Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses and Cell Lines

2.2. Mouse Breeding and Infection Studies

2.3. Infection of Primary Mouse Kidney Cells

2.4. Ocular Swabs, TG Plaque Assays, and Explant-Induced Reactivation

2.5. Reverse Transcription and Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

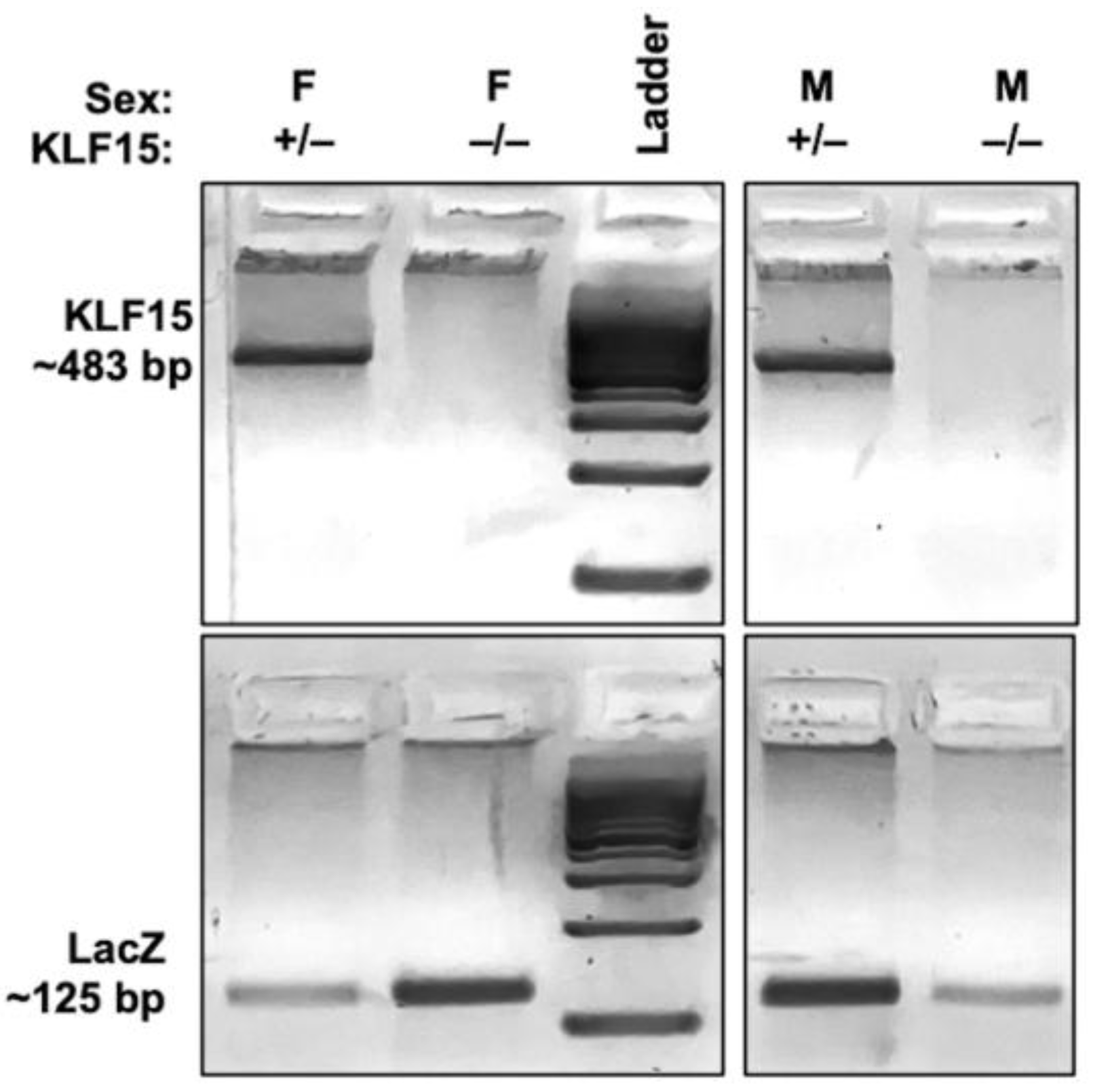

3.1. Generation and Validation of KLF15 Knockout Mice

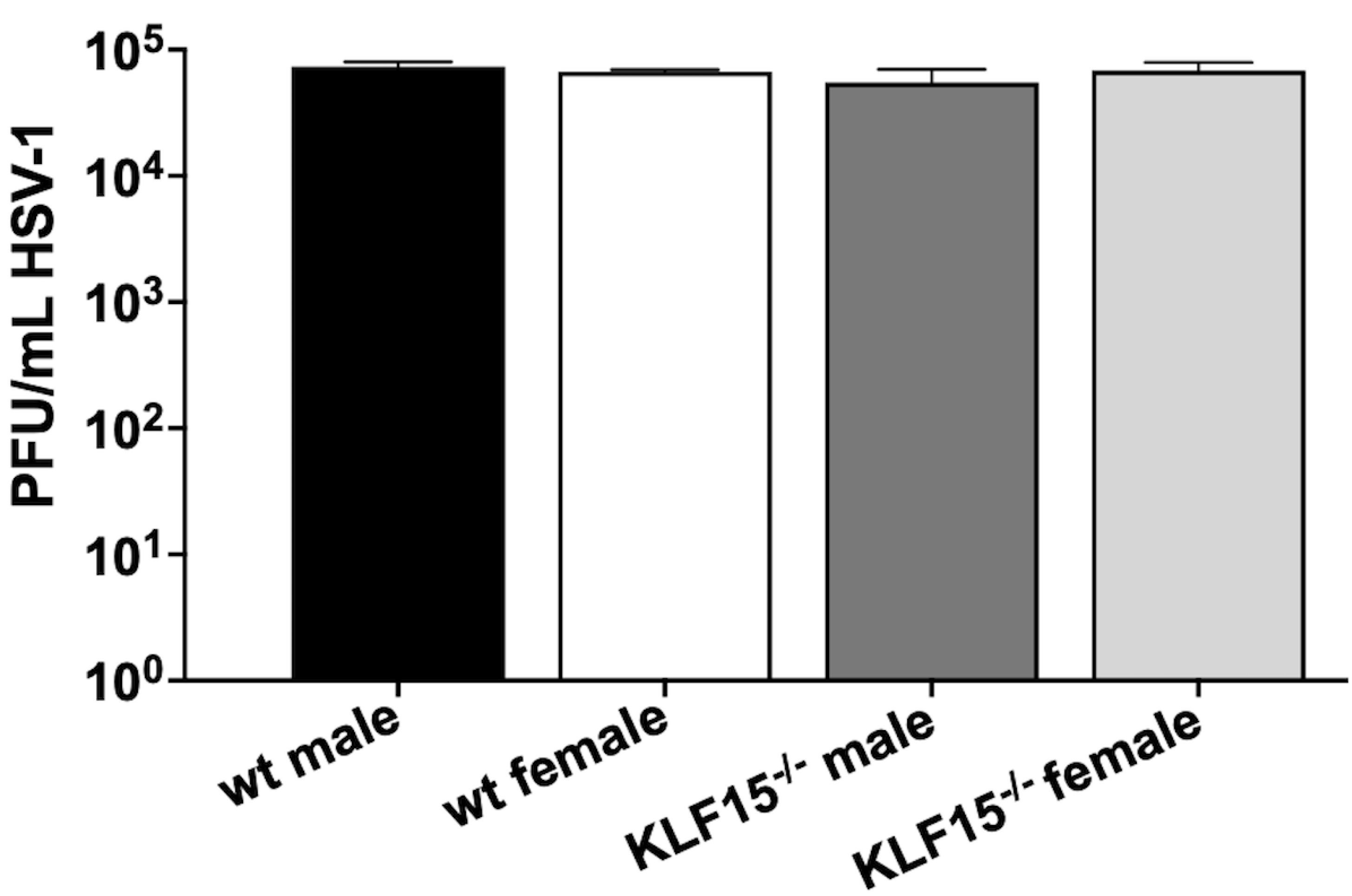

3.2. Examination of HSV-1 Replication in Primary Kidney Cells from KLF15–/– Mice

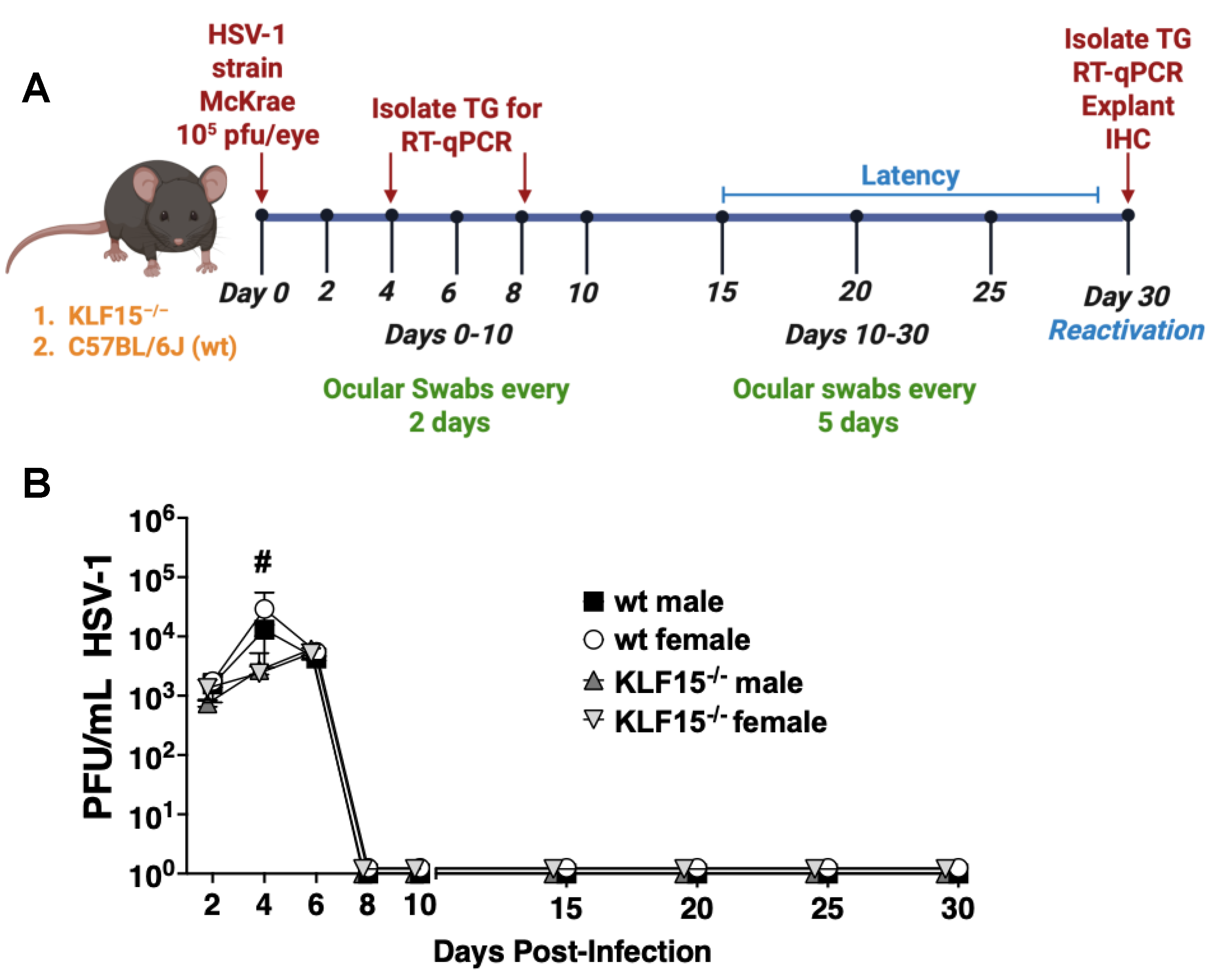

3.3. HSV-1 Replication Is Impaired During Acute Infection of KLF15–/– Mutant Mice when Comapred to wt Mice

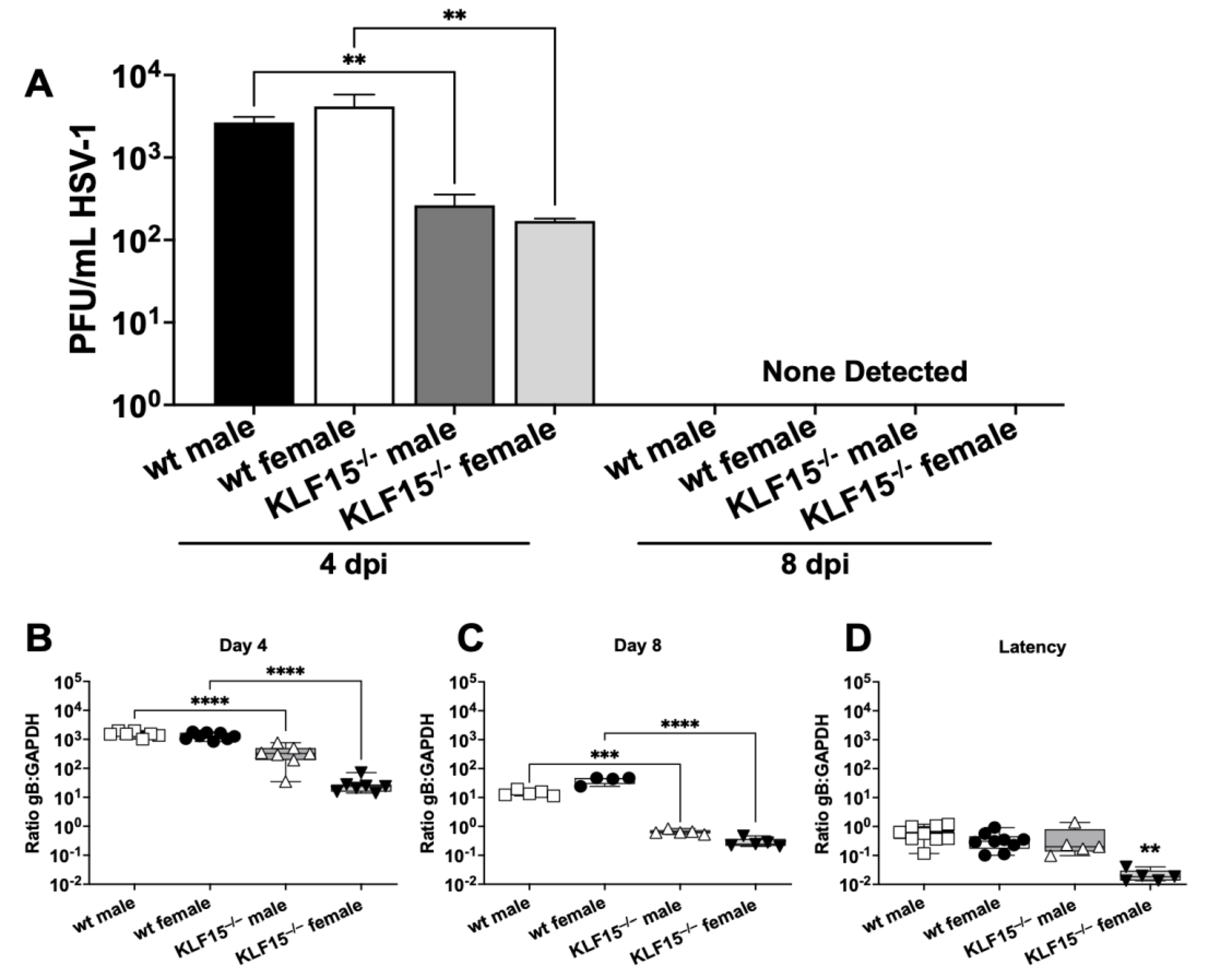

3.4. Comparison of infectious virus and total viral DNA in TG of wt versus KLF15–/– mice after infection

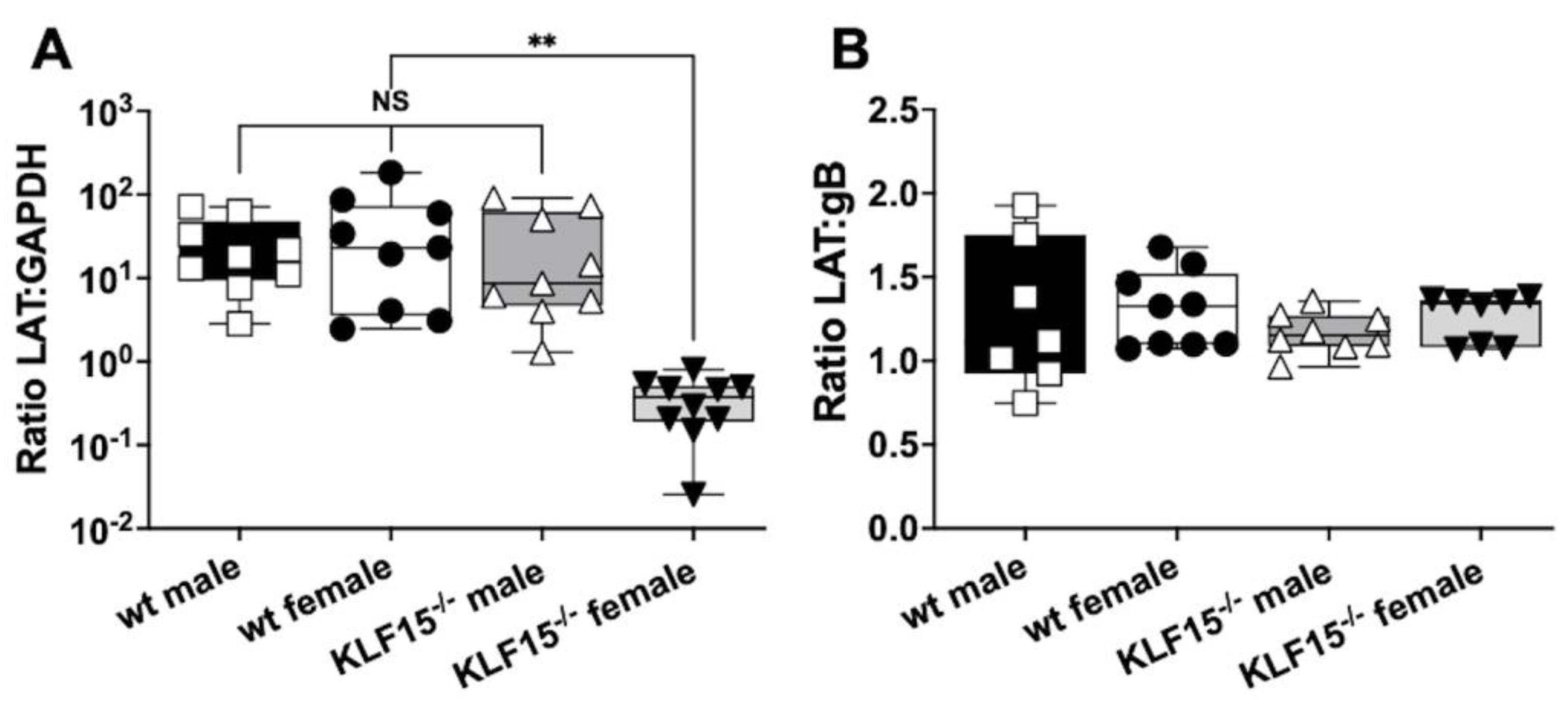

3.5. Analysis of LAT RNA in Latently Infected wt and KLF15–/– Female Mice

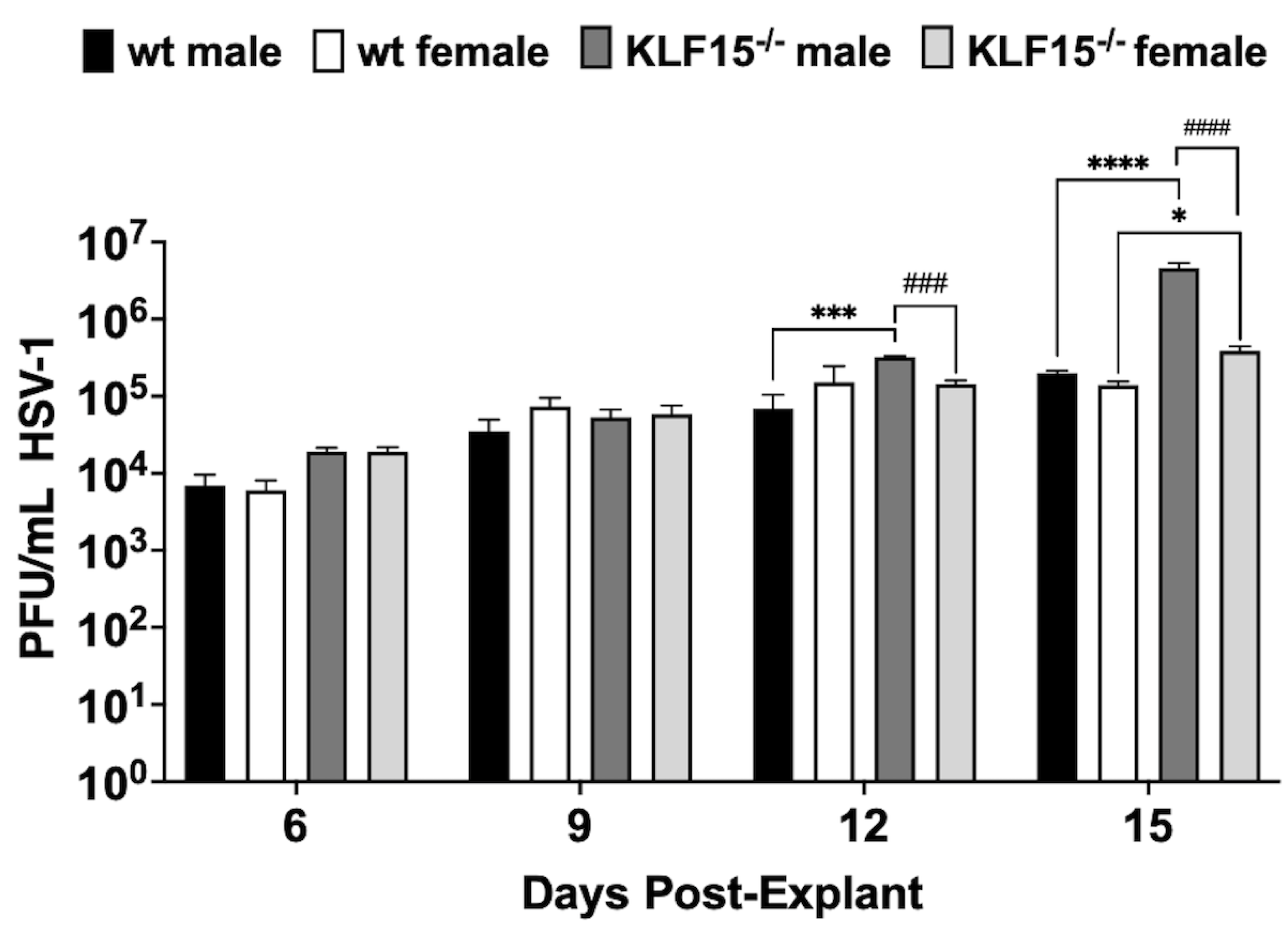

3.6. Analysis of Explant-Induced Reactivation from Latency

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Fraser, N.W.; Lawrence, W.C.; Wroblewska, Z.; Gilden, D.H.; Koprowski, H. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA in human brain tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981, 78, 6461–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, C.C.; Wohlenberg, C.; Openshaw, H.; Ray-Mendez, M.; Puga, A.; Notkins, A.L. Herpes simplex virus DNA sequences in the CNS of latently infected mice. Nature. 1980, 288, 228–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, D.L.; Fraser, N.W. Detection of HSV-1 genome in central nervous system of latently infected mice. Nature. 1983, 302, 523–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, G.C. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000, 34, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduino, P.G.; Porter, S.R. Herpes Simplex Virus Type I infection: overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008, 37, 107–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, R.J.; Kimberlin, D.W.; Roizman, B. Herpes simplex viruses. Clin Infect Dis. 1998, 26, 541–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; McDonald, H.R.; Nesburn, A.B.; Minckler, D.S. Penetrating keratoplasty: changing indications, 1947 to 1978. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980, 98, 1226–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan-Langston, D. Herpes simplex of the ocular anterior segment. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis. 2000, 20, 298–324. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, N.H. Ocular herpes simplex. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008, 2008, 0707. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Aguas, M.; Robaei, D.; McCluskey, P.; Watson, S. Clinical translation of recommendations from randomized trials for management of herpes simplex virus keratitis. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 2018, 46, 1008–16. [Google Scholar]

- Skoldenberg, B. Herpes simplex encephalitis. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1991, 80, 40–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stahl, J.P.; Mailles, A.; Dacheux, L.; Morand, P. Epidemiology of viral encephalitis in 2011. Medecine et maladies infectieuse. 2011, 41, 453–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Kameyama, T.; Nagaya, S.; Hashizume, Y.; Yoshida, M. Relapsing herpes simplex encephalitis: pathological confirmation of viral reactivation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002, 74, 262–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantalaiho TFårkkilå, N.; Vaheri, A.; Koskiniemi, M. Acute encephalitis from 1967 to 1991. J Neurol Sci. 2001, 184, 169–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, A.; Johnston, C. Treatment and prevention of herpes simplex virus type 1 in immunocompetent adolescents and adults. The South African General Practitioner. 2024, 5, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Sharma, S.; Akojwar, N.; Dondulkar, A.; Yenorkar, N.; Pandita, D.; et al. An Insight into Current Treatment Strategies, Their Limitations, and Ongoing Developments in Vaccine Technologies against Herpes Simplex Infections. Vaccines (Basel). 2023, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Wald, A.; Krantz, E.; Selke, S.; Warren, T.; Vargas-Cortes, M.; et al. Valacyclovir and Acyclovir for Suppression of Shedding of Herpes Simplex Virus in the Genital Tract. J Infect Dis. 2004, 190, 1374–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, J.M.; Kader, M.; DeLuca, N.A. Transcription of the Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Genome during Productive and Quiescent Infection of Neuronal and Nonneuronal Cells. J Virol. 2014, 88, 6847–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, O.O.; MacGibeny, M.A.; Enquist, L.W. Latent versus productive infection: the alpha herpesvirus switch. Future Virology. 2018/05/22 ed. 2018, 13, 431–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouwendijk, W.J.D.; Dekker, L.J.M.; van den Ham, H.J.; Lenac Rovis, T.; Haefner, E.S.; Jonjic, S.; Haas, J.; Luider, T.M.; Verjans, G.M. Analysis of Virus and Host Proteomes During Productive HSV-1 and VZV Infection in Human Epithelial Cells. Front Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thompson, R.L.; Sawtell, N.M. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript gene regulates the establishment of latency. J Virol. 1997, 71, 5432–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.L.; Sawtell, N.M. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency associated transcript locus is required for the maintenance of reactivation competent latent infections. J Neurovirology. 2011, 17, 552–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perng, G.C.; Jones, C. Towards an understanding of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-reactivation cycle. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2010 Feb 02/20 ed. 2010, 2010, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, D.; Barrozo, E.R.; Bloom, D.C. HSV1 latent transcription and non-coding RNA: A critical retrospective. J Neuroimmunology. 2017, 308(March):65, 67,71-66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C. Intimate Relationship Between Stress and Human Alpha-Herpes Virus 1 (HSV-1) Reactivation from Latency. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep. 2023, 10, 236–245, Epub 2023 Jul 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jones, C. Reactivation from latency by alpha-herpesvirinae subfamily members: a stressful situation. Curr Topics Virol. 2014, 12, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley RH and JA Cidlowski. The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: New signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013, 132, 1033–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.S.; Zhu, L.; Thunuguntla, P.; Jones, C. Antagonizing the glucocorticoid receptor impairs explant-induced reactivation in mice latently infected with herpes simplex virus 1. J Virol. 2019, JVI.00418-19. [Google Scholar]

- Halford, W.P.; Gebhardt, B.M.; Carr, D.J. Mechanisms of herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivation. J Virol. 1996 Aug 08/01 ed. 1996, 70, 5051–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Zhou, G.; Roizman, B.; Du, G. Zhou, and B. Roizman T. Induction of apoptosis accelerates reactivation from latent HSV-1 in ganglionic organ cultures and replication in cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012, 109, 14616–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieker, J.J. Krüppel-like factors: three fingers in many pies. J Biological Chemistry. 2001, 276, 34355–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, B.B.; Yang, V.W. Mammalian Krüppel-like factors in health and diseases. Physiol Rev. 2010, 90, 1337–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuce, K.; Ozkan, A.I. The krüppel-like factor (KLF) family, diseases, and physiological events. Gene. 2024, 895, 148027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, S.K.; Mailloux, C.M.; Barczak, A.J.; Wang, Q.; Altonsy, M.O.; Jain, M.K.; et al. The glucocorticoid receptor and KLF15 regulate gene expression dynamics and integrate signals through feed-forward circuitry. Molec and Cellular Biol. 2013, 33, 2104–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisch, S.; Gray, S.; Heymans, S.; Haldar, S.M.; Wang, B.; Pfister, O.; et al. Krüppel-like factor 15 is a regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104, 7074–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Sakaue, H.; Iguchi, H.; Gomi, H.; Okada, Y.; Takashima, Y.; et al. Role of Kruppel-like factor 15 (KLF15) in transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280, 12867–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Kuo, C.; Watanabe, M.; Charles, H.; Feinberg, M.; Jain, M. Role of Klf15, a novel Kruppel-like factor, in regulating smooth muscle cell growth and differentiation. Circulation. 2001, 104, 90–90. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, N.; Yoshikawa, N.; Ito, N.; Maruyama, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Takeda, S.; et al. Crosstalk between Glucocorticoid Receptor and Nutritional Sensor mTOR in Skeletal Muscle. Cell Metabolism. 2011, 13, 170–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesekera, N.; Hazell, N.; Jones, C. Independent Cis-Regulatory Modules within the Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infected Cell Protein 0 (ICP0) Promoter Are Transactivated by Krüppel-like Factor 15 and Glucocorticoid Receptor. Viruses. 2022, 14, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostler, J.B.; Harrison, K.S.; Schroeder, K.; Thunuguntla, P.; Jones, C. The glucocorticoid receptor (GR) stimulates Herpes Simplex Virus 1 productive infection, in part because the infected cell protein 0 (ICP0) promoter is cooperatively transactivated by the GR and Krüppel-like transcription factor 15. J Virol. 2019 Mar 01/04 ed. 2019.

- Ostler, J.B.; Thunuguntla, P.; Hendrickson, B.Y.; Jones, C. Transactivation of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1) Infected Cell Protein 4 Enhancer by Glucocorticoid Receptor and Stress-Induced Transcription Factors Requires Overlapping Krüppel-Like Transcription Factor 4/Sp1 Binding Sites. J Virol. 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostler, J.B.; Jones, C. Stress Induced Transcription Factors Transactivate the Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infected Cell Protein 27 (ICP27) Transcriptional Enhancer. Viruses. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mayet, F.S.; Harrison, K.S.; Jones, C. Regulation of Krüppel-Like Factor 15 Expression by Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 or Bovine Herpesvirus 1 Productive Infection. Viruses. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S. M.W. Feinberg, S. Hull, C.T. Kuo, M. Watanabe, S.S. Banerjee, A. DePina, R. Haspel, and M.K. Jain. The Krüppel-like Factor KLF15 Regulates the Insulin-sensitive Glucose Transporter GLUT4. J of Biological Chemistry. 2002, 277, 34322–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecker, J.; Froberg-Fejko, K. Using environmental enrichment and nutritional supplementation to improve breeding success in rodents. Lab Animal. 2016, 45, 406–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truett, G.E.; Heeger, P.; Mynatt, R.L.; Truett, A.A.; Walker, J.A.; Warman, M.L. Preparation of PCR-quality mouse genomic DNA with hot sodium hydroxide and tris (HotSHOT). Biotechniques. 2000, 29, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.S.; Zhu, L.; Thunuguntla, P.; Jones, C. Herpes simplex virus 1 regulates β-catenin expression in TG neurons during the latency-reactivation cycle. PloS one. 2020, 15, e0230870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, K.S.; Wijesekera, N.; Robinson, A.G.J.; Santos, V.C.; Oakley, R.H.; Cidlowski, J.A.; Jones, C. Impaired glucocorticoid receptor function attenuates herpes simplex virus 1 production during explant-induced reactivation from latency in female mice. J Virol. 2023, 97, e0130523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildyard, J.C.W.; Wells, D.J.; Piercy, R.J. Identification of qPCR reference genes suitable for normalising gene expression in the developing mouse embryo. Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 6, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.S.; Cowan, S.R.; Jones, C. Murine nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) harbors human alphaherpesvirus 1 (HSV-1) DNA during latency, and dexamethasone triggers viral replication. J Virol. 2025, 99, e0225124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, G. Herpes simplex type 1 infects and establishes latency in the brain and trigeminal ganglia during primary infection of the lip in cotton rats and mice. Arch Virol. 2002, 147, 167–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.H.; Gu, B.; Person, S. Role of glycoprotein B of herpes simplex virus type 1 in viral entry and cell fusion. J Virol. 1988, 62, 2596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C. Alphaherpesvirus latency: its role in disease and survival of the virus in nature. Adv Virus Res. 1998, 51, 81–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; West, C.; Norton-Wenzel, C.S.; Rej, R.; Davis, F.B.; Davis, P.J.; et al. Effects of resin or charcoal treatment on fetal bovine serum and bovine calf serum. Endocr Res. 2009, 34, 101–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Fiandalo, M.V.; Pop, E.; Stocking, J.J.; Azabdaftari, G.; Li, J.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Charcoal-Stripped Fetal Bovine Serum Reveals Changes in the Insulin-like Growth Factor Signaling Pathway. J Proteome Res. 2018, 17, 2963–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.R.; Qu, L.H.; Ma, L.M. Differential impacts of charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum on c-Myc among distinct subtypes of breast cancer cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020, 526, 267–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perng, G.C.; Jones, C.; Ciacci-Zanella, J.; Stone, M.; Henderson, G.; Yukht, A.; Slanina, S.M.; Hofman, F.M.; Ghiasi, H.; Nesburn, A.B.; Wechsler, S.L. Virus-induced neuronal apoptosis blocked by the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript. Science. 2000, 287, 1500–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galliher-Beckley, A.J.; Cidlowski, J.A. Emerging roles of glucocorticoid receptor phosphorylation in modulating glucocorticoid hormone action in health and disease. IUBMB Life. 2009, 61, 979–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.; Limaye, A.; Kulkarni, A.B. Overview: Generation of Gene Knockout Mice. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2009. Chapter:Unit-19.1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.L.M.; Price, E.M.; Mifsud, K.R.; Salatino, S.; Sharma, E.; Engledow, S.; et al. Genomic regulation of Krüppel-like-factor family members by corticosteroid receptors in the rat brain. Neurobiology of Stress. 2023, 23, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mifsud, K.R.; Kennedy, C.L.M.; Salatino, S.; Sharma, E.; Price, E.M.; Haque, S.N.; et al. Distinct regulation of hippocampal neuroplasticity and ciliary genes by corticosteroid receptors. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasse, S.K.; Zuo, Z.; Kadiyala, V.; Zhang, L.; Pufall, M.A.; Jain, M.K.; et al. Response Element Composition Governs Correlations between Binding Site Affinity and Transcription in Glucocorticoid Receptor Feed-forward Loops. J Biol Chem. 2015, 290, 19756–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Schönke, M.; Buurstede, J.C.; Moll, T.J.A.; Gentenaar, M.; Schilperoort, M.; et al. Sexual Dimorphism in Transcriptional and Functional Glucocorticoid Effects on Mouse Skeletal Muscle. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 907908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Elsarrag, S.Z.; Duan, Q.; LaGory, E.L.; Wang, Z.; Alexanian, M.; et al. KLF15 cistromes reveal a hepatocyte pathway governing plasma corticosteroid transport and systemic inflammation. Science Advances. 2022, 8, eabj2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.R.; Black, J.D.; Azizkhan-Clifford, J. Sp1 and Krüppel-like factor family of transcription factors in cell growth regulation and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2001, 188, 143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suske, G. The Sp-family of transcription factors. Gene. 1999, 238, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, J.; Cook, T.; Urrutia, R. Sp1- and Krüppel-like transcription factors. Genome Biology. 2003, 4, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mayet, F.S.; El-Habbaa, A.S.; D’Offay, J.; Jones, C. Synergistic Activation of Bovine Herpesvirus 1 Productive Infection and Viral Regulatory Promoters by the Progesterone Receptor and Krüppel-Like Transcription Factor 15. J Virol. 2018, 93, e01519–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-mayet, F.S.; Sawant, L.; Thunuguntla, P.; Jones, C. Combinatorial Effects of the Glucocorticoid Receptor and Krüppel-Like Transcription Factor 15 on Bovine Herpesvirus 1 Transcription and Productive Infection. J Virol. 2017, 91, e00904–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.C.; Ostler, J.B.; Harrison, K.S.; Jones, C. Slug, a stress-induced transcription factor, stimulates herpes simplex virus type 1 replication and transactivates a cis-regulatory module within the VP16 promoter. J Virol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).