1. Introduction

Biomedical engineering is a discipline that applies engineering principles and concepts from biology and medicine to develop solutions that improve human health, whether for diagnostic or treatment purposes (Maldonado, 2025). This branch of engineering surrounds a wide range of technological innovations, including tissue engineering, which is important in developing artificial organs. Tissue engineering promises solutions to challenges such as regenerative medicine and human well-being. Its long-term goal is the advancement of fully functional bioartificial organs (Rondón et al.; 2025).

A bioartificial organ is a device implanted in a human being to restore the function of a damaged organ. These devices are matrices generated using human cells or, in some cases, from mammals. The liver is the largest internal organ and the second largest in the human body. It is also considered in many respects the most complex (Lindenmeyer, 2022). This organ plays a crucial role in the body's metabolic activity, aiding in detoxification, protein synthesis, and nutrient storage. It has been identified that the liver performs more than 500 essential functions for the organism (American Liver Foundation, 2023).

The liver can regenerate—indeed, it possesses the most excellent regenerative capacity of any human organ. Nevertheless, if a disorder or substance damages the liver, it can lead to liver diseases (Tholey, 2023). Some of the most serious of these include cirrhosis, acute liver failure, and liver cancer. It is estimated that around 325 million people worldwide suffer from Hepatitis B or C (WHO, 2025). Certain metabolic diseases may lead to the need for a liver transplant. Due to this organ's high demand and limited availability, an extracorporeal circulation device known as a bioartificial liver (BAL) has been developed. Sometimes, it allows the organ to regenerate while providing temporary support for patients with acute liver failure until a suitable donor is found (AESTA, 2015).

The bioartificial liver does not want to replace the organ but rather to prolong the patient’s life. Therefore, this engineer-developed bioartificial organ aims to offer a potential solution to the shortage of donors and reduce deaths caused by liver diseases. Despite the progress made, significant challenges remain. The primary objective of this study is to analyze the function, applications, challenges, limitations, and future perspectives of the bioartificial liver as an emerging therapeutic option for severe liver diseases.

2. Methodology

This research was developed based on a bibliographic review of scientific studies, including research articles, textbooks, and other reliable sources. The objective was to gather information on biomedical engineering, the principles of bioartificial organs, the development of the bioartificial liver, and its applications.

Information Search and Collection: Databases such as Google Scholar, Web of Science, SciELO, PubMed, Wiley, MedLine, AESTA, and McGraw-Hill were consulted to ensure a comprehensive range of scientific sources. Keywords used included: “biomedical engineering,” “bioartificial organs,” “bioartificial liver,” and “extracorporeal liver devices.”

Selection and Organization of Information: A search and collection period from 1996 to 2025 was established to select publications in English and Spanish that provided relevant data on developing, applying, and evaluating bioartificial liver devices. The collected data was then organized based on its impact on this study.

Selection of Subtopics: The organized information was classified to facilitate structuring the research into subtopics related to the study.

Analysis of Results: A detailed qualitative and systematic analysis of the collected information was conducted, resulting in a comprehensive study conclusion (Rondón et al.; 2025).

3. Discussion and Results

3.1. Natural Liver

The liver is an organ located in the upper right part of the abdomen. Anatomically, it is divided into the left and right lobes (Forbes et al.; 2021). Each of these lobes comprises millions of liver cells, known as hepatocytes. These cells are responsible for most metabolic and detoxification functions, making up approximately 80% of the liver's mass. Hepatocytes are also known as parenchymal cells, as they form the liver's parenchyma (functional tissue). This tissue is essential for performing specific organ functions such as metabolism, detoxification, and protein synthesis (Megías et al.; 2025).

Hepatocytes typically appear in cords, also known as hepatic lobules. These cords can be about 2 to 3 hepatocytes thick. In some cases, they may be thicker, suggesting regenerative activity. These cords are separated by sinusoids—channels that create space through which blood flows from the portal tracts. The portal tracts originate from where the liver's nerves and blood vessels converge, known as the hilum, and extend throughout the organ. These ducts have a branching structure whose connective tissue is primarily composed of collagen, which stains blue due to trichrome staining (Krishna, 2014).

The sinusoids are lined with endothelial and Kupffer cells (Krishna, 2014). Kupffer cells play vital roles in the immune system and are the liver’s primary producers of cytokines (Clària & Titos, 2004). The layer of endothelial cells facilitates the exchange of substances between the blood and hepatocytes. In contrast, Kupffer cells support the phagocytic function by removing bacteria and other pathogens from the bloodstream.

The liver is also known for its regenerative capacity, which is unique among the solid organs in the human body. This phenomenon has been documented in all vertebrate organisms (ASSCAT, 2022). Following partial injury, the liver can regenerate through the proliferation of hepatocytes and restructuring of the parenchyma. This regenerative process does not compromise the organism’s health nor interfere with the liver’s essential functions for maintaining homeostasis in the human body.

3.2. Liver Functions

The liver performs more than 500 essential functions for maintaining homeostasis in the human body (American Liver Foundation, 2023). Some of these include the secretion of bile, the production of plasma proteins, the synthesis of cholesterol and proteins that enable fat transport, the regulation of amino acid levels in the blood, the processing of hemoglobin, and the storage of iron, among others. A significant portion of cholesterol is synthesized in the liver, while the rest comes from the diet. Most of the cholesterol produced in the liver is used to form bile.

Bile is a yellow-green fluid mainly composed of water, bile salts, bilirubin, cholesterol, and phospholipids. This fluid is produced by hepatocytes in the liver and, after synthesis, is stored in the gallbladder until needed for digestion. Bile is essential for the emulsification of fats. It transports waste and breaks down fats in the small intestine. Once this waste is broken down, it is eliminated from the body through feces (Lindenmeyer, 2022).

In addition to producing bile, the liver synthesizes essential elements for bodily function, such as albumin and globulins. It also produces amino acids and key enzymes such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), which participate in various biochemical pathways. Another of its functions is maintaining stable blood glucose levels. In low blood glucose conditions, the liver releases glucose and stores it as glycogen. The organ is also crucial for storing essential nutrients and maintaining reserves of vitamins B12, A, and C for extended periods (Maldonado, 2025).

Additionally, the liver acts as a blood filter, since all blood flow from the heart and intestines passes through it. The liver processes this flow, separates its components, and synthesizes the body's nutrients. Afterwards, the kidneys filter blood byproducts, eliminating waste from the body as urine (Stanford Medicine Children’s Health, 2025). Furthermore, the liver metabolizes medications in the bloodstream so they do not become toxic and can be effectively used by the body. This set of activities and functions makes the liver indispensable for maintaining metabolic balance and overall bodily function. A malfunction of this organ can lead to severe liver disease. Given the importance of these functions for the body's physiological balance, replicating them—partially or entirely—in a bioartificial organ is crucial to provide life support to patients with liver failure.

3.3. Liver Diseases

Liver diseases are conditions that affect the liver, also known as hepatic diseases. Various factors, including viral infections, hereditary diseases, fat accumulation, and excessive consumption of substances such as alcohol, can compromise the liver. Some of the most common liver diseases include cirrhosis, hepatitis A, B, and C, fatty liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, and Wilson's disease (Vega, 2013). In some cases, these conditions may progress to a point where a liver transplant becomes the only remaining treatment option (Maldonado, 2025).

Among infectious diseases, hepatitis A, B, and C are the most prevalent. These illnesses affect millions of people and represent a significant cause of morbidity and mortality (Zuckerman, 1996). Chronic active hepatitis, or autoimmune hepatitis, has an unknown origin and is characterized by prolonged liver inflammation until treated (Prieto et al.; 2019). In cases where the disease progresses, it can lead to cirrhosis, which requires liver transplantation (Marino, 2023). Hemochromatosis, on the other hand, falls under the category of hereditary disorders. It is an abnormal iron accumulation in tissues due to excessive intestinal absorption caused by genetic alterations. The excess iron stored in the liver can cause oxidative damage. If not treated in time, it can trigger chronic inflammation, eventually leading to cirrhosis (Wolff et al.; 2004).

Cirrhosis is a severe liver disease characterized by the substitution of healthy tissue with fibrotic tissue, which compromises liver function. Cirrhosis treatment focuses on slowing fibrosis progression and preventing symptoms. However, in advanced stages, this treatment becomes ineffective, making organ transplantation as the only option to prolong the patient's life. Cirrhosis is one of the main reasons for liver transplantation (American Liver Foundation, 2023). Due to the high demand and scarcity of available organs, the development of temporary support devices, such as the bioartificial liver, has been promoted. In this context, the bioartificial liver emerges as a strategic clinical tool.

3.4. Bioartificial Liver

Due to the progressive nature of many liver diseases in advanced stages, such as cirrhosis, therapeutic systems have been developed to provide functional support to the patient. At the same time, the organ recovers or a suitable donor is found. Bioartificial livers are extracorporeal devices that have emerged as a solution to temporarily replace the liver’s metabolic and other essential functions. These devices can utilize liver cells to eliminate toxins, regulate nutrients, and produce plasma proteins to help maintain blood balance.

The bioartificial liver (BAL) is an extracorporeal circulation device in which the patient’s blood or plasma flows through a bioreactor containing liver cells of various origins. The BAL is the most advanced liver support device (De La Mata et al.; 2002). It consists of a fermentation chamber with hollow fibers through which plasma or blood flows and then meets hepatocytes in a structure known as the bioreactor. These hepatocytes detoxify the fluid, participating in activities related to the cytochrome P450 system (enzymes responsible for metabolizing most antineoplastic drugs), ureagenesis (the primary process for removing ammonia from the body), and protein synthesis and replenishment.

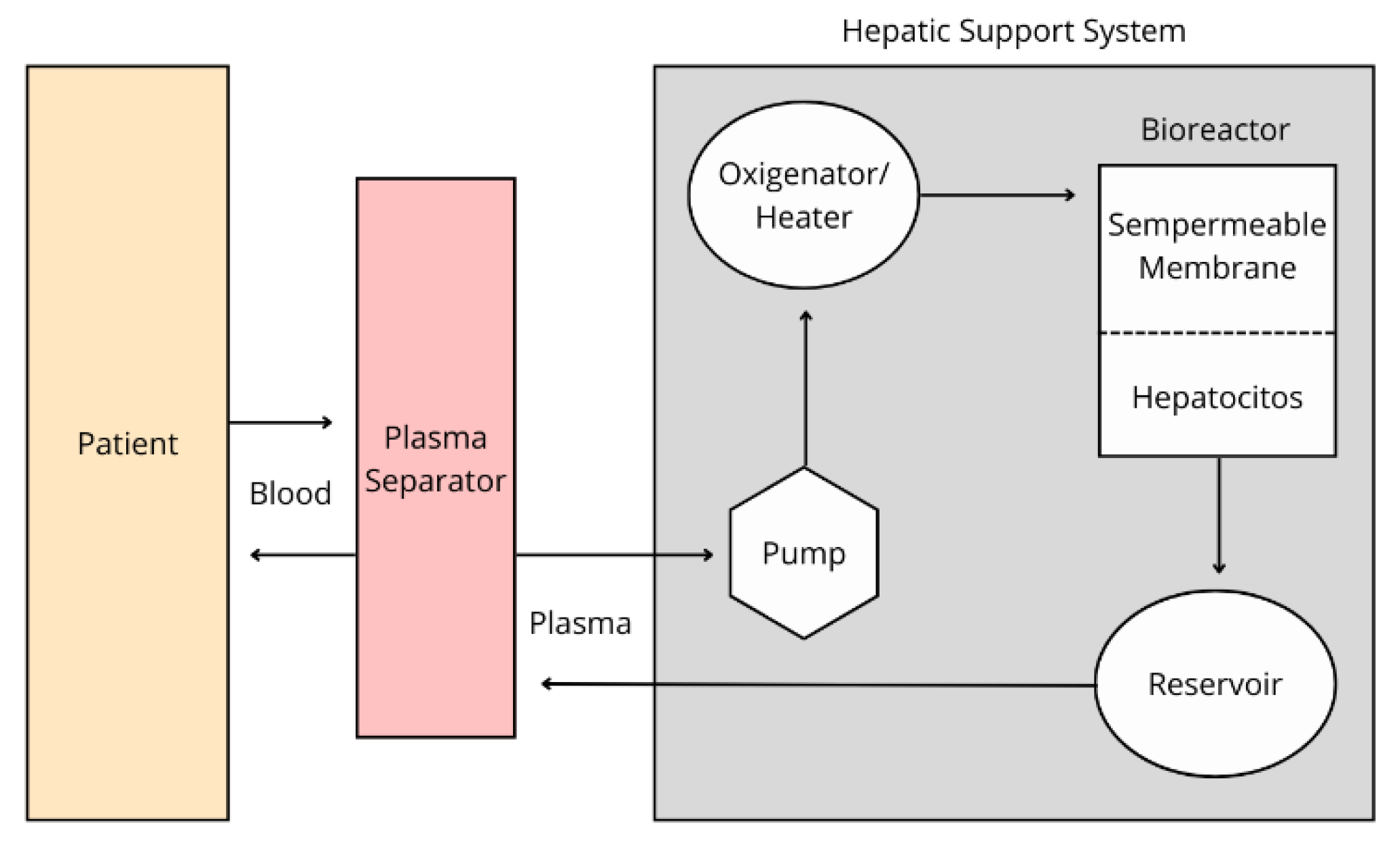

The BAL process begins when the patient’s blood is drawn through a dual-lumen catheter into the device. During this process, plasma or cellular components may be separated depending on the device used. The plasma or blood then passes through a charcoal filter, a heater that maintains body temperature, and an oxygenator before reaching the bioreactor. This bioreactor is the core of the device. It consists of a cartridge of hollow fibers that contain multiple semipermeable membranes. These fibers divide the interior into two compartments: the intramembrane space, where blood or plasma flows, and the extramembrane space, where hepatocytes are housed. The membrane allows for the exchange of low molecular weight molecules, enabling substances such as bilirubin, albumin, and coagulation components to re-enter the bloodstream. Finally, the blood or plasma is recombined with blood cells and returned to the patient (AESTA, 2015).

Figure 1.

Bioartificial Liver Process. Inspired from: Salmerón et al.; 2001.

Figure 1.

Bioartificial Liver Process. Inspired from: Salmerón et al.; 2001.

As liver assistance devices gain relevance, technology continues to evolve, resulting in various models. These systems are evaluated through experimental and clinical studies, combining biological and mechanical components. They differ in the type of bioreactors used and the sources and cell lines of hepatocytes. Nevertheless, all aim to replicate the natural organ’s function partially (Ariza et al.; 2011).

3.5. Extracorporeal Liver Assist Devices

The development of BAL (bioartificial liver) devices has been one of the most promising strategies for the temporary treatment of liver failure, particularly as support during recovery or while awaiting transplantation. These devices are designed to mimic liver functions partially, integrating the use of hepatocytes and extracorporeal perfusion systems (Bain et al.; 2001). The methods of extracorporeal circulation differ in specific characteristics such as the type of cells used, bioreactor design, perfusion system, and therapeutic effectiveness based on patient conditions (AESTA, 2015).

Currently, several liver support devices exist. While many are still in the experimental stage, some of the most recognized worldwide include:

HepatAssist®: This was the first system approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical studies only. This device acts as a temporary external liver, helping to cleanse the blood and perform essential liver functions using porcine hepatocytes. It integrates a perfusion system with walls coated in activated charcoal and cellulose. Also, it contains a heater/oxygenator and a hollow fiber bioreactor with approximately 7×10⁹ porcine hepatocytes in the extramembrane space (AESTA, 2015).

Extracorporeal Liver Assist Device® (ELAD®): This device is based on a hollow fiber bioreactor containing approximately 100g of C3a cells in the extramembrane space (Millis et al.; 2002). The semipermeable membrane separating the compartments facilitates the exchange of low molecular weight molecules, allowing the plasma to be detoxified and enriched with proteins and other essential metabolites.

Bioartificial Liver Support System® (BLSS®): This system also contains a mechanism similar to those described above. It includes a hollow fiber bioreactor with membranes made of cellulose acetate. The extramembrane space holds approximately 70 to 100g of porcine hepatocytes (Mazariegos, 2002). Although still experimental, the BLSS represents a promising option due to its versatility and responsiveness.

Modular Extracorporeal Liver Support® (MELS®): This system is based on an adaptable approach, combining different extracorporeal modules according to patient needs. It mainly consists of a bioreactor loaded with human hepatocytes. Additionally, it includes a detoxification module that performs albumin dialysis using a high-permeability filter (Sauer, 2002).

Amsterdam Medical Center Bioartificial Liver (AMC-BAL): This liver support system contains a hollow fiber bioreactor covered in polysulfone. It holds between 10 to 14 ×10⁹ hepatocytes configured to more accurately replicate the natural liver environment (AESTA, 2015).

3.6. Challenges and Limitations of the Bioartificial Liver

Despite the progress achieved by the BAL (bioartificial liver) as a temporary alternative to liver transplantation, its clinical implementation still faces significant challenges that limit widespread use. Although there have been meaningful advancements in the design of bioreactors, perfusion systems, and cell selection, structural and functional limitations must be overcome. Some of these limitations directly affect the production of plasma proteins and other essential components necessary for human homeostasis.

3.6.1. Biological Challenges

One of the main limitations of the BAL is that an optimal cell source to perform liver functions has yet to be identified (Zhao et al.; 2012). Many devices use porcine hepatocytes, while others use human cells, such as C3a cells, which present functional and immunological limitations. The C3 a fragment is derived from the C3 protein, part of the complement system—a network of plasma proteins essential for immune response and host defense (Ishii et al.; 2021). Human hepatocytes are ideal due to their metabolic capacity, but they are expensive and challenging to obtain. Additionally, these cells have a short lifespan in crops, making maintaining their functionality throughout treatment challenging.

3.6.2. Technical Challenges

The bioreactor’s inability to process bile secretion is a significant technical challenge. Current devices still lack a mechanism to remove bile from the extracorporeal system (Ali et al.; 2021). Another significant issue is the technical complexity of these devices. This complexity requires trained personnel to operate the systems, manage the cells, and handle the surrounding external devices. These therapies must be administered in intensive care units, making the maintenance costs of the device relatively high.

3.6.3. Economic Challenges

One of the most significant obstacles the BAL faces is its high clinical implementation cost. Despite its potential to reduce mortality in patients with liver diseases, the costs associated with production, maintenance, and application significantly limit its use. Designing and manufacturing functional bioreactors, employing high-quality cell lines, and operating the necessary perfusion systems require substantial investment. Additionally, specialized personnel are needed for techniques such as plasmapheresis, cell cryopreservation, and intensive patient management, which further increase the expenses.

3.7. Future Perspectives

3.7.1. Technical Advancements

In the coming years, the bioartificial liver promises to transform the device's design and functionality significantly. One of the main areas of research focuses on incorporating multicellular models such as Kupffer cells, sinusoidal endothelial cells, and stellate cells, among other cellular components of the liver. This integration would allow for a more accurate replication of the liver’s microstructure while simultaneously enabling metabolic, immunological, and endocrine functions. Additionally, studies are exploring the use of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which offer an unlimited and personalized alternative. These applications will allow for the generation of patient-specific cells, improving cell compatibility and reducing immunological risk (Maldonado, 2025).

Moreover, technologies such as 3D bioprinting and three-dimensional scaffolds are being used to create structures that more closely mimic the cellular environment of the liver. Tissue engineering aims to simulate mammalian organs' function and structure (Rondón et al.; 2025). These techniques promote cell adhesion, biocompatibility, and long-term functionality of cells within the bioreactor. Miniaturized and portable systems are also being developed to improve access to extracorporeal liver assistance devices, allowing their use outside intensive care units. These innovations offer new hope in the face of the liver transplant crisis by providing positive outcomes for patients suffering from severe liver diseases, offering them a new therapeutic opportunity.

3.7.2. Bioethical Considerations

As bioartificial liver technology advances, relevant bioethical considerations arise. Using animal cells, human tumor cell lines, or stem cells raise questions about safety, informed consent, and genetic manipulation. The field of bioethics focuses on analyzing ethical arguments and addressing the dilemmas posed by scientific advancements (Rondón et al.; 2024), such as those involving bioartificial organs. Therefore, the development of this technology must be accompanied by clear ethical guidelines that ensure equity, transparency, and respect for patient rights.

Early clinical trials involving bioartificial organ transplantation also present serious bioethical challenges, especially concerning how risks and benefits are assessed, how patients are selected, and how informed consent is ensured (Bunnik et al.; 2022). Due to the complex and invasive nature of bioartificial liver technology, these concerns are significant. Unlike other medical treatments, integrating cells and tissues into the body requires that consent be legally valid and ethically sound. For this reason, bioethics serves as a guiding framework to ensure that biomedical engineering practices and developments are conducted ethically and responsibly, for the benefit of society (Rondón et al.; 2024).

4. Conclusion

The bioartificial liver represents one of the most promising biomedical engineering and regenerative medicine innovations. Throughout this research, it has been shown that, due to the increasing prevalence of liver diseases such as cirrhosis, viral hepatitis, fatty liver disease, liver failure, and hemochromatosis, the high demand for liver transplants has created an urgent need for alternative therapies. Liver transplantation remains the definitive treatment for many of these conditions, but it presents critical limitations such as donor scarcity, high costs, and risks associated with immunosuppression. The bioartificial liver emerges as a therapeutic tool that can potentially improve the quality of life for patients awaiting organ recovery or transplantation.

The bioartificial liver (BAL) is an extracorporeal system through which the patient's blood or plasma circulates within a bioreactor containing functional hepatocytes. These cells partially replicate essential functions of the natural liver, such as detoxification, plasma protein synthesis, metabolism, and regulating the human body’s biochemical balance. With the growing interest in liver assistance devices, technology has advanced significantly, resulting in various models. The analyzed models demonstrate the progress of this technology, opening the path to clinical applications and even the development of portable systems. While clinical studies have not yet shown a significant reduction in mortality, they show improvements in patients’ biochemical parameters, indicating that further research and development of this device are still required.

The bioartificial liver constitutes an emerging frontier in modern medicine. Its potential to become a clinical tool depends on the effective integration of technological innovation, biomedical knowledge, ethical analysis, and clinical validation. The advancement of these elements will soon make it possible for this technology to complement and transform the therapeutic landscape of liver diseases, offering a second chance to thousands of patients with no viable treatment options.

Funding

This research was funded by Biomedical Engineering Department, Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico, PR 00918 USA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ali, S.; Haque, N.; Azhar, Z.; Saeinasab, M.; Sefat, F. Regenerative Medicine of Liver: Promises, Advances and Challenges. Biomimetics 2021, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Liver Foundation. (2023). ¿Cuántas personas tienen enfermedad hepática? Available online: https://liverfoundation.org/es/sobre-tu-h%C3%ADgado/datos-sobre-la-enfermedad-hep%C3%A1tica/%C2%BFCu%C3%A1ntas-personas-tienen-enfermedad-hep%C3%A1tica%3F/.

- Ariza Cadena, F.; Carmona Serna, L.F.; Quintero, I.F.

- Caicedo, L.A.; Vidal Perdomo, C.A.; González, L.F. Sistemas de soporte hepático extracorpóreo. Colombian Journal of Anestesiology 2011, 39, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASSCAT. (2022). La terapia de regeneración celular restaura el tejido hepático dañado de una forma más rápida. Asociación Catalana de Pacientes Hepáticos. Available online: https://asscat-hepatitis.org/la-terapia-de-regeneracion-celular-restaura-el-tejido-hepatico-danado-de-una-forma-mas-rapida/.

- Bain, V.G.; Montero, J.; García, M. Bioartificial Liver Support. Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterology 2001, 15, 313–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnik, E.M.; De Jongh, D.; Massey, E. Ethics of early clinical trials of Bio-Artificial Organs. Transplant International 2022, 35, 10621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clària, J.; Titos, E. La célula de Kupffer. Gastroenterología y Hepatología 2004, 27, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Mata, M.; Montero, J.L.; Pozo, J.C. Hígado bioartificial: De la biotecnología a la aplicación clínica. Unidad Clínica de Aparato Digestivo y Unidad de Trasplante Hepático. Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía. Córdoba 2002, 1, 232–234. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, S.J.; Newsome, P.N. Liver regeneration—mechanisms and models to clinical application. Clinical Liver Disease 2016, 13, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabel Gómez, Rebeca & Parejo, Joaquín & Méndez, Aurora & Baños, Elena. (2015). Bioartificial liver. Systematic Review = Hígado bioartificial. Revisión Sistemática. Available online: https://www.aetsa.org/download/publicaciones/Higado-bioartificial_final.pdf.

- Ishii, M.; Beeson, G.; Beeson, C.; Rohrer, B. (2021). Mito-chondrial C3a Receptor Activation in Oxidatively Stressed Epithelial Cells Reduces Mitochondrial Respiration and Metabolism. Front Immunol. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, M. Anatomía microscópica del hígado. Clinical Liver Disease 2013, 2, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemeyer, C. (2022). Hígado. Manual Merck, versión para público general. Cleveland Clinic. Available online: https://www.merckmanuals.com/es-us/hogar/trastornos-del-hígado-y-de-la-vesícula-biliar/biología-del-hígado-y-de-la-vesícula-biliar/hígado.

- Maldonado, J. (2025). Implantable Artificial Liver: A Brief Review. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.P. Hepatitis autoinmune: conceptos actuales. Acta Gastroenterológica Latinoamericana 2023, 53, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazariegos, G.; Patzer, J.F.; Lopez, R.; et al. (2002). First Clinical Use of a Novel Bioartificial Liver Support System (BLSS), American Journal of Transplantation, (Pages 260-266, ISSN 1600-6135). [CrossRef]

- Megías M, Molist P, & Pombal MA. (2025). Hepatocito. Atlas de Histología Vegetal y Animal. Universidad de Vigo. Recuperado 28 de abril, 2025 de. Available online: http://mmegias.webs.uvigo.es/inicio.html.

- Millis, J.M.; Cronin, D.C.; Johnson, R.; Conjeevaram, H.; Conlin, C.; Trevino, S.; Maguire, P. Initial experience with the modified extracorporeal liver-assist device for patients with fulminant hepatic failure: system modifications and clinical impact. Transplantation 2002, 74, 1735–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto Ortiz, J.E.; Preciado, J.; Huertas Pacheco, S. Hepatitis autoinmune. Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología 2012, 27, 303–315. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. (2025). Hepatitis. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/health-topics/hepatitis.

- Rondón, J.; Sánchez Martínez, V.; Lugo, C.; González-Lizardo, A. (2025). Tissue engineering: Advancements, challenges and future perspectives. Ciencia e Ingeniería, 46, 19-28. Available online: http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/cienciaeingenieria/article/view/20607.

- Rondón, J.; Muniz, C.; Lugo, C.; Farinas-Coronado, W.; Gonzalez-Lizardo, A. (2024). Bioethics in Biomedical Engineering. Ciencia e Ingeniería. 45. 159-168. Available online: http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/cienciaeingenieria/article/view/19768.

- Salmerón, J.; Lozano, M.; Agustí, E.; Mas, A.; Mazzara, R.; Marín, P.; Ordinas, A.; Rodés, J. (2001). Soporte hepático bioartificial en la insuficiencia hepática aguda grave: Primer caso tratado en España. Medicina Clínica, 117, 781-784. Available online: https://www.elsevier.es/es.

- Sauer IM, Zeilinger K, Obermayer N, et al. (2002). Primary Human Liver Cells as Source for Modular Extracorporeal Liver Support - a Preliminary Report. The International Journal of Artificial Organs, 25, 1001-1005. [CrossRef]

- Stanford Medicine Children’s Health. (2025). Anatomía y función del hígado. Available online: https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/es/topic/default?id=anatomy-and-function-of-the-liver-90-P06162.

- Tholey, D. (2023). Insuficiencia hepática Trastornos del Hígado y de la Vesícula Biliar. Manual Merck versión para el público general. Available online: https://www.merckmanuals.com/es-us/hogar/trastornos-del-h%C3%ADgado-y-de-la-ves%C3%ADcula-biliar/manifestaciones-cl%C3%ADnicas-de-las-enfermedades-hep%C3%A1ticas/insuficiencia-hep%C3%A1tica.

- Vega, P.A.B. (2013). Enfermedades Hepáticas. Gastroenterología Clínica 2, 16. Available online: https://cuevaseditores.com/libros/Gastroenterologiaclinicavol.2.pdf#page=17.

- Wolff, F.C.; Carreño, N.M.A.; Armas, M.R.; Cavallo, V.A. (2004). Hemocromatosis hereditaria. Complicaciones reumatológicas. Hospital San Juan de Dios; Universidad de Chile. Available online: https://sochire.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/r-166-1-1343619123.pdf.

- Zhao, L.; Pan, X.; Li, L. Key challenges to the development of extracorporeal bioartificial liver support systems. Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International 2012, 11, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, A.J. (1996). Hepatitis Viruses. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. Chapter 70. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7864/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).