Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

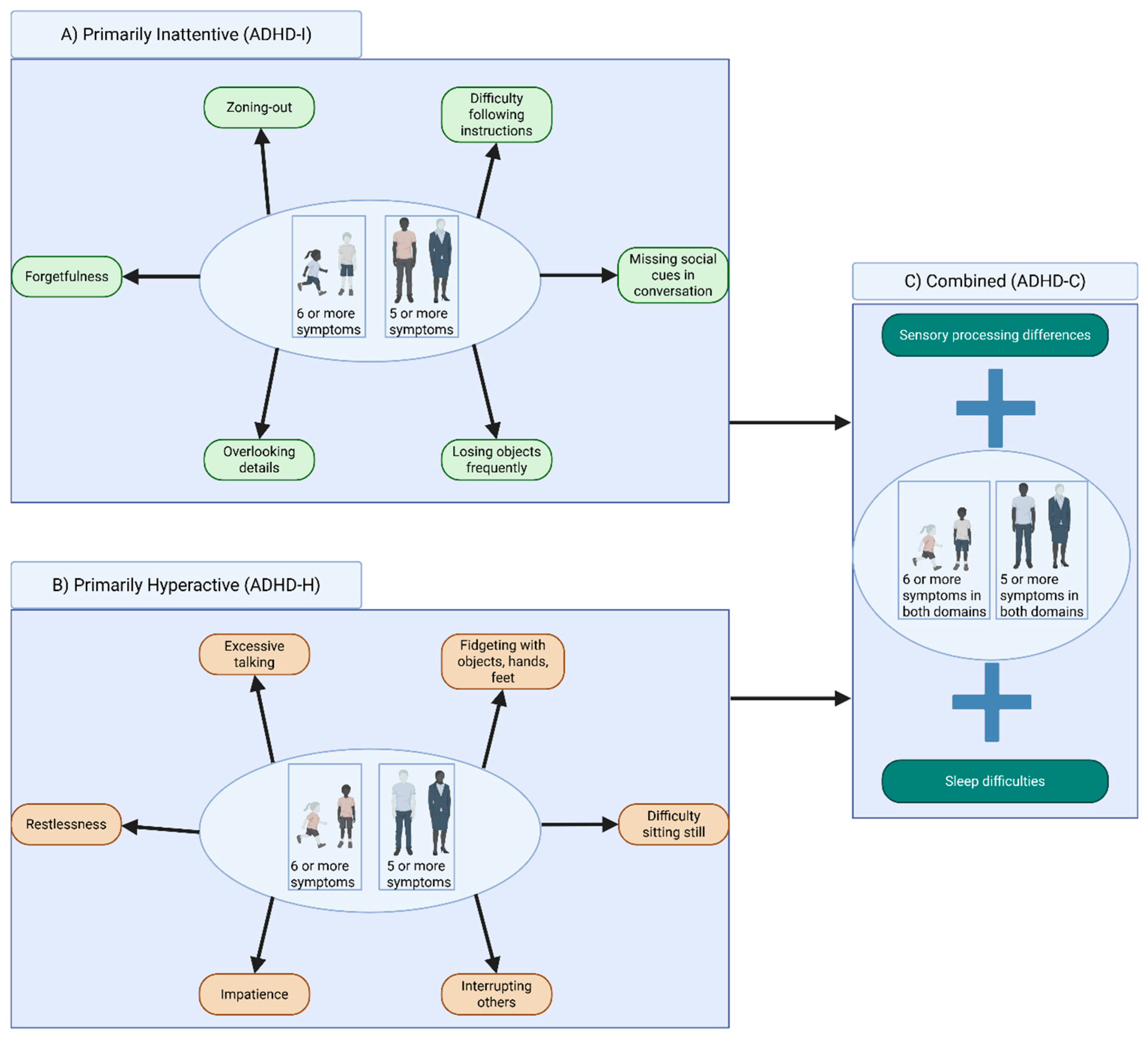

2. Diagnosing ADHD in Children and Adults: Similarities and Differences

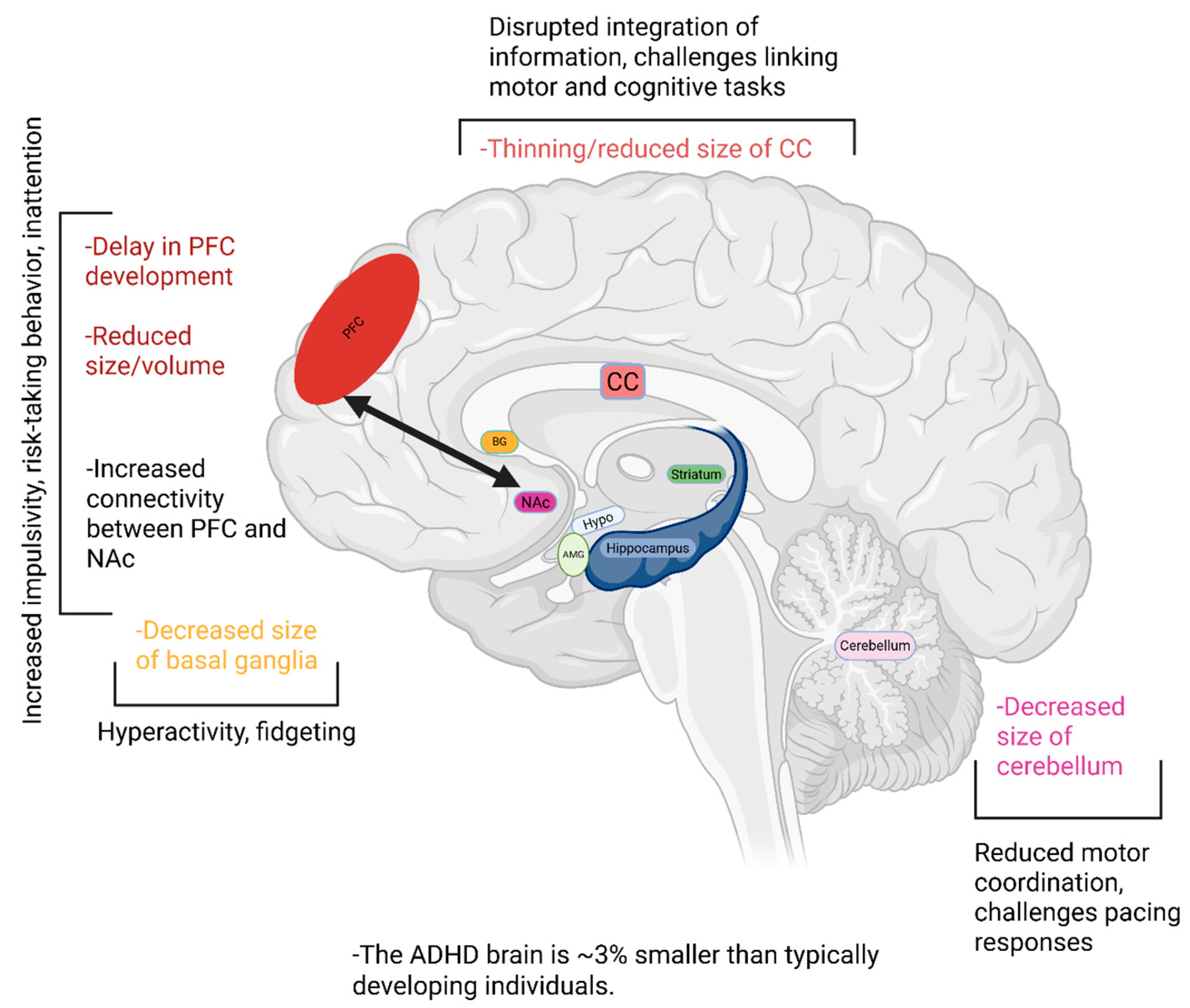

3. Brain Structural Changes Associated with ADHD

4. Neurotransmitters and ADHD

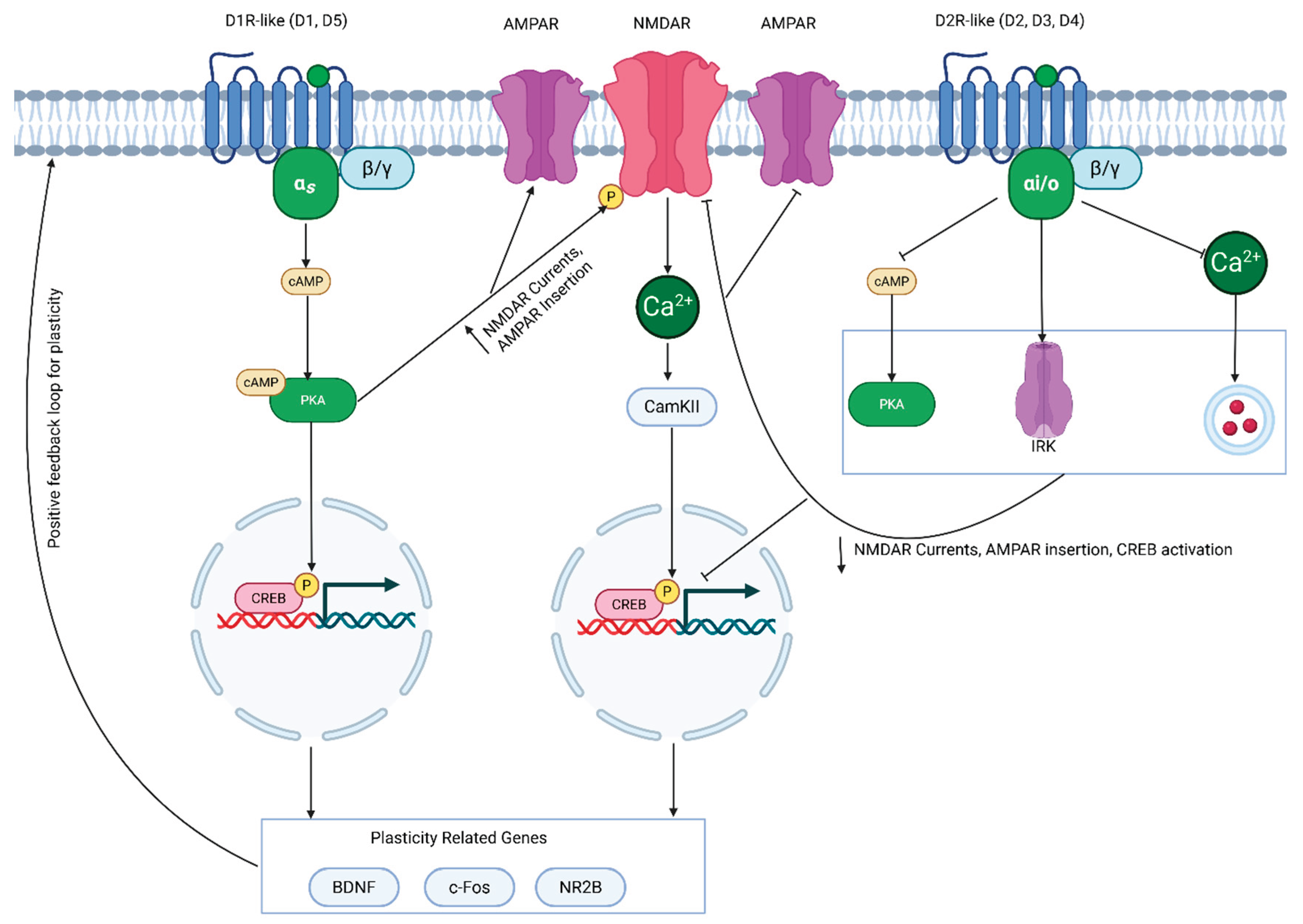

4.1. Dopaminergic Signaling in the Brain

4.2. Noradrenergic Signaling in the Brain

4.3. Serotonergic Signaling the Brain

4.4. NMDAR and Dopamine Interactions

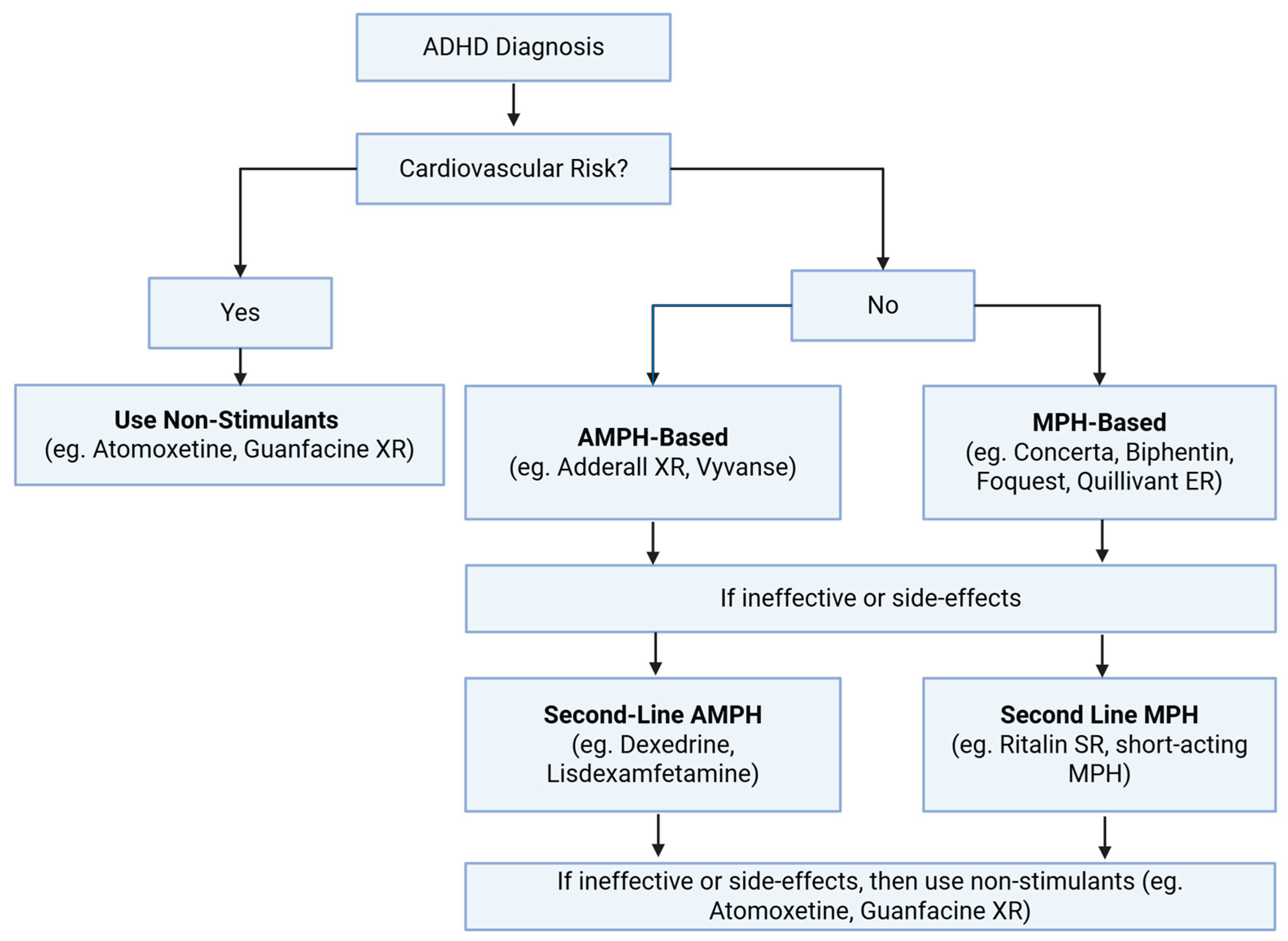

5. ADHD Medications

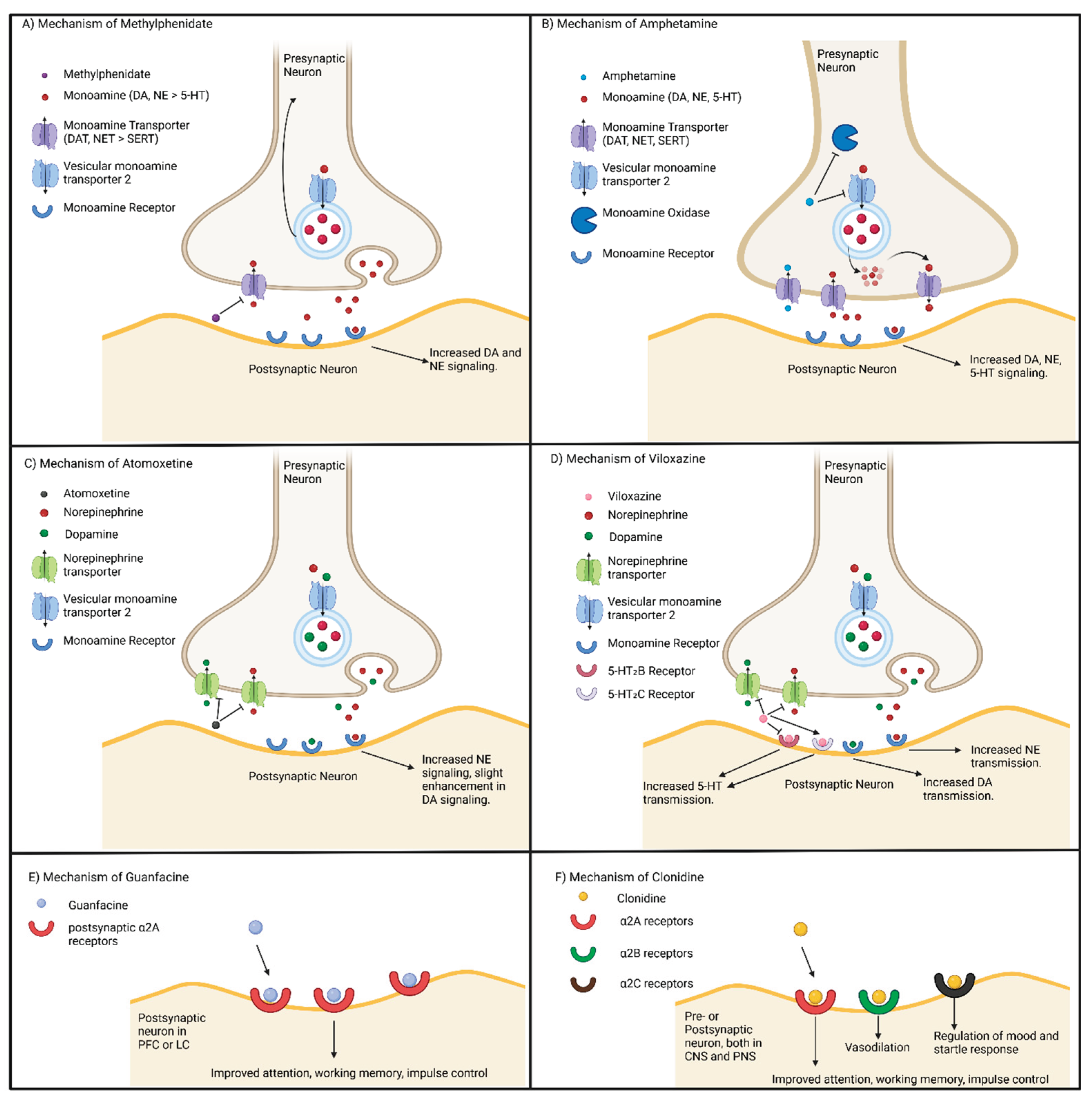

6. Modes of Actions of Various ADHD Medications

6.1. Methylphenidate Based Medications

6.2. Amphetamine Based Medications

6.3. Non-Stimulant Medications

7. Pharmacological Treatment for ADHD in Humans and Animal Models: Discrepancies and Possible Explanations

7.1. ADHD Medications Generally Improve Cognition in Humans

7.2. Amphetamine Effects on Cognition

7.3. Methylphenidate Effects on Cognition

7.4. Atomoxetine Effects on Cognition

8. Implications of In Utero Exposure to ADHD Medications for Long-Term Cognition

8.1. Prescription of ADHD Medications During Pregnancy

8.2. Continued Evidence Suggests That ADHD Medications Are Safe During Pregnancy

8.3. In Utero Exposure to AMPH: Time Dependent Changes in Metabolism and Behavior in Animal Studies

8.4. In Utero Exposure to Methylphenidate: Alterations in DA Pathways and Behavior in Animal Studies

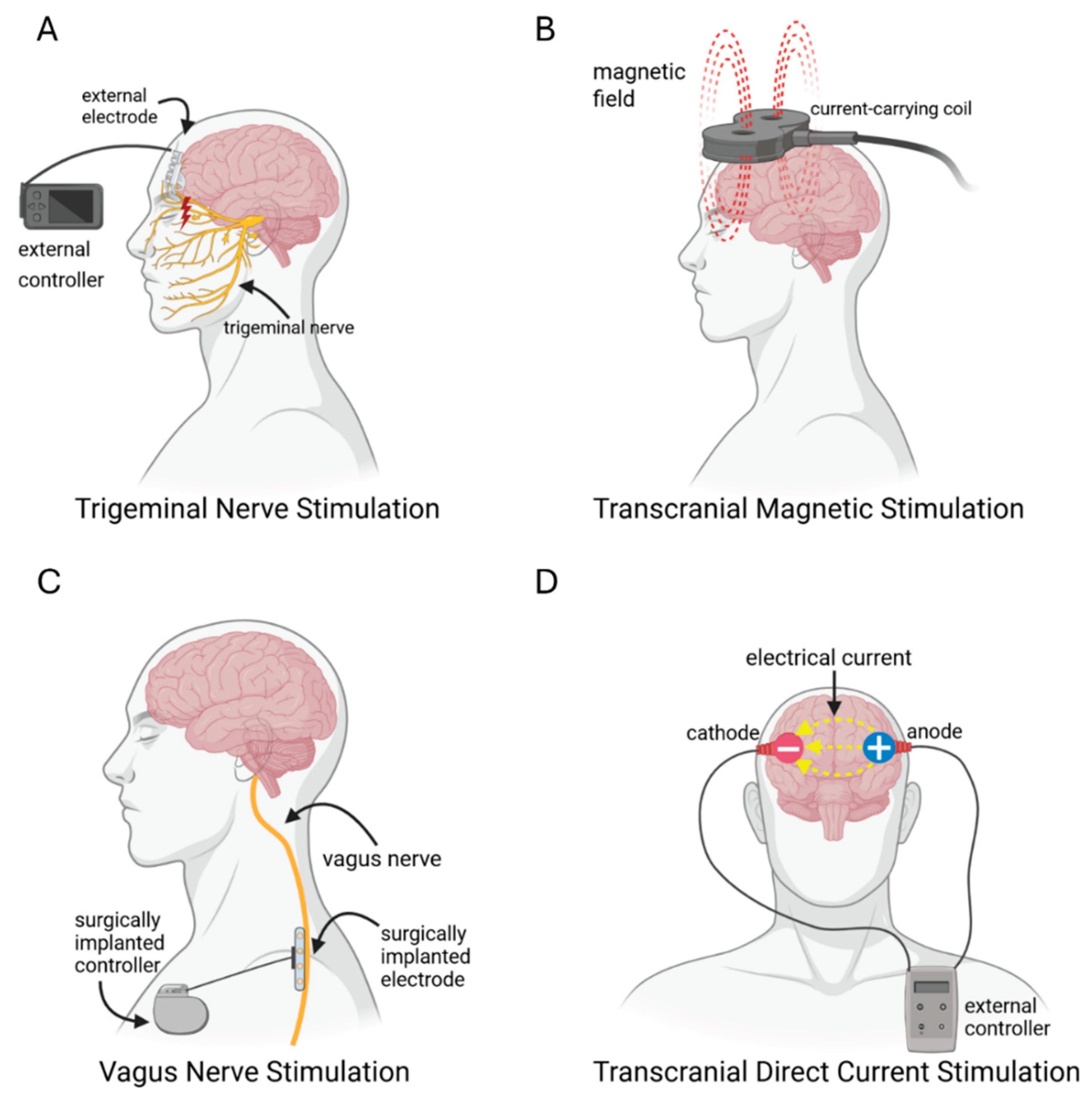

9. Transcranial Stimulation for ADHD Treatment

10. A Paradigm Shift in ADHD Research: Integrating Synaptic and Systems Level Neuroscience

10.1. Reframing ADHD Treatment: From Disorder to Divergence

10.2. Improving ADHD Diagnosis and Interpretation of Human Data

10.3. Further Longitudinal Studies Are Required to Assess the Impact In Utero Exposure to ADHD Medications on Cognition

10.4. Considerations for Animal Models and In Utero Exposure Studies

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 |

| ADHD-I | Primarily inattentive ADHD |

| ADHD-H | Primarily hyperactive ADHD |

| ADHD-C | Combined ADHD |

| PFC | Prefrontal cortex |

| TDIs | Typically developing individuals |

| NAc | Nucleus accumbens |

| CC | Corpus callosum |

| BG | Basal ganglia |

| DA | Dopamine |

| NE | Norepinephrine |

| AMPH | Amphetamine |

| MPH | Methylphenidate |

| ATX | Atomoxetine |

| 5-HT | Serotonin |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| VTA | Ventral tegmental area |

| SN | Substantia nigra |

| DS | Dorsal striatum |

| GPCRs | G-protein-coupled-receptors |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| CREB | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| SNc | Substantia nigra pars compacta |

| IRK | Inward rectifying potassium channels |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| DAT | Dopamine transporter |

| NET | Norepinephrine transporter |

| DOPA | Dihydrophenylalanine |

| DBH | Dopamine β-hydroxylase |

| LC | Locus coeruleus |

| DRn | Dorsal raphe nucleus |

| SERT | Serotonin transporter |

| NMDARs | N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors |

| AMPARs | α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic receptors |

| EPSCs | Excitatory postsynaptic potentials |

| VMAT2 | Vesicular monoamine transporter 2 |

| MAO | Monoamine oxidase |

| VWM | Visual working memory |

| SWM | Spatial working memory |

| LTP | Long term potentiation |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| rTMS | Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| tDCS | Transcranial direct current stimulation |

| dlPFC | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| VNS | Vagus nerve stimulation |

| eTNS | External trigeminal nerve stimulation |

References

- Astle DE, Bassett DS, Viding E. Understanding divergence: Placing developmental neuroscience in its dynamic context. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2024, 157, 105539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman LA, Rapoport JL. Brain development in ADHD. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2015, 30, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Rudan I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2021, 11, 04009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcutt, EG. The Prevalence of DSM-IV Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young S, Adamo N, Ásgeirsdóttir BB, Branney P, Beckett M, Colley W, et al. Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [Internet]. DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022. Available online: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Posner J, Polanczyk GV, Sonuga-Barke E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 2020, 395, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiland LS, Gildon BL. Diagnosis and Treatment of ADHD in the Pediatric Population. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2024, 29, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jangmo A, Stålhandske A, Chang Z, Chen Q, Almqvist C, Feldman I, et al. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, School Performance, and Effect of Medication. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019, 58, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyandt LL, Iwaszuk W, Fulton K, Ollerton M, Beatty N, Fouts H, et al. The Internal Restlessness Scale: Performance of College Students With and Without ADHD. J Learn Disabil 2003, 36, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel MM, von Eye A, Nigg J. Developmental differences in structure of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) between childhood and adulthood. Int J Behav Dev 2012, 36, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams OC, Prasad S, McCrary A, Jordan E, Sachdeva V, Deva S, et al. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a comprehensive review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2023, 85, 1802–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint S, Czobor P, Komlósi S, Mészáros Á, Simon V, Bitter I. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): gender- and age-related differences in neurocognition. Psychol Med 2009, 39, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning C, Summerfeldt LJ, Parker JDA. ADHD and Academic Success in University Students: The Important Role of Impaired Attention. J Atten Disord 2022, 26, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuermaier ABM, Tucha L, Butzbach M, Weisbrod M, Aschenbrenner S, Tucha O. ADHD at the workplace: ADHD symptoms, diagnostic status, and work-related functioning. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2021, 128, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann A, Fleischmann RH. Advantages of an ADHD Diagnosis in Adulthood: Evidence From Online Narratives. Qual Health Res 2012, 22, 1486–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young S, Bramham J, Gray K, Rose E. The Experience of Receiving a Diagnosis and Treatment of ADHD in Adulthood: A Qualitative Study of Clinically Referred Patients Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. J Atten Disord 2008, 11, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard-Joyal O, Gauthier B. Creativity in the Predominantly Inattentive and Combined Presentations of ADHD in Adults. J Atten Disord 2022, 26, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolte M, Trindade-Pons V, Vlaming P, Jakobi B, Franke B, Kroesbergen EH, et al. Characterizing Creative Thinking and Creative Achievements in Relation to Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 909202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten W, Tseng CC, Chiang YS, Wu CL, Chen HC. Creativity in children with ADHD: Effects of medication and comparisons with normal peers. Psychiatry Res 2020, 284, 112680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Carpio Hernández G, Serrano Selva JP. Medication and creativity in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Psicothema 2016, 28, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentall, SS. Production deficiencies in elicited language but not in the spontaneous verbalizations of hyperactive children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1988, 16, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White HA, Shah P. Creative style and achievement in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Personality and Individual Differences 2011, 50, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brod M, Pohlman B, Lasser R, Hodgkins P. Comparison of the burden of illness for adults with ADHD across seven countries: a qualitative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Lee SS, Willcutt E. Instability of the DSM-IV Subtypes of ADHD from preschool through elementary school. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005, 62, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrevel SJC, Dedding C, van Aken JA, Broerse JEW. “Do I need to become someone else?” A qualitative exploratory study into the experiences and needs of adults with ADHD. Health Expect 2016, 19, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachar RJ, Dupuis A, Arnold PD, Anagnostou E, Kelley E, Georgiades S, et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Shared or Unique Neurocognitive Profiles? Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 2023, 51, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisci G, Cardillo R, Mammarella IC. Social Functioning in Children and Adolescents with ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Cross-Disorder Comparison. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2024, 53, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Giacomo A, Craig F, Medicamento S, Gradia F, Sardella D, Costabile A, et al. Identifying Autistic-Like Symptoms in Children with ADHD: A Comparative Study Using ADOS-2. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2024, 20, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canals J, Morales-Hidalgo P, Voltas N, Hernández-Martínez C. Prevalence of comorbidity of autism and ADHD and associated characteristics in school population: EPINED study. Autism Res 2024, 17, 1276–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen SL, Kennedy TM, Joseph HM, Riston SJ, Kipp HL, Molina BSG. Real-World Changes in Adolescents’ ADHD Symptoms within the Day and across School and Non-school Days. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2020, 48, 1543–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh-Leong C, Fuller A, Brown NM. Associations Between Family and Community Protective Factors and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Outcomes Among US Children. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2020, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley MH, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Hechtman LT, Owens EB, Stehli A, et al. Defining ADHD symptom persistence in adulthood: optimizing sensitivity and specificity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017, 58, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med 2006, 36, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe CT, Bath AC, Callahan BL, Climie EA. Positive Childhood Experiences and the Indirect Relationship With Improved Emotion Regulation in Adults With ADHD Through Social Support. J Atten Disord 2024, 28, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown NM, Brown SN, Briggs RD, Germán M, Belamarich PF, Oyeku SO. Associations Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and ADHD Diagnosis and Severity. Academic Pediatrics 2017, 17, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy A, Hechtman L, Arnold LE, Sibley MH, Molina BSG, Swanson JM, et al. Childhood Factors Affecting Persistence and Desistence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms in Adulthood: Results From the MTA. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016, 55, 937–944.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Li Y, Xiao Y, Yu C, Pei Y, Cao F. Association of positive childhood experiences with flourishing among children with ADHD: A population-based study in the United States. Prev Med 2024, 179, 107824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastoras SM, Saklofske DH, Schwean VL, Climie EA. Social Support in Children With ADHD: An Exploration of Resilience. J Atten Disord 2018, 22, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atta MHR, Amin SM, Hamad NIM, Othman AA, Sayed YM, Sanad HS, et al. The Role of Perceived Social Support in the Association Between Stress and Creativity Self-Efficacy Among Adolescents With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs.

- Alfonso D, Basurto K, Guilfoyle J, VanLandingham HB, Gonzalez C, Ovsiew GP, et al. The Effect of Adverse Childhood Experiences on ADHD Symptom Reporting, Psychological Symptoms, and Cognitive Performance Among Adult Neuropsychological Referrals. J Atten Disord 2024, 28, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford SA, Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Chakrabarti B, Ruigrok A, Suckling J, et al. Brain-Charting Autism and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Reveals Distinct and Overlapping Neurobiology. Biological Psychiatry 2025, 97, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, Blumenthal J, Lerch JP, Greenstein D, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 19649–19654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw P, Lerch J, Greenstein D, Sharp W, Clasen L, Evans A, et al. Longitudinal Mapping of Cortical Thickness and Clinical Outcome in Children and Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006, 63, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emond V, Joyal C, Poissant H. Neuroanatomie structurelle et fonctionnelle du trouble déficitaire d’attention avec ou sans hyperactivité (TDAH). L’Encéphale 2009, 35, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Dias TG, Wilson VB, Bathula DR, Iyer SP, Mills KL, Thurlow BL, et al. Reward circuit connectivity relates to delay discounting in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013, 23, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, Glahn DC, Fox PM, Mackay CE, et al. Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106, 13040–13045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaher A, Leonards J, Reif A, Grimm O. Functional connectivity of the nucleus accumbens predicts clinical course in treated and non-responder adult ADHD [Internet] 2024. Available online: http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2024.01.04.24300820 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Kortz MW, Lillehei KO. Insular Cortex. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570606/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Yasumura A, Omori M, Fukuda A, Takahashi J, Yasumura Y, Nakagawa E, et al. Age-related differences in frontal lobe function in children with ADHD. Brain and Development 2019, 41, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan MA, Hinshaw S, D’Esposito M. Efficiency of the Prefrontal Cortex During Working Memory in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2007, 46, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac V, Lopez V, Escobar MJ. Can attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder be considered a form of cerebellar dysfunction? Front Neurosci 2025, 19, 1453025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyciszkiewicz A, Pawlak MA, Krawiec K. Cerebellar Volume in Children With Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Replication Study. J Child Neurol 2017, 32, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackie S, Shaw P, Lenroot R, Pierson R, Greenstein DK, Nugent TF, et al. Cerebellar Development and Clinical Outcome in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. AJP 2007, 164, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill DE, Yeo RA, Campbell RA, Hart B, Vigil J, Brooks W. Magnetic resonance imaging correlates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Neuropsychology 2003, 17, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao Q, Sun L, Gong G, Lv Y, Cao X, Shuai L, et al. The macrostructural and microstructural abnormalities of corpus callosum in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A combined morphometric and diffusion tensor MRI study. Brain Research 2010, 1310, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein A, Covington BP, Mahabadi N, Mesfin FB. Neuroanatomy, Corpus Callosum. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448209/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Dramsdahl M, Westerhausen R, Haavik J, Hugdahl K, Plessen KJ. Adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder — A diffusion-tensor imaging study of the corpus callosum. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 2012, 201, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luders E, Kurth F, Das D, Oyarce DE, Shaw ME, Sachdev P, et al. Associations between corpus callosum size and ADHD symptoms in older adults: The PATH through life study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 2016, 256, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu A, Crocetti D, Adler M, Mahone EM, Denckla MB, Miller MI, et al. Basal ganglia volume and shape in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2009, 166, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw P, De Rossi P, Watson B, Wharton A, Greenstein D, Raznahan A, et al. Mapping the Development of the Basal Ganglia in Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2014, 53, 780–789.e11. [Google Scholar]

- Pasini A, D’agati E. Pathophysiology of NSS in ADHD. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2009, 10, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, SN.; Neuroanatomy of Reward: A View from the Ventral Striatum. In: Gottfried JA, editor. Neurobiology of Sensation and Reward [Internet]. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2011. (Frontiers in Neuroscience). Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92777/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Greven CU, Bralten J, Mennes M, O’Dwyer L, Van Hulzen KJE, Rommelse N, et al. Developmentally Stable Whole-Brain Volume Reductions and Developmentally Sensitive Caudate and Putamen Volume Alterations in Those With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Their Unaffected Siblings. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney MA, Bhatt P, Hermosillo RJM, Ryabinin P, Nikolas M, Faraone SV, et al. Smaller total brain volume but not subcortical structure volume related to common genetic risk for ADHD. Psychol Med 2021, 51, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, FX. Developmental Trajectories of Brain Volume Abnormalities in Children and Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. JAMA 2002, 288, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald HJ, Kleppe R, Szigetvari PD, Haavik J. The dopamine hypothesis for ADHD: An evaluation of evidence accumulated from human studies and animal models. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1492126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, Mohr-Jensen C, Hayes AJ, Carucci S, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe SE, Knight JR, Teter CJ, Wechsler H. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction 2005, 100, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois FT, Kim JM, Mandl KD. Premarket safety and efficacy studies for ADHD medications in children. PLoS One 2014, 9, e102249. [Google Scholar]

- Besag FMC. ADHD treatment and pregnancy. Drug Saf 2014, 37, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang Y, Zou D, Li Y, Gu S, Dong J, Ma X, et al. Monoamine Neurotransmitters Control Basic Emotions and Affect Major Depressive Disorders. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus S, Mamlins E, Giesel FL, Schmitt D, Müller HW. Monoaminergic hypo- or hyperfunction in adolescent and adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? Rev Neurosci 2022, 33, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron 2010, 68, 815–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, JD. What does dopamine mean? Nat Neurosci 2018, 21, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott T, Nieder A. Dopamine and Cognitive Control in Prefrontal Cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2019, 23, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott BL, D’Ardenne K, Mukherjee P, Schweitzer JB, McClure SM. Limbic and Executive Meso- and Nigrostriatal Tracts Predict Impulsivity Differences in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2022, 7, 415–423. [Google Scholar]

- Luo SX, Huang EJ. Dopaminergic Neurons and Brain Reward Pathways. The American Journal of Pathology 2016, 186, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi-Lytle X, Sayers S, Wagner EJ. Current Review of the Function and Regulation of Tuberoinfundibular Dopamine Neurons. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein MO, Battagello DS, Cardoso AR, Hauser DN, Bittencourt JC, Correa RG. Dopamine: Functions, Signaling, and Association with Neurological Diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2019, 39, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, CP. The role of D2-autoreceptors in regulating dopamine neuron activity and transmission. Neuroscience 2014, 282, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR. The Physiology, Signaling, and Pharmacology of Dopamine Receptors. Pharmacological Reviews 2011, 63, 182–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forssberg H, Fernell E, Waters S, Waters N, Tedroff J. Altered pattern of brain dopamine synthesis in male adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Brain Funct 2006, 2, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon KA, Ryu YH, Kim YK, Namkoong K, Kim CH, Lee JD. Dopamine transporter density in the basal ganglia assessed with [123I]IPT SPET in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2003, 30, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougherty DD, Bonab AA, Spencer TJ, Rauch SL, Madras BK, Fischman AJ. Dopamine transporter density in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The Lancet 1999, 354, 2132–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludolph AG, Kassubek J, Schmeck K, Glaser C, Wunderlich A, Buck AK, et al. Dopaminergic dysfunction in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), differences between pharmacologically treated and never treated young adults: a 3,4-dihdroxy-6-[18F]fluorophenyl-l-alanine PET study. Neuroimage 2008, 41, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst M, Zametkin AJ, Matochik JA, Pascualvaca D, Jons PH, Cohen RM. High midbrain [18F]DOPA accumulation in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999, 156, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucaite A, Fernell E, Halldin C, Forssberg H, Farde L. Reduced midbrain dopamine transporter binding in male adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: association between striatal dopamine markers and motor hyperactivity. Biol Psychiatry 2005, 57, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Kollins SH, Wigal TL, Newcorn JH, Telang F, et al. Evaluating Dopamine Reward Pathway in ADHD: Clinical Implications. JAMA 2009, 302, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Newcorn JH, Kollins SH, Wigal TL, Telang F, et al. Motivation deficit in ADHD is associated with dysfunction of the dopamine reward pathway. Mol Psychiatry 2011, 16, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itagaki S, Ohnishi T, Toda W, Sato A, Matsumoto J, Ito H, et al. Reduced dopamine transporter availability in drug-naive adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. PCN Rep 2024, 3, e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber MA, Conlon MM, Stutt HR, Wendt L, Ten Eyck P, Narayanan NS. Quantifying the inverted U: A meta-analysis of prefrontal dopamine, D1 receptors, and working memory. Behav Neurosci 2022, 136, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Lopez E, Vrana KE. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase and its genetic variants in human health and disease. Journal of Neurochemistry 2020, 152, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari BA, Chokshi V, Schmidt K. Locus coeruleus-norepinephrine: basic functions and insights into Parkinson’s disease. Neural Regen Res 2020, 15, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagatsuma A, Okuyama T, Sun C, Smith LM, Abe K, Tonegawa S. Locus coeruleus input to hippocampal CA3 drives single-trial learning of a novel context. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA [Internet] 2018 Jan 9; 115(2). Available online: https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1714082115 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Roozendaal B, Hermans EJ. Norepinephrine effects on the encoding and consolidation of emotional memory: improving synergy between animal and human studies. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2017, 14, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo N, Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. The Roles of Dopamine and Noradrenaline in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biological Psychiatry 2011, 69, e145–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannestad J, Gallezot JD, Planeta-Wilson B, Lin SF, Williams WA, Van Dyck CH, et al. Clinically Relevant Doses of Methylphenidate Significantly Occupy Norepinephrine Transporters in Humans In Vivo. Biological Psychiatry 2010, 68, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanicek T, Spies M, Rami-Mark C, Savli M, Höflich A, Kranz GS, et al. The norepinephrine transporter in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder investigated with positron emission tomography. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 1340–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulke C, Rullmann M, Huang J, Luthardt J, Becker GA, Patt M, et al. Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is associated with reduced norepinephrine transporter availability in right attention networks: a (S,S)-O-[11C]methylreboxetine positron emission tomography study. Transl Psychiatry 2019, 9, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdardottir HL, Kranz GS, Rami-Mark C, James GM, Vanicek T, Gryglewski G, et al. Association of norepinephrine transporter methylation with in vivo NET expression and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms in ADHD measured with PET. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdardottir HL, Kranz GS, Rami-Mark C, James GM, Vanicek T, Gryglewski G, et al. Effects of norepinephrine transporter gene variants on NET binding in ADHD and healthy controls investigated by PET. Hum Brain Mapp 2016, 37, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang CY, Lin HY, Gau SSF. The norepinephrine transporter gene modulates intrinsic brain activity, visual memory, and visual attention in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4026–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann S, Hohm E, Treutlein J, Blomeyer D, Jennen-Steinmetz C, Schmidt MH, et al. Association of norepinephrine transporter (NET, SLC6A2) genotype with ADHD-related phenotypes: Findings of a longitudinal study from birth to adolescence. Psychiatry Research 2015, 226, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley RA, Smith KM, Fischer M, Navia B. An examination of the behavioral and neuropsychological correlates of three ADHD candidate gene polymorphisms (DRD4 7+, DBH TaqI A2, and DAT1 40 bp VNTR) in hyperactive and normal children followed to adulthood. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet.

- Smith KM, Daly M, Fischer M, Yiannoutsos CT, Bauer L, Barkley R, et al. Association of the dopamine beta hydroxylase gene with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: genetic analysis of the Milwaukee longitudinal study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet.

- Kieling C, Genro JP, Hutz MH, Rohde LA. The −1021 C/T DBH polymorphism is associated with neuropsychological performance among children and adolescents with ADHD. American J of Med Genetics Pt B.

- Bellgrove MA, Mattingley JB, Hawi Z, Mullins C, Kirley A, Gill M, et al. Impaired Temporal Resolution of Visual Attention and Dopamine Beta Hydroxylase Genotype in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biological Psychiatry 2006, 60, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watabe-Uchida M, Zhu L, Ogawa SK, Vamanrao A, Uchida N. Whole-brain mapping of direct inputs to midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron 2012, 74, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak Dorocic I, Fürth D, Xuan Y, Johansson Y, Pozzi L, Silberberg G, et al. A Whole-Brain Atlas of Inputs to Serotonergic Neurons of the Dorsal and Median Raphe Nuclei. Neuron 2014, 83, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace AA, Floresco SB, Goto Y, Lodge DJ. Regulation of firing of dopaminergic neurons and control of goal-directed behaviors. Trends Neurosci 2007, 30, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predescu E, Vaidean T, Rapciuc AM, Sipos R. Metabolomic Markers in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) among Children and Adolescents-A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenna GA, Roder-Hanna N, Leggio L, Zywiak WH, Clifford J, Edwards S, et al. Association of the 5-HTT gene-linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with psychiatric disorders: review of psychopathology and pharmacotherapy. Pharmgenomics Pers Med 2012, 5, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Vanicek T, Kutzelnigg A, Philippe C, Sigurdardottir HL, James GM, Hahn A, et al. Altered interregional molecular associations of the serotonin transporter in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder assessed with PET. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, 38, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson L, Tuominen L, Huotarinen A, Leppämäki S, Sihvola E, Helin S, et al. Serotonin transporter in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder – preliminary results from a positron emission tomography study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 2013, 212, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Cordeiro Matos S, Jego S, Adamantidis A, Séguéla P. Norepinephrine Drives Persistent Activity in Prefrontal Cortex via Synergistic α1 and α2 Adrenoceptors. Currie K, editor. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66122. [Google Scholar]

- Zaborszky, L. Sleep-wake mechanisms and basal forebrain circuitry. Front Biosci 2003, 8, d1146–d1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España RA, Berridge CW. Organization of noradrenergic efferents to arousal-related basal forebrain structures. J of Comparative Neurology 2006, 496, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez R, Mesches MH, McGaugh JL. Norepinephrine release in the amygdala in response to footshock stimulation. Neurobiol Learn Mem 1996, 66, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Castilla P, Pérez-Ortega R, Violante-Soria V, Balderas I, Bermúdez-Rattoni F. Hippocampal release of dopamine and norepinephrine encodes novel contextual information. Hippocampus 2017, 27, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley AT, Post MR, Lacefield C, Sulzer D, Miniaci MC. Norepinephrine release in the cerebellum contributes to aversive learning. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha E, Tempia F, Lippiello P, Miniaci MC. Modulation, Plasticity and Pathophysiology of the Parallel Fiber-Purkinje Cell Synapse. Front Synaptic Neurosci [Internet] 2016 Nov 3; 8. Available online: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnsyn.2016.00035/full (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Inoshita T, Hirano T. Norepinephrine Facilitates Induction of Long-term Depression through β-Adrenergic Receptor at Parallel Fiber-to-Purkinje Cell Synapses in the Flocculus. Neuroscience 2021, 462, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margules DL, Lewis MJ, Dragovich JA, Margules AS. Hypothalamic Norepinephrine: Circadian Rhythms and the Control of Feeding Behavior. Science 1972, 178, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco AM, Gambardella P, Sticchi R, D’Aponte D, De Franciscis P. Circadian rhythms of hypothalamic norepinephrine and of some circulating substances in individually housed adult rats. Physiology & Behavior 1992, 52, 1167–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenkirch C, Liu Y, Schriver BJ, Wang Q. Locus coeruleus activation enhances thalamic feature selectivity via norepinephrine regulation of intrathalamic circuit dynamics. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Af Bjerkén S, Stenmark Persson R, Barkander A, Karalija N, Pelegrina-Hidalgo N, Gerhardt GA, et al. Noradrenaline is crucial for the substantia nigra dopaminergic cell maintenance. Neurochemistry International 2019, 131, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu BM, Kim JG, Hossain A, Cron GO, Lee JH. Substantia nigra modulates breathing rate via locus coeruleus. iScience 2025, 28, 112423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, SJ. The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009, 10, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig MV, Gulledge AT. Serotonin and Prefrontal Cortex Function: Neurons, Networks, and Circuits. Mol Neurobiol 2011, 44, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargin D, Jeoung HS, Goodfellow NM, Lambe EK. Serotonin Regulation of the Prefrontal Cortex: Cognitive Relevance and the Impact of Developmental Perturbation. ACS Chem Neurosci 2019, 10, 3078–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangen A, Nakash R, Overstreet D, Yadid G. Association between depressive behavior and absence of serotonin-dopamine interaction in the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology 2001, 155, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon OJ, DiBerto JF, Mazzone CM, Sugam J, Bloodgood DW, Hardaway JA, et al. Serotonin modulates an inhibitory input to the central amygdala from the ventral periaqueductal gray. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 2194–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramani PP, Chakravarthy VS, Ravindran B, Moustafa AA. A network model of basal ganglia for understanding the roles of dopamine and serotonin in reward-punishment-risk based decision making. Front Comput Neurosci 2015, 9, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Portas CM, Bjorvatn B, Ursin R. Serotonin and the sleep/wake cycle: special emphasis on microdialysis studies. Progress in Neurobiology 2000, 60, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin MT, Tsay HJ, Su WH, Chueh FY. Changes in extracellular serotonin in rat hypothalamus affect thermoregulatory function. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 1998, 274, R1260–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, T. The role of the serotonergic system in motor control. Neuroscience Research 2018, 129, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida K, Drew MR, Mimura M, Tanaka KF. Serotonin-mediated inhibition of ventral hippocampus is required for sustained goal-directed behavior. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhot MC, Martin S, Segu L. Role of serotonin in memory impairment. Ann Med 2000, 32, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarting RKW, Thiel CM, Müller CP, Huston JP. Relationship between anxiety and serotonin in the ventral striatum. NeuroReport 1998, 9, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jocoy E, Cepeda C, Levine M, André V. NMDA and Dopamine: Diverse Mechanisms Applied to Interacting Receptor Systems. In: VanDongen A, editor. Biology of the NMDA Receptor [Internet]. CRC Press; 2008. p. 41–57. (Frontiers in Neuroscience; vol 20085482). Available online: http://www.crcnetbase.com/doi/abs/10.1201/9781420044157.ch3 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Li F, Tsien JZ. Memory and the NMDA receptors. N Engl J Med 2009, 361, 302–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela JA, Hirsch SJ, Chapman D, Leverich LS, Greene RW. D1 /D5 Modulation of Synaptic NMDA Receptor Currents. J Neurosci 2009, 29, 3109–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2019. (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines). Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493361/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Jerome D, Jerome L. Approach to diagnosis and management of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Can Fam Physician 2020, 66, 732–736. [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Hagan JF, Allan C, Chan E, Davison D, Earls M, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20192528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero J, Gutiérrez-Casares JR, Álamo C. Molecular Characterisation of the Mechanism of Action of Stimulant Drugs Lisdexamfetamine and Methylphenidate on ADHD Neurobiology: A Review. Neurol Ther 2022, 11, 1489–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calipari ES, Jones SR. Sensitized nucleus accumbens dopamine terminal responses to methylphenidate and dopamine transporter releasers after intermittent-access self-administration. Neuropharmacology 2014, 82, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grund T, Lehmann K, Bock N, Rothenberger A, Teuchert-Noodt G. Influence of methylphenidate on brain development--an update of recent animal experiments. Behav Brain Funct 2006, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatley SJ, Pan D, Chen R, Chaturvedi G, Ding YS. Affinities of methylphenidate derivatives for dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin transporters. Life Sciences 1996, 58, PL231–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens T, Sangkuhl K, Brown JT, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB summary: methylphenidate pathway, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. Pharmacogenet Genomics.

- Volz TJ, Farnsworth SJ, King JL, Riddle EL, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. Methylphenidate Administration Alters Vesicular Monoamine Transporter-2 Function in Cytoplasmic and Membrane-Associated Vesicles. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2007, 323, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz TJ, Farnsworth SJ, Rowley SD, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. Methylphenidate-induced increases in vesicular dopamine sequestration and dopamine release in the striatum: the role of muscarinic and dopamine D2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2008, 327, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle TJ, Tipton KF, Garrett NJ. Inhibition of monoamine oxidase by amphetamine and related compounds. Biochemical Pharmacology 1976, 25, 2073–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller HH, Shore PA, Clarke DE. In vivo monoamine oxidase inhibition by d-amphetamine. Biochem Pharmacol 1980, 29, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitte HH, Freissmuth M. Amphetamines, new psychoactive drugs and the monoamine transporter cycle. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015, 36, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin D, Le JK. Amphetamine. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556103/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Jones S, Kauer JA. Amphetamine depresses excitatory synaptic transmission via serotonin receptors in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci 1999, 19, 9780–9787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom MJ, Cortese S. Current Pharmacological Treatments for ADHD. In: Stanford SC, Sciberras E, editors. New Discoveries in the Behavioral Neuroscience of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 19–50. (Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences; vol. 57). Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/7854_2022_330 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Stimulant, vs.; Non-Stimulant Medications in ADHD Treatment: A Comparative Meta-Analysis Over Two Years. J Psychiatry Cogn Behav [Internet] 2023 Dec 16; 7(1). Available online: https://www.gavinpublishers.com/article/view/long-term-safety-and-efficacy-of-stimulant-vs-non-stimulant-medications-in-adhd-treatment-a-comparative-meta-analysis-over-two-years (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Carboni E, Silvagni A, Vacca C, Di Chiara G. Cumulative effect of norepinephrine and dopamine carrier blockade on extracellular dopamine increase in the nucleus accumbens shell, bed nucleus of stria terminalis and prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neurochemistry 2006, 96, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedder D, Patel H, Saadabadi A. Atomoxetine. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493234/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Swanson CJ, Perry KW, Koch-Krueger S, Katner J, Svensson KA, Bymaster FP. Effect of the attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder drug atomoxetine on extracellular concentrations of norepinephrine and dopamine in several brain regions of the rat. Neuropharmacology 2006, 50, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bymaster, F. Atomoxetine Increases Extracellular Levels of Norepinephrine and Dopamine in Prefrontal Cortex of Rat A Potential Mechanism for Efficacy in Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002, 27, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew BM, Pellegrini MV. Viloxazine. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576423/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Yu C, Garcia-Olivares J, Candler S, Schwabe S, Maletic V. New Insights into the Mechanism of Action of Viloxazine: Serotonin and Norepinephrine Modulating Properties. J Exp Pharmacol 2020, 12, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuchat EE, Bocklud BE, Kingsley K, Barham WT, Luther PM, Ahmadzadeh S, et al. The Role of Alpha-2 Agonists for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children: A Review. Neurol Int 2023, 15, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, NT. Clinical utility of guanfacine extended release in the treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015, 9, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamo C, López-Muñoz F, Sánchez-García J. Mechanism of action of guanfacine: a postsynaptic differential approach to the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (adhd). Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2016, 44, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Russell VA, Sagvolden T, Johansen EB. Animal models of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Brain Funct 2005, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainetdinov, RR. Strengths and limitations of genetic models of ADHD. ADHD Atten Def Hyp Disord 2010, 2, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim D, Yadav D, Song M. An updated review on animal models to study attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaare HL, Blöchl M, Kumral D, Uhlig M, Lemcke L, Valk SL, et al. Associations between mental health, blood pressure and the development of hypertension. Nat Commun [Internet] 2023 Apr 7; 14(1). Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-37579-6 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Gąsecki D, Kwarciany M, Nyka W, Narkiewicz K. Hypertension, brain damage and cognitive decline. Curr Hypertens Rep 2013, 15, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuemmeler BF, Østbye T, Yang C, McClernon FJ, Kollins SH. Association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and obesity and hypertension in early adulthood: a population-based study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011, 35, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi A, Jeddi S, Kashfi K. The laboratory rat: age and body weight matter. EXCLI Journal; 20, Doc1431; ISSN 1611-2156 [Internet] 2021. Available online: https://www.excli.de/index.php/excli/article/view/4072 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Maldonado KA, Alsayouri K. Physiology, Brain. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551718/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Lin, JH. Species similarities and differences in pharmacokinetics. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 1995, 23, 1008–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio Morell B, Hernández Expósito S. Differential long-term medication impact on executive function and delay aversion in ADHD. Applied Neuropsychology: Child 2019, 8, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacQueen DA, Minassian A, Kenton JA, Geyer MA, Perry W, Brigman JL, et al. Amphetamine improves mouse and human attention in the 5-choice continuous performance test. Neuropharmacology 2018, 138, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin IL, Baker GB, Mitchell PR. The effect of viloxazine hydrochloride on the transport of noradrenaline, dopamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine and γ-amino-butyric acid in rat brain tissue. Neuropharmacology 1978, 17, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn TP, Foster GA, Greenwood DT, Howe R. Effects of viloxazine, its optical isomers and its major metabolites on biogenic amine uptake mechanisms in vitro and in vivo. European Journal of Pharmacology 1978, 52, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato-Camacho FJ, López JC, Vargas JP. Enhancing spatial memory and pattern separation: Long-term effects of stimulant treatment in individuals with ADHD. Behavioural Brain Research 2024, 475, 115211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuermaier ABM, Tucha L, Koerts J, Weisbrod M, Lange KW, Aschenbrenner S, et al. Effects of methylphenidate on memory functions of adults with ADHD. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult 2017, 24, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold LE, Hodgkins P, Kahle J, Madhoo M, Kewley G. Long-Term Outcomes of ADHD: Academic Achievement and Performance. J Atten Disord 2020, 24, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehurst LN, Mednick SC. Psychostimulants may block long-term memory formation via degraded sleep in healthy adults. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 2021, 178, 107342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard ME, Gallo DA, de Wit H. Amphetamine increases errors during episodic memory retrieval. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014, 34, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer TJ, Brown A, Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N, Lomedico A, et al. Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2013, 74, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu F, Zhang W, Ji W, Zhang Y, Jiang F, Li G, et al. Stimulant medications in children with ADHD normalize the structure of brain regions associated with attention and reward. Neuropsychopharmacol 2024, 49, 1330–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walhovd KB, Amlien I, Schrantee A, Rohani DA, Groote I, Bjørnerud A, et al. Methylphenidate Effects on Cortical Thickness in Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020, 41, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos NH, Devenyi GA, Guay S, Sengupta SM, Chakravarty MM, Grizenko N, et al. Cumulative exposure to ADHD medication is inversely related to hippocampus subregional volume in children. Neuroimage Clin 2021, 31, 102695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, FM. Systematic reviews of the acute effects of amphetamine on working memory and other cognitive performances in healthy individuals, with a focus on the potential influence of personality traits. Hum Psychopharmacol 2023, 38, e2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit H, Enggasser JL, Richards JB. Acute administration of d-amphetamine decreases impulsivity in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002, 27, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz JS, Patrick KS. The Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Amphetamines Utilized in the Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 2017, 27, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barch DM, Carter CS. Amphetamine improves cognitive function in medicated individuals with schizophrenia and in healthy volunteers. Schizophrenia Research 2005, 77, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzer MZ, Griffiths RR. Triazolam-amphetamine interaction: dissociation of effects on memory versus arousal. J Psychopharmacol 2003, 17, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward AS, Kelly TH, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Effects of d-amphetamine on task performance and social behavior of humans in a residential laboratory. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 1997, 5, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willson MC, Wilman AH, Bell EC, Asghar SJ, Silverstone PH. Dextroamphetamine causes a change in regional brain activity in vivo during cognitive tasks: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of blood oxygen level-dependent response. Biological Psychiatry 2004, 56, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming K, Bigelow LB, Weinberger DR, Goldberg TE. Neuropsychological effects of amphetamine may correlate with personality characteristics. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995, 31, 357–362. [Google Scholar]

- Makris AP, Rush CR, Frederich RC, Taylor AC, Kelly TH. Behavioral and subjective effects of D-amphetamine and modafinil in healthy adults. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 2007, 15, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle MC, Yang A, De Wit H. Effect of d-amphetamine on post-error slowing in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 2012, 220, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowski L, Hendricks K, Gordon M. Test-Taking Performance of High School Students With ADHD. J Atten Disord 2015, 19, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan O, Raz S. The Relationships Among ADHD, Self-Esteem, and Test Anxiety in Young Adults. J Atten Disord 2015, 19, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools R, D’Esposito M. Inverted-U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biol Psychiatry 2011, 69, e113–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad V, Brogan E, Mulvaney C, Grainge M, Stanton W, Sayal K. How effective are drug treatments for children with ADHD at improving on-task behaviour and academic achievement in the school classroom? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013, 22, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva IP, Farah MJ. Attention, Motivation, and Study Habits in Users of Unprescribed ADHD Medication. J Atten Disord 2019, 23, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, E.; Amphetamine Increases Phosphorylation of Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase and Transcription Factors in the Rat Striatum via Group I Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology [Internet] 2002 Jun 9. Available online: https://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1016/S0893-133X (accessed on day month year).

- Mao LM, Xue B, Jin DZ, Wang JQ. Dynamic increases in AMPA receptor phosphorylation in the rat hippocampus in response to amphetamine. J Neurochem 2015, 133, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-García LE, Tendilla-Beltrán H, Vázquez-Roque RA, Jurado-Tapia EE, Díaz A, Aguilar-Alonso P, et al. Amphetamine sensitization alters hippocampal neuronal morphology and memory and learning behaviors. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4784–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram SB, Rathipriya AG, Bolla SR, Bhat A, Ray B, Mahalakshmi AM, et al. Dendritic spines: Revisiting the physiological role. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2019, 92, 161–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park YH, Kantor L, Wang KKW, Gnegy ME. Repeated, intermittent treatment with amphetamine induces neurite outgrowth in rat pheochromocytoma cells (PC12 cells). Brain Research 2002, 951, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelucci F, Gruber SHM, El Khoury A, Tonali PA, Mathé AA. Chronic amphetamine treatment reduces NGF and BDNF in the rat brain. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 17, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li MH, Underhill SM, Reed C, Phillips TJ, Amara SG, Ingram SL. Amphetamine and Methamphetamine Increase NMDAR-GluN2B Synaptic Currents in Midbrain Dopamine Neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu W, Monteggia LM, Wolf ME. Withdrawal from repeated amphetamine administration reduces NMDAR1 expression in the rat substantia nigra, nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex. Eur J of Neuroscience 1999, 11, 3167–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu W, Chen H, Xue CJ, Wolf ME. Repeated amphetamine administration alters the expression of mRNA for AMPA receptor subunits in rat nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex. Synapse 1997, 26, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao LM, Wang W, Chu XP, Zhang GC, Liu XY, Yang YJ, et al. Stability of surface NMDA receptors controls synaptic and behavioral adaptations to amphetamine. Nat Neurosci 2009, 12, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr WD, Wanta JW, Baker M, Grudnikoff E, Morgan W, Chhabra D, et al. Intentional Discontinuation of Psychostimulants Used to Treat ADHD in Youth: A Review and Analysis. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 642798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler LR, Wanat MJ, Quintana A, Sanz E, Bamford NS, Zweifel LS, et al. Balanced NMDA receptor activity in dopamine D1 receptor (D1R)- and D2R-expressing medium spiny neurons is required for amphetamine sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011, 108, 4206–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott R, Sahakian BJ, Matthews K, Bannerjea A, Rimmer J, Robbins TW. Effects of methylphenidate on spatial working memory and planning in healthy young adults. Psychopharmacology 1997, 131, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agay N, Yechiam E, Carmel Z, Levkovitz Y. Methylphenidate enhances cognitive performance in adults with poor baseline capacities regardless of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014, 34, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerness P, Fried R, Petty C, Meller B, Biederman J. Assessment of cognitive domains during treatment with OROS methylphenidate in adolescents with ADHD. Child Neuropsychology 2014, 20, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linssen AMW, Vuurman EFPM, Sambeth A, Riedel WJ. Methylphenidate produces selective enhancement of declarative memory consolidation in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012, 221, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucha O, Mecklinger L, Laufkötter R, Klein HE, Walitza S, Lange KW. Methylphenidate-induced improvements of various measures of attention in adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Neural Transm 2006, 113, 1575–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maul J, Advokat C. Stimulant medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) improve memory of emotional stimuli in ADHD-diagnosed college students. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 2013, 105, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen SL, Arvanitogiannis A, Pliakas AM, LeBlanc C, Carlezon WA. Altered responsiveness to cocaine in rats exposed to methylphenidate during development. Nat Neurosci 2002, 5, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford CA, McDougall SA, Meier TL, Collins RL, Watson JB. Repeated methylphenidate treatment induces behavioral sensitization and decreases protein kinase A and dopamine-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in the dorsal striatum. Psychopharmacology 1998, 136, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverley JA, Piekarski C, Van Waes V, Steiner H. Potentiated gene regulation by methylphenidate plus fluoxetine treatment: Long-term gene blunting (Zif268, Homer1a) and behavioral correlates. Basal Ganglia 2014, 4, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motaghinejad M, Motevalian M, Falak R, Heidari M, Sharzad M, Kalantari E. Neuroprotective effects of various doses of topiramate against methylphenidate-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in isolated rat amygdala: the possible role of CREB/BDNF signaling pathway. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2016, 123, 1463–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Miceli M, Omoloye A, Gronier B. Characterisation of methylphenidate-induced excitation in midbrain dopamine neurons, an electrophysiological study in the rat brain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2022, 112, 110406. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CL, Feng ZJ, Liu Y, Ji XH, Peng JY, Zhang XH, et al. Methylphenidate enhances NMDA-receptor response in medial prefrontal cortex via sigma-1 receptor: a novel mechanism for methylphenidate action. PLoS One 2012, 7, e51910. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BY, Li ZX, Li YW, Li JN, Liu WT, Liu XY, et al. Central Med23 deficiency leads to malformation of dentate gyrus and ADHD-like behaviors in mice. Neuropsychopharmacol [Internet] 2025 Mar 20. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-025-02088-1 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Urban KR, Li YC, Gao WJ. Treatment with a clinically-relevant dose of methylphenidate alters NMDA receptor composition and synaptic plasticity in the juvenile rat prefrontal cortex. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 2013, 101, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalloh K, Roeder N, Hamilton J, Delis F, Hadjiargyrou M, Komatsu D, et al. Chronic oral methylphenidate treatment in adolescent rats promotes dose-dependent effects on NMDA receptor binding. Life Sciences 2021, 264, 118708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Marel K, Bouet V, Meerhoff GF, Freret T, Boulouard M, Dauphin F, et al. Effects of long-term methylphenidate treatment in adolescent and adult rats on hippocampal shape, functional connectivity and adult neurogenesis. Neuroscience 2015, 309, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang CY, Gau SSF. Improving Visual Memory, Attention, and School Function with Atomoxetine in Boys with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 2012, 22, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvil CJ, Newcorn JH, Arnold LE, Duesenberg D, Emslie GJ, Quintana H, et al. Atomoxetine Alone or Combined With Fluoxetine for Treating ADHD With Comorbid Depressive or Anxiety Symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2005, 44, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller D, Donnelly C, Lopez F, Rubin R, Newcorn J, Sutton V, et al. Atomoxetine Treatment for Pediatric Patients With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder With Comorbid Anxiety Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2007, 46, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths KR, Leikauf JE, Tsang TW, Clarke S, Hermens DF, Efron D, et al. Response inhibition and emotional cognition improved by atomoxetine in children and adolescents with ADHD: The ACTION randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2018, 102, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epperson CN, Pittman B, Czarkowski KA, Bradley J, Quinlan DM, Brown TE. Impact of atomoxetine on subjective attention and memory difficulties in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopause 2011, 18, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong CGW, Van De Voorde S, Roeyers H, Raymaekers R, Allen AJ, Knijff S, et al. Differential effects of atomoxetine on executive functioning and lexical decision in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and reading disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2009, 19, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquand AF, De Simoni S, O’Daly OG, Williams SC, Mourão-Miranda J, Mehta MA. Pattern Classification of Working Memory Networks Reveals Differential Effects of Methylphenidate, Atomoxetine, and Placebo in Healthy Volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacol 2011, 36, 1237–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli F, Cattaneo A, Caffino L, Ibba M, Racagni G, Carboni E, et al. Sub-chronic exposure to atomoxetine up-regulates BDNF expression and signalling in the brain of adolescent spontaneously hypertensive rats: Comparison with methylphenidate. Pharmacological Research 2010, 62, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzavara ET, Bymaster FP, Overshiner CD, Davis RJ, Perry KW, Wolff M, et al. Procholinergic and memory enhancing properties of the selective norepinephrine uptake inhibitor atomoxetine. Mol Psychiatry 2006, 11, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piña R, Rozas C, Contreras D, Hardy P, Ugarte G, Zeise ML, et al. Atomoxetine Reestablishes Long Term Potentiation in a Mouse Model of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuroscience 2020, 439, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan PM, Plagenhoef MR, Blake DT, Terry AV. Atomoxetine improves memory and other components of executive function in young-adult rats and aged rhesus monkeys. Neuropharmacology 2019, 155, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Yang J, Lei G, Wang G, Wang Y, Sun R. Atomoxetine Increases Histamine Release and Improves Learning Deficits in an Animal Model of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat. Basic Clin Pharma Tox 2008, 102, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura H, Shimizume R, Ikegaya Y. Histamine: A Key Neuromodulator of Memory Consolidation and Retrieval. In: Yanai K, Passani MB, editors. The Functional Roles of Histamine Receptors [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 329–53. (Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences; vol. 59). Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/7854_2021_253 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Ludolph A, Udvardi P, Föhr K, Henes C, Liebau S, Dreyhaupt J, et al. Atomoxetine affects transcription/translation of the NMDA receptor and the norepinephrine transporter in the rat brain – an in vivo study. DDDT.

- Di Miceli M, Gronier B. Psychostimulants and atomoxetine alter the electrophysiological activity of prefrontal cortex neurons, interaction with catecholamine and glutamate NMDA receptors. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 2191–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joya X, Pujadas M, Falcón M, Civit E, Garcia-Algar O, Vall O, et al. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry assay for the simultaneous quantification of drugs of abuse in human placenta at 12th week of gestation. Forensic Science International 2010, 196, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li L, Sujan AC, Butwicka A, Chang Z, Cortese S, Quinn P, et al. Associations of Prescribed ADHD Medication in Pregnancy with Pregnancy-Related and Offspring Outcomes: A Systematic Review. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornoy, A. Pharmacological Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder During Pregnancy and Lactation. Pharm Res 2018, 35, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross EJ, Graham DL, Money KM, Stanwood GD. Developmental consequences of fetal exposure to drugs: what we know and what we still must learn. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer JM, Ring BJ, Witcher JW. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Atomoxetine. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 2005, 44, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister-Williams RH, Baldwin DS, Cantwell R, Easter A, Gilvarry E, Glover V, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum. J Psychopharmacol 2017, 31, 519–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker AS, Wales R, Noe O, Gaccione P, Freeman MP, Cohen LS. The Course of ADHD during Pregnancy. J Atten Disord 2022, 26, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoten O, Tabi K, Paquette V, Carrion P, Ryan D, Radonjic NV, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in pregnancy and the postpartum period. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2024, 231, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louik C, Kerr S, Kelley KE, Mitchell AA. Increasing use of ADHD medications in pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015, 24, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson KN, Ailes EC, Danielson M, Lind JN, Farr SL, Broussard CS, et al. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Medication Prescription Claims Among Privately Insured Women Aged 15–44 Years — United States, 2003–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018, 67, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang Madsen K, Robakis TK, Liu X, Momen N, Larsson H, Dreier JW, et al. In utero exposure to ADHD medication and long-term offspring outcomes. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen JM, Hernández-Díaz S, Bateman BT, Park Y, Desai RJ, Gray KJ, et al. Placental Complications Associated With Psychostimulant Use in Pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2017, 130, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang Madsen K, Larsson H, Skoglund C, Liu X, Munk-Olsen T, Bergink V, et al. In utero exposure to methylphenidate, amphetamines and atomoxetine and offspring neurodevelopmental disorders – a population-based cohort study and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry [Internet] 2025 Mar 27. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-025-02968-4 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Huybrechts KF, Bröms G, Christensen LB, Einarsdóttir K, Engeland A, Furu K, et al. Association Between Methylphenidate and Amphetamine Use in Pregnancy and Risk of Congenital Malformations: A Cohort Study From the International Pregnancy Safety Study Consortium. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladhani NNN, Shah PS, Murphy KE. Prenatal amphetamine exposure and birth outcomes: a systematic review and metaanalysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2011, 205, e1–e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson M, Jonsson B, Steneroth G, Zetterström R. Amphetamine abuse during pregnancy: environmental factors and outcome after 14-15 years. Scand J Public Health 2000, 28, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen VS, Morrison JP, Southwell MF, Foley JF, Bolon B, Elmore SA. Histology Atlas of the Developing Prenatal and Postnatal Mouse Central Nervous System, with Emphasis on Prenatal Days E7.5 to E18.5. Toxicol Pathol 2017, 45, 705–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores G, De Jesús Gómez-Villalobos M, Rodríguez-Sosa L. Prenatal Amphetamine Exposure Effects on Dopaminergic Receptors and Transporter in Postnatal Rats. Neurochem Res 2011, 36, 1740–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong S, Fayette N, Heinsbroek JA, Ford CP. Cocaine shifts dopamine D2 receptor sensitivity to gate conditioned behaviors. Neuron 2021, 109, 3421–3435.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Ding YS, Sedler M, et al. Low Level of Brain Dopamine D2 Receptors in Methamphetamine Abusers: Association With Metabolism in the Orbitofrontal Cortex. AJP 2001, 158, 2015–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigl V, Dalitz E, Kunert E, Biesold D, Leonard BE. The effect of d-amphetamine and amitriptyline administered to pregnant rats on the locomotor activity and neurotransmitters of the offspring. Psychopharmacology 1982, 77, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasello AG, Ramirez OA. Brain catecholamines metabolism in offspring of amphetamine treated rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 1978, 9, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares MA, Silva MC, Silva-Araújo A, Xavier MR, Ali SF. Effects of prenatal exposure to amphetamine in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Intl J of Devlp Neuroscience 1996, 14, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell RW, Drucker RR, Woodruff AB. The effects of prenatal injections of adrenalin chloride and d- amphetamine sulfate on subsequent emotionality and ulcer-proneness of offspring. Psychon Sci 1965, 2, 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasello AG, Ramirez OA. Open-field and Lashley III maze behaviour of the offspring of amphetamine-treated rats. Psychopharmacology 1978, 58, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasello AG, Astrada CA, Ramirez OA. Effects on the acquisition of conditioned avoidance responses and seizure threshold in the offspring of amphetamine treated gravid rats. Psychopharmacologia 1974, 40, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke T, Poquette KE, Amro Gazze SL, Carvelli L. Amphetamine Exposure during Embryogenesis Alters Expression and Function of Tyrosine Hydroxylase and the Vesicular Monoamine Transporter in Adult C. elegans. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korchynska S, Krassnitzer M, Malenczyk K, Prasad RB, Tretiakov EO, Rehman S, et al. Life-long impairment of glucose homeostasis upon prenatal exposure to psychostimulants. EMBO J 2020, 39, e100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessinger, MA. PRENATAL EXPOSURE TO AMPHETAMINES. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America 1998, 25, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepelletier FX, Tauber C, Nicolas C, Solinas M, Castelnau P, Belzung C, et al. Prenatal Exposure to Methylphenidate Affects the Dopamine System and the Reactivity to Natural Reward in Adulthood in Rats. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology [Internet] 2015 Feb;18(4). Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ijnp/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/ijnp/pyu044 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Lloyd SA, Oltean C, Pass H, Phillips B, Staton K, Robertson CL, et al. Prenatal exposure to psychostimulants increases impulsivity, compulsivity, and motivation for rewards in adult mice. Physiology & Behavior 2013, 119, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki S, Kaizaki-Mitsumoto A, Hattori N, Numazawa S. Fetal methylphenidate exposure induced ADHD-like phenotypes and decreased Drd2 and Slc6a3 expression levels in mouse offspring. Toxicology Letters 2021, 344, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadyen-Leussis MP, Lewis SP, Bond TLY, Carrey N, Brown RE. Prenatal exposure to methylphenidate hydrochloride decreases anxiety and increases exploration in mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 2004, 77, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin ED, Sledge D, Roach S, Petro A, Donerly S, Linney E. Persistent behavioral impairment caused by embryonic methylphenidate exposure in zebrafish. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 2011, 33, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priori A, Hallett M, Rothwell JC. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or transcranial direct current stimulation? Brain Stimulation 2009, 2, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood SJ, Radua J, Rubia K. Noninvasive brain stimulation in children and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2021, 46, E14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan E, Censor N, Buch ER, Sandrini M, Cohen LG. Noninvasive brain stimulation: from physiology to network dynamics and back. Nat Neurosci 2013, 16, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han Y, Wei ZY, Zhao N, Zhuang Q, Zhang H, Fang HL, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cortical excitability and therapeutic efficacy. Front Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1544816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao S, Han J, Gu Y, Wang X, Song W, Li D, et al. Reduced Prefrontal Cortex Activation in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder during Go/No-Go Task: A Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Study. Front Neurosci 2017, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Ma S, Zhang X, Gao L. ASD and ADHD: Divergent activating patterns of prefrontal cortex in executive function tasks? Journal of Psychiatric Research 2024, 172, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao P, Xing J, Cao Y, Cheng Q, Sun X, Kang Q, et al. Clinical effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with atomoxetine in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2018, 14, 3231–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy NAS, Amin GR, Khalil SA, Mahmoud DAM, Elkholy H, Shohdy M. The therapeutic role of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Egypt a randomized sham controlled clinical trial. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 2022, 29, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao P, Wang L, Cheng Q, Sun X, Kang Q, Dai L, et al. Changes in serum miRNA-let-7 level in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder treated by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or atomoxetine: An exploratory trial. Psychiatry Research 2019, 274, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Zou Z, Huang H, Zhang Y, He X, Su H, et al. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on prefrontal cortical activation in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. Front Neurol 2024, 15, 1503975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Dos Santos R, Nunes M, Peres De Souza L, Nayara De Araújo Val S, Machado Santos Á, Cristina Vieira Da Costa A, et al. Hypothesis on the potential of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to modulate neurochemical pathways and circadian rhythm in ADHD. Medical Hypotheses 2024, 189, 111411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenby C, Falcone M, Bernardo L, Wileyto EP, Rostain A, Ramsay JR, et al. Transcranial direct current brain stimulation decreases impulsivity in ADHD. Brain Stimulation 2018, 11, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soff C, Sotnikova A, Christiansen H, Becker K, Siniatchkin M. Transcranial direct current stimulation improves clinical symptoms in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Neural Transm 2017, 124, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad MA, Nejati V, Mosayebi-Samani M, Mohammadi A, Wischnewski M, Kuo MF, et al. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in ADHD: A Systematic Review of Efficacy, Safety, and Protocol-induced Electrical Field Modeling Results. Neurosci Bull 2020, 36, 1191–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachoeira CT, Leffa DT, Mittelstadt SD, Mendes LST, Brunoni AR, Pinto JV, et al. Positive effects of transcranial direct current stimulation in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - A pilot randomized controlled study. Psychiatry Res 2017, 247, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch B, Reis J, Martinowich K, Schambra HM, Ji Y, Cohen LG, et al. Direct Current Stimulation Promotes BDNF-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity: Potential Implications for Motor Learning. Neuron 2010, 66, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong HC, Zaman R. Neurostimulation in Treating ADHD. Neurostimulation in Treating ADHD. Psychiatr Danub 2019, 31 (Suppl. S3), 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi J, Zhang S, Huang M, Qin H, Xu H, Chang Q, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation as a potential therapy for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: modulation of the noradrenergic pathway in the prefrontal lobe. Front Neurosci 2024, 18, 1494272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniwattanapong D, List JJ, Ramakrishnan N, Bhatti GS, Jorge R. Effect of Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Attention and Working Memory in Neuropsychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 2022, 25, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Menachem, E. Vagus Nerve Stimulation, Side Effects, and Long-Term Safety. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology 2001, 18, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cicco V, Tramonti Fantozzi MP, Cataldo E, Barresi M, Bruschini L, Faraguna U, et al. Trigeminal, Visceral and Vestibular Inputs May Improve Cognitive Functions by Acting through the Locus Coeruleus and the Ascending Reticular Activating System: A New Hypothesis. Front Neuroanat 2017, 11, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Cook IA, Schrader LM, Degiorgio CM, Miller PR, Maremont ER, Leuchter AF. Trigeminal nerve stimulation in major depressive disorder: acute outcomes in an open pilot study. Epilepsy Behav 2013, 28, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGough JJ, Sturm A, Cowen J, Tung K, Salgari GC, Leuchter AF, et al. Double-Blind, Sham-Controlled, Pilot Study of Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019, 58, 403–411.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubia K, Johansson L, Carter B, Stringer D, Santosh P, Mehta MA, et al. The efficacy of real versus sham external Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation (eTNS) in youth with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) over 4 weeks: a protocol for a multi-centre, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, phase IIb study (ATTENS). BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 326. [Google Scholar]

- McGough JJ, Loo SK, Sturm A, Cowen J, Leuchter AF, Cook IA. An eight-week, open-trial, pilot feasibility study of trigeminal nerve stimulation in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Brain Stimul 2015, 8, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolli A, Cerciello F, Esposito C, Ricci MC, Laccone RP, Bisogni F. Universal Design for Learning for Children with ADHD. Children (Basel) 2023, 10, 1350. [Google Scholar]