Submitted:

17 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Data Availability: Utilities and operators rarely disclose EV charging data to protect private, legal, and competitive interests. Although the dataset is made available, some features, such as regions, stations, or periods, remain limited, which makes generalization difficult.

- Data Scale: The limited size and scope of real datasets may result in poor performance of machine learning algorithms. A large amount of data is needed to train many machine learning-based models. The size and minor issues with datasets can be addressed by generating synthetic datasets [4].

- Data Privacy: Data from EV about distribution systems includes personally identifiable information (PII). The restrictions require the use of complex techniques to anonymize the data. This makes such datasets even more challenging to make widely available.

- Supports Grid Planning and Load Forecasting: The demand for EV charging is time-dependent and dynamic; if improperly controlled, it could cause grid instability. Synthetic data helps the grid to simulate • Peak demand scenarios • Load shifting (e.g., smart scheduling) • Infrastructure stress testing (e.g., transformer loads, feeder capacities). Thus, the grid operation can be optimized before issues arise, allowing utilities to forecast future adoption scenarios.

- Explored various generative models to generate synthetic data for EV data defined as the SDG.

- The real-world dataset was employed by different SDGs not only for training but also to learn the distribution pattern to ensure the realistic generation of synthetic EV data.

- An analysis of various metrics has been performed to determine the statistical properties of real-world data.

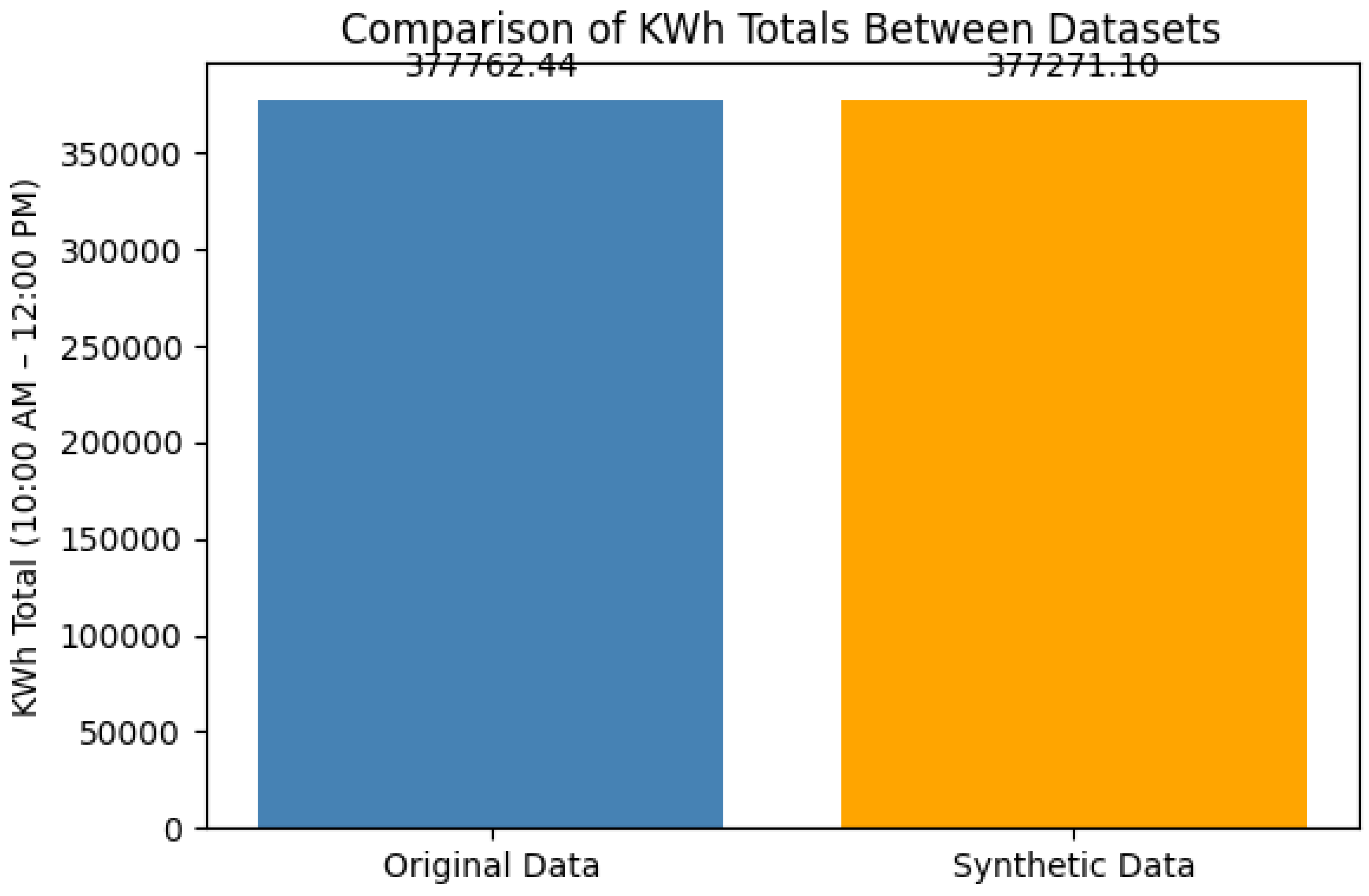

- Synthetic sample generation and comparison to real-world data. We evaluate the outcomes of various models that may be implemented in the SDG.

2. Background

2.1. Data-Driven Synthetic Data Generator (SDG)

- 1) Machine Learning Approach: The primary objective of synthetic data is to supply additional training data for machine learning applications or an alternative to preserve the privacy of the original dataset. These machine-learning methods’ results don’t differentiate between real-time and synthetic time series.

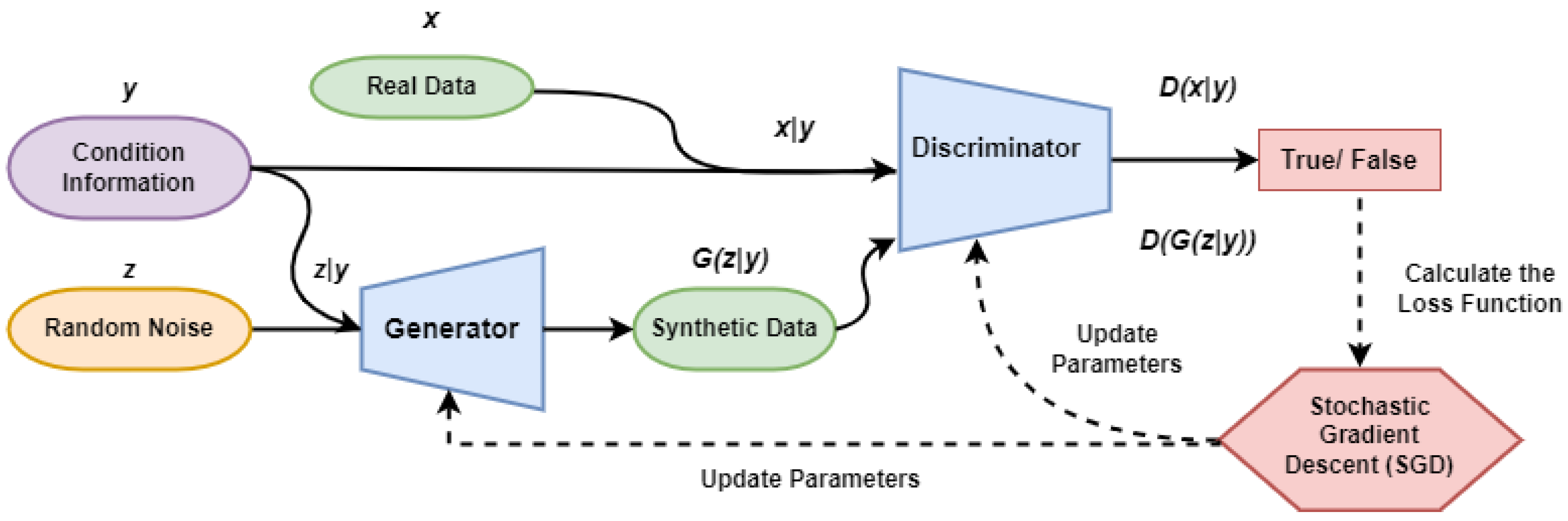

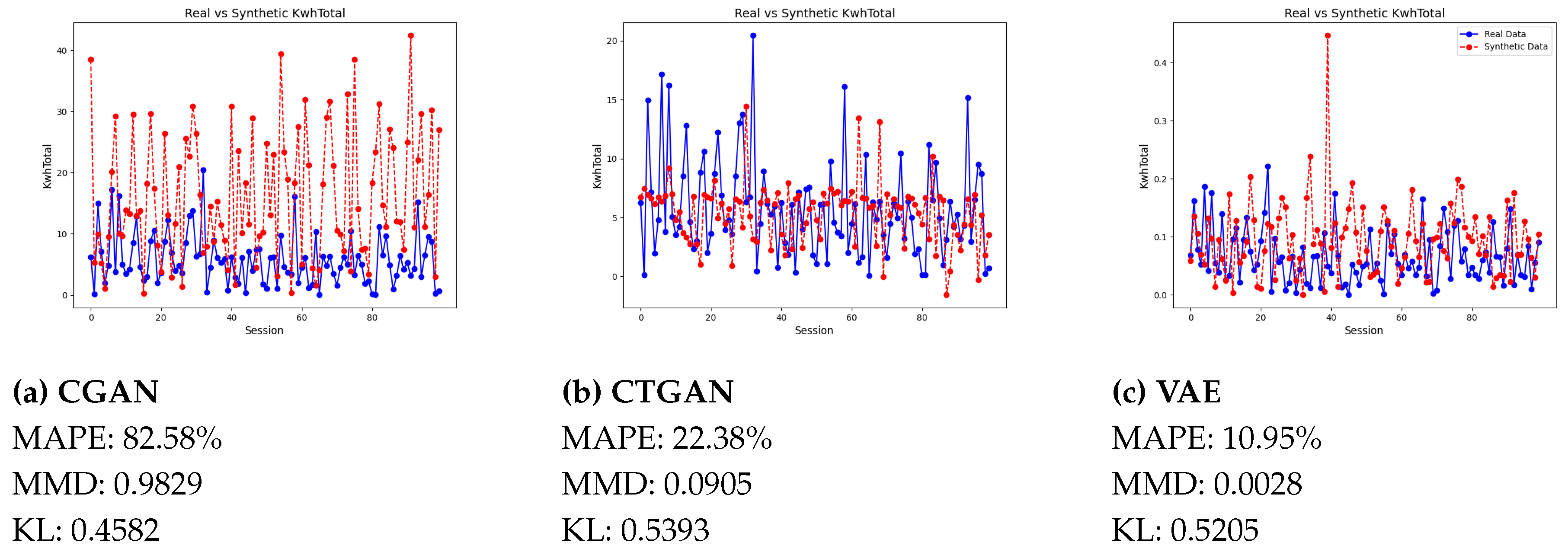

- a) Conditional GAN (CGAN): Conditional GANs are becoming more and more popular because of the limitations of GANs in regulating generated data. Its conditional vector allows you to specify that a specific data class should be generated [7]. This capability is crucial when we need synthetic data of a particular class to re-balance the distribution due to limited and highly skewed data.

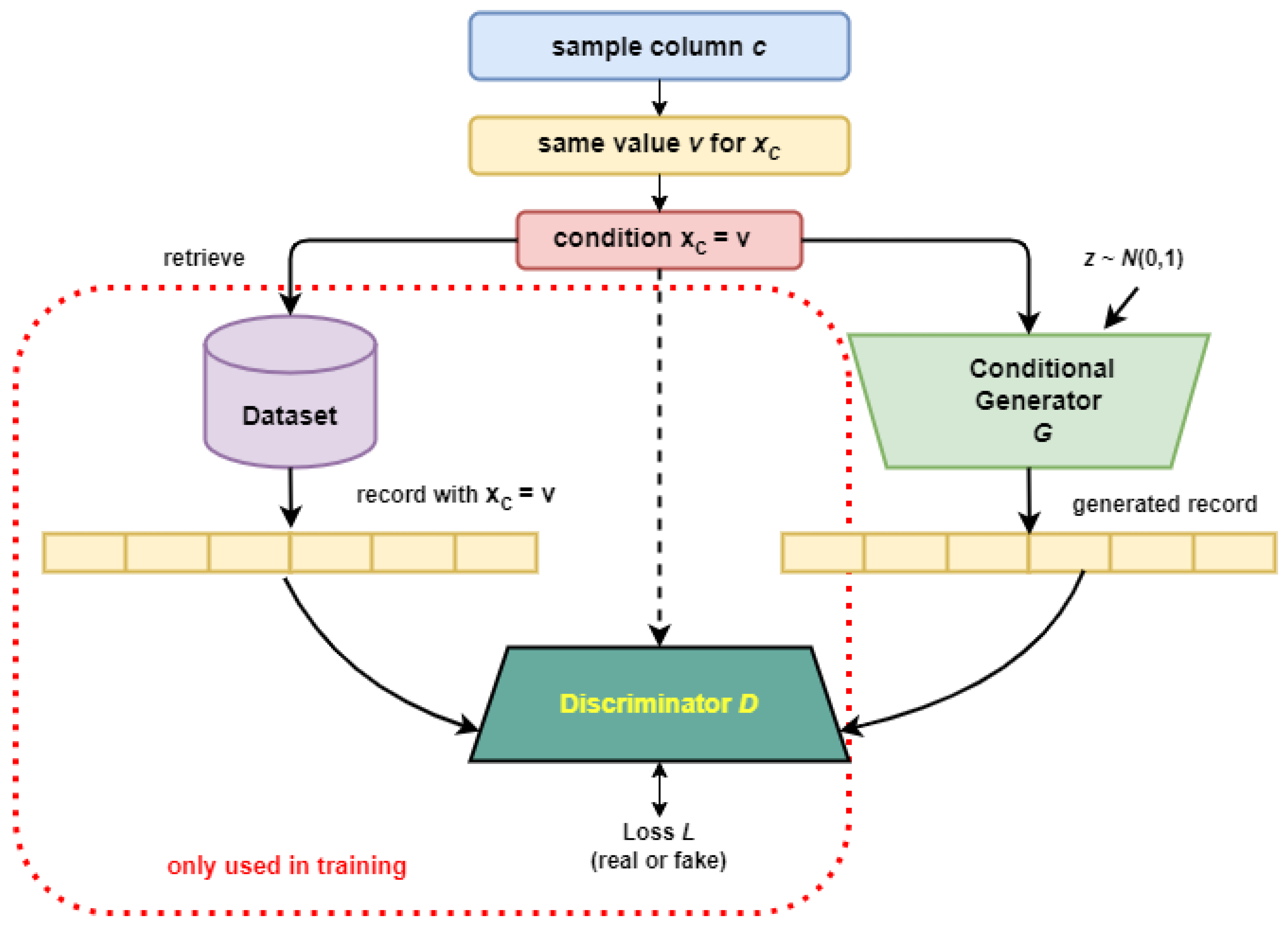

- b) Conditional Tabular GAN (CTGAN): The conditional generator receives a random input and a condition that has been sampled first as presented in Figure 3. A randomly selected example from the data collection that satisfies the criteria and is evaluated by the conditional discriminator contrasts with the generated sample [10]. This method enables the maintenance of dependency relationships. In the pre-processing phase, the DateTime features (i.e., StartTime and EndTime) of the dataset were first formatted into datetime format and then converted into decimal values.

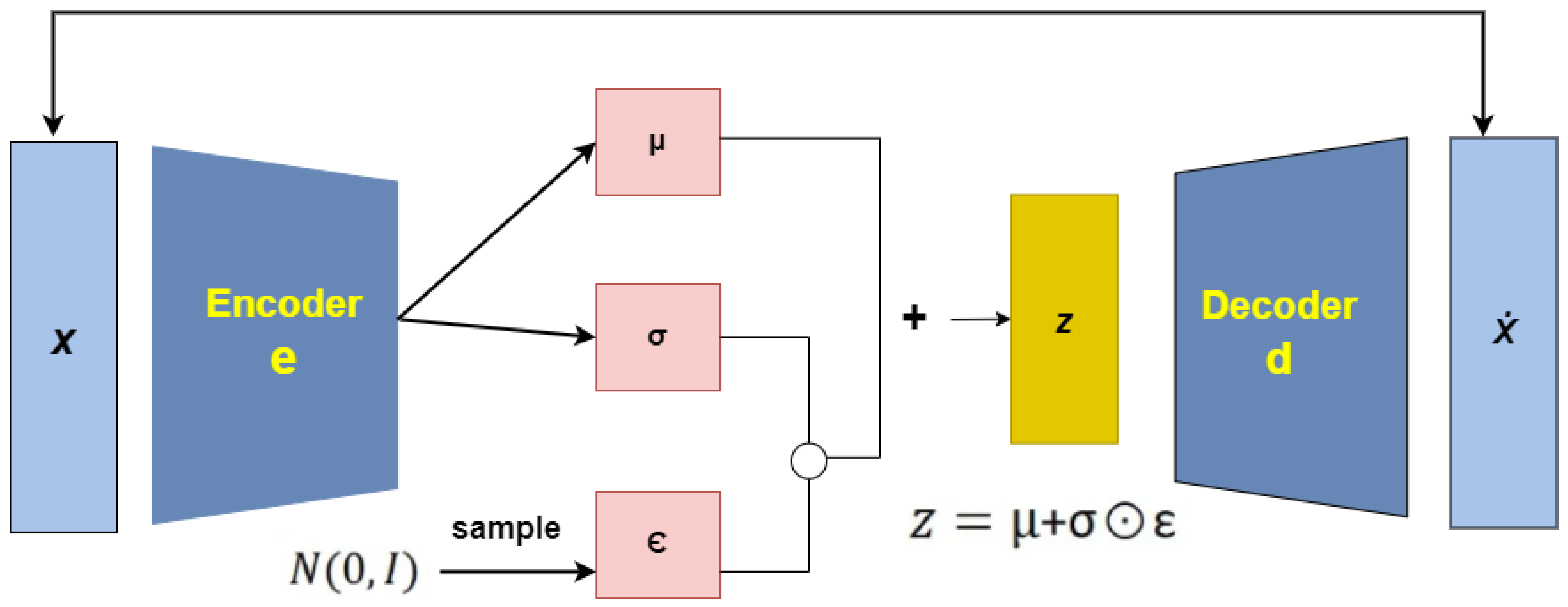

- c) Variational Autoencoder (VAE): An unsupervised neural network known as an autoencoder compresses input data into a latent space and reassembles it into the original input. The encoder module in this network utilizes mean and variance vectors to construct the latent space, where the input sequence is encoded as a Gaussian distribution[11]. It consists of two parts: an encoder, which maps input x to latent space z, and a decoder, which reconstructs x from z, as depicted in Figure 4. Although standard autoencoders minimize reconstruction error, their latent spaces can be irregular, resulting in overfitting and poor interpolation. Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) address this by adding a regularization term—the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence—to the training objective, encouraging the latent space to follow a Gaussian distribution. Instead of mapping inputs directly to a point, the VAE encoder outputs mean and variance vectors and samples are drawn from the resulting distribution [12,13]. Here the data pre-processing steps for this model follow the same approach as those for CGAN, as mentioned earlier. The total VAE loss combines reconstruction loss and KL divergence, ensuring better latent space structure and more robust decoding.

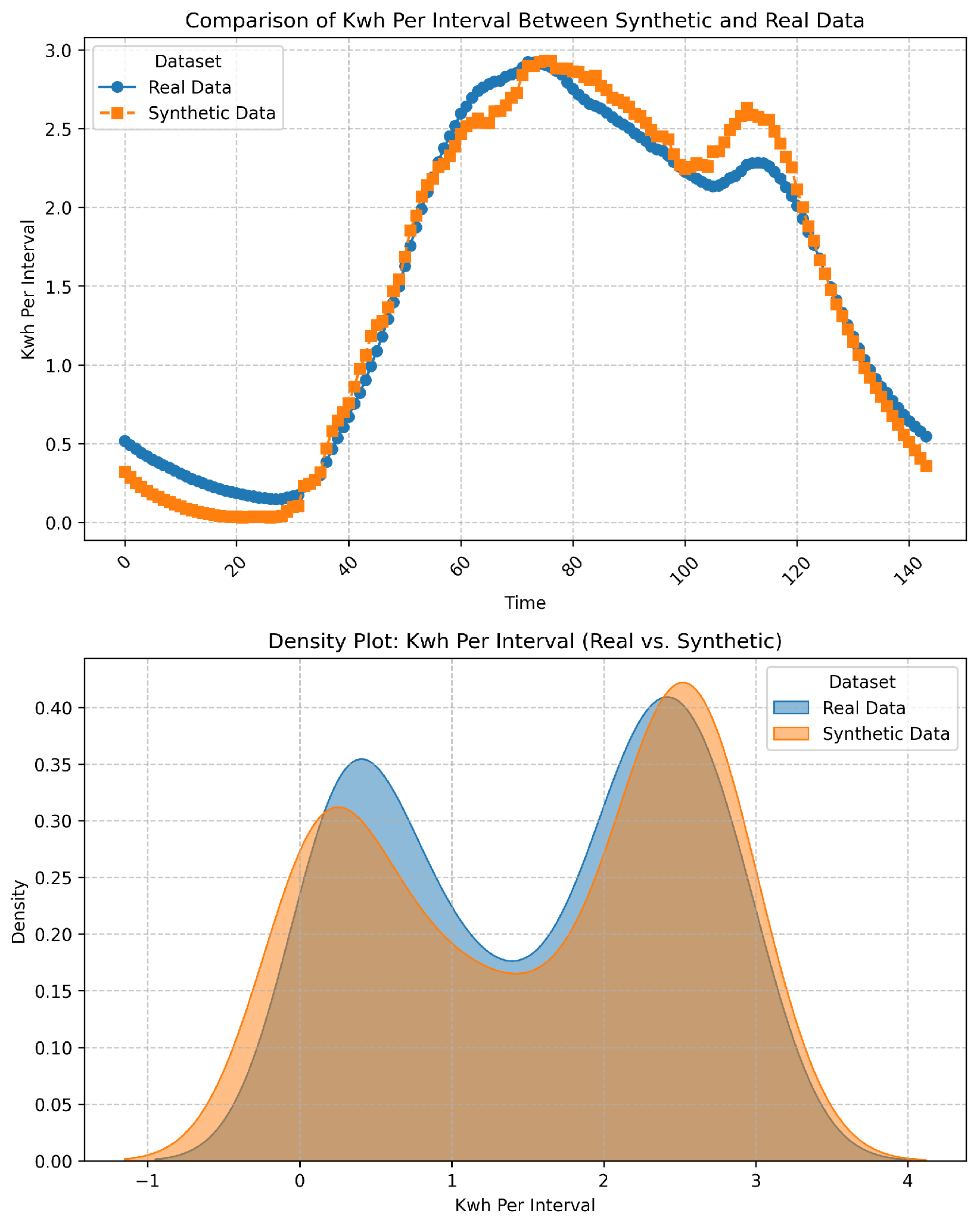

- 2) Distribution Based Models: Realistic EV statistics, which are challenging to get. Besides conventional ML techniques, heuristic methods are also necessary to examine such scenarios and generate synthetic data that retains the same probabilistic density or distribution as the real dataset. Distribution-based models serve as an effective approach to generating synthetic data for electric vehicle charging stations, particularly when the objective is to mimic the statistical characteristics of actual activity without requiring intricate model structures.

- a) KDE-based Generative Model: One popular technique for estimating the underlying probability distribution of a short dataset is Kernel Density Estimation (KDE), an acronym for kernel density estimation. Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) is a popular non-parametric method for estimating the probability density function (PDF) of a dataset, especially when data is limited. It applies a kernel (typically Gaussian) to each data point to produce a smooth approximation of the underlying distribution. Synthetic samples are generated by sampling from this estimated PDF, ensuring the synthetic data closely reflects the statistical properties—such as shape and skewness—of the original dataset. This guarantees that the synthetic data statistically mirrors the original data, particularly for distributional characteristics (unimodal, multimodal, skewness, etc.). It is especially beneficial when one intends to preserve the identical statistical distribution in the synthetic dataset. Explicit density estimation and other more straightforward techniques are often used to represent limited tabular data [14,15]. When considering the probability distribution approximation from the user’s perspective, KDE offers several benefits [4]. In 1, we present a framework where the model learns the underlying probability distributions of the real data and then samples from those distributions to create new, synthetic data points. According to the findings, KDE outperforms CGAN on the same dataset and produces high-quality synthetic samples. Real datasets and samples from theoretical distributions are used to evaluate the performance of KDE.

| Algorithm 1 Generating Synthetic EV Charging Data Using KDE. |

|

- b) Probability-based Generative Model: In this study, we propose another SDG, a heuristic model to directly "learn" the probability distribution of the real time-series EV charging data, thereby generating synthetic data. This suggests modelling arrivals and charging time using temporal statistics as well as the related electrical load (i.e., charged energy). A probabilistic method or probability density functions (PDF) has been employed here to train the real-world EV charging dataset, generating realistic data samples of EV sessions rather than using traditional machine learning models. Here, the arrival times of EVs are modelled under the assumption that their inter-arrival times adhere to an exponential distribution. The connection duration for EVs depends on their arrival time and can be characterized by a conditional probability distribution. This distribution is estimated utilizing Gaussian mixture models, and departure times can be computed by sampling connection times for electric vehicle arrivals from this distribution.

3. Synthetic Dataset Evaluation

- MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error): A statistical metric called MAPE is used to evaluate the performance of regression models or forecast accuracy. In terms of percentage, it indicates the average difference between predictions and actual values.

- MMD (Maximum Mean Discrepancy): A statistical metric used to quantify the difference between two probability distributions is KL divergence. In the context of synthetic data, it measures the difference between the generated (synthetic) data distribution and the real data distribution. For two distributions P and Q, using kernel k:

- KL Divergence (Kullback–Leibler Divergence): KL divergence is a statistical measure that quantifies how one probability distribution differs from another. In the context of synthetic data, it measures how different your generated (synthetic) data distribution is from the real data distribution. For two distributions P and Q:

4. Conclusion

References

- Lahariya, M.; Benoit, D.F.; Develder, C. Synthetic data generator for electric vehicle charging sessions: modeling and evaluation using real-world data. Energies 2020, 13, 4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Byun, Y.C. A synthetic data generation technique for enhancement of prediction accuracy of electric vehicles demand. Sensors 2023, 23, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Kuppannagari, S.R.; Kannan, R.; Prasanna, V.K. Generative adversarial network for synthetic time series data generation in smart grids. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE international conference on communications, control, 2018, and computing technologies for smart grids (SmartGridComm). IEEE; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Plesovskaya, E.; Ivanov, S. An empirical analysis of KDE-based generative models on small datasets. Procedia Computer Science 2021, 193, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawin, B.; Małkowski, R.; Główczewski, K.; Olszewski, M.; Tomasik, P. Dataset for Event-Based Non-Intrusive Load Monitoring Research. Journal Name 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara-Ouali, Y. EV Charging station dataset. https://github.com/yvenn-amara/ev-load-open-data?tab=readme-ov-file. [Online]. Available).

- Zhao, Z.; Kunar, A.; Birke, R.; Chen, L.Y. Ctab-gan: Effective table data synthesizing. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2021; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional generative adversarial nets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1411.1784, arXiv:1411.1784 2014.

- Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Fu, Q.; Song, Y.; Liu, J. IH-TCGAN: time-series conditional generative adversarial network with improved Hausdorff distance for synthesizing intention recognition data. Entropy 2023, 25, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Skoularidou, M.; Cuesta-Infante, A.; Veeramachaneni, K. Modeling tabular data using conditional gan. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Razghandi, M.; Zhou, H.; Erol-Kantarci, M.; Turgut, D. Smart home energy management: VAE-GAN synthetic dataset generator and Q-learning. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2023, 15, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razghandi, M.; Zhou, H.; Erol-Kantarci, M.; Turgut, D. Variational autoencoder generative adversarial network for synthetic data generation in smart home. In Proceedings of the ICC 2022-IEEE International Conference on Communications. IEEE; 2022; pp. 4781–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, R. Variational Autoencoder(VAE). https://medium.com/geekculture/variational-autoencoder-vae-9b8ce5475f68. [Online]. Available: https://example.com (accessed: Apr. 26, 2025).

- Kamalov, F. Kernel density estimation based sampling for imbalanced class distribution. Information Sciences 2020, 512, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokwitthaya, C.; Zhu, Y.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Jafari, A. Applying the Gaussian mixture model to generate large synthetic data from a small data set. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2020. American Society of Civil Engineers Reston, VA; 2020; pp. 1251–1260. [Google Scholar]

| Model Name | Python Library | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CTGAN | SDV Tabular | Fits a conditional GAN model adapted for tabular data generation, with ability to model discrete and continuous columns. |

| CGAN | SDV Tabular | Adapts a GAN model that is conditional, designed for tabular data generation. |

| VAE | TensorFlow/Keras or PyTorch | Keras simplifies defining encoder, decoder,and loss functions while PyTorch offers more VAE architecture flexibility. |

| Generative modeling (KDE) | scipy.stats | It’s a statistical method utilizing Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) for generative modeling of random variables. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).