1. Introduction

Matter, energy and information are the three basic elements of nature.[

1] In the current era of rapid development of information technology and artificial intelligence, information, as a bridge connecting the material world and the cognitive world, is becoming more and more important than ever. However, although people are talking about the “information revolution” with great interest and a large number of scholars are constantly devoting themselves to the research of informatics, the progress of information theory is not optimistic. The question of the nature of information has always troubled us[

2,

3,

4].The concept of informatics, which takes information as its object, was proposed as early as the early 1990s, but has made little progress in the past 30 years and has failed to have a significant impact on the development of information technology and systems[

5].The reasons for this are: first, there is a lack of a rigorous, universal definition of information; second, the phenomena encompassed by “information” are incredibly diverse, making it difficult to arrive at a comprehensive definition and establish a unified information theory; third, using only information quantity and information entropy as information metrics is too simplistic and ill-suited to the rich functionality of existing information systems; and fourth, current “information theory” is essentially still “communication coding theory.” While it covers several important aspects of information encoding, transmission, and storage, it largely ignores aspects of information understanding and processing. Therefore, the development of a comprehensive theoretical framework for informatics is imperative.

Starting from Wiener’s famous statement that “information is information, not matter, not energy”, Chinese scholar Xu Jianfeng regards information as the third basic category in the objective world, alongside matter and energy. He established a set of basic information postulates, mathematical definitions, a six-tuple model, five properties and 11 types of measurement systems based on the “reflective information view”, forming the theoretical system of Objective Information Theory (OIT). He proved that several previously unrelated classical information principles and formulas can be uniformly expressed through OIT[

6,

7,

8].On this basis, the dynamic configuration and metric efficiency distribution of information systems were established, forming a theoretical framework for information system dynamics. In short, objective information theory, based on people’s common understanding of information, defines the information ontology set

o, the ontology occurrence time set

, the ontology state set

, the objective carrier set

c, the carrier reflection time set

, and the carrier reflection set

. Information

I is the enabling mapping from the ontology state set

to the carrier reflection set

.

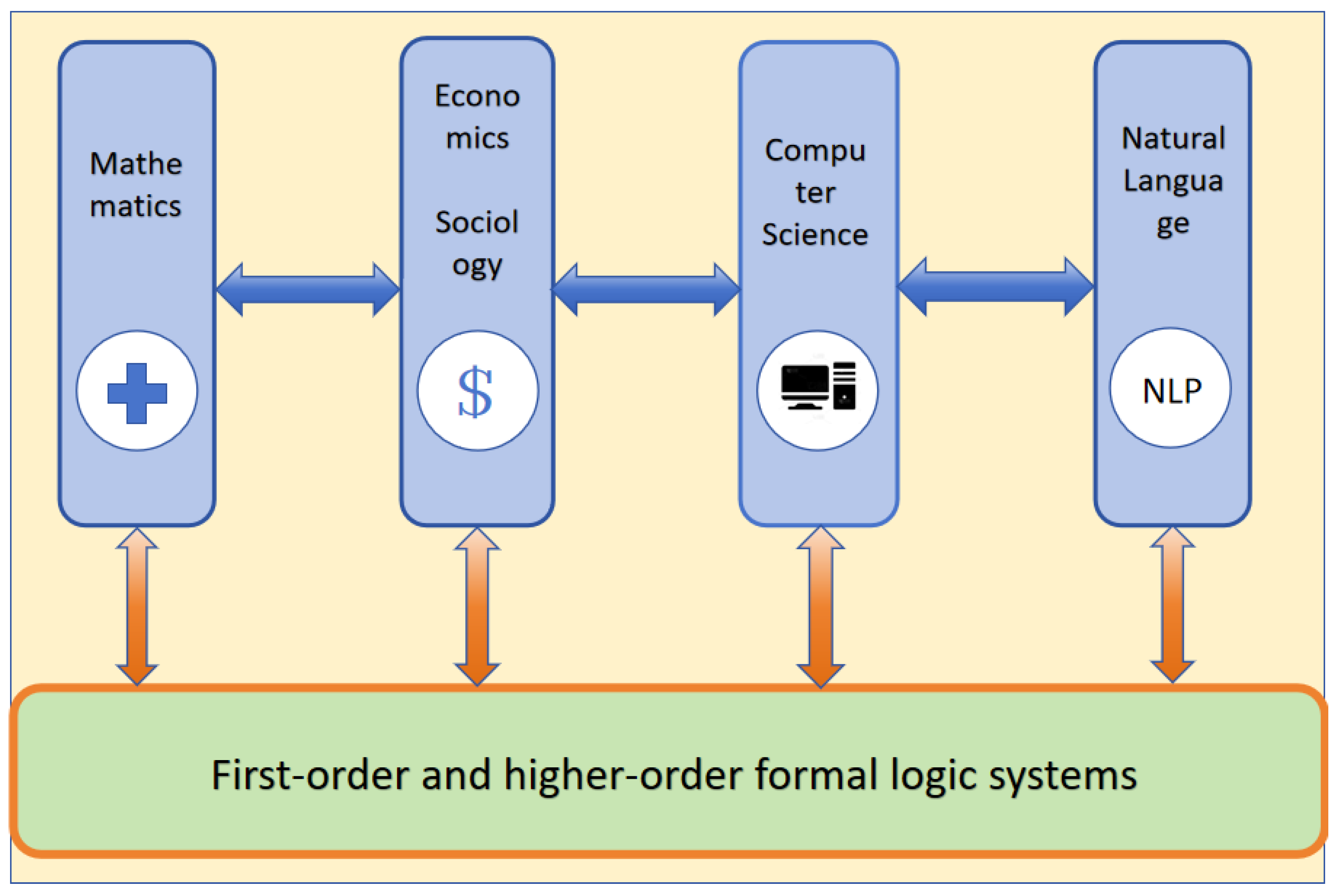

However, objective information theory lacks a rigorous mathematical definition of state, and its theoretical foundation remains incomplete. To address this issue, this paper aims to integrate the research findings of classical information theory, supplement the definition and model of information, and construct a formal representation of the object state, further clarifying its composition. Starting from the perspective of mathematical logic, this paper rigorously defines first-order and higher-order predicate logic systems, connects state with the interpretation of sets of well-formed formulas, and develops a comprehensive formal representation of state. This approach fills the existing theoretical gaps in OIT theory and further enhances research on the nature of information. Furthermore, from the perspectives of mathematics, economics, sociology, computer science, and natural linguistics, this paper abstracts typical phenomena from various disciplines, providing a universal symbolic and formal representation of the state within them.

Leveraging this universal formalization, first-order and higher-order logic become a bridge connecting the various fields. This reveals a profound unity in the development of modern science and technology: while different disciplines superficially deal with vastly different objects and phenomena, at a deeper level, they can all be uniformly expressed and mutually transformed through the language of logic.

Figure 1.

The logical system has become a bridge for communication between various fields and is the most universal language.

Figure 1.

The logical system has become a bridge for communication between various fields and is the most universal language.

2. Formal Expression of State

The information postulate emphasizes that the state of the ontology can be mapped to the state of the carrier. Therefore, establishing a formal representation of the ontology and carrier states is particularly important. Mathematical logic, based on axiomatic systems and symbolic language, enables rigorous and unambiguous characterization of concepts, propositions, and their reasoning. It avoids the ambiguity and uncertainty of natural language expressions and provides a precise descriptive tool for scientific research. Professor Xu Jianfeng of Shanghai Jiao Tong University provided me with a reference for this approach, and based on his work, I conducted further research and expansion. Let’s first limit the object language to first-order languages.

2.1. First-Order Formal System Definition

First-order predicate logic language has become a core tool for formal modeling and automatic reasoning in fields such as mathematics, information science, and artificial intelligence due to its strong expressiveness, clear structure, rigorous reasoning, good computability, and strong versatility[

9].First, we define the most basic symbols in the first-order formal system:

Definition 1 (Symbols in ). contains the following symbols:

First-order variables:

First-order constants:

First-order function symbols:

brackets:(, )

First-order predicate symbols:

Logical connectives:∼ (Negation),→ (Implication)

Quantifiers:∀ (Universal quantifier)

Based on logical theory, symbols such as conjunction ∧, disjunction ∨, if and only if ↔, and existence ∃ can be naturally introduced. In particular, some common mathematical symbols, such as , are also considered universal predicate symbols and will not be discussed further.

Terms in a language are similar to nouns or noun phrases in a natural language, but terms and nouns (phrases) are not exactly the same. The main difference is that terms contain variables and are “compound” items constructed using variables.

Definition 2 (Terms in ). The terms in are generated as follows:

-

(1)

Variables and constants are terms:

-

(2)

If () is a function symbol in and is a term in , then is also a term in .

Next, we define atomic formulas. Atomic formulas are the most basic formulas in the language.

Definition 3 (Atomic formulas in ). If () is a predicate symbol in and is a term in , then is an atomic formula in .

Definition 4 (Well-formed formulas in ). The well-formed formula in is defined as follows:

-

(1)

Each atomic formula is a well-formed formula in ;

-

(2)

If and are well-formed formulas in , then and are both well-formed formulas in ;

-

(3)

If is a well-formed formula in and u is a variable or function symbol in , then is a well-formed formula in .

2.2. Recursive Definition of Higher-Order Formal Systems

Considering that first-order logic still has many shortcomings in terms of quantified objects, recursive induction, and other issues, such as its inability to fully express the concept of a set and its lack of direct characterization of higher-order properties, we need to expand the characterization capabilities of logical systems.Higher-order predicate logic (HOL) is an extension of first-order predicate logic. It allows quantification over predicates, functions, and even predicates about predicates. It offers greater expressive power, can formalize complex semantics in natural language and mathematics, and supports a richer set of logical tools and theoretical frameworks. Next, we will define higher-order formal systems.

Assume that for

, the corresponding formal systems

have been defined. Then the symbols in the

k-order formal system

can be recursively defined[

10].

Definition 5 (Symbols in ). The symbols in include:

All symbols of ;

k-order variables:

k-order constants:

k-order predicate variables:

k order function symbols:

k-order predicate symbols:

Similarly, we can recursively define the terms in , atomic formulas and well-formed formulas.

Definition 6 (Terms in ). The terms in are defined as follows:

-

(1)

All terms of ;

-

(2)

If () is a k-order function symbol in and are variables, constants, or functions in , then is a k-order term in .

Definition 7 (Atomic formulas in ). The atomic formula in is defined as follows:

-

(1)

All atomic formulas of ;

-

(2)

If () is a predicate symbol of order k in and are terms in , then is an atomic formula of order k in .

Definition 8 (Well-formed formula in ). The well-formed formula in is defined as follows:

-

(1)

All well-formed formulas for ;

-

(2)

If and are well-formed formulas in , then and are both well-formed formulas in ;

-

(3)

If is a well-formed formula in and u is an argument or function symbol in , then is a well-formed formula in .

2.3. Interpretation of Formal Systems

Next, we can define the interpretation of the formal system.

Definition 9 (Interpretation of formal systems). An interpretation E of the formal system is a two-tuple . Where:

The domain is a non-empty set that contains the value range of all elements in , including individuals, properties, relations, and functions.

-

The interpretation function J is a mapping that maps symbols in to concrete semantics in the domain and is defined as follows:

- –

Interpretation of constants and variables: Each constant is interpreted as an element in , i.e., ; each variable is interpreted as an element in , i.e., .

- –

Interpretation of function symbols: Each function symbol is interpreted as a mapping from to , that is, .

- –

Interpretation of predicate symbols: Each predicate symbol is interpreted as a mapping from to , i.e., .

- –

Interpretation of the terms:

- –

Interpretation of atomic formula:

- –

Interpretation of logical connectives:

- –

Interpretation of quantifiers: If , where u is a variable or function symbol, then

The interpretation of formal systems transforms the abstract syntax of formal logic into concrete semantics, serving as a crucial link between the “symbolic world” and the “real world.” It not only renders logical language meaningful but also provides a theoretical foundation for correct reasoning, modeling, verification, and automated applications. It is an essential concept in mathematical logic and information science.

2.4. Axiom System for Logical Expression of Ontology Components Under State Decomposition

Let

X denote a set of objects,

T denote a set of time points or intervals, and

L denote a higher-order formal system. We propose the following four axioms[

11].

Parameter Reference Axiom : Every object , every moment or period , and every function is represented by a unique constant or term in L.

Property Expressibility Axiom : The properties, form, value, relationship and other attributes of a set of objects in the entire domain can be expressed through functions and predicates in the formal system.

-

Logical Combination and the Closure Axiom

The generation rules of the state space are limited to the following logical operations:

Implication:If ,then it implies that is also a state of ;

Negation:If , then ;

Quantification: For any state predicate , and also belong to .

In other words, is closed with respect to the above logical operations and only allows new states to be generated through a finite number of implications, negations, and quantifications.

Axiom of temporal causality:When any attribute, relationship, or state is established at a certain moment, its change or evolution at subsequent moments can be described by the formula in L.

Theorem 1. If for any , there exists at least one attribute, relation, or property that can be expressed by L, and satisfies the axioms of parameter reference, attribute expressibility, logical combination closure, and temporal causality, then all states of any object x at any time t can be uniquely characterized by a set of well-formed formulas in L.

Proof of Theorem1. According to the parameter reference axiom, the object x, time t, and the function f involved in the set can all be represented by unique terms in L.

Next, according to the property expressibility axiom, the various properties of the state set can be expressed using functions and predicates in the formal system.

By definition, all expressions in the above state sets are atomic formulas in L. By logical combination and the closure axiom, any complex ontological state G can be recursively constructed from the base state by applying a finite number of generation rules expressible in L. Each generation rule is uniquely described by a well-formed formula and inference rule in L. Therefore, for any object x and time t, all its ontological states can be uniquely mapped and characterized in L by the corresponding set of formulas , where is recursively generated from the atomic formulas using logical rules.

In terms of uniqueness, the construction of depends solely on x, t, and the set of ontological components. The representation of all predicates, functions, and parameters in L is uniquely determined by the axiomatic system. Therefore, uniquely corresponds to within L. If both characterize , then by the logical equivalence relation in L, , guaranteeing uniqueness.

Furthermore, the temporal causality axiom states that any time t can be expressed by a recursive or evolutionary formula in L. Specifically, for any , there exists a formula in L such that is uniquely determined by and related laws. Thus, any dynamic evolution of a system can be recursively expressed by a chain of well-formed formulas in L, and the history and future of its state can be reduced to the logical deduction of a set of formulas.

In summary, can always be rigorously characterized by a unique set of well-formulated formulas in L under interpretation, and this expression holds true for any dynamic evolution. The theorem is proved. □

2.5. The State of an Object at a Specific Time

Then, according to the theorem, we give the definition of state:

Definition 10 (state). The state of a set of objects x at a particular time set t is an interpretation of a set of well-formed formulas in the formal system on the universe . The specific properties of x and t, as well as the choice of formula set and the definition of the interpretation, are determined by the specific application scenario.

Theorem 1 and the definition of state demonstrate that state can be well described using first-order and higher-order logic. The formal representation of state is not only a technical tool but also a fundamental way for humans to understand and transform the world. It transforms intuitive concepts into precise mathematical objects, enabling rigorous reasoning and systematic analysis. As science and technology become increasingly complex, this formalization capability will continue to be a vital force driving the development of informatics and the progress of human civilization.

3. Mathematical Field State Expression

Mathematics, as a fundamental discipline, encompasses a wide range of branches and a vast system. Fundamental fields such as number theory focus on the properties of integers; algebra encompasses linear algebra (vector spaces and matrices), abstract algebra (groups, rings, and fields), and polynomial theory; and geometry includes Euclidean geometry and differential geometry (manifolds and curvature). Applied mathematics encompasses topology, probability theory and statistics (such as stochastic processes, Bayesian statistics, and the foundations of machine learning), and computational mathematics (numerical analysis, algorithm design, and scientific computing). Furthermore, new problems continue to emerge in discrete mathematics, mathematical physics, logic, and set theory.

From elementary arithmetic to cutting-edge research, mathematics demonstrates a progression in depth and abstraction, with numerous fields intersecting and integrating. Theorems, propositions, and formulas within each branch can be viewed as characterizing the “state” of certain mathematical objects. Broadly speaking, the state of mathematical objects is a core concept for understanding the dynamics, contextual dependence, and inherent connections of mathematical structures. Studying mathematical states not only helps focus on key properties and ignore minor details, but also helps grasp the essence of a problem, forming a crucial foundation for the development of mathematical theory.

3.1. Formalization of Finite Mathematical Structures

Finite structures are the foundation of discrete mathematics. Problems such as finite sets and their subsets, and the connectivity, coloring, and matching of graphs in finite graph theory are all inseparable from the study of finite structures. In addition, many “infinite” mathematical concepts originate from the generalization of finite structures[

12,

13,

14].

Finite mathematical structures are not only an essential component of mathematics but also fundamental tools for understanding the complex world, solving practical problems, and advancing science and technology. In a sense, finite structures are “real mathematics”—both theoretically elegant and practically useful. Here, we provide a rigorous proof that finite mathematical structures can be formalized in a first-order manner.

Definition 11 (Finite structure). Let be a finite structure, where: A is a finite set, , is an meta-relation, is a meta-function, and It’s constant.

Theorem 2 (First-order complete characterization of finite structures)

. If is a finite structure, then there exists a first-order language L and a set of L-sentences Γ such that for any L-structure :

Proof of Theorem2. The definition L includes:

Relation symbols: (with arity respectively)

Function symbols: (with arity respectively)

Constant symbols:

Individual constants: (corresponding to each element in A)

Let , construct the following statement:

() domain restriction statement:

() element-wise distinction statement:

() relation characterization statement:

For each relation symbol

and each tuple

:

() function characterization statement :

For each function symbol

and each tuple

:

Where

l satisfies

() Constant Characterization Statement:We define

. Next, we prove two lemmas.

Lemma 1. If , then .

Proof of Lemma1. By (), , so . By (), for all , so . Therefore, . □

Lemma 2. If , then the map defined as is a bijection.

Proof of Lemma2. This follows directly from Lemma 1 and (). □

Next we can prove the consequence of the Theorem2:

(⇒) If , then :

Let be an isomorphic mapping. Definition of :

By the definition of isomorphism, satisfies all statements in .

(⇐) If , then :

By Lemma 2, is defined as , which is a bijection.

Verify that h maintains the relationship:

For any

:

Verify that h holds:

For any , let

Verify that h remains constant:This is directly derived from ().

Thus, h is an isomorphism, .

We can then draw the following inferences

Corollary 1 (Uniqueness). The set of axioms Γ uniquely determines in the sense of logical equivalence.

Corollary 2 (Completeness). For any first-order property φ on , either or .

Proof of Corollary2. Let be any first-order sentence. Since is a sentence, either or must hold.

If , then by Theorem 1, any structure satisfying is isomorphic to , so . Therefore, .

If , then similarly, . □

Corollary 3 (Decidability). The set is decidable.

Proof of Corollary2. By Corollary 2, for any sentence , we can directly verify that on the finite structure . If true, then ; otherwise, . □

3.2. Previous Research on the Formalization of Infinite Structures

Naturally, we will wonder whether all infinite structures, except finite ones, can be completely characterized by a set of first-order logic formulas.

Generally speaking, the answer is no. In fact, according to the research results of Skolem et al., even countable structures cannot be guaranteed to be fully described by first-order logic[

15].

Theorem 3 (Skolem). The standard natural numbers are countable structures that cannot be characterized by first-order theoretical categories.

We will not give a detailed proof here. The main idea of the proof is to introduce infinite elements through extension theory. Then, we use the compactness theorem to derive a non-standard model and conclude.

Of course, if we expand the tools from first-order logic to higher-order logic, we can expand the characterization capabilities of the logical language[

16,

17]:

Theorem 4 (Peano). Under standard second-order semantics, the second-order Peano axioms categorically characterize the structure of natural numbers. That is, if quantification over set variables is allowed, then the sequence of natural numbers can be uniquely characterized by second-order logic.

This is truly a profound mathematical result, rigorously proven. It not only solves the problem of characterizing natural numbers but also reveals a fundamental property of the expressive power of logical systems—higher-order logic possesses greater expressiveness than first-order logic.

However, despite its greater expressiveness, higher-order logic still cannot represent all countable structures. The boundaries of the logical structures that higher-order logic can represent remain unresolved. This result reflects the fundamental tension between computability and logical expressiveness. Even the most powerful logical systems cannot fully “tame” the complexity of infinite structures. This perhaps reveals a certain irreducible complexity of mathematical reality.

At present, the problem of expressing mathematical structures still depends on the work done by Scott in 1965[

18].

Scott first introduced the concept of infinite logic:

Definition 12 (infinite logic). The language is defined by the following rules:

-

1.

Contains all atomic formulas of first-order logic

-

2.

If is a set of formulas and , then and are also formulas.

-

3.

If ϕ is a formula and x is a variable, then and are formulas.

-

4.

Every formula contains only a finite number of free variables.

Furthermore, he proposed the crucial isomorphism theorem in the article.

Theorem 5 (Scott’s isomorphism theorem, 1965). Let be a countable structure and be a countable language. Then there exists a statement (called a Scott statement of ) such that:

That is, completely characterizes the structure in an isomorphic sense.

Scott’s isomorphism theorem is more than just a technical result; it reveals that infinitely long formulas are a natural tool for dealing with infinite structures, and that abstract existence can be transformed into concrete constructions.

Scott’s isomorphism theorem not only solves a specific mathematical problem but, more importantly, opens up a whole new research paradigm, influencing multiple branches of mathematics and still guiding development in related fields today. This makes it one of the most important achievements in mathematical logic of the 20th century.

3.3. Formalization of Conditional Infinite Structures

To address the problem that infinite structures are difficult to characterize using logic, we present and prove a slightly weaker but still highly universal theorem. First, we provide several definitions.

Definition 13 (Relationship maintenance). Let be a structure where is a -ary relation. Let be an approximate sequence.

Relationship maintenance means:

Definition 14 (A precise definition of recursive approximation). The structure satisfies recursive approximation if and only if:

There exists a sequence where every satisfies:

Monotonicity:

Countability: for all n

Recursion: There exists a recursive function that computes the Scott statement for each

Density: (in appropriate topology)

Relationship maintenance: For all , where denotes the number of elements of the relation

Asymptotic uniqueness: Any two sequences are isomorphic to themselves or to each other after adding a finite number of elements from M.

Definition 15 (Topology of Scott’s statements space). We define a topology on the space of Scott statements, which makes the convergence exact. We assume that the space is complete under this topology.

Define as the space of all Scott statements. For , define the distance:

Here denotes the set of k-types that occur in a structure satisfying ϕ, and contains the “complete description” of all possible k-tuples in the structure .

Theorem 6 (Higher-order characterization theorems for recursive approximate structures)

. Suppose is an uncountable structure that satisfies recursive approximation and local finiteness. Then there exists a higher-order logic theory such that:

Here, we assume that higher-order logic can be infinitely quantified, that is, it satisfies the properties of infinite logic. We prove this conclusion step by step. First, we prove that the recursive approximation sequence is inherently unique.

Lemma 3 (Normality of approximate sequences)

. Assume satisfies recursive approximation, and and are two approximate sequences that satisfy the condition. Then there exists an increasing function such that:

Proof of Lemma3. By density, monotonicity, and asymptotic uniqueness, for any , there exists a sufficiently large m such that can be embedded in .

Vice versa. Combined with countability, we obtain an isomorphism. □

Next we define limit operations and related concepts.

Definition 17 (Limits of structural sequences)

. Let be an increasing countable sequence of structures. Definition:

If the union of every relation is well-defined in the limit.

Lemma 4 (Existence and uniqueness of limits). If satisfies the conditions for recursive approximation, then the limit exists and is isomorphic to the original structure .

Proof of Lemma4.

Existence: By monotonicity, is well-defined. The union of relations is well-defined by the relation-preserving property.

Uniqueness: By density, is dense in M. If has appropriate continuity (implied by the recursive approximation), then it is uniquely determined by the dense substructure. □

Next, we need to verify the convergence of Scott’s sequence of statements.

Theorem 7 (Convergence Theorem). Under the recursive approximation, if the local finiteness condition is additionally satisfied, then the Scott statement sequence converges to in the defined topology.

Proof of Theorem7. For fixed

k, consider the sequence:

For any

, we can choose

K so that

.

Since each inclusion is a subset relation, we can exploit local finiteness. Let

exist such that when

:

So there exists

such that when

:

Thus:

Thus, we obtain a Cauchy sequence. Based on completeness, we prove that this sequence has a limit. Let’s assume that its limit is . □

Next, we can construct a complete characterization theory:

Finally, we prove the Theorem6;

Proof of Theorem6. Assume , then has an approximate sequence that satisfies the same conditions.

By , the Scott statement for each is identical to the corresponding . By Scott’s theorem, for all n.

Construct an isomorphic sequence

. By monotonicity, consistency, and Lemma4,

can be combined into a global isomorphism:

Verifying that f is indeed an isomorphism: - Injectivity: by the injectivity and density of each - Surjectivity: by the surjectivity and limit properties of each - Homomorphism: by the preservation of relations. □

At this point, we have rigorously proved the theorem and obtained the most abstract formula for , . Clarifying will help researchers understand the logical nature of infinite structures and facilitate deeper research.

3.4. Formalization of Phenomena in Mathematics

Based on the formal characterization of finite and infinite mathematical structures, we finally conclude:

Theorem 8. Within the first-order and higher-order theoretical framework, almost all mathematical phenomena and mathematical structures can be effectively logically characterized.

Our theory demonstrates that, within the appropriate framework, nearly all mathematical phenomena—particularly discrete, algebraic, and finitely generated phenomena—can be meaningfully logically characterized. This is an important theoretical achievement that expands our understanding of the extent to which mathematics can be formalized.

However, the richness and complexity of mathematics mean that finding a precise logical expression is difficult. As mathematics develops, modern mathematics presents new challenges. Problems such as the explosion of parameter space, the breakdown of intuition, and insufficient tools make characterizing high-dimensional and abstract problems particularly difficult. This reminds us that mathematics has both a formal side and a side beyond formalism. A perfect logical characterization may be a guiding principle, guiding us to continuously deepen our understanding, but it should not be mistaken for a fully achievable ultimate goal.

4. State Expression in Economics and Sociology

The logical formalization of economic and sociological phenomena is of great significance. First, it provides a scientific theoretical foundation for these disciplines. By using precise mathematical language to eliminate the ambiguity and ambiguity inherent in traditional textual descriptions, it enables rigorous definitions and operational measurement standards for abstract concepts such as market efficiency, social capital, and institutional change. Second, logical formalization builds a bridge for interdisciplinary dialogue, enabling the comparison, integration, and mutual learning of rational choice theory in economics, social network analysis in sociology, and institutional theory in political science within a unified mathematical framework, thus promoting the comprehensive development of the social sciences. Third, it significantly enhances the scientific nature of empirical research. By formalizing theoretical assumptions, it makes research replicable and verifiable, and provides essential mathematical tools for computational social science in the big data era. Finally, at the level of policymaking and social governance, logical formalization enables complex socioeconomic policies to be based on rigorous logical reasoning and mathematical modeling, improving the scientific nature of decision-making and the accuracy of predictions. Overall, logical formalization is driving the transformation of economics and sociology from descriptive disciplines to predictive and explanatory sciences, providing more powerful theoretical tools for understanding and improving human society.

4.1. Logical Characterization in the Field of Economics

The logical characterization of economics is of fundamental significance to the development of the discipline and is also one of the hot issues in research[

19,

20,

21,

22]. First, logical representation can eliminate ambiguity and vagueness in economic theory. Traditional textual descriptions often allow for multiple interpretations, while logical formalization requires precise definitions of each concept and relationship, forcing theorists to clearly express their assumptions and reasoning. For example, when we say “demand is negatively correlated with price,” a logical representation requires us to specify under what conditions, for which goods, and over what timeframe this relationship holds true.

Furthermore, economics deals with complex systems involving multiple agents, multiple levels, and multiple variables, involving interactions between diverse actors such as consumers, businesses, and governments[

23]. When a theory becomes complex, natural language descriptions often fail to accurately capture all logical relationships and constraints. Logical representations provide a structured approach to organizing these complex relationships, ensuring the internal consistency and integrity of the theory[

24]. For example, when analyzing market equilibrium, we need to simultaneously consider multiple constraints, such as the supply equation, the demand equation, and market-clearing conditions. Logical representations can clearly demonstrate the logical dependencies between these conditions.

At the same time, considering that there are multiple schools and theoretical frameworks within economics, such as neoclassical economics, Keynesianism, institutional economics, etc[

25].Different theoretical frameworks utilize different conceptual systems and analytical methods, making academic dialogue difficult. Logical representation provides a unified language for different theories, enabling theoretical comparison, integration, and synthesis. Researchers can more easily identify commonalities and divergences between different theories, promoting the integration and development of theories.

Therefore, the importance of logical characterization in the field of economics is self-evident. Here we first consider the logical characterization of finite economic structures.

Definition 18 (Economic structure)

. An economic structure can be represented as follows:

Where:

A is a set of agents (individuals, enterprises, institutions, etc.)

is a relationship (social network, hierarchy, transaction relationship, etc.)

is a function (utility function, production function, decision rule, etc.)

is a process (market mechanism, institutional evolution, information dissemination, etc.)

Definition 19 (The logical language of economic structure). Basic language Contains:

Individual constants:

represent specific agent individuals, enterprises, organizations, etc.

Variables:

represent agent variables, t represents time variables, and s represents state variables

Predicate symbols:

: x is an agent

: represents the transition from state s to state under process

: indicates that the transition from state s to state under process satisfies the transition condition.

Theorem 9 (First-order representability of finite economic structures). Let

be a finite economic structure, that is:

-

1.

(Finite Agents)

-

2.

Every relation and function is defined over a finite field and has corresponding predicate and function representations in the base language.

-

3.

The process involves finite states and finite time.

Then there exists a set of first-order formulas Φ such that:

Proof of Theorem9.

Characterization of relationships: For each relation

:

Function description: For each function

(where the range

is finite):

Description of the process: For each process

, if it involves a finite state transition:

Since all components are finite, every formula is first-order, and completely characterizes the structure , we have proved the result. □

From the proof, we can see that structural finiteness has a profound impact on the construction of economic theory. It means that economic models need to pay more attention to boundary conditions, constrained optimization, and finite games. At the same time, finiteness also provides a more realistic foundation for economic analysis, making theoretical predictions more closely aligned with actual economic phenomena.

Given that in the real world, the number of market participants, the variety of resources and commodities, and time and space are all finite, we can further conclude.

Theorem 10. Within the theoretical framework of first-order and higher-order logic, almost all economic structures can be fully characterized.

Here, we give an example to verify how logic represents economic phenomena and structures. Lowercase letters represent variables.

Table 1.

Predicate Definition.

Table 1.

Predicate Definition.

| symbol |

definition |

|

The quantity q demanded by consumer i for good g at price p is q

|

|

i is a consumer |

|

g is a commodity |

|

p is a valid price (non-negative) |

|

q is a valid quantity (non-negative) |

|

Consumer i chooses a bundle of goods b to maximize utility under constraints |

|

Consumer i’s budget constraint under price p and income

|

|

Income of consumer i

|

|

The bundle b contains a quantity q of the good g

|

|

The supply of good g by firm f at price p is q

|

|

f is an enterprise (production unit) |

|

Firm f chooses input v and output to maximize profit under price p and factor price w1

|

Definition 20.

Definition of Supply and Demand:

4.2. Logical Characterization in the Field of Sociology

The reason why social structures require logical representations is closely related to their inherent complexity and abstractness, and these needs are even more pressing than in economics[

26,

27,

28].

The need to handle relational complexity is a core motivation for logical representations of social structure. Social structure is essentially composed of a network of multiple relationships between individuals, including kinship, power, economic, and cultural relationships. These relationships often intersect and overlap, forming a multidimensional, complex network. Natural language struggles to accurately describe structural features such as transitivity, symmetry, and hierarchy within such networks. Logical representations can formalize the precise properties of these relationships, such as the transitive relationship “If A is B’s superior, and B is C’s superior, then A is C’s superior.”

The need to operationalize abstract concepts is another key factor. Sociology is replete with abstract concepts, such as social status, cultural capital, social cohesion, and institutional legitimacy. These concepts often lack intuitive physical counterparts, and their meanings can shift in different contexts. Logical representations force researchers to clearly define the connotations and extensions of these abstract concepts and establish logical relationships between them, making theoretical discussions more precise and operational[

29].

The first-order logic description of social structure is similar to that of economic structure. Here, we only give the theorem.

Theorem 11 (First-order representability of finite social structures). Let

be a finite social structure, that is:

-

1.

(finite agent)

-

2.

Each relation and function is defined over a finite domain and has corresponding predicate and function representations in the base language.

-

3.

The process involves finite states and finite time.

Then there exists a set of first-order formulas Φ such that:

Similarly, considering the limitations of social structure, we can draw a conclusion.

Theorem 12. Within the theoretical framework of first-order and higher-order logic, almost all social structures can be fully characterized.

Through logical representation, sociology can not only describe social phenomena more accurately, but also discover hidden social laws, providing more powerful theoretical tools for understanding and improving social structure.

Here, we give an example of logical representation.

Table 2.

Semantic interpretation table of sociological predicates.

Table 2.

Semantic interpretation table of sociological predicates.

| predicate |

Semantic meaning |

|

x and y are friends |

|

x smoking |

|

x is affected by y

|

|

x has a higher probability of smoking |

|

x and y are in the same social network |

Through the given predicate, we can express the state of the smoking phenomenon in sociology.Here, HigherSmokingProbability(x) is abbreviated as HSP(x).

Definition 21 (Expressions related to smoking).

5. Computer Field State Expression

In computer science, logic plays an irreplaceable role as a fundamental tool for expressing states. In program verification, Hoare logic precisely describes the state of each execution point of a program through preconditions, postconditions, and invariants, enabling rigorous proof of program correctness. In database systems, first-order logic is not only used to define the semantics of query languages, but also characterizes the legal state space of data through integrity constraints. In the field of formal methods, temporal logic (such as LTL and CTL) can express the dynamic behavior and safety properties of systems in the time dimension, providing a mathematical foundation for modeling concurrent and real-time systems. Planning problems in artificial intelligence are essentially about finding a path from an initial state to a target state in the state space described by logic. In hardware design, Boolean logic directly corresponds to the physical state of circuits, enabling the design of complex digital systems. This abstract expressive power of logic not only provides a unified mathematical framework for modeling complex systems but, more importantly, enables automated reasoning and verification. From compiler optimization analysis to operating system resource management, from network protocol correctness verification to interpretability analysis of machine learning models, logic plays a critical role in translating intuitive concepts into computable forms[

30,

31,

32].

5.1. Boolean Algebra and the Formalization of Computer Systems

Boolean algebra and logical representation are core areas of computer science and mathematical logic[

33,

34]. First, we verify that Boolean algebra can be formalized using first-order logic.

Theorem 13 (The expressive power of Boolean algebra and first-order logic). All axioms and operations of Boolean algebra can be expressed using first-order logic (FOL).

Proof of Theorem13. Boolean algebra is defined as: a set

B, binary operations

, unary operations ¬, constants

, and the following axioms:

Given that Boolean algebra is a finite mathematical structure, all its structures and properties can be formalized using first-order logic. Therefore, the theorem is proved. □

Boolean algebra is the foundation of computer systems. The logic gates in digital circuits, conditional branching in programs, propositional calculus, and automata are all based on Boolean algebra. Operations, states, and transitions can all be reduced to Boolean algebraic expressions.

Because the entire content of Boolean algebra can be expressed using first-order logic, and computer systems can be reduced to Boolean algebraic structures, its core content can also be expressed using first-order logic. Practical applications such as model checking, hardware verification, and theorem proving have extensively employed first-order logic for modeling and reasoning.

Theorem 14. Computer systems can be formally expressed in first-order logic.

5.2. Predicate Logic Description of a Turing Machine (TM)

Definition 22.

Similar to finite state machines, Turing machines can be formally expressed. A deterministic Turing machine (DTM) can be represented as a seven-tuple:

Where:

Q is a finite state set.

Γ is the set of tape symbols (including the blank symbol ⊔).

is the set of input symbols (excluding ⊔).

is the state transition function, where L and R indicate whether the read/write head moves left or right.

is the initial state.

are the accept and reject states, respectively.

To represent a Turing machine, we can define the following predicates and give the corresponding state expressions:

Definition 23 (Predicate Definition and State Expression). The predicates and states in a Turing machine can be expressed as:

State: indicates that q is a state.

Tape Symbol: indicates that a is a tape symbol.

Tape content: indicates that a is the tape symbol at time t and position p.

Read/Write Head Position: indicates that the head is at position p at time t.

Transition function: represents state transition, where d is the direction.

Initial state: represents the initial state q.

Accept state (similar to the rejection state): indicates that q is an accepting state.

Based on the above definition of predicates and the corresponding Turing machine state representation and state transition representation, we derive the theorem:

Theorem 15 (Turing Machine State Representation). For any Turing machine, its input, output, and state transition behavior over a relevant time set can be described using a state set.

Before Turing, concepts such as “computation,” “algorithm,” and “efficient process” were intuitive. Mathematicians knew what computation was, but could not give a rigorous mathematical definition. The logical representation of the Turing machine was the first to transform these intuitive concepts into precise mathematical objects: state sets, symbol sets, transition functions, initial states, and accepting states. This formalization enables us to use mathematical methods to study the properties of computation itself[

35].

5.3. Mathematical Formalization of Neural Networks

Neural networks (NNs) are machine learning models that mimic the structure and function of biological neural systems, capable of learning complex patterns from data and making predictions or decisions[

36]. They are a core technology in deep learning and are widely used in fields such as computer vision, natural language processing, and speech recognition.

First, let’s briefly introduce neural networks. A neural network can be represented as a function

, whose hierarchical structure is decomposed into:

Where: input layer:

, hidden layer:

, output layer:

, weight matrix:

, bias vector:

, activation function:

Single neuron calculation:

Neural networks, by simulating the connections of the human brain, enable efficient modeling of complex data. With advances in computing power and algorithms (e.g., GPUs and attention mechanisms), their capabilities are continuously expanding, becoming the driving force behind the AI revolution.

Next, we demonstrate that the relevant aspects of neural networks can be formally expressed.

Proposition 1. Neural networks can be formally expressed in first-order and higher-order logic.

Proof of Proposition1. The first step is to logically represent a single neuron in a neural network.

Definition 24 (Neuron Triplet). A neuron can be represented as , where represents the weight vector, represents the bias term, and represents the activation function.

Using the neuron triple model, we can see that the neuron input-output relationship can be logically represented as follows:

Next, we express the activation function in the neural network. Because activation functions possess strong mathematical properties and are finite mathematical structures, they are naturally amenable to logical expression.

Finally, we demonstrate the logical representation of the network topology. Taking a simple fully connected layer as an example:

Feedforward Network:

indicates the connection between

, and

indicates the

lth layer.

Hierarchical Combination:

indicates the hierarchical combination structure of

x.

Combinatorial Completeness: If the

lth layer can be represented as

, then the

th layer can be represented as:

Thus, we have proved the conclusion. □

According to the theorem, from a theoretical perspective, there is a profound equivalence between neural networks and logical systems. Neural networks can discover strategic patterns that humans have never discovered. If these patterns can be expressed in logical form, they may be transformed into verifiable scientific theories. This fusion is not just a technological advancement; it also represents a deepening of our understanding of the nature of intelligence: intelligence requires both the ability to learn from experience and the ability to reason based on rules, and the logical representation of neural networks is the key bridge connecting the two.

5.4. Formal Expression of States in Computer Science

According to previous proofs, computer systems, Turing machines, and neural networks can all be formalized using first-order and higher-order logic. Scholars have also formalized phenomena such as computational concepts, programming languages, and algorithmic processes.[

11,

37,

38]. Furthermore, emerging problems in computer science can be gradually formalized using the proof process of neural networks. Based on this, we draw a comprehensive conclusion.

Theorem 16. All phenomena in computer science can be formalized using first-order and higher-order logic.

Theorem 16 demonstrates that logic provides a unified framework for expressing different computational models. Logical formalization has transformed computer science from an engineering craft into a rigorous scientific discipline, providing powerful tools for understanding and controlling complex systems.

6. State Expression in Natural Language Domain

Natural languages, such as Chinese, English, and Arabic, are the languages humans use in everyday life. They are essential tools for communicating ideas and conveying information. In contrast to formal languages, they possess unique properties. Natural languages are richly expressive, capable of expressing the myriad worlds, complex emotions, and abstract concepts. This chapter introduces Montague semantics, explores the rules governing the grammar and semantic translation of natural languages, and achieves a formal understanding of natural languages through the principles of formalized mathematical logic.

6.1. Montague Semantics

Montagu semantics, also known as Montagu grammar, is a formalized approach to the study of natural semiotics, particularly intensional semantics. It represents a new stage in the development of linguistics and logic.

Montagu’s research began with the concept of categories, dividing English syntax into distinct categories. He then established 17 general rules for the formation of all English syntax. He then defined meaningful expressions, used recursion to represent meaningful sets, and explained them using model theory. Finally, Montagu defined 17 corresponding rules for semantic translation, corresponding to the 17 rules for the formation of syntax[

39,

40].

Based on Montagu’s work, Bennett conducted further research. He refined the English categories, dividing adjectives into separate categories; introduced more complex grammatical and semantic translation rules, expanding the rules from 17 to 35, and provided a solid theoretical foundation for language research using Montagu semantics[

41].

6.2. Study of English Ambiguity

Correctly handling linguistic ambiguity is an important indicator of semantic comprehension. Here, we use Montague Grammar to provide an interpretation of ambiguity.

“At least one person likes the book” is a common ambiguous phrase in English. The ambiguity of “at least one person likes the book” stems from the ambiguity of the quantifier scope. Without context, “the book” could refer to a specific book or to a general term.

The semantics of the sentence “At least one person likes the book” can be formally modeled using the calculus, with two possible interpretations: a broad interpretation and a narrow interpretation.

In the broad interpretation, “the book” refers to a specific book

b. The logical form of the entire sentence is:

Where:

The specific

calculus combination process is as follows:

In the narrow-scope interpretation, “the book” is not a specific object but a quantifiable range. The logical form of the sentence is:

Where:

indicates that b is a book;

indicates that there exists at least one person x, there exists a book b, and this person likes book b.

The specific

calculus combination process is as follows:

By modeling the

calculus, the sentence “At least one person likes this book” can capture the following two semantic interpretations:

Broad interpretation: There is at least one person who likes this particular book:

Narrow interpretation: There is a book and at least one person likes it:

Similarly, the ambiguous phenomenon of “Every student read a book” has been extensively studied and interpreted. The quantifier scope ambiguity involved in this issue is an active frontier in semantic research, continuing to drive theoretical and technological developments[

42]. Studying such issues can further advance the research and development of natural semantics.

6.3. Optimizing Syntax and Semantic Translation Rules

Although Montagu, Bennett, and others have established detailed rules for English semantics and grammar, which later generations can simply apply directly, many issues still need to be resolved in the actual translation process.

6.3.1. Conjunction Rules

Among Montagu’s 17 rules, S11 and S12 deal with conjunction, defining parallel sentences and parallel verbs, respectively. Among Bennett’s 35 rules, S28 deals with conjunction, defining only parallel verbs. However, as we know, conjunctions of nouns and noun phrases occur very frequently in natural language. Surprisingly, neither Montagu nor Bennett provide corresponding grammatical rules for this phenomenon. This is because conjunctions of nouns and noun phrases require the verb to become plural, and to simplify expression, no corresponding grammatical rules were defined. However, given the high frequency and widespread use of nouns and noun phrases, and to help beginners better grasp the relevant content, we provide the following additional rules:

Definition 25 (Grammatical Rules for Conjunction of Nouns and Noun Phrases). If , then . If , then . Here, . And when the object of the conjunction becomes the subject, the corresponding verb becomes plural.

Definition 26 (Translation Rules for Conjunctions of Nouns and Noun Phrases). If or , and is translated as , then is translated as . When the conjunction object serves as the subject, the corresponding verb is translated into its plural form.

6.3.2. Adjective Rules

Among Bennett’s 35 rules, the one concerning adjectives is S10. We give its original definition:

Definition 27 (S10). If and , then , where

-

(a)

if γ contains an occurrence of a member of , then ;

-

(b)

otherwise .

Bennett argues that using S10 can resolve the English grammatical phenomenon of adjective + noun. However, let’s consider the following example: John’s mother. According to Bennett’s definition, John’s does not fall into the basic category of adjectives, so S10 cannot be used for translation. We must instead use S5.

Definition 28 (S5). S5.If and , then , where

-

(a)

if , then ;

-

(b)

otherwise .

Consider John’s mother to be equivalent to mother of John. This can be translated:

While there’s certainly nothing wrong with translating “John’s mother” this way, treating “John’s mother” and “mother of John” as equivalent loses the distinction between the two grammatical structures. Furthermore, the resulting translation is often less concise and clear, hindering the reader’s intuitive understanding. Therefore, we provide supplementary rules for these situations.

Definition 29 (Grammar rule). If or , then , where

-

(a)

If , then ;

-

(b)

Otherwise .

Definition 30 (Semantic Translation Rules). If or , and α is translated as , then

-

(a)

is translated as ;

-

(b)

John’s is translated as .

-

(b)

In other cases, is translated as .

Using the new rules, we can retranslate John’s mother:

In comparison, the translation using the new rules is more concise and clear, making it easier for readers to grasp the grammatical structure.

6.3.3. Clause Rules

For the sake of brevity, neither Montagu nor Bennett discussed clause rules in detail, instead focusing on the typical relation “such that.” Some might question whether each clause has a specific function and introductory phrase, expressing different logical relationships depending on the context. Since their functions are not identical to “such that,” does this mean that the same rules cannot be applied universally?

Indeed, “such that” primarily expresses a result or condition. Commonly used attributive clauses, such as modifiers and adverbial clauses, often express time or cause, differ significantly from “such that.” However, these commonly used clauses are structurally simpler than standard relative clauses. Generally speaking, one can emulate Montagu’s approach to translation by modifying or simplifying Montagu’s rules or by transforming the clause form.

Here, we provide a case study: the man whom Mary loves.

Combined results:

After

transposition, brackets, and upper and lower rules, the final result is:

The core insight of Montague semantics lies in placing natural language within a formal framework as rigorous as that of mathematics and logic. By supplementing these rules, scholars can better understand natural language through logic. Formal logic is not just an abstract mathematical tool; it is a key approach to understanding and modeling the most complex human cognitive abilities. As artificial intelligence progresses toward general intelligence, the formal methodology represented by Montague semantics will continue to play an irreplaceable role.

6.4. Formalization of Natural Languages

Scholars such as Montague have provided comprehensive tools and detailed introductions to the formalization of English, a natural language. Furthermore, combined with the rules subsequently added by scholars, it can be argued that English can be fully formalized. Similarly, other natural languages can be formalized using similar methods. Alternatively, given the intertranslatability between English and other languages, they can be directly converted into English for formalization.

In short, we can conclude.

Theorem 17. All natural languages can be fully formalized using first-order and higher-order logic with appropriate expansion of symbols and rules.

The importance of formalization of natural languages ultimately lies in the scientific method it provides for understanding the essence of human intelligence. Language is not only a tool for communication but also a vehicle for thought, a container for knowledge, and a medium for the transmission of culture. Formalizing language is a mathematical modeling of human cognitive abilities and a scientific exploration of the essence of intelligence.

7. Conclusion and Outlook

This paper systematically investigates the logical formalization of object states, proposing and demonstrating a rigorous and universally applicable formalization framework for revealing the nature of information and its interdisciplinary applications. The paper first reviews classical information theory and its shortcomings, noting the current lack of a unified and rigorous mathematical definition of the core concept of “state.”

To this end, this paper establishes a universal representation system for information states based on first-order and higher-order predicate logic, combined with modal logic and calculus, addressing the current lack of formal representations for states. This paper enumerates typical states from various fields, including mathematics, economics, sociology, computer science, and natural language, and rigorously proves that these states can be formalized using first-order and higher-order logic. Because the proof methods used in these fields can be extended to other fields, this paper demonstrates a universally applicable method for representing states in any domain: formalization using first-order and higher-order predicate logic.

Thus, first-order and higher-order logic are not merely technical tools but also cognitive bridges for understanding the unity of the world. They integrate scattered fragments of knowledge into coherent theoretical systems, elevate local understandings of phenomena into global conceptual frameworks, and transform static descriptions of states into dynamic reasoning processes. In this sense, logic has truly become a universal bridge connecting states across various fields, a universal language that enables communication across fields and provides humanity with the most fundamental and powerful mathematical tools for understanding and transforming the world.

Through the formalization of states, objective information theory has been further refined and developed, deepening research on the nature of information and expanding its scope from the classic Shannon framework. Many pressing problems in information science can be transformed into logical problems. By studying the properties of logical language and drawing on proven conclusions and axioms from logic, we can clarify the meaning of information and guide the development of information research.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Professor Xu for his guidance all the time. He has provided me with great help in writing, content organization, topic selection, etc. Without him, I would not have been able to complete this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors have identified and declared that there are no personal circumstances or interests that may be perceived asinappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of the reported research results. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OIT |

Objective Information Theory |

| FOL |

First-order predicate logic |

| HOL |

Higher-order predicate logic |

References

- N. WIENER. Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2019.

- C. E. Shannon. The mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech, 27:379–423, 1948. [CrossRef]

- J. von NEUMANN. Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik, volume 38. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1971.

- A. N. KOLMOGOROV. Three approaches to the quantitative definition of information. International journal of computer mathematics, 2(1-4):157–168, 1968. [CrossRef]

- MCGOWAN A T. User and information dynamics: Managing change. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 78:327–329, 1990.

- XU. J, MA. X, SHEN. Y, et al. Objective information theory: A sextuple model and 9 kinds of metrics. 2014 Science and information conference. IEEE, pages 793–802, 2014. [CrossRef]

- XU. J, MA. X, TANG. J, et al. Research on model and measurement of objective information. Science China Information Sciences, 45(3):336–353 (In Chinese), 2015.

- XU. J, LIU. Z, WANG. S, et al. Foundations and applications of information systems dynamics. Engineering(Beijing, China), 27:254–265, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Alan G Hamilton. Logic for mathematicians. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- P. B. ANDREWS. An Introduction to Mathematical Logic and Type Theory: To Truth Through Proof: vol 27. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Jianfeng Xu. Information science principles of machine learning: A causal chain meta-framework based on formalized information mapping. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.13182, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Richard G Swan. K-theory of finite groups and orders, volume 149. Springer, 2006.

- Rudolf Lidl and Harald Niederreiter. Finite fields. Number 20. Cambridge university press, 1997.

- Leonid Libkin. Elements of finite model theory, volume 41. Springer, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Chen Chung Chang and H Jerome Keisler. Model theory, volume 73. Elsevier, 1990.

- Richard Dedekind. Was sind und was sollen die zahlen? In Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen?. Stetigkeit und Irrationale Zahlen, pages 1–47. Springer, 1965. [CrossRef]

- Giuseppe Peano. Arithmetices principia: Nova methodo exposita. Fratres Bocca, 1889.

- Dana Scott. Logic with denumerably long formulas and finite strings of quantifiers. In The theory of models, pages 329–341. Elsevier, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Gerard Debreu. Theory of value: An axiomatic analysis of economic equilibrium, volume 17. Yale University Press, 1959.

- Yoav Shoham and Kevin Leyton-Brown. Multiagent systems: Algorithmic, game-theoretic, and logical foundations. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- John Geanakoplos. Three brief proofs of arrow’s impossibility theorem. Economic Theory, 26(1):211–215, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Ulle Endriss. Logic and social choice theory. 2012.

- W Brian Arthur, Steven N Durlauf, and David A Lane. The economy as an evolving complex system ii. adison wesley. Reading, MA, 1997.

- Jaakko Hintikka and Jack Kulas. Anaphora and Definite Descriptions: Two Applications of Game-Theoretical Semantics, volume 26. Springer Science & Business Media, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Daniel M Hausman. The inexact and separate science of economics. Cambridge University Press, 2023.

- James Samuel Coleman. Introduction to mathematical sociology. 1964.

- Stanley Wasserman and Katherine Faust. Social network analysis: Methods and applications. 1994.

- Patricia H Thornton, William Ocasio, and Michael Lounsbury. The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Stephen P Borgatti, Martin G Everett, Jeffrey C Johnson, and Filip Agneessens. Analyzing social networks using R. Sage, 2022.

- Michael Huth and Mark Ryan. Logic in Computer Science: Modelling and reasoning about systems. Cambridge university press, 2004.

- Charles Antony Richard Hoare. An axiomatic basis for computer programming. Communications of the ACM, 12(10):576–580, 1969. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin C Pierce. Types and programming languages. MIT press, 2002.

- George Boole. The mathematical analysis of logic. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 1847.

- George Boole. An investigation of the laws of thought: on which are founded the mathematical theories of logic and probabilities, volume 2. Walton and Maberly, 1854.

- Alan Mathison Turing et al. On computable numbers, with an application to the entscheidungsproblem. J. of Math, 58(345-363):5, 1936. [CrossRef]

- Warren S McCulloch and Walter Pitts. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. The bulletin of mathematical biophysics, 5(4):115–133, 1943. [CrossRef]

- Glynn Winskel. The formal semantics of programming languages: an introduction. MIT press, 1993.

- Hartley Rogers Jr. Theory of recursive functions and effective computability. MIT press, 1987.

- Richard Montague. English as a formal language. 1970.

- Richard Montague. The proper treatment of quantification in ordinary english. In Approaches to natural language: Proceedings of the 1970 Stanford workshop on grammar and semantics, pages 221–242. Springer, 1973. [CrossRef]

- Michael Bennett. A variation and extension of a montague fragment of english. In Montague Grammar, pages 119–163. Elsevier, 1976. [CrossRef]

- Robin Cooper. Quantification and syntactic theory, volume 21. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).