Introduction

1.1. Background Context

Understanding skin cancer mortality patterns among older Americans has become increasingly urgent as this population grows and healthcare costs soar. Skin cancer poses a greater challenge to U.S. Medicare patients. It creates huge outpatient visit load and treatment costs[

1,

2]. Adults aged 65 and older make up an increasing share of skin-cancer deaths and this trend continues to increase [

3]. While basal and squamous cell carcinomas occur most frequently in this older population, melanoma accounts for higher mortality rates due to its aggressive metastatic potential[

4,

5]. Global studies show that mortality in elderly population due to melanoma continues rising. By contrast, non-melanoma skin cancers haven’t improved much since the 1990s [

6,

7,

8].

From a public health perspective, studying melanoma and keratinocyte cancers together makes sense because both stem from UV damage and share similar prevention strategies. Since both cancer types develop after years of UV damage combined with late diagnosis, studying them together shows us exactly where prevention and treatment programs need the most attention. This combined approach gives us a complete picture of the skin cancer burden that healthcare planners need to address. Our study therefore analyzes combined C43–C44 mortality using Multiple Cause of Death (MCOD) data rather than underlying cause only, to capture the full UV-related mortality burden in adults ≥65. Mortality patterns in the ≥ 65 population offer practical guidance for healthcare service planning. To our knowledge, no prior national study has integrated a 25-year series for combined melanoma and keratinocyte cancers with concurrent stratification by sex, race/ethnicity, region, and urban–rural status in this age group.

1.2. Contemporary Epidemiology

Melanoma mortality in the U.S. continued its upward climb through the early 2010s, then began leveling off temporally coinciding with immune-checkpoint treatments entering standard practice around 2015-2018 [

5]. From a clinical standpoint, non-melanoma skin cancer deaths follow a different trajectory; they’ve increased steadily, especially across Sunbelt regions [

8]. This divergent pattern may reflect differential treatment efficacy for different cancer types. Most countries worldwide report increase in melanoma incidence, though several developed nations now report modest decreases in death rates [

7]. Earlier detection and better treatment options may explain this shift. Keratinocyte cancers haven’t demonstrated similar improvements [

8]. CDC WONDER mortality data provides one accessible way to monitor these trends over time [

9].

1.3. Biological and Care-Delivery Considerations

Decades of sun exposure cause extensive somatic mutations in sun-damaged skin [

10]. Aging brings less effective immune surveillance and abnormal growth regulation; some individuals may experience immunosuppression [

11]. Clinical evidence demonstrates that physical limitations in older adults often lead to melanoma presentations that average 0.7 mm thicker than those found in middle-aged patients [

12]. While checkpoint inhibitors may be effective in healthy elderly patients, treatment adherence may be compromised by early discontinuation or treatment refusal due to patient concerns [

13]. These biological and care-delivery factors may differentially influence melanoma and keratinocyte cancer mortality in late life, reinforcing the need to report combined and stratified trends.

1.4. Persistent Disparities

Non-Hispanic White patients represent most skin cancer cases, yet Black, Hispanic, Asian and American Indian adults experience worse survival rates. Cancer often gets diagnosed at advanced stages in these populations [

14,

15,

16]. Rural residents face particularly significant barriers to care, with melanoma death rates running about one-third higher than urban areas, mainly due to specialist shortages and longer travel distances [

17]. The skin cancer prevention campaign demonstrates unequal penetration across various demographic regions. The 2021 National Health Interview Survey data showed only one in six adults over 65 used sun protection consistently, while one in five reported recent sunburns [

18]. Given rising mortality and persistent gaps by geography and race/ethnicity, quantifying subgroup trends in older adults is a public-health priority.

1.5. Knowledge Gaps and Study Aim

The 2014 Surgeon General’s Call to Action made skin cancer prevention a federal priority [

19]. Analysis of population-level data revealed a critical knowledge gap. Current research lacks comprehensive understanding of temporal associations between immunotherapy adoption and pandemic-related healthcare disruptions with mortality patterns. Most U.S. trend studies focus on melanoma alone or shorter time spans and seldom pair demographic, geographic, and urban–rural stratification in one analysis. Our study had dual objectives: (a) document long-term age-adjusted mortality trends and (b) quantify disparities across sex, race/ethnicity, urban-rural status, and geographic regions. We use MCOD data (1999–2023) to provide stable estimates for combined C43–C44 mortality in adults ≥65. The findings of this investigation would help public-health officials target their prevention, screening, and treatment programs [

9,

20,

21].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

Our population-based retrospective study examined U.S. Multiple Cause-of-Death (MCOD) files spanning 1999 through 2023, accessed via CDC WONDER data in May 2024 [

9]. The dataset contains de-identified death certificate information only, so institutional review board approval was not necessary. We followed CDC WONDER Data-Use Agreement requirements and adhered to STROBE reporting standards throughout our analysis [

22].

2.2. Case Definition and Rationale

We used the MCOD query interface to select death certificates documenting malignant melanoma (ICD-10 C43.0–C43.9) and/or keratinocyte skin cancers (ICD-10 C44.0–C44.9) listed anywhere on the certificate. This dual approach captures total deaths from UV-linked skin cancer while maintaining consistency with national surveillance methods.

2.3. Study Population and Variables

NCHS coding systems [

23] allowed stratification by age (adults ≥65 years), sex, bridged race/ethnicity, Census regions, and county-level urban–rural status. For race/ethnicity, we classified deaths into four mutually exclusive groups: non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black or African American, NH Others (non-Hispanic Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and other/unknown), and Hispanic or Latino. The NH Others category combined Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, and other minority racial groups to improve rate stability for trend analysis. It should be noted that racial/ethnic misclassification on death certificates may affect accuracy, particularly for minority populations (with greater potential misclassification for American Indian/Alaska Native and Hispanic decedents).

Geographic analysis included the four U.S. Census regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) and county-level urban classifications. Urban–rural status was assigned using the 2013 NCHS six-level taxonomy, collapsed into metropolitan versus non-metropolitan categories. Counties that transitioned to urban status after 2013 retained their original classification, introducing potential timing-related bias addressed in the limitations. Urbanization analyses were limited to 1999–2020 due to data availability for the 2013 NCHS scheme.

CDC WONDER suppressed all cells with fewer than 10 deaths to protect confidentiality. Single-year bridged-race population estimates were used as denominators; intercensal estimates were applied for earlier years and postcensal estimates for 2021–2023.

2.4. Data Management and Quality Control

We exported comma-separated output files to Microsoft Excel 365 and performed several quality verification steps. Initially, we cross-checked county FIPS codes against their Census regions. We confirmed that death counts based on bridged-race categories matched available population figures and verified our annual totals against WONDER system displays. These validation steps revealed no discrepancies.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We calculated age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMR per 100,000) using the direct method with 2000 U.S. standard population weights [

25,

26]. NCHS recommendations guided our use of the γ-distribution approach for generating 95% confidence intervals [

27]. We employed Joinpoint Regression Program version 5.4.0 from the National Cancer Institute for trend analysis [

28]. Our analysis permitted up to four joinpoint, determined via Monte Carlo permutation testing with α = 0.05 [

29]. We assessed statistical significance through annual percent change calculations, with observed changes considered significant when confidence intervals excluded zero. Given the multiple comparisons across demographic subgroups, readers should interpret statistically significant results with appropriate caution.

3. Results

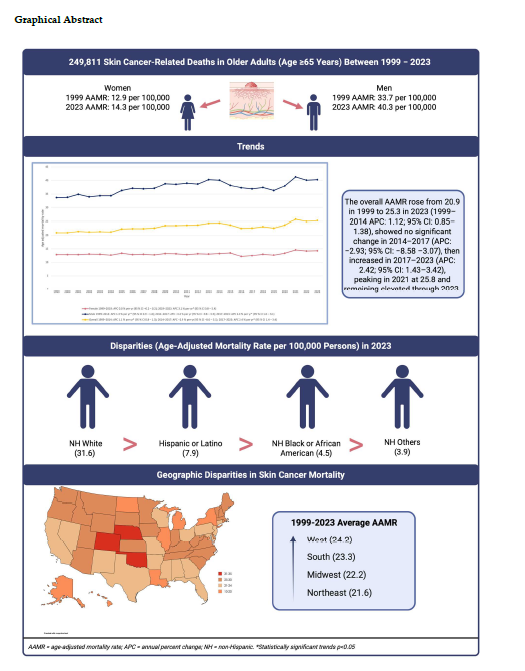

A total of 249,811 skin-cancer related deaths were recorded in the US between 1999 and 2023 among adults aged 65 and above.

3.1. Annual Trends for Skin Cancer-Related AAMR

According to joinpoint regression, the overall AAMR increased from 1999 to 2014 (APC: 1.12; 95% CI: 0.8–1.3), showed no significant change from 2014 to 2017 (APC: −2.9; 95% CI: −8.5–3.1), and increased again from 2017 to 2023 (APC: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.4–3.4). Year-specific AAMRs were 22.6 in 2019, 23.7 in 2020, and 25.8 in 2021 (series peak), remaining elevated through 2023. No new joinpoint appeared in 2020.

3.2. Skin Cancer-Related AAMR Stratified by Sex

Overall age-adjusted mortality rate for males was around three times higher than that of females (overall AAMR males: 37.4 vs females: 13.1). From 1999 to 2019, mortality among females showed no significant change (APC: 0.01, 95% CI: -0.2–0.2) after which it increased till 2023 (APC: 3.1, 95% CI: 0.8–5.4). For males, the trend demonstrated a steady rise, with rates highest in 2014 (APC: 1.3, 95% CI: 0.9–1.6), no significant change from 2014 to 2017 (APC: -3.4, 95% CI: -9.8–3.5) and an increase thereafter to the end of the study period (APC: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.0–3.1). The male-female AAMR gap persisted across all years.

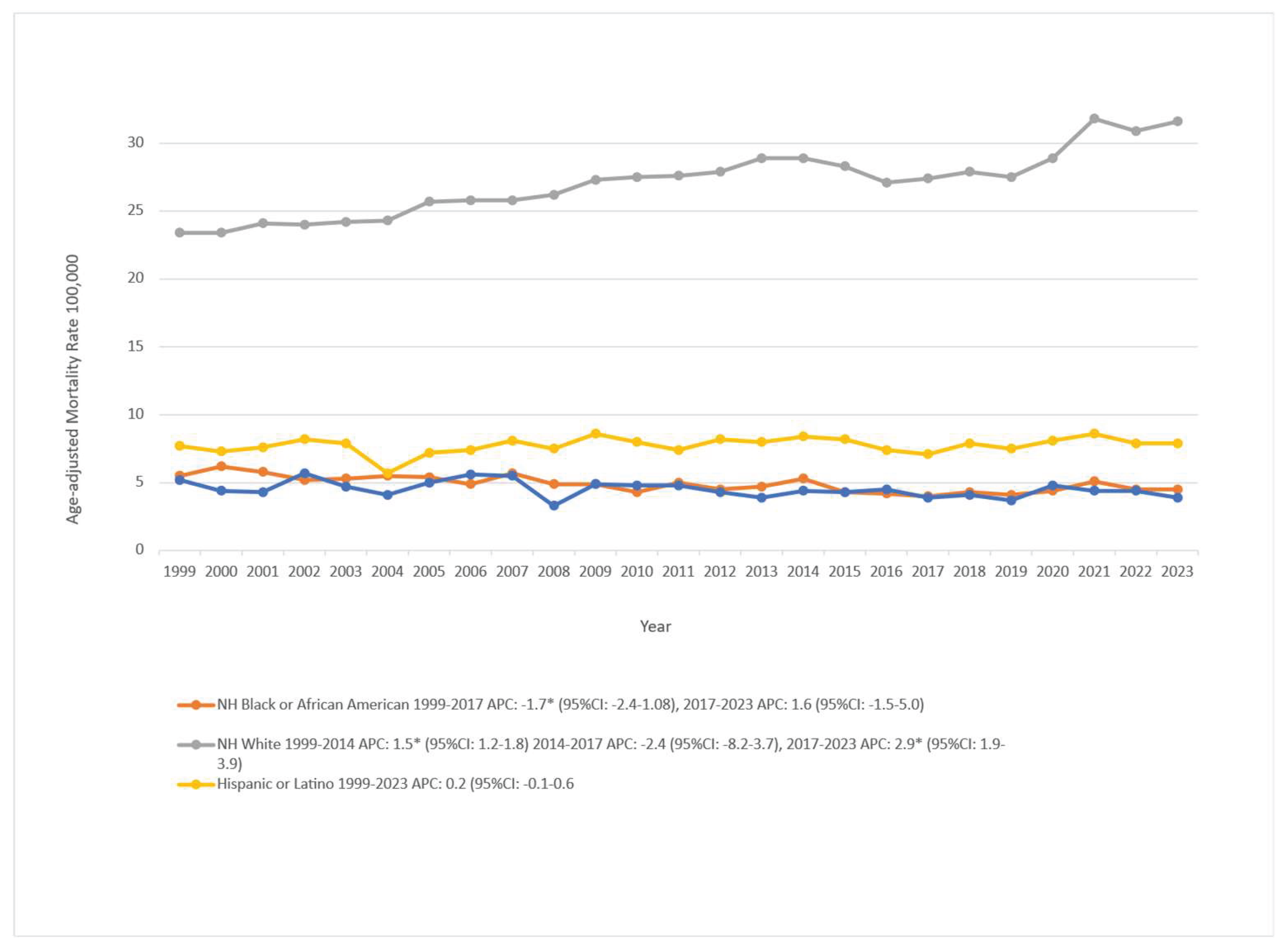

3.3. Skin Cancer-Related AAMR Stratified by Race/Ethnicity

Racial and ethnic disparities in skin cancer mortality were substantial over the study period. In the most recent year of data (2023), age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) were highest among non-Hispanic (NH) White individuals at 31.6 per 100,000, followed by Hispanic or Latino (7.9), NH Black or African American (4.5), and NH Others which includes Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, and other minority groups at 3.9 per 100,000.

Among NH White individuals, mortality increased from 1999 to 2014 (APC: 1.52; 95% CI: 1.24 to 1.80), showed no significant change in 2014–2017 (APC: −2.42; 95% CI: −8.22 to 3.74), and increased in 2017–2023 (APC: 2.94; 95% CI: 1.95 to 3.94). For NH Black or African American individuals, rates declined in 1999–2017 (APC: −1.79; 95% CI: −2.48 to −1.09) and showed no significant change in 2017–2023 (APC: 1.66; 95% CI: −1.59 to 5.01). Hispanic or Latino populations were stable across the entire period (APC: 0.27; 95% CI: −0.14 to 0.68). NH Others declined modestly overall (APC: −0.80; 95% CI: −1.43 to −0.16). These patterns are illustrated in

Figure 1 and detailed in Supplementary Table 2 and Table 5 (Figure S2). Rates for smaller racial groups should be interpreted with caution due to potential misclassification and sparse counts.

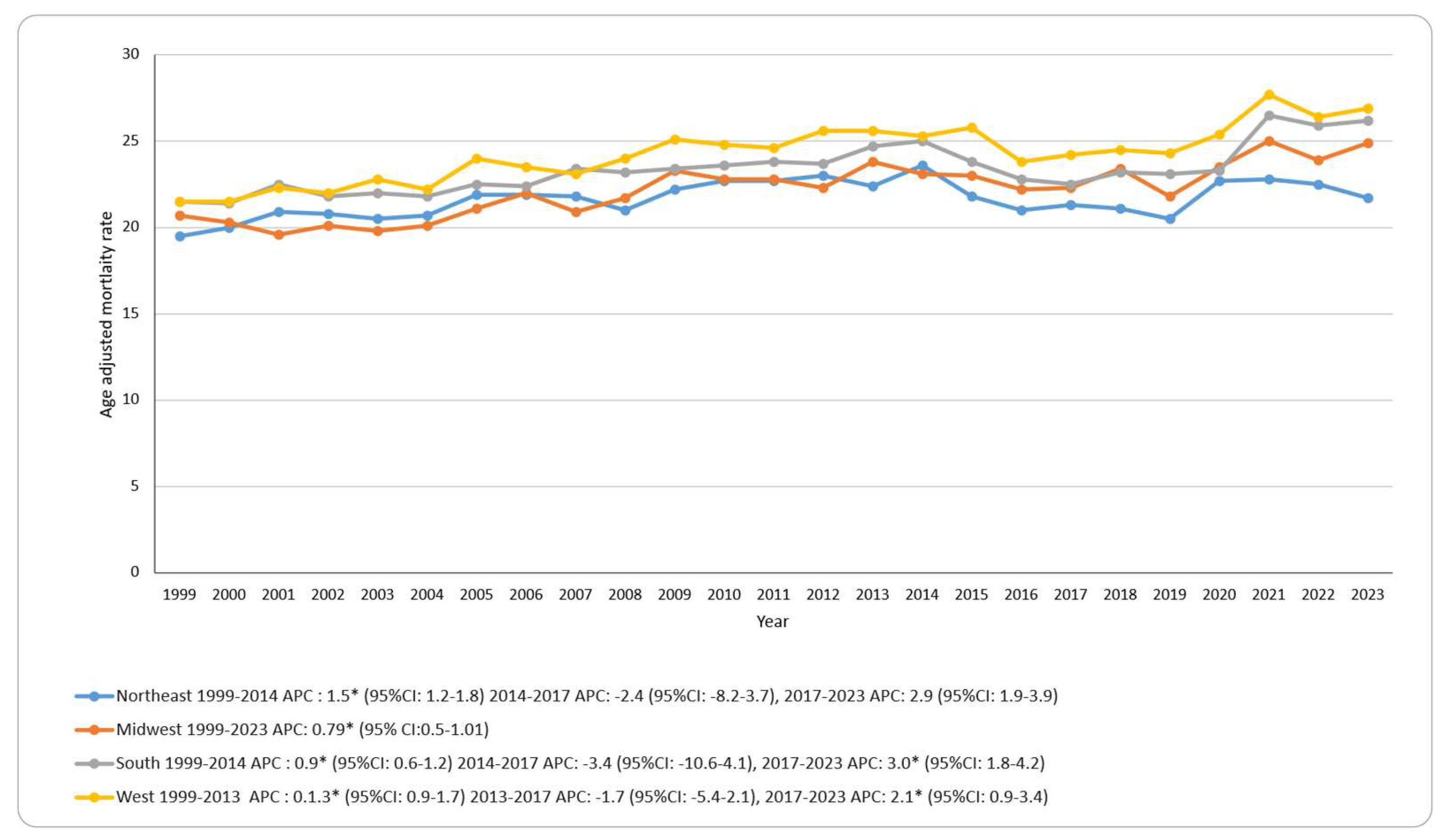

3.4. Skin Cancer-Related AAMR Stratified by Geographic Region

Mortality rates varied by region, with the West highest (overall AAMR: 24.2 per 100,000), followed by the South (23.3), Midwest (22.2), and Northeast (21.6). In terms of trends, the Midwest showed a continuous increase across 1999–2023 (APC: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.56–1.01). The Northeast, South, and West each increased in the early period (Northeast and South 1999–2014; West 1999–2013), showed no significant change in 2014–2017, and increased in 2017–2023 for the South and West, while the Northeast showed no significant change in 2017–2023. No region showed an additional joinpoint in 2020. See

Figure 2; Supplementary Tables S3 and S7; Supplementary Figure S3.

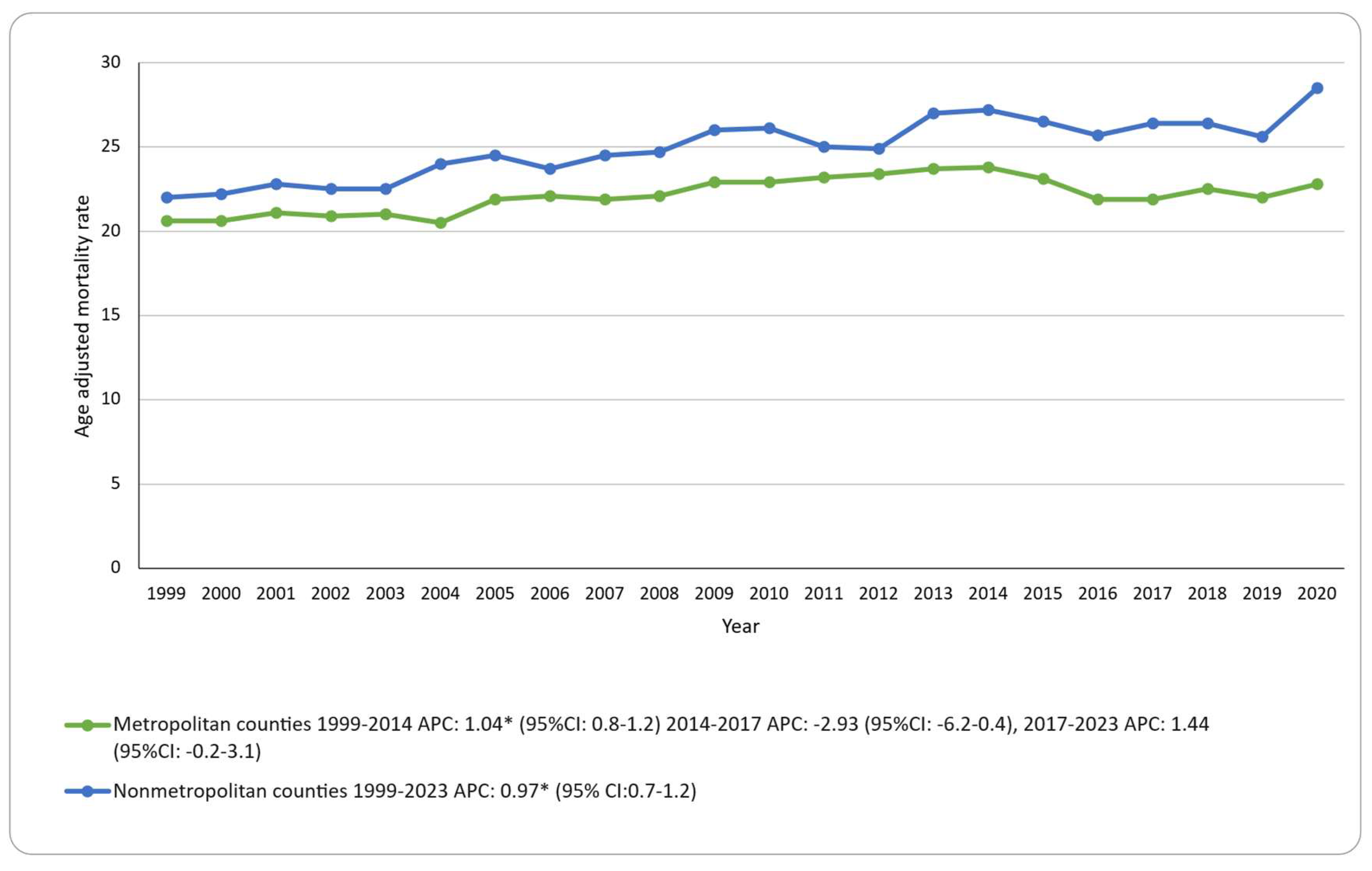

Urbanization (2013 scheme, 1999–2020): Nonmetropolitan counties had a higher AAMR than metropolitan counties (25.0 vs 22.2 per 100,000). Nonmetropolitan counties showed a steady increase (APC: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.72–1.2). For metropolitan counties, AAMR increased to 2014, showed no significant change from 2014 to 2017, and no significant change from 2017 to 2020 (APC: 1.44; 95% CI: −0.28 to 3.19). Because urbanization data are available only through 2020, trends are reported through 2020. The results are presented in

Figure 3; Supplementary Tables S8; Figure S4.

4. Discussion

Our research shows that skin-cancer mortality rates among Americans aged ≥65 have started rising again. The mortality rates showed a ~1% yearly increase from 1999 to 2014, followed by a temporary, non-significant change during 2014–2017 that coincided with early uptake of immune checkpoint inhibitors, before peaking in 2021 and remaining elevated through 2023 [

5]. Several high-income nations show similar patterns where incidence outpaces survival gains [

7]. Healthcare professionals should examine the underlying factors associated with this resurgence. Multiple elements may be contributing to this increase. The aging population experiences rising keratinocyte cancer rates [

8] and elderly patients face challenges with intensive systemic treatment due to frailty and prolonged UV exposure. Particularly concerning is the persistent rural–urban divide. The AAMR in rural counties exceeded that of urban areas by 12.6% (≈2.8 per 100,000) throughout 1999–2020. The persistent gap suggests access-to-care problems in rural regions because of distant dermatologists and specialist shortages [

30]. The enduring nature of this difference indicates that underserved areas require specific screening and early-treatment programs. For context only, we interpret joinpoint-derived segments as three descriptive eras; 1999–2014 increase; 2015–2017 temporary decline; 2017–2023 renewed increase, with no breakpoint in 2020 and no causal attribution implied.

4.1. Placing Our Findings in Broader Context

The mortality rates have increased significantly with substantial differences be tween male and female populations (37.4 vs 13.1 per 100,000) and between the Western and Northeastern regions (24.2 vs 21.6 per 100,000). Non-Hispanic Whites bear the highest burden of skin cancer deaths. When we compare our findings internationally, the United States ranks its senior mortality rates between Canada and Australia and New Zealand regarding melanoma-specific deaths [

31]. The late life death rates of Australian and New Zealand seniors remain elevated despite prevention efforts that have been implemented for years [

32]. However, international comparison is challenging because of different coding practices and healthcare access and population demographics across countries. In addition, most international figures are melanoma-specific; our outcome combines C43 and C44, so cross-country ranking should be interpreted cautiously. These sex and regional contrasts persisted across the study period.

4.2. Understanding Demographic and Geographic Disparities

The mortality burden among racial and ethnic groups remained uneven throughout the study period. Non-Hispanic (NH) White individuals experienced the highest mortality at 31.6 per 100,000 in 2023, followed by Hispanic or Latino (7.9 per 100,000), NH Black or African American (4.5 per 100,000), and NH Others, which includes Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, and other minority groups at 3.9 per 100,000. Rates are age-adjusted, so these differences are unlikely to reflect age structure alone. NH Others aggregates multiple groups to stabilize estimates; small counts and potential race/ethnicity misclassification widen uncertainty and warrant cautious interpretation. Trend analysis showed that NH White mortality rose in 1999–2014, dipped slightly in 2014–2017, and increased again from 2017 onward, reaching the highest recorded rate in 2023. NH Black rates declined steadily from 1999 to 2017 before leveling off, while Hispanic and NH Others groups remained relatively stable; NH Others had a modest but statistically significant long-term decline.

The differences reflect a combination of behavioral, structural, and healthcare access factors. The elevated mortality in NH White populations likely stems from cumulative lifetime UV exposure, high prevalence of fair skin phenotypes, and historically higher melanoma incidence. In Hispanic or Latino populations, outdoor occupational exposure, language barriers, and delays in seeking diagnostic care may contribute to intermediate mortality levels [

33]. The relatively lower but persistent mortality in NH Black or African American groups may be explained by lower melanoma incidence but greater late-stage diagnoses when lesions occur, compounded by limited access to specialized dermatologic care in some communities. The low rates among NH Others mask within-group variation; American Indian and Alaska Native adults, for example, often face substantial care shortages in tribal and rural areas [

34].

Geographic and structural factors amplify these disparities. Rural residents, regardless of race or ethnicity, travel longer distances for dermatology services, and in many areas, specialist shortages remain chronic. Broadband limitations further hinder the reach of teledermatology services, particularly in non-metropolitan counties [

30]. These are mortality patterns, not incidence or case-fatality; mechanisms may differ between melanoma and keratinocyte cancers, underscoring the need for cause-specific analyses in future work.

4.3. Year Specific Patterns, 2019–2023

The AAMR increased from 22.6 per 100,000 in 2019 to 25.8 in 2021 and remained elevated through 2023. Joinpoint analysis detected no new breakpoint in 2020, indicating that the upward trend was already underway before the pandemic. During this period, U.S. healthcare services experienced substantial disruption: initial lockdowns were associated with biopsy volumes dropping by up to 50% [

41], oncology capacity was redirected, potentially delaying checkpoint inhibitor treatment for some older adults [

42], and teledermatology expansion failed to reach many rural and low-income counties with higher baseline mortality [

30]. Outside the United States, a five-center cohort from Austria, Germany, and Italy reported thicker melanomas in 2021 compared with pre-pandemic lesions [

43], whereas a nationwide Dutch audit found little evidence of stage shift despite similar service disruptions [

44]. Linking U.S. registry staging data with claims-based treatment timelines will be important to clarify whether the post-2019 mortality increase reflects disease progression, diagnostic delays, or other mechanisms.

4.4. Implications for Practice and Policy

Research has consistently shown that men aged ≥65 along with several minority communities including American Indian and Alaska Native elders lack risk awareness [

34]. Pandemic-era reviews show that diagnostic delays are associated with thicker tumors and, ultimately, poorer outcomes [

42,

45]. This makes timely, culturally tailored messaging important. From a public health standpoint, multilingual community-based campaigns delivered through trusted channels such as Medicare newsletters, veterans

’ clinics, and county extension meetings may help address this awareness gap. Workforce shortages may respond to targeted incentives. The success of loan-forgiveness programs has led clinicians to practice in underserved areas in other medical specialties [

46]. A skin-cancer specific loan forgiveness option could be piloted in Western and Southern counties where mortality exceeds ~24 per 100,000. Mobile dermatology units using broadband teleconsultation services may help reduce the travel challenges that rural patients face. Implementation should include simple evaluation metrics (e.g., time to biopsy, time to excision, rural teledermatology uptake).

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

Our study brings several important strengths to the literature. The analysis of 25 years of death certificate data enabled us to generate reliable statistics for sex, race/ethnicity, region, and urbanicity. The long observation window provides broad temporal coverage across major changes in cancer care and service delivery. Our comparisons and trend detection were made robust through age standardization to the 2000 U.S. population and joinpoint regression.

However, we acknowledge several important limitations. The combination of melanoma (C43) and keratinocyte cancers (C44) into a single outcome likely obscures disease-specific patterns. This combination means that the survival of melanoma patients may be influenced by therapeutic progress, while the mortality of keratinocyte cancer patients may be more affected by delays in diagnosis. The rural–urban classifications were fixed at 2013 boundaries; by 2020, perhaps one-fifth of rural counties had transitioned to metropolitan, likely leading us to underestimate current disparities. Death certificates do not capture stage, treatment, or comorbidity information and can misclassify race/ethnicity, particularly for American Indian and Hispanic decedents, which may widen uncertainty around subgroup estimates. We did not apply multiple-comparison corrections in this descriptive analysis, which may have increased the risk of Type I error in subgroup analyses. These limitations may bias absolute rates downward, and compress observed gaps. Eras were not pre-specified; joinpoint segments were related to eras post hoc for context and should be interpreted descriptively, not causally.

4.6. Future Directions

Several research priorities emerge from our findings. The analysis of death certificates together with state cancer registry staging data and Medicare or commercial claims will help determine whether the deaths after 2017 show changes in keratinocyte cancer mortality, melanoma mortality, or both. Future work should report cause-specific trends (C43 vs C44) and incorporate standardized stage and treatment linkages. The analysis of county-level deprivation indices and dynamic rurality measures would help to explain how socioeconomic disparities may affect risk. Time-series models that consider autocorrelation might enhance breakpoint detection beyond what standard joinpoint methods offer. Predefined sensitivity analyses (e.g., alternative urbanicity definitions; exclusion of small-count strata) would strengthen robustness. Most importantly, there is a need for prospective cohort studies to monitor how delays in diagnosis during the pandemic era have affected staging and survival outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Skin-cancer mortality in Americans ≥65 remained elevated through 2023, peaking in 2021.While recent therapeutic advances have been developed, population-level evidence that immune-checkpoint inhibitors reduce mortality in this age group has not been definitively demonstrated. The factors underlying disproportionate impact on men, non-Hispanic White individuals, rural residents, and those living in Western states remain to be clarified. Based on our findings, a comprehensive approach may involve incorporating regular full-body skin checks into primary care, implementing same-day biopsy pathways, providing mobile and teledermatology services in underserved regions, and developing data systems that connect death certificates with registries and claims. Combining clinical initiatives with pragmatic public-health strategies and linked data systems may help reduce mortality in this growing population.

Author Contributions

MAM, EA and AK conceived this study. EA and SQ designed the study. AK abstracted the data and performed all statistical analyses. EA, SQ and AK generated the figures. EA, SQ, AK, and MAM drafted the manuscript and prepared successive revisions. AO supervised the project, provided critical reviews, and managed the administration. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The article processing charge was funded by College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as we used publicly available de-identified mortality data from the CDC WONDER database. No individual consent was required because the study used aggregate, deidentified data. The data were treated and analyzed in accordance with the CDC WONDER Data Use Agreement and analytic guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for maintaining the WONDER database and providing public access to vital statistics. The graphical abstract was created in BioRender. Atif, E. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/lw96c9i

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAMR |

Age-adjusted mortality rate |

| APC |

Annual percent change |

| CDC WONDER |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| ICD-10 |

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision |

| NCHS |

National Center for Health Statistics |

| UV |

Ultraviolet radiation |

References

- Housman TS, Feldman SR, Williford PM, Fleischer AB, Goldman ND, Acostamadiedo JM, et al. Skin cancer is among the most costly of all cancers to treat for the Medicare population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003, 48, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy GP, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR. Prevalence and Costs of Skin Cancer Treatment in the U.S., 2002−2006 and 2007−2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015, 48, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal P, Knabel P, Fleischer AB. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021, 85, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, Coldiron BM. Incidence Estimate of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer (Keratinocyte Carcinomas) in the US Population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier AJ, Nandwani SV, Watkins D, Fahoury AM, Campbell A, Craig DJ, et al. Patterns and trends in melanoma mortality in the United States, 1999–2020. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pinto G, Mignozzi S, La Vecchia C, Levi F, Negri E, Santucci C. Global trends in cutaneous malignant melanoma incidence and mortality. Melanoma Res. 2024, 34, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu W, Fang L, Ni R, Zhang H, Pan G. Changing trends in the disease burden of non-melanoma skin cancer globally from 1990 to 2019 and its predicted level in 25 years. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multiple Cause of Death Data on CDC WONDER [Internet]. [cited 2025 ]. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd. 29 June.

- Riew TR, Kim YS. Mutational Landscapes of Normal Skin and Their Potential Implications in the Development of Skin Cancer: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao J, Yuan Y, Wang X, He L, Li L. Impact of Immunosenescence on Immune-Related Adverse Events in Elderly Patients With Cancer. AGING Med [Internet]. 2025 Feb [cited 2025 ];8(1). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/agm2. 24 July 7000.

- Wojcik KY, Hawkins M, Anderson-Mellies A, Hall E, Wysong A, Milam J, et al. Melanoma survival by age group: Population-based disparities for adolescent and young adult patients by stage, tumor thickness, and insurance type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023, 88, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman CF, Wolchok JD. Checkpoint inhibition and melanoma: Considerations in treating the older adult. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017, 8, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloster HM, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006, 55, 741–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, Saraiya M, Huang Y, Wiggins C, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011, 65, S26.e1–S26.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao K, Feng H. Racial and Ethnic Healthcare Disparities in Skin Cancer in the United States: A Review of Existing Inequities, Contributing Factors, and Potential Solutions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2022, 15, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kooper-Johnson S, Kasthuri V, Homer A, Nguyen BM. Higher risk of melanoma-related deaths for patients residing in rural counties: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024, 90, 1257–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie C, Nahm WJ, Kearney CA, Zampella JG. Sun-protective behaviors and sunburn among US adults. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023, 315, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer [Internet]. Washington (DC): Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2014 [cited 2025 ]. (Reports of the Surgeon General). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 29 June 2471.

- CDC. Skin Cancer. 2024 [cited 2025 ]. Reducing Risk for Skin Cancer. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/skin-cancer/prevention/index. 24 July.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, et al. Behavioral Counseling to Prevent Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018, 319, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. The Lancet. 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram DD, Parker JD, Schenker N, Weed JA, Hamilton B, Arias E, et al. United States Census 2000 population with bridged race categories. Vital Health Stat 2. 2003 Sept;(135):1–55.

- Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. Vital Health Stat 2. 2014 Apr;(166):1–73.

- Anderson RN, Rosenberg HM. Age standardization of death rates: implementation of the year 2000 standard. Natl Vital Stat Rep Cent Dis Control Prev Natl Cent Health Stat Natl Vital Stat Syst. 1998, 47, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Age adjustment - Health, United States [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 ]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/sources-definitions/age-adjustment. 24 July.

- Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006, 15, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joinpoint Regression Program [Internet]. [cited 2025 ]. Available from: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/index. 29 June.

- Fay MP, Tiwari RC, Feuer EJ, Zou Z. Estimating Average Annual Percent Change for Disease Rates without Assuming Constant Change. Biometrics. 2006, 62, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shellenberger RA, Johnson TM, Fayyaz F, Swamy B, Albright J, Geller AC. Disparities in melanoma incidence and mortality in rural versus urban Michigan. Cancer Rep Hoboken NJ. 2023, 6, e1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cancer Statistics 2023 | Canadian Cancer Society [Internet]. [cited 2025 ]. Available from: https://cancer. 24 July 2023.

- Incidence and mortality | National Cancer Prevention Policy Skin Cancer Statistics and Issues | Cancer Council [Internet]. [cited 2025 ]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org. 24 July.

- Blumenthal LY, Arzeno J, Syder N, Rabi S, Huang M, Castellanos E, et al. Disparities in nonmelanoma skin cancer in Hispanic/Latino patients based on Mohs micrographic surgery defect size: A multicenter retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022, 86, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn LL, Pascual MG, Schmiege SJ, Novins DK, Manson SM. Dermatology Access and Needs of American Indian and Alaska Native People. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2023, 34, 1254–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy GP, Watson M, Seidenberg AB, Hartman AM, Holman DM, Perna F. Trends in indoor tanning and its association with sunburn among US adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017, 76, 1191–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilheimer LT, Klein RJ. Data and measurement issues in the analysis of health disparities. Health Serv Res. 2010, 45, 1489–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland S, Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Sparse data bias: a problem hiding in plain sight. BMJ. 2016, 352, i1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morenz AM, Wescott S, Mostaghimi A, Sequist TD, Tobey M, Lipsitz SR. Evaluation of barriers to telehealth programs and dermatological care for American Indian individuals in rural communities. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gone JP, Trimble JE. American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012, 8, 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espey DK, Jim MA, Richards TB, Begay C, Haverkamp D, Roberts D. Methods for improving the quality and completeness of mortality data for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava S, Negbenebor N, Sadoughifar R, Ahmad S, Kroumpouzos G. Global impact on dermatology practice due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Dermatol. 2021, 39, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini C, Caini S, Gaeta A, Lucantonio E, Mastrangelo M, Bruni M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Delay of Melanoma Diagnosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers. 2024, 16, 3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troesch A, Hoellwerth M, Forchhammer S, Del Regno L, Lodde G, Turko P, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis of cutaneous melanomas: A retrospective cohort study from five European skin cancer reference centres. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023, 37, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangers TE, Wakkee M, Kramer-Noels EC, Nijsten T, Louwman MWJ, Jaspars EH, et al. Limited impact of COVID -19-related diagnostic delay on cutaneous melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma tumour characteristics: a nationwide pathology registry analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2022, 187, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Calvillo P, Muñoz-Barba D, Ureña-Paniego C, Maul LV, Cerminara S, Kostner L, et al. Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Diagnosis of Melanoma and Keratinocyte Carcinomas: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024, 104, adv19460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bärnighausen T, Bloom DE. Financial incentives for return of service in underserved areas: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).