Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

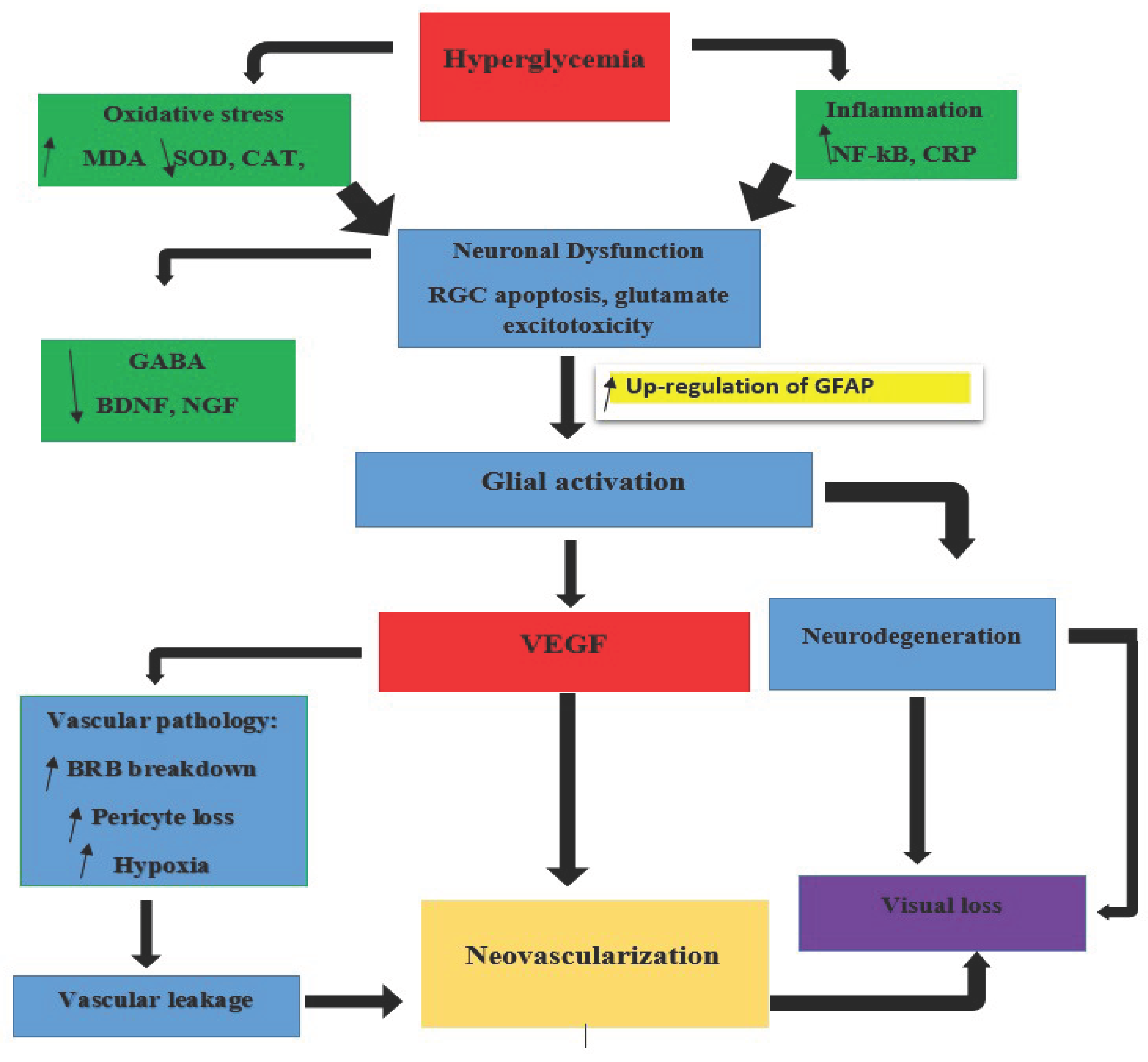

3. Pathophysiology of Diabetic Retinopathy

3.1. The Neurodegenerative Cascade

- i.

- Polyol Pathway

- ii.

- Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs)

- iii.

- Protein Kinase C (PKC) Activation

- iv.

- Hexosamine Pathway

4. Biomarkers of Retina Neurodegeneration

- i.

- Structural Biomarkers of Retinal Neurodegeneration

- ii.

- Functional Biomarkers of Neuronal Impairment

- iii.

- Biochemical and Molecular Biomarkers

- iv.

- Systemic Circulating Biomarkers

- v.

- Emerging Biomarkers of Retinal Neurodegeneration

- vi.

- AI-Driven Digital Biomarkers of Neurovascular Function

5. Summary

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGEs | Advanced Glycation End Products |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| BRB | Blood-Retinal Barrier |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| cSLO | Confocal Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy |

| CXCL13 | Chemokine (C-X-C Motif) Ligand 13 |

| Cx43 | Connexin-43 |

| DAG | Diacylglycerol |

| DCP | Deep Capillary Plexus |

| DME | Diabetic Macular Edema |

| DR | Diabetic Retinopathy |

| DRIL | Disorganization of Retinal Inner Layers |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| eNOS | Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| ERG | Electroretinogram |

| FAF | Fundus Autofluorescence |

| Fas/FasL | Fas Ligand |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| GFAT | Glutamine-Fructose-6-Phosphate Aminotransferase |

| GLAST | Glutamate Aspartate Transporter |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GCC | Ganglion Cell Complex |

| GC-IPL | Ganglion Cell-Inner Plexiform Layer |

| HBP | Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway |

| HIFs | Hypoxia-Inducible Factors |

| HRF | Hyperreflective Foci |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IP-10 | Interferon Gamma-Induced Protein 10 |

| IRBP | Interphotoreceptor Retinoid-Binding Protein |

| L1CAM | L1 Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

| MG-H1 | Methylglyoxal Hydroimidazolone |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| mfERG | Multifocal Electroretinogram |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate |

| NCAM | Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor-Kappa B |

| NfL | Neurofilament Light Chain |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NVU | Neurovascular Unit |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| OCTA | Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography |

| OGT | O-GlcNAc Transferase |

| PEDF | Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase |

| PKC | Protein Kinase C |

| RAGE | Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products |

| RPE | Retinal Pigment Epithelium |

| RNFL | Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| Sema3A | Semaphorin 3A |

| SiMoA | Single-Molecule Array |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| SST | Somatostatin |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| UDP-GlcNAc | Uridine Diphosphate N-Acetylglucosamine |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| ZEB2 | Zinc Finger E-Box Binding Homeobox 2 |

References

- Zhou, J.; Chen, B. Retinal Cell Damage in Diabetic Retinopathy. Cells. 2023, 12, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Tabasumma, N.; Snigdha, N.N.; Siam, N.H.; Panduru, R.V.N.R.S.; Azam, S.; Hannan, J.M.A.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A. Diabetic Retinopathy: An Overview on Mechanisms, Pathophysiology and Pharmacotherapy. Diabetology. 2022, 3, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.J.T.; Wong, M.Y.Z.; Cheong, K.X.; Zhao, J.; Teo, K.Y.C.; Tan, T.-E. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Retinal Vascular Disorders. Diagnostics. 2023, 13, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbort, C.P.; Papasavvas, I.; Tugal-Tutkun, I. Benefits and Limitations of OCT-A in the Diagnosis and Follow-Up of Posterior Intraocular Inflammation in Current Clinical Practice: A Valuable Tool or a Deceiver? Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, D.; Sagar, P.; Takkar, B. Diabetic retinal neurodegeneration as a form of diabetic retinopathy. International Ophthalmology. 2021, 41, 3223–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonetti, D.A.; Silva, P.S.; Stitt, A.W. Current understanding of the molecular and cellular pathology of diabetic retinopathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2021, 17, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.; Simó-Servat, O.; Porta, M.; Grauslund, J.; Harding, S.P.; Frydkjaer-Olsen, U.; García-Arumí, J.; Ribeiro, L.; Scanlon, P.; Cunha-Vaz, J.; Simó, R. Serum glial fibrillary acidic protein and neurofilament light chain as biomarkers of retinal neurodysfunction in early diabetic retinopathy: results of the EUROCONDOR study. Acta Diabetologica. 2023, 60, 837–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viggiano, P.; Vujosevic, S.; Palumbo, F.; Grassi, M.O.; Boscia, G.; Borrelli, E.; Reibaldi, M.; Sborgia, L.; Molfetta, T.; Evangelista, F.; Alessio, G. Optical coherence tomography biomarkers indicating visual enhancement in diabetic macular edema resolved through anti-VEGF therapy: OCT biomarkers in resolved DME. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy. 2024, 46, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit-McBride, Z.; Morse, L.S. MicroRNA and diabetic retinopathy—biomarkers and novel therapeutics. Annals of translational medicine. 2021, 9, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapislar, H.; Gurler, E.B. Management of microcomplications of diabetes mellitus: Challenges, current trends, and future perspectives in treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Lo, A.C.Y.; Mi, Y.; Ren, K.; Yang, D. Neurovascular unit in diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiological roles and potential therapeutical targets. Eye and Vision 2021, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, C.; Zheng, W.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yao, S.; Chen, X.; et al. Global, regional, and national epidemiology of visual impairment in working-age individuals, 1990-2019. JAMA ophthalmology 2024, 142, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Tan, B.; Yu, D.-Y.; Balaratnasingam, C. Differentiating microaneurysm pathophysiology in diabetic retinopathy through objective analysis of capillary nonperfusion, inflammation, and pericytes. Diabetes 2022, 71, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, K.; Kushwah, N.; Maurya, M.; Pavlovich, M.C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J. Assessment of inner blood–retinal barrier: Animal models and methods. Cells 2023, 12, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srejovic, J.V.; Muric, M.D.; Jakovljevic, V.L.; Srejovic, I.M.; Sreckovic, S.B.; Petrovic, N.T.; Todorovic, D.Z.; Bolevich, S.B.; Vulovic, T.S.S. Molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in the pathophysiology of retinal vascular disease—interplay between inflammation and oxidative stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 11850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshitari, T. The pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches of diabetic neuropathy in the retina. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 9050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobanovskaya, N. Pathophysiology of Diabetic Retinopathy. In Diabetic Eye Disease-From Therapeutic Pipeline to the Real World. IntechOpen, 2022.

- Kovács-Valasek, A.; Rák, T.; Pöstyéni, E.; Csutak, A.; Gábriel, R. Three major causes of metabolic retinal degenerations and three ways to avoid them. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair Stephen, H.; Kiran, E.M.; Talekar, S.; Schwartz, S.S. Diabetes mellitus associated neurovascular lesions in the retina and brain: A review. Frontiers in Ophthalmology 2022, 2, 1012804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Deng, C.; Paulus, Y.M. Advances in structural and functional retinal imaging and biomarkers for early detection of diabetic retinopathy. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanase, D.M.; Valasciuc, E.; Gosav, E.M.; Floria, M.; Buliga-Finis, O.N.; Ouatu, A.; Cucu, A.I.; Botoc, T.; Costea, C.F. Enhancing Retinal Resilience: The Neuroprotective Promise of BDNF in Diabetic Retinopathy. Life 2025, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshitari, T. Advanced glycation end-products and diabetic neuropathy of the retina. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, R.; Permana, H.; Kartasasmita, A.S.; Hilmanto, D.; Hidayat, R. Epigenetic Regulation of Sorbitol Dehydrogenase in Diabetic Retinopathy Patients: DNA Methylation, Histone Acetylation and microRNA-320. Biologics: Targets and Therapy.

- Dănilă, A.-I.; Ghenciu, L.A.; Stoicescu, E.R.; Bolintineanu, S.L.; Iacob, R.; Săndesc, M.-A.; Faur, A.C. Aldose reductase as a key target in the prevention and treatment of diabetic retinopathy: a comprehensive review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Tang, P.; Lv, H. Targeting oxidative stress in diabetic retinopathy: mechanisms, pathology, and novel treatment approaches. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, 16, 1571576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, M.F.A.; Khan, S.; Alouffi, S.; Khan, M.; Khan, M.W.A.; Ansari, I.A. Inhibition of the polyol pathway by Ducrosia anethifolia extract: plausible implications for diabetic retinopathy treatment. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 15, 1513967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Q.; Dai, H.; Jiang, S.; Yu, L. Advanced glycation end products in diabetic retinopathy and phytochemical therapy. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 1037186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, J.S.; Ramanujam, R.K.; Risman, R.A.; Tutwiler, V.; Berthiaume, F.; Vazquez, M. Neurovascular Relationships in AGEs-Based Models of Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy” Bioengineering 2024, 11, 63. 11. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Fan, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. RAGE plays key role in diabetic retinopathy: a review. BioMedical Engineering OnLine 2023, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Meng, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Hu, P.; Luo, E. Advanced glycation end products and reactive oxygen species: uncovering the potential role of ferroptosis in diabetic complications. Molecular Medicine 2024, 30, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Fukami, K. RAGE signaling regulates the progression of diabetic complications. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 14, 1128872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, A.; Lindner, C.; Schneider, I.; Gonzalez, I.; Uribarri, J. The RAGE Axis: A Relevant Inflammatory Hub in Human Diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, N.M.; Paraoan, L.; Khaliddin, N.; Kamalden, T.A. Thymoquinone in ocular neurodegeneration: modulation of pathological mechanisms via multiple pathways. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2022, 16, 786926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Xu, L.; Guo, M. The role of protein kinase C in diabetic microvascular complications. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13, 973058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Osorio, M.L.; Sabath, E. Tight junction disruption and the pathogenesis of the chronic complications of diabetes mellitus: A narrative review. World Journal of Diabetes 2023, 14, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Z. Mechanistic pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction in diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy. Frontiers in endocrinology 2022, 13, 816400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, B.; Wu, F.; Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Ma, N.; et al. Protein O-GlcNAcylation coupled to Hippo signaling drives vascular dysfunction in diabetic retinopathy. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 9334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Eshwaran, R.; Beck, S.C.; Hammes, H.P.; Wieland, T.; Feng, Y. Contribution of the Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway in the Hyperglycemia-Dependent and -Independent Breakdown of the Retinal Neurovascular Unit. Molecular Metabolism 2023, 73, 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dong, W.; Li, J.; Kong, Y.; Ren, X. O-GlcNAc modification and its role in diabetic retinopathy. Metabolites 2022, 12, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starace, V.; Battista, M.; Brambati, M.; Cavalleri, M.; Bertuzzi, F.; Amato, A.; Lattanzio, R.; Bandello, F.; Cicinelli, M.V. The role of inflammation and neurodegeneration in diabetic macular edema. Therapeutic Advances in Ophthalmology 2021, 13, 25158414211055963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Park, S.-J.; Song, M. Diabetic Retinopathy (DR): Mechanisms, Current Therapies, and Emerging Strategies. Cells 2025, 14, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Casanova, J.; Schmachtenberg, O.; Martínez, A.D.; Sanchez, H.A.; Harcha, P.A.; Rojas-Gomez, D. An Update on Connexin Gap Junction and Hemichannels in Diabetic Retinopathy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Ashique, S.; Afzal, O.; Altamimi, M.A.; Malik, A.; Kumar, S.; Garg, A.; Sharma, N.; Farid, A.; Khan, T.; et al. A correlation between oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: an updated review. Experimental eye research 2023, 236, 109650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Tao, L.; Jiang, Z. Alleviate oxidative stress in diabetic retinopathy: antioxidant therapeutic strategies. Redox Report 2023, 28, 2272386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragiotta, S.; Pinazo-Durán, M.D.; Scuderi, G. Understanding neurodegeneration from a clinical and therapeutic perspective in early diabetic retinopathy. Nutrients 2022, 14, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, A.; Jha, S.; Valdez, L.; Tsin, A. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of neuronal degeneration in early-stage diabetic retinopathy. Current Vascular Pharmacology 2024, 22, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzamino, B.O.; Cacciamani, A.; Dinice, L.; Cecere, M.; Pesci, F.R.; Ripandelli, G.; Micera, A. Retinal Inflammation and Reactive Müller Cells: Neurotrophins’ Release and Neuroprotective Strategies. Biology 2024, 13, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, D.; Son, T.; Lim, J.I.; Yao, X. Quantitative optical coherence tomography reveals rod photoreceptor degeneration in early diabetic retinopathy. Retina 2022, 42, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haydinger, C.D.; Oliver, G.F.; Ashander, L.M.; Smith, J.R. Oxidative Stress and Its Regulation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Pritchard, N.; Sampson, G.P.; Edwards, K.; Vagenas, D.; Russell, A.W.; Malik, R.A.; Efron, N. Diagnostic capability of retinal thickness measures in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Journal of optometry 2017, 10, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chondrozoumakis, G.; Chatzimichail, E.; Habra, O.; Vounotrypidis, E.; Papanas, N.; Gatzioufas, Z.; Panos, G.D. Retinal Biomarkers in Diabetic Retinopathy: From Early Detection to Personalized Treatment” Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14, 1343. 14. [CrossRef]

- Simó, R.; Stitt, A.W.; Gardner, T.W. Neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy: does it really matter? Diabetologia 2018, 61, 1902–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.J.; Joglekar, M.V.; Hardikar, A.A.; Keech, A.C.; O’Neal, D.N.; Januszewski, A.S. Biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy. The review of diabetic studies: RDS 2015, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Chan, M.Y.; Leung, W.Y.; Wong, H.Y.; Ng, C.M.; Chan, V.T.; Wong, R.; Lok, J.; Szeto, S.; Chan, J.C.K.; et al. Assessment of retinal neurodegeneration with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eye 2021, 35, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.; Desbiens, J.; Gross, R.; Gupta, S.; Dodhia, R.; Ferres, J.L. Retinal Microvasculature as Biomarker for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases. arXiv arXiv:2107.13157, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, L.; Arrigo, A.; Aragona, E.; Antropoli, A.; Berni, A.; Saladino, A.; Parodi, M.B.; Bandello, F. Neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 14, 937999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragiotta, S.; Abdolrahimzadeh, S.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Sakurada, Y.; Gal-Or, O.; Scuderi, G.; Milani, P. Significance of hyperreflective foci as an optical coherence tomography biomarker in retinal diseases: characterization and clinical implications. Journal of ophthalmology 2021, 2021, 6096017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.F.; Pihl-Jensen, G.; Torm, M.E.W.; Passali, M.; Larsen, M.; Frederiksen, J.L. Hyperreflective dots in the avascular outer retina in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2023, 72, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midena, E.; Torresin, T.; Velotta, E.; Pilotto, E.; Parrozzani, R.; Frizziero, L. OCT hyperreflective retinal foci in diabetic retinopathy: a semi-automatic detection comparative study. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 613051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artemiev, D.; Valmaggia, C.; Tschuppert, S.; Kotliar, K.; Türksever, C.; Todorova, M.G. Retinal vessel flicker light responsiveness and its relation to analysis protocols and static and metabolic data in healthy subjects. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, M.E.J.; Slocomb, J.E.; Shivkumar, V.; Smith, B.; Gabbay, R.A.; Quillen, D.; Gardner, T.W.; Bettermann, K. Comparison of retinal vasodilator and constrictor responses in type 2 diabetes. Acta ophthalmologica 2012, 90, e434–e441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadzie, A.K.; Le, D.; Abtahi, M.; Ebrahimi, B.; Son, T.; Lim, J.I.; Yao, X. Normalized blood flow index in optical coherence tomography angiography provides a sensitive biomarker of early diabetic retinopathy. Translational Vision Science & Technology 2023, 12, 3–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva Mira, M. Retinal neurodegeneration in diabetes: an emerging concept in diabetic retinopathy. Current diabetes reports 2021, 21, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, A.J.; Joglekar, M.V.; Hardikar, A.A.; Keech, A.C.; O’Neal, D.N.; Januszewski, A.S. Biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy. The review of diabetic studies: RDS 2015, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dartt Darlene, A. Encyclopedia of the Eye. Vol. 1. Academic Press, 2010.

- Channa, R.; Wolf, R.M.; Simo, R.; Brigell, M.; Fort, P.; Curcio, C.; Lynch, S.; Verbraak, F.; Abramoff, M.D.; Brigell, M.; et al. A new approach to staging diabetic eye disease: staging of diabetic retinal neurodegeneration and diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology Science 2024, 4, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Alvarez, M.; Tomas-Grasa, C.; Sopeña-Pinilla, M.; Orduna-Hospital, E.; Fernandez-Espinosa, G.; Bielsa-Alonso, S.; Acha-Perez, J.; Rodriguez-Mena, D.; Pinilla, I. Electrophysiological findings in long-term type 1 diabetes patients without diabetic retinopathy using different ERG recording systems. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, P.A.; Lim, J.K.; Thompson, D.A. Thompson. Retinal electrophysiology in central nervous system disorders. A review of human and mouse studies. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2023, 17, 1215097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Kirandeep, and Bharat Gurnani. Contrast sensitivity. (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580542/.

- Alghwiri Alia, A. Balance and falls. In Geriatric physical therapy, p. 331. Elsevier, 2011.

- Andrade Luciana Cristina, O.; Souza, G.S.; Lacerda, E.M.C.B.; Nazima, M.T.S.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Otero, L.M.; Pena, F.P.S.; Silveira, L.C.L.; Côrtes, M.I.T. Influence of retinopathy on the achromatic and chromatic vision of patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC ophthalmology 2014, 14, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Safi, S.; Rahimi, A.; Raeesi, A.; Safi, H.; Amiri, M.A.; Malek, M.; Yaseri, M.; Haeri, M.; Middleton, F.A.; Solessio, E.; et al. Contrast sensitivity to spatial gratings in moderate and dim light conditions in patients with diabetes in the absence of diabetic retinopathy. BMJ open diabetes research & care 2017, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. , Deng, C. and Paulus, Y.M. Advances in Structural and Functional Retinal Imaging and Biomarkers for Early Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitake, S.; Murakami, T.; Uji, A.; Unoki, N.; Dodo, Y.; Horii, T.; Yoshimura, N. Clinical relevance of quantified fundus autofluorescence in diabetic macular oedema. Eye 2015, 29, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, O.-M.; Zemba, M.; Brănișteanu, D.C.; Pîrvulescu, R.A.; Radu, M.; Stanca, H.T. Fundus Autofluorescence in Diabetic Retinopathy. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2024, 14, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, K.B.; Mrejen, S.; Jung, J.; Yannuzzi, L.A.; Boon, C.J.F. Increased fundus autofluorescence related to outer retinal disruption. JAMA ophthalmology 2013, 131, 1645–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Toh, H.; Jiang, P. Fluorescein Angiography Image-AI Based Early Diabetic Retinopathy Detection. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohankumar, Arthi, and Bharat Gurnani. Scanning laser ophthalmoscope. (2022).

- LaRocca, F.; Dhalla, A.-H.; Kelly, M.P.; Farsiu, S.; Izatt, J.A. Optimization of confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope design. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2013, 18, 076015–076015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.G.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, C.; Cicinelli, M.V. Early Microglial Changes Associated with Diabetic Retinopathy in Rats with Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Research 2021, 2021, 4920937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Garcia, S.; Reichhart, N.; Hernandez-Matas, C.; Zabulis, X.; Kociok, N.; Brockmann, C.; Joussen, A.M.; Strauß, O. In vivo analysis of the time and spatial activation pattern of microglia in the retina following laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Experimental eye research 2015, 139, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Zhang, T.; Madigan, M.C.; Fernando, N.; Aggio-Bruce, R.; Zhou, F. Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP) in retinal health and disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 577935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.J.; Joglekar, M.V.; Hardikar, A.A.; Keech, A.C.; O’Neal, D.N.; Januszewski, A.S. Biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy. The review of diabetic studies: RDS 2015, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Meng, Y.; Tan, M.; Ma, J.; Zhu, J.; Ji, M.; Guan, H. Changes in expression of inflammatory cytokines and ocular indicators in pre-diabetic patients with cataract. BMC ophthalmology 2025, 25, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zeng, L.; Liu, J.; Ou, K. On implications of somatostatin in diabetic retinopathy. Neural Regeneration Research 2024, 19, 1984–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soedarman, S.; Julia, M.; Gondhowiardjo, T.D.; Kurnia, K.H.; Prasetya, A.D.B.; Triyoga, I.F.; Sasongko, M.B. Serum Apolipoprotein B and B/A1 Ratio as Early Negative Biomarkers for OCT-and OCTA-Detected Retinal Changes in Diabetic Macular Edema. Clinical Ophthalmology 2025, 2165–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtar, E.R.; Mahmoud, D.A.; Ebrahim, G.E.; Al Anany, M.G.; Seliem, N.; Hassan, M.M. Serum metabolomic profiles and semaphorin-3A as biomarkers of diabetic retinopathy progression. Egypt. J. Immunol 2023, 30, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, G. , Siddiquei, M.M. and Abu El-Asrar, A.M. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase mediates diabetes-induced retinal neuropathy. Mediators of inflammation 2013, 2013, 510451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu El-Asrar, A.M.; Dralands, L.; Missotten, L.; Al-Jadaan, I.A.; Geboes, K. Expression of apoptosis markers in the retinas of human subjects with diabetes. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2004, 45, 2760–2766. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde, Angela M., Soledad Miranda, Marta García-Ramírez, Águeda González-Rodriguez, Cristina Hernández, and Rafael Simó. Proapoptotic and survival signaling in th Miyagishima, Kiyoharu Joshua, Francisco Manuel Nadal-Nicolás, Wenxin Ma, and Wei Li. Annexin-V binds subpopulation of immune cells altering its interpretation as an in vivo biomarker for apoptosis in the retina. International Journal of Biological Sciences 20, no. 15 (2024): 6073.e neuroretina at early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Molecular Vision 19 (2013): 47.

- Hajari, J.N.; Ilginis, T.; Pedersen, T.T.; Lønkvist, C.S.; Saunte, J.P.; Hofsli, M.; Schmidt, D.C.; Al-Abaiji, H.A.; Ahmed, Y.; Bach-Holm, D.; et al. Novel Blood-Biomarkers to Detect Retinal Neurodegeneration and Inflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klochkov, V.; Chan, C.-M.; Lin, W.-W. Methylglyoxal: A Key Factor for Diabetic Retinopathy and Its Effects on Retinal Damage. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentata, R.; Cougnard-Grégoire, A.; Delyfer, M.N.; Delcourt, C.; Blanco, L.; Pupier, E.; Rougier, M.B.; Rajaobelina, K.; Hugo, M.; Korobelnik, J.F.; et al. Skin autofluorescence, renal insufficiency and retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications 2017, 31, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Ma, X.; Shin, Y.H.; Chen, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, K.; Wu, W.; Liang, W.; Wu, Y.; Song, Q.; et al. Pathogenic role of human C-reactive protein in diabetic retinopathy. Clinical Science 2020, 134, 1613–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.; Martins, B.; Caramelo, F.; Gonçalves, C.; Trindade, G.; Simão, J.; Barreto, P.; Marques, I.; Leal, E.C.; Carvalho, E.; et al. Putative biomarkers in tears for diabetic retinopathy diagnosis. Frontiers in medicine 2022, 9, 873483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Tan, X.; McDonald, J.; Kaminga, A.C.; Chen, Y.; Dai, F.; Qiu, J.; Zhao, K.; Peng, Y. Chemokines in diabetic eye disease. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome 2024, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thota, R.N.; Chatterjee, P.; Pedrini, S.; Hone, E.; Ferguson, J.J.; Garg, M.L.; Martins, R.N. Association of plasma neurofilament light chain with glycaemic control and insulin resistance in middle-aged adults. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13, 915449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzamino, B.O.; Cacciamani, A.; Dinice, L.; Cecere, M.; Pesci, F.R.; Ripandelli, G.; Micera, A. Retinal Inflammation and Reactive Müller Cells: Neurotrophins’ Release and Neuroprotective Strategies. Biology 2024, 13, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Ling, F.; Zhang, G.W.; Yu, N.; Yang, J.; Xin, X.Y. The correlation between MicroRNAs and diabetic retinopathy. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 941982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Wan, J.; Tan, G. The mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome/pyroptosis activation and their role in diabetic retinopathy. Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 1151185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Q.; Su, G. Roles of miRNAs and long noncoding RNAs in the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Bioscience Reports 2017, 37, BSR20171157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Cai, Y.; Pan, J.; Chen, Q. Role of MicroRNA in linking diabetic retinal neurodegeneration and vascular degeneration. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2024, 15, 1412138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Zheng, X.; Yang, M.M. New insights of potential biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy: integrated multi-omic analyses. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2025, 16, 1595207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.; Mansour, A.M.; Baban, B.; Elmasry, K. Extracellular Vesicles and Diabetic Retinopathy: Nano-Sized Vesicles with Mega-Sized Hopes. In Diabetic Retinopathy-Advancement in Understanding the Pathophysiology and Management Strategies. IntechOpen, 2024.

- Peng, X.; Peng, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Zhou, G.; Cai, Y. Breakthroughs in diabetic retinopathy diagnosis and treatment using preclinical research models: current progress and future directions. Annals of Medicine 2025, 57, 2531251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, J.; Fadavi, H.; Tavakoli, M. Neurodegeneration of the cornea and retina in patients with type 1 diabetes without clinical evidence of diabetic retinopathy. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13, 790255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerani, A.; Tetreault, N.; Menard, C.; Lapalme, E.; Patel, C.; Sitaras, N.; Beaudoin, F.; et al. Neuron-derived semaphorin 3A is an early inducer of vascular permeability in diabetic retinopathy via neuropilin-1. Cell metabolism 2013, 18, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Huang, R.; Nao, J.; Dong, X. The Role of Semaphorin 3 A in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Aging-Related Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmacological Research 2025, 107732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bista Karki, S.; Coppell, K.J.; Mitchell, L.V.; Ogbuehi, K.C. Dynamic pupillometry in type 2 diabetes: pupillary autonomic dysfunction and the severity of diabetic retinopathy. Clinical ophthalmology 2020, 3923–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudzik, A.; Śledzianowski, A.; Przybyszewski, A.W. Przybyszewski. Machine learning and digital biomarkers can detect early stages of neurodegenerative diseases. Sensors 2024, 24, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M. , Devan, S.; Jaisankar, D.; Swaminathan, G.; Pardhan, S.; Raman, R. Pupillary abnormalities with varying severity of diabetic retinopathy. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, A.; Mahmood, Z.; Qureshi, R.; Ali, H. Enhancing diabetic retinopathy classification accuracy through dual-attention mechanism in deep learning. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering: Imaging & Visualization 2025, 13, 2539079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Lim, J.; Lim, G.Y.S.; Ong, J.C.L.; Ke, Y.; Tan, T.F.; Tan, T.E.; Vujosevic, S.; Ting, D.S.W. Novel artificial intelligence algorithms for diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema. Eye and Vision 2024, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagin, F.H.; Colak, C.; Algarni, A.; Gormez, Y.; Guldogan, E.; Ardigò, L.P. Hybrid Explainable Artificial Intelligence Models for Targeted Metabolomics Analysis of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, J.; Jin, E.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Han, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Serum untargeted metabolomics reveal potential biomarkers of progression of diabetic retinopathy in asians. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2022, 9, 871291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).