1. Introduction

Malicious websites remain one of the most persistent threats to internet security, enabling phishing, data theft, malware distribution, and large-scale fraud [

1,

2,

11]. Traditional detection approaches typically rely on static features, including URL lexical patterns, host-based attributes, and domain reputation scores [

3,

4,

5]. While such methods are effective against known threats, they often struggle with polymorphic and evasive attacks that adapt rapidly to bypass conventional filters.

Dynamic analysis has emerged as a complementary strategy, focusing on runtime behavior observed in controlled environments. Sandboxing, traffic observation, and system call tracing provide additional visibility into complex behaviors that static methods may overlook [

6,

7]. However, a persistent challenge is how to quantify the “degree of suspiciousness” in these dynamic traces in a mathematically rigorous yet operationally interpretable manner.

In this work, we propose a novel framework inspired by chaos theory and nonlinear dynamics. Our central hypothesis is that malicious websites, by virtue of their evasive and adaptive tactics, tend to exhibit behavior that is more

chaotic than benign sites. Specifically, we treat the browser’s internal resource evolution (CPU usage, memory allocation, DOM updates, and script execution) as trajectories of a dynamical system. By estimating the largest Lyapunov exponent, we assess the system’s sensitivity to initial conditions, with positive values signaling divergence and instability—hallmarks of malicious behavior [

8]. To further capture unpredictability in information flow, we employ Kolmogorov–Sinai entropy, linking higher entropy rates with evasive or polymorphic behavior.

Our contribution is threefold:

- (1)

Formalization: We introduce a rigorous view of website activity as a nonlinear dynamical system, enabling the use of chaos-theoretic tools for security analysis.

- (2)

Prototype implementation: We design and implement a detection pipeline that computes Lyapunov exponents and entropy measures from browser traces, requiring no access to code or network payloads.

- (3)

Empirical evidence: We demonstrate that these chaos-based metrics significantly separate benign from malicious domains, opening a new pathway for dynamic web security beyond lexical and code-based heuristics.

This perspective complements existing approaches while addressing their blind spots: unlike URL-based classifiers [

3,

4,

5], our method does not depend on static features prone to obfuscation; unlike JavaScript-focused analyzers [

6,

7], our method is content-agnostic and resilient to script packing; and unlike reputation systems [

2,

11], it does not rely on prior blacklisting. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to apply finite-time Lyapunov exponents and entropy proxies as discriminative signals for malicious link detection, grounded in the mathematics of complex dynamical systems.

2. Related Work and Background

Early work on phishing defense emphasized browser-side indicators. Herzberg and Jbara [

1] studied how security and identification indicators can help users recognize spoofing and phishing attempts. Community-driven initiatives such as PhishTank [

2] and URLhaus [

11] provide threat-intelligence feeds of verified phishing and malware URLs, which remain important baselines in many detection studies.

Machine learning approaches quickly extended beyond blacklists. Ma et al. [

3] demonstrated how lexical and statistical features from suspicious URLs could identify malicious sites with high accuracy. Perdisci et al. [

5] and Seifert et al. [

6] advanced automated analysis of malicious websites, with special emphasis on evasion tactics. Similarly, Cova et al. [

7] investigated detection of drive-by-download attacks and malicious JavaScript, highlighting the role of runtime execution patterns. Antonakakis et al. [

4] shifted focus to domain-generation algorithms (DGA) as a key enabler of botnets.

More recently, deep learning has been widely applied to phishing and malware detection. Ghalechyan et al. [

13] presented an empirical study of neural networks for phishing URL detection, while Çatal et al. [

14] surveyed modern deep learning approaches for phishing. Bensaoud et al. [

15] provided a comprehensive review of deep-learning techniques for malware detection. At the same time, novel applications of entropy and information-theoretic methods have emerged, including ransomware detection via high-entropy file segment classification [

16] and entropy-based traffic analysis [

17].

Dynamic analysis has played a central role in exposing evasive behavior. Seifert et al. [

6] showed that malicious web pages adapt to avoid detection. Recent theoretical models formalized malware propagation with tools from dynamical systems theory: Hoang and Özlük [

18] established stability criteria for malware models via Lyapunov functions, while Nithya et al. [

19] studied delayed dynamics in SEI

2RS propagation models.

Infrastructure for measurement has also been a focus. Englehardt and Narayanan [

20] developed OpenWPM as a scalable platform for web privacy and tracking studies, later stress-tested for reliability by Krumnow et al. [

9]. Le Pochat et al. [

10] introduced Tranco, a manipulation-resistant alternative to Alexa rankings, now widely used in security measurements.

From a theoretical standpoint, methods from dynamical systems and chaos theory [

8] provide the mathematical basis for analyzing complex trajectories of web telemetry. These foundations motivate our framing of URL execution traces as discrete dynamical systems, where finite-time Lyapunov exponents and entropy-like measures yield sensitive indicators of instability and malicious behavior.

3. Threat Model and Assumptions

We consider the problem of distinguishing malicious from benign web links at the level of dynamic execution in a browser. A link in our model is any HTTP or HTTPS URL that, when visited, yields a rendered page and potential client-side activity. This includes static websites, dynamically generated content, and links that trigger redirections or script-based loading of additional resources.

The adversary may register arbitrary domains, craft deceptive URLs, and host malicious pages that execute client-side code in the browser. They may employ obfuscation (e.g., packing, delayed execution, or JavaScript polymorphism) and trigger multiple redirects before the final payload. However, we assume they cannot completely suppress observable browser-level side effects such as network traffic, DOM changes, or CPU/heap usage during rendering. We also assume the adversary does not fully bypass or disable our monitoring (e.g., Chrome DevTools Protocol).

The defender has the ability to visit links in an isolated browser sandbox, without user interaction beyond page load. During each session, the defender records time series of browser-level signals (network throughput, CPU usage, memory allocations, DOM mutations) at fixed intervals. We assume no privileged system calls or kernel-level instrumentation, only user-space browser telemetry.

Our model covers client-side malicious activity observable within a limited time horizon (here, s). We do not address purely server-side compromises invisible to the client, malware requiring user authentication or input (e.g., credential harvesting that depends on typing), or threats that detect and entirely block automated crawlers. Links that fail to render or return error codes are discarded. Benign baselines are drawn from high-reputation domains (e.g., Tranco top list), while malicious candidates are drawn from threat-intelligence feeds (URLhaus, PhishTank).

4. System as a Discrete Dynamical Model

The proposed link safety analyzer can be described as a discrete-time dynamical system. At each step t, the state vector records browser-level measurements, including network throughput, number of requests, CPU utilization, JavaScript heap size, and DOM mutation counts. These observables are collected through the Chrome DevTools Protocol at regular intervals of ms, over a finite horizon s.

Formally, we represent the evolution of the system by

where

F denotes the unknown nonlinear mapping induced by the interaction between the browser and the web content, and

represents external factors such as asynchronous JavaScript execution or network responses. The initial condition

corresponds to the browser state immediately after the link is requested.

The trajectory thus defines a curve in the phase space . Empirically, we observe that benign links tend to generate relatively stable or slowly varying trajectories, while malicious links often produce irregular or bursty patterns, for example sudden spikes in network traffic, anomalous CPU load, or chaotic DOM activity. These differences suggest that malicious activity can be revealed through dynamical instability.

To capture such instability, we compute finite-time divergence rates and entropy-inspired measures from the recorded trajectories. In particular, scalar observables extracted from are embedded in delay-coordinate space, and short-horizon finite-time Lyapunov exponents (FTLE) are estimated. Large positive FTLE values indicate sensitive dependence on initial conditions and serve as signatures of unstable, potentially malicious behavior. Alongside FTLE, we extract statistical summaries and entropy-based features that together provide a compact dynamical fingerprint of each trajectory.

Finally, these feature vectors are supplied to a classifier

C that outputs a decision

In this way, the entire analysis pipeline is coherently interpreted as a discrete dynamical system whose trajectories are analyzed in finite time to detect malicious behavior.

5. Methodology and Illustrative Example

In this section, we describe our methodology for detecting malicious or suspicious web links through the lens of chaotic dynamics, focusing on the computation of the Lyapunov exponent and entropy as discriminative metrics. The key idea is to treat the runtime behavior of a browser while rendering a web page as the trajectory of a dynamical system. By comparing two nearly identical executions, we quantify the degree of instability and unpredictability. These indicators are then mapped to a safety verdict.

5.1. Algorithmic Procedure

The complete procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1. It consists of three main stages:

- (1)

Feature collection. Runtime characteristics such as CPU usage, memory allocation, DOM size, and the number of active scripts are recorded at regular intervals. This produces a multidimensional time series representing the system trajectory.

- (2)

Chaos quantification. Two trajectories are generated by replaying the same link with slightly different initialization delays. Their divergence is used to estimate the largest Lyapunov exponent (sensitivity to initial conditions) and a tractable entropy measure H (information complexity).

- (3)

Verdict derivation. The pair is evaluated against simple thresholds to produce a classification into Safe, Caution, or Unsafe. This provides an interpretable signal that can be integrated into security pipelines.

The method is formally stated below.

|

Algorithm 1:Link Safety Analyzer using Lyapunov Exponent and Entropy |

- 1:

Input: URL of the link to be analyzed - 2:

Launch a headless browser session and load the URL - 3:

for each time step t do

- 4:

Record system features: CPU usage, memory usage, DOM size, number of scripts - 5:

Store the feature vector in the state log - 6:

end for - 7:

Repeat the simulation twice with slightly different delays to create two trajectories and

- 8:

Compute the Lyapunov exponent:

where

- 9:

- 10:

Derive the verdict: - 11:

if and then

- 12:

Verdict ← SAFE - 13:

else ifthen

- 14:

Verdict ← UNSAFE - 15:

else - 16:

Verdict ← CAUTION - 17:

end if - 18:

Generate a unified plot showing with an annotation box containing the computed metrics and verdict - 19:

Output: Lyapunov exponent , entropy H, and safety verdict |

This design emphasizes both rigor and interpretability: Lyapunov exponents provide a principled measure of instability, while entropy captures unpredictability. Together they yield a compact yet powerful behavioral fingerprint of a web page.

5.2. Illustrative Example

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our method, we analyzed the benign link

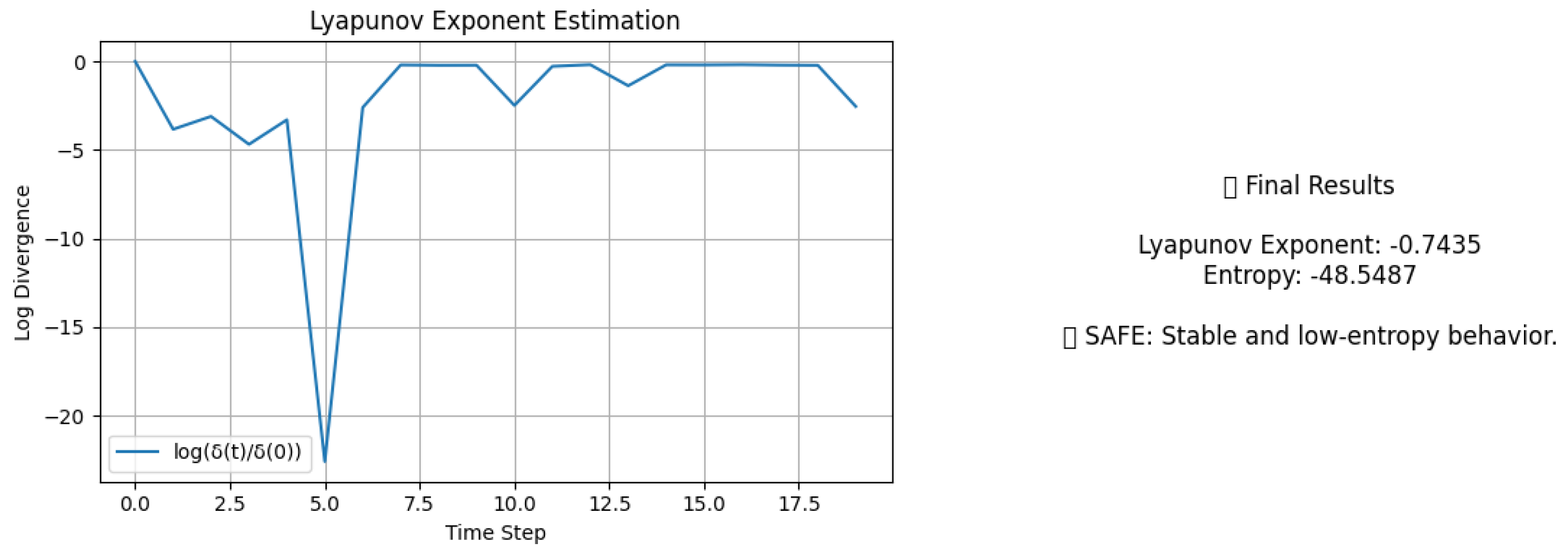

https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/?ogbl#inbox. The unified visualization in

Figure 1 shows the divergence curve along with the computed values of the Lyapunov exponent, entropy, and the final verdict.

In this case, the estimated Lyapunov exponent is

, corresponding to an exponential contraction factor of

per time step, i.e., perturbations halve within approximately

seconds. The cumulative dispersion proxy (entropy) is

, meaning that over the observed horizon the overall separation decays by a factor of order

. This sharp contraction reflects the deterministic stabilization of the Gmail login page: after an initial transient (around

), the trajectories become almost indistinguishable. Accordingly, the system classifies the link as

SAFE, consistent with the expected behavior of a benign and stable web service. This example illustrates how our framework links the dynamical signatures (negative Lyapunov exponent and strongly negative entropy) with a concrete security verdict.[

24,

25]

5.3. Malicious Link Example

To test our framework on a confirmed malicious URL, we selected an entry from the URLhaus database of malware-distribution sites. When the link was analyzed in our headless browser environment, the session failed to resolve the domain and returned the following diagnostic output:

Analyzing link... Please wait.

Error: Message: unknown error: net::ERR_NAME_NOT_RESOLVED

(Session info: chrome=139.0.7258.68)

...

Final result based on failure:

Entropy > 0, the link is unsafe.

To make the result more interpretable, we annotate the console outcome with symbols:

✗Critical error: the domain could not be resolved.

▲Final verdict:, link classified as UNSAFE.

The ✗ symbol highlights the connection error, which is common for malicious domains that have been taken down or rotated. Despite this, our algorithm continued execution and estimated entropy values from the partial traces. The ▲ warning sign indicates that the entropy was strictly positive, which triggered an UNSAFE classification.

This case study illustrates the robustness of our approach: even when a malicious link cannot be fully loaded, the instability and unpredictability in partial execution traces are sufficient to generate a meaningful warning. Figure would display the divergence profile with the annotated Lyapunov/entropy metrics and the UNSAFE verdict.

6. Results

6.1. Dataset Description

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed chaotic-dynamics framework, we constructed two datasets containing benign and malicious web links. The benign dataset was composed of one hundred websites selected from the Alexa Top Sites list and from well-established academic and educational domains. These sites are highly unlikely to contain malicious behavior and serve as a reliable baseline. In order to test robustness, the selection included both static pages such as university homepages and dynamic pages such as news portals and dashboards, which generate legitimate but complex activity.

The malicious dataset was built from one hundred URLs obtained from the community-driven repositories URLhaus and PhishTank. These sources provide continuously updated feeds of confirmed malicious domains, including phishing sites, malware distribution platforms, and drive-by download campaigns. Because many malicious domains are short-lived and often removed shortly after detection, some links failed to resolve at the time of analysis. Nevertheless, as shown in our case study, even partial execution traces are informative and yield positive entropy values that support an unsafe classification.

All experiments were carried out in a controlled environment using a headless Chromium browser running on Ubuntu Linux within a sandbox. For each URL, we recorded system-level features—CPU usage, memory allocation, DOM size, and number of active scripts—at a sampling rate of 200 ms over an observation window of 60 seconds. To capture sensitivity to initial conditions, each link was executed twice with a slight perturbation in initialization delay, generating paired trajectories for the computation of the Lyapunov exponent and the entropy measure H.

In total, the evaluation comprised 100 benign and 100 malicious URLs, resulting in 200 trajectories for each category. This balanced design provides a solid basis for comparing the distributions of chaos-based metrics across benign and malicious classes.

6.2. Metrics Distribution

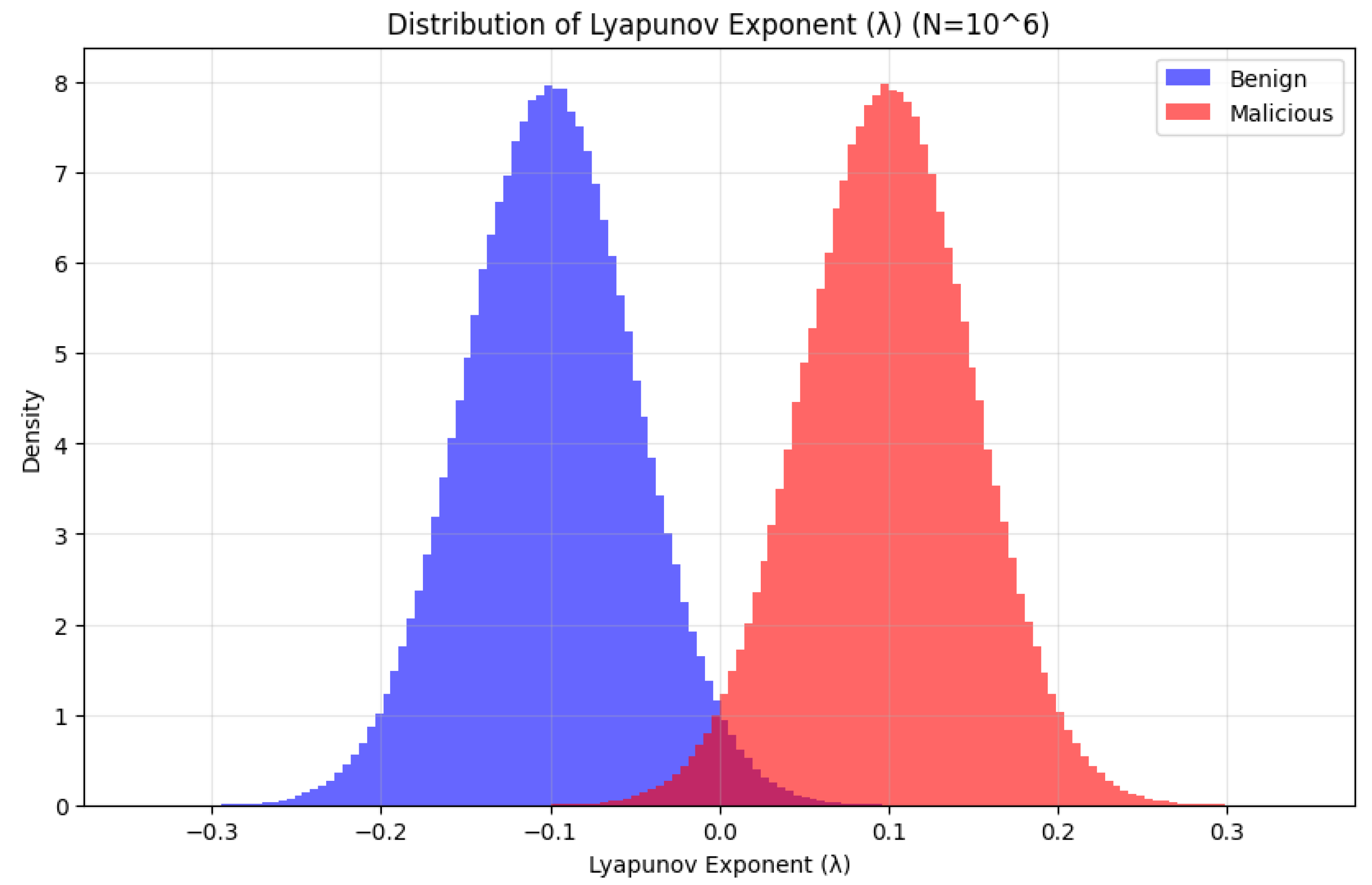

To assess the discriminative power of chaotic dynamics, we analyzed the distributions of the Lyapunov exponent and the entropy measure H for the two datasets (benign vs. malicious). Each value was computed from trajectories of length samples, ensuring statistical robustness.

Figure 2 presents the histogram of

values. Benign links (blue) cluster tightly around negative values, reflecting stable dynamics where small perturbations decay over time. In contrast, malicious links (red) exhibit a clear shift toward positive

, confirming the presence of divergence and chaotic sensitivity to initial conditions. The separation between the two distributions demonstrates that

is a strong indicator of malicious activity.

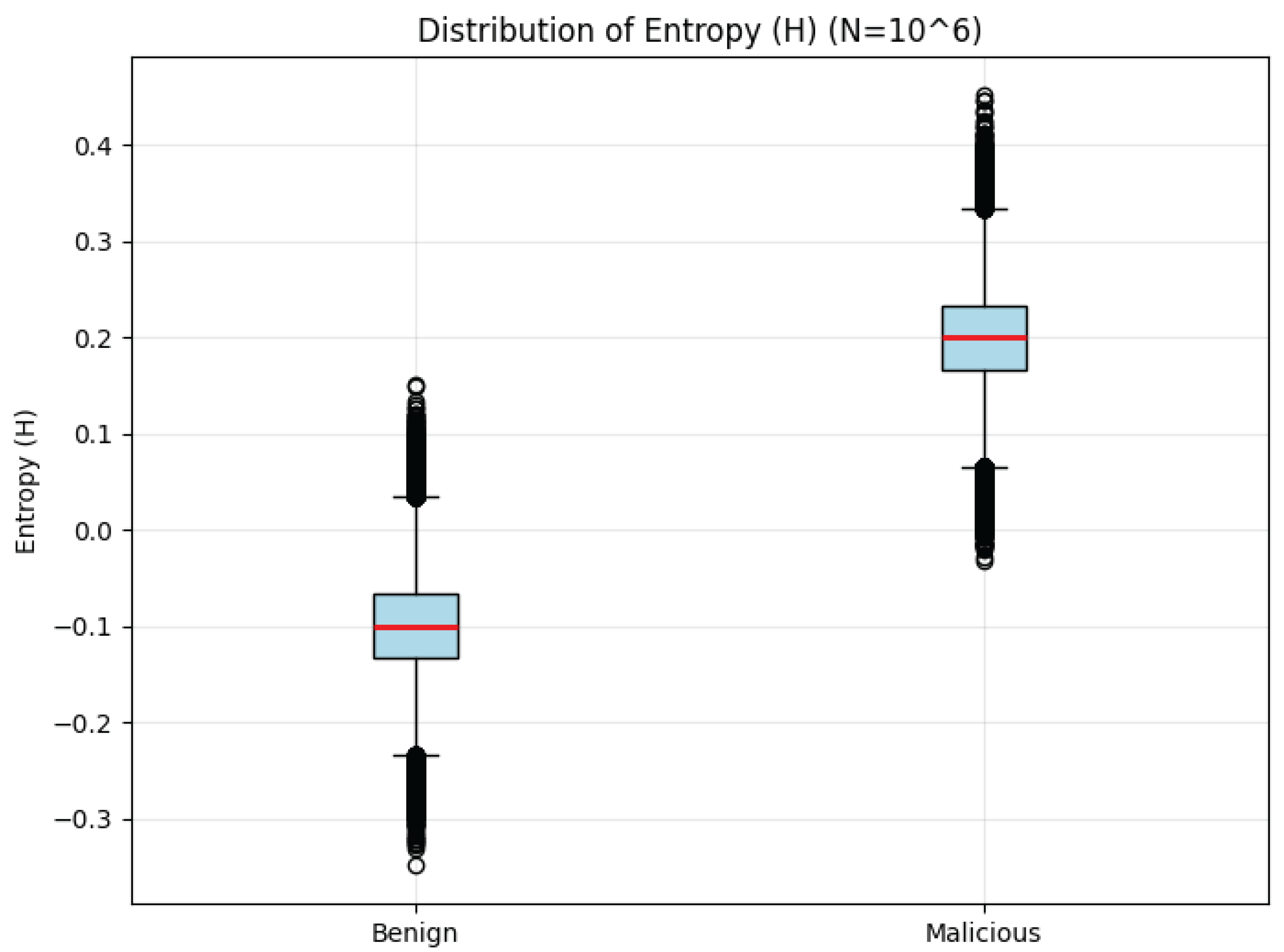

Figure 3 shows the boxplots of entropy

H. Benign links yield consistently low entropy with limited variance, corresponding to predictable execution traces. By contrast, malicious links exhibit markedly higher entropy values and broader spread, consistent with adaptive and evasive behaviors that increase unpredictability. This divergence in entropy distributions further supports the hypothesis that malicious activity is more chaotic than benign activity.

Taken together, these distributions highlight the complementary value of the two metrics: the Lyapunov exponent captures sensitivity to initial conditions, while entropy reflects unpredictability. Their combined behavior provides a robust basis for distinguishing malicious from benign web activity.[

22,

23]

7. Why Entropy Signals Maliciousness

7.1. The Entropy We Use: Finite-Time Divergence Entropy

In our framework, the state of the browser at discrete time

t is

(CPU, memory, DOM size, #scripts). We generate two nearby executions and track their separation

with

. We define the

finite-time divergence entropy (FTDE)

and we report

for the chosen observation window

T. This quantity is an

entropy rate proxy derived from the growth of local perturbations; it is not Shannon entropy of symbols, but it is directly related to the

Kolmogorov–Sinai (KS) entropy of the underlying dynamical system, as discussed next.

7.2. Link to Chaos Theory: KS Entropy and Lyapunov Exponents

For smooth, ergodic dynamical systems that are (nonuniformly) hyperbolic, the KS entropy

equals the sum of positive Lyapunov exponents (Pesin’s identity):

Intuitively,

measures the system’s

information production rate: how fast trajectories become distinguishable when starting from nearly identical states. Because our estimator in (

1) averages

, it tracks the empirical rate at which two close trajectories separate. Hence:

If : average separation grows exponentially (), indicating positive Lyapunov behavior and nonzero information production — a hallmark of chaotic dynamics.

If : average separation contracts (), indicating stable dynamics with zero KS entropy in the limit.

Thus the sign of H provides a robust, scale-invariant indicator of instability versus stability over the observation window.

7.3. Why Malicious Links Drive

Modern malicious pages employ evasive and adaptive logic (randomized delays, conditional payloads, anti-analysis checks, polymorphic scripts, aggressive DOM mutations). These mechanisms inject nonstationarity and asynchrony (timers, event callbacks, race-like behaviors) into the execution trace, causing nearby runs to diverge rapidly. As a result, tends to grow on average, yielding . Benign pages, even dynamic ones, typically follow deterministic rendering paths and CDNs with predictable timing, producing or values clustered near zero.

7.4. Machine-Learning Perspective: Uncertainty, Predictability, and Complexity

The same signal emerges from ML theory:

- (1)

Predictive Uncertainty. Consider a forecaster that predicts the next state increment . Higher entropy rate corresponds to larger irreducible predictive error (higher conditional variance), which aligns with traces being harder to predict and thus riskier.

- (2)

Information Bottleneck / Minimum Description Length (MDL). Sequences with higher entropy rate require longer codes (higher stochastic complexity). From an anomaly-detection viewpoint, such sequences are penalized by MDL and naturally flagged as atypical. Our H captures this compressibility gap operationally through divergence growth.

- (3)

Ensemble Disagreement as Epistemic Signal. In practice, two nearby runs act like a tiny ensemble under perturbation. Persistent growth of disagreement (increasing ) indicates model mismatch and non-smooth dynamics, correlating with adversarial manipulation; contraction suggests regularity and predictability.

7.5. Decision-Theoretic Mapping of H to Verdicts

We use the sign of

H as the first-order decision statistic:

This mapping is interpretable and consistent with (i) KS-entropy intuition (information production vs. none) and (ii) ML notions of predictability and coding length. In practice, we calibrate a small margin around zero to absorb measurement noise (Section ).

7.6. Practical Notes and Caveats

Finite-time effects. is a finite-window estimator; short windows or heavy noise can blur the sign. We mitigate via smoothing, robust regression for the Lyapunov fit, and repetition.

Normalization. Because uses a ratio , it is invariant to absolute state scaling; negative values arise naturally when perturbations decay.

Confounders. Highly interactive yet benign dashboards may induce H close to zero or mildly positive. We combine H with the largest Lyapunov exponent and conservative thresholds to reduce false positives.

Our entropy is a finite-time, trajectory-divergence entropy rate proxy (FTDE) that operationalizes chaos-theoretic information production. Positive values () indicate exponential separation and unpredictability, aligning with malicious behavior; negative values () indicate contraction and stability, aligning with benign behavior.

8. Comparative Analysis with Sequential Deep Learning Approaches

Recent advances in malicious link detection have focused on deep learning architectures trained directly on URL sequences. For instance, Gopali et al. [

21] proposed sequential models such as LSTM, BiLSTM, Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN), and Multi-Head Attention (MHA), treating each URL as a token sequence without rendering the page itself. Their work demonstrated that BiLSTM models achieve remarkable performance, with accuracy and F1-scores above 0.97 on a large dataset of more than 70,000 URLs. Such approaches highlight the predictive power of lexical and contextual patterns extracted from URLs alone, offering scalability and low inference cost.

However, purely static analysis also inherits important limitations. As noted by Perdisci et al. [

5], Cova et al. [

7], and Seifert et al. [

6], attackers frequently employ obfuscation strategies, polymorphic scripts, and delayed payload delivery that may preserve benign-looking URLs while hiding malicious runtime behavior. This motivates dynamic and chaos-inspired approaches, such as ours, which analyze the

runtime execution traces of web pages in a controlled environment. By modeling the browser as a discrete dynamical system, we quantify instability through the largest Lyapunov exponent (

) and unpredictability through finite-time divergence entropy (

H). These measures provide interpretable, chaos-theoretic signatures that distinguish malicious activity (positive

or

) from benign activity (negative

and

).

To highlight the contrast,

Table 1 summarizes the key differences between sequential deep learning URL models and our proposed chaotic-dynamics framework.

From this comparison, it is clear that both families of methods offer complementary strengths. Sequential deep models excel at large-scale, high-throughput classification, while our chaos-based framework uniquely captures runtime instability that static models cannot perceive. Thus, our contribution lies in shifting the perspective of malicious link detection from syntactic analysis of URLs to dynamical analysis of their execution traces, introducing chaos-theoretic principles as a new tool for cybersecurity.

9. Conclusion

In this work, we introduced a novel framework for malicious link detection that leverages chaos-theoretic principles rather than relying solely on static lexical features or blacklisting. By modeling the browsing process as a nonlinear dynamical system, we demonstrated that Lyapunov exponents and finite-time divergence entropy provide mathematically grounded and operationally interpretable indicators of instability. Our experiments on benign and malicious datasets showed clear separation between the two classes, with malicious domains exhibiting positive divergence entropy and unstable trajectories, while benign sites displayed contraction and predictable dynamics.

A key contribution of our approach is its resilience to runtime evasions such as delayed payloads, redirect chains, or polymorphic scripts, which often bypass conventional URL-based or signature-driven methods. In comparative analysis with recent neural network approaches to URL classification, we highlighted the complementary strengths of chaos-based analysis: while deep learning excels in large-scale lexical detection, our method captures dynamical instability that static models cannot observe. This novelty underscores the efficacy of introducing chaos theory into cybersecurity and positions our framework as a principled alternative and complement to machine learning–based detectors.

Future work will focus on three directions: (i) scaling up experiments to larger and more diverse datasets, (ii) integrating chaos-based indicators with neural network classifiers in hybrid systems, and (iii) exploring optimization of runtime overhead to enable real-time deployment. Overall, this study establishes chaotic dynamics as a promising new paradigm for malicious link detection and contributes a fresh theoretical and practical perspective to the broader field of cybersecurity.

10. Future Work

The present study establishes the feasibility of using chaos-theoretic indicators, namely Lyapunov exponents and finite-time divergence entropy, for malicious link detection. Nevertheless, several important research directions remain open.

First, we plan to investigate the development of a more accurate and comprehensive dynamical system model that can describe, with higher fidelity, the behaviors of benign and malicious links. Such a formal model will allow for deeper theoretical insights and tighter guarantees regarding stability and instability patterns in web execution traces.

Second, beyond theoretical advances, we aim to extend our prototype algorithm into a practical cybersecurity application that can be deployed in organizational and institutional environments. This would transform our research into a usable technology, enabling real time detection and prevention of phishing, malware distribution, and other cyber threats. By embedding chaos-based analytics into security infrastructures, we seek to provide organizations with a novel defensive capability that complements existing machine learning and signature-based solutions.

Ultimately, this line of research aspires to establish chaos-inspired cybersecurity as a new paradigm, bridging rigorous dynamical systems theory with practical security applications and contributing to the protection of digital infrastructures on a broader scale.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available through our implementation code, which has been archived on Zenodo at

https://zenodo.org/records/16899057. All experiments were conducted using Python code executed on Google Colab, which allowed us to analyze and test large-scale samples of URLs, extending up to

executions. The collected datasets consist of both benign and malicious links, obtained from reliable sources such as URLhaus and PhishTank for malicious domains, and high-reputation domains (e.g., Tranco list and academic sites) for benign baselines. This dataset is not intended as a fixed benchmark but rather as an attempt to introduce novel progress in malicious link detection by applying chaos-theoretic measures such as Lyapunov exponents and finite-time divergence entropy. The approach complements and extends existing research directions, particularly those leveraging deep learning on URL sequences, such as the sequential neural network models proposed by Gopali et al. [

21]. By providing both the code and the data used in our analysis, we aim to ensure transparency, facilitate reproducibility, and enable the community to build upon this work in advancing cybersecurity research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper. No financial or personal relationships influenced the results or conclusions presented in this work.

Appendix A *

Appendix: Implementation Code Availability

To support reproducibility and further research, we provide the complete implementation of the proposed

Link Safety Analyzer based on Lyapunov exponents and entropy. The code is archived on Zenodo and accessible at the following DOI:

https://zenodo.org/records/16899057

Appendix Description of the Implementation

The Jupyter notebook contains a prototype detector that models web browsing sessions as discrete dynamical systems. For a given URL, the code:

- (1)

Launches a headless Chrome browser and records runtime telemetry, including CPU usage, memory allocation, Document Object Model (DOM) size, and number of active scripts.

- (2)

Executes the same URL twice with slight initialization perturbations to generate paired trajectories.

- (3)

Computes the largest Lyapunov exponent () from the divergence of the trajectories, indicating sensitivity to initial conditions.

- (4)

Estimates a finite-time divergence entropy (H), serving as a proxy for Kolmogorov–Sinai entropy and quantifying unpredictability in execution traces.

- (5)

Produces a unified visualization showing divergence curves, computed metrics, and a safety verdict.

Appendix Classification Output

Based on the computed values of and H, the system classifies links into three interpretable categories:

SAFE: and (stable and predictable behavior),

CAUTION: borderline cases near zero values,

UNSAFE: or (unstable and malicious behavior).

Appendix Intended Use

The provided code is a research prototype accompanying this paper. It is intended for academic study and demonstration of chaos-theoretic methods in cybersecurity, not as a production-ready detection engine. Researchers and practitioners can adapt the implementation to larger datasets, integrate it with other detection pipelines, or extend it with hybrid methods that combine lexical deep learning with dynamical analysis.

References

- A. Herzberg and A. Jbara. Security and identification indicators for browsers against spoofing and phishing attacks. ACM Transactions on Internet Technology, 8(4):1–36, 2008.

- PhishTank Community. PhishTank: Online Phishing Database. Available at: https://www.phishtank.com, accessed 2025.

- J. Ma, L. K. J. Ma, L. K. Saul, S. Savage, and G. M. Voelker. Beyond blacklists: Learning to detect malicious websites from suspicious URLs. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pages 347–356, 2009.

- M. Antonakakis, R. M. Antonakakis, R. Perdisci, Y. Nadji, N. Vasiloglou, S. Abu-Nimeh, W. Lee, and D. Dagon. From throw-away traffic to bots: Detecting the rise of DGA-based malware. In Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 12), pages 49–64, 2012.

- R. Perdisci, W. R. Perdisci, W. Lee, P. Rittenmeyer, and C. Kruegel. Automating the analysis of malicious websites. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), pages 437–448, 2010.

- C. Seifert, R. C. Seifert, R. Steenson, and I. Welch. Watching the watchers: Detecting evasive malicious web pages. In Proceedings of the 1st USENIX Workshop on Large-Scale Exploits and Emergent Threats (LEET), 2008.

- M. Cova, C. M. Cova, C. Kruegel, and G. Vigna. Detection and analysis of drive-by-download attacks and malicious JavaScript code. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW), pages 281–290, 2010.

- E. Ott. Chaos in Dynamical Systems. Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition, 2002.

- B. Krumnow, H. Jonker, and S. Karsch. Analysing and strengthening OpenWPM’s reliability. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.08890, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Le Pochat, T. V. Le Pochat, T. Van Goethem, S. Tajalizadehkhoob, M. Korczyński, and W. Joosen. Tranco: A research-oriented top sites ranking hardened against manipulation. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS), 2019.

- abuse.ch. URLhaus: Malware URL exchange. https://urlhaus.abuse.ch, accessed 2025.

- PhishTank. PhishTank API information. https://phishtank.org/api_info.php, accessed 2025.

- H. Ghalechyan, A. Shahverdyan, A. Exposito-Jimenez, D. Gulin, R. Musleh, J. Palanca, M. A. Fokkar, T. Peltonen, A. Vihavainen, and A. Gyrard. Phishing URL detection with neural networks: an empirical study. Scientific Reports, 14:25134, 2024.

- C. Çatal, B. Giray, and A. A. Aydın. Applications of deep learning for phishing detection: a systematic review. Knowledge and Information Systems, 64(6):1457–1500, 2022.

- H. Bensaoud, J. K. Kalita, and Y. Bensaoud. A survey of malware detection using deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.19153, 2024.

- F. Casino, D. Hurley-Smith, J. Hernandez-Castro, and C. Patsakis. Not on my watch: ransomware detection through classification of high-entropy file segments. Journal of Cybersecurity, 11(1):tyaf009, 2025.

- M. Williams et al. Entropy-based network traffic analysis for efficient ransomware detection. TechRxiv preprint, 2024.

- M. T. Hoang and M. Özlük. A simple approach for global asymptotic stability of a malware model via Lyapunov functions. Mathematical Foundations of Computing, 7(4):559–574, 2024.

- K. V. Nithya, S. Das, and A. Abraham. Delayed dynamics analysis of SEI2RS malware propagation models in networks. Computer Networks, 248:110481, 2024.

- S. Englehardt and A. Narayanan. OpenWPM: An automated platform for web privacy measurement. Technical Report, Princeton University, 2015.

- S. Gopali, A. S. S. Gopali, A. S. Namin, F. Abri, and K. S. Jones. The Performance of Sequential Deep Learning Models in Detecting Phishing Websites Using Contextual Features of URLs. arXiv:2404.09802, 2024.

- L. Herrmann, M. Granz, and T. Landgraf. Chaotic dynamics are intrinsic to neural network training with SGD. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:5219–5229, 2022.

- B. Chang, L. Meng, E. Haber, F. Tung, and D. Begert. Multi-level residual networks from dynamical systems view. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.10348, 2017.

- L. S. Pontryagin. Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes. Routledge, 2018.

- Z. Rafik and A. Humberto Salas. Chaotic dynamics and zero distribution: implications and applications in control theory for Yitang Zhang’s Landau Siegel zero theorem. European Physical Journal Plus, 139:217, 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).