Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We design a Lightweight Parallel Interaction Attention (LPIA) module to replace stacked Transformer layers, allowing efficient modeling of intra- and inter-modal relationships.

- We introduce a dual-gated fusion strategy to refine and dynamically combine multimodal features.

- We remove speaker embeddings entirely, enabling better generalization to unseen speakers and anonymous environments.

- We apply a self-distillation mechanism to internally extract and reuse useful emotional knowledge without requiring external teacher models.

2. Related Work

2.1. Multimodal Fusion Strategies in Emotion Recognition

2.2. Speaker Dependency and Real-World Limitations

2.3. Lightweight Learning with Self-Distillation

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Task Definition

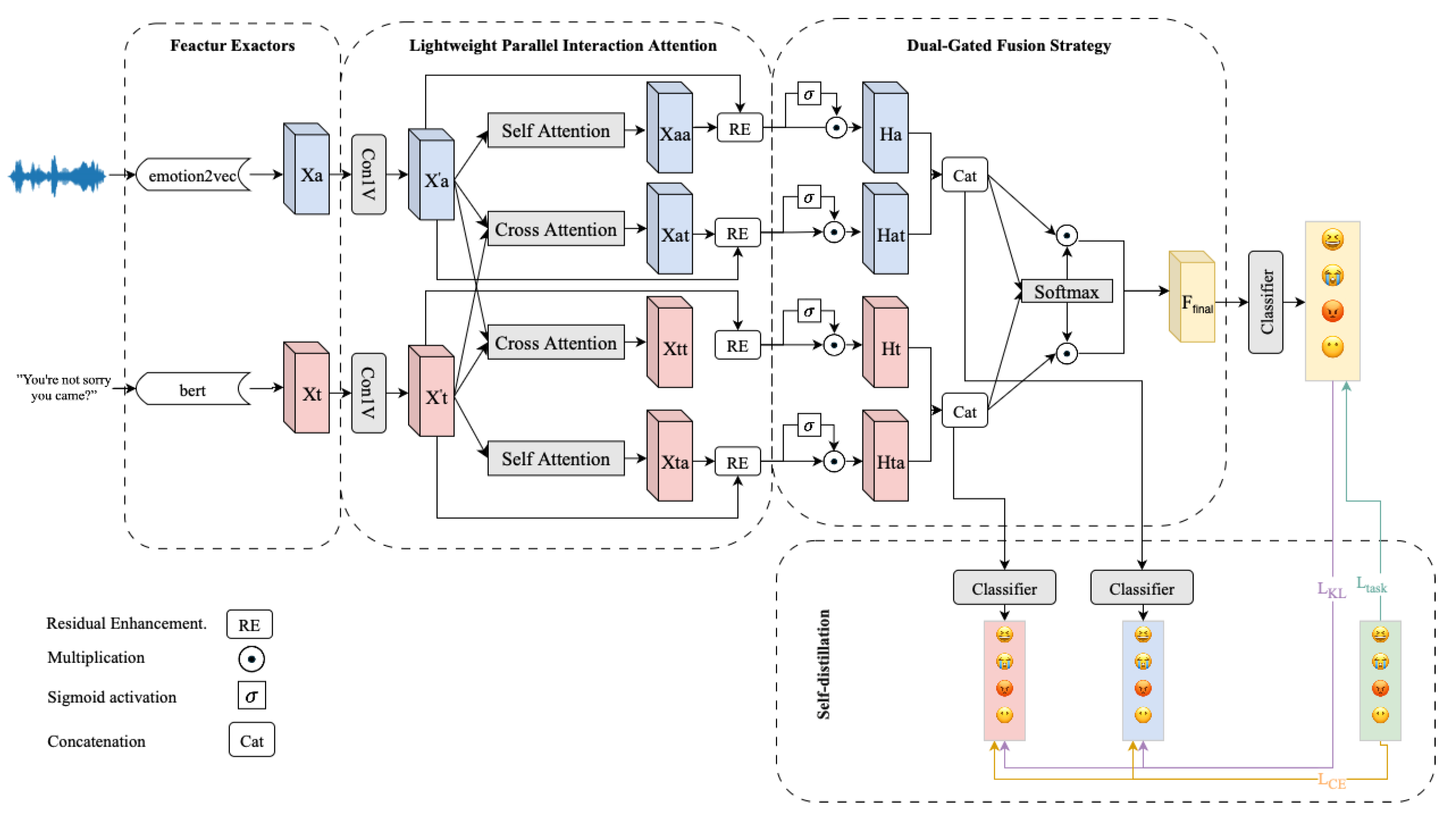

3.2. Overview

- Lightweight Parallel Interaction Attention (LPIA) module for capturing both intra- and inter-modal interactions simultaneously;

- Dual-Gated Fusion module for refining unimodal representations and adaptively fusing multimodal information;

- Emotion Classifier that predicts emotion labels from the final fused representation;

- Self-Distillation mechanism that aligns unimodal branches with the fused multimodal output using both hard and soft label supervision.

3.3. Lightweight Parallel Interaction Attention (LPIA)

- (1)

- Modality-wise Local Encoding via 1D Convolution.

- (2)

- Four-Way Parallel Attention Modeling.

- : intra-text attention for modeling semantic continuity;

- : intra-acoustic attention for modeling prosodic dynamics;

- : cross-modal audio-to-text interaction;

- : cross-modal text-to-audio interaction.

- (3)

- Mask-Aware Attention Computation.

- (4)

- Two-Stage Residual Enhancement.

- 1. Global Compression: We first compress the global context using a lightweight convolutional block composed of 1×1 convolution, batch normalization, and LeakyReLU activation:

-

2. Position-wise FFN with Residual Fusion: The compressed feature is broadcast back to the sequence dimension and fused with the original query and a position-wise feedforward network:Here, and are learnable weight matrices, where d is the hidden dimension of the model and is the intermediate feedforward dimension (typically or ). The GELU function introduces smooth non-linearity, and Dropout is used for regularization.

3.4. Dual-Gated Fusion Strategy

- (1)

- Unimodal Gated Fusion

- (2)

- Multimodal Gated Fusion

3.5. Emotion Classifier

3.6. Self-Distillation

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset and Evaluation

4.2. Feature Extraction

4.3. Implementation Details

4.4. Results

4.5. Ablation Study

| ACC (%) | F1 (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 87.35 | 87.38 |

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 86.36 | 86.53 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 87.27 | 87.26 |

| 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 87.59 | 87.58 |

| 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 87.99 | 87.96 |

| Happy | Sad | Neutral | Angry | Excited | Frustrated | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPGNet (4-class) | 92.06 | 85.38 | 83.99 | 86.75 | – | – | 87.83 |

| SDT* (4-class) | 89.72 | 86.35 | 82.32 | 88.15 | – | – | 86.62 |

| LPGNet (6-class) | 51.3 | 79.1 | 73.99 | 72.19 | 77.83 | 68.59 | 71.78 |

| SDT* (6-class) | 38.59 | 78.09 | 69.52 | 73.53 | 70.63 | 65.13 | 67.47 |

5. Conclusions

References

- Poria, S.; Majumder, N.; Mihalcea, R.; Hovy, E. Emotion recognition in conversation: Research challenges, datasets, and recent advances. IEEE access 2019, 7, 100943–100953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Luan, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Cui, J. Bert-erc: Fine-tuning bert is enough for emotion recognition in conversation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2023, Vol. 37, pp. 13492–13500. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, S.; El Emary, I.M. Speech emotion recognition approaches in human computer interaction. Telecommunication Systems 2013, 52, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, R.; Douglas-Cowie, E.; Tsapatsoulis, N.; Votsis, G.; Kollias, S.; Fellenz, W.; Taylor, J.G. Emotion recognition in human-computer interaction. IEEE Signal processing magazine 2001, 18, 32–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B. A transformer-based model with self-distillation for multimodal emotion recognition in conversations. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2023, 26, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, D.; Majumder, N.; Poria, S.; Chhaya, N.; Gelbukh, A. Dialoguegcn: A graph convolutional neural network for emotion recognition in conversation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.11540, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Shao, J.; Zhu, S.; Shen, H.T. Multivariate, multi-frequency and multimodal: Rethinking graph neural networks for emotion recognition in conversation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 10761–10770.

- Song, R.; Giunchiglia, F.; Shi, L.; Shen, Q.; Xu, H. SUNET: Speaker-utterance interaction graph neural network for emotion recognition in conversations. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 123, 106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Hu, Y.; He, L.; Huang, H. A bimodal network based on audio–text-interactional-attention with arcface loss for speech emotion recognition. Speech Communication 2022, 143, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Curtis, A. Bayesian inversion, uncertainty analysis and interrogation using boosting variational inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.17646, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, B.; Swain, M.; Guha, R.; Routray, A. Multimodal emotion recognition based on deep temporal features using cross-modal transformer and self-attention. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Q. MMGCN: Multimodal fusion via deep graph convolution network for emotion recognition in conversation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.06779, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T.; Xiao, Y. Dark experience for incremental keyword spotting. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025-2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE; 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Peng, T.; Das, R.K.; Hu, Y.; Zhuang, H. AnalyticKWS: towards exemplar-free analytic class incremental learning for small-footprint keyword spotting. arXiv preprint:2505.11817, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Yin, H.; Bai, J.; Das, R.K. Mixstyle based domain generalization for sound event detection with heterogeneous training data. arXiv preprint:2407.03654, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Das, R.K. Where’s That Voice Coming? Continual Learning for Sound Source Localization. arXiv preprint:2407.03661, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. A survey on evaluation of large language models. ACM transactions on intelligent systems and technology 2024, 15, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Akhtar, N.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A comprehensive overview of large language models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Das, R.K. WildDESED: an LLM-powered dataset for wild domestic environment sound event detection system. arXiv preprint:2407.03656, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Gong, Z.; Ai, L.; Shi, P.; Donbekci, K.; Hirschberg, J. Beyond silent letters: Amplifying llms in emotion recognition with vocal nuances. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21315, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Tiwari, P.; Li, Q.; Wang, B.; Qin, J. Dialoguellm: Context and emotion knowledge-tuned large language models for emotion recognition in conversations. Neural Networks 2025, p. 107901.

- Xue, J.; Nguyen, M.P.; Matheny, B.; Nguyen, L.M. Bioserc: Integrating biography speakers supported by llms for erc tasks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks. Springer, 2024, pp. 277–292.

- Zhang, L.; Song, J.; Gao, A.; Chen, J.; Bao, C.; Ma, K. Be your own teacher: Improve the performance of convolutional neural networks via self distillation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 3713–3722. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bao, C.; Ma, K. Self-distillation: Towards efficient and compact neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, 44, 4388–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Das, R.K. Ucil: An unsupervised class incremental learning approach for sound event detection. arXiv preprint:2407.03657, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Liang, S.N.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Z. Teacher-free distillation via regularizing intermediate representation. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE; 2022; pp. 01–06. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Leng, Q.; Zhao, X. Deep learning-based multimodal emotion recognition from audio, visual, and text modalities: A systematic review of recent advancements and future prospects. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 237, 121692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, D.; Poria, S.; Zadeh, A.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.P.; Zimmermann, R. Conversational memory network for emotion recognition in dyadic dialogue videos. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the conference. Association for Computational Linguistics. North American Chapter. Meeting, 2018, Vol. 2018, p. 2122.

- Hazarika, D.; Poria, S.; Mihalcea, R.; Cambria, E.; Zimmermann, R. Icon: Interactive conversational memory network for multimodal emotion detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2018, pp. 2594–2604.

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, R.; Tao, X.; Guo, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, X. Multimodal emotion recognition based on audio and text by using hybrid attention networks. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 85, 105052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.K.; Lim, E.; Kim, S.H.; Yang, H.J.; Kim, S. Enhanced Emotion Recognition Through Dynamic Restrained Adaptive Loss and Extended Multimodal Bottleneck Transformer. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, D.; Majumder, N.; Gelbukh, A.; Mihalcea, R.; Poria, S. Cosmic: Commonsense knowledge for emotion identification in conversations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02795, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.; Chen, J.; Quan, X.; Xie, Z. Dialogxl: All-in-one xlnet for multi-party conversation emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 13789–13797.

- Kuhlen, A.K.; Rahman, R.A. Mental chronometry of speaking in dialogue: Semantic interference turns into facilitation. Cognition 2022, 219, 104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Zhu, B.; Chen, J.; Cheng, L.; Jiang, Y.G. Mix-dann and dynamic-modal-distillation for video domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2022, pp. 3224–3233.

- Aslam, M.H.; Pedersoli, M.; Koerich, A.L.; Granger, E. Multi Teacher Privileged Knowledge Distillation for Multimodal Expression Recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.09035, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Busso, C.; Bulut, M.; Lee, C.C.; Kazemzadeh, A.; Mower, E.; Kim, S.; Chang, J.N.; Lee, S.; Narayanan, S.S. IEMOCAP: Interactive emotional dyadic motion capture database. Language resources and evaluation 2008, 42, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Murthy, S.M.K.; Alturki, E.; Schuller, B.W. GatedxLSTM: A Multimodal Affective Computing Approach for Emotion Recognition in Conversations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.20919, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, N.; Zhang, L.; Shan, L. Emotion Recognition for Multimodal Information Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computational Networks (ICISCN). IEEE; 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Qin, Y. Enhancing multimodal emotion recognition through multi-granularity cross-modal alignment. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025-2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE; 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Li, X.; Toda, T. Emotion awareness in multi-utterance turn for improving emotion prediction in multi-speaker conversation. In Proceedings of the Proc. interspeech, 2023, Vol. 2023, pp. 765–769.

- Adeel, M.; Tao, Z.Y. Enhancing speech emotion recognition in urdu using bi-gru networks: An in-depth analysis of acoustic features and model interpretability. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- Khan, M.; Tran, P.N.; Pham, N.T.; El Saddik, A.; Othmani, A. MemoCMT: multimodal emotion recognition using cross-modal transformer-based feature fusion. Scientific reports 2025, 15, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Ye, J.; Li, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X. emotion2vec: Self-supervised pre-training for speech emotion representation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.15185, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, H.; Huang, H.; He, L. Cross-modal Features Interaction-and-Aggregation Network with Self-consistency Training for Speech Emotion Recognition [C]. In Proceedings of the Proc. Interspeech 2024, 2024, pp. 2335–2339.

- Sun, H.; Lian, Z.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Sun, L.; Cai, C.; Tao, J.; Wang, M.; Cheng, Y. EmotionNAS: Two-stream neural architecture search for speech emotion recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.13617, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Xing, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Fan, H.; Xu, X. Multi-scale temporal transformer for speech emotion recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.00390, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, K.; Sharma, K.K.; Varma, T. Multimodal Emotion Recognition Using Contextualized Audio Information and Ground Transcripts on Multiple Datasets. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2024, 49, 11871–11881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Split | Happy | Sad | Neutral | Angry | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train + Val | 1262 | 828 | 1319 | 872 | 4290 |

| Test | 442 | 245 | 384 | 170 | 1241 |

| Total | 1704 | 1073 | 1703 | 1042 | 5531 |

| Model | Upstream(A) | Upstream(T) | ACC (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GatedxLSTM [38] | CLAP | CLAP | – | 75.97±1.38 |

| MER-HAN [30] | Bi-LSTM | BERT | 74.20 | 73.66 |

| MMI-MMER [39] | Wav2Vec2 | BERT | 77.02 | – |

| MGCMA [40] | Wav2Vec2 | BERT | 78.87 | – |

| MEP [41] | openSMILE | BERT | 80.18 | 80.01 |

| Bi-GRU [42] | Acoustic model | GloVe | 80.63 | – |

| MemoCMT[43] | HuBERT | BERT | 81.85 | – |

| Linear[44] | emotion2vec | BERT | 81.68 | 80.75 |

| CFIA[45] | emotion2vec | BERT | 83.37 | – |

| LPGNet(Frame) | emotion2vec | BERT | 83.87 | 83.68 |

| LPGNet(Utterance) | emotion2vec | BERT | 87.99 | 87.96 |

| ACC (%) | F1 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| LPGNet | 87.99 | 87.96 |

| Modality | ||

| Text | 81.39 | 81.19 |

| Audio | 84.53 | 84.55 |

| LPIA Block | ||

| w/o inter attention | 86.22 | 86.26 |

| w/o intra attention | 87.03 | 86.95 |

| w/o position-wise FFN | 86.87 | 86.75 |

| w/o dual-gated fushion | 86.62 | 86.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).