Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

3. Quantum Mechanisms in Structured Water

4. Water, Electromagnetic Fields, and Proton Tunneling

5. IDPs and Hydration Water Dynamics

6. Age-Related Breakdown of Hydration Coherence in IDPs

7. Expanded Insights into HSF1 Regulation via Hydration-Sensitive Mechanisms

8. EMF Studies in Cell Cultures and Animals

8.1. Studies in Cell Cultures

8.1.1. Studies in Animal and Human Immortalized Cell Cultures

8.1.2. Primary Human Cultures

8.2. Preliminary Findings from Animal Studies

9. Discussion and Implications for Quantum Biology and Therapeutics

10. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kinsey, L.J.; Beane, W.S.; Tseng, K.A.-S. Accelerating an integrative view of quantum biology. Front. Physiol. 2024, 14, 1349013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwa, H.; Babcock, N.S.; Kurian, P. Quantum-enhanced photoprotection in neuroprotein architectures emerges from collective light-matter interactions. Front. Phys. 2024, 12, 1387271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Otten et al. arXiv:2406.18744, 2024.

- C. Messori, S. V. C. Messori, S. V. Prinzera, and F. B. di Bardone, "Deep into the water: exploring the hydro-electromagnetic and quantum-electrodynamic properties of interfacial water in living systems," Open Access Library Journal, vol. 6, no. 05, p. 1, 2019.

- Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Ge, X. Recent advances in water-mediated multiphase catalysis. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, K.M.; Singh, A.K.; Bikash, C.R.; Wei, J.; Tal-Gan, Y.; Vinh, N.Q.; Leitner, D.M. The origin and impact of bound water around intrinsically disordered proteins. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, K.; Carteret, C.; Lebeau, B.; Marichal, C.; Vidal, L.; Stébé, M.-J.; Blin, J.-L. Water-Catalyzed Low-Temperature Transformation from Amorphous to Semi-Crystalline Phase of Ordered Mesoporous Titania Framework. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 2, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, E.; Tedeschi, A.; Vitiello, G.; Voeikov, V. Coherent structures in liquid water close to hydrophilic surfaces.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 012028.

- Peng, Z.; Yan, J.; Fan, X.; Mizianty, M.J.; Xue, B.; Wang, K.; Hu, G.; Uversky, V.N.; Kurgan, L. Exceptionally abundant exceptions: comprehensive characterization of intrinsic disorder in all domains of life. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 72, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulos, I.; Khaldi, N.; Davey, N.E.; O’brien, K.; Martin, F.; Shields, D.C.; Kim, P.M. Protein Disorder and Short Conserved Motifs in Disordered Regions Are Enriched near the Cytoplasmic Side of Single-Pass Transmembrane Proteins. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e44389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V. N. Uversky, "Intrinsically disordered proteins and their environment: effects of strong denaturants, temperature, pH, counter ions, membranes, binding partners, osmolytes, and macromolecular crowding," The protein journal, vol. 28, pp. 305-325, 2009.

- V. N. Uversky, "Intrinsically disordered proteins from A to Z," The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology, vol. 43, no. 8, pp. 1090-1103, 2011.

- Uversky, V.N.; Li, J.; Fink, A.L. Evidence for a Partially Folded Intermediate in α-Synuclein Fibril Formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 10737–10744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, K.M.; Roberts, S.; Chilkoti, A.; Pappu, R.V. Advances in Understanding Stimulus-Responsive Phase Behavior of Intrinsically Disordered Protein Polymers. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 4619–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonin, A.V.; Darling, A.L.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Turoverov, K.K.; Uversky, V.N. Intrinsically disordered proteins in crowded milieu: when chaos prevails within the cellular gumbo. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3907–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoverov, K.K.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Uversky, V.N. The protein kingdom extended: Ordered and intrinsically disordered proteins, their folding, supramolecular complex formation, and aggregation. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2010, 102, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, J.; Gianni, S.; Jemth, P. The binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 16, 6323–6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.E.; Dyson, H.J. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.K.; Stultz, C.M. Constructing ensembles for intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011, 21, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V. N. Uversky, "Unusual biophysics of intrinsically disordered proteins," Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics, vol. 1834, no. 5, pp. 932-951, 2013.

- R. Van Der Lee et al., "Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins," Chemical reviews, vol. 114, no. 13, pp. 6589-6631, 2014.

- Darling, A.L.; Uversky, V.N. Intrinsic Disorder and Posttranslational Modifications: The Darker Side of the Biological Dark Matter. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, M.; Jensen, O.N. Proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youle, R.J.; Strasser, A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. R. Jungblut, H. G. P. R. Jungblut, H. G. Holzhütter, R. Apweiler, and H. Schlüter, "The speciation of the proteome," Chemistry Central Journal, vol. 2, pp. 1-10, 2008.

- Kulkarni, P.; Jolly, M.K.; Jia, D.; Mooney, S.M.; Bhargava, A.; Kagohara, L.T.; Chen, Y.; Hao, P.; He, Y.; Veltri, R.W.; et al. Phosphorylation-induced conformational dynamics in an intrinsically disordered protein and potential role in phenotypic heterogeneity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, E2644–E2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Hess, D.; Eglinger, J.; Fritsch, A.W.; Kreysing, M.; Weinert, B.T.; Choudhary, C.; Matthias, P. Acetylation of intrinsically disordered regions regulates phase separation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 15, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Zamakhaeva, S.; Rush, J.S.; Chaton, C.T.; Kenner, C.W.; Hla, Y.M.; Tsui, H.-C.T.; Uversky, V.N.; Winkler, M.E.; Korotkov, K.V.; et al. Glycosylation of serine/threonine-rich intrinsically disordered regions of membrane-associated proteins in streptococci. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ji, J.; Hossain, S.; Bailey, B.; Nangia, S.; Mozhdehi, D. Lipidation alters the phase-separation of resilin-like polypeptides. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 4007–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, V.; Schmidtgall, B.; Gógl, G.; Dolenc, J.; Osz, J.; Nominé, Y.; Kostmann, C.; Cousido-Siah, A.; Mitschler, A.; Rochel, N.; et al. Conformational editing of intrinsically disordered protein by α-methylation. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Yamin, G.; Munishkina, L.A.; Karymov, M.A.; Millett, I.S.; Doniach, S.; Lyubchenko, Y.L.; Fink, A.L. Effects of nitration on the structure and aggregation of α-synuclein. Mol. Brain Res. 2005, 134, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, L.; Henen, M.A.; Haiderer, S.; Schwarz, T.C.; Kurzbach, D.; Zawadzka-Kazimierczuk, A.; Saxena, S.; Żerko, S.; Koźmiński, W.; Hinderberger, D.; et al. Protonation-dependent conformational variability of intrinsically disordered proteins. Protein Sci. 2013, 22, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; She, Y.; Li, C.; Shen, L. Metal ion mediated aggregation of Alzheimer's disease peptides and proteins in solutions and at surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 320, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise-Scira, O.; Dunn, A.; Aloglu, A.K.; Sakallioglu, I.T.; Coskuner, O. Structures of the E46K Mutant-Type α-Synuclein Protein and Impact of E46K Mutation on the Structures of the Wild-Type α-Synuclein Protein. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, Z.A.; Larini, L.; LaPointe, N.E.; Feinstein, S.C.; Shea, J.-E. Regulation and aggregation of intrinsically disordered peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 2758–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Kjaergaard, A. B. M. Kjaergaard, A. B. Nørholm, R. Hendus‒Altenburger, S. F. Pedersen, F. M. Poulsen, and B. B. Kragelund, "Temperature-dependent structural changes in intrinsically disordered proteins: Formation of α‒helices or loss of polyproline II?," Protein Science, vol. 19, no. 8, pp. 1555-1564, 2010.

- M. Vidović and S. Komić Milić, "Regulation of proteolysis of intrinsically disordered proteins: Physiological consequences," A closer look at proteolysis, pp. 1-46, 2021.

- Uversky, V.N.; Oldfield, C.J.; Dunker, A.K. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins in Human Diseases: Introducing the D2Concept. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 37, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Morita, S.; Hayashi, T. Role of interfacial water in determining the interactions of proteins and cells with hydrated materials. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2021, 198, 111449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneff, S.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M. Taurine prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and protects mitochondria from reactive oxygen species and deuterium toxicity. Amino Acids 2025, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, X.A.; Pollack, G.H. Exclusion-zone formation from discontinuous nafion surfaces. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodynamics 2011, 6, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elton, D.C.; Spencer, P.D.; Riches, J.D.; Williams, E.D. Exclusion Zone Phenomena in Water—A Critical Review of Experimental Findings and Theories. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Lin, W. L. Lin, W. Jiang, X. Xu, and P. Xu, "A critical review of the application of electromagnetic fields for scaling control in water systems: mechanisms, characterization, and operation," NPJ Clean Water, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 25, 2020.

- Chai, B.; Mahtani, A.G.; Pollack, G.H. UNEXPECTED PRESENCE OF SOLUTE-FREE ZONES AT METAL-WATER INTERFACES. Contemp. Mater. 2012, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, B.; Yoo, H.; Pollack, G.H. Effect of Radiant Energy on Near-Surface Water. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 13953–13958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, I.; Stahlberg, R.; Kung, K.; Pollack, G.H.; Chin, W.-C. Low frequency weak electric fields can induce structural changes in water. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0260967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, E.; Preparata, G.; Vitiello, G. Water as a Free Electric Dipole Laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 61, 1085–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. De Ninno, E. A. De Ninno, E. Del Giudice, L. Gamberale, and A. C. I: Castellano, "The structure of liquid water emerging from the vibrational spectroscopy; arXiv:1310.0635, 2013.

- Pollack, G. The Fourth Phase of Water: A role in fascia? J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2013, 17, 510–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taschin, A.; Bartolini, P.; Eramo, R.; Righini, R.; Torre, R. Evidence of two distinct local structures of water from ambient to supercooled conditions. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. J. Geesink, I. H. J. Geesink, I. Jerman, and D. K. Meijer, "Water, the cradle of life via its coherent quantum frequencies," Water, vol. 11, pp. 78-108, 2020.

- Ho, M.-W. Illuminating water and life: Emilio Del Giudice. Electromagn. Biol. Med. 2015, 34, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. C. Wahl and M. Sundaralingam, "C H… O hydrogen bonding in biology," Trends in biochemical sciences, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 97-102, 1997.

- G. Otting, E. G. Otting, E. Liepinsh, and K. Wuthrich, "Protein hydration in aqueous solution," Science, vol. 254, no. 5034, pp. 974-980, 1991.

- D. E. Moilanen, I. R. D. E. Moilanen, I. R. Piletic, and M. D. Fayer, "Water dynamics in Nafion fuel cell membranes: The effects of confinement and structural changes on the hydrogen bond network," The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, vol. 111, no. 25, pp. 8884-8891, 2007.

- Mentré, P. Interfacial water: a modulator of biological activity. J. Biol. Phys. Chem. 2004, 4, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunan, E.; Desiraju, G.R.; Klein, R.A.; Sadlej, J.; Scheiner, S.; Alkorta, I.; Clary, D.C.; Crabtree, R.H.; Dannenberg, J.J.; Hobza, P.; et al. Defining the hydrogen bond: An account (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2011, 83, 1619–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, P. Water as an Active Constituent in Cell Biology. Chem. Rev. 2007, 108, 74–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.K.; Zewail, A.H. Dynamics of Water in Biological Recognition. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2099–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Zhang, C.; Weichselbaum, E.; Knyazev, D.G.; Pohl, P.; Carloni, P.; Johnson, C. Interfacial water molecules at biological membranes: Structural features and role for lateral proton diffusion. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0193454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bothma, J.P.; Gilmore, J.B.; McKenzie, R.H. The role of quantum effects in proton transfer reactions in enzymes: quantum tunneling in a noisy environment? New J. Phys. 2010, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Guo, J.; Peng, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, J.-R.; Li, X.-Z.; Wang, E.-G.; Jiang, Y. Direct visualization of concerted proton tunnelling in a water nanocluster. Nat. Phys. 2015, 11, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. K. Allemann and N. S. Scrutton, Quantum tunnelling in enzyme-catalysed reactions. Royal Society of Chemistry, 2009.

- del Giudice, E.; Doglia, S.; Milani, M.; Vitiello, G. Electromagnetic field and spontaneous symmetry breaking in biological matter. Nucl. Phys. B 1986, 275, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichou, Y.; Schirò, G.; Gallat, F.-X.; Laguri, C.; Moulin, M.; Combet, J.; Zamponi, M.; Härtlein, M.; Picart, C.; Mossou, E.; et al. Hydration water mobility is enhanced around tau amyloid fibers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 6365–6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camino, J.D.; Gracia, P.; Cremades, N. The role of water in the primary nucleation of protein amyloid aggregation. Biophys. Chem. 2021, 269, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellissent-Funel, M.-C.; Hassanali, A.; Havenith, M.; Henchman, R.; Pohl, P.; Sterpone, F.; van der Spoel, D.; Xu, Y.; E Garcia, A. Water Determines the Structure and Dynamics of Proteins. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7673–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgabarty, H.; Kaliannan, N.K.; Kühne, T.D. Enhancement of the local asymmetry in the hydrogen bond network of liquid water by an ultrafast electric field pulse. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Shalaby, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.-C. Ultrafast hydrogen bond dynamics of liquid water revealed by terahertz-induced transient birefringence. Light. Sci. Appl. 2020, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faupin, J.; Fröhlich, J.; Schubnel, B. On the Probabilistic Nature of Quantum Mechanics and the Notion of Closed Systems. Ann. Henri Poincare 2015, 17, 689–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, T.J.F.; Schmitt, U.W.; Voth, G.A. The Mechanism of Hydrated Proton Transport in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 12027–12028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. J. Siwick and H. J. Bakker, "On the role of water in intermolecular proton-transfer reactions," Journal of the American Chemical Society, vol. 129, no. 44, pp. 13412-13420, 2007.

- J. Odutola, T. J. Odutola, T. Hu, D. Prinslow, S. O’dell, and T. Dyke, "Water dimer tunneling states with K= 0," The Journal of chemical physics, vol. 88, no. 9, pp. 5352-5361, 1988.

- M. L. Rao, S. R. M. L. Rao, S. R. Sedlmayr, R. Roy, and J. Kanzius, "Polarized microwave and RF radiation effects on the structure and stability of liquid water," Curr. Sci, vol. 98, no. 11, pp. 1500-1504, 2010.

- Vallée, P.; Lafait, J.; Legrand, L.; Mentré, P.; Monod, M.-O.; Thomas, Y. Effects of Pulsed Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields on Water Characterized by Light Scattering Techniques: Role of Bubbles. Langmuir 2005, 21, 2293–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, E.; Magazù, S. Response of hydrogen bonding to low-intensity 50 Hz electromagnetic field in typical proteins in bi-distilled water solution. Spectrosc. Lett. 2017, 50, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.; Armishaw, R. Structure of aqueous solutions: Infrared spectra of the water librational mode in solutions of monovalent halides. Aust. J. Chem. 1975, 28, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, N.J.; MacElroy, J.M.D. Molecular dynamics simulations of microwave heating of water. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 1589–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, D.J.; Messini, N.; Karabarbounis, A.; Philippetis, A.L.; Margaritis, L.H. A Mechanism for Action of Oscillating Electric Fields on Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 272, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, D.J.; Johansson, O.; Carlo, G.L. Polarization: A Key Difference between Man-made and Natural Electromagnetic Fields, in regard to Biological Activity. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philbin, T.G. Quantum dynamics of the damped harmonic oscillator. New J. Phys. 2012, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Pikovsky, M. A. Pikovsky, M. Rosenblum, and J. Kurths, "Synchronization—A unified approach to nonlinear science," ed: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001.

- S. Samdal, "The effect of large amplitude motion on the comparison of bond distances from ab initio calculations and experimentally determined bond distances, and on root-mean-square amplitudes of vibration, shrinkage, asymmetry constants, symmetry constraints, and inclusion of rotational constants using the electron diffraction method," Journal of molecular structure, vol. 318, pp. 133-141, 1994.

- Kirillova, S.; Carugo, O. Hydration sites of unpaired RNA bases: a statistical analysis of the PDB structures. BMC Struct. Biol. 2011, 11, 41–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifoni, M.; Hänggi, P. Driven quantum tunneling. Phys. Rep. 1998, 304, 229–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shun-Ping et al., "Geometrical structures, vibrational frequencies, force constants and dissociation energies of isotopic water molecules (H2O, HDO, D2O, HTO, DTO, and T2O) under dipole electric field," Chinese Physics B, vol. 20, no. 6, p. 063102, 2011.

- Zong, D.; Hu, H.; Duan, Y.; Sun, Y. Viscosity of Water under Electric Field: Anisotropy Induced by Redistribution of Hydrogen Bonds. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 4818–4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranyai, A.; Bartók, A.; Chialvo, A.A. Computer simulation of the 13 crystalline phases of ice. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 054502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laage, D.; Hynes, J.T. A Molecular Jump Mechanism of Water Reorientation. Science 2006, 311, 832–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, D.; Tuckerman, M.E.; Hutter, J.; Parrinello, M. The nature of the hydrated excess proton in water. Nature 1999, 397, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, B. Water Dynamics in the Hydration Layer around Proteins and Micelles. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3197–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönichen, A.; Webb, B.A.; Jacobson, M.P.; Barber, D.L. Considering Protonation as a Posttranslational Modification Regulating Protein Structure and Function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013, 42, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossat, M.J. MEDOC: A Fast, Scalable, and Mathematically Exact Algorithm for the Site-Specific Prediction of the Protonation Degree in Large Disordered Proteins. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelton, J.; Torchia, D.; Meadow, N.; Roseman, S. Tautomeric states of the active-site histidines of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated IIIGlc, a signal-transducing protein from escherichia coli, using two-dimensional heteronuclear NMR techniques. Protein Sci. 1993, 2, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Jacquemin, D. Electric-field induced mutation of DNA: a theoretical investigation of the GC base pair. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 4548–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Jacquemin, D. Electric field induced DNA damage: an open door for selective mutations. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7578–7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Cerezo, J.; Jacquemin, D. How DNA is damaged by external electric fields: selective mutation vs. random degradation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 16, 8243–8246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Antonov, Tautomerism: Concepts and Applications in Science and Technology. John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

- Singh, V.; Fedeles, B.I.; Essigmann, J.M. Role of tautomerism in RNA biochemistry. RNA 2014, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Zied, O.K.; Jimenez, R.; Romesberg, F.E. Tautomerization Dynamics of a Model Base Pair in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 4613–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.S.; Jones, K.C.; Tokmakoff, A. Anharmonic Vibrational Modes of Nucleic Acid Bases Revealed by 2D IR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 15650–15660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, L.; Biswas, P. Hydration Water Distribution around Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 4206–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubmüller, H.; Heller, H.; Windemuth, A.; Schulten, K. Generalized Verlet Algorithm for Efficient Molecular Dynamics Simulations with Long-range Interactions. Mol. Simul. 1991, 6, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, H.; Baidya, L.; Reddy, G. Salt-Induced Transitions in the Conformational Ensembles of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 5959–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Achuthan, S.; Behal, A.; Jolly, M.K.; Kotnala, S.; Mohanty, A.; Rangarajan, G.; Salgia, R.; Uversky, V. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Critical Components of the Wetware. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 6614–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Faraggi, E.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y. Intrinsically Semi-disordered State and Its Role in Induced Folding and Protein Aggregation. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 67, 1193–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, P.K.; Futera, Z.; English, N.J. Perturbation of hydration layer in solvated proteins by external electric and electromagnetic fields: Insights from non-equilibrium molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 205101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Ekenna, C. A New Tool to Study the Binding Behavior of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abyzov, A.; Blackledge, M.; Zweckstetter, M. Conformational Dynamics of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Regulate Biomolecular Condensate Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 6719–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, A.I.; Reiter, G.F.; Choudhury, N.; Prisk, T.R.; Mamontov, E.; Podlesnyak, A.; Ehlers, G.; Seel, A.G.; Wesolowski, D.J.; Anovitz, L.M. Quantum Tunneling of Water in Beryl: A New State of the Water Molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 167802–167802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, A.H.; Lyle, N.; Pappu, R.V. Describing sequence–ensemble relationships for intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochem. J. 2012, 449, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrea, D.M.; Kriwacki, R.W. Phase separation in biology; functional organization of a higher order. Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Han, T.W.; Xie, S.; Shi, K.; Du, X.; Wu, L.C.; Mirzaei, H.; Goldsmith, E.J.; Longgood, J.; Pei, J.; et al. Cell-free Formation of RNA Granules: Low Complexity Sequence Domains Form Dynamic Fibers within Hydrogels. Cell 2012, 149, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormann, D.; Lemke, E.A. Adding intrinsically disordered proteins to biological ageing clocks. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyilov, V.D.; Ilyinsky, N.S.; Nesterov, S.V.; Saqr, B.M.G.A.; Dayhoff, G.W.; Zinovev, E.V.; Matrenok, S.S.; Fonin, A.V.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Turoverov, K.K.; et al. Chaotic aging: intrinsically disordered proteins in aging-related processes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A.H.S.; Lopes, F.C.; John, E.B.O.; Carlini, C.R.; Ligabue-Braun, R. Modulation of Disordered Proteins with a Focus on Neurodegenerative Diseases and Other Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbo, H.; Sato, M.; Okoshi, A.; Fukuchi, S. Functional Segments on Intrinsically Disordered Regions in Disease-Related Proteins. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholes, G.D.; Fleming, G.R.; Chen, L.X.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Buchleitner, A.; Coker, D.F.; Engel, G.; Van Grondelle, R.; Ishizaki, A.; Jonas, D.; et al. Using coherence to enhance function in chemical and biophysical systems. Nature 2017, 543, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Bennett, "S teck JE, B ehrm an E C," Quantum information and computation, vol. 404, no. 3, pp. 247-255, 2000.

- J. Cavanagh, W. J. J. Cavanagh, W. J. Fairbrother, A. G. Palmer, M. Rance, and N. J. Skelton, "CHAPTER 7 - HETERONUCLEAR NMR EXPERIMENTS," in Protein NMR Spectroscopy (Second Edition), J. Cavanagh, W. J. Fairbrother, A. G. Palmer, M. Rance, and N. J. Skelton Eds. Burlington: Academic Press, 2007, pp. 533-678.

- Kragelj, J.; Ozenne, V.; Blackledge, M.; Jensen, M.R. Conformational Propensities of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins from NMR Chemical Shifts. Chemphyschem 2013, 14, 3034–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narth, C.; Gillet, N.; Cailliez, F.; Lévy, B.; de la Lande, A. Electron Transfer, Decoherence, and Protein Dynamics: Insights from Atomistic Simulations. Accounts Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenenbaum, A. Kinetic coherence underlies the dynamics of disordered proteins. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 36242–36249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rather, S.R.; Scholes, G.D.; Chen, L.X. From Coherence to Function: Exploring the Connection in Chemical Systems. Accounts Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 2620–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binolfi, A.; Theillet, F.-X.; Selenko, P. Bacterial in-cell NMR of human α-synuclein: a disordered monomer by nature? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012, 40, 950–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usselman, R.J.; Chavarriaga, C.; Castello, P.R.; Procopio, M.; Ritz, T.; Dratz, E.A.; Singel, D.J.; Martino, C.F. The Quantum Biology of Reactive Oxygen Species Partitioning Impacts Cellular Bioenergetics. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, F.; Bremer, A.; Tesei, G.; Hopkins, J.B.; Grace, C.R.; Mittag, T.; Lindorff-Larsen, K. Design of intrinsically disordered protein variants with diverse structural properties. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadm9926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehi, B.R.; Gadhave, K.; Uversky, V.N.; Giri, R. Intrinsic disorder in proteins associated with oxidative stress-induced JNK signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Leterrier, "Water and the cytoskeleton," Cellular and molecular biology (Noisy-le-Grand, France), vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 901-923, 2001.

- Westerheide, S.D.; Morimoto, R.I. Heat Shock Response Modulators as Therapeutic Tools for Diseases of Protein Conformation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 33097–33100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Pastor, R.; Burchfiel, E.T.; Thiele, D.J. Regulation of heat shock transcription factors and their roles in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U. Sengupta and R. Kayed, "Amyloid β, Tau, and α-Synuclein aggregates in the pathogenesis, prognosis, and therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases," Progress in neurobiology, vol. 214, p. 102270, 2022.

- Firman, T.; Ghosh, K. Sequence charge decoration dictates coil-globule transition in intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 148, 123305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theillet, F.-X.; Binolfi, A.; Frembgen-Kesner, T.; Hingorani, K.; Sarkar, M.; Kyne, C.; Li, C.; Crowley, P.B.; Gierasch, L.; Pielak, G.J.; et al. Physicochemical Properties of Cells and Their Effects on Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs). Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6661–6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Xu, D. CORRELATION BETWEEN POSTTRANSLATIONAL MODIFICATION AND INTRINSIC DISORDER IN PROTEIN. Proceedings of the Pacific Symposium. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 94–103.

- Khoury, G.A.; Baliban, R.C.; Floudas, C.A. Proteome-wide post-translational modification statistics: frequency analysis and curation of the swiss-prot database. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Katuwawala, A.; Oldfield, C.J.; Hu, G.; Wu, Z.; Uversky, V.N.; Kurgan, L. Intrinsic Disorder in Human RNA-Binding Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 167229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Y. Liu, C. A. A. Y. Liu, C. A. Minetti, D. P. Remeta, K. J. Breslauer, and K. Y. Chen, "HSF1, aging, and neurodegeneration," Cell Biology and Translational Medicine, Volume 18: Tissue Differentiation, Repair in Health and Disease, pp. 23-49, 2022.

- Ren, Q.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Shi, C.; Sun, Y.; Yao, X.; Hou, Z.; Xiang, S. The molecular mechanism of temperature-dependent phase separation of heat shock factor 1. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2025, 21, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamovsky, I.; Ivannikov, M.; Kandel, E.S.; Gershon, D.; Nudler, E. RNA-mediated response to heat shock in mammalian cells. Nature 2006, 440, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shao, S.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Ren, Q.; Xiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Sun, Y. Reversible phase separation of HSF1 is required for an acute transcriptional response during heat shock. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anckar, J.; Sistonen, L. Regulation of HSF1 Function in the Heat Stress Response: Implications in Aging and Disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 1089–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wu, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Yang, R. Regulation of HSF1 protein stabilization: An updated review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 822, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerheide, S.D.; Anckar, J.; Stevens, S.M.; Sistonen, L.; Morimoto, R.I. Stress-Inducible Regulation of Heat Shock Factor 1 by the Deacetylase SIRT1. Science 2009, 323, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynes, R.; Brunquell, J.; Westerheide, S.D. Stress Inducibility of SIRT1 and Its Role in Cytoprotection and Cancer. Genes Cancer 2013, 4, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xu, L.; Alberobello, A.T.; Gavrilova, O.; Bagattin, A.; Skarulis, M.; Liu, J.; Finkel, T.; Mueller, E. Celastrol Protects against Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction through Activation of a HSF1-PGC1α Transcriptional Axis. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelin, E.; Freeman, B.C. Lysine Deacetylases Regulate the Heat Shock Response Including the Age-Associated Impairment of HSF1. J. Mol. Biol. 2015, 427, 1644–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. Dasdag, N. O. Dasdag, N. Adalier, and S. Dasdag, "Electromagnetic radiation and Alzheimer’s disease," Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 1087-1094, 2020.

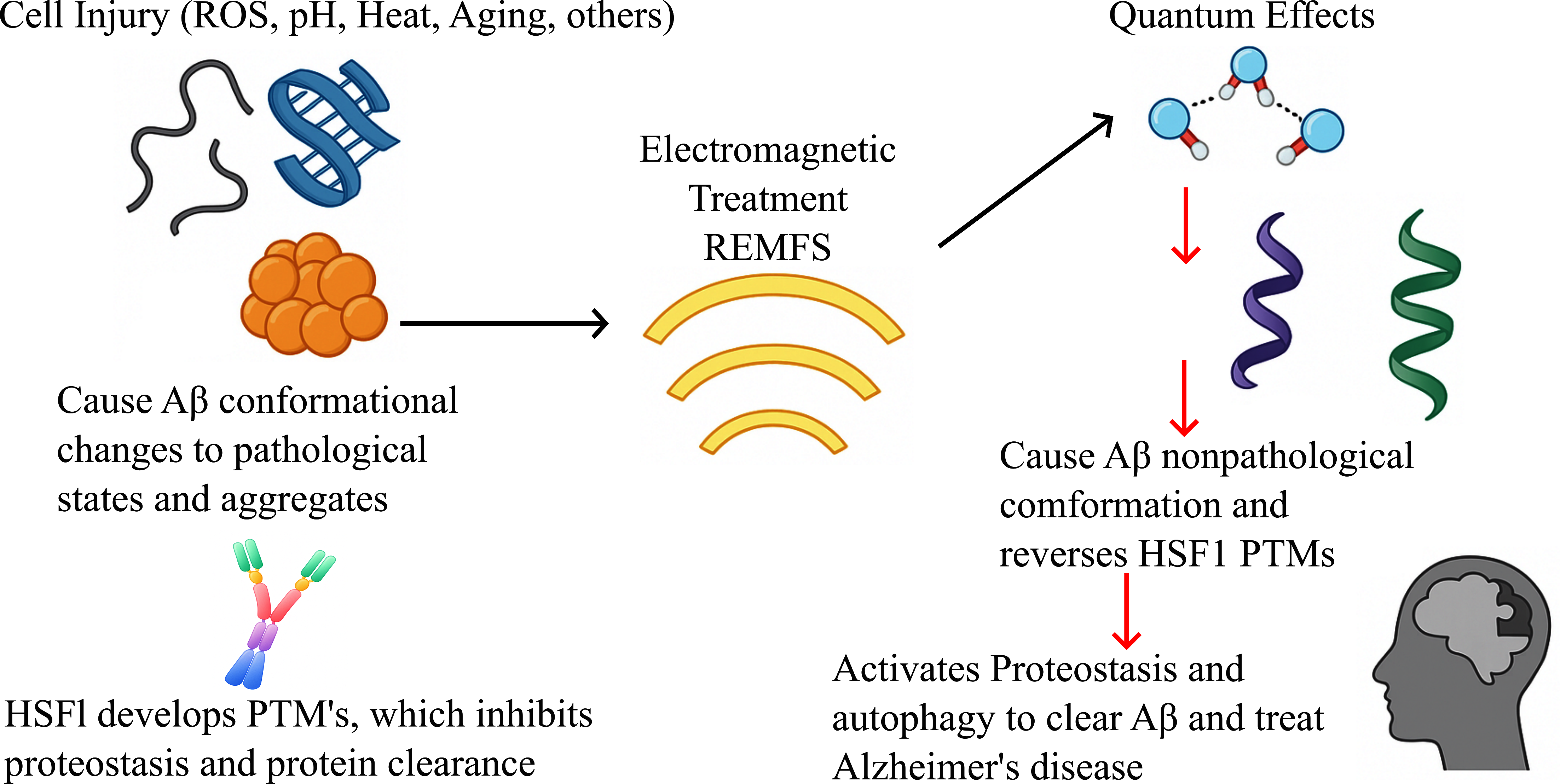

- F. P. Perez, J. P. F. P. Perez, J. P. Bandeira, C. N. Perez Chumbiauca, D. K. Lahiri, J. Morisaki, and M. Rizkalla, "Multidimensional insights into the repeated electromagnetic field stimulation and biosystems interaction in aging and age-related diseases," Journal of Biomedical Science, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 1-22, 2022.

- I. C. o. N.-I. R. Protection, "Guidelines for limiting exposure to electromagnetic fields (100 kHz to 300 GHz)," Health physics, vol. 118, no. 5, pp. 483-524, 2020.

- Marchesi, N.; Osera, C.; Fassina, L.; Amadio, M.; Angeletti, F.; Morini, M.; Magenes, G.; Venturini, L.; Biggiogera, M.; Ricevuti, G.; et al. Autophagy Is Modulated in Human Neuroblastoma Cells Through Direct Exposition to Low Frequency Electromagnetic Fields. J. Cell. Physiol. 2014, 229, 1776–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T.; Taniura, H.; Goto, Y.; Ogura, M.; Sng, J.C.G.; Yoneda, Y. Stimulation of ubiquitin–proteasome pathway through the expression of amidohydrolase for N-terminal asparagine (Ntan1) in cultured rat hippocampal neurons exposed to static magnetism. J. Neurochem. 2006, 96, 1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kwon, J.H.; Kim, N.; Song, K. Effects of 1950 MHz radiofrequency electromagnetic fields on Aβ processing in human neuroblastoma and mouse hippocampal neuronal cells. J. Radiat. Res. 2017, 59, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Jeong et al., "1950 MHz Electromagnetic Fields Ameliorate Abeta Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease Mice," Current Alzheimer research, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 481-92, 2015. Online.. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26017559.

- Rao, R.R.; Halper, J.; Kisaalita, W.S. Effects of 60 Hz electromagnetic field exposure on APP695 transcription levels in differentiating human neuroblastoma cells. Bioelectrochemistry 2002, 57, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. A. Antonini et al., "Extremely low-frequency electromagnetic field (ELF-EMF) does not affect the expression of α3, α5 and α7 nicotinic receptor subunit genes in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line," Toxicology letters, vol. 164, no. 3, pp. 268-277, 2006.

- Del Giudice, E.; Facchinetti, F.; Nofrate, V.; Boccaccio, P.; Minelli, T.; Dam, M.; Leon, A.; Moschini, G. Fifty Hertz electromagnetic field exposure stimulates secretion of β-amyloid peptide in cultured human neuroglioma. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 418, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.-L.; Luo, Z.; Shen, T.-T.; Li, P.; Yang, J.; Luo, X.; Chen, C.-H.; Gao, P.; Yang, X.-S. Inhibition of STAT3- and MAPK-dependent PGE2 synthesis ameliorates phagocytosis of fibrillar β-amyloid peptide (1-42) via EP2 receptor in EMF-stimulated N9 microglial cells. J. Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, T.M.; Duce, J.A.; Bayle, E.D. The proteostasis network provides targets for neurodegeneration. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 3508–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, D.; Sigmond, T.; Hotzi, B.; Bohár, B.; Fazekas, D.; Deák, V.; Vellai, T.; Barna, J. HSF1Base: A Comprehensive Database of HSF1 (Heat Shock Factor 1) Target Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, F.P.; Zhou, X.; Morisaki, J.; Jurivich, D. Electromagnetic field therapy delays cellular senescence and death by enhancement of the heat shock response. Exp. Gerontol. 2008, 43, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- F. Manai et al., "A Low-Frequency Electromagnetic (LF-EMF) Exposure Scheme Induces Autophagy Activation to Counteract in Vitro Aβ-Amyloid Neurotoxicity," Atti del, p. 7.

- Trivedi, R.; Knopf, B.; Rakoczy, S.; Manocha, G.D.; Brown-Borg, H.; Jurivich, D.A. Disrupted HSF1 regulation in normal and exceptional brain aging. Biogerontology 2023, 25, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Taguchi, K.; Tanaka, M. Roles of Stress Response in Autophagy Processes and Aging-Related Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, F.P.; Moinuddin, S.S.; Shamim, Q.U.A.; Joseph, D.J.; Morisaki, J.; Zhou, X. Longevity Pathways: HSF1 and FoxO Pathways, a New Therapeutic Target to Prevent Age-Related Diseases. Curr. Aging Sci. 2012, 5, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, F.P.; Zhou, X.; Morisaki, J.; Ilie, J.; James, T.; Jurivich, D.A. Engineered Repeated Electromagnetic Field Shock Therapy for Cellular Senescence and Age-Related Diseases. Rejuvenation Res. 2008, 11, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.; Bassen, H.; Osepchuk, J.; Balzano, Q.; Petersen, R.; Meltz, M.; Cleveland, R.; Lin, J.; Heynick, L. Radio frequency electromagnetic exposure: Tutorial review on experimental dosimetry. Bioelectromagnetics 1996, 17, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, E.; Bucherelli, C. The Inverted “U-Shaped” Dose-Effect Relationships in Learning and Memory: Modulation of Arousal and Consolidation. Nonlinearity Biol. Toxicol. Med. 2005, 3, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.H.M.A.; Fakhoury, M.; Lawand, N. Electromagnetic Field in Alzheimer's Disease: A Literature Review of Recent Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2020, 17, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirbandi, K.; Khalafi, M.; Bevelacqua, J.J.; Sadeghian, N.; Adiban, S.; Zarandi, F.B.; Mortazavi, S.M.J.; Welsh, J.J. Exposure to Low Levels of Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields Emitted from Cell-phones as a Promising Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Scoping Review Study. J. Biomed. Phys. Eng. 2023, 13, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BioInitiative 2012: A Rationale for Biologically-based Exposure Standards for Low-Intensity Electromagnetic Radiation. 2022 Updated Research Summaries.

- Perez, F.P.; Maloney, B.; Chopra, N.; Morisaki, J.J.; Lahiri, D.K. Repeated electromagnetic field stimulation lowers amyloid-β peptide levels in primary human mixed brain tissue cultures. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoy, A.; Saliev, T.; Abzhanova, E.; Turgambayeva, A.; Kaiyrlykyzy, A.; Akishev, M.; Saparbayev, S.; Umbayev, B.; Askarova, S. The Effects of Mobile Phone Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields on β-Amyloid-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human and Rat Primary Astrocytes. Neuroscience 2019, 408, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirai, T.; Taniura, H.; Goto, Y.; Ogura, M.; Sng, J.C.G.; Yoneda, Y. Stimulation of ubiquitin–proteasome pathway through the expression of amidohydrolase for N-terminal asparagine (Ntan1) in cultured rat hippocampal neurons exposed to static magnetism. J. Neurochem. 2006, 96, 1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osera, C.; Amadio, M.; Falone, S.; Fassina, L.; Magenes, G.; Amicarelli, F.; Ricevuti, G.; Govoni, S.; Pascale, A. Pre-exposure of neuroblastoma cell line to pulsed electromagnetic field prevents H2O2-induced ROS production by increasing MnSOD activity. Bioelectromagnetics 2015, 36, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osera, C.; Fassina, L.; Amadio, M.; Venturini, L.; Buoso, E.; Magenes, G.; Govoni, S.; Ricevuti, G.; Pascale, A. Cytoprotective Response Induced by Electromagnetic Stimulation on SH-SY5Y Human Neuroblastoma Cell Line. Tissue Eng. Part A 2011, 17, 2573–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Leszczynski, S. D. Leszczynski, S. Joenväärä, J. Reivinen, and R. Kuokka, "Non-thermal activation of the hsp27/p38MAPK stress pathway by mobile phone radiation in human endothelial cells: molecular mechanism for cancer-and blood-brain barrier-related effects," Differentiation, vol. 70, no. 2-3, pp. 120-129, 2002.

- Arendash, G.W.; Mori, T.; Dorsey, M.; Gonzalez, R.; Tajiri, N.; Borlongan, C.; Skoulakis, E.M.C. Electromagnetic Treatment to Old Alzheimer's Mice Reverses β-Amyloid Deposition, Modifies Cerebral Blood Flow, and Provides Selected Cognitive Benefit. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e35751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendash, G.W. Transcranial Electromagnetic Treatment Against Alzheimer's Disease: Why it has the Potential to Trump Alzheimer's Disease Drug Development. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2012, 32, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragicevic, N.; Bradshaw, P.; Mamcarz, M.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Cao, C.; Arendash, G. Long-term electromagnetic field treatment enhances brain mitochondrial function of both Alzheimer's transgenic mice and normal mice: a mechanism for electromagnetic field-induced cognitive benefit? Neuroscience 2011, 185, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendash, G.W.; Sanchez-Ramos, J.; Mori, T.; Mamcarz, M.; Lin, X.; Runfeldt, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Sava, V.; Tan, J.; et al. Electromagnetic Field Treatment Protects Against and Reverses Cognitive Impairment in Alzheimer's Disease Mice. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2010, 19, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Andersson, J.; Hess, A.; Jezzard, P. Effect of subject-specific head morphometry on specific absorption rate estimates in parallel-transmit MRI at 7 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 2023, 89, 2376–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaceur, S.; Banasr, S.; Sakly, M.; Abdelmelek, H. Whole body exposure to 2.4GHz WIFI signals: Effects on cognitive impairment in adult triple transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease (3xTg-AD). Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 240, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Jeong et al., "Behavioral changes and gene profile alterations after chronic 1,950-MHz radiofrequency exposure: An observation in C57BL/6 mice," Brain and Behavior, vol. 10, no. 11, p. e01815, 2020.

- Kumlin, T.; Iivonen, H.; Miettinen, P.; Juvonen, A.; van Groen, T.; Puranen, L.; Pitkäaho, R.; Juutilainen, J.; Tanila, H. Mobile Phone Radiation and the Developing Brain: Behavioral and Morphological Effects in Juvenile Rats. Radiat. Res. 2007, 168, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Lu, J.-M.; Xing, Z.-H.; Zhao, Q.-R.; Hu, L.-Q.; Xue, L.; Zhang, J.; Mei, Y.-A. Effect of 1.8 GHz radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation on novel object associative recognition memory in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep44521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Kim, J.S.; Jeong, Y.J.; Jeong, Y.K.; Kwon, J.H.; Choi, H.-D.; Pack, J.-K.; Kim, N.; Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, H.-J. Long-term RF exposure on behavior and cerebral glucose metabolism in 5xFAD mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 666, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Lai, J.; Wan, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, D.; Ruan, G.; Liu, E.; Liu, G.-P.; et al. Long-term exposure to ELF-MF ameliorates cognitive deficits and attenuates tau hyperphosphorylation in 3xTg AD mice. NeuroToxicology 2016, 53, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zuo, H.; Wang, D.; Peng, R.; Song, T.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Improvement of Spatial Memory Disorder and Hippocampal Damage by Exposure to Electromagnetic Fields in an Alzheimer’s Disease Rat Model. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0126963–e0126963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarnejad, Z.; Esmaeilpour, K.; Shabani, M.; Asadi-Shekaari, M.; Goraghani, M.S.; Ahmadi-Zeidabadi, M. Spatial memory recovery in Alzheimer's rat model by electromagnetic field exposure. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 128, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. de Pomerai et al., "Non-thermal heat-shock response to microwaves," Nature, vol. 405, no. 6785, pp. 417-418, 2000.

- Shallom, J.M.; Di Carlo, A.L.; Ko, D.; Penafiel, L.M.; Nakai, A.; Litovitz, T.A. Microwave exposure induces Hsp70 and confers protection against hypoxia in chick embryos. J. Cell. Biochem. 2002, 86, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisbrot, D.; Lin, H.; Ye, L.; Blank, M.; Goodman, R. Effects of mobile phone radiation on reproduction and development in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 89, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Arendash et al., "A Clinical Trial of Transcranial Electromagnetic Treatment in Alzheimer’s Disease: Cognitive Enhancement and Associated Changes in Cerebrospinal Fluid, Blood, and Brain Imaging," Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, no. Preprint, pp. 1-26, 2019.

- Arendash, G.; Abulaban, H.; Steen, S.; Andel, R.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Baranowski, R.; McGarity, J.; Scritsmier, L.; Lin, X.; et al. Transcranial Electromagnetic Treatment Stops Alzheimer’s Disease Cognitive Decline over a 2½-Year Period: A Pilot Study. Medicines 2022, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Abulaban, H.; Baranowski, R.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Lin, X.; Shen, N.; Zhang, X.; Arendash, G.W. Transcranial Electromagnetic Treatment “Rebalances” Blood and Brain Cytokine Levels in Alzheimer’s Patients: A New Mechanism for Reversal of Their Cognitive Impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 829049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Söderqvist, L. F. Söderqvist, L. Hardell, M. Carlberg, and K. H. Mild, "Radiofrequency fields, transthyretin, and Alzheimer's disease," Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 599-606, 2010.

- Sandyk, R. Alzheimer's Disease: Improvement of Visual Memory and Visuoconstructive Performance by Treatment with Picotesla Range Magnetic Fields. Int. J. Neurosci. 1994, 76, 185–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Gen-Lin et al., "Inhibition of STAT3-and MAPK-dependent PGE2 synthesis ameliorates phagocytosis of fibrillar Beta-amyloid peptide (1-42) via EP2 receptor in EMF-stimulated N9 microglial cells," Journal of Neuroinflammation, vol. 13, 2016.

- Barthelemy, A.; Mouchard, A.; Villegier, A.-S. Glial markers and emotional memory in rats following cerebral radiofrequency exposures. 2016 IEEE Radio and Antenna Days of the Indian Ocean (RADIO). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, FranceDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–2.

- Jiang, D.-P.; Zhang, J.; Xu, S.-L.; Kuang, F.; Lang, H.-Y.; Wang, Y.-F.; An, G.-Z.; Li, J.-H.; Guo, G.-Z. Electromagnetic Pulse Exposure Induces Overexpression of Beta Amyloid Protein in Rats. Arch. Med Res. 2013, 44, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.-P.; Li, J.-H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, S.-L.; Kuang, F.; Lang, H.-Y.; Wang, Y.-F.; An, G.-Z.; Guo, G.-Z. Long-term electromagnetic pulse exposure induces Abeta deposition and cognitive dysfunction through oxidative stress and overexpression of APP and BACE1. Brain Res. 2016, 1642, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, S.; Peng, R.; Yan, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Zou, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhao, L.; Dong, J.; et al. Reduction of Phosphorylated Synapsin I (Ser-553) Leads to Spatial Memory Impairment by Attenuating GABA Release after Microwave Exposure in Wistar Rats. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e95503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochnow, N.; Gebing, T.; Ladage, K.; Krause-Finkeldey, D.; El Ouardi, A.; Bitz, A.; Streckert, J.; Hansen, V.; Dermietzel, R.; Meuth, S.G. Electromagnetic Field Effect or Simply Stress? Effects of UMTS Exposure on Hippocampal Longterm Plasticity in the Context of Procedure Related Hormone Release. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e19437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, R.; Zhou, H.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Yong, Z.; Zuo, H.; Zhao, L.; Dong, J.; et al. Impairment of long-term potentiation induction is essential for the disruption of spatial memory after microwave exposure. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2013, 89, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, R.; Zhao, L.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zuo, H.; Dong, J.; Xu, X.; Zhou, H.; et al. The relationship between NMDA receptors and microwave-induced learning and memory impairment: A long-term observation on Wistar rats. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2015, 91, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tan, S.; Xu, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Yao, B.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Peng, R. Long term impairment of cognitive functions and alterations of NMDAR subunits after continuous microwave exposure. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 181, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Foroozandeh, M. S. E. Foroozandeh, M. S. Naeini, H. Ahadi, and J. Foroozandeh, "Effects of 90min Exposure to 8mT Electromagnetic Fields on Memory in Mice," Journal of American Science, vol. 7, no. 7, 2011.

- Yang, X.; He, G.; Hao, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yu, Z. The role of the JAK2-STAT3 pathway in pro-inflammatory responses of EMF-stimulated N9 microglial cells. J. Neuroinflammation 2010, 7, 54–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, S.F.; Cao, G.; Liu, L.-M.; Egle, P.M.; Shelton, K.R. Stress proteins are not induced in mammalian cells exposed to radiofrequency or microwave radiation. Bioelectromagnetics 1997, 18, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. J. Regel et al., "Pulsed radio-frequency electromagnetic fields: dose-dependent effects on sleep, the sleep EEG and cognitive performance," Journal of sleep research, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 253-258, 2007.

- S. J. Regel et al., "Pulsed radio frequency radiation affects cognitive performance and the waking electroencephalogram," Neuroreport, vol. 18, no. 8, pp. 803-807, 2007.

- J. H. Kim, D.-H. J. H. Kim, D.-H. Yu, Y. H. Huh, E. H. Lee, H.-G. Kim, and H. R. Kim, "Long-term exposure to 835 MHz RF-EMF induces hyperactivity, autophagy and demyelination in the cortical neurons of mice," Scientific reports, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 41129, 2017.

- Safety Levels with Respect to Human Exposure to Electric, Magnetic, and Electromagnetic Fields, 0 Hz to 300 GHz, (2019). I. S. C95.1:2019, 2019.

- Lanni, I.; Chiacchierini, G.; Papagno, C.; Santangelo, V.; Campolongo, P. Treating Alzheimer’s disease with brain stimulation: From preclinical models to non-invasive stimulation in humans. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 165, 105831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. M. Ribeiro, E. R. d. S. F. M. Ribeiro, E. R. d. S. Camargos, L. C. d. Souza, and A. L. Teixeira, "Animal models of neurodegenerative diseases," Revista brasileira de psiquiatria, vol. 35, no. Suppl 2, pp. S82-S91, 2013.

- Guerriero, F.; Botarelli, E.; Mele, G.; Polo, L.; Zoncu, D.; Renati, P.; Sgarlata, C.; Rollone, M.; Ricevuti, G.; Maurizi, N.; et al. An innovative intervention for the treatment of cognitive impairment–Emisymmetric bilateral stimulation improves cognitive functions in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: an open-label study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2391–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.; Park, H.-J.; Jeong, Y.J.; Choi, H.-D.; Kim, N.; Lee, H.-J. Long-term radiofrequency electromagnetic fields exposure attenuates cognitive dysfunction in 5×FAD mice by regulating microglial function. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 2497–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, W.; Zou, Y.; Ma, L.; He, S.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, L. 900 MHZ electromagnetic field exposure relieved AD-like symptoms on APP/PS1 mice: A potential non-invasive strategy for AD treatment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 658, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaki, A.; Salehi, I.; Keymoradzadeh, A.; Azandaryani, M.T.; Golipoor, Z. Effect of Long-term Exposure to Extremely Low-frequency Electromagnetic Fields on β-amyloid Deposition and Microglia Cells in an Alzheimer Model in Rats. J. Guilan Univ. Med Sci. 2021, 30, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang et al., "Effects of 2.4 GHz radiofrequency electromagnetic field exposure on hippocampal proteins in APP/PS1 mice," 2024.

- Teranishi, M.; Ito, M.; Huang, Z.; Nishiyama, Y.; Masuda, A.; Mino, H.; Tachibana, M.; Inada, T.; Ohno, K. Extremely Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Field (ELF-EMF) Increases Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Activities and Ameliorates Depressive Behaviors in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yu, D.-H.; Kim, H.-J.; Huh, Y.H.; Cho, S.-W.; Lee, J.-K.; Kim, H.-G.; Kim, H.R. Exposure to 835 MHz radiofrequency electromagnetic field induces autophagy in hippocampus but not in brain stem of mice. Toxicol. Ind. Heal. 2017, 34, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.-W.; Xie, W.-J.; Yu, B.; Song, C.; Ji, X.-M.; Wang, X.-Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X. Rotating magnetic field inhibits Aβ protein aggregation and alleviates cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Zool. Res. 2024, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, P.; Ding, H.; Liu, C.; Lyu, J.; Le, W. Terahertz Irradiation Improves Cognitive Impairments and Attenuates Alzheimer’s Neuropathology in the APPSWE/PS1DE9 Mouse: A Novel Therapeutic Intervention for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurosci. Bull. 2023, 40, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya-Gómez, A.; Font, L.P.; Burlacu, A.; Alpizar, Y.A.; Cardonne, M.M.; Brône, B.; Bronckaers, A. Extremely Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Stimulation (ELF-EMS) Improves Neurological Outcome and Reduces Microglial Reactivity in a Rodent Model of Global Transient Stroke. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abkhezr, H.; Mohaddes, G.; Nikniaz, Z.; Farhangi, M.A.; Heydari, H.; Nikniaz, L. The effect of Extremely Low Frequency Electromagnetic Field on spatial memory of mice and rats: A systematic review. Learn. Motiv. 2023, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandani, R.; Zibaii, M.I. Unveiling the biological effects of radio-frequency and extremely-low frequency electromagnetic fields on the central nervous system performance. BioImpacts 2023, 14, 30064–30064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, F.P.; Morisaki, J.; Kanakri, H.; Rizkalla, M. Electromagnetic Field Stimulation Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. 2024, 3. 3.

- Jiang, D.-P.; Li, J.-H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, S.-L.; Kuang, F.; Lang, H.-Y.; Wang, Y.-F.; An, G.-Z.; Guo, G.-Z. Long-term electromagnetic pulse exposure induces Abeta deposition and cognitive dysfunction through oxidative stress and overexpression of APP and BACE1. Brain Res. 2016, 1642, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, N. Short-term effects of extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields exposure on Alzheimer's disease in rats. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2014, 91, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouji, M.; Lecomte, A.; Gamez, C.; Blazy, K.; Villégier, A.-S. Impact of Cerebral Radiofrequency Exposures on Oxidative Stress and Corticosterone in a Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2019, 73, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kwon, J.H.; Choi, H.; Pack, J.; Kim, N.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H. 1950 MHz radiofrequency electromagnetic fields do not aggravate memory deficits in 5xFAD mice. Bioelectromagnetics 2016, 37, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Messori, S. V. C. Messori, S. V. Prinzera, and F. B. di Bardone, "The super-coherent state of biological water," Open Access Library Journal, vol. 6, no. 02, p. 1, 2019.

- Madl, P.; Renati, P. Quantum Electrodynamics Coherence and Hormesis: Foundations of Quantum Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ito, M.; Zhang, S.; Toda, T.; Takeda, J.-I.; Ogi, T.; Ohno, K. Extremely low-frequency electromagnetic field induces acetylation of heat shock proteins and enhances protein folding. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morotomi-Yano, K.; Oyadomari, S.; Akiyama, H.; Yano, K.-I. Nanosecond pulsed electric fields act as a novel cellular stress that induces translational suppression accompanied by eIF2α phosphorylation and 4E-BP1 dephosphorylation. Exp. Cell Res. 2012, 318, 1733–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, N.; Choi, H.-D.; Lim, K.-M. 5G Electromagnetic Radiation Attenuates Skin Melanogenesis In Vitro by Suppressing ROS Generation. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, B.J.; Guerrero, M.E.; Prince, T.L.; Okusha, Y.; Bonorino, C.; Calderwood, S.K. The functions and regulation of heat shock proteins; key orchestrators of proteostasis and the heat shock response. Arch. Toxicol. 2021, 95, 1943–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Hu et al., "Heat shock proteins: Biological functions, pathological roles, and therapeutic opportunities," MedComm, vol. 3, no. 3, p. e161, 2022.

- Usselman, R.J.; Hill, I.; Singel, D.J.; Martino, C.F.; Langowski, J. Spin Biochemistry Modulates Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production by Radio Frequency Magnetic Fields. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e93065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Shen, Y.; Hong, L.; Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, P. Effects of Single and Repeated Exposure to a 50-Hz 2-mT Electromagnetic Field on Primary Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. Neurosci. Bull. 2017, 33, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benassi, B.; Filomeni, G.; Montagna, C.; Merla, C.; Lopresto, V.; Pinto, R.; Marino, C.; Consales, C. Extremely Low Frequency Magnetic Field (ELF-MF) Exposure Sensitizes SH-SY5Y Cells to the Pro-Parkinson’s Disease Toxin MPP+. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 53, 4247–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuermann, D.; Mevissen, M. Manmade Electromagnetic Fields and Oxidative Stress—Biological Effects and Consequences for Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.A.; Lee, H.C.; Hong, M.-N.; Park, M.-J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Choi, H.-D.; Kim, N.; Ko, Y.-G.; Lee, J.-S. Effects of combined radiofrequency radiation exposure on levels of reactive oxygen species in neuronal cells. J. Radiat. Res. 2013, 55, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gannes, F.P.; Haro, E.; Hurtier, A.; Taxile, M.; Ruffié, G.; Billaudel, B.; Veyret, B.; Lagroye, I. Effect of Exposure to the Edge Signal on Oxidative Stress in Brain Cell Models. Radiat. Res. 2011, 175, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, M.-M.; Herlinda, B.-J.; Aparicio-Bautista, D.I.; Mondragón-Rodríguez, S.; Overduin, M.; Basurto-Islas, G. Molecular Mechanisms Associated with the Interaction of External Electromagnetic Fields in Protein Dynamics and Aggregation: A Focus on Amyloid-β Peptide. Prog. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, J.; Pandey, G.; Sashidharan, S.; Antony, F.; Nemade, H.B.; Kumar, S.; Chaudhary, N.; Ramakrishnan, V. Electric Field Disruption of Amyloid Aggregation: Potential Noninvasive Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 2250–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Choi, J.; Park, S.-J.; Shim, K.-H.; Baek, C.; Han, H.-B.; Hong, H.-C.; Yun, S.; Cha, M.; Shah, Y.H.; et al. In Vitro Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease by Disintegrating Amyloid-β Using Electromagnetic Waves. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2025, PP, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, S.; Stojceski, F.; Danani, A. Elucidating the Effect of Static Electric Field on Amyloid Beta 1–42 Supramolecular Assembly. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2020, 96, 107535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Rosales, P.A.; D’aDdio, A.; Zhang, Y.; Caflisch, A. Disrupting Dimeric β-Amyloid by Electric Fields. ACS Phys. Chem. Au 2023, 3, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, N.; Lohrasebi, A.; Bordbar, A. Preventing the amyloid-beta peptides accumulation on the cell membrane by applying GHz electric fields: A molecular dynamic simulation. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2023, 123, 108516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.M.; Scanlan, J.M.; Gama-Chonlon, L. Bilateral rTMS Shows No Advantage in Depression nor in Comorbid Depression and Anxiety: A Naturalistic Study. Psychiatr. Q. 2023, 95, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-H.; Hsieh, S.-W.; Chang, H.-W.; Sung, J.-L.; Chuu, C.-P.; Yen, C.-W.; Hour, T.-C. Gamma Frequency Inhibits the Secretion and Aggregation of Amyloid-β and Decreases the Phosphorylation of mTOR and Tau Proteins in vitro. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2022, 90, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobyntseva, A.; Ganaiem, M.; Ivashko-Pachima, Y.; Barnstable, C.J.; Weisinger, B.; Parabucki, A.; Segal, Y.; Shohami, E.; Gozes, I. Extremely Low-Frequency and Low-Intensity Electromagnetic Field Technology (ELF-EMF) Sculpts Microtubules. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2025, 61, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, N.; Bentvelzen, A.; Yarovsky, I. Electromagnetic field modulates aggregation propensity of amyloid peptides. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 035104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toschi, F.; Lugli, F.; Biscarini, F.; Zerbetto, F. Effects of Electric Field Stress on a β-Amyloid Peptide. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 113, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.C. Electromagnetic Fields in Biological Systems; Taylor & Francis: London, United Kingdom, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- N. Lambert, Y.-N. N. Lambert, Y.-N. Chen, Y.-C. Cheng, C.-M. Li, G.-Y. Chen, and F. Nori, "Quantum biology," Nature Physics, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 10-18, 2013.

- MARINO, A.; BECKER, R. BIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF EXTREMELY LOW-FREQUENCY ELECTRIC AND MAGNETIC-FIELDS - REVIEW. 1977, 9, 131–147.

- Semchenko, I.V.; Mikhalka, I.S.; Khakhomov, S.A.; Samofalov, A.L.; Balmakou, A.P. DNA-like Helices as Nanosized Polarizers of Electromagnetic Waves. Front. Nanotechnol. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, M.; Sha, Y. Induced and Inversed Circularly Polarized Luminescence of Achiral Thioflavin T Assembled on Peptide Fibril. Small 2021, 18, 2106130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, F.; Shi, W.; Zhang, T.; Chang, S. Terahertz circular polarization sensing for protein denaturation based on a twisted dual-layer metasurface. Biomed. Opt. Express 2021, 13, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, F.; Morisaki, J.; Kanakri, H.; Rizkalla, M.; Abdalla, A. A Novel Design of a Portable Birdcage via Meander Line Antenna (MLA) to Lower Beta Amyloid (Aβ) in Alzheimer’s Disease. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Heal. Med. 2025, 13, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszkowska, J.; Gas, P. Electromagnetic Fields and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Przeglad Elektrotechniczny 2019, 1, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. L. Fymat, "Electromagnetic Therapy for Neurological and Neurodegenerative Diseases: II. Deep Brain Stimulation," Open Access Journal of Neurology and Neurosurgery, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1-17, 2020.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).