Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

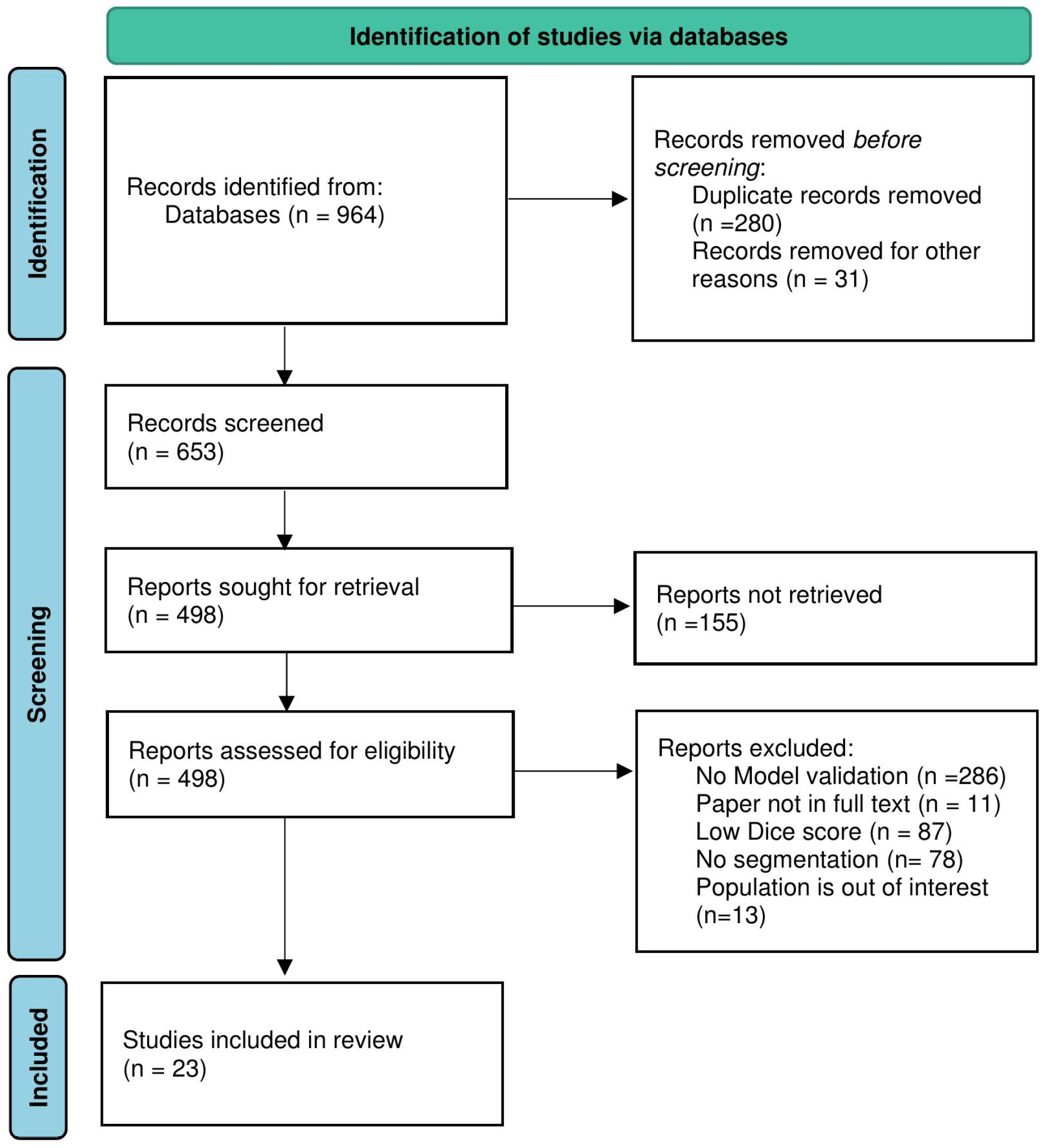

2.1. Study Search Strategy

3. Results

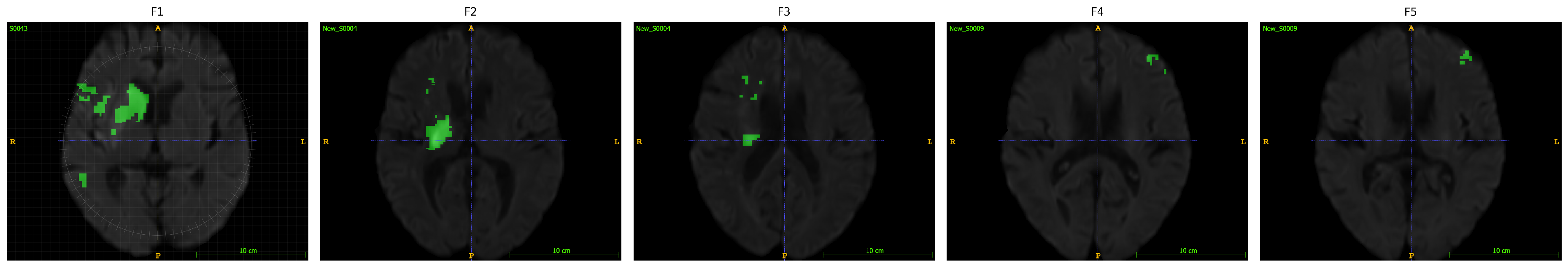

3.1. Machine Learning-Driven Stroke Lesion Segmentation with ATLAS Dataset

3.2. Post-Stroke Recovery Prediction through Machine Learning Techniques

| Ref | Preprocessing | Dataset | Segmentation Method | Loss function | Performance Metric | Gap/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

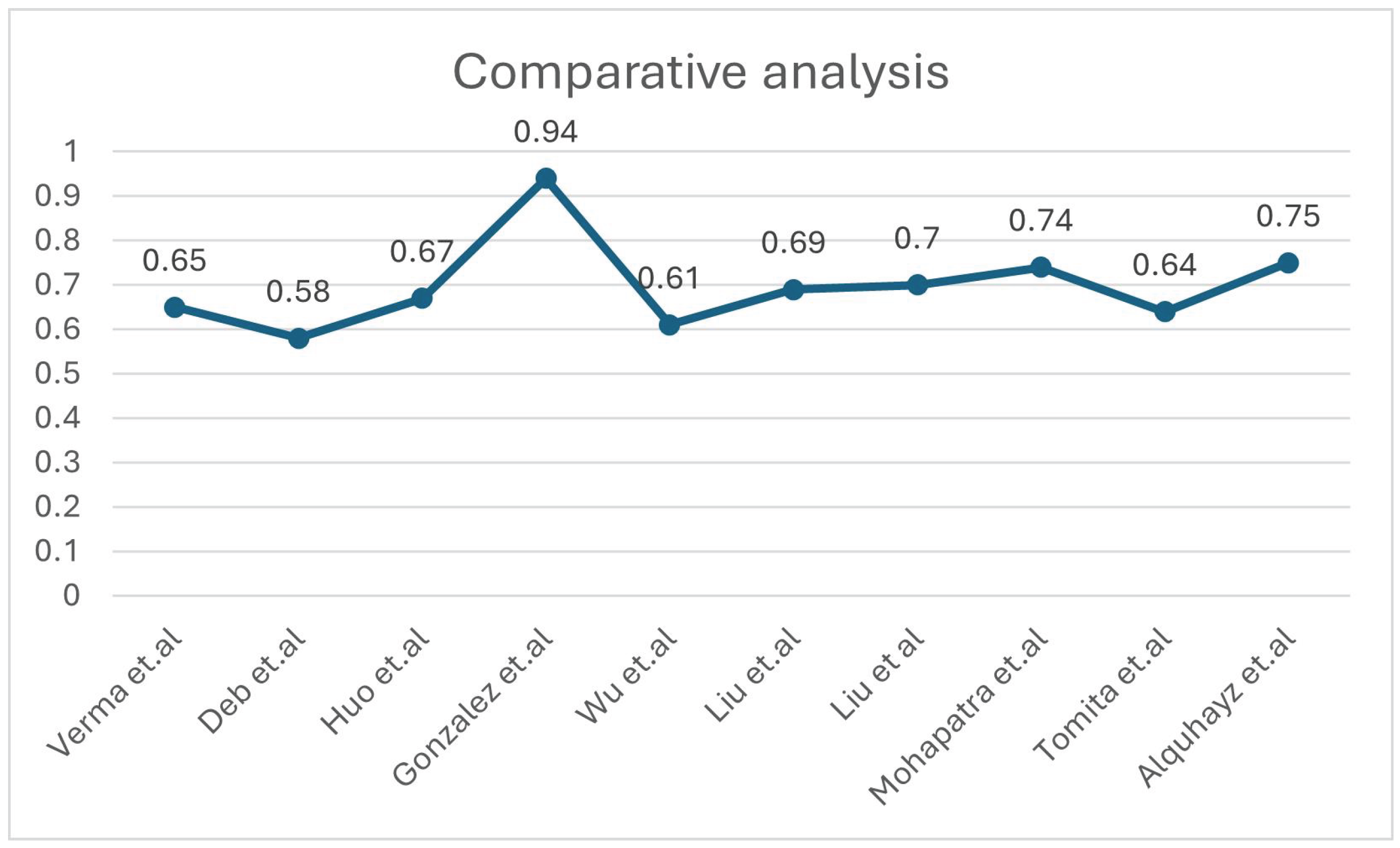

| [14] | Intensity normalisation, registration and defacing, brain extraction, skull removing | ATLAS V2.0 | Deep Neural Network (DNN) using 3D-UNet with 5-fold cross-validation | NM | DSC =0.65 | Although potential biases from the manual segmentation process could influence the model, and the reliance on a subset for testing may limit generalizability, the scarcity of publicly accessible stroke datasets with manual segmentation labels makes independent validation. |

| [11] | Z-score Norma, Slicing for 2D modality. | ATLAS V2.0 | Multiple U Net variants | Proportionate weightage for Dice Loss (DICE) and Binary Cross-Entropy Loss (BCE) | Dice: 0.583 | There’s a need for better data augmentation, U-Net models, supervised learning, handling small lesions, and decision-making uncertainty. |

| [12] | Normalisation and Registration | ATLAS V2.0 | nnU-Net | compound loss (Dice plus cross-entropy), TopK10 loss | Dice: 0.6667 | Small stroke lesions are hard to segment, especially with artifacts or similar intensities to surrounding tissue. Training schemes often predict unconnected lesions as continuous grey matter due to similar intensities. |

| [15] | Gaussian denoising | ATLAS V2.0 | Fuzzy Information Seeded Region Growing (FISRG) algorithm | DiNM | Dice: 0.94 | The algorithm struggles with abrupt lesion topology changes, misclassifies regions with similar intensities, and has increased computational time. Intensity-based classification causes errors, especially with variable lesion textures. |

| [18] | Image Slicing, Cropping, Patch Partitioning, Patch Embedding, Normalization and Augmentation | ATLAS v1 | MLiRA-Net (Multi-scale Long-range Interactive and Regional Attention Network) | dice loss + weighted binary cross-entropy loss. | Dice: 0.6119 | It comes at the cost of increased computational complexity. Additionally, the current implementation is limited to two-dimensional segmentation. |

| [16] | Matrix complement and clipping method | ATLAS V2.0 | Hybrid Contextual Semantic Network (HCSNet) | Mixing-Loss Function | Dice: 0.69 | Segmenting small lesions is challenging due to the heavy reliance on training data quality and quantity. Additionally, the model’s ability to generalize to real-world clinical settings needs further validation. |

| [17] | Intensity Correction, MNI-152 template registration | ATLAS V2.0 | Simulated Quantum Mechanics-based joint Learning Network (SQMLP-net) | The joint loss function incorporates the segmentation and classification losses | Dice: 0.7098 | Finding the right balance between the trade-offs of multi-task learning weights is crucial for optimising task performance. |

| [13] | Resampling and Normalisation, Skull Stripping, Slicing and Augmentation | ATLAS V2.0 | Transfer Learning and mixed data approaches. | NM | Dice: 0.736 | The ensemble methods’ accuracy may change by the chosen parameters, which may require further adjustment for different datasets or lesion types. The ensemble method tends to overpredict lesions by approximately 10%. |

| [19] | Normalisation, Cropping, Zoom-in &out Training Strategy | ATLAS v1 | 3D U-Net architecture with residual learning | Binary cross entropy (BCE)+Dice Loss | Dice: 0.64 | The small dataset limits generalizability, and the model struggles with smaller lesions. Further validation with diverse scanners is needed. Manual tracing introduces variability, and the dataset only focuses on embolic strokes, leaving other types untested. |

| [30] | Slice Selection, Patch Extraction, Data Augmentation | ATLAS v1 | U-Net architecture with Xception as the backbone- XU-Net | BCE & Jaccard Coefficient | Dice: 0.754 | The study struggles with accurately segmenting small stroke lesions and reducing false positives. The model’s generalizability requires further validation on diverse datasets. Additionally, the approach increases computational complexity, limiting real-time application. |

| Ref | Study Design | Sample Size | Data Modality | Method | Focus Area | Performance Metrics | Gap/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [27] | Longitudinal design | 57 patients | Resting-State Functional MRI, Behavioral Language Measures | Elastic net regression models | Language Recovery | R2 = 0.948 | Small sample size & lack of validation set. Use of LOOCV (Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation)-A less robust and reliable model selection method. Recruitment constraints & Minimal fMRI filteringresults in lower accuracy and generalizability |

| [28] | Longitudinal design | 37 patients | T2 and diffusion-weighted MRI, Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA) scores | Ridge regression | Motor Recovery | R2 = 0.68 | Small sample size & no age-matching, Manual lesion masking, Larger, diverse cohorts required to confirm findings. |

| [20] | Longitudinal design | 48 patients | magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted images & CT (one case) | Logistic and linear regression models | upper extremity motor recovery | AUC=ranging from 0.70 to 0.8 | The study sample was younger, predominantly male, and ethnically homogeneous compared to national averages, with a small sample size of 48 participants. |

| [21] | Longitudinal design | 7,858 patients | Demographic and clinical characteristicss | K-means clustering | Functional recovery | ischemic-: 0.926 hemorrhagic-: 0.887 | Survivor bias, Design limitations- Absence of functional MRI or dynamic nomograms |

| [22] | prospective cohort study | 29 patients | Transcranial magnetic stimulation or Diffusion tensor imaging parameters or their combinations | Multivariate logistic regression analysis | The upper-limb motor function | predictive ability=93.3% | Rigorous inclusion criteria: Only 29 patients enrolled, limiting generalizability Exclusions: Participants with medical issues were excluded, potentially skewing the results. |

| [23] | Longitudinal design | 334 patients | Demographic factors, MRI or CT imaging | linear model | Language Recovery | QAB overall = 59.5% of the variance | Smaller group sizes and missing data points, Lesions identified through acute clinical imaging may not accurately reflect irreversible tissue damage, QAB limitation: Doesn’t assess written word comprehension or writing. |

| [29] | retrospective cohort study | 104, 42 patients | Structural, diffusion, and functional magnetic resonance imaging | multiple linear regression algorithm | Upper Extremity Motor Recovery | R² = 0.853 | Small sample size, Single-center study. |

| [26] | Retrospective cohort study | 1265 patients | Data from electronic records | multivariable logistic regression model | motor impairment | AUC=0.833 | Retrospective design: May introduce biases, No control group, Dynamic motor changes: Study does not account for rehabilitation-related variations. |

| [25] | Retrospective cohort study | 717 patients | Clinical and Demographic data | multivariable logistic regression model | Physical functioning | AUC=0.883 | Retrospective design: Introduces biases, Exclusion of mild stroke patients, and did not assess the prognostic role of neuroimaging. |

| [24] | Observational prospective cohort design | 87 patients | Clinical, Demographic, and Statistical data, Accelerometer Data | multivariate regression model | upper-limb | AUC=0.86 | Limited accelerometer use, and visible devices could have led to overestimation. |

| [31] | Longitudinal cohort design | 55 patients | Demographic, Clinical, Biochemical and Hematological Parameters, Health Status Data at Discharge | SVM | Motor and cognitive improvement | Correlation ranged from 0.75 to 0.81 | Single hospital data, reliance on common inflammatory biomarkers, which can vary between individuals, and short follow-up period. |

| [32] | Cross-sectional design | 758 patients | T1-weighted structural MRI, demographic and clinical characteristics | CNN | Aphasia | Classification accuracy = 0.854 | Restricted to research-quality MRI scanners, and the measure of initial severity is relatively crude. Overfitting risk, and simplifies the Comprehensive Aphasia Test T-scores. |

| [33] | Retrospective cohort study | 778 patients | Demographic, Clinical Information, Functional Scores at Admission. | Machine learning models | Walking independence. | LR:AUC: 0.891, XGBoost:AUC: 0.880, SVM:AUC: 0.659, RF:AUC: 0.713 | Retrospective, single-center design, No external validation, Only clinical admission data were used, No long-term outcomes. |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATLAS | Anatomical Tracings of Lesions After Stroke |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BCE | Binary Cross-Entropy Loss |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CST | Corticospinal Tracts |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DICE | Dice Loss |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DTI | Diffusion Tensor Imaging |

| eXGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| FAC | Functional Ambulation Category |

| fALFF | fractional Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuations |

| FISRG | Fuzzy Information Seeded Region Growing |

| FMA | Fugl-Meyer Assessment |

| FMA-LE | Fugl-Meyer Motor Assessment of the Lower Extremity |

| HCSM | Hybrid Contextual Semantic Module |

| HCSNet | Hybrid Contextual Semantic Network |

| ISLES’22 | Ischemic Stroke Lesion Segmentation Challenge 2022 |

| ISLES’24 | Ischemic Stroke Lesion Segmentation Challenge 2024 |

| LR | Linear Regression |

| MEP | Motor-Evoked Potentials |

| MICCAI | Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention |

| MI | Mutual Information |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLiRA-Net | Multi-scale Long-range Interactive and Regional Attention Network |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| QAB | Quick Aphasia Battery |

| RF | Random Forest |

| rsfMRI | Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| SQMLP-net | Simulated Quantum Mechanics-based Joint Learning Network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TICI | Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction |

| TMS | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| UL | Upper Limb |

| U-Net | U-shaped Convolutional Neural Network |

| VNet | V-shaped Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- Mackay, J.; Mensah, G.A. The Atlas of Heart Disease and Stroke; World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, X.; Zheng, Y.; Tao, J.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, L. Association study of polymorphisms in the ABO gene with ischemic stroke in the Chinese population. BMC Neurology 2016, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Muntner, P.; Alonso, A.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; et al. . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e56–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, C.K.; Gupta, V.; Khandelwal, N. Acute Stroke Imaging: Current Trends. Annals of the National Academy of Medical Sciences (India) 2019, 55, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, O.; Schröder, C.; Forkert, N.D.; Martinetz, T.; Handels, H. Classifiers for Ischemic Stroke Lesion Segmentation: A Comparison Study. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0145118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, T.M.H.; Seghier, M.L.; Leff, A.P.; Price, C.J. Predicting outcome and recovery after stroke with lesions extracted from MRI images. NeuroImage: Clinical 2013, 2, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulnaga, S.M.; Rubin, J. Ischemic Stroke Lesion Segmentation in CT Perfusion Scans using Pyramid Pooling and Focal Loss. arXiv, 2018. Version 1.

- Halme, H.L.; Korvenoja, A.; Salli, E. ISLES (SISS) Challenge 2015: Segmentation of Stroke Lesions Using Spatial Normalization, Random Forest Classification and Contextual Clustering. In Brainlesion: Glioma, Multiple Sclerosis, Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injuries; Crimi, A., Menze, B., Maier, O., Reyes, M., Handels, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kamnitsas, K.; Ledig, C.; Newcombe, V.F.J.; Simpson, J.P.; Kane, A.D.; Menon, D.K.; et al. . Efficient multi-scale 3D CNN with fully connected CRF for accurate brain lesion segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2017, 36, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, S.L.; Lo, B.P.; Donnelly, M.R.; Zavaliangos-Petropulu, A.; Jeong, J.N.; Barisano, G.; et al. . A large, curated, open-source stroke neuroimaging dataset to improve lesion segmentation algorithms. Scientific Data 2022, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P.; Baru, L.B.; Dadi, K.; S, B.R. BeSt-LeS: Benchmarking Stroke Lesion Segmentation using Deep Supervision. arXiv, 2023. Version 1.

- Huo, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Boels, M.; Granados, A.; Ourselin, S.; et al. . MAPPING: Model Average with Post-processing for Stroke Lesion Segmentation. arXiv, 2022. Version 1.

- Mohapatra, S.; Gosai, A.; Shinde, A.; Rutkovskii, A.; Nouduri, S.; Schlaug, G. Meta-Analysis of Transfer Learning for Segmentation of Brain Lesions. arXiv, 2023, [2306.11714].

- Verma, K.; Kumar, S.; Paydarfar, D. Automatic Segmentation and Quantitative Assessment of Stroke Lesions on MR Images. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.P. Fuzzy Information Seeded Region Growing for Automated Lesions After Stroke Segmentation in MR Brain Images. arXiv, 2023. Version 1.

- Liu, L.; Chang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Xu, X.; Shang, H. Hybrid Contextual Semantic Network for Accurate Segmentation and Detection of Small-Size Stroke Lesions From MRI. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023, 27, 4062–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Chang, J.; Liang, G.; Xiong, S. Simulated Quantum Mechanics-Based Joint Learning Network for Stroke Lesion Segmentation and TICI Grading. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023, 27, 3372–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Huang, L. Multi-scale long-range interactive and regional attention network for stroke lesion segmentation. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2022, 103, 108345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, N.; Jiang, S.; Maeder, M.E.; Hassanpour, S. Automatic post-stroke lesion segmentation on MR images using 3D residual convolutional neural network. NeuroImage: Clinical 2020, 27, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.J.; Cloutier, A.M.; Erler, K.S.; Cassidy, J.M.; Snider, S.B.; Ranford, J.; et al. . Corticospinal Tract Injury Estimated From Acute Stroke Imaging Predicts Upper Extremity Motor Recovery After Stroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 3569–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Chang, W.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, J.; Sohn, M.K.; Song, M.K.; et al. . Clustering and prediction of long-term functional recovery patterns in first-time stroke patients. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14, 1130236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Prasad, M.; Das, A.; Vibha, D.; Garg, A.; Goyal, V.; et al. . Utility of transcranial magnetic stimulation and diffusion tensor imaging for prediction of upper-limb motor recovery in acute ischemic stroke patients. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 2022, 25, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.M.; Entrup, J.L.; Schneck, S.M.; Onuscheck, C.F.; Levy, D.F.; Rahman, M.; et al. . Recovery from aphasia in the first year after stroke. Brain 2023, 146, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundquist, C.B.; Nielsen, J.F.; Brunner, I.C. Prediction of Upper Limb use Three Months after Stroke: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2021, 30, 106025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrutinio, D.; Lanzillo, B.; Guida, P.; Mastropasqua, F.; Monitillo, V.; Pusineri, M.; et al. . Development and Validation of a Predictive Model for Functional Outcome After Stroke Rehabilitation: The Maugeri Model. Stroke 2017, 48, 3308–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrutinio, D.; Guida, P.; Lanzillo, B.; Ferretti, C.; Loverre, A.; Montrone, N.; et al. . Rehabilitation Outcomes of Patients With Severe Disability Poststroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2019, 100, 520–529.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorga, M.; Higgins, J.; Caplan, D.; Zinbarg, R.; Kiran, S.; Thompson, C.K.; et al. . Predicting language recovery in post-stroke aphasia using behavior and functional MRI. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivier, C.; Preti, M.G.; Nicolo, P.; Van De Ville, D.; Guggisberg, A.G.; Pirondini, E. Prediction of poststroke motor recovery benefits from measures of sub-acute widespread network damages. Brain Communications 2023, 5, fcad055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Chang, W.H.; Kim, Y.H. Multimodal Imaging Biomarker-Based Model Using Stratification Strategies for Predicting Upper Extremity Motor Recovery in Severe Stroke Patients. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair 2022, 36, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquhayz, H.; Tufail, H.Z.; Raza, B. The multi-level classification network (MCN) with modified residual U-Net for ischemic stroke lesions segmentation from ATLAS. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 151, 106332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sale, P.; Ferriero, G.; Ciabattoni, L.; Cortese, A.M.; Ferracuti, F.; Romeo, L.; et al. . Predicting Motor and Cognitive Improvement Through Machine Learning Algorithm in Human Subject that Underwent a Rehabilitation Treatment in the Early Stage of Stroke. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2018, 27, 2962–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Saranti, M.; d’Avila Garcez, A.; Hope, T.M.H.; Price, C.J.; Bowman, H. Predicting recovery following stroke: Deep learning, multimodal data and feature selection using explainable AI. NeuroImage: Clinical 2024, 43, 103638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Su, W.; Liu, T.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; et al. . Prediction of poststroke independent walking using machine learning: a retrospective study. BMC Neurology 2024, 24, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabal, M.S.; Joly, O.; Kallmes, D.; Harston, G.; Rabinstein, A.; Huynh, T.; et al. . Interpretable Machine Learning Modeling for Ischemic Stroke Outcome Prediction. Frontiers in Neurology 2022, 13, 884693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).