1. Introduction

Plastic pollution has emerged as one of the most pressing global environmental challenges of the 21st century, with microplastics (MPs)—plastic fragments smaller than or equal to 5 mm—being recognized as a particularly harmful and pervasive class of contaminants [

1,

2,

3]. MPs originate from primary sources, mainly industrial activities, and secondary sources, in which larger plastic debris is degraded [

4]. Once introduced into the environment, MPs are persistent and easily transported by wind, rivers, and ocean currents, infiltrating terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems across the globe [

5,

6]. Alarmingly, MPs have been detected in remote regions far from human activity, such as the Arctic [

7], deep ocean sediments [

8], and even the atmosphere [

9]. The World Economic Forum has projected that, without drastic interventions, plastic pollution will continue to increase exponentially, with the mass of plastics in the ocean expected to surpass that of fish by 2050 [

10]. The ecological and human health risks posed by MPs are also substantial [

11,

12,

13]. As global awareness of MP pollution grows, so does the urgency to develop robust tools for monitoring, characterizing, and mitigating their presence in natural environments.

A critical parameter in understanding the environmental fate and transport of MPs is their settling velocity, which determines whether a particle remains suspended or settles onto sediments [

14,

15]. Settling velocity directly influences deposition patterns in rivers, lakes, oceans, and coastal systems, as well as the residence time of MPs in the water column [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Factors such as particle density, shape, size, and surface roughness, as well as water properties like salinity, temperature, and turbulence, all affect the settling dynamics and distribution of MPs [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. For example, denser particles, such as those made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), sink more rapidly compared to low-density polymers like polyethylene (PE), which may remain buoyant or suspended for extended periods [

26]. Furthermore, the interaction of a MP with biofilms and sediment can alter the profile of a particle, thereby influencing its settling behavior [

27,

28].

Unlike natural sediments, MPs often exhibit complex shapes—such as fibers, films, foams, and fragments—that defy the assumptions of classical sediment transport models [

29]. Traditional empirical formulas, developed for spherical or near-spherical mineral grains, often yield inaccurate predictions when applied to MPs [

26,

30]. This discrepancy underscores the need for direct measurement techniques that can capture the unique and variable behavior of plastic particles.

Most laboratory measurements of MP settling velocity rely on simple methods such as timing the descent of particles through a column of water using a stopwatch [

21,

22,

23,

31]. While straightforward, this manual approach is highly subjective, prone to human error, and unsuitable for high-throughput measurements or real-time monitoring. Additionally, this technique is unable to capture subtle particle dynamics, such as oscillation or changes in orientation during sinking. Some researchers have employed high-speed cameras to capture the trajectories of submillimeter MPs in greater detail [

32,

33]. However, these systems are expensive, require specialized expertise, and typically involve post-processing of large datasets, which is time-consuming and impractical for routine measurements.

Another challenge with existing methods is the lack of standardization in experimental setups and analysis techniques. Differences in water column dimensions, lighting conditions, and background contrast can introduce inconsistencies, making it difficult to compare results across studies. Moreover, few studies have explored real-time analysis of MP settling dynamics, which could enable the rapid generation of datasets for modeling and decision-making.

In recent years, computer vision and artificial intelligence (AI) have emerged as transformative technologies for environmental monitoring. By leveraging advances in deep learning and high-resolution imaging, AI-vision systems can automatically detect, classify, and track objects in real time, with performance often surpassing that of human observers [

34,

35]. In aquatic environments, AI-based computer vision has been successfully applied for tasks such as identifying marine debris [

36], monitoring plankton populations [

37], and tracking fish behavior [

38]. These advances suggest that AI vision can also be a powerful tool for characterizing MPs and their dynamics.

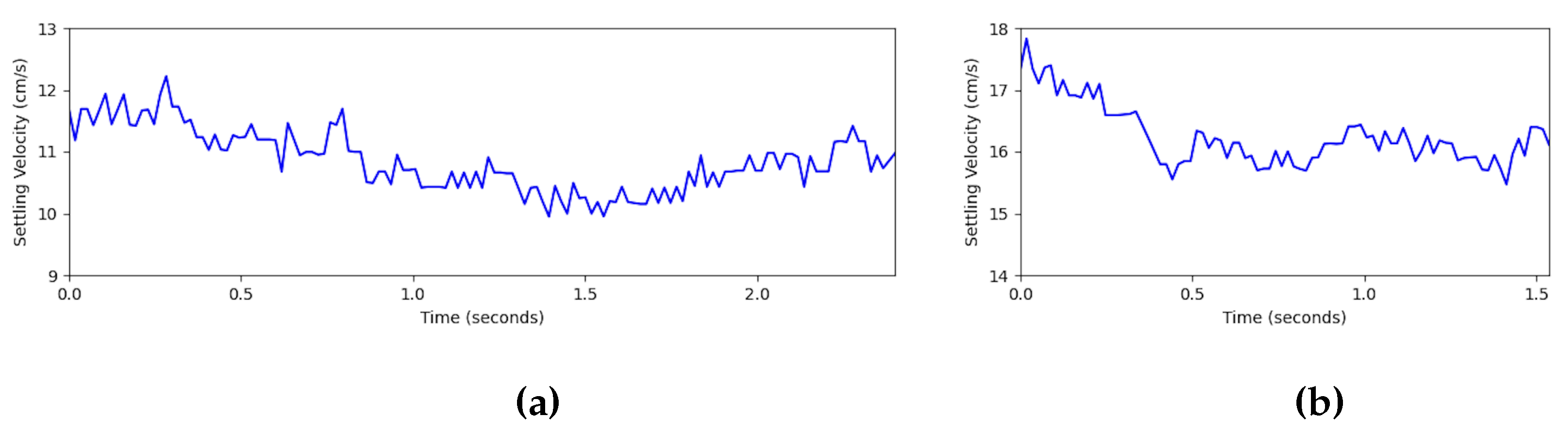

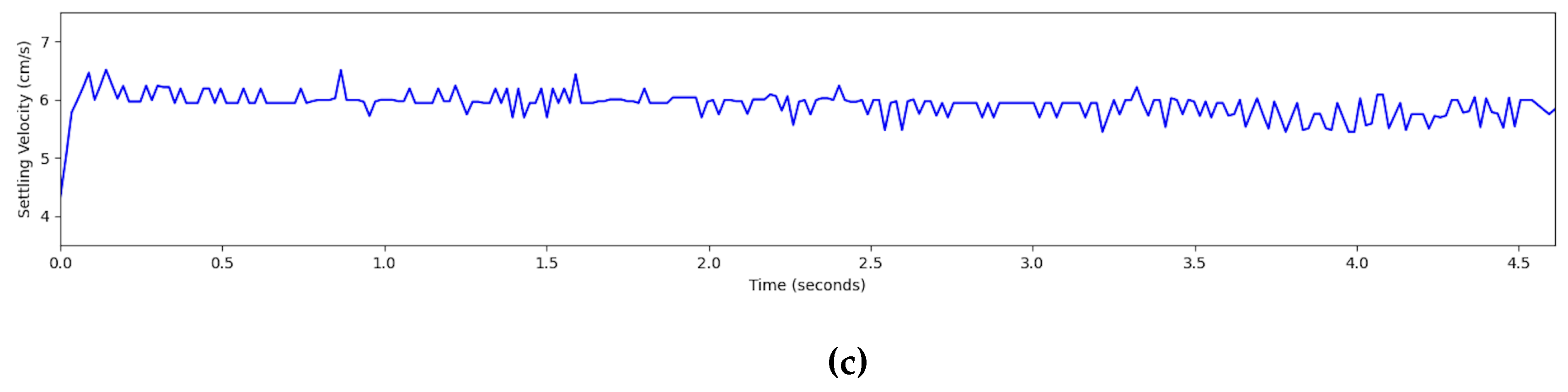

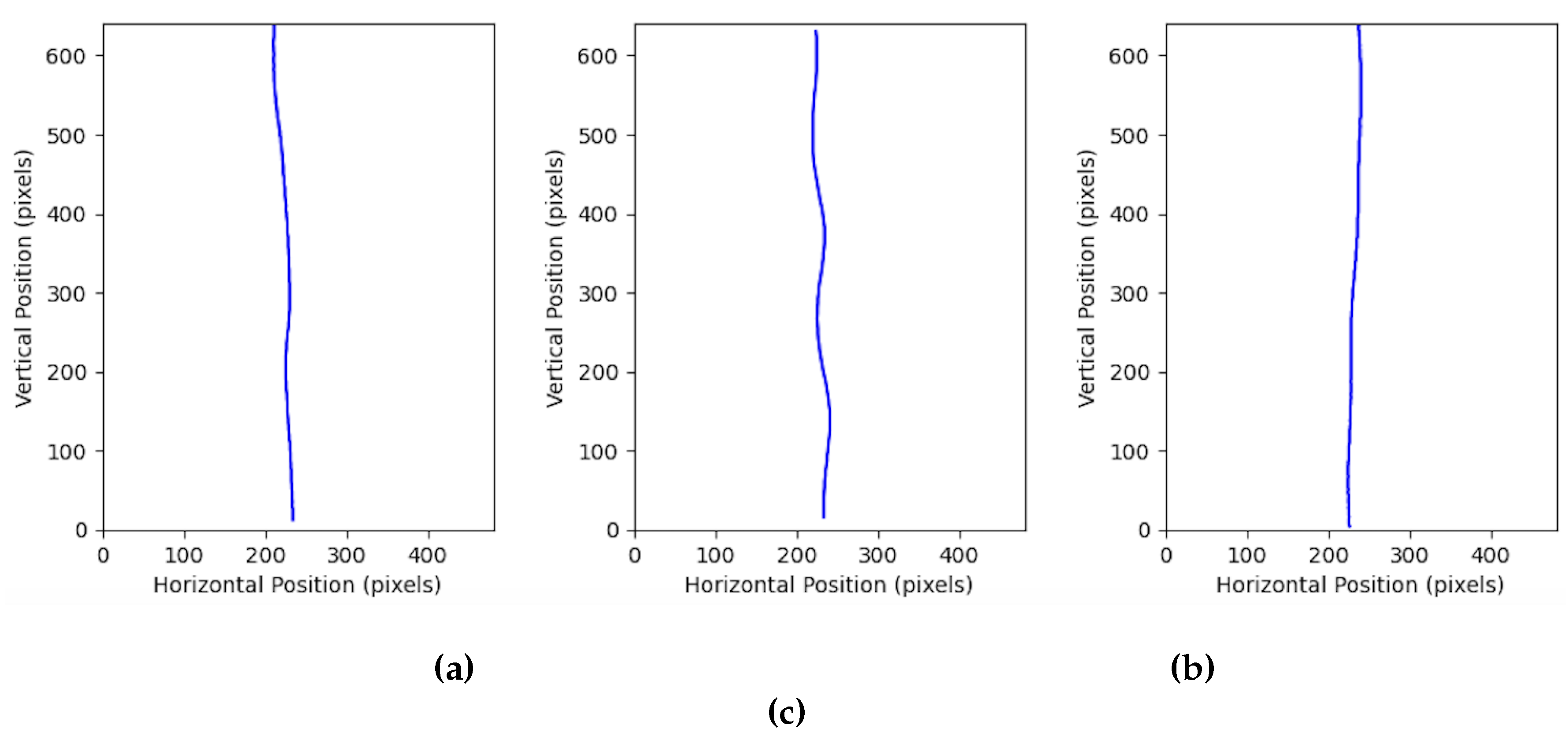

Our previous work demonstrated the feasibility of combining deep learning-based computer vision with relatively simple optical setups to achieve accurate in situ measurements of MPs. Building on this foundation, the present study explores the application of a similar method for detecting and quantifying MP settling velocity—a parameter that has not been systematically measured using AI-vision techniques. By automatically tracking MPs as they settle through a water column, a computer vision system can generate accurate velocity estimates, size measurements, and trajectory data in real time. This eliminates the subjectivity associated with human observation, allows for the processing of large datasets, and enables reproducibility and standardization.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

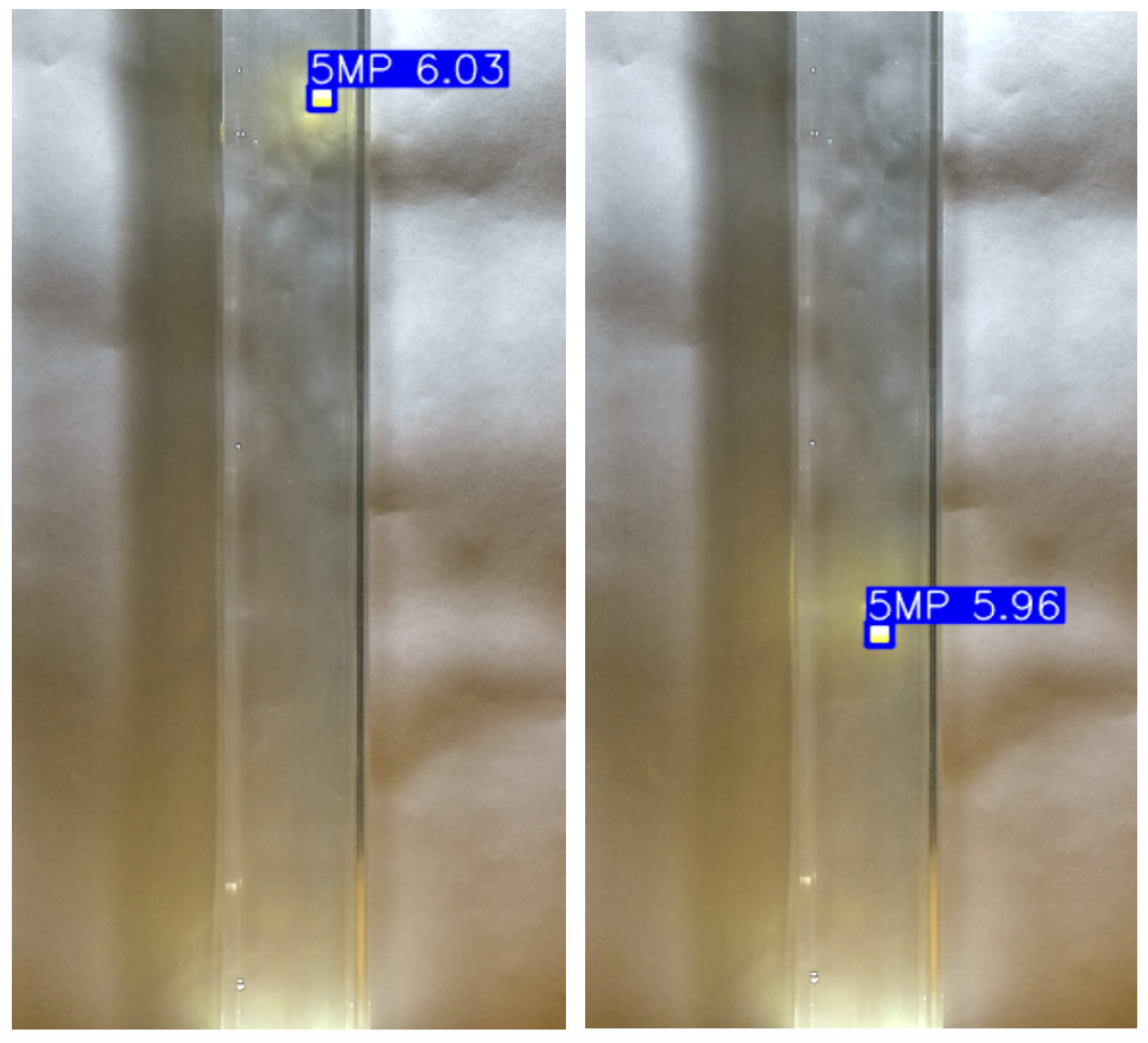

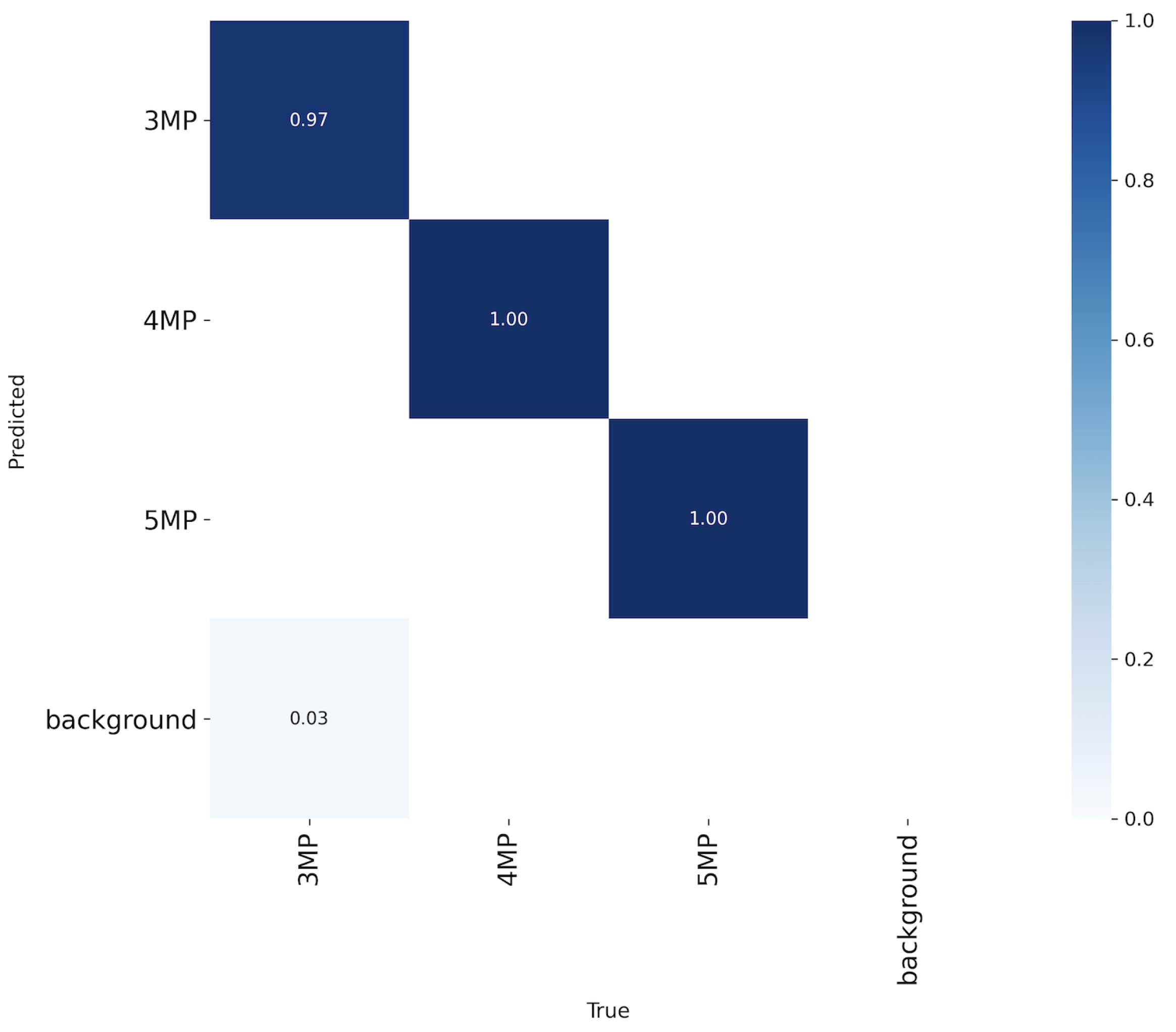

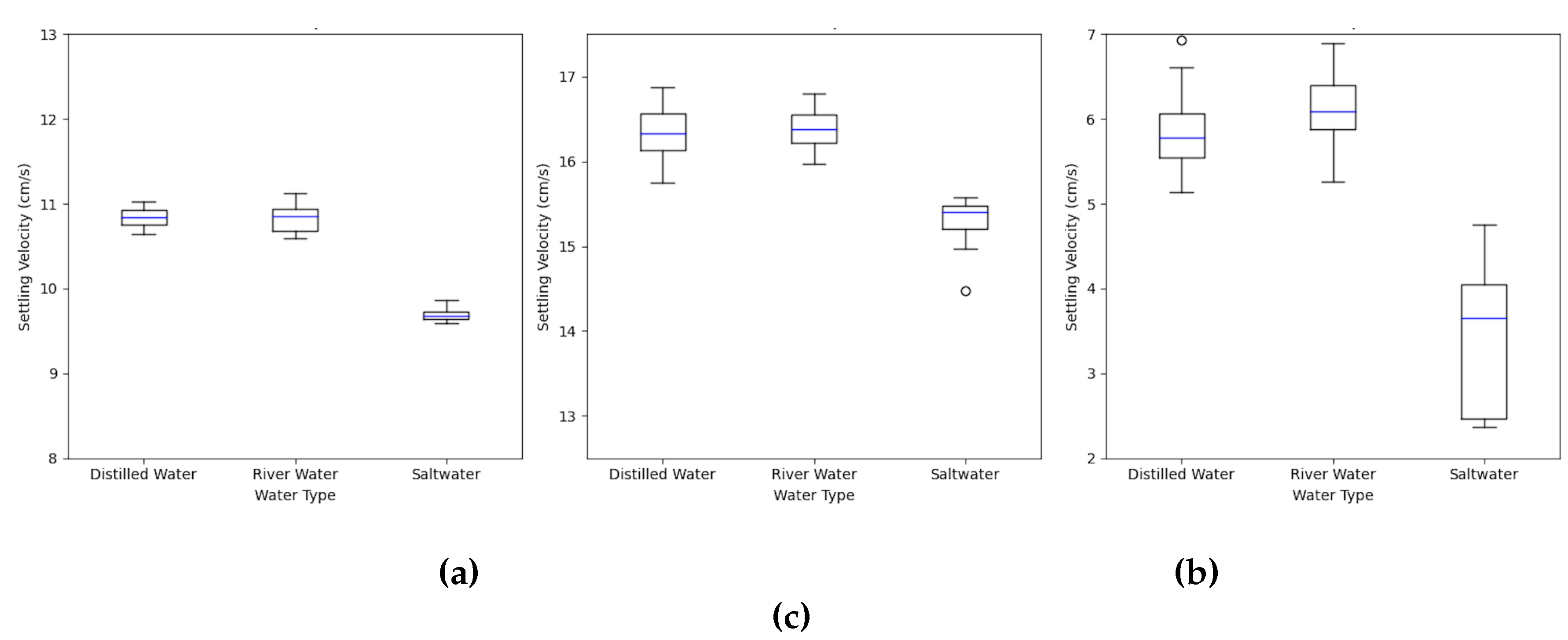

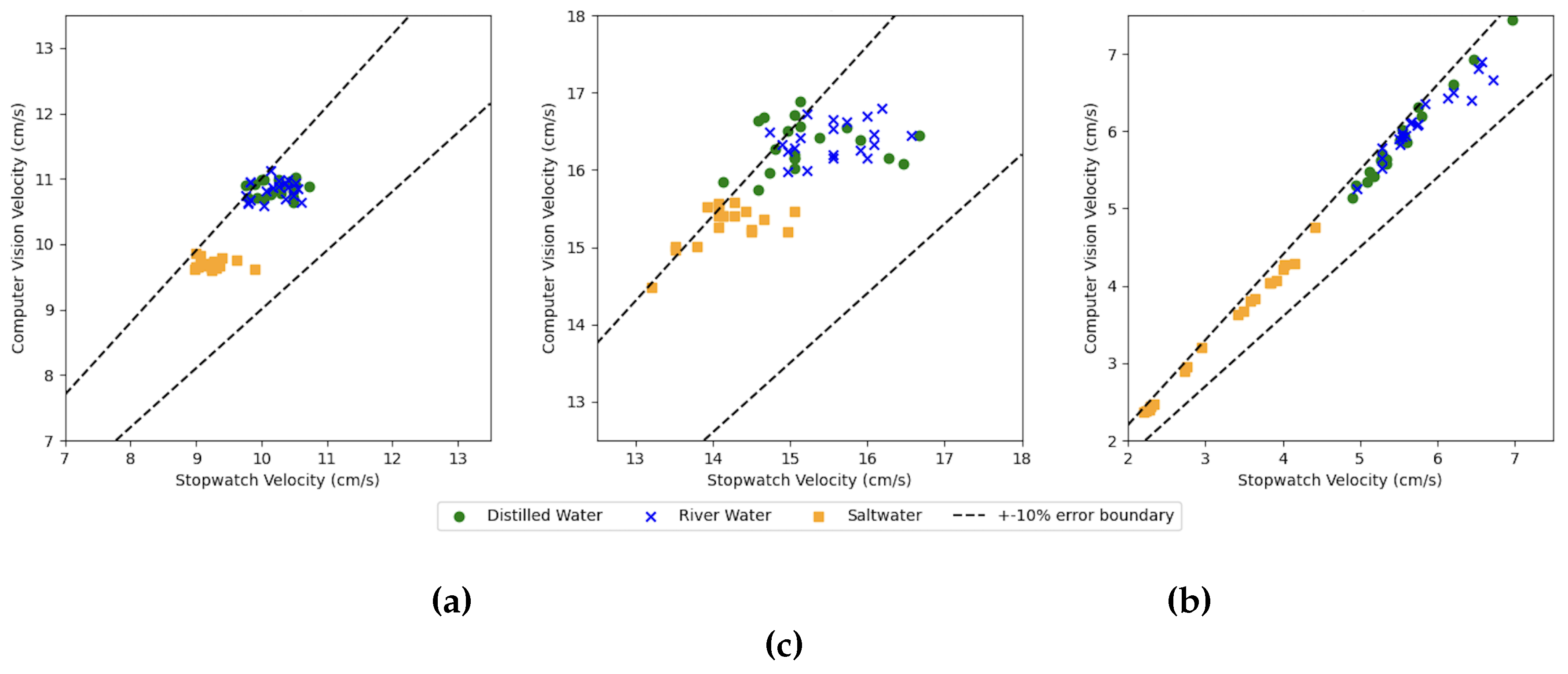

Development of a YOLOv12n-based AI-vision system designed to detect and track MPs during settling, with high accuracy across different water types (distilled, river, and seawater).

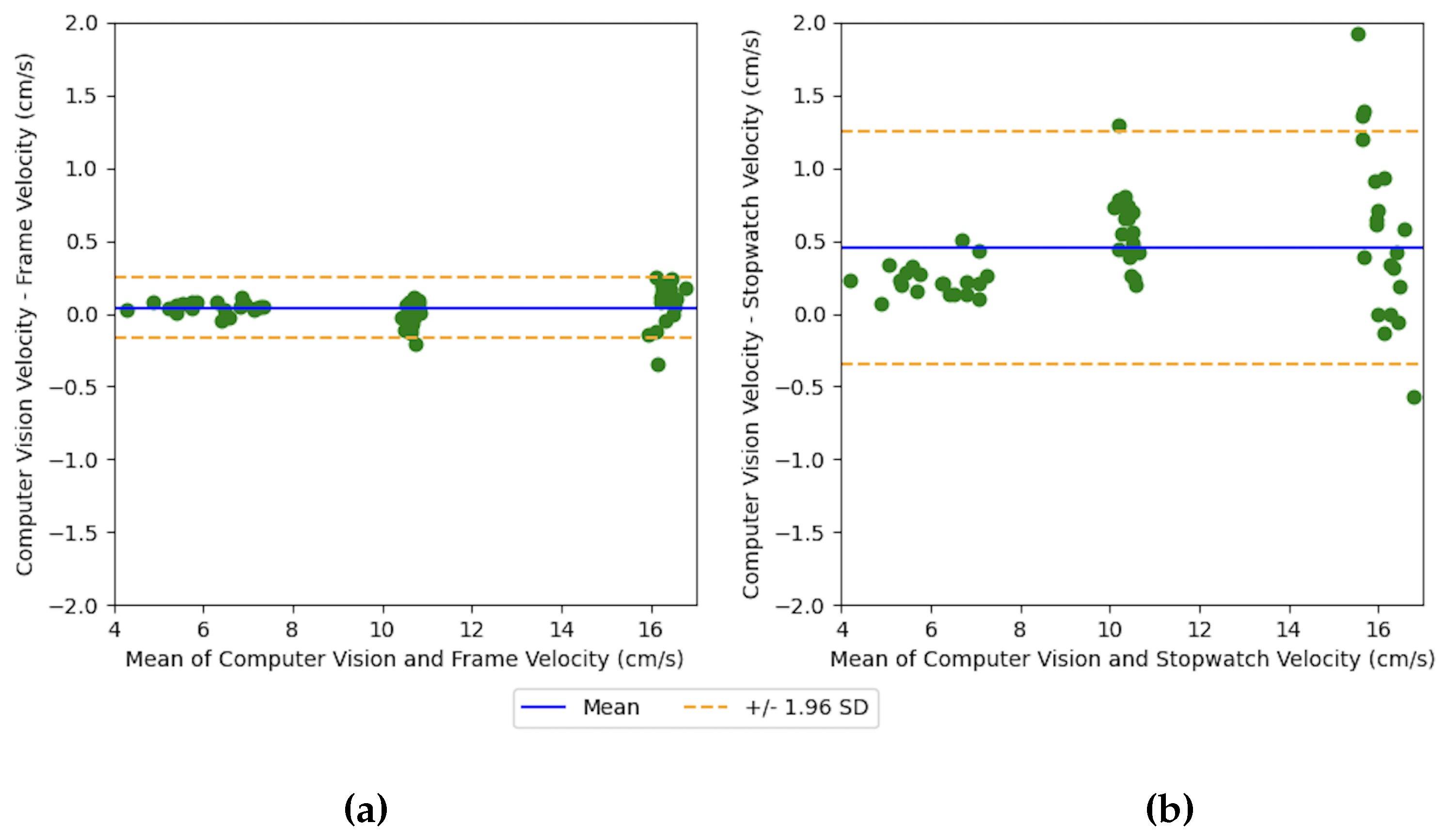

Quantitative assessment of system performance through comparison with ground-truth settling times measured via stopwatch and frame counts, enabling a rigorous evaluation of model accuracy.

Analysis of the influence of particle size, density, and water properties on settling velocity, using an automated method capable of generating reproducible measurements.

Creation of a labeled dataset of MP settling videos, which can support future research on AI-based detection and hydrodynamic modeling.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

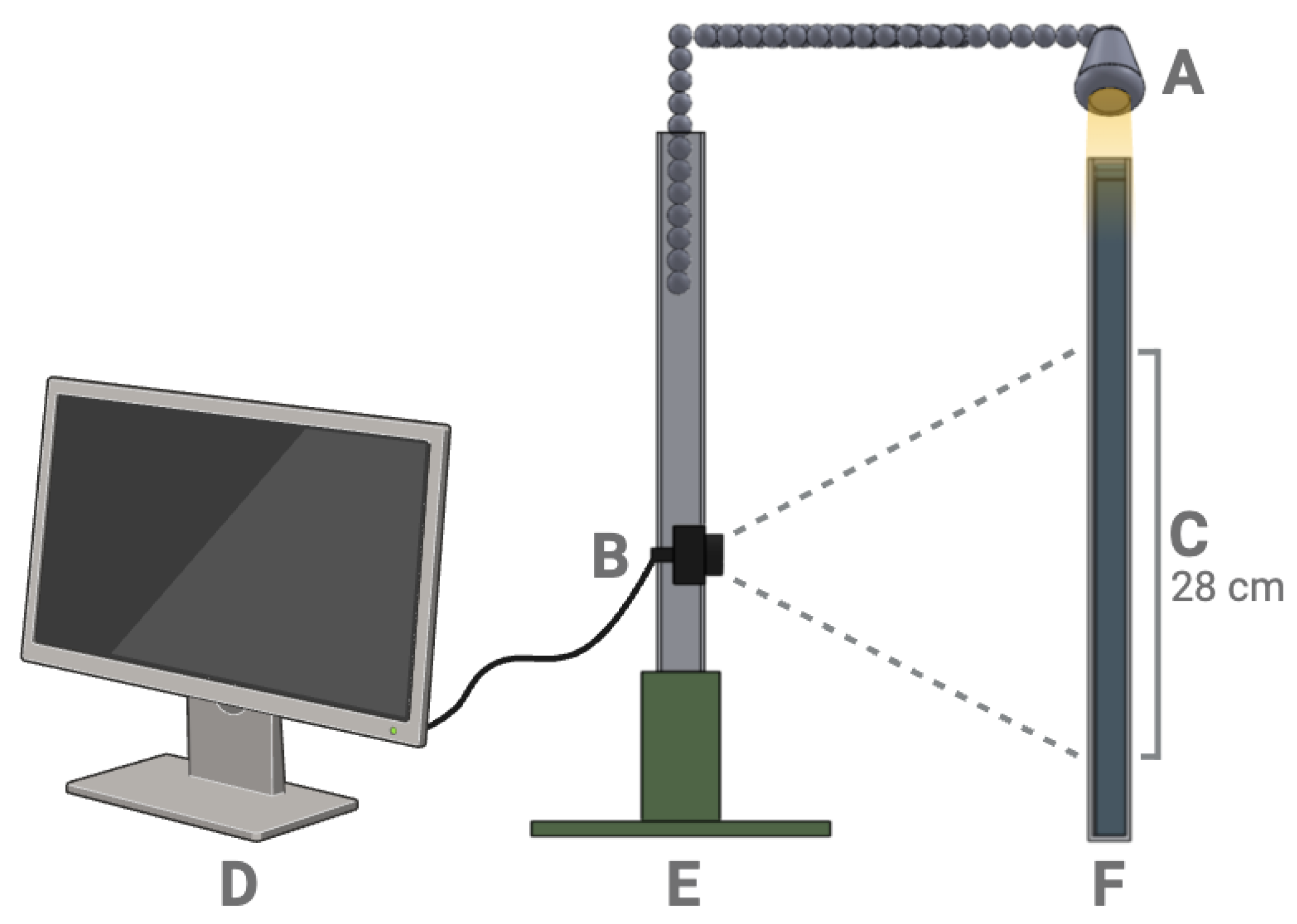

Section 2 describes the experimental setup, including the camera instrumentation, MP samples, and data acquisition procedures. The deep learning pipeline for object detection, tracking, and velocity calculation is also detailed.

Section 3 presents the results of both offline and real-time experiments, comparing the computer vision-derived settling velocities to ground-truth measurements and theoretical predictions. It also discusses the implications of the findings, including the role of AI in advancing MP research and potential applications to natural water bodies. Finally,

Section 4 summarizes the conclusions and highlights future research directions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.B.S. and M.H.I.; methodology, C.L.S. and M.A.B.S.; software, C.L.S.; validation, C.L.S., M.A.B.S. and M.H.I.; formal analysis, C.L.S.; investigation, C.L.S.; resources, M.H.I., A.B.M.B.; data curation, C.L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.S.; writing—review and editing, M.H.I., A.B.M.B. and C.L.S.; visualization, C.L.S.; supervision, M.A.B.S. and M.H.I.; project administration, M.A.B.S. and M.H.I.; funding acquisition, A.B.M.B and M.H.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.