Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Vaccination

Uses of Cundeamor

Steps to a “Spiritually Aligned” System of Health Care

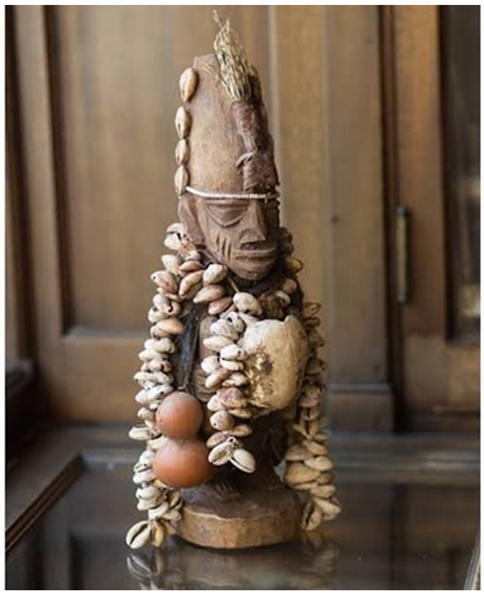

Who is Babalu?30

- Do my prayers remain unanswered

- Like a beggar at your sleeve?

- Babalu-aye spins on his crutches

- Says, “Leave if you want

- If you want to leave”

References

- Aelion, David Maurice. “Freedom of Religion: A Case Study of the Church of Lukumí Babalú Ayé v. City of Hialeah, 2010. FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1105. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1105.

- Aiyejina, F., & Gibbons, R. (1999). Orisa (Orisha) Tradition in Trinidad. Caribbean Quarterly, 45(4), 35–50. [CrossRef]

- Brandon, George. Light from the forest: How Santería heals through plants. Blue Unity Press, 1991.

- Brandon, George. Santeria from Africa to the New World: The Dead Sell Memories. Indiana University Press, 1997.

- Brandon, George and Leslie Desmangles. “Introduction: Good Spirit, Good Medicine; Religious Foundations of Healing in the Caribbean.” Anthropologica 54, no. 2 (2012): 159–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24467398.

- Brown, David H. “Conjure/Doctors: An Exploration of a Black Discourse in America, Antebellum to 1940.” Folklore Forum, 1990.

- Brown, David H. “Thrones of the Orichas: Afro-Cuban Altars in New Jersey, New York, and Havana.” African Arts 26, no. 4 (1993): 44–87. [CrossRef]

- Brown, David H. Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion. University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Buckley, Anthony D. Yoruba Medicine. Oxford: Clarendon, 1985.

- Cabrera, Lydia. El Monte: Notes on the Religions, Magic, Superstitions, and Follore of the Blact and Creole People of Cuba. trans. David Font-Navarrete. Duke University Press, 2003.

- Cañizares, Raúl J. Babalú-Ayé: Santeria and the Lord of Pestilence. New York: Original Publishers, 2000.

- Castor, Nicole Fadeke. “Shifting Multicultural Citizenship: Trinidad Orisha Opens the Road.” Cultural Anthropology, 28 475-489, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Castor, Nicole Fadeke. Spiritual Citizenship: Transnational Pathways from Black Power to Ifá in Trinidad. Duke University Press, 2017.

- Daniel, Yvonne. Caribbean and Atlantic Diaspora Dance: Igniting Citizenship. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

- Dianteill, Erwan, and Martha Swearingen. “From Hierography to Ethnography and Back: Lydia Cabrera’s Texts and the Written Tradition in Afro-Cuban Religions.” The Journal of American Folklore 116, no. 461 (2003): 273–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4137792.

- Dixon, P. J. “Uneasy Lies the Head: Politics, Economics, and the Continuity of Belief among Yoruba of Nigeria.” Comparative Studies in Society and History. 1991;33(1):56-85. [CrossRef]

- Ecun, Oba. Ita: Mythology of the Yoruba Religion. Miami: Oba Ecun Books, 1996.

- Ellis, A. B. The Yoruba-speaking peoples of the Slave Coast of West Africa. Their religion, manners, customs, laws, language, etc. London: Chapman and Hall, 1894.

- Forde, Maarit. “The Moral Economy of Spiritual Work: Money and Rituals in Trinidad and Tobago.” in Obeah and Other Powers: The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing. eds. Maarit Forde and Diana Patton. Duke University Press, 2012.

- Friedson, Steven M. Remains of Ritual: Northern Gods in a Southern Land. Chicago: University of Chicago Pres, 2009.

- Glazier, Stephen D. “African Cults and Christian Churches in Trinidad.” Journal of Religious Thought, 39, no. 2 (1982): 17-25.

- Glazier, Stephen D. “Wither Sango? An Inquiry into Sango’s ‘Authenticity’ and Prominence in the Caribbean.” in Sango in Africa and the African Diaspora. Joel E. Tishken, Toyin Falola, and A. Akinyemi, editors. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009. pp. 233–247.

- Glazier, Stephen D. “Health and Illness” (with Mary J. Hallin) in 21st Century Anthropology, H. James Birx, editor. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Reference, volume 2, 2010, pp. 925–935.

- Glazier, Stephen D. “Religious Developments in the Caribbean Between 1865 and 1945” in The Cambridge History of Religions in America. Vol. II: Religions in America, 1790–1945. Stephen J. Stein, editor. Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 727–748.

- Glazier, Stephen D. “If ‘Old Heads’ Could Talk.” Anthropologica 54 no. 2 (2012): 199-209.

- Glazier, Stephen D. “Sango Healers and Healing in the Caribbean.” in Patsy Sutherland, Roy Moodley and Barry Chavannes, eds. Caribbean Healing Traditions: Implications for Health and Mental Health. Routledge, 2014, pp. 89-101.

- Griffith, E. H., Mahy, G. E. “Spiritual Baptist Mourning: A Model of Contemplative Meditation.” in: Pichot, P., Berner, P., Wolf, R., Thau K. (eds) Psychiatry: The State of the Art. Springer, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, Ezra E. H. Ye Shall Dream: Patriarch Granville Williams and the Barbados Spiritual Baptists. University of the West Indies Press, 2010.

- Hagedorn, Katherine J. Divine Utterances: The Performance of Afro-Cuban Santería Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001.

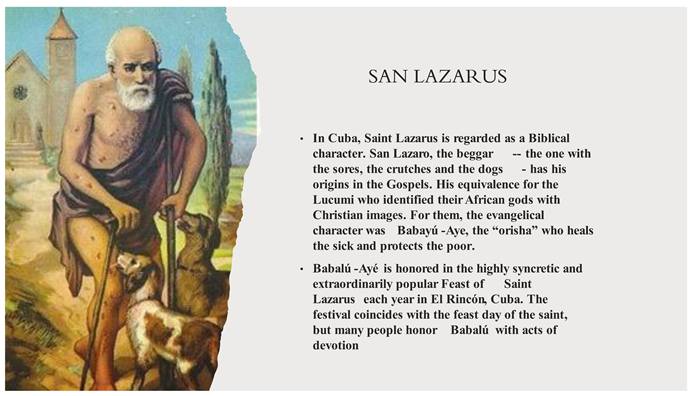

- Hagedorn, Katherine J. “Long Day’s Journey to Rincón: From Suffering to Resistance in the Procession of San Lázaro/Babalú Ayé.” British Journal of Ethnomusicology 11, no. 1 (2002): 43–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4149885.

- Herskovits, Melville. Dahomey: An Ancient West African Kingdom. J.J. Augustin, 1938.

- Idowu, E. Bolaji. Olodumare: God in Yoruba Belief. London: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1962.

- Lele, Ocha’ni. The Diloggun: The Orishas, Proverbs, Sacrifices, and Prohibitions of Cuban Santeria. Rochester, Vt.: Destiny Books, 2003.

- Levi-Strauss, Claude. The Savage Mind. University of Chicago Press, 1966.

- Lovell, Nadia. Cord of Blood: Possession and the Making of Voodoo. London: Pluto Press, 2002.

- Lucas, J. Olumide. 1996. The Religion of the Yoruba: Being an Account of the Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Yoruba People of Southwest Nigeria; especially in Relation to the Religion of Egypt. Brooklyn, NY: Athelia Henrietta Press, 1996.

- Mahabir, Kumar. Traditional Medicines and Women Healers in Trinidad” NALIS, 2002.

- Mason, Michael Atwood. 2009. “Baba Who? Babalú! Blog.” http://baba-who-babalu-santeria.blogspot.com/.

- McKenzie, Peter. Hail Orisha! A Phenomenology of a West African Religion in the Mid-Nineteenth Century. Brill, 1997.

- McNeal, Keith E. “Embodied Minds, Cultural Corpses, and the Work of the Dead: On Teaching the Anthropology of Death and Mortuary Ritual.” Embodied Pedagogies in the Study of Religion. Routledge, 2025. 225-234.

- Murphy, Joseph M. Working the Spirit: Ceremonies of the African Diaspora, Beacon Press. 1994.

- O’Brien, David M. Animal Sacrifice and Religious Freedom: Church of the Lukumi Babalu-Aye v. City of Hialeah. University of Kansas, 2004.

- Olupona, Jacob K., and Rowland O. Abiodun, eds. Ifá Divination, Knowledge, Power, and Performance. Indiana University Press, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1b7x4sw.

- Oripelaye M. M., Olasode O. A. and Onayemi O. 2016. “Smallpox Eradication and Cultural Evolution among the Yoruba Race.” Journal of Dermatology 3 no. 5 (2016): 1067.

- Perez, Elizabeth. 2025. A subjective response to ‘transitional phenomena’ and case study of chinoiseries in “Afro-Cuban” religions. Religion, 55 no. 2 (2025): 525–541. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Miguel “Willie.” Afro-Cuban Orisha Worship. in A. Lindsey, ed., Santería Aesthetics in Contemporary Latin American Art, pp. 51–76. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. 1996.

- Richman, Karen. Migration and Vodou. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007.

- Rosenthal, Judy. Possession, Ecstasy, and Law in Ewe Voodoo. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1999.

- Sandoval, Mercedes Cros, ‘Shopono/Babalú Ayé: God of Diseases and Plagues’, Worldview, the Orichas, and Santería: Africa to Cuba and Beyond (Gainesville, FL, 2007; online edn, Florida Scholarship Online, 14 Sept. 2011) . [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, Patsy, Roy Moodley, and J. Barry Chevannes eds. “Introduction” Caribbean Healing Traditions: Implications for Health and Mental Health. New York: Routledge, 2014, pp. 2-11.

- Thompson, Robert Faris. Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americas. The Museum for African Art, 1993. pp. 334. ISBN 9780945802136.

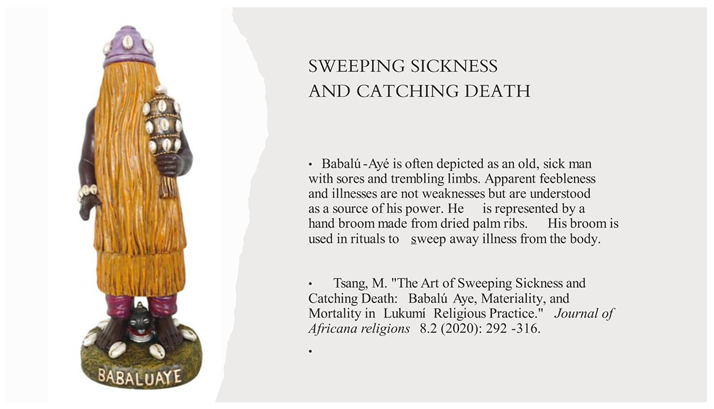

- Tsang, Martin A. “The Art of Sweeping Sickness and Catching Death: Babalú Aye, Materiality, and Mortality in Lukumí Religious Practice.” Journal of Africana Religions 13 July 2020; 8 no. 2 (2020): 292–316. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, Martin A. “Write into Being: The Production of the Self and Circulation of Ritual Knowledge in Afro-Cuban Religious Libretas.” Material Religion 17 no. 2 (2021): 228–61. [CrossRef]

- Verger, Pierre F. Notes sur le culte des orisa et vodun a Bahia, la Baie de tous les Saints, au Brésil, et à l’ancienne Côte des Esclaves en Afrique. Dakar: IFAN, 1957.

- Verger, Pierre (Fatumbi). Orisha. Les dieuxYorouba en Afrique et ou nouveau monde. Ed. A.M. Métailié, Paris 1982.

- Voeks, Robert A. 1997. Sacred Leaves of Candomblé: African Magic, Medicine, and Religion in Brazil. University of Texas Press, 1997.

- Ward, Colleen, & Beaubrun, Michael. “Trance induction and hallucination in spiritualist Baptist mourning.” Journal of Psychological Anthropology, 2 no. 4 (1979): 479–488.

- Warner-Lewis, Maureen. Trinidad Yoruba: From Mother Tongue to Memory University of Alabama Press, 1996.

- Wedenoja, William and Claudette Anderson. “Revival: an indigenous religion and spiritual healing practice in Jamaica.” In Patsy Sutherland, Roy Moodley and Barry Chavannes, eds. Caribbean Healing Traditions. New York: Routledge, 2014, pp. 128-139.

- Wenger, Susanne. 1983. A Life with the Gods in their Yoruba Homeland. Wörgl, Austria: Perlinger Verlag, 1983.

- Wumkes, Jake.” The Spirit of the Pluriverse: Africana Spirit-Based Epistemologies and Interepistemic Thinking,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Volume 91, Issue 4, (2023): 737–756, . [CrossRef]

- Zane, Wallace W. “Spiritual Baptists in the Caribbean.” in Patsy Sutherland, Roy Moodley and Barry Chavannes, eds. Caribbean Healing Traditions. New York: Routledge, 2014, pp. 140-149.

| 1 | An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 24th Annual Austin Africa Conference: “Health and Illness in Africa and the African Diaspora.” I thank George Brandon, Toyin Falola, Leslie G. Desmangles, Karen Richman. J. Brent Crosson, F. N. Castor, Ken Bilby, and Alexander Rocklin for helpful comments on earlier drafts. |

| 2 | Karen Richman. Migration and Vodou. (University Press of Florida, 2007). |

| 3 | Health and illness have been broadly defined. See, Stephen D. Glazier and Mary J. Hallen, "Health and Illness" in 21st Century Anthropology. H. James Birx, ed. (Sage Reference, volume 2, 2010): 925–935; David. H. Brown, “Thrones of the Orichas: Afro-Cuban Altars in New Jersey, New York, and Havana.” African Arts 26, no. 4 (1993): 44–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/3337075. |

| 4 | George Brandon, “The Wind that Walks Like a Man: Seeing, Naming, and the Negotiation of Contexts of Babaluaie’s Worship in Cuba and the United States”, unpublished paper. See also: https://www.caribbeanyardcampus.org/enrol/sweet-broom-and-bitter-bush/ by Rawley Gibbons. |

| 5 | James Titus Houk, Spirits, Blood, and Drums: The Orisha Religion in Trinidad (Temple University Press, 1995): 143. |

| 6 | Joseph M. Murphy, Working the Spirit: Ceremonies of the African Diaspora (Beacon Press, 1994): 105. |

| 7 | George Brandon, Light from the forest: How Santería heals through plants. (Blue Unity Press, 1991). |

| 8 | Jake Wumkes..“ The Spirit of the Pluriverse: Africana Spirit-Based Epistemologies and Interepistemic Thinking,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Volume 91, Issue 4, (2023): 737–756, https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfae028

|

| 9 | Keith E. McNeal, "Embodied Minds, Cultural Corpses, and the Work of the Dead: On Teaching the Anthropology of Death and Mortuary Ritual," Embodied Pedagogies in the Study of Religion (Routledge, 2025): 225-234. |

| 10 | Yvonne Daniel, Caribbean and Atlantic Diaspora Dance: Igniting Citizenship (University of Illinois Press, 2011). |

| 11 | Martin A. Tsang, “The Art of Sweeping Sickness and Catching Death: Babalú Aye, Materiality, and Mortality in Lukumí Religious Practice. “Journal of Africana Religions 8, no. 2 (2020): 292–316. doi: https://doi.org/10.5325/jafrireli.8.2.0292

|

| 12 | Mercedes Cros Sandova. 'Shopono/Babalú Ayé: God of Diseases and Plagues', Worldview, the Orichas, and Santería: Africa to Cuba and Beyond (Gainesville, FL, 2007; online edn, Florida Scholarship Online, 14 Sept. 2011), https://doi.org/10.5744/florida/9780813030203.003.0019, accessed 18 May 2025. Sandoval suggests that contemporary Cuban worshippers do not fear Sakpona as much as he was feared in Africa. |

| 13 | Pierre Fatumbi Verger, Orisha. Les dieux Yorouba en Afrique et ou nouveau monde. Ed. A.M. Métailié (Paris 1982). See also Pierre Fatumbi Verger, Notes sur le culte des orisa et vodun a Bahia, la Baie de tous les Saints, au Brésil, et à l’ancienne Côte des Esclaves en Afrique (IFAN, 1957). |

| 14 | Katherine J. Hagedorn, “Long Day’s Journey to Rincón: From Suffering to Resistance in the Procession of San Lázaro/Babalú Ayé.” British Journal of Ethnomusicology 11, no. 1 (2002): 43–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4149885. |

| 15 | Edwards, newly installed as president of Princeton, participated in a controversial inoculation program against smallpox. He reacted adversely to the vaccine, became ill, and died at the age of fifty-five. |

| 16 | George Washington was never inoculated. He had contracted smallpox in 1751 while visiting Barbados. He believed that he had acquired resistance to the disease. |

| 17 | M. M. Oripelaye, O. A. Olasode, and O. Onayemi, “Smallpox Eradication and Cultural Evolution among the Yoruba,” Journal of Dermatology. 2 no. 5 (2016)): 1067. |

| 18 | Stephen D. Glazier, "Wither Sango? An Inquiry into Sango's 'Authenticity' and Prominence in the Caribbean." in Sango in Africa and the African Diaspora. eds. Joel E. Tishken, Toyin Falola, and A. Akinyemi, (Indiana University Press, 2009): 233–247. |

| 19 | William Wedenoja and Claudette Anderson, “Revival: An Indigenous Religion and Spiritual Healing Practice in Jamaica.” in Patsy Sutherland, Roy Moodley, and Barry Chavannes, eds. Caribbean Healing Traditions. (Routledge, 2014): 128-139. |

| 20 | Osain is said to be from India. See, Oba Ecun, Ita: Mythology of the Yoruba Religion. (Oba Ecun Books, 1996). Other interpretations have been provided by E. Bolaji in Olodumare: God in Yoruba Belief. (Longmans, Green, and Co, 1952 and Ocha'niLele, The Diloggun: The Orishas, Proverbs, Sacrifices, and Prohibitions of Cuban Santeria. (Destiny Books, 2003). |

| 21 | Joseph M. Murphy, Working the Spirit: Ceremonies of the African Diaspora (Beacon Press, 1994):106. |

| 22 | Ezra E. Griffith and George E. Mahy, “Spiritual Baptist Mourning: A Model of Contemplative Meditation.” in: P. Pichot, P, Berner, R. Wolf, R., and K. Thau (eds) Psychiatry: The State of the Art. (Springer, 1985): 109. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-1853-9. |

| 23 | Wallace W. Zane. “Spiritual Baptists in the Caribbean.” in Patsy Sutherland, Roy Moodley and Barry Chavannes, eds. Caribbean Healing Traditions. (New York: Routledge, 2014): 146; Colleen Ward and Michael Beaubrun. 1979. “Trance induction and hallucination in Spiritual Baptist mourning.” Journal of Psychological Anthropology, 2, no. 4 (1979): 479–488. |

| 24 | Patsy Sutherland, Roy Moodley, and Barry Chevannes. “Introduction” Caribbean Healing Traditions: Implications for Health and Mental Health. (Routledge, 2014): 4. |

| 25 | Stephen D. Glazier and Mary J. Hallen, “Health and Illness" in 21st Century Anthropology, H. James Birx, ed. Sage Reference, volume 2, 2010): 928. |

| 26 | Kumar Mahabir, “Traditional Medicines and Women Healers in Trinidad. (NALIS, 2022): 21. |

| 27 | See also, David H. Brown. “Conjure/Doctors: An Exploration of a Black Discourse in America, Antebellum to 1940.” Folklore Forum, 1990. |

| 28 | Martin A. Tsang, “The Art of Sweeping Sickness and Catching Death,” 311. |

| 29 | J. Brent Crosson, Experiments with Power: Obeah and the Remaking of Religion in Trinidad (University of Chicago Press, 2020): 262. |

| 30 | Michael Atwood Mason, “Baba Who? Babalú! Blog,” 2009. http://baba-who-babalu-santeria.blogspot.com/

|

| 31 | Martin A. Tsang, "The Art of Sweeping Sickness and Catching Death," 296. |

| 32 | Elizabeth Pérez. “A subjective response to ‘transitional phenomena’ and case study of chinoiseries in “Afro-Cuban” religions.” Religion, 55 no 2 (2025): 525–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2024.2444131; Steven M. Friedson. Remains of Ritual: Northern Gods in a Southern Land. (University of Chicago Press, 2009). |

| 33 | Judy Rosenthal. Possession, Ecstasy, and Law in Ewe Voodoo. (University of Virginia Press, 1999). |

| 34 | Katherine J. Hagedorn, Divine Utterances: The Performance of Afro-Cuban Santería. (Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001). |

| 35 | David H. Brown, Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion. (University of Chicago Press, 2003): 142. |

| 36 | David H. Brown “Thrones of the Orichas: Afro-Cuban Altars in New Jersey, New York, and Havana.” African Arts 26, no. 4 (1993): 44–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/3337075. See also, David H. Brown, Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual, and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion. (University of Chicago Press, 2003). |

| 37 | William Russell Bascom, Ifa Divination: Communication Between Gods and Men in West Africa (Indiana University Press, 1991). |

| 38 | F. Aiyejina and Rawle Gibbons, “Orisa (Orisha) Tradition in Trinidad.” Caribbean Quarterly, 45 no. 4 (1999):, 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00086495.1999.11671867; Nicole Fadeke Castor, “Shifting Multicultural Citizenship: Trinidad Orisha Opens the Road. “Cultural Anthropology, 28 (2013): 475-489. https://doi.org/10.1111/cuan.12015; Nicole Fadeke Castor. Spiritual Citizenship: Transnational Pathways from Black Power to Ifá in Trinidad (Duke University Press, 2017). |

| 39 | Jacob K. Olupona and Rowland O. Abiodun, eds. Ifá Divination, Knowledge, Power, and Performance (Indiana University Press, 2016). http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1b7x4sw; Katherine J. Hagedorn, Divine Utterances: The Performance of Afro-Cuban Santería (Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001). |

| 40 | Only Babalu’s followers recognize his grunts and stomps. |

| 41 | Nicole Fedeke Castor. Spiritual Citizenship: Transnational Pathways from Black Power to Ifá in Trinidad (Duke University Press, 2017). |

| 42 | Martin A. Tsang, “Write into Being: The Production of the Self and Circulation of Ritual Knowledge in Afro-Cuban Religious Libretas.” Material Religion 17 no. 2 (2021): 228–61. doi:10.1080/17432200.2021.1897282 |

| 43 | Raul J. Canizares. Babalu-Aye: Santeria and the Lord of Pestilence. (Original Publishers, 2000). |

| 44 | George Brandon. Santeria from Africa to the New World: The Dead Sell Memories (Indiana University Press, 1997). |

| 45 | Maureen Warner-Lewis, Trinidad Yoruba: From Mother Tongue to Memory (University of Alabama Press, 1996): 242n. |

| 46 | In Santeria, blood sacrifice is central to initiation ceremonies and symbolizes rebirth. Sacrificial blood establishes a connection between the initiate and orisas. Blood sacrifice is considered the most effective way to avert negative influences and provide protection for initiates. |

| 47 | David M/ O’Brien. Animal Sacrifice and Religious Freedom: Church of the Lacumi Babsalu-Aye in the City of Hialeah; See also David Maurice Aelion. "Freedom of Religion: A Case Study of the Church of Lukumí Babalú Ayé v. City of Hialeah, 2010. FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1105. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1105

|

| 48 | Blood sacrifice has very different meanings depending on one’s life experiences. My Spiritual Mother killed and dressed multiple chickens each week to feed her family. I buy chicken wrapped in plastic at the supermarket. Seeing an animal ritually slaughtered is a very different experience from buying meat at the supermarket. Both acts entail the death of an animal. |

| 49 | Stephen D. Glazier, "Wither Sango? An Inquiry into Sango's 'Authenticity' and Prominence in the Caribbean." in Sango in Africa and the African Diaspora. eds. Joel E. Tishken, Toyin Falola, and A. Akinyemi (Indiana University Press, 2009): 233–247. |

| 50 | Lydia Cabrera. El Monte: Notes on the Religions, Magic, Superstitions, and Followers of the Black and Creole People of Cuba. trans. David Font-Navarrete. Duke University Press (2023/1954): 157; Eerwan Dianteill and Martha Swearingen. “From Hierography to Ethnography and Back: Lydia Cabrera’s Texts and the Written Tradition in Afro-Cuban Religions.” The Journal of American Folklore 116, no. 461 (2003): 273–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4137792. |

| 51 | Lydia Cabrera, El Monte: Notes on the Religions, Magic, Superstitions, and Followers of the Black and Creole People of Cuba, 157. |

| 52 | Stephen D. Glazier, “African Cults and Christian Churches in Trinidad: The Spiritual Baptist Case” Journal of Religious Thought, 39, no. 2 (1979): 17-26. Some Trinidad Spiritual Baptists are exclusively Spiritual Baptists – they have no orisa connections. Some Spiritual Baptists – like my Spiritual Mother -- also follow the orisa.

|

| 53 | Many of these same plants are used throughout the Americas. See Robert A. Voeks, Sacred Leaves of Candomblé: African Magic, Medicine, and Religion in Brazil, (University of Texas Press, 1997). |

| 54 | Maarit Forde, "The Moral Economy of Spiritual Work: Money and Rituals in Trinidad and Tobago." in Obeah and Other Powers: The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing. eds. Maarit Forde and Diana Patton. (Duke University Press, 2012): 190-219. Bush work is not considered Obeah in Trinidad because money, the major legal criteria for Obeah, does not play a central role in these exchanges. |

| 55 | As Lévi-Strauss noted in The Savage Mind (University of Chicago Press,1966) :233–234), “Yoruba allow themselves to” annul the possible effects of historical factors upon their equilibrium and continuity in a quasi-automatic fashion, and their image of themselves is an essential part of their reality.” See also Peter J. Dixon “Uneasy Lies the Head: Politics, Economics, and the Continuity of Belief among Yoruba of Nigeria,” Comparative Studies in Society and History,33, no 1 (1991 :56-85. doi:10.1017/S0010417500016868. |

| 56 | Karen Richman. Migration and Vodou, (University Press of Florida, 2007). |

| 57 | David H. Brown, “Thrones of the Orichas: Afro-Cuban Altars in New Jersey, New York, and Havana.” African Arts 26, no. 4 (1993): 44–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/3337075. |

| 58 | George Brandon, Light from the forest: How Santería heals through plants. (Blue Unity Press, 1991). |

| 59 | Jake Wumkes,.“ The Spirit of the Pluriverse: Africana Spirit-Based Epistemologies and Interepistemic Thinking,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 91, no. 4, (2023): 737–756, https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfae028

|

| 60 | Yvonne Daniel, Caribbean and Atlantic Diaspora Dance: Igniting Citizenship (University of Illinois Press, 2011). |

| 61 | McKenzie, Peter. 1997. Hail Orisha! A Phenomenology of a West African Religion in the Mid-Nineteenth |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).