1. Introduction

In the current context of environmental crisis and increasing pressure on water sources, understanding the interactions between human societies and ecosystems has become crucial. Socio-ecological systems (SES) are integrated systems that dynamically link social components, such as institutions and communities, with ecological components, including biodiversity and ecosystem services [

1]. These systems are characterised by their complexity, adaptability, and self-regulatory capacity in the face of external disturbances. From a resilience perspective [

2,

3], it should be emphasised that SES are not static but evolve through feedback cycles. Additionally, the fundamental vision of common-pool resource governance within these systems must be taken into consideration [

4]. Understanding SES allows for the design of sustainable strategies in response to global challenges, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and hierarchical social approaches (fields and power relations [

5]).

The conceptual framework of SES emerges as an alternative for adaptive water management. This perspective recognises the need to manage water under conditions of uncertainty, promoting institutional flexibility and continuous learning from an integrative vision that links ecological resilience with the active participation of communities [

6]. From another perspective, the role of social learning, governance, and institutional transformation is emphasised as central elements of adaptation [

7,

8]. Furthermore, the importance of experimentation and monitoring in multi-level adaptive water management processes is highlighted; these approaches, though diverse, concur that adaptively managing water requires flexible structures, effective participation, and a systemic understanding of the environment [

9].

It is essential to emphasise that this research prioritises co-learning among local communities, institutional actors, and academia, while also acknowledging the importance of recognising traditional knowledge as a fundamental contribution to Adaptive water management in territories. Such knowledge enables the incorporation of diverse territorial perspectives, thereby strengthening resilience and generating context-specific solutions [

1]. By integrating scientific and ancestral knowledge within this interdisciplinarity, social and ecological innovation is enhanced. This synergy improves collective decision-making and promotes more inclusive governance.

This review article, which addresses adaptive management based on co-learning and traditional knowledge, is structured around the following questions: What are the main thematic components that have been identified? Which studies exist, and how are these themes addressed jointly? What research gaps are identified? How can an SES-based approach promote adaptive water management through co-learning between local communities and institutional actors? To answer these questions, a theoretical synthesis is proposed, articulating the principal academic approaches to SES, adaptive water management, co-learning processes, Participatory Action Research (PAR), and traditional knowledge, conducting a literature review, highlighting the advances and contributions of various studies in these fields.

The structure of this article is divided into three sections: the first presents the materials and methods used to organise and select the relevant literature; the second outlines the results and discussion, addressing the research questions and integrating diverse disciplinary perspectives in order to propose a conceptual model that illustrates how the main components identified are interconnected; and the final section provides the conclusions drawn from this review.

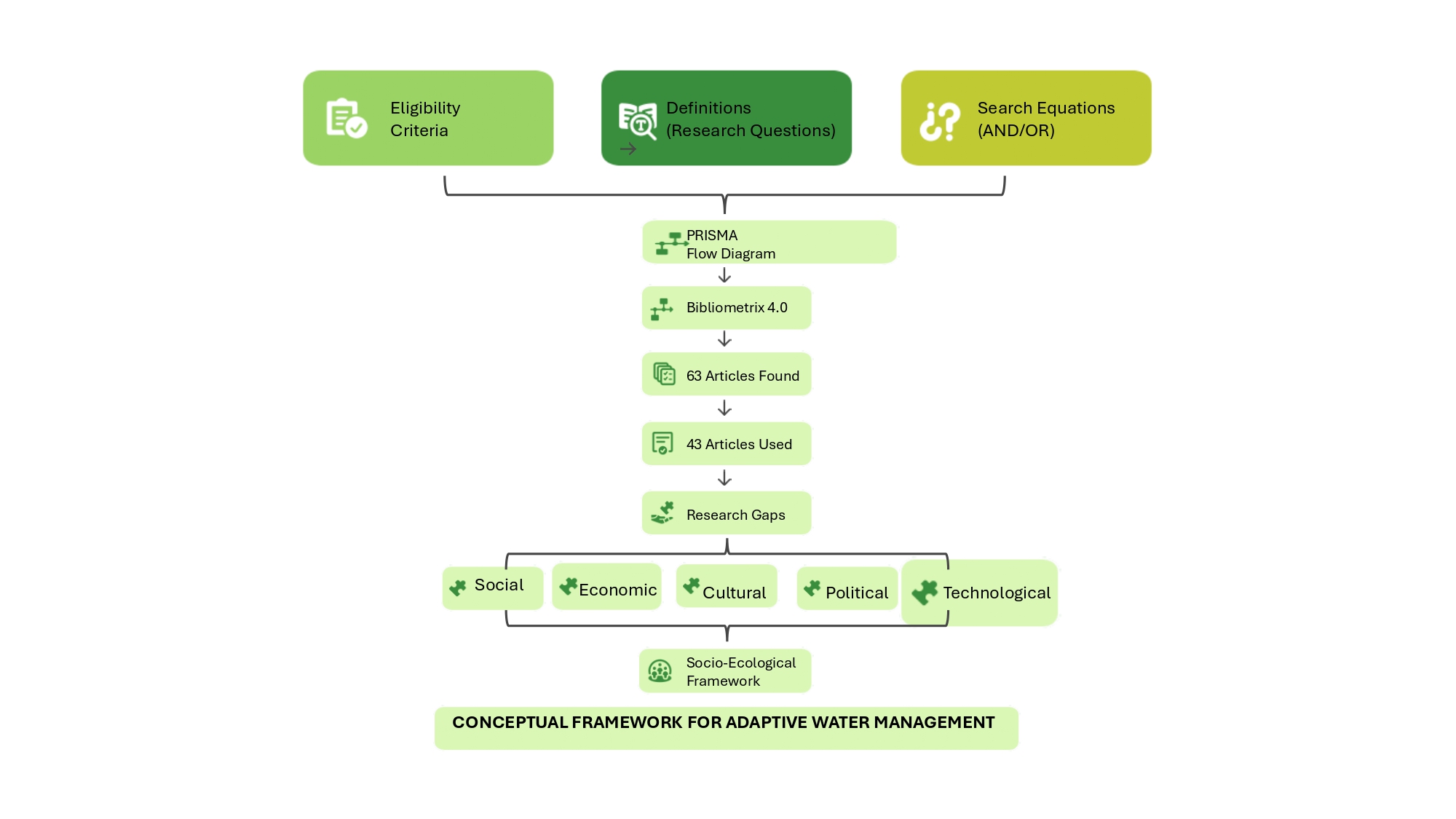

2. Materials and Methods

The present work adheres to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) systematic review protocol lines, which is a set of standards through a checklist of the following items [

10]:

a) Problem definition, concerning the following questions:

- What studies exist, and how do adaptive management, co-learning and traditional knowledge work together?

- What are the main thematic components and main contributions?

- What research gaps are identified?

-How can an approach based on Social-Ecological Systems (SES) promote adaptive water management through co-learning between local communities and institutional actors?

b) Eligibility criteria: Studies published in English, within the period from 2010 to 2025. The references of the selected articles were used as a research source to broaden the theoretical and conceptual analysis, as well as for the targeted identification of the core concepts examined in the study.

c) Databases: Scopus and Web of Science (WoS).

d) Keywords were identified to represent the research objective best, and the following search equation was applied: (“social-ecological system” OR “socio-ecological system” OR “SES”) AND (“adaptive water management” OR “adaptive management of water resources”) AND (social AND learning) AND (traditional AND knowledge).

Studies that contribute to the understanding of the interplay between co-learning, traditional knowledge, and adaptive water management were considered. For analysis, it was essential that the selected articles addressed the topic of adaptive water management and encompassed various dimensions of sustainability, including social, cultural, educational, political, economic, and technological aspects. Articles specifically focused on fields such as medicine and computer science were excluded from this analysis.

For the bibliometric review, the software Bibliometrix 4.0 [

11] was employed, which facilitates the execution, retrieval, representation, and processing of statistical data derived from bibliographic searches. Bibliometrics (the application of quantitative and statistical analysis to scientific publications such as journal articles) provides objective and reliable insights [

11], focusing on the examination of patterns and flows of documentary information that characterise and contribute to the advancement of scientific activity [

12]. Moreover, the use of relational bibliometrics through data visualisation techniques proves useful in delineating themes, publications, and authors, thereby enhancing the capacity to analyse and understand a particular field of study [

13].

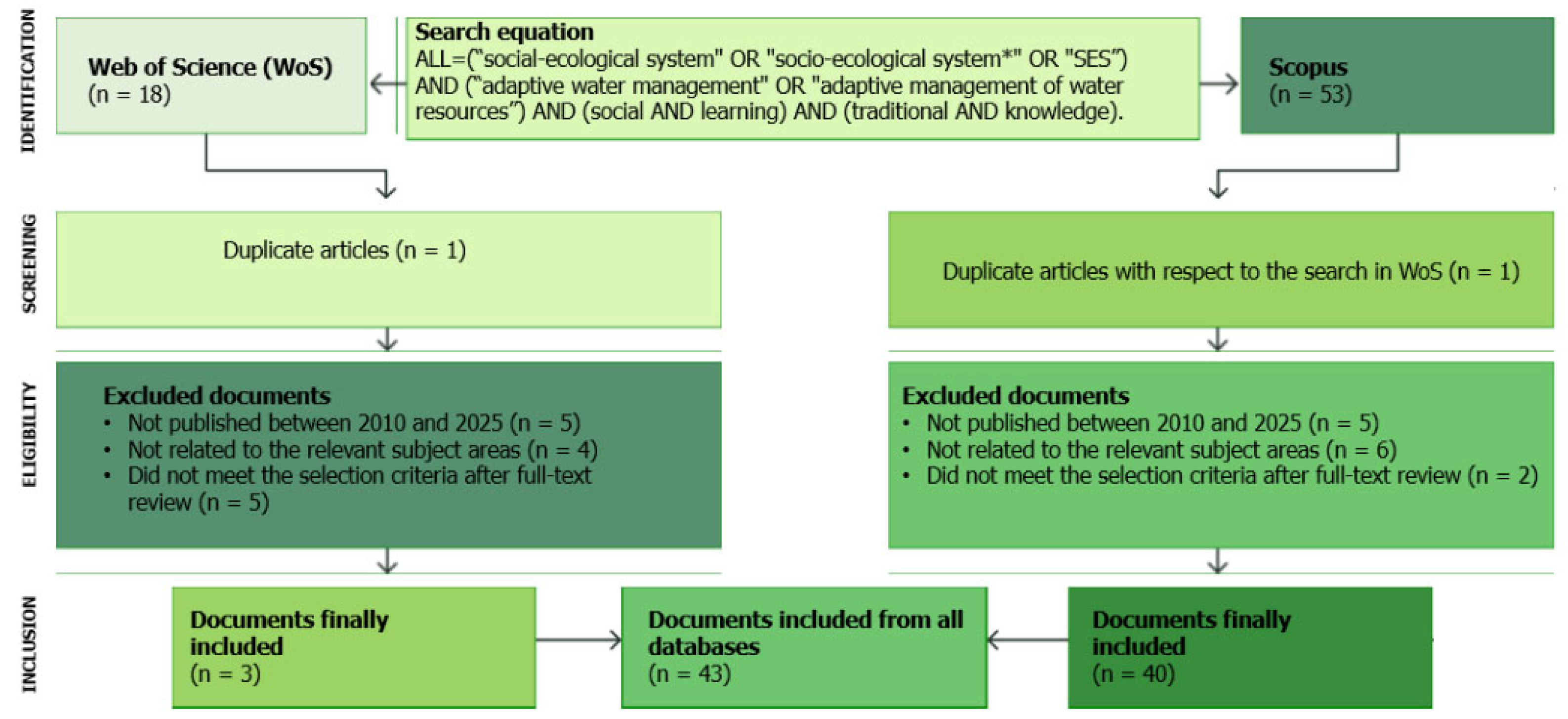

In the search process, the following fields were taken into account: title, keywords, and abstract. Applying the defined selection criteria to the sample and considering the period from 2010 to 2025, a total of 64 articles were identified. These were related to the topics of Social-Ecological Systems (SES), adaptive water management, co-learning, and traditional knowledge. After a detailed review of the documents, a final selection of 43 articles was made. This search process was carried out using the Scopus and Web of Science databases. The flow diagram of the search process, based on the PRISMA protocol, is presented in

Figure 1. Subsequently, the selected documents were exported to Bibliometrix in BibTeX format, including all available data.

3. Results

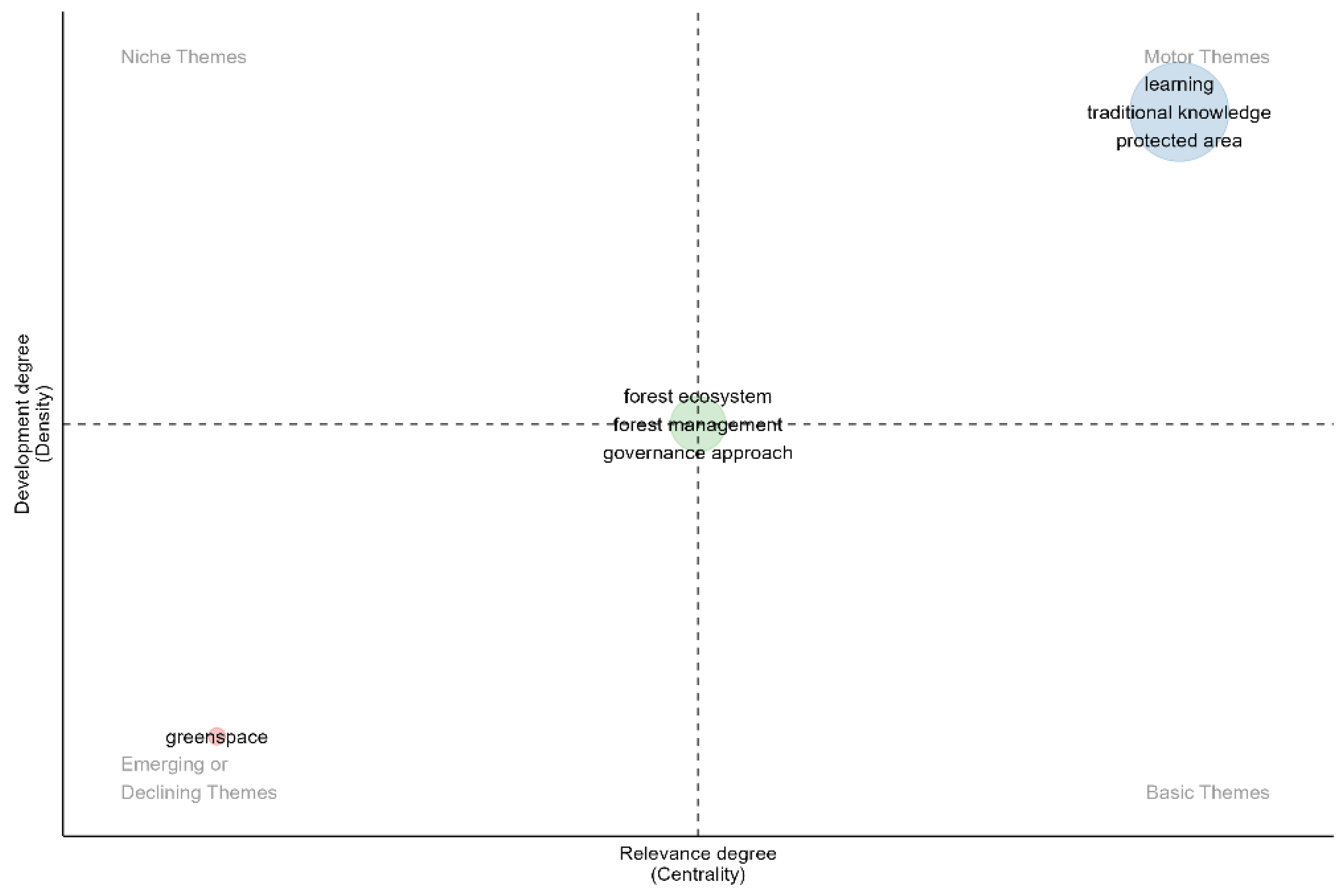

3.1. Thematic Map. Bibliometrix

Based on the data collected through Bibliometrix, conceptual structures were analysed using thematic maps. This technique relies on word networks, in which each network is represented by terms distributed across different quadrants [

14].

Figure 2, entitled Thematic Map, is structured around two indicator axes: density (vertical) and centrality (horizontal). In quadrant 2 (upper right), the main research themes—referred to as motor themes—can be observed. These include “learning, traditional knowledge, and protected areas”, which are identified as key or central topics within the field of study. These are well-developed themes that are also highly interconnected with other relevant topics in the research area. Likewise, in quadrant 3 (lower left), themes that are either emerging or in decline are represented. One such theme identified is “green spaces”. Based on the document analysis, it is suggested that “green spaces” constitute an emerging topic, currently in an early stage of conceptual development. It is framed within the discourse of sustainable development and is increasingly being considered within the educational field.

On the other hand, quadrant 4 displays basic themes that are regarded as transversal. Accordingly, the concepts of “governance, forest management, and forest ecosystems”, located near the centre (with medium density and centrality), are interpreted as transversal or growing themes. These are subjects that have already been addressed and continue to attract interest within the research domain. They are beginning to gain greater relevance, showing an intermediate level of development and interconnection with other topics. For instance, based on the bibliographic review, the theme of “approaches to governance” is being explored from various perspectives, with its conceptual and theoretical network still under construction.This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.2. Bibliometric Review: Thematic Analysis and Description of Common Content

To address the research questions: What studies exist, and how are adaptive management, co-learning, and traditional knowledge jointly approached? What are the main thematic components and key contributions? What research gaps can be identified? The studies identified were systematised.

Table 1 presents the principal contributions and the extent to which the approaches of adaptive management, co-learning, and traditional knowledge are integrated or not classified according to the most frequently occurring thematic components (social, ecological, cultural, economic, political, and technological); as well as the gaps that remain unaddressed in the analysed literature. It was found that most studies address two or three of these approaches, yet few integrate all three comprehensively. Thematically, the social component emerges as the most prominent, with a particular focus on water resource management and community resilience. However, the analysis reveals significant gaps in the systematic incorporation of traditional knowledge within the reviewed research.

3.3. Identification of Research Opportunities Based on Existing Knowledge Gaps

The identified research opportunities include: i) the potential to conduct long-term impact assessments of participatory projects, as few studies report outcomes over extended timeframes; ii) the need to consider the intersections of gender, power, and participation, given the limited attention paid to how inequalities shape participatory processes; iii) the integration of global and local scales, as there is still insufficient analysis of how local actions may influence change and inform regional, national, and global policies;

iv) the role of technology and digitalisation in rural contexts, since the contribution of digital tools to the co-production of knowledge remains underexplored; and v) the involvement of youth and future generations (intergenerational processes) in climate change and water governance, as their voices and experiences are scarcely represented in the bibliographic analysis conducted.

3.4. Promoting Adaptive Water Management Through Co-Learning

In addressing the question, how can an SES-based approach promote adaptive water management through co-learning between local communities and institutional actors? This analysis identifies various contributions aligned with SES-based frameworks, which offer an integrative perspective by acknowledging the interplay between social, ecological, and economic components. Some of the main contributions relate to: the recognition of complexity and interdependencies, emphasising that water-related decisions must adopt a more holistic understanding and take into account all social and ecological dimensions [

20]; the promotion of resilience and adaptability, by focusing on the capacity of systems to absorb and respond to change [

18,

21,

38,

40,

42]; the advancement of nature-based solutions [

23,

32,

34,

45], which include strategies to enhance water quality, availability, and regulation; and community engagement and governance [

21,

23,

29,

35,

43,

45], which involve inclusive decision-making processes tailored to local needs. The contributions of Social-Ecological Systems (SES) to adaptive water management involve the implementation of flexible actions and continuous evaluation to adjust strategies in accordance with observed outcomes.

Indeed, Participatory Action Research (PAR) constitutes a central methodological tool in various studies [

15,

19,

21,

22,

28,

35], employed across multiple disciplines. Similarly, the concept of adaptive governance is recurrent in ecological studies, urban planning, and climate risk management, fostering shared decision-making among local stakeholders, scientists, governmental bodies, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Resilience and adaptation to climate change are recurrent themes in the bibliometric analysis, as evidenced in studies concerning Pacific islands [

38], rural communities in Asia and Africa [

35,

42,

43], and agricultural systems [

17]. Accordingly, this concept is closely associated with the strengthening of local capacities. Furthermore, local, traditional, Indigenous, or endogenous knowledge is identified as fundamental in generating conceptual and sustainable solutions [

35,

40,

43].

It is also essential to emphasise that community education and communication emerge as key processes to facilitate learning and enhance resilience to climate change [

21,

22].

4. Discussion

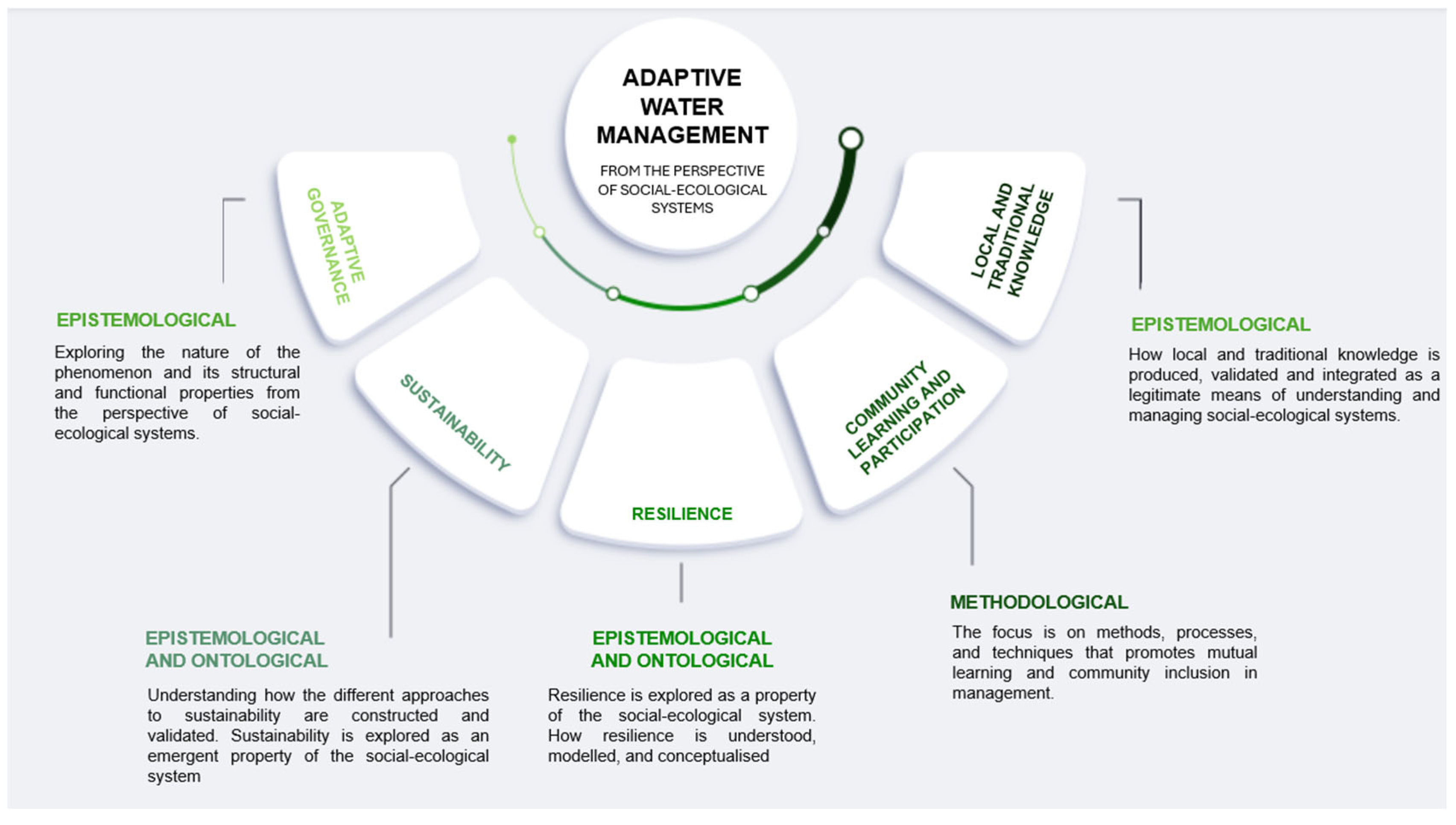

Proposed Conceptual Model

A conceptual model of adaptive water management is proposed from the perspective of socio-ecological systems, illustrating the interconnection among the main identified components. This model encompasses the dynamic interaction between systems, integrating the social and ecological subsystems into a unified framework “the human-in-nature” system a complex structure in which, for example, the social subsystem includes diverse human perceptions, behaviours, and ideas (values, knowledge, ideology, spirituality, arts, and culture), where social, institutional, economic, and political dimensions are intricately interwoven. In turn, the ecological subsystem encompasses all ecosystems (water, energy, air, soil, minerals, hydrology, climate, and the physical, chemical, and biological processes of the biosphere) [

49]. Understanding the dynamics of a socio-ecological system entails recognising its state and regime shifts.

The conceptual analysis conducted enabled the identification of five fundamental concepts that structure the theoretical framework of adaptive water management from a socio-ecological perspective.

Concept 1. Adaptive Governance is essential for addressing complexity, particularly in contexts of uncertainty such as climate change. Flexible and collaborative governance systems enhance adaptability through mutual learning, experimentation, and the coordinated management of natural resources. “Uncertainty in water availability demands polycentric, collaborative, and adaptive approaches” [

7,

50]. Adaptive governance strengthens the capacity to respond to hydrological uncertainties. It is thus well suited to water management in the context of climate change, as it fosters continuous monitoring, institutional flexibility, and the integration of diverse knowledge systems.

Concept 2. Local and traditional knowledge serves as a bridge to acknowledge and integrate indigenous and ancestral epistemologies, as it not only enriches adaptation strategies but also reinforces the legitimacy of interventions and empowers local communities. “Indigenous knowledge systems provide key insights for adaptive and culturally appropriate water management” [

51]. Local knowledge enhances context-specific water planning across territories. For instance, traditional understandings of water sources, rainfall cycles, and land use contribute to the development of more relevant and resilient strategies, particularly within Indigenous and rural territories [

52].

Concept 3. Co-learning and community participation foster innovation and adaptability in water management. Co-learning is understood as a collective process in which diverse actors ( local, institutional, academic, and political) share experiences, knowledge, and values. This exchange is essential for building consensus, fostering innovation in practice, and adapting to changes within the socio-ecological system [

53]. Such a process enables all social actors to acknowledge different perspectives and to co-design more resilient and sustainable solutions. “Social learning promotes the collective construction of meaning and serves as a critical foundation for the adaptive management of common resources such as water” [

54]. Initially conceived as a driver of social and ecological transformation, Participatory Action Research (PAR) is presented not merely as a methodology but as a key strategy to facilitate inclusive processes of change that integrate the voices and knowledge of communities into decision-making. “The active involvement of communities in water management enhances the legitimacy of policies and strengthens social learning” [

49]. PAR reinforces water governance by ensuring that local actors are not merely sources of information but co-creators of water solutions. This, in turn, strengthens the ownership of decisions and the long-term sustainability of actions.

Concept 4. Resilience from a socio-ecological systems perspective involves the integration of all stakeholders, as it aims to enhance the capacity of territories to adapt to and transform in the face of disturbances. “Water resilience is the outcome of systems that link ecological health with the capacity for social organisation” [

55,

56]. Water resilience depends on the interconnections between social and ecological components; therefore, a socio-ecological approach to water management enables the analysis of how communities respond to, adapt to, and transform in the face of extreme events such as droughts and floods.

Concept 5. Sustainability, which seeks lasting and sustainable solutions, emerges from participatory processes rooted in local contexts and territories, where communities lead the design of their paths to well-being and conservation, with the necessary technical and political support. “The sustainability of water depends on its management as a common good and on mechanisms of social control” [

57]. In other words, it is built through active participation, since without genuine participatory processes, efforts to conserve and distribute water often fail or perpetuate existing inequalities [

58].

Table 2 then identifies the main characteristics of the concepts and organises them according to their epistemological, ontological, and methodological functions [

59]. The table consists of three columns: the first presents the names of the concepts; the second indicates the main character of the research according to its function; and the third explains the justification for the selected characteristic.

Indeed, this conceptual model provides a comprehensive framework for inclusive water policies. The components of the model (governance, local knowledge, co-learning, resilience, and sustainability) do not function in isolation; rather, it is their synergy that enables the transition towards more equitable, sustainable, and resilient systems. “Integrated models allow knowledge to be translated into action and foster transformative changes in water management” [

58,

60].

In

Figure 3, these concepts are interwoven, representing a conceptual synthesis of the main theoretical components that have emerged throughout this research and underpin adaptive water management from a socio-ecological perspective. This representation is structured around three fundamental dimensions of scientific knowledge: ontological, epistemological, and methodological. Adaptive governance integrates diverse forms of knowledge, flexible institutional capacities, and participatory decision-making mechanisms under conditions of uncertainty; sustainability represents the desired state towards which the socio-ecological system converges: A dynamic balance between ecological, social, and economic dimensions; local knowledge emerges from the historical relationship between communities and their territories, providing a foundation for understanding and interpreting local water management dynamics; co-learning and community participation are key mechanisms for the collective construction of knowledge and the implementation of collaborative approaches to water resource management; and resilience, understood as a property of the socio-ecological system that enables adaptation, resistance, and transformation in the face of disturbances, constitutes a fundamental principle for adaptive management.

This graphic articulation enables the visualisation of the interdependence between key concepts, and illustrates how they simultaneously function as theoretical foundations, interpretative frameworks, and operational strategies in water management within complex and evolving contexts.

5. Conclusions

The conceptual model proposes an adaptive water management approach grounded in the socio-ecological perspective, wherein resilience and sustainability emerge from the interaction among communities, ecosystems, and diverse forms of knowledge. It promotes co-learning among local actors, technical experts, and authorities, thereby fostering horizontal processes of adaptive governance. This perspective recognises that traditional knowledge is not merely a complement, but a foundational pillar for designing water-related responses that are context-specific and culturally appropriate within territories.

Active participation in these processes fosters community empowerment, thereby strengthening the legitimacy of decision-making. In this way, socio-ecological systems become more flexible and better equipped to cope with climatic disturbances. In essence, the model advocates for a bottom-up transformation, in which the dialogue of knowledge drives social and ecological innovations. Water is thus managed as a common good, within a framework of justice and intergenerational equity.

Integrating traditional knowledge into water governance enables a shift from technocratic approaches to co-created systems, in which social learning plays a pivotal role in fostering adaptation and transformation. The model presented demonstrates that water resilience does not rely solely on infrastructure or scientific data, but rather on the collective capacity to learn from the environment and through interactions among diverse actors.

This systemic logic fosters trust-building, collaborative experimentation, and shared monitoring, all of which are essential to addressing climate uncertainty. Sustainability is not imposed from above, but rather constructed collectively, acknowledging the interdependence of social, ecological, and cultural elements. In this context, water management ceases to be merely technical and becomes a political and community-based practice. In doing so, pathways are opened towards a just, resilient, and life-centred water transition.

Going forward, this model offers a conceptual framework for understanding and addressing the complexity of adaptive water management in diverse contexts. It opens up new avenues of research for validation at various territorial and socio-environmental scales. Furthermore, its potential application as a decision-support tool for sustainable and participatory water planning is proposed, which could contribute to more equitable and resilient water management.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted under call 1123 for financial support towards tuition fees of the Doctoral Programme in Environmental Sciences at the University of Cauca, Colombia. The authors would like to express their special gratitude to the project entitled “Bioeconomic Strengthening for Social and Productive Reactivation through the Provision of Water-Related Ecosystem Services in the Context of Climate Change and the Challenges of COVID-19 in Priority Municipalities of the Department of Cauca” (BPIN 2021000100066, ID 5797), funded by the General System of Royalties.

References

- Berkes, F., Colding, J., & Folke, C. (2000). Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological applications, 10(5), 1251-1262.

- Holling, C. S. (1973, November). Resilience and stability of ecological systems., 4(1), (1973)1–23.

- Gunderson, L. H., & Holling, C. S. (2002). Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems (pp. xxiv+-507).

- Holling, C. S., & Allen, C. R. (2002). Adaptive inference for distinguishing credible from incredible patterns in nature. Ecosystems, 5(4), 319-328.

- Bourdieu, P., & Bourdieu, P. (1983). Campo del poder y campo intelectual (Vol. 7, pp. 3-44). Buenos Aires: Folios.

- Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P., & Norberg, J. (2005). Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour., 30(1), 441-473.

- Pahl-Wostl, C. (2008). Requirements for adaptive water management. In Adaptive and integrated water management: Coping with complexity and uncertainty (pp. 1-22). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Pahl-Wostl, C. (2009). A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global environmental change, 19(3), 354-365.

- Huitema, D., Mostert, E., Egas, W., Moellenkamp, S., Pahl-Wostl, C., & Yalcin, R. (2009). Adaptive water governance: assessing the institutional prescriptions of adaptive (co-) management from a governance perspective and defining a research agenda. Ecology and society, 14(1).

- Knobloch, K., Yoon, U., & Vogt, P. M. (2011). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and publication bias. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery, 39(2), 91-92.

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of informetrics, 11(4), 959-975.

- Mokhnacheva, Y. V., & Tsvetkova, V. A. (2020). Development of bibliometrics as a scientific field. Scientific and Technical Information Processing, 47(3), 158-163.

- Žujović, M., Obradović, R., Rakonjac, I., & Milošević, J. (2022). 3D printing technologies in architectural design and construction: A systematic literature review. Buildings, 12(9), 1319.

- López-Robles, J. R., Guallar, J., Otegi-Olaso, J. R., & Gamboa-Rosales, N. K. (2019). El profesional de la información (EPI): bibliometric and thematic analysis (2006-2017). El Profesional de la Información, 2019, vol. 28, num. 4.

- Correia, M. J., Chainho, P., Goulding, T., Carvalho, F., Cabral, S., Ferreira, F. G., & Vasconcelos, L. (2025). Participatory action research supporting adaptive governance of Manila clam fisheries. Marine Policy, 174, 106605.

- Markphol, A., Kittitornkool, J., Armitage, D., & Chotikarn, P. (2021). An integrative approach to planning for community-based adaptation to sea-level rise in Thailand. Ocean & Coastal Management, 212, 105846.

- Silici, L., Rowe, A., Suppiramaniam, N., & Knox, J. W. (2021). Building adaptive capacity of smallholder agriculture to climate change: evidence synthesis on learning outcomes. Environmental Research Communications, 3(12), 122001.

- Hidalgo, D. M., Nunn, P., & Beazley, H. (2021). Uncovering multilayered vulnerability and resilience in rural villages in the Pacific: a case study of Ono Island, Fiji. Ecology and Society, 26(1), 1-27.

- Lomofsky, D., & Grout-Smith, J. (2020). Learning to learn: The experience of learning facilitation for grantees of Comic-Relief-funded projects. African Evaluation Journal, 8(1), 480.

- Knapp, C. N., Reid, R. S., Fernández-Giménez, M. E., Klein, J. A., & Galvin, K. A. (2019). Placing transdisciplinarity in context: A review of approaches to connect scholars, society and action. Sustainability, 11(18), 4899.

- Meyer, M. A., Hendricks, M., Newman, G. D., Masterson, J. H., Cooper, J. T., Sansom, G., ... & Cousins, T. (2018). Participatory action research: Tools for disaster resilience education. International journal of disaster resilience in the built environment, 9(4/5), 402-419.

- Chen, M. H., Lin, Y. J., Liao, J. Y., & Lee, L. H. (2017). Important Bridges for Implementing Socio-Ecological Management in the Adiri Community of Pingtung, Taiwan after Typhoon Morakot. Taiwan J For Sci, 32(4), 317-31.

- Hochman, Z., Horan, H., Reddy, D. R., Sreenivas, G., Tallapragada, C., Adusumilli, R., ... & Roth, C. H. (2017). Smallholder farmers managing climate risk in India: 1. Adapting to a variable climate. Agricultural Systems, 150, 54-66.

- Coppock, D. L. (2016). Cast off the shackles of academia! Use participatory approaches to tackle real-world problems with underserved populations. Rangelands, 38(1), 5-13.

- Campos, I. S., Alves, F. M., Dinis, J., Truninger, M., Vizinho, A., & Penha-Lopes, G. (2016). Climate adaptation, transitions, and socially innovative action-research approaches. Ecology and Society, 21(1).

- McDougall, C., & Banjade, M. R. (2015). Social capital, conflict, and adaptive collaborative governance: exploring the dialectic. Ecology and Society, 20(1).

- Muzigirwa Muke, E. (2016). Organizaciones campesinas y lucha contra la pobreza en la República Democrática del Congo. Hacia un nuevo enfoque de desarrollo para una resiliencia sostenible basada en la agricultura familiar en un contexto de cambio climático en Kivu Sur. Muzigirwa Muke, E. (2016). Organizaciones campesinas y lucha contra la pobreza en la República Democrática del Congo. Hacia un nuevo enfoque de desarrollo para una resiliencia sostenible basada en la agricultura familiar en un contexto de cambio climático en Kivu Sur.

- McDougall, C., Jiggins, J., Pandit, B. H., Thapa Magar Rana, S. K., & Leeuwis, C. (2013). Does adaptive collaborative forest governance affect poverty? Participatory action research in Nepal’s community forests. Society & Natural Resources, 26(11), 1235-1251.

- Mackenzie, J., Tan, P. L., Hoverman, S., & Baldwin, C. (2012). The value and limitations of participatory action research methodology. Journal of hydrology, 474, 11-21.

- Harvey, B., Burns, D., & Oswald, K. (2012). Linking community, radio, and action research on climate change: Reflections on a systemic approach. IDS Bulletin, 43(3), 101-117.

- Sanginga, P. C., Kamugisha, R. N., & Martin, A. M. (2010). Strengthening social capital for adaptive governance of natural resources: A participatory learning and action research for bylaws reforms in Uganda. Society and Natural Resources, 23(8), 695-710.

- Hagmann, J., Chuma, E., Murwira, K., Connolly, M., & Ficarelli, P. (2002). Success factors in integrated natural resource management R&D: lessons from practice. Conservation Ecology, 5(2).

- Mendoza-Ato, A., Postigo, J. C., Choquehuayta-A, G., & Diaz, R. D. (2023). A conceptual model for rehabilitation of Puna grassland social–ecological systems. Mountain Research and Development, 43(4), D12-D20..

- Gaba, S., & Bretagnolle, V. (2020). Social–ecological experiments to foster agroecological transition. People and Nature, 2(2), 317-327.

- Fabricius, C., & Pereira, T. (2015). Community biodiversity inventories as entry points for local ecosystem stewardship in a South African communal area. Society & Natural Resources, 28(9), 1030-1042.

- Campbell, B., Hagmann, J., Sayer, J., Stroud, A., Thomas, R., & Wollenberg, E. (2006). What kind of research and development is needed for natural resource management?. Water International, 31(3), 343-360.

- Kura, Y., Mam, K., Chea, S., Eam, D., Almack, K., & Ishihara, H. (2023). Conservation for sustaining livelihoods: Adaptive co-management of fish no-take zones in the Mekong River. Fisheries Research, 265, 106744.

- Trundle, A., Barth, B., & McEvoy, D. (2019). Leveraging endogenous climate resilience: urban adaptation in Pacific Small Island Developing States. Environment and Urbanization, 31(1), 53-74.

- Carmichael, B., Wilson, G., Namarnyilk, I., Nadji, S., Brockwell, S., Webb, B., ... & Bird, D. (2018). Local and Indigenous management of climate change risks to archaeological sites. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 23(2), 231-255.

- Apgar, M. J., Allen, W., Moore, K., & Ataria, J. (2015). Understanding adaptation and transformation through indigenous practice: the case of the Guna of Panama. Ecology and Society, 20(1).

- Moller, H., O’Blyver, P., Bragg, C., Newman, J., Clucas, R., Fletcher, D., ... & Body, R. T. I. A. (2009). Guidelines for cross-cultural participatory action research partnerships: A case study of a customary seabird harvest in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 36(3), 211-241.

- Fisher, M. R., Bettinger, K. A., Lowry, K., Lessy, M. R., Salim, W., & Foley, D. (2022). From knowledge to action: multi-stakeholder planning for urban climate change adaptation and resilience in the Asia–Pacific. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 4(4), 339-353.

- Fisher, M. R., Workman, T., Mulyana, A., Institute, B., Moeliono, M., Yuliani, E. L., ... & Adam, U. E. F. B. (2020). Striving for PAR excellence in land use planning: Multi-stakeholder collaboration on customary forest recognition in Bulukumba, South Sulawesi. Land use policy, 99, 102997.

- Mapfumo, P., Onyango, M., Honkponou, S. K., El Mzouri, E. H., Githeko, A., Rabeharisoa, L., ... & Agrawal, A. (2017). Pathways to transformational change in the face of climate impacts: an analytical framework. Climate and Development, 9(5), 439-451..

- Campos, I., Vizinho, A., Coelho, C., Alves, F., Truninger, M., Pereira, C., ... & Penha Lopes, G. (2016). Participation, scenarios and pathways in long-term planning for climate change adaptation. Planning Theory & Practice, 17(4), 537-556.

- Nidumolu, U., Adusumilli, R., Tallapragada, C., Roth, C., Hochman, Z., Sreenivas, G., ... & Ratna Reddy, V. (2021). Enhancing adaptive capacity to manage climate risk in agriculture through community-led climate information centres. Climate and Development, 13(3), 189-200.

- Gerger Swartling, Å., Tenggren, S., André, K., & Olsson, O. (2019). Joint knowledge production for improved climate services: Insights from the Swedish forestry sector. Environmental Policy and Governance, 29(2), 97-106.

- Z. Hochman, H. Horan, D. R. Reddy, G. Sreenivas, C. Tallapragada, R. Adusumilli,... & C. H. Roth, Smallholder farmers managing climate risk in India: 1. Adapting to a variable climate. Agricultural Systems, 2017, vol. 150, p. 54-66.

- Raskin, P. (2006). World lines: Pathways, pivots and the global future. Great Transition Initiative. https://www. gtinitiative. org.

- Castillo-Esparcia, A., Fernández-Souto, A. B., & Puentes-Rivera, Comunicación política y COVID-19. Estrategias del Gobierno de España. Profesional de la información, 2020, vol. 29, no 4.

- Armitage, C. J., Norman, P., Alganem, S., & Conner, M. (2015). Expectations are more predictive of behavior than behavioral intentions: Evidence from two prospective studies. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(2), 239-246.

- Boelens, R., Cremers, L., & Zwarteveen, M. (2011). Justicia Hídrica: acumulación de agua, conflictos y acción de la sociedad civil. Justicia hídrica: acumulación, conflicto y acción social, 13-22.

- Vedwan, N. (2006). Culture, climate and the environment: Local knowledge and perception of climate change among apple growers in northwestern India. Journal of Ecological Anthropology, 10(1), 4-18.

- Reed, M. S., Evely, A. C., Cundill, G., Fazey, I., Glass, J., Laing, A., ... & Stringer, L. C. (2010). What is social learning?. Ecology and society, 15(4).

- Pahl-Wostl, C. (2006). The importance of social learning in restoring the multifunctionality of rivers and floodplains. Ecology and society, 11(1).

- Folke, C. (2006). Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global environmental change, 16(3), 253-267.

- Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., Biggs, D., Bohensky, E. L., BurnSilver, S., Cundill, G., ... & West, P. C. (2012). Toward principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services. Annual review of environment and resources, 37(1), 421-448.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge university press.

- Jabareen, Y. (2009). Building a conceptual framework: philosophy, definitions, and procedure. International journal of qualitative methods, 8(4), 49-62.

- Meinzen-Dick, R. (2007). Beyond panaceas in water institutions. Proceedings of the national Academy of sciences, 104(39), 15200-15205.

- Dewulf, J., Benini, L., Mancini, L., Sala, S., Blengini, G. A., Ardente, F., ... & Pennington, D. (2015). Rethinking the area of protection “natural resources” in life cycle assessment. Environmental science & technology, 49(9), 5310-5317.

- Lebel, L., Anderies, J. M., Campbell, B., Folke, C., Hatfield-Dodds, S., Hughes, T. P., & Wilson, J. (2006). Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional social-ecological systems. Ecology and society, 11(1).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).