1. Introduction

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a rare yet highly aggressive malignancy originating from the adrenal cortex, with an estimated annual incidence of 0.7–2 cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States [

1,

2,

3]. The disease is associated with poor prognosis and frequent recurrence, necessitating early and accurate diagnosis [

3]. Comprehensive diagnostic evaluation typically involves clinical assessment [

4], hormonal profiling [

5], and imaging studies [

6,

7]. Among imaging modalities, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers high-resolution, multiparametric capabilities for noninvasive adrenal lesion characterization [

8].

Despite their widespread use and high spatial resolution, conventional imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) have notable limitations in detecting subtle radiological features that may indicate early or atypical manifestations of malignancy [

9,

10]. Diagnostic assessments typically depend on qualitative interpretation of morphological characteristics and quantitative measures such as attenuation values or signal intensities, which may overlook nuanced patterns associated with tumor heterogeneity or early disease progression [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Consequently, this subjective reliance can contribute to diagnostic variability and potential misclassification, particularly in challenging or equivocal cases.

To overcome these limitations, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques are being developed and increasingly integrated into radiological workflows to enhance diagnostic precision and reproducibility [

15,

16,

17]. These data-driven approaches enable the extraction and analysis of complex, high-dimensional imaging features—often imperceptible to the human eye—through techniques such as radiomics, deep learning, and texture analysis [

18,

19,

20].

For instance, Elmohr et al. demonstrated that CT-based texture analysis could achieve a diagnostic accuracy of 82% in differentiating adrenal lesions, outperforming conventional radiological interpretation, which achieved an accuracy of 68.5% [

21]. Similar studies have shown that AI-enhanced imaging can improve lesion detection, risk stratification, and treatment planning in various oncologic contexts [

21,

22].

Nevertheless, despite these promising advancements, the clinical adoption of AI-driven tools remains limited due to several challenges, including data heterogeneity, lack of standardized protocols, limited external validation, and concerns about model interpretability and generalizability [

23,

24]. Continued research, multidisciplinary collaboration, and regulatory guidance are essential to facilitate the integration of AI into routine radiological practice.

Deep learning (DL) models, a specialized subset of machine learning (ML), have revolutionized medical image analysis by enabling automatic feature extraction and reducing the need for manual intervention. These models have shown remarkable success across various tasks, including tumor segmentation, classification, and prognosis prediction in oncologic imaging [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. In MRI-based studies, for instance, Moawad et al. utilized ML techniques in combination with radiomic feature extraction to effectively classify adrenal lesions into benign, malignant, and incidental categories using contrast-enhanced scans. This approach addressed significant diagnostic challenges, particularly in cases involving small or incidentally discovered lesions [

33]. Similarly, Kazemi et al. investigated the performance of two convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures—ResNet18 and ShuffleNet—for brain tumor classification. Both models achieved high diagnostic accuracy (97.86%), with ShuffleNet demonstrating superior computational efficiency due to its lightweight structure [

34].

Beyond classification, DL approaches have also been explored for tumor segmentation using architectures such as U-Net and V-Net, which have shown promise in delineating complex tumor boundaries in brain and abdominal imaging [

35,

36,

37] Furthermore, recent studies have incorporated hybrid approaches that combine radiomics, DL features, and clinical data to enhance model interpretability and predictive power [

22,

38,

39]

This study evaluates and compares the diagnostic performance of four widely used pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures—VGG16, ResNet50, MobileNetV2, and ConvNeXtTiny—with two custom-designed CNN models optimized using the Optuna hyperparameter tuning framework. One of the custom models was specifically developed to achieve a significantly reduced parameter count, emphasizing computational efficiency. By examining both classification accuracy and model complexity, the study explores the trade-offs between leveraging transfer learning from large-scale pre-trained models and designing lightweight, task-specific architectures for MRI-based diagnosis of adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC). This comparison aims to inform model selection strategies where diagnostic performance must be balanced against computational resource constraints, especially in clinical or low-resource settings.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data

Predictive deep learning models require large, well-annotated, and validated datasets to achieve robust and generalizable performance. In this study, the dataset was compiled from publicly accessible sources, including PubMed, Radiomedia, The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA), PubMed Central, the National Cancer Institute, the International Cancer Imaging Society, and DataMed. The final dataset consisted of 1,580 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the adrenal glands acquired across multiple anatomical planes—axial, coronal, and sagittal. Among these, 940 images represented cases of adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), while 640 depicted normal adrenal glands.

All ACC cases were confirmed as Stage II based on the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENSAT) staging system [

40] and were collected prior to the initiation of chemotherapy. The dataset included various image formats, such as .jpeg, .jpg, .bmp, and .png. For binary classification purposes, labels were assigned as follows: 0 for normal adrenal glands and 1 for ACC. The dataset was randomly partitioned into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%) to facilitate model development and performance evaluation.

2.2. Pretrained Models

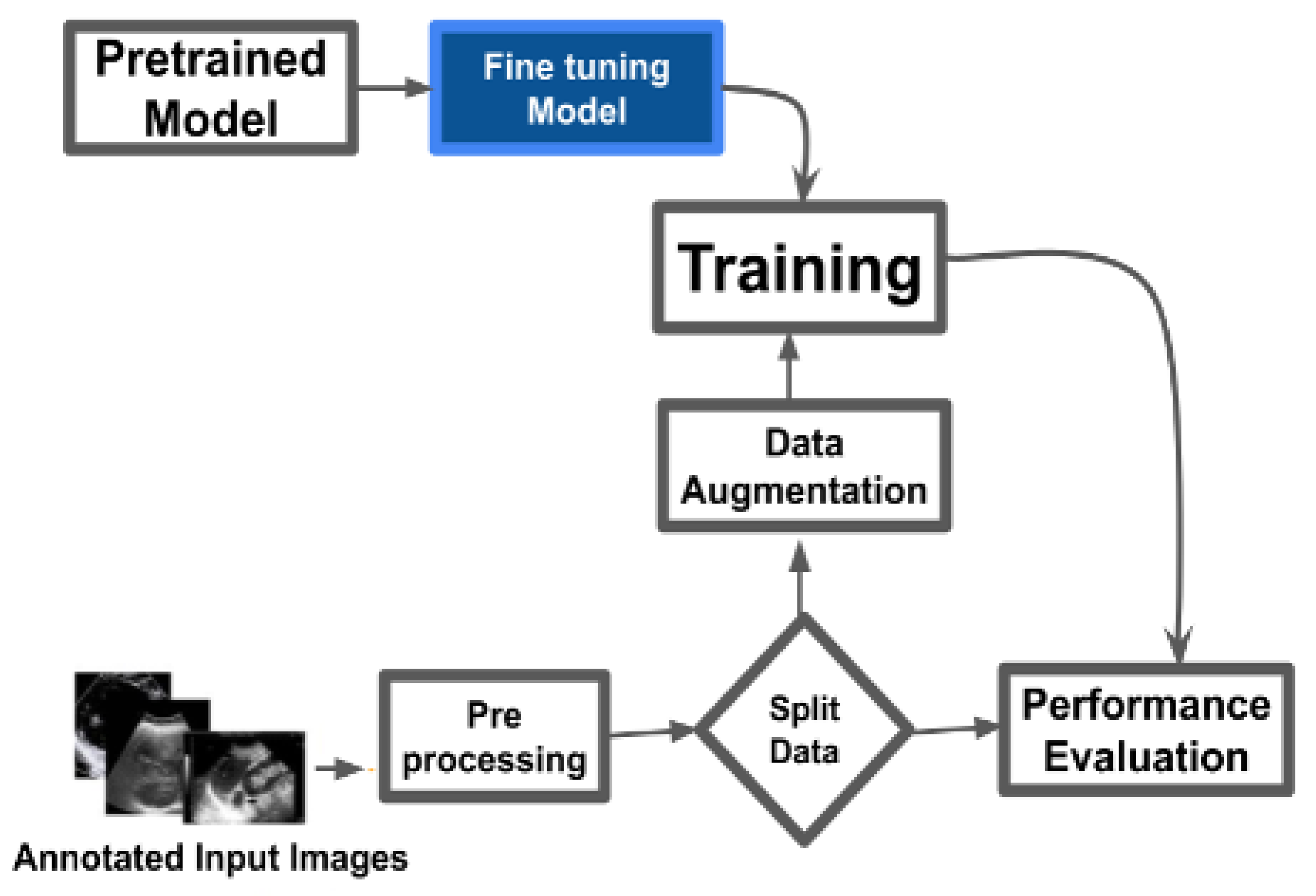

As shown in

Figure 1, the pretrained models – VGG16 [

41], ResNet50 [

42], ConvNeXtTiny [

43], and MobileNetV2 [

44] – were used for binary classification of cancerous and normal MRI images. Images underwent preprocessing steps including resizing, normalization, and format conversion to ensure compatibility with model input requirements. The dataset was divided into training and testing sets with an 80:20 ratio. Data augmentation techniques such as rotation, flipping, zooming, and translation were applied to the training data to enhance generalization and mitigate overfitting. Each model was initialized with ImageNet-pretrained weights. The fully connected (top) layers were removed and replaced with custom dense layers tailored to the binary classification task. Training was performed using tuned hyperparameters such as learning rate, batch size, and number of epochs. Model performance was assessed using standard evaluation metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, confusion matrix, and ROC-AUC.

2.2.1. VGG16

VGG16 is a 16-layer convolutional network developed by Oxford’s Visual Geometry Group [

41]. It consists of 13 convolutional layers and 3 dense layers, with max pooling used for downsampling. Known for its uniform architecture and effective performance in image classification tasks, VGG16 processes images through sequential convolutional blocks, followed by max pooling and fully connected layers. For this study, transfer learning was applied using the pretrained VGG16 base. A global average pooling layer and task-specific dense layers were added, resulting in over 15 million trainable parameters.

2.2.2. ResNet50

ResNet50 is a 50-layer deep convolutional network utilizing residual connections to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem [

42]. The architecture is divided into four stages of residual blocks, each consisting of convolutional layers, batch normalization, ReLU activation (as described in equations

1 and

2), and identity or projection shortcut connections. The skip connections allow the network to learn residual mappings, facilitating the training of deeper networks. For this study, the pretrained ResNet50 model was fine-tuned with a modified classifier tailored for the binary classification task [

42].

here,

Y is the output value for the input (

X) signal,

denotes the mean of the batch,

denotes the variance of the batch, and

is a small constant to prevent division by zero. Scale and offset are learnable parameters.

2.2.3. ConvNeXtTiny

ConvNeXtTiny is a compact convolutional neural network (CNN) optimized for efficient image recognition, particularly on resource-constrained devices [

43]. It follows the ConvNeXt architecture and balances performance with computational efficiency through staged blocks that use depthwise and point-wise convolutions, normalization layers, and activation functions [

43]. Down-sampling operations reduce spatial dimensions while increasing feature depth to capture complex patterns [

43]. In this study, the pre-trained ConvNeXtTiny model with ImageNet weights was customized by removing its fully connected layers, setting the input shape, and adding global average pooling and dense layers for binary classification. A final sigmoid-activated dense layer generates binary outputs. Training included callbacks for learning rate scheduling, checkpointing, and TensorBoard visualization, with the model compiled using the Adam optimizer, binary cross-entropy loss, and metrics such as accuracy, precision, and recall [

43].

2.2.4. MobileNetV2

MobileNet is a CNN architecture developed for mobile and edge devices with limited computational power [

44]. MobileNetV2, an enhanced version, is optimized for lightweight deep learning tasks in embedded vision applications. The model begins with a standard convolutional layer using 32 filters and a 3x3 kernel, followed by inverted residual blocks. Each block includes an expansion layer with 1x1 convolutions to increase channel depth and a depthwise convolution for efficient spatial filtering, as described in Equation

3.

MobileNetV2 uses 1x1 projection layers to reduce channel count and includes skip connections to support information flow. Bottleneck layers lower computational cost while preserving feature quality. The model ends with global average pooling and a dense layer for binary classification. Key improvements include linear bottlenecks, shortcut connections, and a lightweight block design, enhancing both efficiency and performance.

2.2.5. Custom CNN Model

Deep learning models can automatically extract imaging features to enhance task-specific performance [

45]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are the most widely applied in medical image processing [

46]. CNNs utilize convolutional layers that apply learned kernel functions across input images. This process, described by the equation:

here Y[i,j,k] represents the output feature map,

the learned kernel weights,

the input pixels, and

the bias term—enables task-adaptive feature extraction. Unlike fully connected networks, CNNs share kernel weights across spatial locations, reducing the number of trainable parameters and improving training efficiency [

45]. Pooling layers further reduce spatial dimensions and introduce translational invariance, supporting spatial feature hierarchy learning [

46].

To optimize model performance, we used Optuna, an open-source hyperparameter optimization framework that applies algorithms such as Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE), random search, and grid search. Optuna adjusts hyperparameters including learning rate (

to

, log scale), dropout rate (0–0.5), batch size (16, 32, 64), number of neurons (16–128), kernel size (1–5), activation functions (’relu’, ’sigmoid’, ’tanh’), and number of convolutional layers (1–3). In this study, two custom CNN models were developed and hyperparameter-optimized using Optuna. One of the models was trained using significantly fewer parameters than the other to assess performance differences under reduced model complexity. The search process used Bayesian optimization to explore hyperparameter combinations, stopping when three consecutive trials produced similar results. The best-performing configuration was selected for evaluation.

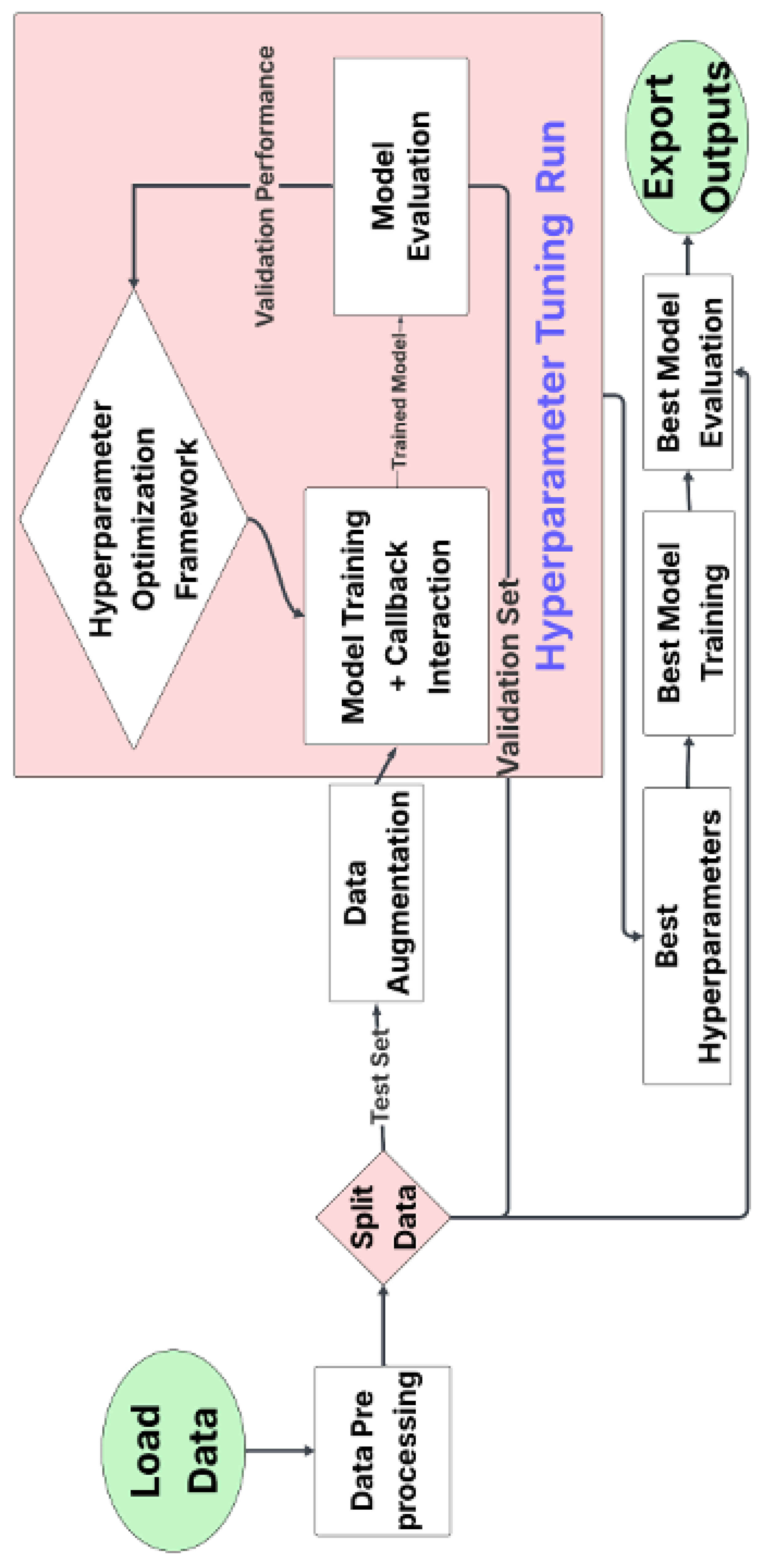

Figure 2 outlines the workflow, which begins with data preprocessing and augmentation, followed by dataset splitting (train, validation, test). During each iteration, models were trained with callbacks (e.g., early stopping), validated, and logged. Once optimal parameters were identified, the model was retrained and tested. Performance metrics and hyperparameters were recorded for further analysis.

3. Results

The study evaluated four pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—VGG16, ResNet50, MobileNetV2, and ConvNeXtTiny—against two custom-trained models optimized using Optuna hyperparameter tuning. This study addressed two main research questions: (a) whether pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNNs) outperform custom-trained models, and (b) whether models with fewer parameters yield better predictive performance.

Table 1.

Evaluation of pre-trained and custom models.

Table 1.

Evaluation of pre-trained and custom models.

| Metric |

VGG16 |

ResNet50 |

MobileNetV2 |

ConvNeXtTiny |

Optuna 1 |

Optuna 2 |

| Parameters |

15,241,025 |

25,686,913 |

3,570,753 |

28,608,609 |

13,537,047 |

1,162,177 |

| Train Loss |

0.1892 |

0.1084 |

0.0732 |

0.1193 |

0.0393 |

0.1209 |

| Train Accuracy |

0.9833 |

0.9538 |

0.9731 |

0.9528 |

0.9805 |

0.9615 |

| Train Precision |

0.9094 |

0.9477 |

0.9678 |

0.9557 |

0.8723 |

0.9635 |

| Train Recall |

0.99 |

0.88 |

0.98 |

1.00 |

0.9858 |

0.9615 |

| Train Specificity |

0.98 |

0.81 |

0.99 |

0.67 |

0.9828 |

0.9616 |

| Validation Loss |

0.3727 |

0.2973 |

0.3147 |

0.3306 |

0.4127 |

0.3758 |

| Validation Accuracy |

0.8716 |

0.9128 |

0.906 |

0.8807 |

0.8918 |

0.8846 |

| Validation Precision |

0.8273 |

0.8629 |

0.8321 |

0.7603 |

0.8891 |

0.8955 |

| Validation Recall |

0.89 |

0.85 |

0.88 |

0.99 |

0.8937 |

0.8824 |

| Validation Specificity |

0.87 |

0.74 |

0.91 |

0.54 |

0.8721 |

0.8871 |

| Test Loss |

0.2819 |

0.2427 |

0.2851 |

0.3114 |

0.395 |

0.3471 |

| Test Accuracy |

0.9174 |

0.922 |

0.922 |

0.9083 |

0.8028 |

0.8550 |

| Test Precision |

0.8593 |

0.8615 |

0.841 |

0.7973 |

0.8664 |

0.8413 |

| Test Recall |

0.94 |

0.87 |

0.95 |

1.00 |

0.8937 |

0.8548 |

| Test Specificity |

0.97 |

0.82 |

0.99 |

0.62 |

0.8721 |

0.8551 |

Among pre-trained models, MobileNetV2 achieved the lowest training loss (0.0732) and a high training accuracy of 0.9731. ResNet50 and VGG16 followed with accuracies of 0.9538 and 0.9833, respectively. The custom Optuna Model 1 yielded a lower training loss (0.0393) but had reduced precision (0.8723) compared to MobileNetV2 (0.9678). Validation accuracy was highest for ResNet50 (0.9128), followed by MobileNetV2 (0.906), and VGG16 (0.8716). Validation precision ranged from 0.7603 (ConvNeXtTiny) to 0.8955 (Optuna Model 2). ConvNeXtTiny achieved the highest recall (0.99) but had the lowest specificity (0.54). ResNet50 and MobileNetV2 both achieved the highest test accuracy (0.922). MobileNetV2 recorded the highest test recall (0.95) and specificity (0.99), with a precision of 0.841. ConvNeXtTiny had perfect test recall (1.00) but the lowest specificity (0.62). Among custom models, Optuna Model 2 achieved higher test accuracy (0.8550) than Optuna Model 1 (0.8028), despite having fewer parameters (1.16M vs. 13.54M).

MobileNetV2, with 3.57 million parameters, outperformed larger models such as ResNet50 (25.69 million) and ConvNeXtTiny (28.61 million). Optuna Model 2, the smallest model evaluated (1.16 million parameters), outperformed Optuna Model 1 (13.54 million) across most metrics.

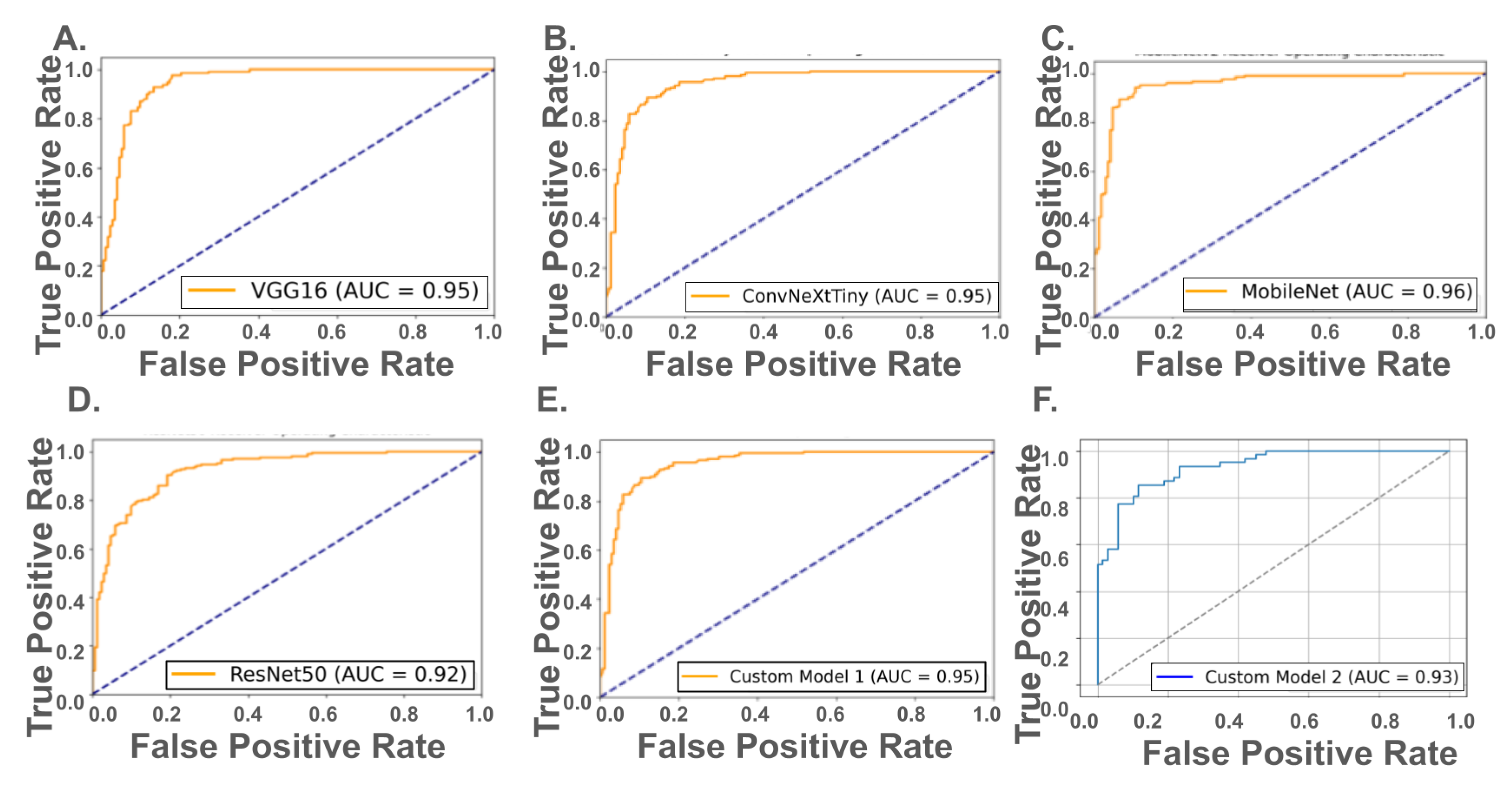

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis revealed strong discriminatory performance across both pretrained and custom models (

Figure 3, top and bottom panels). Among the pretrained networks, MobileNetV2 achieved the highest AUC of 0.96, followed closely by VGG16 and ConvNeXtTiny (AUC = 0.95), and ResNet50 (AUC = 0.92). For the custom hyperparameter-optimized CNNs, Model 1 (13.5 million parameters) achieved an AUC of 0.95, matching VGG16 and ConvNeXtTiny, while Model 2, with only 1.16 million parameters, maintained a relatively high AUC of 0.93. These results suggest that while pretrained models—particularly MobileNetV2—exhibit strong performance, well-optimized custom CNNs can achieve comparable ROC-based discrimination, even with significantly fewer trainable parameters.

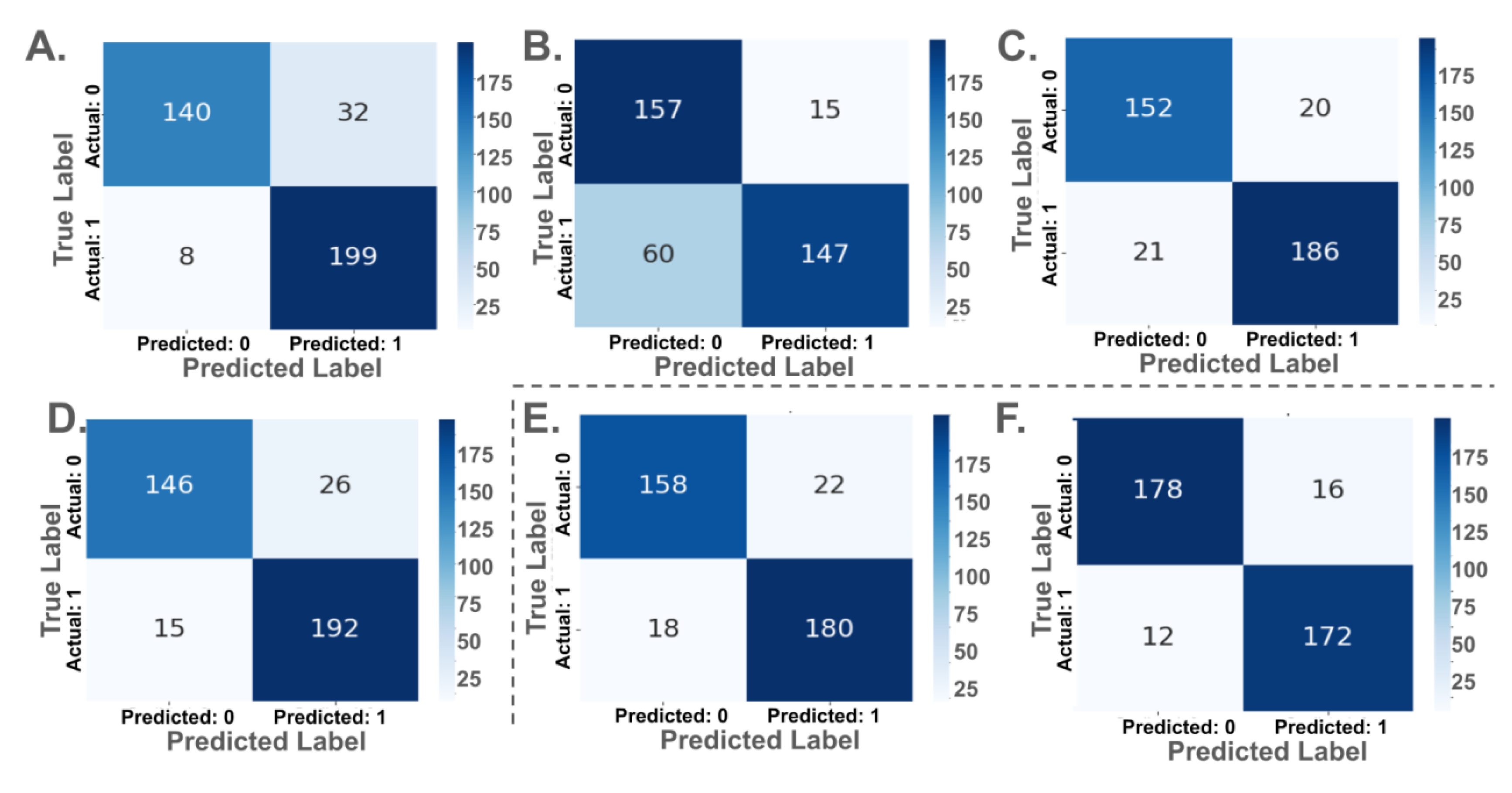

Confusion matrices for each model are presented in

Figure 4. Among pretrained models, MobileNetV2 yielded the highest true positive rate (TPR), correctly classifying 199 out of 207 ACC cases and 140 out of 172 normal cases. ConvNeXtTiny and VGG16 both demonstrated strong balanced performance, misclassifying 15 and 21 ACC cases, respectively. ResNet50, despite an AUC of 0.92, showed weaker specificity, with 60 false negatives.

Custom CNN Model 1 classified 180 of 198 ACC cases correctly and 158 of 180 normal cases, while Model 2, with fewer parameters, showed improved balance, correctly identifying 172 ACC and 178 normal cases. Model 2 recorded the fewest total misclassifications (28), despite having over ten times fewer parameters than ConvNeXtTiny or ResNet50.

Pre-trained models outperformed custom-trained models. ResNet50 and MobileNetV2 achieved the highest test accuracy (92.2%), followed by VGG16 (91.74%). Custom models performed lower, with Optuna Model 1 at 80.28% and Optuna Model 2 at 85.50%. Precision, recall, and specificity values were also higher in pre-trained models.

MobileNetV2 (3.57 million parameters) outperformed larger models, including ResNet50 (25.69 million) and ConvNeXtTiny (28.61 million), with the highest test recall (0.95) and specificity (0.99). ConvNeXtTiny, the largest model, had the lowest specificity (0.62). Optuna Model 2, the smallest model (1.16 million parameters), outperformed Optuna Model 1 (13.54 million), indicating improved performance with fewer parameters.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the classification performance of four widely used pre-trained CNN models (VGG16, ResNet50, MobileNetV2, and ConvNeXtTiny) in comparison with two custom-designed CNN models optimized using the Optuna hyperparameter tuning framework. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of transfer learning for MRI-based classification of ACC, with pre-trained models consistently outperforming custom architectures across most evaluation metrics.

Among the evaluated models, MobileNetV2 achieved the highest overall performance, with an AUC of 0.96, test recall of 0.95, and specificity of 0.99—all while maintaining a compact architecture with only 3.57 million parameters. VGG16 and ConvNeXtTiny also showed strong classification results (AUC = 0.95), though with significantly larger model sizes. ResNet50 attained a test accuracy of 92.2%, but its lower specificity and higher false-negative rate limited its diagnostic reliability.

The custom-trained models showed comparatively lower performance, though with noteworthy characteristics. Optuna Model 1 (13.54M parameters) achieved an AUC of 0.95 but had a lower test accuracy of 80.28%. In contrast, Optuna Model 2—designed for efficiency with only 1.16 million parameters—achieved a higher test accuracy (85.50%) and fewer misclassifications, along with the highest validation precision among all models (0.8955). Interestingly, parameter count did not correlate with improved performance. For instance, ConvNeXtTiny (28.61M) exhibited perfect recall but poor specificity (0.62), while the significantly smaller MobileNetV2 yielded more balanced and superior performance overall. Optuna Model 2’s performance, comparable to that of much larger architectures like VGG16 and ResNet50, further underscores the value of model efficiency in medical imaging applications.

These findings highlight the potential of transfer learning and lightweight, optimized architectures for accurate and resource-efficient classification in radiology. The results also suggest that smaller models, when properly tuned, can rival or exceed larger networks in predictive accuracy and generalizability.

We hope that this initial study provokes a wider interest in the field specifically in the following directions:

Extending the binary classification approach to distinguish between different stages or subtypes of ACC, as well as differentiating ACC from other adrenal pathologies.

Cross-Institutional Validation: Evaluating model performance on external datasets from different imaging centers to assess generalizability and reduce overfitting to a specific data source.

Integration with Clinical Metadata: Combining imaging data with clinical, biochemical, or genetic markers to improve predictive accuracy and support personalized diagnostic and treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors warmly acknowledge that all the memory intensive calculations were performed on the ManeFrame III computing system at Souther Methodist University. The authors gratefully acknowledge MDPI for the waiver of the article processing charge.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| ACC |

Adrenal Cortical Carncinoma |

References

- Libé, R. Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC): diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2015, 3, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thampi, A.; Shah, E.; Elshimy, G.; Correa, R. Adrenocortical carcinoma: a literature review. Translational Cancer Research 2020, 9, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libé, R.; Huillard, O. Adrenocortical carcinoma: Diagnosis, prognostic classification and treatment of localized and advanced disease. Cancer Treatment and Research Communications 2023, 37, 100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Halligan, S.; Hopewell, S.; Cornelius, V.; Altman, D.G. Systematic reviews of diagnostic tests in cancer: review of methods and reporting. Bmj 2006, 333, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krashin, E.; Piekiełko-Witkowska, A.; Ellis, M.; Ashur-Fabian, O. Thyroid hormones and cancer: a comprehensive review of preclinical and clinical studies. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barentsz, J.; Takahashi, S.; Oyen, W.; Mus, R.; De Mulder, P.; Reznek, R.; Oudkerk, M.; Mali, W. Commonly used imaging techniques for diagnosis and staging. Journal of clinical oncology 2006, 24, 3234–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuknecht, B. Diagnostic imaging–conventional radiology, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. In Osteomyelitis of the Jaws; Springer, 2009; pp. 57–94. [Google Scholar]

- Szolar, D.H.; Korobkin, M.; Reittner, P.; Berghold, A.; Hausegger, K.A.; Ballmer, P.E. Adrenal masses: Characterization with multiphasic CT protocol with 10-minute delay. Radiology 2005, 234, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlemmer, H.P.; Bittencourt, L.K.; D’Anastasi, M.; Domingues, R.; Khong, P.L.; Lockhat, Z.; Muellner, A.; Reiser, M.F.; Schilsky, R.L.; Hricak, H. Global challenges for cancer imaging. Journal of Global Oncology 2017, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Rini, B.I.; Zhang, H. Limitations of current imaging techniques in evaluating solid renal masses. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2018, 15, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobkin, M.; Brodeur, F.J.; Francis, I.R.; Quint, L.E.; Dunnick, N.R.; Londy, F. CT time-attenuation washout curves of adrenal adenomas and nonadenomas. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1998, 170, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourtsoyianni, S.; Papanikolaou, N.; Yarmenitis, S. Limitations and pitfalls of imaging techniques for adrenal lesion characterization. Imaging Med. 2015, 7, 523–536. [Google Scholar]

- Taffel, M.; Haji-Momenian, S.; Nikolaidis, P.; Miller, F.H. Adrenal imaging: a comprehensive review. Radiologic Clinics 2012, 50, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, G.W.; Dwamena, B.A.; Sangwaiya, M.J.; Goehler, A.G.; Francis, I.R. Characterization of adrenal masses using unenhanced CT: Initial work in 165 consecutive patients. Radiology 2008, 249, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, B.J.; Korfiatis, P.; Akkus, Z.; Kline, T.L. Machine learning for medical imaging. Radiographics 2017, 37, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toruner, M.D.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Bai, H. Artificial intelligence in radiology: where are we going? EBioMedicine 2024, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, A.; Parmar, C.; Quackenbush, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Aerts, H.J. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Nayak, D.R.; Balabantaray, B.K.; Tanveer, M.; Nayak, R. A survey on cancer detection via convolutional neural networks: Current challenges and future directions. Neural Networks 2024, 169, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Hu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Deep Learning for Medical Image-Based Cancer diagnosis, 2023.

- Molaeian, H.; Karamjani, K.; Teimouri, S.; Roshani, S.; Roshani, S. The Potential of Convolutional Neural Networks for Cancer Detection. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; Rios-Velazquez, E.; Leijenaar, R.; Carvalho, S.; van Stiphout, R.G.P.M.; Granton, P.; Zegers, C.M.L.; Gillies, R.; Boellard, R.; Dekker, A.; et al. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, W.L.; Hosny, A.; Schabath, M.B.; Giger, M.L.; Birkbak, N.J.; Mehrtash, A.; Lund, E.L.; Vu, T.N.; Aerts, H.J.; Mak, R.H. Artificial Intelligence in Cancer Imaging: Clinical Challenges and Applications. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassau, N.; Bousaid, I.; Chouzenoux, E.; Lamarque, J.P.; Charmettant, B.; Azoulay, M.; Cotton, F.; Khalil, A.; Lucidarme, O.; Pigneur, F.; et al. Three artificial intelligence data challenges based on CT and MRI. Diagn. Interventional Imaging 2020, 101, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Tang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Q. Deep learning for image-based cancer detection and diagnosis- A survey. Pattern Recogn. 2018, 83, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Emam, M.M.; Ali, A.A.; Suganthan, P.N. Deep and machine learning techniques for medical imaging-based breast cancer: A comprehensive review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 167, 114161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, T.A.; Zheng, L.; Afifi, A.J.; Ali, A.; Soomro, S.; Yin, M.; Gao, J. Image segmentation for MR brain tumor detection using machine learning: a review. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 16, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Dhalla, S.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, A. Automated analysis of blood smear images for leukemia detection: a comprehensive review. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUr) 2022, 54, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, S.; Tiwari, S.; Mothukuri, M.C.; Tangeda, C.M.; Nandigam, R.N.S.; Addagiri, D.C. A review on recent developments in cancer detection using machine learning and deep learning models. Biomed. Signal Proces. 2023, 80, 104398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, S.H.; Zhang, Y.D. A review of deep learning on medical image analysis. Mobile Networks and Applications 2021, 26, 351–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajera, H.K.; Nayak, D.R.; Zaveri, M.A. A comprehensive analysis of dermoscopy images for melanoma detection via deep CNN features. Biomed. Signal Proces. 2023, 79, 104186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Peralta, L.F.; Bote-Curiel, L.; Picon, A.; Sanchez-Margallo, F.M.; Pagador, J.B. Deep learning to find colorectal polyps in colonoscopy: A systematic literature review. Artificial intelligence in medicine 2020, 108, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, A.W.; Ahmed, A.; Fuentes, D.T.; Hazle, J.D.; Habra, M.A.; Elsayes, K.M. Machine learning based texture analysis for differentiation of radiologically indeterminate small adrenal tumors on adrenal protocol CT scans. Abdominal Radiology 2021, 46, 5529–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, A. Classification of brain tumors from MRI images using deep transfer learning. Journal of High School Science 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-Net: Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Volumetric Medical Image Segmentation. 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), 2016; 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, 2016; pp. 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; Leijenaar, R.T.; Deist, T.M.; Peerlings, J.; De Jong, E.E.; van Timmeren, J.; Sanduleanu, S.; Larue, R.T.; Even, A.J.; Jochems, A.; et al. Radiomics: The Bridge Between Medical Imaging and Personalized Medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kickingereder, P.; Burth, S.; Wick, A.; Götz, M.; Eidel, O.; Schlemmer, H.P.; Maier-Hein, K.H.; Wick, W.; Bendszus, M.; Radbruch, A. Radiomic Profiling of Glioblastoma: Identifying an Imaging Predictor of Patient Survival with Improved Performance over Established Clinical and Radiologic Risk Models. Radiology 2016, 280, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassnacht, M.; Dekkers, O.M.; Else, T.; Baudin, E.; Berruti, A.; De Krijger, R.R.; Haak, H.R.; Mihai, R.; Assie, G.; Terzolo, M. European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of adrenocortical carcinoma in adults, in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. European journal of endocrinology 2018, 179, G1–G46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE, 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp.

- Alo, M.; Baloglu, U.B.; Yıldırım, Ö.; Acharya, U.R. Application of deep transfer learning for automated brain abnormality classification using MR images. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2019, 54, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional neural networks: An overview and application in radiology. Insights into Imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).