Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Summary

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Pilot Studies

1.3. Final Version of the POSHA–S

2. Data Description

2.1. POSHA–S Database Overview and Standard Scoring

2.2. Data Conversions

2.3. Using the POSHA–S Database

3. Methods

3.1. POSHA–S Psychometric and Practical Characteristics

3.2. Obtaining Data from IPATHA Partners

3.3. Alternate Access to the Database and Related Materials

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frigerio-Domingues, C.; Drayna, D. Genetic contributions to stuttering: the current evidence. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine 2017, 5, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, W.H.; DiLollo, A. Clinical Decision Making in Fluency Disorders. 5th ed. Plural Publishing, San Diego, CA, USA 2025.

- Johnson, W. ; Associates. The Onset of Stuttering: Research Finding and Implications; University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1959.

- St. Louis K.O. Predicting attitudes toward stuttering from an international database. J Commun Disord. 2024, 112, 106457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilby, J.M.; Byrnes, M.; Meagher, E.L.; Yaruss, J.S. The impact of stuttering on adults who stutter and their partners. Jl Fluen Disord, 38, 2013), 14-29. [CrossRef]

- Irani, F.; Abdalla, F.; Gabel, R. Arab and American teachers’ attitudes toward people who stutter: A comparative study. Contemp Issues Commun Sci Disord 2012, 39, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, T.W.; St. Louis K.O. Changing adolescent attitudes toward stuttering. J Fluen Disord 2011, 36, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yairi, E.; Williams, D.E. Speech clinician’s stereotypes of elementary-school boys who stutter. J Commun Disord 1970, 3, 161–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, M.E. ; St. Louis K.O.; Nakışcı E.; Özdemir S. A comparison of attitudes towards stuttering of non-stuttering preschoolers in the United States and Turkey. S Af J Commun Disord 2017, 64, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Korean speech–language pathologists’ attitudes toward stuttering according to clinical experiences. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2014, 49, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, M. P. , Cheyne, M. R., & Rosen, A. L. Self-stigma of stuttering: Implications for communicative participation and mental health. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2023, 66, 3328–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Penguin Random House, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA 1963.

- Woods, C.L.; Williams, D.E. Traits attributed to stuttering and normally fluent males. J Sp Hear Res 1976, 19, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O. Epidemiology of public attitudes toward stuttering. In Stuttering meets stereotype, stigma, and discrimination: An overview of attitude research; Editor St. Louis K.O.; West Virginia University Press, Morgantown, WV, USA 2015. pp. 7–42.

- Bohner, G.; Dickel, N. Attitudes and attitude change. Annual Review Psychol 2011, 62, 391–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis, K. O. The Public Opinion Survey of Human Attributes-Stuttering (POSHA–S): Summary framework and empirical comparisons. J Fluen Disord 2011, 36, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis, K.O.; Lubker, B.B.; Yaruss, J.S.; Adkins, T.A.; Pill, J. C. St. Louis, K.O.; Lubker B.B.; Yaruss J.S.; Adkins, T.A.; Pill, J. C. Development of a prototype questionnaire to survey public attitudes toward stuttering: Principles and methodologies in the first prototype. Internet J of Epidemiol 2007, 5. [Google Scholar]

- St. Louis K.O. Research and development on a public attitude instrument for stuttering. J Commun Disord 2012, 45, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St. Louis K.O.; Andrade C.R.F.; Georgieva D.; Troudt F.O. Experience and personal report about an international cooperation research—Brazil, Bulgaria and Turkey—Attitudes toward stuttering. Pró-Fono Revista de Atualização Cientifica 2005, 17, 413–416. [Google Scholar]

- St. Louis K.O. POSHA–S Database; Populore, Morgantown, WV, USA 2024. Available from https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/POSHAS-Database-11631862.

- St. Louis, K. O. St. Louis, K. O., Irani, F., Gabel, R. M., Hughes, S., Langevin, M., Rodriguez, M., Scott, K. S., & Weidner, M. E. (2017). Evidence-based guidelines for being supportive of people who stutter in North America. Journal of Fluency Disorders, /: https. [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O. Data Entry & Graphs for One Group or Sample; Populore, Morgantown, WV, USA 2024. Available from https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/POSHAS-Data-Entry-Graphs-for-One-Group-or-Sample-7759598.

- St. Louis K.O. Data Entry & Graphs for Two Groups or Samples; Populore, Available from https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/POSHAS-Data-Entry-Graphs-for-One-Group-or-Sample-7759598Morgantown, WV, USA 2024.

- Arnold, H.S.; Li, J.; Goltl, K. Beliefs of teachers versus non-teachers toward people who stutter. J Fluen Disord 2015, 43, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Arnold, H. Reactions of teachers versus non-teachers toward people who stutter. J Commun Disord 2015. 56, 8–18. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, H.S.; Li, J.; Beste-Guldborg, A. Reactions of protective services workers towards people who stutter. J Fluen Disord 2016, 50, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, H.S.; Li, J. Association between beliefs about and reactions toward people who stutter. J Fluen Disord 2016, 47, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes S,; Junuzović-Žunić L. ; Mostafa E.; Weidner M, Özdemir R.S.; Daniels D, Glover H.L.; Göksu A.; Konrot A.; & St. Louis K.O. Mothers’ and fathers’ attitudes toward stuttering in the Middle East compared to Europe and North America. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2024, 59, 354–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O. Comparing and predicting public attitudes toward stuttering, obesity, and mental illness. Amer J Sp-Lang Pathol 2020, 29, 2023–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O.; Roberts P.M. Measuring attitudes toward stuttering: English-to-French translations in Canada and Cameroon. J Commun Disord 2010, 43, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O.; Węsierska K.; Przepiórka A.; Błachnio A.; Beucher C.; Abdalla F.; Flynn T.; Reichel I.; Beste-Guldborg A.; Junuzović-Žunić L.; Gottwald S.; Hartley J.; Eisert S.; Johnson K.; Bolton B.; Teimouri Sangani M.; Rezai H.; Abdi S.; Pushpavathi M.; Hudock D.; Spears S.; Aliveto E. Success in changing stuttering attitudes: A retrospective study of 29 intervention samples. J Commun Disord 2020, 84, 105972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis,K.O.; Aliveto E.F.; Teimouri Sangan, M.; Abdi S.; Rezai H.; Abdalla F.; Przepiórka A.; Błachnio A.; Węsiersk; K., Junuzović-Žunić L.; Eisert S.; Roche C.K.; Reichel I.; Beste-Guldborg A.; Flynn T.; Bolton B.; Gottwald S.; Spears S.; Hudock D.; Hartley J.; Pushpavathi M.; Johnson K.N. Measuring public attitudes toward stuttering: Test-retest reliability revisited. Clinical Archives of Communication Disorders 2024, 9, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O.; Abdalla F.; Abdi S.; Aliveto E.; Beste-Guldborg A.; Błachnio A.; Bolton-Grant B.; Eisert S.; Flynn T.; Gottwald S.; Hartley J.; Hudock D.; Johnson K.N.; Junuzović-Žunić, L., Przepiórka, L., Pushpavathi, M., Reichel, I., Rezai, H., Roche, C., Spears S.; Teimouri Sangani M.; Węsierska K. Profiles of public attitude change regarding stuttering. Language and Health 2024, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.R.S.; St. Louis, K.O.; Leahy M.; Hall A.; Jesus L. A country-wide probability sample of public attitudes toward stuttering in Portugal. J Fluen Disord 2017, 52, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O.; Rogers A.L. Predicting stuttering attitudes from socioeconomic indicators: Education, occupation, and income. Poster at the Annual Convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, San Diego, CA, USA (November, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, R.M.; Warren, J.R. Socioeconomic indexes for occupations: A review, update, and critique. Sociological Methodol 1997, 27, 177–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O.; Lubker B.B.; Yaruss J.S.; Aliveto E.F. Development of a prototype questionnaire to survey public attitudes toward stuttering: Reliability of the second prototype. Contemp Issues Commun Sci Disord 2009, 36, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O.; Williams M.J.; Ware M.B.; Guendouzi J.; Reichel I.K. The public opinion survey of human attributes-stuttering (POSHA-S) and bipolar adjective scale (BAS): aspects of validity. Journal of Communication Disorders 2014, 50, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis K.O.; Reichel I.; Yaruss J.S.; Lubker B.B. Construct and concurrent validity of a prototype questionnaire to survey public attitudes toward stuttering. J Fluen Disord 2009, 34, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khaledi, M.; Lincoln, M.; McCabe, P.; Packman, A.; Alshatti, T. The attitudes, knowledge and beliefs of Arab parents in Kuwait about stuttering. J Fluen Disord 2009, 34, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, R.S.; St. Louis K.O.; Topbaş S. Public attitudes toward stuttering in Turkey: Probability versus convenience sampling. Journal of Fluency Disorders 2011, 36, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St. Louis K.O. POSHA–S public attitudes toward stuttering: Online versus paper surveys. Canad J Speech-Lang Pathol Audiol 2012, 36, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- St. Louis K.O. Public Opinion Survey of Human Attributes–Stuttering (POSHA–S) in English. Populore. Morgantown, WV, USA 2022. Available at https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/POSHAS-in-English-for-Stuttering-7759542.

- Weidner, M.E. ; St. Louis K.O. Public Opinion Survey of Human Attributes–Stuttering/Child (POSHA–S/Child) in English. Morgantown, WV, USA 2022. Available at https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/POSHASChild-in-English-for-Stuttering-7821535.

- St. Louis K.O. Public Opinion Survey of Human Attributes–Cluttering (POSHA–Cl) in English. Populore. Morgantown, WV, USA 2022. Available at https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/POSHACl-in-English-for-Cluttering-7784844.

- St. Louis, K.O. St. Louis, K.O. Appraisal of the Stuttering Environment (ASE) in English. Populore. Morgantown, WV, USA 2022. Available at https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/ASE-Appraisal-of-the-Stuttering-Environment-in-English-7759680.

- St. Louis, K.O. St. Louis, K.O. Excel Workbook Data Entry & Analysis Assistance. Populore. Morgantown, WV, USA 2022. Available at https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Excel-Workbook-Data-Entry-Analysis-Assistance-7846685.

- St. Louis, K.O. St. Louis, K.O. Formula Explanations for POSHA Instruments and the ASE. Populore. Morgantown, WV, USA 2022. Available at https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Formula-Explanations-for-POSHA-Instruments-the-ASE-7763337.

- St. Louis, K.O. St. Louis, K.O. IPATHA Bibliography. Populore. Morgantown, WV, USA 2022. Available at https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/IPATHA-Bibliography-9016470.

- St. Louis, K.O. St. Louis, K.O. IPATHA Instruments User’s Guide. Populore. Morgantown, WV, USA 2022. Available at https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/IPATHA-Instrument-Users-Guide-7935995.

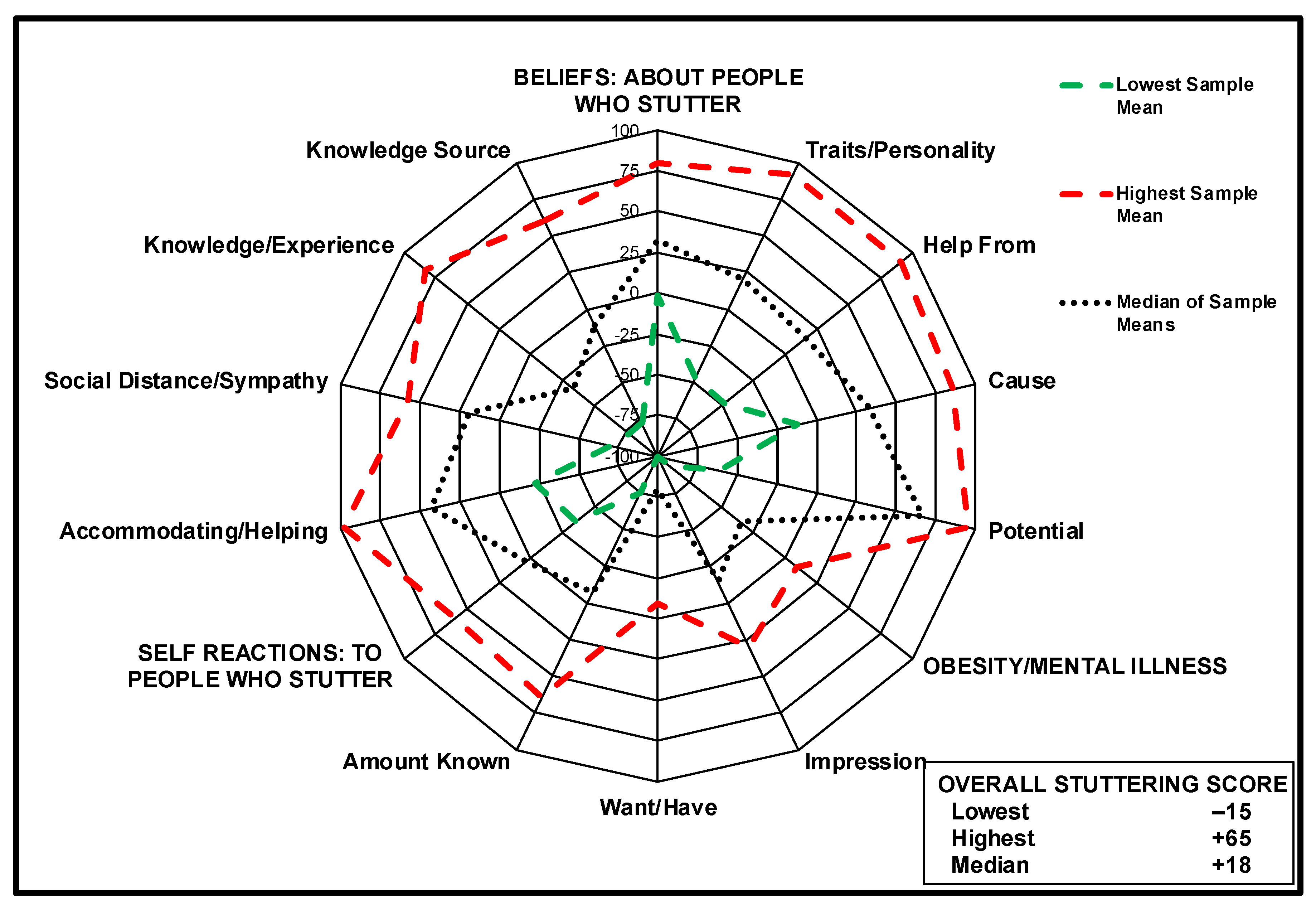

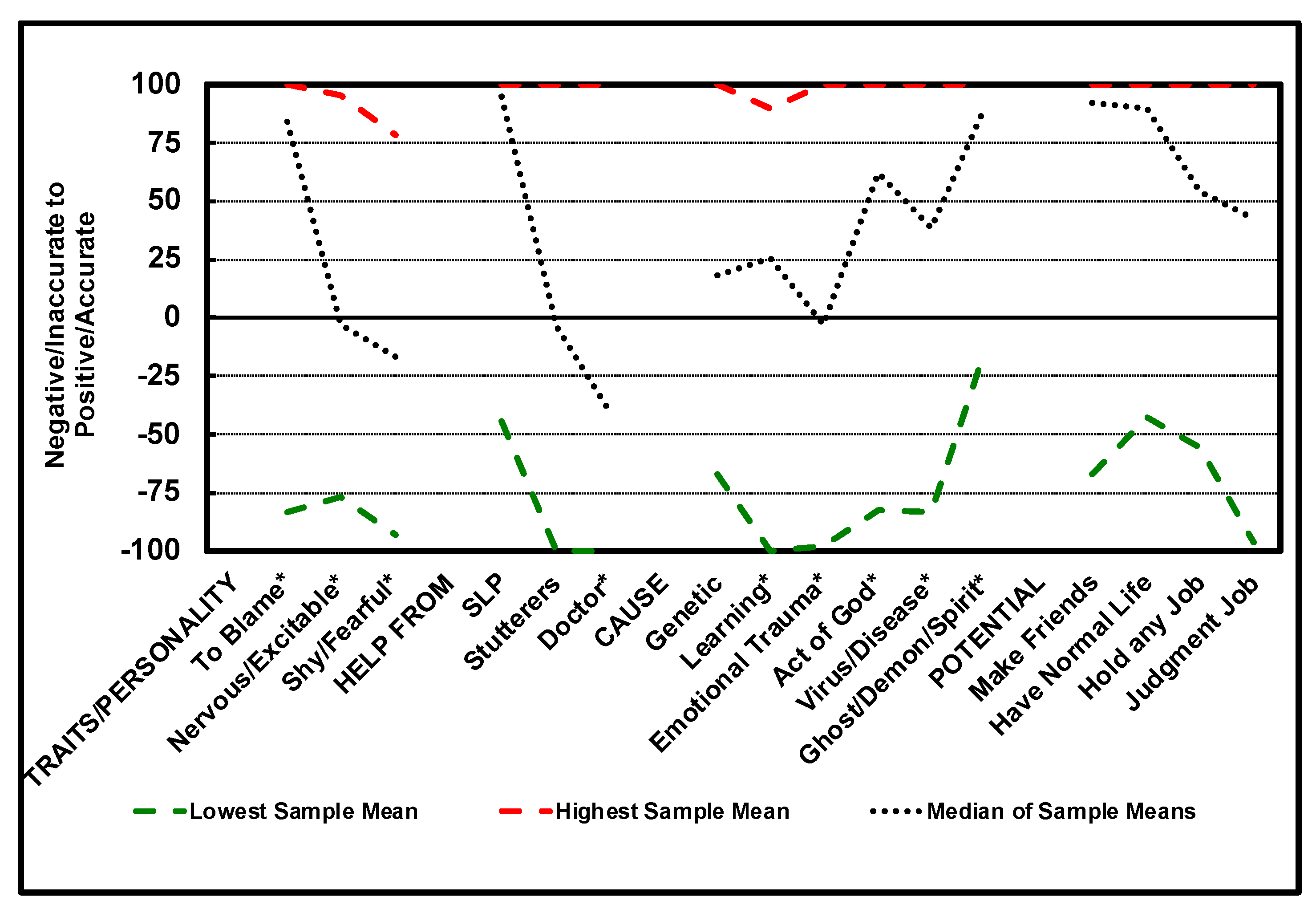

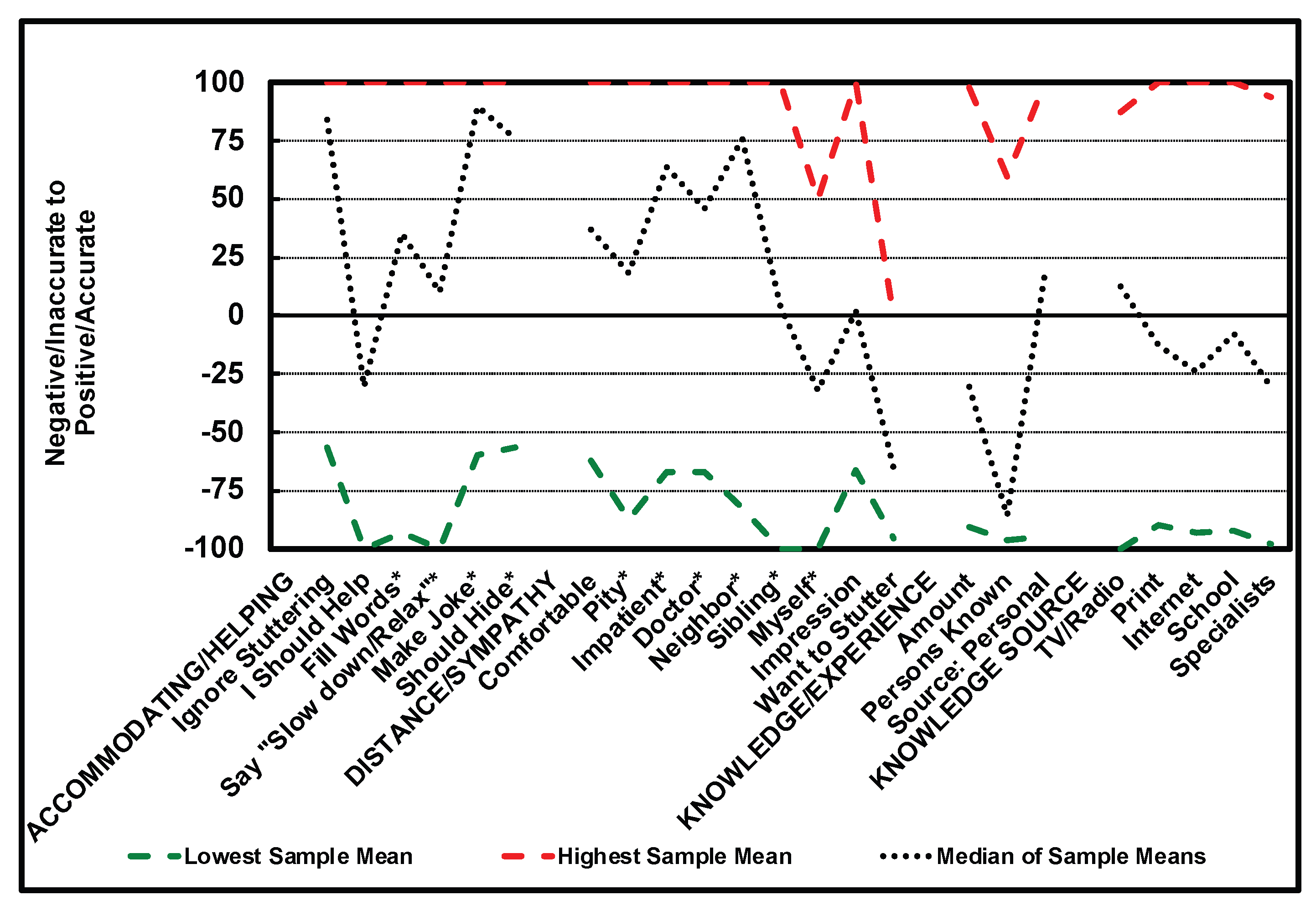

| POSHA–S Summary Scores | Lowest Sample Mean | Highest Sample Mean | Median of Sample Means | All Respondents: Mean | All Respondents: Standard Deviation |

| Overall Stuttering Score | -15 | +65 | +18 | +17 | 21 |

| Beliefs | -1 | +80 | +33 | +32 | 26 |

| Traits/Personality | -47 | +91 | +21 | +14 | 55 |

| Help From | -48 | +91 | +16 | +19 | 42 |

| Cause | -12 | +86 | +33 | +31 | 38 |

| Potential | -61 | +96 | +67 | +63 | 40 |

| Self Reactions | -36 | +60 | +3 | +3 | 26 |

| Accommodating/Helping | -22 | +98 | +44 | +41 | 36 |

| Social Distance/Sympathy | -71 | +57 | +19 | +9 | 42 |

| Knowledge/Experience | -77 | +83 | -34 | -33 | 44 |

| Knowledge Source | -76 | +60 | -11 | -5 | 60 |

| Obesity/Mental Illness | -90 | +2 | -35 | -31 | 29 |

| Impression | -100 | +26 | -15 | -10 | 44 |

| Want/Have | -100 | -10 | -79 | -77 | 37 |

| Amount Known | -75 | +53 | -9 | -5 | 46 |

|

Countrymen Rating |

Family /Friends Rating |

Relative Income Score |

|||||||||||

| 1 | x 5 = | 5 | + | 1 | = | 6 | -5 = | 1 | -13 = | -12 | x (100/12) = | -100.00 | |

| 1 | x 5 = | 5 | + | 2 | = | 7 | -5 = | 2 | -13 = | -11 | x (100/12) = | -91.67 | |

| Lowest | 1 | x 5 = | 5 | + | 3 | = | 8 | -5 = | 3 | -13 = | -10 | x (100/12) = | -83.33 |

| 5th | 1 | x 5 = | 5 | + | 4 | = | 9 | -5 = | 4 | -13 = | -9 | x (100/12) = | -75.00 |

| 1 | x 5 = | 5 | + | 5 | = | 10 | -5 = | 5 | -13 = | -8 | x (100/12) = | -66.67 | |

| 2 | x 5 = | 10 | + | 1 | = | 11 | -5 = | 6 | -13 = | -7 | x (100/12) = | -58.33 | |

| 2 | x 5 = | 10 | + | 2 | = | 12 | -5 = | 7 | -13 = | -6 | x (100/12) = | -50.00 | |

| 2 | x 5 = | 10 | + | 3 | = | 13 | -5 = | 8 | -13 = | -5 | x (100/12) = | -41.67 | |

| 2 | x 5 = | 10 | + | 4 | = | 14 | -5 = | 9 | -13 = | -4 | x (100/12) = | -33.33 | |

| 2 | x 5 = | 10 | + | 5 | = | 15 | -5 = | 10 | -13 = | -3 | x (100/12) = | -25.00 | |

| 3 | x 5 = | 15 | + | 1 | = | 16 | -5 = | 11 | -13 = | -2 | x (100/12) = | -16.67 | |

| 3 | x 5 = | 15 | + | 2 | = | 17 | -5 = | 12 | -13 = | -1 | x (100/12) = | -8.33 | |

| Middle | 3 | x 5 = | 15 | + | 3 | = | 18 | -5 = | 13 | -13 = | 0 | x (100/12) = | 0.00 |

| 5th | 3 | x 5 = | 15 | + | 4 | = | 19 | -5 = | 14 | -13 = | 1 | x (100/12) = | +8.33 |

| 3 | x 5 = | 15 | + | 5 | = | 20 | -5 = | 15 | -13 = | 2 | x (100/12) = | +16.67 | |

| 4 | x 5 = | 20 | + | 1 | = | 21 | -5 = | 16 | -13 = | 3 | x (100/12) = | +25.00 | |

| 4 | x 5 = | 20 | + | 2 | = | 22 | -5 = | 17 | -13 = | 4 | x (100/12) = | +33.33 | |

| 4 | x 5 = | 20 | + | 3 | = | 23 | -5 = | 18 | -13 = | 5 | x (100/12) = | +41.67 | |

| 4 | x 5 = | 20 | + | 4 | = | 24 | -5 = | 19 | -13 = | 6 | x (100/12) = | +50.00 | |

| 4 | x 5 = | 20 | + | 5 | = | 25 | -5 = | 20 | -13 = | 7 | x (100/12) = | +58.33 | |

| 5 | x 5 = | 25 | + | 1 | = | 26 | -5 = | 21 | -13 = | 8 | x (100/12) = | +66.67 | |

| 5 | x 5 = | 25 | + | 2 | = | 27 | -5 = | 22 | -13 = | 9 | x (100/12) = | +75.00 | |

| Highest | 5 | x 5 = | 25 | + | 3 | = | 28 | -5 = | 23 | -13 = | 10 | x (100/12) = | +83.33 |

| 5th | 5 | x 5 = | 25 | + | 4 | = | 29 | -5 = | 24 | -13 = | 11 | x (100/12) = | +91.67 |

| 5 | x 5 = | 25 | + | 5 | = | 30 | -5 = | 25 | -13 = | 12 | x (100/12) = | +100.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).