1. Introduction

Critical limb ischemia (CLI), a severe manifestation of peripheral arterial disease, continues to present a major clinical challenge due to the scarcity of effective treatment options for patients who are not candidates for surgical or endovascular revascularization. CLI is the most severe form of atherosclerosis obliterans (ASO), which is a medical condition characterized by the stenosis or occlusion of the arteries in the lower extremities due to the accumulation of atherosclerotic plaques, thereby reducing blood supply to the tissues [

1]. It is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, particularly in the presence of comorbidities, such as diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and kidney disease [

2]. In critical limb ischemia, even with optimal treatment, amputation rates can reach up to 30% per year, while mortality rates may rise to 25% per year [

3]. Despite advances in treatment, improving long-term prognosis remains challenging, and non-invasive treatment options are limited.

We are currently conducting a prospective clinical trial under the Advanced Medical Care B program in Japan (jRCTb030210146), which investigates the efficacy and safety of intramuscular administration of autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) in patients with CLI. This program, endorsed by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, allows for the clinical use of unapproved regenerative therapies while collecting safety and efficacy data, thereby bridging experimental medicine and future insurance-covered applications. Our therapy is considered safer because it does not use fetal bovine serum and is less invasive, requiring only a small amount of bone marrow (BM) and eliminating the need for prolonged general anesthesia [

4]. The Japanese Circulation Society/Japanese Society for Vascular Surgery 2022 Guideline on the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease states that, at the time of publication, no MSC-based therapy had been developed for advanced medical treatment or clinical trial stages in regenerative medicine [

2]. Notably, in April 2022, concurrent with the release of these guidelines, we initiated our regenerative medicine study.

In that study, differences in therapeutic efficacy were observed even when cells were cultured using identical techniques [

5,

6]. Mikami et al. showed that autologous BM-MSC implantation induced angiogenesis in a rabbit ischemic model [

7]. They also observed that only a minor fraction of the implanted MSCs transformed into endothelial cells. In our previous experiment, we could not demonstrate that the implanted MSCs differentiated into endothelial cells within the muscle; however, there remains a possibility that the implanted MSCs secreted soluble factors promoting angiogenesis in situ [

5]. MSCs are known to secrete angiogenic factors via paracrine action and migrate to sites of inflammatory ischemia through chemotaxis. These factors, together with other molecules secreted by MSCs, can be delivered to target tissues through extracellular vesicles (EVs), nanometer-scale membrane-bound structures that facilitate intercellular communication [

8]. To elucidate the mechanism underlying the observed differences in therapeutic efficacy in our clinical trial, we focused on microRNAs (miRNAs) present in EVs in the culture supernatant of BM-MSCs, which are believed to influence the angiogenic therapeutic effect. We conducted a basic study using commercially available normal human BM-MSCs.

Among miRNAs, those regulating pro-angiogenesis, known as angiomiRs, promote endothelial cell growth, survival, and migration and the formation of capillary-like structures [

9,

10]. Based on our literature review and other considerations, we selected five angiomiRs—miR-9, miR-105, miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210—for examination in this study [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Additionally, although miR-296 was also considered as a candidate due to its angiogenic role via the VEGF pathway, it was excluded because its function overlaps with miR-126.

To test our hypothesis, we established an in vitro experimental model in which selected angiogenesis-related miRNAs were analyzed for their individual and combined effects on endothelial cell tube formation. This study provides mechanistic insights that support the therapeutic rationale for our ongoing clinical application of MSCs in patients with CLI, and also suggests the potential of nucleic acid-based therapeutics targeting angiogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells

The human-derived cells used in this study were obtained from ethically approved sources (Lonza and PromoCell), and their use complied with the supplier’s regulations and Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Cells and Cell Culture

Normal human BM-MSCs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; C2517AS, Lonza, USA) were utilized in this study. BM-MSCs were cultured in MesenPRO RS Medium (#12746-012; Gibco, USA) at 37.0 ℃ in a humidified atmosphere with 5.0% CO2. HUVECs were cultured in Endothelial Cell Growth Medium-2 BulletKit (#CC-3162, Lonza, USA) under the same conditions. Confluent cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (−), detached using Accutase, and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 3 min at room temperature. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed, and cell pellets were resuspended in MesenPRO RS Medium for subsequent experiments.

The BM-MSCs employed in this study were obtained from the following donors: 25-year-old male (PT-2501, Lot: 19TL281098, Lonza, USA), 21-year-old male (PT-2501, Lot: 4F0218, Lonza, USA), 23-year-old female (C-12974, Lot: 21TL046615, PromoCell, USA), 72-year-old female (C-12974, Lot: 471Z022, PromoCell, Germany), 68-year-old male (C-12974, Lot: 467Z023.5, PromoCell, USA), and 63-year-old male (C-12974, Lot: 465Z016, PromoCell, Germany).

2.3. Cell Culture for EV Collection

The resuspended cell pellets were seeded into sterile 150-mm culture dishes at a density of 6.0 × 105 cells/dish, with viability confirmed via trypan blue staining. After 24 h, cells were washed with PBS (−), and the medium was replaced with 20 mL/dish of CTS StemPro MSC SFM Medium (#A1033201; Gibco, USA). The cells were incubated for 48 h to facilitate EV secretion.

2.4. EV Collection via Ultracentrifugation

Culture supernatants were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4 ℃. The supernatants were filtered through a 0.22-μm membrane filter (SCGPS02RE, Millipore, Germany) and transferred to an ultracentrifuge tubes. Ultracentrifugation was performed at 35,000 rpm for 70 min at 4 ℃ using Optima XE-90 Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, USA). The resulting precipitate was resuspended in PBS (−) and weighed.

2.5. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

The size and concentration of EVs were determined using a NanoSight LM10 system (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Amesbury, UK) equipped with a 405-nm blue laser and NanoSight NTA software v3.44. The EVs were illuminated by a laser, and the Brownian motion of particles was recorded in 90-s videos. Particle size was calculated using the Stokes–Einstein equation via the NTA 2.0 software. EV samples were diluted with 0.22-μm filtered PBS (−) to achieve a final particle concentration of 1 × 108 to 2.5 × 109 particles/mL.

2.6. ExoScreen Assay

The ExoScreen assay was performed as previously described [

16] to detect exosomes. Ten microlitres of culture supernatant or EV samples were added to 96-well half-area white plates (6002290; PerkinElmer, USA), followed by 15 μL of a mixture of anti-human CD63 antibody solid-phase acceptor beads and biotinylated anti-human CD63 antibody. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 ℃ for 1 h in the dark. Subsequently, 25 µL of AlphaScreen streptavidin-coated donor beads were added without washing, and the plate was incubated in the dark for another 30 min at room temperature. The plate was then read on the EnSpire Alpha 2300 Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 680 nm and emission detection at 615 nm. Background signals from 0.22-μm filtered PBS (–) were subtracted from the readings.

2.7. RNA Purification

Cells cultured in 100-mm dishes were washed with PBS (–) and lysed using QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Total RNA, including miRNAs, was extracted with the miRNeasy Mini Kit (217004; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Syn-cel-miR-39-3p miScript miRNA Mimic 219600 (MIMAT0000010; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used as a reference miRNA for correction. RNA concentrations were quantified using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

2.8. Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

miRNA reverse transcription was performed using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (4366597; Applied Biosystems, USA). Amplification was conducted with the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix without AmpErase UNG (4324018; Applied Biosystems), using miRNA-specific primers from the TaqMan MicroRNA Assay (4427975; Applied Biosystems). Endogenous controls included miR-16 and cel-miR-39. Data were analysed using the 2-ΔΔCT method on the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The TaqMan assay IDs for the target miRNAs were: miR-9: 000583, miR-105: 002167, miR-126: 002228, miR-135b: 002261, miR-210: 000512, miR-16: 000391, and cel-miR-39: 000200.

2.9. Tube Formation Assay Using co-Culture of BM-MSCs and HUVECs

BM-MSCs (PT-2501, Lot: 19TL281098, Lonza, USA) were seeded at densities of 7.0 × 10

5 and 28.0 × 10

5 cells and embedded in Matrigel (Corning Matrigel basement membrane matrix Reduced, 354230; Corning, USA) in 24-well plates. After incubation at 37 ℃ with 5% CO

2 for 30–60 min, HUVECs (1.5 × 10

4 cells/well) were seeded onto the Matrigel beds. Angiogenesis was assessed morphologically after 20–24 h and further analysed using Calcein AM Fluorescent staining (Calcein AM Fluorescent dye, 354216, Corning, USA). Images were captured with a fluorescence microscope and processed with the ImageJ Angiogenesis Analyzer software [

17,

18].

2.10. miRNA Transfection into HUVECs

HUVECs (2.5 × 104 cells/well) were seeded into 24-well plates and incubated at 37 ℃ with 5.0% CO2 for 24 h. Transfection was performed using MimicRNA (Invitrogen, USA) and INTERFERin transfection reagent (101000028; Polyplus, France) following the manufacturer’s protocol. MimicRNA sequences included miR-126-3p: UCGUACCGUGAGUAAUAAUGCG (MC12841, Ambion, USA), miR-135b-5p: UAUGGCUUUUCAUUCCUAUGUGA (MC13044, Ambion), miR-210-3p: CUGUGCGUGUGACAGCGGCUGA (MC10516, Ambion), and a non-targeting negative control (NC) miRNA mimic (mirVana™ miRNA Mimic Negative Control #1, 4464058, Ambion), which contains a scrambled sequence that does not match any known human miRNA or mRNA sequences. The exact sequence of the NC mimic is proprietary and not publicly disclosed. After 48 h of incubation at 37 ℃ with 5.0% CO2, RT-qPCR was performed to confirm miRNA expression (as previously described in the Methods).

2.11. Tube Formation Assay with mimicRNA-transfected HUVECs

Transfected HUVECs were seeded at 1.6 × 105 cells/well into 6-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 ℃ in 5.0% CO2. MimicRNAs and transfection reagents were prepared as per the manufacturer’s protocol and added to the cells. Following transfection, the cells were incubated at 37 ℃ in 5.0% CO2 for 48 h. The transfected mimicRNAs included miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210, along with combinations of miR-126 + miR-135b, miR-126 + miR-210, miR-135b + miR-210, and miR-126 + miR-135b + miR-210. Matrigel (300 μL/well) was added to 24-well plates and incubated at 37 ℃ in 5.0% CO2 for 30 min to 1 h. Transfected HUVECs (3.0 × 104 cells/well) were seeded on Matrigel beds. Angiogenesis was assessed morphologically after 20–24 h and analysed as previously described in the Methods.

2.12. Evaluation of Angiogenic Protein Expression in Tube Formation Assay by Mimic RNA Transfection into HUVECs

The supernatant of the cultured 6 mm cell culture dish was removed, washed with PBS(-), and the PBS(-) was removed again. M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (78501, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with 1/100 of a protease inhibitor was added, and the cells were scraped off using a cell scraper and collected in a microtube. The cells were gently stirred at room temperature for 10 minutes, centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4 ℃, and the supernatant was collected. Protein was collected according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Protein was quantified using Qubit Assays (Q33211, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The expression levels of 55 angiogenesis-related proteins were evaluated using a membrane-type sandwich immunoassay (Proteome Profiler Human Angiogenesis Array Kit, R&D systems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The total protein amount of each sample was 100-µg. Proteins spotted on the membrane were visualized using a bioluminescence detector (Fusion Solo S, Vilber, France) with a 30-seconds exposure. Analysis of membrane spots was performed using ImageJ software.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined using a one-way analysis of variance in BellCurve for Excel (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd.). Multiple comparisons were performed using the Tukey post-hoc test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Confirmation of miRNA Expression in BM-MSC and BM-MSC-Derived EVs

3.1.1. Characterization of BM-MSC-Derived EVs

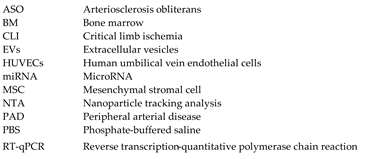

The physical and biochemical characteristics of BM-MSC-derived EVs were evaluated using a NanoSight LM10 system equipped with a 405-nm blue laser and NanoSight NTA software v3.44. NTA to determine particle size and distribution. NTA revealed a predominant particle size peak at approximately 100 nm (

Figure 1a). The EV yield was quantified at 2.0 × 10

3 to 3.0 × 10

3 particles per cell across passages (

Figure 1b). ExoScreen analysis confirmed the presence of BM-MSC EV surface marker, CD63, indicating successful EV recovery (

Figure 1c). These findings indicate that the quality of the BM-MSC-derived EVs aligns with the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles 2023 (MISEV2023) standards established by the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles.

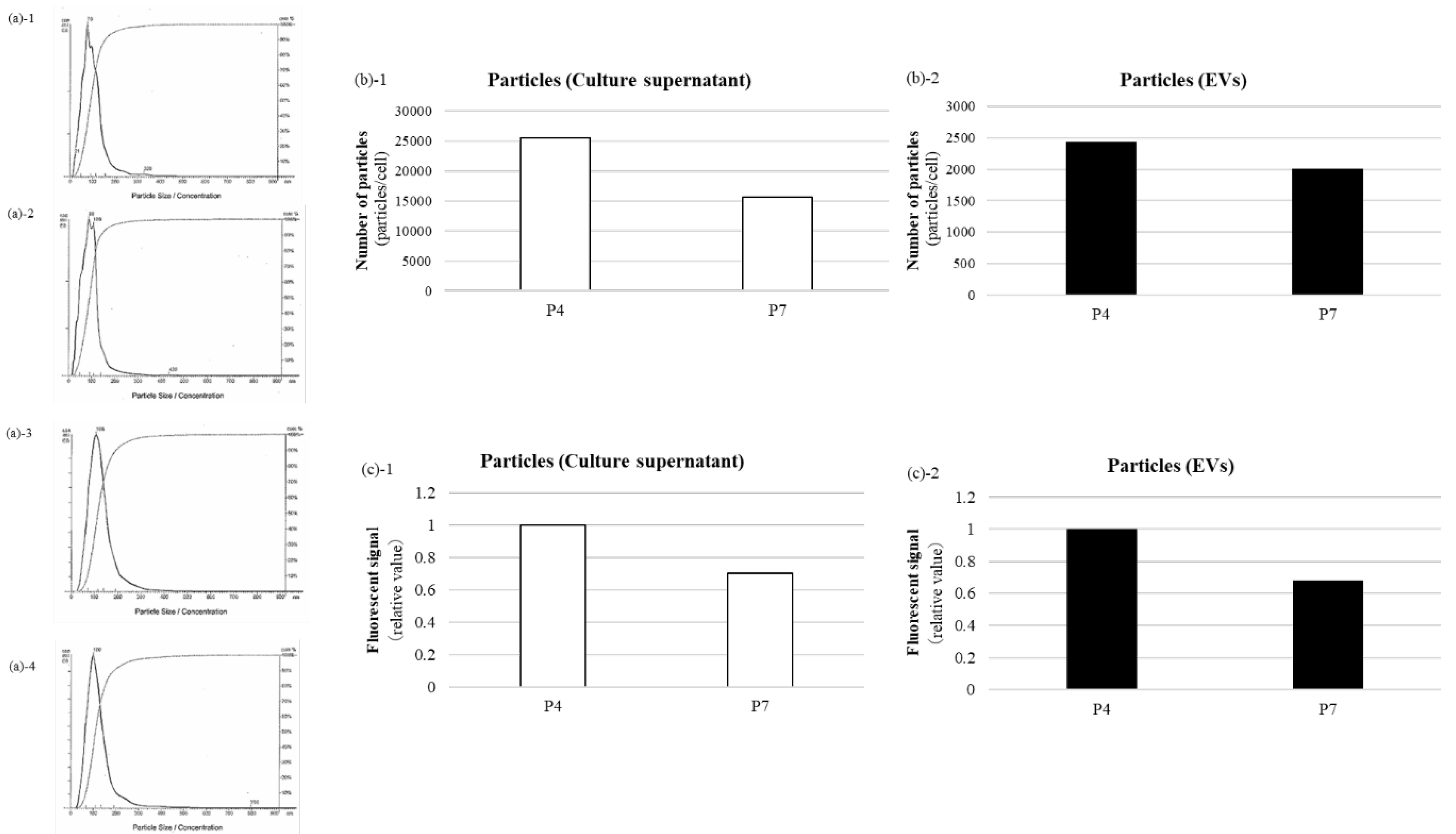

3.1.2. miRNA Expression Analysis in BM-MSC and BM-MSC-Derived EVs Across Passages

We examined the expression of five angiomiRs—miR-9, miR-105, miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210—associated with cellular senescence [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. BM-MSCs were cultured to passages 4 (P4) and 7 (P7). miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210 were detected in both BM-MSCs and EVs, whereas miR-9 and miR-105 were expressed exclusively in BM-MSCs and were not detected in EVs (

Figure 2). Based on these results, miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210 were selected for subsequent analyses.

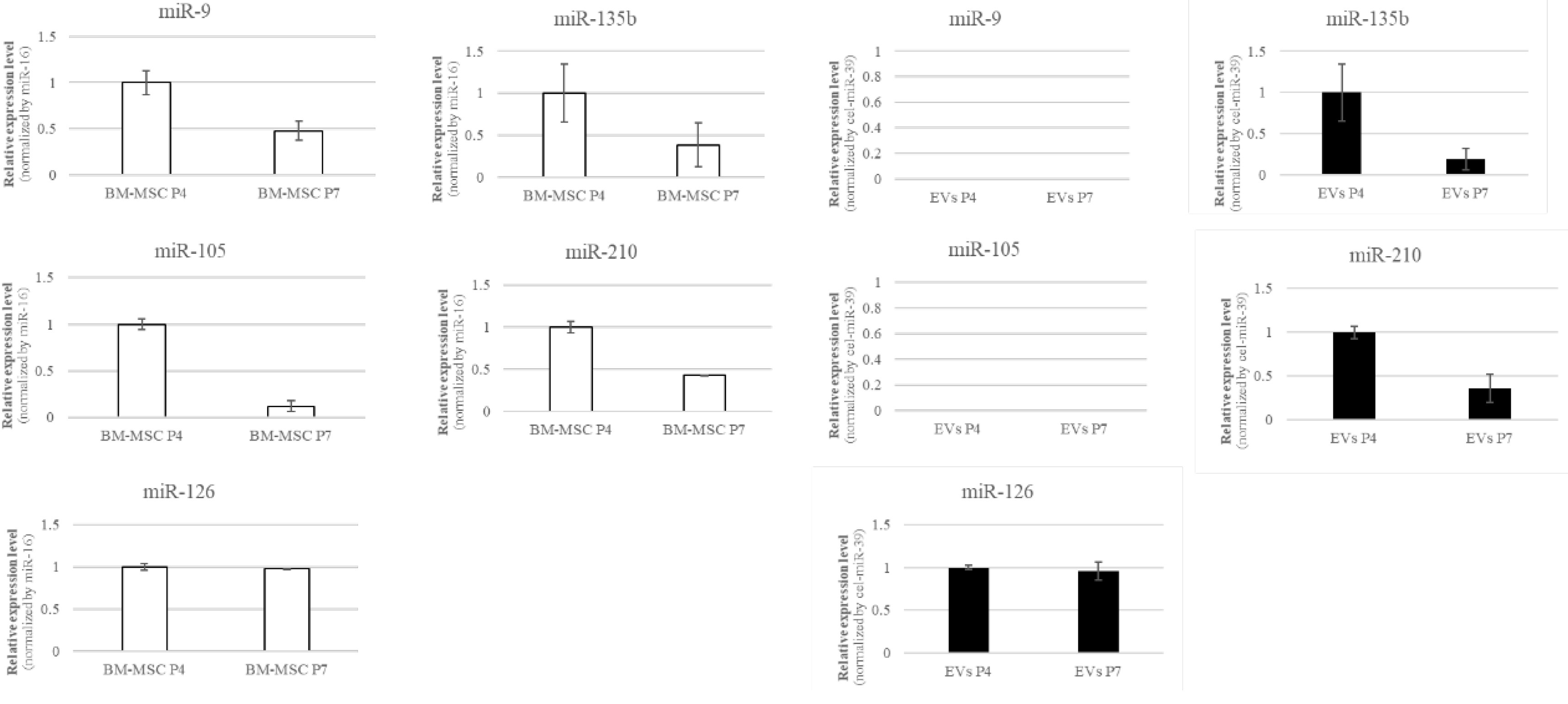

3.2. miRNA Variation in BM-MSCs

RT-qPCR analysis revealed age-dependent differences in the expression of several miRNAs (such as miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210) in BM-MSCs. In particular, BM-MSCs derived from aged donors tended to show lower expression levels of these miRNAs compared to those from young donors. Furthermore, noticeable inter-individual variability was observed even within the same age group (

Figure 3). These findings indicate that miRNA expression in BM-MSCs is influenced not only by chronological aging but also by donor-specific biological factors. Although it would be ideal to assess EV-associated miRNAs from elderly donors, this was not feasible due to their low proliferative capacity, making it impractical to obtain sufficient EVs.

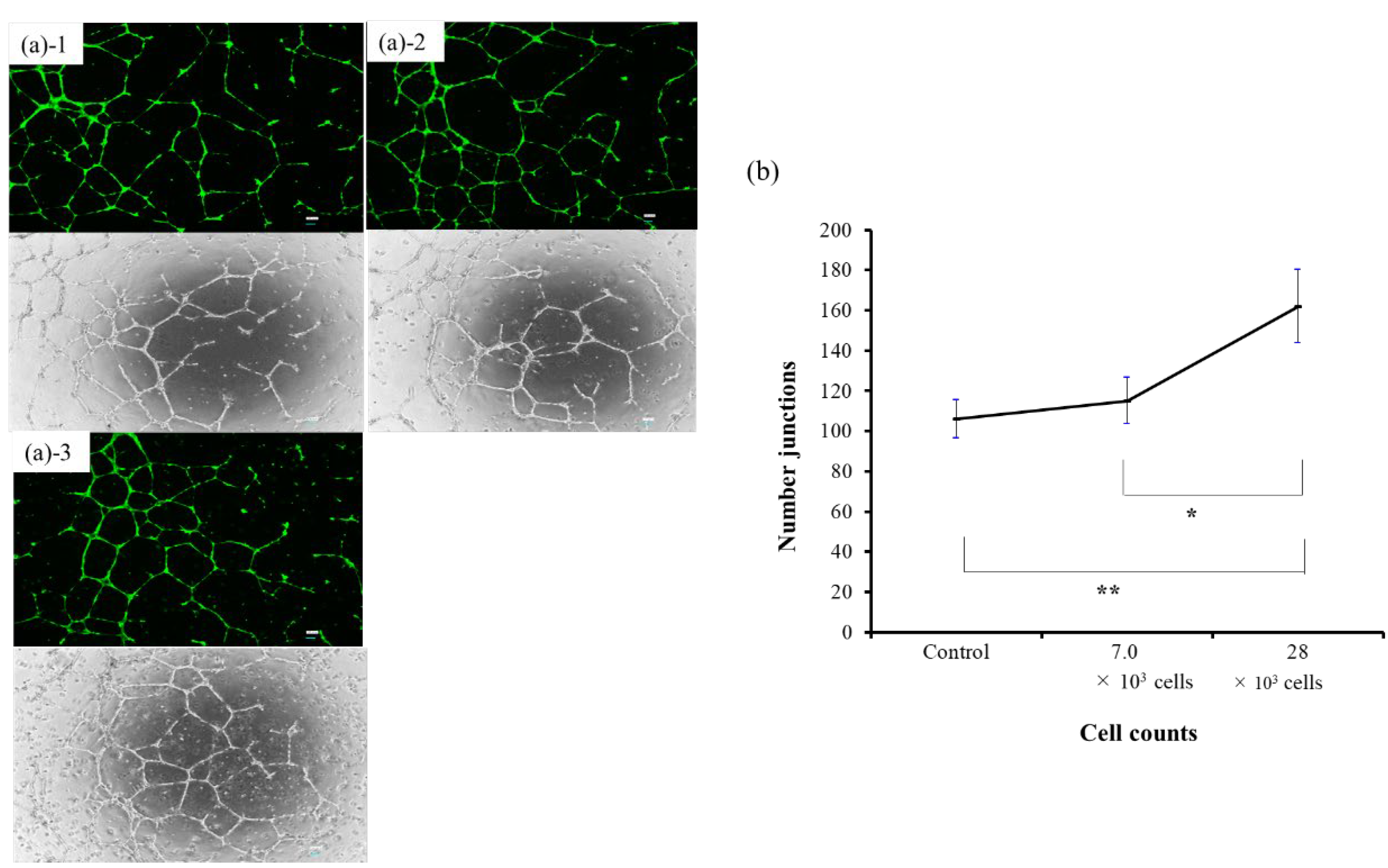

3.3. Tube Formation Assay Using co-Culture of BM-MSCs and HUVECs

In the tube formation assay using co-culture of BM-MSCs and HUVECs, angiogenesis—as measured by the number of junctions—increased significantly with higher BM-MSC cell numbers. The 28 × 10³ cell group showed a significant increase compared to both the 7.0 × 10³ group (p < 0.05) and the control group (p < 0.01), with clearly enhanced vascular-like structures observed morphologically (

Figure 4). These results suggest that BM-MSCs possess the ability to promote angiogenesis in vitro.

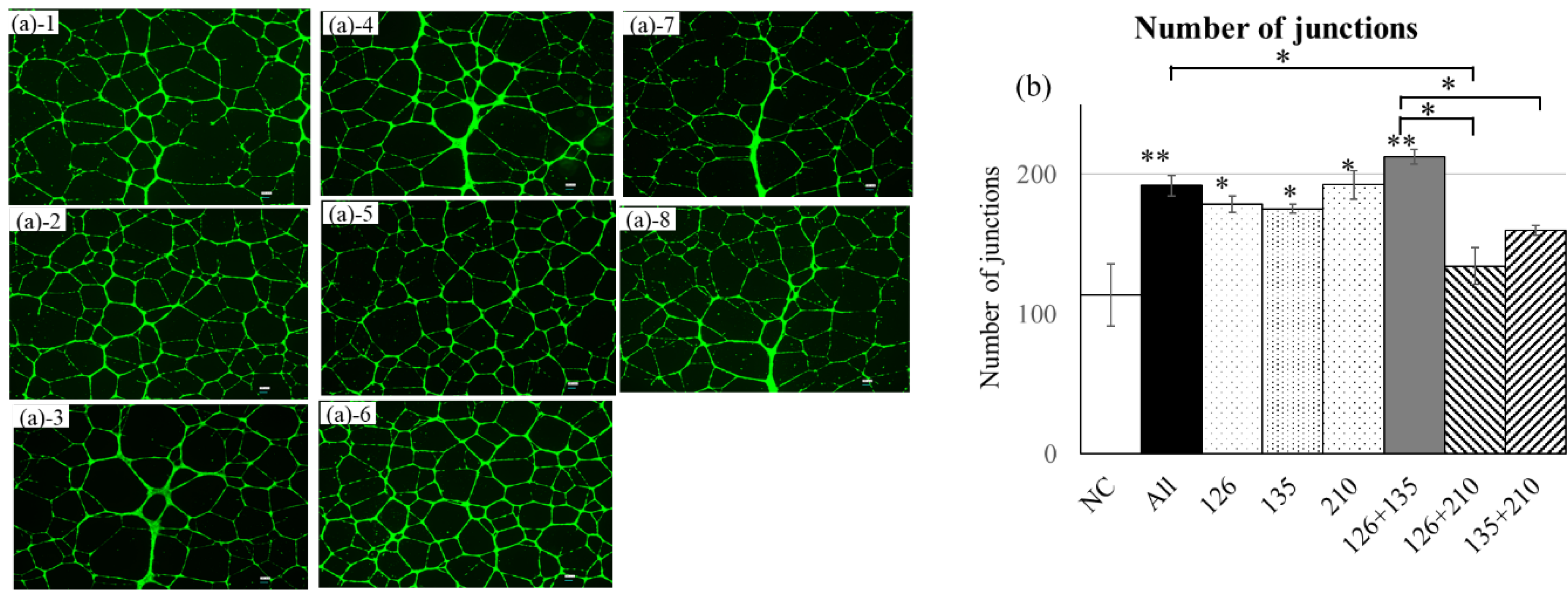

3.4. Tube Formation Assay in HUVECs Following mimicRNA Transfection

In the tube formation assay following mimicRNA transfection into HUVECs, miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210 each significantly enhanced angiogenesis compared with NC (number of junctions; p < 0.05 or p < 0.01). Among these, the combination of miR-126 and miR-135b showed the strongest pro-angiogenic effect (p < 0.001), and the triple combination (miR-126 + miR-135b + miR-210) also resulted in a significant increase (p < 0.01). In contrast, the combinations of miR-126 + miR-210 and miR-135b + miR-210 exhibited relatively limited effects, suggesting that co-transfection with miR-210 may partially attenuate the angiogenic potential (

Figure 5).

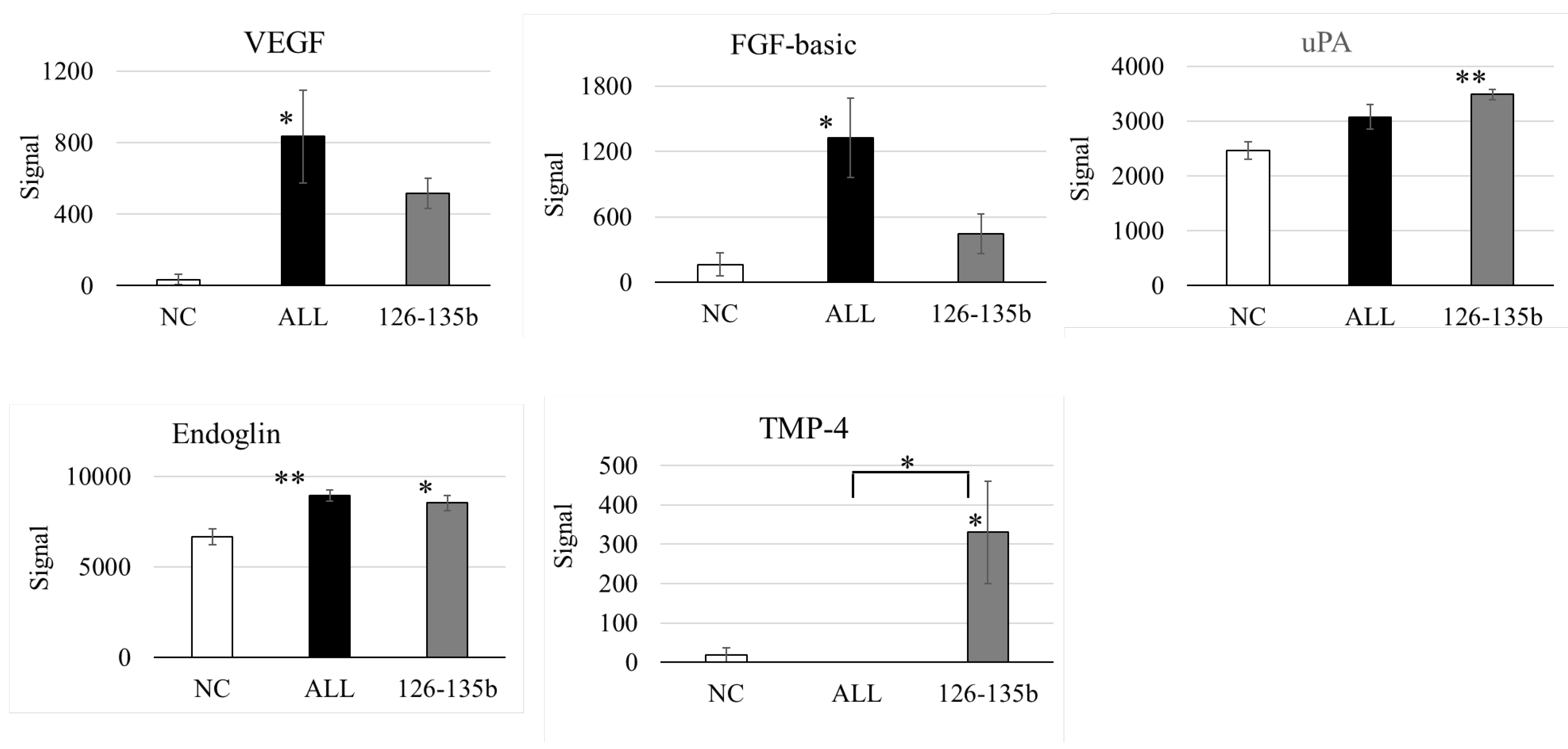

3.5. Protein Analysis in Tube Formation Assay by Mimic RNA Transfection into HUVECs

Co-transfection of miR-126 and miR-135b significantly increased the expression of multiple angiogenesis-related proteins, including VEGF, FGF, uPA, and Endoglin. The triple combination with miR-210 also upregulated these factors compared to the control group; however, no further enhancement was observed relative to the miR-126 + miR-135b group (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that multiple combinations of miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210 play an important role in promoting angiogenesis. It should be noted, however, that the results of this study are not based on in vivo experiments using MSC-derived EVs, but rather on forced incorporation of specific microRNAs into vascular endothelial cells.

While miR-9 and miR-105 were detected in BM-MSCs, their absence in EVs suggests a selective packaging mechanism. Elucidating these molecular pathways may be crucial for tailoring the therapeutic potential of MSC-derived EVs. Further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms that govern selective miRNA packaging and release to optimize therapeutic strategies for targeting ischemic tissues.

CLI remains refractory to conventional pharmacological, catheter-based, and surgical approaches. While a 2015 meta-analysis questioned the efficacy of angiogenic regenerative medicine [

19], and angiogenesis gene therapy using HGF vectors was discontinued in Japan after disappointing post-marketing results, our findings suggest that variability in angiomiR expression may contribute to inconsistent outcomes.

Analysis of miRNA expression in BM-MSCs revealed that miR-126 levels are higher in younger donors, whereas miR-210 expression exhibited significant individual variability, and miR-135b was unaffected by donor age. This suggests that younger MSCs may possess greater regenerative capacity, likely attributed to higher angiomiR activity. The age-related decline in miR-126 expression may partially explain the reduced angiogenic efficacy in older patients, a phenomenon closely associated with aging and the progression of ischemic diseases, including CLI.

Tube formation assays demonstrated a dose-dependent enhancement of angiogenesis in BM-MSC and HUVEC co-cultures, with higher MSC numbers (28 × 10³ cells) significantly promoting angiogenesis. This aligns with prior studies highlighting the pro-angiogenic effects of MSCs, primarily mediated through secreted factors, including miRNAs [

5,

6]. These findings underscore the paracrine role of EVs in MSC-mediated regeneration. These findings further support the rationale of our ongoing clinical trial using intramuscular BM-MSC transplantation in patients with CLI.

Transfection of HUVECs with miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210, both individually and in combination, significantly enhanced tube formation. Notably, the miR-126 + miR-135b combination and the triple combination of miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210 exhibited the most pronounced effects, suggesting interactions among these miRNAs. Interestingly, no significant differences were observed among the All group, the miR-126 group, the miR-135b group, the miR-210 group, and the miR-126 + miR-135b group, suggesting that these treatments may elicit a similar maximal pro-angiogenic effect through convergent molecular pathways. Furthermore, the total number of exosomes secreted by MSCs and the miRNA cargo loading per vesicle may reach a saturation threshold, limiting further enhancement of angiogenic activity. Indeed, tube formation assays with human endometrial MSC-derived exosomes showed a clear plateau in pro-angiogenic effect above 100 µg/mL, with 150–200 µg/mL failing to increase tube formation—consistent with saturation of exosome uptake or cargo capacity [

20]. Moreover, the biogenesis machinery that sorts miRNAs into exosomes imposes an upper limit on cargo packaging efficiency, so overexpression beyond this point does not yield additional functional gains [

21]. Finally, assuming that exosomal miRNAs drive the pro-angiogenic effect, these findings underscore the potential of developing engineered exosomes—produced via genetic technologies such as lentiviral vectors to load specific target miRNAs—as a more precise therapeutic modality, rather than relying on bulk conditioned media or simple miRNA overexpression cocktails [

22,

23].

Particularly, miR-126 plays a pivotal role in vascular stability and growth by targeting EVH1 domain-containing protein 1 (Spred1), a Sprouty-related protein, and PIK3R2, a regulatory subunit of PI3K [

13,

24]. miR-126 promotes VEGF and other growth factor signaling because Spred1 and PIK3R2 are negative regulators of cell signaling cascades and affect the MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways, respectively. Notably, miR-126 targets multiple pathways, including MAPK, PI3K, and PIK3R2. As targeting multiple signaling pathways is thought to fine-tune angiogenic responses, miR-126 may play a role in regulating the relationship between miR-135b and miR-210, both of which are involved in the HIF-1 pathway. The inhibition of miR-126 has been shown to reduce capillary density in the gastrocnemius muscle in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia [

25]. While limited studies address miR-135b, overexpression of MSCs increases Fst expression, a regulator of activin A, a key protein in inflammation, and VEGF [

26,

27].

PTPN1, suppressed by miR-210, has been shown to negatively regulate the activation of the VEGF receptor VEGFR2 and stabilize cell–cell adhesions by reducing the tyrosine phosphorylation of vascular endothelial cadherin [

28]. These results, derived from our in vitro tube formation assay and protein analysis (

Figure 6.1), provide mechanistic support for the therapeutic effect observed in our clinical study, which involves intramuscular administration of BM-MSCs for CLI. Moreover, while VEGF was the most strongly induced protein, we also observed significant upregulation of FGF and Endoglin, suggesting potential involvement of distinct signaling pathways. Although cross-talk with VEGF-related pathways cannot be excluded, FGF and Endoglin may reflect alternative or complementary mechanisms contributing to angiogenesis. Given that this conclusion is based solely on

Figure 6.1 data, it is important to clearly distinguish our experimental findings from generally known mechanisms.

These findings highlight the potential of combinatorial miRNA-based therapies for treating ischemic diseases by simultaneously targeting multiple angiogenic pathways. BM-MSC-derived EVs enriched with these miRNAs could represent a non-invasive and potentially effective therapeutic strategy for CLI, a condition characterised by limited treatment options and high morbidity and mortality. Leveraging miRNA-loaded EVs to promote angiogenesis opens a compelling avenue in regenerative medicine.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the role of combinatorial miRNAs secreted by MSCs in angiogenesis, providing novel insights into their potential for therapeutic application. However, significant challenges remain, particularly in achieving consistent and selective miRNA packaging into EVs. While this study highlights the age-related differences in miRNA expression, the small sample size and limited donor age range restrict the generalisability of the findings. A broader cohort would be necessary to confirm the influence of donor age on miRNA profiles and angiogenic potential. This study exclusively used BM-MSCs obtained from commercially available sources, which may not fully represent the variability seen in primary cells derived from patients with diverse clinical conditions, such as CLI or other comorbidities. Although miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210 combinations enhanced angiogenesis, their interactions and precise molecular mechanisms were not fully elucidated. This limits the ability to design targeted therapeutic strategies leveraging these miRNA combinations. While the in vitro data are promising, rigorous validation of in vivo CLI models is essential to establish the clinical utility of BM-MSC-derived EVs. By addressing these limitations, future research can refine the therapeutic application of BM-MSC-derived miRNAs and EVs for use in angiogenic regenerative medicine.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the potential of BM-MSC-derived EVs, particularly those enriched with miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210, to promote angiogenesis through modulation of multiple angiogenic pathways. The observed enhancement in tube formation in our in vitro co-culture model of BM-MSCs and HUVECs reflects the translational relevance of our clinical approach to treating CLI. Notably, protein expression analysis revealed that, beyond VEGF, factors such as FGF and Endoglin were also significantly upregulated, suggesting the involvement of both VEGF-dependent and independent signaling mechanisms. These findings highlight the therapeutic promise of combinatorial miRNA strategies, while also emphasizing the need for further studies to optimize EV-mediated delivery and confirm efficacy in vivo.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F., M.K., H.O., and T.O.; methodology, S.F., T.U.,M.K.; analysis, T.K., Y.W., T.N.; investigation, T.K., A.I.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.; writing—review and editing, S.F.; scientific advisory, M.K.,H.O., T.O.; project administration, S.F.; funding acquisition, S.F.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 20K09133 (S.F.).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daich Chikazu of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery for his valuable advice on the experiments, and the staff of the Nishi-Shinjuku Collaborative Research Center for providing access to the experimental equipment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

References

- Kullo, I.J.; Rooke, T.W. Clinical practice. Peripheral artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:861-71.

- Japan Circulation Society/Japan Society of Vascular Surgery Joint Guidelines. JCS/JSVS 2022 guideline on the management of peripheral arterial disease. 2022. https://www.jsvs.org/ja/publication/pub_pdf/2022040801b.pdf. Accessed 5 Dec 2024.

- Norgren, L.; Hiatt, W.R.; Dormandy, J.A.; Nehler, M.R.; Harris, K.A.; Fowkes, F.G.; et al. Intersociety consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:S5-67.

- Tateishi-Yuyama, E.; Matsubara, H.; Murohara, T.; Ikeda, U.; Shintani, S.; Masaki, H.; et al. Therapeutic angiogenesis for patients with limb ischemia by autologous transplantation of bone-marrow cells: a pilot study and a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:427-35.

- Fukuda, S.; Hagiwara, S.; Fukuda, S.; Yakabe, R.; Suzuki, H.; Yabe, S.G.; et al. Safety assessment of bone marrow derived MSC grown in platelet-rich plasma. Regen Ther. 2015;1:72-9.

- Fukuda, S.; Hagiwara, S.; Okochi, H.; Ishiura, N.; Nishibe, T.; Yakabe, R.; et al. Autologous angiogenic therapy with cultured mesenchymal stromal cells in platelet-rich plasma for critical limb ischemia. Regen Ther. 2023;24:472-8.

- Mikami, S.; Nakashima, A.; Nakagawa, K.; Maruhashi, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Kajikawa, M.; et al. Autologous bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cell implantation and endothelial function in a rabbit ischemic limb model. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e67739.

- Kordelas, L.; Rebmann, V.; Ludwig, A.K.; Radtke, S.; Ruesing, J.; Doeppner, T.R.; et al. MSC-derived exosomes: a novel tool to treat therapy-refractory graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia. 2014;28:970-3.

- Landskroner-Eiger, S.; Moneke, I.; Sessa, W.C. miRNAs as modulators of angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a006643.

- Wang, S.; Olson, E.N. AngiomiRs-Key regulators of angiogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:205-11.

- Zeng, Y.; Yao, X.; Liu, X.; He, X.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; et al. Anti-angiogenesis triggers exosomes release from endothelial cells to promote tumor vasculogenesis. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;8:1629865.

- Kim, D.Y.; Lee, S.-S.; Bae, Y.-K. Colorectal cancer cells differentially impact migration and microRNA expression in endothelial cells. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:6361-70.

- Fish, J.E.; Santoro, M.M.; Morton, S.U.; Yu, S.; Yeh, R.F.; Wythe, J.D.; et al. miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev Cell. 2008;15:272-84.

- Umezu, T.; Tadokoro, H.; Azuma, K.; Yoshizawa, S.; Ohyashiki, K.; Ohyashiki, J.H. Exosomal miR-135b shed from hypoxic multiple myeloma cells enhances angiogenesis by targeting factor-inhibiting HIF-1. Blood. 2014;124:3748-57.

- Fasanaro, P.; D’Alessandra, Y.; Di Stefano, V.; Melchionna, R.; Romani, S.; Pompilio, G.; et al. MicroRNA-210 modulates endothelial cell response to hypoxia and inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase ligand ephrin-A3. J Biol Chem. 2008;6;283:15878-83.

- Yoshioka, Y.; Kosaka, N.; Konishi, Y.; Ohta, H.; Okamoto, H.; Sonoda, H.; et al. Ultra-sensitive liquid biopsy of circulating extracellular vesicles using ExoScreen. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3591.

- Carpentier, G.; Berndt, S.; Ferratge, S.; Rasband, W.; Cuendet, M.; Uzan, G.; et al. Angiogenesis analyzer for ImageJ - A comparative morphometric analysis of “endothelial tube formation assay” and “fibrin bead assay”. Sci Rep. 2020;10:11568.

- Carpentier, G. Angiogenesis analyser for ImageJ-Gilles Carpentier research web site: computer image analysis. 2012. http://image.bio.methods.free.fr/ImageJ/? Angiogenesis-Analyzer-for-ImageJ&artpage=3-6. Accessed 5 Dec 2024.

- Peeters Weem, S.M.; Teraa, M.; de Borst, G.J.; Verhaar, M.C.; Moll, F.L. Bone marrow derived cell therapy in critical limb ischemia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo controlled trials. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50:775-83.

- 20. Vajihe Taghdiri Nooshabadi, Javad Verdi, Somayeh Ebrahimi-Barough, Javad Mowla, Mohammad Ali Atlasi, Tahereh Mazoochi, Elahe Valipour, Shilan Shafiei, Jafar Ai, Hamid Reza Banafshe. Endometrial Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosome Promote Endothelial Cell Angiogenesis in a Dose Dependent Manner: A New Perspective on Regenerative Medicine and Cell-Free Therapy. Arch Neurosci. 2019;6(4):e94041. [CrossRef]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Sánchez-Cabo, F.; Pérez-Hernández, D.; Vázquez, J.; Martin-Cofreces, N.; Martinez-Herrera, D.J.; Pascual-Montano, A.; Mittelbrunn, M.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. Sumoylated hnRNPA2B1 controls the sorting of miRNAs into exosomes through binding to specific motifs. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2980. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3980. PMID: 24356509; PMCID: PMC3905700.

- 22. Schwarz Genevieve, Ren Xuechen, Xie Wen, Guo Haitao, Jiang Yong, Zhang Jinyu. Engineered exosomes: a promising drug delivery platform with therapeutic potential. Front. Mol. Biosci.. 2025;12. [CrossRef]

- Dalmizrak, A.; Dalmizrak, O. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as new tools for delivery of miRNAs in the treatment of cancer. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022 Sep 26;10:956563. PMID: 36225602; PMCID: PMC9548561. [CrossRef]

- Kuhnert, F.; Mancuso, M.R.; Hampton, J.; Stankunas, K.; Asano, T.; Chen, C.Z.; et al. Attribution of vascular phenotypes of the murine Egfl7 locus to the microRNA miR-126. Development. 2008;135:3989-93.

- van Solingen, C.; Seghers, L.; Bijkerk, R.; Duijs, J.M.G.J.; Roeten, M.K.; van Oeveren-Rietdijk, A.M.; et al. Antagomir-mediated silencing of endothelial cell specific microRNA-126 impairs ischemia-induced angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1577-85.

- Juliana, V.; Laura, Z.; Wendt, C.; Kildare, M.; Lindoso, R.; Sang, H. Overexpression of mir-135b and mir-210 in mesenchymal stromal cells for the enrichment of extracellular vesicles with angiogenic factors. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0272962.

- Cabral, T.; Mello, L.G.M.; Lima, L.H.; Polido, J.; Regatieri, C.V.; Belfort, R.; et al. Retinal and choroidal angiogenesis: a review of new targets. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2017;3:31.

- Nakamura, Y.; Patrushev, N.; Inomata, H.; Mehta, D.; Urao, N.; Kim, H.W.; et al. Role of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B in vascular endothelial growth factor signaling and cell-cell adhesions in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:1182-91.

Figure 1.

Characterisation of BM-MSC-derived EVs. BM-MSC-derived EVs were characterised by particle size, distribution, and surface marker expression. NTA confirmed a particle size peak around 100 nm. Particle numbers per cell ranged from 1.5 × 104 to 2.5 × 104 in culture supernatant and 2.0 × 103 to 3.0 × 103 for EVs. ExoScreen confirmed EV recovery based on CD63-specific luminescence. (a) NTA revealed a peak particle size of approximately 100 nm, characteristic of EVs. (b): Relative particle number per cell determined using NTA. (c): Luminescence intensity per cell for the EV surface marker CD63 measured via ExoScreen.

Figure 1.

Characterisation of BM-MSC-derived EVs. BM-MSC-derived EVs were characterised by particle size, distribution, and surface marker expression. NTA confirmed a particle size peak around 100 nm. Particle numbers per cell ranged from 1.5 × 104 to 2.5 × 104 in culture supernatant and 2.0 × 103 to 3.0 × 103 for EVs. ExoScreen confirmed EV recovery based on CD63-specific luminescence. (a) NTA revealed a peak particle size of approximately 100 nm, characteristic of EVs. (b): Relative particle number per cell determined using NTA. (c): Luminescence intensity per cell for the EV surface marker CD63 measured via ExoScreen.

Figure 2.

miRNA expression analysis in BM-MSCs and their EVs. RT-qPCR was used to compare the expression of miRNAs in BM-MSCs and their derived EVs. Five miRNAs (miR-9, miR-105, miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210) were detected in BM-MSCs, while only three (miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210) were consistently present in the EVs, whereas miR-9 and miR-105 were expressed exclusively in BM-MSCs and were not detected in EVs. Therefore, this study focused on these three miRNAs to investigate EV-mediated functional effects. miRNA expression in BM-MSCs was normalized to miR-16, and that in EVs was normalized to cel-miR-39. .

Figure 2.

miRNA expression analysis in BM-MSCs and their EVs. RT-qPCR was used to compare the expression of miRNAs in BM-MSCs and their derived EVs. Five miRNAs (miR-9, miR-105, miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210) were detected in BM-MSCs, while only three (miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210) were consistently present in the EVs, whereas miR-9 and miR-105 were expressed exclusively in BM-MSCs and were not detected in EVs. Therefore, this study focused on these three miRNAs to investigate EV-mediated functional effects. miRNA expression in BM-MSCs was normalized to miR-16, and that in EVs was normalized to cel-miR-39. .

Figure 3.

Age- and donor-dependent variability in miRNA expression in BM-MSCs. RT-qPCR was conducted to compare miRNA expression levels in BM-MSCs derived from young and aged donors. Expression was normalized to the endogenous control miR-16, highlighting both age-related changes and inter-individual variability in miRNA profiles. Several miRNAs (e.g., miR-126, miR-135b, miR-210) showed a general decline in expression with aging; however, considerable variation was also observed among individuals within the same age group. These findings suggest that miRNA-mediated regulation of angiogenesis may be influenced by both age and donor-specific biological background.

Figure 3.

Age- and donor-dependent variability in miRNA expression in BM-MSCs. RT-qPCR was conducted to compare miRNA expression levels in BM-MSCs derived from young and aged donors. Expression was normalized to the endogenous control miR-16, highlighting both age-related changes and inter-individual variability in miRNA profiles. Several miRNAs (e.g., miR-126, miR-135b, miR-210) showed a general decline in expression with aging; however, considerable variation was also observed among individuals within the same age group. These findings suggest that miRNA-mediated regulation of angiogenesis may be influenced by both age and donor-specific biological background.

Figure 4.

Tube formation assay using co-culture of BM-MSCs and HUVECs. BM-MSCs were co-cultured with HUVECs to evaluate dose-dependent angiogenic effects. The 28 × 10³ cell group showed significantly increased junction numbers compared to the control and 7.0 × 103 cell groups (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively), with enhanced vascular morphology observed. (a) Phase-contrast images of each group: (a)-1: Control, (a)-2: 7.0 × 10³ cells, (a)-3: 28 × 10³ cells. (b) Quantitative analysis of angiogenesis (number of junctions).

Figure 4.

Tube formation assay using co-culture of BM-MSCs and HUVECs. BM-MSCs were co-cultured with HUVECs to evaluate dose-dependent angiogenic effects. The 28 × 10³ cell group showed significantly increased junction numbers compared to the control and 7.0 × 103 cell groups (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively), with enhanced vascular morphology observed. (a) Phase-contrast images of each group: (a)-1: Control, (a)-2: 7.0 × 10³ cells, (a)-3: 28 × 10³ cells. (b) Quantitative analysis of angiogenesis (number of junctions).

Figure 5.

Tube formation assay in HUVECs following mimicRNA transfection. Quantitative analysis of tube structure formation 24 hours after mimicRNA transfection in HUVECs. miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210 each significantly enhanced angiogenesis, with the combination of miR-126 and miR-135b showing the strongest effect (p < 0.001) compared with NC. The triple combination (miR-126 + miR-135b + miR-210) also induced a significant increase (p < 0.01) compared with NC. In contrast, dual combinations including miR-210 (miR-126 + 210 and miR-135b + 210) showed relatively weaker effects, suggesting a possible suppressive influence of miR-210. (a) Phase-contrast images: (a)-1 NC, (a)-2 All, (a)-3 miR-126, (a)-4 miR-135b, (a)-5 miR-210, (a)-6 miR-126+135b, (a)-7 miR-126+210, (a)-8 miR-135b+210. (b) Quantification of junctions. n = 3. NC: miRNA mimic (mirVana™ miRNA Mimic Negative Control #1, 4464058, Ambio) contains a scrambled sequence that does not match any known human miRNA or mRNA sequences.

Figure 5.

Tube formation assay in HUVECs following mimicRNA transfection. Quantitative analysis of tube structure formation 24 hours after mimicRNA transfection in HUVECs. miR-126, miR-135b, and miR-210 each significantly enhanced angiogenesis, with the combination of miR-126 and miR-135b showing the strongest effect (p < 0.001) compared with NC. The triple combination (miR-126 + miR-135b + miR-210) also induced a significant increase (p < 0.01) compared with NC. In contrast, dual combinations including miR-210 (miR-126 + 210 and miR-135b + 210) showed relatively weaker effects, suggesting a possible suppressive influence of miR-210. (a) Phase-contrast images: (a)-1 NC, (a)-2 All, (a)-3 miR-126, (a)-4 miR-135b, (a)-5 miR-210, (a)-6 miR-126+135b, (a)-7 miR-126+210, (a)-8 miR-135b+210. (b) Quantification of junctions. n = 3. NC: miRNA mimic (mirVana™ miRNA Mimic Negative Control #1, 4464058, Ambio) contains a scrambled sequence that does not match any known human miRNA or mRNA sequences.

Figure 6.

Protein expression analysis in HUVECs after miRNA mimic transfection. Co-transfection of miR-126 and miR-135b markedly increased angiogenesis-related proteins such as VEGF, FGF, uPA, and Endoglin. The triple combination (miR-126 + miR-135b + miR-210) also resulted in upregulation, but the enhancement was not superior to the double combination, suggesting a suppressive role of miR-210.

Figure 6.

Protein expression analysis in HUVECs after miRNA mimic transfection. Co-transfection of miR-126 and miR-135b markedly increased angiogenesis-related proteins such as VEGF, FGF, uPA, and Endoglin. The triple combination (miR-126 + miR-135b + miR-210) also resulted in upregulation, but the enhancement was not superior to the double combination, suggesting a suppressive role of miR-210.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).