1. Introduction

The use of natural materials in construction is gaining increasing popularity [

1]. Studies show that compared to buildings made of reed-bale, heating and cooling stone buildings require more energy [

2]. Adding reed to concrete mixtures significantly reduces the material thermal conductivity [3−5]. Houses made from straw demonstrate excellent characteristics, such as high thermal insulation efficiency and low energy consumption [

6,

7]. Stubble and straw are known to be among the oldest insulation materials and have been used to make straw-bale walls of houses [

8,

9]. Their porous low-density structure and minimal thermal conductivity make them highly suitable for thermal insulation applications [

10]. The first known straw-bale buildings were erected at the end of the 19th century in Nebraska, mainly due to the poverty of the residents [

11]. One of the oldest such buildings there dates back to 1903 [

12]. This longevity is attributed to the dry local climate [

11]. The Nebraska or load-bearing wall style is the oldest and most common method of constructing straw-bale houses [

13].

Mould on the surfaces of building materials is a significant source of indoor pollution, and disturbances in indoor airflow can aerosolis mould, posing health risks such as asthma [

14]. The impact of mould present in building materials on the health of occupants is a major concern: surface mould exhibits a remarkably high release rate even with mild indoor airflow disturbance [

15]. Therefore, when developing building materials, their susceptibility to microbial growth should be evaluated. However, only a small number of studies have been dedicated to fungal growth on bio-based materials [

15]. Consisting of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, natural materials provide a good habitat for microorganisms. Continuous exposure to mould can cause problems for individuals with weakened immune systems, those with chronic illnesses, children, and the elderly [16−19].

Reed constructions stand out for their healthy indoor climate, and reedʹs high silica content makes it unattractive to insects and other animals. However, if reed is harvested at the wrong time of year, it can lead to material degradation [

20]. Fungi play an important role in the decomposition of organic building materials [

21]. The indoor climate of 20–40 % of buildings in Europe and North America is affected by mould, which is associated with various health problems [

15]. Reed has been found to be susceptible to rot, but the degradation process can be significantly suppressed through thermal treatment [

22]. It is evident that temperature significantly influences mould growth rates [

23]. So far, no substantial studies have been conducted in our climate zone on what kinds of microbes live on straw and reed as building materials, or what the indoor climate is like in houses built with straw- and reed-bales. The aim of this study was to comprehensively investigate the indoor climate of reed and straw houses in Estonia as well as the factors that influence it. This research attempts to fill that gap.

To achieve the set objective:

Indoor climate indicators (relative humidity (RH %) and temperature) were measured from the indoor air of the houses (CO₂ levels were also measured), as well as from two different heights (0.2 m and 1.2 m) in the exterior walls;

Air samples were taken from the bedrooms of the studied houses as well as from the outdoor air, and material samples were collected from the building envelope. Moulds present in both indoor and outdoor air and in the envelope were identified to the genus level;

The moisture load and mould risk of the exterior walls were assessed.

2. Materials and Methods

Samples were collected and data recorded with sensor-data loggers from four buildings with straw-bale walls and four with reed-bale walls. Some of the buildings (two with straw bales and one with reed bales) were built in the Nebraska style, others with frames (one with straw and three with reed bales), and one straw-bale building was constructed using factory-made modules. All the studied buildings were designed and built by designers and construction companies with relevant experience. Visual inspection did not reveal any moisture damage or mould growth. The age of the studied buildings ranged between 2−7 years. The average thickness of the exterior walls was 50±5 cm. All walls were plastered both inside and outside. The plaster layer thickness was mostly 5 cm both inside and outside, except for two buildings. One building had a plaster layer thickness of 7 cm (lime plaster) both inside and outside, while another building had 10 cm of plaster on the interior wall and 12 cm on the exterior wall. Clay plaster was mostly used for plastering, with lime plaster used for both interior and exterior finishing in two buildings. All studied buildings had a relatively high plinth and wide eaves, which are important measures to reduce the moisture load on walls. Both shallow foundations (five buildings) and post foundations (three) were used. All floor structures were made of wood. Roofing materials included wooden shingles (three buildings), roll material/PVC (three buildings), stone (one building), and one building had a green roof.

The experiments were conducted over a period of one year, collecting data on indoor climate parameters (temperature, RH%, CO₂) and microbiology (number of colony-forming units and taxonomic composition) from both air and envelope (wall) materials in parallel. Residents were asked not to ventilate the bedrooms for six hours before sampling. Culture media [malt extract agar (MEA) and 18% dichlorane glycerol agar (DG18)] were prepared and the sampling procedure was carried out according to ISO standard 16000-18 (ISO 16000-18:2011) [

24]. Media components were weighed with an analytical balance (ABJ 120-4M, Kern & Sohn, Balingen, Germany). Media were autoclaved using an HMT 260 MB autoclave (HMC Europe, Tüssling, Germany). Samples were collected with Mirobio MB2 air analysers (Cantum Scientific, Dartford, United Kingdom) on 9 cm Petri dishes four times a year (spring, summer, autumn, and winter) from bedrooms at a height of one meter from the floor. The sampling time was one minute, and the air volume was 100 litres per sample. A total of four parallel samples were collected from each sampling site with both media types. As a reference, air samples were collected in four parallels from outdoor air at a height of 1.5 m from the ground. The collected samples were processed based on the EVS-ISO standard 16000-17 [

25]. Samples were incubated at 25 °C for seven days, after which the colony-forming units were counted. Further cultures were performed to obtain pure cultures. Moulds were identified based on morphological characteristics using a microscope (SP100, Brunnel Microscopes LTD, Chippenham, United Kingdom). Lactophenol cotton blue was used for staining. Media components were weighed with an analytical balance ABJ 120-4M (measurement accuracy ±0.2 mg, manufacturer: Kern & Sohn, Balingen, Germany). Media were autoclaved using an HMT 260 MB autoclave (HMC Europe, Tüssling, Germany). Media plates were poured under a fume hood (Retent AS, Nõo, Estonia). Data on carbon dioxide (CO₂) content, air temperature, and humidity were also collected in each bedroom using Green-Eye model 7798 sensor-data loggers [measurement accuracy for carbon dioxide ±50 ppm, for temperature ±0.6 °C, for air humidity ±3 % (10-90 %), manufacturer: TechGrow, The Hague, Netherlands]. Hobo UX100-023 sensor-data loggers (measurement range -20 °C to +70 °C, 5 to 95 % RH%, accuracy 0.35 °C and 2.5% RH% respectively; manufacturer: Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, United States) were used to collect temperature and humidity data from the building envelope. Cultures were identified to the genus level [26−32].

Samples of straw and reed materials were also taken from the exterior envelope (wall) using a previously developed methodology [

33]. 10-gram volume samples were plated directly onto malt agar (MEA) with added chloramphenicol. Samples were incubated at 32 °C for 72 hours, after which colony-forming units were counted. Additionally, background data on carbon dioxide content, temperature, and humidity were collected from the bedrooms of the studied buildings (the sensor was placed 1.2 m above the floor, recording at 30-minute intervals). Data on temperature and humidity were also collected from the envelope at a depth of 20 cm from the interior surface. For this purpose, 7 mm diameter holes were drilled in the envelope at two heights (0.2 m and 1.2 m). Sensor-data logger measuring heads were placed 20 cm deep into the holes, and automatic measurements were performed at 10-minute intervals. The holes were sealed using plaster, and to some extent, the fibrous material itself collapsed to seal them. Data measured by the Estonian Weather Service from the nearest automatic station (Tallinn, Lääne-Nigula, Türi, Väike-Maarja) were used as outdoor climate data. The moisture load of the envelope was assessed using equation 1, which originates from the standard EVS-EN ISO 13788 [

35]. The moisture excess Δv, g m⁻³ was calculated from the formula:

where: vᵢ – indoor air water vapour content, g m⁻³, and vₑ – outdoor air water vapour content, g m⁻³.

To assess the risk of mould growth, a mathematical model published by Hukka and Viitanen was used, which takes into account both relative humidity and temperature data to calculate the mould index [

36].

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from HNK Analüüsitehnika OÜ (Tallinn, Estonia). Soy-based peptone (≥99 %, Fluka); potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH₂PO₄) (purity ≥99 %,), magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (MgSO₄×7H₂O) (purity ≥99.5 %), D-(+)-glucose (≥99.5 %), dichlorane (2,6-dichloro-4-nitroaniline) (purity ≥96 %), chloramphenicol (purity ≥98 %), glycerol (purity ≥99.96 %), water (deionized), Agar, malt extract, lactophenol cotton blue (for staining fungi) − all Sigma Aldrich, complied with the ISO standard [

24]. Materials needed for microbiological cultures (9 cm Petri dishes, inoculation needles, slides and cover glasses) were purchased from KRK OÜ (Tartu, Estonia).

3. Results

3.1. Indoor Climate Parameters (CO₂, RH%, and Temperature) in Indoor Air and at Two Different Heights in Walls

The average indoor humidity ranged between 36–44 %, being lower in straw-bale buildings (36–39 %) and higher in reed-bale buildings (41–44 %). In reed-bale buildings, the relative humidity in spring was 41±2 %; in summer and autumn, it increased by about 1% compared to the previous season (42±2 % and 43±2 %, respectively).

Throughout the study period, the average carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels in buildings with straw-bale and reed-bale walls were lowest during summer (607±26 ppm in straw-bale buildings and 568±48 ppm in reed-bale buildings). The highest average CO₂ level in straw-bale buildings occurred in spring (636±26 ppm), and in reed-bale buildings during autumn (626±65 ppm). Average indoor air temperatures in the bedrooms of the studied buildings ranged between 19–21 °C. These values were consistent in winter and spring for both house types, averaging 19.0–19.3 °C. In summer, the indoor air temperature in reed-bale buildings was on average 1.6 °C higher than in straw-bale buildings. The highest average indoor temperatures occurred in autumn for both straw- (20.4±0.6 °C) and reed-bale (20.7±0.9 °C) buildings.

At 1.2 meters height within exterior walls (

Table 3), the lowest average temperature in straw-bale buildings occurred in winter (17.5±1.3 °C), while in reed-bale buildings, it was lowest in spring (15.6±1.5 °C). The highest average temperatures at this height were recorded in summer: 20.6±0.8 °C for straw- and 19.3±1.1 °C for reed-bale buildings. In general, at 1.2 m height, temperatures were higher in straw- (17.3–20.6 °C) than in reed-bale (15.6–19.3 °C) buildings.

The difference was much greater at 0.2 m height. In straw-bale buildings, the average air temperature at this height varied between 14.4–19.2 °C, while in reed-bale buildings it ranged from 7.3–16.3 °C. The lowest average temperatures at 0.2 m height in exterior walls were observed during winter (14.4±2.4 °C in straw-bale buildings and 7.3±2.5 °C in reed-bale buildings). The highest average temperatures were observed during summer: 19.2±1.0 °C in straw- and 16.3±1.6 °C in reed-bale buildings.

Relative humidity (RH%) averages at 1.2 meters height in walls were lowest in winter for both building types (33±12 % in straw and 33±14 % in reed) and highest in summer (53±7 % in straw and 57±1 % in reed buildings). Overall RH values ranged from 33−53 % in straw- and 33−57 % in reed-bale buildings.

At 0.2 m height in the wall, the lowest RH% values in winter were 38±4 % in straw and 45±6 % in reed buildings. In summer, the highest values were 54±2 % in straw and 58±1 % in reed buildings. A trend was observed that RH% at 0.2 m height in reed-bale buildings was generally higher (42−58 %) compared to straw-bale buildings (38−54 %).

3.2. Assessment of Moisture Load and Mould Risk in Exterior Structures

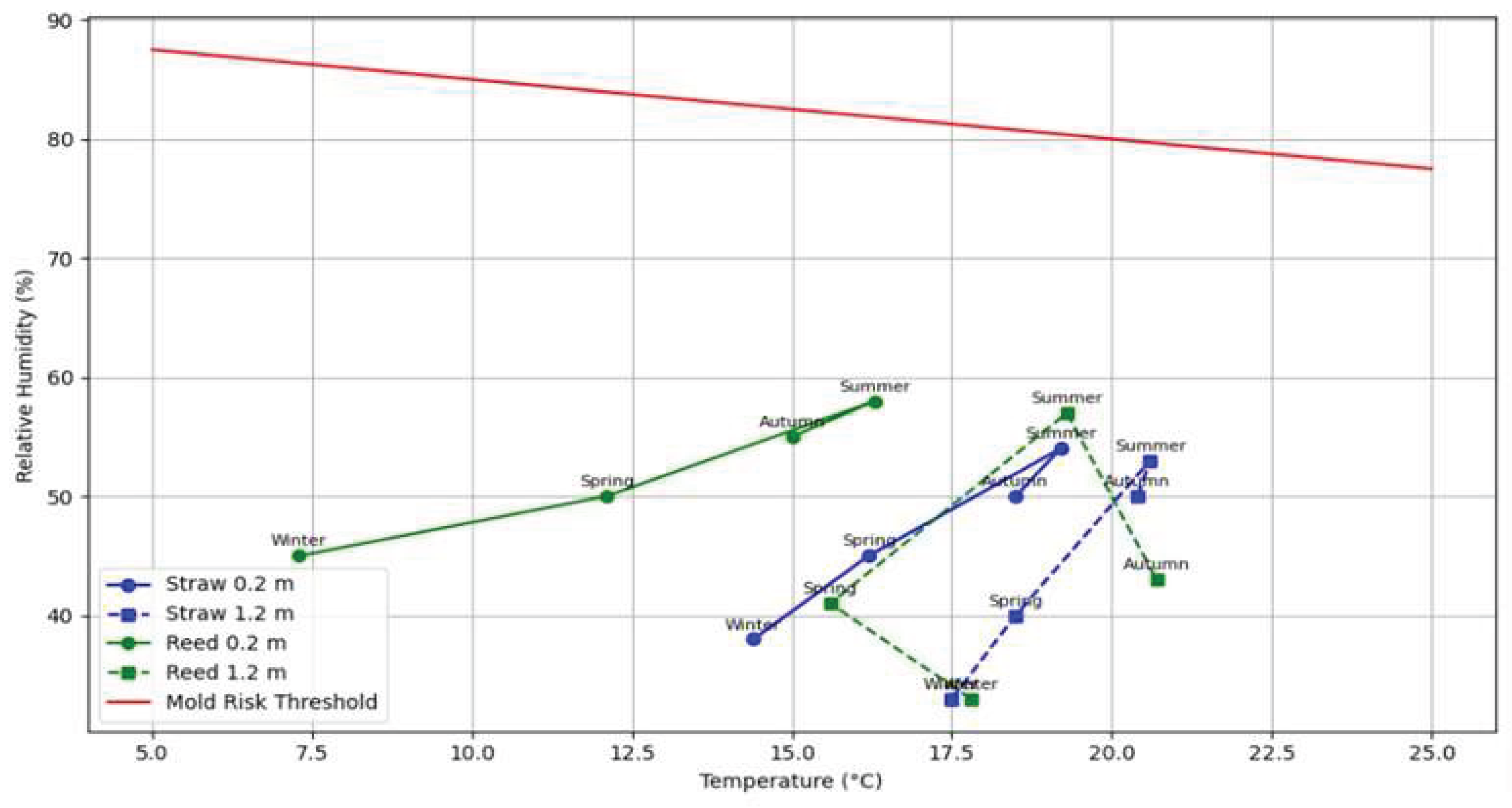

Temperature and humidity values in the envelopes are illustrated in

Figure 1. In some cases, higher humidity and temperature values were recorded in the building envelopes than in indoor air, but the probability that the conditions were suitable for mould growth was considered very low.

The excess indoor moisture was assessed during both winter and summer, based on data from a single representative day. In reed-bale buildings, the excess moisture during summer ranged from 0.46 g/m³ to 3.42 g/m³, and in winter from 0.62 g/m³ to 2.73 g/m³. In straw-bale buildings, the summer values ranged from 2.1 g/m³ to 1.99 g/m³, and in winter from –0.06 g/m³ to 1.43 g/m³. Negative moisture values were recorded during daytime hours when the residents were not present indoors.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between temperature (°C) and relative humidity (RH%) at two different wall heights (0.2 m and 1.2 m) in straw- and reed-bale houses across four seasons. Red line represents the mould risk threshold, derived from the Hukka and Viitanen model [

36], indicating the critical RH% above which mould growth be

comes likely at a given temperature. According to this model, the risk of mould growth in all studied buildings was low. Most data points fall below the threshold line, suggesting that the indoor wall conditions are generally unfavourable for mould development.

Reed-bale buildings show higher average excess moisture in summer than in winter, with values well above 1 g/m³ (see

Table 1). At 0.2 m height, reed-bale walls exhibit slightly higher RH% values, especially in summer and in autumn, but these remain within tolerable limits. In contrast, straw-bale walls consistently show lower RH%, indicating a lower mould risk across all seasons and wall heights.

This study comprehensively examined indoor air quality by collecting both indoor climate indicators (temperature, RH%, CO₂) and microbiological data (colony-forming unit count and taxonomic composition) from both air and wall materials. The interdisciplinary approach examined the indoor climate in buildings built with straw- and reed-bale walls using sensor data loggers and air/material sampling. Two sensor data loggers were placed in the walls at approximately 20 cm depth: one at 0.2 m above the floor to detect potential problem areas near structural joints (e.g., capillary rise, foundation defects, cold bridges), and another at 1.2 m height in a stable wall section. Based on the data gathered from the loggers and the results of air and material samples, it was concluded that the risk of mould in both straw and reed wall structures is low. A notable finding in reed-bale buildings was the exceptionally low temperature (7.3±2.5 °C) at 0.2 m height in the wall during winter, which indicates the low density of reed bales.

3.3. Abundance and Dynamics of Mould in Indoor and Outdoor Air by Season, and Mould Composition by Genera

The seasonal dynamics of colony-forming units in the bedrooms of houses built with both straw and reed bales were similar (

Table 2). The most abundant indoor microbial community in straw houses was observed in summer (June-August), when cultivable colonies from indoor air on malt extract agar (MEA) averaged 537±102 CFU m⁻³. The same relationship was observed for reed-bale houses, where in summer, cultivable colonies from indoor air on malt extract agar (MEA) averaged 858±106 CFU m⁻³. In outdoor air, 289±32 CFU m⁻³ were recorded for straw houses and 353±41 CFU m⁻³ for reed-bale houses during the same period. In spring and autumn, the results for samples taken on malt extract agar (MEA) from both indoor and outdoor air remained at comparable levels. Samples taken on 18 % dichlorane glycerol media (DG18) were also higher in both indoor and outdoor air specifically during the summer period and lowest in winter.

Moulds were identified to the genus level (

Table 3). In the winter period, most of the identified mould in straw houses belonged to the genus Penicillium (74 %), followed by mould from the genera Aspergillus (17 %), Alternaria (1 %), and Cladosporium (1 %), with 7% of the mould not belonging to the previously mentioned genera. For reed-bale houses, the sequence of genera was the same, with differences in proportions: Penicillium – 70 %, Aspergillus – 19 %, Cladosporium – 6 %, Alternaria – 1 %; 4 % of the found mould did not belong to the previous genera.

Table 3.

Distribution of mould identified to the genus level by season and building material. The first figure indicates the number of colony-forming units (CFU) and the second the percentage (%) of the total.

Table 3.

Distribution of mould identified to the genus level by season and building material. The first figure indicates the number of colony-forming units (CFU) and the second the percentage (%) of the total.

| |

Winter |

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

| |

Straw |

Reed |

Straw |

Reed |

Straw |

Reed |

Straw |

Reed |

| Alternaria |

1 (1) |

4 (1) |

9 (3) |

16 (3) |

32 (6) |

43 (5) |

25 (8) |

49 (9) |

| Aspergillus |

25 (17) |

72 (19) |

24 (8) |

36 (7) |

11 (2) |

9 (1) |

71 (23) |

110 (20) |

| Cladosporium |

1 (1) |

23 (6) |

235 (79) |

420 (81) |

451 (84) |

738 (86) |

92 (30) |

142 (26) |

| Penicillium |

110 (74) |

266 (70) |

24 (8) |

36 (7) |

38 (7) |

51 (6) |

95 (31) |

203 (37) |

| Others |

10 (7) |

15 (4) |

6 (2) |

12 (2) |

5 (1) |

15 (2) |

25 (8) |

44 (8) |

In spring, in buildings with straw-bale walls, most of the identified mould belonged to the genus Cladosporium (79 %). These were followed by the genera Penicillium (8 %), Aspergillus (8 %), and Alternaria (3 %). 2 % of the mould did not belong to the previously mentioned genera. In buildings with reed-bale walls, the sequence of genera in spring was the same as in straw buildings: differences were only in occurrence percentages – Cladosporium (81 %), Penicillium (7 %), Aspergillus (7 %), and Alternaria (3 %). 2 % of the mould did not belong to the previous genera.

In summer, most of the identified mould in the indoor air of buildings with straw-bale walls belonged to the genus Cladosporium (84 %), followed by Penicillium (7 %), Alternaria (6 %), and Aspergillus (2 %); 1 % of the detected mould did not belong to the previously mentioned genera. For the indoor air of buildings with reed-bale walls, the sequence was the same: most moulds belonged to the genus Cladosporium (86 %), followed by the genera Penicillium (6 %), Alternaria (5 %), and Aspergillus (1 %). 2 % of the mould did not belong to the previously mentioned genera. In autumn, most of the mould identified in the indoor air of straw buildings belonged to the genus Penicillium (31 %), followed by the genera Cladosporium (30 %), Aspergillus (23 %), and Alternaria (8 %). 8 % of the mould detected in straw buildings did not belong to the previously mentioned genera. For the indoor air of reed-bale buildings in autumn, most mould belonged to the genus Penicillium (37 %), followed by mould belonging to the genera Cladosporium (26 %), Aspergillus (20 %), and Alternaria (9 %). 4 % of the mould did not belong to any of the previously mentioned genera. The distribution of mould genera identified from outdoor air samples corresponded to the samples taken from the indoor air of the buildings.

3.3. Material Samples from Walls and Identified Mould Genera

Samples collected from the building envelope (walls) in autumn during the study showed that the number of mould colonies was relatively low, ranging from 6 to 14 CFU (colony-forming units). This indicates that the materials in the exterior walls do not provide a favourable environment for mould growth, at least during autumn season.

The distribution of colonies by genus was similar to that found in samples cultivated from indoor air, suggesting that the spread and distribution of mould spores are alike in both indoor and outdoor environments. This may be due to similar environmental conditions or shared mechanisms of mould dispersion.

The identified mould genera showed that Cladosporium and Penicillium were the most common, comprising 36 % and 32 % of all mould colonies, respectively, while Aspergillus made up 25 %, and Alternaria 2 %. These results align with previous studies indicating that Cladosporium and Penicillium are commonly found both indoors and outdoors.

3 % of the mould colonies did not belong to the aforementioned genera, suggesting the presence of other, less common mould genera that may exist in exterior wall materials. Further identification and research of these moulds could provide additional insight into mould spread and distribution in different environments.

4. Discussion

Microorganisms living in environments with high moisture levels require suitable temperatures for their vital activities. Lawrence et al. (2009) point out that the suitable temperature range is 20−70 °C, while temperatures lower than 10°C inhibit microorganism activity [

37]. The average indoor air temperature during the measurement period remained between 19−21 °C, corresponding to indoor climate class III based on the standard EVS-EN 16798-1:2019 [

38]. During the summer period, when temperatures and moisture levels in buildings are higher, microbial growth is possible if unfavourable conditions coincide (high temperature, sufficient relative humidity (above 75 %)) [21, 36]. Mould indicates too high moisture levels in the construction and possible resulting decay. In addition to suitable temperatures, room humidity and nutrients also play an important role in the growth of microorganisms [

39]. The optimal moisture content of living spaces is in the range of 40−60 %, and the critical humidity level from the perspective of microbiological growth is 75−95 %, depending on both temperature and building material [

23]. Hukka and Viitanen highlight in their mould growth model the temporal duration of environmental conditions necessary for the onset of microbiological growth [

36]. In the studied buildings, air humidity remained within the range of 36−44 % and temperature between 19−21 °C. Carbon dioxide level indicators for all studied bedrooms fell within indoor climate class II (≤800ppm) based on the ISO standard EVS-EN 16798-1:2019 [

38]. For the bedrooms of the examined buildings, the air humidity and temperature indicators were too low to expect mould growth.

In buildings with reed-bale walls, the values of colony-forming units (CFU) were higher than in buildings with straw-bale walls, which may indicate possible microbiological growth near the upper junction. If the moisture load is high, it can both deteriorate the indoor climate and cause moisture problems for the building envelope. The indoor air excess moisture was quite low, being higher for buildings with reed-bale walls (0.46 g (m³)⁻¹ to 3.42 g (m³)⁻¹ in summer and 0.62 g (m³)⁻¹ to 2.73 g (m³)⁻¹ in winter) and falling into class II based on the standard EVS-EN ISO 13788:2012. Buildings with straw-bale walls belonged to class I based on their excess moisture according to this standard. For buildings with straw-bale walls, the moisture excess was negative during the winter period on workdays during daytime when residents were not at home. During the winter period, for buildings with reed-bale walls, the average temperature at a height of 0.2 meters was only 7.3±2.5 °C. In such a situation, we would expect the relative humidity to be high, but in this case, it was on average 41±2%. This indicates possible leaks in construction joints, and due to the chimney effect, cold air inflow occurs in this area. Since measurements in the envelope were performed at only two heights (0.2 and 1.2 m), there is a risk that due to the chimney effect, at the upper edge of the envelope, outflow of (warm humid) air is likely due to overpressure, which is a direct risk for mould formation. This finding is concerning because the building envelope is at risk of moisture and, under suitable conditions, microbiological growth in the reed-bale. Samples taken from indoor air on malt extract agar (MEA) show higher values across all seasons compared to samples taken from outdoor air. Different countries use different standards regarding permitted levels of colony-forming units, but there is no common international standard [

40]. A WHO expert group study found that the number of colony-forming units in indoor conditions should not exceed 1000 CFU (m³)⁻¹ [

41]. In Estonia, there are no limit values for mould in indoor environments. Recommended limit values have been established in Finland, stating that in the winter period, up to 500 CFU (m³)⁻¹ is recommended, and in the summer period, up to 2500 CFU (m³)⁻¹ [

42]. In this study, the average concentrations of colony-forming units in indoor air throughout the entire study period remained at a level of 323±80 CFU (m³)⁻¹ for buildings with straw walls and 576±94 CFU (m³)⁻¹ for buildings with reed-bale walls. Samples taken from one building with reed-bale walls in the summer of 2015 [1060±8 CFU (m³)⁻¹] exceeded the recommended concentration for indoor conditions provided by the WHO expert group [1000 CFU (m³)⁻¹], but remained below the limit values recommended in Finland [up to 2500 CFU (m³)⁻¹]. Mould concentrations were higher in indoor air than in outdoor air in all seasons. The mould genera identified from samples taken from the indoor air of buildings did not differ from the fungal genera identified from samples taken from outdoor air. Previous studies have shown that fungal species that can be cultivated from outdoor air may also be cultivated from indoor air [43-45]. In the building envelopes, the concentrations in the measured areas were very low, and the genus distribution of mould was similar to the genera identified from indoor and outdoor air. No significant differences were found in the genus and percentage distribution of mould; autumn concentrations were higher than winter concentrations [

46]. The reason is the suitable temperature and air humidity level for mould growth and development, as well as abundant plant material serving as a substrate [

47]. Similar dynamics in indoor air samples across seasons, as found in the results of this study, have also been established in previous studies concerning building indoor climate [48-50]. The complex approach to studying the indoor climate of buildings with straw- and reed-bale walls helped identify a problematic area in the construction of reed-bale walls, which is apparently due to the insufficient density of reed bales. To verify this finding, further studies are necessary, and a sensor-data logger should also be installed in the envelope near the ceiling (upper junction).

5. Conclusions

Indoor climate data showed that the air temperature was somewhat lower than what is typically expected in living spaces (21 °C). The relative humidity was within the optimal range, and no extremely low temperature values were recorded, which is a common issue during winter in buildings with central heating and good ventilation. CO₂ concentrations did not exceed the recommended limit. The excess moisture in indoor air was minimal, and no conditions suitable for mould growth were found in the indoor air or building envelopes, based on the mould index. Higher values of colony-forming units (CFU) were recorded in buildings with reed-bale walls during the study period. In comparison, buildings with straw-bale walls had lower CFU values. Seasonal variations were observed in both cases.

Based on the conducted studies, it can be said that the indoor air of buildings with straw- and reed-bale walls contains more colonies compared to the outdoor air. No visible mould growth was detected during the visual inspection.

Moulds from four genera were identified (Alternaria, Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Cladosporium), which are the most common mould genera found on cereal crops. These moulds can pose health risks to humans (such as allergies, chronic rhinitis, coughing, and respiratory diseases). The comprehensive approach used in this study made it possible to identify specific problematic areas in reed-bale buildings, where slightly higher mould levels were also observed.

The results obtained from assessing the indoor climate of the studied buildings allow us to conclude that houses built with reed- or straw-bale walls are suitable for the climatic conditions of Estonia. With careful planning, the use of appropriate materials, and quality construction, such buildings can provide healthy and environmentally friendly living conditions. It is essential to conduct similar studies in buildings where moisture damage has occurred.

Author Contributions

J.R.: experiments, manuscript preparation; L.N.: research design, conducting the final draft of the paper; A.R.: research design, supervision of experiments; M.I.: design of microbiological experiments; K.M.: research design, conducting the final version of the manuscript

Funding

This work was supported by Tartu College, Tallinn University of Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- A. Bakkour, S.E. Ouldboukhitine, P. Biwole, S. Amziane, Modeling heat and moisture transfer in bio-based wall structures using the finite element method: Application to straw walls in varied climatic conditions, J. Build. Eng. 104 (2025) 112263. [CrossRef]

- F. Barreca, A.M. Gabarron, J.A.F. Yepes, J.J.P. Pérez, Innovative use of giant reed and cork residues for panels of buildings in Mediterranean area, – Resour. Conserv. Recy. 140 (2019) 259–266. [CrossRef]

- A. Cicelsky, I.A. Meir, A. Peled, Novel insulating construction blocks of crop residue (straw) and natural binders. MRS Energy & Sustainability 11 (2024) 92–106. [CrossRef]

- C.-S. Shon, T. Mukashev, D. Lee, D. Zhang, J. Kim, Can common reed fiber become an effective construction material? Physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of mortar mixture containing common reed fiber, Sustain. 11 (3) (2019) 903. [CrossRef]

- L. Yang, S. Wang, Y. Liu, W. Yanwen, Y. Liu, Towards net zero carbon buildings: Potential use of gypsum-based highland barley straw concrete in solar energy enrichment area of China, Build. Environ. 271 (2025) 112586, . [CrossRef]

- A.D. González, Energy and carbon embodied in straw and clay wall blocks produced locally in the Andean Patagonia. Energy Build. 70 (2014) 15−22. [CrossRef]

- G. Mutani, C. Azzolino, M. Macrì, S. Mancuso, Straw buildings: a good compromise between environmental sustainability and energy-economic savings. Appl. Sci. 10 (8) (2020) 2858. [CrossRef]

- Marques, A. Tadeu, J. Almeida, J. António, J. de Brito, Characterisation of sustainable building walls made from rice straw bales, J. Build. Eng. 28 (2020) 101041. [CrossRef]

- H. Peng, P. Walker, D. Maskell, B. Jones, Structural characteristics of load bearing straw bale Walls, Construct. Build. Mater. 287 (2021) 122911. [CrossRef]

- M. Bouasker, N. Belayachi, D. Hoxha, M. Al-Mukhtar , Physical characterization of natural straw fibers as aggregates for construction materials applications, Materials 7 (4) (2014) 3034-3038. [CrossRef]

- K. Henderson, Achieving legitimacy: visual discourses in engineering design and green building code development. Build. Res. Inf. 35 (1) (2007) 6–17. [CrossRef]

- King, Design of straw bale buildings – the state of the art (2006) 296 p., Green Building Press, San Rafael, CA, ISBN 0-9764911-1-7.

- F. D'Alessandro, F. Bianchi, G. Baldinelli, A. Rotil, S. Schiavoni, Straw bale constructions: Laboratory, in field and numerical assessment of energy and environmental performance, J. Build. Eng. 11 (2017) 56–68. [CrossRef]

- J. Peterková, J. Zach, V. Novák , A. Korjenic, A. Sulejmanovski, E.Sesto, Optimizing indoor microclimate and thermal comfort through sorptive active elements: stabilizing humidity for healthier living spaces, Buildings 14 (12), (2024) 3836. [CrossRef]

- A. Laborel-Préneron, K. Ouédraogo, A. Simons, M. Labat, A. Bertron, C. Magniont, C. Roques, C. Roux , J.-E. Aubert, Laboratory test to assess sensitivity of bio-based earth materials to fungal growth, Build. Environ. 142 (2018) 11−21. [CrossRef]

- M. Meda, V. Gentry, E. Preece, C. Nagy, P. Kumari , P. Wilson, P. Hoffman, Assessment of mould remediation in a healthcare setting following extensive flooding. J. Hospital Infect. 146, (2024) 1−9. [CrossRef]

- Q. Lai, H. Liu, C. Feng, S. Gao, Comparison of mould experiments on building materials: A methodological review. Build. Environ. 261 (2024) 111725. [CrossRef]

- S. Hernberg, P. Sripaiboonkij, R. Quansah, J.J. Jaakkola, M.S. Jaakkola, Indoor moulds and lung function in healthy adults, Respir. Med. 108 (5) (2014) 677–684. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Portnoy, K. Kwak, P. Dowling, T. Vanosdol, C. Barnes, Health effects of indoor fungi, Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 94 (3) (2005) 313–320. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jumeily, K. Hashim, R. Alkaddar, M. Al-Tufaily, J. Lunn, Sustainable and environmental friendly ancient reed houses (inspired by the past to motivate the future), 11th International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering, (2018) 214−219. [CrossRef]

- J. Raamets, S. Kutti, A. Ruus, M. Ivask, Assessment of indoor air in Estonian straw bale and reed houses, WIT Trans. Ecol. Envir. 211 (2017) 193–196. [CrossRef]

- C. Brischke, M. Hanske, Durability of untreated and thermally modified reed (Phragmites australis) against brown, white and soft rot causing fungi, Ind. Crops and Prod. 91 (2016) 49–55. [CrossRef]

- P. Johansson, A. Ekstrand-Tobin, T. Svensson, G. Bok, Laboratory study to determine the critical moisture level for mould growth on building materials, Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 73 (2012) 23–32. [CrossRef]

- ISO 16000-18:2011 Indoor air, Part 18: Detection and enumeration of moulds − sampling by impaction, Edition 1 2011-07. https://www.iso.org/standard/44325.html.

- EVS-ISO 16000-17:2012 Indoor air, Part 17: Detection and enumeration of moulds − culture-based method (ISO 16000-17:2008). https://www.evs.ee/en/evs-iso-16000-17-2012.

- K.H. Domsch, W. Gams, T.H. Anderson, Compendium of soil fungi, Vol. 1 (1980), Academic Press, London, pp. 860.

- M.A. Kilch, A laboratory guide to common Aspergillus species and their teleomorphs (1988), Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Division of Food Processing, North Ryde, Australia, pp. 116.

- D.H. Bergey, J.G. Holt, Bergey's manual of determinative bacteriology (2000), Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA, pp. 787.

- D.H. Larone, Medically important fungi. A Guide to identification, 4th ed. (2002), ASM Press, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, pp. 409.

- W.C. Winn, E.W. Koneman, Koneman's color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology. 6th ed. (2006), Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA, pp. 1565.

- T. Watanabe, Pictorial Atlas of Soil and Seed Fungi, Morphologies of Cultured Fungi and Key to Species. (2010), CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, pp. 426. [CrossRef]

- Caillaud, B. Leynaert, M. Keirsbulck, R. Nadif, Indoor mould exposure, asthma and rhinitis: findings from systematic reviews and recent longitudinal studies, Eur. Respir. Rev. 27 (148) (2018) 170137. [CrossRef]

- J. Raamets, S. Kutti, A. Vettik, K. Ilustrumm, T. Rist, M. Ivask, The antimicrobial effect of three different chemicals for the treatment of straw bales used in housing projects, Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Housing Planning, Management and Usability, (2016) 537−545, Green Lines Institute for Sustainable Development, Porto, Portugal.

- Keskkonnaagentuur (Estonian Environment Agency) (2020) Ilmaülevaated (Weather observations). Downloaded: 30.01.2020. (in Estonian). https://www.ilmateenistus.ee/kliima/ulevaated/.

- EVS-EN ISO 13788:2012 Hygrothermal performance of building components and building elements - internal surface temperature to avoid critical surface humidity and interstitial condensation - calculation methods (ISO 13788:2012). https://www.evs.ee/en/evs-en-iso-13788-2012.

- A. Hukka, H. Viitanen, A mathematical model of mould growth on wooden material, Wood Sci. Technol. 33 (1999) 475–485. [CrossRef]

- M. Lawrence, A. Heath, P. Walker, Determining moisture levels in straw bale, Construction, Const. Build. Mat. 23 (8) (2009) 2763–2768. [CrossRef]

- EVS-EN 16798-1:2019 Energy performance of buildings - Ventilation for buildings - Part 1: Indoor environmental input parameters for design and assessment of energy performance of buildings addressing indoor air quality, thermal environment, lighting and acoustics - Module M1-6, Eesti Standardimis- ja Akrediteerimiskeskus MTÜ (Estonian Centre for Standardisation and Accreditation). https://www.evs.ee/en/evs-en-16798-1-2019.

- A. Rajasekar, R. Balasubramanian, Asessment of airborne bacteria and fungi in food courts, Build. Environ. 46 (10) (2011) 2081–2087. [CrossRef]

- M. Jyotshna, B. Helmut, Bioaerosols in indoor environment - a review with special reference to residential and occupational locations, The Open Envir. & Biol. Mon. J. 4 (1) (2011) 83–96. [CrossRef]

- Biological Agents in Indoor Environments. Assessment of Health Risks. – Work conducted by a WHO Expert Group between 2000–2003, A. Nevalainen, L. Morawaska, (Eds.) (2009) WHO, QUT, pp. 201.

- Kosteusvauriot työpaikoilla. Kosteusvauriotyöryhmän muistio. Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriön selvityksiä 18 (2009) pp. 82 (Reports of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health : 2009:18), Yliopistopaino, Helsinki, (in Finnish).

- M. Hoseini, H. Jabbari, R. Naddafi, M. Nabizadeh, M. Rahbar, M. Yunesian, J. Jaafari, Concentration and distribution characteristics of airborne fungi in indoor and outdoor air of Tehran subway stations, Aerobiol. 29 (2012) 355–363. [CrossRef]

- A. Kalwasinska, A. Burkowska, I. Wilk, Microbial air contamination in indoor environment of a University library, Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 19 (1) (2012) 25–29.

- J. Raamets, A. Ruus, M. Ivask, Assessment of indoor air quality and hygrothermal conditions of boarders during autumn, winter and spring in two of Estonian straw-bale houses. In: Johansson, D., Bagge, H., Wahlström, Å. (eds) Cold Climate HVAC 2018. CCC 2018. Springer Proceedings in Energy. Springer, Cham. (2019) 815–823. [CrossRef]

- A.A.A. Hameed, M.I. Khoder, Y.H. Ibrahim, Y. Saeed, M.E. Osman, S. Ghanem, Study on some factors affecting survivability of airborne fungi, Sci. Total Environ. 414 (2012) 696–700. [CrossRef]

- A.H. Awad, Y. Saeed, Y. Hassan, Y. Fawzy, M. Osman, Air microbial quality in certain public buildings, Egypt: a comparative study, Atmos. Pollut. Res. 9 (2018) 617–626. [CrossRef]

- Medrela-Kuder, Seasonal variations in the occurrence of culturable airborne fungi in outdoor and indoor air in Craców, Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 52 (4) (2003) 203–205. [CrossRef]

- D. Haas, J. Habib, H. Galler, W. Buzina, R. Schlacher, E. Marth, F. Reinthaler, Assessment of indoor air in Austrian apartments with and without visible mould growth, Atmos. Environ. 41 (25) (2007) 5192–5201. [CrossRef]

- M. Frankel, G. Bekö, M. Timm, S. Gustavsen, E.W. Hansen, A.M. Madsen, Seasonal variations of indoor microbial exposures and their relation to temperature, relative humidity, and air exchange rate, App. Environ. Microbiol. 78 (23) (2012) 8289–8297. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).