1. Introduction

Obesity is a global health problem with a steadily increasing prevalence. It is associated with numerous cardiovascular complications, including the development of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), diastolic and systolic dysfunction of the left ventricle, as well as pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular (RV) dysfunction [

1,

2,

3,

5]. Surgical treatment of obesity, such as bariatric surgery, leads to significant weight reduction and may induce beneficial changes in cardiac structure and function [

1,

2,

4,

6]. This study aimed to assess early changes in left and right ventricular function after bariatric surgery based on echocardiographic data and to relate these findings to results reported in the literature.

2. Methods

We analyzed echocardiographic data of bariatric patients who underwent surgical obesity treatment. The study included 40 adult patients hospitalized at the Department of General, Oncological, and Endocrine Surgery between December 2022 and June 2023. One patient withdrew their consent, and finally 39 were included in the analysis. Inclusion criteria were BMI >35, performing bariatric surgery and echocardiographic examinations before and after surgery. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, postpartum period, alcohol dependence, and cancer.

Parameters of left and right ventricular function were assessed before surgery, and at 3 and 6 months postoperatively. All patients underwent standard transthoracic echocardiography via a GE Vivid E95 ultrasound diagnostic system equipped with an M5s 3.5–5 MHz transducer (GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Horten, Norway) by experienced sonographer. Two-dimensional, color Doppler, pulsed wave Doppler, and standard high-frame-rate (>60/s) apical 4-, 2- and 3-chamber views from five consecutive cycles were archived for offline analysis (EchoPAC version: 204, GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Norway). We evaluated left and right ventricular function parameters, including left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricle (LV) and right ventricle (RV) global longitudinal strain (GLS and GSRV), right ventricular free wall strain (FWSRV), peak early (e’) and late (a’) diastolic annular velocities (lateral and septal) with calculation of E/e’ ratios, left atrium volume index (LAVI), left atrial strain (LAS) including reservoir phase (LAS-r), conduit phase (LAS-cd) and contraction phase LAS-ct), tricuspid regurgitation velocity (TRV), tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), maximum systolic velocity of the lateral part of the tricuspid annulus- s’ and accelerated pulmonary time (AcT).

Left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were determined using the biplane Simpson method. The left atrial volume (LAV) was measured by averaging the values in the apical 4- and 2-chamber views, and then the LAV index (LAVI) was calculated.

Diastolic dysfunction was defined per ASE/EACVI guidelines [

7] to emphasize the identification of elevated LVEDP and the differentiation of diastolic dysfunction grades. The peak early and late diastolic mitral annular velocities (E and A, respectively) were measured by pulsed-wave Doppler, and the E/A ratio was then calculated. The peak early (e’) and late (a’) diastolic annular velocities were obtained by averaging the values at the septum and lateral positions using TDI, and then E/e’ was calculated. The TRV parameter was also used to assess left ventricular diastolic function.

Global longitudinal strain was determined from apical images by maximizing the frame rate (from 50 to 70 frames per second) by narrowing the sector to isolate individual walls. Apical 4-chamber, 3-chamber and 2-chamber views were obtained to assess the longitudinal strain in each wall at the basal, mid and apical level in each of these views. For each view, five cardiac cycles were recorded and saved digitally for further study. Automatic functional imaging (AFI) tracked the LV endocardial and epicardial boundaries in the three apical dynamic images. Tracking was accepted or rejected according to the quality of image. The global longitudinal strain of the left ventricle was calculated systematically from the average value of the three views, including 18 segments of the myocardium.

Left atrial strain measurements were performed using the apical 4-chamber and 2- chamber views. The left atrium was contoured automatically with manual correction. For each patient, strain during the reservoir phase (LAS-r), during the conduction phase (LAS-cd) and during the atrial contraction phase (LAS-ct) was calculate.

The conventional echocardiographic assessment of RV function of tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), maximum systolic velocity of the lateral part of the tricuspid annulus-s’ and accelerated pulmonary time (AcT) were measured according to current guidelines (7). The maximum amplitude was used for TAPSE measurement.

A RV focused four-chamber apical view was used to assess GSRV. The right ventricular endocardium was automatically contoured using AFI, with manual corrections.

Patient signed informed consent and the study was approved by the local bioethics committee (No 70/2021 from 30 November 2021).

Statistical Methods

Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to assess the significance of parameter changes over time. When the assumptions of this test were not met, the nonparametric Friedman test was applied as an alternative. Post hoc analyses included pairwise t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Relationships between changes in parameters and changes in body mass were evaluated using linear models, including hybrid within-between models and independent t-tests where appropriate. Linear mixed-effects models were not feasible due to the relatively small sample, which led to convergence issues. The hypothesis regarding the relationship between overall changes in right ventricular function and body mass was tested using multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) with Wilks’ lambda, supported by principal component analysis (PCA). A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The study group consisted of 32 women and 7 men aged 42.3 (±12) years. Among the comorbidities, arterial hypertension was the most common (43.59% of patients). The most commonly used type of procedure was sleeve gastrectomy (87.18%) (

Table 1).

3.1. Left Ventricular and Left Atrium Parameters

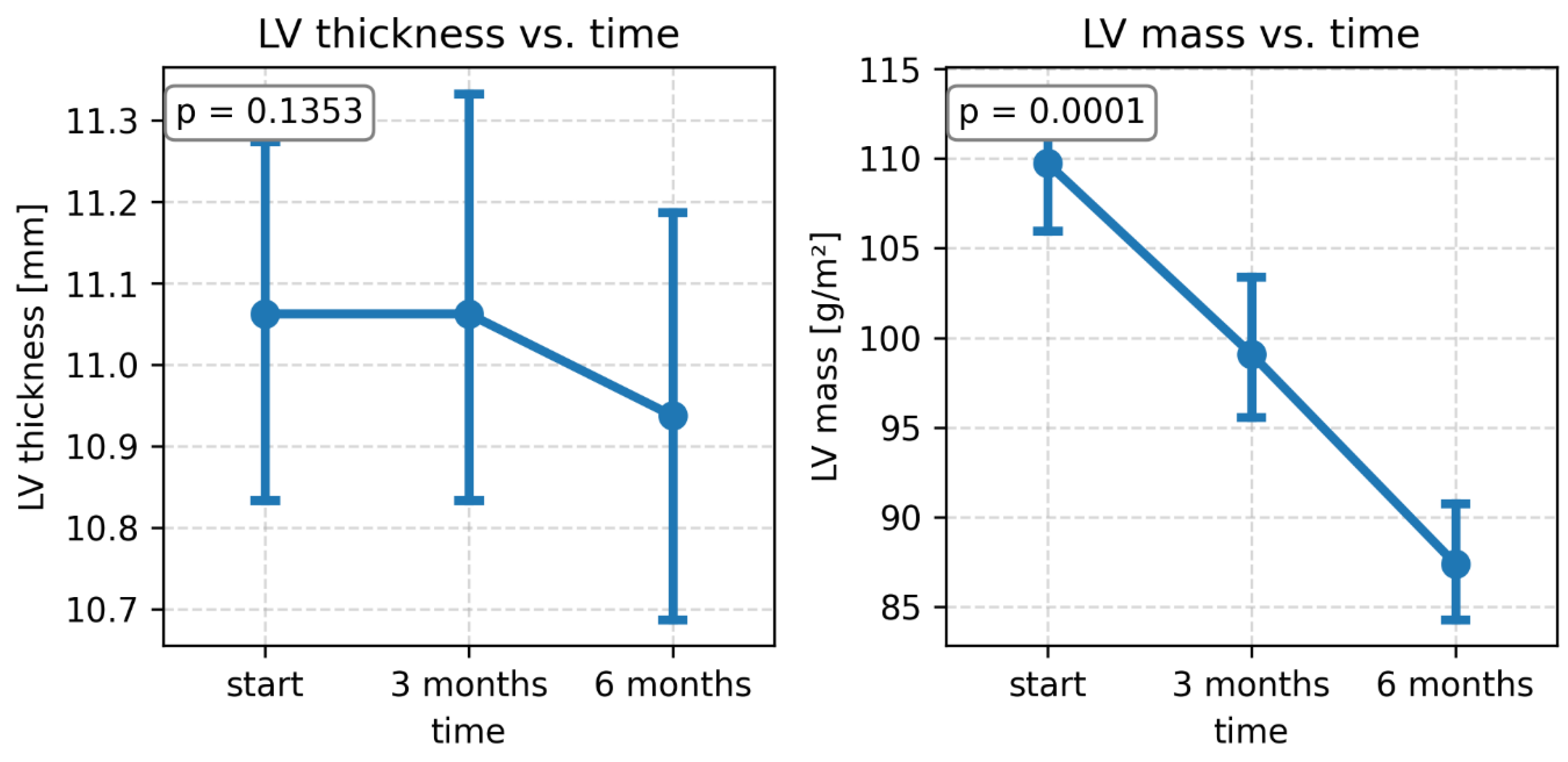

During the 3- and 6-month follow-up period after bariatric surgery, no significant changes in left ventricular thickness were observed, but a significant decrease in LV mass was observed (

Table 2,

Figure 1).

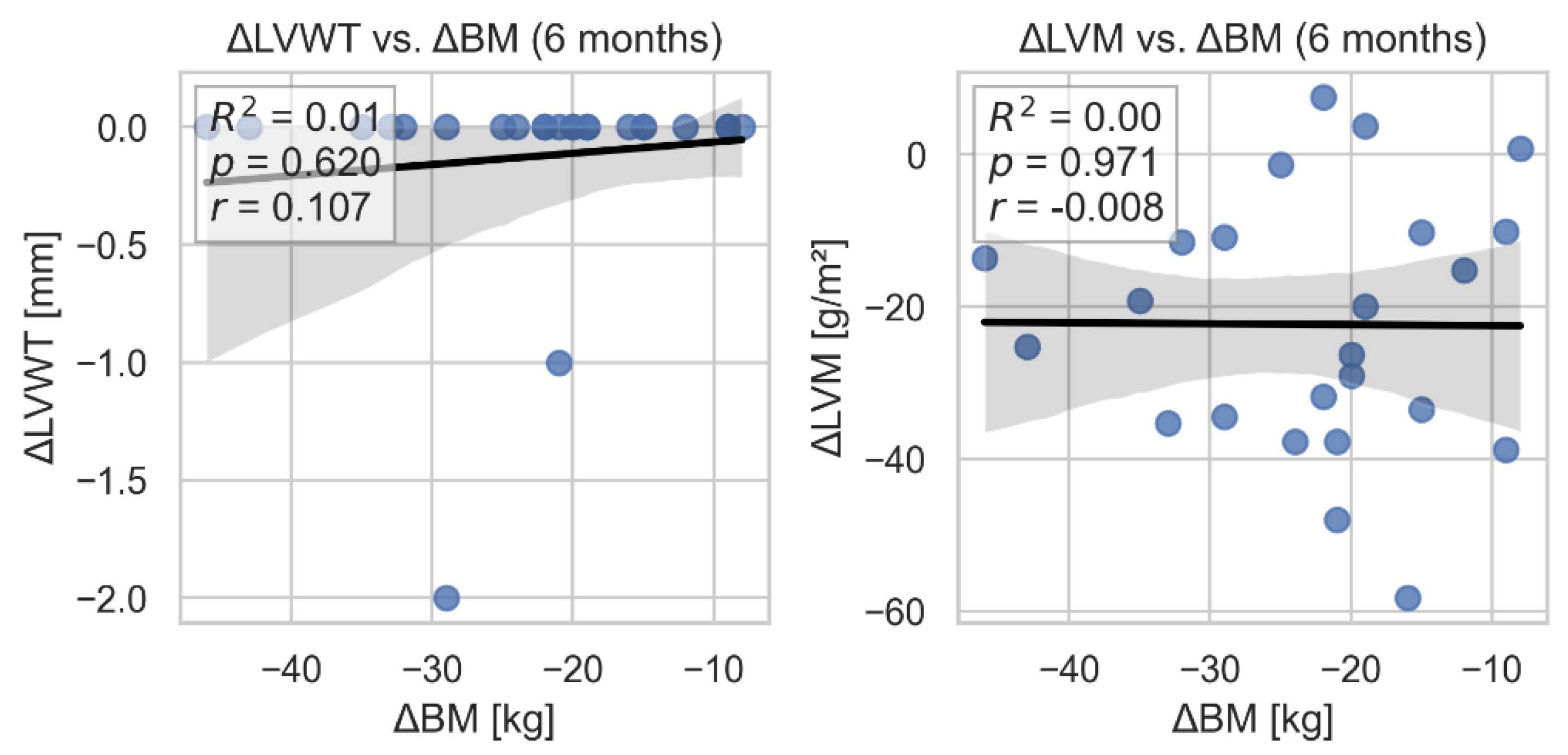

We found no statistically significant association between change in LV wall thickness (as well as change in LV mass) and body weight loss. (

Figure 2).

GLS significantly improved from -14.38±2.47 before surgery to -18.01±2.32 at 6 months (p=0.001). LVEF increased slightly from 59% to 61.3%, but this change was not statistically significant (p=0.167), however, a significant reduction in LVEDV was observed, especially after 3 months. No significant changes were observed in E/e’ sept and lat, e’ sept and lat, or LAVI. Analysis of left atrial strain parameters showed a significant improvement in LAS-r and LAS-cd components, with no significant changes in LAS-ct (

Table 2).

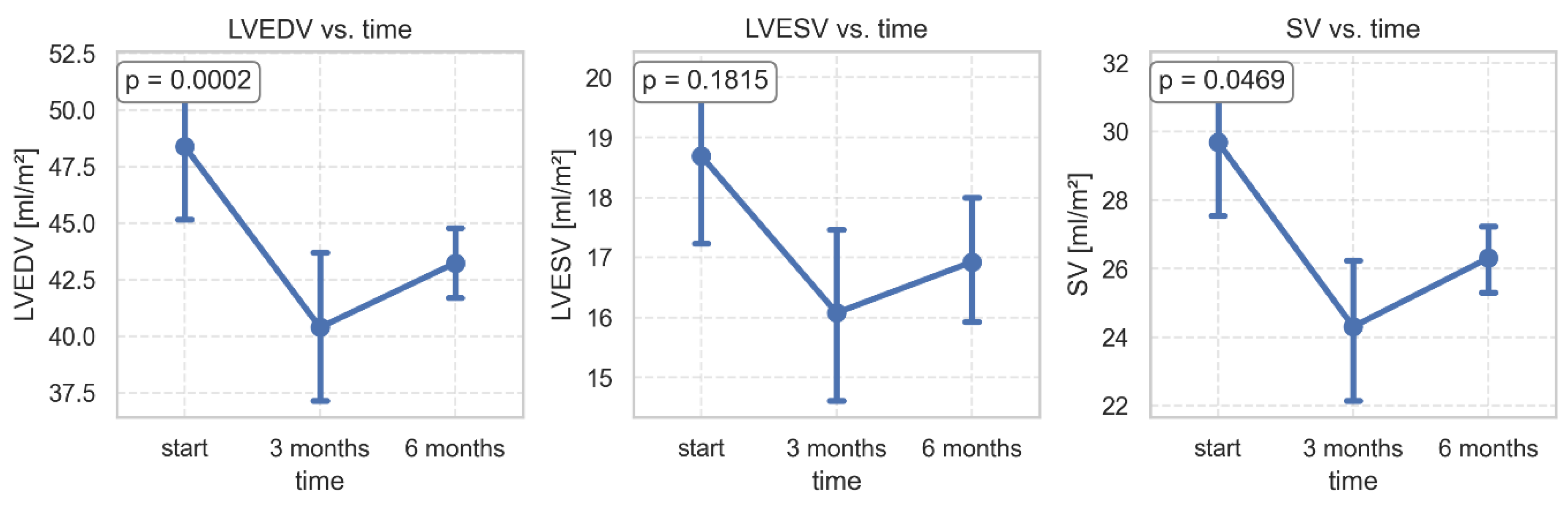

Significant changes were found in the volumetric parameters of the left ventricle. After 3 months of follow-up, LVEDV, LVESV, and SV decreased, while after 6 months, a slight increase in these parameters was observed (

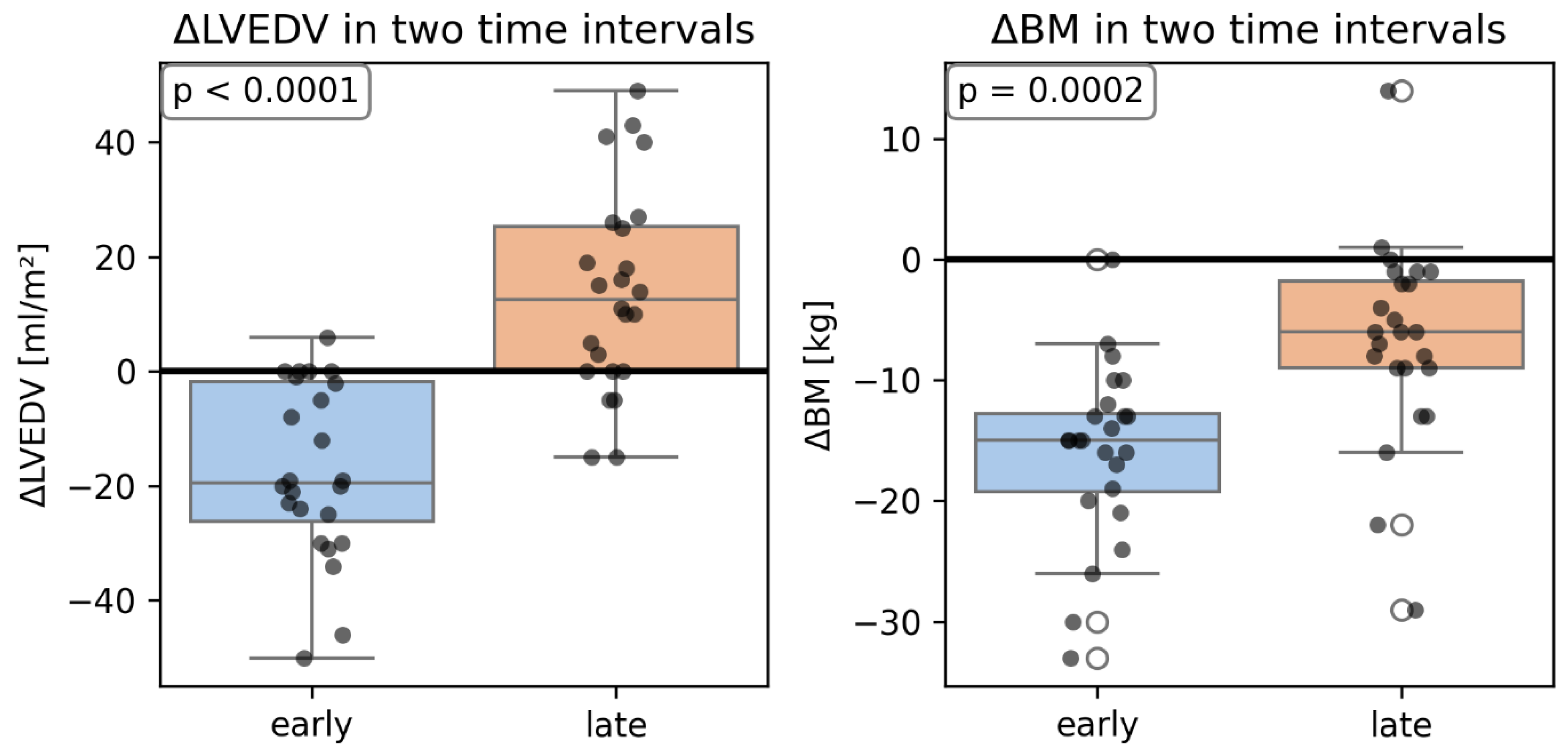

Figure 3). We did not find any significant relationship between changes in volumetric parameters of LV and change in body weight, but the within-between model revealed that after adjusting for changes in body mass, the change in LVEDV was significantly higher in the late period (from 3 months to 6 months after surgery) than in the early period (from baseline to 3 months after surgery) (

Figure 4).

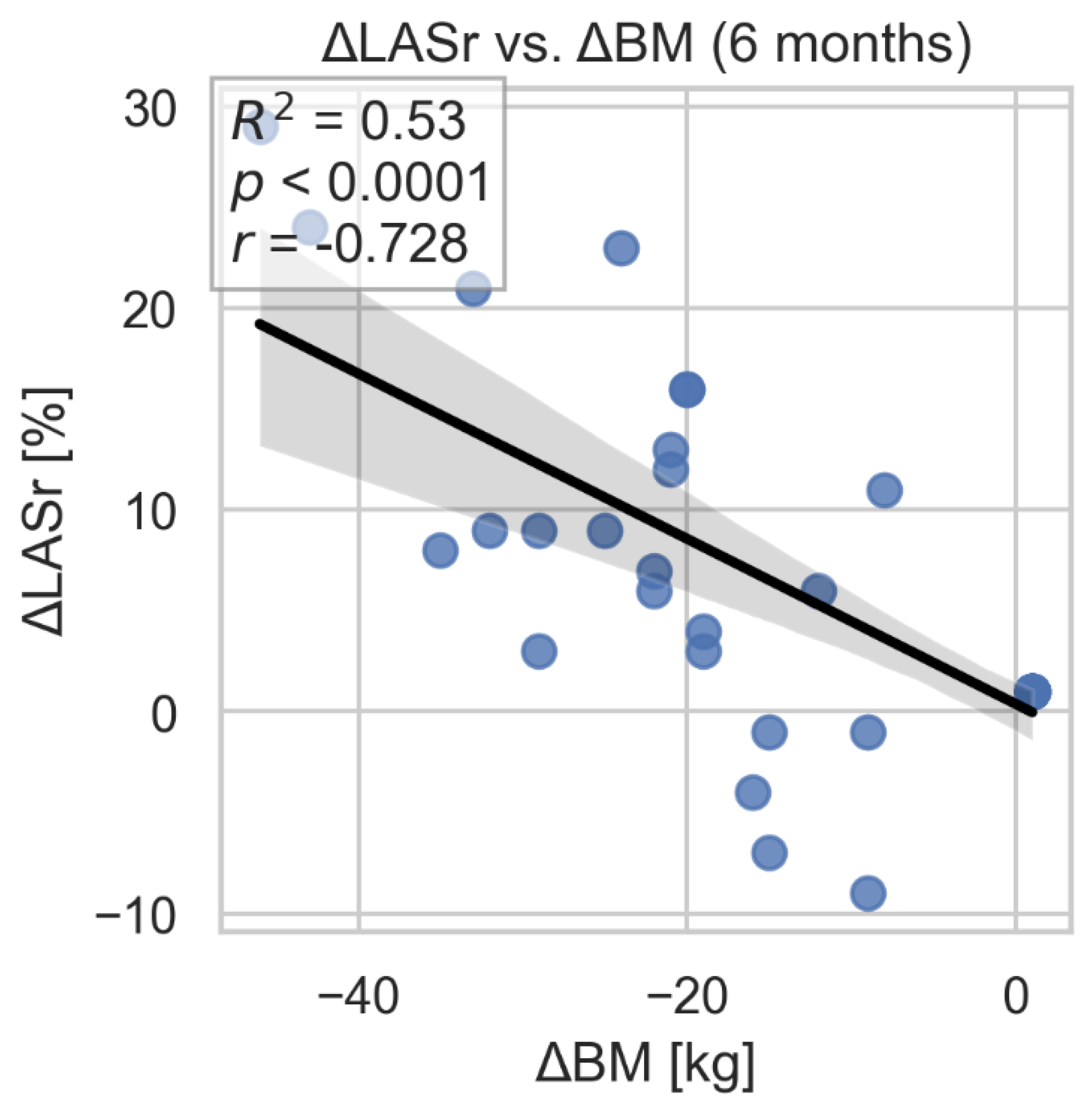

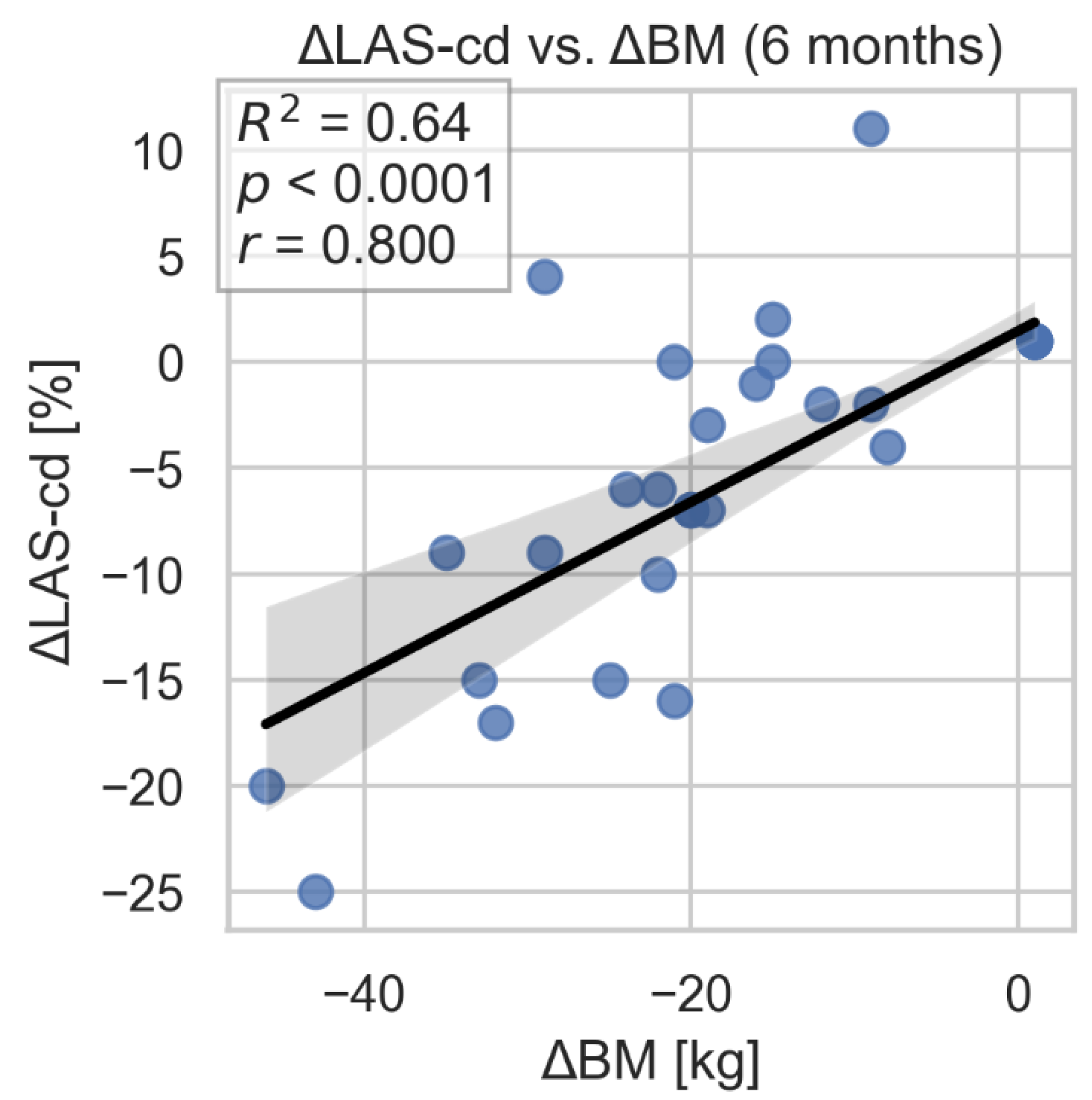

During the 3- and 6-month follow-up after bariatric surgery, significant improvement in left atrial strain parameters: LAS-r and LAS-cd were observed. We found statistically significant associations between 6-month changes in these parameters and the corresponding change in body weight. Of note, adjustment for time did not materially alter the statistical significance of the relationships (

Figure 5,

Figure 6). No significant changes were found in LAS-ct.

3.2. Right Ventricular Function

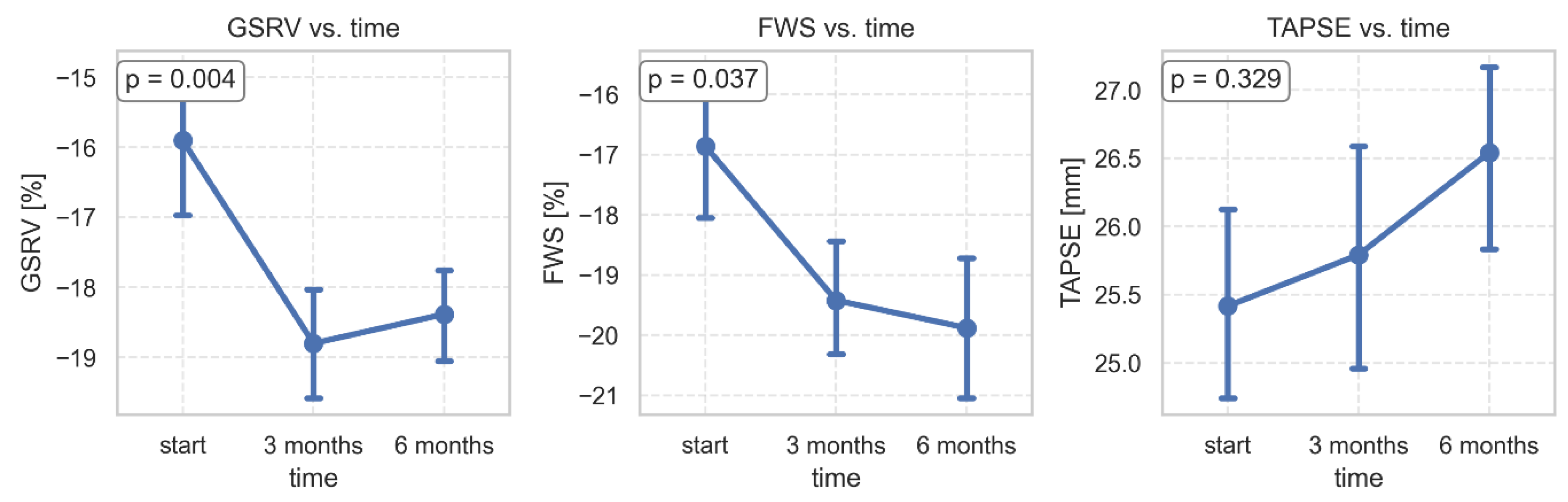

During the study period, GSRV and FWSRV changed significantly, while TAPSE did not show a significant change. GSRV increased significantly from -15.9±5.29 to -18.38±3.25 at 6 months (p=0.005). FWSRV improved from -16.9±6.17 to -19.5±5.18 (p=0.042). TRV max significantly decreased from 1.84±0.62 to 1.46±0.52 at 6 months (

Table 3,

Figure 7).

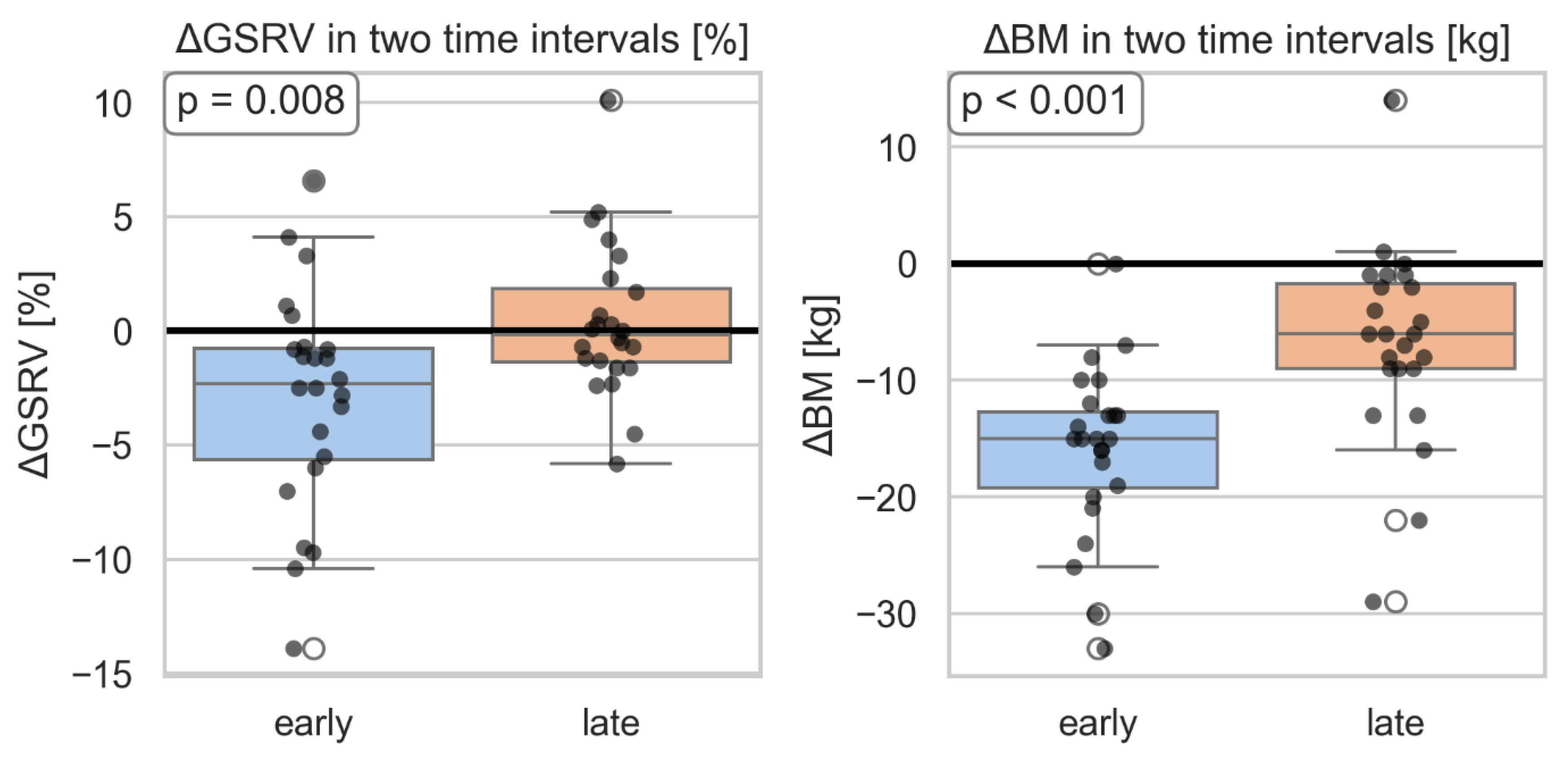

Additionally, a significantly greater change in GSRV was observed in the second time interval compared to the first period, adjusted for change in body weight. (

Figure 8).

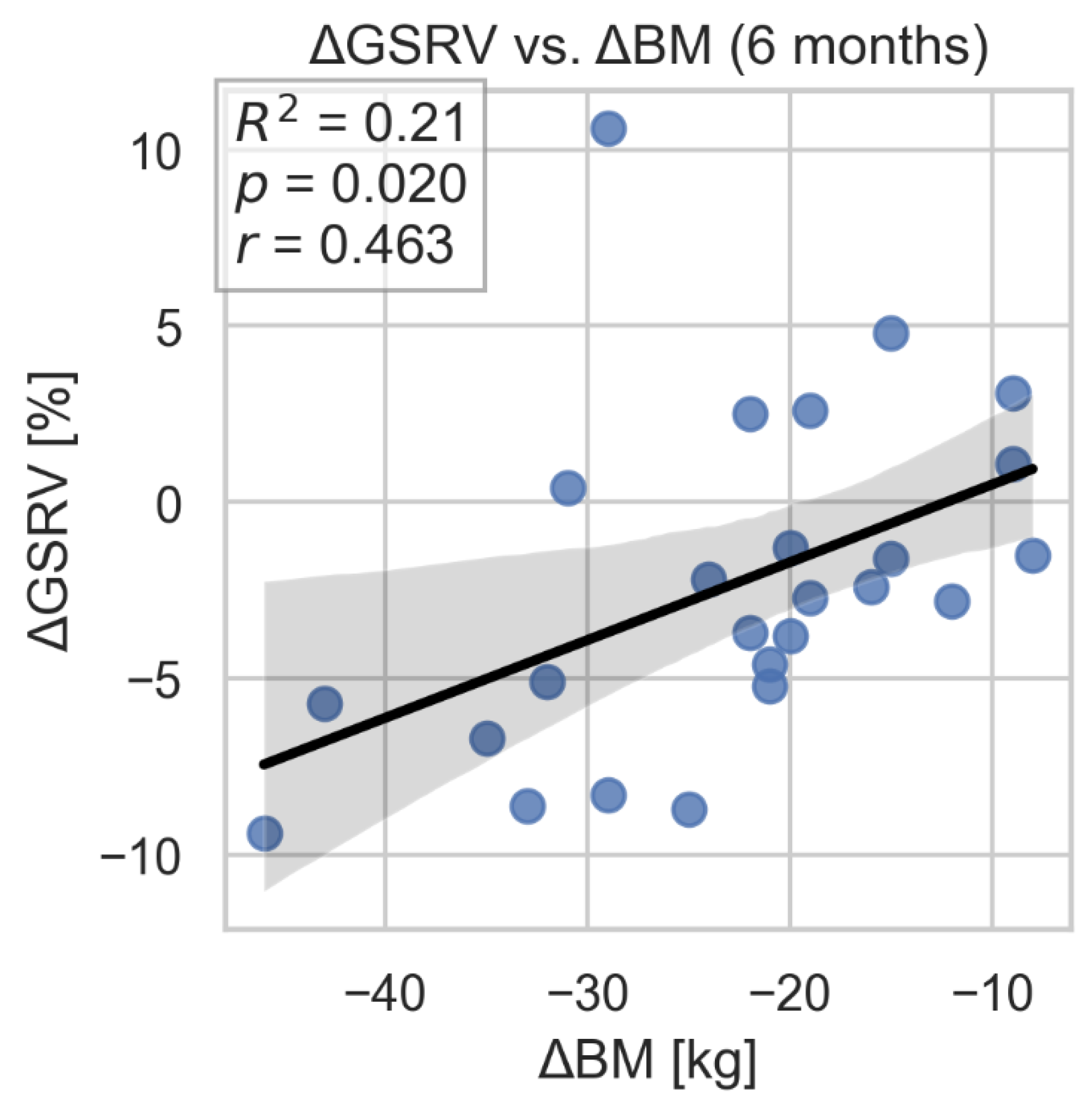

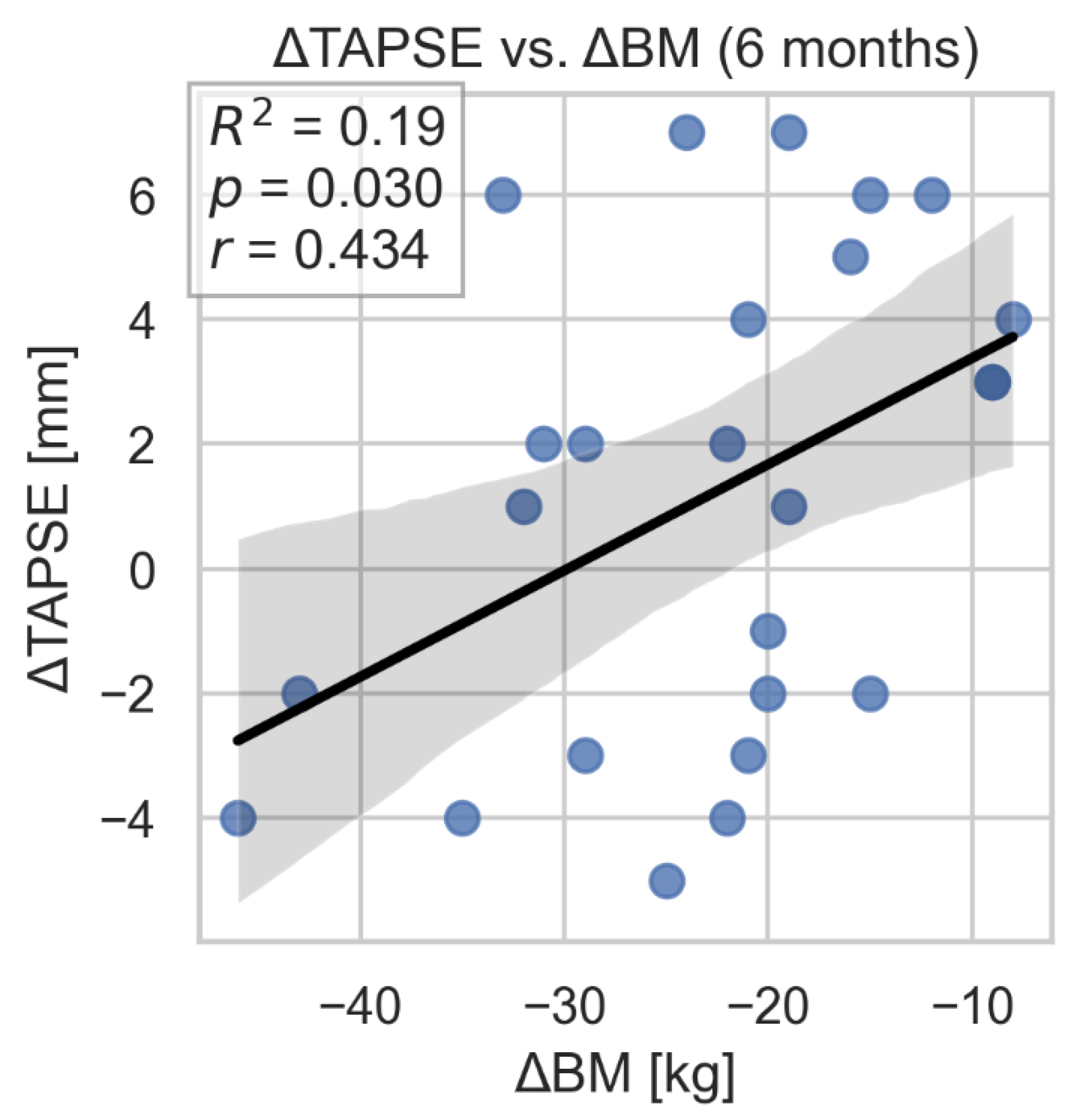

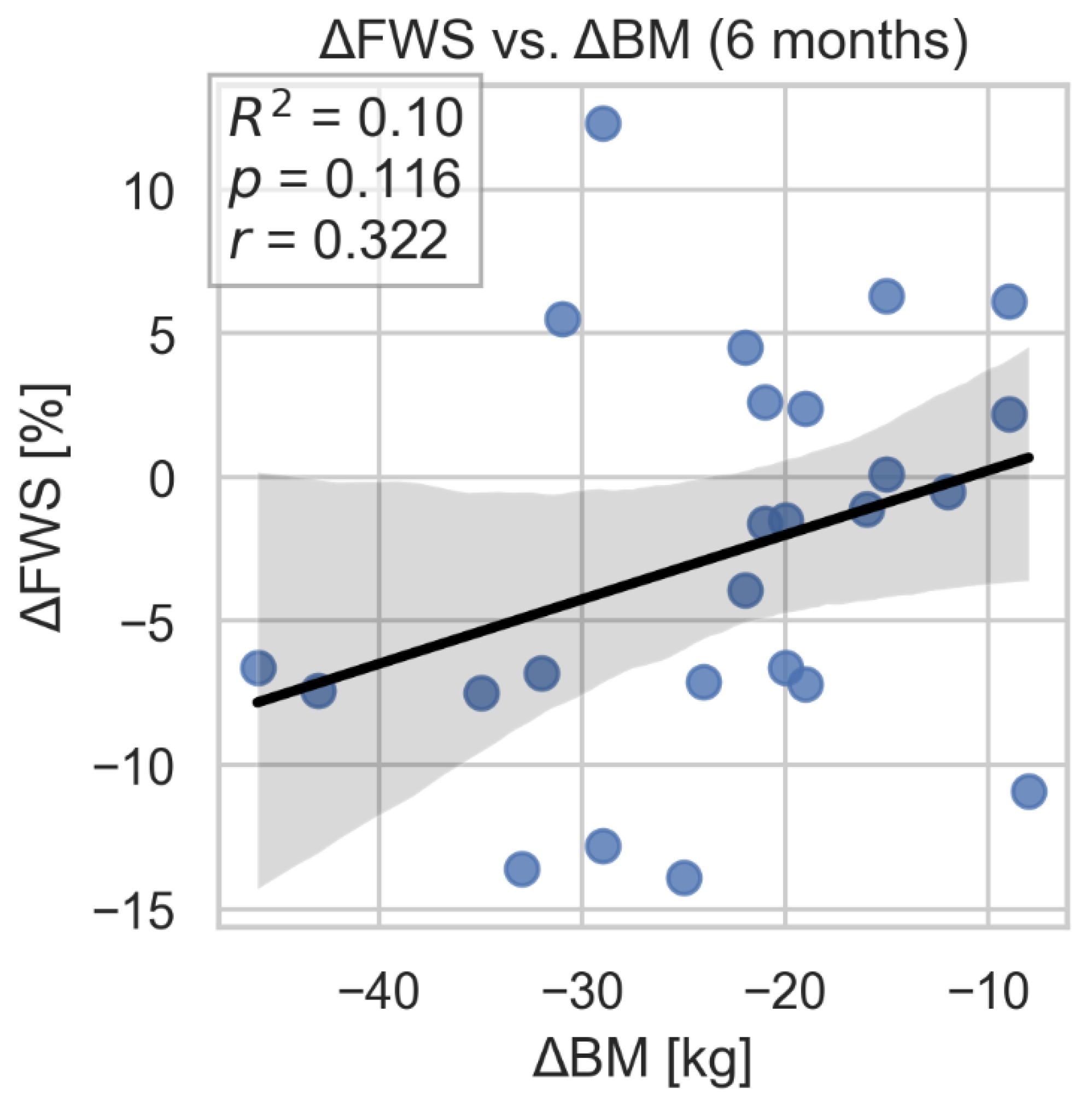

The study showed a correlation between improvement in GSRV and TAPSE parameters and weight loss. However, we did not find evidence of a similar, statistically significant association between improvement in FWS and change in body weight. (

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

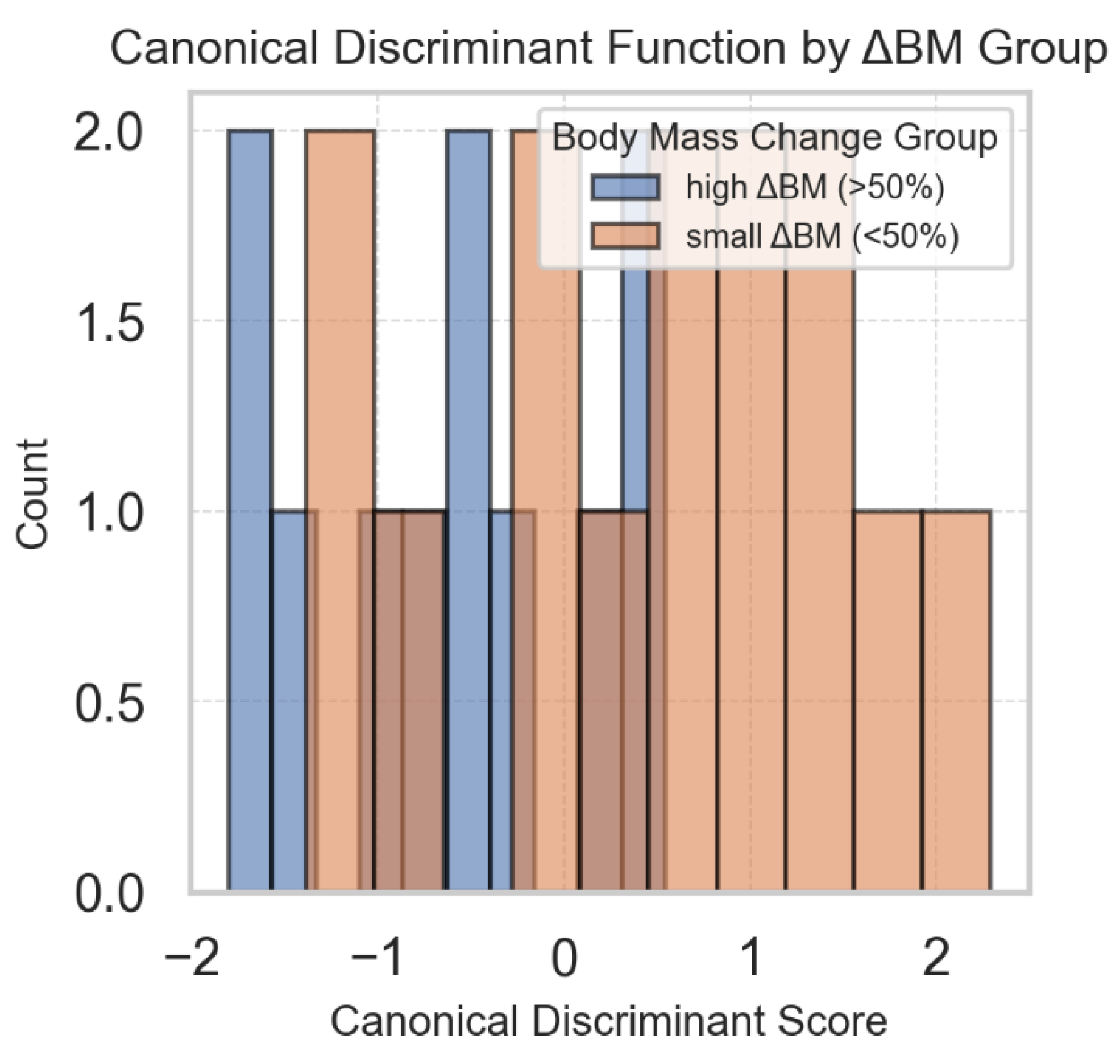

On top of individual regression models for each of the aforementioned parameters (GSRV, FWS and TAPSE), a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to test whether the combined change in these parameters was associated with weight loss. The overall MANOVA was statistically significant (Wilks’ λ = 0.673, p = 0.037), indicating that change in body weight was related to the multivariate profile of these right ventricular parameters. In the follow-up canonical discriminant analysis, ΔGSRV (−0.285) had the largest standardized weight in separating groups of low vs. high body mass change, followed by ΔTAPSE (−0.166) and ΔFWS (0.101) (

Figure 12).

4. Discussion

Obesity, especially severe obesity, can cause changes in cardiac hemodynamics, cardiac morphology and atrial and ventricular function that may predispose to heart failure (HF). Pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for the development of HF in patients with obesity include hemodynamic changes, neurohormonal activation, the influence of adipose tissue on the endocrine and paracrine systems, and lipotoxicity [

8]. Excessive adipose accumulation is associated with increased total and central blood volume and increased cardiac output. Higher cardiac output leads to left ventricular dilatation and subsequent hypertrophy secondary to increased wall stress [

9]. The above hemodynamic changes mainly affect the diastolic function of the left ventricle, while studies examining LV systolic function in obese individuals have shown mixed results. Most studies have demonstrated normal or above-normal left ventricular ejection fraction in obese people. Moreover, most reports have not shown a significant difference in left ventricular systolic function between obese and normal weight individuals. It is believed that the presence of severe LV systolic dysfunction in obese patients is associated with co-morbidities - most often coronary artery disease [

10]. Additionally LVEF may not be an optimal marker for the evaluation of cardiac dysfunction in the obese population. In the present study, LVEF was normal at baseline and unchanged at follow-up. However, the current study confirmed a reduction in LV end-diastolic volume after bariatric surgery, correlating with body weight loss. The results of the current analysis also showed that despite normal LVEF, abnormal GLS parameters were observed in the study population. According to previous reports, tissue Doppler imaging studies in obese individuals have demonstrated evidence of subclinical left ventricular dysfunction, even with normal left ventricular ejection phase indices. Compared with ejection fraction, myocardial mechanical index global longitudinal strain can detect subclinical reduced left ventricular systolic function earlier and reflect myocardial systolic function abnormalities more sensitively. LV longitudinal strain mostly represents the function of subendocardial longitudinal fibers, which could be more sensitive to change of wall stress according to obesity status. Therefore, GLS is likely a better parameter for assessing the left ventricle in obese patients, as it allows for early detection of left ventricular systolic-diastolic dysfunction [

3,

11,

12,

13,

14]. It is also very important that the current study demonstrated a significant improvement in LV GLS in patients shortly after bariatric surgery. These findings are consistent with few previous reports in the literature. Shin et al. demonstrated that approximately 15 months after bariatric surgery, there is a reduction in LV mass and improvement in longitudinal strain, with unchanged LVEF [

3]. Another study assessing myocardial mechanics in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery also confirmed a significant improvement in GLS over a 23-month follow-up period with unchanged LVEF parameters [

15]. Subsequent studies have shown improvement in GLS as early as 1 and 6 months after bariatric surgery - these results are consistent with those shown in the present analysis [

16,

17].

Obesity is considered an independent factor in the development of left ventricular diastolic failure [

10,

18]. Most studies demonstrating impaired LV diastolic function in obesity have reported a high prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), with progressive impairment of LV diastolic function with increasing LV mass (LVM) (presumably due to muscle, fibrosis and intra-myocardial fat) [

19,

20,

21]. In the present study, the average cardiac muscle thickness was 11.2 mm, and the average cardiac muscle mass was 205 g/m2. After bariatric surgery, a significant reduction in LV mass was observed, but no correlation was found between LV mass reduction and body weight loss. Several studies have assessed the association between the degree of obesity and left ventricular mass measurements and the reduction in LV mass after weight loss [

22,

23,

24]. These studies also demonstrated the coexistence of obesity with left ventricular hypertrophy and a reduction in left ventricular mass after weight loss, with no correlation between LV mass and BMI.

Previous reports have shown improvement in left ventricular diastolic function shortly after bariatric surgery [

25,

26,

27,

28]. In the current study, no significant changes after bariatric surgery were found in typical echocardiographic parameters used to assess left ventricular filling, however, a significant improvement in left atrial strain was demonstrated. According to previous reports, obese patients had a significant reduction in LAS parameters compared with non-obese controls. Obese patients without known cardiovascular disease have significantly decreased LA function in all three LA functional components compared to non-obese controls. There was no difference in the prevalence of diastolic dysfunction evaluated using current guidelines, suggesting that left atrial dysfunction assessed by LAS allows for earlier detection of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction [

29]. According to another study, obesity is associated with a functional LA phenotype by reduced conduit and reservoir function, with an increase in booster function, which may be compensatory [

30]. In the current study, a reduction in all LAS parameters was demonstrated, while during the 6-month follow-up period, significant improvement was observed only in reservoir and conduit function. These changes correlated with weight loss. Similar results was presented by Strzelczyk et al. [

31]. The 12-month follow-up after bariatric surgery showed a significant increase in LA-r and LA-cd with a decrease in LA-ct. According to the authors, the decrease in LASct is associated with improved early left ventricular filling during diastole, which may lead to a relative decrease in the contribution of atrial contraction.

The current study demonstrated significant improvement in right ventricular function after bariatric surgery. According to previous reports, subclinical right ventricular dysfunction is often found in patients with obesity. Right ventricular dilation caused by volume overload may increase myocardial oxygen consumption and ventricular wall stress [

32]. In studies assessing the right ventricle before and after bariatric surgery, significant improvements in RV function were observed, demonstrated by various parameters [

33,

34]. The current study demonstrated significant improvements in GSRV and FWS parameters. To date, there are few studies assessing right ventricular strain in obese patients. Yuksel et al. showed in a short-term study that weight reduction in obese patients improved diastolic parameters and strain of both the left and right ventricles [

35]. In turn, the meta-analysis by Esparham et al. [

6] showed an improvement in most left ventricular parameters, while the right ventricular structure changed to a lesser extent. Sorimachi et al [

4] highlighted long-term benefits, including LV mass reduction, decreased epicardial adipose tissue thickness, and improvement in left and right ventricular strain, even though LA volume and preload pressures in the LA increased over time Additionally, regarding right ventricular function and pulmonary circulation pressure, Büber et al [

36] demonstrated that as early as 6 months after bariatric surgery, pulmonary artery stiffness decreased and TAPSE improved, indicating better RV function [

8]. In our study, the combined analysis of right ventricular strain and TAPSE proved important. We found that improvement in these parameters correlated best with weight loss after bariatric surgery.

In summary, in the present study, significant changes in left and right ventricular function were demonstrated shortly after bariatric surgery.

5. Conclusions

In the short term, bariatric surgery leads to significant improvement in global longitudinal strain of the left and right ventricles in obese patients, with relative stability of LVEF and diastolic parameters. These results suggest early improvement in subclinical systolic function parameters following weight reduction in obese patients. The best echocardiographic parameters for monitoring hemodynamic changes in this group of patients are GLS, RVFWS, and TRV.

Further studies with longer follow-up are needed to assess the durability of these changes and their prognostic significance.

Author Contributions

PC- writing, original draft preparation; AP- methodology, results interpretation; validation MM- statistical study; PB – investigation, data curation; ŁN- investigation, data curation; ASG- investigation,; BG- investigation, ZS – supervision, writing-review and editing.

Data Availability Statement

All data were included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grapsa J, Tan TC, Paschou SA, Kalogeropoulos AS, Shimony A, Kaier T, Demir OM, Mikhail S, Hakky S, Purkayastha S, Ahmed AR, Cousins J, Nihoyannopoulos P. The effect of bariatric surgery on echocardiographic indices: a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Invest 2013;43(11):1224–1230. [CrossRef]

- Alpert MA, Omran J, Bostick BP. Effects of Obesity on Cardiovascular Hemodynamics, Cardiac Morphology, and Ventricular Function. Curr Obes Rep 2016;5:424–434. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Heo, Y.S.; Park, S.D.; Kwon, S.W.; Woo, S.I.; Kim, D.H.; Park, K.S.; Kwan, J. Beneficial Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Cardiac Structure and Function in Obesity. Obes. Surg. 2017; 27: 620–625. [CrossRef]

- Sorimachi H, Obokata M, Omote K, Reddy YNV, Takahashi N, Koepp KE, Ng ACT, Rider OJ, Borlaug BA. Long-Term Changes in Cardiac Structure and Function Following Bariatric Surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80(16):1501–1512. [CrossRef]

- Mostfa, S.A. Impact of obesity and surgical weight reduction on cardiac remodeling. Indian Heart J 2018;70:S224–S228. [CrossRef]

- Esparham A, Shoar S, Kheradmand HR, Ahmadyar S, Dalili A, Rezapanah A, Zandbaf T, Khorgami Z. The Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Cardiac Structure and Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2023;33:345–361.

- Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt JU. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015; 28:1-39.e14. [CrossRef]

- Aryee EK, Ozkan B, Ndumele CE. Heart Failure and Obesity: The Latest Pandemic. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;78:43. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues MM, Falcão LM. Pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in overweight and obesity - clinical and treatment implications. Int J Cardiol. 2025;1;430:133182. [CrossRef]

- Alpert MA, Karthikeyan K, Abdullah O, Ghadban R. Obesity and Cardiac Remodeling in Adults: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018; 61:114-123. [CrossRef]

- Wong CY, O’Moore-Sullivan T, Leano R, Byrne N, Beller E, Marwick TH. Alterations of left ventricular myocardial characteristics associated with obesity. Circulation. 2004 ;110:3081-3087. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa MM, Beleigoli AM, de Fatima Diniz M, Freire CV, Ribeiro AL, Nunes MC. Strain imaging in morbid obesity: insights into subclinical ventricular dysfunction. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:288-293.

- Orhan AL, Uslu N, Dayi SU, Nurkalem Z, Uzun F, Erer HB, Hasdemir H, Emre A, Karakus G, Soran O, Gorcsan J 3rd, Eren M. Effects of isolated obesity on left and right ventricular function: a tissue Doppler and strain rate imaging study. Echocardiography. 2010;27:236–243.

- Kang X, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Kang C, Xue J. Myocardial mechanical changes before and after bariatric surgery in individuals with obesity and diabetes: a 1-year follow-up study. Sci Rep. 2025; 2;15:580. [CrossRef]

- Koshino, Y.; Villarraga, H.R.; Somers, V.K.; Miranda, W.R.; Garza, C.A.; Hsiao, J.F.; Yu, Y.; Saleh, H.K.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Changes in myocardial mechanics in patients with obesity following major weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obesity 2013, 21, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuluce K, Kara C, Tuluce SY, Cetin N, Topaloglu C, Bozkaya YT, Saklamaz A, Cinar CS, Ergene O. Early Reverse Cardiac Remodeling Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2017;27:364-375. [CrossRef]

- Kemaloğlu Öz T, Ünal Dayı Ş, Seyit H, Öz A, Ösken A, Atasoy I, Yıldız U, Özpamuk Karadeniz F, İpek G, Köneş O, Alış H. The effects of weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy on left ventricular systolic function in men versus women. J Clin Ultrasound. 2016;44:492-499.

- Kossaify A, Nicolas N. Impact of overweight and obesity on left ventricular diastolic function and value of tissue Doppler echocardiography. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2013;7:43-50. [CrossRef]

- Lavie CJ, Alpert MA, Arena R, Mehra MR, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Impact of obesity and the obesity paradox on prevalence and prognosis in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol HF 2013;1:93-102. [CrossRef]

- Alpert MA, Omran J, Mehra A, Ardhanari S. Impact of obesity and weight loss on cardiac performance and morphology in adults. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2014;56:391-400. [CrossRef]

- Alpert MA, Lavie CJ, Agrawal H, Kumar A, Kumar SA. Cardiac effects of obesity: pathophysiologic, clinical and prognostic consequences. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2016; 36:1-11.

- Alpert MA, Terry BE, Kelly DL. Effect of weight loss on cardiac chamber size, wall thickness and left ventricular function in morbid obesity. Am J Cardiol. 1985 1;55:783-786. [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis G, Ribaudo MC, Leto G, Zappaterreno A, Vecci E, Di Mario U, Leonetti F. Influence of excess fat on cardiac morphology and function: study in uncomplicated obesity. Obes Res. 2002;10:767-773. [CrossRef]

- Hsuan CF, Huang CK, Lin JW, Lin LC, Lee TL, Tai CM, Yin WH, Tseng WK, Hsu KL, Wu CC. The effect of surgical weight reduction on left ventricular structure and function in severe obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18:1188-1193. [CrossRef]

- Willens HJ, Byers P, Chirinos JA, Labrador E, Hare JM, de Marchena E. Effects of weight loss after bariatric surgery on epicardial fat measured using echocardiography. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1242–1245. [CrossRef]

- Valezi AC, Machado VH. Morphofunctional evaluation of the heart of obese patients before and after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2011;21:1693–1697. [CrossRef]

- Kardassis D, Bech-Hanssen O, Sch€onander M, Sj€ostr€om L, Karason K. The influence of body composition, fat distribution, and sustained weight loss on left ventricular mass and geometry in obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:605–611. [CrossRef]

- Leichman JG, Wilson EB, Scarborough T, Aguilar D, Miller CC 3rd, Yu S et al. Dramatic reversal of derangements in muscle metabolism and left ventricular function after bariatric surgery. Am J Med 2008;121:966–973.

- Aga, Y.S.; Kroon, D.; Snelder, S.M.; Biter, L.U.; de Groot-de Laat, L.E.; Zijlstra, F.; Brugts, J.J.; van Dalen, B.M. Decreased Left Atrial Function in Obesity Patients without Known Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 39, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirinos JA, Sardana M, Satija V, Gillebert TC, De Buyzere ML, Chahwala J, De Bacquer D, Segers P, Rietzschel ER; Asklepios investigators. Effect of Obesity on Left Atrial Strain in Persons Aged 35-55 Years (The Asklepios Study). Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:854-861. [CrossRef]

- Strzelczyk J, Kalinowski P, Zieniewicz K, Szmigielski C, Byra M, Styczyński G. The Influence of Surgical Weight Reduction on Left Atrial Strain. Obes Surg. 2021;31:5243-5250. [CrossRef]

- Wong CY, O’Moore-Sullivan T, Leano R, Hukins C, Jenkins C, Marwick TH. Association of subclinical right ventricular dysfunction with obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 7;47:611-616. [CrossRef]

- Garza CA, Pellikka PA, Somers VK, Sarr MG, Collazo-Clavell ML, Korenfeld Y, Lopez-Jimenez F. Garza CA, Pellikka PA, Somers VK, Sarr MG, Collazo-Clavell ML, Korenfeld Y, Lopez-Jimenez F. Am J Cardiol. 2010; 15;105:550-556.

- Liu J, Li J, Yu J, Xia C, Pu H, He W, Li X, Zhou X, Tong N, Peng L. Regional Fat Distributions Are Associated With Subclinical Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Adults With Uncomplicated Obesity. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022; 25:9:814505.

- Yuksel IO, Akar Bayram N, Koklu E, Ureyen CM, Kucukseymen S, Arslan S, Bozkurt E Assessment of Impact of Weight Loss on Left and Right Ventricular Functions. Echocardiography 2016; 33:854–861.

- Büber I, Aykota MR, Sevgican Cİ, Kaya D, Akarsu H, Tekin I, Kılıc ID. Impact of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy on Pulmonary Arterial Stiffness and Right Ventricular Function. Obes Surg 2025;35:87–92. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Changes in left ventricular thickness and mass over time.

Figure 1.

Changes in left ventricular thickness and mass over time.

Figure 2.

Linear regression models assessing the relationships between LV wall thickness, LV mass, and change in body weight. LVWT- left ventricular wall thickness; LVM- left ventricular mass.

Figure 2.

Linear regression models assessing the relationships between LV wall thickness, LV mass, and change in body weight. LVWT- left ventricular wall thickness; LVM- left ventricular mass.

Figure 3.

Changes in volumetric parameters of the left ventricle 3 and 6 months after bariatric surgery. LVEDV- left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV- left ventricular end-systolic volume; SV- stroke volume.

Figure 3.

Changes in volumetric parameters of the left ventricle 3 and 6 months after bariatric surgery. LVEDV- left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV- left ventricular end-systolic volume; SV- stroke volume.

Figure 4.

Changes in LVEDV in the early and late period compared to similar changes in BM. LVEDV- left ventricular end-diastolic volume; BM- body mass.

Figure 4.

Changes in LVEDV in the early and late period compared to similar changes in BM. LVEDV- left ventricular end-diastolic volume; BM- body mass.

Figure 5.

Correlation between changes in LAS-r and loss of weight after bariatric surgery. LAS-r- left atrial strain- reservoir; BM- body mass.

Figure 5.

Correlation between changes in LAS-r and loss of weight after bariatric surgery. LAS-r- left atrial strain- reservoir; BM- body mass.

Figure 6.

Correlation between changes in LAS-cd and loss of weight after bariatric surgery. LAS-cd- left atrial strain- conduit; BM- body mass.

Figure 6.

Correlation between changes in LAS-cd and loss of weight after bariatric surgery. LAS-cd- left atrial strain- conduit; BM- body mass.

Figure 7.

Changes in parameters of the right ventricle 3 and 6 months after bariatric surgery. GSRV- global longitudinal strain of the right ventricle; FWSRV- free wall strain of the right ventricle; TAPSE- tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Figure 7.

Changes in parameters of the right ventricle 3 and 6 months after bariatric surgery. GSRV- global longitudinal strain of the right ventricle; FWSRV- free wall strain of the right ventricle; TAPSE- tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Figure 8.

Change in global strain of the right ventricle and correlation with body mass in two time intervals. GSRV-global longitudinal strain of the right ventricle; BM- body mass.

Figure 8.

Change in global strain of the right ventricle and correlation with body mass in two time intervals. GSRV-global longitudinal strain of the right ventricle; BM- body mass.

Figure 9.

Correlation between GS RV change and weight loss. GSRV-global longitudinal strain of the right ventricle; BM- body mass.

Figure 9.

Correlation between GS RV change and weight loss. GSRV-global longitudinal strain of the right ventricle; BM- body mass.

Figure 10.

Correlation between TAPSE change and weight loss. TAPSE- tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; BM- body mass.

Figure 10.

Correlation between TAPSE change and weight loss. TAPSE- tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; BM- body mass.

Figure 11.

Correlation between FWSRV change and weight loss. FWS- free wall strain of the right ventricle; BM- body mass.

Figure 11.

Correlation between FWSRV change and weight loss. FWS- free wall strain of the right ventricle; BM- body mass.

Figure 12.

Canonical discriminant analysis (CDA) plot showing separation between participants with low and high change in body weight based on the combined change in GSRV, FWS and TAPSE.

Figure 12.

Canonical discriminant analysis (CDA) plot showing separation between participants with low and high change in body weight based on the combined change in GSRV, FWS and TAPSE.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of the study group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of the study group.

| Category |

Count (%) |

| Gender |

| Women |

32 (82.05%) |

| Men |

7 (17.95%) |

| Comorbidities |

| Hypertension (HTN) |

17 (43.59%) |

| Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD) |

3 (7.69%) |

| Diabetes |

9 (23.08%) |

| Hypothyroidism |

11 (28.21%) |

| Type of procedure |

| Sleeve Gastrectomy |

34 (87.18%) |

| Balloon |

3 (7.69%) |

| Mini-Gastric Bypass |

1 (2.56%) |

| Single Anastomosis Sleeve Ileal Bypass |

1 (2.56%) |

Table 2.

Changes in left ventricular parameters after bariatric surgery.

Table 2.

Changes in left ventricular parameters after bariatric surgery.

Left ventricle

Parameters |

Before surgery |

3 months after surgery |

6 months after surgery |

P value |

| LV wall thickness |

11.1 +/- 1.2 |

11.1 +/- 1.2 |

10.9 +/- 1.2 |

0.14 |

| LV mass index (g/m2) |

109.7 +/- 20.3 |

99.1 +/-19.4 |

87.4 +/- 16.2 |

<0.001 |

| LVEDV |

47.1 +/- 13.2 |

30.0 +/- 15.0 |

43.7 +/- 11.0 |

<0.001 |

| LVESV |

18.7 +/- 5.4 |

16.1 +/- 5.3 |

16.9 +/- 3.8 |

0.18 |

| SV |

29.7 +/- 7.8 |

24.3 +/- 7.6 |

26.3 +/- 3.7 |

0.05 |

| LVEF (%) |

59±4.8 |

61±4.8 |

61.3±4,8 |

0.167 |

| GLS (%) |

-14.38±2.47 |

-16.79±2.21 |

-18.01±2.32 |

0.001 |

| E/A |

1.1 +/- 0.3 |

1.1 +/- 0.4 |

1.2 +/- 0.3 |

0.38 |

| T dec |

194.8 +/- 33.4 |

214.8 +/- 45.2 |

197.1 +/- 33.9 |

0.06 |

| e’ sept (cm/s) |

9.88±2.54 |

10.04±2.31 |

11.00±2.65 |

0.15 |

| E/e’ sept |

8.17±1.69 |

7.58±2.36 |

7.46±1.69 |

0.39 |

| e’ lat (cm/s) |

13.5±2.70 |

13.46±3.51 |

15.21±4.42 |

0.13 |

| E/e’ lat |

6.71±1.52 |

6.58±1.61 |

6.04±1.27 |

0.14 |

| LAVI (ml/m2) |

24.3±9.17 |

23.9±8.77 |

22.8±7.19 |

0.32 |

| LAS-r |

22.5 +/- 7.5 |

28.0 +/- 6.1 |

31.1 +/- 8.6 |

<0.001 |

| LAS-cd |

-12.8 +/- 6.3 |

-16.5 +/- 5.3 |

-19.6 +/- 7.0 |

<0.001 |

| LAS-ct |

-8.3 +/- 7.0 |

-11.5 +/- 3.8 |

-10.8 +/- 5.8 |

0.18 |

Table 3.

Changes in right ventricular parameters after bariatric surgery.

Table 3.

Changes in right ventricular parameters after bariatric surgery.

Right ventricle

Parameters |

Before surgery |

3 months after surgery |

6 months after surgery |

P-value |

| GSRV [%] |

-15.9+/-5.29 |

-18.8+/-4.03 |

-18.38+/-3.25 |

0.005 |

| FWSRV [%] |

-18.38+/-6.17 |

-19.7+/-5.00 |

-19.5+/-5.182 |

0.042 |

| TAPSE [mm] |

25.4+/-3.3 |

25.8+.-4.0 |

26.5+/-3.3 |

0.36 |

| TRV max (m/s) |

1.84±0.62 |

1.67±0.59 |

1.46±0.52 |

0.01 |

| s’ [cm/s] |

14.7+/-3.52 |

14.2+/-2.9 |

14.9+/-2.32 |

0.55 |

| AcT [ms] |

108.4+/-13.5 |

110.3+/-12.3 |

109.9+/-12.3 |

0.43 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).