1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) are a group of disorders characterized by the progressive degeneration and death of nerve cells (neurons) in the brain and spinal cord [

1]. These degenerations often result in a decline in brain function and neurological symptoms. Many NDD conditions eventually lead to dementia, which is projected to affect approximately 150 million people worldwide by 2050, imposing an economic burden of

$10 trillion [

2]. The exact causes of most neurodegenerative diseases remain unclear; however, factors such as genetic mutations, environmental toxins, viral infections, and aging contribute to the development of these conditions [

2,

3]. Symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases vary depending on the specific condition and its stage of progression. Common symptoms include: 1) cognitive decline (memory loss and confusion), 2) movement disorders (tremors, stiffness, and difficulty with coordination), 3) sensory problems (numbness, tingling), 4) muscle weakness, and 5) emotional changes (depression and anxiety) [

4].

Common neurodegenerative diseases include: 1) Alzheimer’s disease (AD), one of the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorders, which leads to memory loss, confusion, and cognitive decline due to the buildup of amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain; 2) Parkinson’s disease (PD), which impacts movement and results in tremors, rigidity, and bradykinesia (slow movements) due to the loss of dopamine in the substantia nigra; 3) Huntington’s disease (HD), a genetic condition that results in uncontrolled movements, cognitive decline, and psychiatric symptoms; 4) Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, which causes muscle weakness and paralysis from motor neuron degeneration; 5) Multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune condition that harms the myelin sheath surrounding nerve fibers, leading to neurological issues; and 6) Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD), which affects personality, behavior, and language due to degeneration in the frontal and temporal lobes [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Neurodegenerative diseases are progressive and typically worsen over time. There is currently no cure for most neurodegenerative diseases [

2]. Treatment focuses on managing symptoms, slowing progression, and improving quality. Some treatments include medications to improve movement, cognition, and mood. Other treatment modalities include physical and occupational therapy, assistive devices, and lifestyle modifications such as exercise and a healthy diet. Research on new diagnoses and treatments for neurological diseases is ongoing. Current diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease typically involves medical history and physical exam, neurological tests, imaging studies such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography Scan (CT), and genetic testing [

9,

10].

Recent advancements in sensor-based technologies have significantly improved the assessment and diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases [

9]. These innovative approaches provide non-invasive, cost-effective, and accurate alternatives to traditional diagnostic methods. Some of these sensors include electrochemical biosensors, wearable sensors, gait analysis, artificial intelligence, digital biomarkers, and other cutting-edge diagnostic devices such as handheld instruments capable of detecting ultra-low concentrations of disease markers from a single drop of blood [

9,

10]. For example, a palm-sized sensor developed by engineers at Monash University can quickly and painlessly diagnose Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases by detecting beta amyloids and tau proteins, offering instant results and enhancing accessibility to early diagnosis [

11].

This review addressed categories of innovative sensor technologies, wearable and sensor-based monitoring technologies, and AI and machine learning applications for assessing neurodegenerative diseases. It also explored remote monitoring and telemedicine integrations in diagnosing and managing neurodegenerative diseases. We discussed challenges, limitations, future directions, and research opportunities. The advancement of these innovative sensors highlights the essential role of sensor-based technologies in transforming the assessment and management of neurodegenerative diseases, paving the way for more personalized and timely interventions.

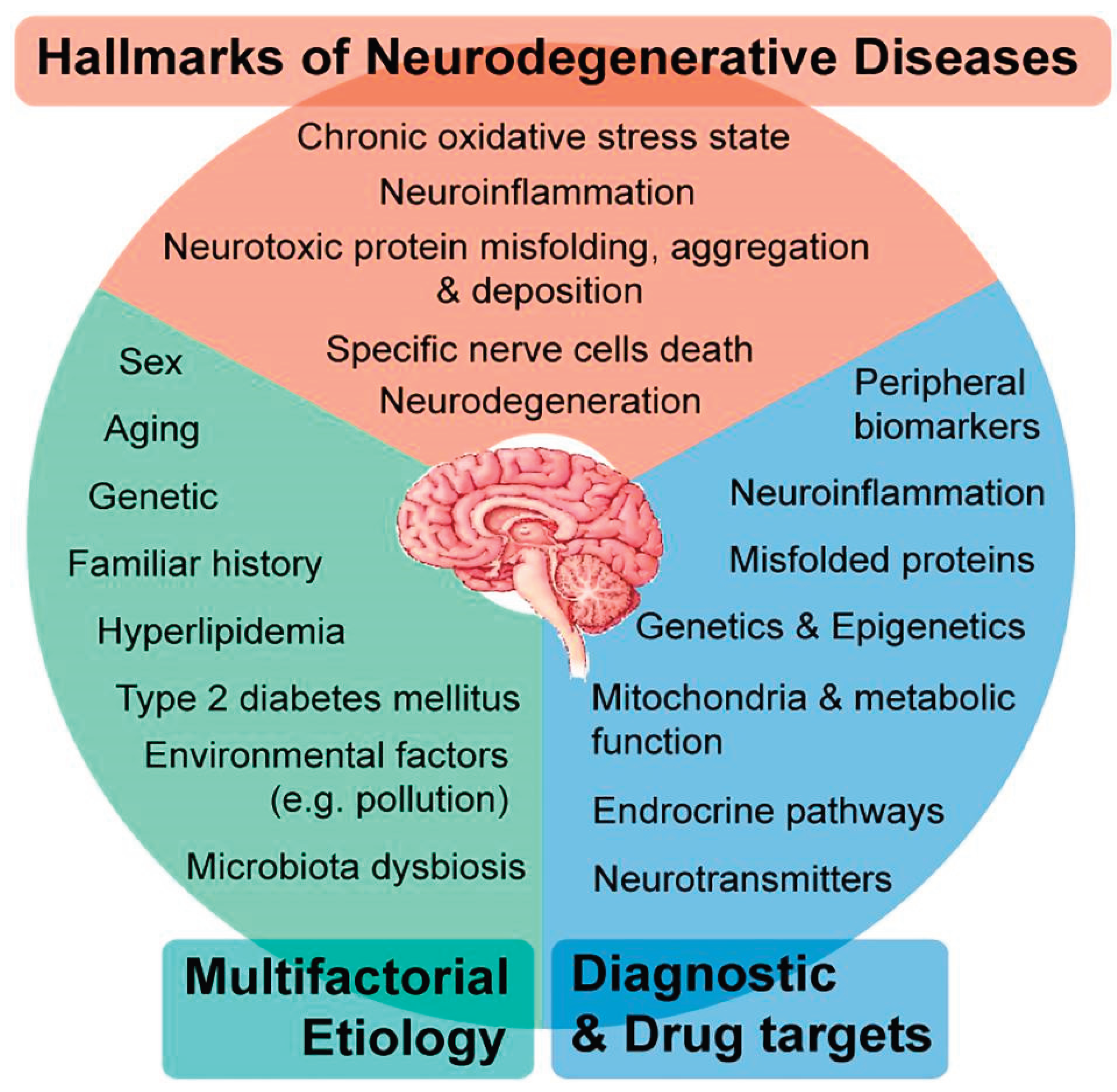

Figure 1.

Systems Biology Approaches to Understand the Host-Microbiome Interactions in Neurodegenerative Diseases/Frontiers [

1].

Figure 1.

Systems Biology Approaches to Understand the Host-Microbiome Interactions in Neurodegenerative Diseases/Frontiers [

1].

2. Categories of Innovative Technologies

Innovative technologies can be categorized into groups that introduce novelty and transformation across various sectors. They encompass broad categories with diverse applications and implications in multiple domains. One such area is Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, which relates to the evolution of algorithms and infrastructures that enable machines to perform tasks requiring intelligence similar to that of humans. These technologies serve various functions, including natural language processing, imaging, speech recognition, predictive analytics in finance and healthcare, and personalization in e-commerce. Current trends in AI include the increasing deployment of automation, the development of ethical AI frameworks, advancements in deep learning, and an emphasis on explainable AI to improve transparency [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Another vital category is Biotechnology and Health Tech, which harnesses biological processes to create solutions in healthcare and agriculture. Applications include gene editing technologies like CRISPR, personalized medicine, diagnostic tools, and biopharmaceutical development. There is a growing interest in telemedicine and wearable health technology, along with advancements in cell and gene therapies [

21,

22,

23].

The Internet of Things (IoT) refers to a network of interconnected devices that collect and share data, enhancing automation and data analytics. Its applications include smart homes, industrial IoT for predictive maintenance, smart city management, and healthcare monitoring systems. Current trends involve expanding 5G technology to support IoT applications and an increasing focus on IoT security [

27].

Blockchain and cryptocurrency represent an innovative category of technology, characterized by a decentralized ledger system for secure transactions. This includes applications in financial transactions, supply chain management, smart contracts, and identity verification. Current trends in this field involve the growth of decentralized finance (DeFi) applications and increased institutional investments in cryptocurrencies [

28,

29,

30,

31].

Robotics and automation involve machines designed to assist or replace human tasks, enhancing productivity across various sectors, including manufacturing and services [

32,

33,

34]. Key trends include advancements in collaborative robots (cobots) that work alongside humans and the increasing prevalence of remote-operated robots in hazardous environments [

35].

Renewable energy and sustainability technologies harness natural processes for clean power generation, aiming to reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Developments include solar panels, wind turbines, and biofuels, with trends focusing on improved efficiency and the mainstream adoption of electric vehicles [

36,

37,

38].

The

Advanced Materials category focuses on creating new materials with exceptional properties essential for various industrial applications [

39,

40]. Innovations in nanomaterials, smart materials, and biodegradable substances are driving advancements in this category [

41].

Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) enhance user experiences by overlaying digital information onto the real world or immersing users in virtual environments. These technologies have found applications in gaming, education, and training, with current trends highlighting the growth of AR in marketing and the development of mixed-reality platforms [

42,

43].

Quantum Computing is a cutting-edge field that utilizes quantum mechanics to process information. It can tackle complex problems much faster than classical computers [

44]. Applications range from logistics optimization to cryptography, and advancements in quantum algorithms and hardware development are shaping this field [

45].

Lastly,

3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing create objects layer by layer from digital designs, revolutionizing fabrication processes. These technologies enable rapid prototyping and customized manufacturing, fostering innovation [

46].

Together, these categories illustrate the forefront of technological advancements, driving progress and shaping the future across various disciplines. The convergence of innovative technologies, especially in Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and Biotechnology, fundamentally transforms healthcare and numerous other sectors. AI and ML enable the creation of sophisticated algorithms capable of analyzing vast amounts of medical data, predicting patient outcomes, enhancing diagnostic abilities, and personalizing treatment plans. When integrated with advancements in Biotechnology, such as gene editing and telemedicine, these technologies generate novel healthcare solutions and enhance the overall effectiveness of health interventions [

47,

48,

49].

Moreover, the rise of wearable and sensor-based monitoring technologies enhances these advancements by providing real-time health data that informs healthcare decisions. These devices utilize AI and ML to analyze biometric information, empowering individuals to manage their health proactively. As healthcare professionals gain access to detailed insights from traditional laboratory tests and continuous monitoring through wearables, the potential to improve patient care and outcomes becomes increasingly significant [

50,

51]. Integrating AI, ML, IoT, and biotechnology with wearable technologies creates a holistic, synergistic effect that promises to enhance our understanding of health, improve therapeutic strategies, and ultimately lead to better health outcomes. This comprehensive approach addresses immediate healthcare needs and paves the way for a future where technology plays a crucial role in health management and disease prevention, fostering a healthier society [

47,

50,

51,

52].

2.1. Wearable and Sensor-Based Monitoring Technologies

Wearable and sensor-based monitoring technologies are innovative devices equipped with sensors that can collect, transmit, and analyze data related to health and physical activities. These technologies have rapidly evolved and are increasingly utilized in healthcare, fitness, and personal wellness to monitor various physiological parameters in real time. Their primary aim is to empower users with actionable insights about their health, promote proactive health management, and facilitate remote patient monitoring [

53,

54,

55].

The key components of these technologies include wearable devices like fitness trackers, smartwatches, and medical wearables. Fitness trackers, such as Fitbit and Garmin, monitor physical activities, heart rate, sleep patterns, and caloric intake to encourage a more active lifestyle [

56]. Smartwatches, including the Apple Watch or Samsung Galaxy Watch, offer advanced functionalities by alerting users to notifications, providing GPS capabilities, and enabling health monitoring for metrics such as ECG and blood oxygen levels. Medical wearables are specifically designed for clinical settings and include continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and wearable ECG monitors, which assist patients in managing conditions like diabetes and heart disease [

57,

58].

Sensors play a critical role in wearable and monitoring technologies, measuring various bodily functions such as heart rate, skin temperature, respiration rate, and blood glucose levels. Many of these sensors are embedded in wearable devices. Environmental sensors are another component, monitoring external factors like UV radiation, air quality, and noise levels to inform users about the effects of their surroundings on health. Integrating wearable devices with mobile applications allows users to conveniently visualize and analyze their data, while cloud technology enables data storage and sharing with healthcare professionals. This integration yields valuable insights, assisting patients in managing chronic diseases and allowing healthcare providers to monitor patient health remotely, thereby improving outcomes and reducing hospital visits [

8,

49].

Current trends in this field include incorporating advanced data analytics and artificial intelligence (AI), which enhance the functionality of wearables by providing predictive health insights and personalized recommendations based on collected data. Innovations in sensor technology are leading to more accurate and diverse measurements, ranging from biochemical markers such as lactate to physiological parameters like hydration levels. Furthermore, there is a growing focus on user experience, with designs evolving to become more user-friendly and comfortable, ultimately encouraging regular usage [

12,

15,

61,

62].

However, challenges remain, particularly concerning data privacy and security, as the collection of personal health data raises concerns that must be addressed to build user trust and ensure compliance with regulations like HIPAA. Interoperability issues among various devices and platforms necessitate standardized protocols for seamless data exchange. Additionally, maintaining consistent user engagement with wearable technology can be challenging, as users may lose interest or find devices uncomfortable. Additionally, the accuracy and reliability of measurements from these devices are critical, as inaccuracies can lead to poor health decisions [

63].

Wearable and sensor-based monitoring technologies represent a transformative shift in health management, empowering individuals with real-time data that supports proactive decision-making. As advancements continue, these technologies have the potential to improve the quality of care significantly, encourage healthier lifestyles, and provide valuable insights for medical research. Addressing data privacy, interoperability, and user adherence challenges will be crucial for realizing their full potential in personal health and clinical settings [

64].

The advancements in wearable and sensor-based monitoring technologies are closely tied to the applications of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in monitoring neurodegenerative diseases. As these technologies provide real-time physiological and behavioral data, they generate a rich dataset that can be analyzed through AI and ML algorithms to identify patterns and early indicators of disease progression. For instance, machine learning models can process data collected from wearables that track physical activity, sleep quality, and cognitive performance, leading to personalized insights that enhance patient management. Additionally, AI-driven predictive analytics can help understand how various factors influence disease dynamics, informing treatment strategies. This integration can potentially revolutionize the landscape of neurodegenerative disease management by improving monitoring capabilities and facilitating timely interventions based on comprehensive data analysis. As the field advances, the synergy between wearable technologies and AI will likely deepen our understanding of neurodegenerative diseases and improve the quality of life for affected individuals [

65].

2.2. Emerging Sensor Technologies

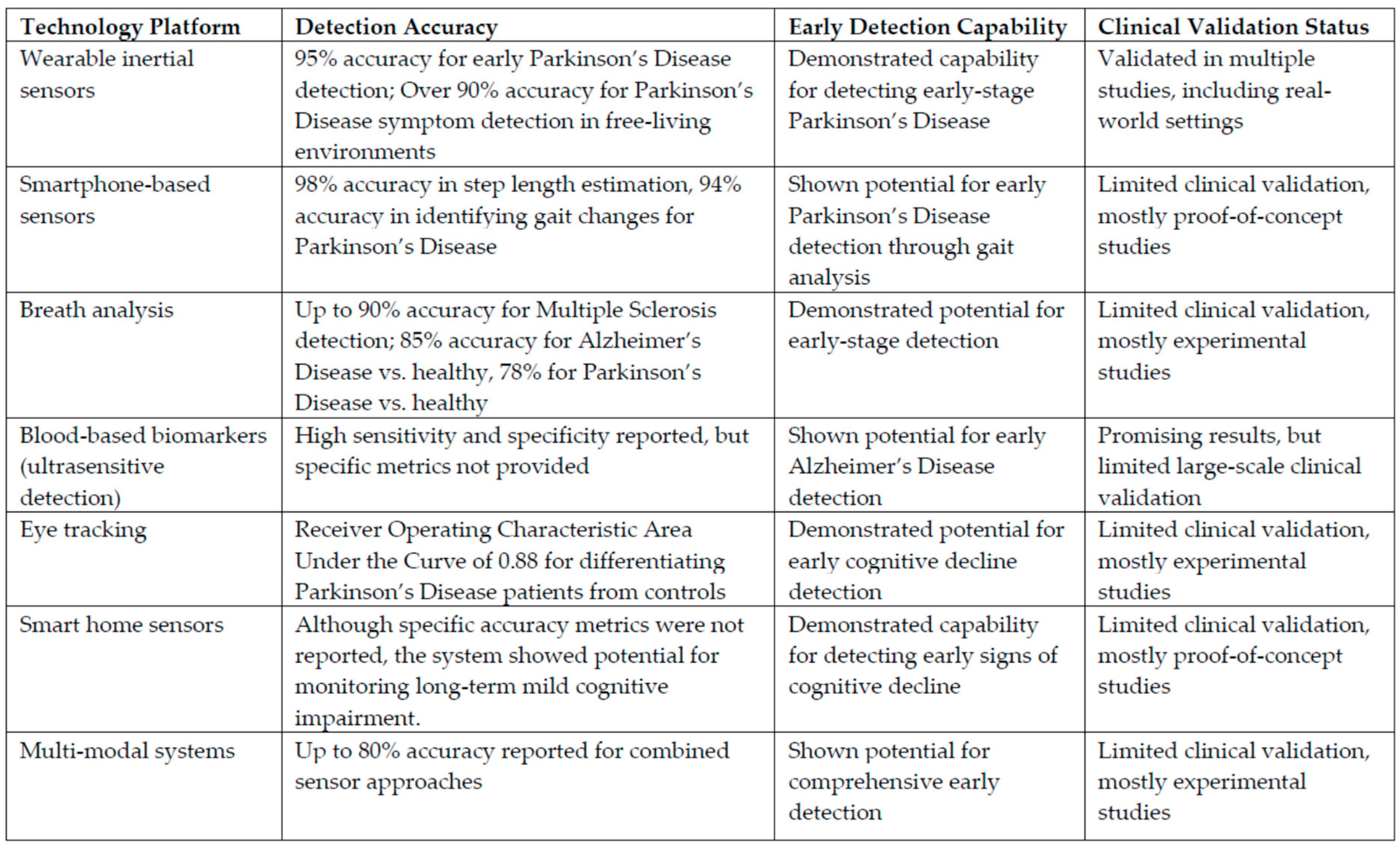

Smartphone Integrated Sensors. Smartphone-based and wearable inertial sensors are significant for the early diagnosis and monitoring of neurodegenerative diseases. A series of studies indicate that smartphone-integrated sensors can estimate step length with 98% accuracy and detect gait changes with 94% accuracy. Meanwhile, consumer wearable devices achieved 92.3% accuracy in screening early Parkinson’s cases. Wearable inertial sensors, tested in everyday environments, reported over 90% accuracy, with one study highlighting 95% accuracy in distinguishing early, untreated Parkinson’s Disease. Digital biomarkers offer additional promise: eye-tracking methods, for example, yielded a receiver operating characteristic AUC of 0.88 in separating Parkinson’s patients from healthy controls, and breath analysis sensors reached up to 90% accuracy in classifying Multiple Sclerosis and Alzheimer’s Disease cases [

66,

67].

Wearable devices are categorized as follows: 1) Focus on motor symptoms. Wearable sensors, particularly inertial measurement units that combine accelerometers, gyroscopes, and sometimes magnetometers, show significant promise in monitoring motor symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases; 2)Versatility, where studies have explored various sensor placements (wrist, lower back, ankles) to capture different aspects of movement and gait; 3) Accuracy, with reports indicating over 90% accuracy in detecting Parkinson’s Disease symptoms using inertial sensors in free-living environments; and 3) Early-stage detection, combining wearable sensors with machine learning to differentiate between early-stage Parkinson’s Disease patients and healthy controls. However, some challenges have been noted regarding user acceptance, battery life, and data interpretation for clinical use, which remain areas for improvement.

Multi-modal monitoring systems combine data from smart home sensors, video, audio, and other sources to capture motor and cognitive symptoms. However, their specific performance metrics, with up to 80% accuracy, and integration into clinical workflows vary. These studies suggest that among innovative technologies, wearable inertial sensors, smartphone-based functions, and selected digital biomarker approaches offer the most promising results for the early detection and ongoing monitoring of neurodegenerative diseases. Smartphone-integrated sensors have several potential uses, including continuous monitoring. Smartphone-based technologies show promise for tracking neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Parkinson’s disease, in real-world environments. Comprehensive assessments can measure various aspects of Parkinson’s disease and dementia, such as voice, balance, gait, and cognitive function. A 98% accuracy has been reported in step length estimation and 94% accuracy in identifying changes in walking patterns using smartphone accelerometers [

67]. For early detection, a 92.3% accuracy was found in screening for the early stages of Parkinson’s disease using consumer-grade wearable devices and sensors, likely including smartphones [

66]. Multi-modal monitoring systems function in several ways: 1) Comprehensive assessment—multiple studies explored combining various sensor types or data sources for a more holistic evaluation of disease progression; 2) Diverse technologies—examples include combinations of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Electroencephalography, smart home sensors, video monitoring, audio analysis, and accelerometers; and 3) Cognitive and motor symptoms—these approaches aim to capture both cognitive and motor symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases. However, challenges remain with using these multi-modal monitoring systems, including data integration, interpretation, and practical implementation in clinical settings, which present significant hurdles for these systems.

2.3. Digital Biomarker

Innovation Movement Analysis—Key focus areas include movement analysis, which has emerged as a central area for developing digital biomarkers, especially for Parkinson’s Disease. Some reasons supporting this include: 1) high accuracy-reported 95% accuracy in distinguishing early, untreated Parkinson’s Disease patients from healthy subjects using wearable sensors; 2) symptom detection demonstrated high accuracy in identifying Parkinson’s disease symptoms such as tremors (sensitivity 99.3%, specificity 99.6%) using inertial sensors; and 3) gait analysis parameters like step length, gait velocity, and gait variability show promise as sensitive indicators of disease progression. Like other digital biomarkers, challenges remain in standardizing measurement protocols and interpreting large amounts of significant continuous monitoring data [

70].

Voice and Speech Patterns. The voice and speech patterns serve several functions: 1) early indicators—changes in speech, such as reduced volume, altered pitch, and rhythm disturbances, may act as early indicators of Parkinson’s Disease; 2) non-invasive monitoring—speech analysis provides the advantages of being non-invasive, potentially remote, and suitable for frequent or continuous monitoring; and 3) comprehensive assessment- This approach can capture both motor symptoms (e.g., changes in articulation) and cognitive aspects (e.g., language processing) of neurodegenerative diseases. There have been some research gaps in this area. For example, the studies we reviewed did not provide detailed performance metrics for voice-based biomarkers, indicating a need for further research to validate their accuracy and reliability in clinical settings.

2.4. Cognitive Function Markers

Cognitive function markers have many potential applications, encompassing various approaches: Digital biomarkers for cognitive function range from smartphone-based cognitive tests to more complex setups involving eye tracking and facial expression analysis. Additionally, some promising results reported high accuracy (Receiver Operating Characteristic Area Under the Curve of 0.88) in differentiating Parkinson’s Disease patients from healthy controls using eye-tracking methods [

72]. Smart home sensors show potential for long-term, ecologically valid assessment of cognitive function in real-world settings. However, challenges remain with standardizing assessment protocols and interpreting results across different technological platforms and patient populations, which are significant hurdles.

2.5. AI and Machine Learning Applications in Neurodegenerative Disease Monitoring

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are increasingly playing crucial roles in monitoring and managing neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s disease. These conditions are characterized by progressive nervous system degeneration, leading to cognitive decline, motor deficits, and other symptoms affecting quality of life. Given the complexities of understanding these diseases, AI and ML present innovative solutions that enhance monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment customization [

54,

55,

65,

73].

Real-Time Data Collection- Wearable and sensor-based technologies have revolutionized patient data collection in neurodegenerative disease management. Smartwatches, fitness trackers, and specialized medical wearables continuously monitor physiological parameters, including heart rate, movement patterns, sleep quality, and cognitive tasks. This real-time data collection provides a comprehensive view of a patient’s health status, enabling more effective monitoring of disease progression and response to treatment [

57,

74]

Pattern Recognition and Predictive Analytics—AI and ML algorithms excel at processing and analyzing large datasets to identify patterns that may not be noticeable to clinicians. Using extensive data collected from wearables, machine learning models can detect subtle changes in a patient’s behavior or physiology that indicate disease progression. For example, algorithms can analyze gait patterns using data from wearable sensors, providing insights into motor function deterioration in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Predictive analytics can also produce risk scores for disease progression, enabling healthcare providers to anticipate patient needs and proactively tailor interventions [

75].

Personalized Treatment Plans- The application of AI and ML in neurodegenerative disease monitoring supports the development of personalized treatment plans. By integrating patient data with clinical outcomes, machine learning models can help clinicians identify which therapies are most effective for individual patients based on their specific profiles. This personalization is crucial in neurodegenerative diseases, as treatment responses can vary significantly among patients [

76].

2.6. Remote Patient Monitoring and Telemedicine Integration

The rise of telehealth, driven by AI and machine learning, enables remote patient monitoring and improves access to healthcare services for individuals with mobility challenges or those living in remote areas. AI-powered platforms can automatically analyze data from wearables and notify healthcare providers if a patient’s health worsens, ensuring timely interventions. This proactive strategy reduces hospital visits and enhances the quality of care [

77].

Early Detection and Intervention—One of the most significant advantages of AI and ML applications in monitoring neurodegenerative diseases is their potential for early detection. Machine learning algorithms can analyze patient data trends to identify early signs of cognitive decline or motor dysfunction, often before they become clinically apparent. Early intervention can significantly alter disease trajectories, providing opportunities for more effective management and improving long-term outcomes [

78].

2.7. Clinical Implementation Progress

Validation Outcomes. Several studies have reported high accuracy rates in distinguishing patients with neurodegenerative diseases from healthy controls. An accuracy of 92.3%, a sensitivity of 90.0%, and a specificity of 100% for Parkinson’s Disease screening using wearable sensors [

66] was found to be 95% accurate in differentiating early, untreated Parkinson’s Disease patients from healthy subjects [

70]. Breath analysis has been used to differentiate between multiple sclerosis patients and controls with up to 90% accuracy [

81]. Additionally, accuracy rates include 85% for Alzheimer’s Disease compared to healthy subjects, 78% for Parkinson’s Disease versus healthy subjects, and 84% for Alzheimer’s Disease versus Parkinson’s Disease through breath analysis [

82]. However, limitations exist, as many studies had small sample sizes or lacked rigorous validation methods, which restricts the generalizability of these results. Furthermore, performance metrics and methodologies varied widely across studies, making direct comparisons challenging.

2.8. Real-World Applications

Several studies have explored the potential of home-based monitoring technologies for real-world applications, especially in home-based or continuous monitoring settings. Smartphone platforms have demonstrated the feasibility of using a smartphone-based platform for remote monitoring of Parkinson’s Disease and dementia symptoms in daily life.[

83]. Additionally, smart home sensors have shown their capability for long-term, unobtrusive monitoring of cognitive decline in real-world situations.[

84]. Wearable sensors accurately detect Parkinson’s Disease symptoms using inertial sensors in free-living environments [

68].

Potential benefits include real-world applications, which offer the potential for more ecologically valid assessments and continuous monitoring, which could provide clinicians with more comprehensive and timely information about disease progression. However, challenges can include user acceptance, data privacy, and integration with existing clinical workflows, which remain significant hurdles.

2.9. Integration Challenges

Many challenges involve data interpretation, particularly the processing and understanding of extensive information from continuous monitoring technologies, which present significant obstacles. Another challenge relates to advanced analysis techniques, emphasizing the need for sophisticated methods like deep learning to effectively process and interpret sensor data for assessing Parkinson’s Disease and other NDDs [

85]. Additionally, a lack of standardization exists. The wide variety of technologies, measurement protocols, and performance metrics used across studies complicates result comparisons and the establishment of clinical guidelines. Furthermore, user acceptance remains a concern. Long-term adherence to monitoring protocols is crucial, especially for wearable devices and home-based monitoring systems. Clinical workflow integration: Ensuring that the data generated by these technologies is actionable and meaningful in clinical contexts is crucial for their successful implementation.

Table 1.

Table of Technology platforms, detection accuracy, early detection capabilities, and clinical validation status.

Table 1.

Table of Technology platforms, detection accuracy, early detection capabilities, and clinical validation status.

3. Challenges and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is poised to transform our understanding, detection, and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, offering significant advancements in medical diagnosis, disease detection, progression modeling, and personalized treatment recommendations. Real-world case studies illustrate AI’s transformative potential in clinical settings; however, its integration presents challenges, including data privacy concerns, the necessity for model interpretability, potential biases, and technological limitations.

Overcoming these obstacles requires a joint effort from AI researchers, healthcare providers, and policymakers to ensure that AI is used ethically and securely in this field. Despite these difficulties, integrating AI and machine learning into monitoring neurodegenerative diseases offers great promise. Continuous advancements in wearable tech, data analytics, and cross-disciplinary collaboration will fuel innovation, improve patient management, and ultimately enhance the quality of life for people with these debilitating conditions. The main aim is to seamlessly combine technology and clinical care to empower patients and healthcare providers in the fight against neurodegenerative diseases, improving patient care and results through better diagnostic accuracy and a deeper understanding of disease progression.

4. Conclusions

The article “Innovative Sensor-Based Approaches for Assessing Neurodegenerative Diseases: a Brief State-of-the-Art Review” provides an overview of recent advancements in sensor technologies aimed at improving the diagnosis and monitoring of neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and others.

Integrating advanced sensor technologies, nanomaterial-based biosensors, and artificial intelligence drives a significant evolution in the clinical assessment and management of neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs). These innovations facilitate transitioning from traditional symptom-based diagnostics to objective, continuous, and biomarker-informed monitoring, improving diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. Wearable and implantable sensor systems and non-invasive biosensing platforms like graphene-based field-effect transistors provide unprecedented opportunities to detect early pathophysiological changes before obvious clinical symptoms appear. Meanwhile, AI-driven analytics enhance the interpretation of high-dimensional sensor data, enabling nuanced phenotypic classification, progression modeling, and personalized therapeutic decision-making.

From a clinical perspective, these technologies enhance the transition to precision medicine by enabling early intervention strategies, real-time treatment monitoring, and more detailed patient stratification in practical and research settings. Academically, they create new opportunities to investigate the biological foundations of neurodegeneration through multimodal, longitudinal data collection and analysis. However, effectively implementing these tools in standard clinical environments necessitates addressing challenges related to validation, standardization, data interoperability, and ethical considerations surrounding data use and patient privacy. Interdisciplinary collaboration among neuroscience, engineering, clinical medicine, and data science is essential for translating these promising advancements into scalable and clinically impactful solutions. In summary, sensor-based technologies are considered adjunct tools and essential components of a next-generation framework for diagnosing, monitoring, and understanding neurodegenerative disorders.

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed to the conceptualization, drafting, and reviewing/editing of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the 2024 Texas A&M Engineering Experiment Station Annual Research Conference (TARC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviations |

Meaning |

| NDDS |

Neurogenerative disease |

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| PD |

Parkinson’s disease |

| HD |

Huntington’s disease |

| ALS |

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| MS |

Multiple Sclerosis |

| FTD |

Frontotemporal dementia |

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| LoT |

The internet of things |

| DeFi |

Decentralized finance |

| AR |

Augmented reality |

| VR |

Virtual reality |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| GSP |

Global positioning system |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| CGMs |

Glucose monitors |

| HIPAA |

Health insurance portability and accountability act |

| AUC |

Area under the curve |

References

- Wilson, D.M.; Cookson, M.R.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Zetterberg, H.; Holtzman, D.M.; Dewachter, I. Hallmarks of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cell Press. 2023, 186, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, S. Advancing Cell Therapy for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cell Stem Cell. 2023, 30, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Voigtlaender, S.; Pawelczyk, J.; Geiger, M.; Vaios, E.J.; Karschnia, P.; Cudkowicz, M.; Dietrich, J.; Haraldsen, I.R.J.H.; Feigin, V.; Owolabi, M.; White, T.L.; Świeboda, P.; Farahany, N.; Natarajan, V.; Winter, S.F. Artificial Intelligence in Neurology: Opportunities, Challenges, and Policy Implications. J Neurol. 2024, 271, 2258–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkkinen, M.G.; Kim, M.O.; Geschwind, M.D. Clinical Neurology and Epidemiology of the Major Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018, 10, a033118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lamptey, R.N.L.; Chaulagain, B.; Trivedi, R.; Gothwal, A.; Layek, B.; Singh, J. A review of the common neurodegenerative disorders: current therapeutic approaches and the potential role of nanotherapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martin, J.B. Molecular Basis of the Neurodegenerative Disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hague, S.M.; Klaffke, S.; Bandmann, O. Neurodegenerative disorders: Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005, 76, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harding, B.N.; Kariya, S.; Monani, U.R.; Chung, W.K.; Benton, M.; Yum, S.W.; Tennekoon, G.; Finkel, R.S. Spectrum of neuropathophysiology in spinal muscular atrophy type I. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015, 74, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, H.; Cao, J.; Xie, J.; Liao, W.H.; Lei, Y.; Cao, H.; Qu, Q.; Bowen, C. Wearable sensors and features for diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Digit Health. 2023, 9, 20552076231173569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Palanisamy, C.P.; Pei, J.; Alugoju, P.; Anthikapalli, N.V.A.; Jayaraman, S.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Gopathy, S.; Roy, J.R.; Janaki, C.S.; Thalamati, D.; Mironescu, M.; Luo, Q.; Miao, Y.; Chai, Y.; Long, Q. New strategies of Neurodegenerative Disease Treatment with Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). Theranostics. 2023, 13, 4138–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trinh, N.; Bhuskute, K. R.; Varghese, N. R.; Buchanan, J. A.; Xu, Y.; McCutcheon, F. M.; Medcalf, R. L.; Jolliffe, K. A.; Sunde, M.; New, E. J.; Kaur, A. A Coumarin-Based Array for the Discrimination of Amyloids. ACS sensors 9, 615–621. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rane, N.; Choudhary, S.; Rane, J. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Business Intelligence, Finance, and E-Commerce: A Review. Finance and E-Commerce: A Review 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P. K. Digital Transformation in Supply Chain Management: Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) as Catalysts for Value Creation. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 2023, 12, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A. K. P. Chahal. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms. In Challenges and Applications for Implementing Machine Learning in Computer Vision; IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2020; pp. 188–219. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, O.; Short, B. L.; Chalup, S. K.; Wilson R., L. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) based Decision Support Systems in Mental Health: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 2023, 32, 966–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, V. Enhancing Transparency and Understanding in AI decision-Making Processes. Iconic Research and Engineering Journals, 2024, 8, 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. J.; Taylor, R.; Rees, J. Recent Advancement of Deep Learning Applications to Machine Condition Monitoring part 1: A Critical Review. Acoustics Australia, 2021, 49, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, V. S.; Caivano, D.; Gigante, D.; Ragone, A. A Rapid Review of Responsible AI Frameworks: How to Guide the Development of Ethical AI. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering; 2023; pp. 358–367. [Google Scholar]

- Oyeniran, O. C.; Adewusi, A. O.; Adeleke, A. G.; Akwawa, L. A.; Azubuko, C. F. AI-driven DevOps: Leveraging Machine Learning for Automated Software Deployment and Maintenance. No.December, vol. 2024, 2023.

- Rachakatla, S.K.; Ravichandran, P.; Kumar, N. Scalable Machine Learning Workflows in Data Warehousing: Automating Model Training and Deployment with AI. Australian Journal of AI and Data Science, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barh, D. Biotechnology in Healthcare, Volume 2: Applications and Initiatives; Academic Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, P. V. Medical biotechnology: Techniques and Applications. In Omics Technologies and Bio-Engineering, Anonymous; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 449–469. [Google Scholar]

- Anyanwu, E. C.; Arowoogun, J. O.; Odilibe, I. P.; Akomolafe, O.; Onwumere, C.; Ogugua, J. O. The Role of Biotechnology in Healthcare: A review of global trends. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 2024, 21, 2740–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, R.; Al-Turjman, F.; Chaudhary, P.; Yadav, S. P. (Benefits of internet of things (IoT) applications in health care-an overview). In 2023 International Conference on Computational Intelligence, Communication Technology and Networking (CICTN); 2023; pp. 778–784. [Google Scholar]

- Perwej, Y.; Haq, K.; Parwej, F.; Mumdouh, M.; Hassan, M. The Internet of Things (IoT) and its application domains. International Journal of Computer Applications, 2019, 975, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouha, R. A. R. A. Internet of Things (IoT). Journal of Data Analysis and Information Processing, 2021, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W. H. Current research on Internet of Things (IoT) security: A Survey. Computer Networks, 2019, 148, pp. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D. S. Decentralized finance (DeFi): Exploring the Role of Blockchain and Cryptocurrency in Financial Ecosystems. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Gupta, S.; Dua, A.; Kumar, N. Security of Cryptocurrencies in Blockchain Technology: State-of-art Challenges and Future Prospects. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 2020, 163, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi Joo, M.; Nishikawa, Y.; Dandapani, K. Cryptocurrency, a Successful Application of Blockchain Technology. Managerial Finance, 2020, 46, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbet, S.; Urquhart, A.; Yarovaya, L. Cryptocurrency and Blockchain Technology; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, N.; Sharma, A. Robotics and automation in manufacturing processes. In Intelligent Manufacturing, Anonymous; CRC Press; pp. 97–109.

- Sostero, M. Automation and Robots in Services: Review of Data and Taxonomy. 2020.

- Macrorie, R.; Marvin, S.; While, A. Robotics and automation in the city: a research agenda. Urban Geography, 2021, 42, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuric, A. M.; Urbanic, R. J.; Rickli, J. L. A framework for Collaborative Robot (CoBot) Integration in Advanced Manufacturing Systems. SAE International Journal of Materials and Manufacturing, 2016, 9, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Arif, S. M.; Aslam, M. Emerging Renewable and Sustainable Energy Technologies: State of the art. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2017, 71, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, J.; Masters, G. M. Energy for Sustainability: Technology, Planning, Policy; Island Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard, P. A.; Duic, N.; Noorollahi, Y.; Kalogirou, S. Renewable Energy for Sustainable Development. Renewable Energy, 2022, 199, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, S. L. The Advanced Materials Revolution: Technology and Economic Growth in the Age of Globalization; John Wiley & Sons, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba, R. Advanced Materials Engineering Fundamentals; After Midnight Publishing, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gottardo, S.; Mech, A.; Drbohlavová, J.; Małyska, A.; Bøwadt, S.; Sintes, J. R.; Rauscher, H. Towards Safe and Sustainable Innovation in Nanotechnology: State-of-play for Smart Nanomaterials. NanoImpact, 2021, 21, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Hsiang, E.; He, Z.; Zhan, T.; Wu, S. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Displays: Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives. Light: Science & Applications, 2021, 10, 216. [Google Scholar]

- Jaboob, A. M. M; Garad, A.; Al-Ansi, A. Analyzing Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) Recent Development in Education. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2023, 8, 100532. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, Q. A.; Al Ahmad, M.; Pecht, M. Quantum Computing: Navigating the Future of Computation, Challenges, and Technological Breakthroughs. Quantum Reports, 2024, 6, 627–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidary, J. D. Quantum Computing: An Applied Approach; Springer, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav, A.; Jadhav, V. S. A review on 3D printing: An additive Manufacturing Technology. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2022, 62, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Sharma, R.; Ranjan, K.; Pandey, D. K. Artificial Intelligence in Biotechnology. Artificial Intelligence and Biological Sciences, 2025, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Shabbir, K.; Mohsin, S. M.; Kumar, A.; Aziz, M.; Zubair, M.; Sultan, H. M. A New Era of Discovery: How Artificial Intelligence has Revolutionized the Biotechnology. Nepal Journal of Biotechnology, 2024, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izankar, S. V.; Kumar, P.; Waghmare, G. Evolution of Artificial Intelligence in Biotechnology: From Discovery to Ethical and Beyond. in AIP Conference Proceedings, 2024. In AIP Conference Proceedings; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S. pplications of Sensor Technology in Healthcare. in Revolutionizing Healthcare Treatment with Sensor Technology, Anonymous, IGI Global, 2024, pp. 79–99.

- Khan, A. O. R.; Islam, S. M.; Islam, A. T.; Paul, R.; Bari, M. S. Real-time Predictive Health Monitoring using AI-driven Wearable Sensors: Enhancing Early Detection and Personalized Interventions in Chronic Disease Management. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Kaunert, C.; Vig, K.; Gautam, B. K. Wearable Sensors Assimilated with Internet of Things (IoT) for Advancing Medical Imaging and Digital Healthcare: Real-time scenario. In Inclusivity and Accessibility in Digital Health, Anonymous; IGI Global, 2024; pp. 275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Kold, S.; Rahbek, O.; Bai, S. Wearable Sensors for Activity Monitoring and Motion Control: A review. Biomimetic Intelligence and Robotics, 2023, 3, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A. H.; Shahul, A.; George A., S. Wearable Sensors: A new way to track health and Wellness. Partners Universal International Innovation Journal, 2023, 1, 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Thompson, C.; Peterson, S.; Mandrola, J.; Beg, M. S. The future of Wearable Technologies and Remote Monitoring in Health Care. In American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. American Society of Clinical Oncology; Annual Meeting, 2019; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, A.; Mikalsen, M. Haugen; Woldaregay, A. Z.; Muzny, M.; Hartvigsen, G.; Hopstock, L. A.; Grimsgaard, S. Using Fitness Trackers and Smartwatches to Measure Physical Activity in Research: Analysis of Consumer Wrist-worn Wearables. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2018, 20, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.; Shandhi, M. M. H.; Master, H.; Dunn, J.; Brittain, E. Wearable Devices in Cardiovascular Medicine. Circ. Res., 2023, 132, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X. A comprehensive engineering Design Analysis of Apple Watch as a Smart Wearable Device. Applied and Computational Engineering, 2024, 71, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamone, F.; Masullo, M.; Sibilio, S. Wearable Devices for Environmental Monitoring in the Built Environment: a Systematic Review. Sensors, 2021, 21, 4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, H.; Channa, A.; Jeoti, V.; Stojanović, G. M. Comprehensive Review on Wearable Sweat-Glucose Sensors for Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Sensors, 2022, 22, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seshadri, D. R; Li, R. T.; Voos, J. E.; Rowbottom, J. R.; Alfes, C. M.; Zorman, C. A.; Drummond, C. K. Wearable Sensors for Monitoring the Physiological and Biochemical Profile of the Athlete. NPJ Digital Medicine, 2019, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Hong, J.; Park, S. Wearable Device for Continuous Sweat Lactate Monitoring in Sports: A Narrative Review. Frontiers in Physiology, 2024, 15, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatiwada, P.; Yang, B.; Lin, J.; Blobel, B. Patient-Generated Health Data (PGHD): Understanding, Requirements, Challenges, and Existing Techniques for Data Security and Privacy. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 2024, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacharodi, A.; Singh, P.; Meenatchi, R.; Tawfeeq Ahmed, Z. H.; Kumar, R. R.; N.V.; Kavish, S.; Maqbool, M.; Hassan, S. Revolutionizing Healthcare and Medicine: The Impact of Modern Technologies for a Healthier Future—A Comprehensive Review. Health Care Science, 2024, 3, 329–349. [CrossRef]

- Vidyarthi, A. Monitoring and Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases through Advanced Sensor Integration and Machine Learning Techniques. ” International Journal on Engineering Artificial Intelligence Management, Decision Support, and Policies, 2024, 1, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Kantartjis, M.; Severson, J.; Dorsey, R.; Adams, J.; Kangarloo, T.; Kostrzeb, M.; et al. Wearable Sensor-Based Assessments for Remotely Screening Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. Italian National Conference on Sensors 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raknim, P.; Lan, K. Gait Monitoring for Early Neurological Disorder Detection Using Sensors in a Smartphone: Validation and a Case Study of Parkinsonism. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sica, M.; Tedesco, S.; Crowe, C.; Kenny, L.; Moore, K.; Timmons, S.; Barton, J.; O’Flynn, B.; Komari, D. Continuous Home Monitoring of Parkinson’s Disease Using Inertial Sensors: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shcherbak, A.; Kovalenk, E.; Somov, A. Detection and Classification of Early Stages of Parkinson’s Disease Through Wearable Sensors and Machine Learning. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Pisani, A.; Mercuri, N.; Giannini, F.; Saggio, G. Assessment of Motor Impairments in Early Untreated Parkinson’s Disease Patients: The Wearable Electronics Impact. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, Q.C.; Motin, M.A.; Pah, N.D.; Drotár, P.; Kempster, P.; Kumar, D. Computerized Analysis of Speech and Voice for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2022, 226, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudzik, A.; Sledzianowski, A.; Przybyszewski, A.W. Machine Learning and Digital Biomarkers Can Detect Early Stages of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Italian National Conference on Sensors 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wal, A.; Singh, H. Mangla Nand; Vig, M. K. K.; Prakash, B. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning-Based Advances in the Management of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecular Targets and Therapeutic Interventions Against Neurodegenerative Diseases, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, L.; Han, Q. A Data Collection Protocol for Real-Time Sensor Applications. Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 2009, 5, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.; Shahab, S.; Yu, Y. Syndrome Pattern Recognition Method Using Sensed Patient Data for Neurodegenerative Disease Progression Identification. Diagnostics, 2023, 13, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhankhar, S.; Mujwar, S.; Garg, N.; Chauhan, S.; Saini, M.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S. Kumar; Rani, M. A. Kamal N. Artificial Intelligence in the Management of Neurodegenerative Disorders. CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders), 2024, 23, 931–940. [Google Scholar]

- Andriopoulos, E. The Rise of AI in Telehealth. In Emerging Practices in Telehealth; Anonymous Elsevier, 2023; pp. 183–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H. AI in Neurodegenerative Disease Research: Early Detection, Cognitive Decline Prediction, and Brain Imaging Biomarker Identification. Int J Eng Technol Res Manag, 2022, 6, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman, S. Artificial Intelligence in Neuro Degenerative Diseases: Opportunities and Challenges. AI and Neuro-Degenerative Diseases: Insights and Solutions, 2024, 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A. V.; Kumar, S.; Garg, V. K.; Goel, N.; Hoang, V. T.; Kashyap, D. Future perspectives for Automated Neurodegenerative Disorders Diagnosis: Challenges and Possible Research Directions. in Data Analysis for Neurodegenerative Disorders Anonymous Springer, 2023, pp. 255–267.

- Broza, Y.; Har-Shai, L.; Jeries, R.; Cancilla, J.C.; Glass-Marmor, L.; Lejbkowicz, I.; Torrecilla, J.; et al. Exhaled Breath Markers for Nonimaging and Noninvasive Measures for Detection of Multiple Sclerosis. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisch, U.; Schlesinger, I.; Ionescu, R.; Nassar, M.; Axelrod, N.; Robertman, D.; Tessler, Y.; et al. Detec- tion of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease from Exhaled Breath Using Nanomaterial-Based Sensors. Nanomedicine 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammed, K.; Chmiel, F.; Arora, S.; Gunter, K.; Husain, M.; Hu, M. Neu Health: Smartphone-Based Remote Digital Monitoring for Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia.” Neu Health: Smartphone-Based Remote Digital Monitoring for Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia, 2024.

- Lussier, M.; Lavoie, M.; Giroux, S.; Consel, C.; Guay, M.; Macoir, J.; Hudon, C.; et al. Early Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment With In-Home Monitoring Sensor Technologies Using Functional Measures: A Systematic Review. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigcha, L.; Borzì, L.; Amato, F.; Rechichi, I.; Ramos-Romero, C.; Cárdenas, A.; Gasco, L.; Olmo, G. Deep Learning and Wearable Sensors for the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Expert Systems with Applications 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).