1. Vitamins in Vascular Health

Vascular health depends on the integrity and function of endothelial cells, which line the interior surface of blood vessels. In degenerative disorders (including disorders as varied as age-related macular degeneration, or lymphedema), a diminished absorption of these vitamins leads to poorer vascular health, which exacerbates the disorder [

1,

2]. Vitamins, particularly B-group vitamins, as well as vitamins C, D, and E, play crucial roles in maintaining endothelial health, supporting cellular functions such as DNA synthesis, methylation, cell repair, and modulation of oxidative stress. This chapter focuses on the vitamins essential for vascular health, with a special emphasis on vitamin B9 (folate), its forms, bioavailability, and the consequences of deficiency.

1.1. Vitamins Essential for Endothelial Health: Folate

Folate (Vitamin B9) is essential for one-carbon metabolism, which supports DNA and RNA synthesis, facilitating cell division and repair [

3,

4,

5]. Folate in one-carbon metabolism also supports methylation reactions, which regulate genes, as well as amino acid metabolism [

4].

Folate is also involved in the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. Reducing homocysteine lowers its toxicity that can otherwise harm blood vessels [

3,

6].

There are two forms of dietary folate. The natural form is found in foods (leafy greens, legumes, liver). It is reduced, but requires conversion in the body to the active utilized by cells [

3,

5].The synthetic, more stable form is oxidized, and is used in supplements and food fortification. It is better absorbed (~85% bioavailability) than food folate (~50%), but must first be reduced before it can be converted to the active form (5-methyltetrahydrofolate, or 5-MTHF) in the liver and digestive tract [

3,

5].

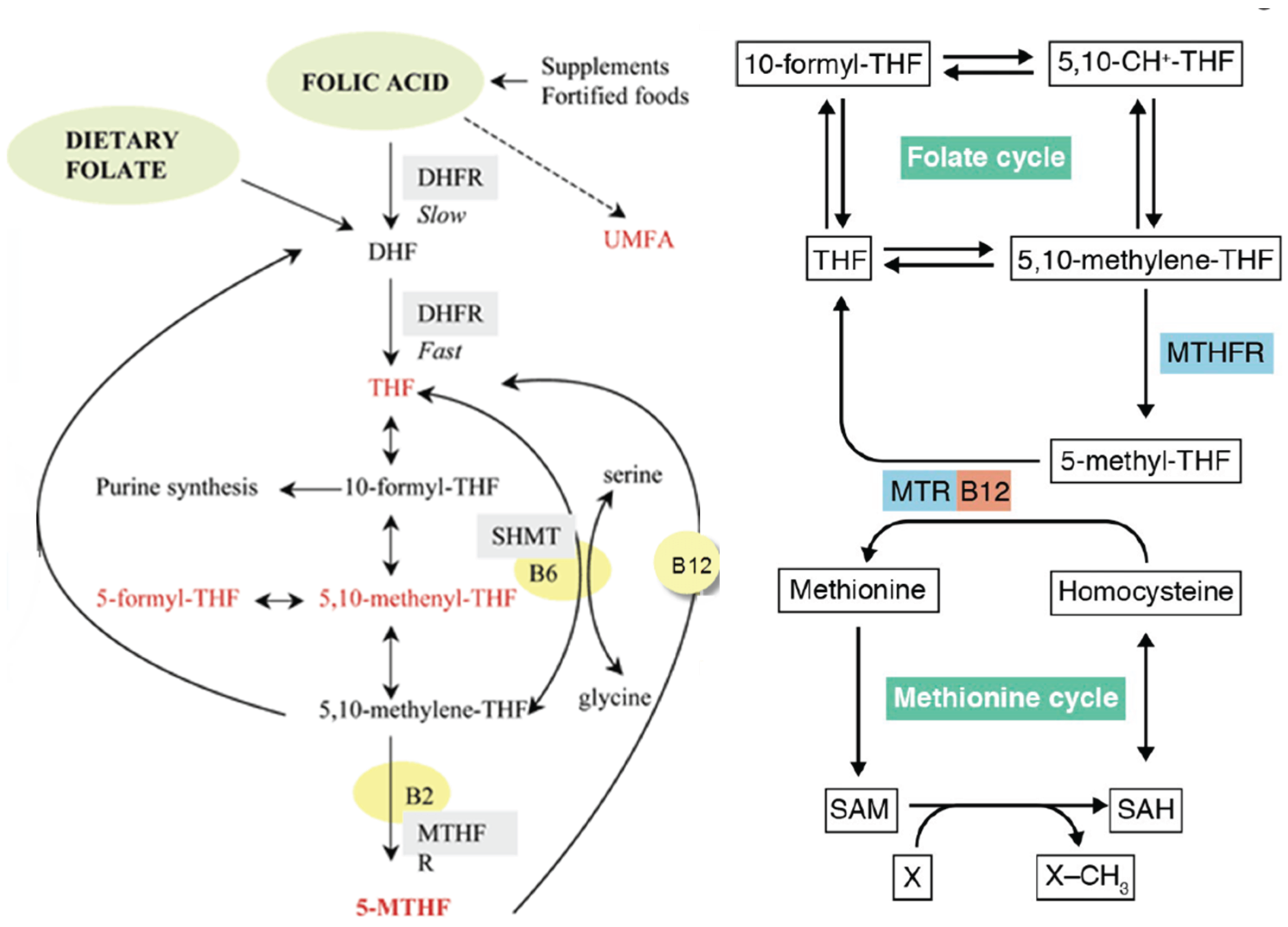

Figure 1 shows the pathways of dietary folate and folic acid and their conversion to 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF), which is the biologically active form [

6]. While supplements typically contain the synthetic folic acid due to its long-term stability, some use 5-MTHF.

1.1.1. Steps in the Folate Pathway

Dietary folates (mainly polyglutamated forms) are deconjugated to monoglutamate forms in the small intestine and absorbed via specific transporters (e.g., proton-coupled folate transporter). Once in the bloodstream, folate is transported to tissues and taken up by cells through reduced folate carriers (RFC) and folate receptors [

5,

9].

Inside cells, folate is reduced to dihydrofolate (DHF) and then to tetrahydrofolate (THF) by the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). THF acts as a carrier of one-carbon units in various oxidation states, forming derivatives such as 5,10-methylene-THF, 5-methyl-THF, and 10-formyl-THF [

5,

10].

THF derivatives participate in purine and thymidylate (dTMP) synthesis (for DNA/RNA); methionine regeneration from homocysteine (via 5-methyl-THF and methionine synthase); and methylation reactions (via S-adenosylmethionine, SAM) [

5].

Folate metabolism occurs in both the cytosol and mitochondria, with specific enzymes and folate forms in each compartment. Folate metabolism is tightly regulated, and cells possess repair mechanisms for damaged folate molecules [

10,

11].

1.1.2. Folate Deficiency and Vascular Dysfunction

Folate deficiency leads to impaired DNA synthesis, megaloblastic anemia, elevated homocysteine, and it increases the risk of vascular dysfunction, including atherosclerosis, stroke and degenerative diseases [

3,

4]. Elevated homocysteine due to low folate impairs endothelial function and increases oxidative stress, a key factor in vascular disease [

3,

6].

Supplementation with folic acid or 5-MTHF can improve endothelial function, especially in those with cardiovascular risk or established disease, by increasing nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and reducing oxidative stress [

3,

6,

12]. Mandatory folic acid fortification in USA has reduced rates of neural tube defects and improved population folate status, but concerns remain about unmetabolized folic acid with high supplementation, as it may interfere with cellular access or use of 5-MTHF [

4,

5].

1.2. Vitamins Essential for Endothelial Health: Pyridoxine and Cobalamin

Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) and B12 (Cobalamin) are both co-factors in homocysteine metabolism, working synergistically with folate to convert homocysteine to methionine [

3,

5]. Vitamin B6 acts as a coenzyme in the transsulfuration pathway, converting homocysteine to cystathionine and then to cysteine. Adequate B6 prevents hyperhomocysteinemia, thereby supporting endothelial function [

3]. Additionally, B6 modulates the expression of adhesion molecules and inflammatory cytokines, protecting against endothelial activation and subclinical vascular inflammation [

13].

Vitamin B12, in concert with folate, is essential for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine. Insufficiency exacerbates homocysteine elevation and related vascular threats [

14]. Vitamin B12 is also necessary for myelin synthesis and repair. For this reason, it is a promising treatment for neuropathic pain, as it may promote myelination and increase nerve regeneration [

15].

Both vitamins are readily absorbed from dietary and supplemental sources. They both support DNA synthesis and repair [

4]. Absorption can be impaired in common conditions, including aging and gastrointestinal disorders) [

5]. Additionally, deficiencies can lead to elevated homocysteine, which creates an increased cardiovascular risk [

16].

1.3. Vitamins Essential for Endothelial Health: Ascorbic Acid

Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) is a powerful antioxidant. It neutralizes reactive oxygen species, thus reducing oxidative stress-induced dysfunction. It is active in the regeneration of nitric oxide, which enhances vasodilation, thus reducing hypertension risk, by facilitating NO bioavailability. Vitamin C protects endothelial cells from oxidative damage. It supports collagen synthesis, which is important for the integrity of the vascular lining [

3,

17]

Vitamin C is highly bioavailable from fruits and vegetables. It is water-soluble and rapidly absorbed [

3].

1.4. Vitamins Essential for Endothelial Health: Vitamin D

Vitamin D receptors are expressed in endothelial cells, and activation suppresses pro-inflammatory gene expression while enhancing anti-inflammatory signals. It thus modulates inflammation and immune function in the endothelium, supporting vascular resilience [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. A vitamin D deficiency reduces endothelial conductance and increases arterial stiffness [

22].

Vitamin D influences the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, modulating blood pressure and thus supporting vascular tone via blood pressure regulation [

19]. A recent meta-analysis finds an association of CVD with low serum vitamin D, with supplementation reducing CVD [

20].

Vitamin D is produced in the skin via sunlight exposure. It is also available in fortified foods and supplements [

3,

17].

1.5. Vitamins Essential for Endothelial Health: Tocopherol and Vitamin K2

Vitamin E (Tocopherol), especially alpha-tocopherol, is a lipid-soluble antioxidant in cell membranes, protecting endothelial cells from lipid peroxidation. It reduces LDL oxidation and plaque formation and may modulate inflammation and platelet aggregation in blood vessels [

3,

18].

Vitamin E is absorbed with dietary fats. It is found in nuts, seeds, and vegetable oils [

3].

Vitamin K2 helps to regulate soft tissue stiffness by activating an anti-calcific protein. Prevalence of vitamin K deficiency in the USA is high. Because vitamin K2 reduces arterial stiffness, it thus plays a role in reducing CVD [

23].

1.6. Public Health Aspects

1.6.1. Nutritional Sufficiency

Population studies underscore the prevalence of suboptimal vitamin intake and its correlation with atherosclerotic disease progression and adverse vascular outcomes. Surveys continue to show many individuals, including in developed nations, fall short of optimal vitamin intake, especially B9, B12, D, and C [

18,

24,

25].

1.6.2. Genetic Polymorphisms

Polymorphisms in genes encoding enzymes for folate and homocysteine metabolism such as MTHFR increase the need for bioavailable forms of folate (such as 5-MTHF). These gene variants may exacerbate deficiencies and vascular risk. In these cases, direct 5-MTHF supplementation is beneficial [

4,

26].

1.6.3. Supplementation and Disease Prevention

Mandatory folic acid fortification has lowered neural tube defect rates. This supplementation must be balanced against issues in those unable to efficiently convert folic acid to its bioactive form. There is increasing evidence that non-deficient individuals and those with gene variants may be negatively impacted by folic acid supplementation [

12,

18].

Vitamins are indispensable for vascular health through their diverse roles in endothelial cell function, regulation of oxidative and inflammatory processes, and homocysteine metabolism. Timely identification and correction of deficiencies, targeted supplementation in at-risk individuals, and a foundation of nutrient-rich dietary habits are all strategies with significant potential to reduce vascular disease burden and promote healthy aging.

2. Folate Sources, Absorption and Bioavailability

Vitamin B9, commonly known as folate, is an essential water-soluble B vitamin required for DNA synthesis, amino acid metabolism, and key methylation reactions.

Folate exists in both natural forms found in many food products and as a synthetic compound, folic acid, used in supplementation and food fortification. The natural forms are reduced in form and folic acid is oxidized, making it stable for long periods of time. Understanding natural and synthetic sources, comparative bioavailability, and the impact of genetic variation on folate metabolism is critical for optimizing health and preventing deficiency-related conditions [

4,

25,

27,

28].

2.1. Folate from Foods

Folate occurs naturally in several foods. Food products with the highest folate concentrations are shown in

Table 1. Among these, spinach, liver, asparagus, and Brussels sprouts are particularly folate-rich [

26,

28]. The dominant forms of folate in foods are polyglutamated tetrahydrofolates (such as 5-methyltetrahydrofolate), which are critical for metabolic functions. The glutamate residues are removed in the gut and liver to provide the active 5-MTHF used by cells [

29].

Folic acid is mono-glutamate, and is fully oxidized and stable. It is chemically distinct from natural food folate in that it does not require deconjugation or release from plant matrices. Fortified foods and supplements provide reliable, high bioavailability forms of folic acid, compensating for losses from natural sources and helping reduce deficiency rates [

28,

30,

31]. Folic acid is present in fortified grains and dietary supplements.

Another form of folate is found in medical foods. These are products that contain L-methylfolate (5-MTHF), a bioactive form used in certain clinical situations, and folinic acid (leucovorin), a bioactive form used in cancer therapy to replace folate depleted by chemotherapy and used as a treatment to alleviate communication symptoms in autism [

32].

2.2. Bioavailability and Absorption

The bioavailability of naturally occurring folate is inherently variable and generally limited, compared to synthetic folic acid. Typical estimates are that natural food folate is about 50–60% as bioavailable as folic acid consumed with a meal [

5,

27,

33].

Three factors affect natural folate bioavailability. These are that folate can be tightly bound within plant cell structures; that natural folate is polyglutamated, which requires enzymatic deconjugation before absorption; and that folate is susceptible to heat, light, and oxidation, so losses can occur during cooking and storage [

5,

27,

33].

Emerging research suggests that, depending on the food and preparation, bioavailability may range from roughly 44% to 80%, with a median estimate around 65% as compared to synthetic folic acid [

27,

33,

34]. This variability, along with incomplete liberation from the food matrix and sensitivity to food processing, is a key reason public health campaigns emphasize folic acid fortification, and why this fortification has successfully raised population folate status and reduced the incidence of neural tube defects [

5,

28].

2.3. Genetic Influences on Folate Metabolism

Several common genetic polymorphisms influence folate absorption, metabolism, and the body’s methylation capacity.

MTHFR (Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase) gene

C677T and

A1298C polymorphisms affect the conversion of folic acid and food folates to the bioactive 5-MTHF form. This impacts homocysteine levels and increases susceptibility to neural tube defects and to ASD in certain populations [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Individuals with these variants may have higher homocysteine levels and may benefit from supplementation with L-methylfolate rather than folic acid [

1,

7,

39].

MTR,

MTRR,

FOLH1,

RFC1, and

SHMT genes. These variants can influence absorption, tissue distribution, and utilization of folate, with downstream effects on DNA methylation and health outcomes [

35,

36,

37,

38].

DHFR (dihydrofolate reductase). Variability in DHFR activity can affect the reduction of folic acid to tetrahydrofolate, influencing how efficiently synthetic folic acid is utilized. Excess folic acid may accumulate in individuals with low DHFR activity [

40].

2.3. Folate Transport into the Brain

Folate must cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to support neurological function. This process is mediated by at least two specific transport proteins. Folate receptor alpha (FRα) is essential for high-affinity transportation of folate across the choroid plexus into the cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue. Mutations in the FOLR1 gene can cause cerebral folate deficiency, leading to neurological symptoms [

41].

The reduced folate carrier (RFC,

SLC19A1) facilitates folate entry into various tissues, including the brain. Genetic variations in the RFC gene can influence folate delivery to the central nervous system. Recent research also implicates the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in the regulation of folate transport across the BBB, especially in certain neurological diseases [

42,

43].

Disruption of these transport mechanisms, whether by genetic mutations, autoantibodies, or disease, can result in cerebral folate deficiency, a low brain folate level, even when blood folate status appears normal. Supplementation with folinic acid (a reduced folate form) can sometimes bypass these defects and restore brain folate levels [

43].

These genetic factors help explain differences between individuals in folate requirements, the varied responses to supplementation, and the risk for conditions linked to both plasma folate deficiency and cerebral folate deficiency, including birth defects, cardiovascular disease and autism spectrum disorder [

35,

36,

37,

38].

Research continues to elucidate the interaction between genetic variation, environmental exposures, and folate-dependent pathways, pointing to a future with more personalized recommendations on folate intake [

44].

3. Cardiovascular Health

Folate improves endothelial function both by lowering homocysteine and through homocysteine-independent mechanisms. Evidence from human clinical studies demonstrates folate can enhance vascular reactivity and may reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, particularly in at-risk populations with low baseline folate or elevated homocysteine. The cardiovascular benefit of folate is dose-dependent, and excessive supplementation may pose risks.

Other vitamins, notably B6, B12, C, D, E, and K, play complementary roles in promoting vascular health through antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and structural vessel support mechanisms.

3.1. Folate and Endothelial Function

Folate plays a critical role in one-carbon metabolism, particularly in the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, as described above. Elevated homocysteine is recognized as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Mechanistically, high homocysteine levels can promote endothelial dysfunction via increased oxidative stress, impaired nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, and direct endothelial injury. By facilitating the conversion of homocysteine to methionine, folate supplementation lowers plasma homocysteine concentrations and may limit these deleterious vascular effects [

6,

12,

45,

46].

Moreover, folate exerts endothelial benefits independent of lower homocysteine levels. Experimental studies have demonstrated that folate in the form of folic acid and its bioactive metabolite, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, can directly enhance endothelial function, possibly by reducing intracellular superoxide availability and improving NO production in endothelial cells [

6,

12]. This provides a plausible explanation for observed improvements in endothelial-dependent vasodilation with folate, even when reductions in homocysteine are modest or absent.

Endothelial dysfunction is a central feature in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, preceding plaque formation and influencing the progression of established disease. Improvements in endothelial function, assessed via flow-mediated dilation (FMD), correspond with reduced cardiovascular risk [

12,

47]. Both hyperhomocysteinemia and suboptimal folate status have been linked epidemiologically and mechanistically to increased cardiovascular risk.

3.2. Evidence for Improved Blood Flow

Multiple studies provide evidence that folate, along with adequate intake of other B vitamins such as B6 and B12, improves vascular reactivity and blood flow. In animal models, folate supplementation has reversed endothelial dysfunction caused by hyperhomocysteinemia [

3].

In humans, several randomized controlled trials and observational studies have shown that high-dose folic acid (5–10mg/day) improves FMD and overall endothelial function in patients both with and without hyperhomocysteinemia [

6,

12,

47,

48]. Notably, the effect on vascular health often occurs even before major changes in homocysteine levels are detected, indicating alternative protective mechanisms such as enhanced antioxidant defense and direct effects on NO production.

Beyond folate, vitamins C, E, D, and K—through their antioxidant properties, blood pressure regulation, and support of blood vessel health—contribute to better circulation and may reduce atherosclerosis and peripheral vascular disease risk [

2,

49].

3.3. Clinical Evidence

Trials in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) demonstrate that folic acid supplementation (5 mg for 6 weeks) increases plasma folate and improves FMD, a measure of endothelial function, even when the reduction in homocysteine is moderate [

6,

12,

47]. Meta-analyses suggest that folic acid supplementation is associated with a modest reduction in overall cardiovascular events and stroke risk, particularly in individuals with low baseline folate status or significant homocysteine elevation. The most pronounced benefits are seen in primary rather than secondary prevention [

50].

While moderate folate intake is associated with reduced cardiovascular mortality, some data suggest that excessive folic acid supplementation may not continue to provide incremental benefits and could even have potential adverse effects at the highest intake levels [

51,

52,

53]. This may be due to the limits of how much folic acid can be converted to bioavailable folate each day. There is increasing evidence that unmetabolized folic acid reduces availability of folate to cells [

54,

55].

Additionally, large randomized trials in selected populations (e.g., chronic kidney disease) have not consistently demonstrated reduced cardiovascular events after long-term folate supplementation, emphasizing the importance of individual risk, baseline folate status, and other confounding factors [

56].

The outcomes of the published trials are summarized in

Table 2.

4. Peripheral Circulation, Lymphedema and Glymphatic Function

Folate plays a multifaceted role in circulatory health, improving endothelial function, supporting nitric oxide production, and potentially enhancing both blood and lymphatic flow. Clinical evidence suggests benefits in peripheral artery disease and lymphedema, with promising implications for lymphatic function. While the impact of folate on the glymphatic system remains speculative, its established vascular effects provide a rationale for future investigation into its role in brain waste clearance and neurodegenerative disease prevention [

57,

58].

4.1. Folate and Peripheral Circulation

Folate has been shown to improve endothelial function in the peripheral circulation, with effects that extend beyond its ability to lower homocysteine levels [

57]. High-dose folic acid acutely lowers blood pressure and enhances vasodilator-stimulated blood flow in patients with coronary artery disease, likely by increasing nitric oxide bioavailability [

3,

58]. This is achieved through the enzymatic regeneration of tetrahydrobiopterin, an essential cofactor for nitric oxide synthase, thereby supporting nitric oxide production and vascular dilation [

57,

58].

Supplemental folic acid can also prevent endothelial dysfunction and nitrate tolerance induced by continuous nitroglycerin therapy, further underscoring its role in maintaining nitric oxide synthase function and vascular health [

3,

57]. These vascular benefits are observed in both coronary and peripheral arteries, suggesting a broad impact on systemic circulation [

57,

58,

59].

4.2. Folate and Lymphedema

Folate's influence extends to the lymphatic system, where it may promote lymphangiogenesis, the formation of new lymphatic vessels, and improve lymphatic flow. Evidence from a human study supports the role of folate in enhancing lymphatic circulation [

2]. This clinical case reported successful use of folate in managing lymphatic congestion and limb swelling in a patient with primary lymphedema [

2]. This suggests that folate supplementation could be a promising adjunct in the management of lymphedema, potentially by improving lymphatic vessel function and reducing interstitial fluid accumulation [

2,

60,

61]. Such treatment would have fewer secondary effects than the proposed pharmacological use of endothelial growth factors [

62].

4.3. Glymphatic System

The glymphatic system is a recently described waste clearance pathway in the brain, analogous to the peripheral lymphatic system. It facilitates the removal of metabolic waste products and is thought to play a role in neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia [

63,

64,

65]. While direct evidence is limited, it has been speculated that folate could influence glymphatic circulation through mechanisms similar to those observed in peripheral and lymphatic vessels [

2]. If folate enhances nitric oxide production and vascular health, it may also support the function of perivascular spaces and astroglial water channels that drive glymphatic flow [

66].

A diminished glymphatic system has been hypothesized to contribute to the accumulation of neurotoxic waste products in the brain, potentially increasing the risk of dementia [

67,

68]. If folate improves glymphatic clearance, it could offer neuroprotective benefits. While this remains speculative, it warrants further research.

5. Retinal Vascularization and Retinal Disease

Folate deficiency leads to hyperhomocysteinemia, which damages retinal vascular endothelial cells through oxidative stress, inflammation, and barrier breakdown. Proper folate status and transport are essential for homocysteine detoxification, endothelial protection, and maintenance of retinal vascular integrity in eye diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, retinal vascular occlusions, glaucoma, and AMD [

69,

70,

71,

72].

5.1. Retinal Hyperhomocysteine and Vascular Dysfunction

As noted above, folate is a key dietary determinant of plasma homocysteine. Adequate folate enables the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, keeping homocysteine levels low. Folate deficiency is the most common cause of elevated homocysteine (hyperhomocysteinemia) [

69,

70,

72]. Elevated homocysteine exerts direct toxic effects on retinal vascular endothelial cells, contributing to the pathogenesis of retinal vascular diseases such as retinal vascular occlusions, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration. Mechanistically, homocysteine disrupts endothelial cell function by inducing oxidative stress, reducing tight junction protein expression, increasing vascular permeability, and promoting inflammation, which collectively compromise the blood-retinal barrier and retinal vascular integrity [

70,

71,

73].

Experimental models show that high homocysteine leads to a loss of retinal ganglion cells and thinning of retinal layers, effects that can be partially reversed with folate supplementation [

72]. This suggests that folate's protective role extends beyond homocysteine lowering, possibly involving direct support of endothelial cell health and antioxidant capacity.

The efficacy of folate in protecting retinal vasculature depends on its transport into retinal cells, primarily in the form of L-methylfolate. Efficient folate transport is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the inner blood–retinal barrier and resistance to ischemia. Impaired transport or retinal folate deficiency can occur even with normal serum folate, leading to increased local homocysteine and vascular dysfunction [

69,

74]. Folate, particularly L-methylfolate, also supports the production of nitric oxide (NO), a vasodilator that maintains retinal blood flow. Impaired folate availability can lead to vasoconstriction and exacerbate ischemic injury in the retina [

69].

5.2. Retinal Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants

Oxidative stress is a central mechanism by which elevated homocysteine (hyperhomocysteinemia) induces retinal damage. High homocysteine levels increase the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in retinal endothelial and glial cells, overwhelming the eye’s natural antioxidant defenses and leading to cellular dysfunction and tissue injury [

71,

75,

76].

Homocysteine-induced oxidative stress reduces the expression of tight junction proteins in retinal endothelial cells, increasing vascular permeability and contributing to blood-retinal barrier (BRB) breakdown, a hallmark of vision loss in diseases like diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration [

71,

77].

Excess ROS trigger inflammatory pathways and promote apoptosis (cell death) of retinal neurons, including retinal ganglion cells, further compromising retinal structure and function [

75,

77,

78]. Elevated homocysteine not only generates ROS but also diminishes antioxidant capacity, as seen by reduced levels of protective enzymes (e.g., superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase) and total antioxidant capacity in affected patients and experimental models [

76].

The oxidative environment created by high homocysteine contributes to endothelial toxicity, hypercoagulability, and increased risk of retinal vascular occlusions such as central retinal vein occlusion [

76].

Experimental evidence shows that antioxidant treatment can mitigate some of these effects, reducing ROS formation and restoring barrier function in homocysteine-exposed retinal cells [

71]. Thus, oxidative stress is a key mediator of homocysteine-induced retinal damage, driving vascular dysfunction, barrier breakdown, inflammation, and neuronal loss in a range of retinal diseases [

71,

75,

78].

5.3. Clinical Cases

Recent studies have proven the efficacy of using medical food levels of B vitamins, using the methylfolate form of vitamin B, to treat elevated homocysteine levels in individuals with eye diseases. In each case, the treatment used the medical food Ocufolin, which is an AREDS2+ vitamin supply, containing the AREDS2 proven therapy for AMD with B vitamins to support endothelial cell health. In each study the treatment reduced homocysteine levels and improved retinal perfusion, leading to improved outcomes in each retinal disease.

For diabetic retinopathy, the methylfolate reduced homocysteine and improved retinal perfusion, while also reducing stroke risk, leading to the recommendation to evaluate patients for central nervous system microangiopathy using retinal imaging [

79].

In a small case study, glaucomatous conditions were alleviated with similar vitamin treatment. In this study, retinal venous pressure was measured, showing that it was elevated in high tension glaucoma as well as normal tension glaucoma and that the medical food therapy reduced this venous pressure, thus improving retina perfusion and patient outcomes [

7,

39]. This study reveals that normal tension glaucoma patients have elevated retinal venous pressure, and that the vitamin therapy provides a viable treatment for this challenging to treat condition.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) patients were similarly evaluated for retinal venous pressure and found that the Ocufolin vitamin therapy reduced it as well as reducing homocysteine levels. It was further found that use of this oral vitamin treatment was as effective as the anti-VEGF ocular injections that are the standard of care in AMD, with stronger outcomes seen using vitamin therapy, arguing that reducing homocysteine and retinal venous pressure may be the most effective treatment of AMD [

1].

6. Neurodegenerative Disorders: Dementia and Cognitive Decline

Folate deficiency has emerged as a significant modifiable risk factor for neurodegenerative disorders, particularly dementia and cognitive decline. This section evaluates data from epidemiological, clinical, and mechanistic studies to elucidate folate's role in brain health and neurodegeneration.

Current evidence supports folate's role in mitigating neurodegeneration through homocysteine regulation, endothelial cell maintenance, DNA repair, and anti-inflammatory pathways. While population-level fortification has reduced severe deficiency, suboptimal folate status remains a risk factor for cognitive decline. Targeted supplementation may benefit deficient individuals, but universal recommendations require further stratification by age, genetic factors, and baseline nutrient status.

6.1. Neurodegenerative Disease and Folate

Folate deficiency has emerged as a significant modifiable risk factor for neurodegenerative disorders, particularly dementia and cognitive decline. This report synthesizes evidence from epidemiological, clinical, and mechanistic studies to elucidate folate's role in brain health and neurodegeneration. As explained above, folate deficiency elevates homocysteine, a neurotoxic amino acid associated with vascular damage and neuronal apoptosis. Hyperhomocysteinemia disrupts endothelial function and increases oxidative stress, contributing to Alzheimer's pathology and cerebrovascular disease [

80,

81,

82].

Folate is critical for nucleotide synthesis and methylation. Experimental studies in mice lacking uracil glycosylase demonstrate that folate deficiency exacerbates uracil misincorporation into DNA, leading to hippocampal neuron death and reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [

80]. Impaired DNA repair mechanisms may accelerate age-related cognitive decline.

Low folate also correlates with elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) and reduced glutathione, a key antioxidant. These factors synergistically promote neuronal damage and inhibit hippocampal neurogenesis [

80,

83].

6.2. Folate Deficiency Linked to Cognitive Decline

There is extensive clinical evidence of the impact of folate deficiency in cognitive decline. A longitudinal study of 3,140 older Irish adults found folate levels <5 ng/ml predicted accelerated global cognitive decline, while levels <9 ng/ml impaired episodic memory [

84]. Note that serum folate levels between 4-9 ng/ml are considered borderline, while serum levels under 4 are considered low [

28]. In an earlier study (Sacramento Area Latino Study) found that folate was directly associated with cognitive function and inversely associated with dementia [

85].

A Korean study found that low-normal serum folate levels (1.5 – 5.9 ng/ml) increased the risk of cognitive impairment, finding that in their 4 year period the dementia risk was significantly higher for people with those folate levels [

86]. An Israeli study found that serum folate levels in an older population of less than 4.4 ng/ml increased dementia risk by 68%, and increased the all-cause mortality risk by a factor of three [

81]. This compares with the Irish and Latino studies, where data showed that post-fortification there was a persistent association between low-normal folate and cognitive impairment, suggesting optimal thresholds may exceed current deficiency criteria [

84,

85].

Low serum and red cell folate levels are consistently associated with increased risk of cognitive decline, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular dementia in elderly populations. Prospective studies have shown that folate or vitamin B12 deficiency can double the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease [

87].

Data from large cohorts indicate that higher dietary folate intake is associated with reduced odds of cognitive impairment, with a linear relationship observed between total folate intake and lower risk of global cognitive decline [

88].

6.3. Folate Supplementation Slows Cognitive Decline

Folate supplementation has been extensively studied for its potential to improve cognitive function in elderly populations at risk of cognitive decline, particularly those with mild cognitive impairment or low baseline folate status.

In a 12-month clinical trial of 180 patients with mild cognitive impairment in China, they found that folic acid supplementation of 400 μg/day improved global cognition test scores on multiple assessments, significantly raised serum folate and lowered homocysteine, and reduced IL-6/TNF-α by 30% [

83]. 400 μg/day is the recommended folic acid supplement amount in the US [

28].

A high-dose supplementation (5 mg/day) in Japanese elders with cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s Disease found significant improvement in cognition as measure with the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), and observed this was correlated with homocysteine reduction [

89]. A meta-analysis evaluated and observed that nutritional intervention with folate plays an important role in slowing the progression of cognitive decline, but that there is a need to make clear the optimal supplementation levels. Additionally, they observed that homocysteine levels may be a useful biomarker [

90]. In their comparisons of the studies, they found seven studies of folate, four of folate and B12, and ten of B6 and B12. All the studies that included folate found a benefit, reducing cognitive impairment and biomarkers associated with impairment, while the studies without folate found no cognitive improvements [

90].

A 2024 meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials involving over 1,100 older adults (mean age 65–80) with MCI found that folic acid supplementation resulted in significant improvements in several cognitive domains, including Full Scale IQ, arithmetic, information, digit span, and block design scores. The intervention also reduced inflammatory cytokines and homocysteine levels, both of which are implicated in neurodegeneration [

91].

Another comprehensive review of 51 studies (including 23 meta-analyzed) concluded that folate-based B vitamin supplementation has a significant overall positive effect on cognitive function in older adults, particularly in regions without mandatory folic acid food fortification. In countries with fortification policies, additional supplementation did not yield significant cognitive benefits, likely due to already adequate folate status in the population [

92].

In a 6-month trial in China (a country without folic acid fortification), elderly individuals with MCI who received 400 µg/day of folic acid showed significant improvements in cognitive performance (Full Scale IQ, Digit Span, Block Design) compared to controls. These improvements were accompanied by increased serum folate and vitamin B12, and reduced homocysteine levels [

93]

Historical studies and open-label trials have also reported that folic acid supplementation (often at 5 mg/day) improved mood, initiative, alertness, and cognitive function in folate-deficient elderly, with some patients showing marked functional recovery [

87].

6.4. Efficacy of Folate in Slowing Cognitive Decline

The cognitive benefits of folate supplementation are most pronounced in populations with low baseline folate or without mandatory food fortification. In countries with widespread folic acid fortification, further supplementation may not confer additional cognitive benefits for most older adults [

92].

Individuals with MCI or documented folate deficiency are more likely to benefit from supplementation than cognitively healthy or folate-replete individuals [

91,

93]. Excessive folate supplementation in certain high-risk groups (e.g., those with cardiovascular disease) may have adverse effects, and supplementation should be used cautiously in the presence of vitamin B12 deficiency or epilepsy [

87,

88].

Folate supplementation can improve cognitive function in at-risk elderly populations, especially those with mild cognitive impairment or low baseline folate status, and in regions without mandatory folic acid fortification. The greatest benefits are observed in individuals with documented deficiency or elevated homocysteine. Supplementation is less likely to be effective in populations with adequate folate levels due to food fortification. Additionally, folate absorption and utilization entails adequate vitamin B12 levels, so a B12 deficiency can impact efficacy or impact other disease [

94]. Further high-quality trials are needed to define optimal dosing and identify subgroups most likely to benefit [

91,

92,

93]. In this regard, there is potential from machine learning systems to glean evidence from large databases such as the UK Biobank, to identify nutrients that increase and those that decrease dementia risk [

95].

6.5. Risks of Excessive Folate in Disease

Folate is essential for cardiovascular and neurological health, largely due to its role in homocysteine metabolism and DNA repair. While adequate folate intake is beneficial, excessive folate supplementation in older adults with CVD may pose certain risks.

The relationship between folate intake and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in older adults is complex, with emerging evidence suggesting potential risks associated with excessive folate consumption in this population. Excessive folate intake risks for older adults with CVD include masking B12 deficiency, potential increases in mortality risk, and attenuation of cognitive benefits. For these reasons, supplementation needs to be tailored, and high-dose folic acid avoided. These risks may be unique to folic acid, suggesting routine use of methylfolate may mitigate risk while conferring the cognitive benefit. These findings highlight the need for personalized folate recommendations in older adults with CVD, contrasting with general population guidelines [

88,

96].

Table 3 summarizes the high-dose folic acid risks.

6.5.1. Excess Folic Acid and Increased Mortality Risk

Excess folic acid is linked to an increased CVD mortality in multiple studies. While modest folate intake showed improvement in long-term survival, excess folic acid in CVD patients increased mortality [

51,

97]. High red blood cell folate levels (>1,080 nmol/L) are linked to a 32% higher risk of CVD mortality and 25% increased all-cause mortality in older adults with preexisting CVD [

88,

96].

These finding of benefit of moderate folate and danger from high levels reveal a U-shaped relationship for folate. Low (<476 nmol/L) and high red blood cell folate levels correlate with elevated CVD mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes [

88].

These data show that moderate dietary folate (400–600 μg/day) reduced mortality risk, while high supplemental folate (>1,000 μg/day) increased mortality risk by 18–24% [

50,

88].

6.5.2. Excess Folic Acid and Attenuated Cognitive Benefits

As detailed above, folate supplementation can improve cognition in deficient individuals. However, excessive intake may not confer additional benefit and could even attenuate protective effects, especially in those with CVD or diabetes.

While red blood cell folate normally protects against cognitive impairment this protective effect disappears entirely in CVD patients [

88]. CVD may exacerbate insulin resistance and cerebral microcirculation damage, counteracting folate's neuroprotective benefits [

88].

6.5.3. Pathways of Harm from Excess Folic Acid

There are a number of proposed mechanisms of why excess folic acid can be problematic, especially with CVD patients.

Folate oversaturation in fortified populations: Over 50% of U.S. CVD patients already meet recommended folate intake, yet 25% still use supplements [

88].

Interaction with CVD pathophysiology: High folate may accelerate atherosclerosis progression in established CVD through poorly understood mechanisms [

96]

Homocysteine paradox: While folate lowers homocysteine, excessive supplementation in CVD patients shows no mortality benefit despite homocysteine reduction [

98].

Masking Vitamin B12 Deficiency: High folate intake can mask hematological signs of vitamin B12 deficiency, which is common in older adults. This can allow neurological damage from B12 deficiency to progress undetected, potentially leading to irreversible cognitive and neurological impairment [

55].

Potential for Unmetabolized Folic Acid: High intake of synthetic folic acid (from supplements/fortified foods) can lead to unmetabolized folic acid in the bloodstream, which has been linked to impaired immune function and possibly increased cancer risk [

54,

99]. This risk from unmetabolized folic acid, when found during pregnancy and lactation, may also be associated with an increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism [

100,

101].

6.5.4. Guidelines for Folate Supplementation in CVD Patients

The data support avoiding use of high-dose folic acid supplements in older adults with CVD history. High-dose folic acid supplements are over 400 μg/day. The published at-risk threshold is for red blood cell folate levels over 900 nmol/L in CVD patients, which warrants caution [

88].

The recommendations to avoid this are to prioritize dietary folate (leafy greens, legumes) over synthetic folic acid [

88,

96]. Additionally, monitoring of red blood cell folate levels in CVD patients taking B-complex vitamins is essential [

88].

Given that it is the use of folic acid, which is the oxidized version of folate, that is problematic, if dietary folate (which is a reduced folate) is insufficient to meet the folate need, use of other reduced forms of folate, namely methylfolate or folinic acid, would be advised. In this regard, high-dose folinic acid (prescription name, leucovorin) has been used for over 75 years as a prescription vitamin B9 replacement (in chemotherapy). No cardiotoxicity has been observed with this high dose leucovorin, with the exception that leucovorin in combination with 5-fluorouracil had the same cardiotoxicity (3%) as 5-fluorouracil alone [

102].

The guidelines for folate supplementation in CVD patients summarize as:

Avoid high-dose folic acid supplements (>400 μg/day) in older adults with CVD unless prescribed for a specific deficiency.

Monitor vitamin B12 status in older adults taking folic acid, especially those at risk for deficiency.

Prioritize dietary sources of folate (leafy greens, legumes) over high-dose supplements, unless medically indicated.

When supplementation is warranted, prioritize use of methylfolate and folinic acid (leucovorin).

Personalize supplementation based on individual risk factors, comorbidities, and baseline folate/B12 status.

7. Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder is a multifactorial disorder with origins in the fetal period [

103]. Folate is essential for early brain development, and maternal deficiency is associated with increased risk of ASD in offspring. Recent research has explored the relationship between maternal folate status and the risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), as well as the therapeutic potential of folate supplementation in children with ASD. High-dose folinic acid supplementation has shown promise in improving core symptoms of ASD, particularly in children with mitochondrial dysfunction or folate receptor autoantibodies. The role of folate in methylation and epigenetic regulation provides a plausible biological mechanism for these effects. Future research focusing on personalized interventions based on genetic and metabolic profiles should benefit treatment options.

7.1. Folate Role in Brain Formation During Pregnancy

Folate is vital for the closure of the neural tube during embryogenesis, which occurs within the first month of pregnancy. Inadequate maternal folate intake is a well-known risk factor for neural tube defects such as spina bifida and anencephaly. Beyond neural tube defects, folate is crucial for early brain development, influencing neuronal proliferation, migration, and synaptogenesis [

104,

105].

Rodent models have demonstrated that maternal folate deficiency leads to impaired neurogenesis, abnormal brain structure, and behavioral changes reminiscent of ASD, such as reduced social interaction and increased repetitive behaviors [

106].

Epidemiological studies have linked low maternal folate levels or lack of periconceptional folic acid supplementation to increased ASD risk in offspring. A large Norwegian cohort study found that maternal use of folic acid supplements around conception was associated with a lower risk of autistic disorder in children [

107]. Similarly, a meta-analysis concluded that maternal folic acid supplementation significantly reduced the risk of ASD [

108].

Folate is a key donor of methyl groups for DNA methylation, an epigenetic mechanism that regulates gene expression. Disruptions in methylation pathways have been implicated in ASD. Children with ASD often exhibit abnormal DNA methylation patterns and altered expression of genes involved in synaptic function and neurodevelopment [

109]. Low folate increases homocysteine levels, which is neurotoxic and can impair neuronal migration, synapse formation, and myelination. Elevated homocysteine during gestation has been associated with increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring.

Folate supplementation may help correct these epigenetic disruptions. For instance, animal studies show that maternal folate supplementation can reverse methylation abnormalities and behavioral deficits in offspring exposed to environmental risk factors for ASD [

106].

Maternal folate deficiency during early brain development increases autism risk through multiple mechanisms: impaired DNA synthesis and repair, epigenetic dysregulation, and elevated neurotoxic homocysteine. Both animal and human studies support the protective effect of adequate maternal folate against ASD. Ensuring sufficient maternal folate intake before and during early pregnancy is a key public health strategy to reduce the risk of autism and optimize neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Recent clinical trials have investigated the effects of high-dose folinic acid (a bioactive form of folate) in children with ASD, particularly those with mitochondrial dysfunction or folate receptor autoantibodies [

110]. Multiple trials in which ASD children received high-dose folinic acid (2 mg/kg/day, up to 50 mg/day) for 12 weeks have been conducted. In each, the treatment group showed significant improvements in verbal communication, especially in children with folate receptor autoantibodies [

32,

111,

112].

7.2. Maternal Folate Deficiency and Autism Risk

Decreased access to folate during gestation can be due to low maternal folate levels, genetic variants, or autoimmune disorders [

44,

113].

Table 4 summarizes the impact of maternal folate deficiency and its link to autism. Insufficient folate conveys multiple risks for neurodevelopmental disorders.

7.2.1. Impaired DNA Synthesis and Neuronal Repair

Folate is essential for DNA synthesis and repair, especially during periods of rapid cell division in early embryonic brain development. Deficiency leads to DNA instability and impaired neuronal repair, potentially causing abnormal brain structure and function, key features implicated in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [

114].

7.2.2. Homocysteine Accumulation and Neurotoxicity

Folate regulates homocysteine metabolism. Without adequate folate, homocysteine levels rise. Elevated homocysteine is neurotoxic. It can disrupt neuronal migration, synapse formation, and myelination, all critical for normal brain development. High maternal homocysteine is associated with increased ASD risk in offspring [

115].

7.2.3. Disrupted Methylation and Epigenetic Regulation

Folate provides methyl groups for DNA methylation, a key epigenetic process that controls gene expression during neurodevelopment. Deficiency results in hypomethylation, leading to abnormal activation or silencing of genes crucial for brain development, synaptic function, and neuronal connectivity. Epigenetic dysregulation is a recognized mechanism in ASD etiology [

114].

7.2.4. Altered Neurotransmitter Synthesis

Folate is involved in the synthesis of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Deficiency may lead to imbalances in these neurotransmitters, which are often observed in individuals with ASD [

116].

7.2.5. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

Low folate levels increase oxidative stress and susceptibility to neuroinflammation. Both oxidative stress and chronic inflammation are implicated in the pathogenesis of ASD [

117,

118].

7.3. Critical Periods for Folate and Autism

Research consistently identifies early pregnancy, particularly the periconceptional period (just before and shortly after conception) and the first trimester, as the most critical window for folate intake to reduce autism risk in offspring. Multiple large cohort and case-control studies demonstrate that folic acid supplementation starting before conception and continuing through early pregnancy is associated with a significantly lower risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children [

107,

119,

120,

121].

The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study found a 40–45% reduction in autistic disorder risk among women who took folic acid supplements from four weeks before to eight weeks after conception [

119]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of published studies where folic acid was supplemented during pregnancy (but not prior) found a significant reduction in risk of ASD [

108].

When folinic acid was supplemented (at 7.5 mg/day) periconceptionally and throughout gestation in two women expressing folate receptor autoantibodies, and with prior ASD births, the children were neurotypical at three years of age [

122]. This indicates a more universal folate supplement for periconception and gestation may be folinic acid rather than folic acid.

The first month of pregnancy, when the neural tube forms and closes, is especially sensitive to folate status [

115]. Supplementation during this period appears to be crucial for both preventing neural tube defects and reducing ASD risk.

Continuous folic acid supplementation from the periconceptional through the prenatal period may offer the greatest protective effect to reduce ASD risk [

119,

120,

122]. Women who missed supplementation during both periods had the highest risk of having a child with ASD [

119,

120].

Some evidence suggests a U-shaped relationship: both low and excessively high maternal folate levels may increase ASD risk, while moderate, recommended intake is optimal [

119]. This may be unique to folic acid supplementation, as a study with 7.5 mg/day of folinic acid did not exhibit any high folate risk [

122].

7.3.1. Insights from Folate Supplementation in Reducing Risk of Autism

An important critical period for folate intake to prevent autism is from at least one month prior to conception through the first trimester of pregnancy. Supplementation during this window is strongly associated with a reduced risk of ASD in offspring [

107,

119,

120,

121].

Overall observations are:

Begin Supplementation Before Conception: Start at least one month before trying to conceive and continue through the first trimester of pregnancy [

107,

119,

120,

121].

Maintain Adequate Intake: 400 micrograms (mcg) of folic acid daily is the widely recommended dose for women planning pregnancy and during early gestation [

115,

120].

Continue Through Early Pregnancy: Ensure consistent intake through the first 2–3 months of pregnancy, the period of neural tube and early brain development [

115,

120].

Maternal folate is crucial for neurodevelopment during critical pregnancy windows due to its central role in several fundamental biological processes required for healthy brain formation and function in the fetus.

7.3.2. DNA Synthesis and Cellular Proliferation

Folate is essential for DNA synthesis and repair, supporting the rapid cell division and growth that occur during early embryonic development. This is especially important for neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation, which lay the foundation for the brain’s structure and complexity [

105,

123,

124]. The roles of folate in early development include:

Neural Tube Closure. During the first month of pregnancy, folate is critical for the closure of the neural tube—a process that, if disrupted, results in severe neural tube defects such as spina bifida and anencephaly. This is why periconceptional folic acid supplementation is universally recommended to women planning pregnancy [

105,

123,

124,

125].

Epigenetic Regulation and Gene Expression. Folate acts as a methyl donor in one-carbon metabolism, which is required for DNA methylation. Proper methylation regulates gene expression patterns necessary for normal brain development. Disrupted methylation due to folate deficiency can lead to long-lasting neurodevelopmental and cognitive changes in offspring [

105,

123,

124].

Neurotransmitter and Phospholipid Synthesis. Folate is involved in the synthesis of key neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine) and phospholipids, both of which are vital for neuronal signaling, connectivity, and myelination [

105,

123,

124].

Prevention of Cell Death (Apoptosis). Adequate maternal folate reduces apoptosis (programmed cell death) in developing brain regions, ensuring proper formation of neural circuits [

124].

Maintenance of Healthy Homocysteine Levels. Folate helps maintain low homocysteine concentrations. Elevated homocysteine is neurotoxic and has been linked to impaired neurodevelopment [

105,

123].

Human studies, while sometimes inconsistent due to methodological differences, generally support that adequate maternal folate, especially during the periconceptional period and first trimester, is associated with better neurodevelopmental and cognitive outcomes in children [

105,

123,

124,

126]. This is summarized in

Table 5.

Maternal folate is vital during critical pregnancy windows because it underpins DNA synthesis, gene regulation, neurotransmitter production, and neural tube closure, all of which are foundational for healthy fetal brain development [

105,

123].

7.3.3. Insights from Folate Supplementation in Reducing Risk of Autism

Periconceptional and first trimester folate intake are most strongly associated with reduced ASD risk and better neurodevelopmental outcomes [

107,

119,

120,

121,

122]

Very high maternal folate/B12 levels late in pregnancy may be associated with increased ASD risk, suggesting moderation is important [

119]

Genetic factors (e.g., MTHFR polymorphisms) can modify the protective effect of folate [

119,

121]

Plasma/whole blood folate levels alone are less predictive than supplement use, possibly due to timing and individual metabolism [

119]

Use of folinic acid during periconceptional period and throughout gestation may mitigate the risk associated with gene variants and maternal FRAA [

122]

7.4. Folinic Acid Clinical Trials

Folinic acid (leucovorin) is a bioactive form of folate that bypasses certain metabolic blocks, including those caused by folate receptor autoantibodies or mitochondrial dysfunction, both of which are more prevalent in many children presenting with autism spectrum disorder. Folate receptor autoantibodies present in approximately 70% of ASD children [

32]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is estimated to occur in up to 5% of children with ASD, and it can impair folate transport into the brain, potentially worsening neurodevelopmental symptoms [

110].

Clinical trials using folinic acid have been completed in multiple countries, with similar findings in all [

32,

111,

112,

127,

128]. All trials were double-blind, placebo controlled, with children under 15. The intervention used was folinic acid at 2mg/kg/day (up to 50 mg/day for 12 weeks. All found significant improvement in verbal communication in a majority (but not all) of children presenting with folate receptor autoantibodies, and little to no effect in children testing negative for the antibody. The folinic acid was well-tolerated, with mild side effects of irritability and insomnia being rare and manageable.

The findings indicate that folinic acid can lead to clinically meaningful improvements in core ASD symptoms, especially language and communication, in children with mitochondrial dysfunction or cerebral folate deficiency [

32,

111,

112,

127,

128].

Benefits are most pronounced in subgroups with biomarkers indicating impaired folate transport or metabolism, as measured by presence of the folate receptor autoantibody.

Folinic acid is effective due to three features:

Bypasses Blocked Folate Transport. Folinic acid can cross the blood-brain barrier via alternative transporters, even when folate receptor alpha is blocked by autoantibodies.

Supports Mitochondrial Function. Folinic acid may enhance mitochondrial energy production, reduce oxidative stress, and improve neuronal metabolism.

Restores Methylation. As a methyl donor, it supports DNA methylation and neurotransmitter synthesis, processes often disrupted in ASD.

The limitations to folinic acid treatment are that not all children respond. The most significant benefits are seen in children with folate receptor autoantibodies and/or with mitochondrial dysfunction. Because most studies are short-term (12–24 weeks), long-term efficacy and safety requires further research.

High-dose folinic acid is an effective and generally well-tolerated intervention for improving core symptoms, particularly language and communication, in ASD children who have mitochondrial dysfunction or folate receptor autoantibodies. The strongest evidence comes from randomized controlled trials and open-label studies. Benefits are most pronounced in biomarker-positive subgroups. Further research is needed to optimize dosing, duration, and identify all responsive phenotypes [

32,

111,

112,

127,

128].

8. Conclusions

Current evidence demonstrates that deficiencies in key vitamins—including folate (B9), vitamins B6 and B12, C, D, and E—play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and subsequent development of a range of vascular and degenerative disorders. Restoration of vitamin status, especially with bioactive forms and targeted supplementation, improves endothelial function and microvascular health, underscoring the therapeutic potential of correcting deficiencies.

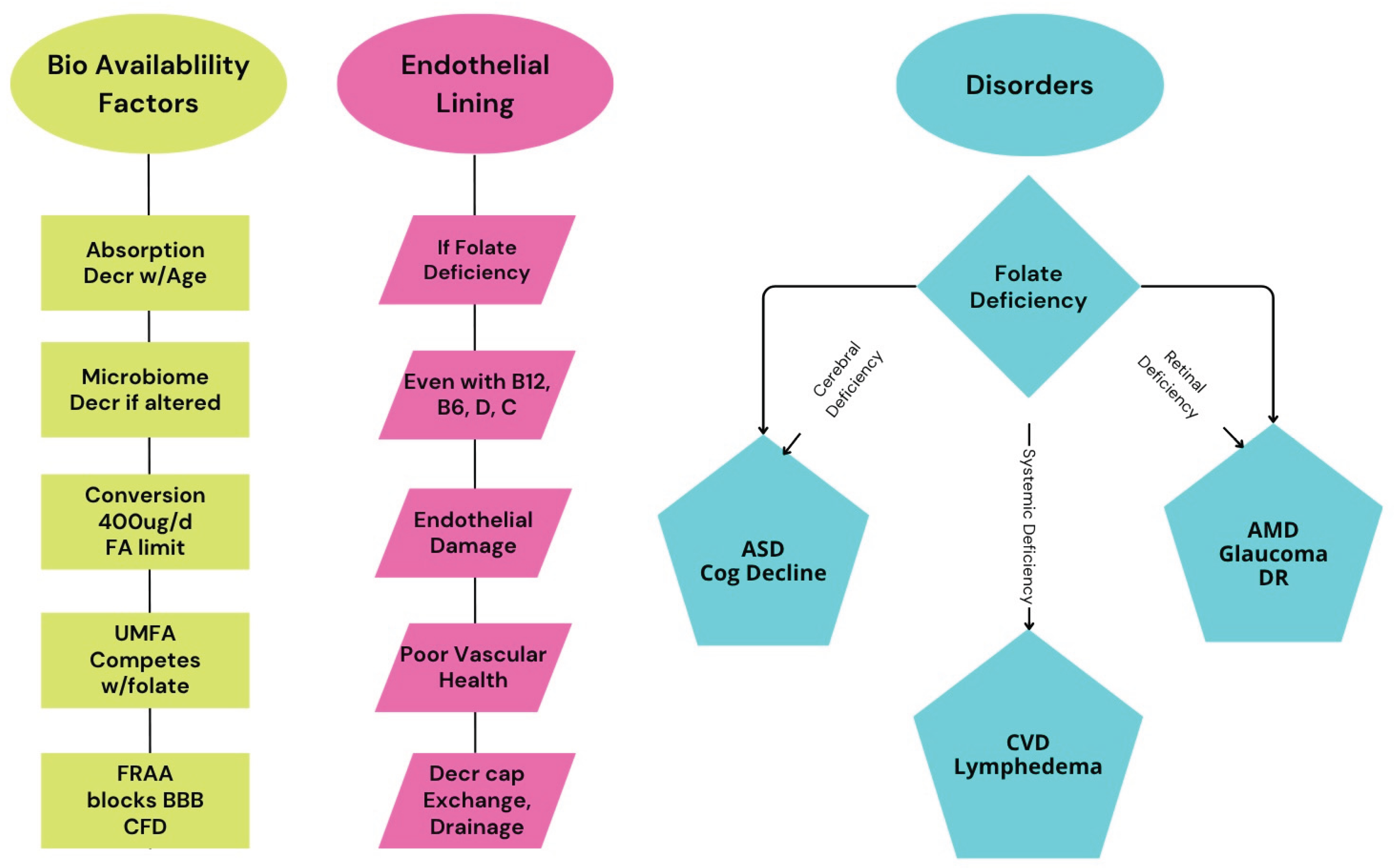

Clinically, poor vascular health resulting from impaired vitamin metabolism or absorption can manifest as cerebrovascular disease, lymphedema, cognitive decline, age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic microvascular complications. The mechanisms driving these associations involve hyperhomocysteinemia, increased oxidative stress, impaired nitric oxide signaling, defective collagen synthesis, and heightened inflammation—all modifiable via nutritional intervention and supplementation, as summarized in

Figure 2.

Despite strong observational and mechanistic studies supporting the link between vitamin deficiency and vascular risk, interventional trials have produced mixed results, particularly for cardiovascular disease events. Nevertheless, normalization of vitamin levels—particularly vitamin D and homocysteine-lowering B vitamins—can improve vascular function metrics and reduce risk factors. These findings suggest that clinical strategies prioritizing adequate vitamin intake, tailored supplementation, and use of bioavailable forms may enhance patient outcomes and help prevent progression of disorders rooted in poor vascular health. Additionally, neurodegenerative disorders such as autism are impacted by cerebral folate deficiency, and show benefit from treatment with natural folate in the form of leucovorin.

Optimizing vascular health requires a multifaceted approach: correcting vitamin deficiencies, understanding their molecular effects on endothelial and smooth muscle cells, and integrating nutritional therapy with standard clinical care. Further trials are warranted to define optimal intervention protocols and outcomes for vitamin-based therapies in the prevention and management of degenerative vascular diseases.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5-MTHF |

5-methyl tetrahydrofolate |

| MTHFR |

MTHF reductase |

| DHFR |

Dihydrofolate reductase |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| FMD |

Flow mediated diffusion |

| CAD |

Coronary Artery Disease |

| VEGF |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| AMD |

Age-related Macular Degeneration |

| ASD |

Autism Spectrum Disorder |

References

- Josifova, T.; Konieczka, K.; Schötzau, A.; Flammer, J. The Effect of a Specific Vitamin Supplement Containing L-Methylfolate (Ocufolin Forte) in Patients with Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, George Treatment of Primary Lymphedema Following Lessons from Endothelin-Driven Retinal Edema, a Case Report. Heal. TIMES Schweiz. Ärztejournal J. Médecins Suisses 2024, 14, 10–13.

- Stanhewicz, A.E.; Kenney, W.L. Role of Folic Acid in Nitric Oxide Bioavailability and Vascular Endothelial Function. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baddam, S.; Khan, K.M.; Jialal, I. Folic Acid Deficiency. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, L.B.; Stover, P.J.; McNulty, H.; Fenech, M.F.; Gregory, J.F.; Mills, J.L.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Fazili, Z.; Zhang, M.; Ueland, P.M.; et al. Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development—Folate Review1, 2, 3, 4, 5. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1636S–1680S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, S.N.; McDowell, I.F.W.; Moat, S.J.; Lang, D.; Newcombe, R.G.; Kredan, M.B.; Lewis, M.J.; Goodfellow, J. Folate Improves Endothelial Function in Coronary Artery Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001, 21, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, G.; Luo, Y. Ischemia from Retinal Vascular Hypertension in Normal Tension Glaucoma: Neuroprotective Role of Folate. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2023, 20, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghubeer, S.; Matsha, T.E. Methylenetetrahydrofolate (MTHFR), the One-Carbon Cycle, and Cardiovascular Risks. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J.M. Folate and Folic Acid Metabolism: A Significant Nutrient-Gene-Environment Interaction. Med. Res. Arch. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cantley, L.C. Toward a Better Understanding of Folate Metabolism in Health and Disease. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, R. The Metabolic Burden of Methyl Donor Deficiency with Focus on the Betaine Homocysteine Methyltransferase Pathway. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3481–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Rezaiian, F.; Saadati, S.; Naseri, K.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Yousefi, M.; Golalipour, E.; Clark, C.C.T.; Rastgoo, S.; Asbaghi, O. The Effects of Folic Acid Supplementation on Endothelial Function in Adults: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakeeny, L.; Roubenoff, R.; Obin, M.; Fontes, J.D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bujanover, Y.; Jacques, P.F.; Selhub, J. Plasma Pyridoxal-5-Phosphate Is Inversely Associated with Systemic Markers of Inflammation in a Population of U.S. Adults. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.; Miller, J.W. Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Vitam. Horm. 2022, 119, 405–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, T.; Syeed, R.; Glascow, N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Zis, P. B12 as a Treatment for Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, H.; Pentieva, K.; Hoey, L.; Ward, M. Homocysteine, B-Vitamins and CVD. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2008, 67, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, null; Kumari, A.; Singh, S.; Ahmad, M.F.; Chaki, D.; Poria, V.; Kumar, S.; Saini, N.; Yadav, N.; Sangwan, N.; et al. Vitamin D: Recent Advances, Associated Factors, and Its Role in Combating Non-Communicable Diseases. NPJ Sci. Food 2025, 9, 100. [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, F.; Ali, S.H.; Naeem, A.; Savul, S.; Afridi, M.S.I.; Kamran, N.; Fazal, F.; Khawer, S.; Savul, I.S.; Najeeb, H.; et al. Current Evidence and Future Perspectives of the Best Supplements for Cardioprotection: Have We Reached the Final Chapter for Vitamins? Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.B.; Boucher, B.J.; Cheng, R.Z.; Pludowski, P.; Wimalawansa, S.J. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Health: A Narrative Review of Risk Reduction Evidence. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Peng, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Shi, F.; Wang, Y.; Hua, L. The Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Endothelial Function: An Umbrella Review of Interventional Meta-Analyses. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 103871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Preventive Services Task Force Vitamin, Mineral, and Multivitamin Supplementation to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2022, 327, 2326–2333. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mheid, I.; Patel, R.; Murrow, J.; Morris, A.; Rahman, A.; Fike, L.; Kavtaradze, N.; Uphoff, I.; Hooper, C.; Tangpricha, V.; et al. Vitamin D Status Is Associated With Arterial Stiffness and Vascular Dysfunction in Healthy Humans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri, E.; Kassis, N.; Iskandar, J.-P.; Schurgers, L.J.; Saad, A.; Abdelfattah, O.; Bansal, A.; Isogai, T.; Harb, S.C.; Kapadia, S. Vitamin K2—a Neglected Player in Cardiovascular Health: A Narrative Review. Open Heart 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, T.; Chae, S.Y.; Lee, J.; Han, J.W.; Yang, H.; Chung, B.S.; Yang, K. Multivitamin Supplementation and Its Impact in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folate (Folic Acid) - Vitamin B9 • The Nutrition Source 2012.

- Staff, I. for N.M. Fact Sheet: Folate (Vitamin B9) & Folic Acid. Inst. Nat. Med. 2024.

- Caudill, M.A. Folate Bioavailability: Implications for Establishing Dietary Recommendations and Optimizing Status1234. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1455S–1460S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Dietary Supplements - Folate. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Folate-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, B.; Qiao, L.; Zhao, J.; Pourkheirandish, M.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X. Folate (Vitamin B9) Content Analysis in Bread Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrell, B.J.; McMurry, J.P. Folic Acid. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, C.; Shuman, A.; Nice, S.; Salehi, P. The Critical Role of Folate in Prenatal Health and a Proposed Shift from Folic Acid to 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate Supplementation. Georget. Med. Rev. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E.; Slattery, J.; Delhey, L.; Furgerson, B.; Strickland, T.; Tippett, M.; Sailey, A.; Wynne, R.; Rose, S.; Melnyk, S.; et al. Folinic Acid Improves Verbal Communication in Children with Autism and Language Impairment: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørke-Monsen, A.-L.; Ueland, P.M. Folate – a Scoping Review for Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67, 10.29219/fnr.v67.10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, A.J.; Heid, M.K.; Peerson, J.M.; Bills, N.D. Bioavailability of Food Folates and Evaluation of Food Matrix Effects with a Rat Bioassay. J. Nutr. 1991, 121, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, J.A.; Groom, A.; Potter, C.; Coneyworth, L.J.; Ford, D.; Mathers, J.C.; Relton, C.L. Genetic and Non-Genetic Influences during Pregnancy on Infant Global and Site Specific DNA Methylation: Role for Folate Gene Variants and Vitamin B12. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e33290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppedè, F. The Genetics of Folate Metabolism and Maternal Risk of Birth of a Child with Down Syndrome and Associated Congenital Heart Defects. Front. Genet. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, I.J.M. van der; Afman, L.A.; Heil, S.G.; Blom, H.J. Genetic Variation in Genes of Folate Metabolism and Neural-Tube Defect Risk. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2006, 65, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, K.; Findley, T.; Northrup, H. Finding the Genetic Mechanisms of Folate Deficiency and Neural Tube Defects – Leaving No Stone Unturned. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2017, 173, 3042–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devogelaere, Thibaut; Schôtzau The Effects of Vitamin Supplementation Containing L-Methylfolate (Ocufolin® Forte) on Retinal Venous Pressure and Homocysteine Plasma Levels in Patients with Glaucoma. Heakthbook TIMES 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Piao, S.; Kim, S.; Nagar, H.; Choi, S.-J.; Jeon, B.H.; Oh, S.-H.; Irani, K.; Kim, C.-S. CRIF1 Deficiency Increased Homocysteine Production by Disrupting Dihydrofolate Reductase Expression in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Antioxid. Basel Switz. 2021, 10, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, J.; Yu, C.; Deng, Y.; Wen, Q.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Luo, R. Case Report: Cerebral Folate Deficiency Caused by FOLR1 Variant. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1434209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skavinska, O.; Rossokha, Z.; Fishchuk, L.; Gorovenko, N. RFC and VDR -Mediated Genetic Regulation of Brain Folate Transport in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Hum. Gene 2025, 44, 201399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanyshyn, V.; Stetsyuk, R.; Hrebeniuk, O.; Ayoub, G.; Fishchuk, L.; Rossokha, Z.; Gorovenko, N. Analysis of the Association Between the SLC19A1 Genetic Variant (Rs1051266) and Autism Spectrum Disorders, Cerebral Folate Deficiency, and Clinical and Laboratory Parameters. J. Mol. Neurosci. MN 2025, 75, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, G. Autism Spectrum Disorder as a Multifactorial Disorder: The Interplay of Genetic Factors and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, I.F.W.; Lang, D. Homocysteine and Endothelial Dysfunction: A Link with Cardiovascular Disease12. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 369S–372S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moat, S.J.; Lang, D.; McDowell, I.F.W.; Clarke, Z.L.; Madhavan, A.K.; Lewis, M.J.; Goodfellow, J. Folate, Homocysteine, Endothelial Function and Cardiovascular Disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2004, 15, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaar, M.C.; Stroes, E.; Rabelink, T.J. Folates and Cardiovascular Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRae, M.P. High-Dose Folic Acid Supplementation Effects on Endothelial Function and Blood Pressure in Hypertensive Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. J. Chiropr. Med. 2009, 8, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadharaj, S.; Kelly, O.J.; Khayat, R.N.; Kumar, P.S.; Ahmed, N.; Zweier, J.L. Role of Dietary Antioxidants in the Preservation of Vascular Function and the Modulation of Health and Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Muka, T.; Troup, J.; Hu, F.B. Folic Acid Supplementation and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. Cardiovasc. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016, 5, e003768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wei, W.; Jiang, W.; Song, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, X. Association of Folate Intake with Cardiovascular-Disease Mortality and All-Cause Mortality among People at High Risk of Cardiovascular-Disease. Clin. Nutr. Edinb. Scotl. 2022, 41, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, Y.; Ae, R.; Kuwabara, M. Folate and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertens. Res. 2023, 46, 1816–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loria, C.M.; Ingram, D.D.; Feldman, J.J.; Wright, J.D.; Madans, J.H. Serum Folate and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Among US Men and Women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 3258–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardous, A.M.; Heydari, A.R. Uncovering the Hidden Dangers and Molecular Mechanisms of Excess Folate: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folate - Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline - NCBI Bookshelf. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114318/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Universidade Estadual de Londrina Randomized Clinical Trial of Folate Therapy/Placebo for Reduction of Homocysteine Serum Levels in Uremic Patients and Influence on Cardiovascular Mortality; clinicaltrials.gov, 2018.

- Tawakol, A.; Migrino, R.Q.; Aziz, K.S.; Waitkowska, J.; Holmvang, G.; Alpert, N.M.; Muller, J.E.; Fischman, A.J.; Gewirtz, H. High-Dose Folic Acid Acutely Improves Coronary Vasodilator Function in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. JACC 2005, 45, 1580–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori, T.; Burstein, J.M.; Ahmed, S.; Miner, S.E.S.; Al-Hesayen, A.; Kelly, S.; Parker, J.D. Folic Acid Prevents Nitroglycerin-Induced Nitric Oxide Synthase Dysfunction and Nitrate Tolerance. Circulation 2001, 104, 1119–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, K.S.; Chook, P.; Lolin, Y.I.; Sanderson, J.E.; Metreweli, C.; Celermajer, D.S. Folic Acid Improves Arterial Endothelial Function in Adults with Hyperhomocystinemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999, 34, 2002–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.; Tang, W.H.W. Targeting the Lymphatic System for Interstitial Decongestion. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2021, 6, 882–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Campbell, A.C.; Kuonqui, K.; Sarker, A.; Park, H.J.; Shin, J.; Kataru, R.P.; Coriddi, M.; Dayan, J.H.; Mehrara, B.J. The Future of Lymphedema: Potential Therapeutic Targets for Treatment. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]