined in the introduction, for soils with low permeability and present groundwater, a certain duration of sustained loading is required to allow for volumetric deformation and thus settlement. Rapid load changes or short-term load peaks—as represented by the frequent or characteristic load combinations in structural design—are not sufficient to initiate significant consolidation settlements. Instead, they typically cause volume-constant shear deformations, characteristic of undrained soil behavior. Accordingly, the quasi-permanent load combination is recommended as the basis for long-term settlement analysis in such soils, particularly in undrained conditions and materials with low hydraulic conductivity.

However, an important question remains:Even if rapid load changes do not induce volumetric settlement, do they still cause a significant change in internal stress states or force redistributions within the structure that should be considered in the design?

To address this, an additional case study was carried out for the wall-type building. The following two scenarios were compared:

Time-consolidated settlement case, simulating 30 years of continuous quasi-permanent loading, representing realistic long-term conditions in cohesive soils.

Sequenced loading case, where a sudden short-term application of the reduced characteristic load combination (including α) was imposed for one day, after 30 years of consolidation due to quasi-permanent loading.

This comparison enables an evaluation of whether short-term load variations, still trigger relevant structural responses—particularly in terms of load redistribution and internal force changes—that should be accounted for in design.

Figure 12 shows that when considering time-dependent settlement behavior, the restraining effect in structural elements increases. For

silt, the transition from

quasi-permanent drained to

quasi-permanent consolidated loading leads to an increase of approximately

2% in both the inner and outer columns and around

1% in the core.

In contrast, for clay, which exhibits much lower permeability and stronger time-dependent behavior, the restraining effect increases significantly. The inner column shows an increase of 8%, the outer column of 13%, and the core of 7%, clearly emphasizing the relevance of soil permeability and consolidation effects in long-term settlement analysis.

Looking now at the sequenced loading case—where, after long-term consolidation under quasi-permanent loading, a short-term application of the reduced characteristic load is superimposed—it becomes apparent that this temporary loading spike does not increase the restraining effect. Instead, a slight reduction in restraining forces can be observed. This is likely due to additional plastic deformations occurring under undrained conditions, which locally reduce stiffness and thus limit further redistribution.

From a structural design perspective, it would only be necessary to consider such a short-term settlement distribution—instead of the long-term quasi-permanent case—if the resulting internal force redistributions exceeded the range observed under realistic service conditions. However, this is not the case in the present study. The additional effects of sequenced loading remain within the expected variation and do not justify separate consideration in settlement-relevant design procedures.

Regarding the bending moments, the

sequenced load combination results in approximately a 10% higher maximum bending moment in the foundation slab and a 9% higher field moment in silt. In nearly impermeable clay, this difference decreases to about 8% for the maximum moment and 5% for the field moment.

Figure 13.

Bending moments M

11 in the foundation slab for different load combinations and soil types (silt and clay) considering time effects. The moments are taken from the Gauss point closest to the investigated location, as shown in

Figure 7.

Figure 13.

Bending moments M

11 in the foundation slab for different load combinations and soil types (silt and clay) considering time effects. The moments are taken from the Gauss point closest to the investigated location, as shown in

Figure 7.