Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

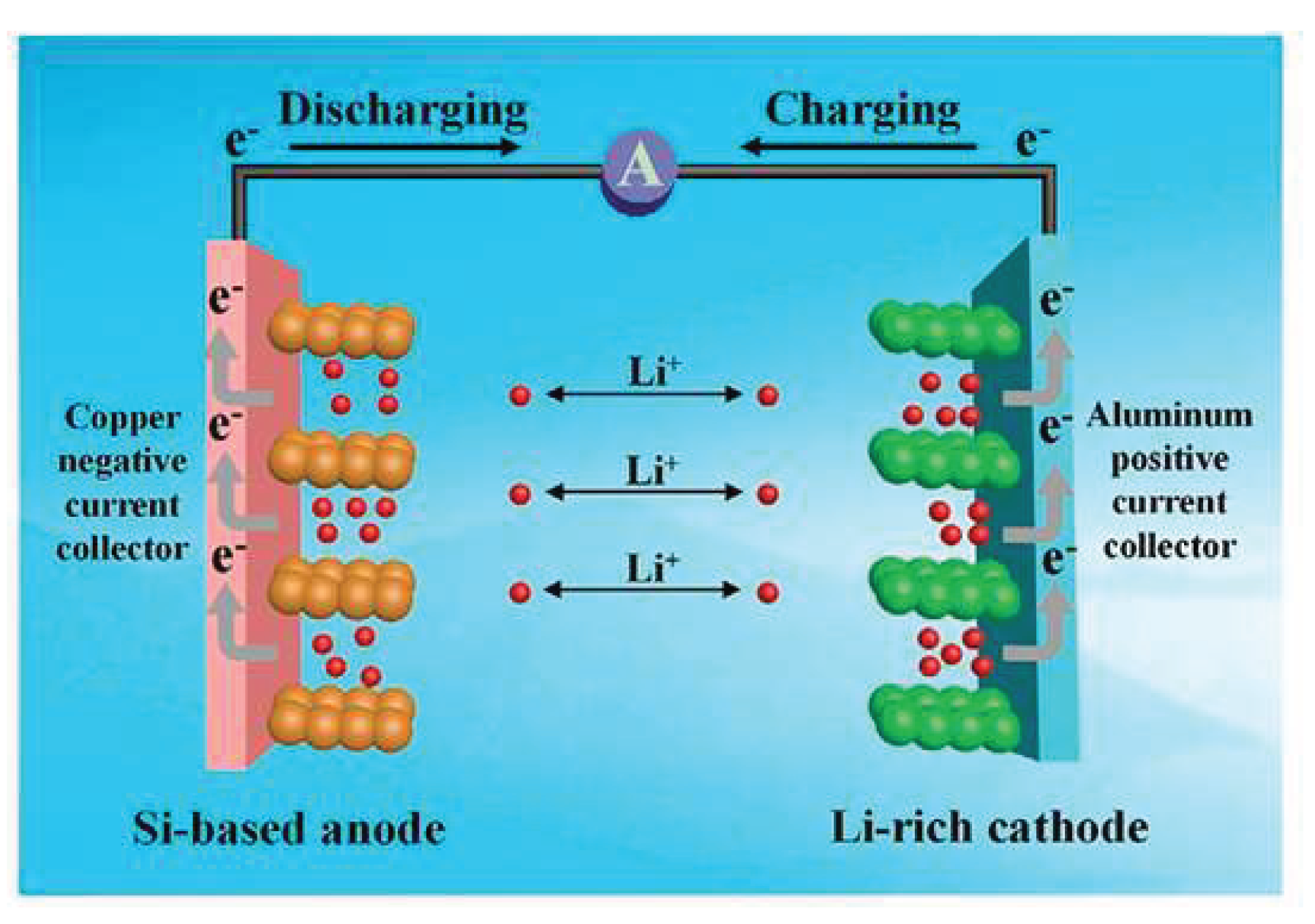

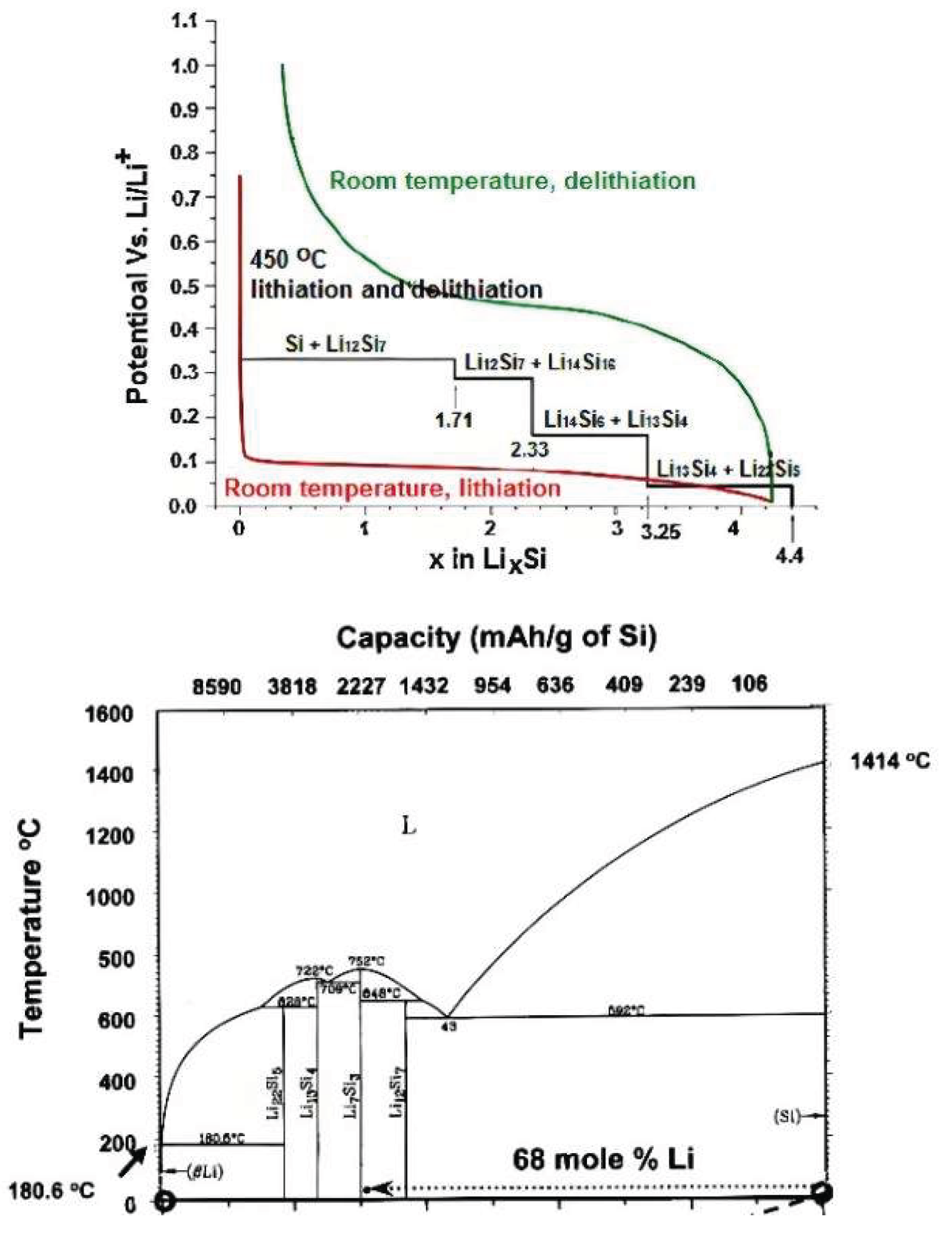

1. Introduction

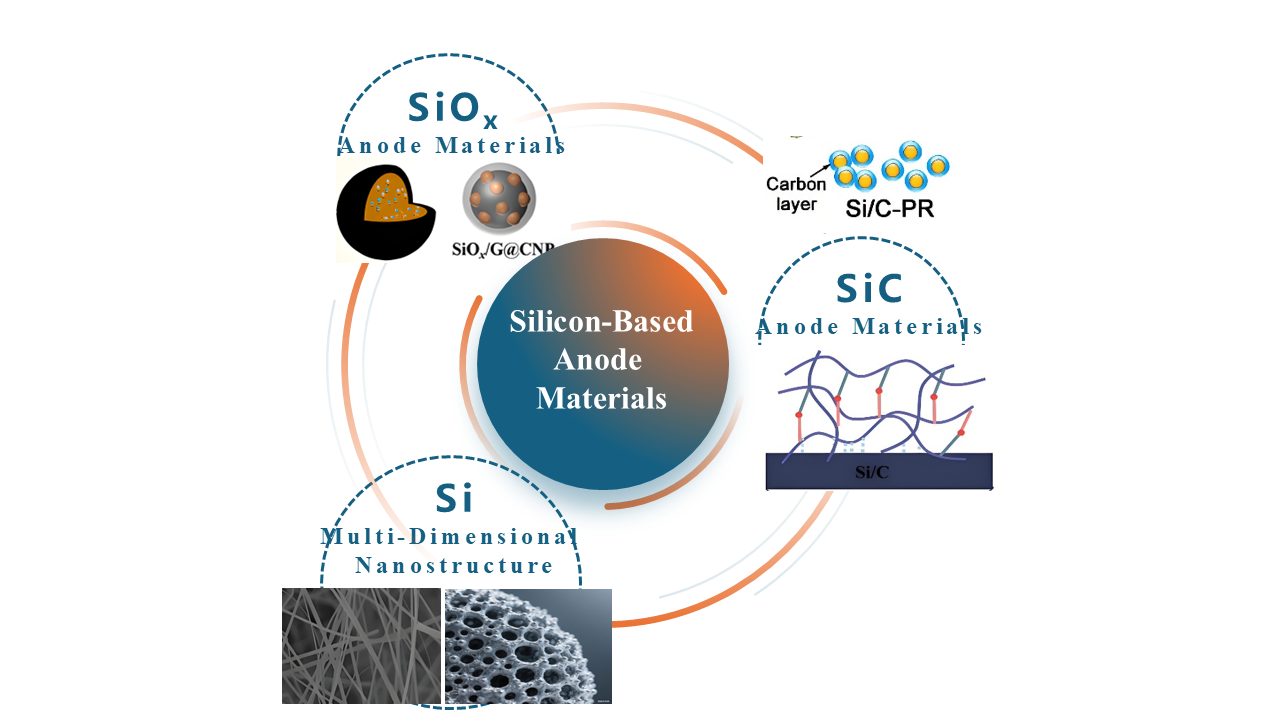

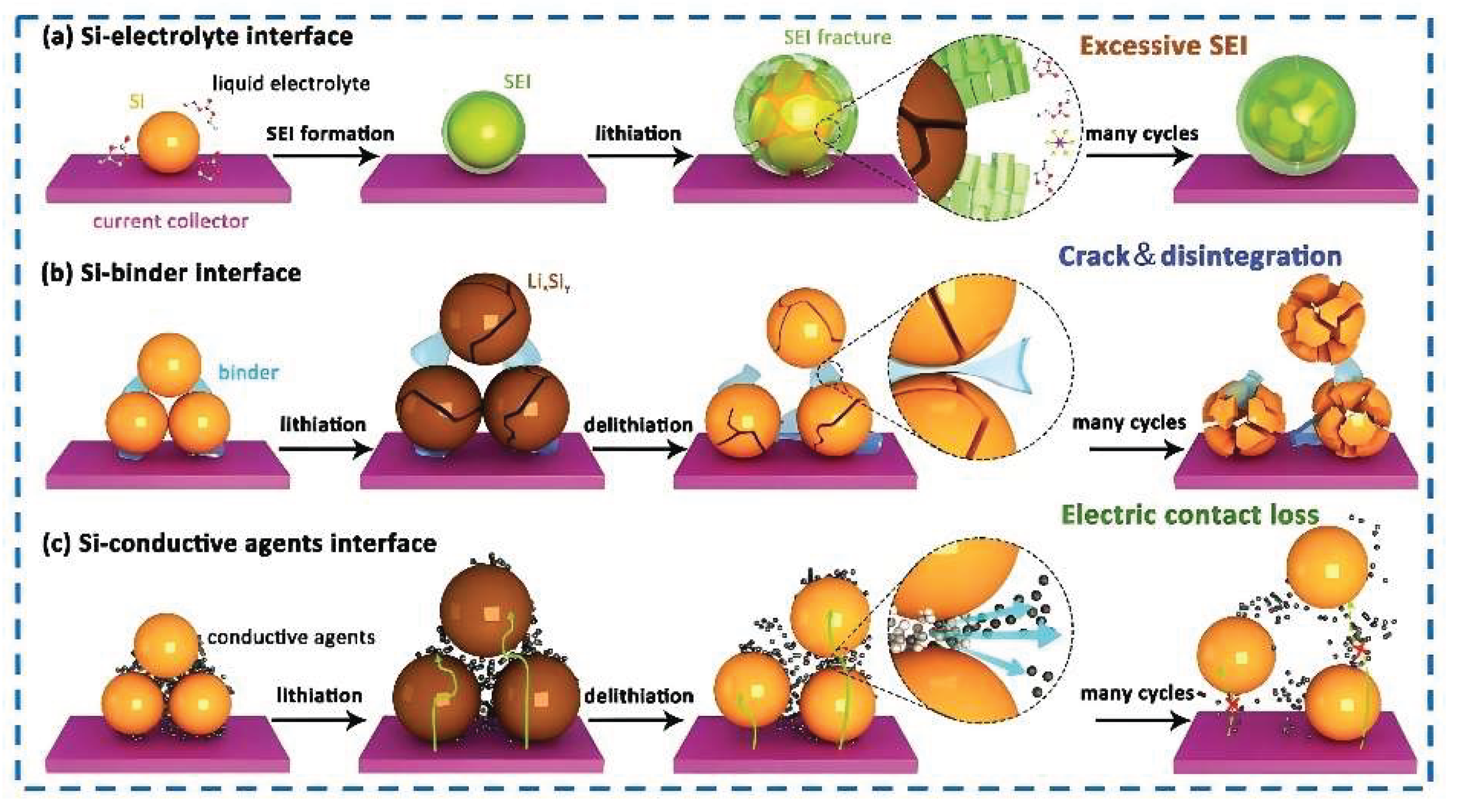

2. Mechanism of Expansion-Induced Failure in Silicon-Based Anode Materials

3. Modification Design and Optimization of Silicon-Based Anode Materials

3.1. Multi-Dimensional Nanostructured Silicon Materials

3.1.1. Zero-Dimensional Nanostructured Silicon Materials

3.1.2. One-Dimensional Silicon Nanostructures

3.1.3. Two-Dimensional Nanostructures

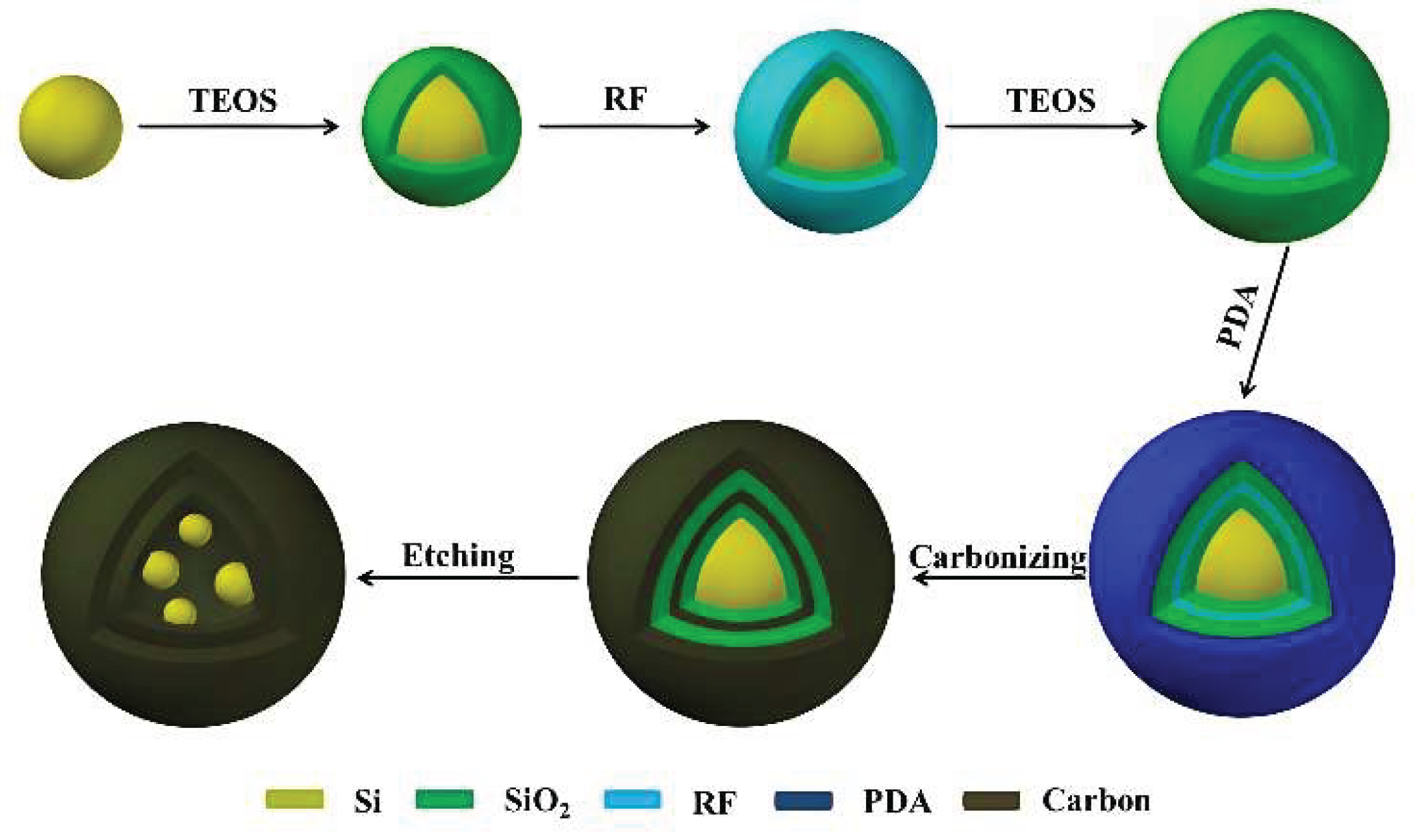

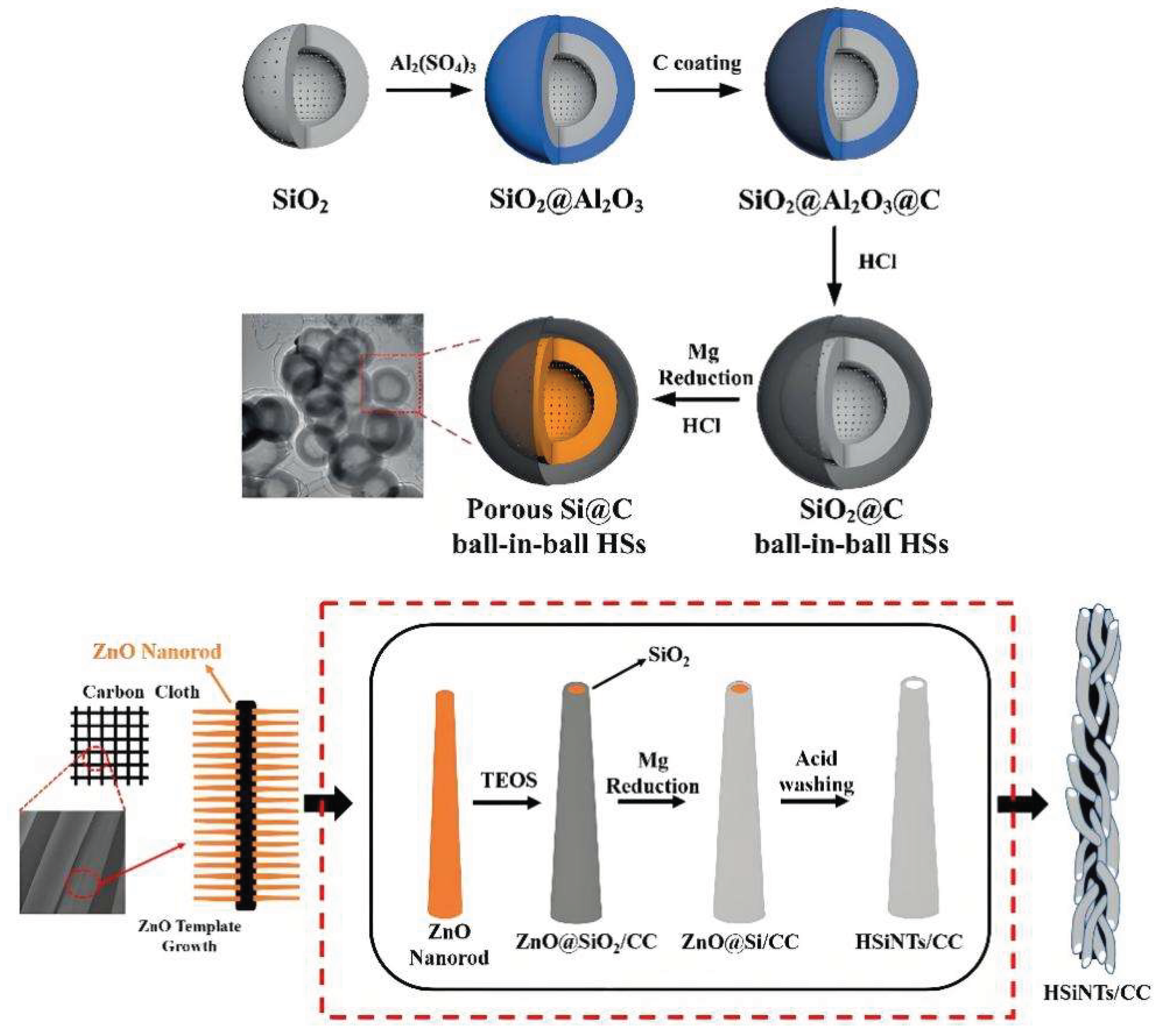

3.1.4. Secondary Structural Design of Silicon Nanomaterials

3.2. SiC Anode Materials

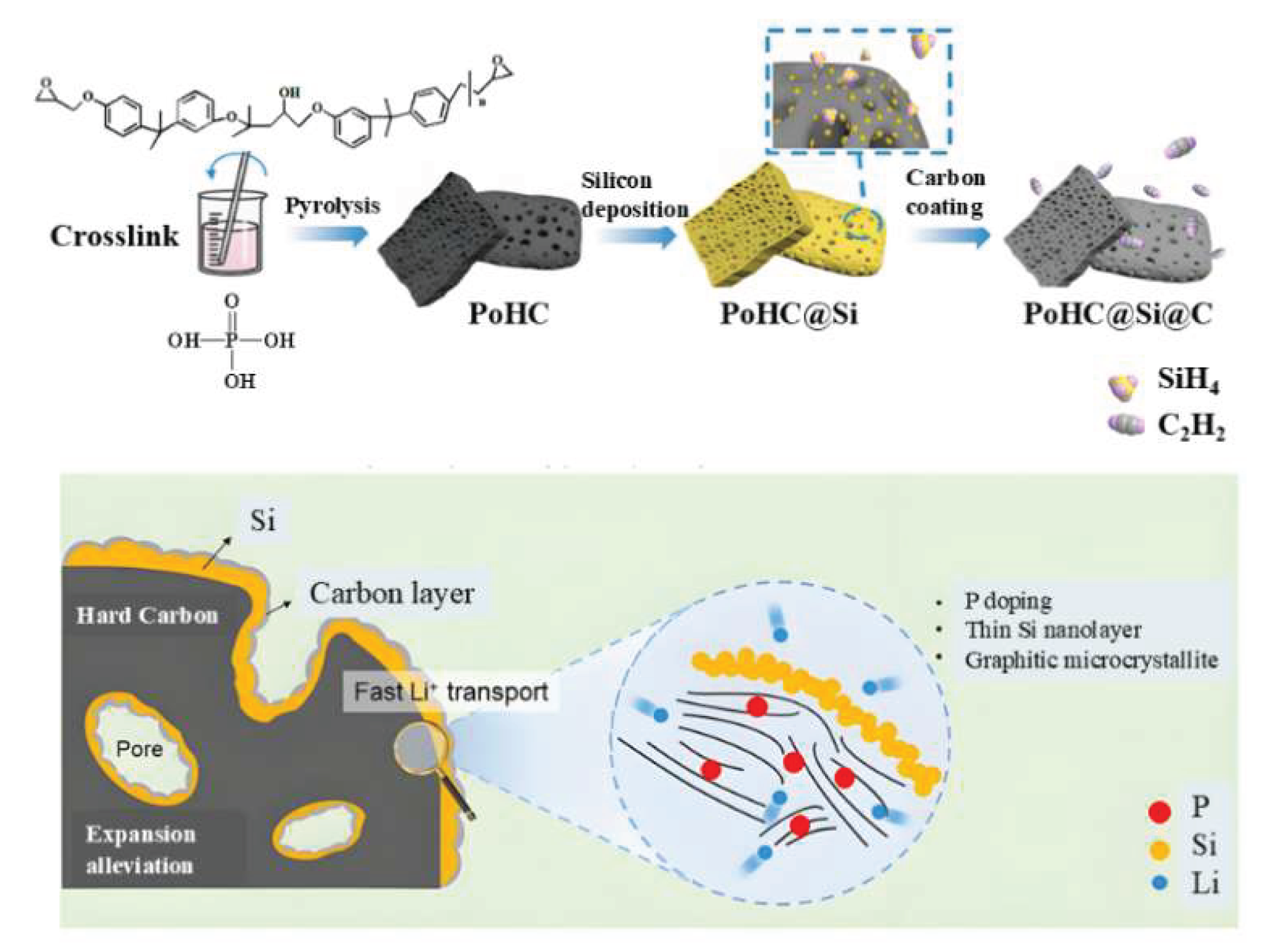

3.2.1. Mechanical Mixing Method

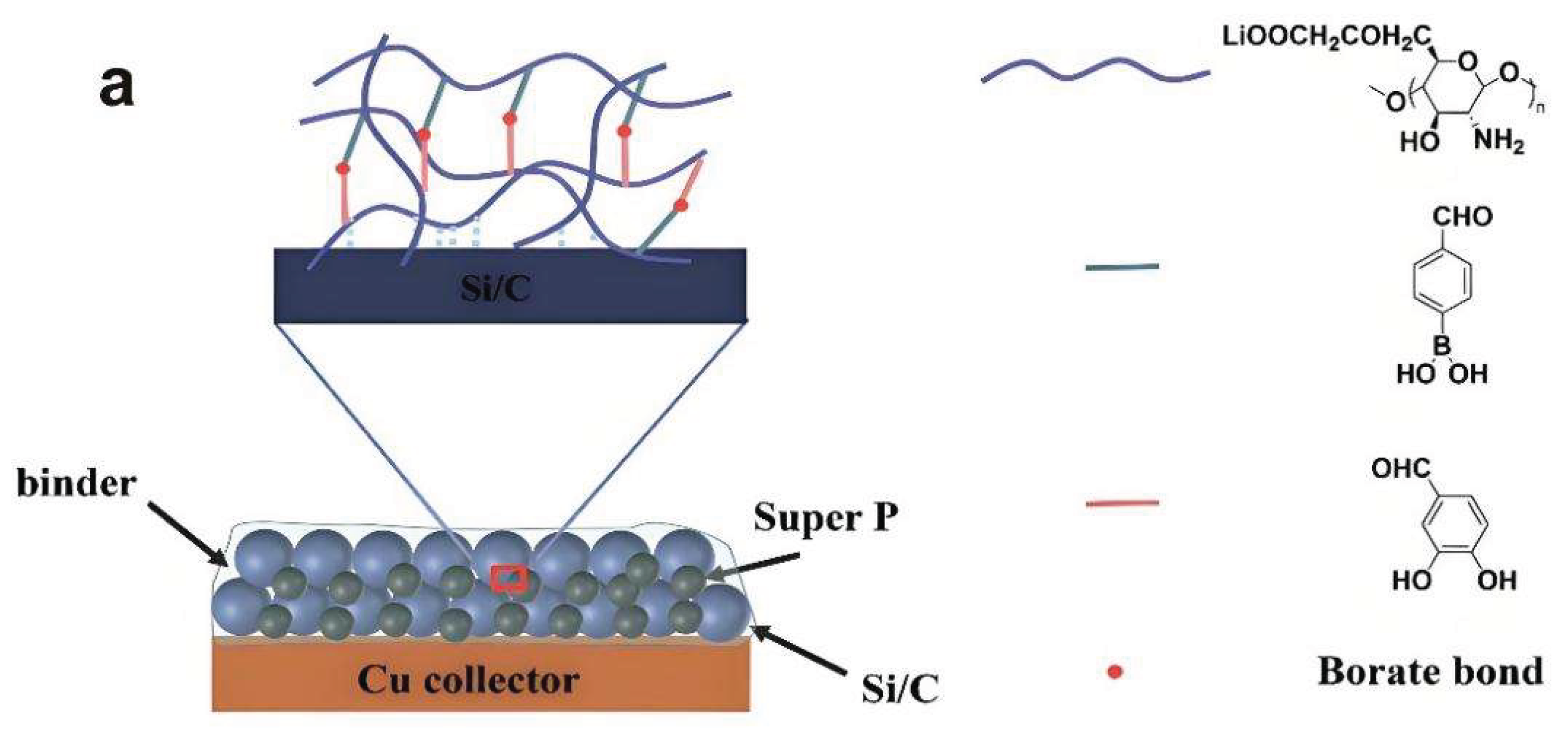

3.2.2. Binder Design

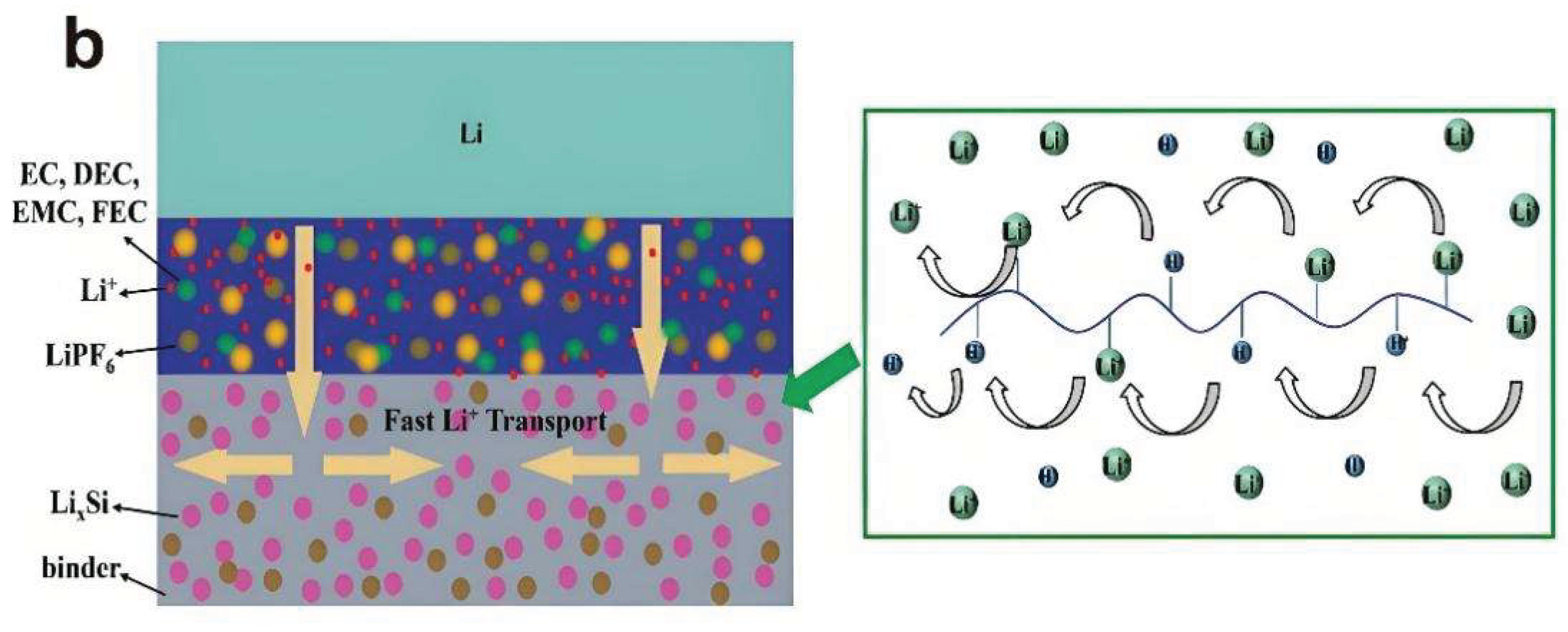

3.2.3. Chemical Vapor Deposition Method

3.2.4. Structural Design Optimization

3.3. SiOx Anode Materials

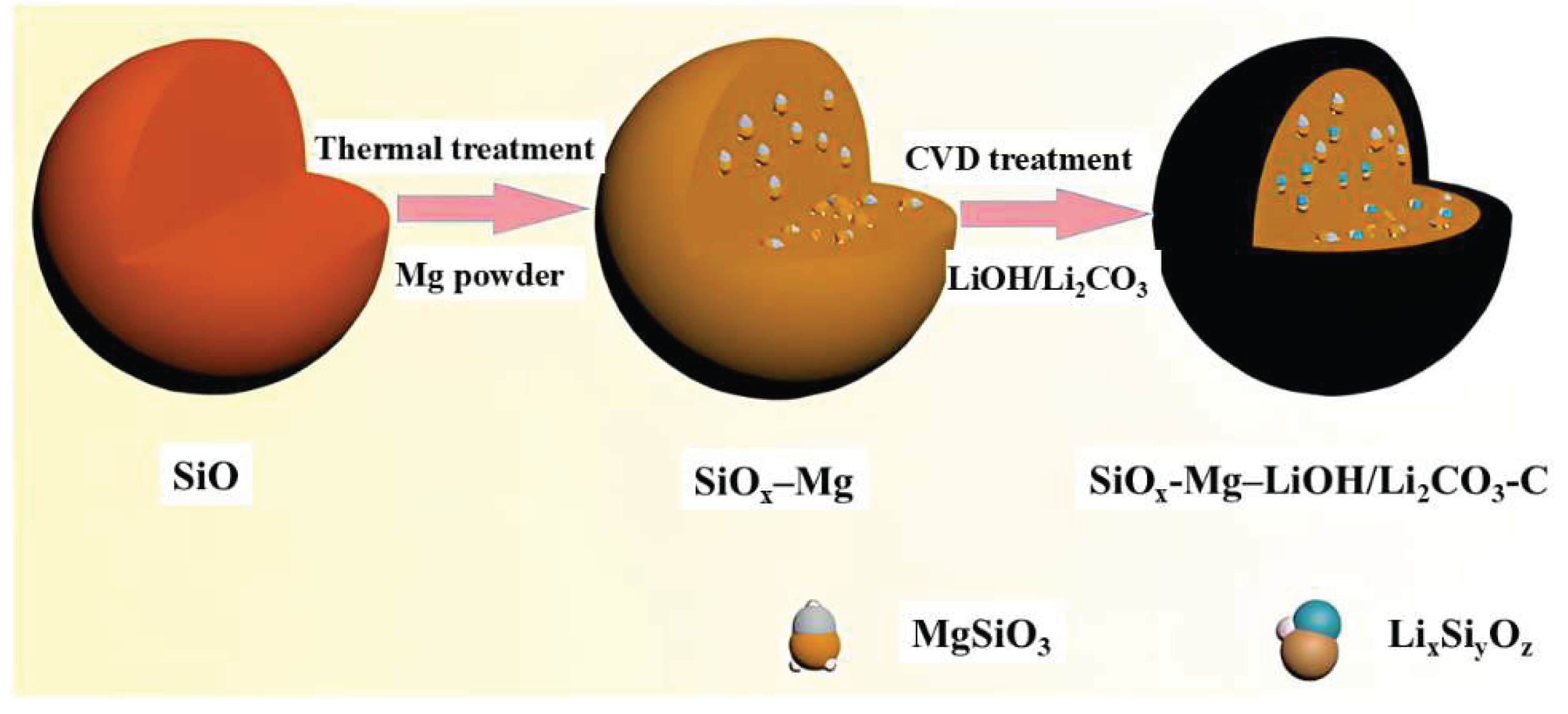

3.3.1. Pre-lithiation of SiOx

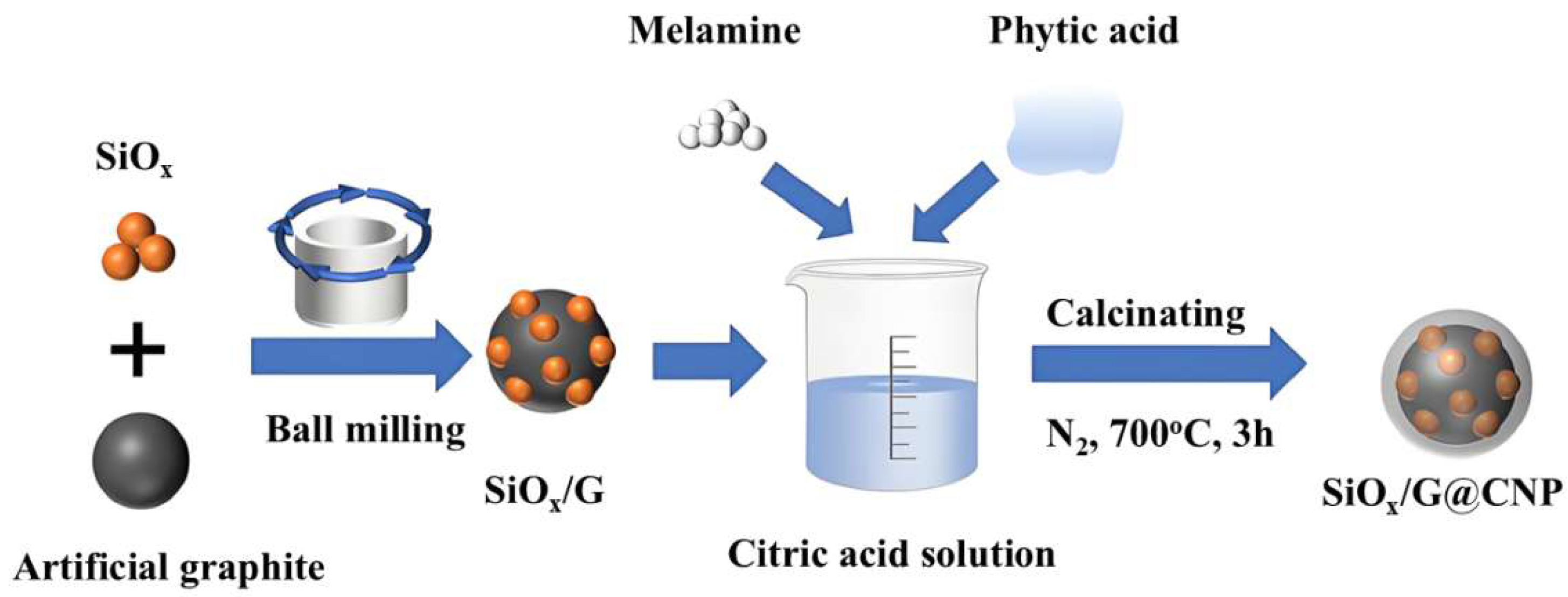

3.3.2. Modification of SiOx Materials

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LIBs | Lithium-ion batteries |

| SEI | Solid electrolyte interphase |

| ICE | Initial coulombic efficiency |

| CVD | Chemical vapor deposition |

References

- Li L.; Zhang X.; Li M.; Chen R.; Wu F.; Amine K.; Lu J. The recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries: a review of current processes and technologies. Electro. Ener. Rev. 2018, 1, 461-482.

- Xu J.; Cai X.; Cai S.; Shao Y.; Hu C.; Lu S.; Ding S. High-energy lithium-ion batteries: recent progress and a promising future in applications. Energy Environ. Mater. 2023, 6, e12450.

- Fang R.; Chen K.; Yin L.; Sun Z.; Li F.; Cheng H. The regulating role of carbon nanotubes and graphene in lithium-ion and lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1800863.

- Zhao H.; Zuo H.; Wang J.; Jiao S. Practical application of graphite in lithium-ion batteries: modification, composite, and sustainable recycling. J. Energy Storage 2024, 98, 113125.

- Peng J.; Li W.; Wu Z.; Li H.; Zeng P.; Yang J.; Hu S.; Chen G.; Chang B.; Wang X. Engineering Si-based anode materials with homogeneous distribution of SiOx and carbon for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 5465-5474.

- Tao W.; Wang P.; You Y.; Park K.; Wang C.; Li Y.; Cao F.; Xin S. Strategies for improving the storage performance of silicon-based anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Nano Res. 2019, 12, 1739-1749.

- Kwon T.; Choi J. W.; Coskun A. Prospect for supramolecular chemistry in high-energy-density rechargeable batteries. Joule 2019, 3 662-682.

- Xu X.; Zhang H.; Chen Y.; Li N.; Li Y.; Liu L. SiO2@SnO2/graphene composite with a coating and hierarchical structure as high performance anode material for lithium ion battery. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 677, 237-244.

- McBrayer J. D.; Rodrigues M. T. F.; Schulze M. C.; Abraham D. P.; Apblett C. A.; Bloom I.; Carroll G. M.; Colclasure A. M.; Fang C.; Harrison K. L.; Liu G.; Minteer S. D.; Neale N. R.; Veith G. M.; Johnson C. S.; Vaughey J. T.; Burrell A. K.; Cunningham B. Calendar aging of silicon-containing batteries. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 866-872.

- Sunghun Choi T. K.; Coskun A.; Choi J. W. Highly elastic binders integrating polyrotaxanes for silicon microparticle anodes in lithium ion batteries. Science 2017, 357 279–283.

- Wang C.; Wen J.; Luo F.; Quan B.; Li H.; Wei Y.; Gu C.; Li J. Anisotropic expansion and size-dependent fracture of silicon nanotubes during lithiation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7 15113-15122.

- Pan H.; Wang L.; Shi Y.; Sheng C.; Yang S.; He P.; Zhou H. A solid-state lithium-ion battery with micron-sized silicon anode operating free from external pressure. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2263.

- Kang W.; Zhang Q.; Jia Y.; Liu X.; Jiang N.; Zhao Y.; Wu C.; Guan L. Enhancing the cycling stability of commercial silicon nanoparticles by carbon coating and thin layered single-walled carbon nanotube webbing. J. Power Sources 2024, 602, 234338.

- Huo H.; Jiang M.; Bai Y.; Ahmed S.; Volz K.; Hartmann H.; Henss A.; Singh C.V.; Raabe D.; Janek J. Chemo-mechanical failure mechanisms of the silicon anode in solid-state batteries. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 543-551.

- Zhu X.; Meng F.; Zhang Q.; Xue L.; Zhu H.; Lan S.; Liu Q.; Zhao J.; Zhuang Y.; Guo Q.; Liu B.; Gu L.; Lu X.; Ren Y.; Xia H. LiMnO2 cathode stabilized by interfacial orbital ordering for sustainable lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 392-401.

- Manthiram A. A reflection on lithium-ion battery cathode chemistry. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1550.

- Hou X.; Liu X.; Wang H.; Zhang X.; Zhou J.; Wang M. Specific countermeasures to intrinsic capacity decline issues and future direction of LiMn2O4 cathode. Energy Storage Mater. 2023, 57, 577-606.

- Lee S.; Su L.; Mesnier A.; Cui Z.; Manthiram A.; Cracking vs. surface reactivity in high-nickel cathodes for lithium-ion batteries. Joule 2023, 7, 2430-2444.

- Chen S.; Lv D.; Chen J.; Zhang Y.; Shi F. Review on defects and modification methods of LiFePO4 cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Energ. Fuel. 2022, 36, 1232-1251.

- Ling J.; Karuppiah C.; Krishnan S. G.; Reddy M. V.; Misnon I. I.; Ab Rahim M. H.; Yang C. C.; Jose R. Phosphate polyanion materials as high-voltage lithium-ion battery cathode: a review. Energ. Fuel. 2021, 35, 10428-10450.

- Wani T. A.; Suresh G. A comprehensive review of LiMnPO4 based cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries: current strategies to improve its performance. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103307.

- Ge M.; Cao C.; Biesold G.M.; Sewell C.D.; Hao S.M., Huang J.; Zhang W.; Lai Y.; Lin Z. Recent advances in silicon-based electrodes: from fundamental research toward practical applications. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2004577.

- Divakaran A.M.; Minakshi M.; Bahri P.A.; Paul S.; Kumari P.; Divakaran A.M.; Manjunatha K.N. Rational design on materials for developing next generation lithium-ion secondary battery. Prog. Solid State Ch. 2021, 62, 100298.

- Xu Z. L.; Liu X.; Luo Y.; Zhou L.; Kim J.-K. Nanosilicon anodes for high performance rechargeable batteries. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 90, 1-44.

- Lin M. C.; Gong M.; Lu B.; Wu Y.; Wang D. Y.; Guan M.; Angell M.; Chen C.; Yang J.; Hwang B.-J.; Dai H. An ultrafast rechargeable aluminium-ion battery. Nature 2015, 520, 324-328.

- Zhang H.; Li C.; Eshetu G. G.; Laruelle S.; Grugeon S.; Zaghib K.; Julien C.; Mauger A.; Guyomard D.; Rojo T.; Gisbert-Trejo N.; Passerini S.; Huang X.; Zhou Z.; Johansson P.; Forsyth M. From solid-solution electrodes and the rocking-chair concept to today’s batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 59, 534-538.

- Huggins R.A. Lithium alloy negative electrodes. J. Power Sources 1999, 81-82, 13-19.

- Johari P.; Qi Y.; Shenoy V. B. The mixing mechanism during lithiation of Si negative electrode in Li-ion batteries: an ab initio molecular dynamics study. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5494-5500.

- Wu H.; Cui Y. Designing nanostructured Si anodes for high energy lithium ion batteries. Nano Today 2012, 7, 414-429.

- Hossain M.A.M.; Hannan M.A.; Ker P.J.; Tiong S.K.; Salam M.A.; Abdillah M.; Mahlia T.M.I. Silicon-based nanosphere anodes for lithium-ion batteries: Features, progress, effectiveness, challenges, and prospects. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113371.

- Wang L.; Yu J.; Li S.; Xi F.; Ma W.; Wei K.; Lu J.; Tong Z.; Liu B.; Luo B. Recent advances in interface engineering of silicon anodes for enhanced lithium-ion battery performance. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 66, 103243.

- Obrovac M.N.; Christensen L. Structural changes in silicon anodes during lithium insertion extraction. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2004, 7, A93-A96.

- Limthongkul P.; Jang Y.-I.; Dudney N.J.; Chiang Y.-M. Electrochemically-driven solid-state amorphization in lithium-silicon alloys and implications for lithium storage. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 1103-1113.

- Obrovac M. N.; Krause L. J. Reversible cycling of crystalline silicon powder. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 154, A103-A108.

- Zhao X.; Lehto V.-P. Challenges and prospects of nanosized silicon anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Nanotechnology 2020, 32, 042002.

- Chan K.S.; Liang W.-W.; Chan C.K. First-principles studies of the lithiation and delithiation paths in Si anodes in Li-ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 22775-22786.

- Limthongkul P.; Jang Y.-I.; Dudney N.J.; Chiang Y.-M. Electrochemically-driven solid-state amorphization in lithium–metal anodes. J. Power Sources 2003, 119-121, 604-609.

- Liu X.H.; Wang J.W.; Huang S.; Fan F.; Huang X.; Liu Y.; Krylyuk S.; Yoo J.; Dayeh S.A.; Davydov A.V.; Mao S.X.; Picraux S.T.; Zhang S.; Li J.; Zhu T.; Huang J.Y. In situ atomic-scale imaging of electrochemical lithiation in silicon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 749-756.

- Baris Key R.B.; Morcrette M.; Seznéc V.; Tarascon J.-M.; Grey C. P. Real-time NMR investigations of structural changes in silicon electrodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9239–9249.

- McDowell M.T.; Lee S.W.; Nix W.D.; Cui Y. 25th Anniversary article: Understanding the lithiation of silicon and other alloying anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 4966-4985.

- Gu M.; He Y.; Zheng J.; Wang C.; Nanoscale silicon as anode for Li-ion batteries: The fundamentals, promises, and challenges. Nano Energy 2015, 17, 366-383.

- Ding N.; Xu J.; Yao Y.X.; Wegner G.; Fang X.; Chen C.H.; Lieberwirth I. Determination of the diffusion coefficient of lithium ions in nano-Si. Solid State Ionics 2009, 180, 222-225.

- Bordes A.; De Vito E.; Haon C.; Boulineau A.; Montani A.; Marcus P. Multiscale investigation of silicon anode Li insertion mechanisms by Time-of-Flight secondary ion mass spectrometer imaging performed on an in situ focused ion beam cross section. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 1566-1573.

- Gu M.; Wang Z.; Connell J. G.; Perea D. E.; Lauhon L. J.; Gao F.; Wang C. Electronic origin for the phase transition from amorphous LixSi to crystalline Li15Si4. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 6303–6309.

- Wang C.; Li X.; Wang Z.; Xu W.; Liu J.; Gao F.; Kovarik L.; Zhang J.; Howe J.; Burton D.J.; Liu Z.; Xiao X.; Thevuthasan S.; Baer D.R. In Situ TEM investigation of congruent phase transition and structural evolution of nanostructured silicon/carbon anode for lithium ion batteries. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 1624-1632.

- Liu X.; Zheng H.; Zhong L.; Huang S.; Karki K.; Zhang L., Liu Y.; Kushima A.; Liang W.; Wang J.; Cho J.-H.; Epstein E.; Dayeh S. A.; Picraux S.T.; Zhu T.; Li J.; Sullivan J.P.; Cumings J.; Wang C.; Mao S.; Ye Z.; Zhang S.; Huang J. Anisotropic swelling and fracture of silicon nanowires during lithiation. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3312-3318.

- Liu X.; Zhang L.; Zhong L.; Liu Y.; Zheng H.; Wang J.; Cho J.-H.; Dayeh S.A.; Picraux S.T.; Sullivan J.P.; Mao S.; Ye Z.; Huang J. Ultrafast electrochemical lithiation of individual Si nanowire anodes. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 2251-2258.

- Kang Y.-M.; Lee S.-M.; Kim S.-J.; Jeong G.-J.; Sung M.-S.; Choi W.-U.; Kim S.-S. Phase transitions explanatory of the electrochemical degradation mechanism of Si based materials. Electrochem. Commun. 2007, 9, 959-964.

- Sumohan Misra N.L.; Nelson J.; Sae Hong S.; Cui Y.; Toney M. F. In situ X-ray diffraction studies of (De)lithiation mechanism in silicon nanowire anodes. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5465–5473.

- McDowell M.T.; Lee S.W.; Harris J.T.; Korgel B.A.; Wang C.; Nix W.D.; Cui Y. In situ TEM of two-phase lithiation of amorphous silicon nanospheres. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 758-764.

- Baris Key M.M.; Tarascon J.-M.; Grey C. P. Pair distribution function analysis and solid state NMR studies of silicon electrodes for lithium ion batteries Understanding the (de)lithiation mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 503–512.

- Li Y.; Li Q.; Chai J.; Wang Y.; Du J.; Chen Z.; Rui Y.; Jiang L.; Tang B. Si-based anode lithium-ion batteries: a comprehensive review of recent progress. ACS Mater. Lett. 2023, 5, 2948-2970.

- Liu X.; Zhong L.; Huang S.; Mao S. X.; Zhu T.; Huang J. Size-dependent fracture of silicon nanoparticles during lithiation. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 1522–1531.

- Wu X.; Pan K.; Jia M.; Ren Y.; He H.; Zhang L.; Zhang S. Electrolyte for lithium protection: From liquid to solid. Green Energy Environ. 2019, 4, 360-374.

- Dupré N.; Moreau P.; De Vito E.; Quazuguel L.; Boniface M.; Bordes A.; Rudisch C.; Bayle-Guillemaud P.; Guyomard D. Multiprobe study of the solid electrolyte interphase on silicon-based electrodes in full-cell configuration. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 2557-2572.

- Huang J.; Liu X.; Liu Y.; Kushima A.; Li J.; Zhu T. In-situ TEM experiments of electrochemical lithiation and delithiation of individual nanostructures. Microsc. Microanal. 2012, 18, 1326-1327.

- Luo F.; Liu B.; Zheng J.; Chu G.; Zhong K.; Li H.; Huang X.; Chen L. Review-nano-silicon carbon composite anode materials towards practical application for next generation Li-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, A2509-A2528.

- Xu C.; Lindgren F.; Philippe B.; Gorgoi M.; Björefors F.; Edström K.; Gustafsson T. Improved performance of the silicon anode for Li-ion batteries: Understanding the surface modification mechanism of fluoroethylene carbonate as an effective electrolyte additive. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 2591-2599.

- Luo W.; Chen X.; Xia Y.; Chen M.; Wang L.; Wang Q.; Li W.; Yang J. Surface and interface engineering of silicon-based anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7 1701083.

- Fan S.; Wang H.; Qian J.; Cao Y. ; Yang H.; Ai X. ; Zhong F. Covalently bonded silicon/carbon nanocomposites as cycle-stable anodes for Li-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2020, 12, 16411-16416.

- Li Y.; Lv L.; Huang W. ; Zhu Y.; Long F.; Zheng W.; Qu Q.; Zheng H. In situ polymerized and imidized Si@Polyimide microcapsules with flexible solid-electrolyte interphase and enhanced electrochemical activity for Li-storage. ChemElectroChem 2022, 9, e202101409.

- An W.; He P.; Che Z.; Xiao C.; Guo E.; Pang C.; He X.; Ren J.; Yuan G.; Du N.; Yang D.; Peng D.-L.; Zhang Q. Scalable synthesis of pore-rich Si/C@C core–shell-structured microspheres for practical long-life Lithium-ion battery anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2022, 14, 10308-10318.

- Mu G.; Ding Z.; Mu D.; Wu B.; Bi J.; Zhang L.; Yang H.; Wu H.; Wu F. Hierarchical void structured Si/PANi/C hybrid anode material for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Electroch. Acta 2019, 300, 341-348.

- Lu J.; Liu J.; Gong X.; Wang Z. Fe3C doped modified nano-Si/C composites as high-coulombic-efficiency anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Sustain. Energ. Fuels 2021, 5, 6170-6180.

- Yao Y.; McDowell M.T.; Ryu I.; Wu H.; Liu N.; Hu L.; Nix W. D.; Cui Y. Interconnected silicon hollow nanospheres for lithium-ion battery anodes with long cycle life. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 2949-2954.

- Ge M.; Rong J.; Fang X.; Zhang A.; Lu Y.; Zhou C. Scalable preparation of porous silicon nanoparticles and their application for lithium-ion battery anodes, Nano Res. 2013, 6, 174-181.

- Yang Y.; Wu S.; Chiu H.; Lin P.; Chen Y. Catalytic growth of silicon nanowires assisted by laser ablation, J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108 846-852.

- Chan C.K.; Peng H.; Liu G.; McIlwrath K.; Zhang X. F.; Huggins R.A.; Cui Y. High-performance lithium battery anodes using silicon nanowires. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 31-35.

- Ortaboy S.; Alper J. P.; Rossi F.; Bertoni G.; Salviati G.; Carraro C.; Maboudian R. MnOx-decorated carbonized porous silicon nanowire electrodes for high performance supercapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1505-1516.

- Lu J.; Liu J.; Gong X.; Pang S.; Zhou C.; Li H.; Qian G.; Wang Z. Upcycling of photovoltaic silicon waste into ultrahigh areal-loaded silicon nanowire electrodes through electrothermal shock. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 46, 594-604.

- Lu Z.; Wong T.; Ng T.-W.; Wang C. Facile synthesis of carbon decorated silicon nanotube arrays as anode material for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 2440-2446.

- Tong L.; Wang P.; Chen A.; Qiu F.; Fang W.; Yang J.; Wang C.; Yang Y. Improved electrochemical performance of binder-free multi-layered silicon/carbon thin film electrode for lithium-ion batteries. Carbon 2019, 153, 592-601.

- Liao L.; Ma T.; Xiao Y.; Wang M.; Cao Y.; Fang T. Enhanced reversibility and cyclic stability of biomass-derived silicon/carbon anode material for lithium-ion battery. J Alloy. Compd. 2021, 873, 159700.

- Hwang T.H.; Lee Y.M.; Kong B.-S.; Seo J.-S.; Choi J.W. Electrospun core–shell fibers for robust silicon nanoparticle-based lithium ion battery anodes. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 802-807.

- Liu R.; Shen C.; Dong Y.; Qin J.;Wang Q.; Iocozzia J.; Zhao S.; Yuan K.; Han C.; Li B.; Lin Z. Sandwich-like CNTs/Si/C nanotubes as high performance anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 14797-14804.

- Imtiaz S.; Amiinu I.S.; Storan D.; Kapuria N.; Geaney H.; Kennedy T.; Ryan K.M. Dense silicon nanowire networks grown on a stainless-steel fiber cloth: A flexible and robust anode for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2105917.

- Farooq U.; Choi J.-H.; Kim D.; Pervez S.A.; Yaqub A.; Hwang M.-J.; Lee Y.-J.; Lee W.-J.; Choi H.-Y.; Lee S.-H.; You J.-H.; Ha C.-W.; Doh C.-H. Electrically exploded silicon/carbon nanocomposite as anode material for Lithium-ion batteries. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 9340-9345.

- Demirkan M.T.; Trahey L.; Karabacak T. Cycling performance of density modulated multilayer silicon thin film anodes in Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 273, 52-61.

- Biserni E.; Xie M.; Brescia R.; Scarpellini A.; Hashempour M.; Movahed P.; George S.M.; M., Bestetti A.; Bassi L.; Bruno P. Silicon algae with carbon topping as thin-film anodes for lithium-ion microbatteries by a two-step facile method. J. Power Sources 2015, 274, 252-259.

- Cheng H.; Xiao R.; Bian H.; Li Z.; Zhan Y.; Tsang C.K.; Chung C.Y.; Lu Z.; Li Y. Periodic porous silicon thin films with interconnected channels as durable anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Mater. Chem. Phy. 2014, 144, 25-30.

- Jiang Z.; Li C.; Hao S.; Zhu K.; Zhang P. An easy way for preparing high performance porous silicon powder by acid etching Al–Si alloy powder for lithium ion battery. Electroch. Acta 2014, 115, 393-398.

- Li X.; Gu M.; Hu S.; Kennard R.; Yan P.; Chen X.; Wang C.; Sailor M.J.; Zhang J.; Liu J. Mesoporous silicon sponge as an anti-pulverization structure for high-performance lithium-ion battery anodes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4105.

- Ge M.; Lu Y.; Ercius P.; Rong J.; Fang X.; Mecklenburg M.; Zhou C. Large-scale fabrication, 3D tomography, and lithium-ion battery application of porous silicon. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 261-268.

- Yu Y.; Gu L.; Zhu C.; Tsukimoto S.; Van Aken P.A.; Maier J. Reversible storage of lithium in silver-coated three-dimensional macroporous silicon. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2247-2250.

- Borchers A.; Pieler T. Programming pluripotent precursor cells derived from Xenopus embryos to generate specific tissues and organs. Genes (Basel) 2010, 1, 413-426.

- Ahad S.A.; Kennedy T.; Geaney H. Si nanowires: From model system to practical li-ion anode material and beyond. ACS Energy Lett. 2024, 9, 1548-1561.

- Saana A. I.; Imtiaz S.; Geaney H.; Kennedy T.; Kapuria N.; Singh S.; Ryan K.M. A thin Si nanowire network anode for high volumetric capacity and long-life lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 81, 20-27.

- Collins G.A.; Kilian S.; Geaney H.; Ryan K. M. A nanowire nest structure comprising copper silicide and silicon nanowires for Lithium-ion battery anodes with high areal loading. Small 2021, 17, 2102333.

- Park Mi-H.; Kim M.G.; Joo J.; Kim K.; Kim J.; Ahn S.; Cui Y.; Cho J. Silicon nanotube battery anodes. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 3844-3847.

- Jeong Y. K.; Huang W.; Vilá R.A.; Huang W.; Wang J.; Kim S.C.; Kim Y. S.; Zhao J.; Cui Y. Microclusters of kinked silicon nanowires synthesized by a recyclable iodide process for high-performance lithium-ion battery anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2002108.

- Yang Y.; Yuan W.; Kang W.; Ye Y.; Pan Q.; Zhang X.; Ke Y.; Wang C.; Qiu Z.; Tang Y. A review on silicon nanowire-based anodes for next-generation high-performance lithium-ion batteries from a material-based perspective. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 1577-1594.

- Wu H.; Chan G.; Choi J. W.; Ryu I.; Yao Y.; McDowell M.T.; Lee S.W.; Jackson A.; Yang Y.; Hu L.; Cui Y. Stable cycling of double-walled silicon nanotube battery anodes through solid-electrolyte interphase control. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 310-315.

- Maranchi J. P.; Hepp A. F.; Kumtaa P. N. High capacity, reversible silicon thin-film anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2003, 6, A198-A201.

- Bourderau S.; Brousse T.; Schleich D. M. Amorphous silicon as a possible anode material for Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 1999, 81-82, 233-236.

- J. Li, Dozier A.K.; Li Y.; Yang F.; Cheng Y.-T. Crack pattern formation in thin film lithium-ion battery electrodes. J Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, A689.

- Yu C.; Li X.; Ma T.; Rong J.; Zhang R.; Shaffer J.; An Y.; Liu Q.; Wei B.; Jiang H. Silicon thin films as anodes for high-performance Lithium-ion batteries with effective stress relaxation. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012, 2, 68-73.

- Elomari G.; Larhlimi H.; Oubaki R.; Elmaataouy E.; Aqil M.; Samih Y.; Makha M.; Negrila C.; Alami J.; Dahbi M. Fast charging and high-efficiency sputter-deposited silicon thin film anodes for Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 642, 236967.

- Liu N.; Lu Z.; Zhao J.; McDowell M.T.; Lee H.-W.; Zhao W.; Cui Y. A pomegranate-inspired nanoscale design for large-volume-change lithium battery anodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 187-192.

- Li Y.; Yan K.; Lee H.-W.; Lu Z.; Liu N.; Cui Y. Growth of conformal graphene cages on micrometre-sized silicon particles as stable battery anodes. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 15029.

- Wang J.; Liao L.; Li Y.; Zhao J.; Shi F.; Yan K.; Pei A.; Chen G.; Li G.; Lu Z.; Cui Y. Shell-protective secondary silicon nanostructures as pressure-resistant high-volumetric-capacity anodes for Lithium-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 7060-7065.

- Ko M.; Chae S.; Jeong S.; Oh P.; Cho J. Elastic a-silicon nanoparticle backboned graphene hybrid as a self-compacting anode for high-rate Lithium ion batteries. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 8591-8599.

- An Y.; Tian Y.; Zhang Y.; Wei C.; Tan L.; Zhang C.; Cui N.; Xiong S.; Feng J.; Qian Y. Two-dimensional silicon/carbon from commercial alloy and CO2 for Lithium storage and flexible Ti3C2Tx MXene-based Lithium–metal batteries. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 17574-17588.

- Zhang Z. D.; Zhou H.P.; Feng T.T.; Zhao R.; Wang Y.; He M.; Xu Z.Q.; Liao J.X.; Xue W.D.; Wu M.Q. A plasma strategy for high-quality Si/C composite anode: From tailoring the current collector to preparing the active materials. Electroch. Acta 2020, 347, 136222.

- Zhang Z. D.; Zhou H.P.; Xue W.D.; Zhao R.; Wang W.J.; Feng T.T.; Xu Z.Q.; Zhang S.; Liao J.X.; Wu M.Q. Nitrogen-plasma doping of carbon film for a high-quality layered Si/C composite anode. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 605, 463-471.

- Li X.; Wu M.; Feng T.; Xu Z.; Qin J.; Chen C.; Tu C.; Wang D. Graphene enhanced silicon/carbon composite as anode for high performance lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 48286-48293.

- Qin J.; Wu M.; Feng T.; Chen C.; Tu C.; Li X.; Duan C.; Xia D.; Wang D. High rate capability and long cycling life of graphene-coated silicon composite anodes for lithium ion batteries. Electroch. Acta 2017, 256, 259-266.

- Wang R.; Cao J.; Xu C.; Wu N.; Zhang S.; Wu M. Low-temperature electrolytes based on linear carboxylic ester co-solvents for SiO(x)/graphite composite anodes. RSC Adv. 2023, 13; 13365-13373.

- Wang W.; Kumta P. N. Nanostructured hybrid silicon-carbon nanotube heterostructures reversible high-capacity Lithium-ion anodes. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2233-2241.

- Tao H.; Xiong L.; Zhu S.; Zhang L.; Yang X. Porous Si/C/reduced graphene oxide microspheres by spray drying as anode for Li-ion batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 797,16-22.

- Zhang J.; Chen Y.; Chen X.; Feng T.; Yang P.; An M. Preparation of graphene-like carbon attached porous silicon anode by magnesiothermic and nickel-catalyzed reduction reactions. Ionics 2020, 26, 5941-5950.

- Cabello M.; Gucciardi E.; Herrán A.; Carriazo D.; Villaverde A.; Rojo T. Towards a high-power Si@graphite anode for Lithium ion batteries through a wet ball milling process. Molecules 2020, 25 2494.

- Wan W.; Mai Y.; Guo D.; Hou G.; Dai X.; Gu Y.; Li S.; Wu F. A novel sol-gel process to encapsulate micron silicon with a uniformly Ni-doped graphite carbon layer by coupling for use in lithium ion batteries. Synthetic Met. 2021, 274, 116717.

- Azam M.A.; Safie N.E.; Ahmad A.S.; Yuza N.A.; Zulkifli N.S.A. Recent advances of silicon, carbon composites and tin oxide as new anode materials for lithium-ion battery: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage 2021, 33, 102096.

- Wang C. S.; Wu G.T.; Zhang X. B.; Qi Z. F.; Li W. Z. Lithium insertion in carbon-silicon composite materials produced by mechanical milling. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1998, 145, 2751-2758.

- He S.; Huang S.; Wang S.; Mizota I.; Liu X.; Hou X. Considering critical factors of Silicon/Graphite anode materials for practical high-energy Lithium-ion battery applications. Energy Fuels 2020, 35, 944-964.

- Li Z.; Wan Z.; Zeng X.; Zhang S.; Yan L.; Li J.; Wang H.; Ma Q.; Liu T.; Lin Z.; Ling M.; Liang C. A robust network binder via localized linking by small molecules for high-areal-capacity silicon anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2021, 79,105430.

- Li Z.; Li D.; Sun X.; Xue Y.; Shi Y.; Fu Y.; Luo C.; Lin Q.; Gui X.; Xu K. Ion-conductive and mechanically robust chitosan-based network binder for silicon/graphite anode. J. Energy Storage 2024, 93, 112264.

- Wang X.; Li T.; Liang N.; Liu X.; Zhang F.; Li Y.; Yang Y.; Yang Y.; Ma W.; Wang Z.; Yin J.; Yang Y.; Yang L. Lithium borate/boric acid optimized multifunctional binder facilitates silicon anodes with enhanced initial coulombic efficiency, structural strength, and cycling stability. Battery Energy 2025, 4, e70003.

- Wang W.; Li X.; Chen X.; Sun M.; Wang G. Aqueous binder with self-emulsifying characteristics for practical Si/C anode in Lithium-ion batteries. Chemistry 2025, 31, e202403924.

- Yan W.; Ma S.; Su Y.; Song T.; Lu Y.; Chen L.; Huang Q.; Guan Y.; Wu F.; Li N. “Shooting three birds with one stone”: Bi-conductive and robust binder enabling low-cost micro-silicon anodes for high-rate and long-cycling operation. Energy Storage Mater. 2025, 76, 104140.

- Zhang Y.-T.; Xue J.-X.; Wang R.; Jia S.-X.; Zhou J.-J.; Li L. Cross-linkable binder for composite silicon-graphite anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Giant 2024, 19, 100319.

- Yi S.; Yan Z.; Li X.; Wang Z.; Ning P.; Zhang J.; Huang J.; Yang D.; Du N. Design of phosphorus-doped porous hard carbon/Si anode with enhanced Li-ion kinetics for high-energy and high-power Li-ion batteries. Chem.Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145161.

- Liu C.; Zhou H.P.; Zhou H.; Yang B.; Li Z.K.; Zhang S.; Feng T.T.; Xu Z.Q.;Fang Z.X.; Wu M.Q. Highly Si loading on three-dimensional carbon skeleton via CVD method for a stable Si C composite anode. J. Energy Storage 2025, 116, 116083.

- Ahn W.J.; Park B.H.; Seo S.W.; Kim S.; Im J.S. Designing of 3D porous silicon/carbon complex anode based on metal-organic frameworks for lithium-ion battery. Carbon Lett. 2023, 33, 2349-2361.

- Li X.; Li K.; Yuan L.; Han Z.; Yan Z.; Xu X.; Tang K. Cost-effective preparation of high-performance Si@C anode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2024, 54, 2683-2697.

- Xu Q.; Li J.Y.; Sun J.K.; Yin Y.X.; Wan L.J.; Guo Y.G. Watermelon-inspired Si/C microspheres with hierarchical buffer structures for densely compacted Lithium-ion battery anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 7, 1601481.

- Wei K.; Zhou L.; Wang S.; Wei J.; Yan D.; Cheng Y.; Yu Z. Watermelon-like texture lithium titanate and silicon composite films as anodes for lithium-ion battery with high capacity and long cycle life. J. Alloy. Compd. 2021, 885, 160994.

- Ashraf H.; Karahan B.D.; Biowaste valorization into valuable nanomaterials: Synthesis of green carbon nanodots and anode material for lithium-ion batteries from watermelon seeds. Mater. Res. Bull. 2024, 169, 112492.

- Ding N.; Chen Y.; Li R.; Chen J.; Wang C.; Li Z.; Zhong S. Pomegranate structured C@pSi/rGO composite as high performance anode materials of lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 367, 137491.

- Li P.; Miao C.; Yi D.; Wei Y.; Chen T.; Wu W. Pomegranate like silicon-carbon composites prepared from lignin-derived phenolic resins as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. New J. Chem. 2023, 47, 16855-16863.

- Di F.; Wang Z.; Ge C.; Li L.; Geng X.; Sun C.; Yang H.; Zhou W.; Ju D.; An B.; Li F. Hierarchical pomegranate-structure design enables stress management for volume release of Si anode. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 157, 1-10.

- Hu L.; Luo B.; Wu C.; Hu P.; Wang L.; Zhang H. Yolk-shell Si/C composites with multiple Si nanoparticles encapsulated into double carbon shells as lithium-ion battery anodes. J. Energy Chem. 2019, 32, 124-130.

- Li B.; Li S.; Jin Y.; Zai J.; Chen M.; Nazakat A.; Zhan P.; Huang Y.; Qian X. Porous Si@C ball-in-ball hollow spheres for lithium-ion capacitors with improved energy and power densities. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 21098-21103.

- Tian H.; TIan H.; Yang W.; Zhang F.; Yang W.; Zhang Q.; Wang Y.; Liu J.; Silva S.R.P.; Liu H.; Wang G. Stable hollow-structured silicon suboxide-based anodes toward high-performance Lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2101796.

- Liu H.; Chen Y.; Jiang B.; Zhao Y.; Guo X.; Ma T. Hollow-structure engineering of a silicon–carbon anode for ultra-stable lithium-ion batteries. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 5669-5676.

- Li Z.; Du M.; Guo X.; Zhang D.; Wang Q.; Sun H.; Wang B.; Wu Y. A. Research progress of SiO -based anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145294.

- Wu J.; Dong Q.; Zhang Q.; Xu Y.; Zeng X.; Yuan Y.; Lu J. Fundamental understanding of the low Initial coulombic efficiency in SiOx anode for Lithium-ion batteries: Mechanisms and solutions. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2405751.

- Zhou H.P.; Yang B.; Zhang Z.D.; Zhang H.; Zhang S.; Feng T.T.; Xu Z.Q.; Gao J.; Wu M.Q. Fastly PECVD-grown vertical carbon nanosheets for a composite SiOx-C anode material. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 605, 154627.

- Zhou H.; Zhou H.P.; Yang B.; Liu C.; Zhang S.; Feng T.T.; Xu Z.Q.; Fang Z.X.; Wu M.Q. Carbon nano-onions/tubes catalyzed by Ni nanoparticles on SiOx for superior lithium storage. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 640, 158355.

- Zhou H.; Yang B.; Zhou H.; Liu C.; Zhang S.; Feng T.; Xu Z.; Fang Z.; Gao J.; Wu M. Carbon shells and carbon nanotubes jointly modified SiOx anodes for superior lithium storage. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 10307-10316.

- Meng Q.; Li G.; Yue J.; Xu Q.; Yin Y.-X.; Guo Y.-G. High-performance lithiated SiOx anode obtained by a controllable and efficient prelithiation strategy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2019, 11, 32062-32068.

- Zhang X.; Qu H.; Ji W.; Zheng D.; Ding T.; Qiu D; Qu D. An electrode-level prelithiation of SiO anodes with organolithium compounds for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2020, 478, 229067.

- Chen S.; Wang Z.; Wang L.; Song Z.; Yang K.; Zhao W.; Liu L.; Fang J.; Qian G.; Pan F.; Yang L. Constructing a robust solid-electrolyte interphase layer via chemical prelithiation for high-performance SiOx anode. Adv. Energ. Sust. Res. 2022, 3, 2200083.

- Li Y.; Qian Y.; Zhao Y.; Lin N.; Qian Y. Revealing the interface-rectifying functions of a Li-cyanonaphthalene prelithiation system for SiO electrode. Sci Bull 2022, 67, 636-645.

- Li X.; Bian C.; Zhang J.; Hong J.; Fu R.; Zhou X.; Liu Z.; Shao G. Chemical pre-lithiation of SiOx anodes with a weakly solvating solution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons for Lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 8919-8928.

- Ji S.; Song R.; Yuan H.; Lv D.; Yang L.; Luan J.; Wan D.; Liu J.; Zhong C. Improving the initial coulombic efficiency of SiO anode materials for lithium ion batteries by carbon coating and prelithiation. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2024, 959, 118141.

- Tang Z.; Zhou Y.; Luo B.; Li D.; Zhang B. Microstructure and electrochemical performance of Li(2)CO(3)-modified submicron SiO as an anode for Lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl Mater Interf. 2025, 17, 19573-19586.

- Song R.; Di J.; Lv D.; Yang L.; Juan J.; Yuan H.; Liu J.; Hu W.; Zhong C. Improving the electrochemical properties of SiO(x) anode for high-performance Lithium-ion batteries by magnesiothermic reduction and prelithiation. ACS Appl Mater Interf. 2025, 17, 7849-7859.

- Chung D.J.; Youn D.; Kim S.; Ma D.; Lee J.; Jeong W.J.; Park E.; Kim J.-S.; Moon C.; Lee J.Y.; Sun H.; Kim H. Dehydrogenation-driven Li metal-free prelithiation for high initial efficiency SiO-based lithium storage materials. Nano Energy 2021, 89, 106378.

- Lau V.; Kuo C.; Lan C. Objective review on commercially viable prelithiation techniques for Lithium-ion batteries. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202300501.

- Jeong W.J.; Chung D.J.; Youn D.; Kim N.G.; Kim H. Double-buffer-phase embedded Si/TiSi2/Li2SiO3 nanocomposite lithium storage materials by phase-selective reaction of SiO with metal hydrides. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 50, 740-750.

- Chung D.J.; Youn D.; Kim J.Y.; Jeong W.J.; Kim S.; Ma D.; Lee T.R.; Kim S.T.; Kim H. Topology optimized prelithiated SiO anode materials for Lithium-ion batteries. Small 2022, 18, 2202209.

- Zhan R.; Wang X.; Chen Z.; Seh Z.W.; Wang L.; Sun Y. Promises and challenges of the practical implementation of prelithiation in Lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2101565.

- Zhang Z.; Wang H.; Cheng M.; He Y.; Han X.; Luo L.; Su P.; Huang W.; Wang J.; Li C.; Zhu Z.; Zhang Q.; Chen S. Confining invasion directions of Li+ to achieve efficient Si anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 42; 231-239.

- Yi S.; Yan Z.; Xiao Y.; Ye C.; Qiu H.; Zhang J.; Ning P.; Yang D.; Du N. Synergistic prelithiation and in situ nitrogen doping via Li(3)N in SiO anodes: A dual-benefit pathway to achieving enhanced Li(+) kinetics and high initial coulombic efficiency. Small 2025, 21, e2501524.

- Li J.; Zhang S.; Zeng G.; Xi Z.; Khan M.D.; Biendicho J.J.; Cabot A.; Ci L.; Sun Q.; LiF-induced formation of quartz nanodomains in micron-sized SiOx anodes for durable Lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 7753-7761.

- Li J.; Zeng G.; Horta S.; Martinez-Alanis P.R.; Jacas Biendicho J.; Ibanez M.; Xu B.; Ci L.; Cabot A.; Sun Q. Crystallographic engineering in micron-sized SiO(x) anode material toward stable high-energy-density Lithium-ion batteries. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 16096-16109.

- Wang D.; Zhou C.; Cao B.; Xu Y.; Zhang D.; Li A.; Zhou J.; Ma Z.; Chen X.; Song H. One-step synthesis of spherical Si/C composites with onion-like buffer structure as high-performance anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 24, 312-318.

- Dong X.; Woo C.; Oh S.; Kim Y.; Zhang X.; Kim K.I.; Choi K.H.; Kang J.; Jeon J.; Bang H.-S.; Oh H.-S.; Yu H.K.; Mun J.; Choi J.-Y. Effect of carbonization temperature on the electrochemical performance of monodisperse Carbon/SiO2 nanocomposites as lithium-ion batteries anode. J. Power Sources 2025, 631, 236291.

- Yang T.; Wang Y.; Yang L.; Zhang H.; Zhang M.; Ang E.H.; Zhu J. Dynamic engineering of lithiation reactions in silicon oxide with interface regulation for enhanced safety in lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 509, 161100.

- S. Yoo, J. Kim, B. Kang, Characterizing local structure of SiOx using confocal μ-Raman spectroscopy and its effects on electrochemical property, Electrochimica Acta, 2016, 12, 68-75.

- Xie H.; Hou C.; Yue Z.; Zhai L.; Sun H.; Lu H.; Wu J.; Yang S.; Ma Y. Facile synthesis of C, N, P co-doped SiO as anode material for lithium-ion batteries with excellent rate performance. J. Energy Storage 2023, 64, 107147.

- Suh S. S.; Yoon W.Y.; Kim D.H.; Kwon S.U.; Kim J.H.; Kim Y.U.; Jeong C.U.;Chan Y.Y.; Kang S.H.; Lee J.K.; Electrochemical behavior of SiOx anodes with variation of oxygen ratio for Li-ion batteries, Electrochim. Acta 2014, 148, 111-117.

- Raza A.; Jung J.Y.; Lee C.-H.; Kim B.G.; Choi J.-H.; Park M.-S.; Lee S.-M. Swelling-controlled double-layered SiOx/Mg2SiO4/SiOx composite with enhanced initial coulombic efficiency for Lithium-ion battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2021, 13, 7161-7170.

- Cheng Y.; Wei K.; Yu Z.; Fan D.; Yan D.L.; Pan Z.; Tian B. Ternary Si-SiO-Al composite films as high-performance anodes for Lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2021, 13, 34447-34456.

- Zhang P.; Wang L.; Xie J.; Su L.; Ma C. Micro/nano-complex-structure SiOx-PANI-Ag composites with homogeneously-embedded Si nanocrystals and nanopores as high-performance anodes for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 3776-3782.

- Yu Z.; Yu K.; Wei J.; Lu Q.; Cheng Y.; Pan Z. Improving electrode properties by sputtering Ge on SiO anode surface. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 26784-26790.

- Röck A.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens M.; Axmann P.; Hoffmann A. Improving Gr/SiO negative electrode formulations: Effect of active material, binders, and single-walled carbon nanotubes. Batteries Supercaps 2025, 0, e202400764.

- Ling Y.; Chen T.; Chen S.; Wang B.; Zeng P.; Shen S.; Yuan C.; Zhou Z.; Wang J.; Zhang L. Incorporating Co Nanoparticles into SiOx Anodes for HighPerformance Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 6723-6732.

- Gao M.; Wang D.; Zhang X.; Pan H.; Liu Y.; Liang C.; Shang C.; Guo Z. A hybrid Si@FeSiy/SiOx anode structure for high performance lithium-ion batteries via ammonia-assisted one-pot synthesis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 10767-10776.

- Bian C.; Fu R.; Shi Z.; Ji J.; Zhang J.; Chen W.; Zhou X.; Shi S.; Liu Z. Mg2SiO4/Si-coated disproportionated SiO composite anodes with high initial coulombic efficiency for lithium ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2022, 14, 15337-15345.

- Kim K.; Choi H.; Kim J.-H. Effect of carbon coating on nano-Si embedded SiOx-Al2O3 composites as lithium storage materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 416, 527-535.

- Youn D.; Kim J.Y.; Lee T.R.; Han J.; Kim S.; Kim H. Al2O3-sheathed Si/Li2SiO3 nanocomposite anode materials for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160366.

- Zhou M.; Gordin M.L.; Chen S.; Xu T.; Song J.; Lv D.; Wang D. Enhanced performance of SiO/Fe2O3 composite as an anode for rechargeable Li-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2013, 28, 79-82.

- Liao C.; Wu S. Pseudocapacitance behavior on Fe3O4-pillared SiOx microsphere wrapped by graphene as high performance anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 355, 805-814.

- Park Y.; Lee J. Silicon monoxide with black titania and carbon coating layer as an anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Appl.Surf. Sci. 2021, 554, 149512.

- Xiao Z.; Yu C.; Lin X.; Chen X.; Zhang C.; Jiang H.; Zhang R.; Wei F. TiO2 as a multifunction coating layer to enhance the electrochemical performance of SiOx@TiO2@C composite as anode material. Nano Energy 2020, 77, 105082.

- Xu Y.; Li Y.; Qian Y.; Sun S.; Lin N.; Qian Y. Deficient TiO2−x coated porous SiO anodes for high-rate lithium-ion batteries. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 1176-1186.

- Lai G.; Wei X.; Zhou B.; Huang X.; Tang W.; Wu S.; Lin Z. Engineering high-performance SiOx anode materials with a titanium oxynitride coating for Lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2022, 14, 49830-49838.

- Liu H.; Zhang X.; Xu Q. Jin Y.; Lv S.; Liu H. Oxygen vacancy-driven embedded electric fields in TiO2−x/SiOx anodes for superior Lithium-ion battery performance. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 7430−7439.

- Zhang Y.; Guo G.; Chen C.; Jiao Y.; Li T.; Chen X.; Yang Y.; Yang D.; Dong A. An affordable manufacturing method to boost the initial Coulombic efficiency of disproportionated SiO lithium-ion battery anodes. J. Power Sources 2019, 426, 116-123.

- Long Z.; Fu R.; Ji J.; Feng Z.; Liu Z. Unveiling the effect of surface and bulk structure on electrochemical properties of disproportionated SiOx anodes. ChemNanoMat 2020, 6, 1127-1135.

- Guo P.; Wang C. Good lithium storage performance of Fe2SiO4 as an anode material for secondary lithium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 4437-4443.

- Tang C.; Liu Y.; Xu C.; Zhu J.; Wei X.; Zhou L.; He L.; Yang W.; Mai L. Ultrafine nickel-nanoparticle-enabled SiO2 hierarchical hollow spheres for high-performance lithium storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1704561.

- Fu R.; Wu Y.; Fan C.; Long Z.; Shao G.; Liu Z. Reactivating Li2O with nano-Sn to achieve ultrahigh initial coulombic efficiency SiO anodes for Li-ion batteries. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 3377-3382.

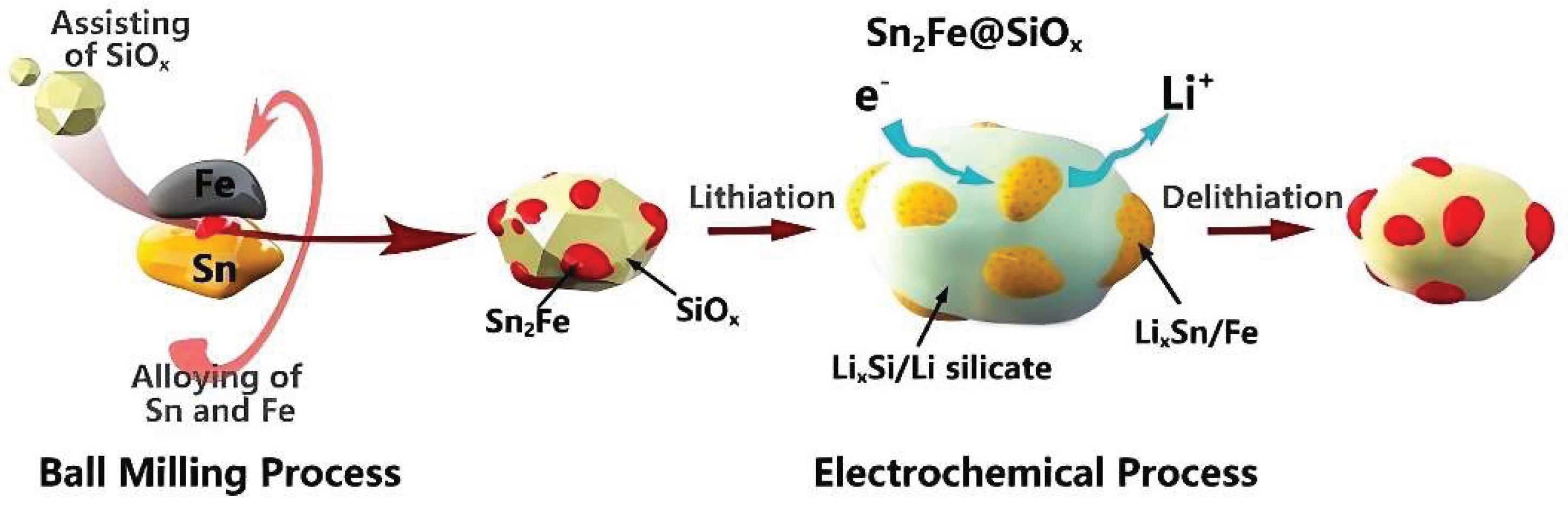

- Zhang H.; Hu R.; Liu Y.; Cheng X.; Liu J.; Lu Z.; Zeng M.; Yang L.; Liu J.; Zhu M. Highly reversible conversion reaction in Sn2Fe@SiOx nanocomposite: A high initial Coulombic efficiency and long lifetime anode for lithium storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2018, 13, 257-266.

- Zhou Z.; Li Z.; Liu X.; Wu J.; Li K.; Wang C. Enhanced performance of yolk-shell SiO/MWCNTs@C composites bridged by MWCNTs for high-performance lithium-ion battery anodes. Chem. Engin. J. 2025, 511, 162297.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).