Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

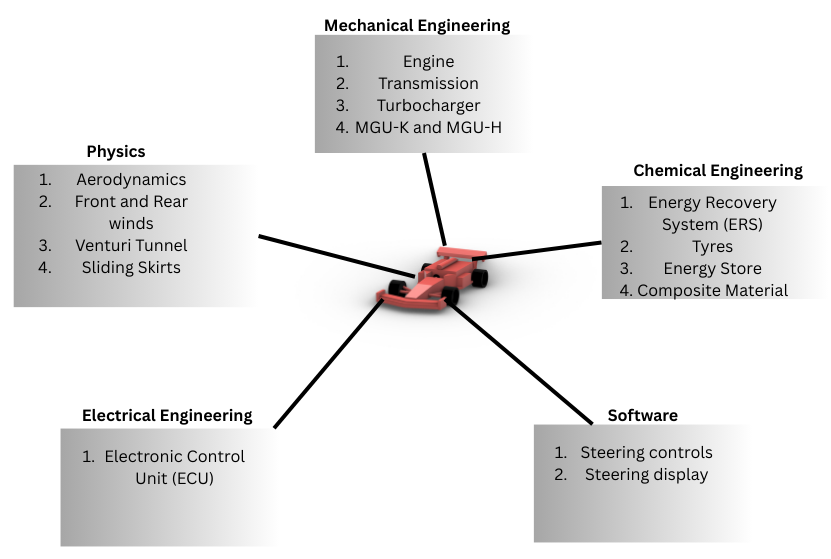

Introduction:

Material:

Structure and Aerodynamics:

Structure Information:

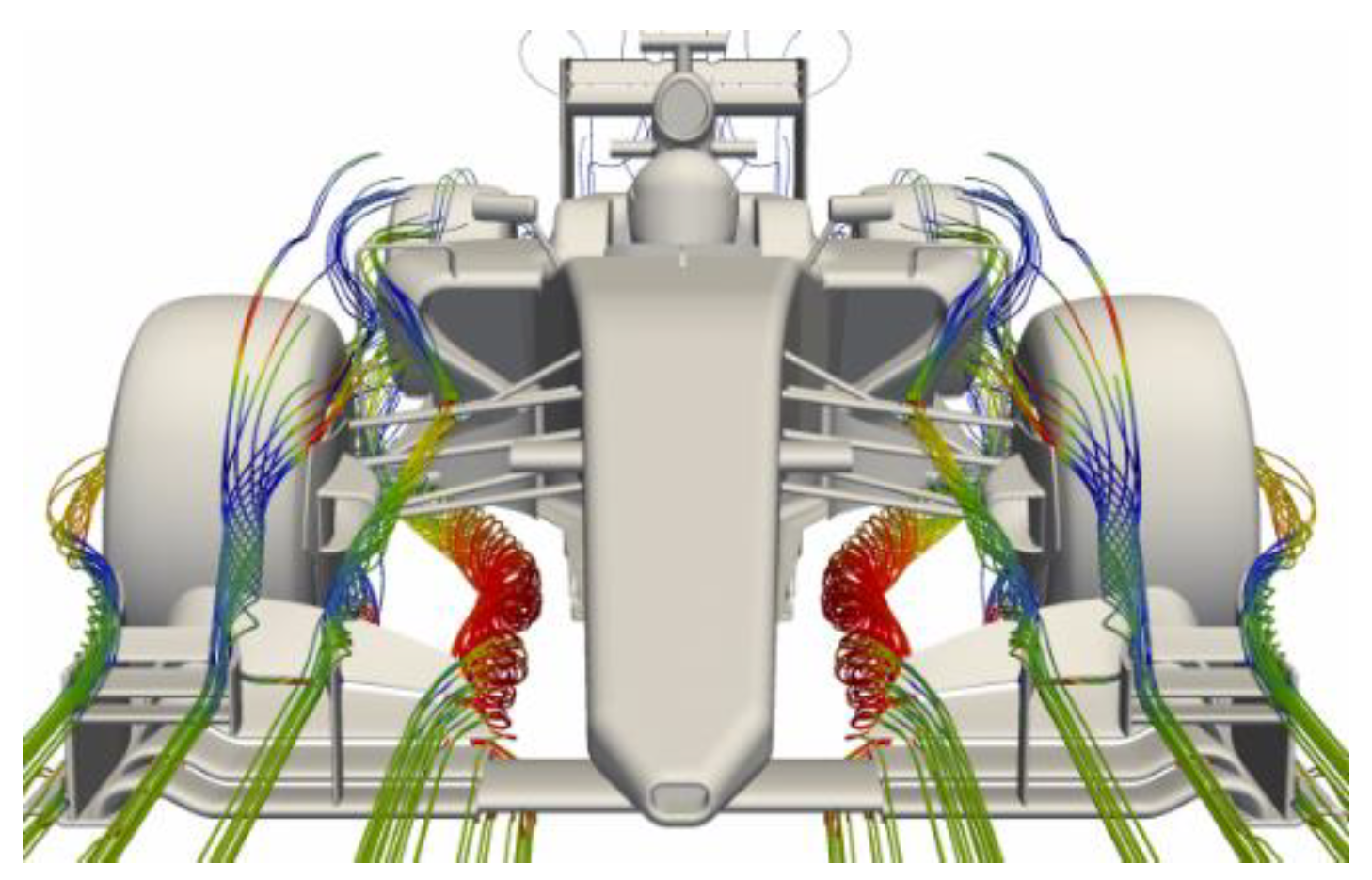

Aerodynamics:

Functions:

- 1)

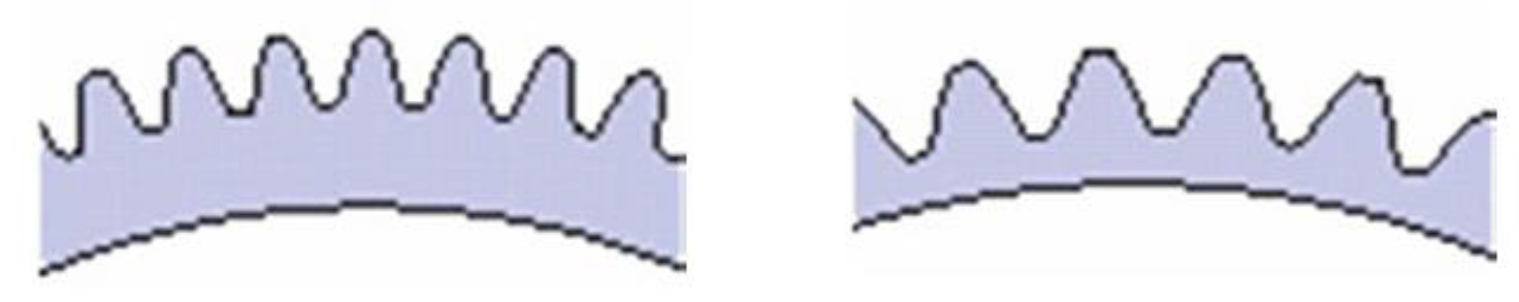

- Wings and spoilers: Enhances the aerodynamic efficiency through smooth air to produce controlled pressure difference in higher and lower car surfaces to trigger negative lift to generate high contact forces between wheels and ground for achieving high lateral speeds. With increased downward force, it enables high cornering grip and stability. This concept is based on Bernoulli’s Theorem. Front wings are engineered in thick and streamlined geometry to generate more downward lift enhance tyre-surface grip. Due to rear placement of engine, same thickness of rear wings would lead uncontrolled weight distribution with unbalanced downward force leading to lifting up of the car from front. As a result, rear wings are designed to be thin in order to maintain centre of gravity through proper weight and force distribution in front and rear end for optimum car performance and stability. [2,7]

- 2)

- Venturi Tunnels: Help in providing low pressure area beneath the car body triggering enhanced downward lift as in case of aeroplane wings.

- 3)

- Sliding skirts: Optimises the effect of venturi tunnels by packing up space between car side body and track to prevent air from escaping venturi tunnels. This provides efficient fluid flow through venturi tunnels to enhance aerodynamics.

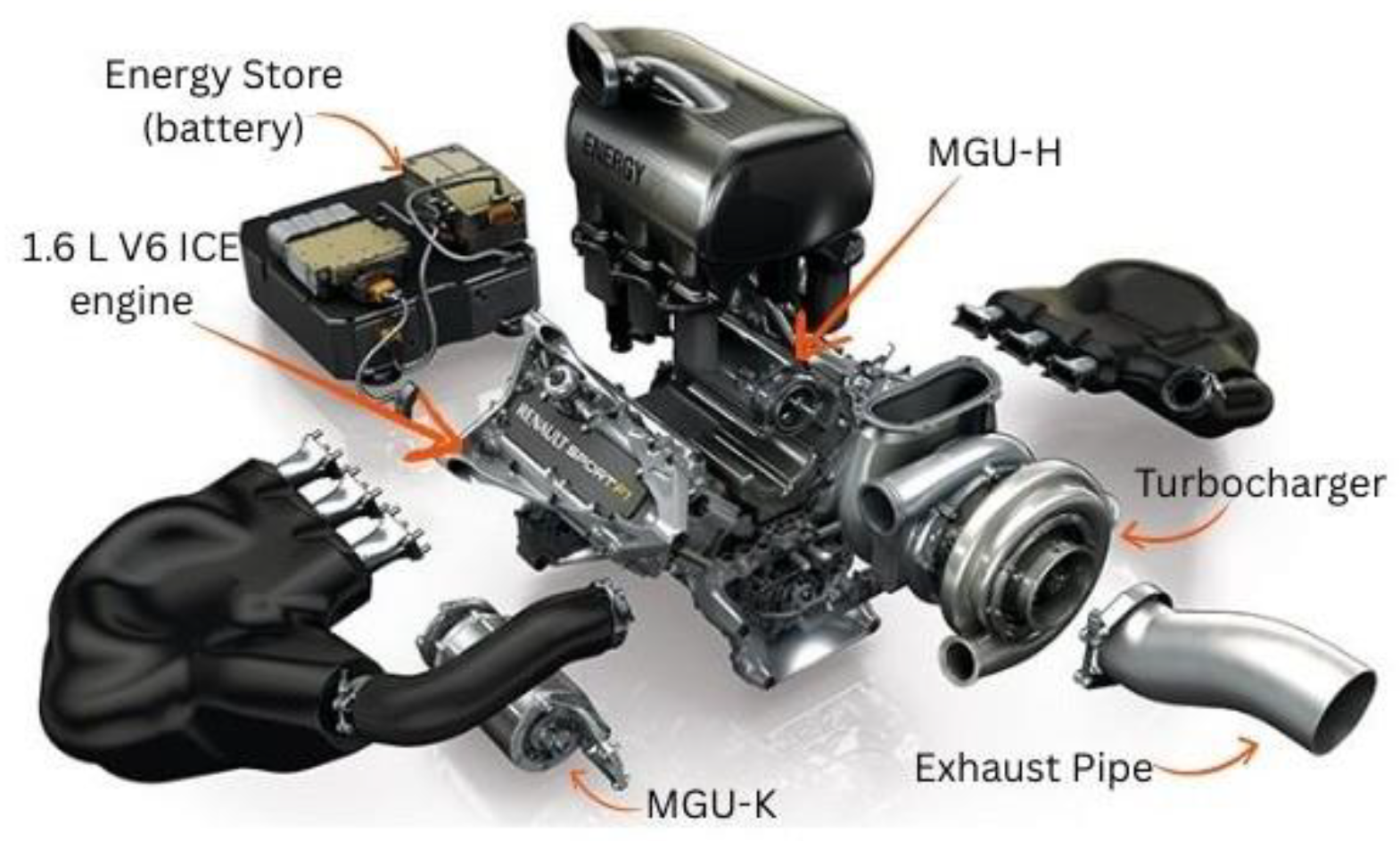

Power Unit:

| Specification | Power Unit | |||

| Traditional (1980-2000) | Traditional (2000-2003) | Pre-Modern (2007-2008) | Modern (2013-2024) | |

| Configuration | 3.5 litre Naturally Aspirated V12 | 3 litre Naturally Aspirated V10 | 2.4 litre Naturally Aspirated V8 | 1.6 litre Single-Turbo V6 |

| Bore diameter (mm) | 88 | 97 | 97 | 80 |

| Stroke length (mm) | 47 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 53 |

| Horsepower(hp) | 740 | 900 | 735 | 850 |

| Max RPM | 14400 | 18800 | 20000 | 15000 |

| Weight (kg) | 154 | 99 | 95.1 | 150 |

- 1)

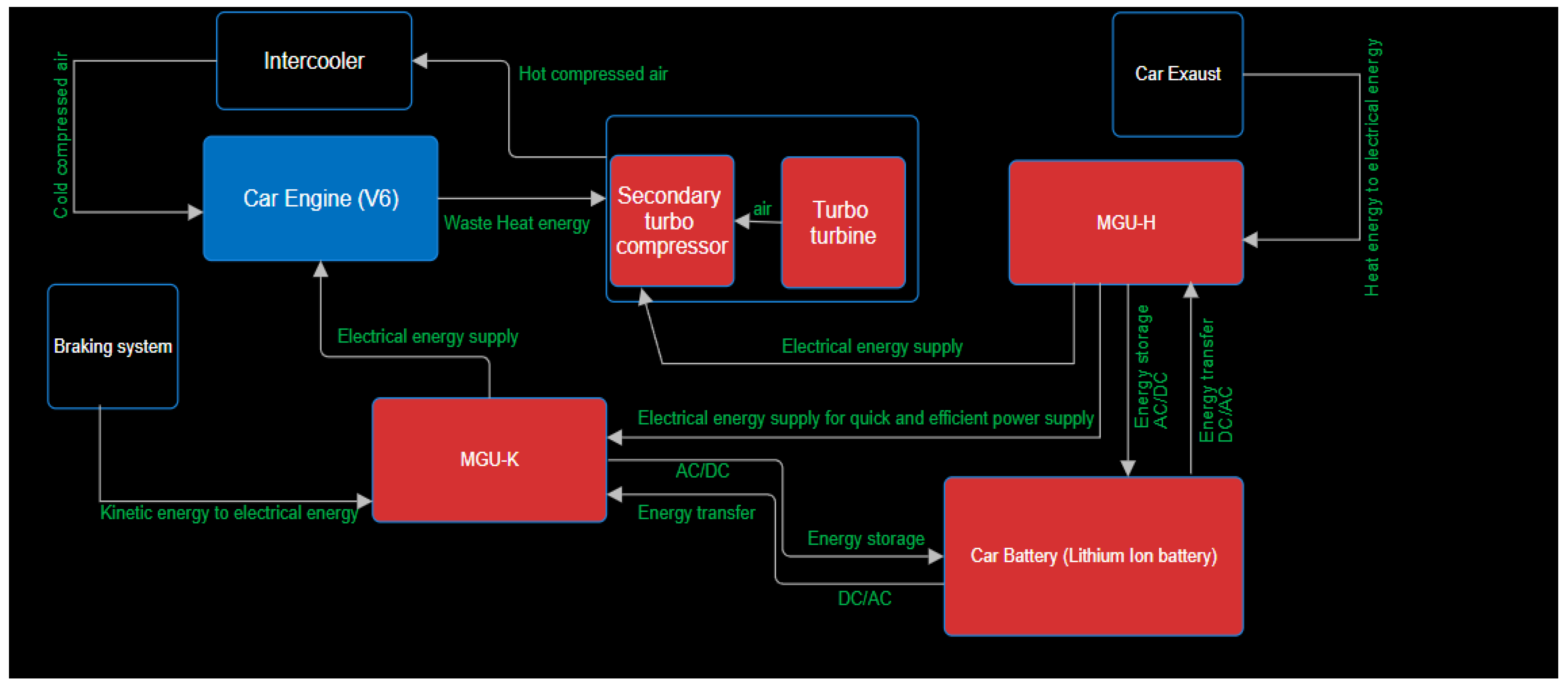

- ICE: The Internal combustion engine (ICE) of a F1 car like any other normal automobile, converts chemical energy in the fuel into thermal energy (Heat energy). This thermal energy is transformed into mechanical energy in order to drive the crankshaft and pistons. But not all thermal energy is converted into mechanical energy due to 2nd law of thermodynamics (states that it’s impossible to convert 100% of heat into work). As a result, a significant amount of energy is released through exhaust systems, cooling systems and frictional forces.

- 2)

- TC: The energy released by engine is used by Turbochargers (TC) to rotate its turbines and this rotational energy is passed to secondary turbine compressor (part of TC) which compresses the fresh air through F1’s air intake system and releases that compressed air into engine. At first, the compressed air is hot and is processed through intercooler and cool compressed air is transferred to engine. As the air is compressed, more air can fit inside engine resulting in more power generation and more performance. There is a situation when there is not enough heat energy produced by ICE for turbo to work especially at initial rpm. This lag where turbo is incapable of producing extra boost is called Turbo Lag. Although this equation is not common in literatures, it represents the dependence of turbo lag on Inertia of rotor, rotor speed and net torque.

Derivation-

- 3)

- MGU-H: Motor generating unit- Heat (MGU-H) receives exhausts gas energy which the generator converts into electrical energy. This electrical energy is either directly provided for excess power generation via MGU-K so that it could further provide additional power to crankshaft or to TC compressor in order to prevent Turbo lag, or is directly stored in Energy Store (ES) i.e. Car battery for future use.

- 4)

- MGU-K: Motor generating unit-Kinetic (MGU-K) takes kinetic energy produced during braking of car which is then converted into electrical energy by the generator. This electrical energy is either stored in car battery or is provided to engine for excess power generation. It produces extra power of about 160 PS which adds up to 840 PS of engine core power. MGU-K stores about 2MJ of energy and loses about 4MJ of energy for a single lap.[3,4]

- 5)

- Energy Store (ES): Lithium-ion battery is used in F1 cars as it provides a good power-to-weight ratio (stores large amount of power in a lightweight battery). Also, these batteries provide electrical energy whenever demanded by driver especially during cornering or overtaking with maximum efficiency (minimum loss of heat during energy transfer). Moreover, there AC/DC converters are attached when energy is transferred from MGU’s to battery as MGU’s operates on AC current whereas Battery operates on DC current. Similarly, DC/AC converters are attached for energy transfer from battery to MGU’s.

Electronics and Control:

| Control/Button | Functionality |

|---|---|

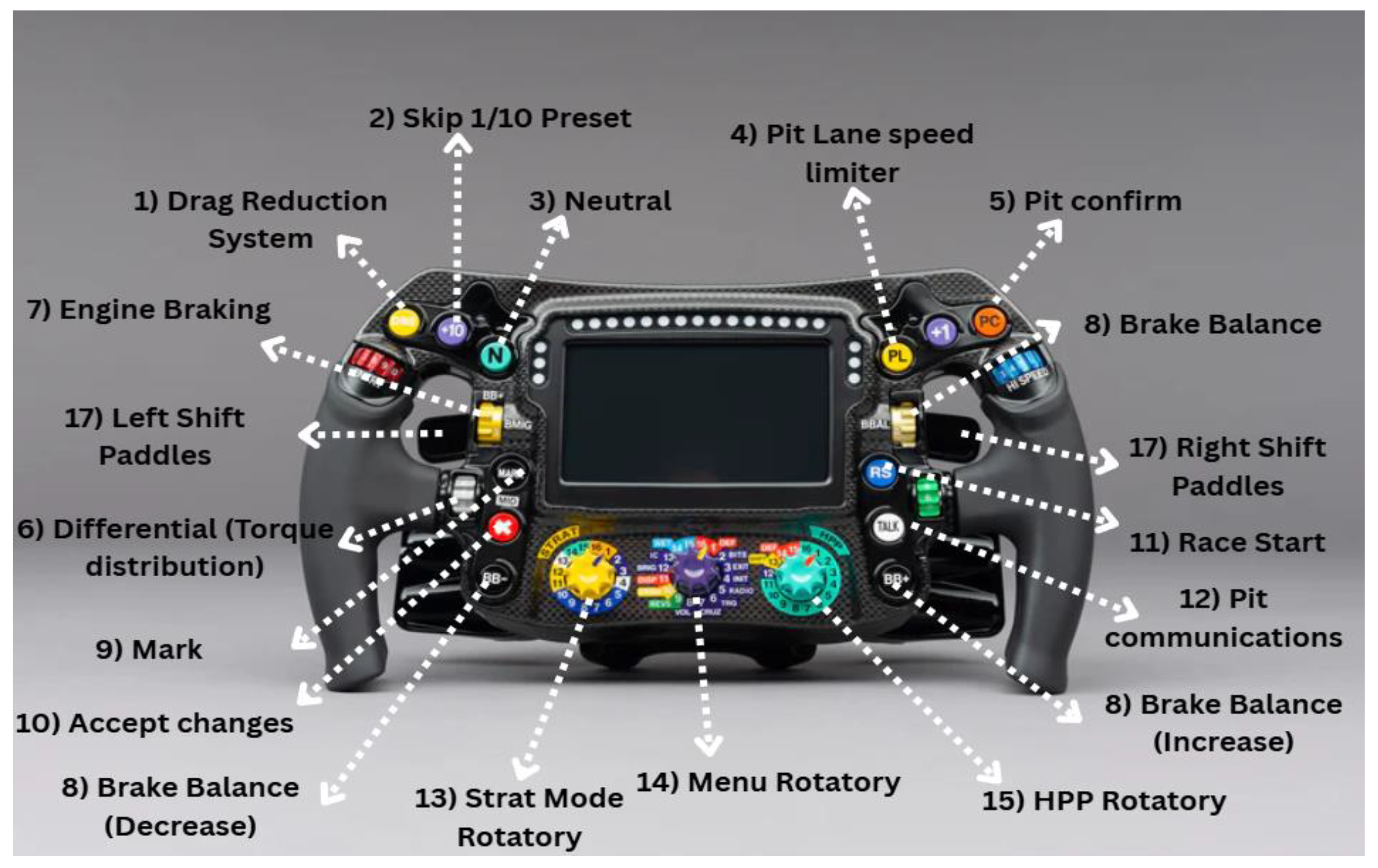

| DRS button | Also known as Drag Reduction System button Helps in decreasing drag forces by opening rear wings for mor aerodynamics which helps in increasing car speed and overall performance |

| Skip 1/10 preset button | Allows drivers to perform rapid changes in car according to their track conditions such as modifying control systems such as Power Unit, engine mapping (engine responses to driver’s modifications). |

| Gearbox neutral | Allows the car gearbox to be in neutral configuration. |

| Pit lane speed limiter | Allows driver to set a speed limit when inside pit and this limiter is triggered through several track sensors and GPS when car is about to enter pit. So even if driver gives full throttle, the car would maintain its pit lane speed limit. |

| Pit confirm | Allows driver to send automated message to alert the crew team to get ready for pit box for some kind of upgrades like tire change or body part change. |

| Differential | Allows the driver to set a particular amount of torque to distribution between rear wheels especially during cornering or during apex. As F1 cars are Rear wheel drive (RWD), torque can only be transferred to rear wheels and not front wheels. |

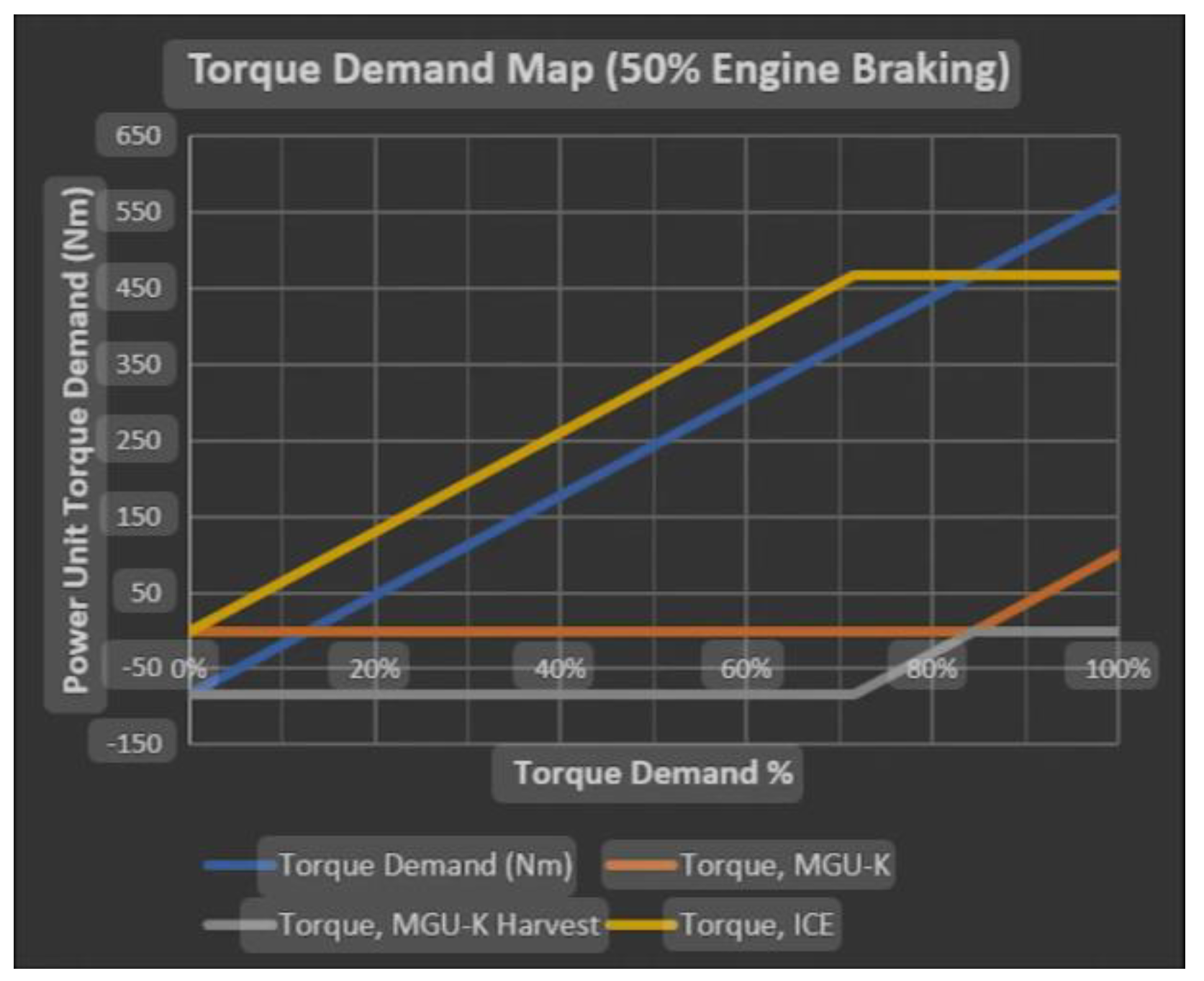

| Engine braking | Feature allows driver to control the extent to which the car should slow down when not throttled or not applied brakes. |

| Brake balance | Allows driver to decide the brake force distribution between front and rear wheels. Generally, brake force distribution is done as 60/40 or 55/45 for more efficient and balanced braking as rear part of F1 car is heavy compared to front part. |

| Race start | This button signals engine for maximum power output. |

| Radio | Allows driver to communicate with engineers and crew members in the pit in order to discuss the implementation of race strategies or adjusting car configurations. |

| Strat mode rotatory | Allows driver to adjust engine stats such as ignition timing, fuel flow to get optimum performance during for crucial moments such as overtakes, cornering. |

| Menu rotatory | Allows driver to control the display of steering wheel such as its brightness, map or other information which is being displayed on screen. This does not affect car’s performance directly. |

| HPP rotatory | This is also known as High Performance Powertrain rotatory which adjusts certain power unit components such as MGU-K (control recovery of energy through barking system or providing of stored energy to engine) for excess power transfer whenever required during the race. |

| LED | LED shows the perfect time to upshift or downshift helping drivers to maintain the efficiency of the car. It also provides information whether energy is harvested or used. The LED colours may vary according to each driver’s preference in his car. |

| Shift Paddles | Left shift paddle is used for downshifts and right shift paddle is used for upshifts. |

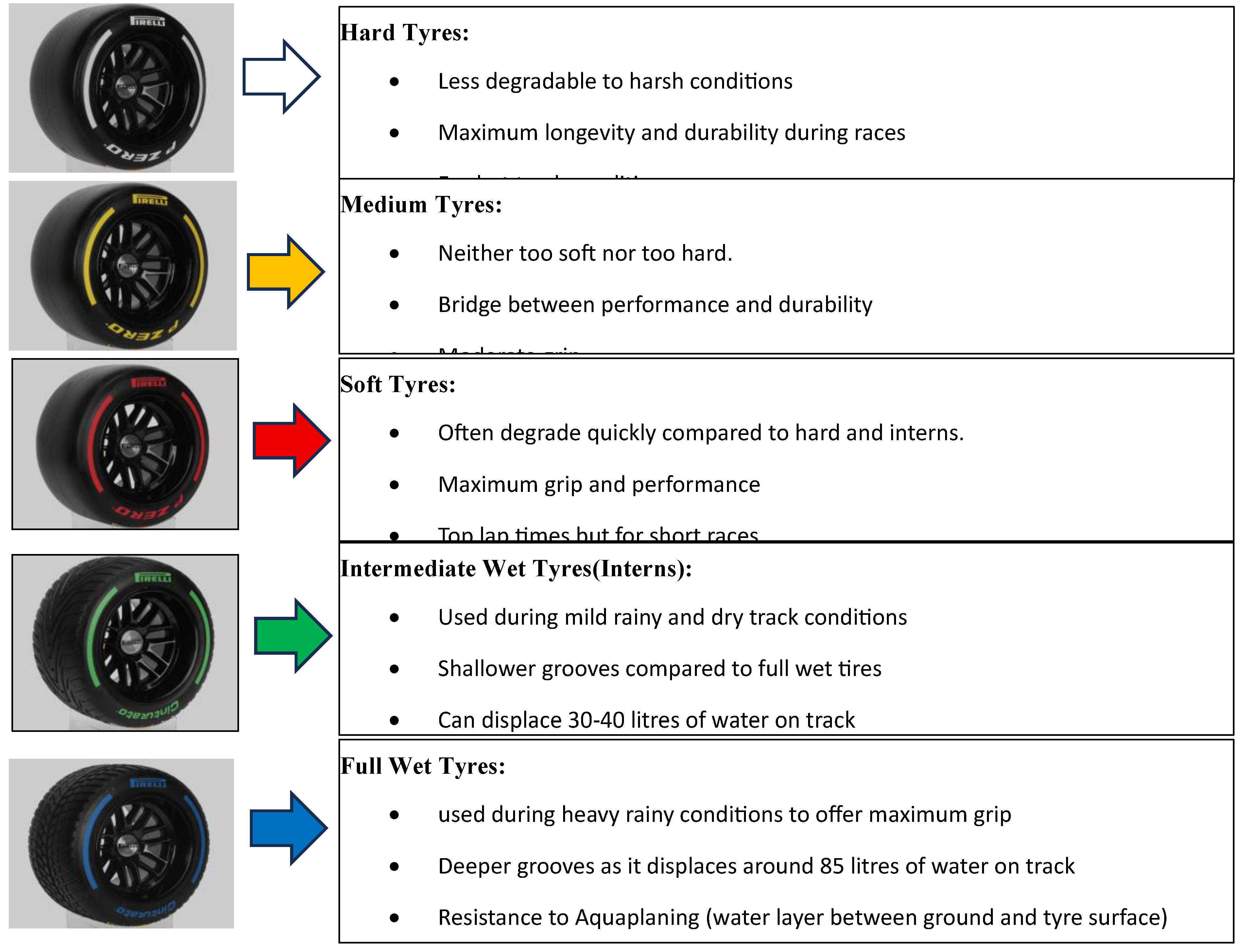

Tyres:

| Compound | Characteristics | Hard | Medium | Soft |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Hardest Compound | Y | N | N |

| C2 | Extreme Durability | Y | Y | N |

| C3 | Versatile Compound | Y | Y | Y |

| C4 | Superior Grip | Y | Y | Y |

| C5 | Soft compound | N | Y | Y |

| C6 | Maximum Softness | N | N | Y |

| Events | Slick Tyres | Wet Tyres | Total Tyres allocated (Each Driver) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hard Tyres | Medium Tyres | Soft Tyres | Wet Intermediate Tyres | Full Wet Tyres | ||

| Sprints | 2 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 19 |

| Grand Prix | 2 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 20 |

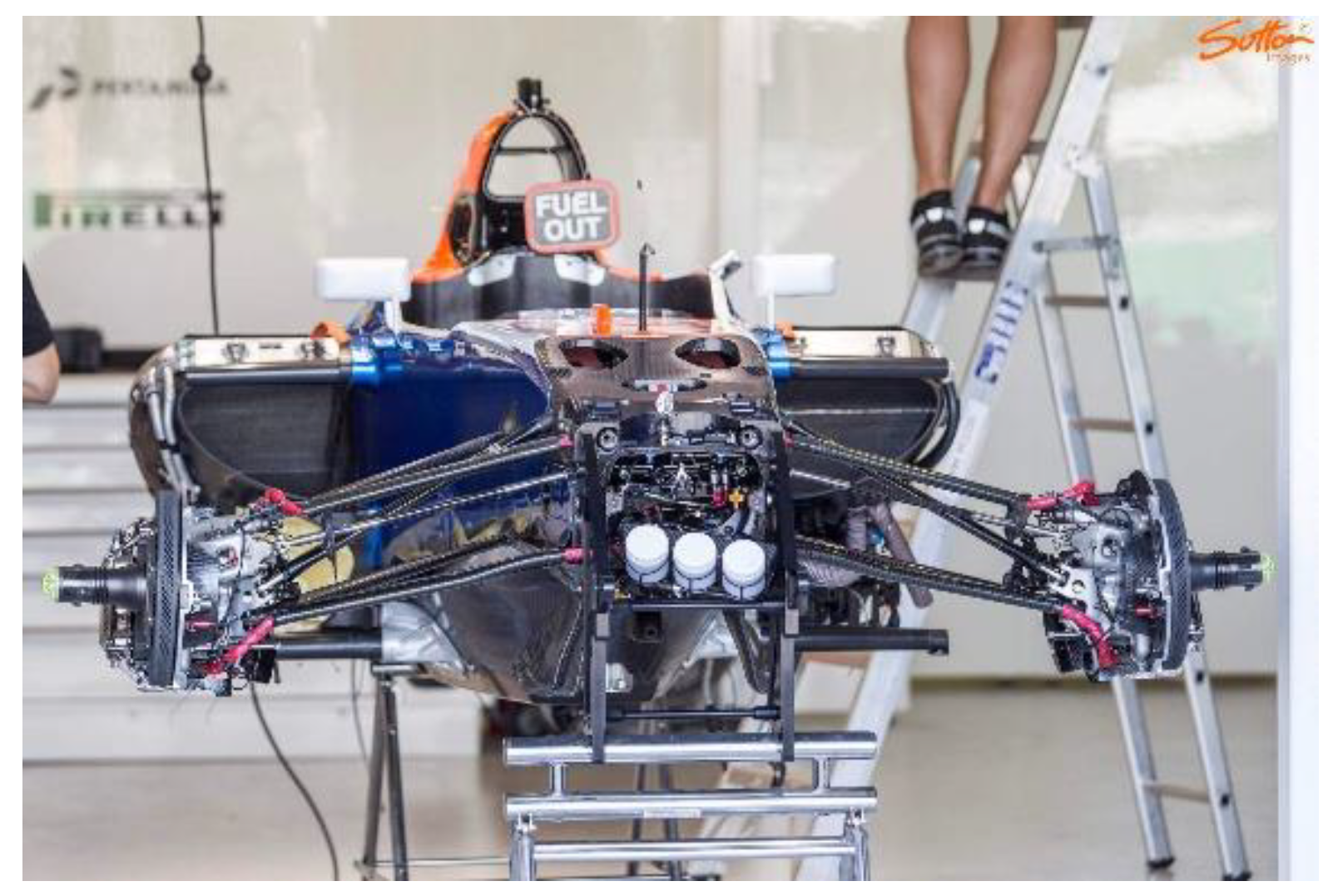

Transmission:

- 1)

- Layshaft and clutch: The power from engine is transferred from engine to layshaft which are small gears used to further rotate main gears (main shaft) when changed gears. This power from engine is transferred through a connection called input shaft which connects to clutch. The clutch further transfers power to layshaft.

- 2)

- Main shaft: The layshaft assists main shaft to rotate gears as if main shaft is provided direct power from engines, it would not be possible for gearbox to change gears when engine is active. Gears are mainly changed by gear paddles attached on F1 steering wheel. This paddles connection is attached to change cylinder which is further connected to selector barrel and this is connected to selector shaft.

- 3)

- Selector shaft: This component of F1 gearbox helps in changing and rotating specific gear (dog rings) according to driver’s demand. Specifically, selector shaft contains four selector forks which attaches to driver specific gear and rotates it accordingly. Further, selector shaft is attached to F1 differential system and this system connects to car wheels and provide engine power

- 4)

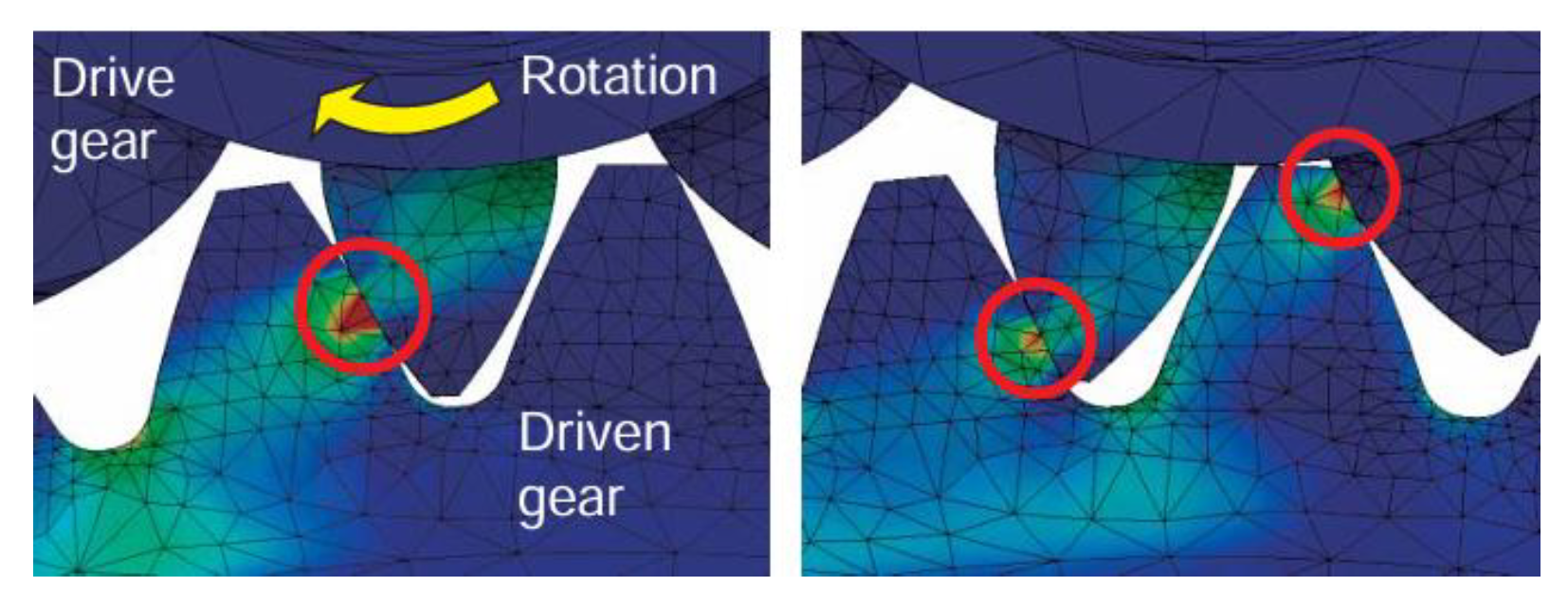

- Gear Teeth: The design of teeth i.e. a single component of a gear plays a crucial role in effective and smooth gear shifting without wear and tear. When two gears pass and roll over each other for transmitting power, it is called Meshing. The gear smoothness depends on the way meshing takes place. When the meshing point is near the lower bottom of other gear’s teeth, it transfers greatest stress and more vulnerable to gear teeth deformation.

- 1)

- Due to oil churning: Transmission failure due to oil churning takes place when excess lubricants such as grease which leads to sliding of certain components like gears which further leads to inefficiency in transmitting energy to differential system and then to wheels. This results in decreased car power and performance on track.

- 2)

- Due to torque transmission: Transmission failure due to torque transmission takes place due to increases friction between gear components, decreased energy transfer and torque due to oil intervention/leakage in gearbox.

- 3)

- Due to oil pump drive: Transmission failure due to oil pump drive takes place when there is loss of heat/ energy from input shaft which connects engine and transmission system. This causes reduced energy input from engine into gearbox and reduced power to wheels.

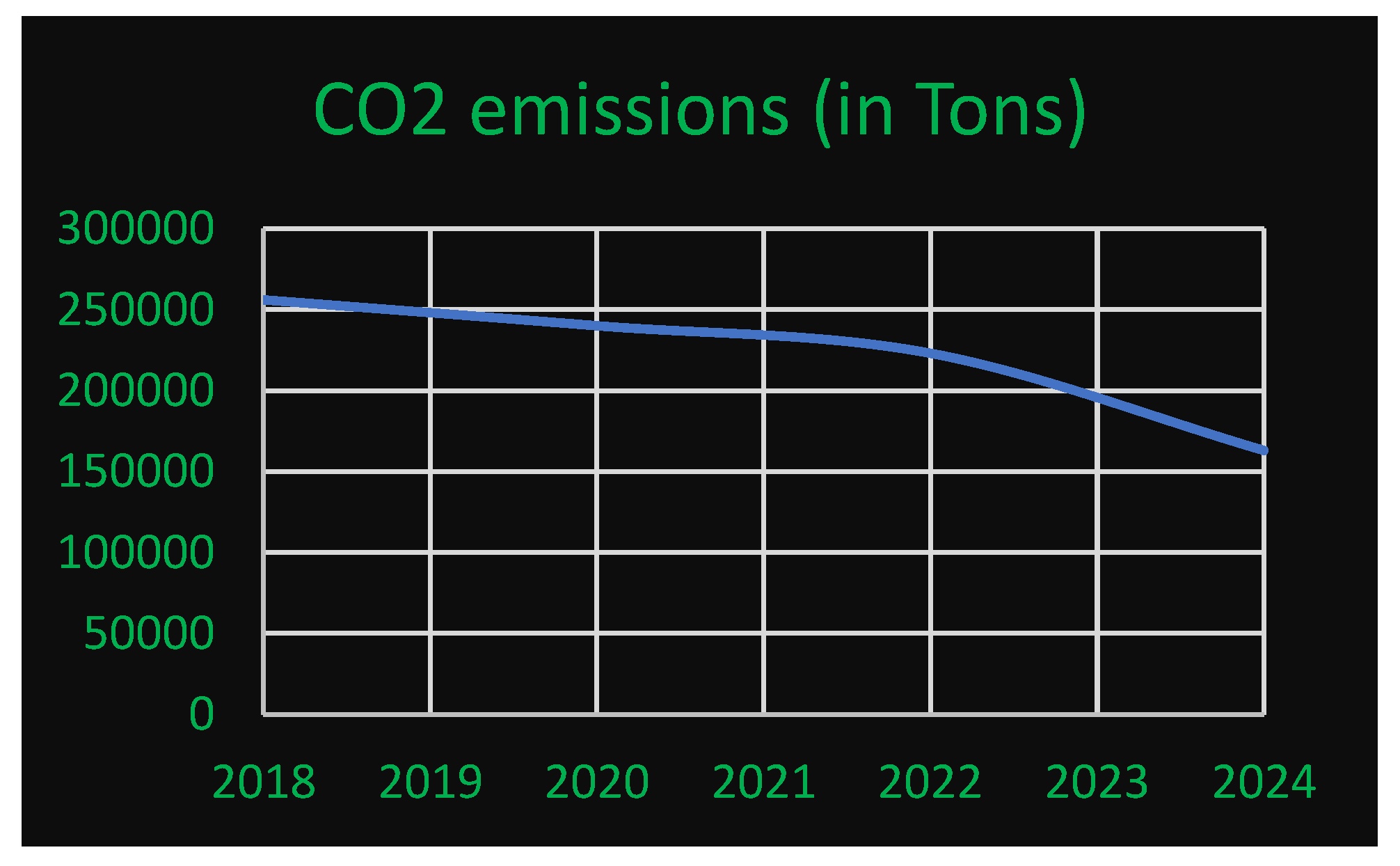

Sustainability and Future Trends of F1 Cars

Conclusions

References

- Xenia Chiles; Formula 1’s Drive to Environmental Sustainability, SJTEIL, Volume 15, Issue2, (link).

- Xabier Castro, Zeeshan A. Rana; Aerodynamic and Structural Design of a 2022 Formula One Front Wing Assembly. [CrossRef]

- Jiashu Xu; Thermodynamic evaluation of 2026 Power Unit technical regulation changes in Formula 1. [CrossRef]

- Tomasz Kalociński, Lukasz Rymaniak, Pawel Fuc; Powertrain technology transfer between F1 and the automotive industry based on Mercedes-Benz. [CrossRef]

- moh Ime Ekanem, Aniekan Essienubong Ikpe; EVOLUTION OF FORMULA ONE (F1) MOTORSPORTS AND ITS TOP-NOTCH ADVANCEMENT IN ENGINEERING INNOVATIONS ACROSS THE RACING INDUSTRY, (ResearchGate).

- James Brown, Neville A Stanton, Kirsten M A Revell; The Evolution of Steering Wheel Design in Motorsport,. [CrossRef]

- Zhihao Zhang; Study on aerodynamic development in Formula One racing. [CrossRef]

- Koichi Konishi; Development of Honda Gears for Formula One Gearbox; [F1-SP2_17e].

- TOTALSIM: Secrets of Formula 1 Part 2 – Importance of Aerodynamics, June 14,2016 (link).

- Formula 1® tyre compounds; Pirelli Official website for tyres.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).