1. Introduction

Supply chains are logistic networks of suppliers, manufacturers, warehouses, distributors, and retailers [

1]. The raw materials, intermediate products, and finished products flow between these facilities. Disruptions in supply chain logistics can cause shortages [

2]. The consequences of shortages can range from negligible to devastating. For example, drug shortages have adverse economic and clinical effects on patients [

3]. Significant research is underway to characterize the impact of shortages on supply chains.

Walid Klibi et al. [

4] proposed a three-phase hazard modeling approach to develop a set of possible scenarios including disruptions and characterize their impact on the supply chain. While they characterize the impact of disruptions on supply chains, including average capacity loss and loss of operational days, they haven’t explicitly quantified the overall supply chain failure, from individual facility level failure. Sheffi and Rice [

5] qualitatively distinguish between increasing flexibility and adding redundancy to reduce supply chain vulnerability. Pavlov et al. have used network graphs to quantify supply chain resilience using a hybrid fuzzy-probabilistic method, but they do not consider the throughput of the supply chain [

6]. Simchi-Levi et al. focus on quantifying the duration of a supply chain disruption and have developed a time-to-recover model that uses a network graph to fail a node and calculate the impact iteratively [

8,

9].

Mahmoud M. Bassiouni et al. propose a Deep Learning (DL) methodology to predict the risk associated with the intercity export of shipment [

9]. They performed the study using the online data set: “United States Supply Chain Information for COVID-19”. Results show that one of the proposed models is about 100% accurate in predicting the risk of shipment to a target location under COVID-19 restrictions. Bastian Engelking et al. collaborated with an automotive case study company on an Action Design Research (ADR) project to develop a Machine Learning (ML) prototype for Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM) [

10]. The ADR process results in a framework of design principles for applying ML in SCRM.

Edward Elson Kosasih and Alexandra Brintrup propose using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to reduce supply chain risk by identifying potential links in the supply chain network unknown to the buyer [

11]. Additionally, Edward Elson Kosasih et al. have developed a framework that combines GNNs and knowledge graphs to uncover hidden risks in supply chains [

12]. Ajmal Aziz et al. propose a novel method for learning a representation of a supply chain network as a heterogenous graph [

13]. The Graph Representation Learning (GRL) method is used in the study to estimate missing data from supply chain entities to increase visibility into interdependencies. Thus, we apply graph neural networks and graph representation learning to analyze supply chain risk.

Typically, the black box nature, that is, explanations lacking results of Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms or ML models, challenges their use [

14]. Hence, Andreas Holzinger et al. [

15] motivate using GNNs to enable information fusion for multi-modal causability. Causability is the extent to which explaining a statement to a human expert achieves a specified level of causal understanding with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use. Apart from causability another important aspect to consider is the trustworthiness of the AI or Neural Network (NN). In [

16], Andreas Holzinger suggests using a human in the loop for certain tasks to promote reliability and trust in AI while ensuring that humans remain in control. Given data availability, we can consider the GNN and GRL methods to analyze supply chain risk in future work.

Munoz et al. conducted a simulation-based study to construct a comprehensive operational supply chain resilience metric encompassing multiple echelons and dimensions [

17]. They used disruptions as inputs to quantify the transient response of the supply chain effectively. Rathore et al. focused their analysis on the food supply chain within developing countries [

18]. They employed the grey analytical hierarchy process and the grey technique for order performance to develop an extensive risk index, providing a holistic perspective on the subject.

Similarly, Faisal et al. employed graph theory and interpretive structural modeling to formulate a risk index that addressed information risks impacting the supply chain [

19]. Tarei et al. utilized the DEcision-MAking Trial and Evaluation Laboratory Analytical Network Process (DEMATEL-ANP) to model various risk drivers and sub-risks, enabling the quantification of corresponding indexes [

20]. The authors demonstrated the application of this method in a case study centered around the petroleum supply chain.

Sharma et al. adopted the fuzzy synthetic evaluation method to quantify risks faced by the pharmaceutical supply chain in India [

21]. Their findings indicated that the most significant contributing risks were counterfeit drugs, demand fluctuations, and customer loss due to poor service performance by partners. Moreover, the primary risks identified were demand, finance, and logistics. Lawrence et al. developed a Bayesian causality model to represent the supply chain and quantify its cumulative risk [

22]. Predictive inference reasoning and sensitivity analysis were employed to analyze the results of this quantification. Ramesh K.T. et al. utilized a hybrid approach, combining expert judgment with quantitative data analysis, to establish an overall inbound supply risk score [

23]. The authors employed DEMATEL-ANP for data analysis and demonstrated their framework within the context of the Indian electric supply chain.

Qazi et al. devised a framework that integrated Bayesian networks and game theory to quantify the probability of high development costs and time [

24]. Lau et al. proposed a federated learning-enabled multi-criteria risk evaluation system to systematically identify, assess, and prioritize risks within the cold supply chain [

25]. Cube et al. presented a discrete event simulation-based method to quantify monetary supply risk [

26].

From the literature review, we can conclude that there is a need to develop a supply chain risk quantification method that,

represents the supply chain information in a way that enables decision-making,

relates facility-level failure with supply-chain-level failure,

and can be automated using a software package.

In “A Quantitative Approach to Assess the Likelihood of Supply Chain Shortages,” we defined a methodology to quantify the failure probability of the throughput of a supply chain [

27]. Based on the methodology, we have developed the SUpply chain Probabilistic Risk Assessment tool (SUPRA) to quantify pharmaceutical drug shortages presented in this paper. We have built SUPRA to address the supply chain shortage quantification research needs identified in the literature review. This paper’s organization is as follows: Section two briefly summarizes the supply chain shortage risk quantification methodology developed in [

27]. Section three describes the development of SUPRA and gives its results. Section four presents the development of SUPRA, and section five introduces new postprocessing methods for SUPRA results. Section six concludes the paper, and section seven discusses future work.

2. Overview of Supply Chain Shortage Quantification

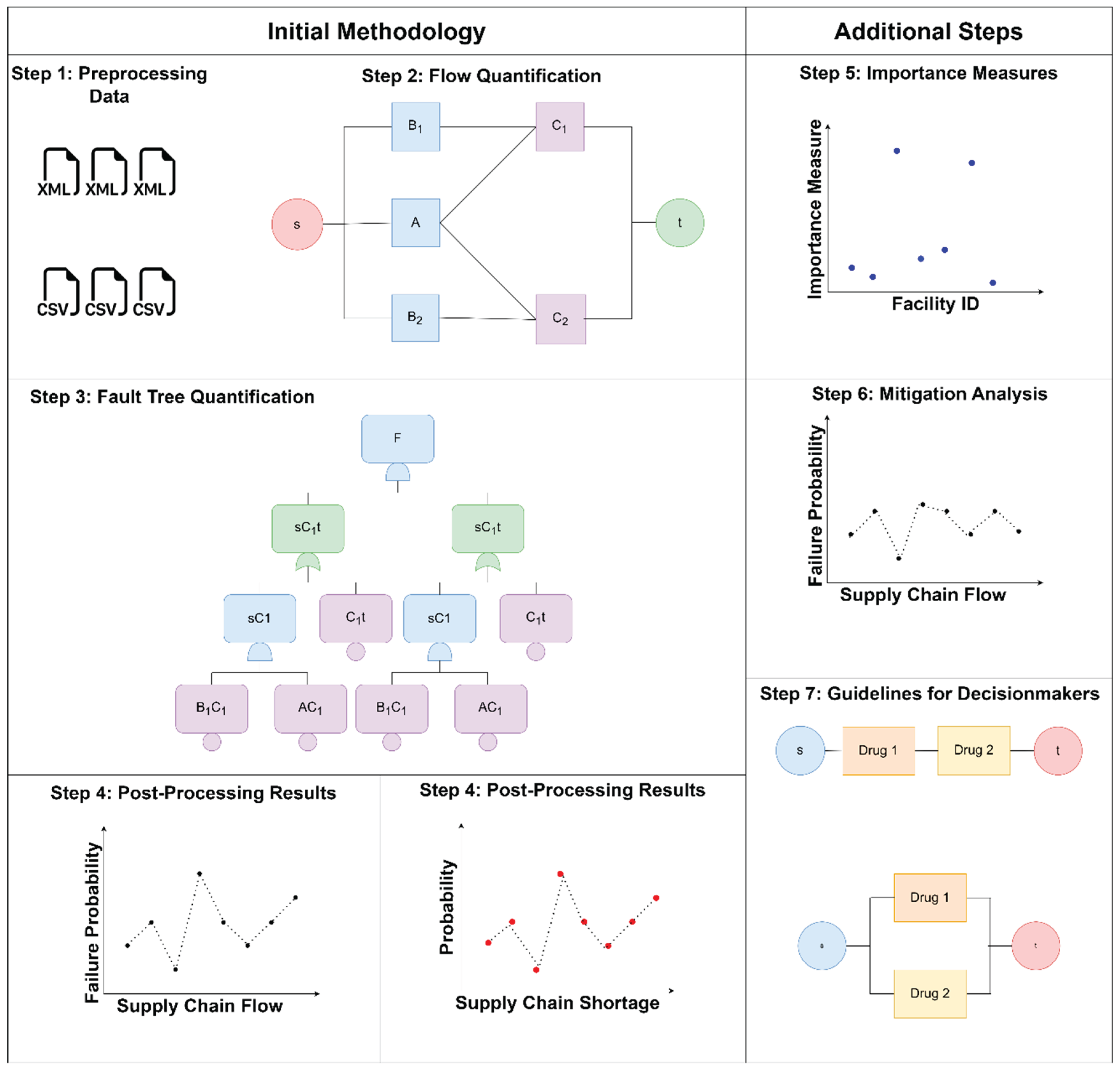

In [

27], we described a methodology to represent supply chains as network graphs and fault trees to quantify the supply chain flow and failure probability, respectively, as shown in

Figure 1. The first step is to organize the supply chain data in a format suitable for analysis, such as a network graph. We then quantify the total supply chain flow, given facility level flow. After flow quantification, we can use a fault tree solver to generate and quantify the supply chain fault trees. We organize the results of the flow and failure probability quantifications in postprocessing to derive insights from the results. The failure probability vs. flow graph compares the susceptibilities to failure of all the facilities in the supply chain. Given a certain demand value, we can plot the probability vs. shortage similarly, which gives a shortage risk profile.

This paper presents the adaptation of the shortage risk quantification methodology into a software package, SUPRA. Additionally, we present extra steps for postprocessing results, as shown in section four and

Figure 1. The extra steps include quantifying importance measures, mitigation analysis, and guidelines for decision-makers.

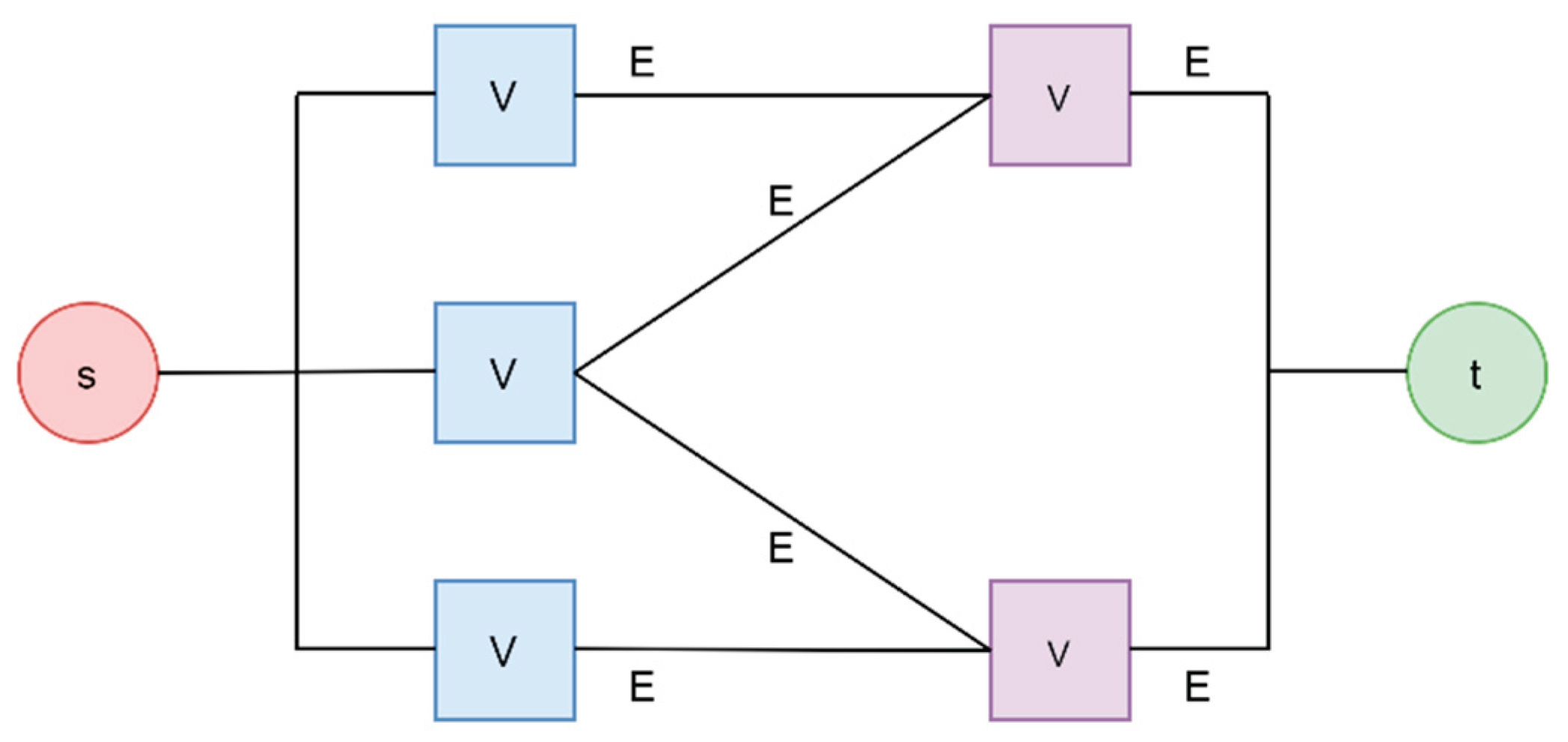

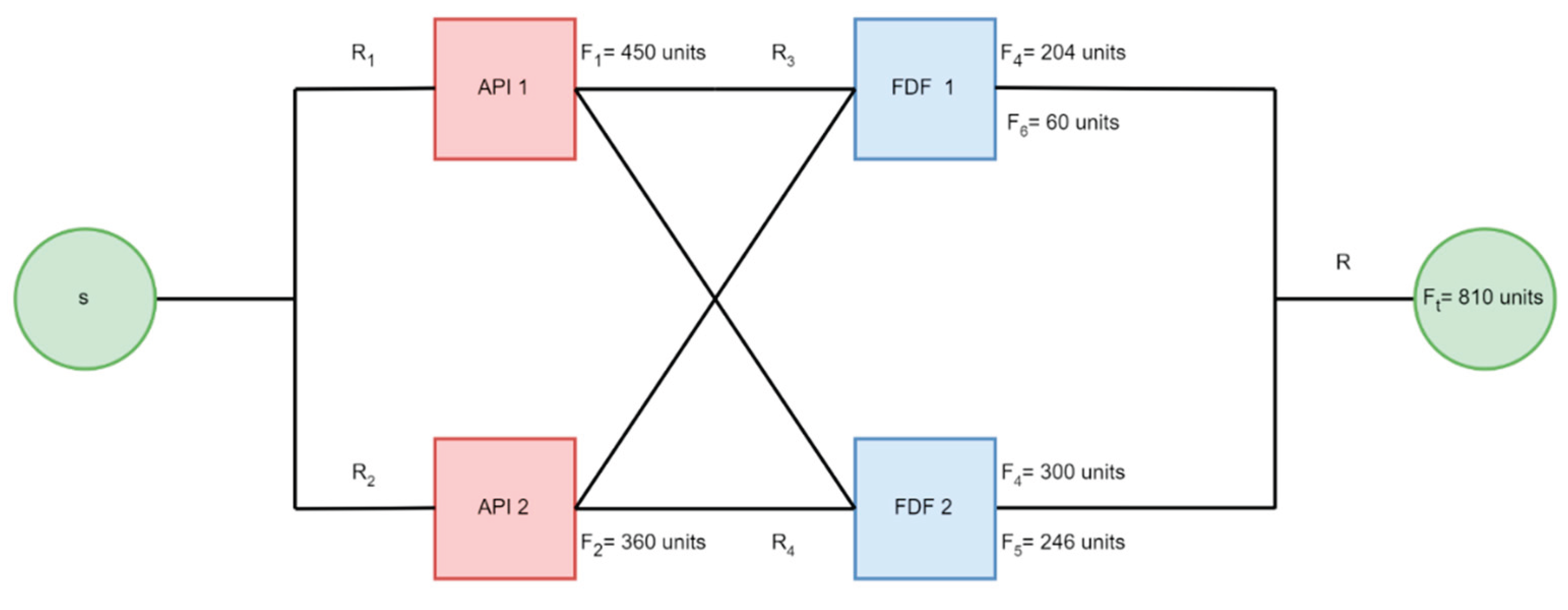

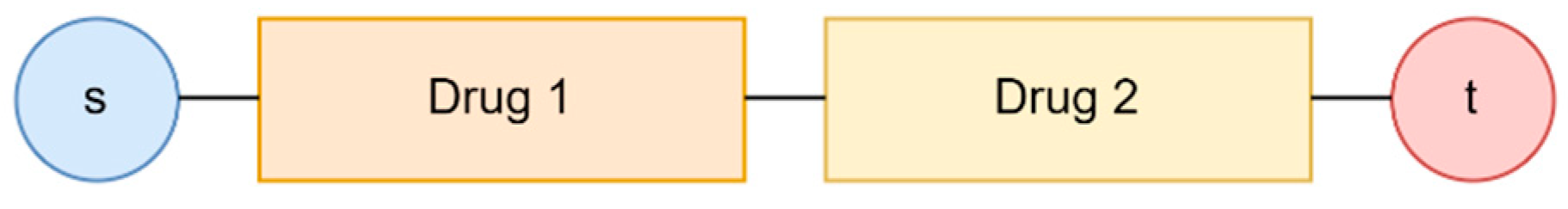

The vertices of the network graph, as shown in

Figure 2, denoted as ‘V,’ represent the facilities and facility failure probabilities. In contrast, the graph’s edges represent the flow of goods between the facilities, denoted by ‘E’ in

Figure 2. The nodes’ s’ and ‘t’ represent the source and termination of the supply chain and are not included in the quantification process. We use the network graph representation of the supply chain to calculate the total throughput and visualize the supply chain. The fault tree of the supply chain gives the supply chain failure probability. We can get the shortage probability and generate a risk profile by relating the supply chain failure probability with the flow.

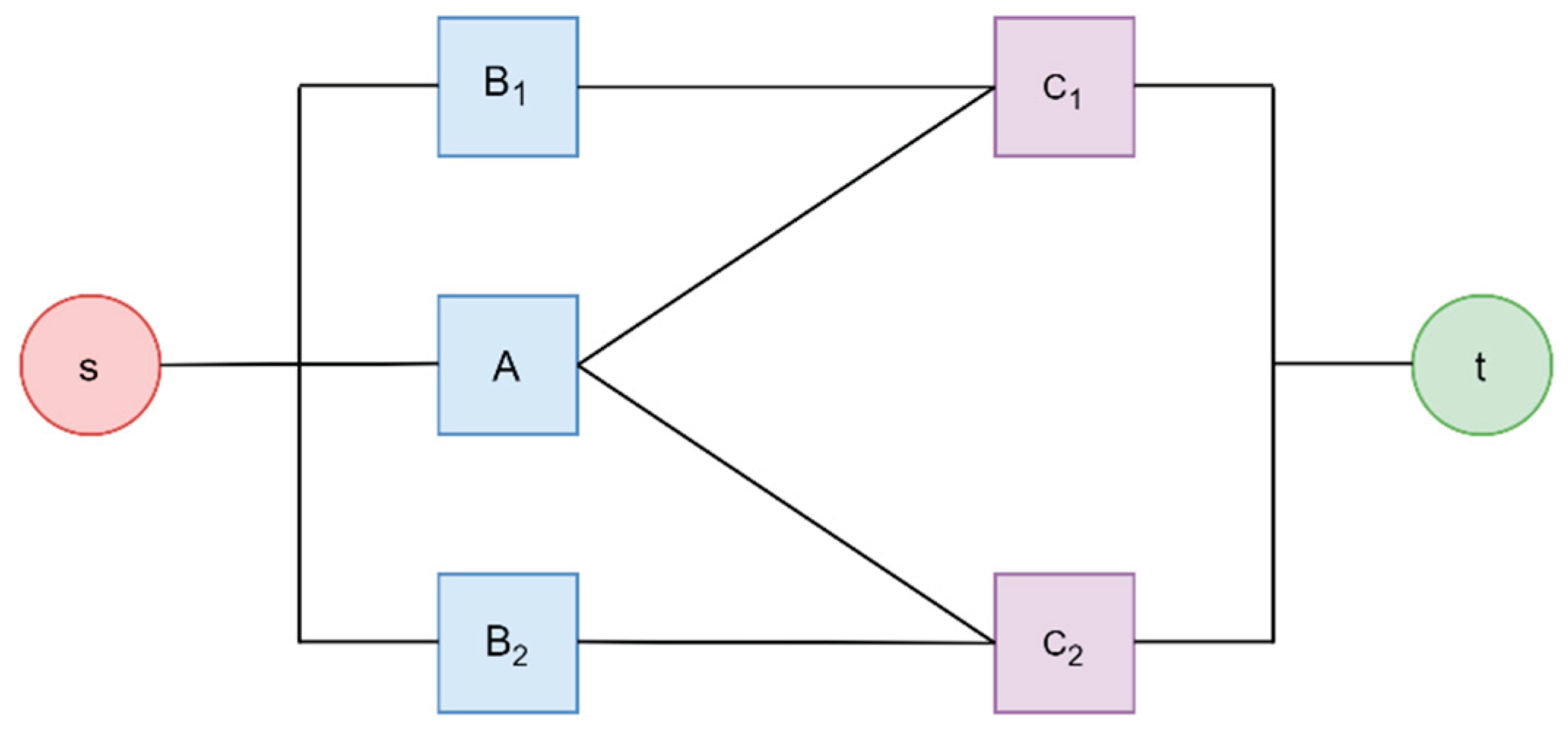

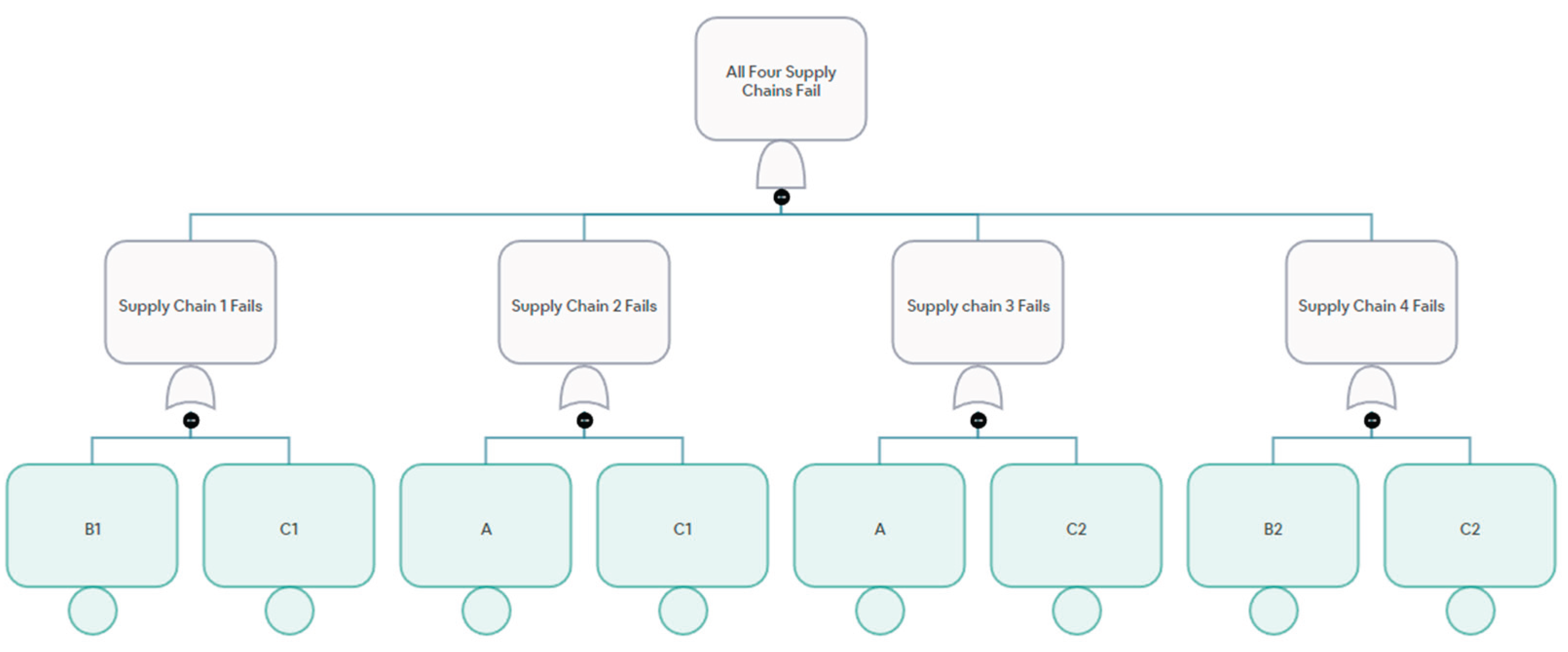

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show supply chains represented as network graphs and fault trees.

3. Development of SUPRA

We first began the development of SUPRA to quantify pharmaceutical drug supply chain shortage risk. Therefore, the presentation of the tool in this paper relies on pharmaceutical drug supply chain taxonomy. The supply chain facilities that we considered for drug manufacturing are the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and the Finished Dosage Form (FDF) facilities, as shown in

Figure 5, based on the system reliability approach given by Tillman et al. in [

28]. The facilities have been assigned data points such as a facility ID, a reliability probability (R) or a failure probability (F=1-R), and a facility flow (f).

Using SUPRA, we can read input data from an Excel sheet (or optionally as a Pandas dataframe) to make a fault tree, quantify it, and post-process the results [

29].

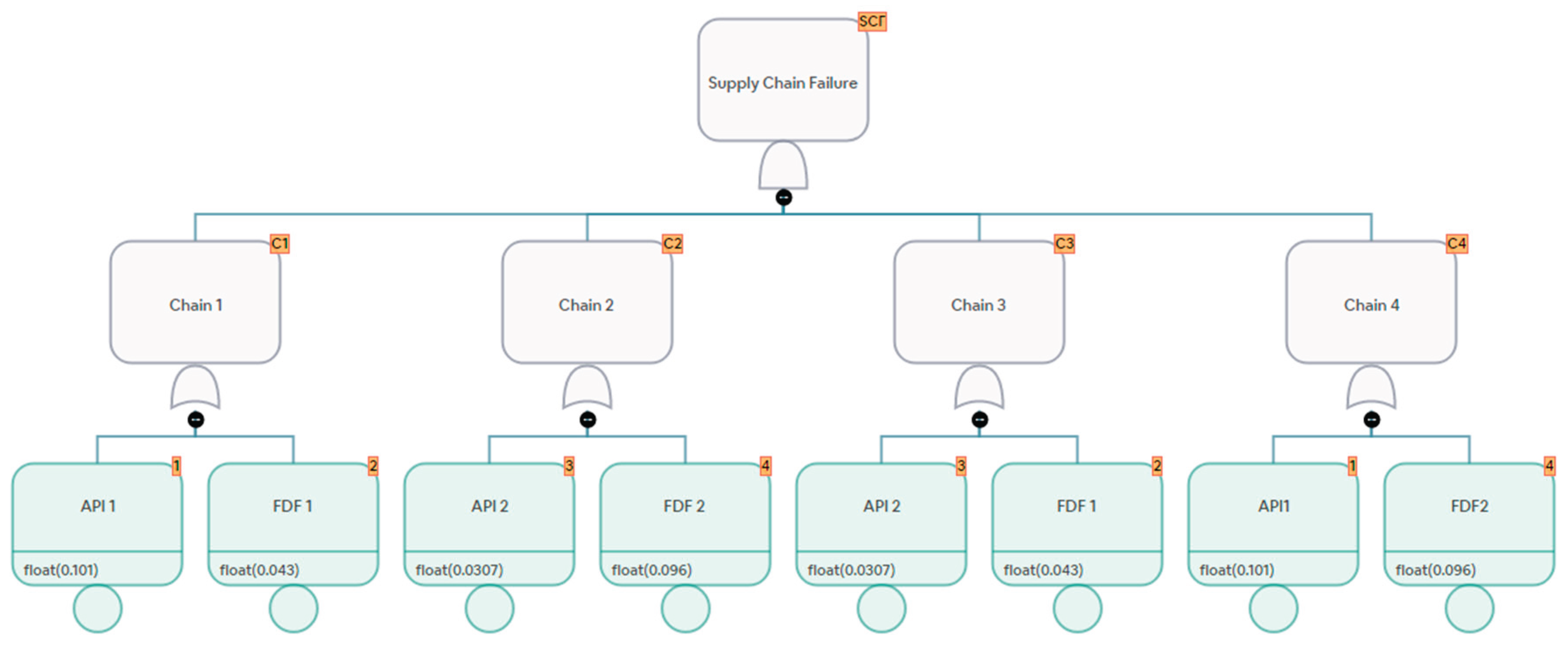

Figure 6 illustrates a generated fault tree, visualized in the open-source, collaborative PRA tool OpenPRA [

30]. SUPRA is part of the development effort within the OpenPRA umbrella to quantify supply chains using PRA best practices.

3.1. Data Structures

We stored the input data for this program in Excel sheets, which contain values corresponding to various drugs denoted by a unique drug ID. Each row of the sheet describes a single API and FDF chain. We organized the rows into the following columns relevant to fault tree construction, as shown in

Table 1. Columns A, B, C, and E give us the names of the drug supply chain tiers. Columns D, F, G, H, I, and J give the failure probability, flow, and maximum flow for the FDF and API facilities.

We placed no arbitrary limits on the size or number of the input sheets. In our testing, we have scaled the data from hundreds of thousands to millions of rows, each representing partial drug information. Therefore, efficiently reading and processing the input data is vital. To accomplish this, we used the Python library Pandas to quickly read the input Excel sheets and store the information in a Pandas Dataframe, an object provided by the library that allows the data to be queried and processed through the Pandas API [

29]. The code iterates over the rows stored in this data frame to construct fault trees, following the format specified by SCRAM, a command-line tool for various risk analysis methods, including fault tree quantification [

31]. A Python interface for SCRAM provides a Python class with methods for constructing fault trees and exporting the trees to an XML file compatible with the SCRAM command-line tool.

3.3. Fault Tree Creation Algorithm

Fundamentally, the algorithm for constructing a fault tree is as follows: begin by querying a list of all unique values found in the drug_id column of the input sheet, then iterate over these values, passing one at a time to a function tasked with constructing a single gate. For a given drug_id, this function using the SCRAM Python interface, creates the root gate of the tree. It then queries a list of all unique app_ids associated with the drug_id and iterates over each unique app_id. For each app_id, we create a gate, then query all rows associated with the drug_id and app_id to produce a list of API and FDF chains associated with the application. We create an OR gate and basic events corresponding to each chain’s API and FDF facilities using the failure probabilities specified in the input data. We then add the basic events to the chain gates, the chain gates to the app gates, and the app gates to the root gate. The gates are either an AND gate or an OR gate, depending on the drug’s number of supply chains.

A Python dictionary object, functioning as a hash map, is created for the generated events for quick access. Since memory for these events is allocated dynamically on the heap within an iterative loop, we use the API and FDF facilities’ total count to pre-allocate the map’s zeroed-out memory. In addition, to speed up instantiation, we utilized pthreads [

32] to create a separate map for the API and FDF. Here, we set up the dataframe for read-only memory access, making operations thread-safe and circumventing the added overhead of copying the large dataset. Finally, since the API and FDF IDs are unique, the two maps can be merged in constant time.

3.4. Modeling Backup Facilities

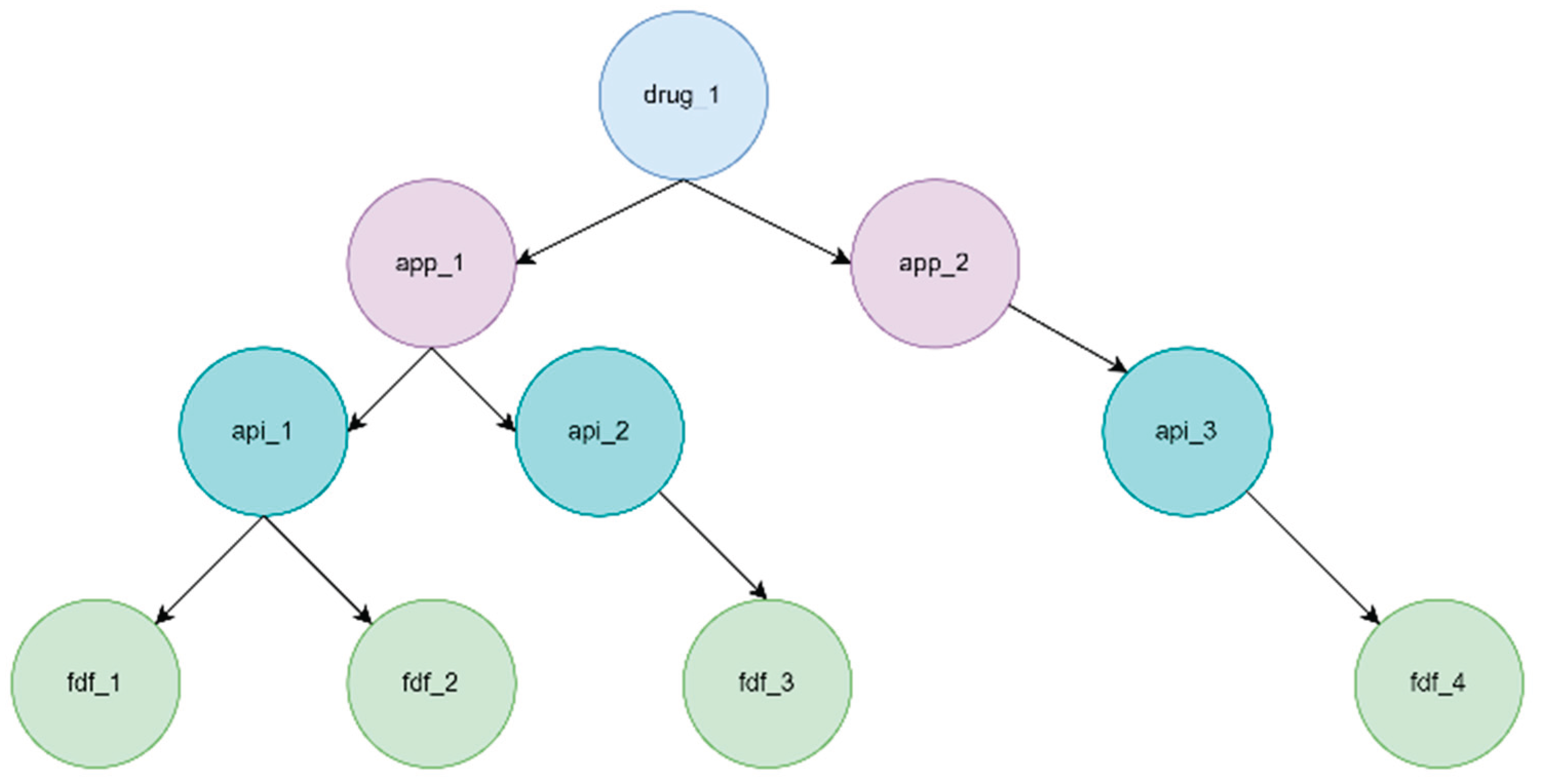

Some API or FDF facilities have a non-zero maximum flow and a zero flow; these are backup facilities. It is of value to know how much the drug failure probability is because of their inclusion. In

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, if we consider fdf_2 a backup facility, SUPRA determines whether the facility is a backup facility by checking its flow and maximum flow and quantifying the supply chain failure with and without the facility.

3.5. Modeling Shared Facilities

Multiple supply chains may share API and FDF facilities. Supply chains may sometimes have the same facility as an API and an FDF. For example, api_1 in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 can be a shared facility in two supply chains, in this case:

SCRAM treats objects with the same ID as one object. If a facility shared among multiple drug supply chains fails, then knowing the relative impact of its failure as compared to other facilities is important.

Currently, our dataset has facilities shared among chains within the same drug_id. If more than one drug supply chain shares a facility, we can update the terminology to reflect the shared facility among multiple drug applications.

3.7. Pseudocode

For every inactive drug (maximum units = 0, units =0 for api_id)

Drop the inactive drug.

If the user wants quantification without a backup facility (maximum units≠ 0, units = 0, for api_id or fdf_id)

Drop the backup facilities.

Else

Include them in quantification.

Calculate supply chain flow,

Sum up the flow column for fdf_id.

Define function, create gate,

For selected column,

Read number of rows,

If number of rows is 0,

Exit code.

Else if, number of rows is 1,

Create OR gate.

Else if, Else if, number of rows is more than 1,

Create an AND gate.

For every drug_id,

Call the function, create gate.

If an OR gate is created,

Set it equal to the app_id OR gate.

For every app_id,

Call the function, create gate.

Add api_id and fdf_id as basic events.

Using SCRAM,

Quantify the fault tree and,

Generate importance measures for every basic event.

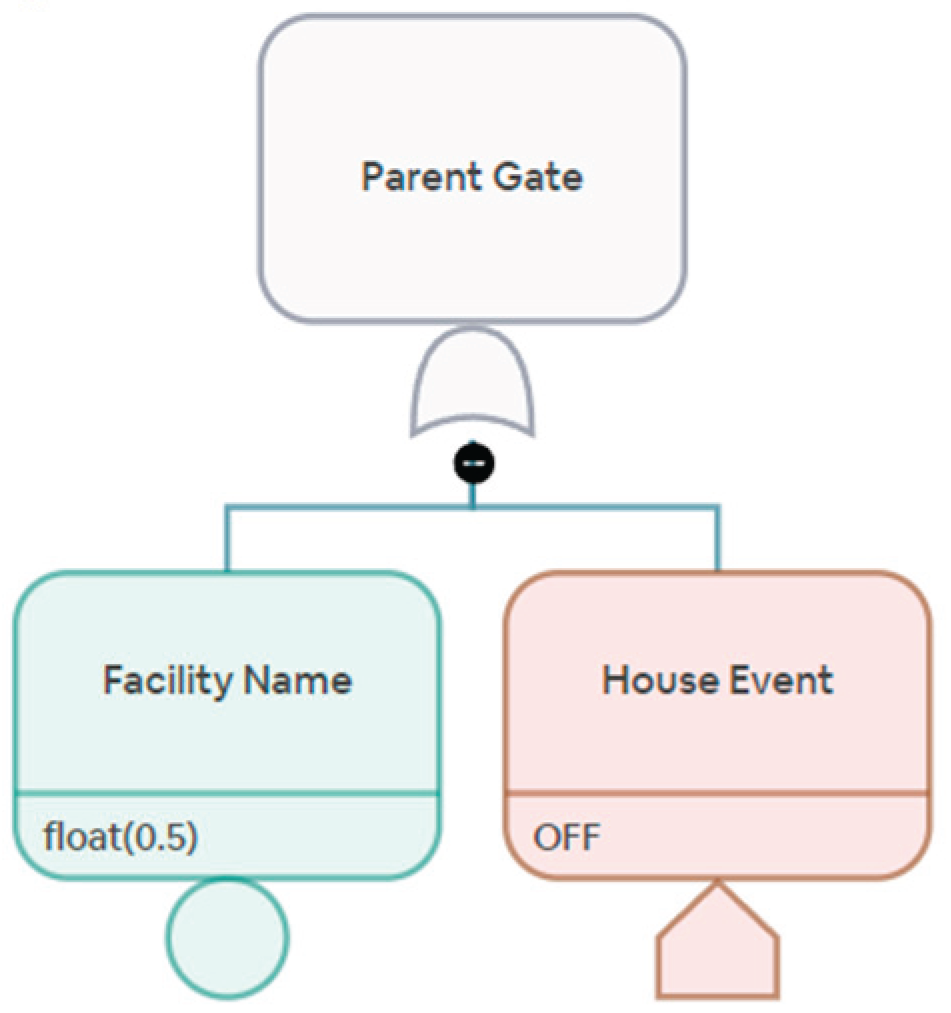

3.8. Single Child Corner Case

SCRAM requires each gate in the tree to have more than one input to be quantified. Still, many drugs in the input data share the facility for the FDF and API process. In these cases, we add a house event with perfect reliability and quantify the chain, as shown in

Figure 9.

4. Additional Steps for Supply Chain Shortage Risk Quantification Methodology

In this section, we present the additions to the

4.1. Calculating Importance Measures

Importance measures help us quantify one facility’s relative susceptibility to failure with respect to the others within a drug supply chain.

Table 2 gives a list of all the importance measures [

33]. Based on the importance measures, stakeholders can develop reliability improvement methods for vulnerable facilities.

We calculate the importance measures of API and FDF facilities using built-in SCRAM libraries. A well-designed supply chain will have equally balanced importance measures. Otherwise, a supply chain configuration may be optimal in production but not have a resilient production flow.

Facilities with a very low marginal importance measure could have their reliability requirements relaxed. Conversely, those with a high marginal importance measure are critical for supply chain reliability. More effort should be invested in improving their reliability or changing the structure of the supply chain. The improvement potential importance measure indicates the extent to which supply chain reliability improves when the failure probability of the facility i is reduced to zero. In a scenario where the supply chain has failed, the diagnostic importance measure can be used to prioritize maintenance, as it will focus on facilities that are most likely to have caused the failure.

The risk achievement worth importance measure is used to find the risk significance of facilities removed from the supply chain. If the importance measure is close to 1, then its improvement has a negligible effect on the supply chain. Risk reduction worth is complementary to the risk achievement worth.

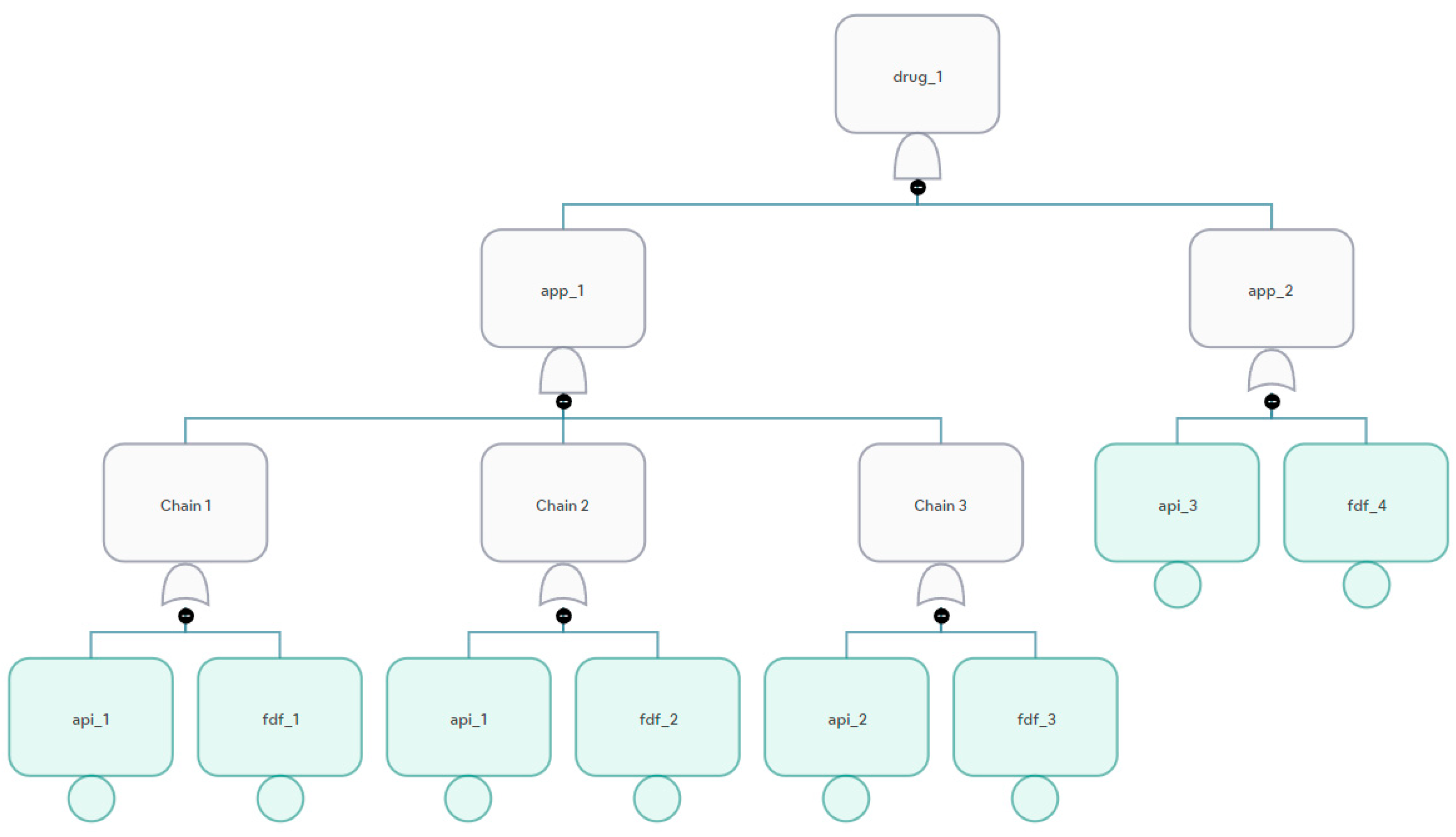

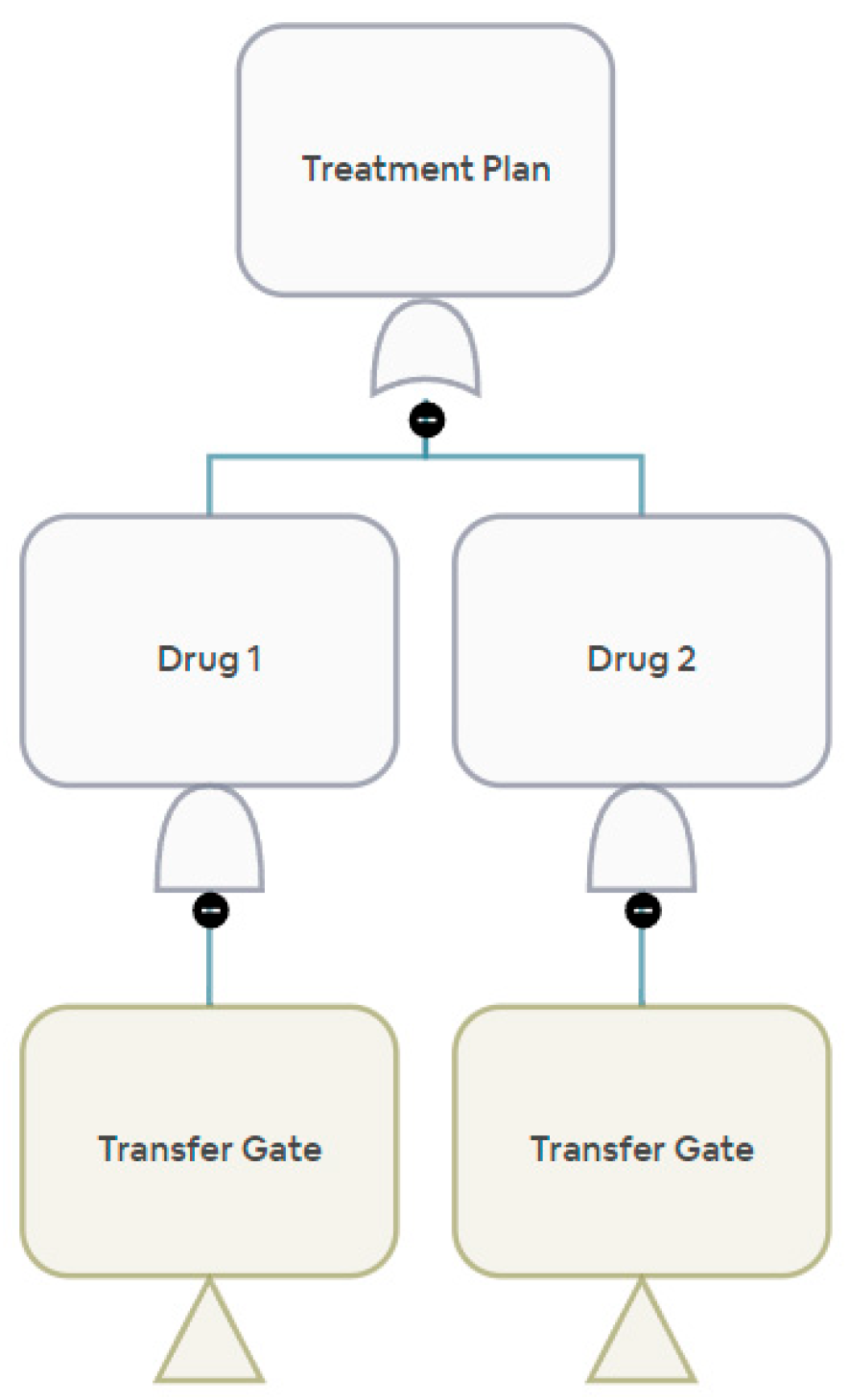

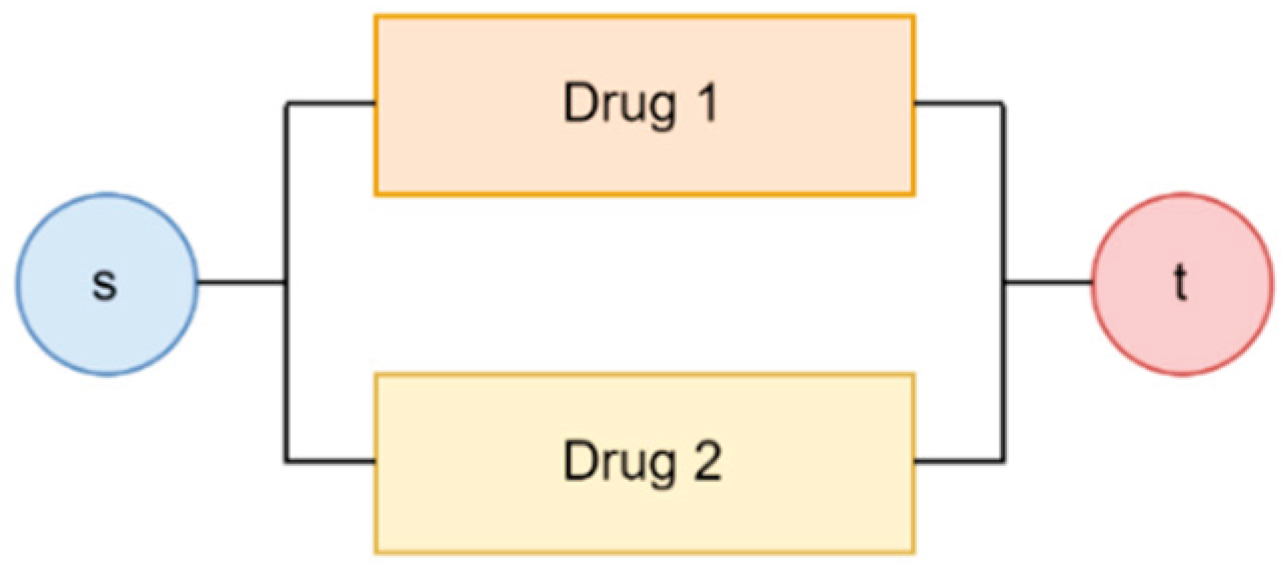

4.2. Guidelines for Decision Makers

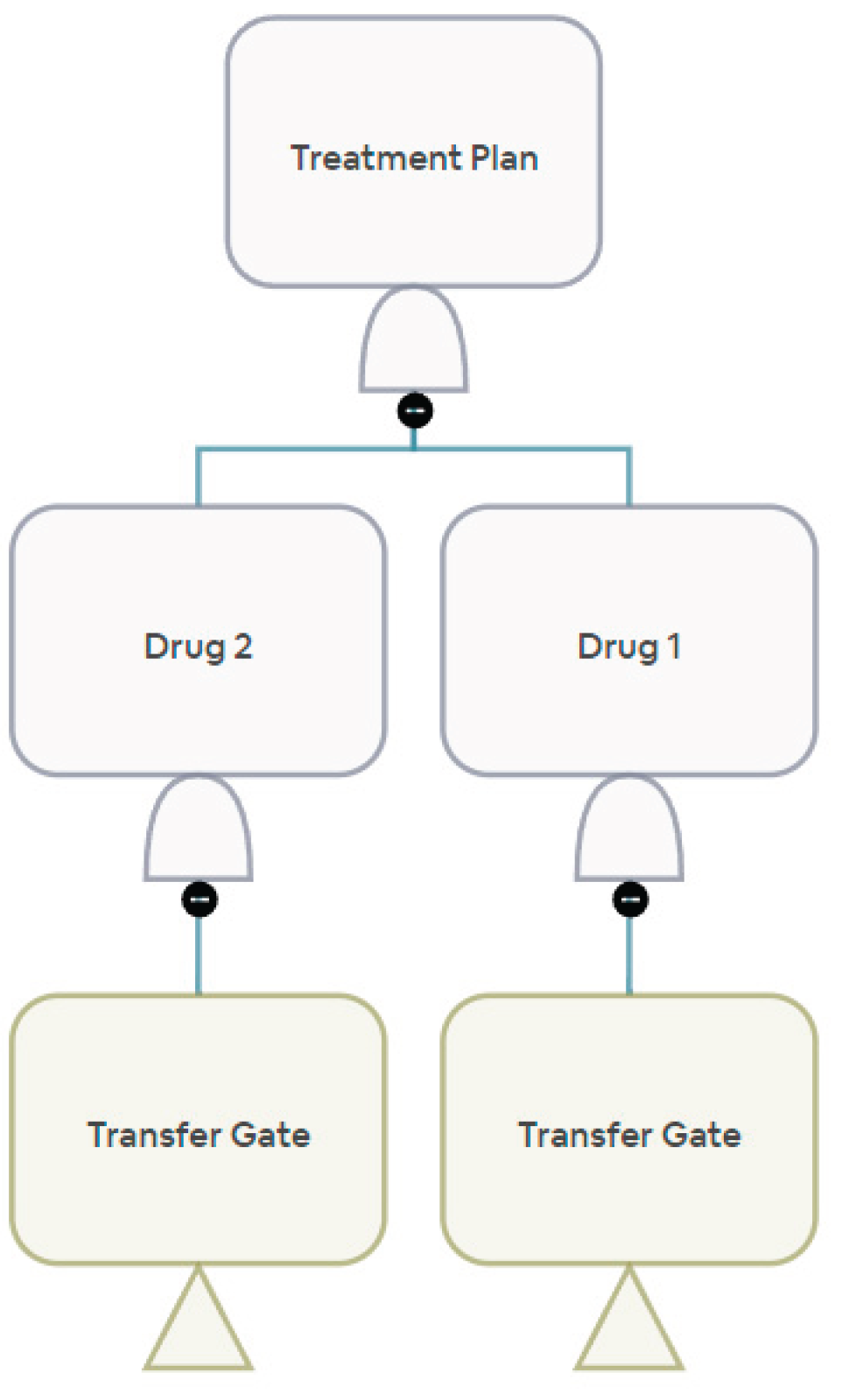

Our current analysis considers the supply chains of individual drugs for quantification. However, for stakeholders, such as federal regulators, an important layer to add to the current analysis is the supply risk of a drug treatment plan. A drug treatment plan may consist of combinations of requisite drugs. Sometimes, the plan may also consist of more than one acceptable drug. The stakeholders select an AND gate or an OR gate and ultimately construct the body of the drug treatment plan as a network graph.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show an example of a combination where we require more than one drug for treatment. Another example can be a treatment plan with more than one acceptable drug, shown in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

4.3. Mitigation Analysis

Some supply chains may fail with probabilities considered substantially high by decision-makers. For these supply chains, it is of interest to reduce the likelihood of failure by applying mitigation techniques. Reducing the facility failure probability may mean troubleshooting manufacturing issues or shipping logistics. Another mitigating method is to add one or more backup facilities.

We are working on implementing mitigation analysis, which consists of reducing the supply chain failure by employing either mitigation methods: reducing the failure probabilities of the facilities or adding backup facilities. This mitigation algorithm is a part of our future work.

Figure 1.

Overview of SUPRA Methodology.

Figure 1.

Overview of SUPRA Methodology.

Figure 2.

Representation of Supply chains as Network Graphs.

Figure 2.

Representation of Supply chains as Network Graphs.

Figure 3.

Example of Network Graph Representation of Supply chains.

Figure 3.

Example of Network Graph Representation of Supply chains.

Figure 4.

Example of Fault Tree Representation of Supply Chains.

Figure 4.

Example of Fault Tree Representation of Supply Chains.

Figure 5.

Pharmaceutical Drug Supply Chain.

Figure 5.

Pharmaceutical Drug Supply Chain.

Figure 6.

Drug Supply Chain Fault Tree, generated in OpenPRA.

Figure 6.

Drug Supply Chain Fault Tree, generated in OpenPRA.

Figure 7.

Modeling Backup and Shared Facilities.

Figure 7.

Modeling Backup and Shared Facilities.

Figure 8.

Fault Tree for Modeling Backup and Shared Facilities.

Figure 8.

Fault Tree for Modeling Backup and Shared Facilities.

Figure 9.

Single Child Corner Case.

Figure 9.

Single Child Corner Case.

Figure 10.

Example of a Treatment Plan with More Than One Requisite Drug

Figure 10.

Example of a Treatment Plan with More Than One Requisite Drug

Figure 11.

Fault Tree for Treatment Plan with More Than One Necessary Drug

Figure 11.

Fault Tree for Treatment Plan with More Than One Necessary Drug

Figure 12.

Drug Sourcing Plan with Allowed Substitutions

Figure 12.

Drug Sourcing Plan with Allowed Substitutions

Figure 13.

Fault Tree for Treatment Plan with More Than One Acceptable Drug

Figure 13.

Fault Tree for Treatment Plan with More Than One Acceptable Drug

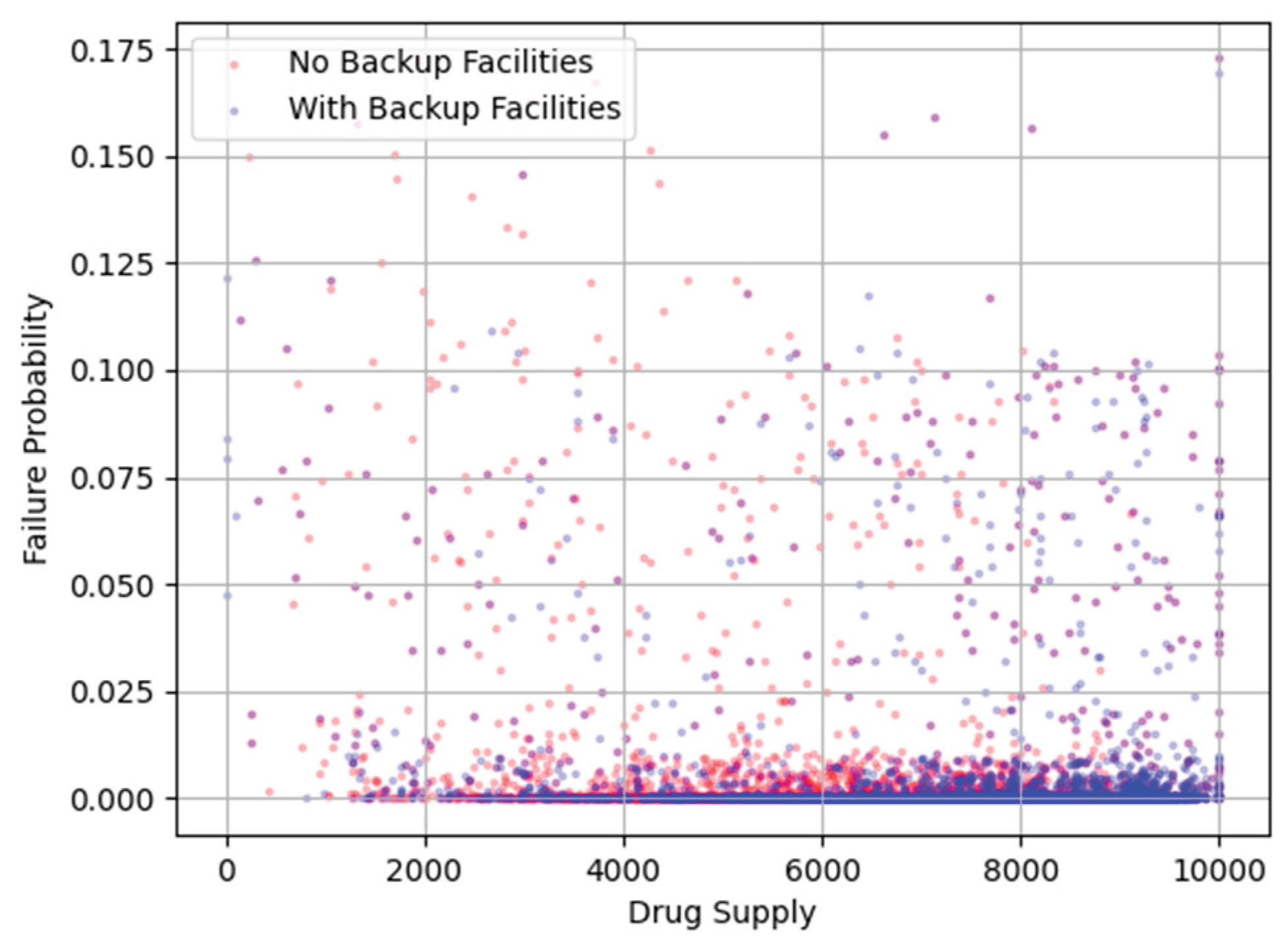

Figure 14.

Drug Supply Failure Probabilities with and without Backup.

Figure 14.

Drug Supply Failure Probabilities with and without Backup.

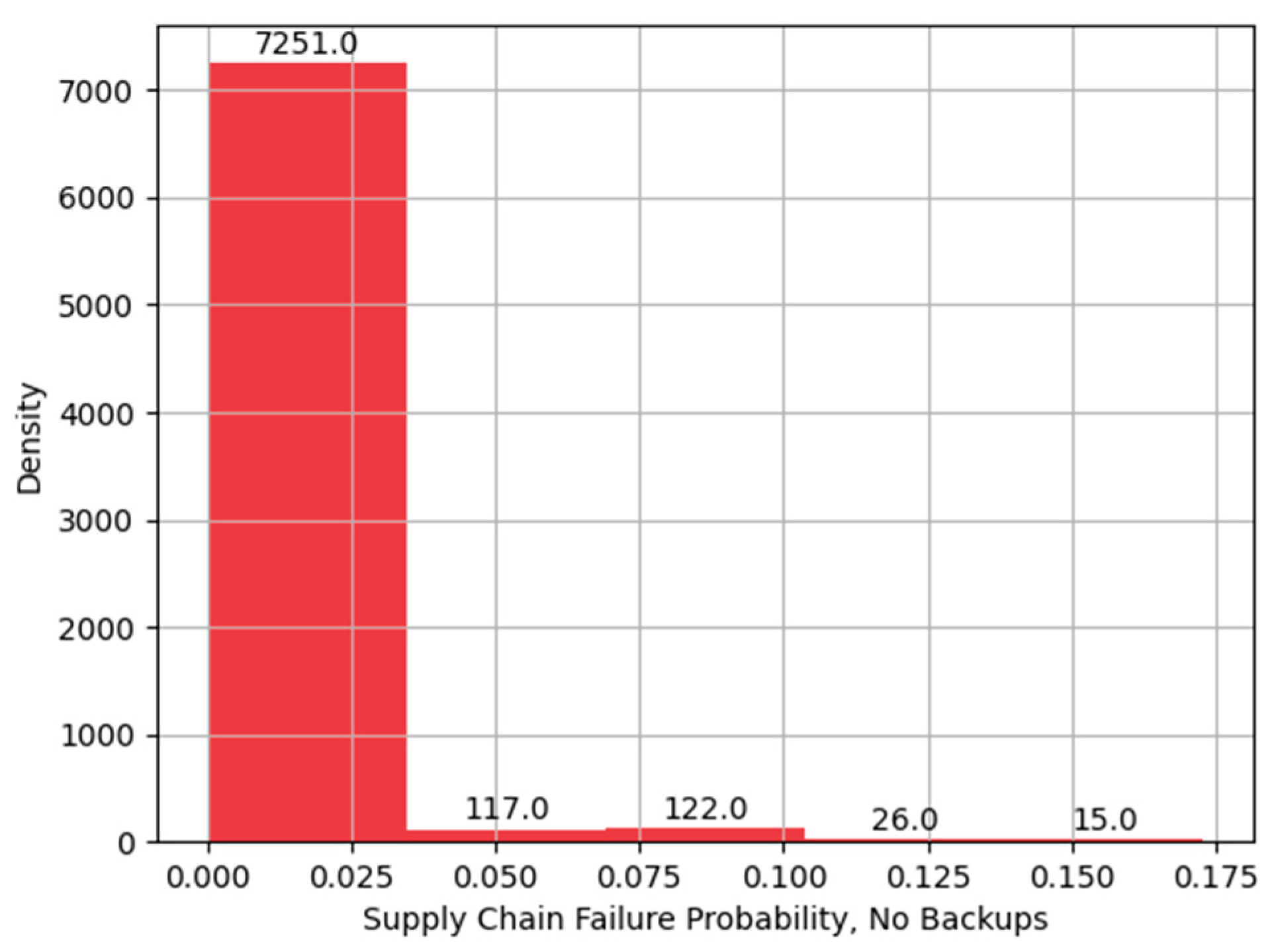

Figure 15.

Histogram of Supply Chain Failure Probability, without Backups.

Figure 15.

Histogram of Supply Chain Failure Probability, without Backups.

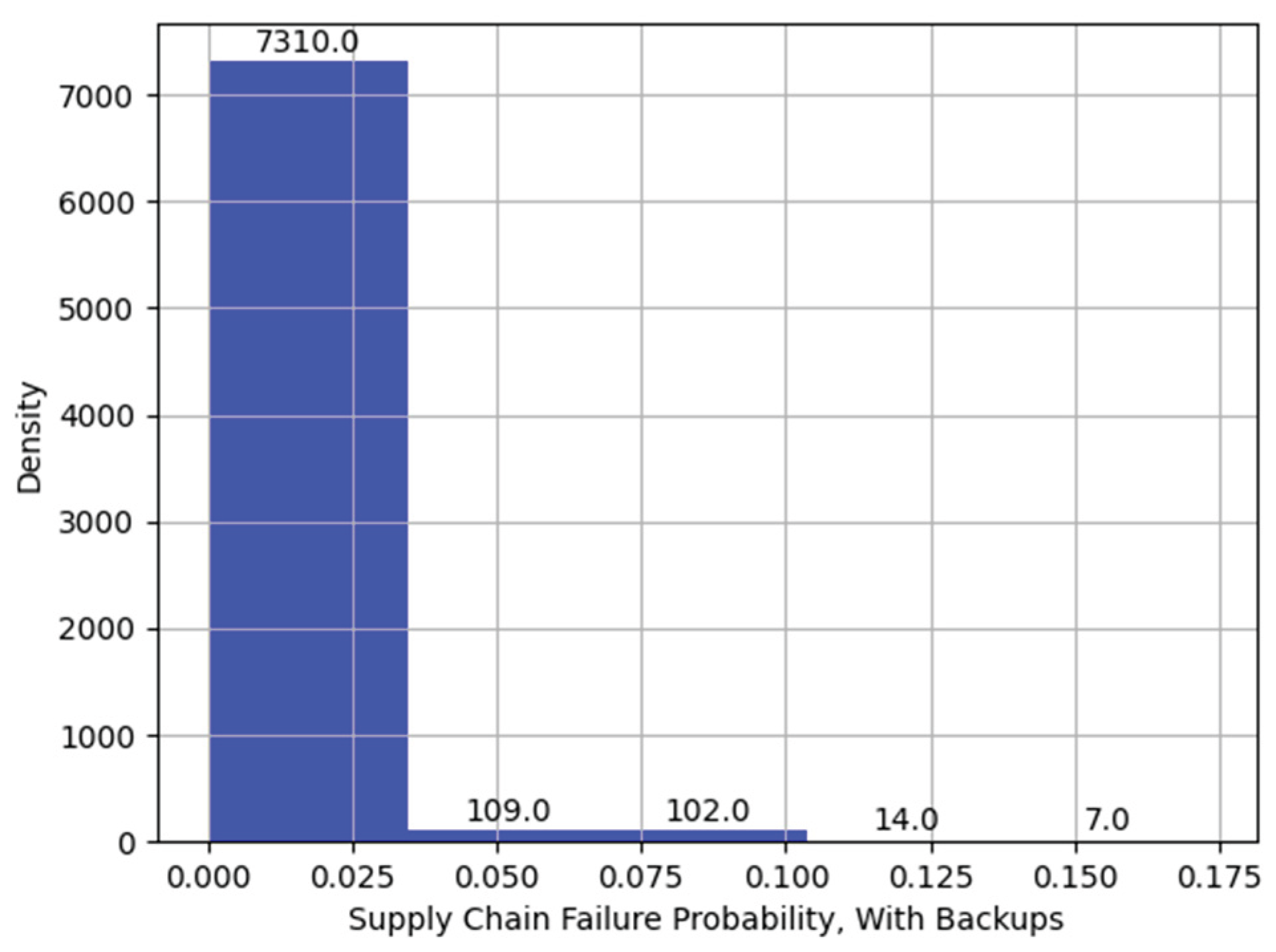

Figure 16.

Histogram of Supply Chain Failure, with Backups.

Figure 16.

Histogram of Supply Chain Failure, with Backups.

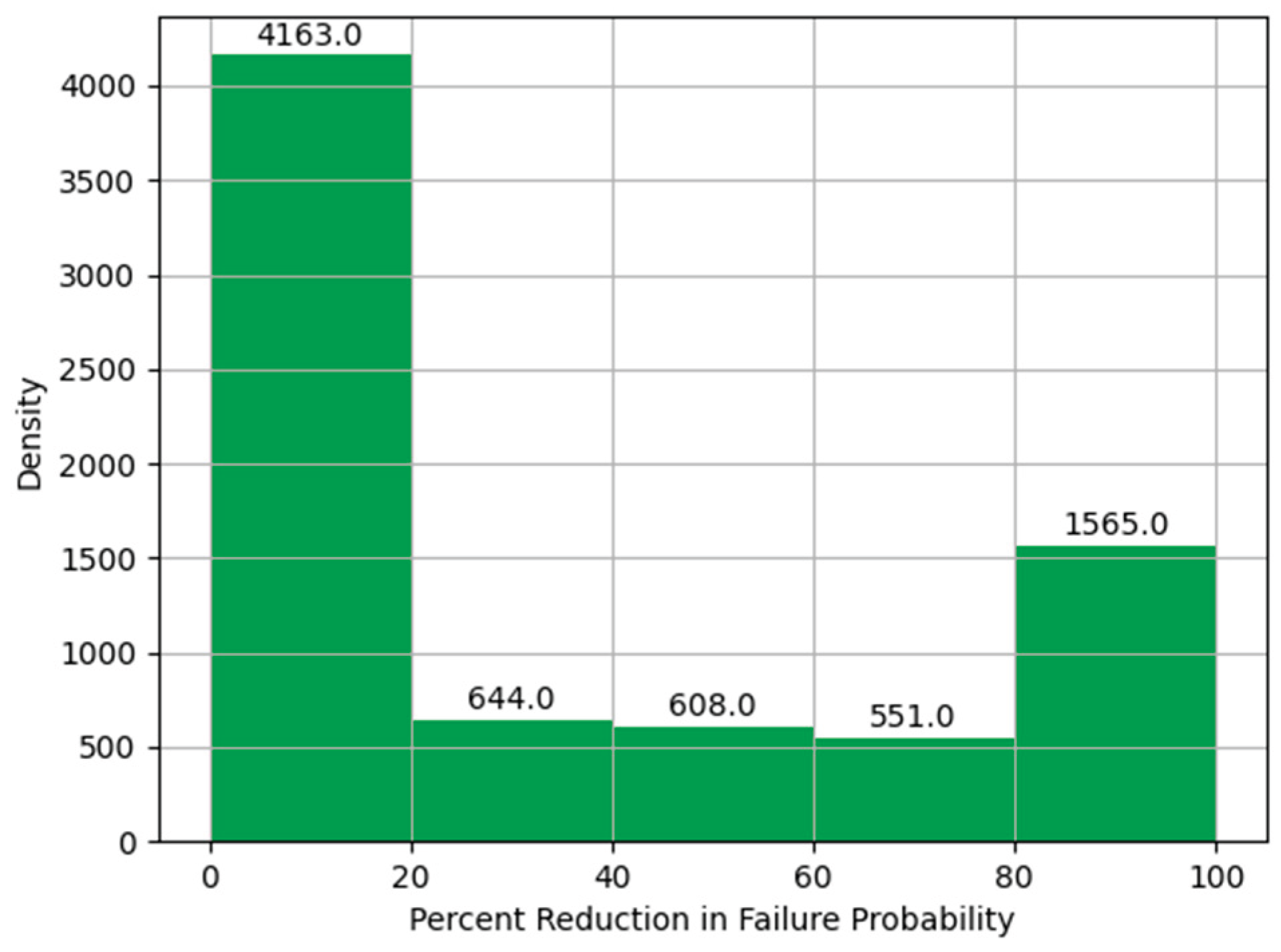

Figure 17.

Histogram of Percent Reduction in Failure Probability.

Figure 17.

Histogram of Percent Reduction in Failure Probability.

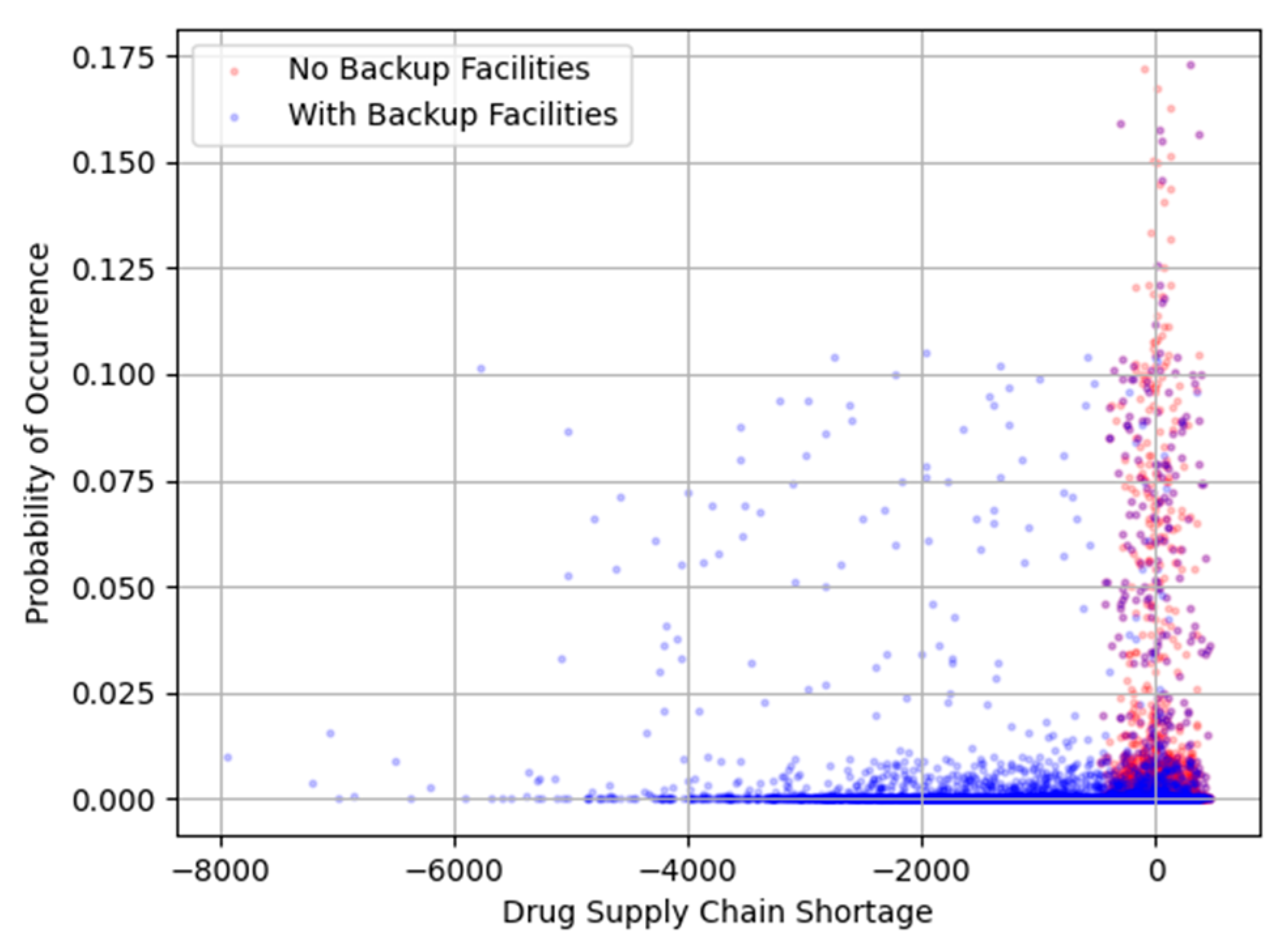

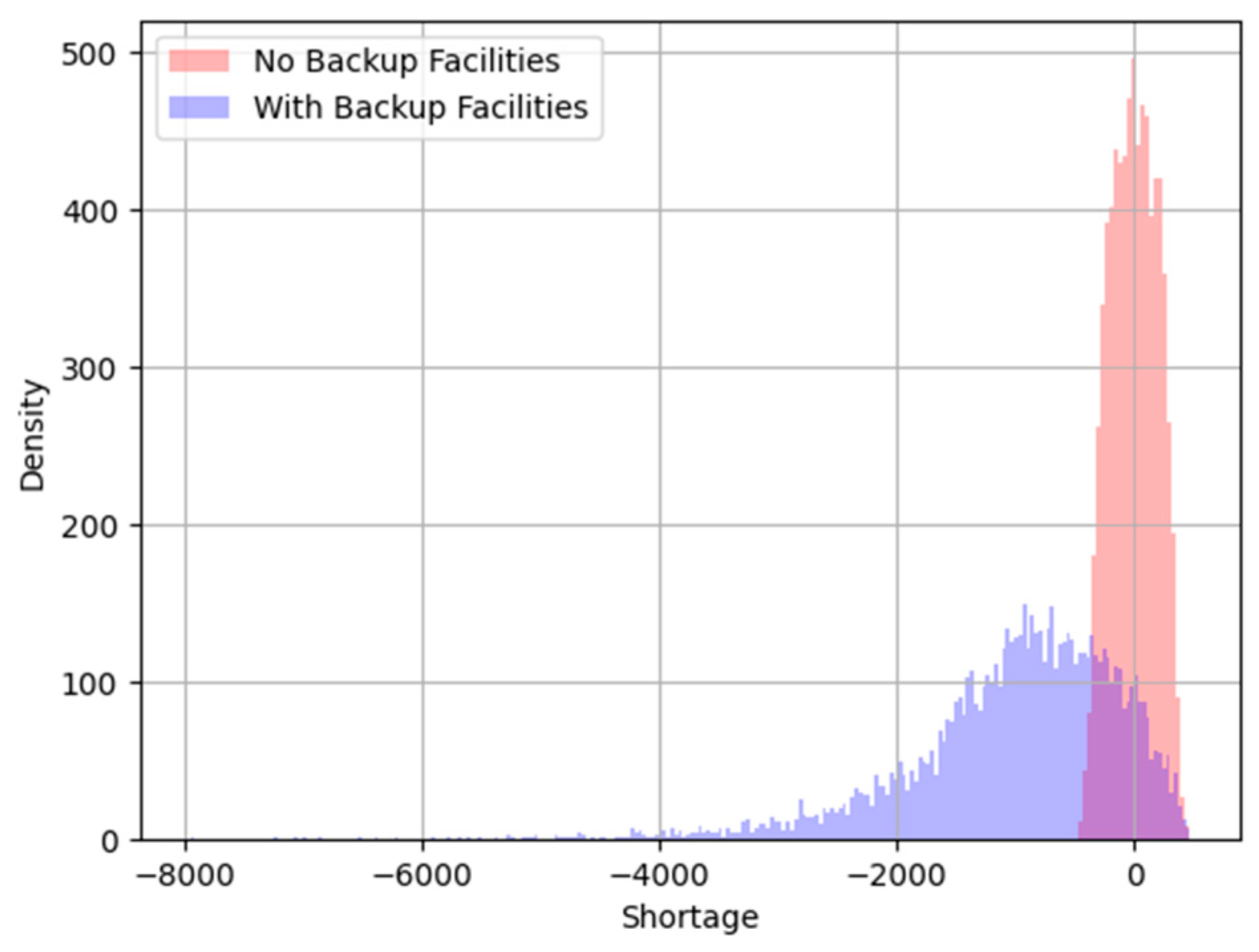

Figure 18.

Shortage Risk Profile.

Figure 18.

Shortage Risk Profile.

Figure 19.

Histogram of Supply Chain Shortage.

Figure 19.

Histogram of Supply Chain Shortage.

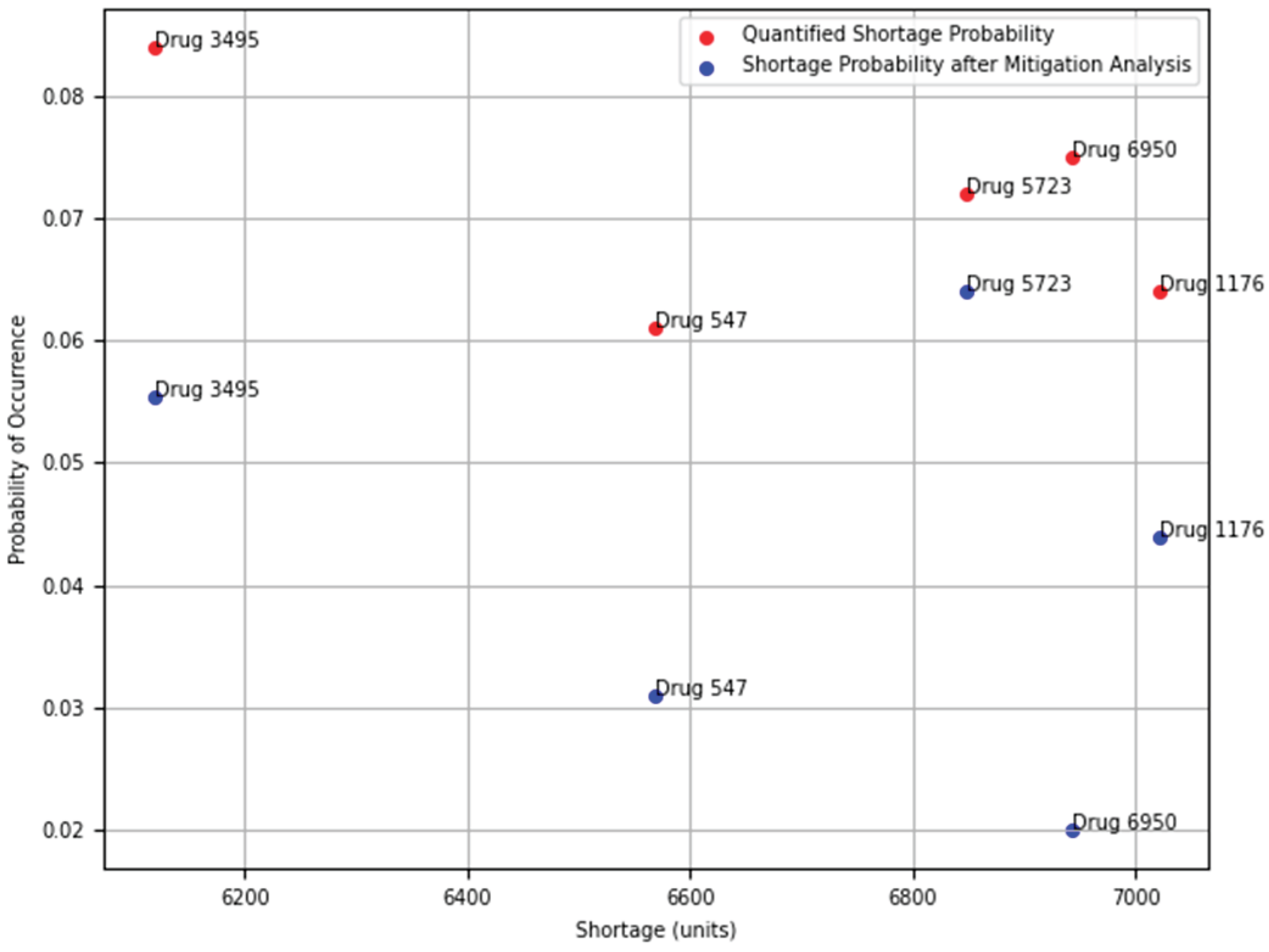

Figure 19.

Application of Mitigation Analysis to Shortage Probability of Drug Supply Chains.

Figure 19.

Application of Mitigation Analysis to Shortage Probability of Drug Supply Chains.

Table 1.

Input Data for SUPRA.

Table 1.

Input Data for SUPRA.

| Column |

Data Label |

| A |

|

| B |

|

| C |

|

| D |

|

| E |

|

| F |

|

| G |

|

| H |

|

| I |

|

| J |

|

Table 2.

Importance Measures.

Table 2.

Importance Measures.

| Importance Measure |

Definition |

| The conditional importance measure (CIF) of a facility i, is based on the conditional probability of supply chain failure given that the facility i had already failed. |

|

| The marginal or Birnbaum’s importance measure (MIF) quantifies the rate of change of the supply chain reliability with respect to changes to the reliability of a single facility. |

|

| The diagnostic or Fussell-Vesely importance measure (DIF) is the probability that at least one minimal cut-set that contains a specific facility, results in system failure. |

|

| The risk achievement worth (RAW) importance measure quantifies the relative increase in the supply chain failure probability given that facility i is in a failed state. |

|

| The risk reduction worth (RRW) importance measure quantifies the relative reduction in the supply chain failure probability given facility i is made perfectly reliable. |

|

Table 3.

Output Data from SUPRA for Drug Supply Chain Flow and Failure Probability.

Table 3.

Output Data from SUPRA for Drug Supply Chain Flow and Failure Probability.

| Drug ID |

|

| Failure Probability |

|

| Warnings |

none |

| Throughput/Flow |

8003.23 |

| Demand |

7959 |

| Shortage/Surplus |

-44 |

Table 4.

Output Data from SUPRA for Drug Supply Chain Importance Measures.

Table 4.

Output Data from SUPRA for Drug Supply Chain Importance Measures.

| Facility ID |

|

| Occurrence |

4 |

| Failure Probability |

|

| MIF |

|

| CIF |

|

| DIF |

|

| RRW |

|

| RAW |

|

Table 5.

Summary of Statistics from SUPRA Results.

Table 5.

Summary of Statistics from SUPRA Results.

| Failure Probability |

5th Percentile |

Median |

95th Percentile |

| Without Backup |

5.02e-8 |

3.36e-5 |

|

| With Backup |

2.48e-8 |

1.95e-5 |

|

Table 6.

Importance Measures for Drug Supply Chain Number 1213.

Table 6.

Importance Measures for Drug Supply Chain Number 1213.

| Name |

MIF |

CIF |

DIF |

RAW |

RRW |

| APP1-API1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| APP1-FDF2 |

|

|

|

|

|

| APP1-FDF3 |

|

|

|

|

|

| APP1-API2 |

|

|

|

|

|

| APP1-FDF1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| APP2-API1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| APP2-FDF1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| APP2-FDF2 |

|

|

|

|

|