Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Background

Gap Analysis

Objectives and Review Questions

- Urban areas worldwide: Population.

- Exposure: The presence or implementation of Urban Green Infrastructure (UGI), including street trees, green roofs, wetlands, parks, and forests.

- Comparator: Urban environments that include alternative gray infrastructure options or have minimal or no urban green infrastructure (UGI).

- Result: Evaluated the operational efficacy, co-benefits, and environmental, social, and economic benefits.

- Synthesis Aggregate evidence regarding the spectrum of advantages and co-benefits provided by Urban Green Infrastructure (UGI), in accordance with the categories of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (provisioning, regulating, cultural, and sustaining).

- Identification of Deficits Identify thematic, methodological, and contextual deficiencies in current UGI research, with a particular emphasis on the integration of co-benefits, inadequately examined service categories, and practical practicality.

- Policy Relevance Convert the findings into practical insights for academics, urban planners, and policymakers, emphasizing evidence-based strategies for extending the implementation of UGI in a variety of climatic and governance contexts.

Methods

Protocol Registration

Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Urban areas in any geographic region or climatic zone.

- Intervention/Exposure: The presence or implementation of urban green infrastructure (UGI), which includes urban wetlands, street trees, vertical vegetation, green roofs, blue-green infrastructure, and urban agriculture.

- Comparator: Urban regions that lack urban green infrastructure (UGI), utilize alternative gray infrastructure, or exhibit multiple forms of UGI for comparative analysis.

- Results: Environmental, social, and economic advantages, including secondary benefits, that have been recorded and classified in accordance with the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment framework (provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting).

- Study Design: Empirical, peer-reviewed investigations that include observational, experimental, modeling, or mixed-methods research.

- Period of publication: January 2000 to December 2022.

- Language: English.

Search Strategy

Study Selection

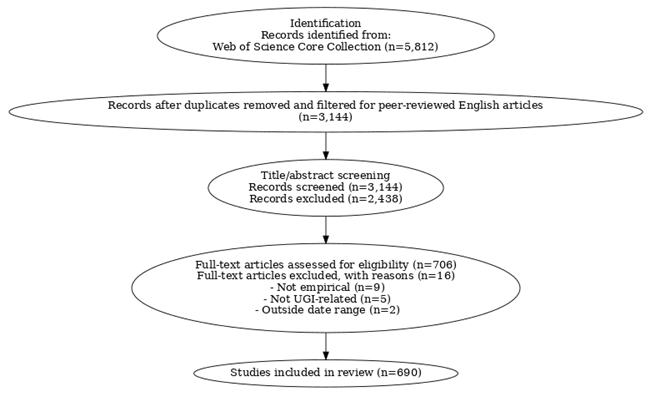

- Tier 1: Relevant titles and metadata were assessed, resulting in 3,144 articles.

- Tier 2: Titles and abstracts were assessed to eliminate irrelevant research, resulting in 706 publications.

- Tier 3: A comprehensive text evaluation was conducted to confirm eligibility, resulting in the inclusion of 690 studies.

Data Extraction

- The characteristics of UGI and the description of the intervention were documented by a systematic extraction framework.

- Documented advantages and ancillary benefits.

- Climate zone and geographic location.

- Research design and methods (hybrid approaches, surveys, remote sensing, modeling, or field measurement).

- Quantified indices, such as the mean radiant temperature, air temperature, land surface temperature, and physiological equivalent temperature.

- 6Solutions and methodologies for modeling (e.g., ENVI-met, WRF, CFD).

- Quantitative findings, when they are available.

Quality Assessment

Statistical Methodology

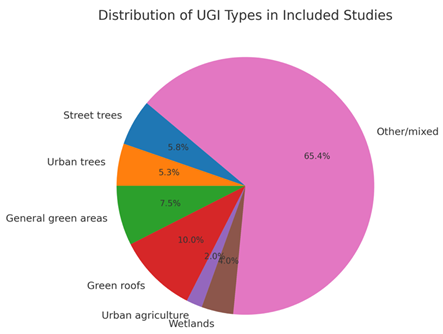

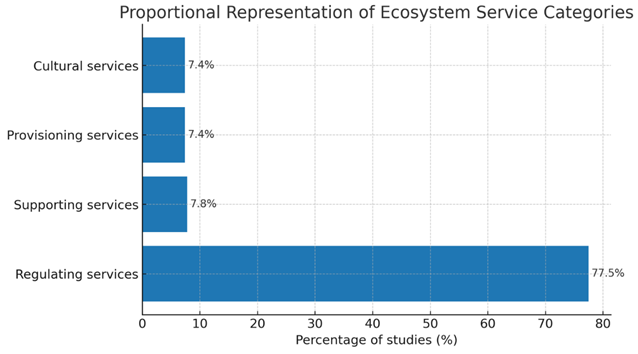

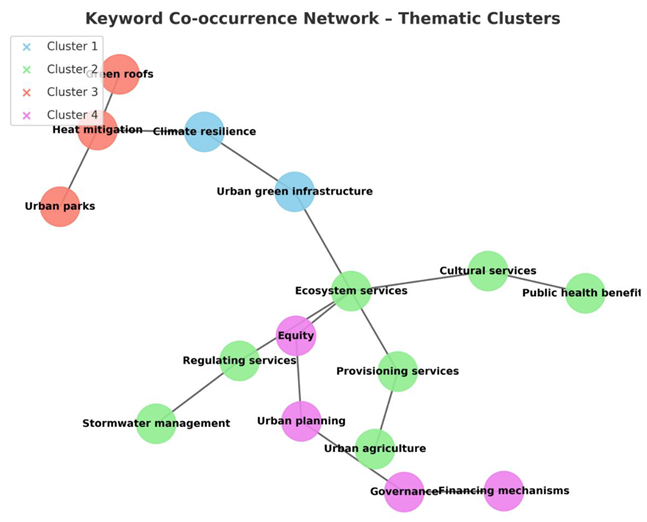

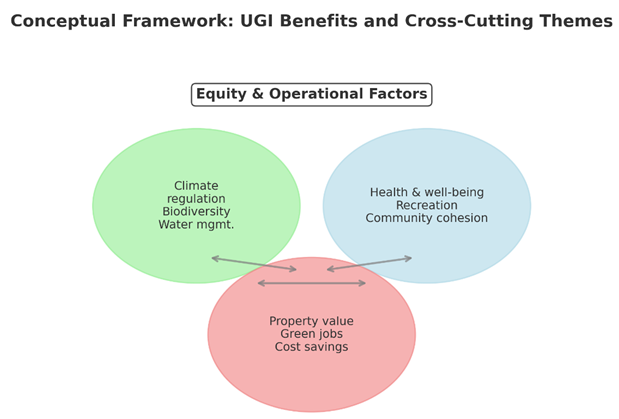

- Bibliometric Data Theme groupings of interest have been identified through keyword co-occurrence mapping, which evaluated phrase frequency and connection strength. Through treemap analysis, the proportional representation of ecosystem service categories was demonstrated, with regulatory services accounting for 77.5% of studies, supporting services for 7.8%, provisioning services for 7.4%, and cultural services for 7.4%.

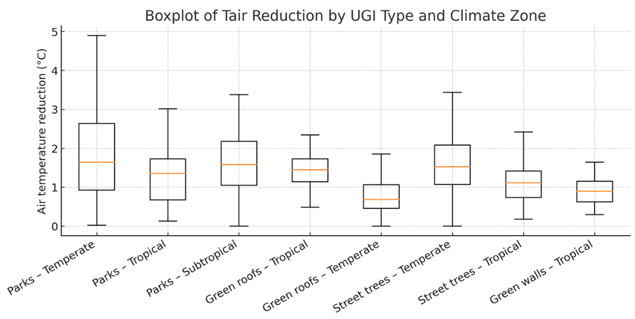

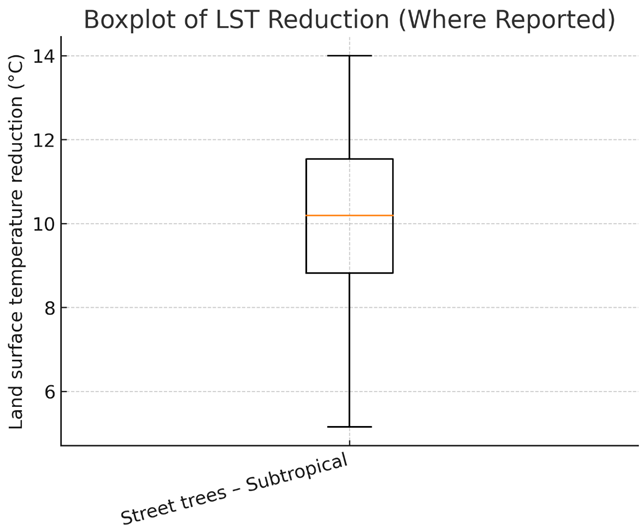

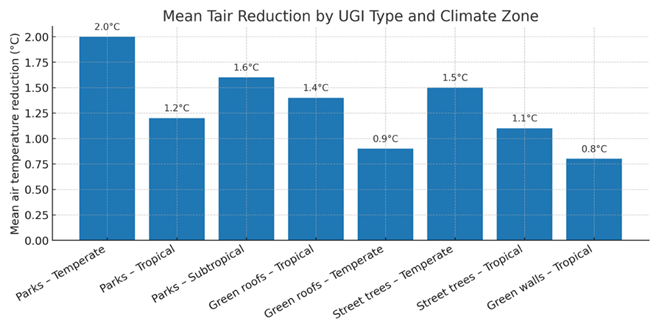

- Analysis of Climate-Related Data for Theme 2, quantitative decreases in air temperature (Tair), land surface temperature (LST), and thermal comfort indices (PET, PMV, UTCI) were assessed in research that examined the impacts of UGI on heat mitigation. The data were categorized by climatic zone, and the average reductions and ranges were calculated for each UGI type. The statistical overview comprised solely studies that produced quantifiable results, which accounted for 87% of heat-related cases. In lieu of conducting a meta-analysis, data were compared by climatic zone and intervention type. This was necessary due to the variability in research designs and models.

Data Synthesis

- Quantitative/Bibliometric Analysis Mapping the distribution of research by theme grouping, UGI type, and geographic location.

- Thematic and Narrative Synthesis Detailing advantages, ancillary benefits, methodological trends, and study deficiencies, data is organized into six designated topics.

| Database | Years Covered | Search Date | Search Query | Filters Applied | Number of Records Retrieved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Web of Science Core Collection (SCI-E, SSCI) | 2000–2022 | January 15, 2023 | (city OR urban OR metropolitan) AND ("green infrastructure" OR "nature-based solutions" OR "ecosystem-based adaptation" OR "blue–green infrastructure") AND (service OR impact OR climate OR "air quality" OR social OR economic OR water) | Peer-reviewed journal articles, English language | 5812 |

Results

Study Selection

| Criterion | Studies Meeting Criterion (%) |

|---|---|

| Clear description of UGI intervention | 92.5 |

| Appropriate study design for research question | 88.1 |

| Transparent statistical reporting | 74.6 |

| Use of empirical field data | 63.2 |

| Inclusion of co-benefits analysis | 17.7 |

| Consideration of equity/distributional impacts | 12.0 |

Study Characteristics

| Author/Year | Country/Region | Climate Zone | UGI Type | Study Design/Method | Key Outcomes/Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capotorti et al., 2019 | Italy (Europe) | Temperate | Urban parks, biodiversity corridors | Field measurement, GIS mapping | Air quality enhancement (NO₂, CO₂, SO₂ reduction), biodiversity habitat provision |

| Säumel et al., 2019 | Germany (Europe) | Temperate | Rooftop gardens, urban agriculture | Field measurement, surveys | Food production, community engagement, microclimate regulation |

| Threlfall et al., 2017 | Australia (Oceania) | Temperate | Urban parks, street trees | Field observation, biodiversity surveys | Habitat provision for urban biodiversity, pollinator abundance |

| Herath et al., 2023 | Sri Lanka (Asia) | Tropical | Green roofs, green walls | Modeling (ENVI-met), field measurement | Reduction in air temperature by 1.4°C, improved thermal comfort (PET index) |

| Meili et al., 2021 | Switzerland (Europe) | Temperate | Urban parks, street trees | Field measurement, microclimate modeling | Impact of tree canopy density on microclimate regulation |

Thematic Synthesis of Results

Agreements and Disagreements

Discussion

Summary of Main Findings

| UGI Type | Regulating services | Provisioning services | Cultural services | Supporting services | % of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street trees | ✔ (Heat mitigation, air quality) | ✖ | ✔ (Aesthetics, recreation) | ✔ (Biodiversity habitat) | 5.8 |

| Urban trees | ✔ (Heat mitigation, carbon storage) | ✖ | ✔ (Well-being, recreation) | ✔ (Biodiversity) | 5.3 |

| General green areas | ✔ (Stormwater, cooling) | ✖ | ✔ (Recreation, mental health) | ✔ | 7.5 |

| Green roofs | ✔ (Cooling, runoff reduction) | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ (Pollinator habitat) | 10.0 |

| Urban agriculture | ✔ (Microclimate regulation) | ✔ (Food production) | ✔ (Community engagement) | ✔ | 2.0 |

| Wetlands | ✔ (Flood control, water purification) | ✔ (Water supply) | ✔ (Recreation) | ✔ (Habitat) | 4.0 |

| Other/mixed | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 65.4 |

Comparison with Existing Literature

Strengths and Limitations of the Evidence Base

Strengths and Limitations of This Review

Implications for Practice, Research, and Policy

Unanswered Questions and Research Gaps

Controversies and Ongoing Debates

Conclusion

Key Messages

Recommendations

Future Research Directions

- Integration of Co-Benefits Improving research that simultaneously assesses numerous benefits, identifying synergies and trade-offs to inform multi-objective urban planning.

- Modeling of Climate Scenarios Evaluating the efficacy of UGI in the context of potential climatic scenarios to ensure that it can overcome the escalating heatwaves and severe precipitation events (Patricola & Wehner, 2018).

- Operational Feasibility and Cost-Benefit Analysis – Evaluating the life-cycle costs and maintenance requirements in conjunction with the advantages to inform investment decisions.

- Geographic Areas with Inadequate Representation Conducting context-specific research in Africa, South America, and low- to middle-income regions to improve the global relevance of UGI findings (Bai, 2018).

- Risk Assessment and Adverse Effects Mitigating potential disadvantages, such as the establishment of insect habitats, allergen generation, and unforeseen socio-economic effects like gentrification (Lyytimäki et al., 2008).

References

- Abhijith KV, Kumar P, Gallagher J, McNabola A, Baldauf R, Pilla F, Broderick B, Di Sabatino S, Pulvirenti B (2017) Air pollution abatement performances of green infrastructure in open road and built-up street canyon environments a review. Atmos Environ 162:71–86. [CrossRef]

- ADB. (2015). Water-Related Disasters and Disaster Risk Management in the People’s Republic of China (ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK (ed.)). Asian Development Bank, 6 ADB Avenue, Man- daluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines. www.adb.org.

- Albers RAW, Bosch PR, Blocken B, van den Dobbelsteen AAJF, van Hove LWA, Spit TJM, van de Ven F, van Hooff T, Rovers V (2015) Overview of challenges and achievements in the climate adaptation of cities and in the Climate Proof Cities program. Buildi Environ 83(December 2014):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Alcamo J, Ash NJ, Butler CD, Callicott JB, Capistrano D, Carpenter SR, Castilla JC, Chambers R, Chopra K, Cropper A, Daily GC, Dasgupta P, de Groot R, Hamilton T, Gadgil AKDM, Hamilton K (2005) Ecosystems and human well-being: a framework for assessment. Millenn Ecosyst Assess. [CrossRef]

- Alves A, Gersonius B, Kapelan Z, Vojinovic Z, Sanchez A (2019) Assessing the Co-Benefits of green-blue-grey infrastructure for sustainable urban flood risk management. J Environ Manag 239(February):244–254. [CrossRef]

- Amorim JH, Engardt M, Johansson C, Ribeiro I, Sannebro M (2021) Regulating and cultural ecosystem services of urban green infrastructure in the nordic countries: a systematic review. Int J.

- Environ Res Public Health 18(3):1–19. [CrossRef]

- Anderson V, Gough WA (2021) Harnessing the four horsemen of cli- mate change: a framework for deep resilience, decarbonization, and planetary health in Ontario Canada. Sustainability (switzer- land) 13(1):1–19. [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski I, Connolly JJT, Cole H, Garcia-Lamarca M, Triguero- Mas M, Baró F, Martin N, Conesa D, Shokry G, del Pulgar CP, Ramos LA, Matheney A, Gallez E, Oscilowicz E, Máñez JL, Sarzo B, Beltrán MA, Minaya JM (2022) Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nat Commun 13(1):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ariluoma M, Ottelin J, Hautamäki R, Tuhkanen EM, Mänttäri M (2021) Carbon sequestration and storage potential of urban green in residential yards: a case study from Helsinki. Urban for Urban Green. [CrossRef]

- Arnfield AJ (2003) Two decades of urban climate research: a review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island. Int J Climatol 23(1):1–26. [CrossRef]

- Astell-Burt T, Feng X (2019) Association of urban green space with mental health and general health among adults in Australia. JAMA Netw Open 2(7):1–22. [CrossRef]

- Azmy MM, Hosaka T, Numata S (2016) Responses of four hornet spe- cies to levels of urban greenness in Nagoya city, Japan: implica- tions for ecosystem disservices of urban green spaces. Urban for Urban Green 18:117–125. [CrossRef]

- Bai X (2018) Advance the ecosystem approach in cities. Nature 559(7712):7–7. [CrossRef]

- Bai X, McPhearson T, Cleugh H, Nagendra H, Tong X, Zhu T, Zhu YG (2017) Linking urbanization and the environment: conceptual and empirical advances. Annu Rev Environ Resour 42:215–240. [CrossRef]

- Bai X, Dawson RJ, Ürge-Vorsatz D, Delgado GC, Barau AS, Dhakal S, Dodman D, Leonardsen L, Masson-Delmotte V, Roberts D, Schultz S (2018) Six research priorities for cities. Nature 555:23–25.

- Bakhshipour AE, Dittmer U, Haghighi A, Nowak W (2019) Hybrid green-blue-gray decentralized urban drainage systems design, a simulation-optimization framework. J Environ Manag 249(August):109364. [CrossRef]

- Barcelona City Council (2015) Guide to living terrace roofs and green roofs (E. Contreras & I. Castillo (eds.)). Area of Urban Ecology. Barcelona City Council. Available online: https://bcnroc.ajuntament.barcelona.cat/jspui/handle/11703/98795.

- Baró F, Bugter R, Gómez-Baggethun E, Hauck J, Kopperoinen L, Liquete C, Potschin M (2015) Conceptual approaches to Green Infrastructure. In: Potschin M, Jax K (eds) OpenNESS Ecosys- tem Service Reference Book. www.openness-project.eu/library/reference-book.

- Battisti L, Pille L, Wachtel T, Larcher F, Säumel I (2019) Residential greenery: state of the art and health-related ecosystem services and disservices in the city of Berlin. Sustainability (switzerland) 11(6):1–20. [CrossRef]

- Berdejo-Espinola V, Suárez-Castro AF, Amano T, Fielding KS, Oh RRY, Fuller RA (2021) Urban green space use during a time of stress: a case study during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brisbane Australia. People Nat 3(3):597–609. [CrossRef]

- Bherwani H, Singh A, Kumar R (2020) Assessment methods of urban microclimate and its parameters: a critical review to take the research from lab to land. Urban Clim 34(August):100690. [CrossRef]

- Bowler DE, Buyung-Ali L, Knight TM, Pullin AS (2010) Urban green- ing to cool towns and cities: a systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landsc Urban Plan 97(3):147–155. [CrossRef]

- Bröde P, Fiala D, Błażejczyk K, Holmér I, Jendritzky G, Kampmann B, Tinz B, Havenith G (2012) Deriving the operational procedure for the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). Int J Biomete- orol 56(3):481–494. [CrossRef]

- Bruse M, Fleer H (1998) Simulating surface-plant-air interactions inside urban environments with a three dimensional numerical model. Environ Model Softw 13(3–4):373–384. [CrossRef]

- Cabana D, Ryfield F, Crowe TP, Brannigan J (2020) Evaluating and communicating cultural ecosystem services. Ecosyst Serv 42(February):101085. [CrossRef]

- Cai Y, Chen Y, Tong C (2019) Spatiotemporal evolution of urban green space and its impact on the urban thermal environment based on remote sensing data: a case study of Fuzhou City China. Urban for Urban Green 41(February):333–343. [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Argelich A, Benetti S, Anguelovski I, Connolly JJT, Lange- meyer J, Baró F (2021) Tracing and building up environmental justice considerations in the urban ecosystem service literature: a systematic review. Landsc Urban Plan. [CrossRef]

- Capotorti G, Alós Ortí MM, Copiz R, Fusaro L, Mollo B, Salvatori E, Zavattero L (2019) Biodiversity and ecosystem services in urban green infrastructure planning: a case study from the metropoli- tan area of Rome (Italy). Urban for Urban Green 37(November 2017):87–96. [CrossRef]

- Cavadini GB, Cook LM (2021) Green and cool roof choices integrated into rooftop solar energy modelling. Appl Energy 296(Febru- ary):117082. [CrossRef]

- Chan FKS, Griffiths JA, Higgitt D, Xu S, Zhu F, Tang YT, Xu Y, Thorne CR (2018) “Sponge City” in China—a breakthrough of planning and flood risk management in the urban context. Land Use Policy 76(May):772–778. [CrossRef]

- Chen WY (2015) The role of urban green infrastructure in offsetting carbon emissions in 35 major Chinese cities: a nationwide esti- mate. Cities 44:112–120. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Liu Y, Gitau MW, Engel BA, Flanagan DC, Harbor JM (2019) Evaluation of the effectiveness of green infrastructure on hydrol- ogy and water quality in a combined sewer overflow community. Sci Total Environ 665:69–79. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y,GeY,YangG,WuZ,DuY,MaoF,LiuS,XuR,QuZ,Xu B, Chang J (2022) Inequalities of urban green space area and ecosystem services along urban center-edge gradients. Landsc Urban Plan 217(October):104266. [CrossRef]

- Cheshmehzangi A, Butters C, Xie L, Dawodu A (2021) Green infra- structures for urban sustainability: Issues, implications, and solutions for underdeveloped areas. Urban for Urban Green 59(December):127028. [CrossRef]

- Chou RJ, Wu CT, Huang FT (2017) Fostering multi-functional urban agriculture: experiences from the champions in a revitalized farm pond community in Taoyuan Taiwan. Sustainability (switzer- land). [CrossRef]

- City of Melbourne (2017) Green our city, Strategic action plan 2017– 2021. https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/sitecollectiondocume nts/green-our-city-action-plan-2018.pdf.

- Climate ADAPT (2023) Urban green infrastructure planning and nature-based solutions. DG CLIMA Project Adaptation Strate- gies of European Cities (EU Cities Adapt). http://www.environmentalevidence.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Review-guidelines-version-4.2-final.pdf.

- Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (2013) Guidelines for Sys- tematic Reviews in Environmental Management. In Version 4.2 (Issue March). http://www.environmentalevidence.org/wp-conte nt/uploads/2014/06/Review-guidelines-version-4.2-final.pdf.

- Combrinck Z, Cilliers EJ, Lategan L, Cilliers S (2020) Revisiting the proximity principle with stakeholder input: Investigating prop- erty values and distance to urban green space in potchefstroom. Land. [CrossRef]

- Costanza R, de Groot R, Braat L, Kubiszewski I, Fioramonti L, Sut- ton P, Farber S, Grasso M (2017) Twenty years of ecosystem services: how far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst Serv 28:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Garcia GS, Sachet E, Blundo-Canto G, Vanegas M, Quintero M (2017) To what extent have the links between ecosystem ser- vices and human well-being been researched in Africa, Asia, and Latin America? Ecosyst Serv 25:201–212. [CrossRef]

- Culligan PJ (2019) Green infrastructure and urban sustainability: a discussion of recent advances and future challenges based on multiyear observations in New York City. Sci Technol Built Environ. [CrossRef]

- Dai X, Wang L, Tao M, Huang C, Sun J, Wang S (2021) Assessing the ecological balance between supply and demand of blue- green infrastructure. J Environ Manag 288(March):112454. [CrossRef]

- DasGupta R, Hashimoto S, Gundimeda H (2019) Biodiversity/ecosystem services scenario exercises from the Asia–Pacific: typology, archetypes and implications for sustainable develop- ment goals (SDGs). Sustain Sci 14(1):241–257. [CrossRef]

- De Sousa MRC, Montalto FA, Spatari S (2012) Using life cycle assessment to evaluate green and grey combined sewer over- flow control strategies. J Ind Ecol 16(6):901–913. [CrossRef]

- Derkzen ML, Teeffelen AJA, van PH Verburg, (2017) Green infra- structure for urban climate adaptation: How do residents’ views on climate impacts and green infrastructure shape adaptation preferences? Landsc Urban Plan 157(106):130. [CrossRef]

- Di Leo N, Escobedo FJ, Dubbeling M (2016) The role of urban green infrastructure in mitigating land surface temperature in Bobo- Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Environ Dev Sustain 18(2):373–392. [CrossRef]

- Di Marino M, Tiitu M, Lapintie K, Viinikka A, Kopperoinen L (2019) Integrating green infrastructure and ecosystem services in land use planning. Results from two Finnish case studies. Land Use Policy 82(January):643–656. [CrossRef]

- Douglas O, Russell P, Scott M (2019) Positive perceptions of green and open space as predictors of neighbourhood quality of life: implications for urban planning across the city region. J Envi- ron Planning Manag 62(4):626–646. [CrossRef]

- DTI (2003) Our energy future—creating a low carbon economy. In Energy White Pape. Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov. uk/+/http:/www.berr.gov.uk/files/file10719.pdf.

- Duan J, Wang Y, Fan C, Xia B, de Groot R (2018) Perception of urban environmental risks and the effects of urban green infra- structures (UGIs) on human well-being in four public green spaces of Guangzhou China. Environ Manag 62(3):500–517. [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel R, Loconsole A (2015) Green infrastructure as an adap- tation approach to tackling urban overheating in the Glasgow Clyde Valley Region, UK. Landsc Urban Plan 138:71–86. [CrossRef]

- ENVI-met GmbH (2022) ENVI-met Technical Model Webpage. Available online: https://envi-met.info/doku.php?id=intro:modelconept#atmos pheric_model.

- Escobedo FJ, Giannico V, Jim CY, Sanesi G, Lafortezza R (2019) Urban forests, ecosystem services, green infrastructure and nature-based solutions: nexus or evolving metaphors? Urban for Urban Green 37(February):3–12. [CrossRef]

- European Commission (2013) The forms and functions of green infrastructure. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosy stems/benefits/index_en.htm.

- Fahmy M, Ibrahim Y, Hanafi E, Barakat M (2018) Would LEED-UHI greenery and high albedo strategies mitigate climate change at neighborhood scale in Cairo, Egypt? Build Simul 11(6):1273– 1288. [CrossRef]

- Fattorini S, Galassi DMP (2016) Role of urban green spaces for saproxylic beetle conservation: a case study of tenebrionids in Rome Italy. J Insect Conserv 20(4):737–745. [CrossRef]

- Fei W, Jin Z, Ye J, Divigalpitiya P, Sakai T, Wang C (2019) Disas- ter consequence mitigation and evaluation of roadside green spaces in nanjing. J Environ Eng Landsc Manag 27(1):49–63. [CrossRef]

- Feng S, Hou W, Chang J (2019a) Changing coal mining brownfields into green infrastructure based on ecological potential assess- ment in Xuzhou Eastern China. Sustainability (switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Feng S, Chen L, Sun R, Feng Z, Li J, Khan MS, Jing Y (2019b) The distribution and accessibility of urban parks in Beijing China: Implications of social equity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Flato G, Marotzke J, Abiodun B, Braconnot P, Chou SC, Collins W, Cox P, Driouech F, Emori S, Eyring V, Forest C, Gleck- ler P, Guilyardi E, Jakob CVK, Reason C, Rummukainen M (2013) Evaluation of climate models. In Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner GK, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM (eds) Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Vol. 9781107057). Cambridge Univer- sity Press, Cambridge, pp. 741–866. [CrossRef]

- Fowdar HS, Hatt BE, Breen P, Cook PLM, Deletic A (2017) Design- ing living walls for greywater treatment. Water Res 110:218– 232. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes S, Tongson E, Viejo CG (2021) Urban green infrastructure monitoring using remote sensing from integrated visible and thermal infrared cameras mounted on a moving vehicle. Sen- sors (switzerland) 21(1):1–16. [CrossRef]

- Fung CKW, Jim CY (2019) Microclimatic resilience of subtropical woodlands and urban-forest benefits. Urban for Urban Green 42(July):100–112. [CrossRef]

- Furberg D, Ban Y, Mörtberg U (2020) Monitoring urban green infra- structure changes and impact on habitat connectivity using high- resolution satellite data. Remote Sens. [CrossRef]

- Gashu K, Gebre-Egziabher T (2019) Public assessment of green infrastructure benefits and associated influencing factors in two Ethiopian cities: Bahir Dar and Hawassa. BMC Ecol 19(1):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Geary RS, Wheeler B, Lovell R, Jepson R, Hunter R, Rodgers S (2021) A call to action: improving urban green spaces to reduce health inequalities exacerbated by COVID-19. Prev Med 145(Janu- ary):106425. [CrossRef]

- Gelan E, Girma Y (2021) Sustainable urban green infrastructure devel- opment and management system in rapidly urbanized cities of Ethiopia. Technologies 9(3):66. [CrossRef]

- Ghazalli AJ, Brack C, Bai X, Said I (2018) Alterations in use of space, air quality, temperature and humidity by the presence of vertical greenery system in a building corridor. Urban for Urban Green 32(April):177–184. [CrossRef]

- Ghazalli AJ, Brack C, Bai X, Said I (2019) Physical and non-physical benefits of vertical greenery systems: a review. J Urban Technol. [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani Z, Sposito V, Faggian R (2017) A comprehensive review of blue-green infrastructure concepts. Int J Environ Sustain. [CrossRef]

- Giedych R, Maksymiuk G (2017) Specific features of parks and their impact on regulation and cultural ecosystem services provision in Warsaw Poland. Sustainability (switzerland) 9(5):1–18. [CrossRef]

- Giyasova I (2021) Factors affecting microclimatic conditions in urban environment. E3S Web of Conf 244:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Gopal D, von der Lippe M, Kowarik I (2019) Sacred sites, biodiver- sity and urbanization in an Indian megacity. Urban Ecosyst 22(1):161–172. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Luhan, G. A., & Caffey, S. M. (2025). Analysis of design algorithms and fabrication of a graph-based double-curvature structure with planar hexagonal panels. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Caffey, S. M., & Luhan, G. A. (2024). Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods: A comprehensive survey. Athens Journal of Sciences, 11(2), 1–29. https://www.athensjournals.gr/sciences/2024-6026-AJS-Gorjian-02.pdf Gorjian, M., & Quek, F. (2024). Enhancing consistency in sensible mixed reality systems: A calibration approach integrating haptic and tracking systems [Preprint]. EasyChair. Available online: https://easychair.org/publications/preprint/KVSZ.

- Gorjian, M. (2024). A deep learning-based methodology to re-construct optimized re-structured mesh from architectural presentations (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University). Texas A&M University. Available online: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/items/0efc414a-f1a9-4ec3-bd19-f99d2a6e3392.

- Gorjian, M. Caffey, S. M., & Luhan, G. A. (2025). Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods: A comprehensive survey. Athens Journal of Sciences, 12, 1–29.

- Raina, A. S. Mone, V., Gorjian, M., Quek, F., Sueda, S., & Krishnamurthy, V. R. (2024). Blended physical-digital kinesthetic feedback for mixed reality-based conceptual design-in-context. In Proceedings of the 50th Graphics Interface Conference (Article 6, pp. 1–16). ACM. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2024). A deep learning-based methodology to re-construct optimized re-structured mesh from architectural presentations (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University). Texas A&M University. Available online: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/items/0efc414a-f1a9-4ec3-bd19-f99d2a6e3392.

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Advances and challenges in GIS-based assessment of urban green infrastructure: A systematic review (2020–2024) [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Analyzing the relationship between urban greening and gentrification: Empirical findings from Denver, Colorado [Working paper]. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). From deductive models to data-driven urban analytics: A critical review of statistical methodologies, big data, and network science in urban studies [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). GIS-based assessment of urban green infrastructure: A systematic review of advances, gaps, and interdisciplinary integration (2020–2024) [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Green gentrification and community health in urban landscape: A scoping review of urban greening’s social impacts [Preprint, Version 1]. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Green schoolyard investments and urban equity: A systematic review of economic and social impacts using spatial-statistical methods [Preprint]. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Green schoolyard investments influence local-level economic and equity outcomes through spatial-statistical modeling and geospatial analysis in urban contexts [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Greening schoolyards and the spatial distribution of property values in Denver, Colorado [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Greening schoolyards and urban property values: A systematic review of geospatial and statistical evidence [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Integrating machine learning and hedonic regression for housing price prediction: A systematic international review of model performance and interpretability [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Methodological advances and gaps in urban green space and schoolyard greening research: A critical review [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Quantifying gentrification: A critical review of definitions, methods, and measurement in urban studies [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Schoolyard greening, child health, and neighborhood change [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Spatial economics: Quantitative models, statistical methods, and policy applications in urban and regional systems [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Statistical methodologies for urban morphology indicators: A comprehensive review of quantitative approaches to sustainable urban form [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Statistical perspectives on urban inequality: A systematic review of GIS-based methodologies and applications [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). The impact of greening schoolyards on residential property values [Working paper]. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). The impact of greening schoolyards on surrounding residential property values: A systematic review[Preprint, Version 1]. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Urban schoolyard greening: A systematic review of child health and neighborhood change [Preprint]. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Grard BJP, Chenu C, Manouchehri N, Houot S, Frascaria-Lacoste N, Aubry C (2018) Rooftop farming on urban waste provides many ecosystem services. Agron Sustain Dev. [CrossRef]

- Green D, O’Donnell E, Johnson M, Slater L, Thorne C, Zheng S, Stir- ling R, Chan FKS, Li L, Boothroyd RJ (2021) Green infrastruc- ture: the future of urban flood risk management? Wiley Inter- discip Rev Water 8(6):1–18. [CrossRef]

- Greenway M (2017) Stormwater wetlands for the enhancement of envi- ronmental ecosystem services: case studies for two retrofit wet- lands in Brisbane. Aust J Clean Prod 163(3):S91–S100. [CrossRef]

- Grimm NB, Faeth SH, Golubiewski NE, Redman CL, Wu J, Bai X, Briggs JM (2008) Global change and the ecology of cities. Sci- ence 319(5864):756–760. [CrossRef]

- Grimmond S (2007) Urbanization and global environmental change: local effects of urban warming. Geogr J 173(1):83–88. [CrossRef]

- Gunnell K, Mulligan M, Francis RA, Hole DG (2019) Evaluating natu- ral infrastructure for flood management within the watersheds of selected global cities. Sci Total Environ 670:411–424. [CrossRef]

- Haase D, Larondelle N, Andersson E, Artmann M, Borgström S, Breuste J, Gomez-Baggethun E, Gren Å, Hamstead Z, Hansen R, Kabisch N, Kremer P, Langemeyer J, Rall EL, McPhearson T, Pauleit S, Qureshi S, Schwarz N, Voigt A, Elmqvist T (2014) A quantitative review of urban ecosystem service assessments: concepts, models, and implementation. Ambio 43(4):413–433. [CrossRef]

- Haupt SE, Kosovic B, Shaw W, Berg LK, Churchfield M, Cline J, Draxl C, Ennis B, Koo E, Kotamarthi R, Mazzaro L, Miro- cha J, Moriarty P, Muñoz-Esparza D, Quon E, Rai RK, Rob- inson M, Sever G (2019) On bridging a modeling scale gap: mesoscale to microscale coupling for wind energy. Bull Am.

- Meteor Soc 100(12):2533–2549. [CrossRef]

- Hayes AT, Jandaghian Z, Lacasse MA, Gaur A, Lu H, Laouadi A, Ge H, Wang L (2022) Nature-based solutions (NBSs) to mitigate urban heat island (UHI) effects in Canadian cities. Buildings. [CrossRef]

- Herath P, Halwatura RU, Jayasinghe GY (2018a) Evaluation of green infrastructure effects on tropical Sri Lankan urban context as an urban heat island adaptation strategy. Urban for Urban Green 29(April):212–222. [CrossRef]

- Herath P, Halwatura RU, Jayasinghe GY (2018ab) Modeling a tropi- cal urban context with green walls and green roofs as an urban heat island adaptation strategy. Procedia Eng. [CrossRef]

- Herath P, Thatcher M, Jin H, Bai X (2021) Effectiveness of urban sur- face characteristics as mitigation strategies for the excessive sum- mer heat in cities. Sustain Cities Soc 72(June):103072. [CrossRef]

- Herath P, Thatcher M, Jin H, Bai X (2023) Comparing the cooling effectiveness of operationalisable urban surface combination scenarios for summer heat mitigation. Sci Total Environ. [CrossRef]

- Herath P, Bai X, Jin H, Thatcher M (2024) Does the spatial configura- tion of urban parks matter in ameliorating extreme heat? Urban Clim 53(January):101756. [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Cantis P, McPhearson T (2021) Mapping supply of and demand for ecosystem services to assess environmental justice in New York City. Ecol Appl 31(6):e02390. [CrossRef]

- Herslund L, Backhaus A, Fryd O, Jørgensen G, Jensen MB, Limbumba TM, Liu L, Mguni P, Mkupasi M, Workalemahu L, Yeshitela K (2018) Conditions and opportunities for green infrastructure— aiming for green, water-resilient cities in Addis Ababa and Dar es Salaam. Landsc Urban Plan 180(October):319–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.10.

- Hettiarachchi S, Wasko C, Sharma A (2022) Rethinking urban storm water management through resilience—the case for using green infrastructure in our warming world. Cities 128(May):103789. [CrossRef]

- Höppe P (1999) The physiological equivalent temperature - A univer- sal index for the biometeorological assessment of the thermal environment. Int J Biometeorol 43(2):71–75. [CrossRef]

- Howard L (1833) The climate of London: vol I–III (IAUC-Int). Harvey and Darton, London.

- Hunziker S, Gubler S, Calle J, Moreno I, Andrade M, Velarde F, Ticona L, Carrasco G, Castellón Y, Oria C, Croci-Maspoli M, Konzel- mann T, Rohrer M, Brönnimann S (2017) Identifying, attrib- uting, and overcoming common data quality issues of manned station observations. Int J Climatol 37(11):4131–4145. [CrossRef]

- Hurley PT, Emery MR (2018) Locating provisioning ecosystem ser- vices in urban forests: forageable woody species in New York City, USA. Landsc Urban Plan 170:266–275. [CrossRef]

- Imran HM, Kala J, Ng AWM, Muthukumaran S (2018) Effectiveness of green and cool roofs in mitigating urban heat island effects during a heatwave event in the city of Melbourne in southeast Australia. J Clean Prod 197:393–405. [CrossRef]

- Jeong H, Broesicke OA, Drew B, Li D, Crittenden JC (2016) Life cycle assessment of low impact development technologies com- bined with conventional centralized water systems for the City of Atlanta, Georgia. Front Environ Sci Eng 10(6):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Zevenbergen C, Ma Y (2018) Urban pluvial flooding and stormwater management: a contemporary review of China’s chal- lenges and “sponge cities” strategy. Environ Sci Policy 80(Sep- tember):132–143. [CrossRef]

- Jones TS (2019) Advances in environmental measurement systems : remote sensing of urban methane emissions and tree sap flow quantification [Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/5b9d800f74f586d81be2 94e16178067a/1?cbl=44156&pq-origsite=gscholar&parentSess ionId=ZNOLN7cmoNse708nzqnZf9nEoW2BQreiLexwWsic fZM%3D.

- Jonker MF, van Lenthe FJ, Donkers B, Mackenbach JP, Burdorf A (2014) The effect of urban green on small-area (healthy) life expectancy. J Epidemiol Community Health 68(10):999–1002. [CrossRef]

- Kamal-chaoui L, Robert A (2009) Competitive cities and climate change. In: OECD Regional Development Working Papers (No. 2; Issue No. 2). Available online: http://www.forum15.org.il/art_images/files/103/COMPETITIVE-CITIES-CLIMATE-CHANGE.pdf.

- Karlsson M, Alfredsson E, Westling N (2020) Climate policy co- benefits: a review. Clim Policy 20(3):292–316. [CrossRef]

- Khodadad M, Aguilar-Barajas I, Khan AZ (2023) Green infrastruc- ture for urban flood resilience: a review of recent literature on bibliometrics, methodologies, and typologies. Water 15:523. [CrossRef]

- Kim G, Coseo P (2018) Urban park systems to support sustainabil- ity: the role of urban park systems in hot arid urban climates. Forests 9(7):1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kim SY, Kim BHS (2017) The effect of urban green infrastructure on disaster mitigation in Korea. Sustainability (switzerland) 9(6):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kim G, Miller PA (2019) The impact of green infrastructure on human health and well-being: the example of the huckleberry trail and the Heritage Community Park and Natural Area in Blacksburg Virginia. Sustain Cit Soc 48(March):101562. [CrossRef]

- King A, Shackleton CM (2020) Maintenance of public and private urban green infrastructure provides significant employment in Eastern Cape towns, South Africa. Urban for Urban Green 54(February):126740. [CrossRef]

- Kleinschroth F, Kowarik I (2020) COVID-19 crisis demonstrates the urgent need for urban greenspaces. Front Ecol Environ 18(6):318–319. [CrossRef]

- Koppelaar R, Marvuglia A, Havinga L, Brajković J, Rugani B (2021) Is agent-based simulation a valid tool for studying the impact of nature-based solutions on local economy? A case study of four european cities. Sustainability (switzerland) 13(13):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Koskela H, Pain R (2000) Revisiting fear and place: women’s fear of attack and the built environment. Geoforum 31(2):269–280. [CrossRef]

- Kowarik I (2019) The “Green Belt Berlin”: establishing a green- way where the Berlin Wall once stood by integrating eco- logical, social and cultural approaches. Landsc Urban Plan 184(August):12–22. [CrossRef]

- Krayenhoff ES, Jiang T, Christen A, Martilli A, Oke TR, Bailey BN, Nazarian N, Voogt JA, Giometto MG, Stastny A, Crawford BR (2020) A multi-layer urban canopy meteorological model with trees (BEP-Tree): Street tree impacts on pedestrian-level climate. Urban Clim 32(July):100590. [CrossRef]

- Kuang W, Dou Y (2020) Investigating the patterns and dynamics of urban green space in China’s 70 major cities using satellite remote sensing. Remote Sens. [CrossRef]

- La Rosa D, Spyra M, Inostroza L (2016) Indicators of cultural ecosys- tem services for urban planning: a review. Ecol Ind 61:74–89. [CrossRef]

- Lam CKC, Gallant AJE, Tapper NJ (2018) Perceptions of thermal comfort in heatwave and non-heatwave conditions in Melbourne, Australia. Urban Clim 23:204–218. [CrossRef]

- Landor-Yamagata JL, Kowarik I, Fischer LK (2018) Urban foraging in Berlin: people, plants and practices within the metropolitan green infrastructure. Sustainability (switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer J, Camps-Calvet M, Calvet-Mir L, Barthel S, Gómez- Baggethun E (2018) Stewardship of urban ecosystem services: understanding the value(s) of urban gardens in Barcelona. Landsc Urban Plan 170(September):79–89. [CrossRef]

- Le T, Wang L, Haghani S (2019) Design and implementation of a DASH7-based wireless sensor network for green infrastruc- ture. In: World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2019: Emerging and Innovative Technologies and International Perspectives - Selected Papers from the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress. 2019; 2016, 118–129.

- Lee YC, Kim KH (2015) Attitudes of citizens towards urban parks and green spaces for urban sustainability: The case of Gyeo- ngsan City Republic of Korea. Sustainability (switzerland) 7(7):8240–8254. [CrossRef]

- Lemonsu A, Viguié V, Daniel M, Masson V (2015) Vulnerability to heat waves: Impact of urban expansion scenarios on urban heat island and heat stress in Paris (France). Urban Clim 14:586–605. [CrossRef]

- Lewis AD, Bouman MJ, Winter AM, Hasle EA, Stotz DF, Johnston MK, Klinger KR, Rosenthal A, Czarnecki CA (2019) Does nature need cities? Pollinators reveal a role for cities in wildlife conservation. Front Ecol Evol 7(Jun):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Liao W, Rigden AJ, Liu X, Wang D, Malyshev S, Shevliakova E (2019a) Urban heat island: aerodynamics or imperviousness? Sci Adv 5(4):1–5. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Zhou Y, Yu S, Jia G, Li H, Li W (2019b) Urban heat island impacts on building energy consumption: a review of approaches and findings. Energy 174:407–419. [CrossRef]

- Lin BB, Philpott SM, Jha S, Liere H (2017) Urban agriculture as a productive green infrastructure for environmental and social well-being. Springer, pp 155–179. [CrossRef]

- Lindfield M, Teipelke R (2017) How to finance urban infrastructure— explainer. Available online: https://www.c40cff.org/knowledge-library/explainer- how-to-finance-urban-infrastructure.

- Lindley S, Pauleit S, Yeshitela K, Cilliers S, Shackleton C (2018) Rethinking urban green infrastructure and ecosystem services from the perspective of sub-Saharan African cities. Landsc Urban Plan 180:328–338. [CrossRef]

- Liquete C, Udias A, Conte G, Grizzetti B, Masi F (2016) Integrated valuation of a nature-based solution for water pollution con- trol. Highlighting hidden benefits. Ecosyst Serv 22(Septem- ber):392–401. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Wang X (2021) Reexamine the value of urban pocket parks under the impact of the COVID-19. Urban for Urban Green 64(July):127294. [CrossRef]

- Lo AY, Byrne JA, Jim CY (2017) How climate change perception is reshaping attitudes towards the functional benefits of urban.

- trees and green space: lessons from Hong Kong. Urban for Urban.

- Green 23:74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.03.007 Lopez B, Kennedy C, Field C, Mcphearson T (2021) Who benefits from urban green spaces during times of crisis? Perception and use of urban green spaces in New York City during the COVID- 19 pandemic. Urban for Urban Green. [CrossRef]

- Lundgren K, Kjellstrom T (2013) Sustainability challenges from cli- mate change and air conditioning use in urban areas. Sustain- ability (switzerland) 5(7):3116–3128. [CrossRef]

- Lyytimäki J, Petersen LK, Normander B, Bezák P (2008) Nature as a nuisance? Ecosystem services and disservices to urban lifestyle. Environ Sci 5(3):161–172. [CrossRef]

- Maragno D, Gaglio M, Robbi M, Appiotti F, Fano EA, Gissi E (2018) Fine-scale analysis of urban flooding reduction from green infrastructure: an ecosystem services approach for the management of water flows. Ecol Model 386(August):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Martilli A, Krayenhoff ES, Nazarian N (2020) Is the Urban Heat Island intensity relevant for heat mitigation studies? Urban Clim 31(September):1–4. [CrossRef]

- Masoudi M, Tan PY, Liew SC (2019) Multi-city comparison of the relationships between spatial pattern and cooling effect of urban green spaces in four major Asian cities. Ecol Indic 98(November):200–213. [CrossRef]

- Matasov V, Marchesini LB, Yaroslavtsev A, Sala G, Fareeva O, Seregin I, Castaldi S, Vasenev V, Valentini R (2020) IoT moni- toring of urban tree ecosystem services: possibilities and chal- lenges. Forests. [CrossRef]

- Mathey J, Rößler S, Banse J, Lehmann I, Bräuer A (2015) Brown- fields as an element of green infrastructure for implementing ecosystem services into urban areas. J Urban Plan Dev. [CrossRef]

- Matos Silva C, Serro J, Dinis Ferreira P, Teotónio I (2019) The socio- economic feasibility of greening rail stations: a case study in lisbon. Eng Econ 64(2):167–190. [CrossRef]

- MEA (2005) Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) Ecosystems and human well-being: wetlands and water synthesis. U World Resources Institute Washington. [CrossRef]

- Meerow S, Newell JP (2017) Spatial planning for multifunctional green infrastructure: growing resilience in Detroit. Landsc Urban Plan Meili 159:62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.10.005 N, Manoli G, Burlando P, Carmeliet J, Chow WTL, Coutts AM, Roth M, Velasco E, Vivoni ER, Fatichi S (2021) Tree effects on urban microclimate: Diurnal, seasonal, and climatic temperature differences explained by separating radiation, evapotranspiration, and roughness effects. Urban for Urban Green 58:126970. [CrossRef]

- Mell I (2013) Can you tell a green field from a cold steel rail? Exam- ining the “green” of Green Infrastructure development. Local Environ 18(2):152–166. [CrossRef]

- Mell I (2021) ‘But who’s going to pay for it?’ Contemporary approaches to green infrastructure financing, development and governance in London, UK. J Environ Plan Policy Manag 23(5):628–645. [CrossRef]

- Mell I, Henneberry J, Hehl-Lange S, Keskin B (2016) To green or not to green: ESTABLISHING the economic value of green infra- structure investments in The Wicker, Sheffield. Urban for Urban Green 18:257–267. [CrossRef]

- Mesimäki M, Hauru K, Lehvävirta S (2019) Do small green roofs have the possibility to offer recreational and experiential benefits in a dense urban area? A case study in Helsinki Finland. Urban for Urban Green 40(September):114–124. [CrossRef]

- Miller SM, Montalto FA (2019) Stakeholder perceptions of the eco- system services provided by Green Infrastructure in New York City. Ecosyst Serv 37(March):100928. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei PA, Haghighat F (2010) Approaches to study urban heat island - abilities and limitations. Build Environ 45(10):2192–2201. [CrossRef]

- Molineux CJ, Gange AC, Connop SP, Newport DJ (2015) Using recy- cled aggregates in green roof substrates for plant diversity. Ecol Eng 82:596–604. [CrossRef]

- Mulligan J, Bukachi V, Clause JC, Jewell R, Kirimi F, Odbert C (2020) Hybrid infrastructures, hybrid governance: new evidence from Nairobi (Kenya) on green-blue-grey infrastructure in informal settlements: “Urban hydroclimatic risks in the 21st century: integrating engineering, natural, physical and social sciences to build. Anthropocene 29:100227. [CrossRef]

- Nagendra H, Bai X, Brondizio ES, Lwasa S (2018) The urban south and the predicament of global sustainability. Nat Sustain 1(7):341– 349. [CrossRef]

- Ngulani T, Shackleton CM (2019) Use of public urban green spaces for spiritual services in Bulawayo Zimbabwe. Urban for Urban Green 38(November):97–104. [CrossRef]

- Niu H, Clark C, Zhou J, Adriaens P (2010) Scaling of economic ben- efits from green roof implementation in Washington DC. Environ Sci Technol 44(11):4302–4308. [CrossRef]

- Norman-Burgdolf H, Rieske LK (2021) Healthy trees—healthy people: a model for engaging citizen scientists in exotic pest detection in urban parks. Urban for Urban Green. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2020) Smart cities and inclusive growth. In: Smart Cities and Inclusive Growth © OECD 2020: Vol. per year (Issue Typology of smart cities). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/cities/OECD_Policy_ Paper_Smart_Cities_and_Inclusive_Growth.pdf.

- Oh K, Jeong Y, Lee D, Lee W, Choi J (2005) Determining development density using the urban carrying capacity assessment system. Landsc Urban Plan 73(1):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Oke TR, Crowther JM, McNaughton KG, Monteith JL, Gardiner B, Jarvis PG, Monteith JL, Shuttleworth WJ, Unsworth MH (1989) The micrometeorology of the urban forest. Philos Trans R Soc Lond, B 324(1223):335–349. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira S, Andrade H, Vaz T (2011) The cooling effect of green spaces as a contribution to the mitigation of urban heat: a case study in Lisbon. Build Environ 46(11):2186–2194. [CrossRef]

- Orsini F, Gasperi D, Marchetti L, Piovene C, Draghetti S, Ramazzotti S, Bazzocchi G, Gianquinto G (2014) Exploring the produc- tion capacity of rooftop gardens (RTGs) in urban agriculture: the potential impact on food and nutrition security, biodiversity and other ecosystem services in the city of Bologna. Food Secur 6(6):781–792. [CrossRef]

- Orsini F, Pennisi G, Michelon N, Minelli A, Bazzocchi G, Sanyé-Men- gual E, Gianquinto G (2020) Features and functions of multi- functional urban agriculture in the global north: a review. Front Sustain Food Syst 4(November):1–27. [CrossRef]

- Oswald TK, Rumbold AR, Kedzior SGE, Kohler M, Moore VM (2021) Mental health of young australians during the COVID-19 pan- demic: exploring the roles of employment precarity, screen time, and contact with nature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Park CY, Lee DK, Krayenhoff ES, Heo HK, Hyun JH, Oh K, Park TY (2019) Variations in pedestrian mean radiant temperature based on the spacing and size of street trees. Sustain Cities Soc 48(March):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Patricola CM, Wehner MF (2018) Anthropogenic influences on major tropical cyclone events. Nature 563(7731):339–346. [CrossRef]

- Pauleit S, Zölch T, Hansen R, Randrup TB, van den Bosch CK (2017) Nature-based solutions and climate change—four shades of green. In: Kabisch N, Korn H, Stadler J, Bonn A (eds) Nature-based solutions to climate change adaptation in urban areas linkages between science, policy and practice. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Pierre A, Amoroso N, Kelly S (2019) Geodesign application for bio-swale design: rule-based approach stormwater manage- ment for Ottawa Street North in Hamilton Ontario. Lands Res 44(5):642–658. [CrossRef]

- Potschin-Young M, Haines-Young R, Görg C, Heink U, Jax K, Schleyer C (2018) Understanding the role of conceptual frameworks: read- ing the ecosystem service cascade. Ecosyst Serv 29:428–440. [CrossRef]

- Privitera R, La Rosa D (2018) Reducing seismic vulnerability and energy demand of cities through green infrastructure. Sustain- ability (switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Prodanovic V, Hatt B, McCarthy D, Zhang K, Deletic A (2017) Green walls for greywater reuse: understanding the role of media on pollutant removal. Ecol Eng 102:625–635. [CrossRef]

- Quatrini V, Tomao A, Corona P, Ferrari B, Masini E, Agrimi M (2019) Is new always better than old? Accessibility and usability of the urban green areas of the municipality of Rome. Urban for Urban Green 37(July):126–134. [CrossRef]

- Ramyar R, Ackerman A, Johnston DM (2021) Adapting cities for cli- mate change through urban green infrastructure planning. Cities 117(November):103316. [CrossRef]

- Raymond CM, Frantzeskaki N, Kabisch N, Berry P, Breil M, Nita MR, Geneletti D, Calfapietra C (2017) A framework for assessing and implementing the co-benefits of nature-based solutions in urban areas. Environ Sci Policy 77(July):15–24. [CrossRef]

- Revi A, Satterthwaite DE, Aragón-Durand F, Corfee-Morlot J, Kiunsi RBR, Pelling M, Roberts DC, Solecki W (2014) Urban areas. In: C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mas- trandrea, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. R. Mastrandrea, & L. L. White (Eds.) Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sec- toral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 267–296). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds HL, Brandt L, Fischer BC, Hardiman BS, Moxley DJ, Sand- weiss E, Speer JH, Fei S (2020) Implications of climate change for managing urban green infrastructure: an Indiana US case study. Clim Change 163(4):1967–1984. [CrossRef]

- Herms DA, Gardiner MM (2018) Exotic trees contribute to urban forest diversity and ecosystem services in inner-city Cleveland, OH. Urban for Urban Green 29:367–376. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rojas MI, Huertas-Fernández F, Moreno B, Martínez G, Grindlay AL (2018) A study of the application of permeable pavements as a sustainable technique for the mitigation of soil sealing in cities: a case study in the south of Spain. J Environ Manag 205:151–162. [CrossRef]

- Roy S, Byrne J, Pickering C (2012) A systematic quantitative review of urban tree benefits, costs, and assessment methods across cities in different climatic zones. Urban for Urban Green 11(4):351– 363. [CrossRef]

- Saarikoski H, Primmer E, Saarela SR, Antunes P, Aszalós R, Baró F, Berry P, Blanko GG, Goméz-Baggethun E, Carvalho L, Dick J, Dunford R, Hanzu M, Harrison PA, Izakovicova Z, Kertész M, Kopperoinen L, Köhler B, Langemeyer J, Young J (2018) Institutional challenges in putting ecosystem service knowledge in practice. Ecosyst Serv 29(September):579–598. [CrossRef]

- Salata KD, Yiannakou A (2020) The quest for adaptation through spatial planning and ecosystem-based tools in resilience strate- gies. Sustainability (switzerland) 12(14):1–16. [CrossRef]

- Santiago JL, Buccolieri R, Rivas E, Calvete-Sogo H, Sanchez B, Mar- tilli A, Alonso R, Elustondo D, Santamaría JM, Martin F (2019) CFD modelling of vegetation barrier effects on the reduction of traffic-related pollutant concentration in an avenue of Pamplona Spain. Sustain Cit Soc 48(February):101559. [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite D (2010) The contribution of cities to global warming and their potential contributions to solutions. Environ Urban ASIA 1(1):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Säumel I, Reddy SE, Wachtel T (2019) Edible city solutions-one step further to foster social resilience through enhanced socio-cultural ecosystem services in cities. Sustainability (switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Shackleton CM, Blair A, De Lacy P, Kaoma H, Mugwagwa N, Dalu MT, Walton W (2018) How important is green infrastructure in small and medium-sized towns? Lessons from South Africa. Landsc Urban Plan 180:273–281.

- ShiP,BaiX,KongF,FangJ,GongD,ZhouT,GuoY,LiuY,DongW, WeiZ,HeC,YuD,WangJ,YeQ,YuR,ChenD(2017)Urbani- zation and air quality as major drivers of altered spatiotemporal patterns of heavy rainfall in China. Landsc Ecol 32(8):1723– 1738. [CrossRef]

- Shi L, Halik Ü, Abliz A, Mamat Z, Welp M (2020) Urban green space accessibility and distribution equity in an arid oasis city: Urumqi China. Forests. [CrossRef]

- Shifflett SD, Newcomer-Johnson T, Yess T, Jacobs S (2019) Interdisci- plinary collaboration on green infrastructure for urbanwatershed management: an Ohio case study. Water (switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Simon H, Fallmann J, Kropp T, Tost H, Bruse M (2019) Urban trees and their impact on local Ozone concentration—a microclimate modeling study. Atmosphere. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama T, Sharifi F, Yao Z, Herath P, Frantzeskaki N (2021) Nature Fix for Healthy Cities: What Planners and Designers Need to Know for Planning Urban Nature with Health-benefits in Mind. The Nature of Ciites Blog. Available online: https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2021/08/30/nature-fix-for-healthy-cities-what-planners-and- designers-need-to-know-for-planning-urban-nature-with-health- benefits-in-mind/.

- Taghizadeh S, Khani S, Rajaee T (2021) Hybrid SWMM and parti- cle swarm optimization model for urban runoff water quality control by using green infrastructures (LID-BMPs). Urban for Urban Green 60(February):127032. [CrossRef]

- Tavakol-Davani HE, Tavakol-Davani H, Burian SJ, McPherson BJ, Barber ME (2019) Green infrastructure optimization to achieve pre-development conditions of a semiarid urban catchment. Envi- ron Sci: Water Res Technol 5(6):1157–1171. [CrossRef]

- Thompson K, Sherren K, Duinker PN (2019) The use of ecosystem services concepts in Canadian municipal plans. Ecosyst Serv 38(May):100950. [CrossRef]

- Threlfall CG, Mata L, Mackie JA, Hahs AK, Stork NE, Williams NSG, Livesley SJ (2017) Increasing biodiversity in urban green spaces through simple vegetation interventions. J Appl Ecol 54(6):1874–1883. [CrossRef]

- Tomasi M, Favargiotti S, van Lierop M, Giovannini L, Zonato A (2021) Verona adapt Modelling as a planning instrument: applying a climate-responsive approach in Verona Italy. Sustainability (swit- zerland). [CrossRef]

- UN (2013) Chapter III: Towards sustainable cities. In Department of Economic and Social Affairs (Ed.), World Economic and Social Survey 2013 (pp. 53–84). United Nations. [CrossRef]

- UN DESA (2018) World Economic Situation and Prospects 2018 report. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/WESP2018_Full_Web-1.pdf.

- United Nations (2018) Tracking progress towards inclusive, safe, resil- ient and sustainable cities and human settlements. In: Tracking Progress Towards Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable Cit- ies and Human Settlements SDG 11 Synthesis Report.

- Veerkamp CJ, Schipper AM, Hedlund K, Lazarova T, Nordin A, Han- son HI (2021) A review of studies assessing ecosystem services provided by urban green and blue infrastructure. Ecosyst Serv. [CrossRef]

- Venter ZS, Barton DN, Gundersen V, Figari H, Nowell M (2020) Urban nature in a time of crisis: recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo Norway. Envi- ron Res Lett. [CrossRef]

- Vert C, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Gascon M, Grellier J, Fleming LE, White MP, Rojas-Rueda D (2019) Health benefits of physical activity related to an urban riverside regeneration. Int J Environ Res Pub- lic Health. [CrossRef]

- Victoria State Government (2017) Plan Melbourne 2017–2050 Metro- politan planning strategy (The State of Victoria Department of Environment- Land- Water and Planning (ed.)). Impact Digital, Brunswick. planmelbourne.vic.gov.au.

- Viecco M, Vera S, Jorquera H, Bustamante W, Gironás J, Dobbs C, Leiva E (2018) Potential of particle matter dry deposition on green roofs and living walls vegetation for mitigating urban atmospheric pollution in semiarid climates. Sustainability (swit- zerland). [CrossRef]

- Vojinovic Z, Alves A, Gómez JP, Weesakul S, Keerakamolchai W, Meesuk V, Sanchez A (2021) Effectiveness of small- and large- scale nature-based solutions for flood mitigation: the case of Ayutthaya Thailand. Sci Total Environ 789:147725. [CrossRef]

- Waite M, Cohen E, Torbey H, Piccirilli M, Tian Y, Modi V (2017) Global trends in urban electricity demands for cooling and heat- ing. Energy 127:786–802. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Bakker F, de Groot R, Wörtche H (2014) Effect of ecosys- tem services provided by urban green infrastructure on indoor environment: a literature review. Build Environ 77:88–100. [CrossRef]

- WangW,ZhangB,ZhouW,LvH,XiaoL,WangH,DuH,HeX (2019a) The effect of urbanization gradients and forest types on microclimatic regulation by trees, in association with climate, tree sizes and species compositions in Harbin city, northeastern China. Urban Ecosyst 22(2):367–384. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Ni Z, Chen S, Xia B (2019b) Microclimate regulation and energy saving potential from different urban green infrastructures in a subtropical city. J Clean Prod 226:913–927. [CrossRef]

- Wong CP, Jiang B, Bohn TJ, Lee KN, Lattenmaier DP, Ma D, Ouyang Z (2017) Lake and wetland ecosystem services measuring water storage and local climate regulation. Water Resourc Res RES 53:3197–3223. [CrossRef]

- Wong CP, Jiang B, Kinzig AP, Ouyang Z (2018) Quantifying multiple ecosystem services for adaptive management of green infrastruc- ture. Ecosphere. [CrossRef]

- Wortzel JD, Wiebe DJ, DiDomenico GE, Visoki E, South E, Tam V, Greenberg DM, Brown LA, Gur RC, Gur RE, Barzilay R (2021) Association between urban greenspace and mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic in a US Cohort. Front Sustain Cit 3(July):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Xu H, Zhao G (2021) Assessing the value of urban green infrastruc- ture ecosystem services for high-density urban management and development: case from the capital core area of Beijing China. Sustainability (switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Bou-Zeid E (2019) Scale dependence of the benefits and effi- ciency of green and cool roofs. Landsc Urban Plan 185(Febru- ary):127–140. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Rong H, Kang Y, Zhang F, Chegut A (2021) The financial impact of street-level greenery on New York commercial build- ings. Landsc Urban Plan 214(May):104162. [CrossRef]

- Yin C, Xiao J, Zhang T (2021) Effectiveness of Chinese regulatory planning in mitigating and adapting to climate change: compara- tive analysis based on Q methodology. Sustainability (switzer- land). [CrossRef]

- Yu Z, Yang G, Zuo S, Jørgensen G, Koga M, Vejre H (2020) Criti- cal review on the cooling effect of urban blue-green space: a threshold-size perspective. Urban for Urban Green 49(Febru- ary):126630. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Dong R (2018) Impacts of street-visible greenery on housing prices: evidence from a hedonic price model and a massive street view image dataset in Beijing. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inform. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Villarini G, Vecchi GA, Smith JA (2018) Urbanization exac- erbated the rainfall and flooding caused by hurricane Harvey in Houston. Nature 563(7731):384–388. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Li S, Sun X, Tong J, Fu Z, Li J (2019) Sustainability of urban soil management: analysis of soil physicochemical properties and bacterial community structure under different green space types. Sustainability (switzerland) 11(5):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Li J, Zhou Z (2022) Ecosystem service cascade: concept, review, application and prospect. Ecol Indic 137(Novem- ber):108766. [CrossRef]

- Zhou K, Song Y, Tan R (2021) Public perception matters: estimating homebuyers’ willingness to pay for urban park quality. Urban for Urban Green 64(February):127275. [CrossRef]

- Zölch T, Henze L, Keilholz P, Pauleit S (2017) Regulating urban sur- face runoff through nature-based solutions—an assessment at the micro-scale. Environ Res 157(April):135–144. [CrossRef]

- Žuvela-Aloise M, Koch R, Buchholz S, Früh B (2016) Modelling the potential of green and blue infrastructure to reduce urban heat load in the city of Vienna. Clim Change 135(3–4):425–438. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).