Introduction

The enormous progress made in public health over the last century is traditionally attributed to the gradual introduction of numerous vaccines, which have helped to control, if not eradicate, the most serious and common infectious diseases, particularly those affecting children [

1,

2]. Given its past successes, vaccination has now become the undisputed panacea against infectious diseases and a medical paradigm that is virtually impossible to criticize in most Western countries, without being branded a conspiracy theorist [

3,

4], in particular for healthcare workers [

5,

6].

However, the authoritarian management of the recent Covidi19 epidemic and the sometimes clumsily aggressive pro-vaccine public health policies [

7], together with the unusual haste with which the most recent mRNA-based vaccines were put on the market [

8,

9,

10] prompted an increase in vaccine hesitancy, fueled by the continuous report of new adverse effects on social networks [

11,

12]

In parallel, puzzling case reports, unfortunately most of which published in low impact journals, have started to accumulate in the literature. For the most part, these reports are ignored (if not ridiculed) by the medical authorities, on the basis that most of these so-called adverse effects appear both weird and strictly individual [see for instance [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]]. If it is difficult to distinguish fanciful reports from those describing actual post-vaccination ailments, it is even more illusory to prove their causal link due to their irreproducibility. Except for the most immediate (e.g., allergic reactions), or the most recurring ones [e.g., [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]] for which a statistical signal is expected in large population studies [

23,

24], It is impossible to eliminate doubt in cases of virtually unique adverse events.

In this paper, rather than speculate about the reality of such diverse individual adverse effects, I rather ask the question: whether real or not, are they at least compatible with the immune response as we know it?

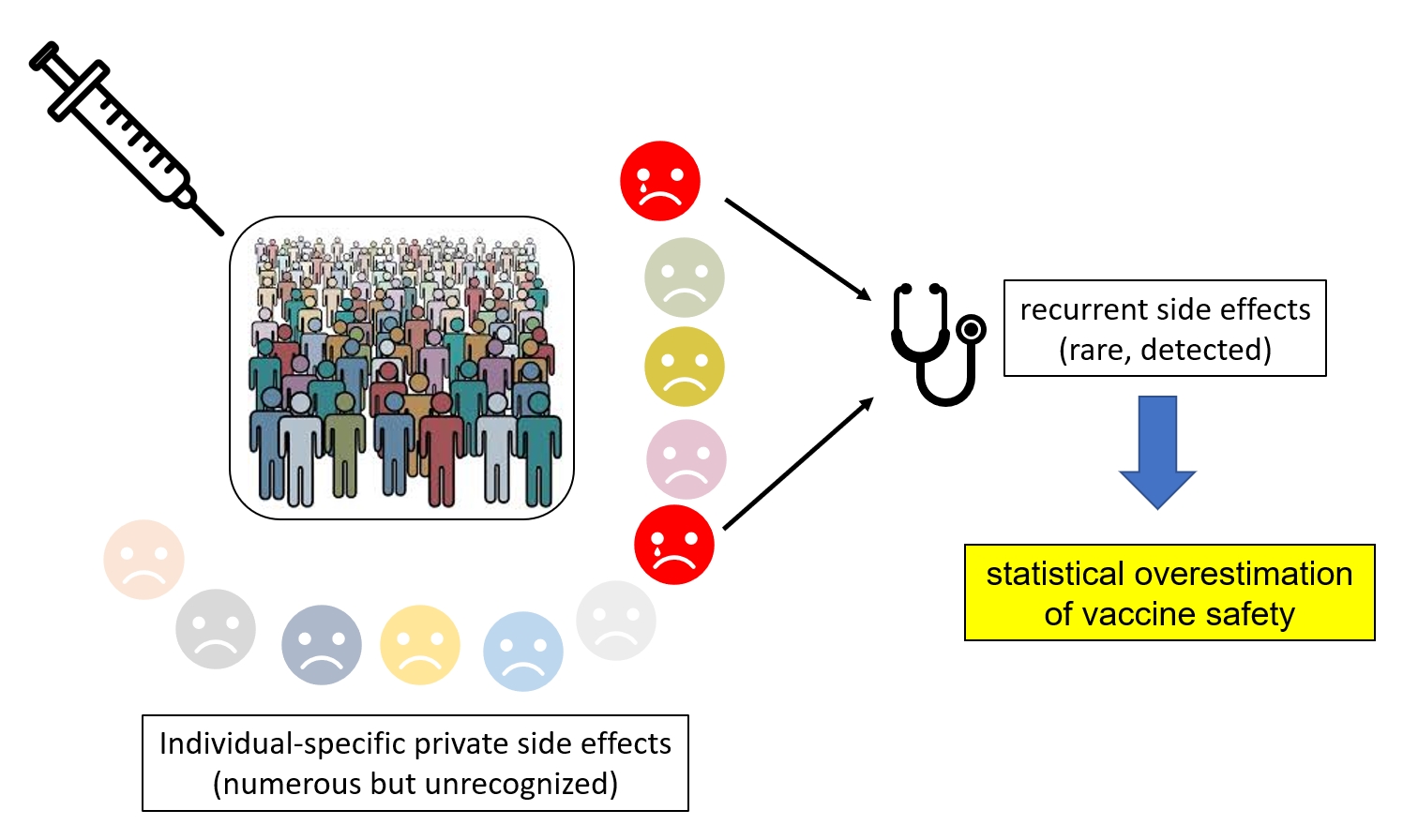

Answering positively leads me to propose the worrying hypothesis that vaccinations might frequently trigger autoimmune responses generating ailments whose extreme diversity makes it impossible, for statistical reasons, to attribute the cause to the vaccine. Only the most recurrent (i.e., common) side effects, yet expected to be rare given the individuality of the immune response, would be detectable, hence wrongly providing vaccination its undisputed reputation for extreme safety.

The sound scientific basis of this (admittedly provocative) hypothesis should justify a thorough re-examination of the merits of indiscriminate vaccination of the general population, at a time when the trend is to introduce its against diseases of lesser frequency or lethality or as a substitute for established drug-based curative therapies [e.g., [

25,

26]].

The Adaptive Immune Response: Key Features

The presentation of my hypothesis requires a basic knowledge of molecular immunology and of the basic principles governing the adaptive immune response. This section is therefore intended for readers with no prior knowledge of immunology.

The adaptive immune response is the the body’s defense reaction to the detection of specific macromolecules (mostly proteins) recognized as foreign (i.e., “non-self”), either originating from microbial pathogens or altered self-proteins (e.g., from mutated cancer cells). Any molecule capable of eliciting such a specific immune response is referred to as “antigen”.

This immune response is carried out by two sets of circulating white blood cells, engaged in a network of complex interactions differentially modulated by the presence of a heterogeneous set of soluble proteins, called interleukins (currently numbering up to 37) [

27].

One set consists of the antigen-presenting cells (APC) (among which macrophage, dendritic cells, and B cells) whose role is to convert antigens into fragments that are exposed on their surface.

The second set consists of specialized lymphocytes (T-cells) whose role is to recognize these antigens and trigger and/or perform different responses. For instance, CD8 + cytotoxic T-cells will kill the cells carrying the recognized antigen, while CD4+ helper T-cells will deliver a proliferative signal, for instance to the antibody producing B cells.

The two kinds of adaptive immune responses (cytotoxicity and antibody production) are thus mediated by the same central process, the formation of a peptide bridge between an antigen bearing cell, and a T-lymphocyte. However, this conceptual simplicity hides molecular details that are the very source of our biological individuality (and, in particular, our inability to tolerate transplants from each other).

Antigen Presentation: Two Different Kinds of MHC Molecules Interacting with Two Different Kind of T Cells

There are two kinds of MHC (for Major Histocompatibility Complex) molecules, quite similar in structure and function, but devoted to different physiological role. Class 1 MHC molecules are found at the surface of all nucleated cell types where they are presenting peptidic fragments derived from intracellularly synthetized proteins, either normal “self” proteins or foreign proteins produced by infecting pathogens (typically viruses).

The recognition of peptides presented by Class 1 MHC is restricted to the CD8 co-receptor-bearing cytotoxic T-cell (CD8+ T lymphocytes)). These peptides (Class1 restricted T cell epitopes) are typically 9 to 10 amino-acid long [

28].

In contrast, Class 2 MHC molecules are only expressed on professional antigen presenting cells (APC) cells, such as macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells, and B cells, and present peptidic fragments derived from internalized exogenous sources. The recognition of peptides presented by Class 2 MHC is restricted to the CD4 co-receptor-bearing T-cell (CD4+ “helper” T lymphocytes)). MHC class II presented peptides thereby are critical for the initiation of the antibody (humoral) immune response. These MHC class 2 restricted T cell epitopes are 12 to 20 amino-acid long [

29].

There are three pairs of MHC Class 1 genes in human (HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C) and three pairs of MHC Class II genes (HLA-DR, HLA-DP, and HLA-DQ) (HLA: Human Leukocyte Antigen). Each of these surface proteins are capable of binding different repertoires of peptides sharing identical (or similar) amino-acids at two “anchor” positions (usually near the peptide extremities). The large and very diverse peptide repertoire presented to a given individual’s immune system constitutes his “immunopeptidome” (Reviewed in [

30].

MHC/HLA Coding Genes Are Highly Polymorphic

For a given isotype (e.g., HLA A), and a given allele (e.g.,

HLA-A

∗02:07), the mono-allelic peptide repertoire may consist of up to 3500 unique “self” peptides [

31]. A fully heterozygous individual (expressing 3 class1 HLA and 3 class2 HLA different alleles) would thus be expected to present up to 21,000 different peptides for each class.

Importantly, the presentation of these peptides constitutes the basis of the immunological self/non-self-discrimination, by causing the deletion of self-reactive T-cells, first during their initial maturation in the thymus, or later on by contact with peripheric tolerogenic dendritic cells [

32].

As the size of this self-peptidome is approximately equal to the total number of proteins encoded in the human genome [

33], it theoretically predicts that each human proteins will only be represented by a one or two of peptides in average. In fact, a much smaller fraction of the human proteome is screened, as a large fraction of the presented peptides are only derived from abundant and/or high turnover proteins (some accounting for more than 1% of the total).

These numbers also suggests that the self-immunopeptidome is not large enough to include peptides originated from up to 200,000 alternatively spliced human mRNAs [

33]. Hence, a mutation, or a transient change in expression level or mRNA processing of a gene may potentially trigger an autoimmune response following the recognition of a new self-peptide following the lack of tolerization of cognate T cells (such as CD8+ cytotoxic T cell). Thus, only a partial set of human proteins participate to the definition of the immunological self through its selection by the class 1 and class 2 HLA alleles expressed by each individual.

For instance, the analyses of the immunopeptidomes of 18 individuals revealed that peptides bound to 27 highly prevalent HLA-I molecules were derived from only 10% of the expressed genome [

34]. Other studies indicate a total HLA-1 associated peptidome of no more than 5500 peptides [

35]. This allows for quite a big hole in the definition of the peptidic self, leaving wide open the possibility of autoreactivity.

Although crudely defined, this “peptide self” [

36] is highly variable and private to any given individual due to the extreme polymorphism of the presenting molecules: up to 200 alleles for each of the HLA loci with each allele being present at a relatively high frequency in the population. There are thus millions of possible HLA combinations, generating distinct immunopeptidomes providing each of us with a private landscape of the human proteome, despite its high sequence conservation within the human population (average 0.6% base pair variations, most of which are silent) [

37].

So, if we are all members of the same species and are made of extremely similar proteins, the vision of “selves” presented to the immune system is very unique to each individual across the population. The boundary between self and non-self is thus differently mapped within each of us, dynamically delineated by each individual immune system.

In the context of our private self, an infection by a given pathogen (or a vaccine mimicking it) will also result in the presentation of distinct subsets of foreign peptides, providing each individual immune system with a different molecular picture of the threat.

The polymorphism of the antigen presentation process is one of the main reasons (but not the only one - see below) why a challenge with the same antigen can produce a wide variety of individual responses [

38].

The Stochastic Generation of T Cell-Receptors and Antibody Specificities

Adaptive immune responses are triggered by the recognition of a presented peptide by a specific receptor (T-cell receptor, or TCR) expressed at the surface of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. The antigen-binding site of the TCR is generated by the random recombination of different gene segments (selected from a gene catalog at the V, J and D loci), the addition of random nucleotides at their splicing sites, and somatic mutations (reviewed in [

39]). A similar random generation process (although at a different genomic locus) is used to generate the antibodies expressed and secreted by B-cells upon their activation by CD4+ T-cells (reviewed in [

40])

In consequence, and given the almost infinite number of different TCRs that can be generated by this combinatorial process, one cannot expect two different individuals (including identical twins) to produce identical reactive T-cells (or antibodies) against a given antigen, even though they would bind the same presented peptide (for T-cell) or the same epitope (for B-cells).

In addition to the polymorphic antigen presentation process, this is the second main reason why a challenge with the same antigen will again produce a wide variety of individual responses. These responses could both differ in intensity [

41,

42] or by the targeted epitope [

43].

The Looming Danger of Autoimmunity

Without dwelling on the detailed molecular processes governing the synthesis of TCRs or antibodies, which are for the most part well elucidated, we shall retain only one concept that is central to the rest of our discussion: the affinity of TCRs or antibodies for a given antigen is fortuitous, and does not result from any prior interaction with it. This affinity only manifests itself a posteriori, among all the naïve T-cells that have not been eliminated following their confrontation with the self-immunopeptidome.

As the initial affinity of a TCR for an antigen is not the result of a selection process, there is no reason why their interaction should be particularly strong or specific. This has been experimentally confirmed. For instance, It has been shown that a single peptide–MHC class II complex positively selects at least 10

5 different TCR (defined by different Vβ variable gene rearrangements) [

44]. Among these TCR, many will also display a functional affinity (i.e., trigger the activation of the corresponding T cell) for a large spectrum of unrelated peptides [

45]. Experimentally, a single TCR has been shown to recognize more than a million peptides [

46]. This was to be expected, given that the universe of potential antigens is orders of magnitude larger than the number of unique TCRs in an individual, necessitating a highly cross-reactive TCR repertoire [

47,

48].

Therefore, the proliferation of each T-cell clone triggered by any natural or vaccine-induced immune response intrinsically carries the risk of triggering autoimmunity, the target of which is both unpredictable and possibly strictly individual. Autoimmunity will then manifest itself through a wide variety of detrimental processes. Auto-antibody (promoted by self-reactive CD4+ helper T cells) [

49] can bind and inhibit key enzymatic functions, interfere with hormonal signaling by binding to ligands or receptors, or interfere with the activation of different cell-types by binding to surface proteins. Self-reactive cytotoxic CD8+ T cells will start killing specific cell types impairing their normal biochemical, regulatory or structural functions in various tissues or organs [e.g., [

50]].

However, and in stark contrast with drug-induced adverse side effects, which tend to be reproducible among categories of individual sharing similar metabolic characteristics (and/or genetic background), immunologically-induced adverse effects are expected to be extremely diverse, eventually unique (“private”) to a single individual due to the multiple stochastic processes governing the immune response described above. This raises the worrying possibility that the strong immunization triggered by vaccinations might not be as innocuous as it has been presented for years, as to become one of the most unassailable medical paradigms.

Our Hypothesis: All Vaccinations Might Be the Cause of a Multitude of Unrecognized Patient-Specific Adverse Effects

The excellent reputation of vaccines is inferred from their efficacy against the various targeted infectious diseases and the rarity of recurrent adverse effects (that is with identical manifestations in different people). However, I hypothesize that the rarity of these “public” adverse events (expected from the stochastic nature of the immune response) could conceal a much higher (cumulative) frequency of “private” vaccine accidents that remain statistically undetectable due to their non-reproducible occurrence within the vaccinated population.

In absence of a significant statistical signal, these private ailments, even when duly reported to the vaccine adverse event reporting systems (VAERS), end up interpreted as mere coincidences with no connection to the vaccination process other than temporal.

Most of these reports will end up being published on social networks [

11,

12] by the patients themselves, without any way of assessing their veracity. Others will be published as isolated case reports in low-quality scientific journals (e.g., [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]), and in the worst case, will be branded as ‘fake news’ deliberately propagated by “anti-vax” conspiracy theorists.

Given the extreme diversity of the reported post-vaccination symptoms, ranging from simple itching and headaches, to severe allergic reactions, neurological manifestations, cardiovascular conditions, up to the eventual triggering of various cancers or autoimmune diseases, it is difficult for today’s medical profession, compartmentalized into its various specialties, to assume and search for a common etiology, at the risk of undermining the pillar of public health policy that vaccination has become.

Moreover, despite its huge progresses during the last 40 years, it could be argued that immunology has not thus far contributed much to vaccine development, in that most of the vaccines we use today were developed and tested empirically [

26]. The principle of vaccination and its generalized use largely predate our detailed understanding of the processes governing the different types of immune responses, and their intricate regulation by multiple interleukins (reviewed in [

51]). An update to our knowledge could have prompted a reassessment of the risks associated with vaccination, but this has not yet happened. Vaccination it is a complex phenomenon involving the interaction of numerous cell types in distinct compartments all within a systemic context shaped by the history of an individual’s immune stimuli. Such a complex biological system is expected to exhibit two properties: 1) it cannot function without randomly generating some errors [

52], and 2) its operation results in different physiological states that reflect the spectrum of individual physiological and genetic variations within populations [

53]. This last point highlights the paradox of vaccinating populations according to uniform protocols rather than making vaccination an archetype of personalized medicine. Fortunately, “vaccinomics” has now emerged as a new research area dedicated to the understanding the heterogeneity in vaccine immune response [

54].

What we now know about the immune system works, predicts that recurrent (i.e., public) adverse effects should be rare. They could, for example, involve individuals sharing mutations of various immune system components [

55,

56], sharing detrimental HLA alleles (e.g., [

57,

58,

59]), and/or expressing rare public self-reactive TCRs [

60,

61,

62]. These features may overlap with to those increasing the severity of common infectious diseases [

23,

63,

64,

65].

In contrast, private adverse effects could originate from every unique combination of slight genome/proteome variation, rare HLA haplotypes (and the corresponding immunopeptidome), and the stochastic selection/expression of totally private TCRs one of which could inadvertently lead to autoimmunity. Many studies have also shown that the immune response is error prone, autoimmunity being frequently observed following repetitive (hyper) immunization as caused by the multiplication of booster shots [

49,

66,

67].

After years of neglecting research into the mechanisms behind the adverse effects of vaccinations, a new generation of immunologists seems at last to be taking an interest [

23].

Unfortunately, only statistically proven, - that is the most frequent-, recurrent adverse effects will be targeted by those vaccinomics studies.

On the other hand, the study of isolated unique adverse events in vaccinated populations poses a fundamental methodological problem, as similar repeated observations of a given phenomenon are at the very basis of the scientific approach. Without the ability to analyze several independent occurrences of the same adverse events, it seems impossible to distinguish a mere simple coincidence from a causal link with vaccination. Although derived from well-established properties of the immune system, our hypothesis could therefore be considered unfalsifiable and therefore unscientific. However, symmetrically, the safety of vaccination then becomes similarly undecidable.

However, even in the absence of repetitions, the analysis of a series of strictly individual adverse events could give rise to concordant clues, albeit without providing a formal proof. For instance, patients with suspected post-vaccination complications could systematically be tested for the presence of anti-nuclear antibodies, considered a recurrent sign of autoimmunity against a broad range of self-antigens. Proteome-wide screening methodologies could then be used to identify new autoantibody against unrecognized autoantigens [

68]. Unfortunately, the identification of the autoantigen targeted by autoreactive CD4+ or CD8+ T cell on a large scale remains challenging [

69].

Past confidence in the safety of vaccines has meant that no significant changes have been made to the structure of clinical trials for new vaccines. First, a vaccinal antigen is designed as to trigger a strong production of neutralizing antibodies, with little or no analysis of the concomitant cellular response. The immunization is then tested (Phase III) on a relatively large cohort (≈30.000) for its global efficacy in preventing the cognate disease and estimating the frequency of serious (recurrent) adverse effects.

No measurement is made of the variability of individual immune responses and their eventual links with the genotypic characteristics of patients (or even their HLA haplotypes). Moreover, the period dedicated to the monitoring of eventual adverse effects (e.g., sometimes shorter that 6 months [

9,

70]) is not compatible with the usually long incubation period of autoimmune diseases, hence not suited to invalidate our hypothesis.

There are already some serious criticisms about the insufficiency of vaccine clinical trial [

70,

71], some of which reactivated by the rushing of SARS-CoV2 vaccines [

8,

73]. Yet, these criticisms are targeting specific methodological weaknesses without globally questioning the immaculate reputation of efficacy and safety acquired by vaccination since the last century.

Nevertheless, the history of medicine is full of examples of therapeutic approaches that were once universally praised but are now abandoned or even considered dangerous nowadays (e.g., over the counter drugs such as codeine and aspirin, prophylactic appendectomy, prophylactic tonsillectomies, arsenic-based drug to treat syphilis, etc.).

In this article, I suggested that the detailed knowledge we now have of the immune system should lead us to rigorously reassess the benefit/risk ratio of vaccination, which is currently considered unassailable. Pending this reassessment, promoting a more personalized use of vaccines by developing vaccinomics [

74] and limiting their use against the most serious (deadly) diseases seems to be the most rational attitude.

References

- Montero, D.A.; Vidal, R.M.; Velasco, J.; Carreño, L.J.; Torres, J.P.; Benachi, O.M.A.; Tovar-Rosero, Y.Y.; Oñate, A.A.; O’Ryan, M. Two centuries of vaccination: historical and conceptual approach and future perspectives. Front Public Health. 2024, 11, 1326154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Control of infectious diseases. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999, 48, 621–629. [PubMed]

- Clark, S.E.; Bledsoe, M.C.; Harrison, C.J. The role of social media in promoting vaccine hesitancy. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2022, 34, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertwee, E.; Simas, C.; Larson, H.J. An epidemic of uncertainty: rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nat Med. 2022, 28, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyerdahl, L.W.; Dielen, S.; Nguyen, T.; Van Riet, C.; Kattumana, T.; Simas, C.; Vandaele, N.; Vandamme, A.M.; Vandermeulen, C.; Giles-Vernick, T.; Larson, H.; Grietens, K.P.; Gryseels, C. Doubt at the core: Unspoken vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022, 12, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, N.; Mustapha, T.; Khubchandani, J.; Price, J.H. The Nature and Extent of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in Healthcare Workers. J Community Health. 2021, 46, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardosh, K.; de Figueiredo, A.; Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Doidge, J.; Lemmens, T.; Keshavjee, S.; Graham, J.E.; Baral, S. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Glob Health. 2022, 7, e008684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doshi, P. Will covid-19 vaccines save lives? Current trials aren’t designed to tell us. BMJ. 2020, 371, m4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Perez JL, Pérez Marc G, Moreira ED, Zerbini C, Bailey R, Swanson KA, Roychoudhury S, Koury K, Li P, Kalina WV, Cooper D, Frenck RW Jr, Hammitt LL, Türeci Ö, Nell H, Schaefer A, Ünal S, Tresnan DB, Mather S, Dormitzer PR, Şahin U, Jansen KU, Gruber WC; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thacker, P.D. Covid-19: Researcher blows the whistle on data integrity issues in Pfizer’s vaccine trial. BMJ. 2021, 375, n2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khullar, D. Social Media and Medical Misinformation: Confronting New Variants of an Old Problem. JAMA. 2022, 328, 1393–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, M.R.; Desai, N.; Namazi, A.; Leas, E.; Dredze, M.; Smith, D.M.; Ayers, J.W. Characteristics of X (Formerly Twitter) Community Notes Addressing COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation. JAMA. 2024, 331, 1670–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, Y.; Yamanaka, Y.; Oda, A. Otitis Media with ANCA-Associated Vasculitis Following COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2024, 25, e945301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, M.; Uchimura, K.; Ohkoshi, K.; Saegusa, N.; Osano, K.; Yoshida, S.; Konishi, M.; Ishii, T.; Takahashi, K.; Nakashima, A. A Severe Case of Rhabdomyolysis Requiring Renal Replacement Therapy Following COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination. Intern Med. 2025, 64, 1547–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckerman, J.K.; Yaghi, O.; Nassereddine, S. Acquired haemophilia A following COVID-19 vaccine. BMJ Case Rep. 2025, 18, e263299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Ding, W.; Song, H.; Wang, D. Unique skin nodules following COVID-19 vaccination: a case report of cutaneous plasmacytosis and review of the literature. Virol J. 2025, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalfardi, B.; Rad, N.K.; Mohammad Alizade, T.; Edalatifard, M.; Asadi, S.; Rahimi, B. Unexpected hypereosinophilia after Sinopharm vaccination: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2025, 25, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamprinou, M.; Sachinidis, A.; Stamoula, E.; Vavilis, T.; Papazisis, G. COVID-19 vaccines adverse events: potential molecular mechanisms. Immunol Res. 2023, 71, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasmin, F.; Najeeb, H.; Naeem, U.; Moeed, A.; Atif, A.R.; Asghar, M.S.; Nimri, N.; Saleem, M.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Krittanawong, C.; Fadelallah Eljack, M.M.; Tahir, M.J.; Waqar, F. Adverse events following COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: A systematic review of cardiovascular complication, thrombosis, and thrombocytopenia. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023, 11, e807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, N.; Itani, M.; Aoki, T.; Sakurai, A.; Fujisawa, T.; Okada, Y.; Noda, K.; Arakawa, Y.; Tokuda, S.; Tanikawa, R. Expression of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in cerebral Arteries: Implications for hemorrhagic stroke Post-mRNA vaccination. J Clin Neurosci. 2025, 136, 111223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Joseph, H.; Raz, Y.; Eldar-Boock, A.; Michaan, N.; Angel, Y.; Saiag, E.; Nemerovsky, L.; Ben-Ami, I.; Shalgi, R.; Grisaru, D. The direct effect of SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccination on human ovarian granulosa cells explains menstrual irregularities. NPJ Vaccines. 2024, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faksova, K.; Walsh, D.; Jiang, Y.; Griffin, J.; Phillips, A.; Gentile, A.; Kwong, J.C.; Macartney, K.; Naus, M.; Grange, Z.; Escolano, S.; Sepulveda, G.; Shetty, A.; Pillsbury, A.; Sullivan, C.; Naveed, Z.; Janjua, N.Z.; Giglio, N.; Perälä, J.; Nasreen, S.; Gidding, H.; Hovi, P.; Vo, T.; Cui, F.; Deng, L.; Cullen, L.; Artama, M.; Lu, H.; Clothier, H.J.; Batty, K.; Paynter, J.; Petousis-Harris, H.; Buttery, J.; Black, S.; Hviid, A. COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine. 2024, 42, 2200–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolze A, Mogensen TH, Zhang SY, Abel L, Andreakos E, Arkin LM, Borghesi A, Brodin P, Hagin D, Novelli G, Okada S, Peter J, Renia L, Severe K, Tiberghien P, Vinh DC; COVID human genetic effort; Cirulli ET, Casanova JL, Hsieh EWY. Decoding the Human Genetic and Immunological Basis of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine-Induced Myocarditis. J Clin Immunol. 2022 Oct;42(7):1354-1359. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, M.Z.; Gerber, J.E.; Budigan Ni, H.; Blunt, M.; Holroyd, T.A.; Carleton, B.C.; Poland, G.A.; Salmon, D.A. Vaccinomics: A scoping review. Vaccine. 2023, 41, 2357–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chaudhary, N.; Weissman, D.; Whitehead, K.A. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Not immunePollard, A.J.; Bijker, E.M. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021, 21, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, N.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L. The stress and the alarmin-like cytokine interleukin-37 mediated extracellular and intracellular signal pathways. Semin Immunol. 2025, 78, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trolle, T.; McMurtrey, C.P.; Sidney, J.; Bardet, W.; Osborn, S.C.; Kaever, T.; Sette, A.; Hildebrand, W.H.; Nielsen, M.; Peters, B. The Length Distribution of Class I-Restricted T Cell Epitopes Is Determined by Both Peptide Supply and MHC Allele-Specific Binding Preference. J Immunol. 2016, 196, 1480–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLachlan, B.J.; Dolton, G.; Papakyriakou, A.; Greenshields-Watson, A.; Mason, G.H.; Schauenburg, A.; Besneux, M.; Szomolay, B.; Elliott, T.; Sewell, A.K.; Gallimore, A.; Rizkallah, P.; Cole, D.K.; Godkin, A. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II peptide flanking residues tune the immunogenicity of a human tumor-derived epitope. J Biol Chem. 2019, 294, 20246–20258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, A.; Winiarek, G.; Hołówka, O.; Godlewski, J.; Bronisz, A. Unlocking the secrets of the immunopeptidome: MHC molecules, ncRNA peptides, and vesicles in immune response. Front Immunol. 2025, 16, 1540431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelin, J.G.; Keskin, D.B.; Sarkizova, S.; Hartigan, C.R.; Zhang, W.; Sidney, J.; Stevens, J.; Lane, W.; Zhang, G.L.; Eisenhaure, T.M.; Clauser, K.R.; Hacohen, N.; Rooney, M.S.; Carr, S.A.; Wu, C.J. Mass Spectrometry Profiling of HLA-Associated Peptidomes in Mono-allelic Cells Enables More Accurate Epitope Prediction. Immunity. 2017, 46, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Hogquist, K.A. T-cell tolerance: central and peripheral. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012, 4, a006957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, P.; Carbonell-Sala, S.; De La Vega, F.M.; Faial, T.; Frankish, A.; Gingeras, T.; Guigo, R.; Harrow, J.L.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G.; Johnson, R.; Murphy, T.D.; Pertea, M.; Pruitt, K.D.; Pujar, S.; Takahashi, H.; Ulitsky, I.; Varabyou, A.; Wells, C.A.; Yandell, M.; Carninci, P.; Salzberg, S.L. The status of the human gene catalogue. Nature. 2023, 622, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, S.; Ternette, N. Know thy immune self and non-self: Proteomics informs on the expanse of self and non-self, and how and where they arise. Proteomics. 2021, 21(23-24):e2000143. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassani-Sternberg, M.; Pletscher-Frankild, S.; Jensen, L.J.; Mann, M. Mass spectrometry of human leukocyte antigen class I peptidomes reveals strong effects of protein abundance and turnover on antigen presentation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015, 14, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourilsky, P.; Chaouat, G.; Rabourdin-Combe, C.; Claverie, J.M. Working principles in the immune system implied by the “peptidic self” model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987, 84, 3400–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium; Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, Marchini JL, McCarthy S, McVean GA, Abecasis GR. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015 Oct 1;526(7571):68-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Mothe, B.; Alcalde Herraiz, M.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Jödicke, A.M.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, S.; Wei, J.; Chen, Z.; Hong, S.; Wu, Y.; Su, B.; Zheng, X.; Cohet, C.; Ali, R.; Wareham, N.; Alhambra, D.P. Relationship between HLA genetic variations, COVID-19 vaccine antibody response, and risk of breakthrough outcomes. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, N.P. Numbers and odds: TCR repertoire size and its age changes impacting on T cell functions. Semin Immunol. 2023, 69, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dai, H.Q.; Hu, H.; Alt, F.W. The role of chromatin loop extrusion in antibody diversification. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022, 22, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heiden, M.; Shetty, S.; Bijvank, E.; Beckers, L.; Cevirgel, A.; van Sleen, Y.; Tcherniaeva, I.; Ollinger, T.; Burny, W.; van Binnendijk, R.S.; van Houten, M.A.; Buisman, A.M.; Rots, N.Y.; van Beek, J.; van, B. Multiple vaccine comparison in the same adults reveals vaccine-specific and age-related humoral response patterns: an open phase IV trial. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karp-Tatham, E.; Knight, J.C.; Bolze, A. Human genetics of responses to vaccines. Clin Exp Immunol. 2025 May 21, uxaf034. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Kolesnikov, A.; Yin, R.; Guest, J.D.; Gowthaman, R.; Shmelev, A.; Serdyuk, Y.; Dianov, D.V.; Efimov, G.A.; Pierce, B.G.; Mariuzza, R.A. Structural assessment of HLA-A2-restricted SARS-CoV-2 spike epitopes recognized by public and private T-cell receptors. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gapin, L.; Fukui, Y.; Kanellopoulos, J.; Sano, T.; Casrouge, A.; Malier, V.; Beaudoing, E.; Gautheret, D.; Claverie, J.M.; Sasazuki, T.; Kourilsky, P. Quantitative analysis of the T cell repertoire selected by a single peptide-major histocompatibility complex. J Exp Med. 1998, 187, 1871–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignatowicz, L.; Rees, W.; Pacholczyk, R.; Ignatowicz, H.; Kushnir, E.; Kappler, J.; Marrack, P. T cells can be activated by peptides that are unrelated in sequence to their selecting peptide. Immunity. 1997, 7, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, L.; Ekeruche-Makinde, J.; van den Berg, H.A.; Skowera, A.; Miles, J.J.; Tan, M.P.; Dolton, G.; Clement, M.; Llewellyn-Lacey, S.; Price, D.A.; Peakman, M.; Sewell, A.K. A single autoimmune T cell receptor recognizes more than a million different peptides. J Biol Chem. 2012, 287, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, D. A very high level of crossreactivity is an essential feature of the T-cell receptor. Immunol Today. 1998, 19, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewell, A.K. Why must T cells be cross-reactive? Nat Rev Immunol. 2012, 12, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchi, M.C.; Pelazza, C.; Bertolotti, M.; Agatea, L.; De Gaspari, P.; Tamiazzo, S.; Ielo, D.; Stobbione, P.; Grappiolo, M.; Bolgeo, T.; Novel, P.; Ciriello, M.M.; Maconi, A. The onset of de novo autoantibodies in healthcare workers after mRNA based anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a single centre prospective follow-up study. Autoimmunity. 2023, 56, 2229072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, I.; Freeman, S.A.; Saoudi, A.; Liblau, R. Infection, vaccination and narcolepsy type 1: Evidence and potential molecular mechanisms. J Neuroimmunol. 2024, 393, 578383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C. Cytokine Regulation and Function in T Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021, 39, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.M.; Katsumata, M.; Komori, S.; Wadsworth, S.; Gill-Morse, L.; Jerrold-Jones, S.; Bhandoola, A.; Greene, M.I.; Yui, K. Mechanisms of autoimmunity in the context of T-cell tolerance: insights from natural and transgenic animal model systems. Immunol Rev. 1990, 118, 165–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, M.Z.; Gerber, J.E.; Budigan Ni, H.; Blunt, M.; Holroyd, T.A.; Carleton, B.C.; Poland, G.A.; Salmon, D.A. Vaccinomics: A scoping review. Vaccine. 2023, 41, 2357–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland, G.A.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Jacobson, R.M.; Smith, D.I. Heterogeneity in vaccine immune response: the role of immunogenetics and the emerging field of vaccinomics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007, 82, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A.V. The immunogenetics of human infectious diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998, 16, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.P.; Caballero-Oteyza, A.; Grimbacher, B. Common Variable Immunodeficiency: More Pathways than Roads to Rome. Annu Rev Pathol. 2023, 18, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, I.; Freeman, S.A.; Saoudi, A.; Liblau, R. Infection, vaccination and narcolepsy type 1: Evidence and potential molecular mechanisms. J Neuroimmunol. 2024, 393, 578383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trowsdale, J.; Knight, J.C. Major histocompatibility complex genomics and human disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013, 14, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, R.; Kollnberger, S.; Mellins, E.D. HLA associations in inflammatory arthritis: emerging mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ria, F.; van den Elzen, P.; Madakamutil, L.T.; Miller, J.E.; Maverakis, E.; Sercarz, E.E. Molecular characterization of the T cell repertoire using immunoscope analysis and its possible implementation in clinical practice. Curr Mol Med. 2001, 1, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Garner, L.I.; Zvyagin, I.V.; Paley, M.A.; Komech, E.A.; Jude, K.M.; Zhao, X.; Fernandes, R.A.; Hassman, L.M.; Paley, G.L.; Savvides, C.S.; Brackenridge, S.; Quastel, M.N.; Chudakov, D.M.; Bowness, P.; Yokoyama, W.M.; McMichael, A.J.; Gillespie, G.M.; Garcia, K.C. Autoimmunity-associated T cell receptors recognize HLA-B*27-bound peptides. Nature. 2022, 612, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Mariuzza, R.A. Structural basis for self-recognition by autoimmune T-cell receptors. Immunol Rev. 2012, 250, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Voyer, T.; Maglorius Renkilaraj, M.R.L.; Moriya, K.; Pérez Lorenzo, M.; Nguyen, T.; Gao, L.; Rubin, T.; Cederholm, A.; Ogishi, M.; Arango-Franco, C.A.; Béziat, V.; Lévy, R.; Migaud, M.; Rapaport, F.; Itan, Y.; Deenick, E.K.; Cortese, I.; Lisco, A.; Boztug, K.; Abel, L.; Boisson-Dupuis, S.; Boisson, B.; Frosk, P.; Ma, C.S.; Landegren, N.; Celmeli, F.; Casanova, J.L.; Tangye, S.G.; Puel, A. Inherited human RelB deficiency impairs innate and adaptive immunity to infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024, 121, e2321794121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Casanova, J.L.; Boisson, B. Genetics and clinical phenotypes in common variable immunodeficiency. Front Genet. 2024, 14, 1272912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, J.L.; Abel, L. From rare disorders of immunity to common determinants of infection: Following the mechanistic thread. Cell. 2022, 185, 3086–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świerkot, J.; Madej, M.; Szmyrka, M.; Korman, L.; Sokolik, R.; Andrasiak, I.; Morgiel, E.; Sebastian, A. The Risk of Autoimmunity Development following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination. Viruses. 2022, 14, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, J.T.; Luján, L.; Blank, M.; Shoenfeld, Y. Adjuvants- and vaccines-induced autoimmunity: animal models. Immunol Res. 2017, 65, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, S.E.; Ferré, E.M.; Scheel, D.W.; Sunshine, S.; Miao, B.; Mandel-Brehm, C.; Quandt, Z.; Chan, A.Y.; Cheng, M.; German, M.; Lionakis, M.; DeRisi, J.L.; Anderson, M.S. Identification of novel, clinically correlated autoantigens in the monogenic autoimmune syndrome APS1 by proteome-wide PhIP-Seq. Elife. 2020, 9, e55053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, M.; Acosta-Ampudia, Y.; Heuer, L.S.; Zang, W.; MMonsalve, D.; Ramírez-Santana, C.; Anaya, J.M.; MRidgway, W.; AAnsari, A.; Gershwin, M.E. Antigen-specific T cells and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2024, 148, 103303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenck RW Jr, Klein NP, Kitchin N, Gurtman A, Absalon J, Lockhart S, Perez JL, Walter EB, Senders S, Bailey R, Swanson KA, Ma H, Xu X, Koury K, Kalina WV, Cooper D, Jennings T, Brandon DM, Thomas SJ, Türeci Ö, Tresnan DB, Mather S, Dormitzer PR, Şahin U, Jansen KU, Gruber WC; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group. Safety, Immunogenicity, and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine in Adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021, 385, 239–250. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, D.A.; Orenstein, W.A.; Plotkin, S.A.; Chen, R.T. Funding Postauthorization Vaccine-Safety Science. N Engl J Med. 2024, 391, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, M.Z.; Halsey, N.A.; Omer, S.B.; Orenstein, W.A.; O’Leary, S.T.; Limaye, R.J.; Salmon, D.A. The state of vaccine safety science: systematic reviews of the evidence. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020, 20, e80–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Dudley, M.Z.; Chen, X.; Bai, X.; Dong, K.; Zhuang, T.; Salmon, D.; Yu, H. Evaluation of the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid review. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Eitan, L.N.; ElMotasem, M.F.M.; Khair, I.Y.; Alahmad, S.Z. Vaccinomics: Paving the Way for Personalized Immunization. Curr Pharm Des. 2024, 30, 1031–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).