Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of salivary biomarkers in CKD.

- -

- To compare salivary biomarkers with traditional blood and urine markers for CKD diagnosis and monitoring.

- -

- To assess which salivary biomarkers demonstrate the highest diagnostic performance and are most suitable for guiding dietary management, continuous monitoring, and referral for medical intervention or dialysis.

- -

- To explore how oral health factors and dental clinical workflows influence the reliability and integration of salivary diagnostics for CKD detection.

- -

- To assess the technologies and methodologies used to detect CKD-related biomarkers in saliva, including biosensors, spectrophotometry, and microfluidic devices.

- -

- To identify limitations and challenges in the clinical application of salivary diagnostics for CKD.

- -

- To propose future directions and standardization strategies for the implementation of saliva-based diagnostics.

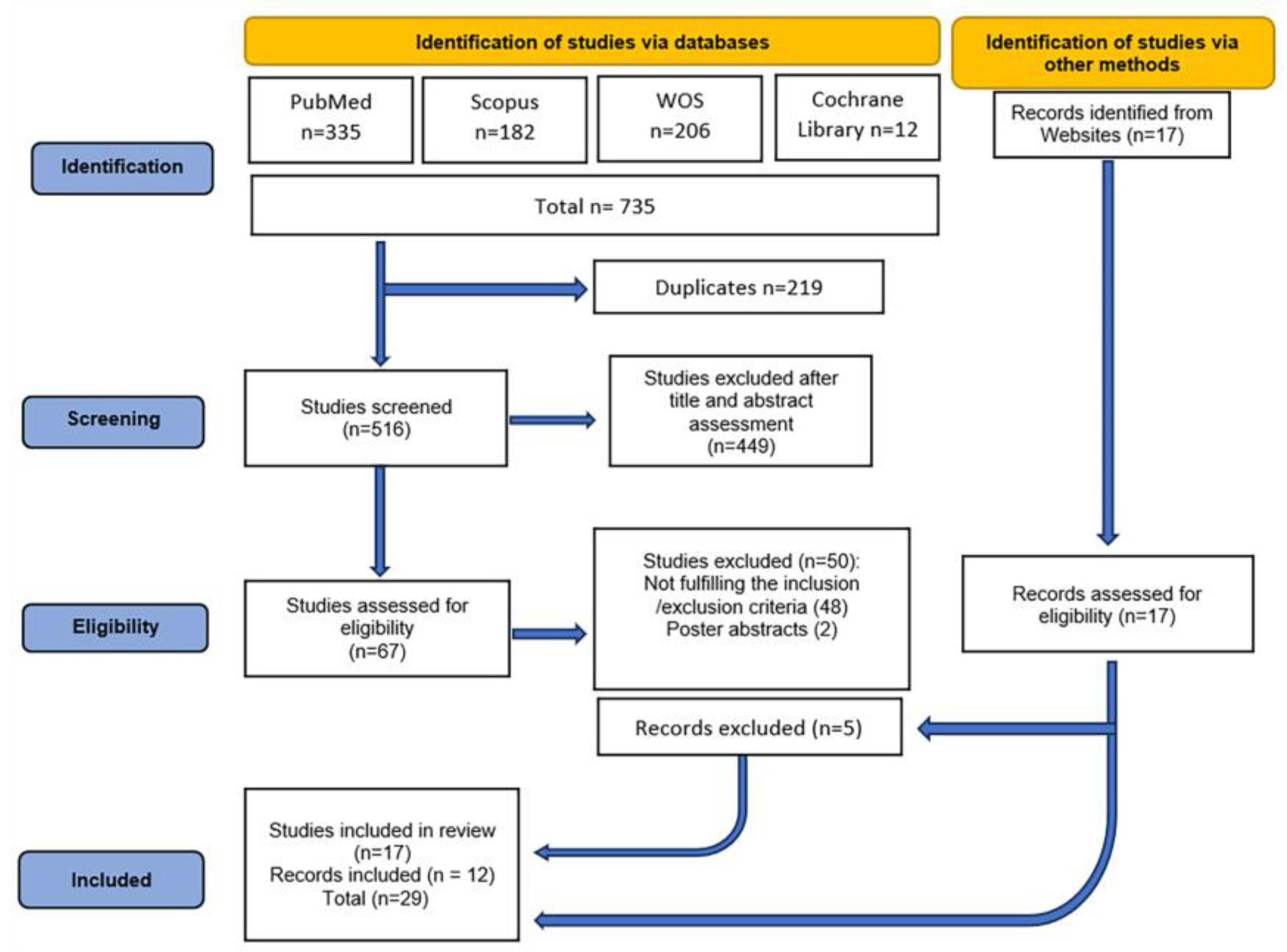

3. Results

- -

- 2 were poster abstracts presented at the 49th Turkish Physiology Congress of the Turkish Society of Physiological Sciences in 2024 [19],

- -

- -

- -

- 19 for not meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g., sample size fewer than 20 participants [46,47], absence of specific CKD patient cohorts [48], lack of a healthy comparator group [12,13,14,17,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57], lack of validated kidney function assessment methods [58,59], or inclusion of pediatric populations [60]).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic Kidney disease |

| eGFR | estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| ACR | Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ESKD | End-Stage Kidney Disease |

| DPV | Differential Pulse Voltammetry |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| Ag@GO | Silver nanoparticles (Ag) integrated with Graphene Oxide (GO), |

| GCE | Glassy Carbon Electrode |

| API5 | Apoptosis In-hibitor 5 |

| PI-PLC | Phosphatidylinositol-specific Phospholipase C |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| ATR-FTIR spectroscopy | Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study Design |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for scoping reviews |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| sCR | Serum creatinine |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| DMFT | Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography -Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| SOPs | Standardized operating procedures |

References

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picolo, B.U.; Silva, N.R.; Martins, M.M.; Almeida-Souza, H.O.; de Sousa, L.C.M.; Polveiro, R.C.; Goulart Filho, L.R.; Sabino-Silva, R.; Alonso-Goulart, V.; Saraiva da Silva, L. Salivary proteomics profiling reveals potential biomarkers for chronic kidney disease: a pilot study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1302637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangwanichgapong, K.; Klanrit, P.; Chatchawal, P.; Wongwattanakul, M.; Pongskul, C.; Chaichit, R.; Hormdee, D. Salivary attenuated total reflectance-fourier transform infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometric analysis: A potential point-of-care approach for chronic kidney disease screening. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2025, 52, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, P.; Stapleton, S.; Mosoyan, G.; Fligelman, I.; Tonar, Y.C.; Fleming, F.; Donovan, M.J. Analytical validation of a multi-biomarker algorithmic test for prediction of progressive kidney function decline in patients with early-stage kidney disease. Clin. Proteomics 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.W.; Tsai, Y.H.; Lu, Y.P.; Yang, J.T.; Chen, M.Y.; Huang, T.J.; Weng, R.C.; Tung, C.W. Application of a Novel Biosensor for Salivary Conductivity in Detecting Chronic Kidney Disease. Biosensors 2022, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, R.P.C.B.; de Andrade Vieira, W.; Siqueira, W.L.; Blumenberg, C.; de Macedo Bernardino, Í.; Cardoso, S.V.; Flores-Mir, C.; Paranhos, L.R. Saliva as an alternative to blood in the determination of uremic state in adult patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 2203–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RODRIGUES, R.P.C.B.; VIEIRA, de A. W.; SIQUEIRA, L.W.; AGOSTINI, B.A.; MOFFA, E.B.; PARANHOS, L.R. Saliva as a tool for monitoring hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz. Oral Res. 2020, 35, e016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshay, M.; Rhee, C.M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Novel monitoring of renal function and medication levels in saliva and capillary blood of patients with kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2022, 31, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasisi, T.J.; Raji, Y.R.; Salako, B.L. Salivary creatinine and urea analysis in patients with chronic kidney disease: a case control study. BMC Nephrol. 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, H.P. Salivary markers of systemic disease: noninvasive diagnosis of disease and monitoring of general health. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2002, 68, 170–174. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Lin, C.C.; Abemayor, E.; Wang, M.B.; Wong, D.T.W. The emerging landscape of salivary diagnostics. Periodontol. 2000 2016, 70, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, I.M.F.; Pessoa, M.B.; Leitão, A. de S.; Godoy, G.P.; Nonaka, C.F.W.; Alves, P.M. Salivary and Serum Biochemical Analysis from Patients with Chronic Renal Failure in Hemodialysis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clin. Integr. 2021, 21, e0036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temilola, D.O.; Bezuidenhout, K.; Erasmus, R.T.; Stephen, L.; Davids, M.R.; Holmes, H. Salivary creatinine as a diagnostic tool for evaluating patients with chronic kidney disease. 20, 6. [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, T.D.; Amarasiri, S.S.; Attanayake, A.P. Correlation Between Salivary and Serum Biomarkers of Kidney Function in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Attending the Nephrology Clinics at Teaching Hospital Karapitiya, Sri Lanka. Ceylon J. Sci. 2024, 53, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalčíková, A.G.; Pavlov, K.; Lipták, R.; Hladová, M.; Renczés, E.; Boor, P.; Podracká, Ľ.; Šebeková, K.; Hodosy, J.; Tóthová, Ľ.; et al. Dynamics of salivary markers of kidney functions in acute and chronic kidney diseases. Sci. Reports 2020 101 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diforti, J.F.; Cunningham, T.; Piccinini, E.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Piccinini, J.M.; Azzaroni, O. Noninvasive and Multiplex Self-Test of Kidney Disease Biomarkers with Graphene-Based Lab-on-a-Chip (G-LOC): Toward Digital Diagnostics in the Hands of Patients. 96, 5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogalcheva, A.N.; Konstantinova, D.; Pechalova, P. Salivary creatinine and urea in patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease could not be used as diagnostic biomarkers for the effectiveness of dialysis treatment. G. Ital. di Nefrol. organo Uff. della Soc. Ital. di Nefrol. 2018, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poster Communications. Acta Physiol. 2025, 241, e70004. [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, N.; Suchetha, M.; Philip, N.Y. Time Series Classification-Based Correlational Neural Network with Bidirectional LSTM for Automated Detection of Kidney Disease. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 4811–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Saddique, Z.; Mujahid, A.; Afzal, A. Discerning biomimetic nanozyme electrodes based on g-C3N4 nanosheets and molecularly imprinted polythiophene nanofibers for detecting creatinine in microliter droplets of human saliva. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 247, 115899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Surana, R.K.; Jha, S.K. Smartphone based optical biosensor for the detection of urea in saliva. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2018, 269, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepchuay, Y.; Costa, C.F.A.; Mesquita, R.B.R.; Sampaio-Maia, B.; Nacapricha, D.; Rangel, A.O.S.S. Flow-based method for the determination of biomarkers urea and ammoniacal nitrogen in saliva. Bioanalysis 2020, 12, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.H.; Hsieh, J.C.; Chen, C.C.; Zan, H.W.; Meng, H.F.; Kuo, S.Y.; Nguyễn, M.T.N. A low-cost, portable and easy-operated salivary urea sensor for point-of-care application. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 132, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Perera, G.; Dhanabalan, S.S.; Mahasivam, S.; Dong, D.; Cheong, Y.Z.; Xu, C.; Francis, P.; Elango, M.; Borkhatariya, S.; et al. Rapid Conductometric Sensing of Chronic Kidney Disease Biomarkers: Specific and Precise Detection of Creatinine and Cystatin C in Artificial Saliva. Adv. Sens. Res. 2024, 3, 2400042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.J.; Ryu, B.; Ahn, S.; Koh, W.G. A colorimetric biosensor based on a biodegradable fluidic device capable of efficient saliva sampling and salivary biomarker detection. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2023, 396, 134601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Aragón, A.; Conejo-Dávila, A.S.; Zaragoza-Contreras, E.A.; Dominguez, R.B. Pretreated Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode and Cu Nanoparticles for Creatinine Detection in Artificial Saliva. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.T.S.M.; Rangel, A.O.S.S.; Mesquita, R.B.R. A Microfluidic Paper-Based Device for Monitoring Urease Activity in Saliva. Biosensors 2025, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Sokolikova, M.; Ruiz-Gonzalez, A.; Kong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, M.; Mattevi, C.; Davenport, A.; et al. Ultrasensitive colorimetric detection of creatinine via its dual binding affinity for silver nanoparticles and silver ions. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 9114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, N.; Suchetha, M. A Computationally Efficient Correlational Neural Network for Automated Prediction of Chronic Kidney Disease. IRBM 2021, 42, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalasin, S.; Sangnuang, P.; Khownarumit, P.; Tang, I.M.; Surareungchai, W. Salivary Creatinine Detection Using a Cu(I)/Cu(II) Catalyst Layer of a Supercapacitive Hybrid Sensor: A Wireless IoT Device to Monitor Kidney Diseases for Remote Medical Mobility. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 5895–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro Nepomuceno, G.; Silva Neres dos Santos, R.; Avance Pavese, L.; Parize, G.; Pallos, D.; Sorelli Carneiro-Ramos, M.; da Silva Martinho, H. Periodontal disease in chronic kidney disease patients: salivomics by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 2023, 40, C93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddique, Z.; Shahzad, N.; Saeed, M.; Afzal, A. Biomimetic Polythiophene: g-C3N4 Nanotube Composites with Induced Creatinine and Uric Acid Specificity for Portable CKD and Gout Detection. ACS Appl. bio Mater. 2025, 8, 4262–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhvapathy, S.R.; Cho, S.; Gessaroli, E.; Forte, E.; Xiong, Y.; Gallon, L.; Rogers, J.A. Implantable bioelectronics and wearable sensors for kidney health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2025, 21, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Jung, C.Y.; Jin, D.Y.; Lee, T.; Kim, J.S. Wearable sensors for monitoring chronic kidney disease. Commun. Mater. 2024 51 2024, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, R.; Abdalla, M.M.I.; Caszo, B.A.; Somanath, S.D. Saliva urea nitrogen for detection of kidney disease in adults: A meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. PLoS One 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, T.W.; Decsi, D.B.; Punyadeera, C.; Henry, C.S. Saliva-based microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celec, P.; Tóthová, Ľ.; Šebeková, K.; Podracká, Ľ.; Boor, P. Salivary markers of kidney function - Potentials and limitations. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2016, 453, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkar, D.; Zhang, D.; Jeon, B.H.; Kim, K.H. Recent advances in wearable biosensors for non-invasive monitoring of specific metabolites and electrolytes associated with chronic kidney disease: Performance evaluation and future challenges. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 150, 116570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calice-Silva, V.; Raimann, J.G.; Wu, W.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Kotanko, P.; Levin, N. Salivary Urea Nitrogen as a Biomarker for Renal Dysfunction. Biomarkers Kidney Dis. 2015, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahri, J.; Allison, H.; Whitehead, K.A.; Muhamadali, H. The role of salivary metabolomics in chronic periodontitis: bridging oral and systemic diseases. Metabolomics 2025, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gallardo, C.L.; Arjona, N.; Álvarez-Contreras, L.; Guerra-Balcázar, M. Correction: Electrochemical creatinine detection for advanced point-of-care sensing devices: a review. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 31890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya; Darshna; Sammi, A. ; Chandra, P. Design and development of opto-electrochemical biosensing devices for diagnosing chronic kidney disease. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2023, 120, 3116–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas-González, A.; Ortiz-Martínez, M.; González-González, M.; Rito-Palomares, M. Enzymatic Methods for Salivary Biomarkers Detection: Overview and Current Challenges. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.Z.; Tian, G.; Ko, A.C.T.; Geissler, M.; Brassard, D.; Veres, T. Detection of renal biomarkers in chronic kidney disease using microfluidics: progress, challenges and opportunities. Biomed. Microdevices 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, A.D.; Purnima, S.; Atchaya, V.; Avesha, R.; Bharathi, S.D.; Prasanna, S. Salivary Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Diabetic Nephropathy - An Non- Invasive Approach. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2024, 17, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.P.C.B.; Aguiar, E.M.G.; Cardoso-Sousa, L.; Caixeta, D.C.; Guedes, C.C.F.V.; Siqueira, W.L.; Maia, Y.C.P.; Cardoso, S.V.; Sabino-Silva, R. Differential Molecular Signature of Human Saliva Using ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy for Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis. Braz. Dent. J. 2019, 30, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulides, N.; Mohanty, S.; Miller, C.S.; Langub, M.C.; Floriano, P.N.; Dharshan, P.; Ali, M.F.; Bernard, B.; Romanovicz, D.; Anslyn, E.; et al. Application of microchip assay system for the measurement of C-reactive protein in human saliva. Lab Chip 2005, 5, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajolani, A.; Alaee, A.; Nafar, M.; Kharazi-Fard, M.-J.; Ghods, K.; Rajolani, A.; Alaee, A.; Nafar, M.; Kharazi-Fard, M.-J.; Ghods, K.; et al. Association Between the Chemical Composition of Saliva and Serum in Patients with Kidney Failure. Nephro-Urology Mon. 2024 161 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna, L.A.; Koppolu, P.; Prince, J. Oral health in diabetic and nondiabetic patients with chronic kidney disease. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2017, 28, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walt, D.R.; Blicharz, T.M.; Hayman, R.B.; Rissin, D.M.; Bowden, M.; Siqueira, W.L.; Helmerhorst, E.J.; Grand-Pierre, N.; Oppenheim, F.G.; Bhatia, J.S.; et al. Microsensor arrays for saliva diagnostics. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1098, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelaars, S.; Lapré, C.S.M.; Raaijmakers, P.; Konings, C.J.A.M.; Mischi, M.; Bouwman, R.A.; van de Kerkhof, D. A novel LC-MS/MS assay for low concentrations of creatinine in sweat and saliva to validate biosensors for continuous monitoring of renal function. J. Chromatogr. B. Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2025, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuvaneswari, V.N.; Alexander, H.; Shenoy, M.T.; D, S.; Kanakasekaran, S.; Kumar, M.P.; Murugiah, V. Comparison of Serum Urea, Salivary Urea, and Creatinine Levels in Pre-Dialysis and Post-Dialysis Patients: A Case-Control Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e36685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, J.; Haward, R.; Roy Karintholil, A.; Sabu, J.; Austin Fernades, G. Exploring the Relationship Between Serum Creatinine and Salivary Creatinine Levels in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease in South India: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.D.R.; Hemmila, U.; Mzinganjira, H.; Mtekateka, M.; Banda, E.; Sibale, N.; Kawale, Z.; Phiri, C.; Dreyer, G.; Calice-Silva, V.; et al. Diagnostic performance of a point-of-care saliva urea nitrogen dipstick to screen for kidney disease in low-resource settings where serum creatinine is unavailable. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2020, 5, e002312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyneface, C.A.; Onengiyeofori, I.; Tamuno-Emine, D. Evaluation of Saliva for Monitoring Renal Function in Haemodialysis Patients at University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. Asian J. Biochem. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Wang, X.; Ding, X.; Hao, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.; Tang, Z.; Yang, F.; Cai, G.; et al. Salivary Glycopatterns as Potential Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Diagnosing and Reflecting Severity and Prognosis of Diabetic Nephropathy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 790586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imirzalioglu, P.; Onay, E.O.; Agca, E.; Ogus, E. Dental erosion in chronic renal failure. Clin. Oral Investig. 2007, 11, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaál Kovalčíková, A.; Pančíková, A.; Konečná, B.; Klamárová, T.; Novák, B.; Kovaľová, E.; Podracká, Ľ.; Celec, P.; Tóthová, Ľ. Urea and creatinine levels in saliva of patients with and without periodontitis. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 127, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goll, R.D.; Mookerjee, B.K. Correlation of biochemical parameters in serum and saliva in chronic azotemic patients and patients on chronic hemodialysis. J. Dial. 1978, 2, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry, A.A.; Khandhadiya, K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.G.; Prasad, M. Efficacy of Salivary Urea and Creatinine Compared to Serum Levels in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Clin. DIAGNOSTIC Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, S.; Shantaram, M. Salivary biomarkers for diagnosing renal functions in patients with type 2 diabetes: A correlative study. 40. [CrossRef]

- Khursheed, S.; Sarwar, S.; Hussain, D.; Shah, M.R.; Barek, J.; Malik, M.I. Electrochemical detection of creatinine at picomolar scale with an extended linear dynamic range in human body fluids for diagnosis of kidney dysfunction. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1353, 343978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korytowska-Przybylska, N.; Michorowska, S.; Wyczałkowska-Tomasik, A.; Pączek, L.; Giebułtowicz, J. Development of a novel method for the simultaneous detection of trimethylamine N-oxide and creatinine in the saliva of patients with chronic kidney disease - Its utility in saliva as an alternative to blood. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, J.E.; Broughton, A.; Selby, C. Salivary creatinine assays as a potential screen for renal disease. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 1996, 33 ( Pt 5) Pt 5, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.P.; Huang, J.W.; Lee, I.N.; Weng, R.C.; Lin, M.Y.; Yang, J.T.; Lin, C.T. A Portable System to Monitor Saliva Conductivity for Dehydration Diagnosis and Kidney Healthcare. Sci. Reports 2019 91 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padwal, M.K.; Momin, A.A.; Diwan, A.; Phade, V. Efficacy of Salivary Creatinine and Urea and their Association with Serum Creatinine and Urea Levels in Severe Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Indian J. Med. Biochem. 2023, 26, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.A.V.; Le, D.D. Dental condition and salivary characteristics in Vietnamese patients with chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2019, 17, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, D.S.; Babu, S.G.; Castelino, R.; Buch, S.A. Estimation of Serum and Salivary Creatinine and Urea Levels in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Case-Control Study. J. Indian Acad. Oral Med. Radiol. 2023, 35, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poposki, B.; Ivanovski, K.; Stefanova, R.; Dirjanska, K.; Rambabova-Bushljetik, I.; Ristovski, V.; Risteska, N. Salivary Markers in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Pril. (Makedonska Akad. na Nauk. i Umet. Oddelenie za Med. Nauk. 2023, 44, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsan, B.A.; Journal, A.U. Saliva As An Alternative Fluid For Kidney Diseases Assessment. Albaydha Univ. J. 2023, 5, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techatanawat, S.; Surarit, R.; Chairatvit, K.; Roytrakul, S.; Khovidhunkit, W.; Thanakun, S.; Izumi, Y.; Khovidhunkit, S. on P. Salivary and serum cystatin SA levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus or diabetic nephropathy. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 104, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trzcionka, A.; Twardawa, H.; Mocny-Pachońska, K.; Korkosz, R.; Tanasiewicz, M. Oral Mucosa Status and Saliva Parameters of Multimorbid Adult Patients Diagnosed with End-Stage Chronic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.L.; Evans, R.D.R.; Unwin, R.J.; Norman, J.T.; Rich, P.R. Assessment of Measurement of Salivary Urea by ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy to Screen for CKD. Kidney360 2021, 3, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatapathy, R.; Govindarajan, V.; Oza, N.; Parameswaran, S.; Pennagaram Dhanasekaran, B.; Prashad, K. V. Salivary creatinine estimation as an alternative to serum creatinine in chronic kidney disease patients. Int. J. Nephrol. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.A.V. Validation of the salivary urea and creatinine tests as screening methods of chronic kidney disease in Vietnamese patients. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2017, 75, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z. Metabolomic profiling of amino acids study reveals a distinct diagnostic model for diabetic kidney disease. Amino Acids 2023, 55, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Su, B.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Tang, X.; Liu, Y.; Author, C. Comparison and correlation study of polar biomarkers of CKD patients in saliva and serum by UPLC-ESI-MS. J. Adv. Med. Sci. 2019, 2, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarathinam, A.E.; Dineshkumar, T.; Rajkumar, K.; Rameshkumar, A.; Shruthi, T.A.; Alzahrani, K.J.; Alzahrani, F.M.; Halawani, I.F.; Patil, S. Validation of Diagnostic Utility of Salivary Urea in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease in Chennai: A Cross-Sectional Study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 26, 1868–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akai, T.; Naka, K.; Yoshikawa, C.; Okuda, K.; Okamoto, T.; Yamagami, S.; Inoue, T.; Yamao, Y.; Yamada, S. Salivary urea nitrogen as an index to renal function: a test-strip method. Clin. Chem. 1983, 29, 1825–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfeeq Salih Alsamarai, A.; Ayad Husain, A.; Abdul-Kader Saleh, T.; Mohamad Thabit, N. Salivary Cystatin C as a Biochemical Marker for Chronic Renal Failure. Eurasian J. Anal. Chem. 2018, 13, 01–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwini, C.; Priscilla David, M.; Runjhun, S. Comparative evaluation of creatinine in serum and saliva of chronic kidney disease patients. Glob. J. Res. Anal. 2023, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy El-Shalakany, A.; Said Abd Al-Baky Mashal, B.; Abd Al-Aziz Kora, M.; Sedkey Bader, R.; Hamdy, A.; Said Abd Al-Baky, B.; Abd Al-Aziz, M.; Sedkey, R. Clinical significance of saliva urea and creatinine levels in patients with chronic kidney disease. Menoufia Med. J. 2015, 28, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagalad, B.S.; Mohankumar, K.P.; Madhushankari, G.S.; Donoghue, M.; Kuberappa, P.H. Diagnostic accuracy of salivary creatinine, urea, and potassium levels to assess dialysis need in renal failure patients. Dent. Res. J. (Isfahan). 2017, 14, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilancio, G.; Cavallo, P.; Lombardi, C.; Guarino, E.; Cozza, V.; Giordano, F.; Palladino, G.; Cirillo, M. Salivary levels of phosphorus and urea as indices of their plasma levels in nephropathic patients. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2018, 32, e22449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024 207 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konta, T.; Asahi, K.; Tamura, K.; Tanaka, F.; Fukui, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Hirose, J.; Ohara, K.; Shijoh, Y.; Carter, M.; et al. The health-economic impact of urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio testing for chronic kidney disease in Japanese non-diabetic patients. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2024, 29, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostev, K.; Lang, M.; Tröbs, S.O.; Urbisch, S.; Gabler, M. The Underdiagnosis of Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with a Documented Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate and/or Urine Albumin–Creatinine Ratio in Germany. Med. 2025, Vol. 61, Page 843 2025, 61, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaidi, S. Emerging Biomarkers and Advanced Diagnostics in Chronic Kidney Disease: Early Detection Through Multi-Omics and AI. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surdu, A.; Foia, L.G.; Luchian, I.; Trifan, D.; Tatarciuc, M.S.; Scutariu, M.M.; Ciupilan, C.; Budala, D.G. Saliva as a Diagnostic Tool for Systemic Diseases—A Narrative Review. Med. 2025, Vol. 61, Page 243 2025, 61, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcheri, C.; Mitsiadis, T.A. Physiology, Pathology and Regeneration of Salivary Glands. Cells 2019, Vol. 8, Page 976 2019, 8, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.F.; Shen, Y.Y.; Zhang, M.C.; Lv, M.C.; Wang, T.Y.; Chen, X.Q.; Lin, J. Progress in salivary glands: Endocrine glands with immune functions. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2023, 14, 1061235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chibly, A.; Aure, M.; Patel, V.; Hoffman, M.P. Salivary gland function, development, and regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parraca, J.A.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Tomas-Carus, P.; Costa, A.R. Analyzing the Biochemistry of Saliva: Flow, Total Protein, Amylase Enzymatic Activity, and Their Interconnections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgiea, E.D.; Cristache, C.M.; Mihut, T.; Drafta, S.; Beuran, I.A. The Integration of Salivary pH Meters and Artificial Intelligence in the Early Diagnosis and Management of Dental Caries in Pediatric Dentistry: A Scoping Review. Oral 2025, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, N.S.; AlGhannam, S.M.; Almughaiseeb, A.A.; Bindawoad, F.A.; alduraibi, S.M.; Shenoy, M. A review on salivary constituents and their role in diagnostics. Bioinformation 2022, 18, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drafta, S.; Guita, D.M.; Cristache, C.M.; Beuran, I.A.; Burlibasa, M.; Petre, A.E.; Burlibasa, L. Could Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Levels IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, Total Antioxidant Status and Lactate Dehydrogenase Be Associated with Peri-Implant Bone Loss? A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusov, P.A.; Kotelevtsev, Y. V.; Drachev, V.P. Cortisol Monitoring Devices toward Implementation for Clinically Relevant Biosensing In Vivo. Molecules 2023, 28, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Description |

| P (Population) | Adults (≥18 years) diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (any stage) or individuals at risk of CKD (e.g., with diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease) |

| I (Intervention/Exposure) | Use of salivary biomarkers (e.g., urea, creatinine, ammonia, pH, uric acid, cystatin C) for the detection or monitoring of CKD, including application of digital diagnostic tools such as biosensors or lab-on-a-chip technologies |

| C (Comparator) | Traditional blood- and urine-based diagnostic methods (e.g., serum creatinine, eGFR, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, 24h creatinine clearance) |

| O (Outcomes) | Diagnostic accuracy metrics (sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, correlation coefficients, AUC); feasibility and clinical utility of salivary diagnostics |

| S (Study Design) | Observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, cohort), diagnostic accuracy studies, and clinical validation studies involving human participants |

| Author, Year, Location, Setting | Study Design | Participants (CKD/Control) | Biomarkers Investigated | Collection & Analysis Methods | Key Findings & Outcomes | Diagnostic Accuracy |

| Khursheed et al., 2025, Pakistan, University [63] | Cross-sectional | 27 total (saliva, serum, urine from patients with high/low creatinine, 9 controls) | Creatinine | Electrochemical detection via DPV with Ag@GO/TiO2-GCE sensor | Saliva creatinine recovery 91–97%; superior to Jaffe’s method | Sensitivity: 15.74 µA/pM.cm², LOD: 1.15 pM, AUC not reported |

| Picolo et al., 2025, Brazil, University [2] | Pilot cross-sectional | 10 ESKD, 10 controls | Proteomic markers (API5, PI-PLC, Sgsm2) | LC-MS/MS, amylase depletion | 3 proteins absent in CKD, present in controls | AUC: ~0.8, suggested biomarker potential |

| Tangwanichgapong et al., 2025, Thailand, University [3] | Cross-sectional matched-pair | 24 ESKD, 24 controls | Salivary spectral bands | ATR-FTIR spectroscopy | Clear biochemical spectral differences between ESKD and controls | Accuracy: 87.5–100%, Sensitivity: 75–100%, Specificity: 100% |

| Choudhry et al., 2024, India, University [61] | Cross-sectional | 30 CKD, 30 controls | Urea, Creatinine | Passive drool, autoanalyzer | Significant group difference; strong correlations | Urea AUC: 0.78, Sensitivity: 90%, Creatinine AUC: 0.86, Sensitivity: 89% |

| Ashwini et al., 2023, India, Hospital [82] | Cross-sectional | 20 CKD (stages 3–5), 20 controls | Creatinine | Spitting after fasting; Jaffe’s method | Strong serum/saliva correlation | AUC: 0.879, Sensitivity: 75%, Specificity: 90% |

| Korytowska-Przybylska et al., 2023, Poland, University [64] | Observational | 31 CKD, 20 controls | TMAO, Creatinine | Salivette swab, LC-MS/MS | TMAO more effective for stage IV discrimination | No AUC; correlation with CKD stage |

| Nagarathinam et al., 2023, India, Hospital [79] | Cross-sectional | 150 CKD across 5 stages / 30 controls | Urea | Unstimulated saliva; spitting; GLDH enzymatic assay | Salivary urea progressively increased across CKD stages | AUC: 0.917; Sensitivity: 88%, Specificity: 84%, Cutoff: 28.25 mg/dL |

| Pillai et al., 2023, India, Dental Hospital [69] | Case-control | 120 total (30 controls, 90 CKD stage 3–5) | Urea, Creatinine | Spit technique, centrifuge, colorimetry | Significant correlation between saliva and serum | No diagnostic metrics |

| Poposki et al., 2023, N. Macedonia, University [70] | Cross-sectional | 32 CKD (stages 2–5), 20 controls | Urea, Creatinine, Albumin, Uric acid | Unstimulated saliva, centrifuge | Salivary urea correlated with CKD stage | No AUC; correlation stats given |

| Shamsan, 2023, Yemen, Sana’a University [71] | Cross-sectional | 59 renal disease patients / 20 controls | Multiple electrolytes, Creatinine, Urea, TP, Albumin | Unstimulated saliva; colorimetry via Chemray 240 | Elevated renal biomarkers across all saliva samples | No diagnostic metrics; statistically significant |

| Wang et al., 2023, China, University [77] | Observational | 90 total (30 DN,30 Type II DM, 30 controls) | Amino acids (arginine, valine, histidine) | UPLC-MS/MS | Combined biomarker model highly predictive | Combined AUC: 0.957, Saliva Arginine AUC: 0.75 |

| Lin et al., 2022, Taiwan, Hospital | Pilot cross-sectional | 214 adults, CKD prevalence 11.2% | Conductivity (indirect biomarkers) | Swab collection + biosensing probe | Conductivity correlates with CKD indicators | AUC: 0.648 (conductivity alone), 0.798 with age/gender/weight |

| Lin et al., 2022, UK, University College London [5] | Diagnostic accuracy | 20 CKD (stages 1–5), 6 controls | Urea | ATR-FTIR spectroscopy | Significant differentiation by stage | AUC: up to 1.00 (CKD 4–5), Sensitivity: 100%, Specificity: up to 100% |

| Padwal et al., 2022, India, Hospital [67] | Case-control | 50 CKD (stages 4–5), 50 controls | Creatinine, Urea | Spitting method, enzymatic and Jaffe’s methods | Significant elevation in CKD; strong correlations | Creatinine AUC: 1.000, Sensitivity/Specificity: 100%; Urea AUC: 0.98 |

| Trzcionka et al., 2021, Poland, University [73] | Observational | 180 CKD on dialysis, 48 controls | Saliva flow, pH, buffering | Saliva-Check buffer kit | Hemodialysis reduces flow, alters buffer | No diagnostic metrics |

| Harish et al., 2020, India, University [62] | Observational | 180 total (90 controls, 90 diabetics ± nephropathy) | Urea, Creatinine, Glucose, Uric acid | Fasting, spitting, centrifuge, autoanalyzer | CKD group shows elevated levels; saliva tracks serum well | No AUC reported; significant correlations |

| Lu et al., 2019, Taiwan, University [66] | Clinical validation | 30 total (10 CKD, 10 healthy adults, 10 farmers) | Saliva conductivity | Swab collection, Au electrode sensing | Significant differences across groups | Sensitivity: 93%, Specificity: 80% |

| Pham & Le, 2019, Vietnam, Hospital [68] | Cross-sectional | 111 CKD, 109 non-CKD | Urea, Creatinine, Flow rate | Dual saliva collection, chem analyzer | Xerostomia & DMFT worsen with CKD stage | Regression R² for flow rate: 0.75 |

| Techatanawat et al., 2019, Thailand, Hospital [72] | Observa tional | 82 subjects (29 DM, 20 DN,8 NDIN, 25 controls) | Cystatin SA | ELISA, proteomics | Cystatin SA tracks nephropathy severity | Salivary levels showed upward trends; no AUC reported |

| Yan et al., 2019, China, University [78] | Observational | 27 CKD / 27 controls | L-phenylalanine, L-tryptophan, Creatinine | LC-MS/MS with hydrophilic chromatography | Salivary levels elevated in CKD; significant correlation | Combined AUC: 0.936, Sensitivity: 88.9%, Specificity: 92.6% |

| Alsamarai et al., 2018, Iraq, University [81] | Case-control | 29 CKD, 20 controls | Cystatin C, Urea, Creatinine | ELISA, colorimetric methods | Cystatin C shown as superior saliva marker | No AUC reported |

| Bilancio et al., 2018, Italy, University [85] | Observational | 30 CKD, 15 controls | Phosphorus, Urea | Salivette method, molybdate UV, NADH methods | Saliva correlates highly with plasma; reproducible method | No diagnostic metrics; strong correlations reported |

| Pham 2017, Vietnam, University [76] | Diagnostic study | 112 CKD, 108 controls | Urea, Creatinine | Spitting after fasting, analyzer | CKD group had elevated levels; strong correlation | Creatinine AUC: 0.92, Sensitivity: 86.5%, Specificity: 87.2% |

| Bagalad et al., 2016, India, University [84] | Case-control | 41 CKD, 41 controls | Urea, Creatinine, Electrolytes | Spit method, centrifuge, autoanalyzer | All CKD biomarkers elevated; cutoff values established | Creatinine AUC: 0.90, Sensitivity: 93%, Specificity: 90% |

| Lasisi et al., 2016, Nigeria, University [9] | Cross-sectional | 50 CKD (stages 4–5), 49 controls | Urea, Creatinine | Unstimulated whole saliva; Jaffe & Marsh methods | Salivary levels significantly elevated; strong correlation with serum | Creatinine AUC: 0.97, Sensitivity: 94%, Specificity: 85% |

| Abeer Hamdy, 2015, Egypt, University [83] | Cross-sectional | 40 CKD (incl. ESKD) / 10 healthy controls | Urea, Creatinine | Unstimulated saliva; passive drool; colorimetric and rate techniques | Significant serum–saliva correlation across CKD stages | Creatinine AUC: 0.876; Sensitivity: 92%, Urea AUC: 0.796; Sensitivity: 90% |

| Venkatapathy et al., 2014, India, University [75] | Case-control | 105 CKD (stage 4/5), 37 controls | Creatinine | Spitting technique; autoanalyzer; Jaffe method | Salivary creatinine elevated; strong correlation with serum | AUC: 0.967; Sensitivity: 97.14%, Specificity: 86.5%; Cutoff: 0.2 mg/dL |

| Lloyd et al., 1996, UK, Hospital [65] | Diagnostic accuracy | 26 CKD / 23 healthy | Creatinine | Stimulated mixed saliva; chewing gum; Jaffe rate reaction | Salivary creatinine significantly elevated; strong CKD-specific correlation | Sensitivity: up to 100%, Specificity: up to 100%, AUC: ~0.97 |

| Akai et al., 1983, Japan, University [80] | Method validation | 44 CKD / 12 controls | Urea nitrogen | Dry-reagent test strip; reflectance spectrometer | High correlation (r = 0.93) with serum levels; method simple and reliable | No AUC; r values indicate diagnostic potential |

| Biomarker | Study | AUC | Sensitivity / Specificity | Additional Observations |

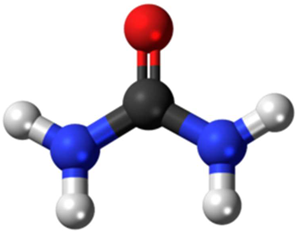

Creatinine (2-Amino-1-methyl-5H-imidazol-4-one)

|

Padwal 2022[67] | 1.000 | 100% / 100% | Excellent accuracy using enzymatic and Jaffe’s methods |

| Venkatapathy 2014[75] | 0.967 | 97.14% / 86.5% | Strong serum correlation; cutoff: 0.2 mg/dL | |

| Lasisi 2016[9] | 0.970 | 94% / 85% | Strong correlation with serum | |

| Pham 2017[76] | 0.920 | 86.5% / 87.2% | Based on fasting samples | |

| Bagalad 2016[84] | 0.900 | 93% / 90% | Cutoff values established | |

| Abeer Hamdy 2015[83] | 0.876 | 92% / not reported | Good correlation with CKD stage | |

| Ashwini 2023[82] | 0.879 | 75% / 90% | Good serum correlation; Jaffe’s method used | |

| Choudhry 2024[61] | 0.860 | 89% / not reported | Passive drool method | |

| Khursheed 2025[63] | Not reported | Sensitivity: 15.74 µA/pM.cm² | Electrochemical detection; strong recovery rates | |

Urea (Carbonic diamide)

|

Padwal 2022[67] | 0.980 | Not specified | Colorimetric method |

| Nagarathinam 2023[79] | 0.917 | 88% / 84% | Clear stage-wise increase; GLDH enzymatic assay | |

| Abeer Hamdy 2015[83] | 0.796 | 90% / not reported | Passive drool technique | |

| Choudhry 2024[61] | 0.780 | 90% / not reported | Saliva/serum correlation-strong | |

| Ashwini 2023[82] | Not reported | 75% / 90% | Spitting technique after fasting |

| Biomarker | Diagnostic Potential | Study / Additional Observations |

| TMAO | Correlated with stage IV | Korytowska 2023[64] / may help in stage-specific detection |

| Cystatin (SA, C) | Trend correlates with severity | Techatanawat 2019[72]; Alsamarai 2018[81] |

| Proteins (API5, PI-PLC, Sgsm2) | Present in controls, absent in CKD | Picolo 2025[2] /AUC ~0.8 |

| L-phenylalanine & L-tryptophan | Combined AUC = 0.936 | Yan 2019[78] |

| Conductivity | AUC: 0.648 (alone), 0.798 with demographics | Lin 2022[5] ; Lu 2019[66] / showed 93% sensitivity |

| pH | Average salivary pH was:ϦHigher in the control group (~7.0)ϦLower in CKD patients, especially those with diabetes (e.g., 5.96 in CKD + diabetes group) | Trzcionka 2021[73]/ pH was not directly used as a diagnostic marker, but is an indirect indicator of salivary alterations in CKD, particularly in advanced stages / comorbid conditions.Ϧ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).