Submitted:

10 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

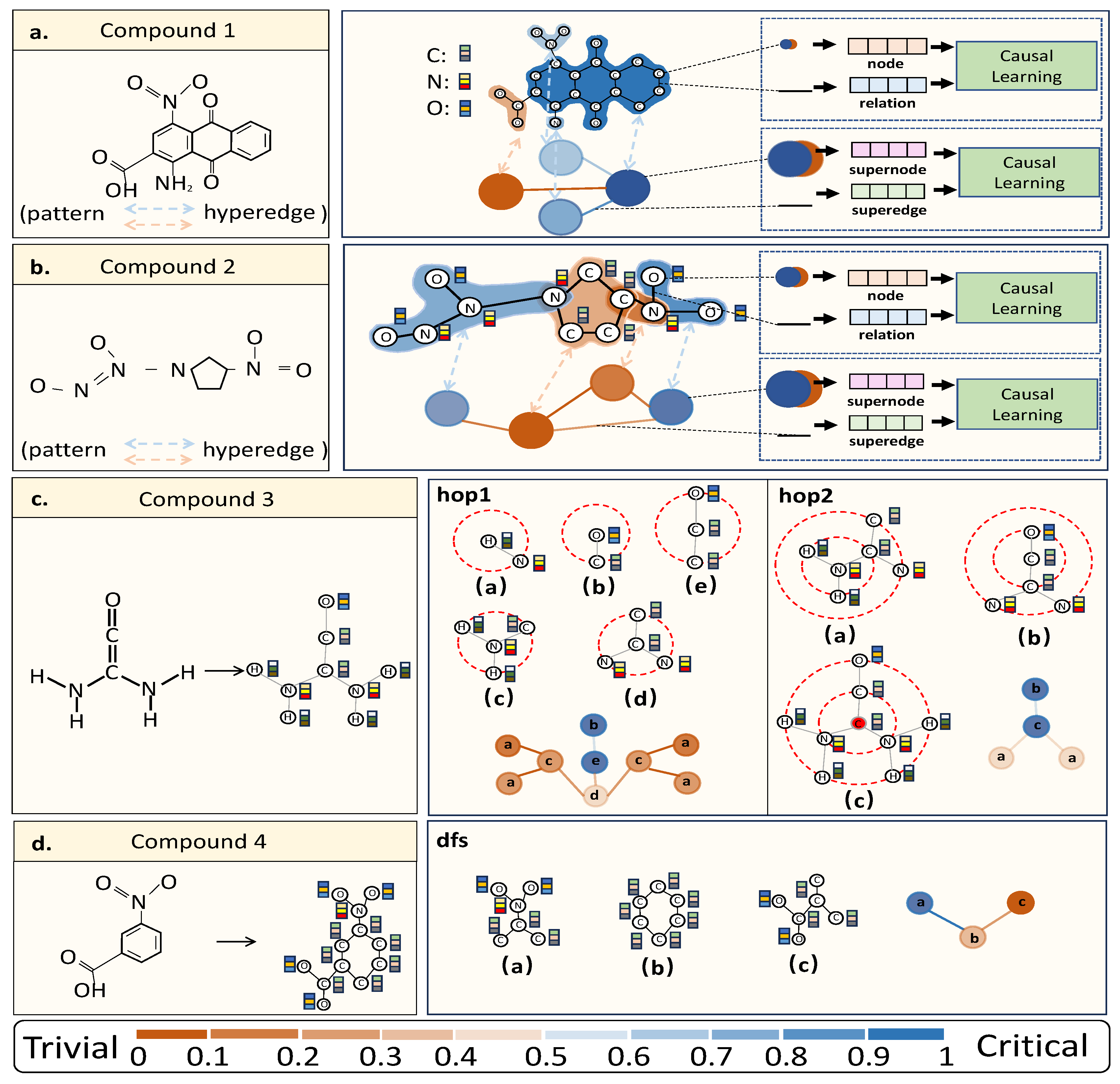

- We employ hypergraph neural networks to learn the molecular graph representations at the pattern level.

- We propose a structure-aware mechanism to capture the structural information within each pattern in hypergraph neural networks and introduce a self-supervised global-local mutual information mechanism by leveraging a well-designed discriminator to obtain more distinctive embeddings of graphs.

- We effectively capture critical patterns and critical relationships by utilizing the backdoor adjustment of causal learning, improving the generalization ability and performance of models.

- Our proposed HSCGL also facilitates the visualization of vital patterns for drug discovery, aiding researchers in identifying key components for effective drug design and development. Extensive experiments and ablation study on real-world and synthetic datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of our HSCGL.

2. Related Work

2.1. Causality in Graph Learning

2.2. Hypergraph in Improving Expressive Ability

3. Methods

3.1. Notations

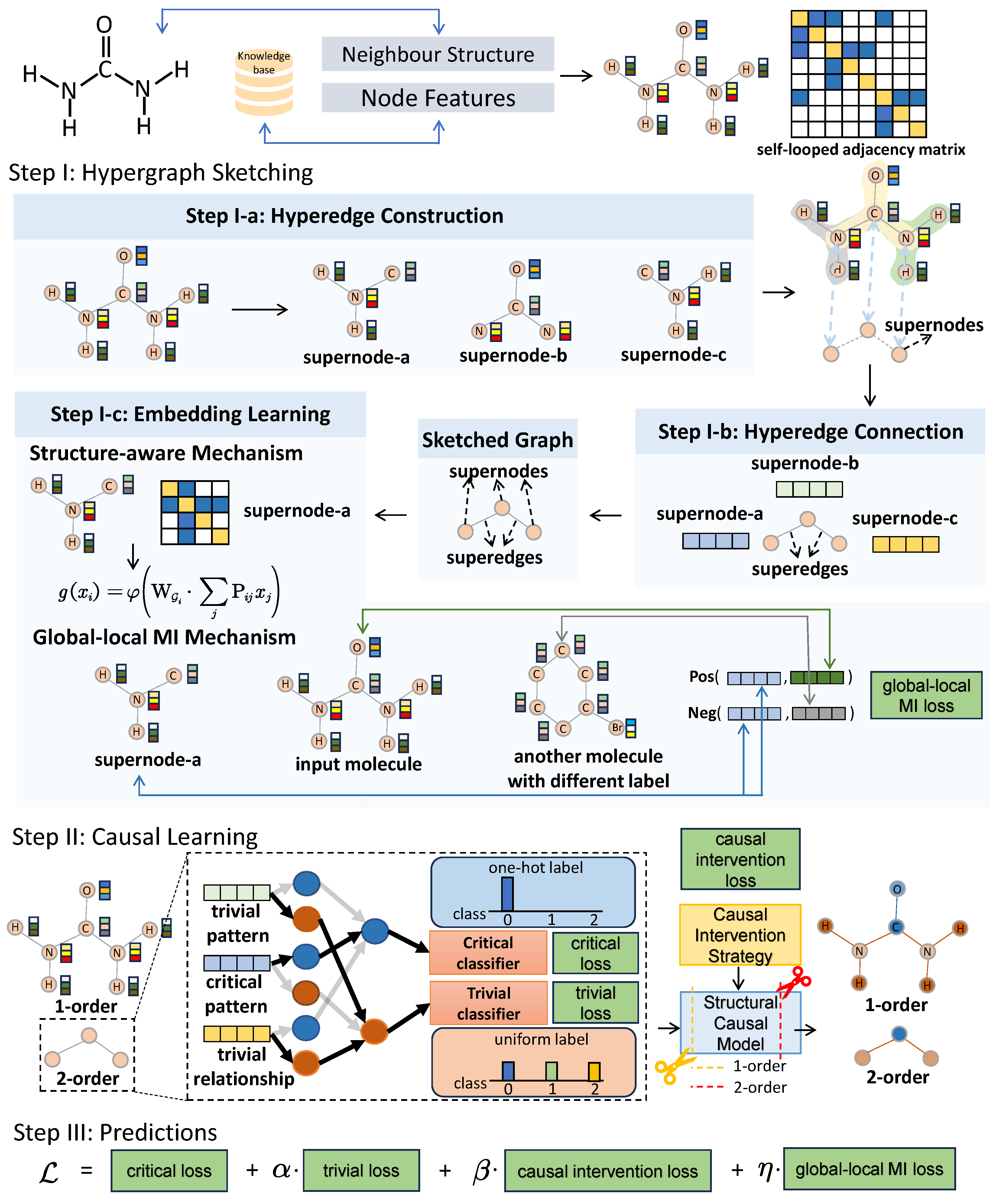

3.2. Overview of HSCGL

3.3. Step I: Hypergraph Sketching

3.3.1. Step I-a: Hyperedge Construction

3.3.2. Step I-b: Hyperedge Connection

3.3.3. Step I-c: Embedding Learning

3.4. Step II: Causal Learning

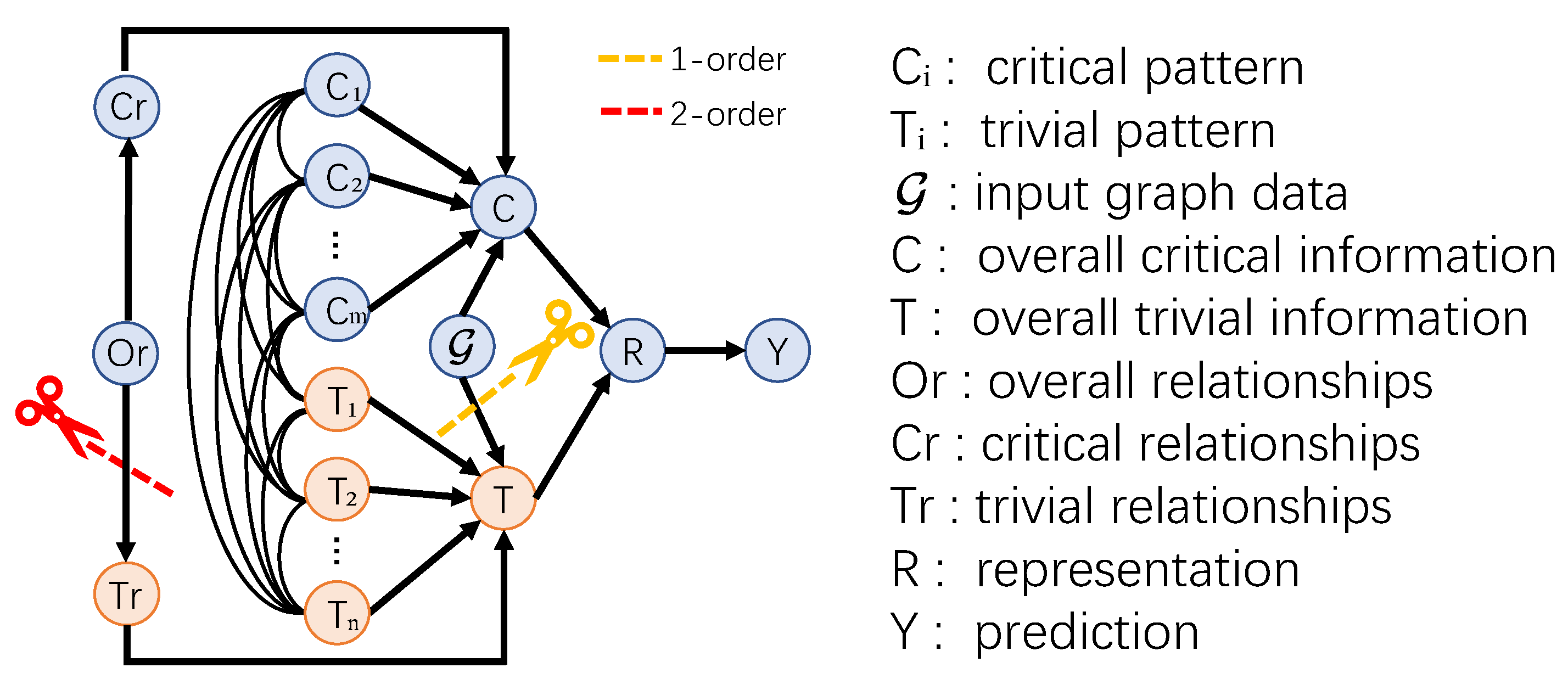

3.4.1. Structural Causality in HNNs

- . A molecule graph possesses both and , which affect the prediction of differently. The variable denotes the overall critical information, including critical patterns and critical relationships, that truly reflect the intrinsic property of the graph data. While represents the overall trivial information that usually disturb to false predictions.

- , and . The overall critical information are composed of critical patterns , which are represented by hyperedges, and critical relationships . The same to the overall trivial information which are composed of trivial patterns , and trivial relationships .

- . This link indicates the 2-order relationship between critical patterns and between critical patterns and trivial patterns. So as .

- . The variable captures overall relationships, encompassing those between critical patterns, between trivial patterns, and between critical patterns and trivial patterns. Here, includes not only the 2-order trivial relationships , but the 2-order critical relationships , which guide predictions.

- . The variable is the embedding made of and in graph learning methods.

- . The classifier will make prediction based on the graph representation of the input graph .

3.4.2. Backdoor Adjustment

- The marginal probability is not affected by the intervention. Thus, is equivalent to the vanilla probability . Similarly, the conditional probability is not affected by the intervention on so that is equivalent to the vanilla probability .

- Due to the intervention on , resulting in the independence of and , the conditional probability is equivalent to the probability .

- By refining and into the patterns and and the 2-order relationships and , we conclude that , and , , and .

3.4.3. Causal Intervention Strategy

3.5. Step III: Predictions

4. Results

4.1. Datasets

| Models | MUTAG | NCI1 | PROTEINS | PTC-FR | PTC-FM | PTC-MM | Mutagenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sGIN | 85.73 | 64.33 | 66.48 | 66.38 | 64.76 | 68.68 | 68.53 |

| MinCutNet | 88.83 | 72.31 | 76.73 | 67.51 | 65.44 | 67.56 | 78.33 |

| mewispool | 78.65 | 73.40 | 73.40 | 65.82 | 61.32 | 62.50 | 80.51 |

| dropGNN | 89.97 | 79.12 | 71.79 | 68.37 | 66.17 | 67.84 | 81.25 |

| 89.36 | 72.17 | 77.10 | 66.67 | 63.88 | 68.10 | 73.74 | |

| 88.86 | 70.19 | 76.83 | 67.11 | 63.31 | 67.20 | 73.30 | |

| 88.30 | 70.54 | 76.64 | 67.81 | 63.61 | 68.11 | 73.53 | |

| DiffWire | 88.27• | 71.36• | 76.64• | 67.46• | 63.33• | 68.42• | 73.55• |

| CAL | 89.83• | 81.90• | 68.39• | 66.45• | 67.65• | 83.05• | |

4.2. Experimental Settings

4.3. Research Questions

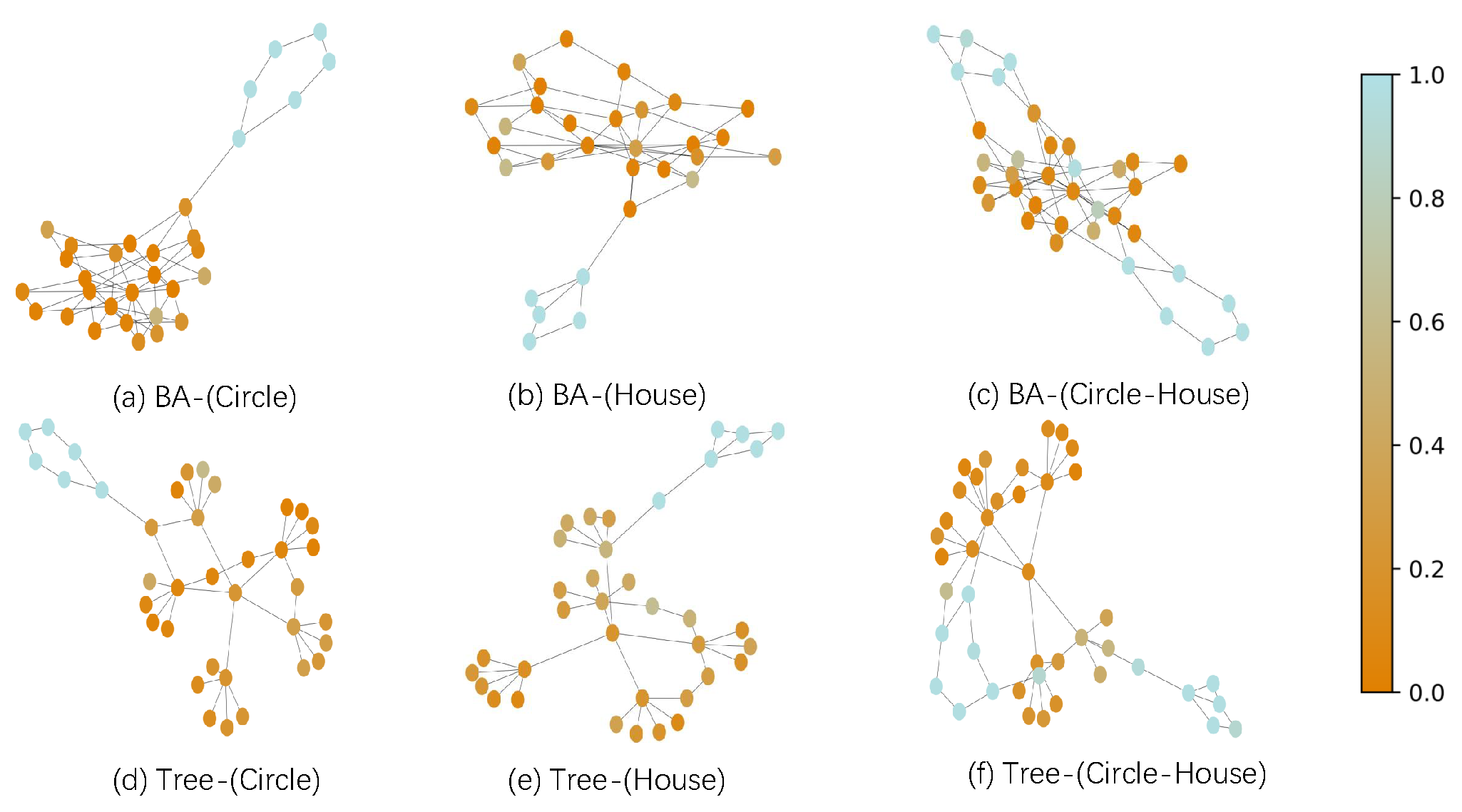

4.4. RQ1: Evaluation for Causality

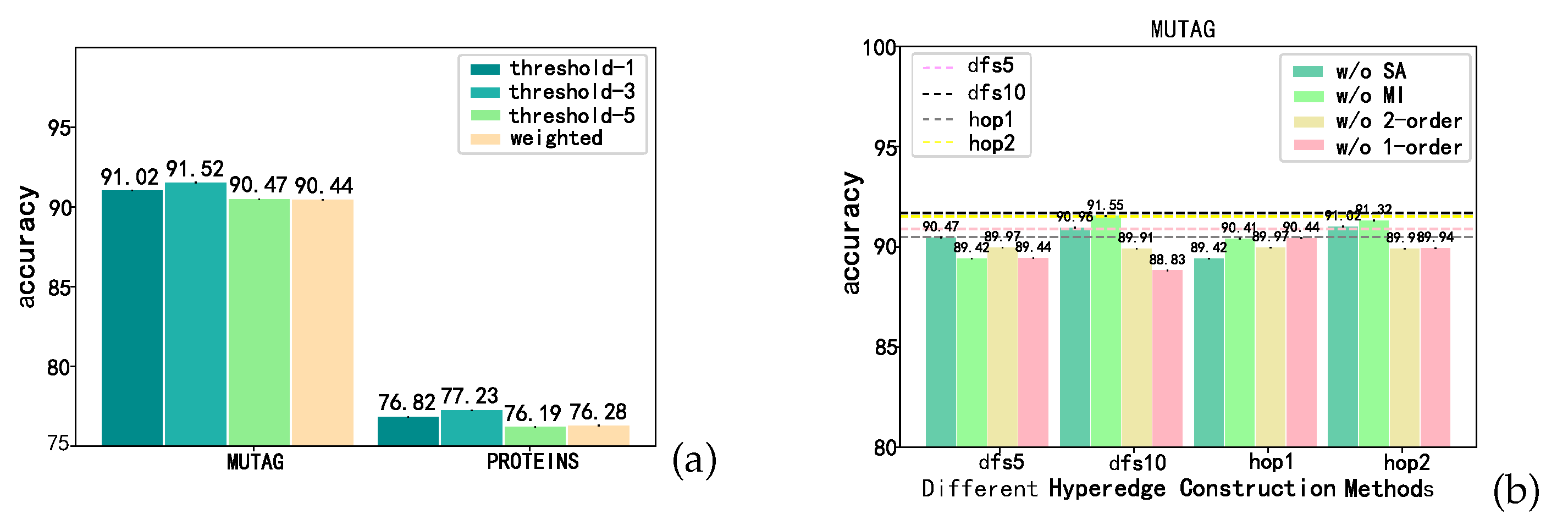

4.5. RQ2: Evaluation on 2-order Form

4.6. RQ3: Ablation Study

4.7. RQ4: Visual Interpretations

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

References

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhuang, X.; Shao, X.; Fan, X.; Chen, H. Knowledge graph-enhanced molecular contrastive learning with functional prompt. Nature Machine Intelligence, 2023, pp. 1–12.

- Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Du, H.; Jiang, D.; Kang, Y.; Li, D.; Pan, P.; Deng, Y.; Cao, D.; Hsieh, C.Y.; et al. Chemistry-intuitive explanation of graph neural networks for molecular property prediction with substructure masking. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Lu, C.; Lee, C.K. Motif-based graph self-supervised learning for molecular property prediction. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 15870–15882. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Luo, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Cai, L.; Qi, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, T.; et al. Advanced graph and sequence neural networks for molecular property prediction and drug discovery. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 2579–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shervashidze, N.; Schweitzer, P.; Van Leeuwen, E.J.; Mehlhorn, K.; Borgwardt, K.M. Weisfeiler-lehman graph kernels. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Yanardag, P.; Vishwanathan, S. Deep graph kernels. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2015, pp. 1365–1374.

- Ying, Z.; You, J.; Morris, C.; Ren, X.; Hamilton, W.; Leskovec, J. Hierarchical graph representation learning with differentiable pooling. Advances in neural information processing systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Cui, Z.; Neumann, M.; Chen, Y. An end-to-end deep learning architecture for graph classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2018, Vol. 32.

- Ma, J.; Wan, M.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Hecht, B.; Teevan, J. Learning Causal Effects on Hypergraphs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2022, pp. 1202–1212.

- Knyazev, B.; Taylor, G.W.; Amer, M. Understanding attention and generalization in graph neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; You, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, R.; Gao, Y. Hypergraph neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 3558–3565.

- Dwivedi, V.P.; Joshi, C.K.; Laurent, T.; Bengio, Y.; Bresson, X. Benchmarking graph neural networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2003.00982 2020.

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1609.02907 2016.

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Feng, F.; He, X.; Chua, T.S. Reinforced Causal Explainer for Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, A.; He, X.; Chua, T.S. Towards multi-grained explainability for graph neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 18446–18458. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, A.; He, X.; Chua, T.S. Discovering invariant rationales for graph neural networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2201.12872 2022.

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1710.10903 2017.

- Hamilton, W.; Ying, Z.; Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Courcelle, B. On the Expression of Graph Properties in some Fragments of Monadic Second-Order Logic. Descriptive complexity and finite models 1996, 31, 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Ji, S. Second-order pooling for graph neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Ji, S.; Ji, R. HGNN +: General Hypergraph Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Ahmed, C.F.; Samiullah, M.; Leung, C.K.S. Discovering Interesting Patterns from Hypergraphs. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data 2023, 18, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balalau, O.; Bonchi, F.; Chan, T.H.; Gullo, F.; Sozio, M.; Xie, H. Finding Subgraphs with Maximum Total Density and Limited Overlap in Weighted Hypergraphs. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, B. Hypergraph transformer neural networks. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data 2023, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.S. Definition of hydrogen deficiency for hydrocarbons with functional groups. Energy & fuels 2010, 24, 4097–4098. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Chu, Z.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhang, A. A survey on causal inference. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data (TKDD) 2021, 15, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H. Long-tailed classification by keeping the good and removing the bad momentum causal effect. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Qin, Y.; Qi, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, H. Deconfounded visual grounding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, Vol. 36, pp. 998–1006.

- Qi, J.; Niu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H. Two causal principles for improving visual dialog. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 10860–10869.

- Niu, Y.; Tang, K.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Z.; Hua, X.S.; Wen, J.R. Counterfactual vqa: A cause-effect look at language bias. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 12700–12710.

- Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Cai, J. Deconfounded image captioning: A causal retrospect. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J.; Hua, X.S.; Sun, Q. Causal intervention for weakly-supervised semantic segmentation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 655–666. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Feng, F.; Zhang, H.; He, X.; Zhu, F.; Chua, T.S. Learning to Imagine: Integrating Counterfactual Thinking in Neural Discrete Reasoning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2022, pp. 57–69.

- Cao, B.; Lin, H.; Han, X.; Liu, F.; Sun, L. Can Prompt Probe Pretrained Language Models? Understanding the Invisible Risks from a Causal View. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2203.12258 2022.

- Qian, C.; Feng, F.; Wen, L.; Ma, C.; Xie, P. Counterfactual inference for text classification debiasing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2021, pp. 5434–5445.

- Feder, A.; Keith, K.A.; Manzoor, E.; Pryzant, R.; Sridhar, D.; Wood-Doughty, Z.; Eisenstein, J.; Grimmer, J.; Reichart, R.; Roberts, M.E.; et al. Causal inference in natural language processing: Estimation, prediction, interpretation and beyond. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2022, 10, 1138–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, K.A.; Jensen, D.; O’Connor, B. Text and causal inference: A review of using text to remove confounding from causal estimates. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2005.00649 2020.

- Abraham, E.D.; D’Oosterlinck, K.; Feder, A.; Gat, Y.; Geiger, A.; Potts, C.; Reichart, R.; Wu, Z. CEBaB: Estimating the causal effects of real-world concepts on NLP model behavior. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 17582–17596. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Liu, G.; Wang, D.; Yu, W.; Jiang, M. Learning from counterfactual links for link prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2022; pp. 26911–26926. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Lin, M.; He, X.; Chua, T.S. Causal attention for interpretable and generalizable graph classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2022, pp. 1696–1705.

- Zhou, D.; Huang, J.; Schölkopf, B. Learning with hypergraphs: Clustering, classification, and embedding. Advances in neural information processing systems 2006, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Zhang, F.; Torr, P.H. Hypergraph convolution and hypergraph attention. Pattern Recognition 2021, 110, 107637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhang, F.; Wei, Y.; Li, Z.; Zou, C.; Gao, Y.; Dai, Q. Heterogeneous hypergraph variational autoencoder for link prediction. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, 44, 4125–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowozin, S.; Cseke, B.; Tomioka, R. f-gan: Training generative neural samplers using variational divergence minimization. Advances in neural information processing systems 2016, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Velickovic, P.; Fedus, W.; Hamilton, W.L.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y.; Hjelm, R.D. Deep graph infomax. ICLR (Poster) 2019, 2, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Interpretation and identification of causal mediation. Psychological methods 2014, 19, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearl, J.; et al. Models, reasoning and inference. Cambridge, UK: CambridgeUniversityPress 2000, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, A.K.; Lopez de Compadre, R.L.; Debnath, G.; Shusterman, A.J.; Hansch, C. Structure-activity relationship of mutagenic aromatic and heteroaromatic nitro compounds. correlation with molecular orbital energies and hydrophobicity. Journal of medicinal chemistry 1991, 34, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wale, N.; Watson, I.A.; Karypis, G. Comparison of descriptor spaces for chemical compound retrieval and classification. Knowledge and Information Systems 2008, 14, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, P.D.; Doig, A.J. Distinguishing enzyme structures from non-enzymes without alignments. Journal of molecular biology 2003, 330, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Ding, H.; Qiao, Y.; Marinovic, A.; Gu, K.; Chen, T.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W. Unsupervised inductive graph-level representation learning via graph-graph proximity. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1904.01098 2019.

- Zhang, Z.; Bu, J.; Ester, M.; Zhang, J.; Yao, C.; Yu, Z.; Wang, C. Hierarchical graph pooling with structure learning. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1911.05954 2019.

- Morris, C.; Kriege, N.M.; Bause, F.; Kersting, K.; Mutzel, P.; Neumann, M. Tudataset: A collection of benchmark datasets for learning with graphs. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2007.08663 2020.

- Ying, Z.; Bourgeois, D.; You, J.; Zitnik, M.; Leskovec, J. Gnnexplainer: Generating explanations for graph neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Barabási, A.L.; Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. science 1999, 286, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| nmi(i) Graph classification on original synthetic dataset with different bias rates b (SYN-b) | |||||

| SYN-0.1 | SYN-0.3 | Unbiased | SYN-0.7 | SYN-0.9 | |

| GCN | 95.44(↓2.61%) | 97.62(↓0.39%) | 98.00 | 96.50(↓1.53%) | 94.75(↓3.32%) |

| 94.69(↓3.26%) | 96.81(↓1.10%) | 97.88 | 97.12(↓0.78%) | 96.75(↓1.15%) | |

| 96.12(↓2.36%) | 98.19(↓0.25%) | 98.44 | 97.50(↓0.95%) | 97.50(↓0.95%) | |

| GAT | 90.31(↓5.81%) | 96.69(↑0.84%) | 95.88 | 94.62(↓1.31%) | 89.56(↓6.59%) |

| 90.94(↓3.89%) | 95.88(↑1.33%) | 94.62 | 94.12(↓0.53%) | 88.62(↓6.34%) | |

| 92.69(↓3.51%) | 97.06(↑1.04%) | 96.06 | 95.38(↓0.71%) | 92.44(↓3.77%) | |

| nmi(ii) Graph classification on synthetic compounded dataset with different bias rates b (SYN-b) | |||||

| SYN-0.1 | SYN-0.3 | Unbiased | SYN-0.7 | SYN-0.9 | |

| GCN | 92.21(↓5.02%) | 95.62(↓1.50%) | 97.08 | 97.33(↑0.26%) | 96.21(↓0.90%) |

| 90.00(↓7.85%) | 96.75(↓0.94%) | 97.67 | 97.46(↓0.22%) | 96.25(↓1.45%) | |

| 96.42(↓1.61%) | 98.17(↑0.17%) | 98.00 | 98.38(↑0.39%) | 97.12(↓0.90%) | |

| GAT | 83.75(↓12.4%) | 92.62(↓3.14%) | 95.62 | 95.54(↓0.08%) | 86.04(↓10.0%) |

| 92.29(↓3.86%) | 96.08(↑0.08%) | 96.00 | 95.42(↓0.60%) | 91.62(↓4.56%) | |

| 94.04(↓3.72%) | 96.38(↓1.32%) | 97.67 | 96.21(↓1.49%) | 95.62(↓1.09%) | |

| nmi(iii) Graph classification on synthetic separated dataset with different bias rates b (SYN-b) | |||||

| SYN-0.1 | SYN-0.3 | Unbiased | SYN-0.7 | SYN-0.9 | |

| GCN | 86.25(↓7.38%) | 91.50(↓1.74%) | 93.12 | 91.88(↓1.33%) | 83.00(↓10.9%) |

| 86.12(↓7.89%) | 90.50(↓3.21%) | 93.50 | 92.25(↓1.34%) | 84.25(↓9.89%) | |

| 90.25(↓5.97%) | 97.12(↑0.90%) | 96.25 | 95.50(↓0.78%) | 89.88(↓6.62%) | |

| GAT | 87.62(↓5.02%) | 90.88(↓1.49%) | 92.25 | 93.00(↑0.81%) | 84.75 (↓8.13%) |

| 88.00(↓8.45%) | 94.50(↓1.69%) | 96.12 | 94.75(↓1.43%) | 83.75(↓12.9%) | |

| 89.88(↓6.86%) | 95.62(↓1.02%) | 96.50 | 95.88(↓0.64%) | 85.25(↓11.7%) | |

| nmi(iv) Graph classification on synthetic biased separated dataset with a fixed rate b = 0.1 | |||||

| nmiand different bias rates (SYN-) | |||||

| SYN-0.1 | SYN-0.3 | Unbiased | SYN-0.7 | SYN-0.9 | |

| GCN | 81.82(↑0.63%) | 72.73(↓10.6%) | 81.31 | 78.48(↓3.48%) | 82.42(↑1.37%) |

| 75.76(↓5.96%) | 82.11(↑1.92%) | 80.56 | 79.39(↓1.45%) | 81.21(↑0.81%) | |

| 83.33(↓4.62%) | 83.82(↓4.06%) | 87.37 | 83.03(↓4.97%) | 83.64(↓4.23%) | |

| GAT | 79.70(↓5.49%) | 83.87(↓0.55%) | 84.33 | 82.85(↓1.76%) | 77.88(↓7.65%) |

| 79.39(↓5.61%) | 80.06(↓4.82%) | 84.11 | 83.64(↓0.56%) | 82.97(↓1.36%) | |

| 81.52(↓4.49%) | 84.75(↓0.70%) | 85.35 | 84.85(↓0.59%) | 85.15(↓0.12%) | |

| w/o Causality | MUTAG | PTC-FR | PTC-FM | SYN-sep |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hop1 | ||||

| hop2 | ||||

| w/o HNN | MUTAG | PTC-FR | PTC-FM | SYN-sep |

| hop1 | ||||

| hop2 | ||||

| OURS | 91.52 | 69.41 | 68.47 | 90.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).